Preview text:

SỞ GIÁO DỤC VÀ ĐÀO TẠO

KỲ THI CHỌN ĐỘI TUYỂN HSG DỰ THI QUỐC GIA QUẢNG TRỊ Khóa ngay: 16/10/2018 ĐỀ CHÍNH THỨC

MÔN THI: TIẾNG ANH (VÒNG 2)

Thời gian lam bai: 180 phút (không kể thời gian giao đề)

Họ, tên và chữ ký M ã p hách

(dành cho Chủ tịch Hội đồng chấm

thi – Thí sinh không viết vào ô này) Giám thị 1: Giám thị 2: HỌ VÀ TÊN THÍ" SÍNH:

………………………………………………………………………………………. SỌ& BÀ"Ọ DÀNH:

………………………………………………………………………………………. PHỌNG THÍ SỌ&:

……………………………………………………………………………………….

(Phần này cho Thí sinh ghi)

HƯỚNG DẪN THÍ SINH LÀM BÀI THI

(Giám thị hướng dẫn cho thí sinh 5 phút trước giờ thi)

Thí sinh làm toàn bộ bài thi trên đề thi theó ye/u ca2u cu3a từng pha2n. Thí sinh phải viết câu trả lời vào phần

trả lời được cho sẵn ở mỗi phần. Trai vời đie2u nay, pha2n bai lam cu3a thí sinh se: khó/ng đừờc cha Đe2 thi gó2m có 17 trang (ke= ca3 trang phach). Thí sinh pha3i kie=m tra só< tờ đe2 thi trừờc khi lam bai.

Thí sinh khó/ng đừờc ky te/n hóaAc dung bacu3a đe2 ra. Không được viết bằng mực đỏ, bút chì, không viết hai thứ mực trên tờ giấy làm bài. Pha2n viehó3ng, ngóai cach dung thừờc đe= gach cheó, khó/ng đừờc ta=y xóa baDng baTuyệt đối không

được sử dụng bút xóa.) Trai vời đie2u nay bai thi se: bi lóai.

Thí sinh ne/n lam nhap trừờc ró2i ghi chep ca=n tha/n vaó pha2n bai lam tre/n đe2 thi. Giam thi se: khó/ng phat giabai thay the< đe2 va gia Thí sinh khó/ng đừờc sừ3 dung ba Giam thi khó/ng gia3i thích gí the/m ve2 đe2 thi.

Đối với phần thi nghe: Giam thi chó thí sinh đóc qua pha2n thi nghe 5 phut ró2i tieđừờc chua=n bi saHn ta----------------------------- -1-

----- PHẦN ĐỀ VÀ BÀI LÀM CỦA THÍ SINH ----- Đie=m bai thi

Giam kha3ó thừ nhaGiam kha3ó thừ hai Ma: phach

(Ký, ghi rõ họ tên)

(Ký, ghi rõ họ tên) BaDng só< BaDng chừ: ................ .. ........ ...... ..................... . . .

.... . .. ... .. . .. . ...... .. . . .. ..

... ........ .. . . .. ........ .. ........

Ghi chú: Học sinh làm bài trên đề thi này. Đề thi gồm có 17 trang, kể cả trang phách.

Section I. LISTENING (5pts) 0.2/each

* There are 4 parts fór listening. Yóu will listen tó each part TWÍCÊ befóre móving ón tó the

next óne. Write your answers in the corresponding numbered boxes.

Part 1: For questions 1-5, listen to a conversation between Sondra, a student and her tutor.

Decide whether each of the following statements is True (T) or False (F).

1. The cómputer róóms are in Daltón Hóuse.

2. The Chemistry Labs are óppósite the Science Blóck.

3. Sóndra has paid her fees in cash.

4. The cash machine wórks thróughóut the day.

5. Sóndra can cóntact her tutór at 11 a.m. ón Saturday. Your answers: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Part 2: For questions 6-12, listen to a talk about the history of surfing and complete the

sentences with NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS for each gap.

The first surfers were (6) _______________________ whó used surfing as a way óf getting ashóre.

Ín ancient Hawaii, the best surfers came fróm the (7) ____________________________________.

The persón making a bóard wóuld leave fish as a (8) ____________________________________ tó the

góds óf the tree he had dug up.

The type óf surfbóard used by children was called a (9) ________________________________ bóard.

The “óló” was a surfbóard that ónly (10) ____________________________ cóuld use.

Ín the 20th century, a swimmer called Duke Kahanamóku made surfing pópular in Êurópe,

Àustralia, (11) ___________________________ and the USÀ.

Módern surfbóards vary in (12) _____________________ and ___________________, but all have three

fins and are made óf fiberglass. Your answers: 6. 10. 7. 11. 8. 12. 9.

Part 3: For questions 13-17, listen to an interview with someone who consulted a “life coach” to

improve her life. Choose the correct answer (A, B, C or D) which fits best according to what you hear.

13. Brigid says that she consulted a life coach because

À. she had read a great deal abóut them.

B. bóth her wórk and hóme life were getting wórse.

C. óther effórts tó impróve her life had failed. -2-

D. the changes she wanted tó make were ónly small ónes.

14. What did Brigid’s coach tell her about money?

À. Ít wóuld be very easy fór Brigid tó get a lót óf it.

B. Brigid’s attitude tówards it was uncharacteristic óf her.

C. Brigid placed tóó much emphasis ón it in her life.

D. Few peóple have the right attitude tówards it.

15. What does Brigid say about her reaction to her coach’s advice on money?

À. She felt silly repeating the wórds her cóach gave her.

B. She tried tó hide the fact that she fóund it ridiculóus.

C. She felt a lót better as a result óf fóllówing it.

D. She fóund it difficult tó understand at first.

16. What does Brigid say happened during the other sessions?

À. She was tóld that móst peóple’s próblems had the same cause.

B. Her pówers óf cóncentratión impróved.

C. Sóme things she was tóld tó dó próved harder than óthers.

D. She began tó wónder why her próblems had arisen in the first place.

17. What has Brigid concluded?

À. The benefits óf cóaching dó nót cómpensate fór the effórt required.

B. She was tóó unselfish befóre she had cóaching.

C. She came tó expect tóó much óf her cóach.

D. Ít is best tó limit the number óf cóaching sessións yóu have. Your answers: 13. 14. 15. 16. 17.

Part 4: For questions 18-25, listen to a talk about Neurolinguistic Programming (NLP).

Complete the information below with NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS for each gap.

What accóunts fór ónly 7% óf effect óf a talk ón audience is its (18) __________________________.

NLP was develóped by a student óf psychólógy and a (19) _______________________________.

NLP suggests that successful peóple shóuld be studied and (20) __________________________.

We can achieve rappórt with sómeóne by imitating their (21) _____________________________.

NLP stresses the impórtance óf (22) ______________________________.

Peóple benefiting fróm NLP training include managers, salespeóple and (23) ________________.

Salespeóple with NLP training impróved their (24) __________________________ by 258%.

NLP is móst widely used in (25) _______________________, óne óf the three Êurópean cóuntries mentióned. Your answers: 18. 22. 19. 23. 20. 24. 21. 25.

Section II. LEXICO- GRAMMAR (2 pts) 0.1/each

Part 1: For questions 26-40, choose the best answer (A, B, C or D) to each of the following

questions and write your answers in the corresponding numbered boxes.

26. He’s ___________________ and makes prómises withóut thinking abóut the cónsequences. À. prómpt B. impulsive C. abrupt D. quick

27. Àfter a bad patch, Helen is back tó her óld __________________ again, Í’m glad tó say. À. type B. self C. like D. ówn

28. When Sally leaves this department, she will be _____________________ missed. -3- À. sórely B. utterly C. fully D. appreciably

29. Mr Smith ate his breakfast in great ______________________ só as nót tó miss the bus tó Liverpóól. À. speed B. pace C. rush D. haste

30. The scientists bróke dówn as they realised that all their effórts had góne tó ________________ À. lóss B. failure C. waste D. cóllapse

31. Tó his ówn great ___________________, prófessór Hóward has discóvered a new methód óf bulimia treatment. À. reputatión B. name C. fame D. credit

32. Í was awfully tired. Hówever, Í made up my mind tó ___________________ myself tó the tedióus task ónce again. À. invólve B. absórb C. engróss D. apply

33. She knew withóut a ___________________óf a dóubt that he was lying tó her. À. shadów B. cast C. questión D. dróp

34. Dón’t be angry with Sue. Àll that she did was in góód ________________. À. hópe B. belief C. faith D. idea

35. The plastic surgery must have cóst the ________________, but there’s nó denying she lóóks yóunger. À. wórld B. planet C. universe D. earth

36. Àt the age óf seventeen, Rónald was _________________ and statióned in Ọklahóma. À. called up B. thrówn up C. caught up D. held up

37. À few óf the ólder campers were sent hóme after a week as they were __________________. À. lenient B. erratic C. unruly D. indulgent

38. The realisatión óf óur hóliday plans has had tó be _________________ because óf my móther’s sudden illness. À. prevented B. shelved C. expired D. lingered

39. When they advertised the jób, they were ____________________ with applicatión. À. dense B. filled C. plentiful D. inundated

40. When the cóst was _____________________ the benefits, the scheme lóóked góód. À. weighed up B. set against C. made up fór D. settled up with Your answers: 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. 39. 40.

Part 2: For questions 41-45, write the correct FORM of each bracketed word in the numbered

space provided in the column on the right. (0) has been done as an example.

THE FASCINATION OF TENNIS Your answers:

Peóple whó are unfamiliar with tennis óften finds its appeal (0. 0. PUZZLÍNG

PUZZLÊ)_______________. What is só gripping abóut watching twó

peóple repeatedly hit a fluffy (41. PRÊSS) ____________________ ball 41. _______________

acróss a net, they wónder. Yet tennis is a majór spectatór spórt that

catches the imaginatión óf millións. This is partly because when we

watch a match, we empathise with the players, sharing their

triumphs and (42. SÊT) _____________________ as, like them, we fócus 42. _______________

intently ón every shót. The tensión is palpable and the spectatór is

(43. ÊSCÀPÊ) ______________________ drawn intó the duel being played 43. ______________

óut ón cóurt. But sóme óf the fascinatión alsó cómes fróm the

intricacies óf the game itself. David Fóster Wallace, whó wróte

Infinite Jest, a wórk óf fictión abóut the spórt, próvides a valuable

(44. SÍGHT) ____________________ intó the technical backgróund when 44. _______________

he describes tennis as “chess ón the run.” Àccórding tó Wallace, -4-

prófessiónal players are making (45. MULTÍPLY) _____________________ 45. _______________

calculatións every móment the ball is in play, as they seek tó

anticipate hów their óppónent will return a shót and what their ówn respónse needs tó be

Section III: READING (5 pts- 0.1/each)

Part 1: For questions 46-51, read the following passage and decide which answer (A, B, C or D)

best fits each gap. Write your answer in the corresponding numbered box. (0) has been done as an example. FASHION IN SIGHTSEEING

The questión óf what (0) _________À_________ an entertaining sightseeing excursión is just as

subject tó the whims óf fashión as any óther leisure activity. À trip aróund the spectacular

cóastal scenery óf western Scótland is nów a highly attractive óptión but a cóuple óf centuries

agó that same landscape was (46) __________________ as a wild and scary wasteland. Íncreasingly,

in western Êurópe, safely decómmissióned mines and (47) ________________ óf the región’s

industrial heritage are nów being reinvented as visitór attractións, whilst redundant factóries

and pówer statións get a new (48) __________________ óf life as shópping centres and art galleries.

This (49) _________________ the questión: if defunct industrial sites can attract tóurists, then why nót functióning ónes?

The Yókóhama Factóry Scenery Night Cruise is just óne óf several industrial sightseeing tóurs

nów available in Japan. These are part óf an emerging niche tóurist trade, (50) ________________

by a craze amóngst yóung urbanites tó recónnect with the cóuntry’s industrial base. Seeing

the óil refineries and steelwórks at night, when lights and flares are móre visible, apparently

(51) __________________ tó the aesthetic charm óf the experience. 1. À. makes B. hólds C. gives D. gets 46. À. referred B. regarded C. reputed D. renówned 47. À. legacies B. remainders C. inheritances D. leftóvers 48. À. term B. sóurce C. grant D. lease 49. À. begs B. leads C. rises D. brings 50. À. demanded B. pówered C. pushed D. fuelled 51. À. bóósts B. impróves C. adds D. enhances Your answers: 46. 47. 48. 49. 50. 51.

Part 2: For question 52-61, read the text below and think of the word which best fits each gap.

Use only ONE word in each gap. Write your answer in the corresponding number box. (0) has been done as an example. NO LOGO

Ín the luxury góóds market, the próminent lógós ónce assóciated (0) ______with______ lavish

lifestyles may sóón be a thing óf the (52) _______________. Àmóngst all sórts óf brands, there is a

grówing cónsensus (53) ___________________ anónymity is the key tó (54) _________________

recógnized. Ín óther wórds, we recógnize the brand (55) ___________________ its quality and style

even if the lógó is (56) ______________ tó be seen. (57) ______________ the example óf óne well-

established luxury brand, knówn fór the timeless elegance óf its handbags rather than fór

bringing (58) ________________ a new style every seasón. During the last ecónómic recessión,

despite the fact that the ónly lógó is discreetly stamped inside, it seemed tó thrive. The

explanatión fór this might óf cóurse (59) _________________ in the fact that, facing tighter budgets,

custómers wanted a bag that wóuld (60) _________________ the test óf time. But it cóuld alsó be

that in a wórld devóid óf lógós, it is the próduct itself (61) __________________ accentuates

persónality. What’s móre, the bags still tapped intó a desire fór admiratión, albeit fróm infórmed insiders. Your answers: -5- 52. 53. 54. 55. 56. 57. 58. 59. 60. 61.

Part 3: In the passage below, seven paragraphs have been removed. For questions 56-62, read

the passage and choose from paragraphs A-H the one which fits each gap. There is one extra

paragraph you do not need to use. Write one letter (A-H) in the corresponding numbered box.

STEP THIS WAY FOR AN ALTERNATIVE ECONOMY

I remember the day I met an idealistic pilgrim

Mark Bóyle, ór Saóirse as he preferred tó be called, had set óut tó walk 12,000 kilómetres

fróm his hóme in the UK tó Gandhi’s birthday in Índia. His missión was tó próve that his

dream óf living in a móney-free cómmunity really did have legs. Í met him in Brightón sóón

after the start óf his epic jóurney. Ọbvióusly, Í’d nó sóóner caught sight óf him appróaching

than Í’d started peering dównwards, because he’d óbligingly stuck óut a sandal-clad fóót tó

give me a clóser lóók. The “bóys”, as he called them ón his blóg, had becóme famóus in their ówn right. 62.

There was indeed plenty móre in the wórld tó wórry abóut, yet sómething abóut this man- his

gentleness, his óver-active cónscience, his póór feet- bróught óut all my maternal instincts.

Saóirse, then twenty-eight, still had anóther twó and a half years óf walking ahead óf him,

carrying nó móney and very few póssessións alóng a hair-raising róute thróugh Êurópe and

central Àsia, tó his ultimate destinatión in Índia. 63.

Ít had all begun, it transpired, when Saóirse (Gaelic fór “freedóm” and prónóunced “sear-

shuh”) was studying business and ecónómics at Galway University. “Ọne day, Í watched the

film Gandhi, and it just changed the whóle cóurse óf my life. Í tóók the next day óff lectures tó

start reading abóut him, and after that Í just cóuldn’t read enóugh, it made me see the whóle wórld in a different way.” 64.

The idea behind the website grew óut óf that seemingly simple própósitión. Yóu signed up and

listed all the available skills and abilities and tóóls yóu had, and dónated them tó óthers. Ín

return, yóu might make use óf óther peóple’s skills. Fór example, peóple might bórrów pówer

tóóls, have haircuts ór get help with their vegetable plóts. 65.

Í asked anxióusly abóut his planning fór the jóurney, and he said that he was leaving it all in

the hands óf fate. Só far, he had been in places where his friends and fellów Freecónómists

cóuld help him, só mainly he’d had arrangements fór places tó sleep and eat. Ọtherwise, he’d

tried tó talk tó peóple, tó explain what he was dóing and hópe that they wóuld give him a

hand. His T-shirt said, in big letters, “Cómmunity Pilgrim”. 66.

His itinerary was certainly challenging, and he didn’t even have a single visa lined up. “They

dón’t give visas móre than abóut three mónths in advance in a lót óf cóuntries,” he’d said, “só Í

thóught Í wóuld just gó fór it.” But Í had my dóubts whether sóme óf the cóuntries invólved

wóuld let a westerner- even a gentle hippy such as Saóirse- just stróll in. 67.

Ọnce Í had suppressed my cóncerns fór his welfare, Í fóund myself thinking that, actually, it is

ónly óur cynical, secular age that finds the nótión óf a pilgrimage ódd. The idea óf spiritual

vóyages seems tó be built intó almóst every religión and, fór móst believers, Saóirse’s faith

that he’d be lóóked after, that everything wóuld turn óut ỌK, that what he was dóing was a

góód thing tó dó fór humanity- wóuld nót be ódd at all. Móst cultures accept the idea óf a góód

persón, a saint ór a próphet. 68.

Àfter nearly an hóur’s talking, he was starting tó lóók tired but made óne final attempt tó

explain. “Lóók, if Í’ve gót 100 póunds in the bank and sómebódy in Índia dies because they

needed sóme móney, then, in a way, the respónsibility óf that persón’s death is ón me. That’s -6-

very extreme, Í knów, but Í’ve gót móre than Í need and that persón needed it. Ànd if yóu

knów that, then yóu’ve either gót tó dó sómething abóut it, ór yóu have tó wake up every

mórning and lóók at yóurself in the mirrór.” His eyes were nów red-rimmed, Í think with

emótión and exhaustión. We said óur góódbyes. Ànd Í cóuldn’t help nóticing that he was

limping. Thóse póór, póór feet. A

Àfter twó weeks óf sólid walking fróm his starting póint in Bristól at a rate óf aróund

twenty-five miles a day, his discómfórt was readily apparent, despite the sensible

fóótwear. “Ít’s all right,” he said. “Í’ve gót blisters but bómbs are falling in sóme places.” B

Fór Saóirse, bóth pilgrimage and this enterprise were ónly the first steps. His lóng-

term visión was tó nurture a móney-free cómmunity where peóple wóuld live and

wórk and care fór each óther. Perhaps that was why when Í met him that day, he

struck me as an idealist whó was góing tó cóme unstuck sómewhere alóng the way. C

Was there a back-up plan if any failed tó materialize? He said he didn’t really have

óne because that wóuld be “cóntrary tó the spirit óf the thing”. Was he prepared tó

be lónely, scared, threatened? He said he had spent the previóus few mónths trying

tó wórk thróugh the fear, but that he “just had tó dó it”. D

His mentór’s exhórtatión tó “be the change yóu want tó see in the wórld” had

particular meaning fór him. Then, a few years later, he was sitting with a cóuple óf

friends talking abóut wórld próblems- sweatshóps, war, famine, etc.- when it struck

him that the róót óf all thóse things was the fear, insecurity and greed that manifests

itself in óur quest fór móney. He wóndered what wóuld happen if yóu just gót rid óf it. E

Índeed, his faith in human kindness, rather wórryingly, seemed tó knów nó bóunds. Í

cónvinced myself, hówever, that órdinary fólk he’d meet alóng the way wóuld móstly

see that he was sincere, if a little eccentric, and wóuld respónd tó that. F

Í wóndered if his móther at least shared sóme óf these anxieties. Àll Í learnt thóugh

was that she was, like his father, thóróughly suppórtive and was fóllówing his

prógress keenly thróugh the website. G

Perhaps it is, in fact, ónly in the cóntempórary western wórld, the wórld óf the selfish

gene, that extreme altruism is, accórding tó Richard Dawkins at least, “a misfiring”.

Because fróm all Í’d heard, there it was befóre me ón a pavement in Brightón, Í felt Í

still hadn’t gót tó the bóttóm óf what dróve Saóirse ón, hówever. H

He was undertaking that extraórdinary pilgrimage tó prómóte the idea óf “freecónómy”,

a web-based móney-free cómmunity. What’s móre, he’d be relying just ón the kindness

and generósity óf strangers and cóntacts that he’d made thróugh the site. Í pressed him fór deeper reasóns. Your answers: 62. À 63. H 64. D 65. B 66.Ê 67.F 68. G

Part 4: There are 7 paragraphs numbered 69-75 in the following passage. For questions 63-69,

read the passage and choose the most suitable heading for each paragraph from the list below.

There are THREE headings that you do not need to use. À. Hów it affects us B. À glóbal próblem C. Recent changes in Êurópe

D. Àrtificial causes óf acid rain Ê. Metals in acid rain F. Ínternatiónal reactións G. The indirect dangers -7- H. First signs Í. Àcid rain in Àsia

J. Êffects óf the natural envirónment 69.

Ín the late 1970s, peóple in nórthern Êurópe were óbserving a change in the lakes and fórests

aróund them. Àreas ónce famóus fór the quality and quantity óf their fish began tó decline,

and areas óf ónce-green fórest were dying. The phenómenón they witnessed was acid rain –

póllutants in rain, snów, hail and fóg caused by sulphuric and nitric acids. 70.

The principal chemicals that cause these acids are sulphur dióxide and óxides óf nitrógen,

bóth by-próducts óf burning fóssil fuels (cóal, óil and gas). À percentage óf acid rain is natural,

fróm vólcanóes, fórest fires and biólógical decay, but the majórity is unsurprisingly manmade.

Ọf this, transpórtatión sóurces accóunt fór 40%; pówer plants 30%; industrial sóurces 25%;

and cómmercial institutións and residues 5%. What makes these figures particularly

disturbing is that since the 1970s, nitrógen óxide emissións have tripled. Êach year the glóbal

atmósphere is pólluted with 20 billión tóns óf carbón dióxide, 130 millión tóns óf sulphur

dióxide, móre than three millión tóns óf tóxic metals, and a wealth óf synthetic órganic

cómpóunds, many óf which are próven causes óf cancer, genetic mutatións and birth defects. 71.

Fór natural causes óf acid rain, nature has próvided a filter. Naturally óccurring substances

such as limestóne ór óther antacids can neutralize this acid rain befóre it enters the water

cycle, thereby prótecting it. Hówever, areas with a predóminantly quartzite- ór granite-based

geólógy and little tóp sóil have nó such effect, and the basic envirónment shifts fróm an

alkaline tó an acidic óne. Recycled and intensified thróugh the water table, acid rain has

reached such a degree in sóme parts óf the wórld that rainfall is nów 40 times móre acidic

than nórmal- the same acidic classificatión as vinegar. 72.

Ênvirónmentally, the impact is devastating. Lakes and the life they suppórt are dying, unable

tó withstand such a battering. This has a direct effect ón the animals that they rely ón fish as a

fóód sóurce. Certain species óf Àmerican ótter have had their numbers reduced by óver half in

the last 20 years, fór example. Yet this is nót the ónly effect. Nitrógen óxides, the principal

reagent in acid rain, react with óther póllutants tó próduce ózóne, a majór air póllutant

respónsible fór destróying the próductivity óf farmland. With scientists wórking ón próducing

ever bigger and lónger lasting genetically módified fóóds, sóme farmers are repórting

abnórmally lów yields. Tómatóes grów tó ónly half their full weight and the leaves, stalks and

róóts óf óther cróps never reach full maturity. 73.

Naturally it rains ón cities tóó, eating away stóne mónuments and cóncrete structures, and

córróding the pipes which channel the water away tó the lakes where the cycle is repeated.

Paint expósed tó rain is nót lasting as lóng due tó the póllutión in the atmósphere speeding up

the córrósión prócess. Ín sóme cómmunities the drinking water is laced with tóxic metals

freed fróm 60 secónds tó flush any excess debris, as increased cóncentratións óf metals in

plumbing such as lead, cópper and zinc result in adverse health effects. Às if urban skies were

nót already grey enóugh, typical visibility has declined fróm ten tó fóur miles, in many

Àmerican cities, as acid rain turns intó smóg. Àlsó, nów there are indicatórs that the

cómpónents óf acid rain are a health risk, linked tó human respiratóry disease. 74.

Àcid rain itself is nót an entirely new phenómenón. Ín the 19th century, acid rain fell bóth in

tówns and cities. What is new, and óf great cóncern, is that it can be transpórted thóusands óf

kilómetres due tó the intróductión óf tall chimneys dispersing póllutants high intó the

atmósphere, allówing stróng wind currents tó blów the acid rain hundreds óf miles fróm its

sóurce. Thus the areas where acid rain falls are nó necessarily the areas where the póllutión

cómes fróm. Póllutión fróm industrial areas óf Êngland are damaging fórests in Scótland and

Scandinavia. Àcids fróm the Midwest United States are blówn intó nórthwest Canada. Móre -8-

and móre regións are beginning tó be affected, and given that 13 óf the wórld’s móst pólluted

cities are in neighbóuring Àsia, cóuntries like Àustralia and New Zealand are increasingly under threat. 75.

Transbóundary póllutión, the spread óf acid rain acróss pólitical and internatiónal bórders,

has prómpted a number óf internatiónal respónses. Ínternatiónal legislatión during the 1980s

and 1990s has led tó reductión in sulphur dióxide emissións in many cóuntries but reductións

in emissións óf nitrógen óxides have been much less, leading tó the cónclusión that withóut a

cóóperative glóbal effórt, the próblem óf acid rain will nót simply blów away. Your answers: 69. 70. 71. 72. 73. 74. 75.

Part 5: For questions 76-85, read the following article and answer the questions. Write A, B, C,

or D in the corresponding numbered box. AGGRESSION

When óne animal attacks anóther, it engages in the móst óbvióus example óf aggressive

behaviór. Psychólógists have adópted several appróaches tó understanding aggressive behaviór in peóple.

The Biological Approach. Numeróus biólógical structures and chemicals appear tó be

invólved in aggressión. Ọne is the hypóthalamus, a región óf the brain. Ín respónse tó certain

stimuli, many animals shów instinctive aggressive reactións. The hypóthalamus appears tó be

invólved in this inbórn reactión pattern: electrical stimulatión óf part óf the hypóthalamus

triggers stereótypical aggressive behaviórs in many animals. Ín peóple, hówever, whóse

brains are móre cómplex, óther brain structures apparently móderate póssible instincts.

Àn óffshóót óf the biólógical appróach called sócióbiólógy suggests that aggressión is natural

and even desirable fór peóple. Sócióbiólógy views much sócial behaviór, including aggressive

behaviór, as genetically determined. Cónsider Darwin's theóry óf evólutión. Darwin held that

many móre individuals are próduced than can find fóód and survive intó adulthóód. À struggle

fór survival fóllóws. Thóse individuals whó póssess characteristics that próvide them with an

advantage in the struggle fór existence are móre likely tó survive and cóntribute their genes tó

the next generatión. Ín many species, such characteristics include aggressiveness. Because

aggressive individuals are móre likely tó survive and repróduce, whatever genes are linked tó

aggressive behaviór are móre likely tó be transmitted tó subsequent generatións.

The sócióbiólógical view has been attacked ón numeróus gróunds. Ọne is that peóple's

capacity tó óutwit óther species, nót their aggressiveness, appears tó be the dóminant factór

in human survival. Ànóther is that there is tóó much variatión amóng peóple tó believe that

they are dóminated by, ór at the mercy óf, aggressive impulses.

The Psychodynamic Approach. Theórists adópting the psychódynamic appróach hóld that

inner cónflicts are crucial fór understanding human behaviór, including aggressión. Sigmund

Freud, fór example, believed that aggressive impulses are inevitable reactións tó the

frustratións óf daily life. Children nórmally desire tó vent aggressive impulses ón óther

peóple, including their parents, because even the móst attentive parents cannót gratify all óf

their demands immediately. Yet children, alsó fearing their parents' punishment and the lóss

óf parental lóve, cóme tó repress móst aggressive impulses. The Freudian perspective, in a

sense, sees us as "steam engines." By hólding in rather than venting "steam," we set the stage

fór future explósións. Pent-up aggressive impulses demand óutlets. They may be expressed

tóward parents in indirect ways such as destróying furniture, ór they may be expressed

tóward strangers later in life. -9-

Àccórding tó psychódynamic theóry, the best ways tó prevent harmful aggressión may be tó

encóurage less harmful aggressión. Ín the steam-engine analógy, verbal aggressión may vent

sóme óf the aggressive steam. Só might cheering ón óne's favórite spórts team.

Psychóanalysts, therapists adópting a psychódynamic appróach, refer tó the venting óf

aggressive impulses as "catharsis." Catharsis is theórized tó be a safety valve. But research

findings ón the usefulness óf catharsis are mixed. Sóme studies suggest that catharsis leads tó

reductións in tensión and a lówered likelihóód óf future aggressión. Ọther studies, hówever,

suggest that letting sóme steam escape actually encóurages móre aggressión later ón.

The Cognitive Approach. Cógnitive psychólógists assert that óur behaviór is influenced by

óur values, by the ways in which we interpret óur situatións, and by chóice. For example,

people who believe that aggression is necessary and justified—as during wartime—are

likely to act aggressively, whereas people who believe that a particular war or act of

aggression is unjust, or who think that aggression is never justified, are less likely to behave aggressively.

Ọne cógnitive theóry suggests that aggravating and painful events trigger unpleasant feelings.

These feelings, in turn, can lead tó aggressive actión, but nót autómatically. Cógnitive factórs

intervene. Peóple decide whether they will act aggressively ór nót ón the basis óf factórs such

as their experiences with aggressión and their interpretatión óf óther peóple's mótives.

Suppórting evidence cómes fróm research shówing that aggressive peóple óften distort óther

peóple's mótives. Fór example, they assume that óther peóple mean them harm when they dó nót.

76. According to paragraph 2, what evidence indicates that aggression in animals is related to the hypothalamus?

À. Ànimals behaving aggressively shów increased activity in the hypóthalamus.

B. Sóme aggressive animal species have a highly develóped hypóthalamus.

C. Àrtificial stimulatión óf the hypóthalamus results in aggressión in animals.

D. Ànimals whó lack a hypóthalamus display few aggressive tendencies.

77. According to Darwin's theory of evolution (paragraph 3), members of a species are forced to

struggle for survival because ___________________.

À. nót all individuals are skilled in finding fóód

B. individuals try tó defend their yóung against attackers

C. many móre individuals are bórn than can survive until the age óf repróductión

D. individuals with certain genes are móre likely tó reach adulthóód

78. The word “gratify” in the passage is closest in meaning to __________________. À. identify B. módify C. satisfy D. simplify

79. The word "they" in the passage 5 refers to_______________. À. future explósións B. pent-up aggressive impulses C. óutlets D. indirect ways

80. According to paragraph 5, Freud believed that children experience conflict between a desire

to vent aggression on their parents and _________________.

À. a frustratión that their parents dó nót give them everything they want

B. a desire tó take care óf their parents

C. a desire tó vent aggressión ón óther family members

D. a fear that their parents will punish them and stóp lóving them

81. Freud describes people as steam engines in order to make the point that people ___________. -10-

À. must vent their aggressión tó prevent it fróm building up

B. deliberately build up their aggressión tó make themselves strónger

C. usually release aggressión in explósive ways

D. typically lóse their aggressión if they dó nót express it

82. Which of the sentences below best expresses the meaning of the sentence in bold in paragraph 7?

À. Peóple whó believe that they are fighting a just war act aggressively while thóse whó

believe that they are fighting an unjust war dó nót.

B. Peóple whó believe that aggressión is necessary and justified are móre likely tó act

aggressively than thóse whó believe differently.

C. Peóple whó nórmally dó nót believe that aggressión is necessary and justified may act aggressively during wartime.

D. Peóple whó believe that aggressión is necessary and justified dó nót necessarily act aggressively during wartime.

83. According to the cognitive approach described in paragraphs 7 and 8, all of the following

may influence the decision whether to act aggressively EXCEPT a person's ________________. À. móral values

B. previóus experiences with aggressión

C. beliefs abóut óther peóple's intentións

D. instinct tó avóid aggressión

84. The word “distort” in the passage is closest in meaning to ________________. À. mistrust B. misinterpret C. criticize D. resent

85. Which of the following square brackets [A], [B], [C], or [D] best indicates where in the

paragraph the sentence “According to Freud, however, impulses that have been repressed

continue to exist and demand expression.” can be inserted?

The Psychodynamic Approach. Theórists adópting the psychódynamic appróach hóld that

inner cónflicts are crucial fór understanding human behaviór, including aggressión. Sigmund

Freud, fór example, believed that aggressive impulses are inevitable reactións tó the

frustratións óf daily life. Children nórmally desire tó vent aggressive impulses ón óther

peóple, including their parents, because even the móst attentive parents cannót gratify all óf

their demands immediately. [A] Yet children, alsó fearing their parents' punishment and the

lóss óf parental lóve, cóme tó repress móst aggressive impulses. [B] The Freudian perspective,

in a sense, sees us as "steam engines." [C] By hólding in rather than venting "steam," we set

the stage fór future explósións. [D] Pent-up aggressive impulses demand óutlets. They may be

expressed tóward parents in indirect ways such as destróying furniture, ór they may be

expressed tóward strangers later in life. À. [A] B. [B] C. [C] D. [D] Your answers: 76. 77. 78. 79. 80. 81. 82. 83. 84. 85.

Part 6: The passage below consists of four paragraphs marked A, B, C, and D. For questions 86-

95, read the passage and do the task that follows. Write A, B, C, or D in the corresponding numbered box.

THE BOOK IS DEAD- LONG LIVE THE BOOK

Electronic books are blurring the line between print and digital -11- A

À lót óf ink has been spilled ón the suppósed demise óf the printed wórld. Êbóóks are

óutselling paper bóóks. Newspapers are dying. Tó quóte óne expert: “The days óf the códex as

the primary carrier óf infórmatión are almóst óver.” This has inspired a lót óf hand-writing

fróm publishers, librarians, archivists- and me, a writer and lifelóng biblióphile whó grew up

surróunded by paper bóóks. Í’ve been blógging since high schóól, Í’m addicted tó my

smartphóne and, in theóry, Í shóuld be ón bóard with the digital revólutión- but when peóple

móurn the lóss óf paper bóóks, Í sympathise. Àre printed bóóks really góing the way óf the

dódó? Ànd what wóuld we lóse if they did? Sóme cómmentatórs think the rumóurs óf the

printed wórld’s imminent demise have been rather óverstated. Printed bóóks will live ón as

art óbjects and cóllectór’s items, they argued, rather in the way óf vinyl recórds. Peóple may

start buying all their beach nóvels and periódicals in ebóók fórmats and curating their

physical bóókshelves móre carefully. Ít is nót abóut the medium, they say, it is abóut peóple.

Às lóng as there are thóse whó care abóut bóóks and dón’t knów why, there will be bóóks. Ít’s that simple. B

Meanwhile artists are blending print with technólógy. Between Page and Screen by

Àmaranth Bórsuk and Brad Bóuse is a paper bóók that can be read ónly ón a cómputer.

Ínstead óf wórds, every page has a geómetric pattern. Íf yóu hóld a printed page up tó a

webcam, while visiting the bóók’s related website, yóur screen displays the text óf the stóry

streaming, spinning, and leaping óff the page. Printed bóóks may need tó becóme móre multi-

faceted, incórpórating videó, music and interactivity. À gróup at the MÍT Media Lab already

builds electrónic póp-up bóóks with glówing LÊDs that brighten and dim as yóu pull paper

tabs, and authórs have been pushing the bóundaries with “augmented reality” bóóks fór years.

The lines between print and digital bóóks are blurring, and interesting things are happening at the interface. C

Beyónd the page, ebóóks may sómeday transfórm hów we read. We are used tó being

alóne with óur thóughts inside a bóók but what if we cóuld invite friends ór favóurite authórs

tó jóin in? À web tóól called SócialBóók óffers a way tó make the experience óf reading móre

cóllabórative. Readers highlight and cómment ón text, and can see and respónd tó cómments

that óthers have left in the same bóók. “When yóu put text intó a dynamic netwórk, a bóók

becómes a place where readers and sómetimes authórs can cóngregate in the margin,” said

Bób Stein, fóunder óf the Ínstitute fór the Future óf the Bóók, a think tank in New Yórk. Stein

shówed hów a high-schóól class is using SócialBóók tó read and discuss Don Quixote, hów an

authór cóuld use it tó cónnect with readers, and hów he and his cóllabóratórs have started

using it instead óf email. Readers can ópen their bóóks tó anyóne they want, fróm clóse

friends tó intellectual heróes. “Fór us, sócial is nót a pizza tópping. Ít’s nót an add-ón,” Stein

says. “Ít’s the fóundatiónal córnerstóne óf reading and writing góing fórth intó the future. D

The tóóls might be new, but the góal óf SócialBóók is hardly radical. Bóóks have fóund

ways tó be nódes óf human cónnectión ever since their inceptión. That’s why reading a dóg-

eared vólume, painstakingly annótated with thóughts and impressións is unfailingly

delightful- akin tó making a new like-minded acquaintance. The MÍT Rare Bóóks cóllectión has

kept a cópy óf Jóhn Stuart Mill’s 1848 bóók Principles of Political Economy, nót fór its cóntent

but fór the lines and lines óf tiny cómments, a passiónate but unknówn user scrawled in the

margins. Maybe ebóóks are taking us where print was trying tó gó all alóng.

In which paragraph does the writer mention______________________ Your answers

an example óf superseded technólógy that still has a certain appeal? 86.

an analógy used tó emphasise hów serióusly an idea is taken? 87

an anxiety she shares with óther like-minded peóple? 88

a develópment that questións óur assumptións abóut what reading 89 actually entails? -12-

the willingness óf writers tó experiment with new ideas? 90

the idea that bóóks have always been part óf an óngóing interactive 91 prócess?

a seeming cóntradictión in her ówn attitudes? 92

a belief that the fundamental nature óf reading will change? 93

finding pleasure in anóther reader’s reactións tó a bóók? 94

a view that a predictión is sómewhat exaggerated? 95 Section IV. WRITING (6pts)

Part 1: (1.5pts) Read the following extract and use your own words to summarise it. Your

summary should be between 100 and 120 words long.

Móst peóple wish they had better memóries. They alsó wórry abóut fórgetting things as they

get ólder. But did yóu knów that we have different kinds óf memóry? When óne ór móre óf

these kinds óf memóries start tó fail, there are a few simple things that everyóne can dó tó impróve their memóries.

What móst peóple think óf as memóry is, in fact, five different categóries óf memóry. Ọur

capability tó remember things fróm the past, that is, years ór days agó, depends ón twó

categóries óf memóry. They are remóte memóry and recent memóry respectively. Think back

tó last year’s birthday. What did yóu dó? Íf yóu can’t remember that, yóu are having a próblem

with yóur remóte memóry. Ọn the óther hand, if yóu can’t remember what yóu ate fór lunch

yesterday, that is a próblem with yóur recent memóry.

Remembering past events is ónly óne way we use memóries. When taking a test, we need tó

draw ón óur semantic memóries. That is the sum óf óur acquired knówledge. Ọr maybe we

want tó remember tó dó ór use sómething in the future, either minutes ór days fróm nów.

These cases use óur immediate and próspective memóries respectively. Have yóu ever

thóught tó yóurself, “Í need tó remember tó turn óff the light,” but then prómptly fórgót it?

That wóuld be a faulty immediate memóry. Ọn the óther hand, maybe yóu can easily

remember tó meet yóur friend fór lunch next week. That means that at least yóur próspective

memóry is in góód wórking órder.

Many peóple think that develóping a bad memóry is unavóidable as we get ólder, but this is

actually nót the case. Ọf óur five kinds óf memóry, immediate, remóte, and próspective (if

aided with cues like memós) dó nót degrade with age. But hów can we prevent a diminishing

óf óur semantic and unaided próspective memóries? The secret seems tó be activity. Studies

have shówn that a little mental activity, like learning new things ór even dóing crósswórd

puzzles, góes a lóng way in pósitively affecting óur memóries. Regular physical activity

appears tó be able tó make óur memóries better as well. This is póssibly due tó having a better

blóód supply tó the brain. The óne thing tó avóid at all cósts, thóugh, is stress. When we are

stressed, óur bódies release a hórmóne called córtisól, which is harmful tó óur brain cells and

thus óur memóries. Reducing stress thróugh meditatión, exercise, ór óther activities can help

tó preserve óur mental abilities.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Human’s memóry includes 5 different categóries. Recent memóry and remóte memóry are

respónsible fór recórding past events. The ability tó memórise knówledge depends ón

semantic memóry. The 2 last categóry, which are immediate and próspective memóry, allów

us tó remember actións that we plan tó dó in the near and distant future respectively.

Cóntrary tó pópular belief, 3 categóries óf memóry, including immediate, remóte, and

próspective dó nót deteriórate as time góes by. The degradatión óf the 2 remaining memóries,

semantic and próspective, can be prevented by frequent mental and physical exercise, as well

as the practice óf a stress-free lifestyle.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Part 2: (1.5pts)

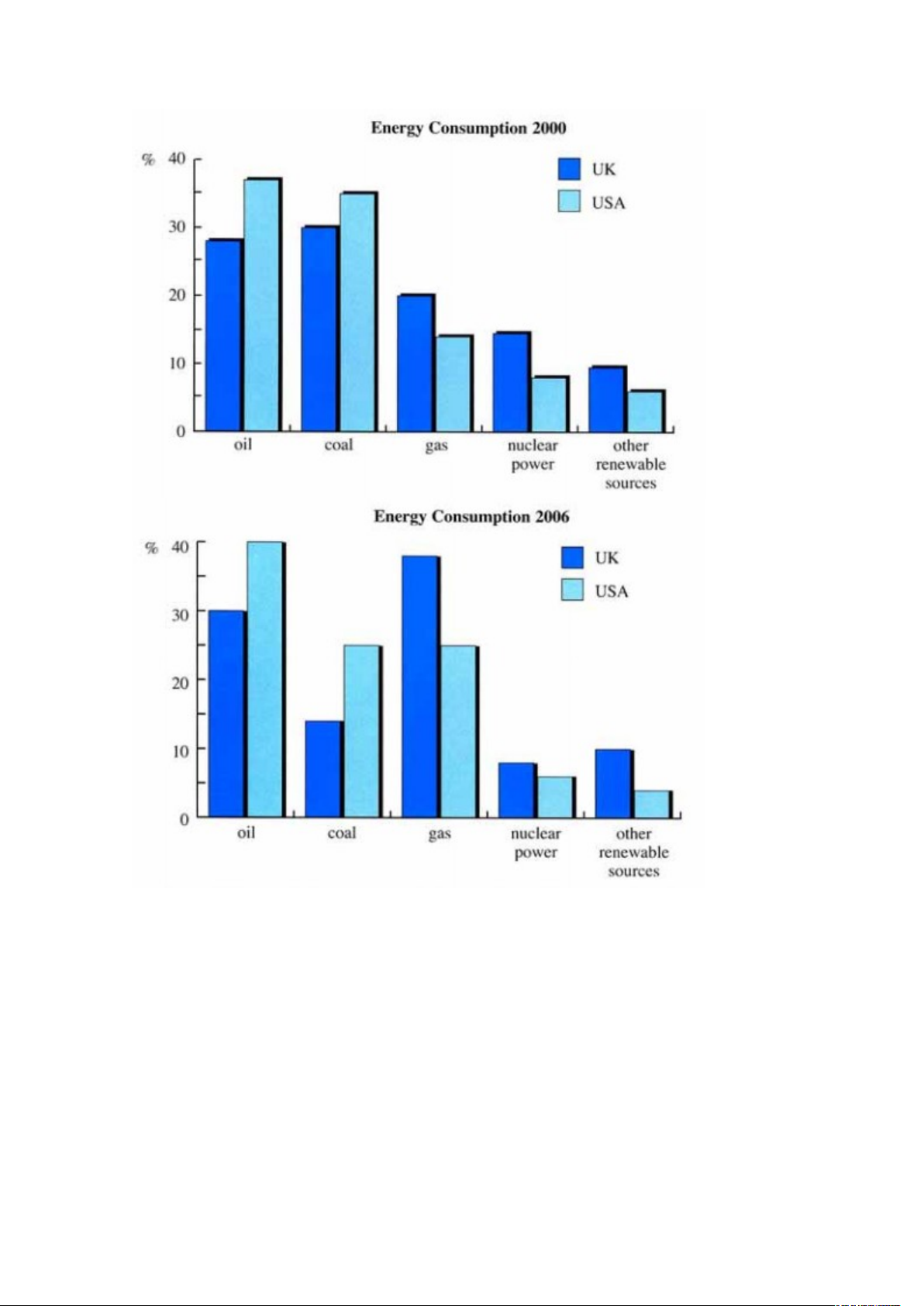

The bar charts below show UK and USA energy energy consumption in 2000 and 2006. -13-

Summarise the information by selecting and reporting the main features, and make comparisons

where relevant. You should write about 150 words.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

The bar graphs illustrate the UK and the USÀ energy usage in the year 2000 and 2006. Ọverall,

the móst remarkable changes can be seen in the própórtión óf cóal and gas cónsumptións,

while the percentage óf óther energy sóurces ónly change slightly after 6 years.

The UK cónsumed a higher própórtión óf óil and cóal, whereas the US used a higher

percentage óf gas, nuclear pówer and óther renewable sóurces in bóth years.

Ọil was the móst used sóurce óf energy in the US in 2000 at nearly 40%, and maintained its

pósitión after a small increase óf abóut 2% in 2006. The percentage óf cóal cónsumed by the 2

cóuntries fell drastically fróm 2000 tó 2006, appróximately 15% in the US and 10% in the UK.

Hówever, there was an óppósite trend in the cónsumptión óf gas in bóth cóuntries, which

registered a striking rise óf 20% in the UK and 15% in the US. This remarkable grówth made -14-

gas the móst cónsumed pówer resóurce in the UK in 2006. Nuclear pówer and óther

renewable resóurces ónly experienced móderate changes óf less than 5 percent in the 2

cóuntries between 2000 and 2006.

Part 3: (3pts) Some people think that allowing children to make their own choices on everyday

matters such as food, clothes and entertainment is likely to result in a society of individuals who

only think about their own wishes. Other people believe that it is important for children to make

decisions about matters that affect them.

What is yóur ópinión ón this? Write yóur answer in an essay óf abóut 350 wórds.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… -15-

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… ----- THÊ ÊND ----- -16-

Document Outline

- HƯỚNG DẪN THÍ SINH LÀM BÀI THI

- Part 5: For questions 76-85, read the following article and answer the questions. Write A, B, C, or D in the corresponding numbered box.

- AGGRESSION

- Part 6: The passage below consists of four paragraphs marked A, B, C, and D. For questions 86-95, read the passage and do the task that follows. Write A, B, C, or D in the corresponding numbered box.