Preview text:

lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 Incentives Matter

The success or failure of an economic system often comes down to the incentives it provides.

Incentives are rewards or punishments that motivate particular choices. Many of the

shortcomings of command economies result from inadequate incentives for producers to

satisfy consumers’ needs. In market economies, producers are free to raise the price when

there is a shortage of a product and to keep the resulting profits. Profits provide an incentive

for producers to make more of the most-needed goods and services and thus to eliminate shortages. Incentives

Incentives are rewards or punishments that motivate particular choices.

In fact, economists tend to be skeptical of any attempt to change people’s behavior that

doesn’t change their incentives. For example, a plan that calls on manufacturers to voluntarily

reduce pollution is likely to be ineffective unless it is accompanied by incentives, such as tax

breaks or the avoidance of fines.

Property rights, which establish ownership and grant individuals the right to trade goods and

services with each other, create many of the incentives in market economies. Property rights

can apply to resources, goods, firms, and intellectual property, such as inventions and works

of art. With the right to own property comes the incentive to produce things of value, either to

keep, or to trade for things of even greater value. Ownership also creates an incentive to put

resources to their best possible use. Property rights to a lake, for example, give the owners an

incentive not to pollute that lake if its use for recreation, serenity, or sale has significant value. Property rights

Property rights establish ownership and grant individuals the right to trade goods and services with each other.

A model is any simplified version of reality used to better understand a real-life situation. But

how do we create a simplified representation of an economic situation? One possibility — an

economist’s equivalent of a wind tunnel — is to find or create a real but simplified economy.

For example, economists interested in the role of money have studied the system of exchange

that developed in World War II prison camps, in which cigarettes became a universally

accepted form of payment, even among prisoners who didn’t smoke. model

A model is a simplified representation used to better understand a real-life situation.

The workings of the economy can modeled on a computer. For example, when changes in tax

law are proposed, government officials use tax models — large mathematical computer

programs — to assess how the proposed changes would affect different groups of people.

Economists particularly like to create models with graphs and equations.

Models are important because their simplicity allows economists to focus on the influence of

only one change at a time. That is, they allow us to hold everything else constant and study

how one change affects the overall economic outcome. So when building economic models, it lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337

is important to make the other things equal assumption, which means that all other relevant

factors remain unchanged. Sometimes the Latin phrase ceteris paribus, which means “other things equal,” is used. other things equal assumption

The other things equal assumption means that all other relevant factors remain unchanged.

This is also known as the ceteris paribus assumption. lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 sunk cost

A sunk cost is a cost that has already been incurred and is nonrecoverable. A sunk cost should

be ignored in a decision about future actions. lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337 lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337

Budgets and Optimal Consumption

The principle of diminishing marginal utility explains why most people eventually reach a

limit, even at an all-you-can-eat buffet where the cost of another cookie is measured only in

future indigestion. Under ordinary circumstances, however, it costs some additional resources

to consume more of a good, and consumers must take that cost into account when making choices.

What do we mean by cost in this scenario? As always, the fundamental measure of cost is

opportunity cost. Because the amount of money a consumer can spend is limited, a decision

to consume more of one good is also a decision to consume less of some other good.

Budget Constraints and Budget Lines

Consider Sebastian, whose appetite is exclusively for cookies and tofu. (There’s no

accounting for tastes.) He has a weekly income of $20 and since, given his appetite, more of

either good is better than less, he spends all of it on cookies and tofu. We will assume that

cookies cost $4 per pound and tofu costs $2 per pound. What are his possible choices?

Whatever Sebastian chooses, we know that the cost of his consumption bundle cannot exceed

the amount of money he has to spend. That is,

Expenditure on cookies + Expenditure on tofu ≤ Total income

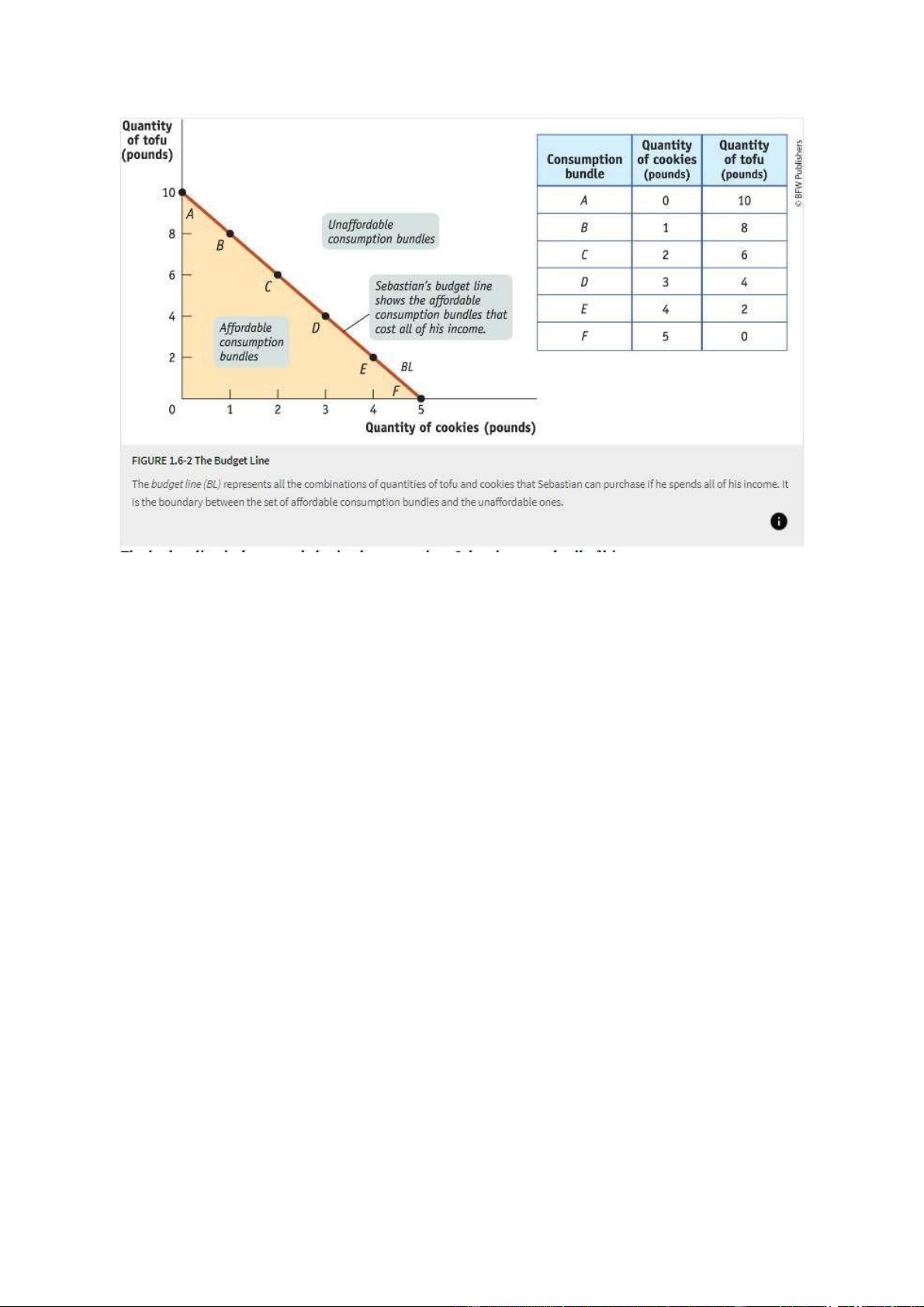

Figure 1.6-2 shows Sebastian’s consumption possibilities. The quantity of cookies in his

consumption bundle is measured on the horizontal axis and the quantity of tofu on the

vertical axis. The downward-sloping budget line (BL) shows all the consumption bundles

available to Sebastian when he spends all of his income. Every bundle on or inside this line

(the shaded area) is affordable; every bundle outside this line is unaffordable. As an example,

point C on the budget line represents 2 pounds of cookies and 6 pounds of tofu. Let’s verify

that it satisfies Sebastian budget constraint. The cost of bundle C is 6 pounds of tofu × $2 per

pound + 2 pounds of cookies × $4 per pound = $ 12 + $ 8 = $ 20. So bundle C does indeed

satisfy Sebastian’s budget constraint: it costs no more than his weekly income of $20. In fact,

bundle C costs exactly as much as Sebastian’s income. With a bit of arithmetic you can check

that all the other bundles along the budget line cost exactly $20. At the extremes, if Sebastian

spends all of his income on cookies (bundle F ), he can purchase 5 pounds of cookies; if he

spends all of his income on tofu (bundle A), he can purchase 10 pounds of tofu. budget line (BL)

A consumer’s budget line (BL) shows the consumption bundles available to a consumer who spends all of their income. lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337

The budget line is downward-sloping because when Sebastian spends all of his income, in

order to consume more pounds of cookies, he must consume fewer pounds of tofu. For

example, if he starts out consuming at point A and he wants more cookies, he must move to a

point further down, like B, where he has more cookies but less tofu. So when Sebastian is on

his budget line, the opportunity cost of consuming more pounds of cookies is consuming

fewer pounds of tofu, and vice versa.

Do we need to consider the other bundles in Sebastian’s consumption possibilities — the ones

that lie within the shaded region in Figure 1.6-2 bounded by the budget line? The answer, for

all practical situations, is no: as long as Sebastian doesn’t get satiated — that is, as long as his

marginal utility from consuming either good is always positive — and he doesn’t get any

utility from saving income rather than spending it, he will always choose to consume a

bundle that lies on his budget line.

Given Sebastian’s $20 per week budget, next we can consider the culinary dilemma of what

point on his budget line Sebastian will choose

The Optimal Consumption Bundle

Because Sebastian’s budget constrains him to a consumption bundle somewhere along the

budget line, a choice to consume a given quantity of cookies also determines his tofu

consumption, and vice versa. We want to find the consumption bundle — represented by a

point on the budget line — that maximizes Sebastian’s total utility. This bundle is Sebastian’s

optimal consumption bundle. optimal consumption bundle

A consumer’s optimal consumption bundle is the consumption bundle that maximizes the

consumer’s total utility given their budget constraint. lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337

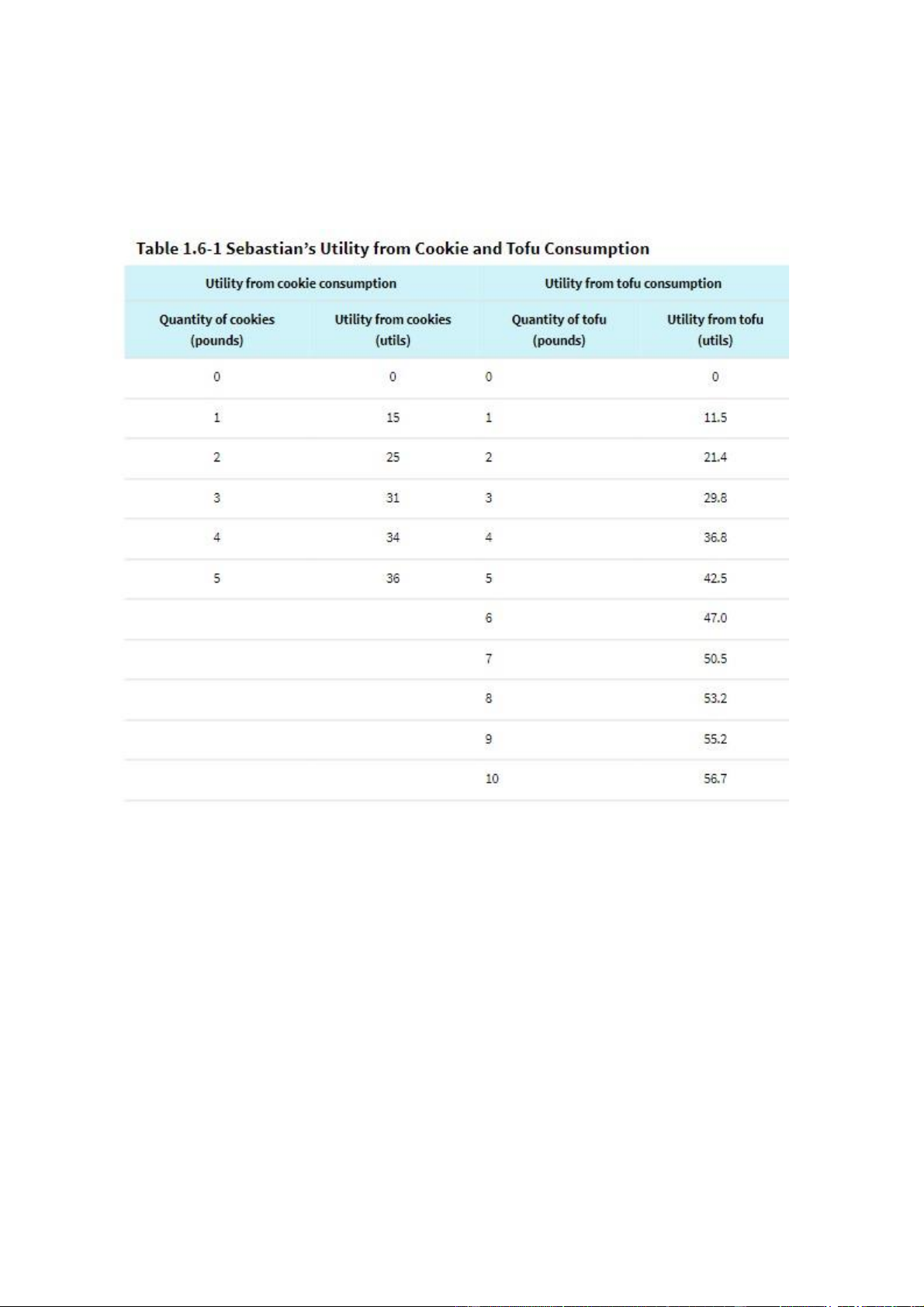

Table 1.6-1 shows hypothetical levels of utility Sebastian gets from consuming various

quantities of cookies and tofu, respectively. The table indicates that Sebastian has a healthy

appetite; the more of either good he consumes, the higher his utility. But because he has a

limited budget, he must make a trade-off: the more pounds of cookies he consumes, the fewer

pounds of tofu, and vice versa. That is, he must choose a point on his budget line.

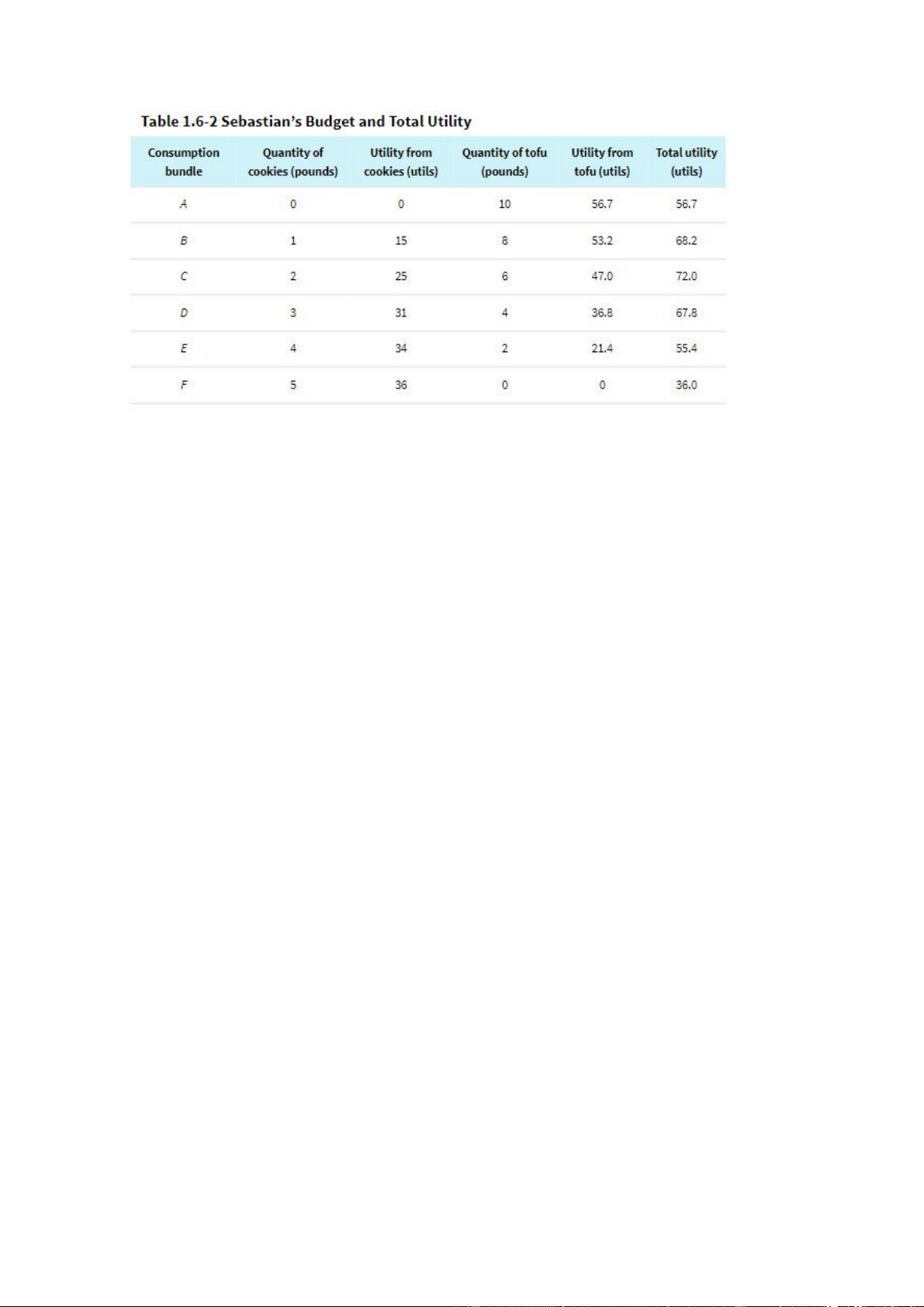

Table 1.6-2 shows how his total utility varies for the different consumption bundles along his

budget line. Each of six possible consumption bundles, A through F from Figure 1.6-2, is

given in the first column. The second column shows the level of cookie consumption

corresponding to each choice. The third column shows the utility Sebastian gets from

consuming those cookies. The fourth column shows the quantity of tofu Sebastian can afford

given the level of cookie consumption; this quantity goes down as his cookie consumption

goes up because he is sliding down the budget line. The fifth column shows the utility he gets

from consuming tofu. And the final column shows his total utility. In this example,

Sebastian’s total utility is the sum of the utility he gets from cookies and the utility he gets from tofu. lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337

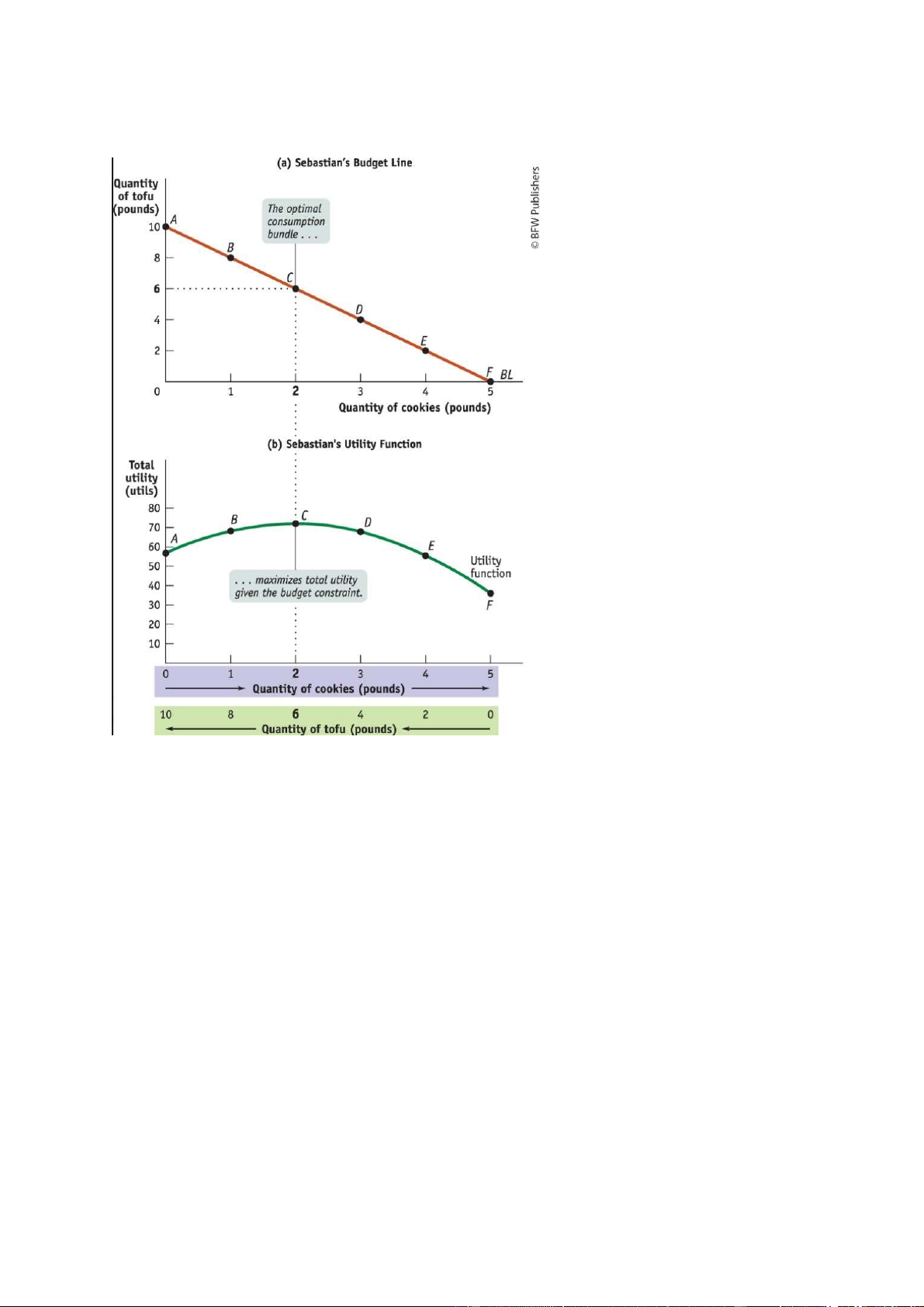

Figure 1.6-3 gives a visual representation of the data in Table 1.6-2. Panel (a) shows

Sebastian’s budget line, to remind us that a decision to consume more cookies is also a

decision to consume less tofu. Panel (b) then shows how his total utility depends on that

choice. The horizontal axis in panel (b) has two sets of labels: it shows both the quantity of

cookies, increasing from left to right, and the quantity of tofu, increasing from right to left.

The reason we can use the same axis to represent consumption of both goods is that Sebastian

is constrained by the budget line: the more pounds of cookies he consumes, the fewer pounds lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337

of tofu he can afford, and vice versa.

Panel (a) shows Sebastian’s budget line and his six possible consumption bundles. Panel (b)

shows how his total utility is affected by his consumption bundle, which must lie on his

budget line. The quantity of cookies is measured from left to right on the horizontal axis, and

the quantity of tofu is measured from right to left. As he consumes more cookies, due to his

fixed budget, he must consume less tofu. As a result, the quantity of tofu decreases as the

quantity of cookies increases. His total utility is maximized at bundle C, where he consumes

2 pounds of cookies and 6 pounds of tofu. This is Sebastian’s optimal consumption bundle.

Spending the Marginal Dollar

As we’ve just seen, we can find Sebastian’s optimal consumption choice by finding the total

utility he receives from each consumption bundle on his budget line and then choosing the

bundle that maximizes total utility. But we can use marginal analysis instead, which leads to

some useful guidelines for how much to buy. How do we do this? By looking at the choice of

an optimal consumption bundle as a problem of how much to spend on each good. Using

marginal analysis, this becomes a question of how to spend the marginal dollar — how to

allocate an additional dollar between cookies and tofu in a way that maximizes utility.

Our first step in applying marginal analysis is to ask if Sebastian is made better off by

spending an additional dollar on either good; and if so, by how much is he better off. To lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337

answer this question, we must calculate the marginal utility per dollar spent on either cookies

or tofu — how much additional utility Sebastian gets from spending an additional dollar on either good. lOMoAR cPSD| 47882337

Marginal Utility per Dollar

We’ve already introduced the concept of marginal utility, the additional utility a consumer

gets from consuming one more unit of a good or service; now let’s use this concept to derive

the related measure of marginal utility per dollar.

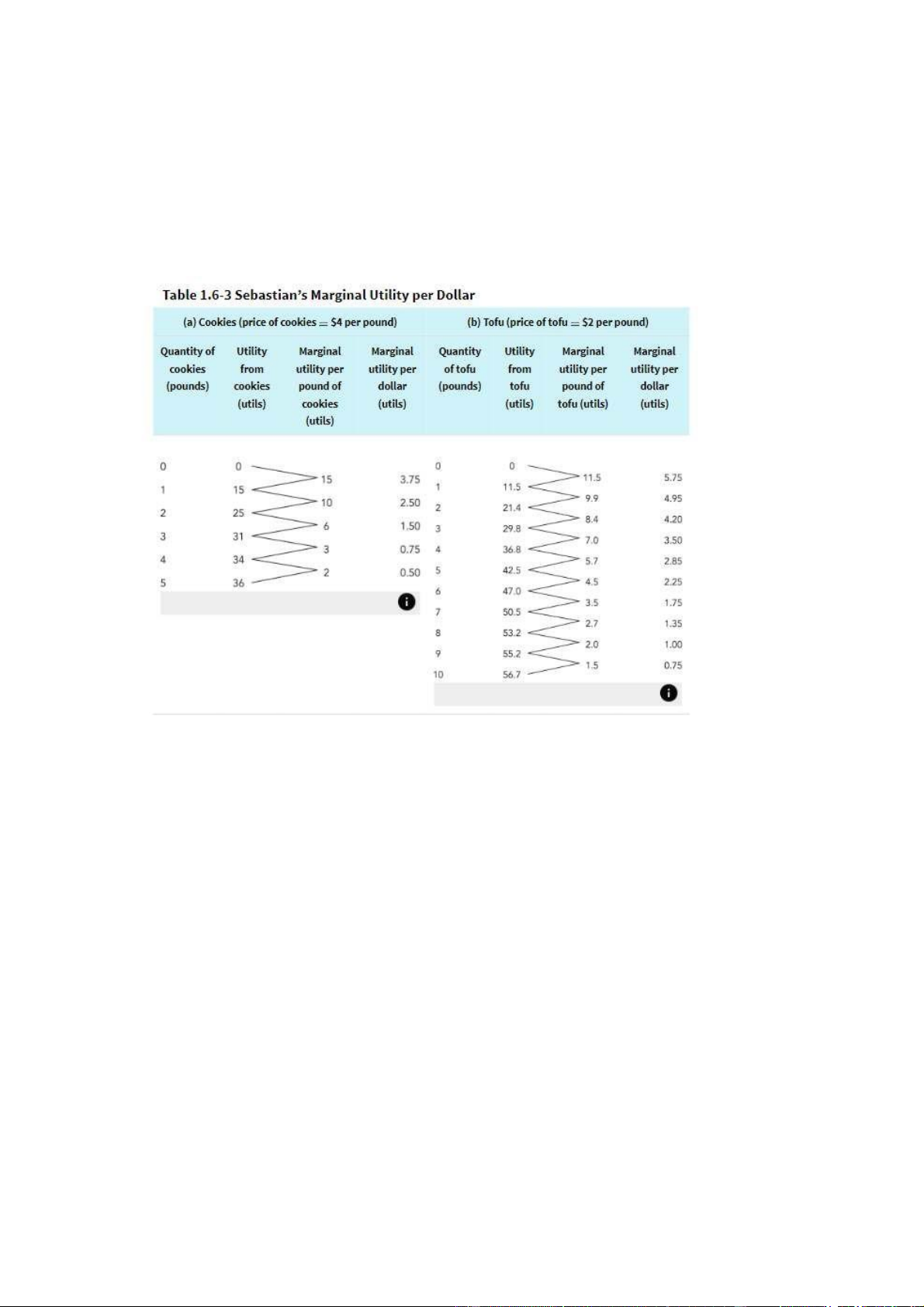

Table 1.6-3 shows how to calculate the marginal utility per dollar spent on cookies and tofu, respectively.

In panel (a) of the table, the first column shows different possible amounts of cookie

consumption. The second column shows the utility Sebastian derives from each amount of

cookie consumption; the third column shows the marginal utility, the increase in utility

Sebastian gets from consuming an additional pound of cookies. Panel (b) provides the same

information for tofu. The next step is to derive marginal utility per dollar for each good. To do

this, we just divide the marginal utility of the good by its price in dollars.

It’s important to divide marginal utility by price because gains in utility from the two goods

have differing prices. Consider what happens if Sebastian increases his cookie consumption

from 2 pounds to 3 pounds. This raises his total utility by 6 utils. But he must spend $4 for

that additional 6 utils, so the increase in his utility per additional dollar spent on cookies is 6

utils/ $4 = 1.5 utils. Similarly, if he increases his cookie consumption from 3 pounds to 4

pounds, his marginal utility is 3 utils but his marginal utility per dollar is 3utils/$ 4 = 0.75 utils.

Notice in the last two columns of panel (a) that, because of diminishing marginal utility,

Sebastian’s marginal utility per pound of cookies falls as the quantity of cookies he consumes

rises. As a result, his marginal utility per dollar spent on cookies also falls as the quantity of

cookies he consumes rises. Similarly, the last column of panel (b) shows how his marginal

utility per dollar spent on tofu depends on the quantity of tofu he consumes. Again, marginal