Preview text:

Chapter 4 Organization and Functioning of Securities Markets*

After you read this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions:

➤ What is the purpose and function of a market?

➤ What are the characteristics that determine the quality of a market?

➤ What is the difference between a primary and secondary capital market and how do these markets support each other?

➤ What are the national exchanges and how are the major securities markets around the world

becoming linked (what is meant by “passing the book”)?

➤ What are regional stock exchanges and over-the-counter (OTC) markets?

➤ What are the alternative market-making arrangements available on the exchanges and the OTC market?

➤ What are the major types of orders available to investors and market makers?

➤ What are the major functions of the specialist on the NYSE and how does the specialist

differ from the central market maker on other exchanges?

➤ What are the significant changes in markets around the world during the past 15 years?

➤ What are the major changes in world capital markets expected over the next decade?

The stock market, the Dow Jones Industrials, and the bond market are part of our everyday

experience. Each evening on the television news broadcasts, we find out how stocks and bonds

fared; each morning we read in our daily newspapers about expectations for a market rally or

decline. Yet most people have an imperfect understanding of how domestic and world capital

markets actually function. To be a successful investor in a global environment, you must know

what financial markets are available around the world and how they operate.

In Chapter 1, we considered why individuals invest and what determines their required rate

of return on investments. In Chapter 2, we discussed the life cycle for investors and the alterna-

tive asset allocation decisions by investors during different phases. In Chapter 3, we learned

about the numerous alternative investments available and why we should diversify with securi-

ties from around the world. This chapter takes a broad view of securities markets and provides a

detailed discussion of how major stock markets function. We conclude with a consideration of

how global securities markets are changing.

We begin with a discussion of securities markets and the characteristics of a good market.

Two components of the capital markets are described: primary and secondary. Our main empha-

sis in this chapter is on the secondary stock market. We consider the national stock exchanges

around the world and how these markets, separated by geography and by time zones, are becom-

ing linked into a 24-hour market. We also consider regional stock markets and the over-the-

counter markets and provide a detailed analysis of how alternative exchange markets operate.

*The authors acknowledge helpful comments on this chapter from Robert Battalio and Paul Schultz of the University of Notre Dame. 105

106 CHAPTER 4 ORGANIZATION AND FUNCTIONING OF SECURITIES MARKETS

The final section considers numerous historical changes in financial markets, additional current

changes, and significant future changes expected. These numerous changes in our securities mar-

kets will have a profound effect on what investments are available to you from around the world and how you buy and sell them. WHAT IS A MARKET?

This section provides the necessary background for understanding different securities markets

around the world and the changes that are occurring. The first part considers the general concept

of a market and its function. The second part describes the characteristics that determine the

quality of a particular market. The third part of the section describes primary and secondary cap-

ital markets and how they interact and depend on one another.

A market is the means through which buyers and sellers are brought together to aid in the

transfer of goods and/or services. Several aspects of this general definition seem worthy of

emphasis. First, a market need not have a physical location. It is only necessary that the buyers

and sellers can communicate regarding the relevant aspects of the transaction.

Second, the market does not necessarily own the goods or services involved. For a good mar-

ket, ownership is not involved; the important criterion is the smooth, cheap transfer of goods and

services. In most financial markets, those who establish and administer the market do not own

the assets but simply provide a physical location or an electronic system that allows potential

buyers and sellers to interact. They help the market function by providing information and facil-

ities to aid in the transfer of ownership.

Finally, a market can deal in any variety of goods and services. For any commodity or service

with a diverse clientele, a market should evolve to aid in the transfer of that commodity or ser-

vice. Both buyers and sellers will benefit from the existence of a smooth functioning market.

Characteristics of Throughout this book, we will discuss markets for different investments, such as stocks, bonds, a Good Market

options, and futures, in the United States and throughout the world. We will refer to these mar-

kets using various terms of quality, such as strong, active, liquid, or illiquid. There are many

financial markets, but they are not all equal—some are active and liquid; others are relatively

illiquid and inefficient in their operations. To appreciate these discussions, you should be aware

of the following characteristics that investors look for when evaluating the quality of a market.

One enters a market to buy or sell a good or service quickly at a price justified by the pre-

vailing supply and demand. To determine the appropriate price, participants must have timely

and accurate information on the volume and prices of past transactions and on all currently

outstanding bids and offers. Therefore, one attribute of a good market is timely and accurate information.

Another prime requirement is liquidity, the ability to buy or sell an asset quickly and at a

known price—that is, a price not substantially different from the prices for prior transactions,

assuming no new information is available. An asset’s likelihood of being sold quickly, sometimes

referred to as its marketability, is a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition for liquidity. The

expected price should also be fairly certain, based on the recent history of transaction prices and current bid-ask quotes.1

1For a more formal discussion of liquidity, see Puneet Handa and Robert A. Schwartz, “How Best to Supply Liquidity to

a Securities Market,” Journal of Portfolio Management 22, no. 2 (Winter 1996): 44–51. For a recent set of articles that

consider liquidity and all components of trade execution, see Best Execution and Portfolio Performance (Charlottesville,

Va.: Association for Investment Management and Research, 2000). WHAT IS A MARKET? 107

A component of liquidity is price continuit ,

y which means that prices do not change much

from one transaction to the next unless substantial new information becomes available. Suppose

no new information is forthcoming and the last transaction was at a price of $20; if the next trade

were at $20.05, the market would be considered reasonably continuous.2 A continuous market

without large price changes between trades is a characteristic of a liquid market.

A market with price continuity requires depth, which means that numerous potential buyers

and sellers must be willing to trade at prices above and below the current market price. These

buyers and sellers enter the market in response to changes in supply and demand or both and

thereby prevent drastic price changes. In summary, liquidity requires marketability and price

continuity, which, in turn, requires depth.

Another factor contributing to a good market is the transaction cost. Lower costs (as a per-

cent of the value of the trade) make for a more efficient market. An individual comparing the cost

of a transaction between markets would choose a market that charges 2 percent of the value of

the trade compared with one that charges 5 percent. Most microeconomic textbooks define an

efficient market as one in which the cost of the transaction is minimal. This attribute is referred

to as internal efficiency.

Finally, a buyer or seller wants the prevailing market price to adequately reflect all the infor-

mation available regarding supply and demand factors in the market. If such conditions change

as a result of new information, the price should change accordingly. Therefore, participants want

prices to adjust quickly to new information regarding supply or demand, which means that prices

reflect all available information about the asset. This attribute is referred to as external effi-

ciency or informational efficiency. This attribute is discussed extensively in Chapter 6.

In summary, a good market for goods and services has the following characteristics:

1. Timely and accurate information is available on the price and volume of past transactions

and the prevailing bid and ask prices.

2. It is liquid, meaning an asset can be bought or sold quickly at a price close to the prices

for previous transactions (has price continuity), assuming no new information has been

received. In turn, price continuity requires depth.

3. Transactions entail low costs, including the cost of reaching the market, the actual broker-

age costs, and the cost of transferring the asset.

4. Prices rapidly adjust to new information; thus, the prevailing price is fair because it

reflects all available information regarding the asset.

Decimal Pricing Common stocks in the United States have always been quoted in fractions prior to the change in

late 2000. Specifically, prior to 1997, they were quoted in eighths (e.g., 1/8, 2/8, . . . 7/8), with

each eighth equal to $0.125. This was modified in 1997 when the fractions for most stocks went

to sixteenths (e.g., 1/16, 2/16, . . . 15/16) equal to $0.0625. The Securities and Exchange

Commission (SEC) has been pushing for a change to decimal pricing for a number of years and

eventually set a deadline for the early part of 2001. The NYSE started the transition with seven

stocks as of August 28, 2000, included an additional 52 stocks on September 25, and added 94

securities effective December 4, 2000. The final deadline for all stocks on the NYSE and the

AMEX to go “decimal” was April 9, 2001. The Nasdaq market deferred the change until late April 2001.

2You should be aware that common stocks are currently sold in decimals (dollars and cents), which is a significant change

from the pre-2000 period when they were priced in eighths and sixteenths. This change to decimals is discussed at the end of this subsection.

108 CHAPTER 4 ORGANIZATION AND FUNCTIONING OF SECURITIES MARKETS

The espoused reasons for the change to decimal pricing were threefold. The first reason was

the ease with which investors could understand the prices and compare them. Second, decimal

pricing was expected to save investors money since it would almost certainly reduce the size of

the bid-ask spread from a minimum of 6.25 cents when prices are quoted in 16ths to possibly

1 cent when prices are in decimals. Of course, this is also why many brokers and investment

firms were against the change since the bid-ask spread is the price of liquidity for the investor

and the compensation to the dealer. Third, this change is also expected to make the U.S. markets

more competitive on a global basis since other countries already price on a comparable basis and,

as noted, this would cause our transaction costs to be lower.

Organization of Before discussing the specific operation of the securities market, you need to understand its over- the Securities

all organization. The principal distinction is between primary markets, where new securities

Market are sold, and secondary markets, where outstanding securities are bought and sold. Each of

these markets is further divided based on the economic unit that issued the security. The follow-

ing discussion considers each of these major segments of the securities market with an empha-

sis on the individuals involved and the functions they perform. PRIMARY CAPITAL MARKETS

The primary market is where new issues of bonds, preferred stock, or common stock are sold by

government units, municipalities, or companies to acquire new capital.3 Government Bond

All U.S. government bond issues are subdivided into three segments based on their original Issues

maturities. Treasury bills are negotiable, non-interest-bearing securities with original maturities

of one year or less. Treasury notes have original maturities of 2 to 10 years. Finally, Treasury

bonds have original maturities of more than 10 years.

To sell bills, notes, and bonds, the Treasury relies on Federal Reserve System auctions. (The

bidding process and pricing are discussed in detail in Chapter 18.)

Municipal Bond New municipal bond issues are sold by one of three methods: competitive bid, negotiation, or Issues

private placement. Competitive bid sales typically involve sealed bids. The bond issue is sold

to the bidding syndicate of underwriters that submits the bid with the lowest interest cost in

accordance with the stipulations set forth by the issuer. Negotiated sales involve contractual

arrangements between underwriters and issuers wherein the underwriter helps the issuer prepare

the bond issue and set the price and has the exclusive right to sell the issue. Private placements

involve the sale of a bond issue by the issuer directly to an investor or a small group of investors (usually institutions).

Note that two of the three methods require an underwriting function. Specifically, in a com-

petitive bid or a negotiated transaction, the investment banker typically underwrites the issue,

which means the investment firm purchases the entire issue at a specified price, relieving the

issuer from the risk and responsibility of selling and distributing the bonds. Subsequently, the

underwriter sells the issue to the investing public. For municipal bonds, this underwriting func-

tion is performed by both investment banking firms and commercial banks.

3 For an excellent set of studies related to the primary market, see Michael C. Jensen and Clifford W. Smith, Jr., eds.,

“Symposium on Investment Banking and the Capital Acquisition Process,” Journal of Financial Economics 15, no. 1/2 (January–February 1986).

PRIMARY CAPITAL MARKETS 109

The underwriting function can involve three services: origination, risk bearing, and distribu-

tion. Origination involves the design of the bond issue and initial planning. To fulfill the risk-

bearing function, the underwriter acquires the total issue at a price dictated by the competitive

bid or through negotiation and accepts the responsibility and risk of reselling it for more than the

purchase price. Distribution means selling it to investors, typically with the help of a selling syn-

dicate that includes other investment banking firms and/or commercial banks.

In a negotiated bid, the underwriter will carry out all three services. In a competitive bid, the

issuer specifies the amount, maturities, coupons, and call features of the issue and the compet-

ing syndicates submit a bid for the entire issue that reflects the yields they estimate for the bonds.

The issuer may have received advice from an investment firm on the desirable characteristics for

a forthcoming issue, but this advice would have been on a fee basis and would not necessarily

involve the ultimate underwriter who is responsible for risk bearing and distribution. Finally, a

private placement involves no risk bearing, but an investment banker could assist in locating

potential buyers and negotiating the characteristics of the issue.

Corporate Bond Corporate bond issues are almost always sold through a negotiated arrangement with an invest-

Issues ment banking firm that maintains a relationship with the issuing firm. In a global capital market

that involves an explosion of new instruments, the origination function, which involves the

design of the security in terms of characteristics and currency, is becoming more important

because the corporate chief financial officer (CFO) will probably not be completely familiar with

the availability and issuing requirements of many new instruments and the alternative capital

markets around the world. Investment banking firms compete for underwriting business by cre-

ating new instruments that appeal to existing investors and by advising issuers regarding desir-

able countries and currencies. As a result, the expertise of the investment banker can help reduce

the issuer’s cost of new capital.

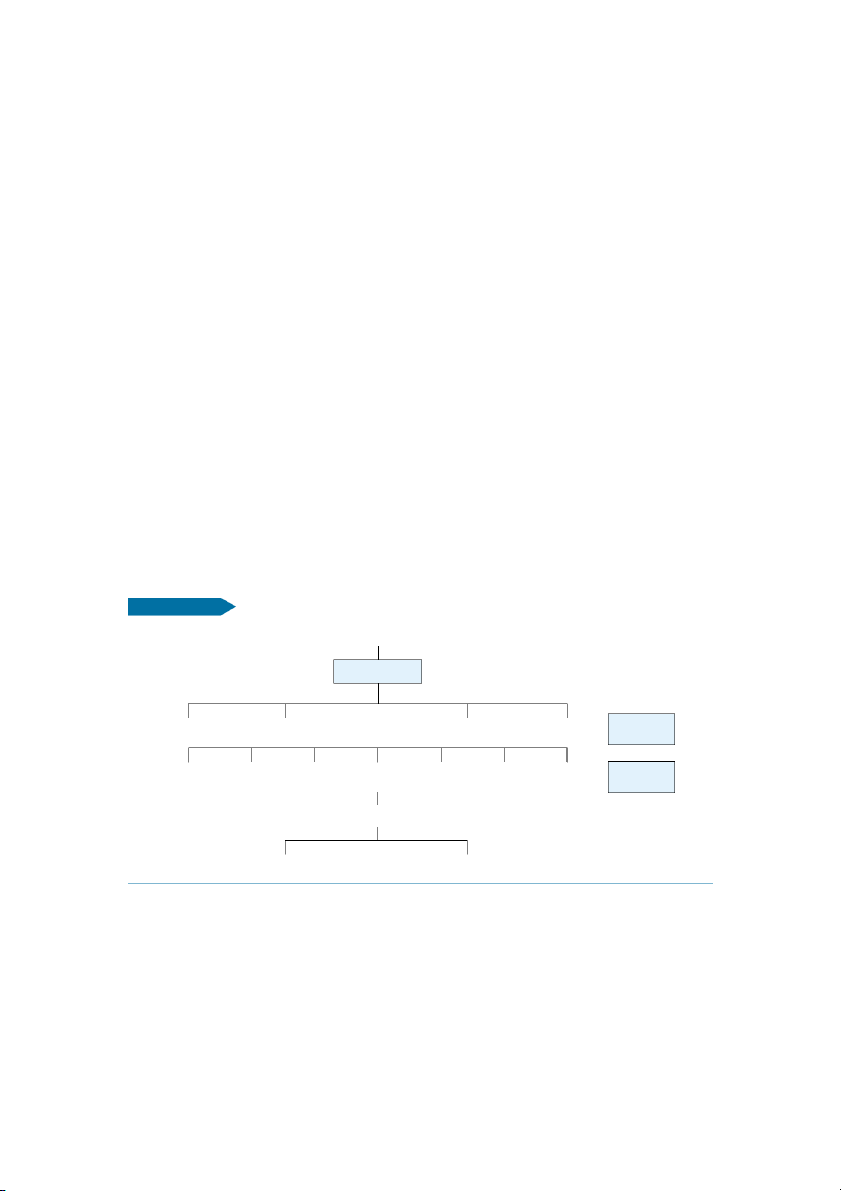

Once a stock or bond issue is specified, the underwriter will put together an underwriting syn-

dicate of other major underwriters and a selling group of smaller firms for its distribution as shown in Exhibit 4.1. EXHIBIT 4.1

THE UNDERWRITING ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE Issuing Firm Lead Underwriter Investment Investment Investment Investment Underwriting Banker A Banker B Banker C Banker D Group Investment Investment Investment Investment Investment Investment Investment Selling Firm A Firm B Firm C Firm D Firm E Firm F Firm G Group Investors Institutions Individuals

110 CHAPTER 4 ORGANIZATION AND FUNCTIONING OF SECURITIES MARKETS

Corporate Stock In addition to the ability to issue fixed-income securities to get new capital, corporations can also Issues

issue equity securities—generally common stock. For corporations, new stock issues are typi-

cally divided into two groups: (1) seasoned equity issues and (2) initial public offerings (IPOs).

Seasoned equity issues are new shares offered by firms that already have stock outstanding.

An example would be General Electric, which is a large, well-regarded firm that has had public

stock trading on the NYSE for over 50 years. If General Electric decided that it needed new cap-

ital, it could sell additional shares of its common stock to the public at a price very close to the

current price of the firm’s stock.

Initial public offerings (IPOs) involve a firm selling its common stock to the public for the

first time. At the time of an IPO offering, there is no existing public market for the stock, that is,

the company has been closely held. An example would be an IPO by Polo Ralph Lauren in 1997,

at $26 per share. The company is a leading manufacturer and distributor of men’s clothing. The

purpose of the offering was to get additional capital to expand its operations.

New issues (seasoned or IPOs) are typically underwritten by investment bankers, who acquire

the total issue from the company and sell the securities to interested investors. The underwriter

gives advice to the corporation on the general characteristics of the issue, its pricing, and the tim-

ing of the offering. The underwriter also accepts the risk of selling the new issue after acquiring it from the corporation.4

Relationships with Investment Bankers The underwriting of corporate issues typically

takes one of three forms: negotiated, competitive bids, or best-efforts arrangements. As noted,

negotiated underwritings are the most common, and the procedure is the same as for municipal issues.

A corporation may also specify the type of securities to be offered (common stock, preferred

stock, or bonds) and then solicit competitive bids from investment banking firms. This is rare for

industrial firms but is typical for utilities, which may be required by law to sell the issue via a

competitive bid. Although competitive bids typically reduce the cost of an issue, it also means

that the investment banker gives less advice but still accepts the risk-bearing function by under-

writing the issue and fulfills the distribution function.

Alternatively, an investment banker can agree to support an issue and sell it on a best-efforts

basis. This is usually done with speculative new issues. In this arrangement, the investment

banker does not underwrite the issue because it does not buy any securities. The stock is owned

by the company, and the investment banker acts as a broker to sell whatever it can at a stipulated

price. The investment banker earns a lower commission on such an issue than on an underwrit- ten issue.

Introduction of Rule 415 The typical practice of negotiated arrangements involving

numerous investment banking firms in syndicates and selling groups has changed with the intro-

duction of Rule 415, which allows large firms to register security issues and sell them piecemeal

during the following two years. These issues are referred to as shelf registrations because, after

they are registered, the issues lie on the shelf and can be taken down and sold on short notice

whenever it suits the issuing firm. As an example, General Electric could register an issue of

5 million shares of common stock during 2003 and sell a million shares in early 2003, another

million shares late in 2003, 2 million shares in early 2004, and the rest in late 2004.

Each offering can be made with little notice or paperwork by one underwriter or several. In

fact, because relatively few shares may be involved, the lead underwriter often handles the whole

4For an extended discussion of the underwriting process, see Richard A. Brealey and Stewart C. Myers, Principles of

Corporate Finance, 7th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001), Chapter 15.

SECONDARY FINANCIAL MARKETS 111

deal without a syndicate or uses only one or two other firms. This arrangement has benefited large

corporations because it provides great flexibility, reduces registration fees and expenses, and

allows firms issuing securities to request competitive bids from several investment banking firms.

On the other hand, some observers fear that shelf registrations do not allow investors enough

time to examine the current status of the firm issuing the securities. Also, the follow-up offerings

reduce the participation of small underwriters because the underwriting syndicates are smaller

and selling groups are almost nonexistent. Shelf registrations have typically been used for the

sale of straight debentures rather than common stock or convertible issues.5

Private Placements Rather than a public sale using one of these arrangements, primary offerings can be sold pri- and Rule 144A

vately. In such an arrangement, referred to as a private placement, the firm designs an issue with

the assistance of an investment banker and sells it to a small group of institutions. The firm

enjoys lower issuing costs because it does not need to prepare the extensive registration state-

ment required for a public offering. The institution that buys the issue typically benefits because

the issuing firm passes some of these cost savings on to the investor as a higher return. In fact,

the institution should require a higher return because of the absence of any secondary market for

these securities, which implies higher liquidity risk.

The private placement market changed dramatically when Rule 144A was introduced by the

SEC. This rule allows corporations—including non-U.S. firms—to place securities privately

with large, sophisticated institutional investors without extensive registration documents. It also

allows these securities to be subsequently traded among these large, sophisticated investors

(those with assets in excess of $100 million). The SEC intends to provide more financing alter-

natives for U.S. and non-U.S. firms and possibly increase the number, size, and liquidity of pri-

vate placements.6 Presently, a large percent of high-yield bonds are issued as 144A issues.

SECONDARY FINANCIAL MARKETS

In this section, we consider the purpose and importance of secondary markets and provide an

overview of the secondary markets for bonds, financial futures, and stocks. Next, we consider

national stock markets around the world. Finally, we discuss regional and over-the-counter stock

markets and provide a detailed presentation on the functioning of stock exchanges.

Secondary markets permit trading in outstanding issues; that is, stocks or bonds already sold

to the public are traded between current and potential owners. The proceeds from a sale in the

secondary market do not go to the issuing unit (the government, municipality, or company) but,

rather, to the current owner of the security.

Why Secondary Before discussing the various segments of the secondary market, we must consider its overall

Markets Are importance. Because the secondary market involves the trading of securities initially sold in the Important

primary market, it provides liquidity to the individuals who acquired these securities. After

acquiring securities in the primary market, investors want the ability to sell them again to acquire

other securities, buy a house, or go on a vacation. The primary market benefits greatly from the

liquidity provided by the secondary market because investors would hesitate to acquire securities

5For further discussion of Rule 415, see Robert J. Rogowski and Eric H. Sorensen, “Deregulation in Investment Bank-

ing: Shelf Registration, Structure and Performance,” Financial Management 14, no. 1 (Spring 1985): 5–15.

6For a discussion of some reactions to Rule 144A, see John W. Milligan, “Two Cheers for 144A,” Institutional Investor

24, no. 9 (July 1990): 117–119; and Sara Hanks, “SEC Ruling Creates a New Market,” The Wall Street Journal, 16 May 1990, A12.

112 CHAPTER 4 ORGANIZATION AND FUNCTIONING OF SECURITIES MARKETS

in the primary market if they thought they could not subsequently sell them in the secondary

market. That is, without an active secondary market, potential issuers of stocks or bonds in the

primary market would have to provide a much higher rate of return to compensate investors for

the substantial liquidity risk.

Secondary markets are also important to those selling seasoned securities because the pre-

vailing market price of the securities is determined by transactions in the secondary market. New

issues of outstanding stocks or bonds to be sold in the primary market are based on prices and

yields in the secondary market.7 Even forthcoming IPOs are priced based on the prices and val-

ues of comparable stocks or bonds in the public secondary market.

Secondary Bond The secondary market for bonds distinguishes among those issued by the federal government,

Markets municipalities, or corporations.

Secondary Markets for U.S. Government and Municipal Bonds U.S. government

bonds are traded by bond dealers that specialize in either Treasury bonds or agency bonds. Trea-

sury issues are bought or sold through a set of 35 primary dealers, including large banks in New

York and Chicago and some of the large investment banking firms (for example, Merrill Lynch,

Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley). These institutions and other firms also make markets for gov-

ernment agency issues, but there is no formal set of dealers for agency securities.

The major market makers in the secondary municipal bond market are banks and investment

firms. Banks are active in municipal bond trading and underwriting of general obligation issues

since they invest heavily in these securities. Also, many large investment firms have municipal

bond departments that underwrite and trade these issues.

Secondary Corporate Bond Markets Historically, the secondary market for corporate

bonds included two major segments: security exchanges and an over-the-counter (OTC) market.

The major exchange for corporate bonds was the NYSE Fixed-Income Market where about

10 percent of the trading took place. In contrast, about 90 percent of trading, including all large

transactions, took place on the over-the-counter market. This mix of trading changed in early

2001 when the NYSE announced that it was shutting down its Automated Bond System (ABS),

which had been a fully automated trading and information system for small bond trades—that

is, the exchange market for bonds was considered the “odd-lot” bond market. As a result, cur-

rently all corporate bonds are traded over the counter by dealers who buy and sell for their own accounts.

The major bond dealers are the large investment banking firms that underwrite the issues such

as Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs, Salomon Brothers, Lehman Brothers, and Morgan Stanley.

Because of the limited trading in corporate bonds compared to the fairly active trading in gov-

ernment bonds, corporate bond dealers do not carry extensive inventories of specific issues.

Instead, they hold a limited number of bonds desired by their clients and, when someone wants

to do a trade, they work more like brokers than dealers.

Financial Futures In addition to the market for the bonds, a market has developed for futures contracts related to

these bonds. These contracts allow the holder to buy or sell a specified amount of a given bond

issue at a stipulated price. The two major futures exchanges are the Chicago Board of Trade

7In the literature on market microstructure, it is noted that the secondary markets also have an effect on market efficiency,

the volatility of security prices, and the serial correlation in security returns. In this regard, see F. D. Foster and

S. Viswanathan, “The Effects of Public Information and Competition on Trading Volume and Price Volatility,” Review of

Financial Studies 6, no. 1 (spring 1993): 23–56; C. N. Jones, G. Kaul, and M. L. Lipson, “Information, Trading and

Volatility,” Journal of Financial Economics 36, no. 1 (August 1994): 127–154.

SECONDARY FINANCIAL MARKETS 113

(CBOT) and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME). These futures contracts and the futures

market are discussed in Chapter 21.

Secondary Equity The secondary equity market is usually been broken down into three major segments: (1) the

Markets major national stock exchanges, including the New York, the Tokyo, and the London stock

exchanges; (2) regional stock exchanges in such cities as Chicago, San Francisco, Boston, Osaka

and Nagoya in Japan, and Dublin in Ireland; and (3) the over-the-counter (OTC) market, which

involves trading in stocks not listed on an organized exchange. These segments differ in impor- tance in different countries.

Securities Exchanges The first two segments, referred to as listed securities exchanges,

differ only in size and geographic emphasis. Both are composed of formal organizations with

specific members and specific securities (stocks or bonds) that have qualified for listing.

Although the exchanges typically consider similar factors when evaluating firms that apply for

listing, the level of requirement differs (the national exchanges have more stringent require-

ments). Also, the prices of securities listed on alternative stock exchanges are determined using

several different trading (pricing) systems that will be discussed in the next subsection.

Alternative Trading Systems Although stock exchanges are similar in that only qualified

stocks can be traded by individuals who are members of the exchange, they can differ in their

trading systems. There are two major trading systems, and an exchange can use one of these or

a combination of them. One is a pure auction market, in which interested buyers and sellers sub-

mit bid and ask prices for a given stock to a central location where the orders are matched by a

broker who does not own the stock but who acts as a facilitating agent. Participants refer to this

system as price-driven because shares of stock are sold to the investor with the highest bid price

and bought from the seller with the lowest offering price. Advocates of the auction system argue

for a very centralized market that ideally will include all the buyers and sellers of the stock.

The other major trading system is a dealer market where individual dealers provide liquidity

for investors by buying and selling the shares of stock for themselves. Ideally, with this system

there will be numerous dealers who will compete against each other to provide the highest bid

prices when you are selling and the lowest asking price when you are buying stock. When we

discuss the various exchanges, we will indicate the trading system used.

Call versus Continuous Markets Beyond the alternative trading systems for equities, the

operation of exchanges can differ in terms of when and how the stocks are traded.

In call markets, trading for individual stocks takes place at specified times. The intent is to

gather all the bids and asks for the stock and attempt to arrive at a single price where the quan-

tity demanded is as close as possible to the quantity supplied. Call markets are generally used

during the early stages of development of an exchange when there are few stocks listed or a small

number of active investors/traders. If you envision an exchange with only a few stocks listed and

a few traders, you would call the roll of stocks and ask for interest in one stock at a time. After

determining all the available buy and sell orders, exchange officials attempt to arrive at a single

price that will satisfy most of the orders, and all orders are transacted at this one price.

Notably, call markets also are used at the opening for stocks on the NYSE if there is an

overnight buildup of buy and sell orders, in which case the opening price can differ from the

prior day’s closing price. Also, this concept is used if trading is suspended during the day

because of some significant new information. In either case, the specialist or market maker

would attempt to derive a new equilibrium price using a call-market approach that would reflect

the imbalance and take care of most of the orders. For example, assume a stock had been trad-

ing at about $42 per share and some significant, new, positive information was released overnight

or during the day. If it was overnight, it would affect the opening; if it happened during the day,

114 CHAPTER 4 ORGANIZATION AND FUNCTIONING OF SECURITIES MARKETS

it would affect the price established after trading was suspended. If the buy orders were three or

four times as numerous as the sell orders, the price based on the call market might be $44, which

is the specialists’ estimate of a new equilibrium price that reflects the supply-demand caused by

the new information. Several studies have shown that this temporary use of the call-market

mechanism contributes to a more orderly market and less volatility in such instances.

In a continuous market, trades occur at any time the market is open. Stocks in this continu-

ous market are priced either by auction or by dealers. If it is a dealer market, dealers are willing

to make a market in the stock, which means that they are willing to buy or sell for their own

account at a specified bid and ask price. If it is an auction market, enough buyers and sellers are

trading to allow the market to be continuous; that is, when you come to buy stock, there is

another investor available and willing to sell stock. A compromise between a pure dealer market

and a pure auction market is a combination structure wherein the market is basically an auction

market, but there exists an intermediary who is willing to act as a dealer if the pure auction mar-

ket does not have enough activity. These intermediaries who act as brokers and dealers provide

temporary liquidity to ensure that the market will be liquid as well as continuous.

An appendix at the end of this chapter contains two exhibits that list the characteristics of

stock exchanges around the world and indicate whether each of the exchanges provides a con-

tinuous market, a call-market mechanism, or a mixture of the two. Notably, although many

exchanges are considered continuous, they also employ a call-market mechanism on specific

occasions such as at the open and during trading suspensions. The NYSE is such a market.

National Stock Exchanges Two U.S. securities exchanges are generally considered national

in scope: the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and the American Stock Exchange (AMEX). Out-

side the United States, each country typically has had one national exchange, such as the Tokyo

Stock Exchange (TSE), the London Exchange, the Frankfurt Stock Exchange, and the Paris

Bourse. These exchanges are considered national because of the large number of listed securities,

the prestige of the firms listed, the wide geographic dispersion of the listed firms, and the diverse

clientele of buyers and sellers who use the market. As we discuss in a subsequent section on

changes, there is a clear trend toward consolidation of these exchanges into global markets.

New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), the largest

organized securities market in the United States, was established in 1817 as the New York Stock

and Exchange Board. The Exchange dates its founding to when the famous Buttonwood Agree-

ment was signed in May 1792 by 24 brokers.8 The name was changed to the New York Stock Exchange in 1863.

At the end of 2000, approximately 3,000 companies had stock issues listed on the NYSE, for

a total of about 3200 stock issues (common and preferred) with a total market value of more than

$13.0 trillion. The specific listing requirements for the NYSE appear in Exhibit 4.2.

The average number of shares traded daily on the NYSE has increased steadily and substan-

tially, as shown in Exhibit 4.3. Prior to the 1960s, the daily volume averaged less than 3 million

shares, compared with current average daily volume in excess of 1 billion shares and numerous

days when volume is over 1.3 billion shares.

The NYSE has dominated the other exchanges in the United States in trading volume. Dur-

ing the past decade, the NYSE has consistently accounted for about 85 percent of all shares

traded on U.S.-listed exchanges, as compared with about 5 percent for the American Stock

Exchange and about 10 percent for all regional exchanges combined. Because share prices on

8The NYSE considers the signing of this agreement the birth of the Exchange and celebrated its 200th birthday during

1992. For a pictorial history, see Life, collectors’ edition, Spring 1992.