Preview text:

ADVERSITY QUESTIONNAIRE CORRESPONDENCE

Running head: ADVERSITY QUESTIONNAIRE CORRESPONDENCE

Correspondence between the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire

and Adverse Childhood Experiences questionnaire Theresa W. Cheng ,

1,2 Martin H. Teicher , Kristen Mackiewicz 3 -Seghete4 1 2

Masschusetts General Hospital, University of Oregon,

3McLean Hospital and Harvard Medical School,

4Oregon Health & Sciences University Author Note

Theresa W. Cheng, Psychiatric & Neurodevelopmental Genetics Unit, Massachusetts

General Hospital and Dept. of Psychology, University of Oregon., Martin H. Teicher,

Developmental Biopsychiatry Research Program, McLean Hospital, and Dept. of Psychiatry,

Harvard Medical School, Kristen Mackiewicz-Seghete, Dept. of Behavioral Neuroscience,

Oregon Health & Sciences University.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Theresa W. Cheng,

Psychiatric and Neurodevelopmental Genetics Unit, Simches Research Building, 185 Cambridge

Street, Boston, MA 02114, Email: t wcheng@mgh.harvard.edu .

Author TWC was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

of the National Institutes of Health under award number TL1TR002371 and by the National

Institute of Mental Health under award number 1F31MH124353-01. The content is solely the

ADVERSITY QUESTIONNAIRE CORRESPONDENCE

responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National

Institutes of Health. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

ADVERSITY QUESTIONNAIRE CORRESPONDENCE Abstract

Childhood adversity is commonly measured via retrospective self-report on the Adverse

Childhood Experiences (ACE) questionnaire and the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ).

To facilitate comparison of studies and data employing these measures, we employed a variety of

approaches to equate CTQ and ACE questionnaire responses pertaining to emotional, physical,

and sexual abuse, as well as emotional and physical neglect. The accuracy, sensitivity, and

specificity of these approaches suggest moderate to strong levels of questionnaire

correspondence in a sample of middle-class young adults living in the United States (N=471; 273

female; mean age=23 years, SD=1.7 years) across maltreatment types, except for physical

neglect (which exhibited poorer and more variable correspondence across approaches). Results

in a validation sample (N=64; 43 female; mean age=19.1, SD=0.5) did not suggest model

overfitting. We also provide an interactive web-based tool to examine questionnaire

correspondence across approaches.

Keywords: childhood adversity, childhood maltreatment, adverse childhood experiences,

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, measurement

ADVERSITY QUESTIONNAIRE CORRESPONDENCE Introduction

Childhood adversity is a significant risk factor for physical and mental health problems

(e.g., Felitti et al., 1998; Gilbert et al., 2015). While diverse measures are used to assess

exposures to such adversities, their comparability is rarely considered. Two of the most used

retrospective self-report measures of childhood adversity are the Adverse Childhood Experiences

(ACE) questionnaire and the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) (Norman et al., 2012).

This report aims to provide a quantitative basis for understanding the comparability of these

questionnaires, specifically regarding the way they measure maltreatment. Addressing this may

help resolve inconsistencies in the literature and shed insight into when it may be appropriate to

collapse across samples using different measures in secondary data analyses.

These questionnaires were each developed for distinct purposes within different

disciplinary traditions. Early on, the ACE questionnaire was administered via mail-in surveys to

study the impacts of childhood adversity on mortality risks (Felitti et al., 1998). ACE screening

has been adopted in healthcare settings (Koita et al., 2018) and proposed in policy (e.g., ACEs

Aware initiative; www.acesaware.org), though some caution against this (Finkelhor, 2018). The

ACE questionnaire commonly assesses five types of childhood maltreatment (emotional,

physical, and sexual abuse; emotional and physical neglect) and experiences characterized as

household dysfunction (e.g., witnessing domestic violence or the incarceration of a caregiver),

though versions vary. The questionnaire is not psychometrically ideal in its use of single binary

items for each exposure. However, its brevity facilitates ease of administration, and typical uses

emphasize cumulative risk rather than an accurate assessment of single experiences (although

researchers do examine associations with specific items, e.g., Norman et al., 2012).

ADVERSITY QUESTIONNAIRE CORRESPONDENCE

Researchers and mental health professionals developed the CTQ to assess the same five

aforementioned types of maltreatment. It was developed with a sample of adolescent psychiatric

inpatients (Bernstein et al., 1997) and refined into a brief version (Bernstein et al., 2003). Its

psychometric properties have been examined in clinical and community samples worldwide

(Klinitzke et al., 2012; Grassi-Oliveira et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2011; Gerdner & Allgunlander,

2009). Compared to the ACE questionnaire, the CTQ is longer, more detailed, and expressly

assesses the frequency of occurrence; due to this greater detail, research ethics committees may

less commonly approve its use, especially for studies with sensitive populations.

This brief methodological report aimed to evaluate the correspondence of the ACE

questionnaire and CTQ in a sample of middle-class young adults living in the United States.

Across five types of maltreatment, we used a variety of approaches to transform richer, multi-

item Likert-scale CTQ data into binary scores. We then calculated metrics comparing these

scores to binary ACE questionnaire responses, including accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and

area under the curve in receiver operating characteristic (ROC) plots. Methods

Participants and Procedures

We fit models within a discovery (aka training) sample using exploratory procedures to

identify optimal parameters. Our discovery sample of 471 subjects (273 female) ages 20-27 years

(M=23, SD=1.7) was obtained with permission from the authors of a prior instrument validation

study (Teicher & Parigger, 2015). Participants were recruited from the community via

advertisement and were medically healthy, right-handed, unmedicated, with no history of

significant head trauma. After an initial phone screening, participants completed surveys online

ADVERSITY QUESTIONNAIRE CORRESPONDENCE

via a HIPAA-compliant system, which included the ACE questionnaire. Based on these scores,

invitations to the full session ensured equal representation of those exposed to zero, one, two,

three, and four or more types of maltreatment. In the full session, participants completed surveys,

clinical assessments, and underwent neuroimaging. For full details on procedures used with

participants in the discovery sample, see Teicher and Parriger (2015).

We also used a validation (aka test or hold-out) sample to inform study generalizability.

The validation sample of 64 subjects (43 female) was from a study that recruited medically

healthy 18–19-year-old participants (M=19.1, SD=0.5; one enrolled at age 19 but completed the

study at age 20) with scores of either 0 or greater than 2 on a different adversity questionnaire

(Maltreatment and Abuse Chronology of Exposure; Teicher & Parriger, 2015). Participants in the

validation sample were enrolled, interviewed, and assessed similarly.

All participants provided written informed consent before participation. Studies were

approved by the [removed for blind review], with continuing review through [removed for blind

review], which subsumed the [removed for blind review]. See Table 1 for a summary of

sociodemographic variables and adversity prevalence across samples. Measures

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE)

The ACE questionnaire included ten binary (yes/no) self-report items, each regarding a

type of adverse childhood experience (Felitti et al., 1998). The five items pertinent to this report

assessed emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, as well as emotional and physical neglect.

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ)

This measure assessed the same five types of maltreatment with five items each; for each

item, individuals responded using a five-point scale regarding the frequency of exposure (from

ADVERSITY QUESTIONNAIRE CORRESPONDENCE

“Never True” to “Very Often True”; Bernstein et al., 1997). Three items addressed minimization

or denial. See Supplementary Table 1 for a comparison of the CTQ and ACE questionnaire. Data Analysis Missing Data

On the ACE questionnaire, 13 participants were missing data (number of missing items:

emotional abuse=2, physical abuse=7, sexual abuse=2, emotional neglect=1, physical neglect=1).

As the ACE items were modeled as outcome variables, data were excluded for analyses within

maltreatment type. On the CTQ, 13 participants were missing data, each on a single item

(emotional abuse=1, physical abuse=2, sexual abuse=2, emotional neglect=4, physical neglect=4;

minimization=0). Values were mean-imputed within maltreatment type.

Transforming CTQ values

Continuous CTQ responses were transformed into binary scores (referred to as “predicted

ACE scores”) and compared to binary ACE responses for each maltreatment type. As there is no

existing standard transformation, we explored several transformations.

Item-based Thresholds. On the ACE questionnaire, participants were instructed to

endorse an item if any of a list of experiences occurred to them at a specified frequency before

18 years of age. On the CTQ, participants indicated the frequency of exposure to experiences in

separate items. Here we conceptualized the CTQ as breaking apart a single compound ACE item

into components (although their wording differs, see Supplementary Table 1). If a participant

endorsed one or more relevant CTQ items at a frequency at or higher than the frequency

specified on the ACE questionnaire (“ever” for sexual abuse, interpreted as a frequency response

of “rarely” on the CTQ; “often” for all other types of maltreatment) their predicted ACE score

was “yes.” Otherwise, it was “no.”

ADVERSITY QUESTIONNAIRE CORRESPONDENCE

Subscale-Based Thresholds. This approach applied thresholds to summed CTQ items.

We examined algorithmically-generated thresholds (using OptimalCutpoints v 1.1-4 in R ), first

identifying thresholds that maximized sensitivity and specificity via Youden’s index (Youden,

1950; emotional abuse=9, physical abuse=7, sexual abuse=6, emotional neglect=12, physical

neglect=8). As is typical for low-prevalence outcomes, this resulted in a high false positive rate

(Bernstein et al., 1997). In a second approach, we identified thresholds using a fixed costs ratio

of 0.5 (McNeil et al., 1975; Smits, 2010; emotional abuse=11, physical abuse=8, sexual abuse=7,

emotional neglect=14, physical neglect=14), such that false positives and false negatives were

considered equally “costly”. The number of misclassified individuals was reduced overall.

Machine learning. A support vector machine is a common supervised machine-learning

approach to binary classification (Cortes & Vapnik, 1995). This method identified a hyperplane

in a multi-dimensional space of relevant CTQ responses that best separated yes/no respondents

to each ACE item. This effectively transformed the CTQ in a manner that differentially weighed

the contributions of various items; this may be important due to imperfect semantic mappings

between questionnaires. We implemented linear SVM (using v 6.0-84 in caret R). We selected

values of , a cost/penalty parameter, that returned the greatest accuracy in the discovery sampl C e

(out of .75, .9, 1, 1.1, and 1.25; emotional abuse=1.1, physical abuse=1.1, sexual abuse=.9,

emotional neglect=1.25, physical neglect=1). While larger values of increase accuracy, they C

may overfit the data; we therefore reassess correspondence in a separate validation sample.

Correspondence Metrics

For all approaches, we calculated metrics commonly used to assess the effectiveness of

medical diagnostic tests, including accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity. Sensitivity reflects the

true positive rate—i.e., the proportion of participants with correctly predicted ACE endorsements

ADVERSITY QUESTIONNAIRE CORRESPONDENCE

out of all actual endorsements. Specificity reflects the true negative rate—i.e., the proportion of

participants with correctly predicted ACE non-endorsements out of the actual non-endorsements.

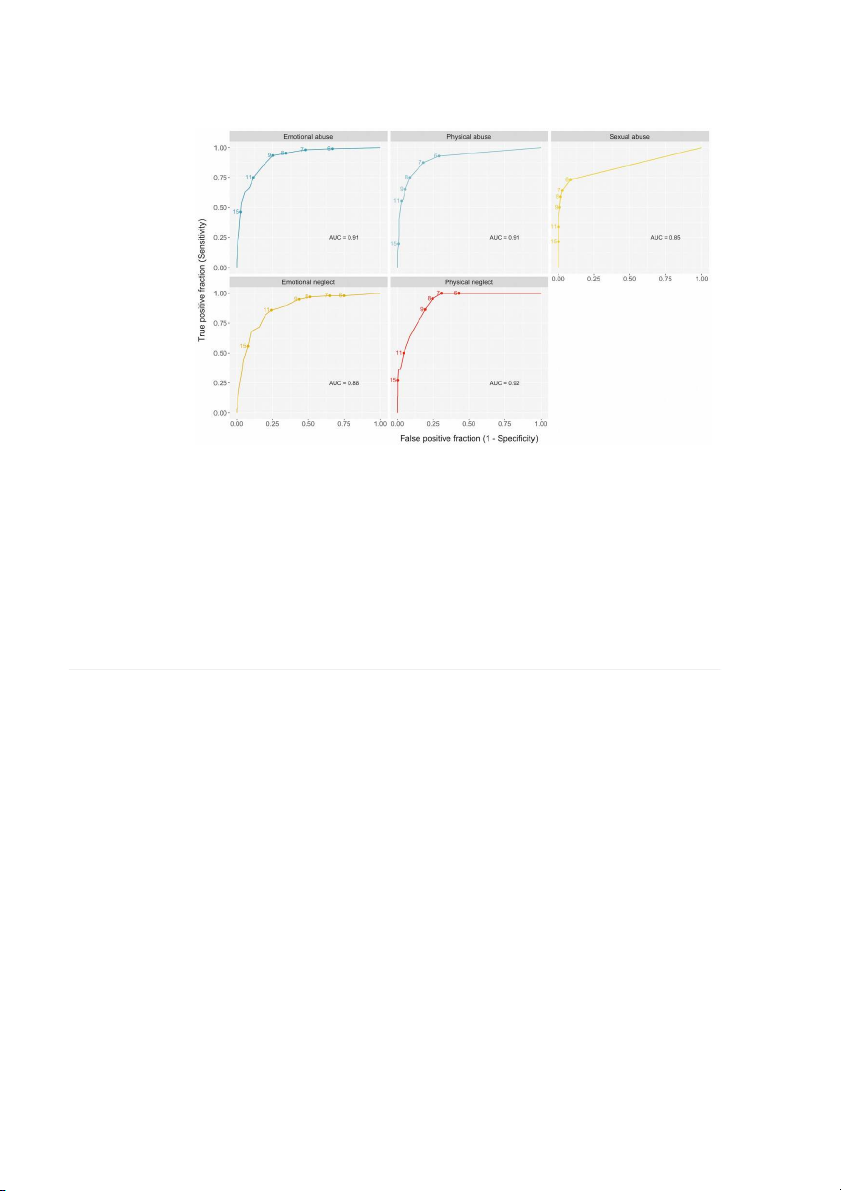

We plotted the true positive versus false positive rates for all possible subscale-based

thresholds and for each maltreatment type. From these ROC plots, we calculated the area under the curve (using v 2.2.1 in plotROC

R), which estimates the ability to detect concurrent ACE

endorsement from summed CTQ scores. See Supplementary Table 2 for the number of true/false

positives and negatives, as well as positive and negative predictive values. Results and Discussion

This brief methodological report aimed to evaluate the correspondence between the ACE

questionnaire and the CTQ. Across five types of maltreatment, we used diverse approaches to

transform continuous CTQ responses to binary predicted ACE endorsements. We then evaluated

the correspondence of these transformations to actual endorsements on the ACE questionnaire.

CTQ to ACE Questionnaire Correspondence

Across thresholding approaches, averaged accuracy ranged from 81.5-90.6%, averaged

sensitivity ranged from 52.3-86.3%, and averaged specificity ranged from 80.6-96.6% (discovery

sample; Figure 1A; physical neglect was excluded as discussed below). In ROC plots, the area

under the curve ranged from 0.85-0.92 across maltreatment types (Figure 2). Physical neglect

exhibited some of the worst and most variable correspondence metrics (Figure 1B; discovery

sample accuracy=76.2-96.4%, sensitivity=31.8-95.5%, specificity=75.2-99.6%). This might be

partly explained by a unique feature of the physical neglect ACE item; for physical neglect only,

the list of experiences comprising the ACE item is joined by “and” instead of “or,” implying that

endorsement should only follow if all experiences occurred. Perhaps relatedly, only 22

ADVERSITY QUESTIONNAIRE CORRESPONDENCE

participants endorsed this item. This may also reflect the moderately high socioeconomic status

of the sample (suggested by parental education; Table 1). Together, results suggest moderate to

strong correspondence across questionnaires for four of five maltreatment types in this sample.

Evaluating Thresholding Approaches

Item-based thresholding performed relatively poorly across correspondence metrics

(Figure 1A), which might be attributed to differences in the wording of the two questionnaires or

other measurement errors. The remaining thresholding approaches resulted in different

tendencies with respect to typical trade-offs between sensitivity and specificity (Figure 1).

Subscale-based thresholds determined by Youden’s Index generally had relatively higher

sensitivity and lower specificity but the lowest accuracies (due to lower base rates of adversity).

Support vector machine analyses generally resulted in the highest accuracy and specificity, but at

some cost to sensitivity. In comparison to this approach, subscale-based thresholds set by the

fixed cost-benefit ratio tended to have slightly decreased accuracy and specificity (<1% and

3.4% differences, respectively, across maltreatment types excluding physical neglect), but higher

sensitivity values (11.4% difference across maltreatment types excluding physical neglect) in the

discovery sample. Due to the greater difficulty of implementing machine learning, this subscale-

based approach might be most appropriate when seeking to reduce the number of

misclassifications while maintaining adequate sensitivity and specificity.

Due to space constraints, results for many thresholding approaches are not shown. We

created an interactive Shiny App for interested readers to explore results at multiple thresholds

(https://theresacheng.shinyapps.io/ctq_to_aces_shiny; see Supplementary Figure 1 for a preview

of the app; code available at https://github.com/theresacheng/ctq_to_aces_shiny).

Evaluating Generalization to a Validation Sample

ADVERSITY QUESTIONNAIRE CORRESPONDENCE

All approaches except item-based thresholding involved threshold selection or parameter-

tuning using algorithms (conducted in the discovery sample only). Therefore, it was essential to

evaluate performance in a separate validation sample. Results suggest comparable accuracy

levels and a tendency to identify improved sensitivity and worse specificity in the validation

sample. Overall, no evidence suggests significant overfitting (Figure 1). Limitations

Our young adult samples over-represent White and middle-class participants (suggested

by high parental education levels; Table 1), limiting generalizability. Retrospective self-reports

of maltreatment were not corroborated (e.g., by therapist ratings), and analyses cannot speak to

associations with other measures of childhood adversity. Summary

This brief methodological report assists researchers in understanding the comparability of

maltreatment measures on two common childhood adversity self-report questionnaires. Overall,

we found somewhat good correspondence between the CTQ and ACE questionnaires for four of

five types of maltreatment. Correspondent metrics were worse overall for physical neglect and

highly variable across thresholding approaches. In considering the goals of (a) reducing the

overall number of misclassifications, (b) maintaining both sensitivity and specificity, and (c) ease

of use, results suggest that subscale-based thresholds selected via a fixed cost-benefit ratio may

be the most ideal, on balance. Results speak to the potential to pool participants for secondary

analyses; making full use of available data is of interest because it can be resource-intensive to

recruit high adversity samples and to manage legal and ethical responsibilities that arise when

asking adults or minors about significant past or ongoing adversities.

ADVERSITY QUESTIONNAIRE CORRESPONDENCE References

Bernstein, D. P., Ahluvalia, T., Pogge, D., & Handelsman, L. (1997). Validity of the Childhood

Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. Journal of the American

Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(3), 340–348.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012

Bernstein, David P, Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., Stokes,

J., Handelsman, L., Medrano, M., Desmond, D., & Zule, W. (2003). Development and

validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child

Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

Cortes, C., & Vapnik, V. (1995). Support-vector networks. Machine Learning, (3), 273–297. 20

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00994018

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss,

M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction

to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. ,

American Journal of Preventive Medicine 14(4), 245–258.

Gilbert, L. K., Breiding, M. J., Merrick, M. T., Thompson, W. W., Ford, D. C., Dhingra, S. S., &

Parks, S. E. (2015). Childhood Adversity and Adult Chronic Disease. American Journal

of Preventive Medicine, 48(3), 345–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.09.006

McNeil, B. J., Keller, E., & Adelstein, S. J. (1975). Primer on certain elements of medical decision making. ,

The New England Journal of Medicine (5), 211–215. 293

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM197507312930501

Smits, N. (2010). A note on Youden’s J and its cost ratio. BMC Medical Research Methodology,

10, 89. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-10-89

Teicher, M. H., & Parigger, A. (2015). The “Maltreatment and Abuse Chronology of Exposure”

(MACE) scale for the retrospective assessment of abuse and neglect during development.

PloS One, 10(2), e0117423. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117423

ADVERSITY QUESTIONNAIRE CORRESPONDENCE Table 1

Sociodemographic comparison of training and validation samples Measures Training sample Validation sample Gender 273 female; 198 male 43 female; 21 male Age (years ± SD) 22.8 ± 1.7 19.1 ± 0.5 Race American Indian 8 (1.7%) 0 (0%) Asian 65 (13.8%) 9 (14.1%) Black 43 (9.1%) 7 (10.9%) Other/Multiracial 27 (5.7%) 5 (7.8%) White 326 (69.2%) 43 (67.2%) Unknown 2 (0.4%) 0 (0%) Ethnicity Hispanic 49 (10.4%) 7 (10.8%) Not Hispanic 420 (89.2%) 58 (89.2%) Unknown 2 (0.4%) 0 (0%)

Parental education (years ± SD) 15.8 ± 3.1 15.3 ± 3.1

Endorsed maltreatment on the ACE questionnaire Emotional abuse 108 (22.9%) 31 (48.4%) Physical abuse 72 (15.3%) 19 (29.7%) Sexual abuse 56 (11.9%) 11 (17.2%) Emotional neglect 99 (21.0%) 24 (37.5%) Physical neglect 22 (4.7%) 11 (17.2%)

ADVERSITY QUESTIONNAIRE CORRESPONDENCE

Figure 1. Correspondence metrics by thresholding procedure for discovery and validation

samples. Panel (A) shows accuracy, sensitivity, specificity and specificity collapsed across

maltreatment types, while panel (B) separates out this information for each maltreatment type.

Figure 2. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) plots for each maltreatment type in the discovery dataset. Examination of area

under the curve (AUC) estimates the ability to detect ACE endorsement from summed scores of relevant CTQ items. At the extremes,

a line at a 45-degree angle (AUC=0.5) indicates that signal cannot be distinguished from noise (no correspondence), while a curve that

hugs the upper left-hand corner of the plot (AUC = 1) indicates perfect correspondence. Supplementary Materials Supplementary Table 1

Language discrepancies between the ACE questionnaire and CTQ Adversity ACE questionnaire item CTQ item themesa Discrepanciesb Emotional

“Did a parent or other adult in the household

Being called names, insulted, or

- The CTQ items do not address the Abuse

often…Swear at you, insult you, put you

feeling hated or unwanted by family

second clause of the ACE question

down, or humiliate you? -or- Act in a way that

members; self-identification as a

indicating fear of physical harm.

made you afraid that you might be physically victim of emotional abuse hurt?" Physical

“Did a parent or other adult in the household

Being physically hit or punished to a

- The CTQ specifies that physical harm Abuse

often…Push, grab, slap, or throw something at

noticeable degree, with certain

includes the use of marks or hard objects,

you? -or- Ever hit you so hard that you had objects, or requiring medical

suggesting a somewhat higher level of marks or were injured?”

attention; self-identification as a physical intensity. victim of physical abuse Sexual

“Did an adult or person at least 5 years older

Having had someone else try to

- The ACE item specifies that the person Abuse

than you ever…Touch or fondle you or have

engage in sexual activities with them; is an adult or 5+ years older

you touch their body in a sexual way? -or- Try

experiencing physical or emotional

- The CTQ includes sexual coercion and

to or actually have oral, anal, or vaginal sex

threats as a means of sexual coercion;

sexual acts that occur without physical with you?”

self-identification as a victim of contact. molestation and sexual abuse. Emotional

“Did you often feel that… No one in your

Not feeling important, special, loved,

- Each item of the CTQ phrased similarly, Neglect

family loved you or thought you were

cared for, supported, and lacking but is reverse scored.

important or special? -or- Your family didn’t

high-quality relationships with family

look out for each other, feel close to each members.

other, or support each other?” Physical

“Did you often feel that… You didn’t have

Lacking in basic necessities (e.g.,

- Two CTQ items are reverse scored. Neglect

enough to eat, had to wear dirty clothes, and

food, clothing, access to medical

- The ACE items are joined by “and”;

had no one to protect you? -or- Your parents

care); not having an available

participants might only endorse if all

were too drunk or high to take care of you or

caretaker; parental substance abuse three are true.

take you to the doctor if you needed it?”

issues that interfere with child care

a wording of CTQ items is not printed due to copyright issues b CTQ also directly addresses belief about the occurrence of each type of abuse. Supplementary Table 2

Comparison of thresholding methods in the discovery sample Number of subjects Metrics (in %) Thresholds True + True - False + False - Sensitivity Specificity + Predictive - Predictive Value Value Item-based EA 4 (Often True) 74 324 37 34 68.5 89.8 66.7 90.5 PA 4 (Often True) 35 366 26 37 48.6 93.4 57.4 90.8 SA 2 (Rarely True) 41 378 35 15 73.2 91.5 54.0 96.2 EN 4 (Often True) 68 292 79 31 68.7 78.7 46.3 90.4 PN 4 (Often True) 13 384 64 9 59.1 85.7 16.9 97.7 Subscale-based: Youden Index EA 9 (Low/Mod) 100 264 89 7 93.5 74.8 52.9 97.4 PA 7 (None/Min) 63 313 70 9 87.5 81.7 47.4 97.2 SA 6 (Low/Mod) 41 369 35 15 73.2 91.3 53.9 96.1 EN 12 (Low/Mod) 81 291 72 17 82.7 80.2 52.9 94.5 PN 8 (Low/Mod) 21 333 106 1 95.5 75.9 16.5 99.7 Subscale-based: Cost-Benefit EA 11 (Low/Mod) 81 319 42 27 75.0 88.4 65.9 92.2 PA 8 (Low/Mod) 54 358 34 18 75.0 91.3 61.4 95.2 SA 7 (Low/Mod) 36 401 12 20 64.3 97.1 75.0 95.3 EN 14 (Low/Mod) 67 334 37 32 67.7 90.0 64.4 91.3 PN 14 (Sev/Ext) 8 445 3 14 36.4 99.3 72.7 97.0

Subscale-based: CTQ Low to Moderate Severity Cutoff EA 9 (Low/Mod) 101 270 91 7 93.5 74.8 52.6 97.5 PA 8 (Low/Mod) 54 358 34 18 75.0 91.3 61.4 95.2 SA 6 (Low/Mod) 41 378 35 15 73.2 91.5 54.0 96.2 EN 10 (Low/Mod) 88 249 122 11 82.7 80.2 52.9 94.5 PN 8 (Low/Mod) 21 338 110 1 95.5 75.5 16.0 99.7

Support Vector Machine Learning EA C = 1.1 69 338 23 39 63.9 93.6 75 89.7 PA = 1.1 C 39 382 10 33 54.2 97.4 79.6 92 SA = .9 C 33 406 7 23 58.9 98.3 82.5 94.6 EN C = 1.25 52 349 22 47 52.5 94.1 70.3 88.1 PN = 1 C 7 446 2 15 31.8 99.6 77.8 96.7

Note: Maltreatment type abbreviations are emotional abuse (EA), physical abuse (PA), sexual abuse (SA), emotional neglect (EN),

and physical neglect (PN). Item-based thresholds are described in terms of frequency, while all other thresholds are contextualized by

severity categories as described in the manual for the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Bernstein & Fink, 1997), as follows: none or

minimal (None/Min), low to moderate (Low/Mod), moderate to severe (Mod/Sev), and severe to extreme (Sev/Ext). Positive is

abbreviated as (+) and negative is abbreviated as (-) for both true/false positives and negatives, as well as positive and negative

predictive values. We caution against interpreting positive and negative predictive values, as they would be strongly contingent on

prevalence and rates of adversity were intentionally sampled in both the discovery and validation samples. For the support vector

machine learning approach, the cost/penalty parameter is abbreviated

In addition to the thresholding approaches described in the C.

manuscript, we additionally examined the threshold between none or minimal and low to moderate exposure as defined by Bernstein

and Fink (1997), as this theoretically demarcates participants who have/have not experienced childhood maltreatment.