Preview text:

Applied Programming and Design Principles Lecture 2

Overview Of Programming Paradigms Clean Architecture A CRAFTSMAN’S GUIDE TO SOFTWARE STRUCTURE AND DESIGN Lesson’s objectives • Structured Programming • Functional Programming

• Object-Oriented Programming PROGRAMMING PARADIGMS

• In 1938, Alan Turing laid the foundations of what was to become computer programming

• He was not the first to conceive of a programmable machine, but he

was the first to understand that programs were simply data

• By 1945, Turing was writing real programs on real computers in code that we would recognize

• Those programs used loops, branches, assignment, subroutines,

stacks, and other familiar structures

• Turing’s language was binary. Martin, R.C. (2017). PROGRAMMING PARADIGMS [2]

• Since those days, a number of revolutions in programming have occurred.

• First, in the late 1940s, came assemblers.

• In 1951, Grace Hopper invented A0, the first compiler. In fact, she coined the term compiler.

• Fortran was invented in 1953

• What followed was an unceasing flood of new programming

languages—COBOL, PL/1, SNOBOL, C, Pascal, C++, Java, ad infinitum. PROGRAMMING PARADIGMS [3]

• Another, probably more significant, revolution was in programming paradigms.

• Paradigms are ways of programming, relatively unrelated to languages

• A paradigm tells you which programming structures to use, and when to use them. Martin, R.C. (2017). STRUCTURED PROGRAMMING [1]

• The first paradigm to be adopted (but not the first to be invented)

was structured programming, which was discovered by Edsger Wybe Dijkstra in 1968

• Dijkstra showed that the use of unrestrained jumps (goto statements)

is harmful to program structure.

• He replaced those jumps with the more familiar if/then/else and do/while/until constructs

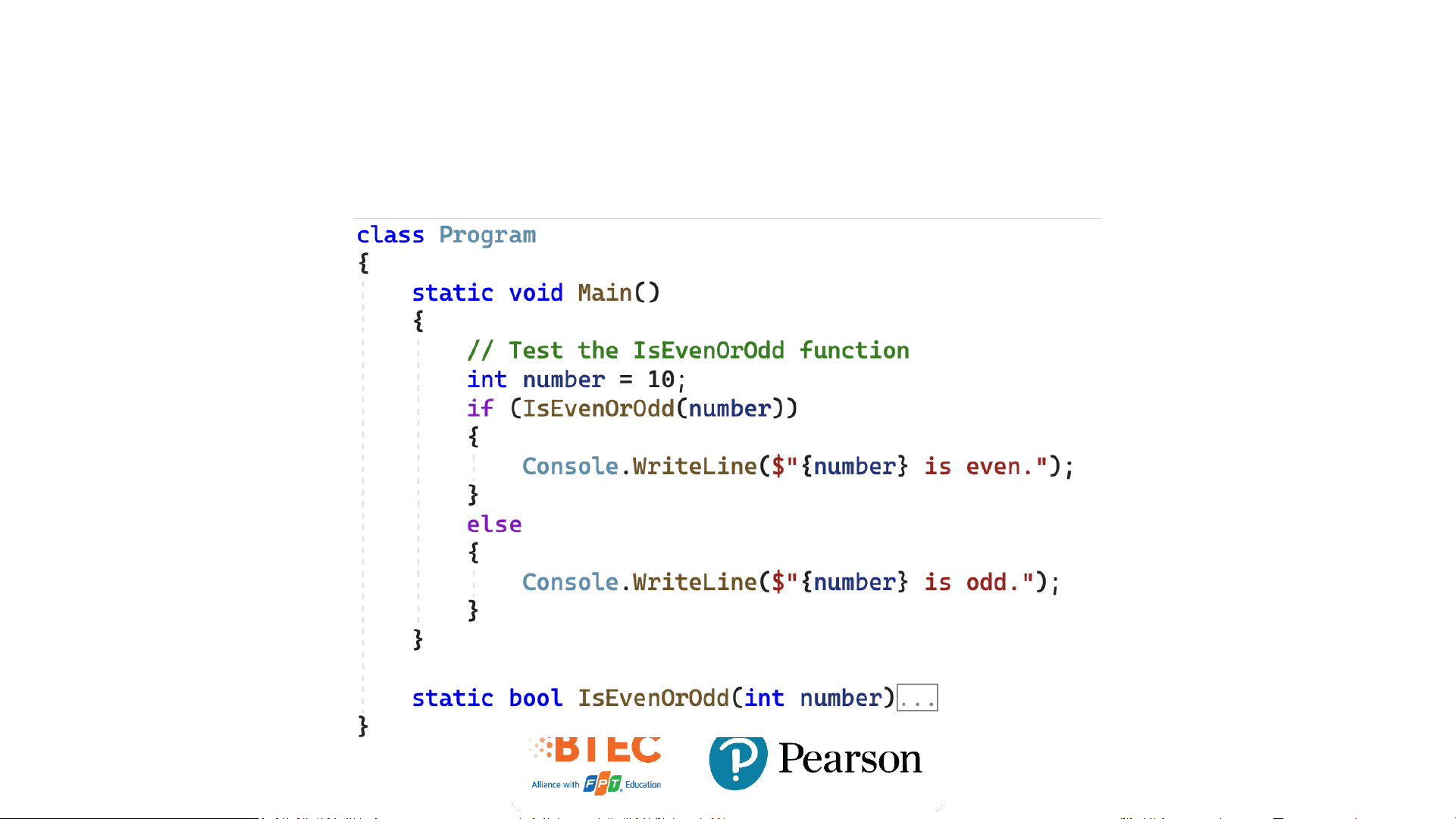

An example of structured programming STRUCTURED PROGRAMMING [2]

• Dijkstra started his career in the era of vacuum tubes, when

computers were huge, fragile, slow, unreliable, and (by today’s standards) extremely limited.

• In those early years, programs were written in binary, or in very crude assembly language

• Input took the physical form of paper tape or punched cards.

• The edit/compile/test loop was hours —if not days—long Martin, R.C. (2017). STRUCTURED PROGRAMMING [3]

• Dijkstra discovered that certain uses of goto statements prevent

modules from being decomposed recursively into smaller and smaller

units, thereby preventing use of the divide-and-conquer approach

necessary for reasonable proofs

• Other uses of goto, however, did not have this problem. Dijkstra

realized that these “good” uses of goto corresponded to simple

selection and iteration control structures such as if/then/else and do/while. STRUCTURED PROGRAMMING [4]

• Dijkstra knew that those control structures, when combined with

sequential execution, were special

• They had been identified two years before by Böhm and Jacopini,

who proved that all programs can be constructed from just three

structures: sequence, selection, and iteration. STRUCTURED PROGRAMMING [5]

• In 1968, Dijkstra wrote a letter to the editor of CACM

• The title of this letter was “Go To Statement Considered Harmful.”

• The feedback from the programming world is mostly negative

• And so the battle was joined, ultimately to last about a decade.

• Eventual y, the argument petered out. The reason was simple: Dijkstra had won.

• Most modern languages do not have a goto statement FUNCTIONAL DECOMPOSITION

• Structured programming allows modules to be recursively

decomposed into provable units, which in turn means that modules

can be functionally decomposed.

• That is, you can take a large-scale problem statement and decompose it into high-level functions

• Each of those functions can then be decomposed into lower-level functions, ad infinitum.

• Building on this foundation, disciplines such as structured analysis

and structured design became popular in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s Martin, R.C. (2017). TESTS

• Dijkstra once said, “Testing shows the presence, not the absence, of bugs.”

• In other words, a program can be proven incorrect by a test, but it cannot be proven correct

• Structured programming forces us to recursively decompose a

program into a set of small provable functions.

• We can then use tests to try to prove those small provable functions incorrect

• If such tests fail to prove incorrectness, then we deem the functions

to be correct enough for our purposes OBJECT-ORIENTED PROGRAMMING • Some definitions of OO:

• The combination of data and function

• A way to model the real world.

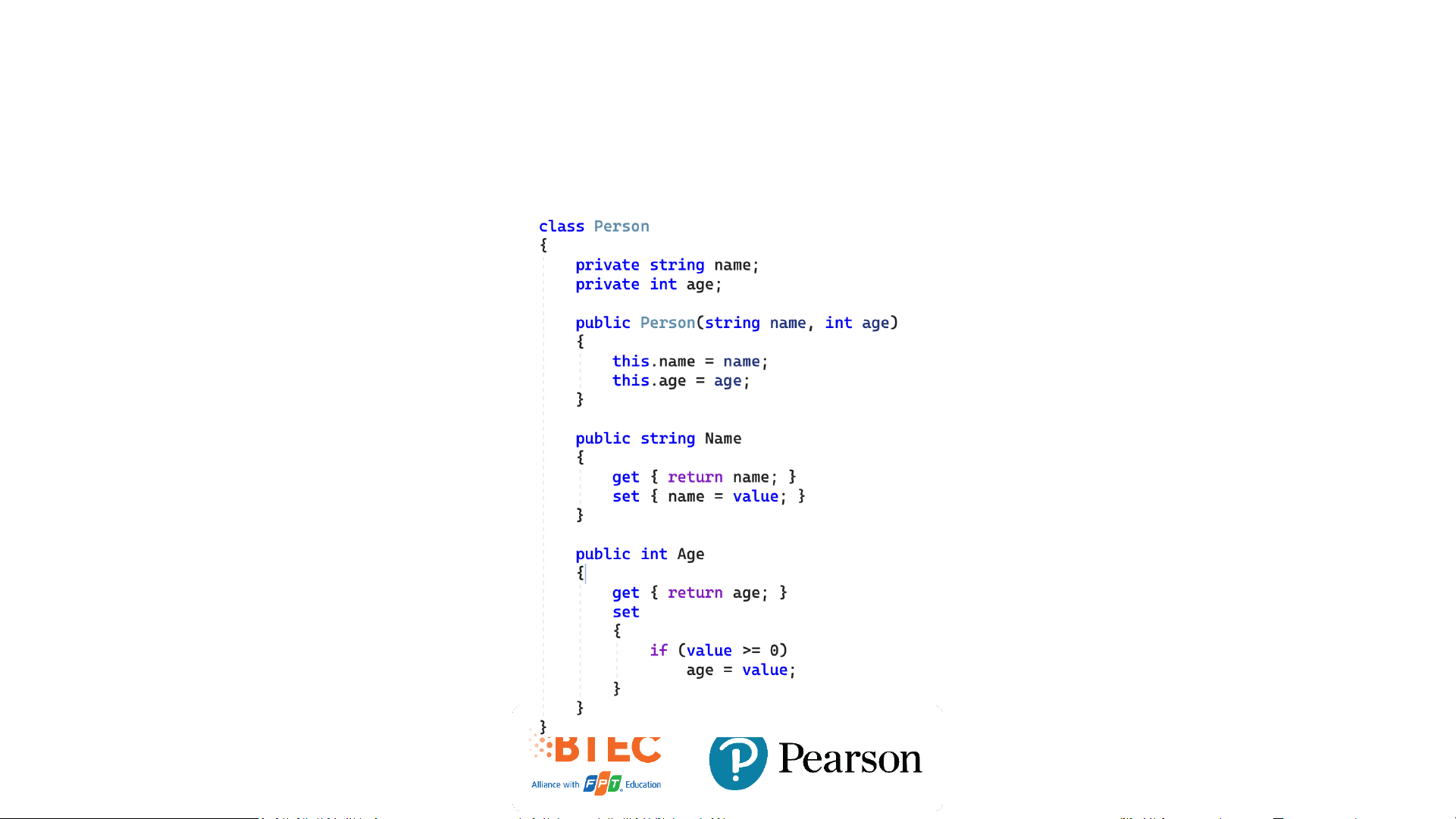

• Nature of OO: encapsulation, inheritance, and polymorphism. Encapsulation

• Encapsulation is one of the fundamental principles of object-oriented

programming that allows you to hide the internal details of an object

and only expose a controlled and well-defined interface to the outside world

• In C#, you can achieve encapsulation using classes, access modifiers, and properties An encapsulation example Polymorphism

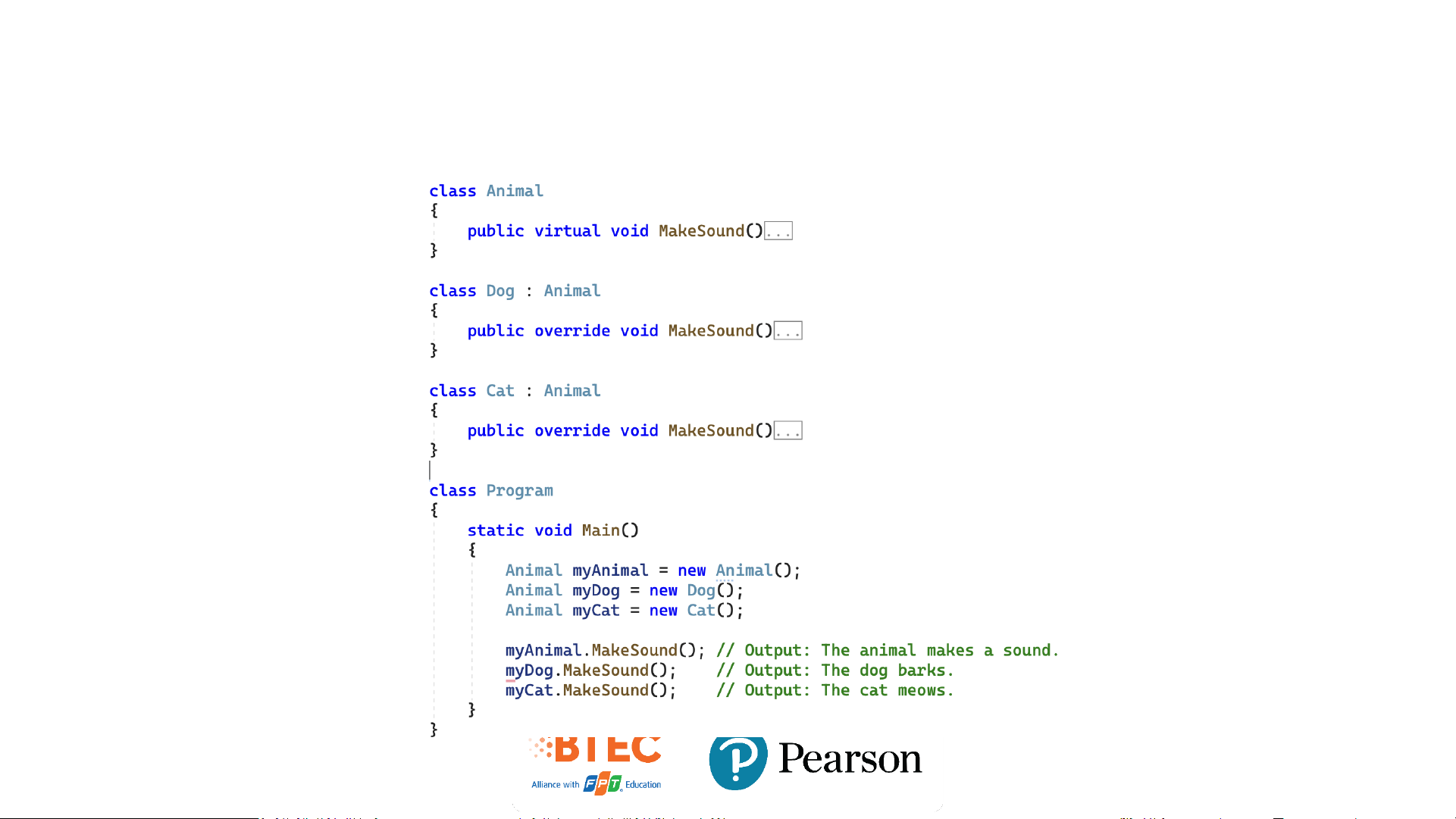

• Polymorphism is an application of pointers to functions.

• Programmers have been using pointers to functions to achieve

polymorphic behavior since Von Neumann architectures were first implemented in the late 1940s

• OO languages may not have given us polymorphism, but they have

made it much safer and much more convenient

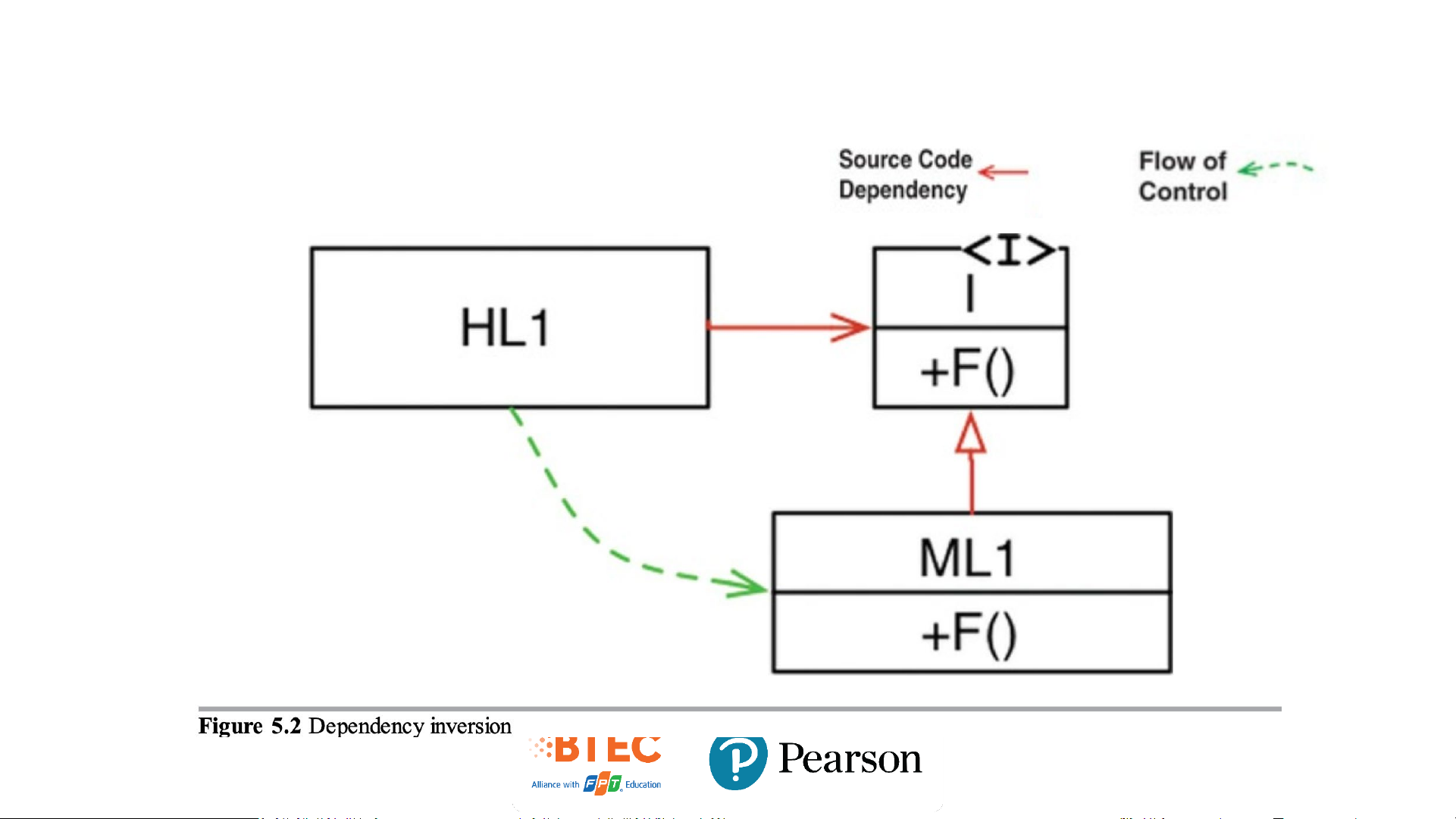

A polymorphism and inheritance example Dependency inversion [1] Martin, R.C. (2017). Dependency inversion [2]

• HL1 calls the F() function in module ML1.

• The fact that it calls this function through an interface is a source

code contrivance. At runtime, the interface doesn’t exist. HL1 simply calls F() within ML1