Preview text:

P A R T 3 CH 9 Managerial Decision Making

E Types of Decisions and Problems

S After studying this chapter, you should be able to: E Programmed and Nonprogrammed

1. Compare and contrast programmed and nonprogrammed IN Decisions IV

decisions, including how they relate to the presence of

TL Facing Uncertainty and Ambiguity T

certainty, uncertainty, and ambiguity. U C Decision-Making Models

2. Compare the ideal, rational model of decision making to the JE O

political model of decision making. The Ideal, Rational Model B How Managers Make Decisions

3. Summarize the six steps used in managerial decision making. O TER The Political Model

4. Describe four personal decision styles used by managers. P Decision-Making Steps A

5. Identify the biases that frequently cause managers to make

Recognition of Decision Requirement H NING bad decisions.

C Diagnosis and Analysis of Causes

R 6. Explain innovative techniques for decision making, including Development of Alternatives A

brainstorming, evidence-based management, and after-action

Selection of the Desired Alternative E L reviews.

Implementation of the Chosen Alternative Evaluation and Feedback Personal Decision Framework Why Do Managers Make Bad Decisions? Innovative Decision Making Start with Brainstorming Use Hard Evidence Engage in Rigorous Debate Avoid Groupthink Know When to Bail Do a Premortem and Postmortem

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 1 How Do You Make Decisions?

INSTRUCTIONS: Most of us make decisions automatically, without realizing that people have diverse decision-making INTRODUCTION

behaviors, which they bring to management positions.1 Think back to how you make decisions in your

personal, student, or work life, especially where other people are involved. Identify whether each of 2

the following items is Mostly True or Mostly False for you. Mostly True Mostly False

1. I like to decide quickly and move on to the next thing. __________ __________

2. I would use my authority to make a decision if I’m certain I am right. __________ __________ 3. I appreciate decisiveness. __________ __________ ENVIRONMENT

4. There is usually one correct solution to a problem. __________ __________

5. I identify everyone who needs to be involved in the decision. __________ __________ 3

6. I explicitly seek conflicting perspectives. __________ __________

7. I use discussion strategies to reach a solution. __________ __________

8. I look for different meanings when faced with a great deal of data. __________ __________

9. I take time to reason things through and use systematic logic. __________ __________ PLANNING

SCORING AND INTERPRETATION: All nine items in the list reflect appropriate decision-making behavior, but

items 1–4 are more typical of new managers. Items 5–8 are typical of successful senior-manager deci-

sion making. Item 9 is considered part of good decision making at all levels. If you checked “Mostly 4

True” for three or four of items 1–4 and 9, consider yourself typical of a new manager. If you checked

“Mostly True” for three or four of items 5–8 and 9, you are using behavior consistent with top man-

agers. If you checked a similar number of both sets of items, your behavior is probably flexible and balanced.

New managers typically use a different decision behavior than seasoned executives. The decision

behavior of a successful CEO may be almost the opposite that of a first-level supervisor. The differ- ng

ence is due partly to the types of decisions faced at each level and partly to learning what works at ORGANIZING

each level. New managers often start out with a more directive, decisive, command-oriented behavior

to establish their standing and decisiveness and gradually move toward more openness, diversity of rganizi O

viewpoints, and interactions with others as they move up the hierarchy. 5

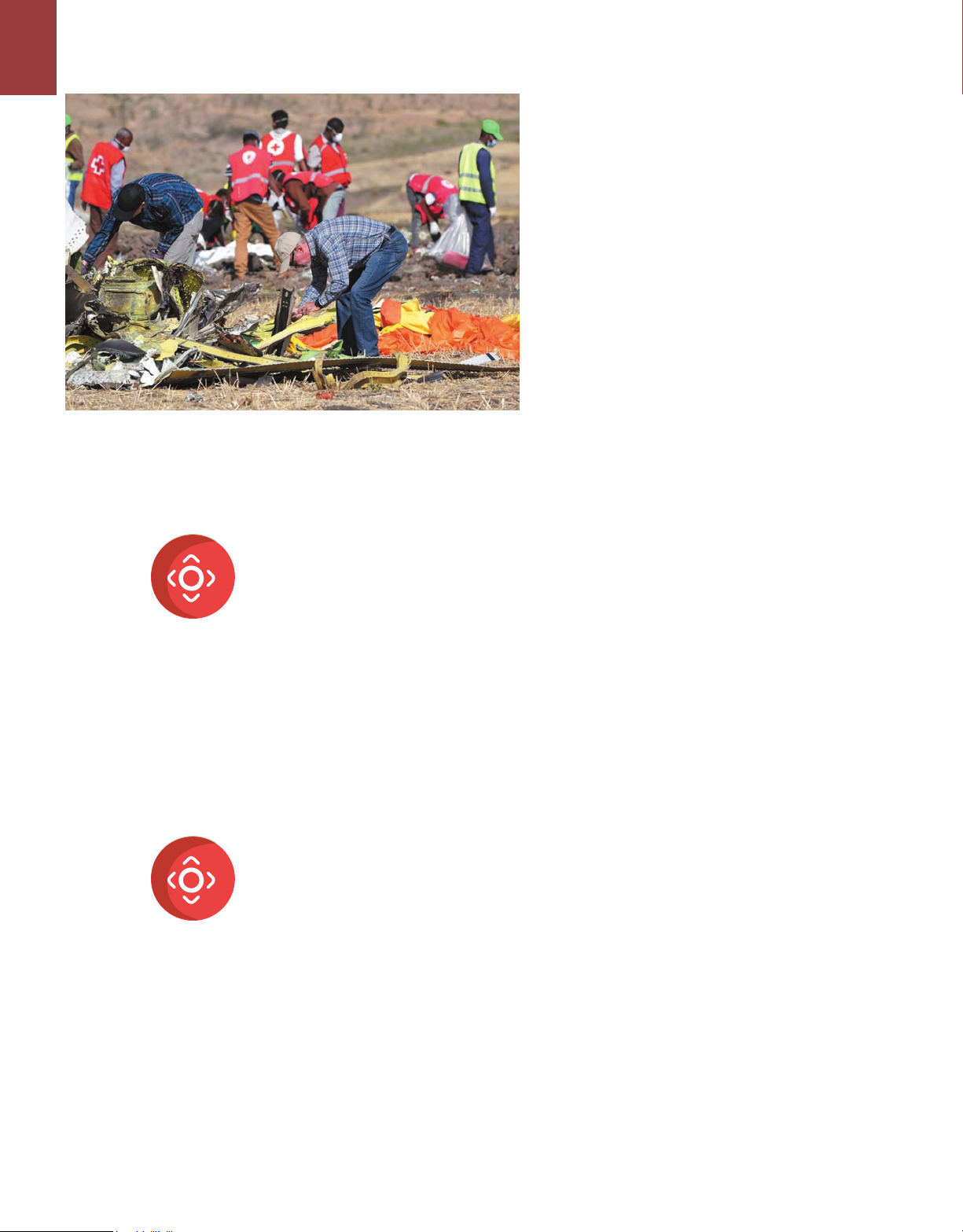

At the start of 2019, Boeing had won more orders for the 737 MAX jetliner than

for any model in the company’s history. Less than three months later, the plane LEADING

was grounded and Boeing was in the middle of a crisis, trying to explain two fatal

crashes that caused 350 deaths. Federal prosecutors, securities regulators, aviation authori-

ties, and U.S. lawmakers have been looking into the managerial decision making that went

into development of the 737 MAX.

Feeling intense competitive pressure owing to the popularity of the emerging fuel- 6

efficient A320neo jets from European rival Airbus, managers and executives at Boeing SNAPSHOT

made a number of fateful decisions, including the following:

• Modify the current 737 model into the competitive fuel-efficient 737 MAX design,

which would be cheaper and faster than building an entirely new aircraft, partly

because the FAA’s approval process is shorter for a modified design. CONTROLLING

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 286 PART 3 PLANNING

• Avoid adding components or systems that

would unnecessarily increase Boeing’s costs

or require additional simulator training for

pilots from airline purchasers worldwide.

• Add MCAS (Maneuvering Characteristic

Augmentation System) to address prob-

lems caused by the larger fuel-efficient

engines being moved forward under the ty Images wings. ws/Get

• Not tell airlines or cockpit crews about

MCAS because pilots of earlier 737 mod- ty Images Ne

els would be able to counteract any MCAS

problems by implementing long-standing ess/Get procedures. ount

Boeing managers would never knowingly Jemal C

sacrifice safety for profits, but the outcome of

these and a multitude of other decisions, as reported in the media, appeared to result in

the crash of Lion Air Flight 610 in Indonesia and, a few months later, the crash of Ethio-

pia Airlines Flight 320. Both crashes killed all aboard. The 737 MAX was grounded worldwide.2

Welcome to the world of managerial decision making. Every organization—whether it

is Boeing, Twitter, the American Red Cross, JPMorgan Chase, or the city of Newark, New

Jersey—grows, prospers, or fails as a result of decisions made by its managers. In Newark, SNAPSHOT

a string of questionable decisions by Mayor Ras Baraka and other city leaders created

a major environmental crisis for the city. After receiving test results showing alarming

levels of lead in the city’s drinking water, city officials initially brushed aside the warn-

ings and allowed the system to continue to deteriorate. At JPMorgan Chase, a decision

to attract younger customers with a new digital-banking app called Finn proved to be

a disappointment and the company closed down Finn to concentrate on strengthening

the extant Chase mobile app.3 Decision making, particularly in relation to complex prob-

lems, is not always easy. It is easy to look back and identify flawed decisions, but managers

frequently make decisions amid ever-changing factors, unclear information, and conflicting

points of view. Managers can sometimes make the wrong decision, even when their inten- tions are right.

The business world is full of evidence of both good and bad decisions. YouTube was

once referred to as “Google’s Folly,” but decisions made by the video platform’s managers

have more than justified the $1.65 billion that Google paid for it and turned YouTube

into a highly admired company that is redefining the entertainment industry.4 In contrast, SNAPSHOT

Caterpillar’s decision to purchase China’s ERA Mining Machinery Ltd. didn’t work out

so well. After paying $700 million for the company, Caterpillar managers said less than

a year later that they would write down ERA’s value by $580 million. The company

blamed deliberate accounting misconduct that was designed to overstate profits at the

firm’s mine-safety equipment unit.5

Good decision making is a vital part of good management because decisions deter-

mine how the organization solves problems, allocates resources, and accomplishes its

goals. This chapter describes decision making in detail. We will look at several decision-

making models and the steps managers should take when making important deci-

sions. The chapter also explores some biases that can cause managers to make bad

decisions and examines some specific techniques for innovative decision making in a fast-changing environment.

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

CHAPTER 9 MANAGERIAL DECISIoN MAKING 287

9-1 Types of Decisions and Problems

A decision is a choice made from available alternatives. For example, an accounting man-

ager’s selection among Colin, Tasha, and Carlos for the position of junior auditor is a deci-

sion. Many people assume that making a choice is the major part of decision making, but it is only a part of it.

Decision making is the process of identifying problems and opportunities and then resolv-

ing them. Decision making involves effort both before and after the actual choice. Thus, the

decision of whether to select Colin, Tasha, or Carlos requires the accounting manager to ascer-

tain whether a new junior auditor is needed, determine the availability of potential job candi-

dates, interview candidates to acquire necessary information, select one candidate, and fol ow up

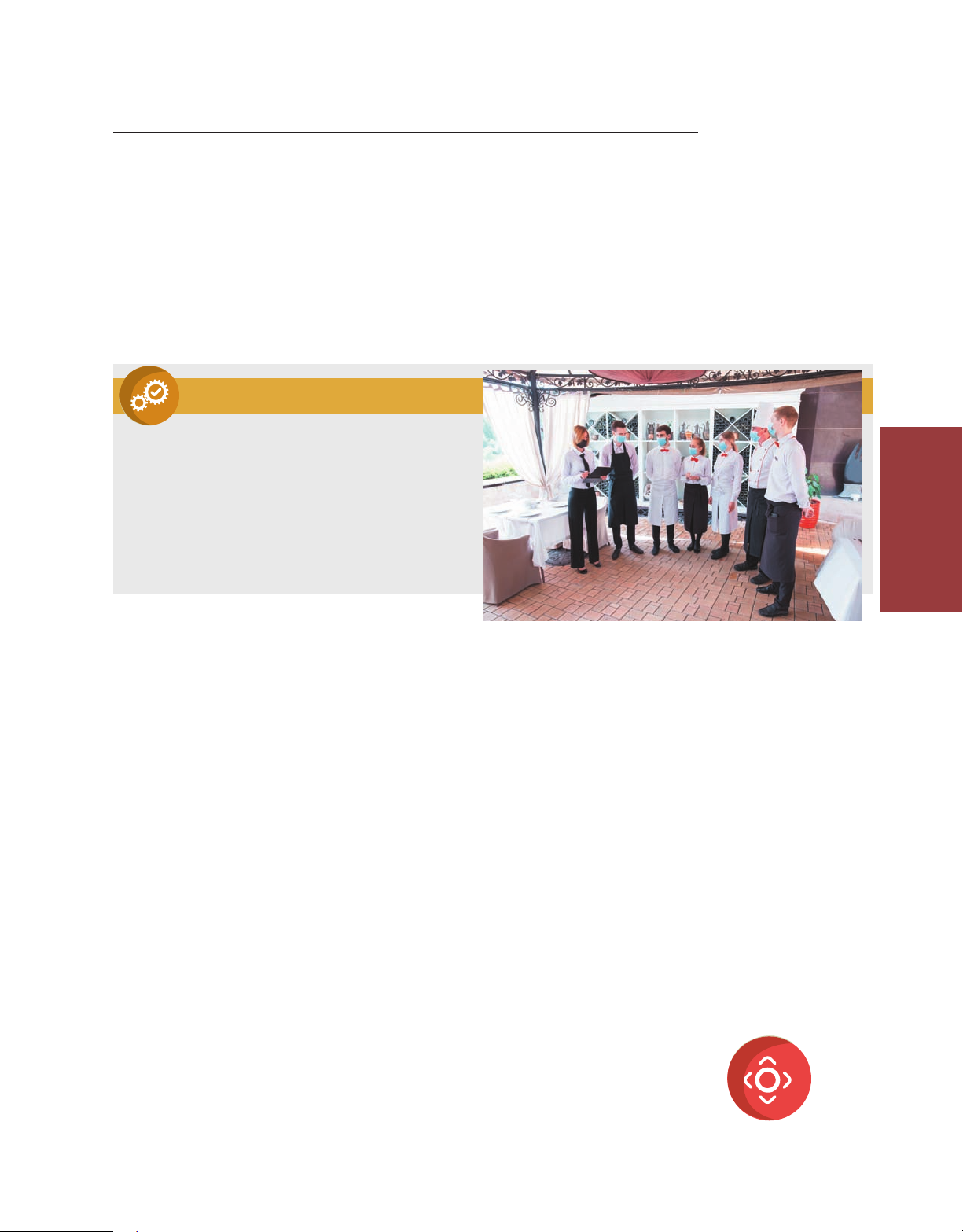

with the socialization of the new employee into the organization to ensure the decision’s success. Concept Connection

Daily meetings among restaurant managers 3

and staff took on new urgency in 2020 as they

worked to keep customers and employees safe k.com

from COVID-19. Business owners around the oc st

world faced nonprogrammed decisions ter

regarding when and how to reopen their busi- ey/Shut

nesses in the midst of the pandemic. PLANNING o Andr enk Nor

9-1A PROGRAMMED AND NONPROGRAMMED DECISIONS

Management decisions typically fall into one of two categories: programmed and nonpro-

grammed. Programmed decisions involve situations that have occurred often enough to

enable decision rules to be developed and applied in the future.6 Such decisions are made in

response to recurring organizational problems. For example, the decision to reorder paper

and other office supplies when inventories drop to a certain level is a programmed deci-

sion. Other programmed decisions concern the types of skills required to fill certain jobs,

the reorder point for manufacturing inventory, and selection of freight routes for product

deliveries. Once managers formulate decision rules, subordinates and others can make the

decision, thus freeing managers for other tasks. For example, when staffing banquets, many

hotels use a rule that specifies having one server per 30 guests for a sit-down function and

one server per 40 guests for a buffet.7 Today some programmed decisions are handled by

artificial intelligence (AI). For example, Royal Dutch Shell has begun using AI algorithms

in some areas of its business to assign employees with the right skills and expertise to

work on various projects. An algorithm can schedule work more efficiently, freeing up

managers’ time for more complex, nonprogrammed decisions.8

Nonprogrammed decisions are made in response to situations that are unique, are

poorly defined and largely unstructured, and have important consequences for the organiza-

tion. Boeing managers faced numerous nonprogrammed decisions related to the 737 MAX,

described in the chapter’s opening example. Another good example of a nonprogrammed SNAPSHOT

decision comes from Boeing’s rival, Airbus. Airbus executives decided to build a giant

double-decker plane, the Airbus A380, to challenge the dominance of the Boeing 747

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 288 PART 3 PLANNING

as the world’s largest airliner. At the time, a representative said the A380 would “be the

cement of the company for years to come.” But the A380 decision was based on managers’

assumptions that airlines would continue using large hub airports to transfer passengers

between connecting flights and want to fly large four-engine jets on long routes. The

environment changed. Technology advancements enabled Boeing to develop a smaller,

highly efficient twin-engine model, the 787 Dreamliner, which could fly long distances

and bypass giant airports altogether. Airline executives, focused on increasing profits,

wanted these kinds of smaller jets, which were easier to fill with passengers and cheaper

to fly. Airbus eventually developed its own smaller two-engine model. After investing

$17 billion in the A380 project, Airbus got orders for only 251 of the super-jumbo jets

and announced that it would shut down production of the plane at the end of 2021.9

Managers in every industry face nonprogrammed decisions every day. Many nonpro-

grammed decisions, such as the one at Airbus, are related to strategic planning because

uncertainty is great and decisions are complex. Decisions to develop a new product or ser-

vice, acquire a company, create a new division, build a new factory, enter a new geographic

market, or relocate headquarters to another city are all nonprogrammed decisions.

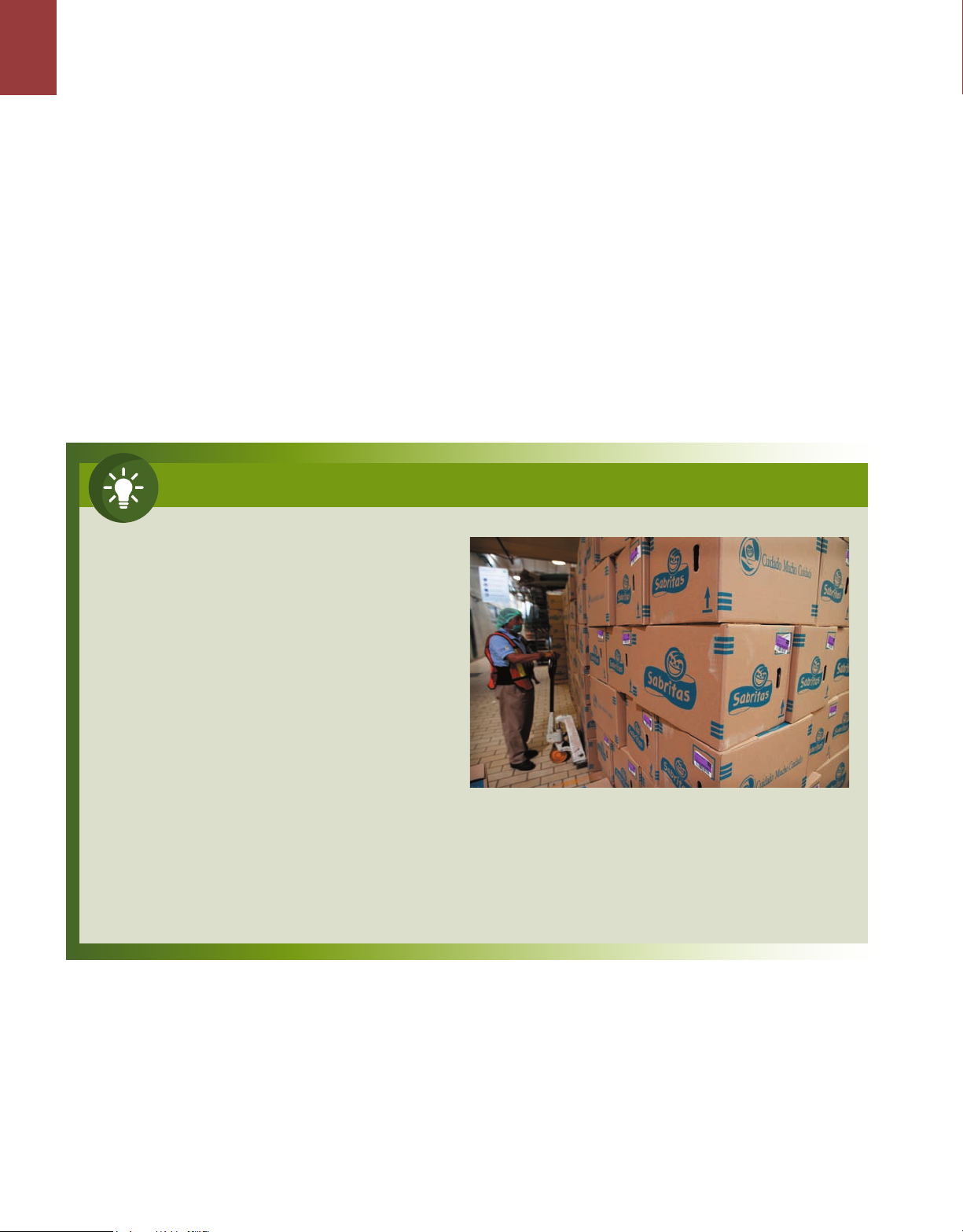

Creating a Greener World

Business Decision, Social Benefits PepsiCo

executives discovered for themselves that sustainability

decisions can be measured in the lives of individuals.

Management’s decision to launch a pilot project cut-

ting the middleman from the supply chain for Sabritas,

its Mexican line of snacks, by initiating direct purchase

of corn from 300 small farmers in Mexico brought unimagined benefits.

The decision resulted in visible, measurable out-

comes, including lower transportation costs and a ty Images

stronger relationship with small farmers, who were

able to develop pride and a businesslike approach to g/Get

farming. The arrangement with PepsiCo gave farmers

a financial edge in securing much-needed credit for Bloomber

purchasing equipment, fertilizer, and other necessities,

which resulted in higher crop yields. New levels of financial security also reduced the once-rampant and highly danger-

ous treks back and forth across the U.S. border that farmers made at great personal risk to support their families. Within

three years, PepsiCo’s pilot program was expanded to 850 farmers.

Sources: Stephanie Strom, “For Pepsi, a Business Decision with Social Benefit,” The New York Times (February 21, 2011), www.nytimes.com/

2011/02/22/business/global/22pepsi.html (accessed May 1, 2020); and Dean Best, “PepsiCo outlines Five-Year Plan for Mexico,” Just-Food

(January 24, 2014), www.just-food.com/news/pepsico-outlines-five-year-plan-for-mexico_id125662.aspx (accessed May 1, 2020).

9-1B FACING UNCERTAINTY AND AMBIGUITY

One primary difference between programmed and nonprogrammed decisions relates to the

degree of uncertainty, risk, or ambiguity that managers deal with in making the decision. In

a perfect world, managers would have all the information necessary for making decisions.

In reality, some things are unknowable; thus, some decisions will fail to solve the problem or

attain the desired outcome. Managers try to obtain information about decision alternatives

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

CHAPTER 9 MANAGERIAL DECISIoN MAKING 289

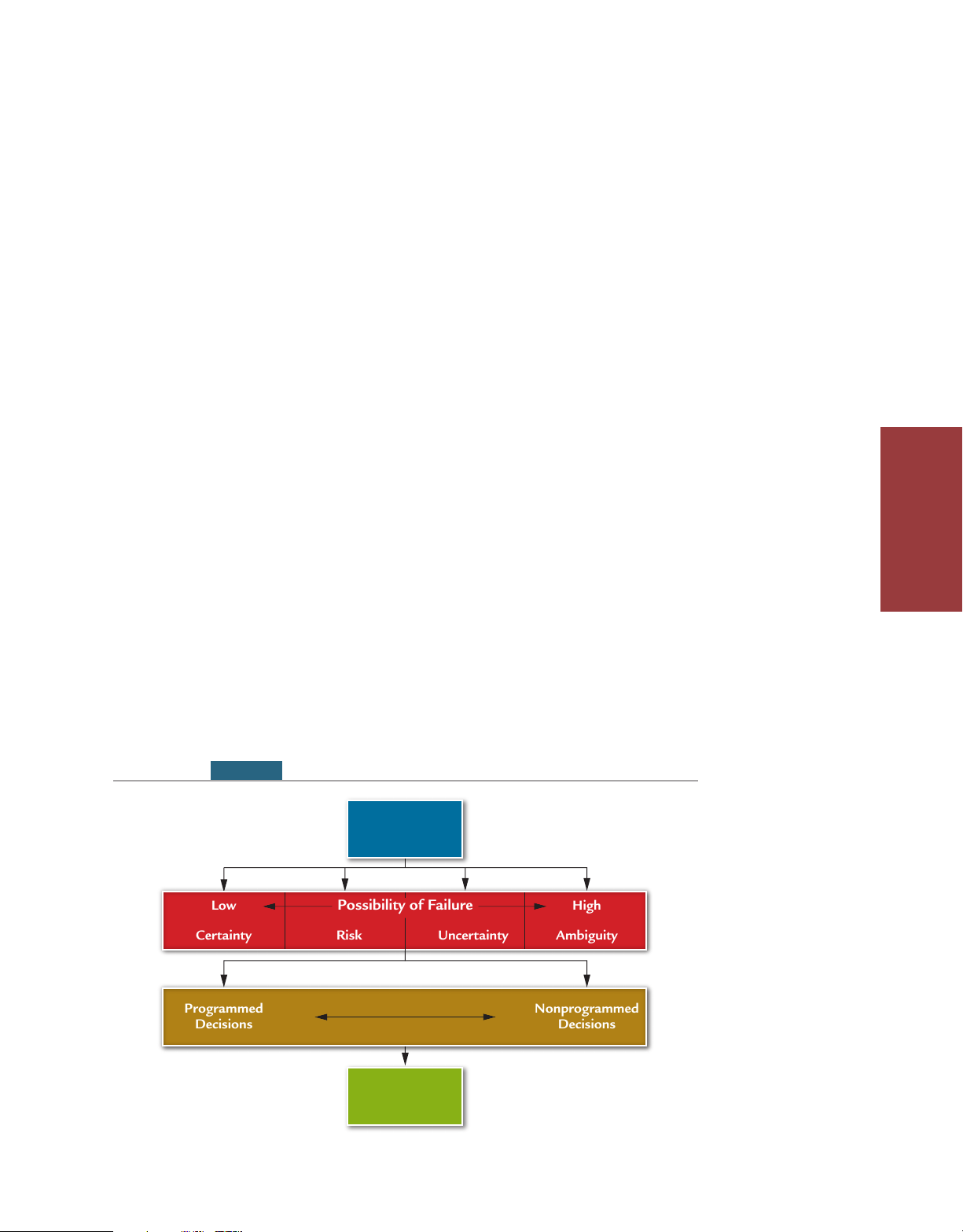

that will reduce decision uncertainty. Every decision situation can be organized on a scale

according to the availability of information and the possibility of failure. The four positions

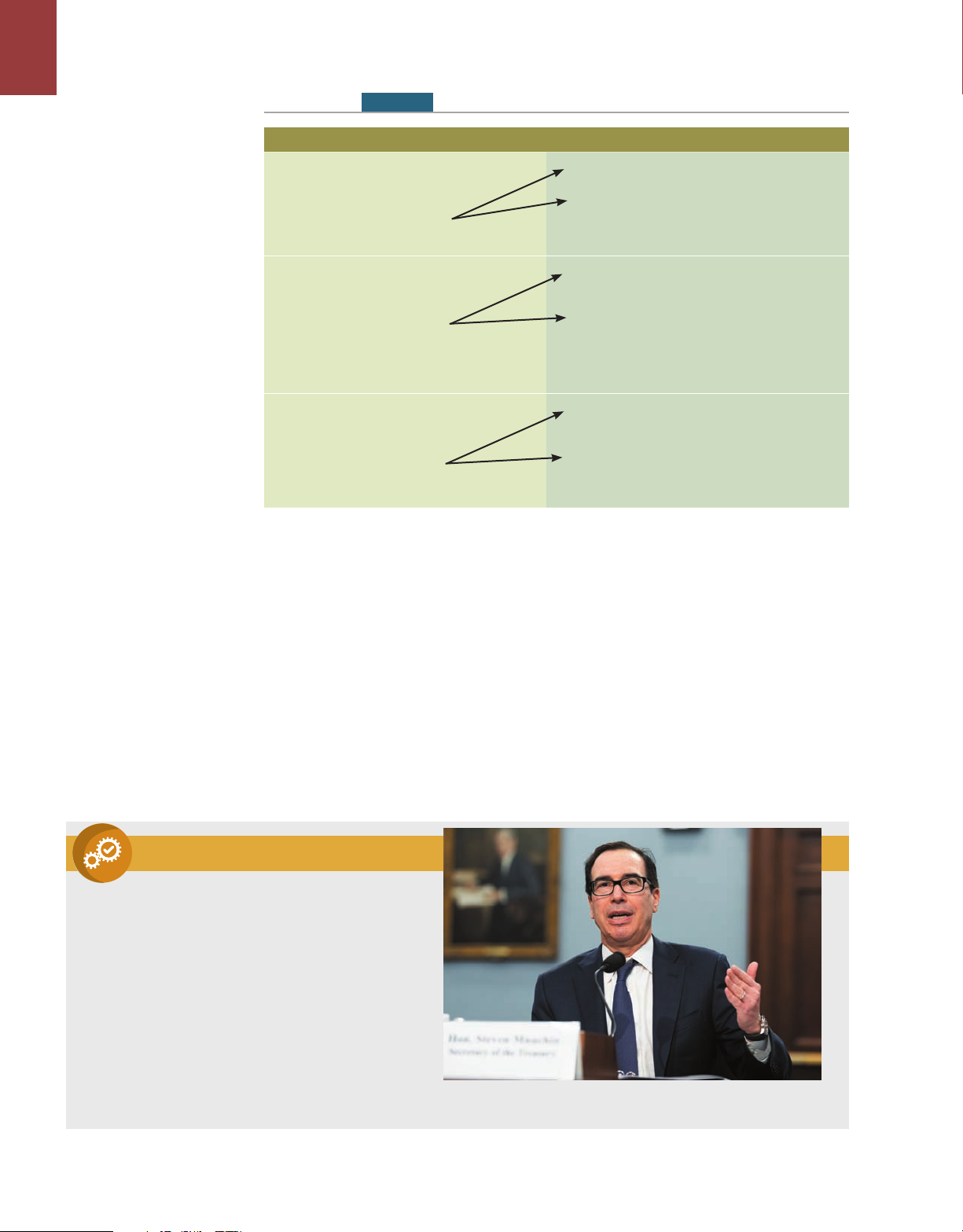

on the scale are certainty, risk, uncertainty, and ambiguity, as illustrated in Exhibit 9.1.

Whereas programmed decisions can be made in situations involving certainty, many situ-

ations that managers deal with every day involve at least some degree of uncertainty and

require nonprogrammed decision making. Certainty

Certainty means that all the information the decision maker needs is fully available.10 When

certainty is present, managers have information on operating conditions, resource costs,

and constraints and each course of action and possible outcome. For example, if a company

considers a $10,000 investment in new equipment that it knows for certain will yield $4,000

in cost savings per year over the next five years, managers can calculate a before-tax rate of

return of about 40 percent. If managers compare this investment with one that will yield

only $3,000 per year in cost savings, they can confidently select the 40 percent return. Of

course, few decisions are certain in the real world; instead, most contain risk or uncertainty. Risk 3

Risk means that a decision has clear-cut goals and that good information is available, but the

future outcomes associated with each alternative are subject to some chance of loss or failure.

However, when enough information is available, managers can estimate the probability of

a successful outcome versus failure.11 For example, when managers at McDonald’s, Burger

King, or KFC face a decision about opening a new restaurant in the United States, they can PLANNING

analyze local demographics, traffic patterns, prices and availability of real estate, and competi-

tors’ locations in the area. Combining these data with restaurant revenue and cost models,

managers can calculate the risk and make a reasonably good choice for a new location.12

Steve Krupp, a senior managing partner at Decision Strategies International, a consult-

ing firm that helps managers and employees feel more comfortable taking balanced risks,

says, “You can’t just avoid all risk, because it will lead to entropy.”13 For specific decisions,

managers sometimes use computerized statistical analysis to calculate the probabilities of

success or failure for each alternative.14

E X H I B I T 9.1 Conditions That Affect the Possibility of Decision Failure Organizational Problem Low Possibility of Failure High Certainty Risk Uncertainty Ambiguity Programmed Nonprogrammed Decisions Decisions Problem Solution

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 290 PART 3 PLANNING Uncertainty

Uncertainty means that managers know which goals they wish to achieve, but informa-

tion about alternatives and future events is incomplete. Factors that may affect a decision,

such as price, production costs, volume, or future interest rates, are difficult to analyze

and predict. Managers may have to make assumptions from which to forge the decision,

even though it will be wrong if the assumptions are incorrect. As an example, managers SNAPSHOT

at Airstream decided in late 2018 to build a new recreational vehicle factory despite

uncertainty regarding the possibility of increased tariffs and slowing sales. Bob Martin,

CEO of Airstream’s parent company Thor Industries, said the executive’s job is to engage

in longer-term thinking in a business that is always facing uncertainty.15

Former U.S. treasury secretary Robert Rubin defined uncertainty as a situation in which

even a good decision might produce a bad outcome.16 Consider the decisions of U.S. gover-

nors concerning rescinding stay-at-home orders and reopening businesses in their states

during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. These leaders faced a tremendous amount

of uncertainty, and no matter how much analysis and thought went into the decision to

reopen or not to reopen, the bad outcome of a COVID-19 rebound was still possible.

Managers face uncertainty every day. Many problems have no clear-cut solution, but manag-

ers rely on creativity, judgment, intuition, and experience to craft a response.

The movie industry provides an illustration. Disney’s Oz the Great and Powerful cost

about $325 million to make and market, but the gamble in putting out a prequel to the SNAPSHOT

beloved 1939 musical The Wizard of Oz paid off, bringing in $150 million in revenues

on its opening weekend and eventually grossing $495 million. Even though Disney man-

agers did a cost–benefit analysis, they faced great uncertainty regarding how viewers

would feel about a new twist on such well-known material.17 Many films made today

don’t even break even, which reflects the tremendous uncertainty in the industry. What do

people want to see this summer? Will comic book heroes, vampires, or aliens be popular?

Will animated films, disaster epics, classics, or romantic comedies attract larger audiences?

The interests and preferences of moviegoers are extremely difficult to predict. Moreover, it

is hard for managers to understand even after the fact what made a particular movie a hit:

Was it because of the storyline, the actors in starring roles, the director, the release date? All

of those things? Or none of them? Despite the uncertainty, managers in the big Hollywood

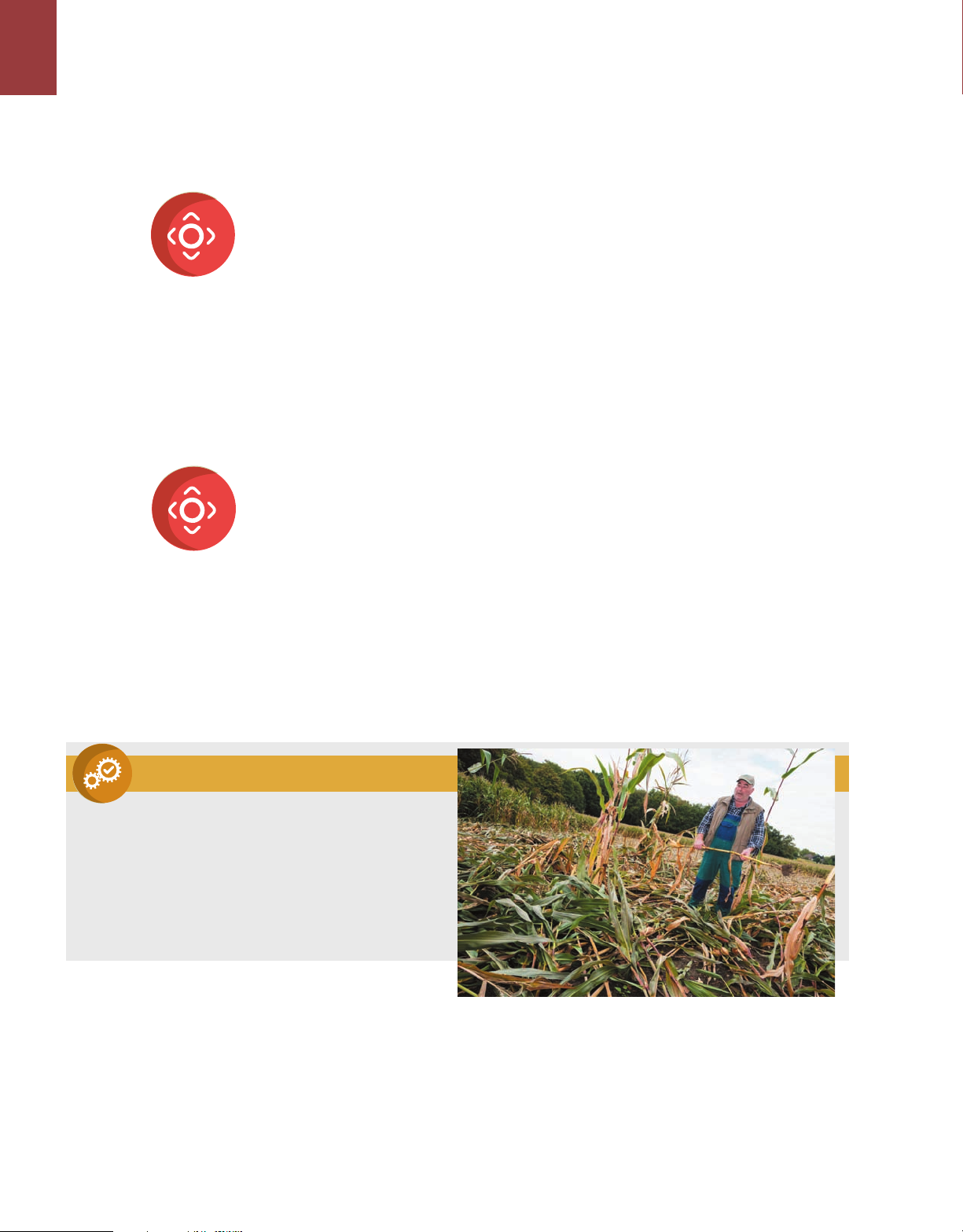

studios make relatively good decisions overall, and one big hit can pay for a lot of flops.18 Concept Connection

Uncertainty is a standard feature in the life of

any farmer. Changing weather patterns and unexpected o

events, like droughts, floods, or unseasonable storms,

can have devastating effects on crops that no amount of k Phot oc

planning can prevent. Yet, despite these unforeseeable y St

situations, farmers must make decisions and continue to ial/Alam

operate based on assumptions and expectations. . Tor E.D Ambiguity and Conflict

Ambiguity is by far the most difficult decision situation. Ambiguity means that the

goals to be achieved or the problem to be solved is unclear, alternatives are difficult to

define, and information about outcomes is unavailable.19 Ambiguity is what students

would feel if an instructor created student groups and told each group to complete

a project but gave the groups no topic, direction, or guidelines whatsoever. In some

situations, managers involved in a decision create ambiguity because they see things

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

CHAPTER 9 MANAGERIAL DECISIoN MAKING 291

differently and disagree about what they want. Managers in different departments

often have different priorities and goals for the decision, which can lead to conflicts “One thing a person over decision alternatives.

Managers in almost any organization will occasionally encounter ambiguity. cannot do, no matter

As part of their role, managers have to both address current customer needs and how rigorous his

environmental conditions and take risks to pursue innovative products, services,

and technologies that will please customers in the future. In global firms, managers analysis or heroic

must consider whether a global approach or a local approach is more appropriate

for their organization, as described in Chapter 8. In some companies, managers face his imagination, is

conflicts between social or environmental missions and financial pressures.20 All of to draw up a list of

these dilemmas, and more, create ambiguity for managers facing difficult decisions.

A highly ambiguous situation can create what is sometimes called a wicked deci- things that would

sion problem. In such a case, simply defining the problem can turn into a major task. never occur to him.”

A recent situation at Twitter concerning how to make the social media service safer

for users provides an illustration. Twitter has clear rules forbidding direct threats —Thomas schelling, ECONOMIST AND NOBEL LAUREATE

of violence and some forms of hate speech, but there are no rules prohibiting

deception or misinformation. As CEO Jack Dorsey and a team of colleagues

gathered to discuss how to get rid of “dehumanizing speech” even if it doesn’t

violate Twitter’s rules, one team member said during his comments, “Please bear with 3

me. This is incredibly complex.” The policy meeting went on for more than an hour, with SNAPSHOT

participants struggling to simply come up with a definition of what constitutes “dehu-

manizing speech.” Karen Kornbluh, a senior fellow of digital policy at the Council of

Foreign Relations, captured Twitter’s wicked decision problem when she said, “There is

no due process, no transparency, no case law, and no expertise on these very complicated PLANNING

legal and social questions behind these decisions.”21

Twitter’s struggle over what to ban from its site illustrates a wicked problem. Wicked

decisions are associated with conflicts over goals and decision alternatives, rapidly changing

circumstances, fuzzy information, unclear links among decision elements, and the inability

to evaluate whether a proposed solution will work. For wicked problems, there often is no

“right” answer.22 Managers have a difficult time coming to grips with the issues and must

conjure up reasonable scenarios in the absence of clear information. Remember This

• Good decision making is a vital part of good

• Certainty is a situation in which all the information the

management, but decision making is not easy.

decision maker needs is fully available.

• Decision making is the process of identifying problems

• Risk means that a decision has clear-cut goals and

and opportunities and then resolving them.

good information is available, but the future outcomes

• A decision is a choice made from available

associated with each alternative are subject to chance. alternatives.

• Uncertainty occurs when managers know which goals

• A programmed decision is one made in response to

they want to achieve, but information about alternatives

a situation that has occurred often enough to enable

and future events is incomplete.

managers to develop decision rules that can be applied

• U.S. governors faced tremendous uncertainty in in the future.

decisions concerning stay-at-home orders and business

• A nonprogrammed decision is one made in response

shut-downs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

to a situation that is unique, is poorly defined and

• Ambiguity is a condition in which the goals to be

largely unstructured, and has important consequences

achieved or the problem to be solved is unclear, for the organization.

alternatives are difficult to define, and information

• An example of a nonprogrammed decision was the about outcomes is unavailable.

decision to build the Airbus A380.

• Highly ambiguous circumstances can create a wicked

• Decisions differ according to the amount of certainty,

decision problem, the most difficult decision situation

risk, uncertainty, or ambiguity in the situation. that managers face.

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 292 PART 3 PLANNING 9-2 Decision-Making Models

The approach that managers use to make decisions usually follows one of three models:

the classical model, the administrative model, or the political model. The choice of model

depends on the manager’s personal preference, whether the decision is programmed or

nonprogrammed, and the degree of uncertainty associated with the decision.

9-2A THE IDEAL, RATIONAL MODEL

The classical model of decision making is based on rational economic assumptions and

managers’ beliefs about what ideal decision making should be. The management literature

often advocates use of this model because managers are expected to make decisions that are

economically sensible and in the organization’s best economic interests. Four assumptions underlie this model:

• The decision maker operates to accomplish goals that are known and agreed on. Prob-

lems are precisely formulated and defined.

• The decision maker strives for conditions of certainty and tries to gather complete

information. All alternatives and the potential results of each are calculated.

• Criteria for evaluating alternatives are known. The decision maker selects the alternative

that will maximize the economic return to the organization.

• The decision maker is rational and uses logic to assign values, order preferences, evaluate

alternatives, and make the decision that will maximize the attainment of organizational goals.

The classical model of decision making is considered to be normative, which means

that it defines how a decision maker should make decisions. For the most part, managers

want to be as rational as possible and push toward rational decision making. This model

does not describe how managers actually make decisions so much as it provides guidelines

on how to strive for an ideal outcome for the organization. Charles Darwin even tried to

use a rational process to decide whether he should get married. Under “not marry,” he SNAPSHOT

noted benefits of bachelorhood such as enjoying “conversation of clever men at clubs.”

Under “marry,” he included “children (if it please God)” and “charms of music and female

chitchat.”23 Perhaps Darwin felt that by using this rational approach he was “less liable

to make a rash step,” as Benjamin Franklin once commented.24 For managers, too, the

rational approach was developed to guide individual decision making because some man-

agers were observed to be unsystematic and arbitrary in their approach to organizational decisions.

The ideal, rational approach of the classical model is often unattainable by real people

in real organizations, but the model still has value because it helps decision makers be

more rational and not rely entirely on personal preferences or impulses in making deci-

sions. Consider that Amazon’s Jeff Bezos—who once said that all of his “best decisions SNAPSHOT

in business and in life have been made with heart, intuition, guts, not analysis”—is also

a strong proponent of using data and rationality in making decisions.25 Whenever any-

one requests a meeting, Bezos requires that individual to prepare a six-page memo that

includes data, pros and cons of various ideas, and so forth, to force that person to incor-

porate rationality in the process. Indeed, a global survey by McKinsey & Company found

that when managers incorporate thoughtful analysis into their decision making, they get better results.26

The classical model is useful when applied to programmed decisions and to decisions

characterized by certainty or low levels of risk because relevant information is available and

probabilities can be calculated. The growth of AI and big data techniques, as described in

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

CHAPTER 9 MANAGERIAL DECISIoN MAKING 293

Chapter 2, has expanded the use of the classical approach. AI can automate many pro-

grammed decisions, such as freezing the accounts of customers who fail to make payments

or sorting insurance claims so that cases are handled most efficiently. The New York City SNAPSHOT

Police Department uses computerized mapping and analysis of arrest patterns, paydays,

sporting events, concerts, rainfall, holidays, and other variables to predict likely crime

“hot spots” and decide where to assign officers. UPS uses a sophisticated digital platform

to optimize its 66,000 delivery routes for drivers across North America and Europe.

The On Road Integrated Optimization and Navigation (ORION) system uses advanced

algorithms, AI, and machine learning to find the right balance between cost efficiency

for the company and consistency for the customer.27

Advances in digital technology have also revolutionized decision making in the world

of sports. Most of today’s major league sports team managers use data analytics more than SNAPSHOT

intuition to make critical decisions. In the 2011 movie Moneyball, Brad Pitt portrays

Billy Beane, the legendary general manager for the Oakland Athletics baseball team,

who in 2002 built one of Major League Baseball’s

winningest teams with one of its smallest budgets.

Rather than rely on the intuition of scouts, who

would sometimes reject a player because he “didn’t

look like a major leaguer,” Beane relied heavily on 3 ty Images

data and statistical analysis. Over the past decade,

most other major league sports teams have adopted

big data statistical techniques for making decisions. Association/Get

The average number of 3-point attempts in National etball

Basketball Association (NBA) games increased every PLANNING

year between 2009 and 2019 based on statistical

analysis that showed that 3-point shots are worth

50 percent more than 2-point shots. The National encich/National Bask or

Football League (NFL) has gone through a similar am F

flood of data gathering and analysis.28 S

9-2B HOW MANAGERS MAKE DECISIONS

Another approach to decision making, called the administrative model, is considered to

be descriptive, meaning that it describes how managers actually make decisions in complex

situations rather than dictating how they should make decisions according to a theoretical

ideal. The administrative model recognizes the human and environmental limitations that

affect the degree to which managers can pursue a rational decision-making process. In dif-

ficult situations, such as those characterized by nonprogrammed decisions, uncertainty,

and ambiguity, managers are typically unable to make economically rational decisions even if they want to.29

Bounded Rationality and Satisficing

The administrative model of decision making is based on the work of Herbert A. Simon.

Simon proposed two concepts that were instrumental in shaping the administrative model:

bounded rationality and satisficing. Bounded rationality means that people have limits, or

boundaries, on how rational they can be. Organizations are incredibly complex, and manag-

ers have the time and ability to process only a limited amount of information with which

to make decisions.30 Because managers do not have the time or cognitive ability to process

complete information about complex decisions, they must satisfice. Satisficing means that

decision makers choose the first solution alternative that satisfies minimal decision criteria.

Rather than pursuing all alternatives to identify the single solution that will maximize eco-

nomic returns, managers opt for the first solution that appears to solve the problem, even

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 294 PART 3 PLANNING

if better solutions are presumed to exist. The decision maker cannot justify the time and

expense of obtaining complete information.31

Managers sometimes continue to generate alternatives for complex problems only until

they find one that they believe will work. For example, Liz Claiborne managers hired SNAPSHOT

designer Isaac Mizrahi and targeted younger consumers in an effort to revive the flagging

brand, but sales and profits continued to decline. Faced with the failure of the new youth-

oriented line, a 90 percent cutback in orders from a large retailer, high unemployment,

a weak economy, and other complex and multifaceted problems, managers weren’t sure

how to stem the years-long tide of losses and get the company back in the black. They

satisficed with a quick decision to form a licensing agreement to have the Liz Claiborne

brand sold exclusively at JC Penney, which handles all manufacturing and marketing.32

The administrative model relies on assumptions that differ from those of the classical

model and focuses on organizational factors that influence individual decisions. According to the administrative model:

• Decision goals often are vague, conflict with one another, and lack consensus among managers.

• Managers often are unaware of problems or opportunities that exist in the organization.

• Rational procedures are not always used, and, when they are, they are confined to a

simplistic view of the problem that does not capture the complexity of real organiza- tional events.

• Managers’ searches for alternatives are limited because of human, information, and resource constraints.

• Most managers settle for a satisficing decision rather than a maximizing solution, partly

because they have limited information and partly because they have only vague criteria

for what constitutes a maximizing solution.

Intuition and Quasirationality

Another aspect of administrative decision making is intuition. Intuition represents a quick

apprehension of a decision situation based on past experience but without deliberate ratio-

nal thought or analysis.33 Intuitive decision making is not arbitrary or irrational because it

is based on years of practice and hands-on experience. One article on intuition cites the SNAPSHOT

classic example of Formula One race car driver Juan Manuel Fangio. Fangio was leading

in the Monaco Grand Prix as he came out of the tunnel on the second lap, yet instead of

maintaining speed for an upcoming straight stretch, he inexplicably braked. It turned out

to be a wise decision, as it allowed him to avoid crashing into a serious accident that had

occurred around the next corner. Fangio said he just had a disturbing feeling as he came

out of the tunnel. Reflecting back on the incident, he reasoned that his intuitive feeling

was caused by a slight signal that he picked up unconsciously based on his racing experi-

ence: a change of color in the spectator stand. Spectators usually face toward the drivers as

they come out of the tunnel, but this time they were facing farther up the track. Although

Fangio was focusing on the road, his peripheral vision was able to notice a shift in the

light pattern from the stands that alerted his subconscious to a potential problem ahead.34

Psychologists and neuroscientists have studied how people make good decisions using

their intuition under extreme time pressure and uncertainty.35 Good intuitive decision mak-

ing is based on an ability to recognize patterns at lightning speed, as in the case of Juan

Manuel Fangio’s insight while racing at the Monaco Grand Prix. When people have a depth

of experience and knowledge in a particular area, the right decision often comes quickly

and effortlessly owing to recognition of information that has been largely forgotten by the

conscious mind. Managers continuously perceive and process information that they may

not consciously be aware of, and their base of knowledge and experience helps them make

decisions that may be characterized by uncertainty and ambiguity.

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

CHAPTER 9 MANAGERIAL DECISIoN MAKING 295

Rational decisions are the ideal, and today’s managers are frequently inundated with

data, but recent research shows that many high-level executives don’t always trust their

organization’s data and may discount data that conflicts with their gut instincts based

on experience with the business. In a recent global survey, two-thirds of CEOs sur-

veyed said they had ignored insights provided by data analysis or computer models

because it contradicted their intuition. The same survey indicated that just 35 percent

of top executives highly trust their organization’s data. Similarly, even as data have been

increasingly applied in the world of sports, Bill Belichick, head coach of the six-time

Super Bowl–winning New England Patriots, says he always prefers to “evaluate what I see” over analytics.36

Studies have found that effective managers typically use a combination of rational

analysis and intuition in making complex decisions under time pressure.37 A new trend

in decision making is referred to as quasirationality, which basically means combining

intuitive and analytical thought.38 In many situations, neither analysis nor intuition is suf-

ficient for making a good decision. However, managers may often walk a fine line between

two extremes: on the one hand, making arbitrary decisions without careful study, and on

the other hand, relying obsessively on rational analysis. One strategy is not better than the

other, and managers need to take a balanced approach by considering both rationality and

intuition as important components of effective decision making. 3 39 9-2C THE POLITICAL MODEL

The third model of decision making is useful for making nonprogrammed decisions when

conditions are uncertain, information is limited, and managers disagree about what goals to PLANNING

pursue or what course of action to take. Most organizational decisions involve many manag-

ers who are pursuing different goals, and they must talk with one another to share informa-

tion and reach an agreement. When making complex organizational decisions, managers

often engage in coalition building.40 A coalition is an informal alliance among managers

who support a specific goal. Coalition building is the process of forming alliances among

managers. In other words, a manager who supports a specific alternative, such as increasing

the corporation’s growth by acquiring another company, talks informally to other executives

and tries to persuade them to support the decision. In situations where no coalition exists, a

powerful individual or group could derail the decision-making process. Coalition building,

however, gives several managers an opportunity to contribute to decision making, enhancing

their commitment to the alternative that is ultimately adopted.

The Los Angeles Rams football franchise used a political model to hire a new coach.

Club owner Stan Kroenke and other Rams leaders, including chief operating officer SNAPSHOT

Kevin Demoff and general manager Les Snead, first came up with a list of about 30

desirable candidates, then involved people throughout the franchise in evaluating them.

One name on the list was 30-year-old Sean McVay.

Some leaders were apprehensive about the possibility

of hiring a head coach who was 38 years younger than

the team’s defensive coordinator. To make sure every-

one would support the final decision, the interviewing

process with McVay took place over a period of eight ty Images

days and involved McVay meeting with players, staff t/Get

members, and managers throughout the organization.

The decision to hire McVay turned out to be a good

one: Two years later, McVay took the Rams to the ty Images Spor

Super Bowl, where he was the youngest head coach

ever to reach the Super Bowl game and was eight years

younger than the quarterback of the opposing team, Tom Brady.41 Jonathan Bachman/Get

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 296 PART 3 PLANNING

Another example of use of the political model comes from the Hallmark Channel.

Recall from Chapter 3 that the airing of a commercial featuring a same-sex marriage cer-

emony led to a flood of angry complaints from conservative viewers; then, when Hallmark

pulled the ad, managers got a flood of complaints from gay-rights advocacy groups. Top

executives spent a weekend talking with one another and building a coalition that decided

to reverse the previous decision.42

The political model closely resembles the real environment in which most managers

and decision makers operate. Interviews with CEOs in high-tech industries indicate that

they strive to use some type of rational decision-making process, but the way they actually

decide things relies on complex interactions with other managers, subordinates, environ-

mental factors, and organizational events.43 Decisions are complex and involve many people,

information is often ambiguous, and disagreement and conflict over problems and solutions

are the norm. The political model begins with four basic assumptions:

• Organizations are made up of groups with diverse interests, goals, and values. Manag-

ers disagree about problem priorities and may not understand or share the goals and interests of other managers.

• Information is ambiguous and incomplete. The attempt to be rational is limited by the

complexity of many problems, as well as personal and organizational constraints.

• Managers do not have the time, resources, or mental capacity to identify all dimensions

of the problem and process all relevant information. Managers talk to each other and

exchange viewpoints to gather information and reduce ambiguity.

• Managers engage in the push and pull of debate to decide goals and discuss alternatives.

Decisions are the result of bargaining and discussion among coalition members.

The key dimensions of the classical, administrative, and political models are listed in

Exhibit 9.2. Research into decision-making procedures has found rational, classical pro-

cedures to be associated with high performance for organizations in stable environments.

However, administrative and political decision-making procedures and intuition have been

associated with high performance in unstable environments in which decisions must be

made rapidly and under more difficult conditions.44

E X H I B I T 9.2 Characteristics of Classical, Administrative, and Political Decision-Making Models Classical Model Administrative Model Political Model Clear-cut problem and goals Vague problem and goals Pluralistic; conflicting goals Condition of certainty Condition of uncertainty

Condition of uncertainty or ambiguity

Full information about alternatives Limited information about

Inconsistent viewpoints; ambiguous and their outcomes

alternatives and their outcomes information

Rational choice by individual for

Satisficing choice for resolving

Bargaining and discussion among maximizing outcomes problem using intuition coalition members Remember This

• The ideal, rational approach to decision making, called

• The classical model is normative, meaning that it

the classical model, is based on the assumption that

defines how a manager should make logical decisions

managers should make logical decisions that are

and provides guidelines for reaching an ideal

economically sensible and in the organization’s best outcome. economic interest.

C O N T I N U E D

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

CHAPTER 9 MANAGERIAL DECISIoN MAKING 297

• Artificial intelligence software programs based on

• Intuition is an aspect of administrative decision making

the classical model are being applied to programmed

that refers to a quick comprehension of a decision

decisions, such as how to schedule airline crews or how

situation based on past experience but without

to process insurance claims most efficiently.

deliberate rational thought or analysis.

• The administrative model includes the concepts

• A global survey found that two-thirds of CEOs said

of bounded rationality and satisficing and describes

they had ignored insights provided by data analysis or

how managers make decisions in situations that are

computer models because it contradicted their intuition.

characterized by uncertainty and ambiguity.

• A new trend in decision making, quasirationality,

• The administrative model is descriptive, meaning that it

combines intuitive and analytical thought.

describes how managers actually make decisions, rather

• The political model takes into consideration that many

than how they should make decisions according to a

decisions require debate, discussion, and coalition theoretical model. building.

• Bounded rationality means that people have the time

• The Los Angeles Rams used a political model to hire a

and cognitive ability to process only a limited amount of new head football coach.

information on which to base decisions.

• A coalition is an informal alliance among managers who

• Satisficing means choosing the first alternative that

support a specific goal or solution.

satisfies minimal decision criteria, regardless of whether 3

better solutions are presumed to exist. 9-3 Decision-Making Steps PLANNING

Whether a decision is programmed or nonprogrammed, and regardless of whether manag-

ers choose the classical, administrative, or political model of decision making, an effective

decision-making process usually involves six steps. These steps, summarized in Exhibit 9.3,

reflect the attempt to be as rational as possible when making important decisions.

9-3A RECOGNITION OF DECISION REQUIREMENT

Managers confront a decision requirement in the form of either a problem or an opportu-

nity. A problem occurs when organizational accomplishment is less than established goals;

that is, some aspect of performance is unsatisfactory. An opportunity exists when managers

see potential accomplishment that exceeds specified current goals. In such a case, managers

see the possibility of enhancing performance beyond current levels.

Awareness of a problem or opportunity is the first step in the decision-making sequence,

and it requires surveillance of the internal and external environments for issues that merit

managers’ attention.45 Some information comes from periodic financial reports, perfor-

mance reports, and other sources that are designed to discover problems before they become

too serious. Managers also take advantage of informal sources: They talk to other manag-

ers, gather opinions on how things are going, and seek advice on which problems should be

tackled or which opportunities embraced.46 For example, after spending more than a year

trying to increase sales of products by lowering the products’ prices, managers at Procter SNAPSHOT

& Gamble reviewed data showing that the strategy wasn’t working. They saw a problem

and decided to shift toward increasing prices on some of P&G’s biggest brands.47 Recog-

nizing decision requirements is sometimes difficult because it often means integrating bits

and pieces of information in novel ways.

9-3B DIAGNOSIS AND ANALYSIS OF CAUSES

Once a problem or opportunity comes to a manager’s attention, the understanding of the

situation should be refined. Diagnosis is the step in the decision-making process in which

managers analyze underlying causal factors associated with the decision situation.

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 298 PART 3 PLANNING

E X H I B I T 9.3 Six Steps in the Managerial Decision-Making Process 1. Recognition of Decision Requirement 6. Evaluation Diagnosis 2. and and Analysis Feedback of Causes Decision-Making Process Implementation Development of of Chosen Alternatives Alternative 5. 3. Selection of Desired Alternative 4.

Many times, the real problem lies hidden behind the problem that managers think exists.

By looking at a situation from different angles, managers can identify the true problem. In

addition, they often discover opportunities that they didn’t realize were there.48 Charles

Kepner and Benjamin Tregoe, who conducted extensive studies of manager decision mak-

ing, recommend that managers ask a series of questions to specify underlying causes:

• What is the state of disequilibrium affecting us? • When did it occur? • Where did it occur? • How did it occur?

• To whom did it occur?

• What is the urgency of the problem?

• What is the interconnectedness of events?

• What result came from which activity?49

Such questions help specify what actually happened and why.

Diagnosing a problem can be thought of as peeling an onion layer by layer. Managers

cannot solve problems if they do not know about them or if they are addressing the wrong

issues. Some experts recommend continually asking “Why?” to get to the root of a problem,

a technique sometimes called “the 5 Whys.” The 5 Whys question-asking method allows

managers to explore the root cause underlying a particular problem. The first why gener-

ally produces a superficial explanation for the problem, and each subsequent why probes

deeper into the causes of the problem and potential solutions. In a New York Times article,

author Charles Duhigg explained how his family used the 5 Whys technique to address the

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

CHAPTER 9 MANAGERIAL DECISIoN MAKING 299

problem of not getting to eat dinner as a family often enough. By continually asking why,

the family arrived at the root cause: It took the kids so long to get dressed in the mornings

that everyone was late getting out the door, triggering a cascade of delays throughout the

day and culminating in staggered dinner times rather than family meals. The solution—kids

pick out clothes to wear the night before—allowed family dinners again.50

9-3C DEVELOPMENT OF ALTERNATIVES

The next stage is to generate possible alternative solutions that will respond to the needs of

the situation and correct the underlying causes.

For a programmed decision, feasible alternatives are easy to identify; in fact, they usu-

ally are already available within the organization’s rules and procedures. Nonprogrammed

decisions, however, require developing new courses of action that will meet the company’s

needs. For decisions made under conditions of high uncertainty, managers may develop only

one or two custom solutions that will satisfice for handling the problem. However, limiting

the search for alternatives is a primary cause of decision failure in organizations.51 Scholar

and researcher Paul Nutt has studied decisions extensively. One important insight that

emerged from his research is the importance of generating multiple alternatives to attain 3

a successful decision outcome. In one study, Nutt found that people who considered only

one alternative ultimately judged their decision a failure more than 50 percent of the time,

whereas decisions that involved consideration of at least two alternatives were judged to be

successful two-thirds of the time.52 Even if it seems that only one alternative is available, it

pays to find at least one more.

Decision alternatives can be thought of as tools for reducing the difference between the PLANNING

organization’s current and desired performance. Smart managers tap into the knowledge

of people throughout the organization, and sometimes even outside the organization, to

find more decision alternatives. As an example, several years ago, before Canadian min-

ing group Goldcorp merged with Newmont, managers faced a problem regarding the SNAPSHOT

company’s Red Lake site. A nearby mine was thriving, but no one could seem to pinpoint

where to find the high-grade ore at Red Lake. The company created the Goldcorp Chal-

lenge, putting Red Lake’s closely guarded topographic data online and offering $575,000

in prize money to anyone who could identify rich drill sites. More than 1,400 techni-

cal experts in 50 countries offered alternatives to the problem, and two teams working

together in Australia pinpointed locations that turned Red Lake into one of the world’s richest gold mines.53

9-3D SELECTION OF THE DESIRED ALTERNATIVE

Once feasible alternatives are developed, one must be selected. In this stage, managers try

to select the most promising of several alternative courses of action. The best alternative

is the one that best fits the overall goals and values of the organization and achieves the

desired results using the fewest resources.54 Managers want to select the choice with the

least amount of risk and uncertainty. Because some risk is inherent in most nonprogrammed

decisions, managers try to gauge the alternatives’ prospects for success. They might rely on

their intuition and experience to estimate whether a given course of action is likely to suc-

ceed. Basing choices on overall goals and values can also guide the selection of alternatives.

Choosing among alternatives also depends on managers’ personality factors and willing-

ness to accept risk and uncertainty. Risk propensity is the willingness to undertake risk in

exchange for the opportunity of gaining an increased payoff. For example, Facebook would SNAPSHOT

never have reached more than two billion users without Mark Zuckerberg’s “move fast,

break things” mind-set. Motivational posters with that slogan are papered all around the

company to prevent delay from too much analysis of alternatives. Zuckerberg says, “If

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 300 PART 3 PLANNING

E X H I B I T 9.4 Decision Alternatives with Different Levels of Risk

In each of the following situations, which alternative would you choose? You’re the coach of a

1. Choose a play that has a 95 percent college football team,

chance of producing a tie score; oR and in the final seconds

2. Go for a play that has a 30 percent of a game with the

chance of victory but will lead to team’s archrival, you certain defeat if it fails. face a choice: As president of a

1. Build a plant in Canada that has a Canadian manufacturing

90 percent chance of producing a company, you face a

modest return on investment; oR decision about building a

2. Build a plant in a foreign country that new factory. You can:

has an unstable political history. This

alternative has a 40 percent chance

of failing, but the returns will be enormous if it succeeds. It’s your senior year, and

1. Go to medical school and become a it’s time to decide your

physician, a career in which you are next move. Here are

80 percent likely to succeed; oR the alternatives you’re

2. Follow your dreams and be an actor, considering:

even though the opportunity for

success is only around 20 percent.

you’re successful, most of the things you’ve done were wrong. What ends up mattering

is the stuff you get right.” Facebook runs a never-ending series of on-the-fly experiments

with real users. Even employees who haven’t finished their six-week training program

are encouraged to work on the live site. That risky approach means that the whole site

crashes occasionally, but Zuckerberg says, “The faster we learn, the better we’re going to

get to the model of where we should be.”55

The level of risk a manager is willing to accept will influence the analysis of the costs

and benefits to be derived from any decision. Consider the situations in Exhibit 9.4. In each

situation, which alternative would you choose? A person with a low risk propensity would

tend to take assured moderate returns by going for a tie score, building a domestic plant,

or pursuing a career as a physician. A risk taker would go for the victory, build a plant in a

foreign country, or embark on an acting career. Concept Connection

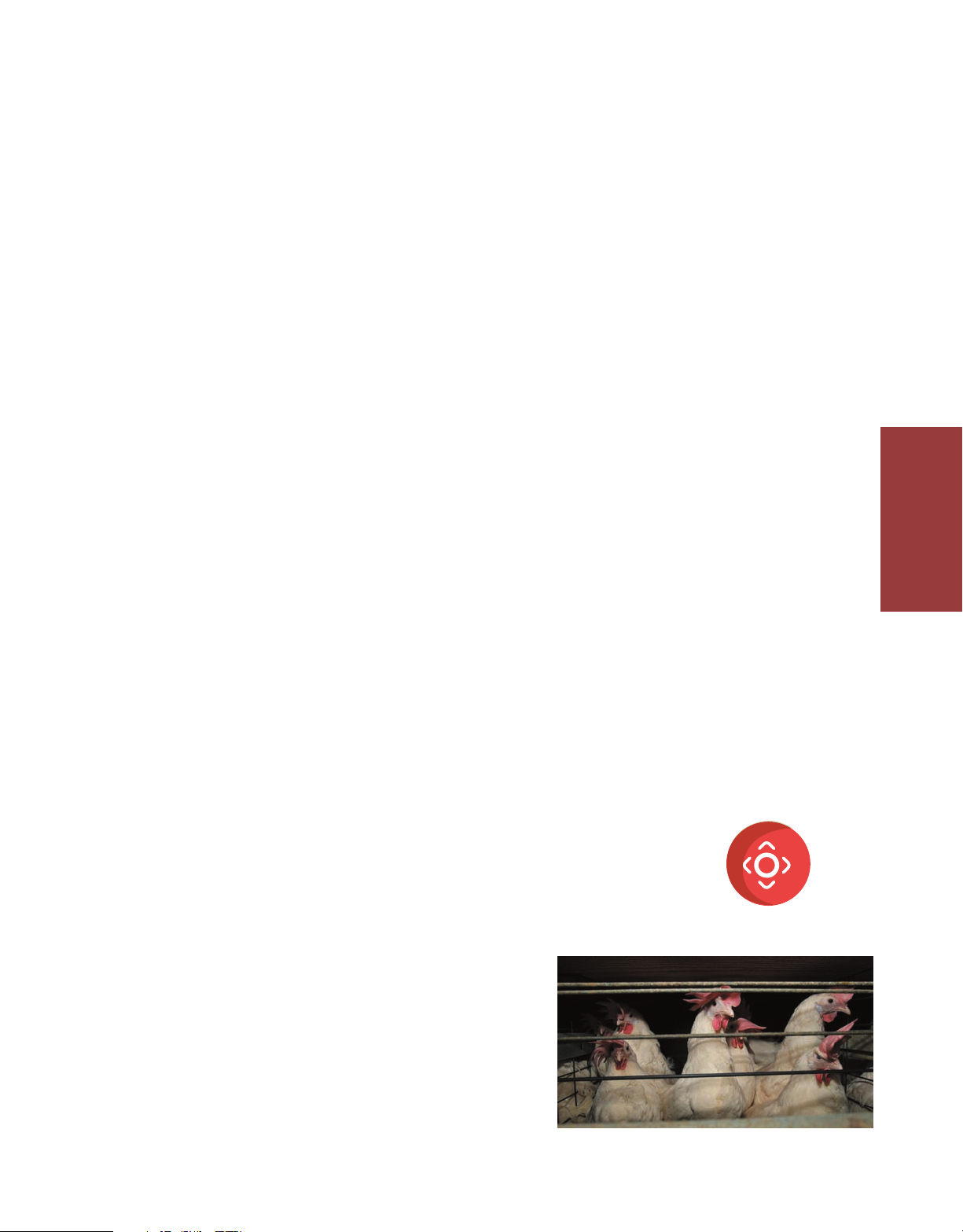

The decision to offer federally guaranteed loans

to keep small businesses afloat during the COVID-19 o

pandemic in the United States was easy to make,

but implementation of the chosen alternative k Phot oc

was a nightmare. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin y St

announced that loans would flow to small businesses

in days. The rollout, however, was chaotic, with Small ed/Alam

Business Administration (SBA) program glitches and

bank bureaucracies delaying some loans for weeks.

Moreover, much of the money went to larger public A Images Limit companies by mistake. SOP

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

CHAPTER 9 MANAGERIAL DECISIoN MAKING 301

9-3E IMPLEMENTATION OF THE CHOSEN ALTERNATIVE

The implementation stage involves the use of managerial, administrative, and persuasive

abilities to ensure that the chosen alternative is carried out. This step is similar to the

idea of strategy execution described in Chapter 8. The ultimate success of the chosen

alternative depends on whether it can be translated into action. Sometimes an alterna-

tive never becomes reality because managers lack the resources or energy needed to make

things happen, or they have failed to involve people and achieve buy-in for the decision.

Successful implementation may require discussion, trust building, and active engagement

with people affected by the decision. Communication, motivation, and leadership skills

must be used to see that the decision is carried out.56 When employees see that managers

follow up on their decisions by tracking implementation success, they are more commit- ted to positive action.

9-3F EVALUATION AND FEEDBACK

In the evaluation stage of the decision process, decision makers gather information that 3

tells them how well the decision was implemented and whether it was effective in achiev-

ing its goals. The “move fast, break things” approach thrives at Facebook because of rapid

feedback. Researchers have found that immediate and explicit feedback helps people sig-

nificantly improve in activities as diverse as shooting basketball free throws, playing musi-

cal instruments, solving puzzles, and performing surgery.57 Feedback also helps managers PLANNING

make better decisions. Decision making is an ongoing process that is not completed once

and for all when a manager or board of directors votes yes or no. Instead, feedback provides

decision makers with information that can precipitate a new decision cycle. The decision

may fail, thus generating a new analysis of the problem, evaluation of alternatives, and

selection of a new alternative. Many big problems are solved by trying several alternatives

in sequence, each providing modest improvement. Feedback is the part of monitoring that

assesses whether a new decision needs to be made.

To illustrate the overall decision-making process, including evaluation and feedback,

consider the decision at Rose Acre Farms, one of the largest egg producers in the United

States, about whether to shift to cage-free facilities. Companies such as Starbucks, Nestlé

SA, Burger King, and McDonald’s are phasing out the use of eggs that come from caged

hens. Cage-free eggs also command a higher price tag, and the market for cage-free eggs is growing.

Like other egg farmers, Marcus Rust, CEO of Rose Acre Farms, had to decide how

to address the problem of meeting many different state rules and regulations aimed at SNAPSHOT

improving the well-being of egg-laying hens as well as address the growing criticism from

animal rights activists. The two primary alternatives for egg farmers are to build roomier

cages or to invest in cage-free facilities. Building cage-free facilities is much more expen-

sive, but Rust and his managers decided to bet that in the future egg farming will succeed

based on a cage-free strategy. They selected the more expensive

choice—that every facility Rose Acre builds or refurbishes will

lack cages. Implementation of the decision has begun, and at

the new Rose Acre facility in Frankfort, Indiana, 170,000 hens

wander around a 550-foot-long open barn, perch on metal rods, gall

or run up and down ramps. Evaluation and feedback are ongo-

ing and have already revealed a need for some design changes.58 lie Neiber

The decision to shift to cage-free facilities is a risky and

expensive one for Rose Acre Farms, but Rust believes it will

pay off. Strategic decisions always contain some risk, but AP Images/Char

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 302 PART 3 PLANNING

feedback and follow-up can help keep companies on track. When decisions don’t work

out so well, managers can learn from their mistakes—and sometimes turn problems into opportunities. Remember This

• Managers need to make a decision when they either

• Diagnosis is the step during which managers analyze

confront a problem or see an opportunity.

underlying causal factors associated with the decision

• A problem is a situation in which organizational situation.

accomplishments have failed to meet established

• The 5 Whys is a question-asking technique that can help goals.

diagnose the root cause of a specific problem.

• An opportunity is a situation in which managers see the

• Selection of an alternative depends partly on managers’

potential for organizational accomplishments to exceed

risk propensity, or their willingness to undertake risk in current goals.

exchange for the opportunity of gaining an increased payoff.

• The decision-making process typically involves six

• The implementation step involves using managerial,

steps: recognizing the need for a decision, diagnosing

administrative, and persuasive abilities to translate the

causes, developing alternatives, selecting an alternative,

chosen alternative into action.

implementing the alternative, and evaluating decision

• Managers at Rose Acre Farms made and implemented a effectiveness.

decision to shift to cage-free facilities for egg-laying hens.

9-4 Personal Decision Framework

Imagine you are a manager at Instagram, Twitter, The New York Times, an AMC movie

theater, or the local public library. How would you go about making important decisions

that might shape the future of your department or company? So far in this chapter, we

have discussed a number of factors that affect how managers make decisions. For example,

decisions may be programmed or nonprogrammed, situations are characterized by various

levels of uncertainty, and managers may use the classical, administrative, or political model

of decision making. In addition, the decision-making process follows six recognized steps.

What’s Your Personal Decision Style?59

Read each of the following items and circle the answer that best describes you. Think about how you typically act in a

work or school situation and mark the answer that first comes to mind. There are no right or wrong answers.

1. In performing my job or class work, I look for a. practical results. b. the best solution.

c. creative approaches or ideas.

d. good working conditions.

C O N T I N U E D

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

CHAPTER 9 MANAGERIAL DECISIoN MAKING 303 2. I enjoy jobs that

a. are technical and well defined.

b. have a lot of variety.

c. allow me to be independent and creative.

d. involve working closely with others.

3. The people I most enjoy working with are

a. energetic and ambitious.

b. capable and organized. c. open to new ideas.

d. agreeable and trusting.

4. When I have a problem, I usually

a. rely on what has worked in the past.

b. apply careful analysis.

c. consider a variety of creative approaches.

d. seek consensus with others. 3

5. I am especially good at

a. remembering dates and facts.

b. solving complex problems.

c. seeing many possible solutions. PLANNING

d. getting along with others.

6. When I don’t have much time, I

a. make decisions and act quickly.

b. follow established plans or priorities.

c. take my time and refuse to be pressured.

d. ask others for guidance and support.

7. In social situations, I generally a. talk to others.

b. think about what’s being discussed. c. observe.

d. listen to the conversation.

8. Other people consider me a. aggressive. b. disciplined. c. creative. d. supportive.

9. What I dislike most is

a. not being in control. b. doing boring work. c. following rules.

d. being rejected by others.

C O N T I N U E D

Copyright 2022 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.