SO

GIAO

Dl)C

VA

DAO

T~O

DE

THI

CHQN

DOI

TUYEN

HQC

SINH

GIOI

QUOC

GIA

NAM

HQC

2020

-

2021

MON:

TIENG

ANH

(VONG

1)

Thcri

gian:

180

phut,

(khon

g kS

thcri

gian

phat

dS)

(DJ

thi

g

6m

co

12

trang

, thi

sinh

lam

bai

tn1c

tiip

vao

ai)

I. LISTENING (2.0 points)

Part

1:

You

will

hear part of a tutorial between two students and their tutor.

The

students

are

doing

a

research

project to

do

with computer

use.

Listen

and decide whether the following sentences are

true

(T)

or false

(F).

True(n

/

Fa

lse (F)

1.

Sarni

;I.Ild

Iren

e decided

to

do

a

survey

about

access

to

computer facilities

1 .

...

.

.....

.

.....

because

no

one

has

investigated

it

before.

2.

Sarni

and

Irene

had

problems

with

the

reading

for

their project

because

not

much

had

been

written about

the

topic.

2 .

............

.

..

3.

Sarni

and

Irene get the

main

data

in

their

survey

from

observation

of

students.

3 .

...............

4.

The

tutor suggests that

one

problem

with

the

survey

was

limitation

in

the

number of students

involved.

4.

.

...............

5.

77%

of

students surveyed thought that a

booking

system

would

be

the

best

solution.

5.

.

..............

Part

2:

Complete

the

table

below.

Write

NO

MORE

THAN

THREE

WORDS

for

each

answer.

Write

·

the

corresoondine

numbered

blanks

Date

Event

.

Importance

for

art

3000BC

rice

farmers

from

(6)

built

temples

with

wood

and

stone

carvings

settled

in

Bali

14

th

century

introduction

of

Hinduism

artists

employed

by

(7)

and

focused

on

epic

narratives

1906

Dutch

East

Indies

Company

art

became

expression

of

opposition

to

(8)

established

1920s

beginning

of

(9)

encouraged

use

of

new

materials,

techniques

and

subjects

1945

independence

new

art

with

scene

of

(10)

(e.g.

harvests)

reflecting

national

identity

Part

3:

For

questions

11-15,

listen

to

a

radio

news

report about

'Google',

a popular

Internet

search

engine

and answer

the

questions.

Write

NO

MORE

THAN

FIVE

WORDS

taken

from

the

recording

for

each

answer.

11.

What

way

did

Google

rely

on

to

market

its

product?

12.

What

position

did

Goog

le achieve last

week

as

the

Internet search

engine

for

America

Online?

13.

What

group

of

people

was

mentioned

to

fa

vour

Google

as

a search

engine?

14.

What

verb

is

the

word

'google' said

to

be

replacing?

15.

Who

invented the original term 'googol'?

Trang

1/

12

Part

4.

You

will hear part

of

a radio interview with

an

economist.

For

questions 1-5, choose the answer

(A,

B.

C or

D),

which fits

best

according to what you hear.

16.

According

to

the

Fawcett

Society,

...

A. women would need to work into their eighties to earn as much money as men.

B. good qualifications aren't necessarily rewarded with high wages.

C. women will never earn as much as men.

D. more women have degrees than men.

17.

What

is

said

about

careers

advice

in

schools?

A.

It

has been improved but it is still inadequate.

B.

It

is now quite good for girls but boys are being neglected.

C.

There is no advice for girls that are ambitious.

D.

Girls are always encouraged not to be ambitious.

18.

According

to

Jim,

...

A. women are to blame for not insisting on higher wages.

.

B.

new government policies have solved most

of

the problems.

C.

there is nothing more the government can do.

D. women shouldn't necessarily be encouraged to change their choice

of

career.

19.

A London School

of

Economics

report showed that

...

A.

women who worked part-time found it difficult to get a full-time

job

later on.

B.

after having children, women find it harder to earn as much money as men.

C.

women find it hard to find a

job

after having children.

D.

most women want a full-time

job

after having a child.

20.

What

does

the

"stuffed shirt" policy

mean?

A.

Women are being forced to choose between family commitments and work.

B.

Only men can have part-time senior positions.

C. Women don't get the opportunity to train for high-powered jobs.

D.

No woman can have a senior position.

II.

LEXI

CO-GRAMMAR

(1

point) . .

Part

1.

For questions 21-28, choose the correct answer A,

B,

C,

or D

to

each

of

the following questions.

21.

Most people feel a slight

............

of

nostalgia as they think back on their schooldays.

A.

feeling

B.

surge

C.

pang D. chain

22.

The cost

of

a new house in the UK has become

............

high over the last few years.

A. totally

B.

astronomically

C.

blatantly

D.

utterly

23. Successful athletes cannot afford to be

............

; they need to stay cool and focused.

A. highly-paid B. highly-motivated

C.

highly-trained

D.

highly-strung

24.

Ifwe

have to pay a £1,000 fine, then

.............

We're not going to win a fight with the Tax Office.

A. so be it B. be it so

C.

thus be it

D.

be it thus

25. The restaurant has

____

recently, and the food is much better now.

A. had its hands full B. lived hand to mouth

C.

changed hands

D.

gained the upper hand

26. "There is no further treatment we can give," said Jekyll." We must let the disease take its

..........

"

A. course

B.

end

C.

term

D.

way

27. Christopher is prepared to

....

·

........

his professional reputation on the idea that this stone circle

originally had an astronomical purpose.

Trang 2/12

A.

risk

B.

bet

C.

gamble

D.

stake

28.

I went to see the boss about a pay rise and he brushed me

_____

with a weak excuse about a

business dinner and left me standing there!

C.

around

•

D.

off

A.

up

B.

away

Part

2:

Complete

the

text by

writinf{

the

correctform

o_fthe

word

in

capitals.

The last orangutans

The orangutan

is

our closest living relative among the animal species. There is

just a two percent difference in our DNA and this perhaps accounts for the

number

of

tourists flocking to the rainforests

of

south-east Asia in the hope

of

seeing the creatures in close (29. PROXIMATE)

..............

Just glimpsing one

is

an unforgettable experience. With logging and oil-palm production destroying

their precious habitat at an ever

(30.

QUICK)

...............

pace, the animal is on

the brink

of

extinction. Mass tourism itself must take part

of

the blame for the

creature's demise, but for anyone determined to see one, a rehabilitation center

offers the chance to

do

so

in a regulated environment. The recent discovery

of

a

new population

off

orangutans in a largely (31. ACCESS)

...................

area

of

Borneo

is

a bit

of

positive news in an otherwise bleak situation. A team

of

conservationists has (32. LIGHT)

................

the need to protect the group,

both by discouraging unwanted tourists, and by ensuring the remote region

remains untouched by the sort

of

development that has done so much damage

elsewhere.

29

............

..

30

..............

.

31

..............

.

32

..............

.

Part.3:

Choose

the

word(s)

that

is

CLOSEST

in

meaning

to

the underlined word(s):

33. The collapse

of

the stock market in 1929 signaled the beginning

of

the Depression.

A. debt B. failure

C.

rise D. rebirth

34. ·

YOU

never really know where you are with her as she just blows hot and cold.

A.

keeps changing her mood

B.

keeps going ·

C.

keeps testing

D.

keeps taking things

35.

The government must be able to prevent an deter threats to our homeland as well as detect impending

danger before attacks or incidents occur.

A.

irrefutable B. imminent

C.

formidable D. absolute

36.

I'm

sorry I can't go to the movies with you this weekend -

I'm

up

to

my ears in work.

A.

very busy

B.

very bored

C.

very scared D. very idle

Part

4:

Choose

the word(s) that is OPPOSITE

in

meaning

to

the underlined word(s):

37.

Tom was too wet behind the

ears

to be in charge

of

such a difficult task.

A. full

of

experience

B.

lack

of

responsibility

C.

without money

D.

full

of

sincerity

38. i

take

my

hat off to all those people who worked hard to get the contract.

A. congratulate

B.

unrespect

C.

welcome

D. encourage

39.

It

is

an ideal opportunity to make yourself memorable with employers for the right reasons by asking

sensible questions.

A.

theoretical

B.

silly

C.

practical D. burning

40.

In some countries, the disease burden could be prevented through environmental improvements.

A.

something to suffer

B.

something enjoyable

C.

something sad D. something to entertain

T..-""l'"t,""

"l

/1

"'I

~-

A."-L-'.L.....,A..,1,,

"'-..II

,-,-.J

..,

..........

l,J,

Part

1:

For questions 41-50, read the following passages and decide which answer (A, B, C or

D)

best fits each gap.

Urban gum crime

The Mayan tribes

of

South America would chew chicle, a natural form

of

rubber, while the Ancient

Greeks (

41

)

____

the resin

of

a mastic shrub. In modem Britain, we like to chew sticks and tablets

of

manufactured

gum-and

(42)

____

ofthe

tasteless sticky residue on the ground.

However, recent legislation in the UK means that used chewing gum is now (43)

____

as

litter and anyone who drops it on the pavement or (44)

____

in any public place is committing a

crime and can be fined. Some areas have council litter wardens who can ( 45)

____

on-the-spot fines.

A new government campaign ( 46)

___

the extent

of

the problem and aims to ( 4

7)

__

_

awareness about this anti-social habit, for instance with posters in shopping areas. Throughout the UK,

councils spend 150 million pounds a year ( 48)

___

chewing gum from the streets, and 4 million

of

that

is in London alone. Indirectly, this is (49)

____

taxpayers' money. (50)

___

is the main removal

method, but use is also made

of

chemical sprays, freezing, pressurized water and steam.

41.

A.

favoured

B. approved

C.

commended

D.

indulged

4

2.

A. discard

B.

dispose

C.

dispense

D.

disperse

43.

A.

ranked

B. classified

C.

systematised

D.

codified

44.

A.

at any rate

B. anyway

C.

even

so

D.

indeed

45.

A.

fix

B.

compel

C.

impose

D. prescribe

46.

A.

features

B. declares

C.

focuses

D.

highlights

47. A. make

B. provoke

C.

grow

D.

heighten

48. A. erasing

B.

spraying

C.

removing

D.

washing

49.

A.

no doubt

B. for sure

C.

of

course

D.

within reason

50.

A.

Scraping

B. Clawing

C.

Scratching

D. Rubbing

Part

2:

For questions 51--00,fil/

each

blank

with

ONE

suitable

word.

Life on a small island may seem very inviting ( 51)

___

the tourists who spend a few weeks

there in the summer, but the realities

of

living on what is virtually a rock surrounded by water are quite

different from (52)

___

the casual visitor imagines. Although in summer the island villages are full

of

people, life and activities, when the tourist season is (53)

___

many

of

the shop owners shut down

their businesses and (54)

___

to the mainland to spend the winter in town. Needless to say,

(55)

___

who remain on the island, either by choice or necessity, face many hardships. One

of

the (56)

___

of

these is isolation, with its many attendant problems. When the weather is bad, (57)

__

is

often the case in winter, the island is entirely cut off; this means not only that people cannot have goods

(58)

___

but also that a medical emergency can be fatal to someone confined to an island. At times

telephone (59)

___

is cut off, which means that no word from the outside world can get through.

Isolation and loneliness are basic reasons why so many people have left the islands for a better and more

(60)

___

life in the mainland citie;, in spite

of

the fact that this involves leaving "home".

Part

3.

The

passage below consists

of

four paragraphs marked A,

B,

C and

D.

For questions

61-70,

read

the passage and write your answers (A,B,C or

D)

in

the corresponding

column

provided.

CHEER UP: LIFE ONLY GETS BETTER

Human

's

capacity for solving problems has

been

improving out lot for 10,000 years, says Matt Ridley

A. The human race has expanded in I 0,000 years from less than

10

million people to around 7 billion.

Some live in even worse conditions than those in the Stone Age. But the vast majority are much better fed

and sheltered, and much more likely to live to old age than their ancestors have ever been.

It

is likely that

by 211 O humanity will be much better

off

than it is today and so will the ecology

of

our planet. This view,

which I shall call rational optimism, may not be fashionable but it is compelling. This belief holds that the

world will pull out

of

its economic and ecological crises because

of

the way that markets i goods, services

and ideas allow human beings to exchange and specialise for the betterment

of

all. But a constant drumbeat

of

pessimism usually drowns out this sort

of

talk. Indeed,

if

you dare to say the world is going to go on

being better, you are considered embarrassingly mad.

Trang 4/12

B.

Let me make a square concession at the

start.:

the pessimists are right when they say that

if

the world

continues as it is, it will end in disaster. If agriculture continues to depend

on

irrigation and water stocks

are depleted, then starvation will ensue. Notice the word

"if'.

The world will

not

continue as it is. It is my

proposition that the human race has become a collective problem - solving machine which solves

problems by changing its ways. It does so through invention driven often

by

the marker: scarcity drives up

price and that

in

turn encourages the development

of

alternatives and efficiencies. History confirms this.

When whales grew scarce, for example, petroleum was used instead as a source

of

oil. The pessimists'

mistake is extrapolating: in other words, assuming that the future is

just

a bigger version

of

the past. In

1943 IBM' s founder Thomas Watson said there was a world market for

just

five computers - his remarks

were true enough at the time, when computers weighed a

ton

and cost a fortune.

C. Many

of

today's extreme environmentalists insist that the world has reached a 'turning point' - quite

unaware that their predecessors have been making the same claim for 200 years. They also maintain the

only sustainable solution is to retreat - to halt economic growth and enter progressive economic recession.

This means not just that increasing your company' s sales would be a crime,

but

that the failure to shrink

them would be too. But all this takes no account

of

the magical thing called the collective human brain.

There was a time in human history when big-brained people began to exchange things with each other, to

become better

off

as a result. Making and using tools saved time - and the state

of

being

'better

off'

is, at

the end

of

the day, simply time saved. Forget dollars

of

gold. The true measure

of

something's worth is

indeed the hours it takes to acquire it. The more humans diversified as consumers and specified as

producers, and the more they exchanged goods and services, the better

off

they became.

And

the good

news is there is no inevitable end to this process.

D.

I am aware that an enormous bubble

of

debt has burst around the world, with all that entails.

But

is this

the end

of

growth? Hardly. So long as somebody allocates sufficient capital to innovation,

then

the credit

crunch will not prevent the relentless upward march

of

human living standards.

Even

the Great Depression

of

the 1930s, although an appalling hardship for many, was

just

a dip

in

the slope

of

economic progress.

All sorts

of

new products and industries were born during the depression: by 1937,

40%

of

Dupont's

sales

came from products that had barely existed before 1929, such as ~namels and cellulose film. Growth will

resume - unless it is stifled by the wrong policies. Somebody, somewhere, is still tweaking a piece

of

software, testing a

new

material,

of

transferring a gene that will enable

new

varieties

of

rice

to

be

grown in

African soils. The latter means some Africans will soon be growing and selling more food, so they will

have more money to spend. Some

of

them may then buy mobile phones from a western company.

As

a

consequence

of

higher sales, an employee

of

that western company may get a pay rise, which she may

spend on a pair

of

jeans

made from cotton woven

in

an African factory.

And

so on. Forget wars, famines

and poems, This is history's greatest theme: the metastasis

of

exchange and specialisation.

Para2raoh

61. exemplifv how short-term gloom tends to lift?

62. mention a doom-laden pro

63. express his hope that progress is not hindered

by

abominable decisions?

64. acknowledge trving to find common ground with his potential adversaries?

65. identify unequivocally

how

money needs to be invested?

66. suggest that his views are considered controversial?

67. indicate an absurd scenario resulting from an opposing

view

to·his own?

68. mention the deplorable consequences

of

taking a positive stance?

70. give an examole

of

well-intentioned ongoing research?

T

...

___

r-

/-t..,,

,------------

Part

4:

Read the following passage, for questions 71-75, choose correct heading

for

sections B - F

from the list

of

headi11gs

·

A.

Japan has a significantly better record in tenns

of

average mathematical attainment than England and

Wales. Large sample international comparisons

of

pupils' attainments since

the

1960s have established

that not only did Japanese pupils at

age

13

have better scores

of

average attainment, but there

was

al

so a

larger proportion

of

'low' attainers in England, where, incidentally, the variation in attainment scores

was

much greater. The percentage

of

Gross National Product spent

on

education

is

reasonably similar in the

two countries,

so

how

is

this higher and more consistent attainment

in

maths achieved?

B.

Lower secondary schools in Japan cover three school years,

from

the seventh grade (age

13)

to

the

ninth grade

(age.

15).

Virtually

all

pupils at this stage attend state schools: only 3 per cent

are

in

the

private sector. Schools are usually modem in design, set well back

from

the

road-

and spacious inside.

Classrooms are large

and

pupils sit

at

single desks

in

rows.

Lessons last

for

a standardised

50

minutes

and

are always followed

by

a

IO-minute

break, which gives the pupils a chance

to

let off steam. Teachers

begin with a fonnal address

and

mutual bowing, and then concentrate

on

whole-class teaching.

Classes

are

large - usually about

40

-

and

are

unstreamed. Pupils stay

in

the same class

for

all

lessons

throughout the school and develop considerable class identity

and

loyalty. Pupils attend

the

school

in

their

own neighbourhood, which in theory removes ranking

by

school.

In

practice in Tokyo, because

of

the

relative concentration

of

schools, there

is

some

competition

to

get into

the

'better' school in a particular

area.

C.

Traditional ways

of

teaching fonn

~he

basis

of

the

lesson

and

the

remarkably quiet classes

take

their

own notes

of

the

points

made

and

the examples demonstrated. Everyone

has

their own

copy

of

the

textbook supplied

by

the central education authority, Monbusho,

as

part

of

the concept

of

free

compulsory

education

up

to

the

age

of

15.

These textbooks

are,

on

the

whole,

small, presumably inexpensive

to

produce, but well set out

and

logically developed.

(One

teacher

was

particularly keen

to

introduce

~olour

and

pictures into maths textbooks:

he

felt

this would

make

them

more

accessible

to

pupils brought

up

in a

cartoon culture.) Besides approving textbooks,

Monbusho

also

decides the highly centralised national

curriculum and how it

is

to

be

delivered.

D.

Lessons all follow the same pattern. At

the

beginning,

the

pupils put solutions

to

the homework

on

the

board, then the teachers comment, correct or elaborate

as

necessary. Pupils mark their own homework: this

is

an

important principle in Japanese schooling

as

it

enables pupils

to

see where

and

why

they

made

a

mistake,

so

that these can

be

avoided

in

future.

No

one

minds

mistakes or ignorance

as

long

as

you

are

prepared

to

learn

from

them.

After the homework has been discussed,

the

teacher explains

the

topic

of

the lesson, slowly

and

with a

lot

of

repetition

and

elaboration. Examples

are

demonstrated

on

the board; questions from the textbook

are

worked through first with the class,

and

then

the

class

is

set questions

from

the textbook

to

do

individually.

Only

rarely

are

supplementary worksheets distributed in a maths class.

The

impression

is

that

the

logical

nature

of

the textbooks and their comprehensive coverage

of

different types

of

examples, combined with

the

relative homogeneity

of

the class, renders work sheets unnecessary. At this point, the teacher would

circulate

and

make sure that aUthe pupils

were

coping

well.

E.

It

is

remarkable that large,

mixed-al:>ility

classes could

be

kept together for maths throughout all their

compulsory schooling

from

6

to

15.

Teachers

say

that they give individual help

at

the end

of

a lesson or

after school, setting extra work

if

necessary. In observed lessons,

any

strugglers would-

be

assisted by

the teacher or quietly seek help

from

their neighbour. Carefully fostered class identity makes pupils

keen

to

help each other - anyway, it

is

in their interests since

the

class progresses together.

This scarcely seems adequate help

to

enable slow learners

to

keep

up.

However, the Japanese attitude

towards education runs along the lines

of

'if you work hard enough, you can

do

almost anything'. Parents

are kept closely infonned

of

their children's progress

and

will play a part in helping their children

to

keep

up

with class, sending them

to

'Juku' (private evening tuition)

if

extra help

is

needed

and

encouraging them

to work harder. It seems

to

work,

at

least for

95

per cent

of

the

school population.

F.

So

what are the major contributing factors in

the

success

of

maths teaching? Clearly, attitudes are

important. Education

is

valued

grea~ly

in Japanese

cul~~;

maths

is

recognised as . an important

compulsory subject throughout schoolmg;

and

the emphasis

1s

on

hard

wo

rk

coupled with a

fo

cus

on

accuracy.

Trang 6/12

Other relevant points relate to the supportive attitude

of

a class towards slower pupils, the lack

of

competition within a class, and the positive emphasis on learning for oneself and improving one's own

standard. And the view

of

repetitively boring lessons and learning the facts by heart, which is sometimes

quoted in relation to Japanese classes, may be unfair · and unjustified. No poor maths lessons were

observed. They were mainly good and one or twp were inspirational.

List

of

Headings

I The influence ofMonbusho

II Helping less successful students

III The success

of

compulsory education

IV Research findings concerning achievements in Maths

V The typical format

of

a Maths lesson

VI Comparative expenditure on Maths education

VII Background to middle-years education in Japan

VII The key to Japanese successes in Maths education

IX The role

of

homework correction

Example: Section A

.....

. IV

.....

.

71. Section B

73.

Section D

75.

Section F

72. :Section C

74. Section E

Part 5:

for

questions 76-85, read the passage and choose the best answer.

Although only a small percentage

of

the electromagnetic radiation that is emitted by the Sun is

ultraviolet (UV) radiation, the amount that is emitted would be enough to cause severe damage to most

forms

of

life on Earth were it all to reach the surface

of

the earth. Fortunately, all

of

the Sun's ultraviolet

radiation does not reach the earth because

of

a layer

of

oxygen, called the ozone layer, encircling the earth

in the stratosphere at an altitude

of

about

15

miles above the earth. The ozone layer absorbs much

of

the

Sun's ultraviolet radiation and prevents it from reaching the earth.

Ozone is a form

of

oxygen in which each molecule consists

of

three atoms

(03)

instead

of

the two

atoms

(02)

usually found in an oxygen molecule. Ozone forms in the stratosphere in a process that is

initiated by ultraviolet radiation from the Sun. UV radiation from the Sun splits oxygen molecules with

two atoms into

free

oxygen atoms, and each

of

these unattached oxygen atoms then joins up with an

oxygen molecule to form ozone. UV radiation is also capable

of

splitting up ozone molecules; thus ,ozone

is constantly forming, splitting, and reforming in the stratosphere. When UV radiation is absorbed during

the process

of

ozone formation and reformation, it is unable to reach Earth and cause

damage

there.

. Recently, however, the ozone layer over parts

of

the earth has been diminishing. chief among the

culprits in the case

of

the disappearing ozone, those that are really responsible, are the chlorofluorocarbons

(CFCs). CFCs meander up from Earth into the stratosphere, where they break down and release chlorine.

The released chlorine reacts with ozone in the stratosphere to form chlorine monoxide (ClO) and oxygen

(02). The chlorine then becomes free to go through the cycle over and over again. One chlorine atom can,

in fact, destroy hundreds

of

thousands

of

ozone molecules in this repetitious cycle, and the effects

of

this

destructive process are now becoming evident.

76.

According

to

the

passage,

ultraviolet

radiation

from

the

Sun

...

A.

is causing serve damage to the earth's ozone layer

B.

is only a fraction

of

the Sun's electromagnetic radiation

C.

creates electromagnetic radiation

D.

always reaches the earth

Trang

7/12

77

.

The

word 'encircling'

in

paragraph I

is

closest

in

meaning

to

...

A. rotating B. attacking • C. raising D. surrounding

78.

It

is

stated

in

the

passage that

the

ozone

layer

...

A. enables ultraviolet radiation to reach the earth

C. shields the earth from a lot

of

ultraviolet radiation

B. reflects ultraviolet radiation

D. reaches down to the earth

79.

According

to

the

passage,

an

ozone

molecule

..

.

A. consists

of

three oxygen molecules

B.

contains more oxygen atoms than the usual oxygen molecule does

C. consists

of

two oxygen atoms

D. contains the same number

of

atoms as the usual oxygen molecule

80.

The

word free could

be

best replaced

by

...

A. liberal B. gratuitous C. unconnected

D.

emancipated

81.

Ultraviolet radiation causes oxygen molecules

to

...

A. rise to the stratosphere B. burn up ozone molecules

C. split up and reform as ozone D. reduce the number

of

chlorofluorocarbons

82.

The

pronoun it refers

to

...

A. radiation B. process

C. formation

D. damage

83.

The

word culprits

is

closest

in

meaning

to

...

A. Guilty parties B. Detectives C. Group members

D. Leaders

84.

According

to

the

passage, what

happens

after a

chlorine

molecule

reacts

with

an

ozone

molecule?

A. The ozone beaks down into three oxygen atoms B. Two different molecules are created

C. The two molecules combine into one molecule D. Three distinct molecules result

85.

The

paragraph following

the

passage most likely

discusses

...

A. the negative results

of

the cycle

of

ozone destruction

B. where chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) come from

C. the causes

of

the destruction

of

ozone molecules

D.

how

electromagnetic radiation is created

IV.

WRITING (2.5 points)

Part

1.

Read the following extract and use

your

own words to summarise

it.

Your summary should be

between 100

and

120 words long.

Today, the majority

of

the worl.d's population may not be vegetarians, but vegetarianism is rapidly

gaining popularity. People who decide to become vegetarians generally have very strong feelings about the

issue and may choose a vegetarian diet for different reasons. Health issues, awareness

of

environmental

problems and moral issues are three common arguments in favour

of

vegetarianism that are quite

convincing.

Many non-vegetarians claim that a vegetarian diet does not give a person the necessary vitamins

and proteins that their body needs. However, doctors and medical associations say that a vegetarian diet is

able to satisfy the nutritional needs

of

people

of

all ages. All the nutrients and proteins one's body needs

can

be found

in

vegetables, nuts and grains, as well as in dairy products. Eating meat may be an easy way

to

get

the protein one needs, but it is not the only way.

Vegetarians also argue that the meat industry is the source

of

many environmental problems that

could

be

eliminated

if

people ate less meat or even stopped eating it altogether. Raising livestock for the

meat

industry takes a huge toll

on

the world's natural resources; for example forests are cut down to clear

land for crops to feed livestock

or

for pastureland. This in turn leads to an increase in global warming, loss

of

topsoil and loss

of

plant and animal life.

Trang 8/12

Finally, many people refrain from eating meat for ethical reasons. They object to taking the life

of

another living creature in order to satisfy their hunger. Moreover, they argue that we inflict great pain and

suffering on animals that are raised for meat. Poultry and livestock raised

on

factory farms are kept under

abominable conditions, confined in areas that hardly allow them to move, fed with antibiotics and, in the

end, they are cruelly slaughtered.

:· Becoming a vegetarian might not appeal to everyone, but it is a choice that is gaining popularity as

.

our awareness

of

health and environmental issues as well as our ~oncem for animal welfare is growing. It

is

also becoming more feasible as restaurants and supermarkets increasingly cater for the vegetarian

rnadret

r

Part

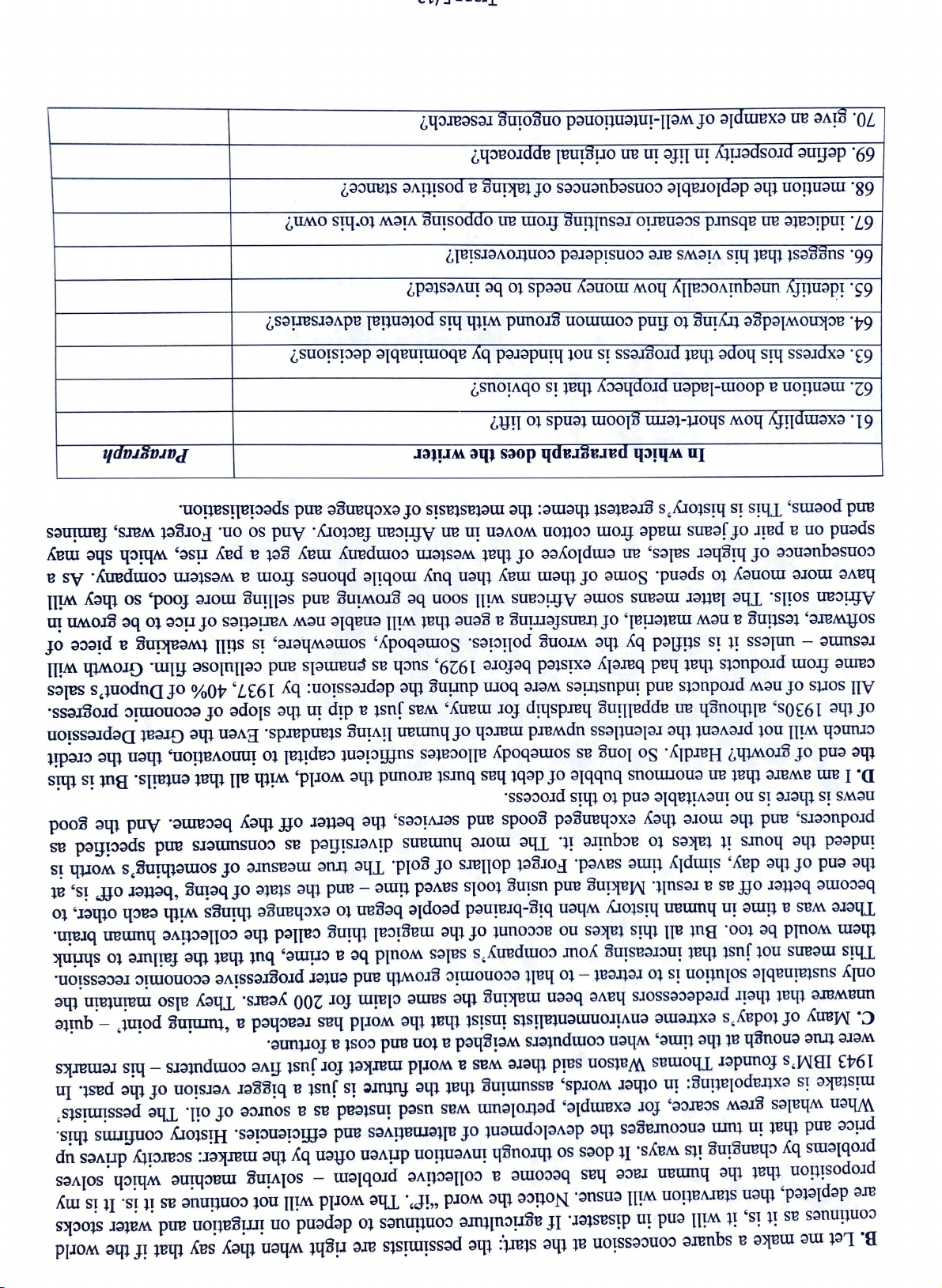

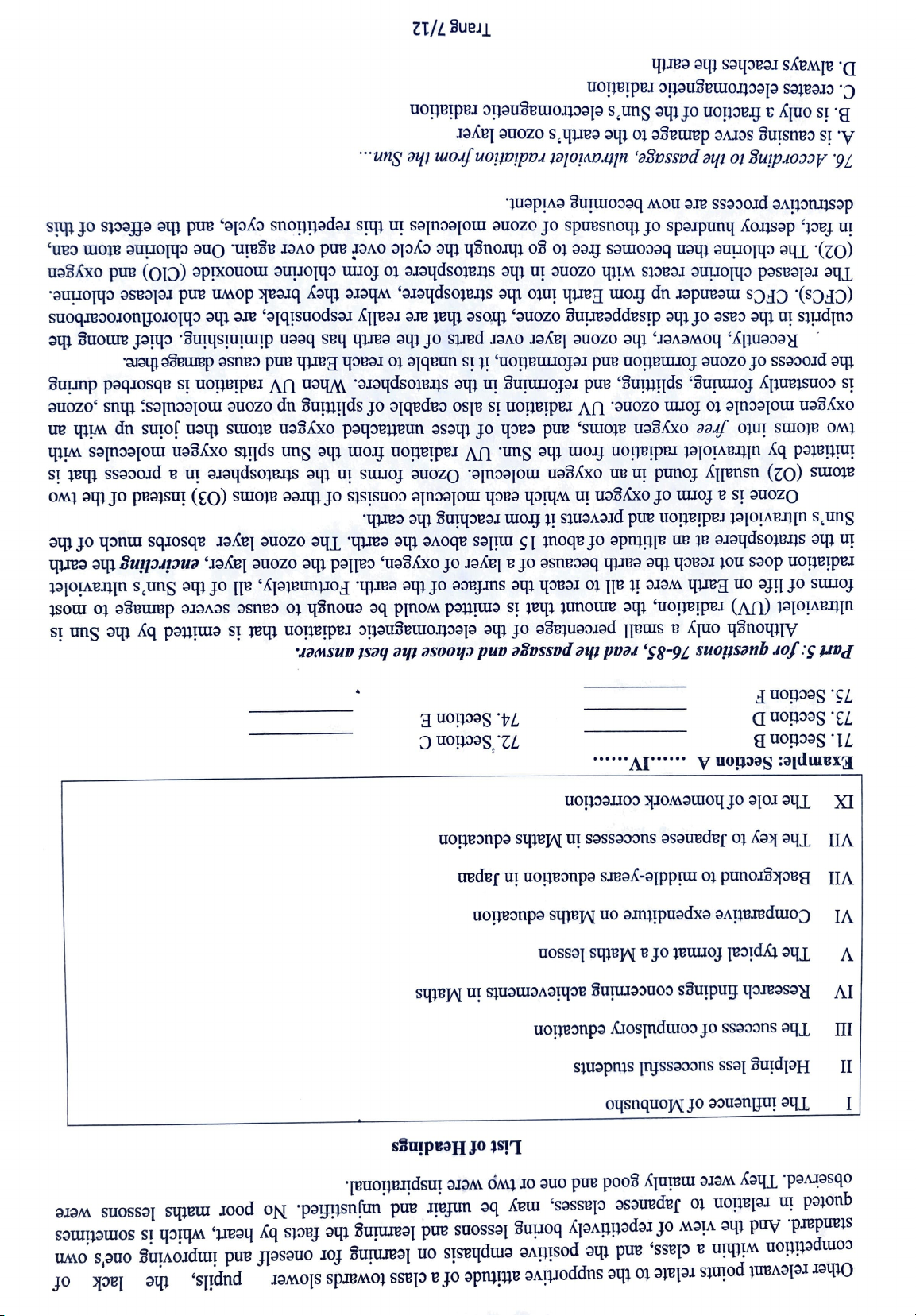

2: The chart below shows the Average Monthly Temperatures/or three

African

cities.

Summarize

the information by selecting

and

rep(!rting the main features,

and

make

comparisons where relevant.

You should write about 150 words.

Average

Monthly Temperatures for

Three

African

Cities

85

·

Africa

'-v"

i;ai

ro

·

""

80

.,

,:;

75

C

.,

.l:

.,

70

IL.

.,

.,

65

.,

e.

60

::,

55

1ii

a.

50

E

.,

....

L_:!e

Town,

South

Africa

45

I

40

·7

\

..

, .

.....

,,

................................

......

...

....

...

.... ·

..

..

/

....

.

Mombasa

\ ?a

J

F

M

A

M

J

J

A

s

0

N

D

····················· ································································································ ·

········

········ ······················································································································

.

······························································································································

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .................................................... .

Essay

writing

According to the new regulation which is to take effect in early November this year, Students in middle

and

high schools in Vietnam will be allowed to use their mobile phones in class

for

educational purposes.

Many people support this new regulation. Meanwhile, several others argue that it will negatively

affect student's concentration in their learning at schools

if

they are allowed to use mobile phones.

Write

an

essay

of

about 350 words to express your opinion with relevant details to support your

viewpoint.

·······································

..

··································· ........................................ .

..........

.

....

.

·························

..

········· ......................................................................................... .

Trang 10/12

Bấm Tải xuống để xem toàn bộ.