Preview text:

CRITICAL THINKING

Course code: PE008IU (3 credits) Instructor: TRAN THANH TU Email: tttu@hcmiu.edu.vn 1 Analyzing Arguments

To analyze an argument means to break it up

into various parts to see clearly what conclusion is

being defended and on what grounds.

1. Diagramming Short Arguments

2. Summarizing Longer Arguments 1. Diagramming Short Arguments

Diagramming is a quick and easy way to analyze

relatively short arguments (roughly a paragraph in length or shorter). Six (6) basic steps:

1. Read through the argument carefully, circling any

premise and conclusion indicators you see.

2. Number the statements consecutively as they

appear in the argument (Don’t number any

sentences that are not statements.)

3. Arrange the numbers spatially on a page with the

premises placed above the conclusion(s) they are alleged to support. 1. Diagramming Short Arguments

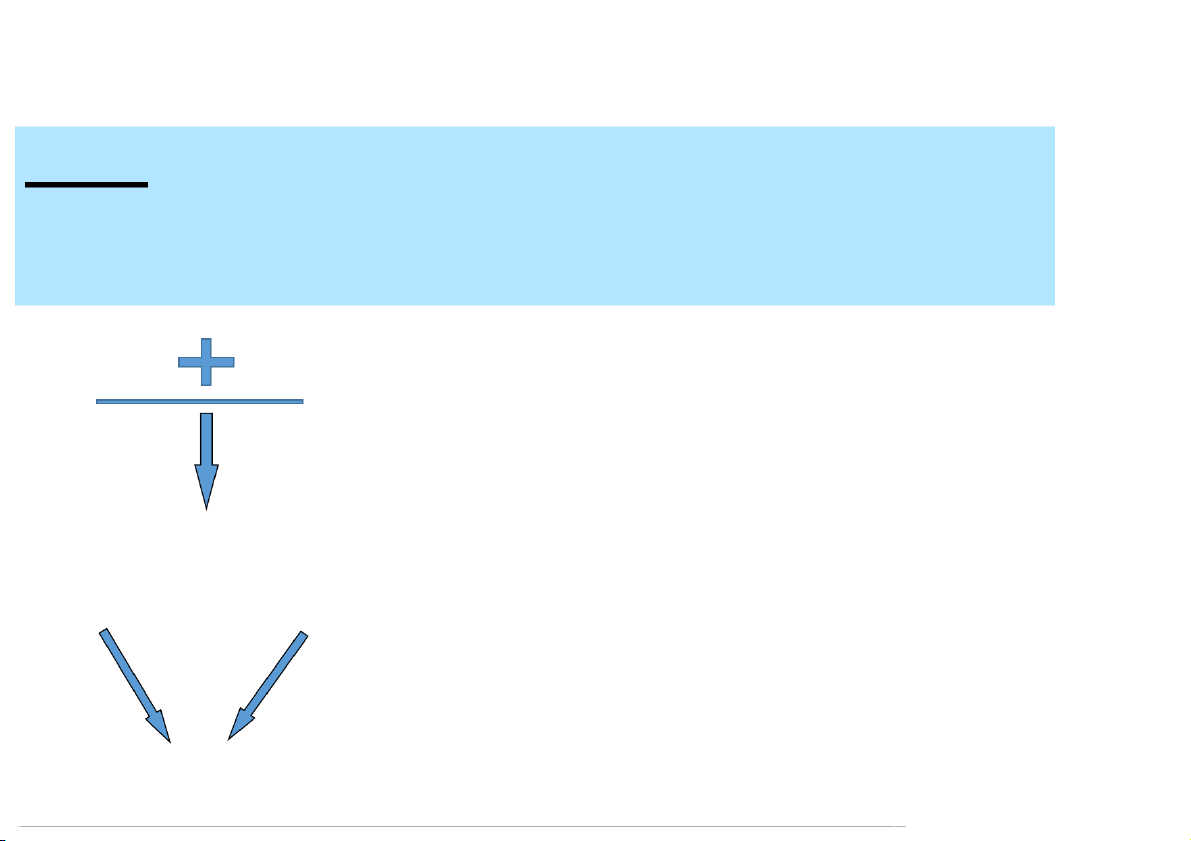

4. Using arrows to mean “is evidence for”, create

a kind of flowchart that shows which premises

are intended to support which conclusions.

5. Indicate independent premises by drawing

arrows directly from the premises to the

conclusions they are claimed to support.

Indicate linked premises by placing a plus sign

between each of the linked premises, underlining

the premises to the conclusions they are claimed to support

6. Put the argument’s main conclusion at the bottom of the diagram. 1. Diagramming Short Arguments TIPS

1. Find the main conclusion first.

2. Pay close attention to premise and conclusion indicators.

3. Remember that sentences containing the word and

often contain two or more separate statements.

4. Treat conditional statements (if-then statements)

and disjunctive statements (either-or statements) as single statements.

5. Don’t number or diagram any sentence that is not a statement.

6. Don’t diagram irrelevant statements.

7. Don’t diagram redundant statements. 1. Diagramming Short Arguments

Premise indicators: since, because, for,

given that, seeing that, considering that,

inasmuch as, as, in view of the fact that, as

indicated by, judging from, on account of, etc.

Conclusion indicators: therefore, thus,

hence, consequently, so, accordingly, it

follows that, for this reason, that is why, which

shows that, wherefore, this implies that, as a

result, this suggests that, this being so, we may infer that, etc. 1. Diagramming Short Arguments

Identify each claim and note any indicator

words that might help identify premise(s) and conclusion(s).

Number each statement and note each indicator word. Example

Since Mary visited a realtor and her bank’s

mortgage department, she must be planning on buying a house. 1. Diagramming Short Arguments

Since (1) Mary visited a realtor and (2) her

bank’s mortgage department, (3) she must be planning on buying a house.

Which of the claims is the conclusion? Which are premises? (1) (2) (3) Premise. Premise. Conclusion. Note the indicator word, “Since.” 1. Diagramming Short Arguments

Since (1) Mary visited a realtor and (2) her bank’s

mortgage department, (3) she must be planning on buying a house.

Use arrows to represent the intended (1) (2)

relationship between the claims. In this case the premises are (3) independent. Even though the (1) (2)

combined force of both premises makes the argument stronger,

either premise could stand alone (3) in supporting the conclusion. 1. Diagramming Short Arguments

Sandra can’t register for her classes on

Wednesday. After all, Sandra is a sophomore

and sophomore registration begins on Thursday.

Identify each claim and note any indicator words that

might help identify premise(s) and conclusion(s).

Number each statement and note each indicator word.

(1) Sandra can’t register for her classes on

Wednesday. After all, (2) Sandra is a

sophomore and (3) sophomore registration begins on Thursday. 1. Diagramming Short Arguments “After all” is generally a premise indicator.

(1) Sandra can’t register for her classes

on Wednesday. After all, (2) Sandra is a sophomore and (3) sophomore

registration begins on Thursday. This “and” serves to join two different claims. 1. Diagramming Short Arguments

Use arrows to show the relationships

between the claims in the argument. Decide whether or linked. the premises are independent, (2) (+) (3) (2) (3) (1) (1) These are linked premises

since both (in conjunction) are

necessary to prove the conclusion. 1. Diagramming Short Arguments

(1) Jim is a senior citizen. So, (2) Jim

probably doesn’t like hip-hop music.

So, (3) Jim probably won’t be going

to the Ashanti concert this weekend. • (1) • (2) • (3) 1. Diagramming Short Arguments

(1) Most Democrats are liberals, and (2) Senator X is

a Democrat. Thus (3) Senator X is probably is liberal.

Therefore, (4) Senator X probably supports

affirmative action in high education, because (5)

most liberals support affirmative action in higher education. (1) + (2) (3) + (5) (4) 1. Diagramming Short Arguments

(1) Cheating is wrong for several reasons. First, (2) it

will ultimately lower your self-respect because (3)

you can never be proud of anything you got by

cheating. Second, (4) cheating is a lie because (5) it

deceives other people into think that you know than

you do. Third, (6) cheating violates the teacher’s

trust that you will do your own work. Fourth, (7)

cheating is unfair to all the people who aren’t

cheating. Finally, (8) if you cheat in school now, you’ll

find it easier to cheat in other situations later in life –

perhaps even in your closer personal relationships. 1. Diagramming Short Arguments (3) (5) (2) (4) (6) (7) (8) (1) Diagraming

• Creation has no place in a science class because it is not

science. Why not? Because creationism cannot offer a

scientific hypothesis that is capable of being shown wrong.

Creationism cannot describe a single possible experiment

that could elucidate the mechanics of creation.

Creationism cannot point to a single prediction that has

turned out to be right, and supports the creationist case.

Creationism cannot offer a single instance of research that

has followed the normal course of scientific inquiry,

namely, independent testing and verification by skeptical researchers. Diagraming

•Nonhuman animals lack linguistic

capacity, and, for this reason, lack a

mental or psychological life. Thus, animals

are not sentient. If so, of course, they

cannot be caused pain, appearances to

the contrary. Hence, there can be no duty not to cause them pain. Diagraming

•No belief is justified if it can be fully

explained as the result of natural causes.

If materialism is true, then all beliefs can

be explained as the result of irrational

causes. Therefore if materialism is true,

then no belief is justified. If no belief is

justified, then the belief “materialism is

true” is not justified. Therefore

materialism should be rejected.

2. Summarizing Longer Arguments

•The goal of summarizing longer arguments is

to provide a brief synopsis of the argument

that accurately and clearly restates the

main points in the summarizer’s own words.

Summarizing involves two skills: 2.1 Paraphrasing

2.2 Finding missing premises and conclusions 2.1 Paraphrasing

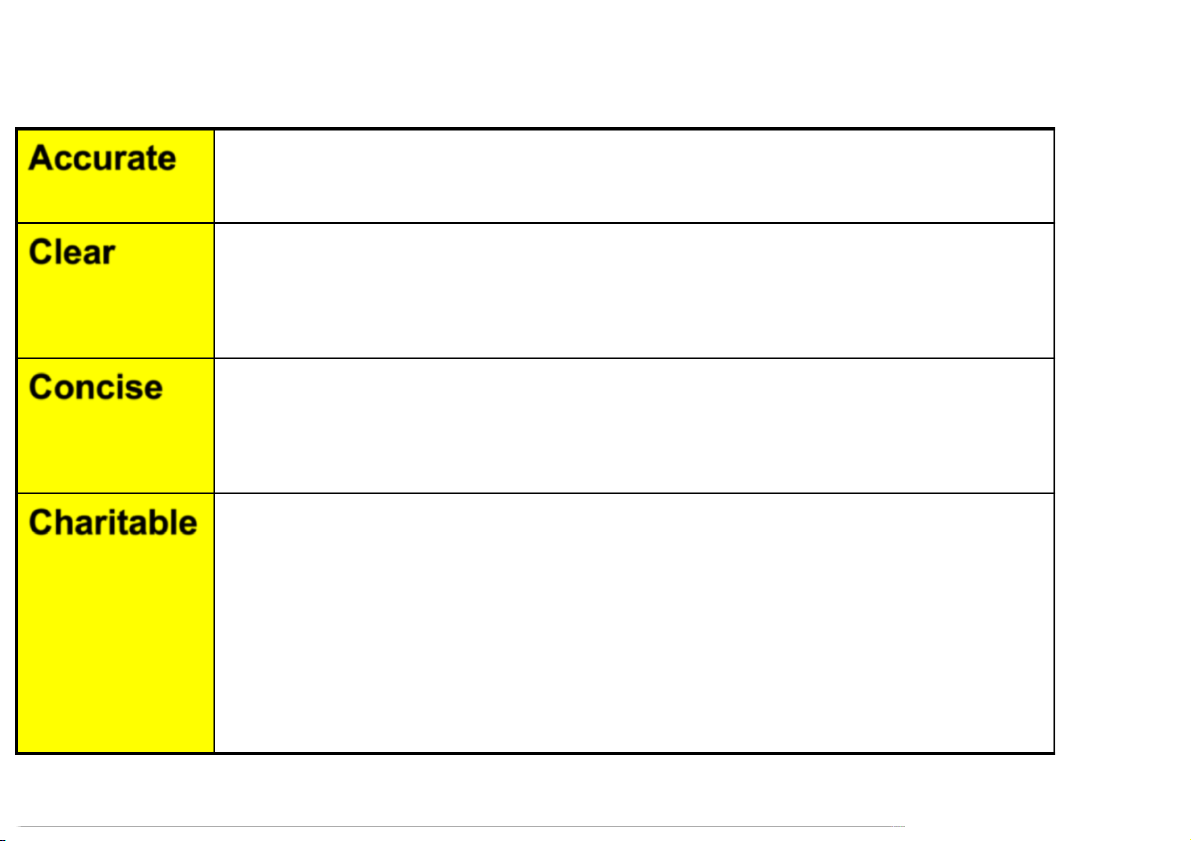

A paraphrase is a detailed restatement of

a passage using different words and phrases. A good paraphrase is Accurate

It reproduces the author’s meaning fairly and without bias and distortion. Clear

Clarifies what an argument is saying. It often

translates complex and confusing language into

language that’s easier to understand. Concise

It captures the essence of an argument, and strips

away all the irrelevant or unimportant details and

puts the key points of the argument in a nutshell.

Charitable It is often possible to interpret a passage in more

than one way. In such cases, the principle of charity

requires that we interpret the passage as

charitable as the evidence reasonably permits

(e.g. clarifying the arguer’s intent in ways that make

the arguments stronger and less easy to attack).

2.1 Paraphrasing – Accurate

don’t misrepresent (like straw man) • Original Passage:

Europe has a set of primary interests, which to us have none, or

a very remote relation to ours. (George Washington, “Farewell Address,” 1796) • Paraphrase:

(1) Europe’s vital interests are totally different than ours.

(2) Europe has a set of vital interests that are of little or no concern to us. Comment:

(1) changes the original meaning (2) is an accurate paraphrase

2.1 Paraphrasing – Clear •Original:

The patient exhibited symptoms of an edema

in the occipital-parietal region and an abrasion on the left patella. •Paraphrase:

The patient had a bump on the back of his

head and a scrape on his left knee.

2.1 Paraphrasing – Concise •Original:

The shop wasn’t open at that point of time,

owing to the fact that there was no electrical

power in the building. (23 words) •Paraphrase:

The shop was closed then because there was

no electricity in the building. (13 words)

2.1 Paraphrasing – Charitable •Original:

Cigarette smoking causes lung cancer.

Therefore, if you continue to smoke, you are endangering your health. •Paraphrase:

Cigarette smoking is a positive causal factor

that greatly increases the risk of getting lung

cancer. Therefore, if you continue to smoke,

you are endangering your health.

2.2 Finding Missing Premises and Conclusions

• “The bigger the burger, the better the burger.

Burgers are bigger at Burger King (BK).”

(Implied conclusion: Burgers are better at BK.)

• In real life people often leave parts of their argument

unstated for different reasons (being obvious and

familiar, concealing something, etc.)

2.2 Finding Missing Premises and Conclusions

•An argument with a missing premise or

conclusion is called an Enthymeme. Two (2) basic rules:

•Faithfully interpret the arguer’s intentions. •Be charitable.

Be generous in interpreting other people’s

incompletely stated arguments as you would

like them to be in interpreting your own.

2.2 Finding Missing Premises and Conclusions Two (2) basic rules:

•Faithfully interpret the arguer’s intentions.

Ask: What else the arguer must assume – that

he does not say – to reach his conclusion.

All assumptions you add to the argument must

be consistent with everything the arguer says.

2.2 Finding Missing Premises and Conclusions Two (2) basic rules: •Be charitable.

Search for a way of completing the argument that:

(1) is a plausible way of interpreting the

arguer’s uncertain intent and

(2) makes the argument as good an argument as it can be.

Summarizing extended argument - Standardizing

To analyze longer arguments, we can use a method called Standardizing.

Standardizing consists of restating an argument

in standard logical form when each step in the

argument is numbered consecutively, premises

are stated above the conclusions they are claimed

to support, and justifications are provided for

each conclusion in the argument. Standardizing

Standardizing involves five (5) basic steps:

1. Read through the argument carefully. Identify the main

conclusion (it may be only implied) and any major premises

and sub-conclusions. Paraphrase as needed to clarify meaning.

2. Omit any unnecessary or irrelevant materials.

3. Number the steps in the argument and list them in correct

logical order (i.e., with the premises placed above the

conclusions they are intended to support).

4. Fill in any key missing premises and conclusions (if any).

5. Add justifications for each conclusion in the argument. In

other words, for each conclusion or sub-conclusion, indicate

in parentheses from which previous lines in the argument

the conclusion or sub-conclusion is claimed to directly follow. Standardizing - Example

We can see something only after it has

happened. Future events, however, have not

yet happened. So, seeing a future event

seems to imply both that it has and has not

happened, and that’s logically impossible. What is missing??? The argument is lacking a main conclusion. Standardizing - Example

We can see something only after it has happened.

Future events, however, have not yet happened.

So, seeing a future event seems to imply both that it

has and has not happened, and that’s logically impossible. Standardizing:

1. We can see something only after it has happened.

2. Future events have not yet happened.

3. So, seeing a future event seems to imply both that it

has and has not happened (from 1-2)

4. It is logically impossible for an event both to have

happened and not to have happened. From 3-4 à

5. [Therefore, it is logically impossible to see a future event.] Standardizing: Common Mistakes to Avoid

Common Mistakes to watch out for (or avoid):

1. Don’t write in incomplete sentences.

2. Don’t include more than one statement per line.

3. Don’t include anything that is not a statement.

4. Don’t include anything that is not a premise or a conclusion. Standardizing: Common Mistakes to Avoid

1. Don’t write in incomplete sentences. ØError:

1. Because animals can experience pain and suffering.

2. Therefore, it’s wrong to kill or mistreat animals. Ø Correct:

1. Animals can experience pain and suffering.

2. Therefore, it’s wrong to kill or mistreat animals. Standardizing: Common Mistakes to Avoid

2. Don’t include more than one statement per line. ØError:

The president should resign since he no longer

enjoys the confidence of the Board of Trustees. ØCorrect:

1. The president no longer enjoys the confidence of the Board of Trustees.

2. Therefore, the president should resign. Standardizing: Common Mistakes to Avoid

3. Don’t include anything that is not a statement. ØError:

1.Democrats and Republicans are all the same.

2.Therefore, why should I care about politics? ØCorrect:

1.Democrats and Republicans are all the same.

2.Therefore, I have no reason to care about politics.

Standardizing: Common Mistakes to Avoid

4. Don’t include anything that is not a premise or a conclusion. •Error:

1.Many people argue that capital punishment is morally wrong.

2.But the Good Book says, “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.”

3.What the Good Book says is true.

4.Therefore, capital punishment is not morally wrong. (from 2,3)

(1) might be more motivation for giving the

argument, but it doesn’t support the conclusion,

so leave it out of the standardized argument. Summary: Analyzing Arguments

To analyze an argument means to break it up into

various parts to see clearly what conclusion is being defended and on what grounds.

Diagramming is a quick and easy way to analyze

relatively short arguments (roughly a paragraph in length or shorter).

Standardizing is a method used to analyze longer

arguments, which involves paraphrasing and finding

missing premises and conclusions.