Preview text:

Critical Discourse Analysis, Discourse-Historical Approach RUTH WODAK

Lancaster University, UK

Critical discourse studies and the discourse-historical approach

The discourse-historical approach (DHA) belongs in the broadly defined field of criti-

cal discourse studies (CDS), or also critical discourse analysis (CDA) (Reisigl & Wodak,

2001, 2009; Wodak, 2011, 2013). CDS in general investigates language use beyond the

sentence level, as well as other forms of meaning-making such as visuals and sounds,

seeing them as irreducible elements in the (re)production of society via semiosis. CDS

aims to denaturalize the role discourses play in the (re)production of noninclusive and

nonegalitarian structures and challenges the social conditions in which they are embed-

ded. Treated in this way, discourses stand in a mutual relationship with other semiotic

structures and material institutions: They shape them and are shaped by them.

The first study for which the DHA was developed analyzed the constitution of anti-

Semitic stereotyped images as they emerged in public discourses in the 1986 Austrian

presidential campaign of former UN General Secretary Kurt Waldheim, who for a

long time had kept secret his national–socialist past (Wodak et al., 1990). Four salient

characteristics of the DHA emerged in this research project: interdisciplinary and

particularly problem-oriented interests; teamwork; triangulation as a fundamental and

constitutive methodological principle; and orientation toward application. This

interdisciplinary study combined linguistic analysis with historical and sociological,

theoretical and methodological approaches. Moreover, the researchers prepared and

presented an exhibition titled “Postwar anti-Semitism” at the University of Vienna. The

DHA was further elaborated in a number of studies of, for example, discrimination

against migrants from Romania and the discursive construction of nation and national

identity in Austria (Matouschek, Wodak, & Januschek, 1995; Wodak et al., 2009).

The research center “Discourse, Politics, Identity” (DPI) in Vienna, established by

Ruth Wodak as a result of her being awarded the Wittgenstein Prize in 1996 (see

http://www.wittgenstein-club.at), allowed for a shift to comparative interdisciplinary

and transnational projects related to research on European identities and the European

politics of memory (Heer et al., 2008; Kovács & Wodak, 2003; Muntigl, Weiss, & Wodak,

2000). Although the forms of racist and prejudiced discourse may be similar, the con-

tents vary according to the stigmatized groups and according to the settings in which

certain linguistic realizations become possible. This approach has also been applied to

the critical analysis of right-wing politics in Austria and beyond (Wodak, in press).

The International Encyclopedia of Language and Social Interaction, First Edition.

Karen Tracy (General Editor), Cornelia Ilie and Todd Sandel (Associate Editors).

© 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

DOI: 10.1002/9781118611463/wbielsi116 2

CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS, DISCOURSE- HISTORICAL APPROACH

More recently the DHA has also been combined with ethnographic methods in order

to investigate identity politics and patterns of decision-making in EU organizations,

since it offers insights into the “backstage” of politics (Wodak, 2011) as well as into the

exploration of social change in EU countries.

Various principles characterizing the approach have evolved over time since the study

on Austrian postwar anti-Semitism. Here 10 of the most important principles are briefly summarized: 1

The approach is interdisciplinary. Interdisciplinarity involves theory, methods,

methodology, research practice, and practical application. 2

The approach is problem-oriented. 3

Various theories and methods are combined wherever integration leads to an ade-

quate understanding and explanation of the research object. 4

The research incorporates fieldwork and ethnography (study from “inside”) where

this is required for a thorough analysis and theorizing of the object under investi- gation. 5

The research necessarily moves recursively between theory and empirical data. 6

Numerous genres and public spaces as well as intertextual and interdiscursive rela- tionships are studied. 7

The historical context is taken into account in interpreting texts and discourses.

The historical orientation permits the reconstruction of how recontextualization

functions as an important process linking texts and discourses intertextually and interdiscursively over time. 8

Categories and tools are not fixed once and for all. They must be elaborated for each

analysis according to the specific problem under investigation. 9

“Grand theories” often serve as a foundation. In the specific analyses, however,

“middle-range theories” frequently supply a better theoretical basis. 10

The application of results is an important target. Results should be made available

to and applied by experts and should be communicated to the public.

Many theoretical and also methodological concepts used in DHA are equally valid

for other strands in CDS, even if their contexts of emergence have generated differ-

ent toolkits. Still, these approaches draw on each other, thereby reproducing a common

conceptual frame while they develop their own distinct orientations. The DHA is dis-

tinctive both at the level of research interest and theoretical and methodical orientation

(where it displays an interest in identity construction and in unjustified discrimina-

tion and a focus on the historical dimensions of discourse formation) and with respect

to its epistemological foundation—that is, with respect to its being oriented toward

the critical theory of the Frankfurt School, and in particular with Habermas’s language philosophy.

One of the main principles of the DHA is that of triangulation, which enables the

researchers to minimize any risk of being too subjective. This is due to its endeavor

to work on a basis of a variety of different data, methods, theories, and background

information (Wodak, 2011, p. 65):

CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS, DISCOURSE- HISTORICAL APPROACH 3

The DHA attempts to integrate a large quantity of available knowledge about the historical sources

and the background of the social and political fields in which discursive “events” are embedded.

Further, it analyzes the historical dimension of discursive actions by exploring the ways in which

particular genres of discourse are subject to diachronic change. Lastly, and most importantly, this is

not only viewed as information. At this point we integrate social theories to be able to explain the so-called context.

Critique, ideology, and power

The DHA adheres to the sociophilosophical orientation of critical theory. This is why

it follows a concept of social critique that integrates three related aspects (for extended

discussions, see Reisigl & Wodak, 2009): 1

Text or discourse-immanent critique aims at discovering inconsistencies, (self-)

contradictions, paradoxes, and dilemmas in the text-internal or discourse-internal structures. 2

Sociodiagnostic critique is concerned with demystifying the—manifest or

latent—persuasive or “manipulative” character of discursive practices. Here we

make use of our contextual knowledge; we also draw on social theories and other

theoretical models from various disciplines to interpret the discursive events. 3

Future-related prospective critique seeks to contribute to the improvement of com-

munication (for example, by elaborating guidelines against sexist language behavior

or by reducing “language barriers” in hospitals, schools, and so forth).

Hence this understanding of critique implies that the DHA should make the object

under investigation and the analyst’s own position transparent and should justify theo-

retically why certain interpretations and readings of discursive events seem more valid than others.

Reisigl and Wodak (2001) make clear what their preferred political model is—and

this is not, of course, simply an endorsement of the current political regime in their own

country. From a theoretical standpoint, the ideas of Habermas (1996) are of fundamen-

tal importance. The key concepts are those of a public sphere and of a “deliberative

democracy,” in which free and equal participation in debate, critique, and decision-

making are guaranteed by the rule of law (Reisigl & Wodak, 2001, p. 34):

The political model that, in our view, would best help to institutionalise and unfold this form of

critique is that of a “deliberative democracy” based on a free public sphere and a strong civil society,

in which all concerned with the specific social problem in question can participate. Within such

a political frame … the communicative structures of the public sphere can be functionalised as a

wide network of sensors that allow one to deal with, to differentiate and to react to social and polit-

ical problems of legitimation and to control and influence the use of political—legislative, judicial,

administrative and executive—power (Habermas 1996: 290). This model of democracy, which is

also a theory of rational argumentation … and discursive conflict solving … particularly focuses

on the concepts of “deliberation” and “discourse” as well as on the critical function of the public. Its

proponents assume that language is the central medium of democratic organisation and free public

exchange of different interests, wishes, viewpoints, opinions and arguments is vital for a pluralistic 4

CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS, DISCOURSE- HISTORICAL APPROACH

democracy in a modern decentred society, since it is essential for deliberatively and justly organising

the different preferences, and since it can also have a critical influence on the relationship between

legality and administrative power changes.

From the point of view of the DHA, ideology is defined as an (often) one-sided perspec-

tive or worldview composed of related mental representations, convictions, opinions,

attitudes, and evaluations. Ideologies are shared by members of specific social groups.

Ideologies serve as an important means of establishing and maintaining unequal power

relations through discourse: for example, by establishing hegemonic identity narratives

or by controlling the access to specific discourses or public spheres (“gate-keeping”).

Thus the DHA focuses on the ways in which linguistic and other semiotic practices

mediate and reproduce ideology in a range of social institutions. One of the explicit and

most important aims of the DHA is to “demystify” the hegemony of specific discourses

by deciphering the underlying ideologies.

For the DHA, language is not powerful on its own; it is a means to gain and main-

tain power through the use that powerful people make of it. “Power” is an asymmetric

relationship among social actors who assume different social positions or belong to dif-

ferent social groups. Following Weber (1980), researchers in the DHA tradition view

“power” as the possibility of establishing one’s own will within a social relationship

and against the will of others. Some of the ways in which power is implemented are

physical force and violence, control of people through threats or promises (disciplining

regimes), attachment to authority (exertion of authority and submission to authority),

and technical control with the help of objects such as means of production, means of

transportation, weapons, and so on.

Power relations are legitimized or delegitimized in discourses. Texts are often sites of

social struggle in that they manifest traces of differing ideological fights for dominance

and hegemony. Thus, in the in-depth analysis of texts, the DHA focuses on the ways

in which linguistic forms are used in various expressions and manipulations of power.

Power is discursively exerted not only by grammatical forms, but also by a person’s

control of the social occasion by means of the genre of a text, or by the regulation of

access to certain public spheres.

“Discourse,” “text,” “context”

The DHA is problem-oriented. This implies that the study of (oral, written, visual) lan-

guage necessarily remains only a part of the research; hence the investigation must be

interdisciplinary. Moreover, in order to analyze, understand, and explain the complex-

ity of the objects under investigation, many different and accessible sources of data (in

respect of external constraints such as time, funding, etc.) are analyzed from various

analytical perspectives. Thus, as mentioned above, the principle of triangulation is very

important; and this implies taking into account a whole range of empirical observa-

tions, theories, and methods—as well as background information. In consequence, the

concept of context is an inherent part of the DHA and contributes to its triangulatory

principle, which takes into account four levels:

CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS, DISCOURSE- HISTORICAL APPROACH 5 1

the immediate, language, or text-internal cotext; 2

the intertextual and interdiscursive relationship between utterances, texts, genres, and discourses; 3

the extralinguistic social variables and institutional frames of a specific “context of situation”; 4

the broader sociopolitical and historical context, which discursive practices are embedded in and related to.

In the analysis, the DHA is oriented toward all four dimensions of context, in a recursive manner.

Reisigl and Wodak (2009, p. 87) define “discourse” as: •

a cluster of context-dependent semiotic practices that are situated within specific fields of social action; •

socially constituted and socially constitutive; • related to a macrotopic; •

linked to the argumentation about validity claims—for example to truth and nor-

mative validity, which involves several social actors with different points of view.

Thus Reisigl and Wodak regard macrotopic relatedness, pluriperspectivity, and argu-

mentativity as constitutive elements of a discourse. The question of delimiting the bor-

ders of a “discourse” and of differentiating it from other “discourses” is complex and

intricate: The boundaries of a “discourse” (such as the one on racism or global warm-

ing) are partly fluid. As an analytical construct, a “discourse” always depends on the

discourse analyst’s perspective. As an object of investigation, a discourse is not a closed

unit, but a dynamic semiotic entity that is open to reinterpretation and continuation.

Furthermore, Reisigl and Wodak (2009, p. 89) distinguish between “discourse” and

“text”: Texts are parts of discourses. They make speech acts durable over time and thus

bridge two dilated speech situations: the situation of speech production and the situ-

ation of speech reception. In other words, texts—be they visualized (and written) or

oral—objectify linguistic actions.

Texts are always assigned to genres. A “genre” may be characterized as a socially

ratified way of using language in connection with particular types of social activity.

Consequently, a manifesto on combating global warming proposes certain rules and

expectations according to social conventions and has specific social purposes. A dis-

course on climate change, for example, is realized through a range of genres and texts,

for example TV debates on the politics of a particular government on climate change,

guidelines to reduce energy consumption, speeches or lectures by experts, and so forth.

The DHA considers intertextual and interdiscursive relationships between utter-

ances, texts, genres, and discourses as well as extralinguistic social or sociological

variables, the history of an organization or institution, and situational frames. While

focusing on all these levels and layers of meaning, researchers explore how discourses,

genres, and texts change in relation to sociopolitical change.

Intertextuality means that texts are linked to other texts, both in the past and in the

present. Such connections are established in different ways: through explicit reference 6

CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS, DISCOURSE- HISTORICAL APPROACH

to a topic or main actor; through references to the same events; through allusions or

evocations; through the transfer of main arguments from one text to the next, and so

on. A newspaper article, for example, might refer to another article published some time

ago; or an incident reported in the newspaper might refer to a news agency report, and

so forth. In policy papers of the European Union there are always numerous links to

other policy papers in a related area listed at the outset, which allow readers to connect

the respective policy immediately with a set of intertextually important other policies.

Indeed it is almost impossible to understand a specific policy without considering the

other policies listed in the first paragraph (see Example 1). EXAMPLE 1

Follow-up to the European Parliament Resolution on Multilingualism: An asset for Europe

and a shared commitment, adopted by the Commission on 17 June 2009 1

Rapporteur: Vasco GRAÇA MOURA (EPP-ED/PT) 2

EP reference number: A6-0092/2009 / P6-TA_PROV(2009)0162 3

Date of adoption of the resolution: 24 March 2009 4

Subject: Multilingualism: an asset for Europe and a shared commitment 5

Competent Parliamentary Committee: Committee on Culture and Education (CULT) 6

Brief analysis/assessment of the resolution and requests made in it:

The Commission welcomes the resolution which contains the key elements of the

Communication on multilingualism adopted in September 2008 [footnote],

underlining the importance of multilingualism and the fact that respect for

linguistic diversity is an essential European Union value. The Commission agrees

with most of the comments set out in the resolution and is pleased to note that

the European Parliament and the Commission are on the same wavelength in this

respect. It also considers that the own-initiative report and the resolution will pro-

vide much food for thought in the context of the Commission’s future measures

and programmes. (Follow-up on European Union resolution on multilingualism,

http://www.google.at/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&frm=1&source=web&cd=

4&ved=0CD8QFjAD&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.europarl.europa.eu%

2Foeil%2Fspdoc.do%3Fi%3D16808%26j%3D0%26l%3Den&ei=LLxjU6yLEsi

p0QXE04GwDQ&usg=AFQjCNEL8Lh56GeBOgQmJCBlYobT2T0okg&

bvm=bv.65788261,d.d2k, accessed May 2, 2014)

In Example 1 many features of the genre of policy papers are evident, such as the layout

or the categorization via numbers, dates, setting, and the name of the rapporteur who

addressed this resolution in the European Parliament. The intertextuality is illustrated

by the footnote (marked [footnote] in the example), which refers to (1) the policy

paper (COM) proposed by the Commission: COM(2008)566, 18.9.2008; (2) the reso-

lution of the European Parliament related to the policy: 24.3.2009; and (3) the follow-

up: 17.6.2009. This trajectory over time and over different spaces also illustrates the

complex decision-making procedures in European Union organizations, the so-called

codecision-making procedure (see Wodak, 2011, p. 69). To be able to understand the

CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS, DISCOURSE- HISTORICAL APPROACH 7

brief extract above, it is necessary to have read the previous documents that are inter-

textually referred to, as well as to be briefed about the points of agreement and disagree- ment under discussion.

The process of transferring given elements to new contexts is labeled recontextual-

ization. If an element is taken out of a specific context, we observe a process of decon-

textualization; if the respective element is then inserted into a new context, we witness

a process of recontextualization. The element (partly) acquires a new meaning, since

meanings are formed in use of language (see Wittgenstein, 1967). Recontextualization

can be observed when contrasting, for instance, a political speech with the selective

reporting of that speech in various newspapers. A journalist will select specific quota-

tions, which best fit the general purpose of the article (e.g., commentary). The quota-

tions are thus de- and recontextualized, that is, newly framed. They can partly acquire

new meanings in the specific context of press coverage, if, say, the respective report

focuses solely on this one quote without taking the source text into detailed considera- tion (see Example 2).

Interdiscursivity signifies that discourses are linked to each other in various ways.

If “discourse” is primarily defined as topic-related (as “discourse on x”), then a dis-

course on climate change frequently refers to topics or subtopics of other discourses,

such as finances or health. The same is true for discourses about unemployment, which

frequently draw on discourses about immigration, financial crisis, or issues of security.

Thus discourses are open and often hybrid; new subtopics can be created at many points. EXAMPLE 2 The Times

Rioting Blacks Shot Dead by Police as ANC Leaders Meet

Eleven Africans were shot dead and 15 wounded when Rhodesian police opened fire on

a rioting crowd in the African Highfield township of Salisbury this afternoon. The Guardian

Police Shoot 11 Dead in Salisbury Riot

Riot police shot and killed 11 African demonstrators and wounded 15 others here today

in the Highfield African township of Salisbury this afternoon. Tanzanian Daily News Racists Murder Zimbabweans

Rhodesia’s white supremacist police had a field day on Sunday when they opened

fire and killed thirteen unarmed Africans, in two different actions in Salisbury; and wounded many others.

Even in the absence of an in-depth analysis of the two British newspapers and one local

Tanzanian newspaper that reported the same incident from June 2, 1975 (Hyland &

Paltridge, 2013, pp. 215–216), it is easy to detect the significantly different ways in

which the shooting was reported, and thus recontextualized: in the Times, the killed

African people are labeled “rioting blacks” and the shooting is reported in the passive

voice, whereas the Guardian talks about “demonstrators” (and not rioting blacks) and

qualifies the police as the “riot police,” making it an active subject (and not a passive

one): It clearly represents the police as shooting the demonstrators. The Guardian does

not spread an image of chaos either. Through the description “demonstrators” (and not Table 1

A selection of discursive strategies. Strategy Objectives Devices Referential/

Discursive construction of social

membership categorization devices, deictics, nomination actors, objects/phenomena/ anthroponyms, etc. events, and processes/actions

tropes such as metaphors, metonymies, and

synecdoches (pars pro toto, totum pro parte)

verbs and nouns used to denote processes and actions Predication

Discursive qualification of social

stereotypical, evaluative attributions of actors, objects, phenomena/

negative or positive traits (e.g., in the form events/processes, and actions

of adjectives, appositions, prepositional (more or less positively or

phrases, relative clauses, conjunctional negatively)

clauses, infinitive clauses, and participial clauses or groups)

explicit predicates or predicative nouns/ adjectives/pronouns collocations

explicit comparisons, similes, metaphors,

and other rhetorical figures (including

metonymies, hyperboles, litotes, euphemisms)

allusions, evocations, and presuppositions/ implicatures other Argumentation

Justification and questioning of

topoi (formal or more content-related) claims of truth and fallacies normative rightness deictics Perspectivization,

Positioning speaker’s or writer’s framing, or point of view and expressing

direct, indirect or free indirect speech discourse involvement or distance

quotation marks, discourse markers/particles representation metaphors animating prosody other Modifying (intensifying or diminutives or augmentatives Intensification, mitigation mitigating) the illocutionary

(modal) particles, tag questions, subjunctive, force and thus the epistemic

hesitations, vague expressions, etc.

or deontic status of utterances hyperboles, litotes

indirect speech acts (e.g., question instead of assertion)

verbs of saying, feeling, thinking other

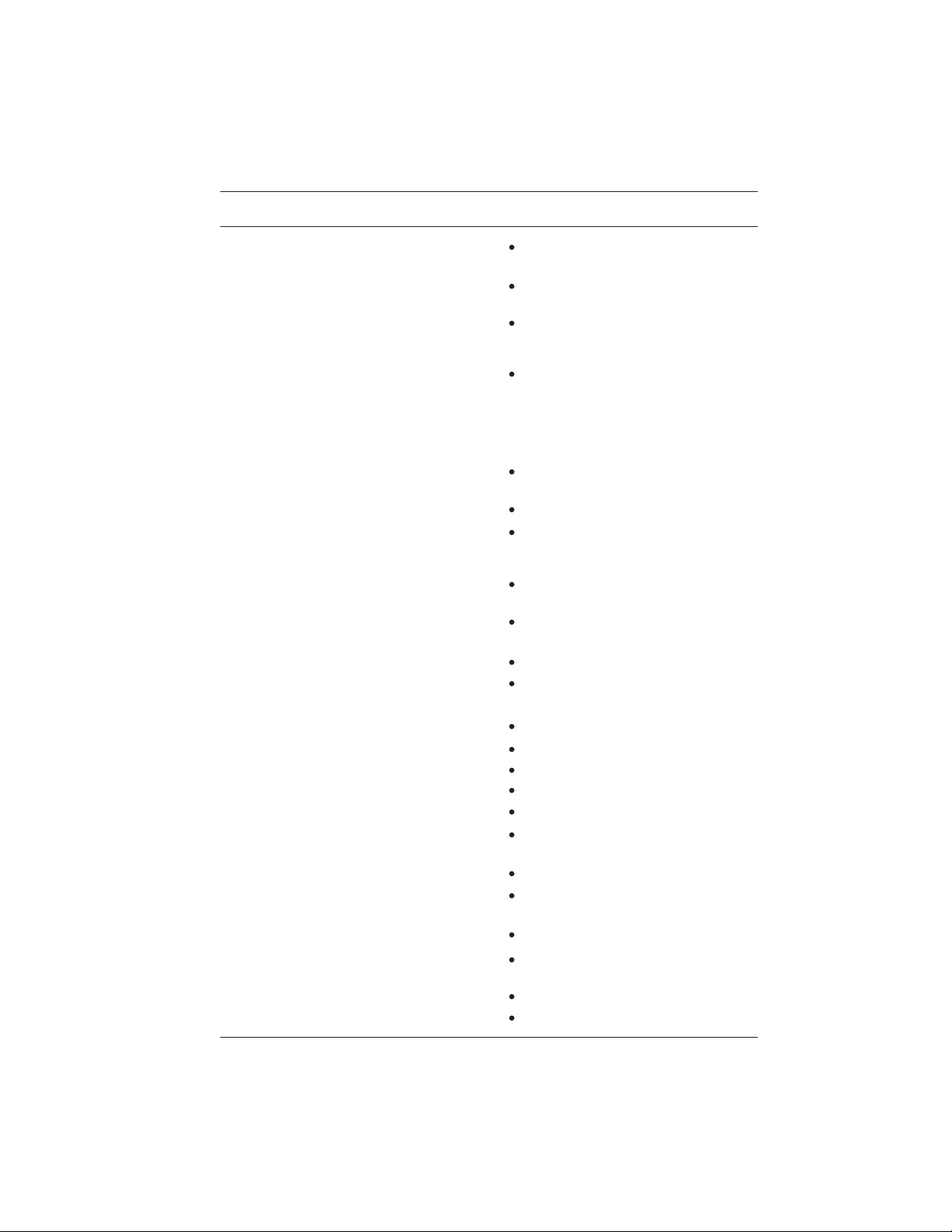

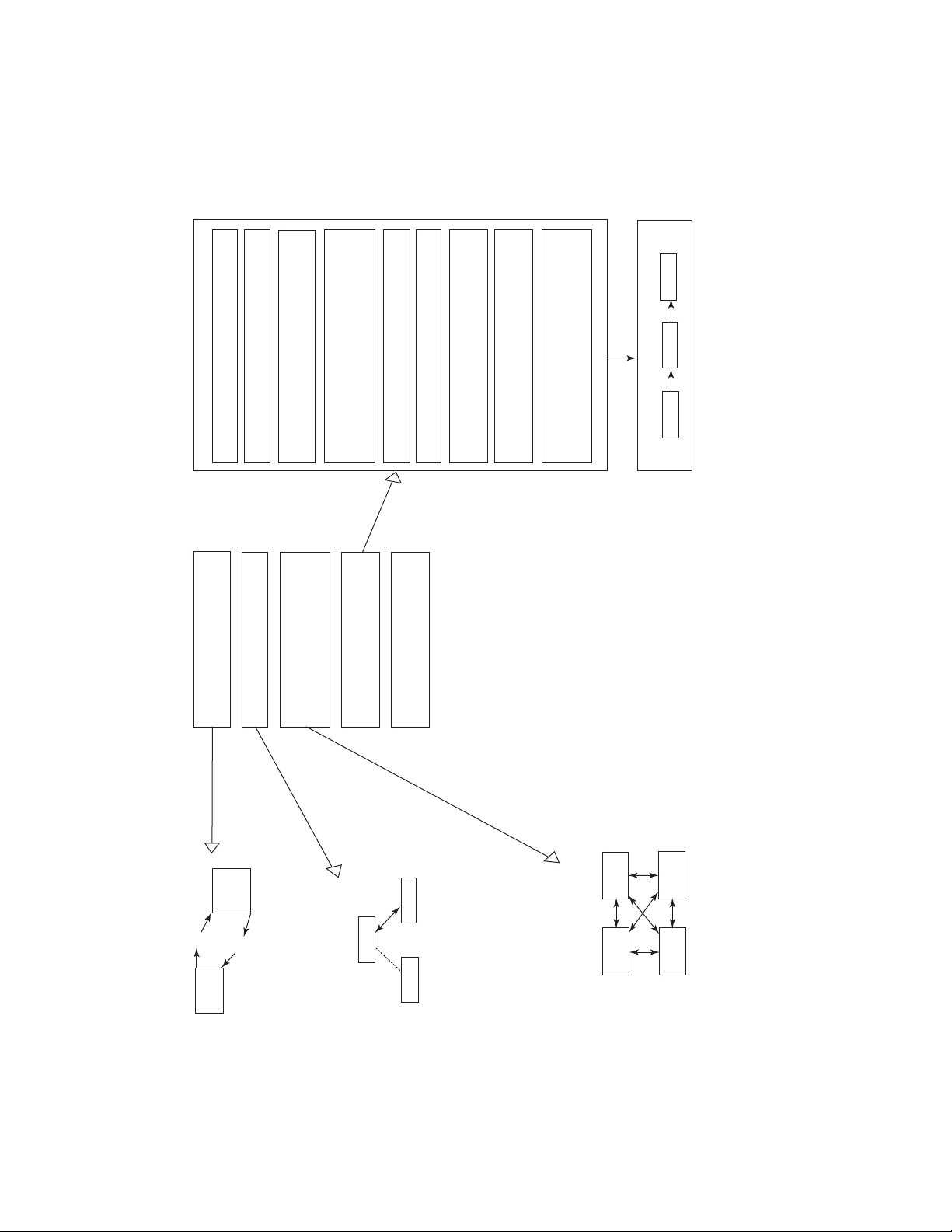

Source: Adapted from Reisigl and Wodak, 2009, p. 104. Field of action: Political control Political (sub)genres: declaration of an opposition party, parliamentary question, speech of an MP, heckling, speech of protest, commemo- rative speech (especially admonitory or blaming speech), election speech, press release, petition for a referendum, etc. Discourse topic 12 Field of action: administration olitical (sub)genres: P decision (approval, rejection), chancellor speech (e.g., inaugural speech), minister speech, major speech, speech of resignation, farewell speech, speech of appoint- ment, state of the union address, governmental answer to a parliamentary question, etc. Discourse topic 11 Political executive and nres: Field of action: Political advertising Political (sub)ge election programme, election slogan, election speech, election brochure, announcement, poster, flier, direct mailing, commemorative speech, speech of an MP, state of the union address, etc. Discourse topic 9 Discourse topic 10 relations Field of action: Organisation of international/interstate Discourse topic 8 Political (sub)genres: speech on the occasion of a state visit, inaugural address, speech in meeting /sitting/summit of supranational organization (Euro- pean Union, United Nations, etc.), war speech, declaration of war, hate speech, peace speech, commemorative speech, note, ultimatum (international) treaty, etc. Discourse topic 7 ics. p to and will se Field of action: ur attitudes, opinions, Political (sub)genres: Inter-party formation of coalition negotiation, coalition programme, coalition paper/ contract/agreement, speech in an inter- party or government meeting/sitting, inaugural speech (in the case of a coalition government), commemorative speech, etc. co Discourse topic 6 is d Discourse topic 5 d an es, and will genr Field of action: Party-internal formation of attitudes, opinions, Political (sub)genres: party programme, declaration, speech at a party convention or in a party meeting, speech or statement of principal, party jubilee speech, etc. tical li Discourse topic 4 o .41. Discourse topic 3 p p n, 2011, and will actio Field of action: dak, Formation of public attitudes, opinions, tical o Political (sub)genres: press release, press conference, interview, talk show, president speech, speech of an MP (especially if broadcast) opening speech, commemo- rative speech, jubilee speech, radio or TV speech, chancellor speech (e.g., inaugural speech), minister speech, election speech, state of the union address, lecture and contribution to a conference, (press) article, book, etc. li o W Discourse topic 2 p f m o Discourse topic 1 fro ted Fields p da Field of action: 1 A Lawmaking procedure Political (sub)genres: law, bill, amendment, parliamentary speech, and contribution of MPs (including heck- ling and question by political opponent), minister speech, state of the union address, regulation, recommendation, prescription, guideline, etc. re ce: u g ur Fi So 1 0

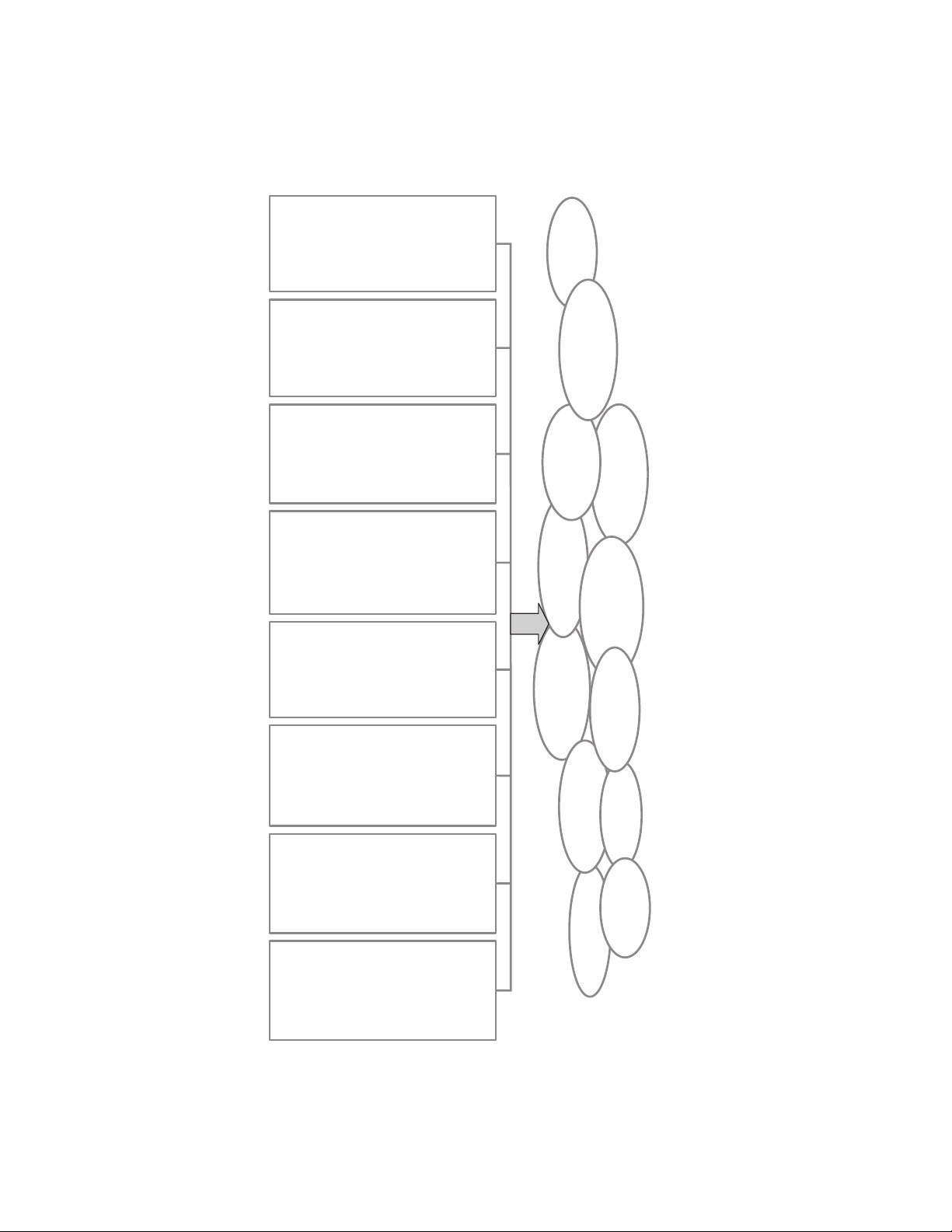

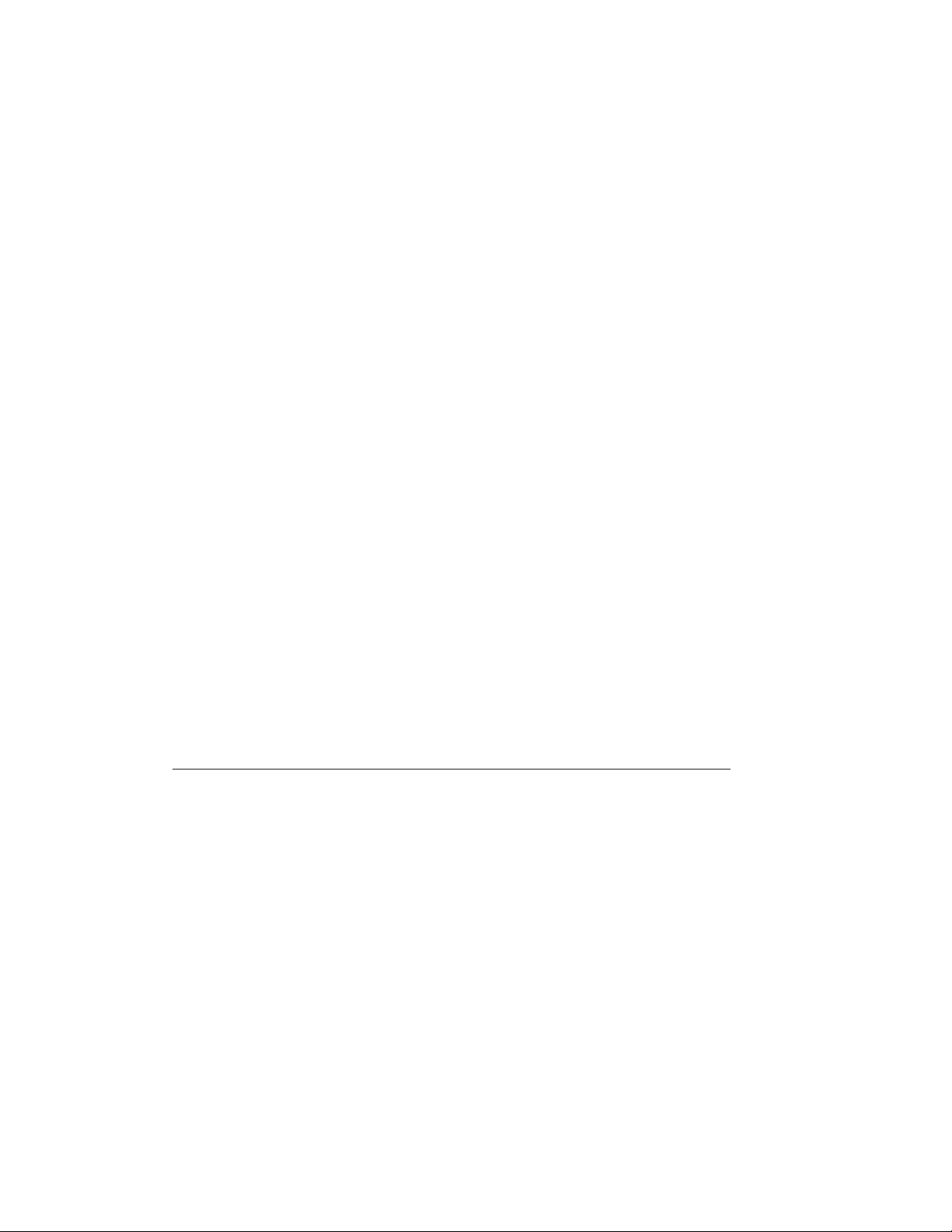

CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS, DISCOURSE- HISTORICAL APPROACH Discourse A Discourse B Genre x Genre y Genre z Genre u Text x Text yz Text u Time axis Topic x Topic yz Topic u 1 1 1 Topic x Topic yz Topic u 2 2 2 Topic x Topic yz 3 3 Figure 2

Interdiscursive and intertextual relationships between discourses, discourse topics, genres, and texts.

Source: Adapted from Reisigl & Wodak, 2009, p. 93.

“rioting crowd”), the activity is also connoted differently—demonstrations are legal

and usually peaceful; riots are chaotic and usually imply violence of some kind. In

contrast, the Times justifies the shooting by mentioning a “rioting crowd.” The Tan-

zanian Daily News also attributes the action to the police, whose members are qualified

as “racists” and “white supremacist”; thus they are indicated as perpetrators and the

Africans are indicated as victims. Moreover, the Tanzanian Daily News writes about 13

people killed—and not 11, as recontextualized in the two British newspapers. No riots

are mentioned, and it is clearly stated that the Africans were unarmed, hence inno-

cent. These three brief examples, which have been used in many textbooks, illustrate

different narratives and different frames of the incident (who are the agents, who the

perpetrators, who are the victims?) and tell different stories. In this way three styles of

news-reporting can be detected, as well as different underlying ideologies that explain

the same incident from three different perspectives (see the five discursive strategies for

self- and other presentation elaborated in Table 1).

“Field of action” (Wodak, 2011) indicates a segment of social reality, a field that

constitutes the “frame” of a discourse. Different fields of action are defined by differ-

ent functions of discursive practices. For example, in the arena of political action, the

DHA differentiates between eight different political functions as eight different fields

(see Figure 1). A “discourse” about a specific topic can find its starting point within one

field of action and proceed through another one. Discourses then spread to different

fields and relate to or overlap with other discourses.

Figure 2 further illustrates the interdiscursive and intertextual relationships between

discourses, discourse topics, genres, and texts: In this diagram interdiscursivity is indi-

cated by the two big overlapping ellipses. Intertextual relationships are represented by

dotted double arrows. The assignment of texts to genres is signaled by simple arrows.

The topics to which a text refers are indicated by small ellipses with simple dotted

arrows; the topical intersection of different texts is indicated by the overlapping small

ellipses. Finally, the specific intertextual relationship of thematic reference of one text

to another is signaled by simple broken arrows.

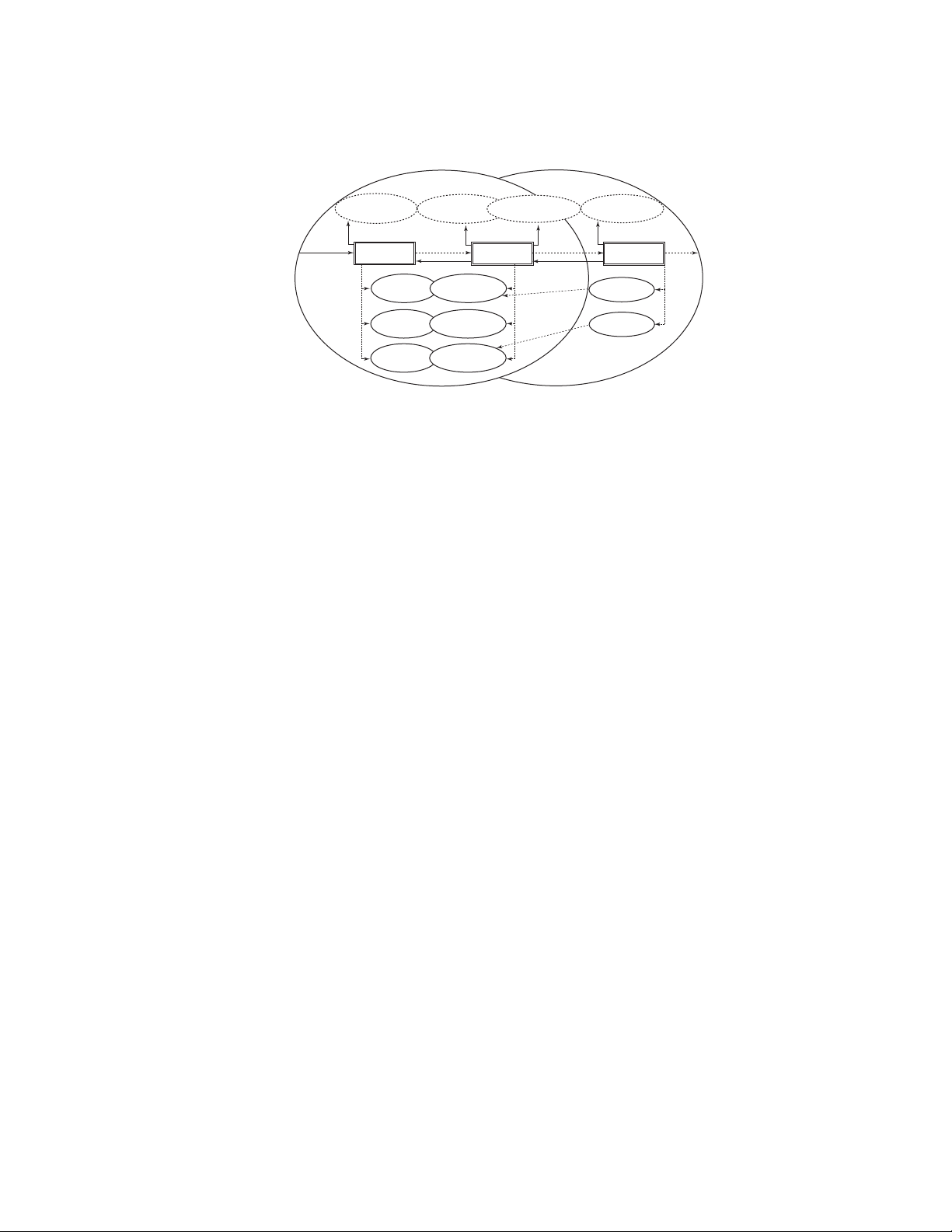

CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS, DISCOURSE- HISTORICAL APPROACH 1 1 Conclusion Topoi Warrant

if an institution is burdened by a

if sufficient numerical/statistical if one refers to somebody in a

a person or thing is designated X

decisions or actions need to be

tautologically infers that as reality as it

because history teaches that specific

if persons/actions/situations are equal

if specific dangers or threats are Argumentation schema Premise

How an issue should be dealt with Topos of Burdening –

specific problem, then one should act to diminish it Topos of Reality –

is, a particular action should be performed Topos of Numbers –

evidence is given, a specific action should be performed Topos of History –

actions have specific consequences, one should

perform or omit a specific action in a specific situation Topos of Authority –

position of authority, then the action is legitimate Topos of Threat –

identified, one should do something about them

Topos of Definition –

should carry the qualities/traits/attributes consistent with the meaning of X Topos of Justice –

in specific respects, they should be treated/dealt with in the same way Topos of Urgency –

drawn/found/done very quickly because of an

external, important, and unchangeable event

beyond one’s reach and responsibility. content (warrants) Establish the internal logic of the argument (how the issue with) through should be dealt form (topic) and the the labelling of the framing or positioning the justification of positive the construction of in-groups Discursive Strategies

Predication/Nomination –

social actors, positively or negatively,

appreciatively or depreciatorily Referential – and out-groups Perspectivation –

of the speaker’s point of view through

the statement of assumptions and/or acts of interdiscursivity Argumentation –

or negative attributions through topoi in

the form of argumentation schema

Intensification/Mitigation – modification of the epistemic importance of a proposition field of action/ Reinforce the speaker, b) the discourse topic control and c) the speaker’s legitimacy by aligning the issue at hand with: a) the relevant i. o p

Identify a certain actor or or opportunity posed by .44.

collective, inferring a threat

their behaviour or interests. opposition by distinguishing to p Mobilize support for an issue and ‘allies’ and out- diminish potential between in-group group ‘opposition’ d an topic Issue 2011, Discourse ies Named actor or collective In-group teg dak, ra o st W Opportunity e m Speaker Threat Establishing legitimacy Speaker Field of action fro Mobilizing support cursiv ted Out-group Dis p Speaker da

Inferring opportunity or threat 3 A re ce: u g ur Fi So 1 2

CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS, DISCOURSE- HISTORICAL APPROACH

Some tools of analysis and principles of DHA

The DHA is three-dimensional: after (1) having identified the specific contents or top-

ics of a specific discourse, (2) discursive strategies are investigated. Then (3) linguistic

means are examined as types, and the specific, context-dependent linguistic realizations

are examined as tokens. This implies analyzing the coherence of the text by first detect-

ing the macrotopics and related subtopics. Second, it is important to understand the

aim of the text producer in a specific genre: Does the speaker intend to convince some-

body and thus to realize a persuasive text? Or to tell a story? Or to select a more factual

mode and report an incident? Depending on the aim, different strategies and linguistic,

pragmatic, and rhetorical devices are used to realize the intended meaning.

There are several strategies that deserve special attention when analyzing a specific

discourse and related texts in relation to the discursive construction and representation

of “us” and “them.” Heuristically, one could orient to five questions: 1

How are persons, objects, phenomena/events, processes, and actions named and referred to linguistically? 2

What characteristics, qualities, and features are attributed to social actors, objects,

phenomena/events, and processes? 3

What arguments are employed in the discourse in question? 4

From what perspective are these nominations, attributions, and arguments expressed? 5

Are the respective utterances articulated overtly? Are they intensified or mitigated?

According to these five questions, five types of discursive strategies can be distinguished.

By “strategy” is meant a more or less intentional plan of practices (including discur-

sive practices), adopted in order to achieve a particular social, political, psychological,

or linguistic goal. Discursive strategies are located at different levels of linguistic orga-

nization and complexity (Table 1 lists the important strategies and related linguistic

devices; Figure 3 summarizes the most important categories of the DHA).

Approaching the analysis of “discourses about x”: The DHA in eight steps

A thorough discourse-historical analysis ideally follows an eight-stage program. Typi-

cally, the eight steps are implemented recursively: 1

literature review, activation of theoretical knowledge (i.e., recollection, reading, and

discussion of previous research); 2

systematic collection of data and context information (depending on the research

questions, various discourses, genres, and texts are focused on); 3

selection and preparation of data for specific analyses (selection and downsizing of

data according to relevant criteria, transcription of tape recordings, etc.);

CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS, DISCOURSE- HISTORICAL APPROACH 1 3 4

specification of the research questions and formulation of assumptions (on the basis

of a literature review and a first skimming of the data); 5

qualitative pilot analysis (this allows for testing categories and first assumptions as

well as for the further specification of assumptions); 6

detailed case studies (of a whole range of data, primarily qualitatively, but in part also quantitatively); 7

formulation of critique (interpretation of results, taking into account the relevant

context knowledge and referring to the three dimensions of critique); 8

application of the detailed analytical results (if possible, the results might be applied or proposed for application).

This ideal or typical list is best realized in a big interdisciplinary project with enough

resources of time, personnel, and money. Given the funding, the time available, and

other constraints, smaller studies are, of course, useful and legitimate. Nevertheless, it

makes sense to be aware of the thorough overall research design, and thus to make

explicit choices when devising one’s own project. In a PhD thesis, for example, one can

certainly conduct only a few case studies and must restrict the range of the data collec-

tion to very few genres. Sometimes a pilot study can be extended to more comprehensive

case studies, and occasionally case studies planned at the very beginning must be left for a follow-up project.

Current and future research in the DHA involves integrating new genres, theories

about globalization, and new socioeconomic developments, as well as developing and

employing methodologies that are adequate for analyzing comic books, images, posters,

leaflets, films, TV soaps, and new social media.

SEE ALSO: Critical Discourse Analysis; Ecolinguistic Discourse Analysis; Interdiscur-

sivity; Intertextuality; Migration Discourse; Political Discourse Analysis References

Habermas, J. (1996). Die Einbeziehung des Anderen: Studien zur politischen Theorie. Frankfurt, Germany: Suhrkamp.

Heer, H., Manoschek, W., Pollak, A., & Wodak, R. (Eds.). (2008). The discursive construction of

history: Remembering the Wehrmacht’s war of annihilation. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave.

Hyland, K., & Paltridge, B. (Eds.). (2013). Bloomsbury companion to discourse analysis. London, UK: Bloomsbury.

Kovács, A., & Wodak, R. (Eds). (2003). Nato, neutrality and national identity: The case of Austria

and Hungary. Vienna, Austria: Böhlau.

Matouschek, B., Wodak, R., & Januschek, F. (1995). Notwendige Maßnahmen gegen Fremde?

Genese und Formen von rassistischen Diskursen der Differenz. Vienna, Austria: Passagen Ver- lag.

Muntigl, P., Weiss, G., & Wodak, R. (2000). European Union discourses of un/employment: An

interdisciplinary approach to employment policy-making and organizational change. Amster-

dam, Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Reisigl, M., & Wodak, R. (2001). Discourse and discrimination: Rhetorics of racism and anti-

semitism. London, UK: Routledge. 1 4

CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS, DISCOURSE- HISTORICAL APPROACH

Reisigl, M., & Wodak, R. (2009). The discourse-historical approach. In R. Wodak & M. Meyer

(Eds.), Methods of critical discourse analysis (2nd ed., pp. 87–121). London, UK: Sage.

Weber, M. (1980). Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft (5th ed.). Tübingen, Germany: Mohr.

Wittgenstein, L. (1967). Philosophische Untersuchungen. Frankfurt, Germany: Suhrkamp.

Wodak, R. (2011). The discourse of politics in action: Politics as usual (2nd ed.). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave.

Wodak, R. (Ed). (2013). Critical discourse analysis. London, UK: Sage.

Wodak, R. (in press). The politics of fear: Rightwing populist rhetoric across Europe. London, UK: Sage.

Wodak, R., de Cillia, R., Reisigl, M., & Liebhart, K. (2009). The discursive construction of national

identity (2nd ed.). Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press.

Wodak, R., Nowak, P., Pelikan, J., Gruber, H., de Cillia, R., & Mitten, R. (1990). “Wir sind alle

unschuldige Täter!” Diskurshistorische Studien zum Nachkriegsantisemitismus. Frankfurt, Ger- many: Suhrkamp.

Ruth Wodak is distinguished professor and chair of discourse studies at Lancaster

University, UK. She is member of the Academia Europaea and Fellow of the British

Academy of Social Sciences (FAcSS). She is former president of the Societas Linguistica

Europaea (SLE). Her research interests focus on national and European identity politics

and politics of the past; racism, anti-Semitism and xenophobia; and organizational

discourse. Wodak is coeditor of The Handbook of Sociolinguistics (2010) and The

Handbook of Language and Politics (in press), and coeditor of the Journal of Language

and Politics, Critical Discourse Studies, and Discourse & Society. Recent monographs

include The Discourse of Politics in Action: Politics as Usual (2011) and The Politics of

Fear: Rightwing Populist Rhetoric across Europe (in press).