Preview text:

Page 185 CHAPTER 5

Planning, understanding the entity and assessing business risk LEARNING OBJECTIVES (LO) 5.1

Explain why the decision to accept a client is important, and

describe the primary features of client acceptance and

continuance, including the purpose and content of an audit engagement letter. 5.2

Explain the importance of planning to the audit process. 5.3

Identify the important aspects of the auditor’s understanding of an entity and its environment. 5.4 Assess entity business risk. 5.5

Explain how an auditor develops an overall audit strategy and

prepares a detailed audit plan or audit program. 5.6

Describe the process of assigning and scheduling audit staff. 5.7

Outline the types and uses of analytical procedures and

distinguish those that are useful in obtaining an understanding of

an entity and assessing business risk.

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-27 00:34:19. RELEVANT GUIDANCE ASA 210/ISA 210

Agreeing the Terms of Audit Engagements ASA 220/ISA 220

Quality Control for an Audit of a Financial Report and

Other Historical Financial Information ASA 300/ISA 300

Planning an Audit of a Financial Report ASA 315/ISA 315

Identifying and Assessing the Risks of Material

Misstatement through Understanding the Entity and Its Environment ASA 330/ISA 330

The Auditor’s Responses to Assessed Risks ASA 510/ISA 510

Initial Audit Engagements—Opening Balances ASA 520/ISA 520 Analytical Procedures ASA 710/ISA 710

Comparative Information—Corresponding Figures and Comparative Financial Reports ASQC 1/ISQC 1

Quality Control for Firms that Perform Audits and Reviews

of Financial Reports and Other Financial Information,

Other Assurance Engagements and Related Services Engagements APES 110/IFAC

Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants APES 305 Terms of Engagement APES 320 Quality Control for Firms Page 186

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-27 00:34:19. CHAPTER OUTLINE

Before commencing an audit, the auditor must determine whether to accept the

client and undertake the audit. This requires an understanding of the entity and

its environment. After the audit commences, the planning and conduct of the

audit are influenced by the auditor’s understanding of the entity’s operations,

trends within its industry and the effects of economic and political influences on

the entity. The auditor uses this knowledge to identify existing or potential

accounting and auditing problems and to develop an overall audit strategy and

a detailed audit plan or program for the conduct and scope of the audit.

The major topics covered in this chapter are acceptance and continuance of

audit clients, including evaluation of potential clients, communications with a

previous auditor, engagement letters and preliminary conferences with the

client; audit planning, including obtaining an understanding of the entity’s

organisational structure, its operations and its industry; assessing client

business risk; developing an overall audit strategy and a detailed audit plan or

program; assigning and scheduling audit staff; and using analytical procedures

for identifying and investigating unusual changes in account balances or

transaction totals, for planning purposes.

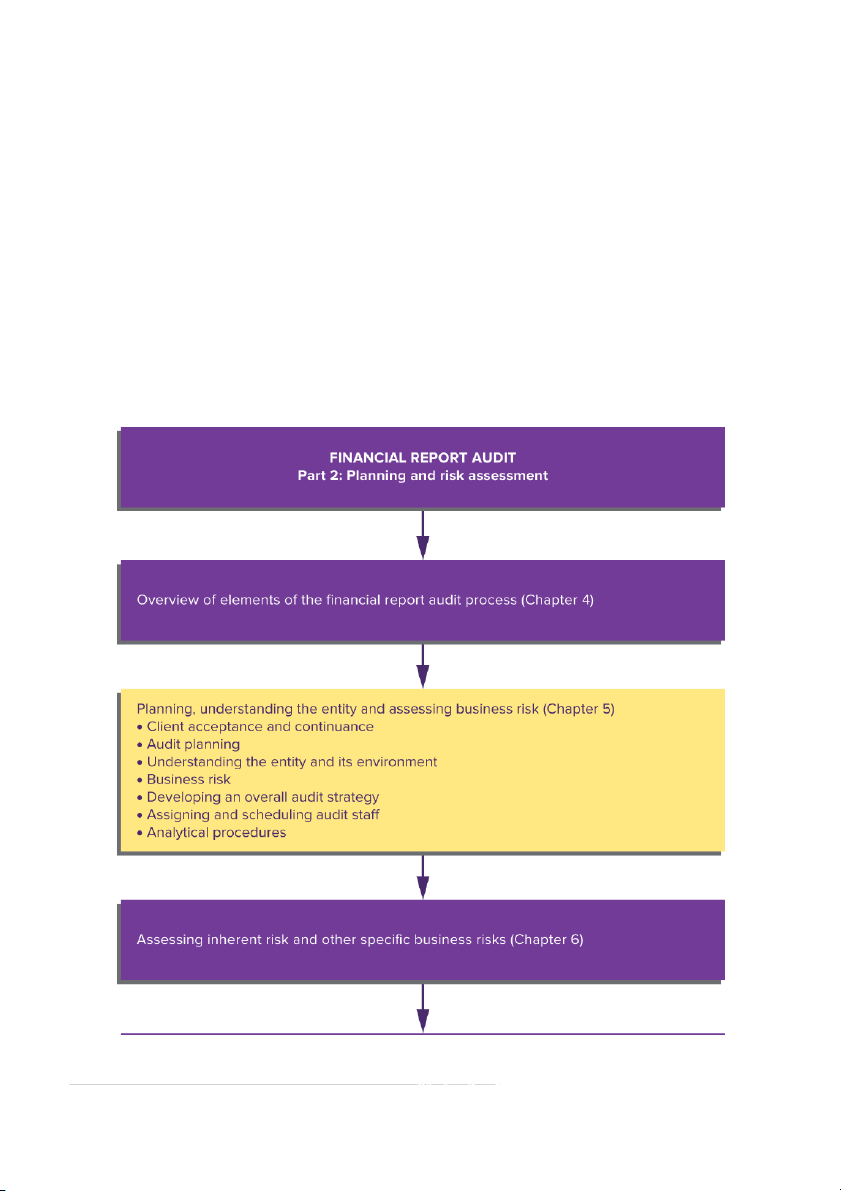

How this chapter fits into the overall financial report audit is illustrated in Figure 5.1

, which is an expansion of part of the overall flowchart provided in Chapter 1 .

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-27 00:34:19.

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-27 00:34:19.

FIGURE 5.1 Flowchart of planning and risk-assessment stage of a financial report audit

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-27 00:34:19. Page 187

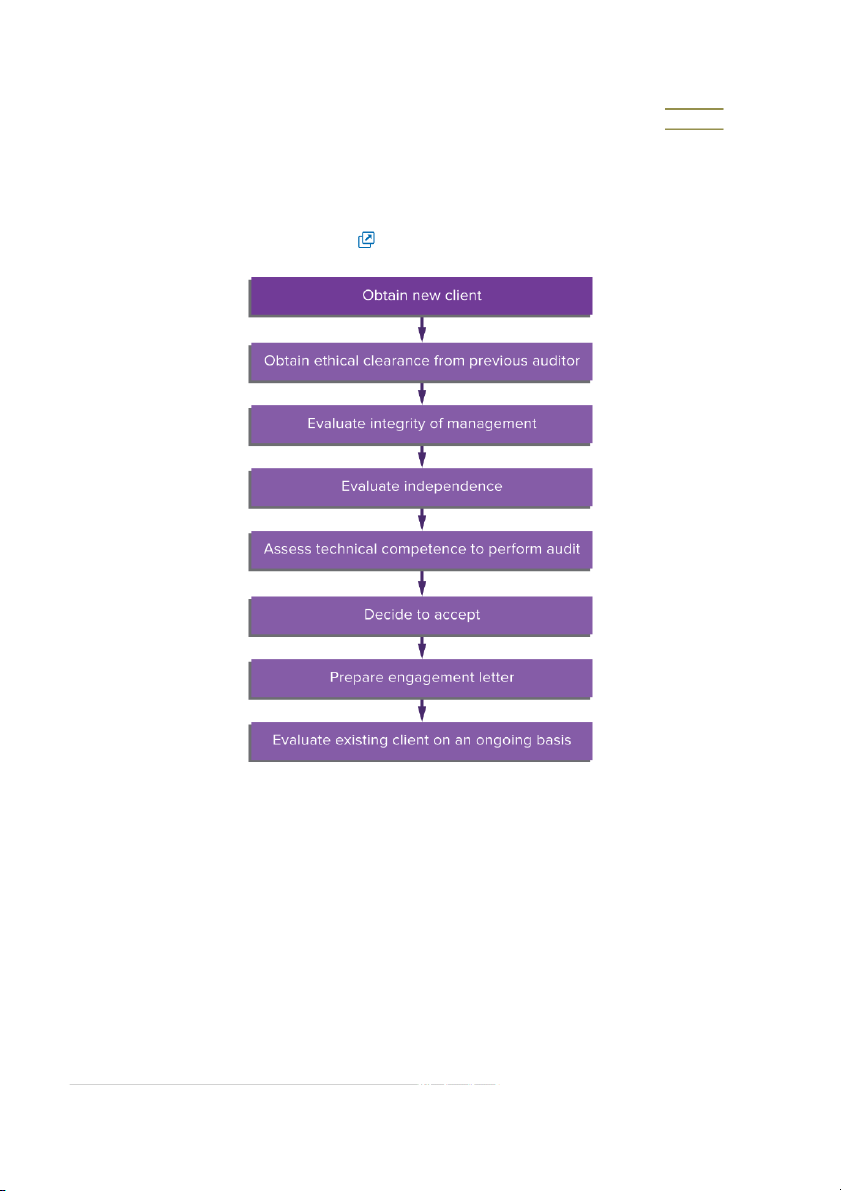

LO 5.1 Client acceptance and continuance

The auditor’s need to understand the client starts when considering acceptance of an

engagement and continues throughout association with the client. The steps in accepting an

audit client are shown in Figure 5.2 .

FIGURE 5.2 Steps in accepting an audit Obtaining clients

Since the services of public accounting firms are of a highly personal nature and involve

individual character traits such as competence and integrity, the auditor’s services cannot

be offered in the same manner that commercial goods and services are sold. The most

effective way of obtaining recommendations is to render services of a high quality.

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-27 00:34:19.

APES 110 section 250.2 permits advertising provided that its content and nature is not

false, misleading or deceptive and does not otherwise reflect adversely on the profession.

As a result, an auditor should not:

make exaggerated claims for services offered, qualifications possessed or experience gained

make disparaging references or unsubstantiated comparisons to the work of another

falsely advertise or mislead potential clients.

Potential clients may be approached personally or through direct mailing to make known

the range of services that the audit firm offers. However, follow-up communications must

be terminated when requested by the recipient or this will be considered harassment, which is unprofessional conduct.

An issue that has been around for a number of years, but continues to occur frequently in

practice and has caused some concern within the audit profession, is the calling by

companies for competitive tenders for audit appointments, and the active involvement by audit firms in the tendering

process. This issue is symptomatic of the increased

competition for audit work. While acknowledging the right of companies to choose their

auditors in order to obtain the most cost-efficient audit, there is a major danger for Page 188

the profession in the potential loss of credibility that could result from a real or

perceived loss of independence of the auditor, by being placed in a position where there

may be an unreasonable threat of dismissal as a result of the auditor’s actions. An example

is the practice of opinion shopping

. This may occur where an audit is put out to tender

following the issue of a modified opinion by the previous auditor or where a new issue

arises that may involve consideration of the issuing of a modified opinion and the client

seeking the views of potential new auditors as to how they would interpret the client’s

action in terms of the application of a certain accounting practice. APES 110 section 230.2

indicates that when an auditor is requested by an entity to give an opinion on an actual or

hypothetical accounting issue, they should consider the potential effect on the professional

responsibilities of the auditor, the purpose of the request and the intended use of any

response. The auditor whose opinion is requested is also required to communicate with the

existing auditor and provide a copy of the opinion to them. Tendering may also subject an

auditor to undue pressure because of the cost of the audit examination and the ability to

conduct the necessary audit procedures and the impact of low-balling (discussed in Chapter 3

), where firms bid an unreasonably low fee to win the tender. While it is

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

likely that the practice of audit tendering will continue, audit firms must recognise that the

tender they submit needs to reflect the level of professional skill, knowledge and

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-27 00:34:19.

responsibility required for the audit work. Auditors and management should also be aware

of the increased audit risk and hidden costs associated with changes of client as a result of

the tendering process—for example, the loss of audit continuity and the extensive

knowledge of a client’s business and personnel by the audit firm, which are beneficial to an

effective audit process. On the other hand, the tendering process appears to have led to

some increases in audit efficiency as auditors have implemented more efficient and effective audit techniques. As indicated in Chapter 3

, audit tendering received recent support in the European

Commission Green Paper, which recommended mandatory rotation of audit firms

accompanied by mandatory tendering with full transparency with regard to the criteria

according to which the auditor will be appointed. The Green Paper recommended that

quality and independence should be key selection criteria in any tendering procedure.

Subsequent legislation has provided for the rotation period for audit firms for European

Union companies to be extended if a public tender is held after 10 years.

Quality control policies and client evaluation procedures

APES 320 section 38 and ASQC 1.26–28 (ISQC 1.26–28) require an audit firm, as part of

its quality control, to establish policies and procedures for investigating potential clients

and acceptance of an engagement and for periodically reviewing continuance of clients.

Policies and procedures for client acceptance and continuance are important because an

audit firm needs to take precautions to avoid association with a client whose management

lacks integrity. This will include consideration of the identity and business reputation of the

client’s principal owners, key management, related parties and those charged with its

governance, as well as the nature of the client’s operations, including its business practices. As discussed in Chapter 3

, care should also be exercised to avoid situations where the

auditor–client relationship lacks independence and where there are other impediments to

undertaking the audit function, such as an inability to serve the client properly owing to a

lack of competence, time or resources. In addition, an auditor needs to consider the effect

of a client’s reputation on its image in the financial community, as well as the increased

risk of litigation, which was discussed in Chapter 2 .

ASA 220.12 (ISA 220.12) requires that the engagement partner be satisfied that

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

appropriate procedures have been followed regarding the acceptance and continuance of

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-27 00:34:19.

clients. Procedures that may be used to establish the appropriateness of accepting clients include:

obtaining and reviewing available financial information concerning the prospective

client, such as annual reports, interim financial reports and income tax returns

making enquiries of third parties, such as the client’s bankers, legal advisers or

investment banker, concerning the integrity of the prospective client and its management

communicating with the previous auditor

considering circumstances in which the engagement would require special attention or present unusual risks

evaluating the firm’s independence and ability to serve the client, including Page 189

technical skills, knowledge of the industry and personnel

determining that acceptance of the client would not violate the Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants.

APES 320 section 43 and ASQC 1.A21 (ISQC 1.A21) indicate that when deciding whether

to continue a client relationship, the auditor needs to consider significant matters that have

arisen during the current or previous period and their implications for continuing the

relationship. Examples of significant matters include:

a major change in ownership, directors, management, legal advisers, financial condition,

litigation status, scope of the engagement and/or nature of the client’s business

the existence of conditions that would have caused the auditor to reject the client had

such conditions existed at the time of the initial acceptance.

Much of the information relevant to this process should be available to the auditor through

the records and working papers of the audit itself.

Communication with a previous auditor

Normally, an auditor who accepts a new client is replacing another auditor. Therefore,

when approached by a potential client, an auditor should enquire about the client’s present

arrangements for accounting and auditing work. If the previous financial report has been

audited, the ethical rules of the Australian accounting profession, which were discussed in Chapter 3

, require that the prospective auditor has the opportunity to ascertain whether

there are any professional reasons why the appointment should not be accepted.

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

APES 110 sections 210.13–14 require that, before accepting a nomination, an auditor must:

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-27 00:34:19.

request the prospective client’s permission to communicate with the previous auditor

if permission is refused, carefully consider such refusal when determining whether to accept the engagement, or

on receipt of permission, ask the previous auditor in writing for all information necessary

to enable a decision as to whether the nomination should be accepted.

The auditor should treat the reply from the previous auditor in the strictest confidence and

judge whether the factors precipitating the proposed change are unusual, or whether they

indicate that the previous auditor is being treated unfairly.

APES 110 section 210.12 points out that the previous auditor is bound by a duty of

confidentiality, as discussed in APES 110 section 140. Therefore, in the absence of the

client’s permission to do so, the previous auditor should not volunteer information about

the client’s affairs. However, where the previous auditor does provide information, APES

110 section 210.13 requires that it should be provided honestly and unambiguously.

APES 110 section 210.13 requires that if the proposed auditor is unable to communicate

with the previous auditor, the proposed auditor should try to obtain information about

possible threats by other means, such as enquiries of third parties or background

investigations on senior management and those charged with the governance of the prospective client.

As a result of this process of communication, the interests of three groups are protected:

An auditor does not accept an appointment in circumstances of which they are not fully aware.

Shareholders are fully informed of the circumstances in which the change is proposed.

The existing auditor cannot be easily removed or interfered with in the conscientious

exercise of their duty as an independent professional.

While enquiries of the previous auditor about matters that bear on acceptance of the client

are required prior to acceptance, the auditor may also make enquiries of the previous

auditor after acceptance. For example, the auditor needs to consider the relationship of the

financial report of the previous period to the financial report of the current period on which

the auditor will express an opinion.

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved. Page 190 Engagement letters

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-27 00:34:19.

After accepting an appointment, ASA 210.9 (ISA 210.9) and APES 305.3.1 require the

auditor and the entity to agree on the terms of engagement. ASA 210.10–11 (ISA 210.10–

11) require that the agreed terms of the engagement shall be recorded in an engagement letter

or other suitable form of written agreement, unless law or regulation prescribes in

sufficient detail the terms of the audit engagement. The auditor should document the

arrangements made with the client and clarify any matters that may be misunderstood. This

should help protect the audit firm and ensure that the client fully understands the auditor’s position.

The form and content of the audit engagement letter vary for each client. It should

generally include reference to the following matters set out in ASA 210.10 (ISA 210.10):

the objective and scope of the financial report audit

the auditor’s responsibilities

management’s responsibilities

the identification of the applicable financial reporting framework

the form and contents of any reports, and a statement indicating that there may be

circumstances in which the form and content may differ.

An example of an audit engagement letter is contained in Appendix 1 to ASA 210 (ISA

210). A sample of an audit engagement letter prepared on this basis is presented in Exhibit 5.1

. The letter may need to be modified in accordance with the circumstances.

Other matters that could be included are: specification of the schedules to be prepared by

the client; arrangements concerning the involvement of other auditors, experts or internal

auditors; and the method and frequency of billing of fees.

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-27 00:34:19. EXHIBIT 5.1

SAMPLE AUDITOR’S ENGAGEMENT LETTER Jan Smith & Associates Chartered Accountants 30 Banks St Newtown The Managing Director ABC Ltd 15 Queen Street Newtown Dear Mr Spencer Scope

You have requested that we audit the financial report of ABC Ltd as of and for the

year ending 30 June 20X5. We are pleased to confirm our acceptance and our

understanding of this engagement by means of this letter. Our audit will be conducted

pursuant to the Corporations Act 2001 with the objective of expressing an opinion on the financial report.

Responsibilities of the auditor

We will conduct our audit in accordance with the Australian auditing standards.

These standards require that we comply with ethical requirements and plan and

perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial report is

free from material misstatement.

An audit involves performing procedures to obtain audit evidence about the amounts

and disclosures in the financial report. The procedures selected depend on the

auditor’s judgment, including the assessment of the risks of material misstatement of

the financial report, whether due to fraud or error. An audit also includes evaluating

the appropriateness of accounting policies used and the reasonableness of accounting

estimates made by management, as well as evaluating the overall presentation of the financial report.

Because of the inherent limitations of an audit, together with the inherent limitations

of internal control, there is an unavoidable risk that some material misstatements may

not be detected, even though the audit is properly planned and performed in

accordance with the Australian auditing standards.

In making our risk assessments, we consider internal control relevant to the Page 191

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

entity’s preparation of the financial report, in order to design audit

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-27 00:34:19.

procedures that are appropriate in the circumstances, but not for the purpose of

expressing an opinion on the effectiveness of the entity’s internal control.

However, we will communicate to you in writing concerning any significant

deficiencies in internal control relevant to the audit of the financial report that we identify during the audit. Responsibilities of management

Our audit will be conducted on the basis that management and directors acknowledge

and understand that they have responsibility: (a)

for the preparation of the financial report that gives a true and fair view in

accordance with the Corporations Act 2001 and the Australian accounting standards (b)

for such internal control as management determines is necessary to enable the

preparation of the financial report that is free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error (c) to provide us with: (i)

access to all information of which the directors and management are

aware that is relevant to the preparation of the financial report, such as

records, documentation and other matters (ii)

additional information that we may request from the directors and

management for the purpose of the audit (iii)

unrestricted access to persons within the entity from whom we

determine it necessary to obtain audit evidence.

As part of our audit process, we will request from management and, where

appropriate, directors written confirmation concerning representations made to us in connection with the audit.

Other matters under the Corporations Act 2001 Independence

We confirm that, to the best of our knowledge and belief, we currently meet the

independence requirements of the Corporations Act 2001 in relation to the audit of

the financial report. In conducting our audit of the financial report, should we

become aware that we have contravened the independence requirements of the

Corporations Act 2001, we shall notify you on a timely basis. As part of our audit

process, we shall also provide you with a written independence declaration as

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

required by the Corporations Act 2001.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-27 00:34:19.

The Corporations Act 2001 includes specific restrictions on the employment

relationships that can exist between the audited entity and its auditors. To assist us in

meeting the independence requirements of the Corporations Act 2001, and to the

extent permitted by law and regulation, we request you discuss with us:

the provision of services offered to you by Jan Smith & Associates prior to

engaging or accepting the service

the prospective employment opportunities of any current or former partner or

professional employee of Jan Smith & Associates prior to the commencement of

formal employment discussions with the current or former partner or professional employee. Annual general meetings

The Corporations Act 2001 provides that shareholders can submit written questions

to the auditor before an annual general meeting, provided that they relate to the

auditor’s report or the conduct of the audit. To assist us in meeting this requirement

in the Corporations Act 2001 relating to annual general meetings, we request that you

provide to us written questions submitted to you by shareholders as soon as

practicable after the question(s) has been received and no later than five business

days before the annual general meeting, regardless of whether you believe the questions(s) to be irrelevant.

Presentation of audited financial report on the internet

It is our understanding that the entity intends to publish a hard copy of the audited

financial report and auditor’s report for members, and to electronically present the

audited financial report and auditor’s report on its internet website. When

information is presented electronically on a website, the security and Page 192

controls over information on the website should be addressed by the entity to

maintain the integrity of the data presented. The examination of the controls over the

electronic presentation of audited financial information on the entity’s website is

beyond the scope of the audit of the financial report. Responsibility for the electronic

presentation of the financial report on the entity’s website is that of the governing body of the entity. Fees

We look forward to full cooperation with your staff and we trust that they will make

available to us whatever records, documentation and other information we request in

connection with our audit. Our fees, which will be billed as work progresses, are

based on the time required by the individuals assigned to the engagement, plus out-

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

of-pocket expenses. Individual hourly rates vary according to the degree of

responsibility involved and the experience and skill required.

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-27 00:34:19. Reporting

We will issue an auditor’s report expressing our opinion on the financial report of

ABC Ltd in accordance with the Australian auditing standards. The form and content

of our report may need to be amended in the light of our audit findings.

Please sign and return the attached copy of this letter to indicate that it is in

accordance with your understanding of the arrangements for our audit of the financial

report, including our respective responsibilities. Yours faithfully Jan Smith Partner 15 September 20X5

Acknowledged on behalf of ABC Ltd by Jim Spencer Managing Director 30 September 20X5

On recurring audits, ASA 210.13 (ISA 210.13) requires the auditor to assess whether

circumstances require the terms of the engagement to be revised and whether it is

necessary to remind the entity of the existing terms of the audit engagement.

Conferences with the client’s personnel

Soon after acceptance of an engagement, the auditor should meet with key client personnel,

including the principal administrative, financial and operating officers, the chief internal

auditor, and the IT (information technology) manager, to discuss matters expected to have a

significant effect on the financial report or on the conduct of the audit.

Good relations with client personnel are important. An audit usually causes considerable

inconvenience and disruption to some personnel, and their assistance is often needed to

obtain documents, records and explanations of various matters. Effective early conferences

establish a foundation for a good working relationship with all client personnel.

Effective communications with top management are particularly important. The auditor

should have an opportunity to consider the accounting implications of important planned

Copyright © 2018. McGraw-Hill Australia. All rights reserved.

transactions, such as merger negotiations or lease or purchase decisions. The chief

executive officer should be informed on a regular basis of new accounting and disclosure

Gay, Grant E., and Roger Simnett. Auditing and Assurance Services in Australia, McGraw-Hill Australia, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cdu/detail.action?docID=5729228.

Created from cdu on 2020-08-27 00:34:19.