Preview text:

IN THE CLASSROOM

expectations of students in particular settings;

accreditation and standardized examination Reorienting chemistry

constraints; and the need to develop appropri-

ate assessments. These chal enges, which

hinder the reorientation of chemistry

education through systems

education to take on systems thinking, are

well worth addressing. To do this, we can thinking

make use of lessons learned in engineering,

biology and other branches of science that

have long embraced systems approaches in

Peter G. Mahaffy, Alain Krief, Henning Hopf, Goverdhan Mehta both education and practice. and Stephen A. Matlin

Why systems thinking in chemistry?

It is time for chemistry learning to be reoriented through systems thinking, which

Two important strands of argument support the

offers opportunities to better understand and stimulate students’ learning of

case for reorienting chemistry education today.

chemistry, such that they can address twenty-first century challenges.

First, the current systems of chemistry

education, particularly at the undergraduate

In biology courses, it is difficult to imagine

complex, dynamic and interdependent

level, face challenges that can be addressed by

studying organisms, such as Plasmodium spp.

systems. Chemistry systems and sub-systems

approaches that incorporate systems think-

parasites that cause malaria, without attending can be small and localized (much like a reac-

ing. Chemistry education researchers have

to their function as interdependent compo-

tion in a laboratory flask), or large and diffuse

documented the urgent need for the trans-

nents of a web of biological and other systems.

(as is the distribution of carbon dioxide in

formation of current approaches to teaching

Those systems need to be understood at

the Earth’s atmosphere, hydrosphere and bio-

chemistry. The crucial first course in many

different levels — from molecular and cel ular

sphere). Moreover, chemistry systems and their university undergraduate chemistry

mechanisms, through the development and

components interact with many other systems,

programmes — which serves a small number

habitat of parasites and hosts (including the

including the surrounding environment, lead-

of chemistry majors and a large number of

Anopheles mosquito), to the entire ecosystem

ing to both beneficial and harmful effects on

students embarking on careers related to

that regulates their life cycle and ultimately the biological, ecological, physical, societal and

life sciences and engineering — has been

socio-economic and environmental parameters other systems. Despite these interconnections,

described as “a disjointed trot through a

that influence transmission of disease. Similarly, systems thinking is relatively unfamiliar to

host of unrelated topics” (J. Chem. Educ. 87,

contemporary engineering education includes

chemists and chemistry educators. The learn-

231−232; 2010). General chemistry students

explicit pedagogical strategies designed to

ing objectives for chemistry programs at both

at the post-secondary level experience numer-

help learners see the interdependence of

the high school and university level rarely

ous isolated facts — theoretical concepts of

components that make up an object under

include substantial and explicit emphasis on

apparently little relevance to everyday life or to

con struction, such as a cell phone, a bridge or

strategies that move beyond understanding

problems faced in a slightly different discipline

a space shuttle. Systems thinking in STEM —

isolated chemical reactions and processes to

of chemistry to that in which the concepts

science, technology, engineering and envelop systems thinking.

were original y introduced. Additional y, there

mathematics — describes approaches embed-

This lack of a systems thinking orientation

remains an overemphasis on preparing al

ded in the practice of engineering and biology

has important implications for the education

undergraduate chemistry students for further

that move beyond the fragmented knowledge

of practicing chemists and of those who intend study in chemistry rather than on providing

of disciplinary content to a more holistic

to work in closely related molecular sciences,

them with the fundamental understanding

understanding of the field. In this way, prac-

such as biochemistry and molecular biology,

of molecular-level phenomena that will serve

tioners can see the forest while not losing sight

of which chemistry is an important pil ar. If we their needs as future scientists, engineers and

of the trees. Systems thinking approaches

do not pay due attention to systems thinking

informed citizens (Chemistry Education:

emphasize the interdependence of components we will miss opportunities to motivate second-

Best Practices, Innovative Strategies and New

of dynamic systems and their interactions with

ary and post-secondary students to connect

Technologies. Wiley, Weinheim, 3−26; 2015).

other systems, including societal and environ-

their study of chemistry to important issues

Incorporation of systems thinking into

mental systems. Such approaches often involve in their lives.

chemistry education offers opportunities

analyzing emergent behaviour, which is how

The reticence of chemistry educators to

to extend the students’ comprehension of

a system as a whole behaves in ways that go

emphasize systems thinking can be rational-

chemistry far beyond what is achievable

beyond what can be learned from studying the

ized in terms of concerns about overcrowded

through rote learning. Such a change would

isolated components of that system.

curricula; faculty inertia and the lack of a

enhance understanding of chemistry con-

Chemical reactions and processes, both in

knowledge base outside of disciplinary

cepts and principles through their study in

nature and industry, also function as parts of

specializations; the readiness, capacities, and

rich contexts. These include developing an

NATURE REVIEWS | CHEMISTRY

VOLUME 2 | ARTICLE NUMBER 0126 | 1

© 2 0 1 8 M a c m i l a n P u b l i s h e r s L i m i t e d , p a r t o f S p r i n g e r N a t u r e . A l r i g h t s r e s e r v e d . I N T H E C L A S S R O O M

appreciation of the place of chemistry in the Achieving these objectives

into learning progressions (Chem. Educ. Res.

wider world through analysing the linkages will be easier if those who

Pract. 15, 10–23; 2014) provides insights into

between chemical systems and physical,

how student chemistry thinking evolves and

biological, ecological and human systems study chemistry are educated

how the development can link with the efforts

(the latter include legal and regulatory sys- in how to engage in systems

of their educators to teach theory, relevance,

tems, social and behavioural systems, and

thinking and cross-disciplinary

applications and consequences. Educational

economic and political systems). approaches

approaches that introduce green chemistry and

Second, the sustainability chal enges faced

engineering principles, and life cycle analysis

by today’s planetary and societal systems

provide entry points for considering overlaps

require those in the chemical sciences, as wel

between the boundaries of different systems. A

as col aborators from other disciplines, to

• Stronger engagement among the educa-

variety of tools can assist in visualizing systems

adopt systems thinking approaches. Potential

tion, research and practice elements of

and the interactions between their compo-

challenges include finding cleaner energy

chemistry, including the important inter-

nents, including causal loop diagrams, concept

sources, developing cost-effective ways of

face between academia and industry.

mapping and dynamic systems modelling

purifying water, increasing soil quality and

• Enabling students to better understand

(Learning Objectives and Strategies for Infusing

crop yields, exploring alternative forms of

the interactions between chemistry and

Systems Thinking into (Post)-Secondary General

waste disposal, avoiding the exhaustion

other systems, including the physical, eco-

Chemistry Education. 100th Canadian Society

of crucial resources and protecting and pre-

logical and human systems of the planet,

for Chemistry Conference, Toronto, ON;

serving the planetary systems that sustain life.

and develop the capacity for thinking and May 30, 2017)

Oncoming chal enges in health include the

working across disciplinary boundaries, as

emergence and re-emergence of infectious

a prerequisite for understanding the

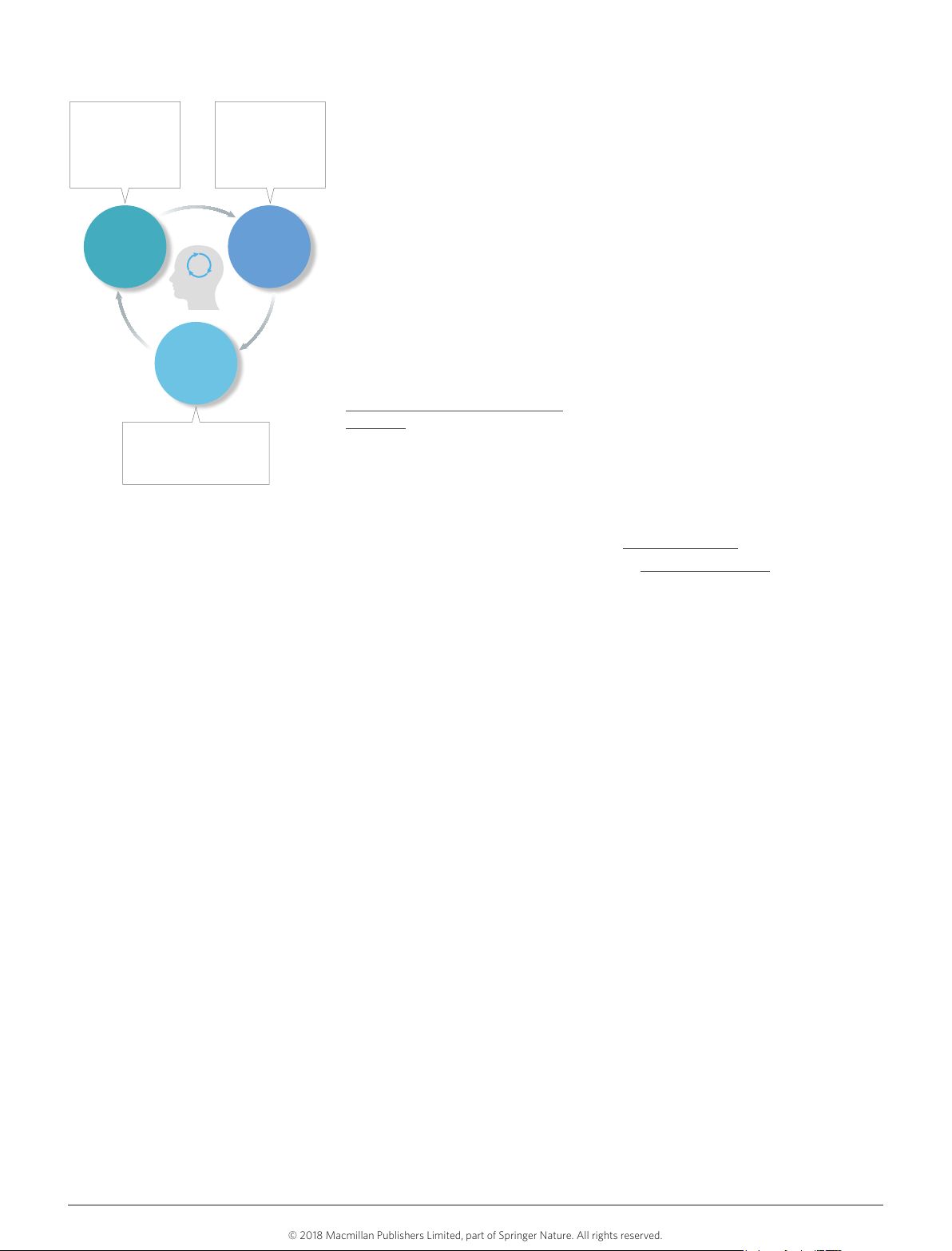

A framework for analysis

diseases, the explosive growth of rates of

relevance of chemistry to comprehensively In the context of introducing systems thinking

non-communicable diseases and diseases of

address twenty-first century chal enges,

into chemistry education, it is pertinent to ask

ageing, and the spread of antimicrobial resist-

including sustainable development.

a number of questions. What are the chemistry

ance. Addressing any of these problems wil

• Enabling the development of an evidence- systems that need to be understood? How do

require chemistry ingenuity to be combined

based approach to thinking about, under-

learners acquire an understanding of systems

with an appreciation of the interconnections

standing and responding to risk.

concepts and the ability to use systems tools

of human, animal and environmental systems

• Providing a framework for projecting

and processes? What are the important inter-

and of the role of effective, dynamic regulatory

chemistry as a ‘science for society’ that can actions between the chemistry system and

systems that can adapt quickly to changing

help to create positive attitudes towards

other systems? How can educators facilitate

circumstances. Achieving these objectives

the discipline from the media, public and

the acquisition, by learners, of the conceptual

will be easier if those who study chemistry are policy makers.

understanding and range of knowledge of the

educated in how to engage in systems thinking

other systems that is necessary for a systems

and cross-disciplinary approaches.

Strategies for introducing systems thinking

thinking approach to be meaningful?

The case of neuroactive neonicotinoid

Very little literature explicitly describes systems

The questions above may be addressed

pesticides provides one contemporary example thinking in chemistry education. Moreover,

by making use of a proposed framework

of the need to ful y consider interdependent

none of this literature addresses the compre-

for analysis (FIG. 1) (Learning Objectives

systems for chemical substances. Widely used

hensive reorientation called for (Nat. Chem. 8,

and Strategies for Infusing Systems Thinking

in agriculture because of the protection they

393–396; 2016) or outlined here. However,

into (Post)-Secondary General Chemistry

provide against soil, timber, seed and animal

many approaches to tackling learning chal-

Education. 100th Canadian Society for

pests, these pesticides have been implicated

lenges involve strategies for introducing

Chemistry Conference, Toronto, ON; May

in the major decline of populations of honey

aspects of systems thinking to learners. Here,

30, 2017). The chemistry learner is placed

bees, which are important vehicles in pollina-

students’ viewpoints can be widened if they

at the centre of this framework, which com-

tion. The growing evidence regarding the risks

look beyond the trees and think in terms of

prises three nodes or central elements that

that neonicotinoids may pose to pollinators,

the forest. Engaging in ‘forest thinking’ enables

contribute to the understanding of the inter-

ecosystems and systems of food production

students to consider changes over time, seeing

dependent components within and among

has prompted policy makers to propose or

data and concepts in rich contexts and by using the complex and dynamic systems involved

consider substantial restrictions on the use of

case-based and problem-based approaches to

in student learning. The learner systems node

neonicotinoids in agricultural systems around

learning (ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2,

explores and describes the processes at work the world.

2488–2494; 2014). At the pre-col ege level in

for learners, which include taxonomies of

On considering the challenges and exam-

the USA, the approach of the Next Generation

learning domains, learning theories, learning

ples above, one can imagine a compelling set

Science Standards (Next Generation Science

progressions, models for the phases of mem-

of potential benefits arising from re orienting Standards. www.nextgenscience.org) and the

ory, the transition from rote to meaningful

chemistry education toward systems

National Academies’ Framework on which

learning and social contexts for learning. The thinking:

they are based is to adopt three-dimensional

chemistry teaching and learning node focuses

• Strengthening opportunities for devel-

learning. This combines core ideas, practices

on features of learning processes applied to the

oping a more unified approach within

and cross-cutting concepts, placing particu-

unique challenges of learning chemistry. These

the discipline of chemistry itself, which

lar emphasis on concepts that help students

include the use of pedagogical content knowl-

is too often taught, researched and

explore connections across different domains

edge; analysis of how the intended curriculum

practiced within compartmentalized

of science. Importantly, attention is specifical y

is enacted, assessed, learned and applied; subdisciplines.

focused on understanding systems. Research

and student learning outcomes that include

2 | ARTICLE NUMBER 0126 | VOLUME 2

www.nature.com/natrevchem

© 2 0 1 8 M a c m i l a n P u b l i s h e r s L i m i t e d , p a r t o f S p r i n g e r N a t u r e . A l r i g h t s r e s e r v e d .

© 2 0 1 8 M a c m i l a n P u b l i s h e r s L i m i t e d , p a r t o f S p r i n g e r N a t u r e . A l r i g h t s r e s e r v e d . I N T H E C L A S S R O O M Features of Theoretical

Development Goals and descriptions of the

problems and advancing global sustainable learning processes frameworks of

earth’s planetary boundaries. Educational

development. These will be ample rewards for applied to the learning, learning

systems to address the interface of chemistry

making an effort that will chal enge traditional unique challenges progressions and of learning the social contexts

with earth and societal systems include green

approaches to teaching this vital y important chemistry for learning

chemistry and sustainability education, and discipline.

use tools such as life cycle analysis.

Peter G. Mahaffy is at the Department of Chemistry

and the King’s Centre for Visualization in Science,

Integrating systems thinking into practice Chemistry

The King’s University, Edmonton, Canada. teaching and Learner

Required now is the development of new learning systems

systems-oriented approaches to secondary

Alain Krief is at the International Organization for

Chemical Sciences in Development, Namur, Belgium;

school, high school and undergraduate chem-

the Chemistry Department, Namur University, Namur,

istry courses, including gateway introductory

Belgium; and the Hussain Ebrahim Jamal Research

post-high-school chemistry courses that serve

Institute of Chemistry, University of Karachi, Karachi,

both future chemists and many other future Pakistan. Earth and

scientists. New learning resources designed to

Henning Hopf is at the International Organization for societal

support such teaching are also needed

Chemical Sciences in Development, Namur, Belgium; systems

A project initiated in 2017 by the

and the Institute of Organic Chemistry, Technische

Universität Braunschweig, Braunschweig, Germany.

International Union of Pure & Applied

Chemistry (IUPAC) and supported by the

Goverdhan Mehta is at the International Organization Elements that orient

International Organization for Chemical

for Chemical Sciences in Development, Namur, chemistry education

Belgium; and the School of Chemistry, University of toward meeting societal

Sciences in Development (IOCD), with the

Hyderabad, Hyderabad, India. and environmental needs

participation of 18 global leaders in chemistry

education, has the goal of developing learn-

Stephen A. Matlin is at the International Organization

for Chemical Sciences in Development, Namur,

Figure 1 | A framework for analysis of systems ing objectives and strategies for integrating

Belgium; and the Institute of Global Health Innovation,

thinking in chemistry education. The

systems thinking into general undergraduate

Imperial College London, London, UK.

framework comprises three nodes or

chemistry education. It will use the frame- s.matlin@imperial.ac.uk

subsystems: learner systems, chemistry

work (FIG. 1) of the three interconnected nodes doi:10.1038/s41570.018.0126

teaching and learning, and earth and societal

of learner systems, chemistry learning and Published online 29 Mar 2018 systems.

teaching, and earth and societal systems as a Acknowledgements starting point.

We thank the International Organization for Chemical

responsibility for the safe and sustainable use

Reorienting chemistry education through

Sciences in Development for supporting a workshop hosted

of chemicals, chemical reactions and technol-

systems thinking can benefit students’ learning in Namur, Belgium during which this article was prepared.

We also acknowledge the contributions of Kris Ooms toward

ogies. The earth and societal systems node

of the subject. It can also enhance chemistry’s

visualizing the framework in Figure 1, and Tom Holme and

orients chemistry education toward meeting

impact as a science for the benefit of society,

Jennifer MacKellar for work on the earth and societal systems node.

societal and environmental needs articulated

further strengthening its already considerable

in initiatives such as the UN Sustainable

capacity to contribute to addressing global Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

NATURE REVIEWS | CHEMISTRY

VOLUME 2 | ARTICLE NUMBER 0126 | 3

© 2 0 1 8 M a c m i l a n P u b l i s h e r s L i m i t e d , p a r t o f S p r i n g e r N a t u r e . A l r i g h t s r e s e r v e d .

© 2 0 1 8 M a c m i l a n P u b l i s h e r s L i m i t e d , p a r t o f S p r i n g e r N a t u r e . A l r i g h t s r e s e r v e d .