Preview text:

Journal of Global Fashion Marketing Bridging Fashion and Marketing

ISSN: 2093-2685 (Print) 2325-4483 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rgfm20

Why do consumers choose sustainable fashion? A

cross-cultural study of South Korean, Chinese, and Japanese consumers Hyun Min Kong & Eunju Ko

To cite this article: Hyun Min Kong & Eunju Ko (2017) Why do consumers choose sustainable

fashion? A cross-cultural study of South Korean, Chinese, and Japanese consumers, Journal of

Global Fashion Marketing, 8:3, 220-234, DOI: 10.1080/20932685.2017.1336458

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2017.1336458 Published online: 12 Jun 2017.

Submit your article to this journal Article views: 9 View related articles View Crossmark data

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rgfm20

Download by: [The UC San Diego Library] Date: 24 June 2017, At: 03:40

Journal of Global fashion MarketinG, 2017 Vol. 8, no. 2, 220–234

https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2017.1336458

Why do consumers choose sustainable fashion?

A cross-cultural study of South Korean, Chinese, and Japanese consumers Hyun Min Kong and Eunju Ko

Department of Clothing and textiles, Yonsei university, seoul, republic of korea ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY

This research aims to study consumers in South Korea, China, received 24 March 2017

and Japan to better understand their decision-making processes revised2 april 2017

regarding sustainable fashion, an area where demands are increasing accepted25 May 2017

for countering negative environmental impacts. Consumers KEYWORDS

sometimes fail to align their behavior with their positive attitudes Consumer decision-making;

toward sustainable consumption. In addition, they have cross- cross-cultural studies; eWoM

cultural differences in their attitudes and eWOM intentions toward intention; sustainable

sustainable fashion products (SFP). This study (1) investigates whether consumption; sustainable

environmental concerns and product knowledge of SFP may increase fashion

SFP purchasing, (2) identifies factors influencing eWOM intentions, 关键词

and (3) investigates marketing approaches and cross-cultural

消费者决策; 跨文化研究;

differences in the SFP context. Findings suggest that consumers have 网路口碑 (eWoM);

positive attitudes toward SFP when they perceive that the products

可持续消费; 可持续时尚

have value but not when they perceive risks. The research gives

marketing insights into methods for enhancing sustainable fashion consumption.

消费者为什么选择可持续时尚

关于韩国 中国 日本 ? , ,

消费者的跨文化研究

此研究旨在探索韩国、中国和日本消费者的可持续时尚的消费者 决策过程

由于时尚行业对环境的负面影响 消费者对绿色制造 。 , 的需求有所增加 近年来

时尚制造商认识到时尚消费一个关键 。 , 问题

因为时尚消费和供应链通过使用有毒染料和水污染产生的 ,

碳排放对环境造成显著的负面影响 因此 为了确保时尚产品的 。 , 可持续发展

时尚产业已经开始了一系列的生态和伦理运动 , 。

公司为了未来的成功需要更好地了解消费者的行为和对可持 续的态度 然而

消费者往往对选择可持续的时尚产品谨慎 。 , ,并

不总是与他们对可持续消费的积极态度保持一致 有绿色意识的 。

消费者表示愿意参与环境消费

不过却很少购买可持续服装 , 。许

多研究人员试图解释生态友好态度与行为之间的差距 但却未能 ,

提供明确的答案来解释可持续发展的知识对可持续性产品实际购 买的影响 因此

服装行业需要了解最好的教育消费者的方式 。 , , 来鼓励可持续消费 最后

消费者对可持续时尚产品 。 , (SFP)和

网路口碑意图的态度存在跨文化差异。

CORRESPONDENCE TO eunju ko ejko@yonsei.ac.kr

© 2017 korean scholars of Marketing science

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL FASHION MARKETING 221

本研究的目的是1 调查环境问题和可持续时尚产品的产品知 )

识是否可能增加可持续时尚产品的购买 确定影响网路口碑 ,2) 意图的因素

调查可持续时尚产品背景下的营销方式和跨文 ,3) 化差异 结果表明

当消费者认为产品有价值时 对可持续时尚 。 , , 产品有积极的态度 而不是感知到风险 该研究为提高可持续时 , 。

尚消费提供了市场洞察的方法。 1. Introduction

Increased environmental concerns have led consumers, manufacturers, and researchers

to turn attention to the needs for sustainable consumption in electricity, textiles, apparel,

food, and grocery products. In addition, fashion manufacturers are recognizing that fash-

ion consumption is becoming a key concern (Vermeir & Verbeke, 2006) because fashion

consumption and the supply chain have negative environmental impacts and significant

carbon footprints through toxic dyes and water contamination (Fineman, 2001). Thus, in

the past decade, the fashion industry has instituted ecological and ethical movements to

assure that fashion products remain sustainable.

Companies are increasingly focusing on sustainable production to support consumer

concerns or to increase their awareness of the needs for environmental protection (Kim,

Taylor, Kim, & Lee, 2015). If company efforts are to be successful, consumers must perceive

that sustainable fashion has long-term benefits. However, consumers are often cautious

about choosing sustainable fashion products and may not always behave in alignment

with their positive attitudes toward sustainable consumption (McNeill & Moore, 2015).

Consequently, as consumer demands for green manufacturing increase, companies will

need better understandings of consumer behavior and attitudes regarding sustainability for future success.

Social media researchers must be aware that consumers have cross-cultural differences

in their attitudes toward sustainable fashion products (SFPs) and eWOM intentions. All

nations, including the three major East Asia countries – Korea, China, and Japan – have

recognized the need for serious political and economic attention to environmental issues,

for worldwide cooperation in solving environmental threats (Kim & Kim, 2010), and for

instituting political and economic leadership in encouraging global environmental pro-

tection and maintenance. As interest grows in eco-friendly products and well-being, the

Korean, Chinese, and Japanese SFP industry needs better understandings of consumer

decision-making processes and attitudes toward the industry (Yoon & Yoon, 201 ) 3 . Indeed,

cross-national sustainable fashion researchers have largely focused on behavior predictions,

but have rarely studied eWOM intentions regarding SFPs.

The aims of this study are (1) to investigate whether environmental concerns and prod-

uct knowledge of SFP may enhance SFP decision-making processes, (2) to identify the

factors that influence eWOM intentions, and (3) to investigate marketing approaches and

cross-cultural differences in the SFP context.

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

Involvement in eco-friendliness, product purchase intentions, environmental behavior,

and decision-making strongly depend on individual awareness levels and social norms 222 H. M. KONG AND E. KO

(Stern, 2000). Although many studies have examined consumer attitudes and behavior

toward sustainable fashion, few have tried to predict behaviors, attitudes, and consumer

decision-making processes. However, some have investigated fashion consumers regarding

their motivations and the value they ascribe to eco-fashion consumption (Niinimäki, 2010).

In this research, we identify which consumption variables will cause consumers to favor

SFPs. We assert that eWOM intentions to purchase SFPs expressed on online platforms can increase purchasing behavior.

2.1. Consumers’ perception of sustainable fashion products

Consumers and corporations now consider sustainability to be a major business issue. The

fashion business often uses the term sustainabilit y interchangeably with ec - o friendly, green,

ethical, and sustainable fashion (Newholm & Shaw, 2007). Consequently, the non-unified

terminology can be confusing. Sustainable fashion manufacturers use environmentally,

economically, and socially preferable processes to meet the needs of the present genera-

tion without compromising future generations, to cause little or no environmental impact,

and to use eco-labeled or recycled materials (Fletcher, 2008). As the fashion business has

increased consumer awareness of environmental concerns, green products, and sustainable

brands, consumers highly motivated by environmental concerns now consider sustainable

consumption to be a major factor influencing their purchase behavior (Stern, Dietz, & Guagnano, 1995).

Fashion consumers generally have positive attitudes toward environmental protection,

but their decisions to purchase eco-fashions are highly complex and often negative (Joergens,

2006; Niinimäki, 2010). Unlike their decisions regarding food or medicine, they fail to see

health and well-being benefits in purchasing eco-fashion products (Joergens, 2006).

Environmental concerns and knowledge about the environment are important determi-

nants of environmental behavior and eco-friendly apparel consumption behavior (Butler &

Francis, 1997; Kim & Damhorst, 1

998). Environmental attitudes, concerns, and knowledge

are widely assumed to generate environmental behaviors, and are thus essential in under-

standing green product purchases (Cheung, Lam, & Lau, 2015). Specifically, individuals

must be concerned about the environment before they become involved in environmental

issues (Oskamp et al., 1991) and demand eco-friendly products (Williams, 2008).

Consumers who have environmental knowledge have been shown to have deeper envi-

ronmental concerns (Arcury, Scollay, & Johnson, 1987), to perceive that environmental

protections are effective (Ellen, Wiener, & Cobb-Walgren, 1991), to believe in environ-

mental protections (Granzin & Olsen, 1991), and to make eco-friendly purchase decisions

(Hustvedt & Dickson, 2009).

Consumer perceptions regarding health risks predict whether they are likely to recy-

cle, conserve energy, vote for environmentally oriented representatives, or educate others

about environmental issues (Flynn, Slovic, & Mertz, 1994). However, if consumers do not

believe that environmental degradation is a health risk, they are less likely to be eco-friendly.

Before they will perceive that SFPs have value, they must perceive that eco-friendliness

brings health and financial benefits (Oskamp et al., 199 )

1 and ecological value (Koller, Floh,

& Zauner, 2011). Although green conscious consumers indicate willingness to engage in

environmental consumption, most rarely purchase sustainable apparel (Kim & Damhorst,

1998). Many researchers have tried to explain the gap between eco-friendly attitudes and

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL FASHION MARKETING 223

behavior (Vermeir & Verbeke, 200 )

6 , but have failed to provide definitive answers explaining

how knowledge about sustainability issues impacts actual purchase of sustainable products

(Kong, Ko, Chae, & Mattila, 2016). To show how environmental concerns and knowledge

impact the SFP industry, we propose the following hypotheses:

H : Environmental concerns will negatively influence perceived risk in purchasing sustainable 1-1 fashion products.

H : Environmental concerns will positively influence perceived benefit from purchasing sustain- 1-2 able fashion products.

H : Product knowledge will negatively influence perceived risk from purchasing sustainable 2-1 fashion products.

H : Product knowledge will positively influence perceived benefit of purchasing sustainable 2-2 fashion products.

2.2. Effects of perceived risk and perceived benefit on satisfaction regarding

sustainable fashion products

When consumers evaluate and then assess that products or services have valuable attributes,

they form perceived value, which may then lead to positive word-of-mouth, purchase inten-

tions (Sweeney, Soutar, & Johnson, 1999), and expectations that they will receive positive

outcomes by purchasing the products or services.

Negative expectations will bring perceptions of possible risks; positive expectations will

not (Stone & Grønhaug, 1993). Perceived risk is a hypothetical, psychological construct in

the context of information seeking, brand loyalty, satisfaction, and purchase choices (Bauer,

1960; Stone & Grønhaug, 1993) to avoid potentially negative outcomes. In the context of

green behavior, “green perceived risk” is “the expectation of negative environmental con-

sequences associated with purchase behavior” (Peter & Ryan, 1976).

Perceived benefits from green products include contributions to health, the common

good, social conditions, emotional states, environmental improvement, energy savings, eco-

nomic advantages (Hartmann & Apaolaza Ibáñez, 200 )

6 , and moral satisfaction (Kahneman

& Knetsch, 1992). In the SFP context, we propose the following hypotheses:

H : Perceived risk of SFP will negatively influence satisfaction. 3-1

H : Perceived benefit of SFP will positively influence satisfaction. 3-2

2.3. Consumers’ satisfaction and behavioral intentions toward sustainable fashion products

Consumers generally trust their peer consumers more than they trust marketers or adver-

tisers (Sen & Lerman, 2007). Consequently, WOM communication strongly affects con-

sumer attitudes and behavioral intentions (Chatterjee, 200 )

1 . When consumers are satisfied

or dissatisfied with products or services, they can spread positive or negative messages

about their purchase intentions via WOM and eWOM (Goldenberg, Libai, & Muller, 2001),

which appeals to information seekers who are interested in reducing risk, securing lower

prices, and easily accessing information before they make purchase decisions (Goldsmith & Horowitz, 2006).

Cross-cultural differences are seen in the use of eWOM (Zhang & Daugherty, 2010) in

influencing brand reputation (Dellarocas, 2003), trust (Benedicktus & Andrews, 2006), 224 H. M. KONG AND E. KO

product attitudes (Bickart & Schindler, 2001), and consumer decision-making (De Bruyn,

Liechty, Huizingh, & Lilien, 2008). Koreans tend to respond most strongly to social media

advertising in choosing sustainable organic food products (Minton, Lee, Orth, Kim, &

Kahle, 2012). They tend to have highly responsible motives, anti-materialistic views, and

a willingness to contribute to sustainable charities. The Internet is now one of the most

important communication channels for obtaining knowledge and information about prod-

ucts and services and for influencing purchasing processes (Pookulangara & Koesler, 201 ) 1 .

Satisfaction plays a major role in predicting purchase intentions (Espejel, Fandos, &

Flavián, 2008). In addition, green trust positively influences whether consumers will pur-

chase green products (Chen, 2010). They are likely to have green purchase intentions if they

feel that green products meet their environmental needs (Netemeyer, Maxham, & Pullig,

2005). WOM communication, including eWOM, strongly influences consumer attitudes,

satisfaction, behaviors, and purchase intentions (Brown & Reingen, 198 ) 7 . Consumers who

have positive environmental concerns are likely to spread positive word of mouth about their

concerns (Chen, 2010). If they perceive that SFP has value, they will spread positive word

of mouth about it (Ryu, 2010). Thus consumers’ satisfaction levels influence their purchase

intentions and intentions to spread negative or positive WOM (Cheng, Lam, & Hsu, 2006).

Consequently, those who intend to purchase SFP will disburse positive eWOM. Thus, we

propose the following hypotheses:

H : Satisfaction with SFP will positively influence eWOM intentions. 4-1

H : Satisfaction with SFP will positively influence purchase intentions. 4-2

H : eWOM intentions will positively influence purchase intentions. 5

2.4. Cross-cultural effects on sustainable consumption

Both the business sector and nations recognize the need for green growth strategies (Cho,

Thyroff, Rapert, Park, & Lee, 2013). China, South Korea, and Japan have recently instituted

government regulations to renew industrial development, to create export platforms that will

be sustainable for decades, and to deal with carbon emissions on a national level (Mathews,

2012). A survey of 18 countries revealed that Chinese consumers rank second in sustainable

consumption; Koreans rank third; and Japanese rank sixteenth (Greendex, 2014). Perhaps

the influence of Confucianism determines their strong propensity to conform with social

group norms, maintain face (Redding & Michael, 1983), adhere to group orientations, and

to be strongly involved in sustainable consumption.

South Koreans are also changing their attitudes regarding sustainable responsibility,

particularly for corporations (Welford, 2004), and now tend to purchase environmentally

friendly products. They recognize that corporations and the government must cooperate

to save the environment rather than to prioritize individual benefits (Garcia, 2010). Indeed,

the availability of green information positively affects green consumption in Korea (Young,

Hwang, McDonald, & Oates, 2010). China is facing particularly challenging environmental

problems: the US Embassy in Beijing has recorded air pollution that far exceeds the accept-

able index (Lallanilla, 2013). Consequently, the Chinese Government has implemented

environmental regulations in economic development. An increasing number of educated

Chinese consumers are recognizing the importance of eco-friendly purchases for their long-

term well-being (Liu, 1994). Japan is rapidly adopting lifestyles of health and sustainability

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL FASHION MARKETING 225

(LOHAS). LOHAS consumers now include 29% of Japanese citizens; most are over 60years

old, are highly educated college graduates, have upper incomes, are particularly interested in

health benefits, and are strongly persuaded by social and environmental impacts (Fukushi & Schumacher, 2005).

Researchers are paying continual attention to national, corporate, consumer, and indi-

vidual behavior domains but have paid limited attention to cultural effects on sustainable

consumption behavior (Cho et al., 201 )

3 . Many governments, corporations, and consumers

have lagged behind South Korea, China, and Japan in reacting to the seriousness of environ-

mental issues, but they are slowly moving toward more socially responsible and sustainable

consumption. However, they need better understandings of cross-cultural perspectives

if they are to effectively persuade citizens to adopt responsible SFP choices and to form positive eWOM intentions.

To study cross-cultural background effects on SFP decision-making and perceptions, we

collected data from South Korea, China, and Japan (Hanyu, Kishino, Yamashita, & Hayashi,

2000; Kang, Liu, & Kim, 2013). We also added a hypothesis to reflect our focus.

H : Effects will be culturally modified in South Korea, China, and Japans. 6 3. Research method 3.1. Sampling

Participating in our survey about decision-making processes in purchasing SFPs were South

Korean, Chinese, and Japanese consumers who had experience with SFPs, were 20 to 30

years old, lived in metropolitan areas, and were highly educated. Sustainable, green, eco-

friendly, organic, and ethical fashion are terms used interchangeably, so we tried to provide

a common frame of reference for classifying sustainable fashion. The survey instrument was

first developed in Korean and translated into Chinese and Japanese using back translation

techniques to ensure that all groups understood the relationships between variables. 3.2. Measures

The measurements for empirical analyses had been previously validated in prior studies,

but the instruments were revised to fit the sustainable fashion research topic and were

measured with 7-point Likert scale, ranging from disagree strongl y (1) to agree strongly

(7). The 11 scale items for environmental concern and 7 items of product knowledge were

modified from Tarrant and Cordell (1997) and Laroche, Bergeron, and Goutaland (2003).

Perceived risk (17 items) and perceived benefits (8 items) were measured by items adapted

from Jacoby and Kaplan (1972), Stone and Grønhaug (1993), and Shim and Bickle (1994).

Satisfaction was measured with four items adapted from Oliver (1993). eWOM intention

(3 items) and purchase intention (7 items) were measured with items adapted from Gruen,

Osmonbekov, and Czaplewski (2006) and McKnight, Cummings, and Chervany (1998).

3.3. Data collection and data analysis

Our 933-question survey research methodology included scales to represent all variables

related to the investigation regarding sustainable fashion consumption and motivations 226 H. M. KONG AND E. KO

for making purchase decisions. Quantitative methods are beneficial because they allow

researchers to concretely and objectively evaluate environmental concerns, product knowl-

edge, perceived value, purchase behavior, and SFP eWOM intentions.

SPSS 23.0 was used to analyze the frequency, EFA (exploratory factor analysis), and reli-

ability. AMOS 18.0 was used to validate the structural equation model, CFA (confirmatory

factor analysis), structural equation model (SEM), and multiple group analysis. 4. Results

4.1. Demographic characteristics

A total of 933 college students, graduate school students, and college graduates responded

to the questionnaire: Korean (N=314), Chinese (N=319), and Japanese (N=300). Level of

education and age were almost equally distributed in the data samples for each country, so

we could control characteristics of the respondents across the three countries. Consumers

aged 20 to 30years old, called generation Y, are the main SNS users and are showing growing

interest in green consumption, although SFP consumers are found in all age groups. About

30% of respondents were men in their 20s and 30s and were almost equally distributed across

three countries. About 80% of South Korean and Japanese respondents reported that they

spend less than $300 in fashion item expenditure per month; 57.9% of Chinese consumers

reported spending less than $300. About 60% reported having a single marital status.

4.2. Measurement validity

4.2.1. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results

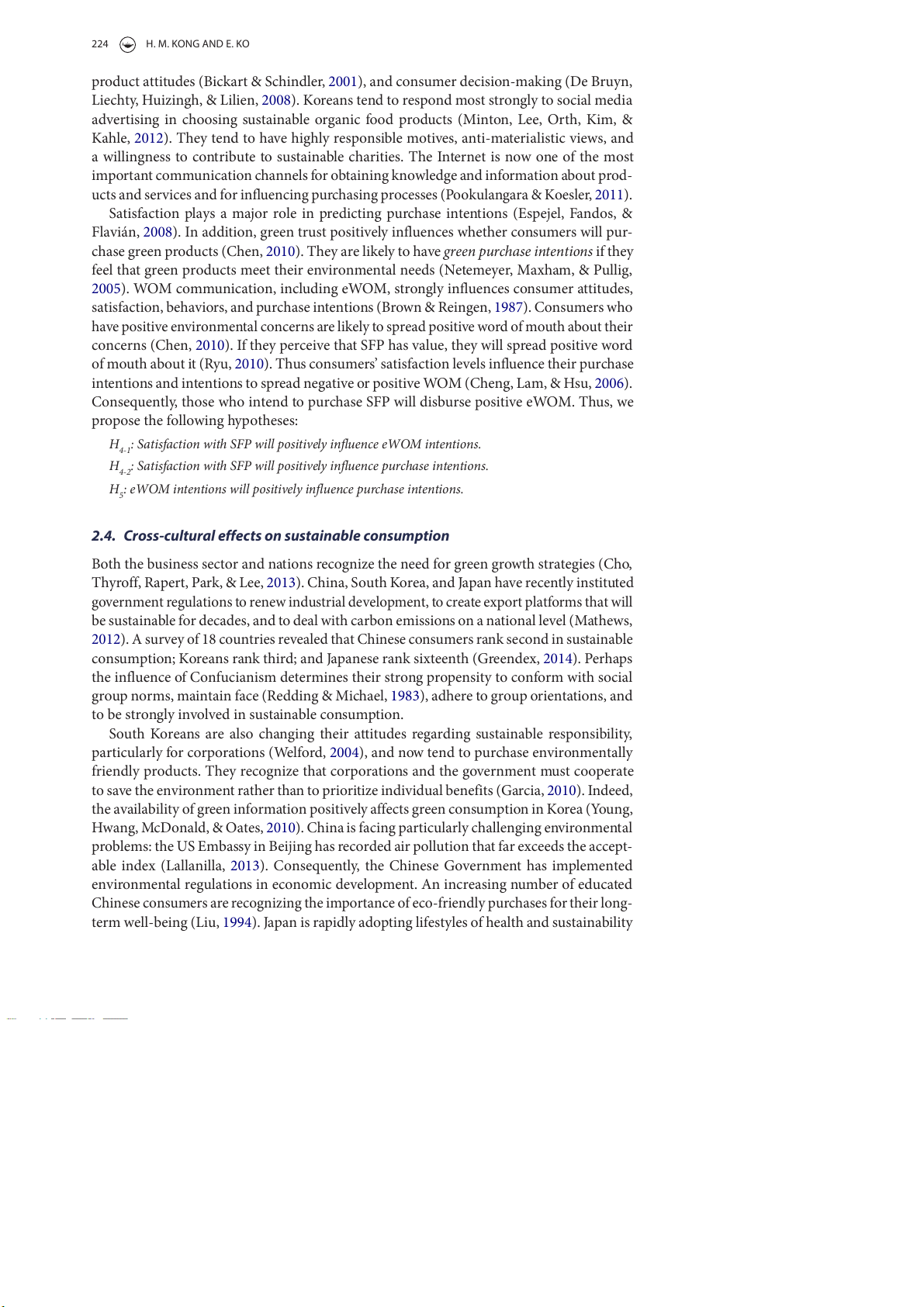

Before testing for validity of the conceptual research model, a confirmatory factor analysis

of the variables for the structural equation model was implemented. Table 1 shows the

confirmatory analysis results. First, the overall model fit was suitable for the data. The

criterion suggested (χ²=2051.085, df=413 NFI=.923, IFI=.938, CFI=.938, GFI=870,

RMSEA=.063). Generally, NFI, IFI, CFI values over .90 are recommended (Hair, Black,

Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 2006). The data showed a good fit, with RMSEA under .1,

and thus were very suitable when RMSEA was under .05 (Steiger, 1998). The squared mul-

tiple correlation (SMC) values were over .4, suggesting that the variables were measured

accurately. In addition, the standardized factor loadings and squared multiple correlations were all over .5.

Examination of each component in the confirmatory factor analysis showed that the var-

iables had three subfactors: environmental concerns, knowledge, and behavior. The second

factor included four subfactors: physical, social/psychological, and time loss distributed in

perceived risk. The third factor included physical/ecological concerns.

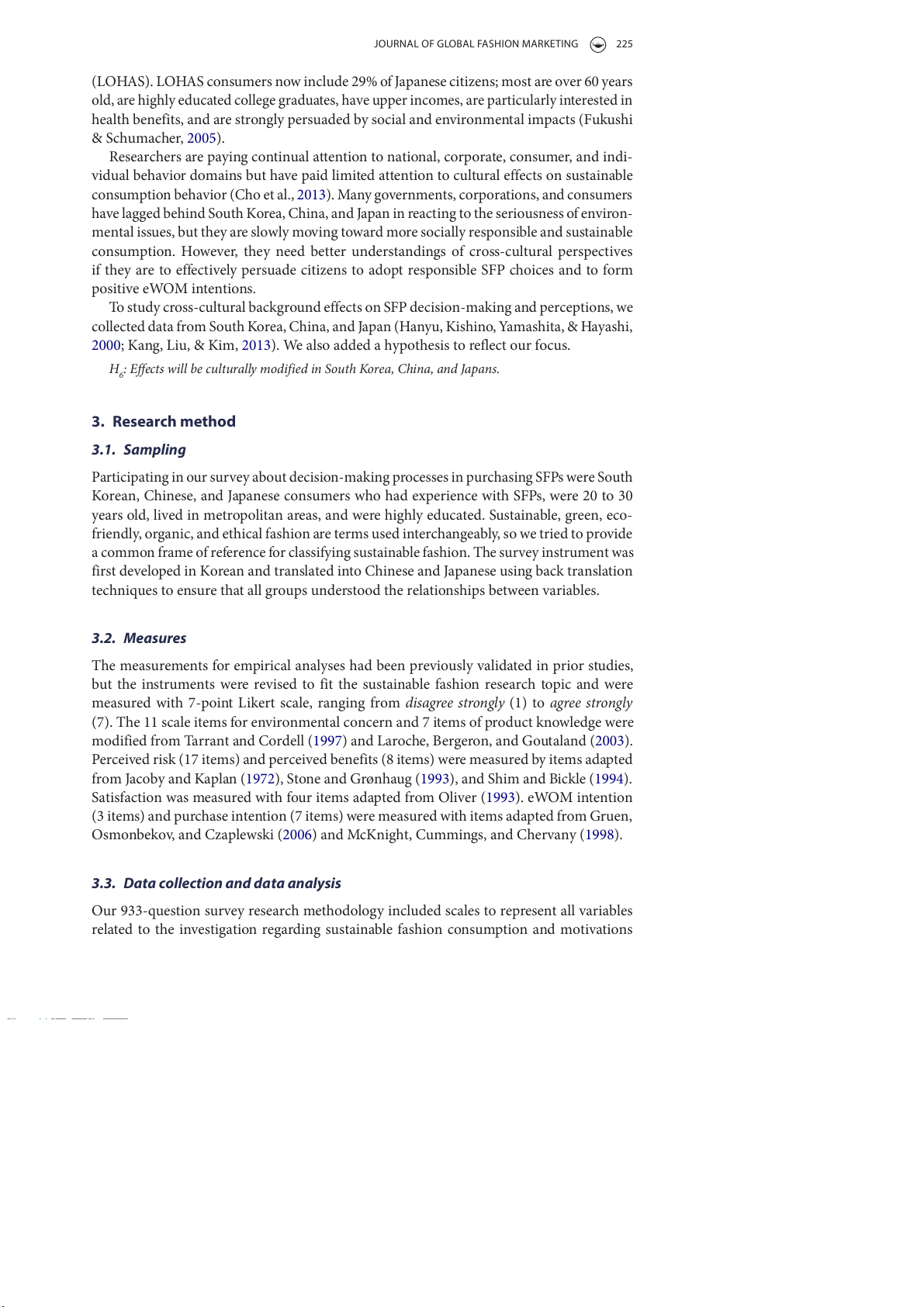

4.3. Structural equation model (SEM) results

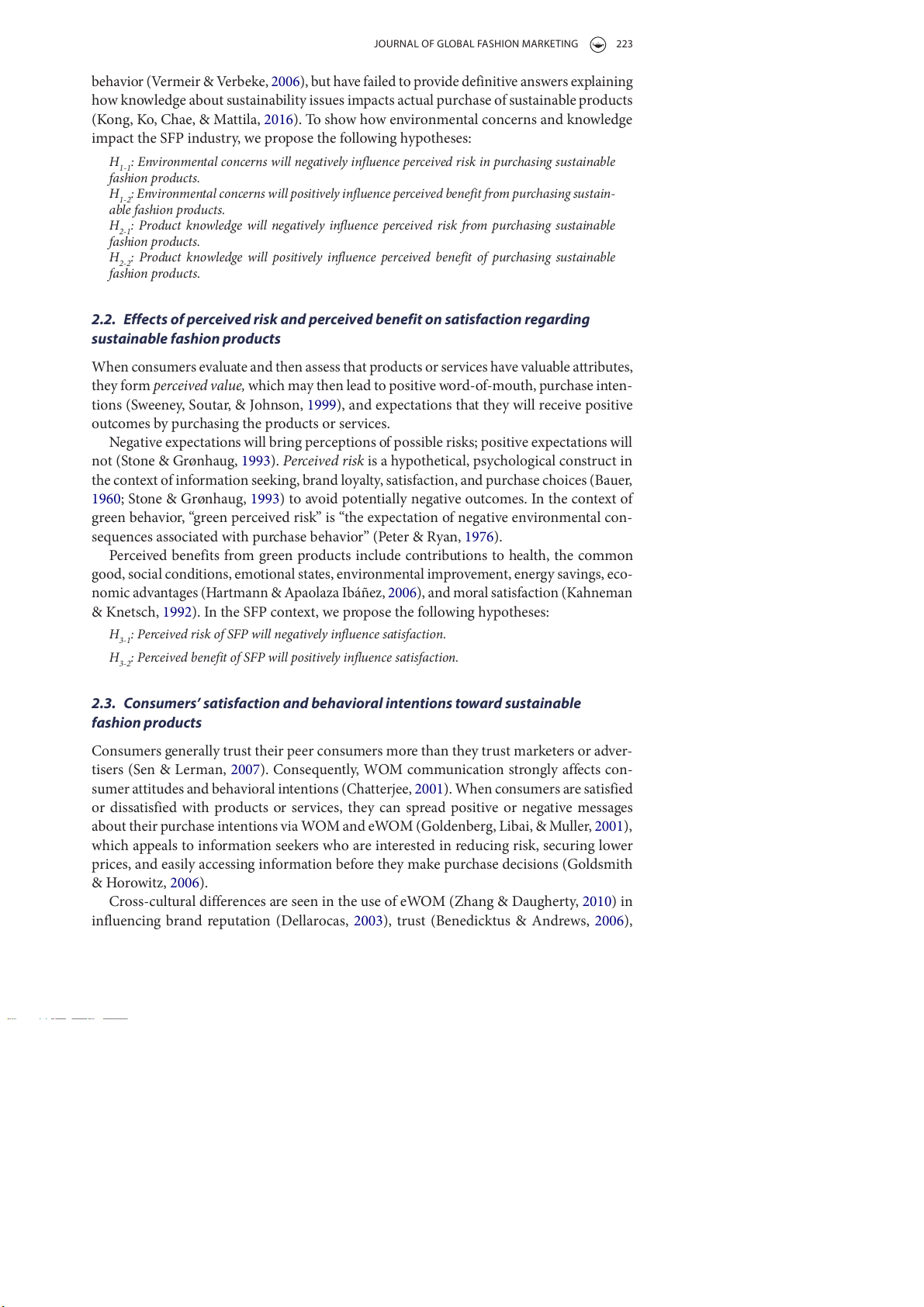

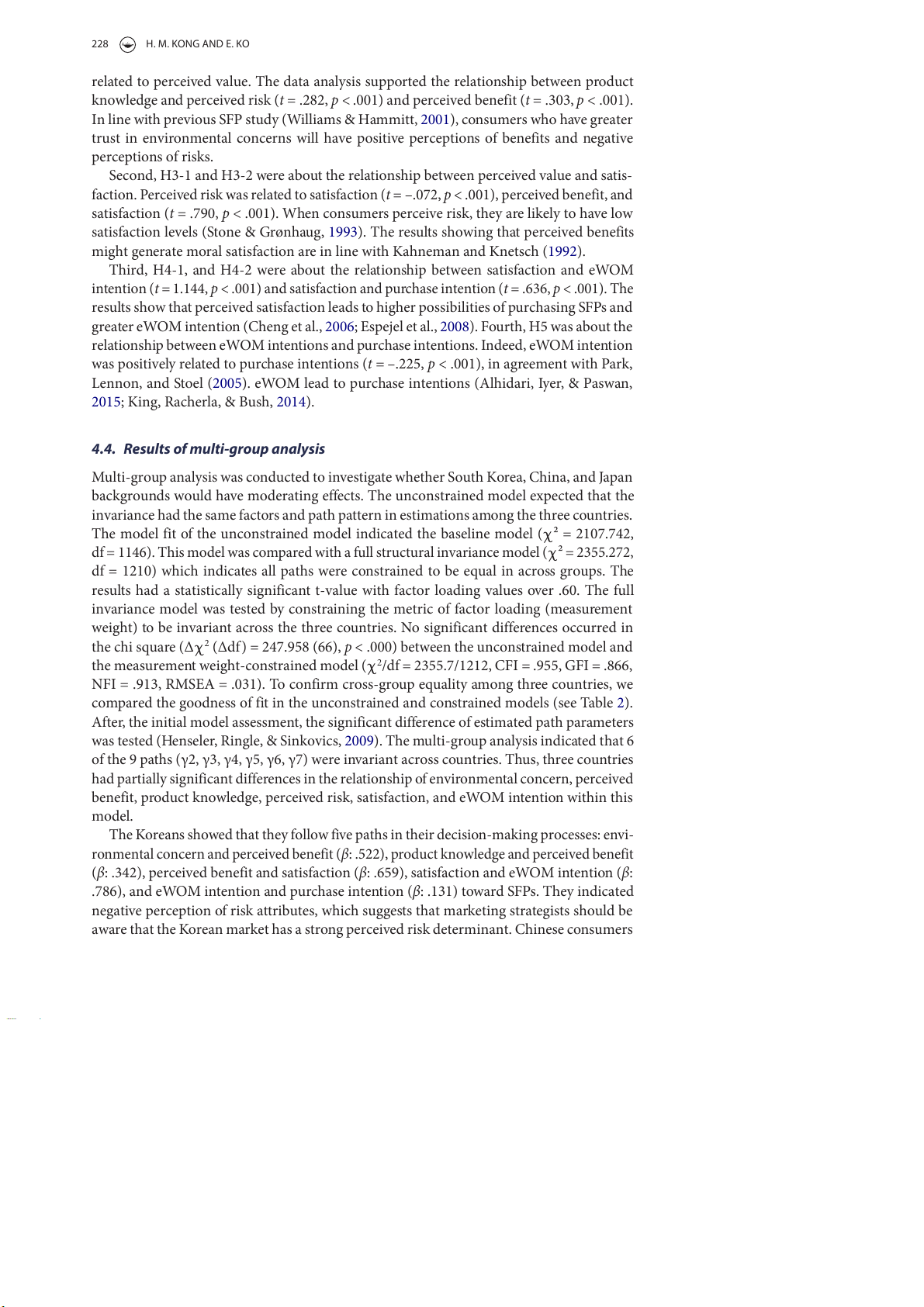

SEM testing was conducted to verify compatibility with the hypotheses. Figure 1 shows that

the theoretical model was validated. The model fit test indicated χ²=754.496, df=382,

(χ²/df=1.975), GFI=.952, RMSEA=.031, NFI=.972, TLI=.983, CFI=.986, satisfying

the criterion suggested by Bagozzi and Yi (1988).

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL FASHION MARKETING 227

Table 1.results of Cfa. Factors Items CFA AVE CR C. α environmental concern eC1 .649 .468 .879 .879 eC2 .727 eC3 .675 Product knowledge Pk4 .814 .605 .943 .932 Pk5 .769 Pk6 .814 Pk7 .710 Perceived risk Psychological Pr6 .688 .516 .968 .953 Pr7 .780 Pr8 .774 Pr9 .774 Pr10 .725 time loss Pr11 .651 Pr12 .642 Pr13 .697 Perceived benefit Physical/ecological Pb2 .726 .534 .814 .903 Pb3 .728 Pb4 .738 satisfaction st1 .647 .604 .925 .886 st2 .764 st3 .716 st4 .544 eWoM intention eW1 .819 .666 .957 .896 eW2 .815 eW3 .815 Purchase intention Pi3 .659 .631 .929 .930 Pi4 .713 Pi5 .723 Pi7 .655 Notes: Model fit: ²

χ =2051.085, df=413 nfi=.923, ifi=.938, Cfi=.938, Gfi=870, rMsea=.063. Environmental .043 eWOM Perceived risk Concern intention -.077*** 1.144*** .486*** .225 *** Satisfaction .212*** .790*** .636*** Product Perceived Purchase Knowledge benefit intention .303***

Model fit: χ²=754.496, df=382, (χ²/df=1.975), GFI=0.952, RMSEA=0.031, NFI=0.972, TLI=0.983, CFI=0.986

***p<.001, **p<.01, *p<.05

Figure 1.results of structural equation model.

Figure 1 illustrates the research model results. All hypotheses were statistically signifi-

cant except for H1-1. H1-1 and H1-2 dealt with how environmental concerns and product

knowledge are related to perceived value of SFP. Environmental concern (t=.043, n.s)

failed to significantly influence perceived risk but positively influenced perceived benefit

(t=.486, p<.001). The results of H2-1 and H2-2 showed that product knowledge was 228 H. M. KONG AND E. KO

related to perceived value. The data analysis supported the relationship between product

knowledge and perceived risk (t=.282, p<.001) and perceived benefit (t=.303, p<.001).

In line with previous SFP study (Williams & Hammitt, 2001), consumers who have greater

trust in environmental concerns will have positive perceptions of benefits and negative perceptions of risks.

Second, H3-1 and H3-2 were about the relationship between perceived value and satis-

faction. Perceived risk was related to satisfaction (t=–.072, p<.001), perceived benefit, and

satisfaction (t=.790, p<.001). When consumers perceive risk, they are likely to have low

satisfaction levels (Stone & Grønhaug, 1993). The results showing that perceived benefits

might generate moral satisfaction are in line with Kahneman and Knetsch (1992).

Third, H4-1, and H4-2 were about the relationship between satisfaction and eWOM

intention (t=1.144, p<.001) and satisfaction and purchase intention (t=.636, p<.001). The

results show that perceived satisfaction leads to higher possibilities of purchasing SFPs and

greater eWOM intention (Cheng et al., 2006; Espejel et al., 2008). Fourth, H5 was about the

relationship between eWOM intentions and purchase intentions. Indeed, eWOM intention

was positively related to purchase intentions (t=–.225, p<.001), in agreement with Park,

Lennon, and Stoel (2005). eWOM lead to purchase intentions (Alhidari, Iyer, & Paswan,

2015; King, Racherla, & Bush, 2014).

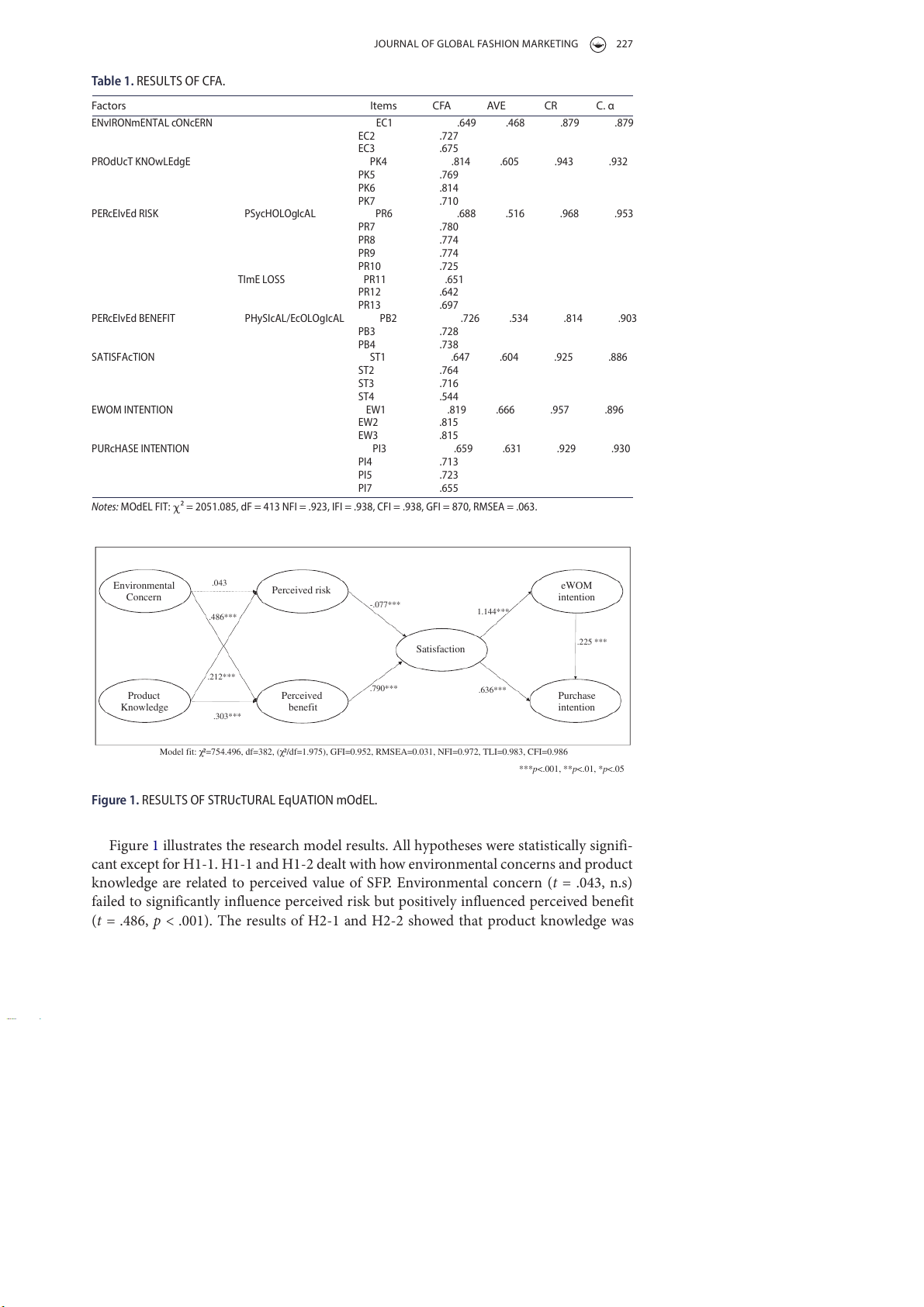

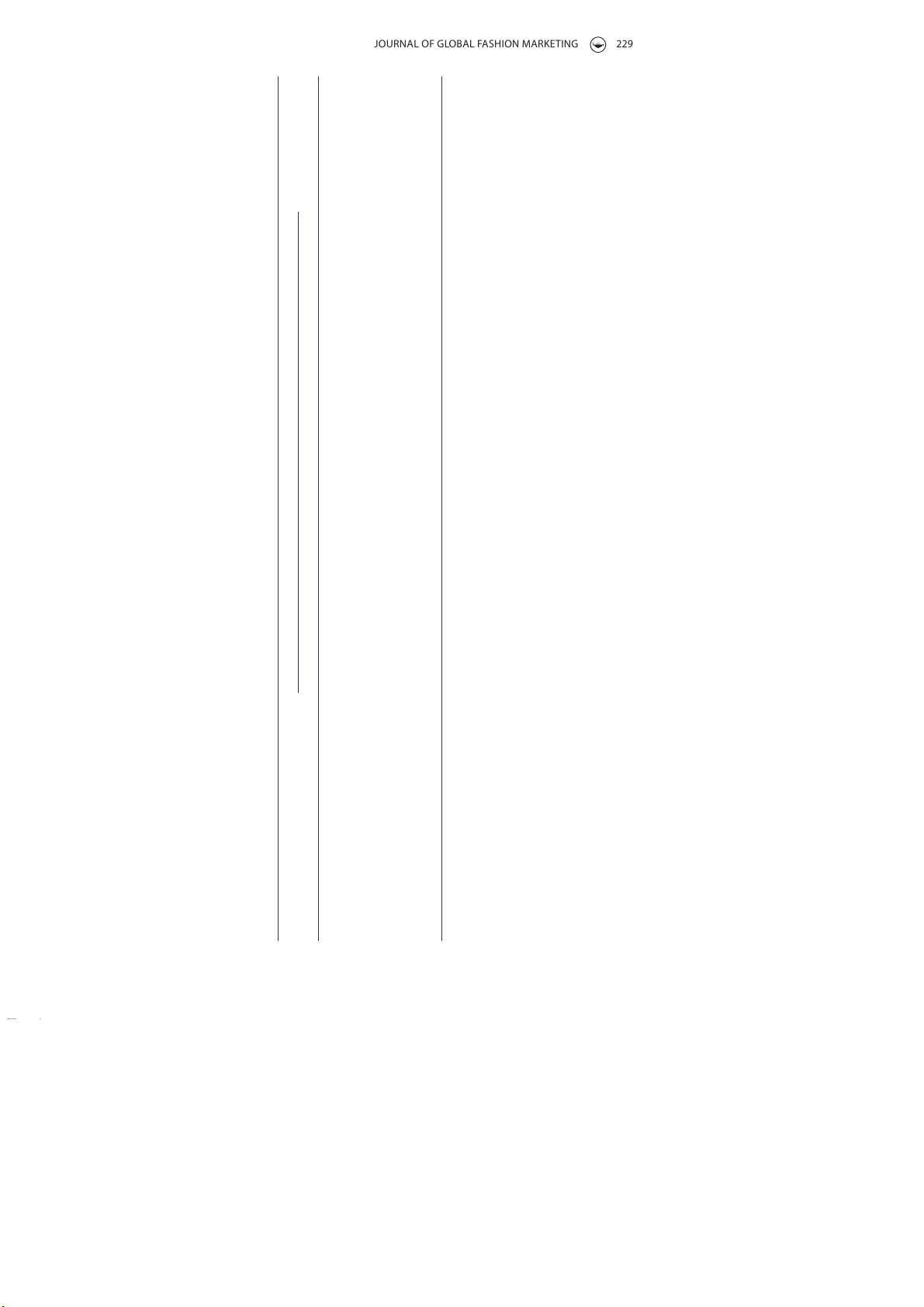

4.4. Results of multi-group analysis

Multi-group analysis was conducted to investigate whether South Korea, China, and Japan

backgrounds would have moderating effects. The unconstrained model expected that the

invariance had the same factors and path pattern in estimations among the three countries.

The model fit of the unconstrained model indicated the baseline model (χ²=2107.742,

df=1146). This model was compared with a full structural invariance model (χ²=2355.272,

df=1210) which indicates all paths were constrained to be equal in across groups. The

results had a statistically significant t-value with factor loading values over .60. The full

invariance model was tested by constraining the metric of factor loading (measurement

weight) to be invariant across the three countries. No significant differences occurred in

the chi square (Δχ2 (Δdf) = 247.958 (66), p<.000) between the unconstrained model and

the measurement weight-constrained model (χ2/df=2355.7/1212, CFI=.955, GFI=.866,

NFI=.913, RMSEA=.031). To confirm cross-group equality among three countries, we

compared the goodness of fit in the unconstrained and constrained models (see Table 2).

After, the initial model assessment, the significant difference of estimated path parameters

was tested (Henseler, Ringle, & Sinkovics, 2009). The multi-group analysis indicated that 6

of the 9 paths (γ2, γ3, γ4, γ5, γ6, γ7) were invariant across countries. Thus, three countries

had partially significant differences in the relationship of environmental concern, perceived

benefit, product knowledge, perceived risk, satisfaction, and eWOM intention within this model.

The Koreans showed that they follow five paths in their decision-making processes: envi-

ronmental concern and perceived benefit (β: .522), product knowledge and perceived benefit

(β: .342), perceived benefit and satisfaction (β: .659), satisfaction and eWOM intention (β:

.786), and eWOM intention and purchase intention (β: .131) toward SFPs. They indicated

negative perception of risk attributes, which suggests that marketing strategists should be

aware that the Korean market has a strong perceived risk determinant. Chinese consumers

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL FASHION MARKETING 229 2) .428 f = 2.613 8.295 3.468 7.851 38.268 20.879 21.962 13.332 ² (d χ∆ ² 2352.232 χ 2353.087 2347.405 2317.432 2334.821 2333.738 2342.368 2347.849 2355.272 .005 − 7.167*** 11.321*** 7.460*** 6.382*** 3.636*** 9.950*** 5.604*** t − 10.236*** .059 .049 .075 .052 ese .047 .031 .037 .082 .118 an S.E. Jap .000 .552 .538 .354 .201 .133 .837 .291 − 1.177 Est. .031. = 2.225* 6.966*** 6.664*** − 6.061*** 4.681*** 4.699*** 4.780*** 8.822*** 3.494*** sea t − .092 .070 .092 .083 .913, rM .111 ese .067 .043 .036 .099 fi= in h S.E. C .205 .485 .612 .409 .203 .168 .471 .976 .288 .866, n − − fi= Est. .955, G .959 7.777*** 8.604*** 6.446*** 2.038* t 1.112 8.591*** 1.341 5.953*** − .103 .067 .091 .065 .040 .030 .111 .205 .064 rean o S.E. K 2355.7(1212), Cfi= .099 .522 .786 .072 .342 .040 .659 .131 1.320 a − (df) =2 χ Est. e. at efit dices: sk n efit lysis. n tio a sk fit in zed estim n eived ri eived ben n n tio ten del o p a n tio tio ten e in dardi u Perc Perc m 6) tio as sfac ten e in ral Perceived ri Perceived ben stan in as rch n esis (H cern cern sfac sati M h ctu ua Pu lti-gro o th n n rc u o co co sati eW Pu n yp ledge ledge t stru .001; f m H tal tal w w efit tio < o o sk n n o an p en en m m tio tio ten lts n n vari ct kn ct kn in su du du sfac sfac M c in .01; *** viro viro o

.re en en Pro Pro Perceived ri Perceived ben sati sati eW etri 2 le .05; ** b tes: M o o < Ta N γ1 γ2 γ3 γ4 γ5 γ6 γ8 γ9 n *p 230 H. M. KONG AND E. KO

showed positive perceptions of SFP in all paths. Environmental concern showed the least

significant relationship with perceived risk (β: –.205). Chinese consumers showed that

they are highly concerned about the social aspects of environmental concerns, but they are

more concerned about consumer benefits than about perceived risk. Japanese consumers

showed negative perceptions of perceived risk. They were concerned about SFP health ben-

efits but not SFP negative impacts. The findings confirmed research showing that Japanese

are most focused on social and environmental impacts and benefits to health (Fukushi &

Schumacher, 2005). Therefore, Japanese marketers should be aware that perceptions of risk have negative impacts. 5. Conclusion

Although numerous studies have examined consumers’ attitudes and intentions to purchase

SFPs, relevant empirical research results do not fully explain decision processes regarding

SFP purchases. Interest in SFP is growing, but the actual purchasing behaviors are still

forming. If marketers are to increase the popularity of SFP in the fashion marketplace, they

need better understandings of consumer decision-making processes. Consequently, in this

study, we investigated cultural differences in SFP decision-making processes and eWOM

intentions across South Korea, China, and Japan.

We examined factors influencing consumers’ decision-making when considering pur-

chasing SFPs: their environmental concerns, product knowledge, perceived value, atti-

tudes, and behavioral intentions. Consumers have generally positive attitudes, willingness

to engage, purchase intentions, eWOM intentions, and beneficial value impressions, but

perceived risk is apparently not related to satisfaction. Consumers of sustainable products

indeed have strong environmental concerns, product knowledge, and positive perceived

benefits. However, some hesitate to purchase SFP because they are skeptical about its quality

and esthetic value. Those who are loyal to sustainable products tend to focus on health,

eco-friendliness, and economic benefits. If they see that sustainable purchasing behavior

threatens no harm to their health or finances, they will be more likely to purchase SFPs.

Varying results from three countries with similar cultural backgrounds indicate the

need for different marketing approaches. Chinese consumers are more highly educated

about environmental issues, more involved, and motivated to be ethical consumers. Korean

consumers tend to avoid uncertainty and risk in making decisions. Japanese consumers are

similar to Korean consumers in having negative perceptions about perceived risks. They

highly prefer health-related benefits.

The research suggests that marketing managers must be aware that consumers in North

Eastern countries have different levels of knowledge, varying decision-making process, and

diverse motivations to purchase sustainable fashion (Sun & Ko, 2016). In addition, social

media and eWOM are essential marketing tools in all three countries.

6. Implications and future research

In this study, we provide a model for better understanding consumer behavior regarding

sustainable fashion. If marketers are to alter purchase patterns, they must know how to

motivate consumers, change attitudes, and enhance perceptions of value. The research is a

new way to identify consumer intentions to spread eWOM encouraging the use of SFP. The

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL FASHION MARKETING 231

three countries are considered to occupy a similar cultural zone. However, our results show

that they have distinct consumption behaviors toward SFP, with China showing the biggest

difference. The findings diverge from previous studies (Koller et al., 2011) in showing that

the Chinese are similar to Koreans and Japanese in having environmental concerns that

affect their attitudes toward perceived risk. Instead, familiarity with cultural issues and not

cultural background has the strongest effects on environmental concerns (Lee, Ko, Chae,

& Minami, 2017). Considering cultural differences among Chinese, South Koreans, and

Japanese consumers is a divergence from previous studies. Specifically, we find that Chinese

are the strongest SFP consumers.

In the past, marketing strategies have focused on product and store attributes that will

attract customers to environmentally friendly fashion products made with sustainable and

recyclable materials, but the changing market means that attention must turn to online sys-

tems for promoting SFP. Moreover, our results should suggest that marketing strategists for

SFP should be aware that the three countries are interested in the concept of sustainability,

but with varying levels of environmental concern and product knowledge. In particular,

Japanese find more satisfaction when they perceive that environmental consumption brings

health benefits and meets LOHAS lifestyle requirements. Korean consumers who have

positive information about SFP are more likely to form positive attitudes toward SFP.

Social media offers modern possibilities for interaction, networking, and interpersonal

relations. As such it is a credible and appropriate tool for green advertisers and sustainable

fashion marketing companies to reach consumers through eWOM rather than through com-

mercial advertising and marketing. Future research should further consider socio-psycho-

graphic components that will best appeal to various consumer types in online communities. Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grant funded by the

Korean Government (MSIP) [grant number 2015R1A2A2A04005218]. ORCID Eunju Ko

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3130-5427 References

Alhidari, A., Iyer, P., & Paswan, A. (2015). Personal level antecedents of eWOM and purchase

intention, on social networking sites. Journal of Customer Behaviour, 14, 107–125.

Arcury, T. A., Scollay, S. J., & Johnson, T. P. (1987). Sex differences in environmental concern and

knowledge: The case of acid rain. Sex Roles, 16, 463–472.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (198 )

8 . On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy

of Marketing Science, 16, 74–94.

Bauer, R. A. (1960). Consumer behavior as risk taking. In R. S. Hancock (Ed.), Dynamic marketing

for a changing world, Proceedings of the 43rd Conference of the American Marketing Association, Chicago, IL.

Benedicktus, R. L., & Andrews, M. L. (2006). Building trust with consensus information: The effects

of valence and sequence direction. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 6, 3–25.

Bickart, B., & Schindler, R. M. (200 )

1 . Internet forums as influential sources of consumer information.

Journal of Interactive Marketing, 15, 31–40. 232 H. M. KONG AND E. KO

Brown, J. J., & Reingen, P. H. (1987). Social ties and word-of-mouth referral behavior. Journal of

Consumer Research, 14, 350–362.

Butler, S. M., & Francis, S. (1997). The effects of environmental attitudes on apparel purchasing

behavior. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 15, 76–85.

Chatterjee, P. (2001). Online reviews: Do consumers use them? Association for Consumer Research, 28, 129–133.

Chen, Y. S. (2010). The drivers of green brand equity: Green brand image, green satisfaction, and

green trust. Journal of Business Ethics, 93, 307–319.

Cheng, S., Lam, T., & Hsu, C. H. (2006). Negative word-of-mouth communication intention: An

application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 30, 95–116.

Cheung, R., Lam, A. Y., & Lau, M. M. (2015). Drivers of green product adoption: The role of green

perceived value, green trust and perceived quality. Journal of Global Scholars of Marketing Science, 25, 232–245.

Cho, Y. N., Thyroff, A., Rapert, M. I., Park, S. Y., & Lee, H. J. (2013). To be or not to be green:

Exploring individualism and collectivism as antecedents of environmental behavior. Journal of

Business Research, 66, 1052–1059.

De Bruyn, A., Liechty, J. C., Huizingh, E. K., & Lilien, G. L. (200 )

8 . Offering online recommendations

with minimum customer input through conjoint-based decision aids. Marketing Science, 27, 443– 460.

Dellarocas, C. (2003). The digitization of word of mouth: Promise and challenges of online feedback

mechanisms. Management Science, 49, 1407–1424.

Ellen, P. S., Wiener, J. L., & Cobb-Walgren, C. (1991). The role of perceived consumer effectiveness in

motivating environmentally conscious behaviors. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 10, 102–117.

Espejel, J., Fandos, C., & Flavián, C. (200 )

8 . Consumer satisfaction. British Food Journal, 110, 865–881.

Fineman, S. (2001). Fashioning the environment. Organization, 8, 17–31.

Fletcher, K. (2008). Sustainable fashion and clothing. Design journey . s Malta: Earthscan.

Flynn, J., Slovic, P., & Mertz, C. K. (1994). Gender, race, and perception of environmental health

risks. Risk Analysis, 14, 1101–1108.

Fukushi, A., & Schumacher, P. (2005). The Japanese LOHAS market – Opportunities revealed for

organic businesses. Retrieved September 16, 2016, from http://organicnetwork.biz/the-japanese-

lohas-market-opportunities-revealed-for-organic-businesses/

Garcia, C. (2010). Many Koreans lag in green efforts. Retrieved September 10, 2016, from http://www.

koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/biz/2016/04/123_70748.html

Goldenberg, J., Libai, B., & Muller, E. (2001). Talk of the network: A complex systems look at the

underlying process of word-of-mouth. Marketing Letters, 12, 211–223.

Goldsmith, R. E., & Horowitz, D. (2006). Measuring motivations for online opinion seeking. Journal

of Interactive Advertising, 6, 2–14.

Granzin, K. L., & Olsen, J. E. (1991). Characterizing participants in activities protecting the

environment: A focus on donating, recycling, and conservation behaviors. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 10, 1–27.

Greendex. (2014). Consumer choice and the environment: A worldwide tracking survey. Retrieved

August 15, 2016, from http://environment.nationalgeographic.com/environment/greendex/

Gruen, T. W., Osmonbekov, T., & Czaplewski, A. J. (2006). eWOM: The impact of customer-to-

customer online know-how exchange on customer value and loyalty. Journal of Business Research, 59, 449–456.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (200 )

6 . Multivariate data analysis

(6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. humans: Critique and reformulation.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87, 49–74.

Hanyu, K., Kishino, H., Yamashita, H., & Hayashi, C. (2000). Linkage between recycling and

consumption: A case of toilet paper in Japan. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 30, 177–199.

Hartmann, P., & Apaolaza Ibáñez, V. (2006). Green value added. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 24, 673–680.

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL FASHION MARKETING 233

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in

international marketing. In Sinkovics, R. R. & Ghauri, P. N. (Eds.), New challenges to international

marketing (pp. 277–319). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Hustvedt, G., & Dickson, M. A. (2009). Consumer likelihood of purchasing organic cotton apparel.

Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 13, 49–65.

Jacoby, J., & Kaplan, L. B. (1972). The components of perceived risk. In SV-Proceedings of the third

annual conference of the association for consumer research (pp. 382–393). Chicago, IL: Association for Consumer Research.

Joergens, C. (2006). Ethical fashion: Myth or future trend? Journal of Fashion Marketing and

Management: An International Journal, 10, 360–371.

Kahneman, D., & Knetsch, J. L. (1992). Valuing public goods: The purchase of moral satisfaction.

Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 22, 57–70.

Kang, J., Liu, C., & Kim, S. H. (2013). Environmentally sustainable textile and apparel consumption:

The role of consumer knowledge, perceived consumer effectiveness and perceived personal

relevance. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 37, 442–452.

Kim, H. S., & Damhorst, M. L. (1998). Environmental concern and apparel consumption. Clothing

and Textiles Research Journal, 16, 126–133.

Kim, S., & Kim, S. (2010). Comparative studies of environmental attitude and its determinants In

three east Asia countries: Korea, Japan, and China. International Review of Public Administration, 15, 17–33.

Kim, J., Taylor, C. R., Kim, K. H., & Lee, K. H. (2015). Measures of perceived sustainability. Journal

of Global Scholars of Marketing Science, 25, 182–193.

King, R. A., Racherla, P., & Bush, V. D. (2014). What we know and don't know about online word-

of-mouth: A review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28, 167–183.

Koller, M., Floh, A., & Zauner, A. (2011). Further insights into perceived value and consumer loyalty:

A “Green” perspective. Psychology & Marketing, 28, 1154–1176.

Kong, H.-M., Ko, E., Chae, H., & Mattila, P. (2016). Understanding fashion consumers’ attitude and

behavioral intention toward sustainable fashion products: Focus on sustainable knowledge sources

and knowledge types. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 7, 103–119.

Lallanilla, M. (2013). China’s Top 6 environmental concerns. Retrieved August 28, 2016, from http://

www.livescience.com/27862-china-environmental-problems.html

Laroche, M., Bergeron, J., & Goutaland, C. (2003). How intangibility affects perceived risk: The

moderating role of knowledge and involvement. Journal of Services Marketing, 17, 122–140.

Lee, S., Ko, E., Chae, H., & Minami, C. (2017). A study of the authenticity of traditional cultural

products: Focus on Korean, Chinese, and Japanese consumers. Journal of Global Scholars of

Marketing Science, 27, 93–110.

Liu, Y. W. (1994). Green marketing: A new marketing era for China in the coming century. Paper

presented at the 10th Annual Academic Conference of the Chinese Marketing Association of

Colleges and Universities, Shanghai, China.

Mathews, J. A. (2012). Green growth strategies – Korean initiatives. Futures, 44, 761–769.

McKnight, D. H., Cummings, L. L., & Chervany, N. L. (1998). Initial trust formation in new

organizational relationships. Academy of Management review, 23, 473–490.

McNeill, L., & Moore, R. (2015). Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast fashion conundrum:

Fashionable consumers and attitudes to sustainability in clothing choice. International Journal of

Consumer Studies, 39, 212–222.

Minton, E., Lee, C., Orth, U., Kim, C. H., & Kahle, L. (2012). Sustainable marketing and social media:

A cross-country analysis of motives for sustainable behaviors. Journal of Advertising, 41, 69–84.

Netemeyer, R. G., Maxham III, J. G., & Pullig, C. (200 )

5 . Conflicts in the work–family interface: Links

to job stress, customer service employee performance, and customer purchase intent. Journal of Marketing, 69, 130–143.

Newholm, T., & Shaw, D. (2007). Studying the ethical consumer: A review of research. Journal of

Consumer Behaviour, 6, 253–270.

Niinimäki, K. (2010). Eco-clothing, consumer identity and ideology. Sustainable Development, 18, 150–162. 234 H. M. KONG AND E. KO

Oliver, RL. (1993). Cognitive, affective, and attribute bases of the satisfaction response. Journal of

Consumer Research, 20, 418–430.

Oskamp, S., Harrington, M. J., Edwards, T. C., Sherwood, D. L., Okuda, S. M., & Swanson, D. C.

(1991). Factors influencing household recycling behavior. Environment and Behavior, 2 , 3 494–519.

Park, J., Lennon, SJ., & Stoel, L. (2005). On-line product presentation: Effects on mood, perceived

risk, and purchase intention. Psychology & Marketing, 22, 695–719.

Peter, J. P., & Ryan, M. J. (1976). An investigation of perceived risk at the brand level. Journal of

Marketing Research, 13, 184–188.

Pookulangara, S., & Koesler, K. (201 )

1 . Cultural influence on consumers’ usage of social networks and

its’ impact on online purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 18, 348–354.

Redding, S. G., & Michael, N. (1983). The role of “face” in the organizational perceptions of Chinese

managers. International Studies of Management & Organization, 13, 92–123.

Ryu, E. S. (2010). The effect of consumer’s environmnetal attitude on purchase satisfaction repurchase

and word of mouth intention of eco-friendly fashion products (Unpublished master’s thesis). Chung- Ang University, Seoul.

Sen, S., & Lerman, D. (2007). Why are you telling me this? An examination into negative consumer

reviews on the Web. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 21, 76–94.

Shim, S., & Bickle, M. C. (1994). Benefit segments of the female apparel market: Psychographics,

shopping orientations, and demographics. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 12, 1–12. Steiger, J. H. (199 )

8 . A note on multiple sample extensions of the RMSEA fit index. Structural Equation

Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 5, 411–419.

Stern, P. C. (2000). New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally

significant behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56, 407–424.

Stern, P. C., Dietz, T., & Guagnano, G. A. (199 )

5 . The new ecological paradigm in social-psychological

context. Environment and Behavior, 27, 723–743.

Stone, R. N., & Grønhaug, K. (1993). Perceived risk: Further considerations for the marketing

discipline. European Journal of Marketing, 27, 39–50.

Sun, Y., & Ko, E. (2016). Influence of sustainable marketing activities on customer equity. Journal of

Global Scholars of Marketing Science, 26, 270–283.

Sweeney, J. C., Soutar, G. N., & Johnson, L. W. (1999). The role of perceived risk in the quality-value

relationship: A study in a retail environment. Journal of Retailing, 75, 77–105.

Tarrant, M. A., & Cordell, H. K. (1997). The effect of respondent characteristics on general

environmental attitude-behavior correspondence. Environment and Behavior, 29, 618–637.

Vermeir, I., & Verbeke, W. (2006). Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude

– behavioral intention” gap. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 19, 169–194.

Welford, R. (2004). Corporate Social Responsibility in Europe and Asia. Journal of Corporate Citizenship(13), 31–47.

Williams, M. (2008). Going young, green and local. Women’s Wear Daily, 196(7), 10.

Williams, P. R., & Hammitt, J. K. (2001). Perceived risks of conventional and organic produce:

Pesticides, pathogens, and natural toxins. Risk Analysis, 21, 319–330.

World Commission on Environment and Development (1987). Our common future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yoon, H.-S., & Yoon, H.-H. (201 )

3 . A study on the effect of personal consumption values on purchase

intention of environment friendly agricultural products: The moderating effect of environmental

conscious behavior. Korean Academic Society of Hospitality Administration, 22, 253–267.

Young, W., Hwang, K., McDonald, S., & Oates, C. J. (201 )

0 . Sustainable consumption: Green consumer

behaviour when purchasing products. Sustainable development, 18, 20–31.

Zhang, J., & Daugherty, T. (2010). Third-person effect comparison between US and Chinese social

networking website users: Implications for online marketing and word-of-mouth communication.

International Journal of Electronic Marketing and Retailing, 3, 293–315.