Preview text:

Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 49 (2019) 120–128

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jretconser

Investigating male consumers’ lifestyle of health and sustainability (LOHAS)

and perception toward slow fashion Jihyun Sunga, Hongjoo Woob,∗

a Consumer and Design Sciences, College of Human Sciences, Auburn University, 368 Spidle Hall, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, 36849, USA

bClothing & Textiles, College of Human Ecology, Yonsei University, Samsung Hall 110, Seodaemun-gu, 50 Yonsei-ro, Seoul, 03722, South Korea A B S T R A C T

Slow fashion indicates the new paradigm of apparel that is made through environmentally, socially, and ethically responsible practices throughout the production

cycle. This study addresses three trends in the current apparel industry, slow fashion, consumer lifestyle of health and sustainability (LOHAS), and growing po-

pulation of fashion-conscious young (Gen-Y) male consumers. The online survey data collected from 306 Gen-Y males revealed the relationships between LOHAS,

decision-making styles, and perceived value toward slow fashion based upon TRA. The findings contribute to the literature by adding empirical evidence of the

emerging trends, as well as generating suggestions for fashion marketers. 1. Introduction

male consumer groups is that previous research has shown that Gen-Y

male consumers, similar to Gen-Y female consumers, are more con-

An increasing number of consumers are becoming conscious about

cerned about global, social, and environmental issues than their older

the environmental issues that may influence their lifestyles, including

counterparts, as they have been exposed to these issues more than

their consumption behaviors (Howard, 2007). The fashion industry has

previous generations (Nayyar, 2001).

recently been paying significant attention to sustainability and ethical

To promote the new paradigm of fashion that considers social and

issues, which has influenced fashion companies to be more aware of

environmental concerns, slow fashion marketers and researchers seek

these issues as well (Moisander and Pesonen, 2002). While the trend-

to identify appropriate target consumer segments and understand their

driven fashion industry is struggling to satisfy consumers’ growing need

needs regarding slow fashion; however, research on consumers' per-

for sustainable apparel (Moisander and Pesonen, 2002), the slow

ceptions of slow fashion and thus how slow fashion could be integrated

fashion movement is obtaining increasing popularity as a potential al-

into the mainstream market is still at the nascent stage. Particularly,

ternative to fast fashion. Slow fashion indicates apparel products that

despite the growing potential of the menswear market described above,

are made through environmentally, socially, and ethically responsible

virtually no researchers have looked into male consumers’ perceived

practices throughout the production cycle, which are typically made

value toward slow fashion, although previous studies have shown that

with the aim of providing basic designs and more durable materials that

men tend to prefer a narrow variety of high quality products that last

last longer at higher prices (Watson and Yan, 2013).

longer (Bakewell et al., 2006), which perfectly aligns with the concept

Concurrently, as another trend in the fashion industry, the men-

of slow fashion. The fact that the menswear market comprises a sig-

swear market is becoming one of the fastest growing sectors in the in-

nificant portion of the industry (Smith, 2016), along with the fact that

dustry due to men's increasing involvement in fashion and clothing

Gen-Y male consumers are interested in pursuing sustainable con-

consumption. Alvarado (2017) found that men's clothing consumption

sumption alternatives (Alvarado, 2017), indicates the need for slow

has continuously increased both in stores and online in recent years,

fashion retailers to specifically target this consumer group.

and projected that consumer demand for men's fashion is expected to

Accordingly, Lifestyle of health and sustainability (LOHAS), which

reach $79.7 billion in 2018, which represents a 1.8% increase from the

describes individuals who value enhancing their lifestyle of health and

current demand. Among consumer segments in the menswear market,

sustainability by purchasing local products and thus helping the en-

Generation Y ([Gen-Y] males born between 1977 and 1994; Bakewell

vironment (Chou et al., 2012), has been a popular consumer trend in

and Mitchell, 2003) are receiving growing attention from marketers as

recent years. Consumers with LOHAS tend to value green living that

they will soon become the major purchasing power in menswear. An

includes organic foods, local produce and healthier products, which

important characteristic distinguishing Gen-Y consumers from other

further influences their family and friends to also adopt sustainable ∗ Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: jihyun.sung@auburn.edu (J. Sung), h_woo@yonsei.ac.kr (H. Woo).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.03.018

Received 18 September 2018; Received in revised form 7 February 2019; Accepted 22 March 2019

0969-6989/ © 2019 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. J. Sung and H. Woo

Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 49 (2019) 120–128

living and healthier lifestyle choices (Howard, 2007), which is a similar

(e.g., Slowfood.com). Similar to the slow food movement, slow fashion concept with slow fashion.

emphasizes the importance of the quality of fashion apparel products

As one of the first studies to address this need, our study investigates

which is made with natural, durable materials, thus enabling consumers

Gen-Y male consumers' perceptions of slow fashion. Specifically, this

to wear clothes for a longer period of time and minimizing the en-

study examines how Gen-Y males' LOHAS and various decision-making

vironmental and social impact of apparel production (Fletcher, 2007).

styles influence their perceived value toward slow fashion.

For example, Alternative Apparel, an online multi-brand retailer, sells

Furthermore, based on the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), this study

fashion apparel and accessories that are produced by meeting the slow

examines whether such perceptions consequently influence Gen-Y

fashion criteria, and provides an outsourcing service connecting en-

males' attitude and purchase intention toward slow fashion. This

vironmental-friendly local garment factories with small retailers

finding will provide practical implications for slow fashion marketers in

(alternativeapparel.com). Everlane, a U.S.-based startup fashion com-

understanding this consumer segment as potential consumers of slow

pany, aims to provide slow fashion products that are made with long-

fashion. The results of this study will reveal Gen-Y males' current per-

lasting designs and eco-friendly materials, thus ultimately minimizing

ceptions and future purchase intention toward slow fashion, and slow

the waste from fast fashion consumption (everlane.com).

fashion researchers and marketers will then understand the influence of

Based on the above, LOHAS and slow fashion both aim to decrease

this particular consumer group's LOHAS and characteristic decision-

the social and environmental impact of consumption by supporting making styles.

products that are consciously and locally made and contribute to the

sustainability of the environment and local communicates. This con- 2. Literature review

nection implies that consumers’ LOHAS, particularly that of Gen-Y

males, would be positively related to their perceptions of slow fashion,

2.1. Lifestyle of health and sustainability (LOHAS) and slow fashion

as consumers with LOHAS are likely to perceive more value in slow

fashion as it addresses their concerns about the environment and so-

As an increasing number of consumers become interested in social

ciety. Thus, H1 was developed as:

and environmental issues related to what they eat and what they wear,

H1. Gen-Y males' lifestyle of health and sustainability (LOHAS)

a new trend describing such conscious lifestyle choices was introduced:

positively influences their perceived value toward slow fashion.

lifestyle of health and sustainability (LOHAS). Consumers with LOHAS

are characterized as valuing quality of life by caring about health and

sustainability, and as a result these consumers prefer environmentally-

2.2. Consumers’ decision-making style

friendly locally-made products that can help sustain their communities

(Chou et al., 2012). More specifically, LOHAS consumers are inclined to

Consumers confront the reality that they need to make decisions

make purchasing decisions which meet their standards for social and

every day from what to wear, what to eat, and what to buy. Consumers

environmental responsibility (Urh, 2015). According to Rudell (2006),

either consciously or unconsciously make daily purchasing decisions,

over 30% of the adult population in the United States were considered

and these decisions are informed by decision-making styles, which re-

to be LOHAS consumers, as they considered environmental and social

fers to “a patterned, mental, cognitive orientation towards shopping

issues when they made purchases.

and purchasing, which consistently dominates the consumer's choices”

As this trend has continued to grow, today one in four adults in the

(Sproles, 1985, p. 79). According to Sproles and Kendall (1986), the

United States are LOHAS consumers (i.e., approximately 41 million

diversity in consumer decision-making styles could be explained by the

people) and they spend $290 billion annually on goods and services,

following eight domains: recreational shopping consciousness, perfec-

which shows how much LOHAS consumers contribute to the market

tionism, brand consciousness, confused by overchoice, fashion con-

(“The era of ethical consumerism”, 2017). Accordingly, companies have

sciousness, price consciousness, impulsive/careless, and habitual/brand

created new market strategies in order to meet LOHAS consumers'

loyal. Specifically, 1) recreational shopping consciousness explains con-

needs and expectations (Urh, 2015). For instance, companies such as

sumers' orientation toward the enjoyable feeling that they can gain

Nike, Coca-Cola, and Starbucks, have begun to emphasize “green

from shopping, which represents consumers' need for adventure and

living” to serve LOHAS consumers’ demand for sustainability-related

leisure while shopping (Sproles and Kendall, 1986). 2) perfectionism, on

products and services (Urh, 2015). As the population of LOHAS con-

the other hand, explains consumers' orientation toward making the best

sumers continues to increase, more and more studies have been pub-

choice, by making decisions based on finding the products with the best

lished aiming to understand the needs and characteristics of LOHAS

quality and value (Sproles and Kendall, 1986). Third, brand conscious-

consumers (e.g., Kim et al., 2013a; Wan and Toppinen, 2016). Despite

ness explains consumers' tendency to make purchasing decisions based

this increase in attention, Gen-Y male consumers and their interest in

on well-known brand names and higher prices (Sproles and Kendall,

LOHAS were largely neglected in these studies.

1986), while 4) confused by overchoice represents consumers' needs for

The trends of sustainability and LOHAS have influenced the fashion

avoiding an overabundance of options in brands/stores that can cause

industry and consumers' criteria around fashion products. More and

confusion, thus hindering decision-making (Sproles and Kendall, 1986).

more consumers have become tired of short-lived fast fashion products

5) fashion consciousness explains consumers' orientation toward the

made with low-quality materials by unsustainable production pro-

latest fashion trends and new styles in decision-making, whereas, 6)

cesses. For a long period of time, fast fashion has exclusively taken

price consciousness refers to their sensitivity toward the price of products

possession of the fashion industry by releasing new styles every week

(Sproles and Kendall, 1986). Lastly, 7) impulsive/careless explains con-

based upon the latest trends, which satisfies consumers' tastes and

sumers' propensity for making spontaneous decisions without much

needs with relatively lower prices (Moisander and Pesonen, 2002).

consideration, while 8) habitual/brand loyal represents consumers' ten-

However, fast fashion has caused serious problems in the environment

dency toward inertia, preferring to shop at the same brands/stores ra-

due to consumers’ over-consumption and waste of fashion apparel

ther than try new places, thus they tended to make repeated purchases

(Fletcher, 2007). Thus, the concept of slow fashion has been introduced

from those specific brands/stores (Sproles and Kendall, 1986). Based

as an alternative to fast fashion. The concept of slow fashion is inspired

upon Sproles and Kendall (1986), we distinguished brand loyalty and

by the slow food movement, which began in Italy in 1986 as a reaction

brand consciousness that brand loyalty is loyalty toward those parti-

to the fast food culture. This movement encourages consumers to

cular favorite brands, while brand consciousness is sensitivity toward

choose local, healthier food made through slow, natural processing

all well-known brand names. For example, with brand loyalty con-

methods, which help sustain both local economies and the environment

sumers make repeated purchases from the same brand. However, brand 121 J. Sung and H. Woo

Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 49 (2019) 120–128

consciousness does not necessarily force them to shop only from the

2.4. Consumers’ attitude, subjective norm, and purchase intention toward

loyal brand but describes their overall high interest in best-selling

slow fashion: Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) brand names.

Previous research on consumer decision-making styles has mostly

The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) is a theoretical framework

investigated female consumers by still treating purchase activity as a

that has been widely utilized in previous literature to investigate the

feminine activity (Bakewell and Mitchell, 2004). However, Bakewell

relationships among attitude, subjective norm, and purchase intention,

and Mitchell (2004) found that a considerable number of male con-

especially in consumer research (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1977). TRA ex-

sumers are highly involved in purchase activities and exhibited a

plains that each individual tends to act in certain ways that generate

variety of decision-making styles that could be further explored. In

favorable feelings and meet other people's expectations simultaneously,

general, researchers found that similar to female consumers, men were

which eventually influences their purchase intention (Ajzen and

often price conscious and they tend to expect higher quality from

Fishbein, 1980; Park, 2000). According to Ajzen and Madden (1986),

products with higher prices (Bakewell and Mitchell, 2004). However,

TRA includes two specific independent factors influencing purchase

even though male consumers’ various decision-making styles guide

intention: attitude toward a behavior and the normative factor. Speci-

their consumption behavior, very little is known about these styles and

fically, attitude toward a behavior refers to the extent to which an in-

how they influence their perceptions of a particular type of consump-

dividual has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation of certain behaviors,

tion trend, such as slow fashion.

while subjective norm determined by an individual's normative beliefs,

As consumer decision-making styles largely guides their perceptions

such as perceptions of normative actions and pressures from society or

of particular products, it is expected that the various dimensions of

other individuals (e.g., family and friends).

decision-making styles of Gen-Y males' would influence their perceived

TRA has been utilized in numerous studies investigating apparel

value toward slow fashion. However, given the scarcity of relevant

products and how individuals' attitude and subjective norm influence

literature on Gen-Y males’ decision-making styles, it is difficult to de-

their purchase intention toward those products (i.e., Belleau et al.,

termine what dimension(s) of decision-making style(s) will be influ-

2007; Marcketti and Shelley, 2009; Yan et al., 2010; Yoh et al., 2003).

ential and how (positively or negatively) these characteristics will in-

Previous researchers have recognized that TRA provides a good ex-

fluence their perceived value toward slow fashion. Thus, H2 was

planation of how consumers' attitude, subjective norm, and purchase

developed in an exploratory form as:

intention are interrelated in the context of introducing a relatively new

product into the fashion market (i.e., slow fashion). Among the limited

H2. Gen-Y males' decision-making styles significantly (either positively

research on green purchasing behavior using TRA as a framework (i.e.,

or negatively) influence their perceived value toward slow fashion.

Ha and Janda, 2012; Minton and Rose, 1997; Paul et al., 2016; Sparks

and Shepherd, 1992), Minton and Rose (1997) found that consumers

who are more involved in environmental-friendly activities avoided

2.3. Consumers’ perceived value toward slow fashion

purchasing products from companies that did not sell environmental-

friendly products. Furthermore, consumers who have a positive attitude

In studying consumers' perceived value toward slow fashion, the

toward green consumption and pursue LOHAS aspects in their lives

concept of perceived value is applied as the dependent variable in the

frequently consumed green products, which further shows the influence

above hypotheses. Consumers' perceived value has been considered as a

of consumers’ general lifestyle choices on their consumption behaviors

significant variable influencing consumers' overall thoughts and atti- (Paul et al., 2016).

tude toward a particular product. Consumers' perceived value refers to

Previous researchers have found that all dimensions (i.e., emotional,

“the consumer's overall assessment of the utility of a product based on

social, price, and quality) of consumers' perceived value toward fashion

perceptions of what is received and what is given” (Zeithaml, 1988, p.

products significantly influence their attitude toward the products in

14). Consumers' perceived value toward a product mainly consists of

question (Chi and Kilduff, 2011). Furthermore, Chi and Kilduff (2011)

four value dimensions: emotional, social, price, and quality value

suggest that when consumers perceive value in certain products, they

(Sweeney and Soutar, 2001). Specifically, 1) emotional value explains

are more willing to choose those products, which demonstrates a po-

consumers' affective feelings that they have toward certain products

sitive relationship between consumers' perceived value and attitude

(Sweeney and Soutar, 2001), and 2) social value explains the self-con-

toward the products. By applying TRA and these findings, this study

cept that individuals generate through the products they use to make a

speculates that Gen-Y males' perceived value toward slow fashion

favorable impression on other individuals (Sweeney and Soutar, 2001).

would likely enhance their attitude toward slow fashion. According to

3) price value explains the perceived costs and value of products, such as

TRA, such attitude will eventually enhance their purchase intention

whether the price of the product is reasonable and provides an appro-

toward slow fashion, as recent research investigating the relationship

priate value for its cost (Sweeney and Soutar, 2001), while 4) quality

between concern for the environment and green purchase intention has

value explains consumers' perceived quality of products, and whether or

found (Chekima et al., 2016). Following TRA, subjective norm is in-

not the quality of the product is satisfactory (Sweeney and Soutar,

cluded, representing how other people's opinions influence Gen-Y 2001).

males' purchase intention and attitude toward slow fashion. Subjective

Understanding consumers' perceived value toward a product is im-

norm regarding slow fashion is expected to enhance purchase intention,

portant because consumers' perceived value forms their attitude and, in

as the more consumers believe that their role models have a positive

turn, purchase intention toward the product (Chi and Kilduff, 2011).

perception of slow fashion, the more likely they would be to purchase

That is, if consumers value the alignment of price and quality of certain

slow fashion products. Thus, H3–H5 were developed as:

products along with their social and emotional value, they are more

H3. Gen-Y males' perceived value toward slow fashion positively

likely to have a favorable attitude toward those products and experi-

influences their attitude toward slow fashion.

ence satisfaction with their purchasing decisions (Chi and Kilduff,

2011). Furthermore, when individuals are more concerned about en-

H4. Gen-Y males' attitude toward slow fashion positively influences

vironmental issues and have intentions to enhance green lifestyles, they

their purchase intention toward slow fashion.

are more likely to value products (i.e., fashion apparel) that are pro-

H5. Gen-Y males' subjective norm toward slow fashion positively

duced in a way that is environmentally, socially and ethically re-

influences their purchase intention toward slow fashion.

sponsible. This supports H1 and H2, which proposes that Gen-Y male

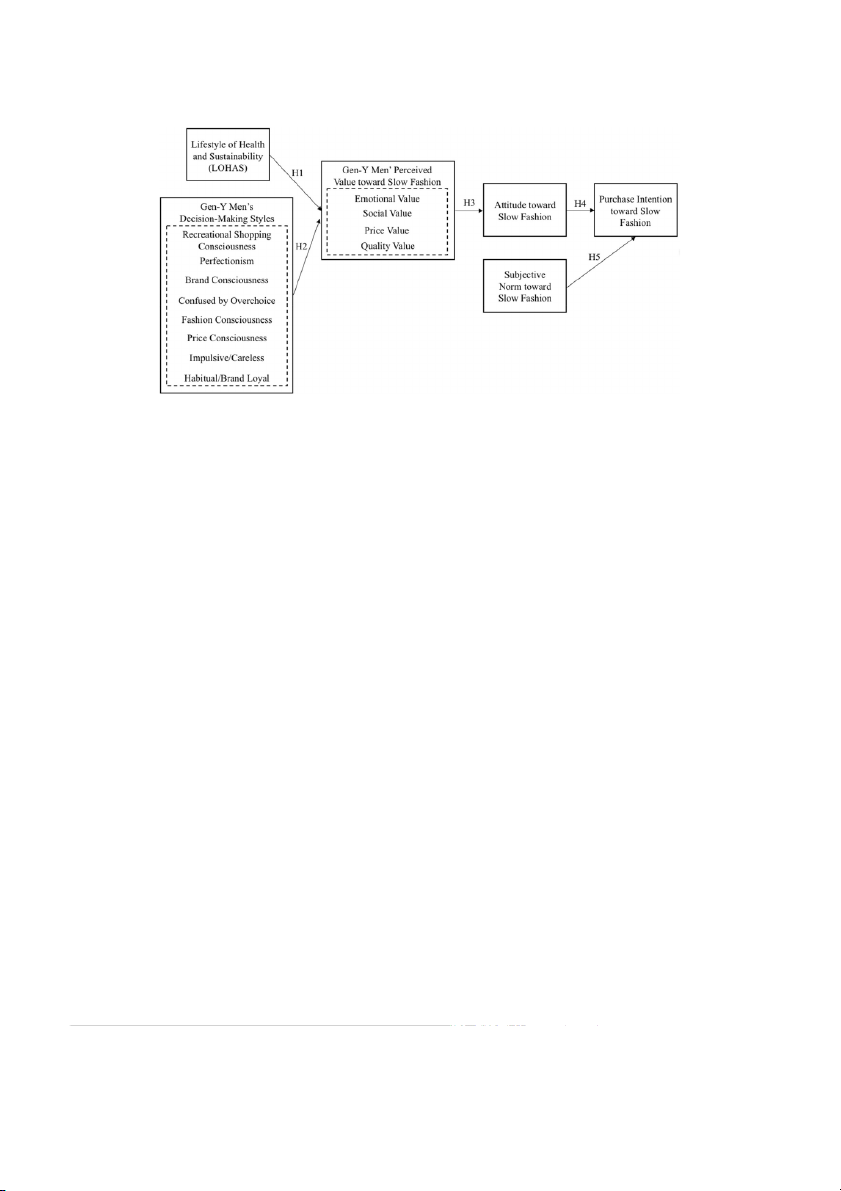

Given these hypotheses developed, the conceptual framework of

consumers’ LOHAS and decision-making styles will significantly influ-

this study is provided as Fig. 1.

ence their perceived value toward slow fashion. 122 J. Sung and H. Woo

Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 49 (2019) 120–128

Fig. 1. Research framework. 3. Methods

by reliability tests. Factor loadings lower than 0.50 and eigen values

lower than 1.00 were eliminated from further analysis. The results of

3.1. Sample and data collection

the EFAs showed that LOHAS, attitude toward slow fashion, subjective

norm, and purchase intention toward slow fashion were unidimen-

Upon receiving an Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval on

sional. Gen-Y male participants' decision-making styles were revealed

ethical research compliance for human subjects, a total of 330 males

as having eight factors (i.e., recreational shopping consciousness, per-

born between 1977 and 1994 (i.e., Gen-Y group) and currently living in

fectionism, brand consciousness, confused by overchoice, fashion con-

the United States participated in the survey (Bakewell and Mitchell,

sciousness, price consciousness, impulsive/careless, and habitual/brand

2003). An online survey questionnaire was created in Qualtrics and

loyal decision-making style), after excluding five items that had factor

distributed through the Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) platform to

loadings lower than 0.50 (see Table 1). As quality value and emotional

recruit a diverse male population from the United States. Only the

value were merged into one factor through EFA, perceived value to-

participants who met the age (i.e., born between 1977 and 1994) and

ward slow fashion ultimately consisted of three factors (i.e., quality/

gender (i.e., male) criteria were able to participate in the online survey,

emotional, social, and price) (see Table 2). The reliability of the mea-

and there was a $.50 incentive for each person who completed the

sures was all acceptable, with Cronbach's α values ranging from 0.63 to

survey questionnaire after receiving the approval of the researcher. 0.94 (see Tables 1 and 2). 3.2. Measures 4. Results

The measures of lifestyle of health and sustainability (LOHAS), the

After eliminating unusable data, 306 responses were utilized for

Gen-Y male participants' decision-making styles, their perceived value

further analysis. Descriptive statistics showed that the respondents' age

toward slow fashion, attitude toward slow fashion, subjective norm,

ranged from 24 to 41 (i.e., born between 1977 and 1994). The ethnicity

and purchase intention toward slow fashion were all included in the

of the participants was varied, showing that majority of them were

survey questionnaire, followed by demographic information (i.e.,

Caucasian (nearly 70%), followed by Asian American, Hispanic, African

gender, birth year, ethnicity, education level, annual income, and state

American, Mixed Race and Other. In terms of their education level,

of residence). The measurement scales were adapted from previous

approximately 57% of the participants reported that they had a ba-

research. The LOHAS scale was adapted from Kim et al. (2013b), the

chelor's degree, 30% had high school or less, 9% had a professional

measurement for consumer decision-making styles was adapted from

degree, 6% had a master's degree, and only 3% had a doctorate degree.

Sproles and Kendall (1986), and consumers’ perceived value toward

The participants' income level was also varied from $19,999 or less to

slow fashion was measured with the perceived value scale modified

$100,000 or above (see Table 3).

from Sweeney and Soutar (2001). The scales were measured according

The results of the simple regression analysis, testing the relationship

to a seven-point Likert-type scale, ranging from “1 = strongly disagree”

between LOHAS and each of the three dimensions of Gen-Y males'

to “7 = strongly agree.” To measure attitude toward slow fashion, a

perceived value toward slow fashion (H1), showed that LOHAS sig-

seven-point semantic differential scale was adapted from Han et al.

nificantly influenced all dimensions of Gen-Y males’ perceived value

(2010), anchored by “1 = extremely bad” to “7 = extremely good.”

toward slow fashion. Specifically, LOHAS positively influenced the

Subjective norm was measured with three items adopted from Yoh et al.

perceived quality/emotional value of slow fashion (β = 0.30, t = 5.56,

(2003), anchored by “1 = highly unlikely” to “7 = highly likely,” while

p < .001), perceived price value of slow fashion (β = 0.31, t = 5.60,

purchase intention toward slow fashion clothing was measured with

p < .001), and perceived social value of slow fashion (β = 0.21,

three items, ranging from “1 = not at all” to “7 = very much” (Kim

t = 3.66, p < .001). In terms of relative prediction power (β coefficient et al., 2013b).

values), LOHAS showed a similar prediction power across the three

Prior to testing our hypotheses, exploratory factor analyses (EFA)

value dimensions ranging from 0.21 to 0.31 (see Table 4).

was conducted using principal component analysis and varimax rota-

The results of a series of multiple regression analyses testing the

tion to confirm the dimensionality of each scale measurement followed

relationship between Gen-Y males' eight decision-making styles and 123 J. Sung and H. Woo

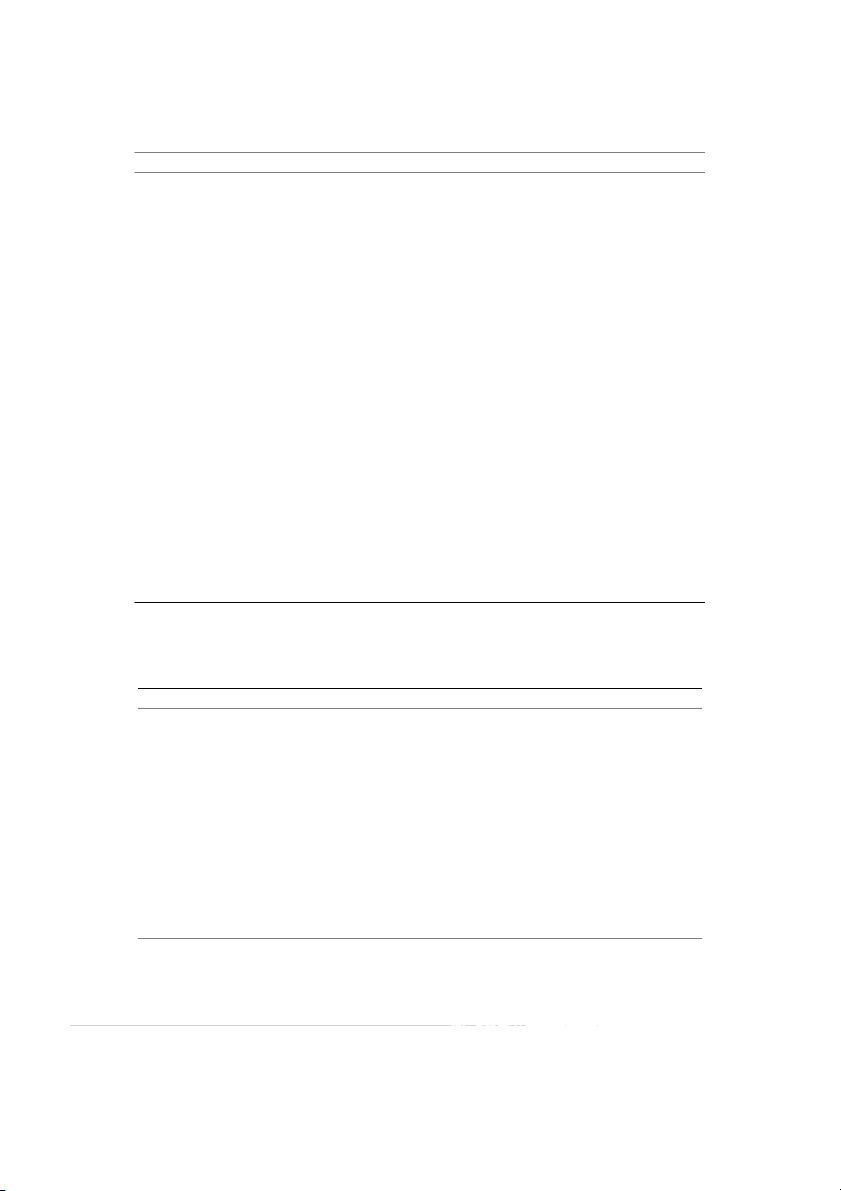

Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 49 (2019) 120–128 Table 1

Results of the EFA on Gen-Y males’ decision-making styles. Items Item Loading Cronbach's α

Factor 1: Recreational Shopping Consciousness .88

Shopping is not a pleasant activity. .82

Shopping in different stores is a waste of time. .77

Shopping is very enjoyable to me. .75 I enjoy shopping just for fun. .73

It's fun to buy something new and exciting. .56 Factor 2: Perfectionism .88

I make a special effort to choose the very best quality products. .83

In general, I usually try to buy the best overall quality. .82

Getting good quality is very important to me. .82

I have very high standards and expectations for the products I buy. .80

Factor 3: Brand Consciousness .82

The most advertised brands are usually good choices. .76

The higher the price of the product, the better the quality. .74

I prefer buying the best-selling brands. .73

I usually buy well-known brands. .72

Good quality department stores and specialty stores offer the best. .71

Factor 4: Confused by Overchoice .89

I am confused by all the information on different products. .85

The more I learn about products, the harder it seems to choose the best. .85

There are so many brands to choose from that I often feel confused. .83

Sometimes it's hard to decide in which stores to shop. .76

Factor 5: Fashion Consciousness .88

I usually have at least one outfit of the newest style. .82

I keep my wardrobe up to date with the changing fashions. .79

Fashionable, attractive styling is very important to me. .75

For variety I shop in different stores and buy different brands. .57

Factor 6: Price Consciousness .63

I usually buy the lower priced products. .70

I buy as much as possible at sale price. .65

I look very carefully to find the best value for money. .48

Factor 7: Impulsive/Careless .73

I often make purchases I later wish I had not. .73

I frequently purchase on impulse. .71

I should spend more time deciding on the products I buy. .62

I carefully watch how much I spend. .58

Factor 8: Habitual/Brand Loyal .68

When I find a brand I like, I buy it regularly. .78

I have favorite brands I buy every time. .70

I go to the same store each time I shop. .56

Note. All numbers are rounded up to two decimal places. Table 2

Results of the EFA on Gen-Y males’ perceived value toward slow fashion. Items Item Loading Cronbach's α

Factor 1: Quality/Emotional Value .91

Slow fashion clothing has consistent quality. .78

Slow fashion clothing is well made. .75

Slow fashion clothing would not last a long time. .75

Slow fashion clothing has poor workmanship. .73

Slow fashion clothing has an acceptable standard of quality. .69

Slow fashion clothing is one that I would feel relaxed about using. .66

Slow fashion clothing would perform consistently. .65

Slow fashion clothing is one that I would enjoy. .65

Slow fashion clothing would make me want to use it. .63

Slow fashion clothing would make me feel good. .59 Factor 2: Social Value .91

Slow fashion clothing would improve the way I am perceived. .90

Slow fashion clothing would make a good impression on other people. .87

Slow fashion clothing would give its owner social approval. .86

Slow fashion clothing would help me to feel acceptable. .80 Factor 3: Price Value .88

Slow fashion clothing is reasonably priced. .83

Slow fashion clothing would be economical. .82

Slow fashion clothing is a good product for the price. .80

Slow fashion clothing offers value for money. .79

Note. All numbers are rounded up to two decimal places. 124 J. Sung and H. Woo

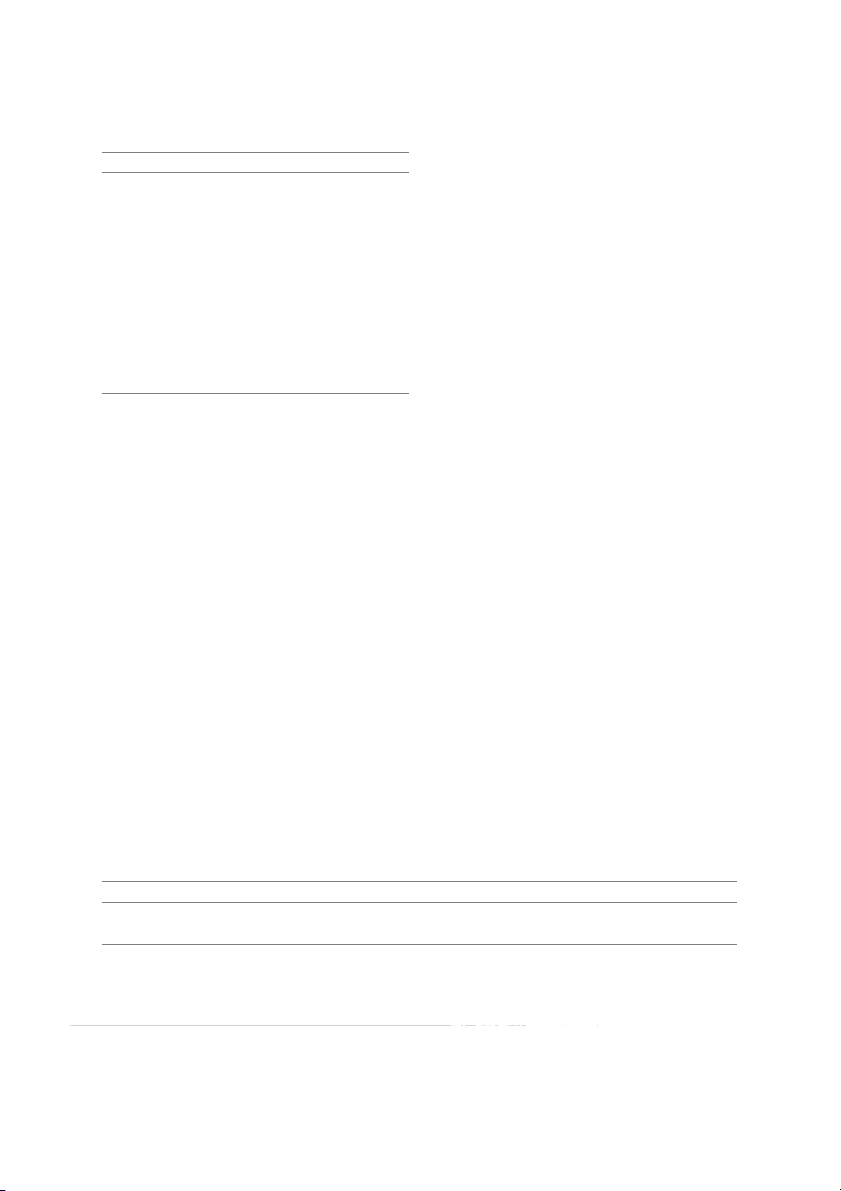

Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 49 (2019) 120–128 Table 3

supported. Furthermore, the results of H5, testing the relationship be-

Descriptive statistics of the Gen-Y male participants (N = 306).

tween subjective norm and purchase intention toward slow fashion,

showed that Gen-Y males’ subjective norm toward slow fashion also Variable Category Frequency Percentage (%)

significantly enhanced their purchase intention toward slow fashion Age 24–29 111 36.2

(β = .63, t = 14.12, p < .001), supporting H5 (see Table 6). 30–35 108 35.3 36–41 87 28.4 5. Discussion Ethnicity Caucasian 209 68.3 Asian American 42 13.7 Hispanic 16 5.2

This study provides unique insight for both the academic literature African American 15 4.9

and slow fashion marketers, by showing how Gen-Y male consumers' Other 15 4.9

LOHAS and various decision-making styles influence their perceived Mixed Race 9 2.9 Education High school or less 78 25.5

value toward slow fashion. For instance, the current study found that Bachelor's degree 173 56.5

Gen-Y male consumers who pursue LOHAS perceive that slow fashion is Master's degree 19 6.2

high quality, which makes them feel good about consuming these Professional degree 28 9.2

products (i.e., quality/emotional value), provides economic merit by Doctorate degree 8 2.6

purchasing a few items that last longer (i.e., price value), and helps Income $19,999 or less 51 16.7 $20,000 to $39,999 66 21.6

them make a favorable impression on others (i.e., social value). This $40,000 to $59,999 85 27.8

result corresponds to our assumption based on the common core values $60,000 to $79,999 50 16.3

expressed by both LOHAS and slow fashion, as Gen-Y males’ concerns $80,000 to $99,999 31 10.1

about the environment, sustainability, and local communities (LOHAS) $100,000 or above 23 7.5

(Howard, 2007) supports the concept of slow fashion, thus enhancing its value (Joergens, 2006).

In addition, the results of this study revealed which domains of Gen-

Y males' decision-making styles either positively or negatively related

their perceived value toward slow fashion (H2), showed that several

with each dimension of perceived value toward slow fashion, and which

domains of Gen-Y male consumers’ decision-making styles significantly

dimensions more or less strongly influenced their perceived value to-

influenced their perceived value toward slow fashion. Specifically, the

ward slow fashion. For example, for the quality/emotional value of

quality and emotional value of slow fashion was positively influenced

slow fashion, Gen-Y males' decision-making styles oriented toward

by perfectionism (β = 0.26, t = 4.49, p < .001) and price conscious-

choosing higher quality products (i.e., perfectionism) and price con-

ness (β = 0.17, t = 2.90, p < .001), negatively influenced by impulsive

sciousness drove them to perceive a higher quality/emotional value

style (β = −0.30, t = −4.95, p < .001), and positively influenced by

from slow fashion: which is more durable and could last longer, thus

habitual style (β = 0.14, t = 2.27, p = .02). For the price value of slow

possibly being more cost-saving in the long-term and giving them

fashion, only perfectionism was a significantly positive predictor

contentment from making a wise decision. Also, Gen-Y males' habitual/

(β = 0.30, t = 4.84, p < .001). Both perfectionism (β = 0.19, t = 3.08,

brand loyal tendencies enhanced their perceived quality/emotional

p < .001) and fashion consciousness (β = 0.17, t = 2.27, p = .02)

value of slow fashion, because slow fashion can satisfy their need for

positively influenced the social value of slow fashion. There were no

habitual/brand loyal in their product choices. For instance, as com-

multicollinearity issues throughout the analyses, as the variance infla-

pared to fast fashion, slow fashion provides a relatively fixed selection

tion factor (VIF) indicated values greater than 1.00 (see Table 5).

of products with consistent design and quality, and thus male con-

To test H3, H4, and H5, a set of multiple regression and simple

sumers with habitual/brand loyal can repeatedly purchase quality

regression analyses were conducted. For H3, the results of the multiple

products from the slow fashion brands that they like instead of being

regression analysis testing the relationships between Gen-Y males'

overwhelmed by a variety of choices in quick rotation (e.g., fast

perceived value toward slow fashion and their attitude toward slow

fashion). However, Gen-Y males’ impulsive/careless side of decision-

fashion, showed that all three dimensions of perceived value (i.e.,

making style decreased their perceived value toward slow fashion. The

quality/emotional, price, and social value) significantly increased Gen-

result could be because the slow-moving cycle of slow fashion conflicts

Y males' attitude toward slow fashion, supporting H4. More specifically,

with the impulsive side of their decision-making style; thus, the im-

comparing β coefficient values, the quality/emotional value of slow

pulsive/careless dimension was negatively associated with the per-

fashion significantly enhanced Gen-Y males’ attitude toward slow

ceived quality/emotional value of slow fashion.

fashion (β = 0.39, t = 9.28, p < .001) the most, followed by price

In terms of the price value of slow fashion, Gen-Y males' perfec-

value (β = 0.35, t = 8.63, p < .001) and social value (β = 0.27,

tionism had a noticeably positive influence on their perceived price

t = 6.83, p < .001). There was no multicollinearity issue detected in

value toward slow fashion. Gen-Y male consumers who have a desire to

the analysis based on the VIF values being greater than 1.00.

purchase the best quality of products that could be used for a long

For H4, the results of the simple regression analysis testing the re-

period of time found higher value in the price value of slow fashion,

lationship between Gen-Y males' attitude toward slow fashion and

because they are aware of the long-term cost benefits of consuming

purchase intention toward slow fashion, showed that their attitude

slow fashion products. In terms of the social value of slow fashion,

toward slow fashion significantly increased their purchase intention

again, perfectionism enhanced Gen-Y male consumers' perceived social

toward slow fashion (β = .77, t = 21.27, p < .001). Thus, H4 was

value of slow fashion, which might be because males who pursue social Table 4

Results of testing H1: Influence of LOHAS on perceived value toward slow fashion. Independent Variable Dependent Variable R2 F β t p LOHAS

Quality/emotional value of slow fashion .09 30.96 .30 5.56 .00*** Price value of slow fashion .09 31.37 .31 5.60 .00*** Social value of slow fashion .04 13.40 .21 3.66 .00***

Note. ∗p < .05, ∗∗p < .01, ∗∗∗p < .001, all numbers are rounded up to two decimal places. 125 J. Sung and H. Woo

Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 49 (2019) 120–128 Table 5

Results of testing H2: The influence of Gen-Y males’ decision-making styles on their perceived value toward slow fashion. Independent Variable Dependent Variable R2 F β t p VIF Decision-Making Styles

→ Quality/Emotional Value of SlowFashion .24 11.46

Recreational Shopping Consciousness .03 .46 .65 1.67 Perfectionism .26 4.49 .00*** 1.29 Brand Consciousness .02 .35 .73 1.29 Confused by Overchoice -.03 -.48 .64 1.38 Fashion Consciousness -.03 -.37 .71 1.85 Price Consciousness .17 2.90 .00*** 1.27 Impulsive/Careless -.30 −4.95 .00*** 1.41 Habitual/Brand Loyal .14 2.27 .02* 1.47 Decision-Making Styles

→ Price Value of Slow Fashion .11 4.74

Recreational Shopping Consciousness -.09 −1.29 .20 1.67 Perfectionism .30 4.84 .00*** 1.29 Brand Consciousness .11 1.75 .08 1.29 Confused by Overchoice -.03 -.53 .59 1.38 Fashion Consciousness .09 1.27 .21 1.85 Price Consciousness .07 1.15 .25 1.27 Impulsive/Careless .02 .34 .73 1.41 Habitual/Brand Loyal -.06 -.90 .37 1.47 Decision-Making Styles

→ Social Value of Slow Fashion .15 6.68

Recreational Shopping Consciousness -.08 −1.22 .22 1.67 Perfectionism .19 3.08 .00*** 1.29 Brand Consciousness .10 1.65 .10 1.29 Confused by Overchoice .05 .81 .42 1.38 Fashion Consciousness .17 2.27 .02* 1.85 Price Consciousness .06 .93 .36 1.27 Impulsive/Careless .03 .40 .69 1.41 Habitual/Brand Loyal .11 1.69 .09 1.47

Note. ∗p < .05, ∗∗p < .01, ∗∗∗p < .001, all numbers are rounded up to two decimal places.

approval and self-enhancement from their peers perceived that slow

and Janda, 2012; Paul et al., 2016; Yan et al., 2010), the findings of this

fashion could meet such needs by showing that they had made the right

current study confirmed that Gen-Y males' positive attitude toward slow

decision in consuming socially desirable products. Additionally, Gen-Y

fashion, formed by their perceived value, eventually increased their

males' fashion conscious decision-making styles enhanced the social

purchase intention toward slow fashion. Furthermore, Gen-Y male

value of slow fashion for them. This may be because slow fashion is a

consumers’ perceptions about how other individuals (e.g., friends and

recent trend, thus the subjects’ fashion consciousness increased the

family members) would support the idea of slow fashion (subjective

social value of slow fashion, which could lead to them being perceived

norm) enhanced their purchase intention toward slow fashion. This

as early adopters of this emerging trend.

shows that the perceived value of slow fashion can eventually cause

Some domains of Gen-Y males’ decision-making styles (i.e., recrea-

consumers to have a favorable attitude and purchase intention toward

tional shopping consciousness, brand consciousness, and confused by slow fashion.

overchoice) did not significantly influence any dimensions of perceived

In conclusion, the findings of this study demonstrate that Gen-Y male

value toward slow fashion in the current study. Considering the concept

consumers’ LOHAS and decision-making styles can either enhance or de-

of slow fashion (e.g., higher quality and price, and environmentally/

crease their perceived value in slow fashion, which eventually influences

socially conscious products), males who view shopping as a fun activity

their attitude and purchase intention toward slow fashion. Each individual

(recreational shopping consciousness) or seek popular brand names

has different lifestyle considerations, including concerns about the en-

(brand consciousness) might not have necessarily found value in slow

vironment and general decision-making styles, which are eventually

fashion. Males who are stressed out by an overchoice of brands or stores

guided by the various perceptions toward slow fashion. Implications for

(confused by overchoice) might have perceived slow fashion as another

researchers and slow fashion retailers along with suggestions for future

new alternative that they need to consider, thus not finding it very

research are discussed in the next section.

attractive. Overall, our findings show that Gen-Y males find different

value dimensions in slow fashion depending upon their various deci-

6. Implications, limitations, and suggestions for future studies sion-making styles.

Supporting previous literature, which found a relationship among

Academically, this study contributes to the slow fashion literature

consumers' attitude, subjective norm, and purchase intention (e.g., Ha

by adding empirical evidence about the importance of consumers' Table 6

Results of testing H3, H4, and H5. Independent Variable Dependent Variable R2 F β t p VIF

Perceived value toward slow fashion

→ Attitude toward Slow Fashion .63 171.18 Quality/emotional value .39 9.28 .00*** 1.44 Price value .35 8.63 .00*** 1.28 Social value .27 6.83 .00*** 1.32 Attitude toward slow fashion

→ Purchase intention toward Slow Fashion .60 452.44 .77 21.27 .00*** Subjective Norm

→ Purchase intention toward Slow Fashion .40 199.26 .63 14.12 .00***

Note. ∗p < .05, ∗∗p < .01, ∗∗∗p < .001, all numbers are rounded up to two decimal places. 126 J. Sung and H. Woo

Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 49 (2019) 120–128

lifestyles (e.g., LOHAS) and decision-making styles in understanding

encompassing the other types of consumer behaviors against over-

their perceived value, attitude, and purchase intention toward slow consumption.

fashion, which we found to be particularly true for Gen-Y male con-

sumers. As the current study is nearly the first and only study to analyze Financial Disclosure

Gen-Y male consumers' multi-dimensional decision-making styles in

depth, and which examined this particular group's perceptions toward Not Applicable.

slow fashion, the findings of this study provide a deeper body of

knowledge for the literature on decision-making styles, and niche in- Declaration

formation about male consumers for the slow fashion literature.

As our findings showed that several characteristic dimensions of

• This manuscript is not submitted to anywhere else.

Gen-Y males’ decision-making styles are positively related to their

• This research did not receive any external funding.

perceptions toward slow fashion and, further, increase their positive

• This research does not involve any conflict of interest.

attitude and purchase intention toward slow fashion, this study high-

lights that Gen-Y male consumers could be one of the potential target References

markets for the slow fashion industry. Specifically, fashion marketers

and retailers could utilize the findings of this study to identify which

Ajzen, I., Fishbein, M., 1977. Attitude-behavior relations: a theoretical analysis and re-

types of consumers (based on their decision-making styles) perceive

view of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 84 (5), 888–918.

more positive value in slow fashion. As the findings have revealed that

Ajzen, I., Fishbein, M., 1980. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour.

Ajzen, I., Madden, T.J., 1986. Prediction of goal-directed behavior-attitudes, intentions,

Gen-Y male consumers who are concerned about the environment more

and perceived behavioral-control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 22 (5), 453–474.

positively value slow fashion, slow fashion marketers could target Gen-

Alvarado, J., 2017, January 20. Millennial Men Increase Sales Revenues for Menswear

Y male consumers who are interested in environmental and social is-

Apparel by 64%. Linkedin. Retrieved from. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/

millennial-men-increase-sales-revenues-menswear-apparel-alvarado/. sues.

Bakewell, C., Mitchell, V.W., 2003. Generation Y female consumer decision-making

In addition, as Gen-Y males’ perfectionism, price consciousness, and

styles. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 31 (2), 95–106.

habitual/brand loyal sides of their decision-making styles enhanced

Bakewell, C., Mitchell, V.W., 2004. Male consumer decision-making styles. Int. Rev.

Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 14 (2), 223–240.

their perceived value toward slow fashion, slow fashion marketers

Bakewell, C., Mitchell, V.W., Rothwell, M., 2006. UK Generation Y male fashion con-

could focus on communicating the merits of slow fashion as a wise

sciousness. J. Fash. Mark. Manag.: Int. J. 10 (2), 169–180.

decision, saving money in the long-term, and offering consistent quality

Belleau, B.D., Summers, T.A., Xu, Y., Pinel, R., 2007. Theory of reasoned action purchase

intention of young consumers. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 25 (3), 244–257.

to meet this need. The findings that showed the positive influence of the

Chekima, B., Wafa, S.A.W.S.K., Igau, O.A., Chekima, S., Sondoh Jr., S.L., 2016. Examining

perceived value of slow fashion on attitude toward slow fashion, and

green consumerism motivational drivers: does premium price and demographics

eventually, on purchase intention, further confirm that it is crucial for

matter to green purchasing? J. Clean. Prod. 112, 3436–3450.

Chi, T., Kilduff, P.P., 2011. Understanding consumer perceived value of casual sports-

slow fashion marketers to expose Gen-Y male consumers to slow fashion

wear: an empirical study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 18 (5), 422–429.

products and realize the positive value of slow fashion in order for them

Chou, C.J., Chen, K.S., Wang, Y.Y., 2012. Green practices in the restaurant industry from

to develop favorable attitude and purchase intention toward slow

an innovation adoption perspective: evidence from Taiwan. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 31

fashion products. Therefore, overall, slow fashion marketers and re- (3), 703–711.

Fletcher, K., 2007. Slow fashion. Ecologist 37 (5), 61.

tailers should provide comprehensive information on the positive sides

Ha, H.Y., Janda, S., 2012. Predicting consumer intentions to purchase energy-efficient

of slow fashion products (i.e., longer lasting quality, and environ-

products. J. Consum. Mark. 29 (7), 461–469.

mental/social/ethical aspects of products) for those who are interested

Han, H., Hsu, L.T.J., Sheu, C., 2010. Application of the theory of planned behavior to

green hotel choice: testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tourism

in buying these products, which will possibly result in an increase in the Manag. 31 (3), 325–334.

sale of slow fashion products among young male consumers.

Howard, B., 2007. LOHAS consumers are taking the world by storm. Total Health 29

Although the findings of this study contribute to the slow fashion (3), 58.

Joergens, C., 2006. Ethical fashion: myth or future trend? J. Fash. Mark. Manag.: Int. J. 10

literature and help fashion marketers and retailers develop effective (3), 360–371.

marketing strategies for Gen-Y male consumers, there are several lim-

Kim, M.J., Lee, C.K., Gon Kim, W., Kim, J.M., 2013a. Relationships between lifestyle of

itations to this study and suggestions for future research. First, this

health and sustainability and healthy food choices for seniors. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 25 (4), 558–576.

study only investigated the Gen-Y cohort of male consumers, which

Kim, H., Jung Choo, H., Yoon, N., 2013b. The motivational drivers of fast fashion

consists of males who were born between 1977 and 1994. Although this

avoidance. J. Fash. Mark. Manag.: Int. J. 17 (2), 243–260.

decision was made based on the recent growth of the Gen-Y men's

Marcketti, S.B., Shelley, M.C., 2009. Consumer concern, knowledge and attitude towards

counterfeit apparel products. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 33 (3), 327–337.

fashion market, to better represent male consumers in the market, fu-

Minton, A.P., Rose, R.L., 1997. The effects of environmental concern on environmentally

ture studies may look into older male consumers who may have dif-

friendly consumer behavior: an exploratory study. J. Bus. Res. 40 (1), 37–48.

ferent decision-making styles and degrees of interest in social and en-

Moisander, J., Pesonen, S., 2002. Narratives of sustainable ways of living: constructing

the self and the other as a green consumer. Manag. Decis. 40 (4), 329–342.

vironmental issues. In addition, this study examined male individuals

Nayyar, S., 2001. Inside the mind of Gen Y. Am. Demogr. 23 (9), 6.

who were recruited using the MTurk system. However, these findings

Park, H.S., 2000. Relationships among attitudes and subjective norms: testing the theory

might have been more intriguing if the study recruited men who are

of reasoned action across cultures. Commun. Stud. 51 (2), 162–175.

highly interested in and familiar with fashion products, because these

Paul, J., Modi, A., Patel, J., 2016. Predicting green product consumption using theory of

planned behavior and reasoned action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 29, 123–134 March.

consumers might already be exposed to the concept of slow fashion and

Rudell, F., 2006. Shopping with a social conscience: consumer attitudes toward sweat-

aware of its pros and cons, which might have resulted in different in-

shop labor. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 24 (4), 282–296.

sights about males' thoughts toward slow fashion. Also, although a set

Smith, K., 2016, June. Spring 2017 Menswear: Market Growth & Trends. Retrieved from.

https://edited.com/blog/2016/06/menswears-magic-moment/.

of regression analysis was used in the current study, future studies may

Sparks, P., Shepherd, R., 1992. Self-identity and the theory of planned behavior: assessing

consider testing the model across diverse consumer markets, such as

the role of identification with" green consumerism. Soc. Psychol. Q. 388–399.

through structural equation modeling (SEM), to increase the general-

Sproles, G.B., 1985. From perfectionism to fadism: measuring consumers' decision-

making styles. In: Proceedings, American Council on Consumer Interests, vol. 31. pp.

izability of the model. Taken together, it is suggested that future re- 79–85 (Columbia).

search expand the scope of the current study to include a variety of

Sproles, G.B., Kendall, E.L., 1986. A methodology for profiling consumers' decision‐

male consumer groups using this study as a steppingstone, to bring in

making styles. J. Consum. Aff. 20 (2), 267–279.

Sweeney, J.C., Soutar, G.N., 2001. Consumer perceived value: the development of a

wider practical implications for fashion retailers who are attempting to

multiple item scale. J. Retail. 77 (2), 203–220.

promote slow fashion in the United States and beyond. Furthermore,

The era of ethical consumerism is here: How to market to LOHAS consumers, 2017, July

future research could be expanded toward a wider scope of anti-con-

21. Ethos. Retrieved from. http://blog.ethos-marketing.com/blog/how-to-market-

sumerism, not only including the current trend of LOHAS but also to-lohas. 127 J. Sung and H. Woo

Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 49 (2019) 120–128

Urh, B., 2015. Lifestyle of health and sustainability-the importance of health conscious-

Zeithaml, V.A., 1988. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end

ness impact on LOHAS market growth in ecotourism. Quaestus (6), 167–177.

model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 52 (3), 2–22.

Wan, M., Toppinen, A., 2016. Effects of perceived product quality and Lifestyles of Health

and Sustainability (LOHAS) on consumer price preferences for children's furniture in

Jihyun Sung is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Consumer and Design Sciences at

China. J. For. Econ. 22, 52–67 January.

Auburn University. Her current research interest includes the area of appearance man-

Watson, M., Yan, R.N., 2013. An exploratory study of the decision processes of fast versus

agement behavior and clothing-related behavior based on consumer theories.

slow fashion consumers. J. Fash. Mark. Manag.: Int. J. 17 (2), 141–159.

Yan, R.N., Ogle, J.P., Hyllegard, K.H., 2010. The impact of message appeal and message

source on Gen Y consumers' attitudes and purchase intentions toward American

Hongjoo Woo is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Clothing & Textiles at Yonsei

Apparel. J. Mark. Commun. 16 (4), 203–224.

University, South Korea. Her research interest lies in fashion retailing, retail business

Yoh, E., Damhorst, M.L., Sapp, S., Laczniak, R., 2003. Consumer adoption of the Internet:

management, and innovative fashion business/startup models.

the case of apparel shopping. Psychol. & Mark. 20 (12), 1095–1118. 128