Preview text:

lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337

How Consumers Respond to Price Changes

The shape of the demand curve indicates how a price change affects the quantity of a good or

service that consumers demand. Consumer responsiveness to price changes is so important that it

has its own measure: the price elasticity of demand. We will calculate the price elasticity of demand

and see why this elasticity matters to all sorts of pricing decisions. The price elasticity of demand is

only one of a family of related concepts that we will find useful as we study consumers’ and

producers’ responses to changes, including the income elasticity of demand, the price elasticity of

supply, and the cross-price elasticity of demand.

We begin with the substitution and income effects, which give the demand curve its shape. The Substitution Effect

When the price of a good increases, an individual will normally buy less of that good and more of

other goods. And when the price of a good decreases, an individual will normally buy more of that

good and less of other goods. This explains why the individual demand curve, which relates an

individual’s consumption of a good to the price of that good, normally obeys the law of demand and slopes downward.

Another way to think about why demand curves slope downward is to focus on opportunity costs.

For simplicity, let’s suppose there are only two goods between which to choose: Good 1 and Good 2.

When the price of Good 1 decreases, an individual doesn’t have to give up as many units of Good 2

in order to buy one more unit of Good 1. That makes it attractive to buy more of Good 1, whose

price has gone down. Conversely, when the price of Good 1 increases, one must give up more units

of Good 2 to buy one more unit of Good 1, so consuming Good 1 becomes less attractive and the consumer buys fewer.

The change in the quantity demanded as the good that has become relatively cheaper is substituted

for the good that has become relatively more expensive is known as the substitution effect. When a

good absorbs only a small share of the typical consumer’s income, as with pillowcases and kites, the

substitution effect is essentially the sole explanation of why the market demand curve slopes

downward. However, there are some goods, like food and housing, that account for a substantial

share of many consumers’ incomes. In such cases, another effect, called the income effect, also comes into play. substitution effect

The substitution effect of a change in the price of a good is the change in the quantity of that good

demanded as the consumer substitutes the good that has become relatively cheaper for the good

that has become relatively more expensive. The Income Effect lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337

Consider the case of a family that spends half of its income on rental housing. Now suppose that the

price of housing increases everywhere. This change will have a substitution effect on the family’s

demand: other things equal, the family will have an incentive to consume less housing — say, by

moving to a smaller apartment — and more of other goods. But, in a real sense, the family will also

be made poorer by that higher housing price — its income will buy less housing than before. When

income is adjusted to reflect its true purchasing power, it is called real income, in contrast to money

income or nominal income, which has not been adjusted.

This reduction in a consumer’s real income will have an additional effect, beyond the substitution

effect, on the amount of housing and other goods the family chooses to buy. The income effect of a

change in the price of a good is the change in the quantity of that good demanded that results from

a change in the overall purchasing power of the consumer’s income when the price of the good changes. income effect

The income effect of a change in the price of a good is the change in the quantity of that good

demanded that results from a change in the consumer’s purchasing power when the price of the good changes AP® ECON TIP

When two terms are similar, you can more easily distinguish them by looking at the definitions next

to each other: The substitution effect comes from a change in the price of one good relative to the

price of another good. The income effect of a price change comes from a change in the purchasing

power of income. An income effect can also result from a change in the actual income received.

For the majority of goods, the income effect of a price change is not important and has no significant

effect on individual consumption. Thus, most market demand curves slope downward solely because

of the substitution effect — end of story. When it does matter, the income effect usually reinforces

the substitution effect. That is, when the price rises on a good that absorbs a substantial share of

income, consumers of that good feel poorer because their purchasing power falls. And for all normal

goods — goods for which demand decreases when income falls — this reduction in real income leads

to a reduction in the quantity demanded and reinforces the substitution effect.

Module 2.1 introduced both normal goods and inferior goods — those goods, such as canned meat

and ramen noodles, for which demand increases when income falls. In the case of an inferior good,

the income and substitution effects work in opposite directions. For example, suppose the price of

canned meat increases. The resulting substitution effect is a decrease in the quantity of canned meat

demanded, because for both normal and inferior goods, the substitution effect of a price increase is

a decrease in the quantity demanded of the good whose price has risen. But the income effect of a

price increase for canned meat is an increase in the quantity demanded. This makes sense because

the price increase lowers the real income of the consumer, and as real income decreases, the

demand for an inferior good increases. lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337

Could the total effect of a price increase — the combination of the income effect and the substitution

effect — ever be an increase in the quantity demanded? In other words, might we see an increase in

the price of ramen noodles lead to an increase in the quantity of ramen noodles demanded? It is

conceivable. If a good were so inferior that the income effect exceeded the substitution effect, an

increase in the price of that good would lead to an increase in the quantity of that good that is

demanded. There is controversy over whether such goods, known as “Giffen goods,” exist at all. If

they do, they are very rare. You can generally assume that the income effect for an inferior good is

smaller than the substitution effect, and so a price increase will lead to a decrease in the quantity

demanded. Next, we will discuss elasticity as a measure of the responsiveness of the quantity demanded to price changes.

Defining and Measuring Elasticity

If the price of a good or service increases, we know from the law of demand that the quantity

demanded will decrease. But by how much will the quantity demanded decrease if the price goes

up? A firm considering a price change would certainly want to know! Economists use the price

elasticity of demand to measure the responsiveness of the quantity demanded to changes in the

price. Elasticity can also be used to measure the responsiveness of any other variable to changes in a

related variable. We will start by looking at the price elasticity of demand and then consider three

other types of elasticities in the next two Modules.

Consider a pharmaceutical company that would like to know whether it could raise its revenue by

raising the price of its drugs. To know this, the company would have to know whether the price

increase would decrease the quantity demanded by a lot or a little. That is, it would have to know

the price elasticity of demand for its products.

Calculating the Price Elasticity of Demand

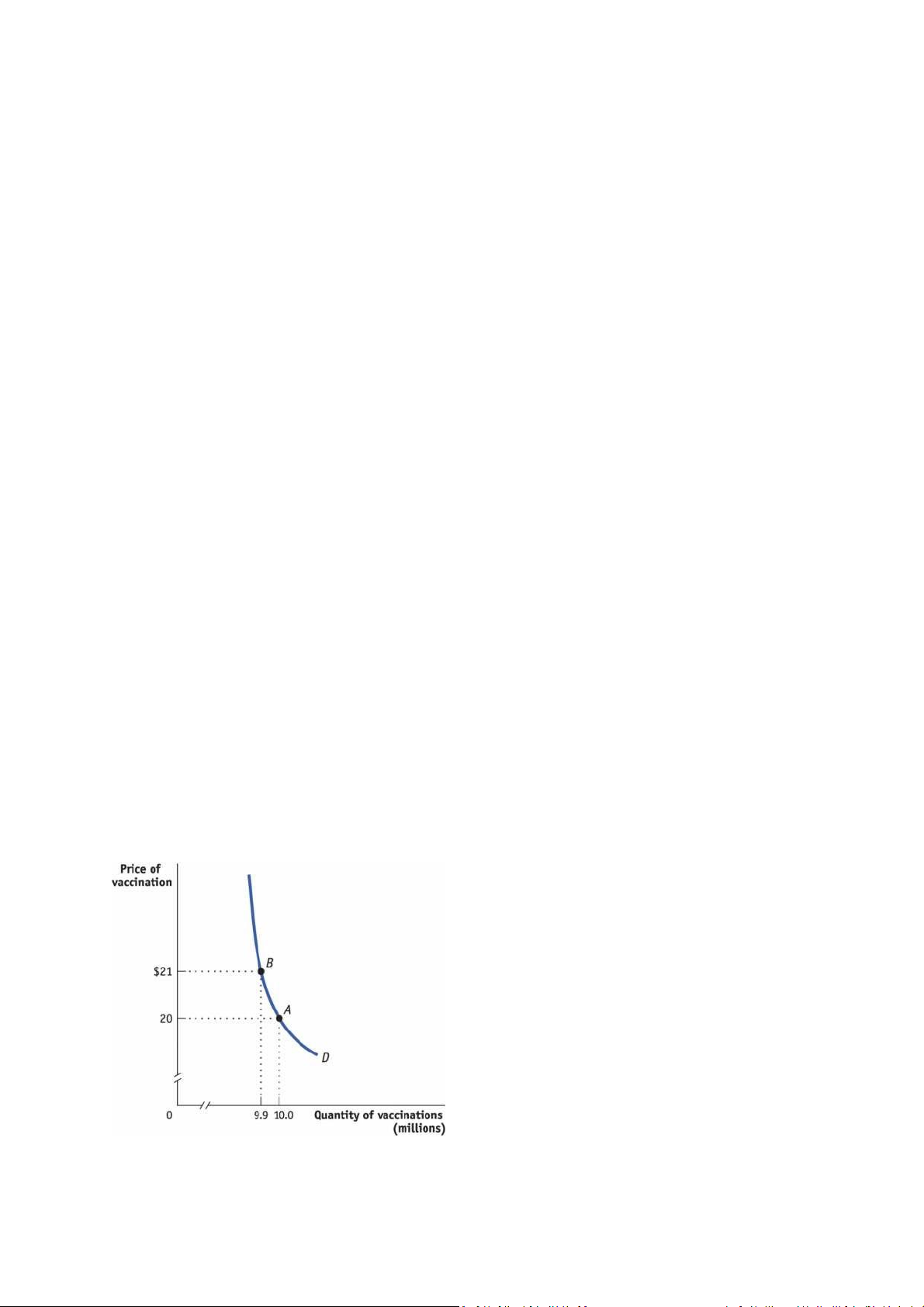

Figure 2.3-1 shows a hypothetical demand curve for a potentially life-saving medical product

purchased by millions of Americans each year, flu vaccinations. At a price of $20 per vaccination,

consumers would demand 10 million vaccinations per year (point A); at a price of $21, the quantity

demanded would fall to 9.9 million vaccinations per year (point B).

Figure 2.3-1, then, tells us the change in the quantity demanded for a particular change in the price.

But how can we turn this information into a measure of price responsiveness? The answer is to lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337

calculate the price elasticity of demand. The price elasticity of demand compares the percentage

change in quantity demanded to the percentage change in price as we move along the demand

curve. As we’ll see later, economists use percentage changes to get a measure that doesn’t depend

on the units involved (say, a child-sized dose versus an adult-sized dose of vaccine). But before we

get to that, let’s look at how elasticity is calculated. price elasticity of demand

The price elasticity of demand is the ratio of the percentage change in the quantity demanded to the

percentage change in the price as we move along the demand curve (dropping the minus sign).

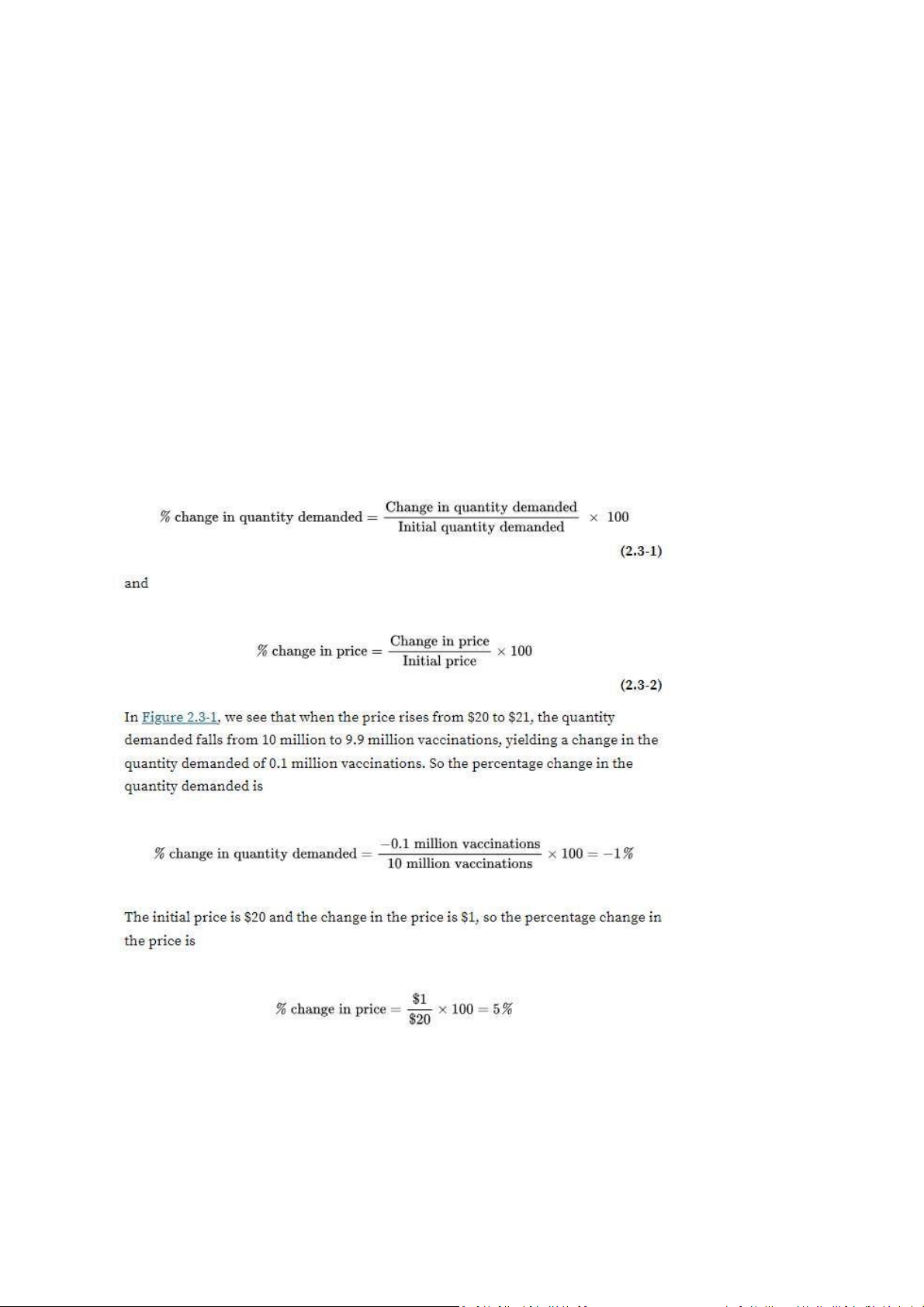

To calculate the price elasticity of demand, we first calculate the percentage change in the quantity

demanded and the corresponding percentage change in the price as we move along the demand

curve. The easiest way to do this, which we will describe as the simple method to distinguish it from

the midpoint method to be discussed a bit later, is as follows: lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337

Notice that we have dropped the minus sign that had been on the percentage change in quantity.

The law of demand tells us that a positive percentage change in the price (a rise in the price) leads to

a negative percentage change in the quantity demanded, and a negative percentage change in the

price (a fall in the price) leads to a positive percentage change in the quantity demanded. This makes

the price elasticity of demand a negative number. However, when economists talk about the price

elasticity of demand, they usually drop the minus sign for convenience and report the absolute value

of the price elasticity of demand. In this case, for example, economists would usually say “the price

elasticity of demand is 0.2,” a kind of shorthand for minus 0.2. We follow that convention here. lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337

The larger the price elasticity of demand, the more responsive the quantity demanded is to the price.

When the price elasticity of demand is large — when consumers change their quantity demanded by

a large percentage compared with the percentage change in the price — economists say that demand is highly elastic.

As we’ll see shortly, a price elasticity of 0.2 indicates a small response of the quantity demanded to

the price. That is, the quantity demanded will fall by a relatively small amount when the price rises.

This is what economists call inelastic demand. Later in this Module, we’ll see why inelastic demand is

exactly what a pharmaceutical company needs to succeed with a strategy to increase revenue by

raising the price of its flu vaccines.

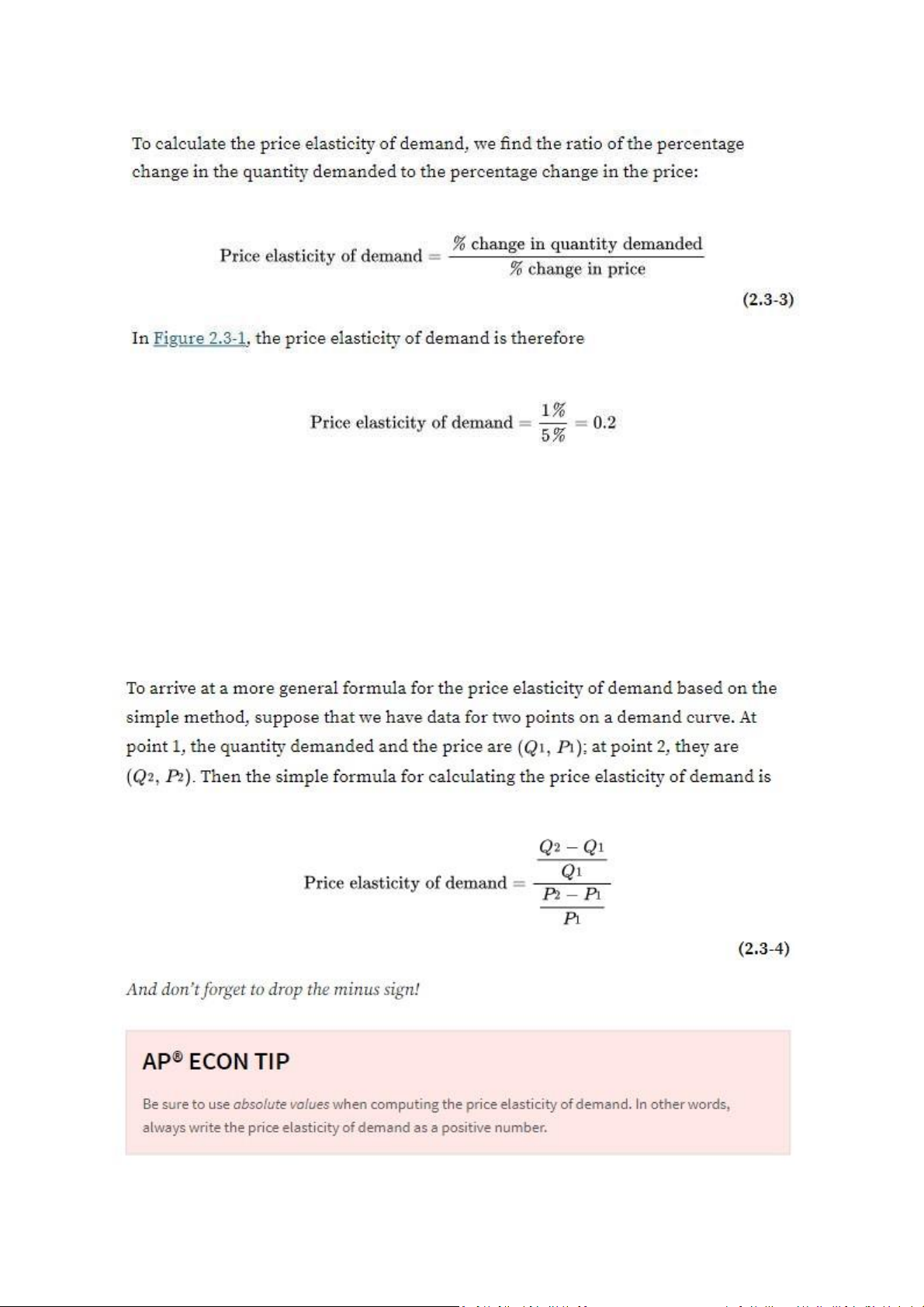

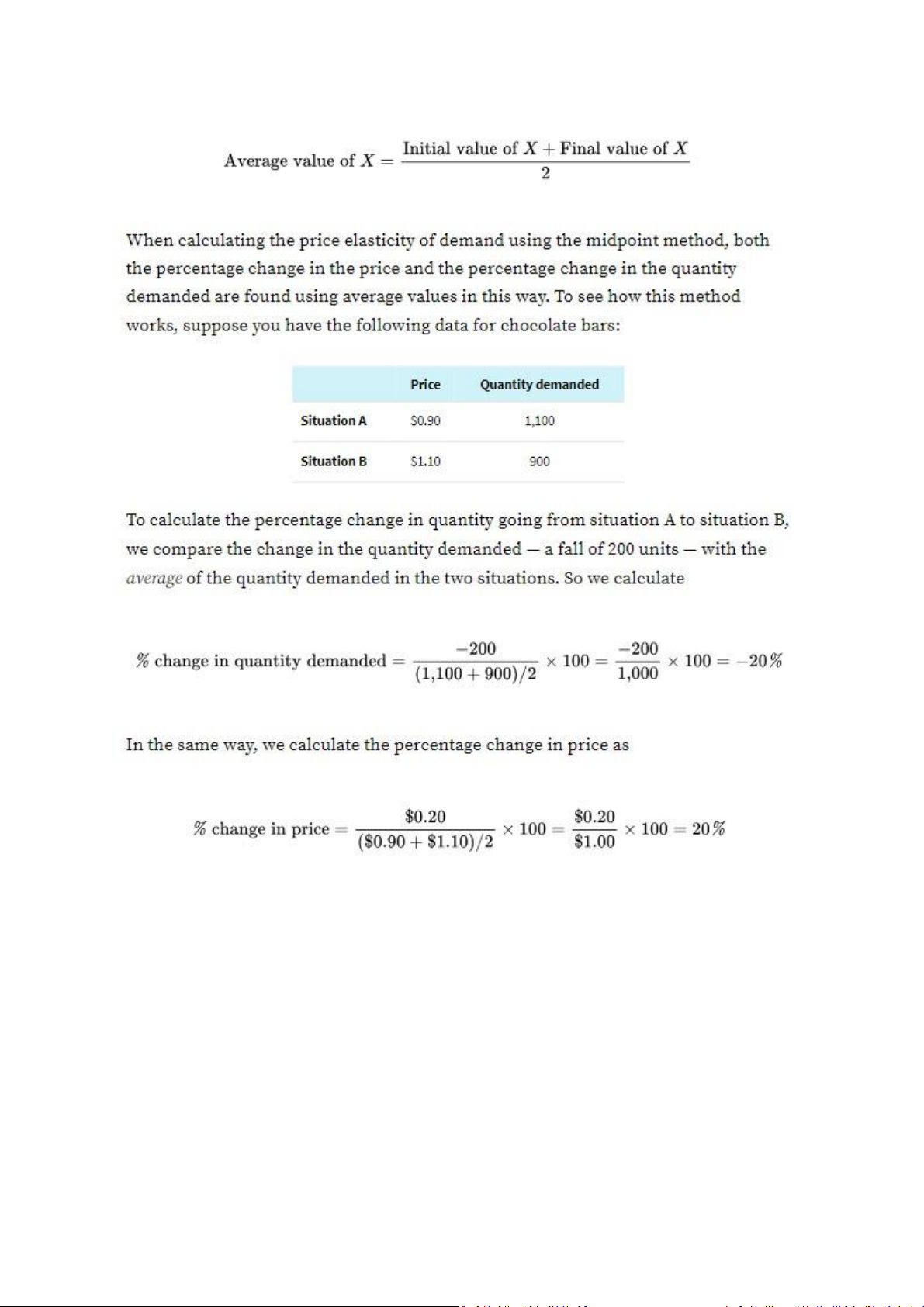

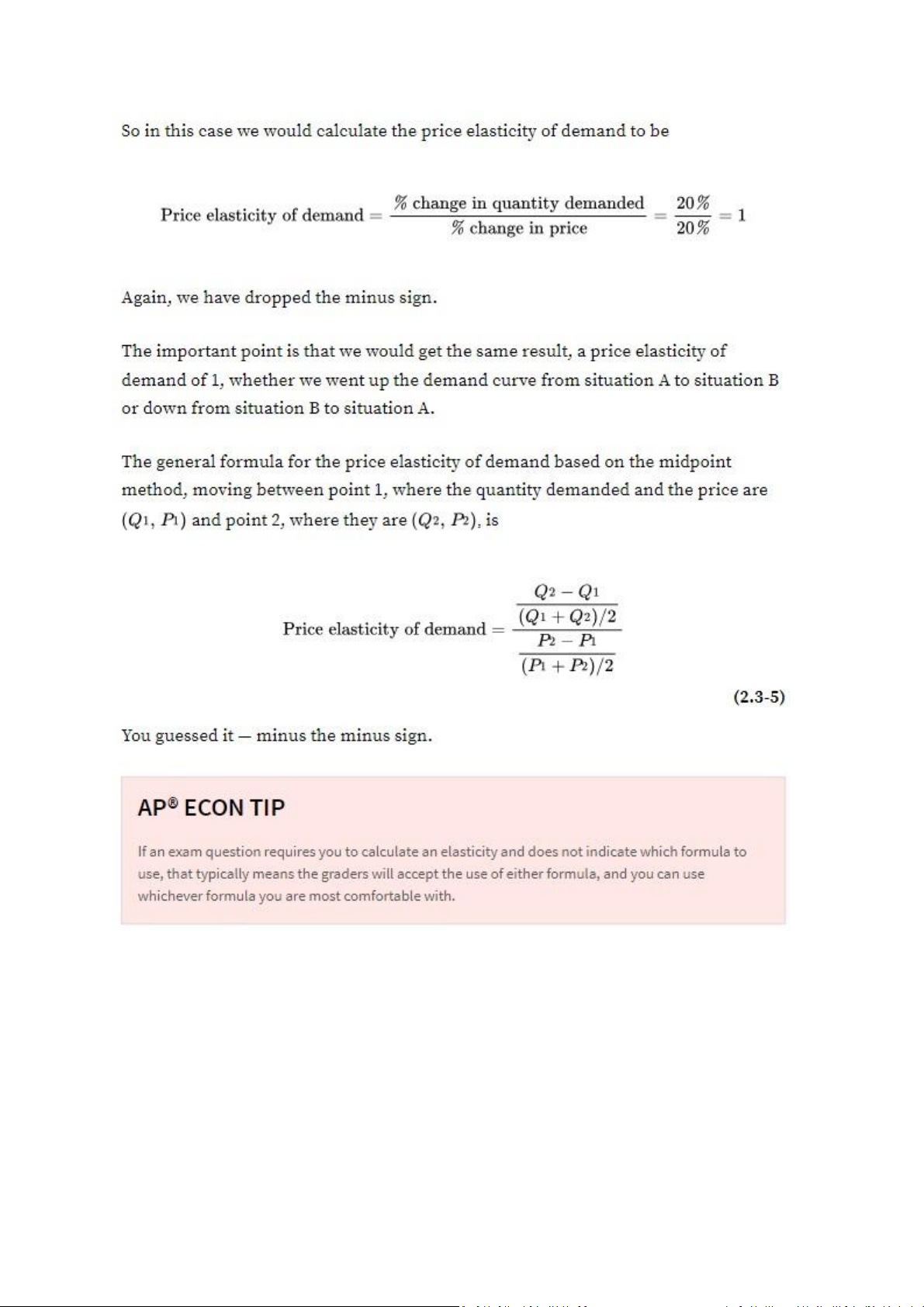

An Alternative Way to Calculate Elasticities: The Midpoint Method

At this point we need to discuss a technical issue that arises when you calculate percentage changes

in variables and how economists deal with it. In our previous example, we found an elasticity of

demand for vaccinations of 0.200 when considering a movement from point A to point B. However,

when going from point B to point A, the same elasticity formula would indicate an elasticity of 0.212

(for useful practice, try this calculation). This is a nuisance: we’d like to have an elasticity measure

that doesn’t depend on the direction of change. A good way to avoid computing different elasticities

for rising and falling prices is to use the midpoint method (sometimes called the arc method).

Using the midpoint method, we calculate the percentage change by dividing the change in a variable

by the average, or midpoint, of the initial and final values of that variable. So the average value of a variable, X, is defined as lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 Elasticity Estimates

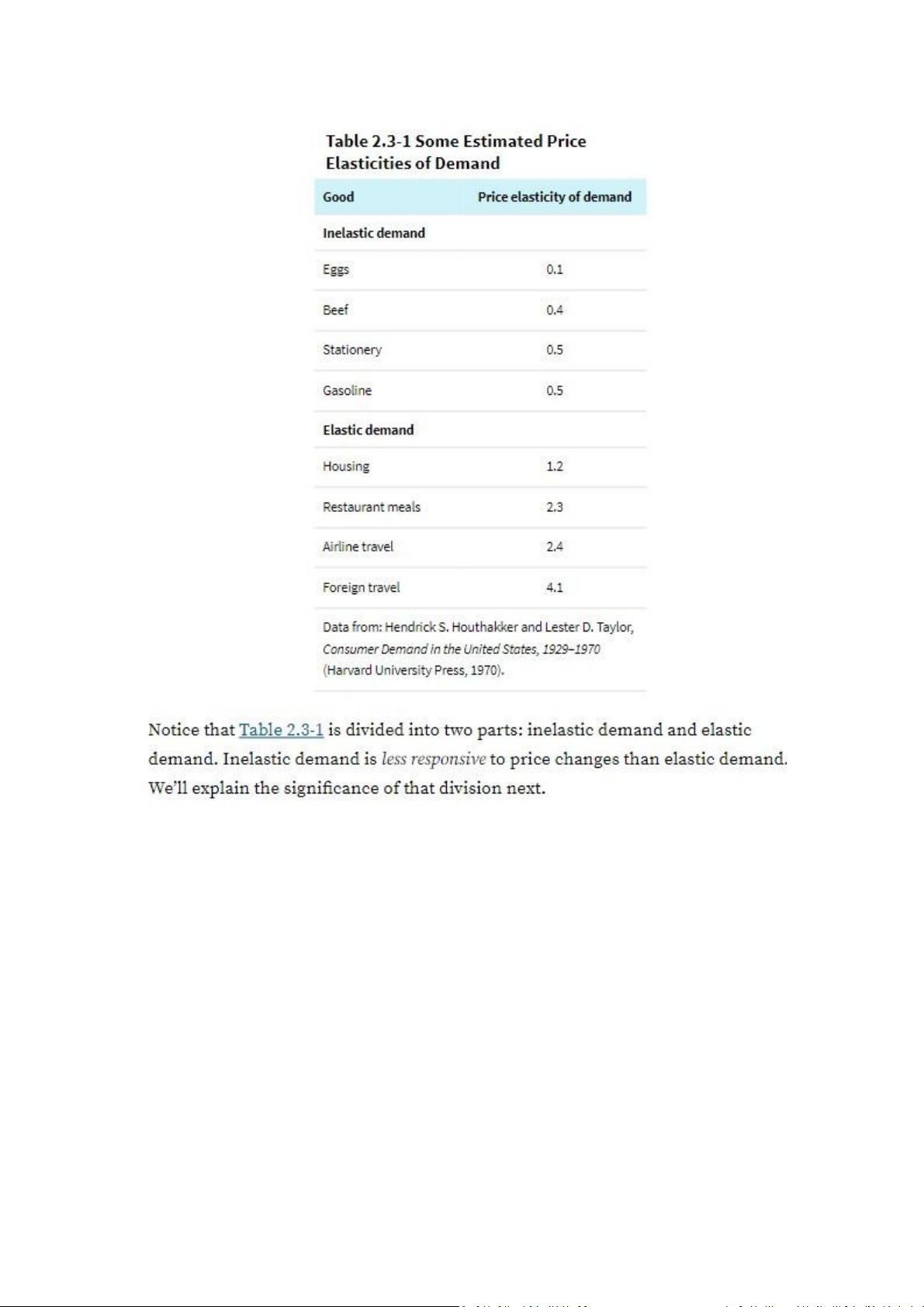

In 1970, economists Hendrik S. Houthakker and Lester D. Taylor published a comprehensive study

that estimated the price elasticities of demand for a wide variety of goods. Some of their results are

summarized in Table 2.3-1. These estimates show a wide range of price elasticities. There are some

goods, such as eggs, for which demand hardly responds at all to changes in the price; there are other

goods, most notably foreign travel, for which the quantity demanded is very sensitive to the price. lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337

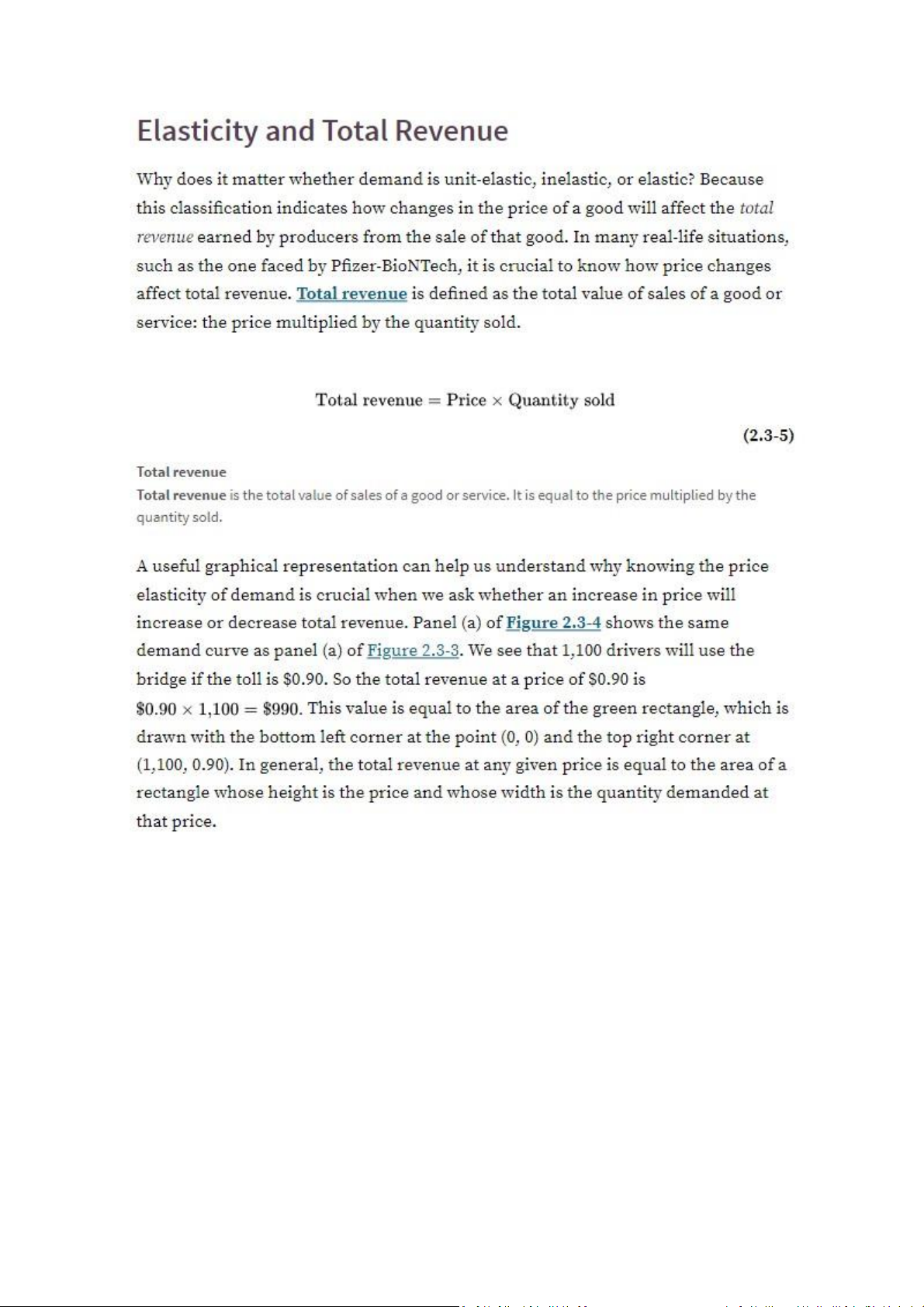

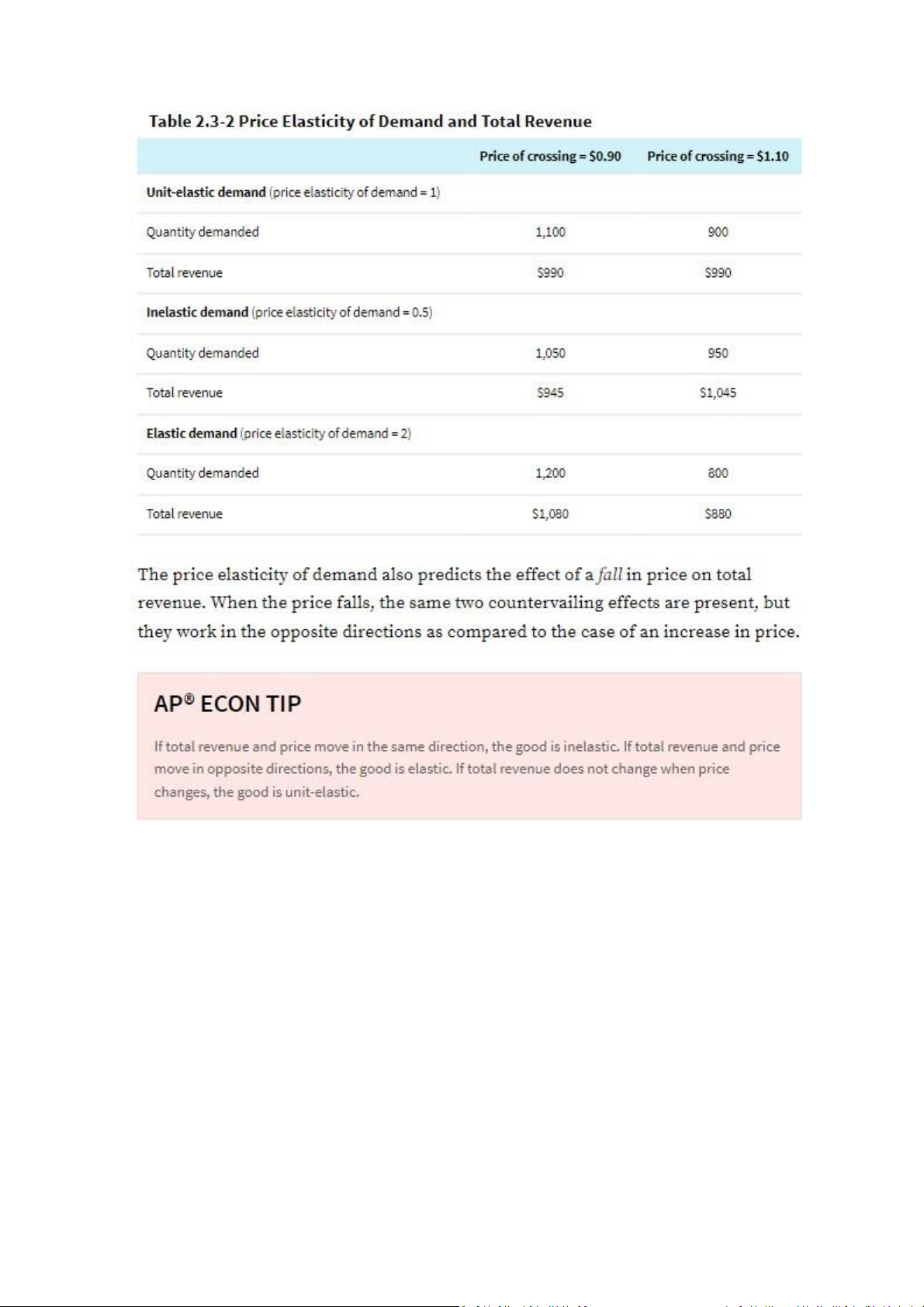

What the Price Elasticity of Demand Tells Us

Well into the coronavirus pandemic, Pfizer-BioNTech raised the price of its COVID-19 vaccine by

about 25% in some countries because the price elasticity of demand was low. But what does that

mean? How low does a price elasticity have to be for it to be classified as low? How high does it have

to be for it to be considered high? And what determines whether the price elasticity of demand is

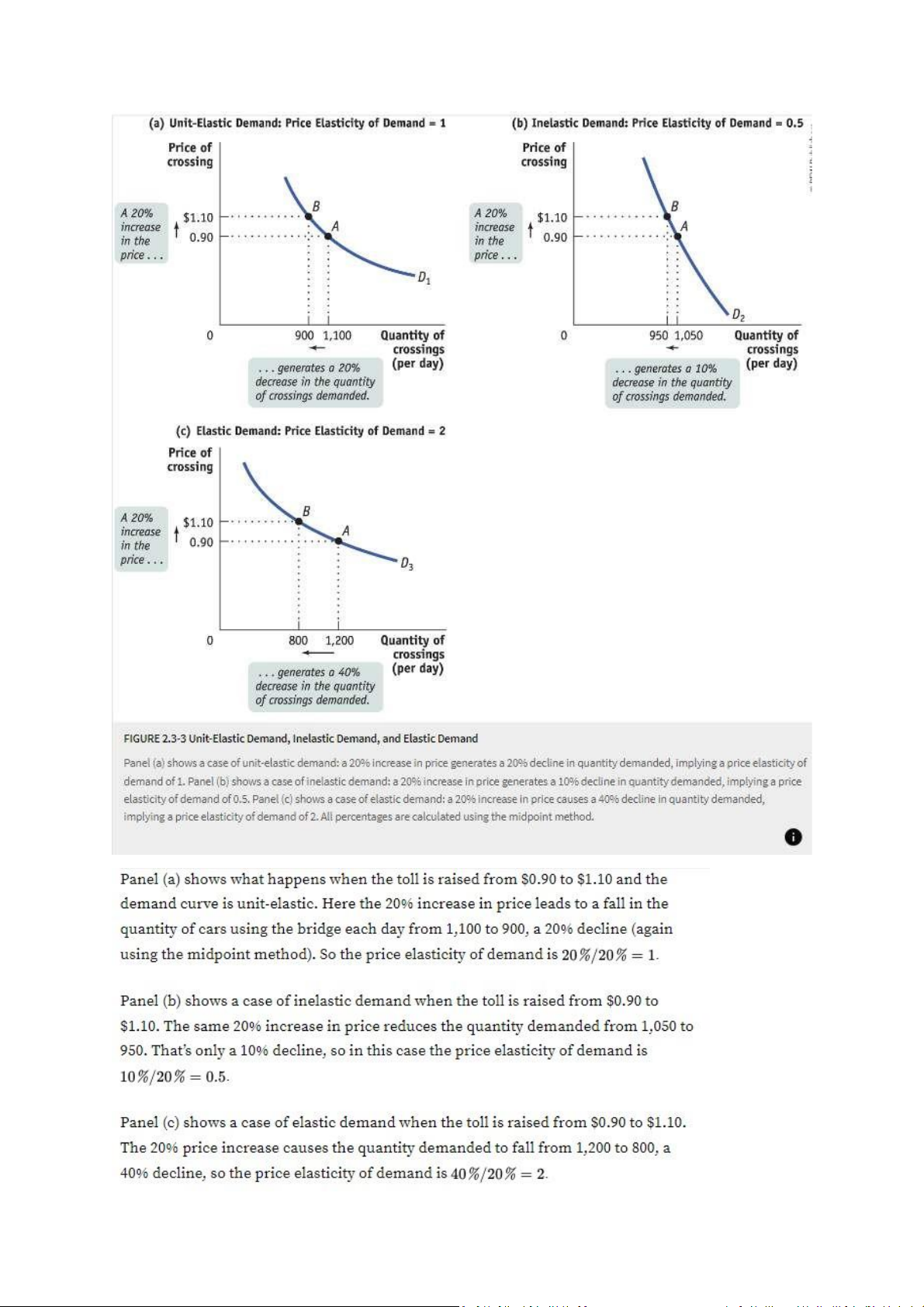

high or low? To answer these questions, we need to look more deeply at the price elasticity of demand. How Elastic Is Elastic?

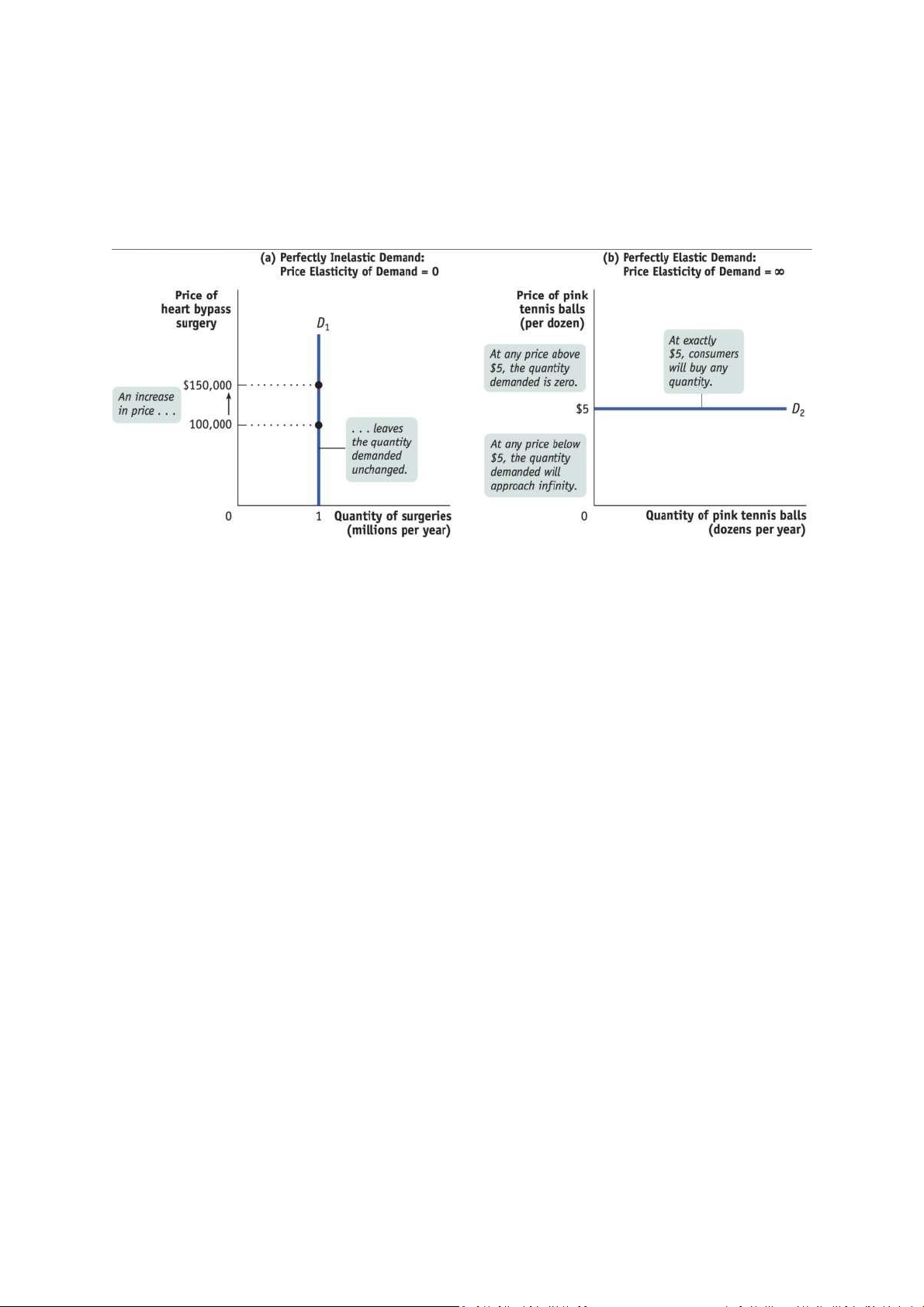

As a first step toward classifying price elasticities of demand, let’s look at two extreme cases. First,

consider the demand for a good when people pay no attention to its price. Suppose, for example, lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337

that consumers would buy 1 million heart bypass surgeries per year regardless of the price. If that

were true, the demand curve for these surgeries would look like the curve shown in panel (a) of

Figure 2.3-2: it would be a vertical line at 1 million heart bypass surgeries. Since the percentage

change in the quantity demanded is zero for any change in the price, the price elasticity of demand

in this case is zero. The case of a zero price elasticity of demand is known as perfectly inelastic demand. perfectly inelastic

Demand is perfectly inelastic when the quantity demanded does not respond at all to changes in the

price. When demand is perfectly inelastic, the demand curve is a vertical line.

The opposite extreme occurs when even a tiny rise in the price will cause the quantity demanded to

drop to zero or when even a tiny fall in the price will cause the quantity demanded to get extremely

large. Panel (b) of Figure 2.3-2 shows the case of pink tennis balls; we suppose that tennis players

don’t have a color preference, and that other tennis ball colors, such as neon green and vivid yellow,

are available at $5 per dozen balls. In this case, consumers will buy no pink tennis balls if they cost

more than $5 per dozen. But if pink tennis balls cost less than $5 per dozen, consumers will buy no

other color. The demand curve will therefore be a horizontal line at a price of $5 per dozen. If the

price falls from above $5 to below $5, the quantity demanded will rise from zero to a number

approaching infinity. So a horizontal demand curve implies an infinite price elasticity of demand.

When the price elasticity of demand is infinite, economists say that demand is perfectly elastic. perfectly elastic

Demand is perfectly elastic when any price increase will cause the quantity demanded to drop to

zero. When demand is perfectly elastic, the demand curve is a horizontal line.

The price elasticity of demand for the vast majority of goods is somewhere between these two

extreme cases. Economists use one level of magnitude for classifying these intermediate cases: they

ask whether the price elasticity of demand is greater or less than 1. When the price elasticity of

demand is greater than 1, economists say that demand is elastic. When the price elasticity of

demand is less than 1, they say that demand is inelastic. The borderline case is unit-elastic demand,

where the price elasticity of demand is — surprise — exactly 1. lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337

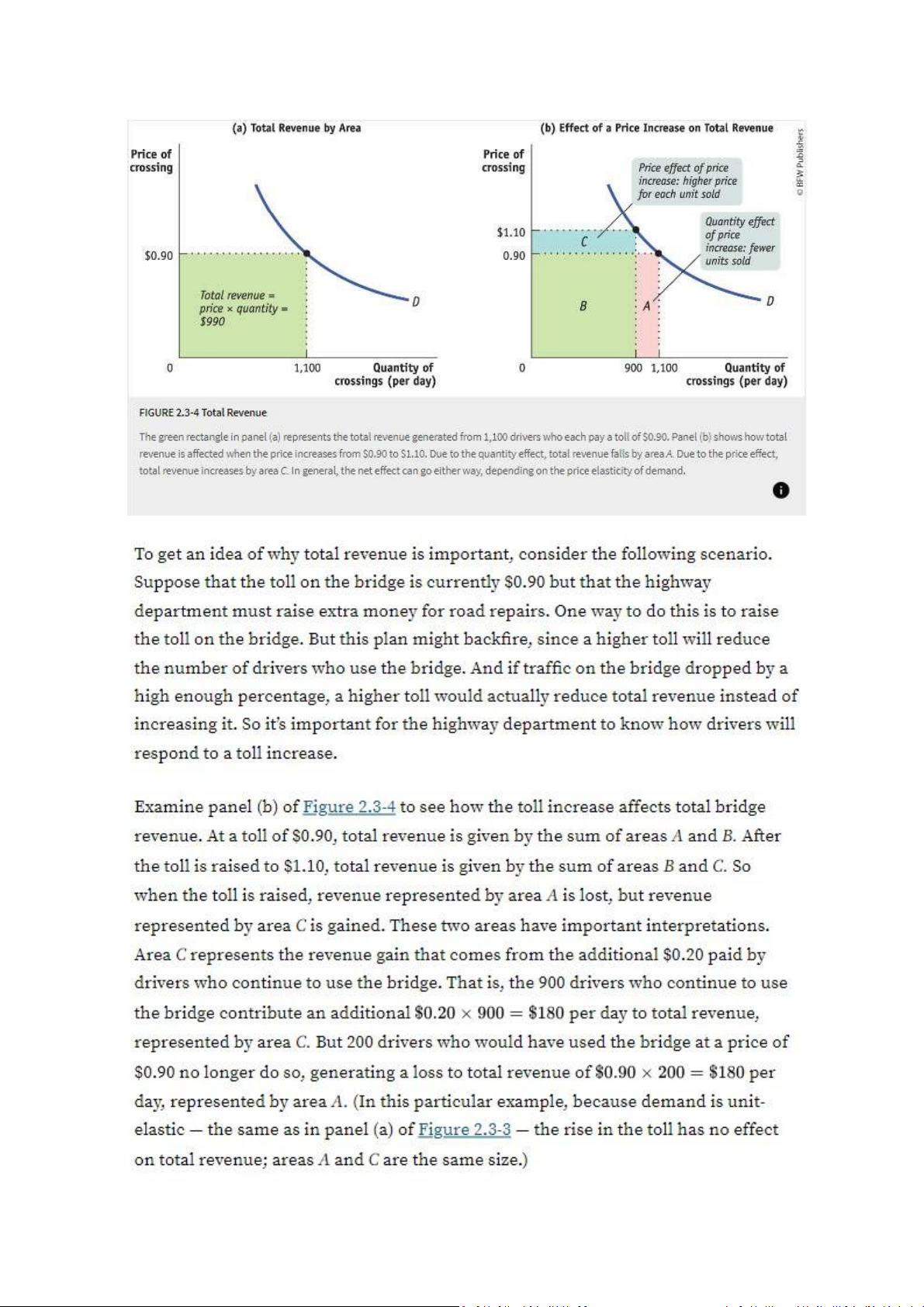

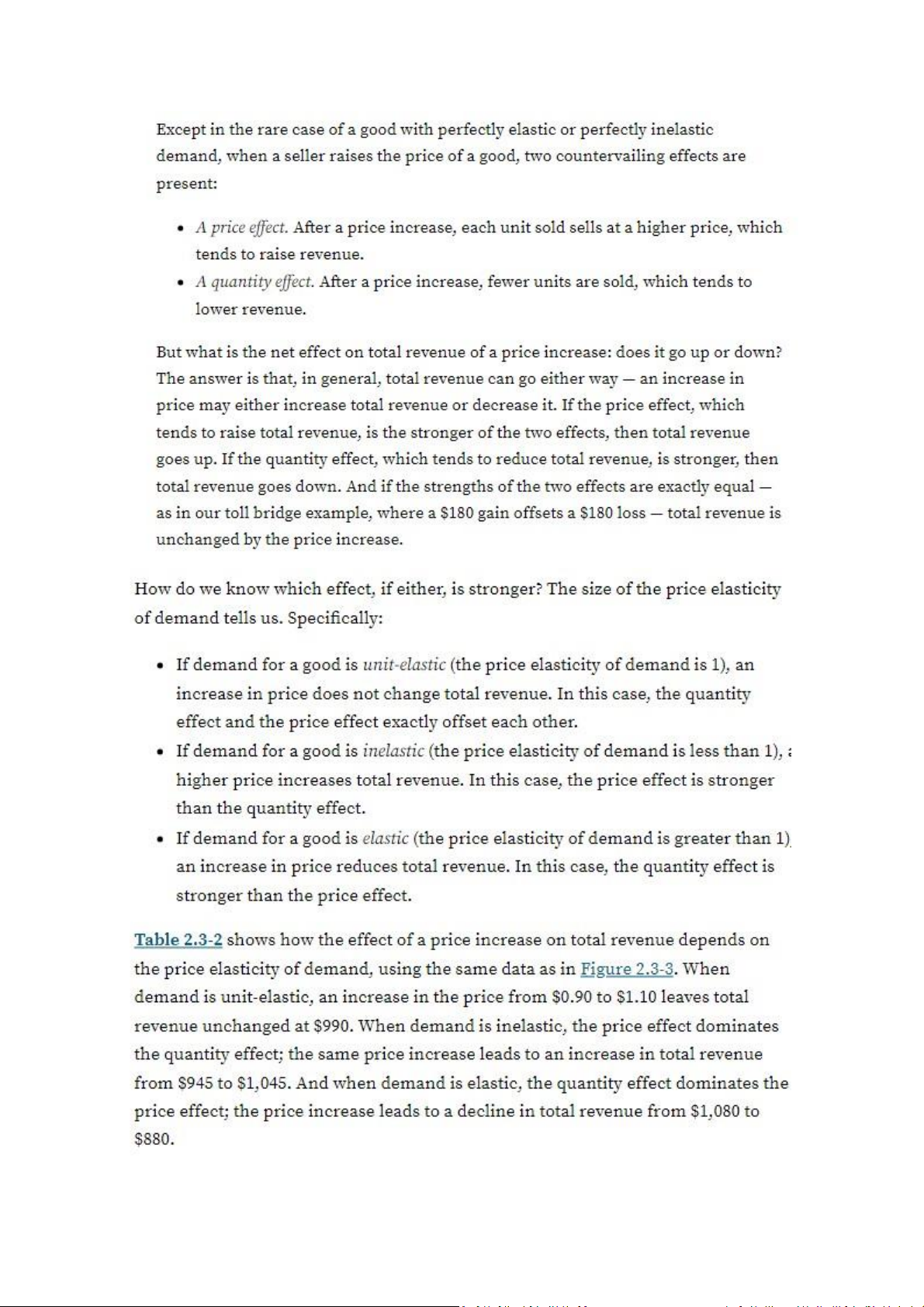

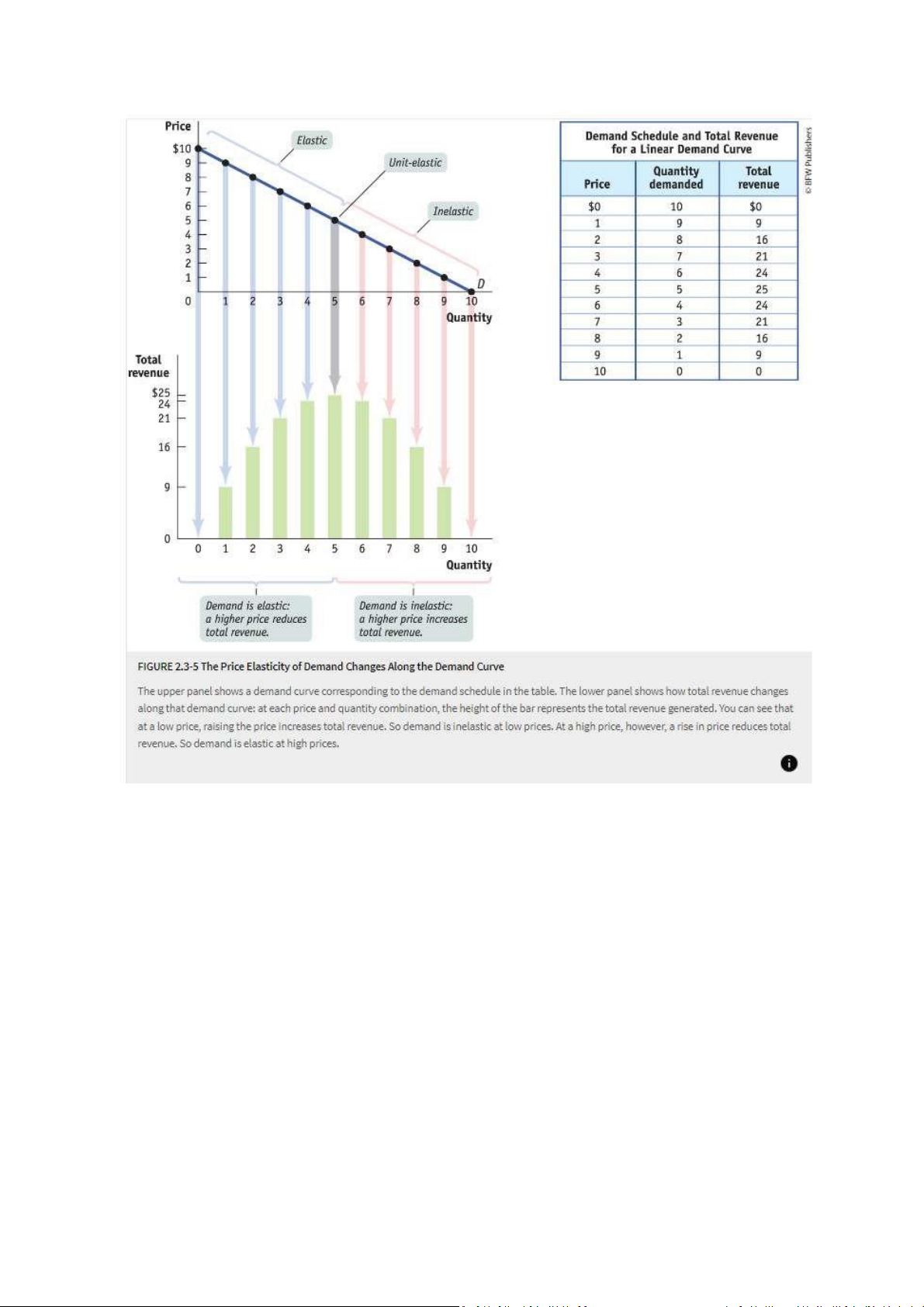

In Figure 2.3-5, you can see that when the price is low, raising the price increases total revenue:

starting at a price of $1, raising the price to $2 increases total revenue from $9 to $16. This means

that when the price is low, demand is inelastic. Moreover, you can see that demand is inelastic on

the entire section of the demand curve where the price is below $5. AP® ECON TIP

For a straight, downward-sloping demand curve, the upper left segment of the demand curve is

elastic and the bottom right segment is inelastic.

When the price is high, however, raising it further reduces total revenue: starting at a price of $8, for

example, raising the price to $9 reduces total revenue from $16 to $9. This means that when the

price is high, demand is elastic. Furthermore, you can see that demand is elastic over the section of

the demand curve where the price exceeds $5. lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337

For the vast majority of goods, the price elasticity of demand changes along the demand curve. So

whenever you measure a good’s elasticity, you are really measuring it at a particular point or section of the good’s demand curve.

What Factors Determine the Price Elasticity of Demand?

Pfizer-BioNTech was able to significantly raise its price for COVID-19 vaccines for several important

reasons: there were few substitutes, the price was a small fraction of the typical consumer’s income,

and many people considered them a medical necessity. Over time, some people were able to find

providers of alternative vaccines with lower prices. This experience illustrates the four main factors

that determine elasticity: whether close substitutes are available, the share of income a consumer

spends on the good, whether the good is a necessity or a luxury, and how much time has elapsed

since the price change. Let’s look at each of these factors in detail.

Whether Close Substitutes Are Available

The price elasticity of demand tends to be high if there are other goods that consumers regard as

similar and would be willing to consume instead. The price elasticity of demand tends to be low if

there are no close substitutes.

Share of Income Spent on the Good

The price elasticity of demand tends to be low when spending on a good accounts for a small share

of a consumer’s income. In that case, a significant change in the price of the good has little impact on

how much the consumer spends. In contrast, when a good accounts for a significant share of a

consumer’s spending, the consumer is likely to be very responsive to a change in price. In this case,

the price elasticity of demand is high.

Whether the Good Is a Necessity or a Luxury

The price elasticity of demand tends to be low if a good is something you must have, like a life-saving

medicine, or something you feel like you must have due to an addiction. The price elasticity of

demand tends to be high if the good is a luxury — something you can easily live without. Time

In general, the price elasticity of demand tends to increase as consumers have more time to adjust to

a price change. This means that the long-run price elasticity of demand is often higher than the short-run elasticity. AP® ECON TIP

Use the mnemonic SPLAT to help remember that the determinants of price elasticity of demand are:

Substitutes, Proportion of income, Luxury or necessity, Addictive or habit forming, and Time. lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337

A good illustration of the effect of time on the elasticity of demand is drawn from dramatic increases

in gasoline prices, which occurred in the United States in 2011 and 2021. Initially, consumption fell

very little because there were no close substitutes for gasoline and because people needed to drive

their cars to carry out the ordinary tasks of life. Over time, however, Americans changed their

carbuying and driving habits in ways that enabled them to gradually reduce their gasoline

consumption. Within two years of the 2011 increase, the average household used 19% less gasoline,

and the average vehicle used 14% less gasoline than they had a decade earlier, confirming that the

long-run price elasticity of demand for gasoline was indeed much higher than the short-run elasticity.

The 2021 increase was followed by burgeoning interest in electric vehicles.