Preview text:

Page 135 CHAPTER 4

Overview of elements of the financial report audit process LEARNING OBJECTIVES (LO) 4.1

Explain the difference between accounting and auditing and the

importance of professional scepticism and professional judgment to auditing. 4.2

Outline the logical process of identifying financial report

assertions, developing specific audit objectives and selecting auditing procedures. 4.3

Explain the relationships between audit procedures and evidence,

and describe common audit procedures used in an audit of a financial report. 4.4

Define sufficient appropriate audit evidence and its relationship to auditing procedures. 4.5 Outline the audit risk model. 4.6

Explain the concept of materiality. 4.7 Define types of audit tests. 4.8

Explain how an auditor may use the work of an expert or component auditor. 4.9

Describe the general requirement to document audit work and the

contents of audit working papers.

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-23 02:58:32. RELEVANT GUIDANCE ASA 200/ISA 200

Overall Objectives of the Independent Auditor and the

Conduct of an Audit in Accordance with Australian

(International) Auditing Standards ASA 230/ISA 230 Audit Documentation ASA 315/ISA 315

Identifying and Assessing the Risks of Material

Misstatement through Understanding the Entity and Its Environment ASA 320/ISA 320

Materiality in Planning and Performing an Audit ASA 330/ISA 330

The Auditor’s Responses to Assessed Risks ASA 450/ISA 450

Evaluation of Misstatements Identified during the Audit ASA 500/ISA 500 Audit Evidence ASA 501/ISA 501

Audit Evidence—Specific Considerations for Inventory

and Segment Information/Audit Evidence—Specific

Considerations for Selected Items ASA 540/ISA 540

Auditing Accounting Estimates, Including Fair Value

Accounting Estimates, and Related Disclosures ASA 580/ISA 580 Written Representations ASA 600/ISA 600

Special Considerations—Audits of a Group Financial

Report (Including the Work of Component Auditors) ASA 620/ISA 620

Using the Work of an Auditor’s Expert ASA 700/ISA 700

Forming an Opinion and Reporting on a Financial Report AUASB/IAASB

AUASB Glossary/Glossary of Terms GS 011

Third Party Access to Audit Working Papers Page 136

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-23 02:58:32. CHAPTER OUTLINE

Although a financial report audit is only one type of assurance engagement, it is

the most common. Therefore, in this chapter an overview of the elements of the

financial report audit process is provided.

While a financial report audit of a complex entity is a complicated process, even

the most complex audit has certain basic elements. This chapter compares

financial report auditing with accounting, and explains the basic elements of the

audit process, including professional scepticism and professional judgment.

These building blocks are necessary to understand how an audit is

accomplished in conformity with Australian auditing standards. Most of the

auditor’s work in forming an opinion on the financial report consists of obtaining

and evaluating evidence about the assertions in the financial report by applying

auditing procedures. It is important to understand each of the elements—audit

evidence, materiality, assertions and audit procedures—in order to comprehend

the audit of a financial report, which will be conducted within the framework of

the audit risk model and the client’s business risk.

The auditor must also prepare and maintain adequate audit working papers to

document their work. This chapter explains the function and content of audit working papers.

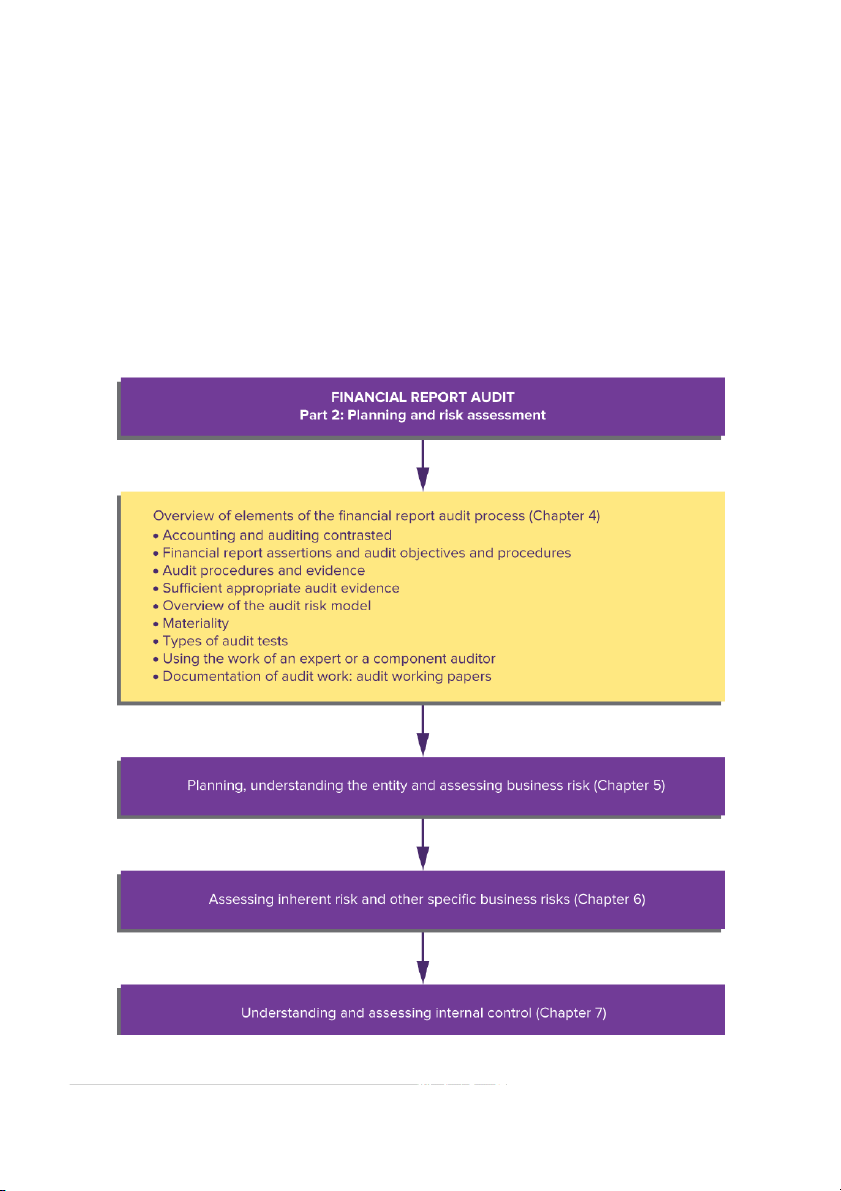

How this chapter fits into the overall financial report audit is illustrated in Figure 4.1

, which is an expansion of part of the overall flowchart provided in Chapter 1 .

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-23 02:58:32.

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-23 02:58:32.

FIGURE 4.1 Flowchart of planning and risk-assessment stage of a financial report audit

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-23 02:58:32. Page 137

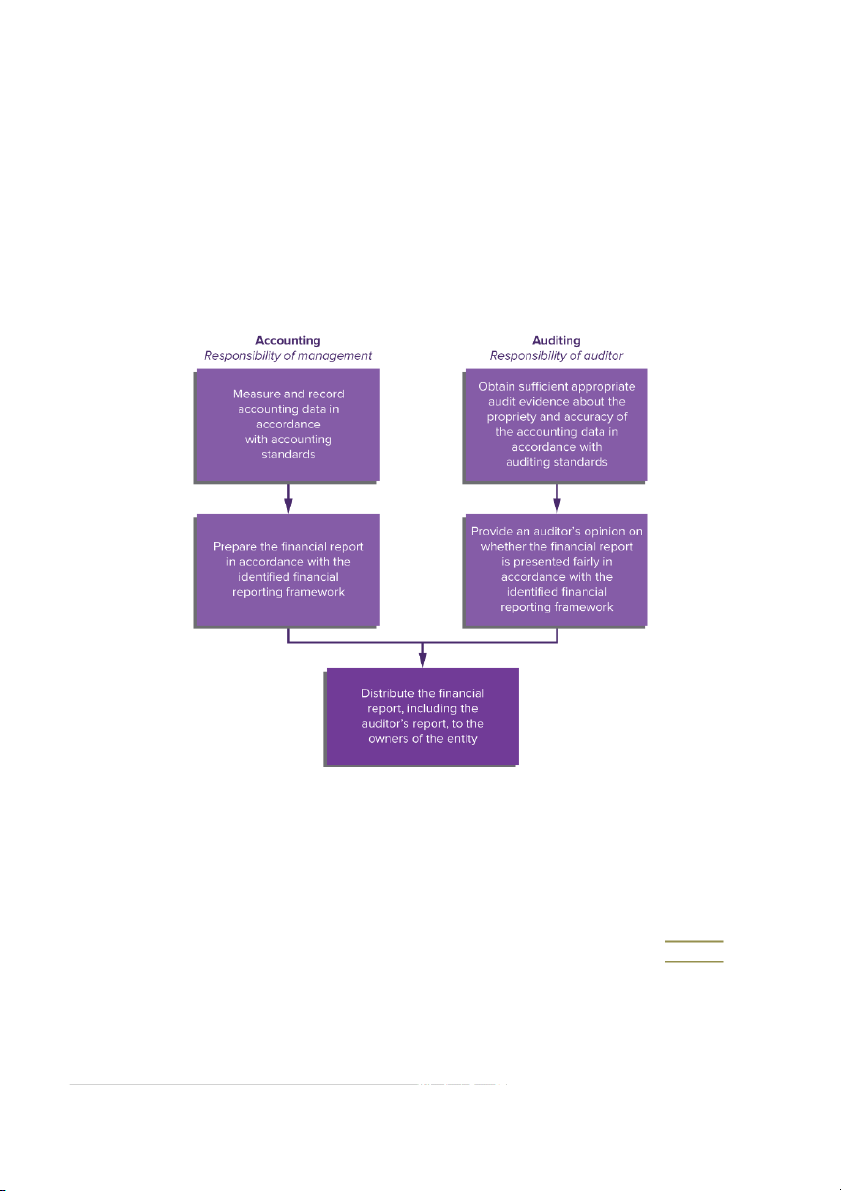

LO 4.1 Accounting and auditing contrasted

As a process, financial report auditing is linked with accounting principles and procedures

used by businesses and other entities. An auditor renders an opinion on the financial report

of an entity. The financial report is the product of the entity’s accounting system and of

judgments made by those charged with the governance and management of the entity.

As indicated by ASA 200.3 (ISA 200.3), the purpose of an audit is to enhance the degree of

confidence of intended users of the financial report. Therefore, the ultimate objective of the

audit process is to present an opinion on the presentation of results of operations for a

given period and on the financial position at the end of this period. To form such a

judgment about the financial report of an entity, the auditor must look behind the financial

report to the data and the allocations of the data.

Therefore, there is a close relationship between accounting and auditing. Auditors work

primarily with accounting data. They attempt to satisfy themselves that the data

summarised in the financial report are the data arising from transactions and events that the

entity actually experienced. Further, they must make judgments about the allocations of

data that have been made by those charged with governance and management, and decide

whether the financial report presentation is appropriate or misleading. To make these

judgments, auditors cannot limit themselves to the records and accounts of the entity. They

must be concerned with the total entity, because non-accounting activities, including the

behaviour of the participants in the entity, influence not only the data but also the

judgments of those charged with governance and management relating to the accounting

for and reporting of the data. The audit function focuses on accounting, and the auditor

must first be a competent accountant, but the audit function also extends beyond accounting (see Figure 4.2 ).

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-23 02:58:32.

FIGURE 4.2 Relationship between accounting and auditing Professional scepticism

The end product of an accountant’s work is a financial report. The financial report may

simply be the results of this work, or it may be adjusted according to the desires of those

charged with governance and management who might wish to classify and report Page 138

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

data in particular ways. As indicated by ASA 200.A48 (ISA 200.A48), it is

possible to prepare different financial reports from the same data, because accounting

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-23 02:58:32.

standards allow a choice between several acceptable accounting methods, and because

judgment will be exercised in determining the amounts for some accounts, such as for

various provisions. Also, as discussed in Chapter 1

, the preparers of the financial

reports are potentially biased, as they have a vested interest in the information contained in

the financial report. Therefore, ASA 200.15 (ISA 200.15) requires the auditor to plan and

perform the audit with professional scepticism

, recognising the possible existence of

material misstatements in the financial report. Professional scepticism is critical to the

audit process (see Auditing in the global news 4.1 ).

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-23 02:58:32.

4.1 Auditing in the global news ...

Professional scepticism lies at the heart of a quality audit

In 2015, the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB),

International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants (IESBA), and the

International Accounting Education Standards Board (IAESB) convened a

small, cross-representational working group—the Professional Scepticism

Working Group—to formulate views on whether and how each of the three

boards’ sets of international standards could further contribute to

strengthening the understanding and application of the concept of

professional scepticism as it applies to an audit.

Today, the topic of professional scepticism is featured prominently in each of

the board’s strategic considerations, and all three boards have important

initiatives related to professional scepticism. All three boards see the

opportunity for shorter term actions as well as the need for longer term

considerations, in consultation with each other.

The importance of professional scepticism to the public interest is

underscored by the increasing complexity of business and financial

reporting, including greater use of estimates and management judgments,

changes in business models brought about by technological developments,

and the fundamental reliance the public places on reliable financial reporting.

Source: IAASB, IESBA; IAESB (2017) ‘Towards Enhanced Professional Scepticism’, IFAC, August, New

York, p. 3. This text is an extract from ‘Towards Enhanced Professional Scepticism’ Observations of the

IAASB-IAESB-IESBA Professional Skepticism Working Group, published by the International Federation

of Accountants (IFAC) Aug 14, 2017 and is used with permission of IFAC. Such use of IFAC’s

copyrighted material in no way represents an endorsement or promotion by IFAC. Any views or

opinions that may be included in Auditing & Assurance Services in Australia 7e are solely those of

McGraw-Hill Education and do not express the views and opinions of IFAC or any independent

standard setting board associated with IFAC.

The Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (AUASB) Glossary describes professional

scepticism as ‘an attitude that includes a questioning mind, being alert to conditions which

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

may indicate possible misstatement due to error or fraud, and a critical assessment of audit evidence’.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-23 02:58:32.

Professional scepticism needs to be exercised throughout the planning and performance of

the audit. ASA 200.A20–A22 (ISA 200.A20–A22) indicate that professional scepticism includes:

questioning the reliability of documents, information and management explanations

being alert to possible contradictory evidence questioning the sufficiency and appropriateness of audit evidence

being alert to conditions that may indicate risks of fraud

critically challenging management judgments, assumptions and estimates.

Further, with the rapid changes in technology in recent years, such as data analytics, which

have not as yet been incorporated into the auditing standards, there is a need for the auditor

to consider whether circumstances exist that indicate a need for audit procedures Page 139

to be applied in addition to those required by the auditing standards.

Professional scepticism is essentially a mindset. A sceptical mindset drives auditor

behaviour to adopt a questioning approach when considering information and in forming

conclusions. As a result, professional scepticism is linked to the fundamental ethical

principles of objectivity and auditor independence discussed in Chapter 3 and is an

inescapable element in the exercise of professional judgment. Professional judgment

ASA 200.16 (ISA 200.16) requires the auditor to exercise professional judgment in

planning and performing the audit. The AUASB Glossary defines professional judgment as

‘the application of relevant training, knowledge and experience, within the context

provided by auditing, accounting and ethical standards, in making informed decisions

about the courses of action that are appropriate in the circumstances of the audit engagement’.

Further, ASA 200.A25 (ISA 200.A25) emphasises that professional judgment is essential

to conducting an audit, as it is required for decisions such as determining materiality,

assessing audit risk, evaluating audit evidence, assessing the reasonableness of accounting

estimates and evaluating management judgments concerning the application of the

applicable financial reporting framework, including the appropriateness of accounting

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

treatments and policies and the appropriateness of the going concern basis. As indicated by

ASA 200.6 (ISA 200.6), the concept of materiality is applied by the auditor in planning and

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-23 02:58:32.

performing the audit and in evaluating the effect of misstatements on the financial report.

Materiality will be discussed in detail later in this chapter in relation to planning and in Chapter 11

in relation to completion of the audit. Areas of audit interest

Separating the audit process into understandable parts requires a definition of the areas of

audit interest. The auditor is interested in the accountable activity of the entity; the

organisation of the entity, that is, its organisational structure ; and the risks arising

from its business strategy and the environment in which it operates, that is, its business risk .

Accountable activity of the entity

From an auditing perspective, there are three stages in the accounting process:

1. The collection of original data The original accounting data are exchanges of

consideration between an entity and other entities or individuals. These transactions take

the form of sales of product, purchases of raw materials, purchases of labour, lending of

money, borrowing of money, repaying of money and being repaid. These are the basic

data of accounting and the first and most basic areas of interest to the auditor. The auditor

must understand the flow of transactions through the accounting system. Therefore, one

of the important parts of the audit is a review of the accounting system, because a

substantial part of the effort in an audit is concerned with the operation of that system.

2. The allocations and reclassifications of accounting data Accounting journals are often

called the ‘books of prime entry’, because the first stage of the accounting process

consists of recording the exchange transactions of an entity in a journal. However,

accounting journals also contain entries that do not represent exchange transactions.

These entries are made to allocate and reclassify original exchange data to other accounts

in preparation for placement in the financial report. All the allocations and

reclassifications in an entity’s journals are made according to procedures and practices

that have been developed by accountants over the years. For example, there are both

acceptable and unacceptable ways of depreciating fixed assets, amortising other long-

lived assets and allocating labour and materials costs to periods. This part of the audit

depends on the auditor’s knowledge as an accountant. As an accountant, the auditor

knows which allocation and reclassification methods are acceptable, and must observe

what the entity has done and decide whether it has followed acceptable methods Page 140

and made acceptable choices where judgment is involved. As discussed earlier,

this will involve the auditor applying professional scepticism to client choices, judgments and estimates.

3. The presentation of the results of the accounting process As discussed in

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved. Chapter 1

, in order to add credibility to a report, the auditor needs to examine that

the subject matter is prepared in accordance with suitable criteria and provide an

assessment to accompany the report prepared by the responsible party. Hence, in

accordance with ASA 700 (ISA 700) and the Corporations Act 2001, in a financial report

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-23 02:58:32.

audit the auditor is required to report on whether the financial report presents fairly the

financial position and operating results (or gives a true and fair view) in accordance with

Australian accounting standards.

There are rules that govern the placement of various items in the financial report and the

terminology used to present them. The auditor must use accounting knowledge, at the

allocation stage, to decide whether the client has properly prepared the financial report.

Further, the auditor must review the accompanying notes to the financial report and judge

their adequacy and completeness. Guidance on these issues is available by reference to

accounting standards and other professional statements and to the disclosure requirements

contained in the Corporations Act 2001. Organisation of the entity

The auditor also has the internal organisational structure of the entity with which to work.

In auditing terminology this is referred to as internal control . The auditor can make

enquiries of client personnel and review the system of documentation used by the entity;

trace various types of transactions from initial to ultimate disposition in the system to

observe its functioning; and, finally, make an evaluation of the system to identify strengths

and weaknesses. These activities are part of the auditor’s evaluation of the controls over the

accounting system. The accuracy and reliability of the accounting system depends on how it is controlled.

The objectives of internal control are linked with the auditor’s concern with the flow of

transactions through the accounting system and the impact of business risk on the entity’s

ability to achieve its objectives. Internal control is designed and implemented to address

identified business risks that threaten the achievement of any of these objectives. Internal

control will be discussed further in Chapter 7 . Business risk

The auditor needs to understand the entity’s business strategy, its business environment and

the risks it faces to determine whether these might affect the financial report. Auditors use

their understanding of the client’s business, industry and risks to develop a more efficient

and effective audit. Business risk will be discussed later in this chapter and in detail in Chapter 5 .

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-23 02:58:32. QUICK REVIEW 1.

Accounting is concerned with measuring and recording data, while

auditing is concerned with obtaining sufficient appropriate evidence as

to their propriety and accuracy. 2.

Accounting involves the preparation of the financial report, while

auditing involves giving an opinion on the financial report. 3.

Professional scepticism and the exercise of sound professional

judgment are critical to a high-quality audit. 4.

One key area of audit interest is the accountable activity of the entity,

which includes the collection of original accounting data, the allocation

and reclassification of accounting data and the presentation of the

results in the financial report. 5.

A second key area of audit interest is the organisation of the entity, including internal control. 6.

A third key area of audit interest is the entity’s business risk.

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-23 02:58:32. Page 141

LO 4.2 Financial report assertions and audit objectives and procedures

In effect, by presenting a financial report, those charged with governance and management

are stating certain things about the entity’s financial position and operations. These

assertions by those charged with governance and management that are embodied in the

financial report are referred to as financial report assertions . The auditor uses

assertions to assess risks, by considering the different types of potential misstatements that

may occur and then designing appropriate audit procedures that address these risks. The

assertions deal essentially with recognition and measurement of the various elements of the

financial report and related disclosures. ASA 315 (ISA 315) has two categories of

assertions: classes of transactions and events and related disclosures, and account balances

and related disclosures. These are set out in ASA 315.A128 (ISA 315.A128), as follows in Exhibit 4.1 .

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-23 02:58:32.