Preview text:

Quy hoạch động Trần Vĩnh Đức HUST Ngày 7 tháng 9 năm 2019 1 / 61 Tài liệu tham khảo

▶ S. Dasgupta, C. H. Papadimitriou, and U. V. Vazirani,

Algorithms, July 18, 2006. 2 / 61 Nội dung

Đường đi ngắn nhất trên DAG Dãy con tăng dài nhất Khoảng cách soạn thảo Bài toán cái túi Nhân nhiều ma trận Đường đi ngắn nhất Tập độc lập trên cây Chapter 6 Dynamic programming

In the preceding chapters we have seen some elegant design principles—such as divide-and-

conquer, graph exploration, and greedy choice—that yield definitive algorithms for a variety

of important computational tasks. The drawback of these tools is that they can only be used

on very specific types of problems. We now turn to the two sledgehammers of the algorithms

craft, dynamic programming and linear programming, techniques of very broad applicability

that can be invoked when more specialized methods fail. Predictably, this generality often

comes with a cost in efficiency.

6.1 Shortest paths in dags, revisited

At the conclusion of our study of shortest paths (Chapter 4), we observed that the problem is Đồes thị pecial phi ly easychu in dire trình cted acyc (D lic grA apG): hs (da Nhắc gs). Let’s lại

recapitulate this case, because it lies at

the heart of dynamic programming.

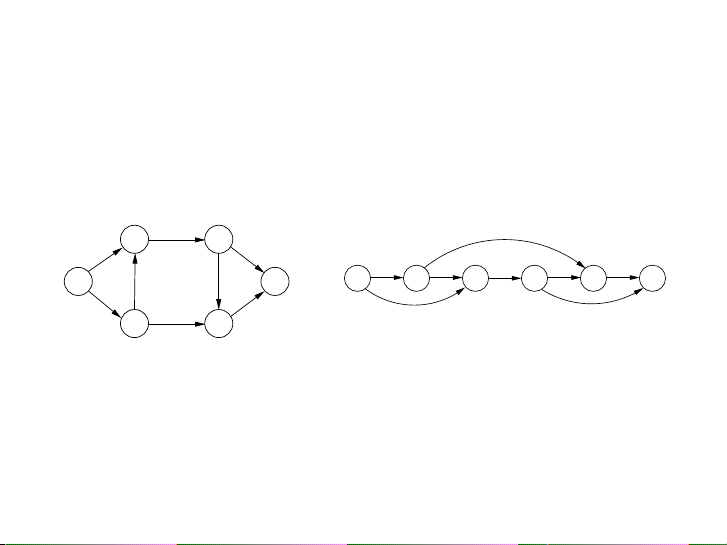

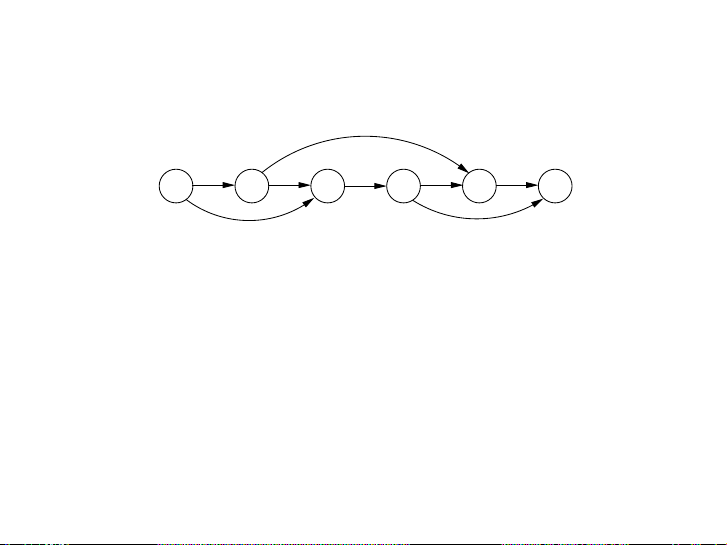

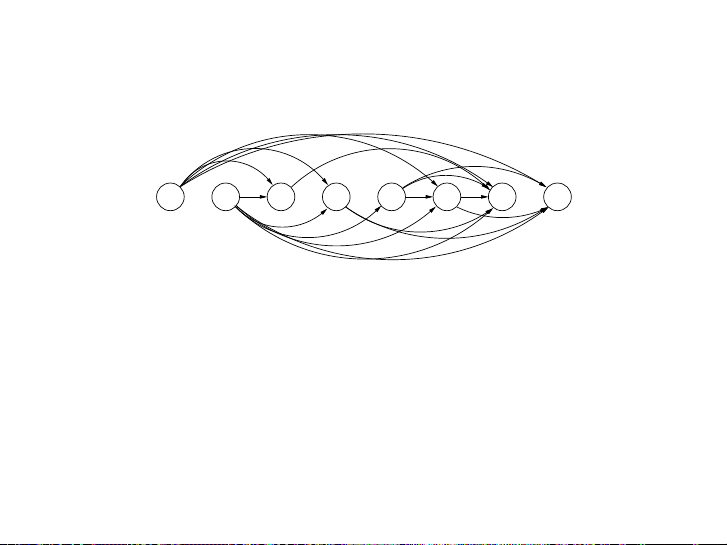

The special distinguishing feature of a dag is that its nodes can be linearized; that is, they

can be arranged on a line so that all edges go from left to right (Figure 6.1). To see why T thisrong helps đồ wit thị h shophi rtest chu path trình, s, suppo ta se có we wthể ant sắp to fig xếp ure ou thứ t dist tự anc các es fro đỉnh m nod sao e S to the

other nodes. For concreteness, let’s focus on node

cho nó chỉ có cung đi đi từ trái sang phải.

D. The only way to get to it is through its

Figure 6.1 A dag and its linearization (topological ordering). A 6 B 3 1 2 2 1 S 4 6 1 4 1 E S C A B D E 2 1 2 C 3 1 D

Hình: Đồ thị phi chu trình G và 169

biểu diễn dạng tuyến tính của nó. 4 / 61 Chapter 6 Dynamic programming

In the preceding chapters we have seen some elegant design principles—such as divide-and-

conquer, graph exploration, and greedy choice—that yield definitive algorithms for a variety

of important computational tasks. The drawback of these tools is that they can only be used

on very specific types of problems. We now turn to the two sledgehammers of the algorithms

craft, dynamic programming and linear programming, techniques of very broad applicability

that can be invoked when more specialized methods fail. Predictably, this generality often

comes with a cost in efficiency.

6.1 Shortest paths in dags, revisited

At the conclusion of our study of shortest paths (Chapter 4), we observed that the problem is

especially easy in directed acyclic graphs (dags). Let’s recapitulate this case, because it lies at

the heart of dynamic programming.

The special distinguishing feature of a dag is that its nodes can be linearized; that is, they

can be arranged on a line so that all edges go from left to right (Figure 6.1). To see why

this helps with shortest paths, suppose we want to figure out distances from node S to the Đường other no đi des. ngắn For con nhất creteness, trên let’s foc D us A on G

node D. The only way to get to it is through its

Figure 6.1 A dag and its linearization (topological ordering). A 6 B 3 1 2 2 1 S 4 6 1 4 1 E S C A B D E 2 1 2 C 3 1 D

Hình: Đồ thị phi chu trình G và 169

biểu diễn dạng tuyến tính của nó.

▶ Xét nút D của đồ thị, cách duy nhất để đi từ S đến D là phải qua B hoặc C.

▶ Vậy, để tìm đường đi ngắn nhất từ S tới D ta chỉ phải so sánh hai đường:

dist(D) = min{dist(B) + 1, dist(C) + 3} 5 / 61 Chapter 6 Dynamic programming

In the preceding chapters we have seen some elegant design principles—such as divide-and-

conquer, graph exploration, and greedy choice—that yield definitive algorithms for a variety

of important computational tasks. The drawback of these tools is that they can only be used

on very specific types of problems. We now turn to the two sledgehammers of the algorithms

craft, dynamic programming and linear programming, techniques of very broad applicability

that can be invoked when more specialized methods fail. Predictably, this generality often

comes with a cost in efficiency.

6.1 Shortest paths in dags, revisited

At the conclusion of our study of shortest paths (Chapter 4), we observed that the problem is

especially easy in directed acyclic graphs (dags). Let’s recapitulate this case, because it lies at

the heart of dynamic programming.

The special distinguishing feature of a dag is that its nodes can be linearized; that is, they

can be arranged on a line so that all edges go from left to right (Figure 6.1). To see why

this helps with shortest paths, suppose we want to figure out distances from node S to the

other nodes. For concreteness, let’s focus on node D. The only way to get to it is through its

Thuật toán tìm đường đi ngắn nhất cho DAG

Figure 6.1 A dag and its linearization (topological ordering). A 6 B 3 1 2 2 1 S 4 6 1 4 1 E S C A B D E 2 1 2 C 3 1 D Thuật toán 169

Khởi tạo mọi giá trị dist(.) bằng ∞ dist(s) = 0

for each v ∈ V \ {s}, theo thứ tự tuyến tính:

dist(v) = min(u,v)∈E{dist(u) + ℓ(u, v)} 6 / 61 Chapter 6 Dynamic programming

In the preceding chapters we have seen some elegant design principles—such as divide-and-

conquer, graph exploration, and greedy choice—that yield definitive algorithms for a variety

of important computational tasks. The drawback of these tools is that they can only be used

on very specific types of problems. We now turn to the two sledgehammers of the algorithms

craft, dynamic programming and linear programming, techniques of very broad applicability

that can be invoked when more specialized methods fail. Predictably, this generality often

comes with a cost in efficiency.

6.1 Shortest paths in dags, revisited

At the conclusion of our study of shortest paths (Chapter 4), we observed that the problem is

especially easy in directed acyclic graphs (dags). Let’s recapitulate this case, because it lies at

the heart of dynamic programming.

The special distinguishing feature of a dag is that its nodes can be linearized; that is, they

can be arranged on a line so that all edges go from left to right (Figure 6.1). To see why

this helps with shortest paths, suppose we want to figure out distances from node S to the

other nodes. For concreteness, let’s focus on node D. The only way to get to it is through its

Figure 6.1 A dag and its linearization (topological ordering). A 6 B 3 1 2 2 1 S 4 6 1 4 1 E S C A B D E 2 1 2 C 3 1 D Bài tập 169

Làm thế nào để tìm đường đi dài nhất trong DAG? 7 / 61 Chapter 6 Dynamic programming

In the preceding chapters we have seen some elegant design principles—such as divide-and-

conquer, graph exploration, and greedy choice—that yield definitive algorithms for a variety

of important computational tasks. The drawback of these tools is that they can only be used

on very specific types of problems. We now turn to the two sledgehammers of the algorithms

craft, dynamic programming and linear programming, techniques of very broad applicability

that can be invoked when more specialized methods fail. Predictably, this generality often

comes with a cost in efficiency.

6.1 Shortest paths in dags, revisited

At the conclusion of our study of shortest paths (Chapter 4), we observed that the problem is

especially easy in directed acyclic graphs (dags). Let’s recapitulate this case, because it lies at

the heart of dynamic programming.

The special distinguishing feature of a dag is that its nodes can be linearized; that is, they

can be arranged on a line so that all edges go from left to right (Figure 6.1). To see why

this helps with shortest paths, suppose we want to figure out distances from node S to the

other nodes. For concreteness, let’s focus on node D. The only way to get to it is through its

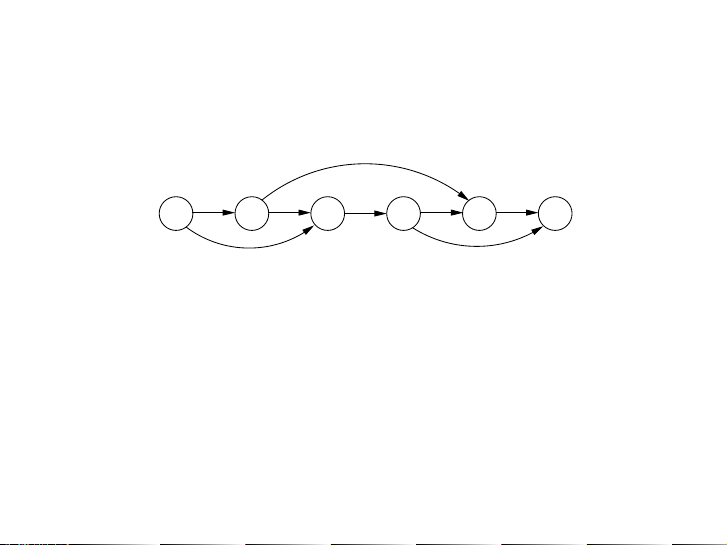

Ý tưởng quy hoạch động

Figure 6.1 A dag and its linearization (topological ordering). A 6 B 3 1 2 2 1 S 4 6 1 4 1 E S C A B D E 2 1 2 C 3 1 D

Hình: Để giải bài toán D ta cần giải bài toán con C và B. 169

▶ Quy hoạch động là kỹ thuật giải bài toán bằng cách xác

định một tập các bài toán con và giải từng bài toán con một, nhỏ nhất trước,

▶ dùng câu trả lời của bài toán nhỏ để hình dung ra đáp án của bài toán lớn hơn,

▶ cho tới khi toàn bộ các bài toán được giải. 8 / 61 Nội dung

Đường đi ngắn nhất trên DAG Dãy con tăng dài nhất Khoảng cách soạn thảo Bài toán cái túi Nhân nhiều ma trận Đường đi ngắn nhất Tập độc lập trên cây

Bài toán dãy con tăng dài nhất

Cho dãy số a1, a2, . . . , an. Một dãy con là một tập con các số lấy

theo thứ tự, nó có dạng ai , a , . . . , a 1 i2 ik

ở đó 1 ≤ i1 < i2 < · · · < ik ≤ n, và dãy tăng là dãy mà các phần

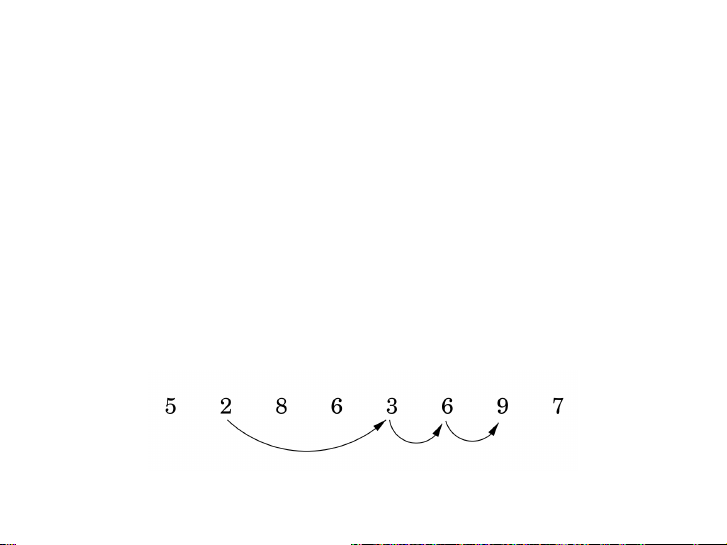

tử tăng dần. Nhiệm vụ của bạn là tìm dãy tăng có số phần tử nhiều nhất. Ví dụ

Dãy con dài nhất của dãy 5, 2, 8, 6, 3, 6, 9, 7 là: 10 / 61 Bài tập

Hãy tìm dãy con tăng dài nhất của dãy

5, 3, 8, 6, 2, 6, 9, 7. 11 / 61

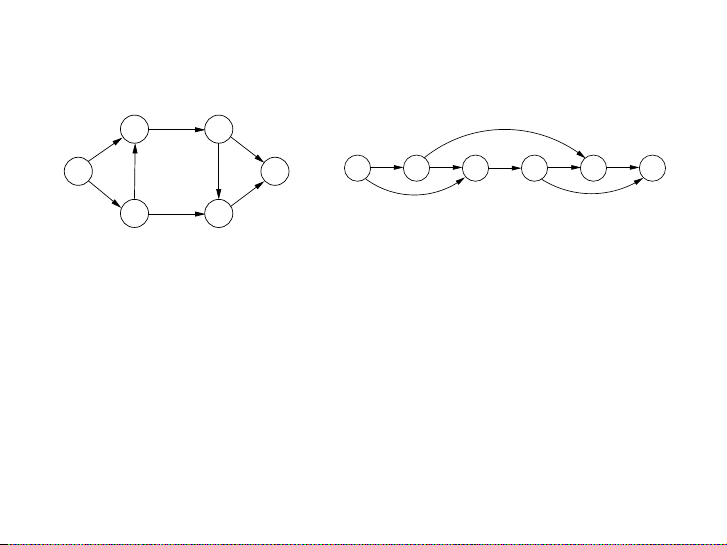

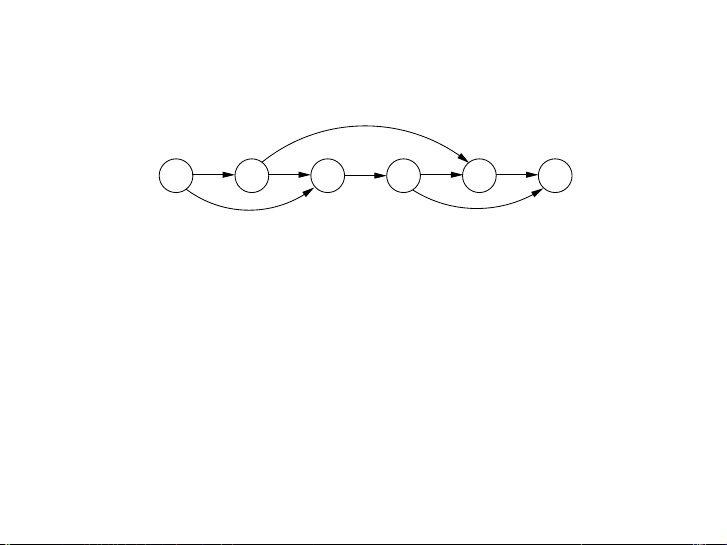

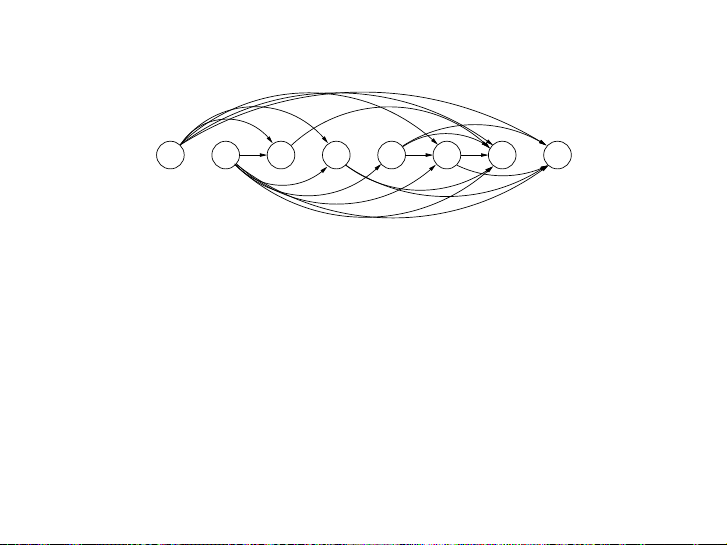

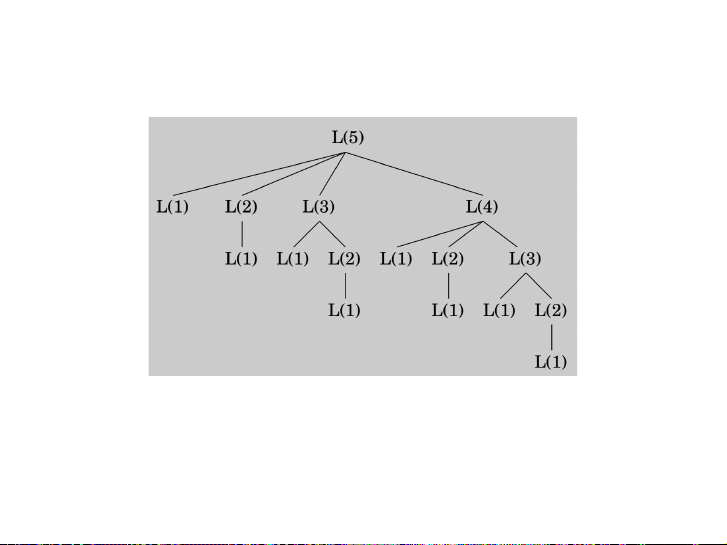

S. Dasgupta, C.H. Papadimitriou, and U.V. Vazirani 171 DAG của dãy tăng

Figure 6.2 The dag of increasing subsequences. 5 2 8 6 3 6 9 7

Hình: DAG G = (V, E) của dãy 5, 2, 8, 6, 3, 6, 9, 7.

In this example, the arrows denote transitions between consecutive elements of the opti-

mal solution. More generally, to better understand the solution space, let’s create a graph of

all permissible transitions: establish a node i for each element ai, and add directed edges (i, j)

whenever it is possible for ai and aj to be consecutive elements in an increasing subsequence,

that is, whenever i < j and ai < aj (Figure 6.2).

Notice that (1) this graph G = (V, E) is a dag, since all edges (i, j) have i < j, and (2)

Ta xây dựng DAG G = (V, E) cho dãy a

there is a one-to-one correspondence between increasing su 1, a bseq2, . . . , a uences and pa n như sau: ths in this dag. The ▶refor

V e, our goal is simply to find the longest path in the dag! = {a Here is the alg 1, a orithm 2, . . . , an}, và :

▶ có cung (ai, aj) ∈ E nếu i < j và ai < aj. for j = 1, 2, . . . , n: L(j) = 1 + max

Bài toán tìm dãy {L(i) : (i, j) tăng dài ∈ E}

nhất được đưa về bài toán tìm đường đi return maxj L(j) dài nhất trên DAG.

L(j) is the length of the longest path—the longest increasing subsequence—ending at j (plus

1, since strictly speaking we need to count nodes on the path, not edges). By reasoning in the

same way as we did for shortest paths, we see that any path to node 12 / 61 j must pass through one

of its predecessors, and therefore L(j) is 1 plus the maximum L(·) value of these predecessors.

If there are no edges into j, we take the maximum over the empty set, zero. And the final

answer is the largest L(j), since any ending position is allowed.

This is dynamic programming. In order to solve our original problem, we have defined a

collection of subproblems {L(j) : 1 ≤ j ≤ n} with the following key property that allows them to be solved in a single pass:

(*) There is an ordering on the subproblems, and a relation that shows how to solve

a subproblem given the answers to “smaller” subproblems, that is, subproblems

that appear earlier in the ordering.

In our case, each subproblem is solved using the relation

L(j) = 1 + max{L(i) : (i, j) ∈ E},

Tìm đường đi dài nhất trên DAG

for j = 1, 2, . . . , n:

L(j) = 1 + max{L(i) : (i, j) ∈ E}

return maxj L(j)

▶ L(j) là độ dài của đường đi dài nhất kết thúc tại j. 13 / 61

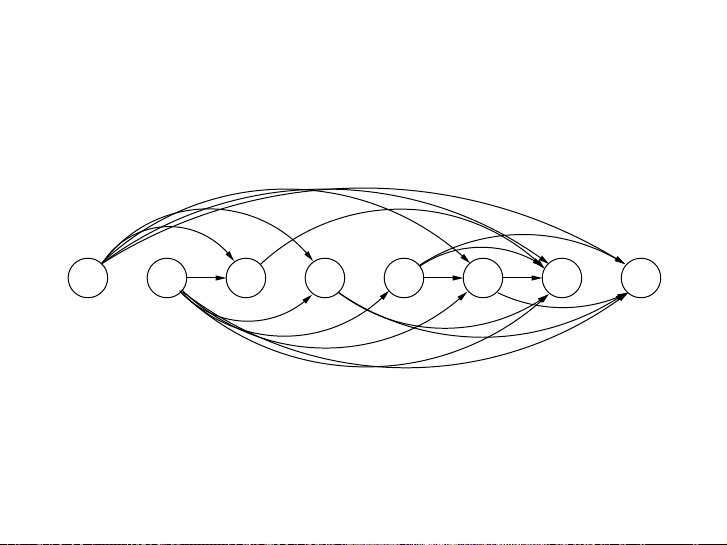

S. Dasgupta, C.H. Papadimitriou, and U.V. Vazirani 171 Bài tập Figure 6.2 Hã Th y e tìm dag đường of incre đi as dài ing nhất subse trên quen D ceA s.G sau: 5 2 8 6 3 6 9 7

In this example, the arrows denote transitions between consecutive elements of the opti-

mal solution. More generally, to better understand the solution space, let’s create a graph of

all permissible transitions: establish a node i for each element ai, and add directed edges (i, j)

whenever it is possible for ai and aj to be consecutive elements in an increasing subsequence, that is, whenever 14 / 61

i < j and ai < aj (Figure 6.2).

Notice that (1) this graph G = (V, E) is a dag, since all edges (i, j) have i < j, and (2)

there is a one-to-one correspondence between increasing subsequences and paths in this dag.

Therefore, our goal is simply to find the longest path in the dag! Here is the algorithm: for j = 1, 2, . . . , n:

L(j) = 1 + max{L(i) : (i, j) ∈ E} return maxj L(j)

L(j) is the length of the longest path—the longest increasing subsequence—ending at j (plus

1, since strictly speaking we need to count nodes on the path, not edges). By reasoning in the

same way as we did for shortest paths, we see that any path to node j must pass through one

of its predecessors, and therefore L(j) is 1 plus the maximum L(·) value of these predecessors.

If there are no edges into j, we take the maximum over the empty set, zero. And the final

answer is the largest L(j), since any ending position is allowed.

This is dynamic programming. In order to solve our original problem, we have defined a

collection of subproblems {L(j) : 1 ≤ j ≤ n} with the following key property that allows them to be solved in a single pass:

(*) There is an ordering on the subproblems, and a relation that shows how to solve

a subproblem given the answers to “smaller” subproblems, that is, subproblems

that appear earlier in the ordering.

In our case, each subproblem is solved using the relation

L(j) = 1 + max{L(i) : (i, j) ∈ E}, Tìm đường đi dài nhất

S. Dasgupta, C.H. Papadimitriou, and U.V. Vazirani 171

Figure 6.2 The dag of increasing subsequences. 5 2 8 6 3 6 9 7

In this example, the arrows denote transitions between consecutive elements of the opti- mal ▶ solution Làm . Mo thếre gen nàoerally, tìm to bet đượtecr underst đườngand đi the so dài lution nhất spac từ e, let’ cács cre L ate -giáa grap trị? h of

all permissible transitions: establish a node i for each element ai, and add directed edges (i, j)

▶ Ta quản lý các cạnh trên đường đi bởi con trỏ ngược whenever it is possible for prev(j)

ai and aj to be consecutive elements in an increasing subsequence, that is, when giốngever i < như j and a trong i < aj tìm (Figure 6. đường 2). đi ngắn nhất.

Notice that (1) this graph G = (V, E) is a dag, since all edges (i, j) have i < j, and (2) there ▶ is a Dã on y e-to- tối one ưu corre có spon thểdence tìm betwee đượ n c increa theosing su con bseq trỏ uences and ngược pa nàth y. s in this dag.

Therefore, our goal is simply to find the longest path in the dag! Here is the algorithm: for j = 1, 2, . . . , n:

L(j) = 1 + max{L(i) : (i, j) ∈ E} return maxj L(j) 15 / 61

L(j) is the length of the longest path—the longest increasing subsequence—ending at j (plus

1, since strictly speaking we need to count nodes on the path, not edges). By reasoning in the

same way as we did for shortest paths, we see that any path to node j must pass through one

of its predecessors, and therefore L(j) is 1 plus the maximum L(·) value of these predecessors.

If there are no edges into j, we take the maximum over the empty set, zero. And the final

answer is the largest L(j), since any ending position is allowed.

This is dynamic programming. In order to solve our original problem, we have defined a

collection of subproblems {L(j) : 1 ≤ j ≤ n} with the following key property that allows them to be solved in a single pass:

(*) There is an ordering on the subproblems, and a relation that shows how to solve

a subproblem given the answers to “smaller” subproblems, that is, subproblems

that appear earlier in the ordering.

In our case, each subproblem is solved using the relation

L(j) = 1 + max{L(i) : (i, j) ∈ E}, Ta có nên dùng đệ quy?

Có nên dùng đệ quy để tính công thức sau?

L(j) = 1 + max{L(i) : (i, j) ∈ E} 16 / 61 Nội dung

Đường đi ngắn nhất trên DAG Dãy con tăng dài nhất Khoảng cách soạn thảo Bài toán cái túi Nhân nhiều ma trận Đường đi ngắn nhất Tập độc lập trên cây Khoảng cách soạn thảo

▶ Khi chương trình kiểm tra chính tả bắt gặp lỗi chính tả, nó sẽ

tìm trong từ điển một từ gần với từ này nhất.

▶ Ký hiệu thích hợp cho khái niệm gần trong trường hợp này là gì? Ví dụ

Khoảng cách giữa hai xâu SNOWY và SUNNY là gì? S - N O W Y - S N O W - Y S U N N - Y S U N - - N Y Chi phí: 3 Chi phí: 5 18 / 61 Khoảng cách soạn thảo Định nghĩa

Khoảng cách soạn thảo của hai xâu x và y là số tối thiểu phép

toán soạn thảo (xóa, chèn, và thay thế) để biến đổi xâu x thành xâu y. Ví dụ

Biến đổi xâu SNOWY thành xâu SUNNY. S - N O W Y S U N N - Y ▶ chèn U,

▶ thay thế O → N, và ▶ xóa W. 19 / 61

Lời giải quy hoạch động Câu hỏi Bài toán con là gì?

▶ Để tìm khoảng cách soạn thảo giữa hai xâu x[1 . . . m] và y[1 . . . n],

▶ ta xem xét khoảng cách soạn thảo giữa hai khúc đầu

x[1 . . . i] và y[1 . . . j].

▶ Ta gọi đây là bài toán con E(i, j).

▶ Ta cần tính E(m, n). 20 / 61