Preview text:

logistics Article

Use of Smart Glasses for Boosting Warehouse Efficiency:

Implications for Change Management

Markus Epe 1 , Muhammad Azmat 2,3,* , Dewan Md Zahurul Islam 4 and Rameez Khalid 5 1

Business School, University of Plymouth, Cookworthy Building, Plymouth PL4 8AA, UK; markusepe@outlook.de 2

Department of Engineering Systems and Supply Chain Management, Aston University, Birmingham B4 7ET, UK 3

Cluster of Supply Chain Management, Karachi School of Business and Leadership (KSBL), Karachi 74800, Pakistan 4

Newcastle Business School, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 8ST, UK; dewan.islam@northumbria.ac.uk 5

Management Department, School of Business Studies, Institute of Business Administration (IBA),

University Road, Karachi 75270, Pakistan; rameezkhalid@iba.edu.pk *

Correspondence: m.azmat@aston.ac.uk

Abstract: Background: Warehousing operations, crucial to logistics and supply chain management,

often seek innovative technologies to boost efficiency and reduce costs. For instance, AR devices

have shown the potential to significantly reduce operational costs by up to 20% in similar industries.

Therefore, this paper delves into the pivotal role of smart glasses in revolutionising warehouse

effectiveness and efficiency, recognising their transformative potential. However, challenges such

as employee resistance and health concerns highlight the need for a balanced trade-off between

operational effectiveness and human acceptance. Methods: This study uses scenario and regression

analyses to examine data from a German logistics service provider (LSP). Additionally, structured

interviews with employees from various LSPs provide valuable insights into human acceptance.

Results: The findings reveal that smart glasses convert dead time into value-added time, significantly

enhancing the efficiency of order picking processes. Despite the economic benefits, including higher

Citation: Epe, M.; Azmat, M.; Islam,

profits and competitive advantages, the lack of employee acceptance due to health concerns still needs

D.M.Z.; Khalid, R. Use of Smart

to be addressed. Conclusions: After weighing the financial advantages against health impairments, the Glasses for Boosting Warehouse

study recommends implementing smart glass technology in picking processes, given the current state

Efficiency: Implications for Change

of technical development. This study’s practical implications include guiding LSPs in technology

Management. Logistics 2024, 8, 106.

adoption strategies, while theoretically, it adds to the body of knowledge on the human-technology https://doi.org/10.3390/ interface in logistics. logistics8040106

Academic Editors: Mladen Krsti´c,

Keywords: order picking; smart glasses; smart warehouse; digitalisation; warehouse operations;

Željko Stevi´c and Snežana Tadi´c

logistics performance; warehouse performance; smart logistics; innovation Received: 23 July 2024 Revised: 15 September 2024 Accepted: 30 September 2024 1. Introduction Published: 17 October 2024

In today’s global supply chains, the demand for speed and agility in logistical processes

is imperative, particularly within warehouse operations, where efficiency is a crucial

determinant of success [1]. Order picking is a part of the warehousing logistical processes

Copyright: © 2024 by the authors.

in a company that has a vital impact on performance in terms of efficiency, quality, cost,

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland.

and time [2]. Order picking as an essential part of the material flow is a value-intensive

This article is an open access article

activity with great potential for optimisation [3]. Recognising this potential for optimisation,

distributed under the terms and

pursuing efficiency in this process becomes crucial to reduce operational costs and enhance

conditions of the Creative Commons

picking speed [4]. To do so, new methods, products, and services are required to meet the

Attribution (CC BY) license (https://

demands of highly dynamic logistics markets and the increasing complexity of logistics

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/

networks. Flexibility, adaptability, and proactivity are becoming increasingly important 4.0/).

Logistics 2024, 8, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics8040106

https://www.mdpi.com/journal/logistics Logistics 2024, 8, 106 2 of 25

and can be achieved by incorporating new technologies [5]. While problem-orientated

approaches lead to incremental improvements, technology-orientated approaches can bring

more significant changes [6]. Employees still manually carry out many logistics processes

according to the receipt-based pick-by-paper or the receipt-less variant pick-by-scan [7].

Securing competitive advantages by improving order picking performance is crucial

for a warehouse operation’s competitive positioning. Innovative technologies such as

augmented reality (AR) are proving particularly promising for logistics in warehousing.

AR can reduce warehouse operations costs while significantly increasing efficiency and productivity [8].

Employees must perform information-intensive activities within order picking while

keeping their hands free to carry out picking activities. In the form of smart glasses, AR

can display context-sensitive information in the user’s field of vision and guide them

through work steps [9]. Smart glasses thus extend current picking scenarios through so-

called pick-by-vision systems [10]. As a result, the employees engaged in transport and

logistics operations, equipped with smart glasses, are provided with real-time operational

information, such as delivery orders and picking status, without interrupting the actual

work process to improve performance [9,11]. The glasses offer a novel aspect of current

picking situations, providing employees with instant operational information without

unduly interrupting their work process.

In an experiment, DHL tested two commercial smart glasses, Google Glass and Vuzix®

M100, at a warehouse and discovered a 25% boost in efficiency [12]. Similarly, Boeing

investigated using Google Glass to help in wire bundle assembly; they observed a 30%

boost in productivity and a favourable response from employees [13]. In another case study,

a head-worn display (HWD) was implemented in two warehouses in Belgium, where one

was successful while the other was not. The prime reason was the employees’ involvement

in improving the device’s functionality and usage conditions [14]. Another study reported

four cases of implementing AR-enabled vision-picking at DHL, Samsung, Coca-Cola, and

Intel. At DHL, productivity and speed increased by 15% and 25%, respectively, while

at Samsung, productivity increased by 12–22%. Similarly, at Coca-Cola, performance

increased by 6–8%, while at Intel, speed increased by 29% [15].

Although the literature focusses on the potential of smart glasses in warehousing,

scientific case studies still need to be developed, leading to a gap in understanding their

efficiency and effectiveness [16–18]. Despite its maturity, the use of AR systems in ware-

housing, especially in the order picking process, is still an active area of research [19]. The

authors of [20] emphasised that there is a need to share selected use cases to resolve any

uncertainties in logistics regarding the use of AR-enabled smart glasses. The literature

further stressed assessing the impact of smart glasses via well-documented case studies

experimenting with various digital technologies and software and rigorous comparisons

with existing solutions [20,21]. Comfort and cleanliness in reusing these glasses across

multiple shifts require further testing, posing significant barriers to user acceptance and adoption [22].

The gap that this study plans to fill is to determine the productivity benefits of smart

glasses over traditional picking methods along with their human acceptance. To fill this

identified gap, a research question is posed: Can smart glasses be more effective, efficient, and

acceptable than conventional order picking methods for logistics processes? In answering this

question, the paper aims to investigate the effects of smart glasses in terms of effectiveness

and efficiency increase and acceptance compared to conventional picking methods in

a case study in cooperation with a German 3PL service provider, as well as to evaluate the

employee acceptance of smart glasses.

The study seeks to understand smart glasses’ potential for transformative capabilities

by applying scenario analysis, regression analyses, and structured interviews of employees.

The research question is further explained by creating the research objectives, which will

be presented in the next section. Logistics 2024, 8, 106 3 of 25 2. Literature Review

Picking is one of the core activities of a warehousing operation. As per [23], it is the

most time-consuming and error-prone activity among all the warehousing tasks. Today,

there are multiple ways in which orders are picked in warehouses, namely: pick-by-paper,

pick-by-vision, pick-by-light, pick-by-voice, pick-by-gesture, cart-mounted display, and

pick-by-scan [21]. Most warehouses still use paper-based picking approaches. However,

any paper-based approach could be faster and more accurate. In addition, picking is often

performed by temporary workers, who usually require costly training to ensure efficient

and error-free picking [23]. In this section, we will first discuss the key performance indica-

tors (KPIs) involved in assessing the performance of a picking operation in a warehouse.

Subsequently, the role of human touch and smart glasses in pick-by-vision will be discussed.

This section will conclude with a discussion of the benefits of AR-enabled picking and the

research objectives of this study. 2.1. KPIs in Picking Operation

Efficiency is the improved ratio of (minimum) input to (maximum) output. Logistics’

primary and most important purpose is to connect supply and demand in a demand-

orientated and cost-efficient way [24]. To improve competitiveness, the efficiency of logistics

facilities (quantity, speed, and quality with the same resource input) must be increased [24].

To improve performance, reducing the amount of redundant resources is necessary [25].

The key performance indicators (KPI) are throughput times, picking performance, and the

associated error rates [26,27].

Throughput Time: Picking time can be defined as the throughput time of the picking

process [28,29]. The throughput time of an order is defined as the sum of the processing,

transport, and waiting times at all production stages [30], therefore, the sum of dead

times, picking times, and travel times across all items [31,32]. An order picking system’s

KPI “picking performance” is relevant to reflect its efficiency [33]. Usually, the picking

performance refers to the number of items regardless of the removal quantity per item [29].

The performance is always related to a time unit, which is always one hour. Following

Equation (1) is formulated to calculate the order picking performance. Pos Order picking per f ormance = (1) h

Picking Performance: Other variables influencing performance are the availability and

utilisation of order pickers. There are empirical values for the availability of human order

pickers [33] based on the working conditions and the load. In performance comparisons of

picking techniques, the number of positions “Pos” is kept constant so that the picking time

is multiplied by the same factor each time. The performance is thus directly proportional

to the picking time [30]. Depending on the throughput time and the number of positions,

the order picking performance can be determined with Equation (2) below, which is

increasingly applied in further processes. Pos Number o f positions Order picking per f ormance = ∗ 60 min/h (2) h throughout time [min]

Error Rate: One of the most critical factors in picking is avoiding or reducing errors.

Pick errors can directly impact customer relationships and satisfaction, as picking errors

are often noticed after delivery. Errors, therefore, result in a negative customer experience,

which can affect the customer-supplier relationship and result in financial damage [34].

According to [23,33], one error per 1000 items (0.1%) is desirable. The goal of zero error Logistics 2024, 8, 106 4 of 25

picking is currently not achievable due to human error susceptibility in a non-autonomous

picking system. The following Equation (3) is used to calculate the error rate: Number o f errored positions Error rate [%] = ∗ 100% (3) Number o f positions

Out of the four methods (pick-by-scan, pick-by-voice, pick-by-light, and pick-by-

vision), only one picking method is below the desirable error rate of 0.1% (see Table 1),

and that is the pick-by-vision method having an average error rate of 0.08%. Although the

error rate in order picking today is meagre even with a pick-by-paper approach—experts

estimate the rate at 0.35% to 0.45%—every error must be avoided as it usually results in

high follow-up costs [35]. Table 1 establishes pick-by-vision as a candidate to be explored

further for wider application due to its potential to reduce error. In a lab test, an optimal

set of parameters were extracted for the best performance: the battery is to be positioned

on the side of the weight, the storage level of the racks should be high, discrete order mode

of picking should be used, a scanner should be used as the confirmation equipment, and

there should be a lower number of lines per order.

Table 1. Overview of Error Rates, compiled from various sources [1,29,36–39]. Method Error Rate Source Average Error Rate 0.36% (Günthner, et al., 2009) Pick-by-Scan 0.46% (ten Hompel and Schmidt, 2010) 0.39% 0.36% (Lolling, 2003) 0.25% (Reif, 2009) Pick-by-Voice 0.08% (ten Hompel and Schmidt, 2010) 0.14% 0.10% (Lolling, 2003) 0.25% (Reif, 2009) Pick-by-Light 0.08% (ten Hompel and Schmidt, 2010) 0.24% 0.40% (Lolling, 2003) 0.0075% (Guo, et al., 2014) Pick-by-Vision 0.125% (Göpfert and Kersting, 2017) 0.08% 0.12% (Günthner, et al., 2009) 2.2. Human Touch in Picking

Human flexibility in order picking is almost impossible to replace, despite many

automation concepts. Regardless of increasing requirements such as variable article ranges,

decreasing order sizes, and increased flexibility, rationalisation potentials can be tapped

if the order picker is optimally supported in their core task, considering both ergonomic

and informational aspects, and is relieved of time-consuming and distracting secondary

activities [29]. AR can improve information visualisation if employees in picking systems

are equipped with data glasses [40]. Ref. [14] identified a need to document cases where

companies have successfully maintained and extended employee interest and participation

while implementing smart glasses in picking operations.

2.3. Smart Glasses for Pick-by-Vision

‘Smart glasses’ refers to peripheral devices with integrated small computers worn

on or at the head. Things, plants, animals, people, situations, and processes are regis-

tered, analysed, and enriched with virtual information [41]. Mobile devices attached to

the user’s body are called wearables [42]. A wearer of smart glasses, or more broadly,

an augmented reality head-worn display HWD (AR HWD), can access various informa-

tional types, such as text, graphics, and video. Information can be overlayed onto the

real world (augmented vision) or perceptually placed next to real-world objects of interest

(conformal augmented reality) so that users do not have to look down to access it, unlike

when they access manuals, hand-held devices, or other reference materials [12]. Typically,

the aim is to support real-world action by offering data, assessments, and directions [43,44]. Logistics 2024, 8, 106 5 of 25

AR-enabled smart glasses can merge the actual world with virtual data in the user’s field of

vision. These AR devices must be distinguished from their virtual reality (VR) equivalents,

which have an opaque screen. They do not support the overlay of virtual and physical

reality but rather conceal the user’s perspective within the device and protect them from

any exterior visual input [45].

AR offers the possibility of actively supporting work processes in logistics, such as the

warehouse picking process, thereby increasing employee efficiency, effectiveness, and satisfac-

tion [8,46]. Various cases and experiments have been reported in the literature [12–15,22,47].

The integrated scanning technology, usually in the form of a camera on the frame of the

glasses, meets the demand for integrating digitisation measures, such as optimising ware-

house management systems [29]. Different smart glasses and scanners are reported in

the literature for pick-by-vision, to name a few: Google Glass, Vuzix® M100 and M300XL,

RealWear HMT-1, Samsung Gear S2, and Intel Recon Jet Pro.

Picking is a skill-, rule-, and information-intensive activity, so this technical support for

using AR and smart glasses in the pick-by-vision process is one of the most critical success

factors [36]. Using a tracking system to recognise the position and direction of gaze, static

data such as text information can be displayed and data that is dynamically positioned

in space [29]. These 3D spatial geometries attractively highlight the picking or storage

location or show the optimal path throughout the warehouse [29]. This always gives the

user direct access to information and eliminates the need for disruptive activities to retrieve

information that interrupts the work process. Furthermore, when using smart glasses, the

user has both hands free through voice-based control [8,23]. Increased picking performance

in the work process is expected through the expansion of the natural environment. This is

because of the process guidance along the picking process, which promises cognitive relief

for the smart glasses user [48].

2.4. Benefits of Paperless Picking

The strict visual guidance of order pickers lets them complete their daily picking tasks

in a warehouse environment faster and more error-free than they would be able to do

without the support of data glasses [49]. According to [49], smart glasses make it possible to

use an ergonomic product that can be worn by the order picker and the cognitive superiority

of humans to design logistical processes efficiently. Previous studies in paperless picking

suggest that data glasses have great potential as a user-friendly and task-supporting tool

with good information display and design quality [50]. It was also found that the error

rate is significantly lower when using pick-by-vision compared to voice-controlled picking

support. This is due to the technically determined low error tolerance of data glasses [51].

Refs. [52,53] suggest that paperless picking methods have tremendous advantages.

Pick-by-vision leads to reduced search times, clean documentation, increased performance,

and reduced errors in the picking process. The use of smart glasses offers the opportunity to

actively support work processes in logistics, such as the picking process in the warehouse,

thereby increasing efficiency, effectiveness, and employee satisfaction [8,46]. Especially in

throughput time, pick-by-vision can achieve a competitive advantage. The authors of [20]

have defined the potential of AR smart glasses in logistics and supply chain management

around four facets: visualisation, interaction, user convenience, and navigation.

A faster process goes hand in hand with higher productivity, increasing profitability.

The faster an order is picked up, the cheaper the product delivery. Other goals are route

optimisation, increased picking performance based on short throughput times, and process

reliability in the form of little to no error susceptibility. The processing of the order volume

should require as little effort as possible and must accordingly be designed as efficiently as

possible [7,52]. In this context, the employee’s movement time plays a significant role at

50%, and the search time is 20% within the picking process (Figure 1) [54]. Logistics 2024 Logistics , 20248 , , 8106 , x FOR PEER REVIEW 6 of 6 of 25 27 % of Order-Picker's Time Other Setup Pick Search Travel 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60%

Figure 1. Order picking time overview [48].

Figure 1. Order picking time overview [48]. 2.5. 2.5. Derivation

Derivation of the Resear of the Resear ch Objec ch tives Objectives Order pick Order ing take picking s sev takes eral several items fro items fr m om the w the areh war ouse to serv ehouse to e serve and and fulfi fulfill several several independent independent customer ord customer or ers ders accord accor ing to cu ding to stomer requirements. customer requirements. The aim is The aim is to to make make this this process process as as pr practical actica (e.g., l (e.g., higher higher speed of speed of p picking) ic and king ef ) and ficient effi (e.g., cient ( r e educed .g., reduced operational operat cost) ion as al cost possible. ) as pos This sib meansle. Thi that s me the ans t basic hat the operational basic costs operat shouldional c be r osts educed, should be but at the reduced, b same time, ut a the t the or sa der me time, the order picking speed pi should cki be ng spe incr ed eased sho [4]. uld be increas Minimising ed time[4]. M for inimis the ing picking time f pr o ocess r the p is icking process

necessary for any is necessary f picking o system r [ any 48, pic 55]. king system By extending [48,55]. B the y natural extending envir the onment, natur incr al envir eased onment, incr picking eased pic performance in kin the g per work formanc process e in is the wor

expected. k process is expected. Pick-by-vision can be Pick-by-v used ef ision can be ficiently, use primarily d e for fficiently, primar inexperienced ily for inexperience employees or high d employ temporary ees or high worker rates te in m a porary w company o . rker r The r ates in eason a com for this pany is, . The reason among other for t things, his i the s, among ot guidance her t along h theings, the picking gui pr dance ocess, along t which h pr e pickin omises g process cognitive ,r which promis elief for the es cognit smart ive re glasses lief fo user [48 r t ]. he sm These art glasse should s be user pr [48] ovided. Th to ese the shou e ld be mployee provided intuitively to th and e emplo er yee int gonomically uitive while ly and er aiming gonomic for an ef ally wh fective ile and aim ef ing for ficient an eff picking ectiv pr e and ocess, i effi .e., cient picking maximising process, i.e., performance maximising perf while ormanc minimising the e while potential minimising

for errors [ the potential for errors [46]. The st

46]. The strict visual guidance of or rict der visual pickers guidanc lets e them of order p complete ickers their lets daily them compl picking e tasks te thei in a r dai war ly pi ehouse cking ta envir sks i onment n a w faster areh and ouse env more err iron or-fr m ee ent faster than they and more would be error-f able to ree than they woul do without the d be a support b ofle to do data without the support of glasses [49]. data glasses [49]. The fo The llowing following re r sear esear ch obj ch ective i objective s is derived derived to m to ake the theory ta make the theory ngible a tangible nd crea and cr te a eate a possibility of verification. possibility of verification.

RO1: To assess the impact of smart glasses in increasing the effectiveness and efficiency of the

RO1: To assess the impact of smart glasses in increasing the effectiveness and efficiency of the

picking processes compared to conventional picking methods.

picking processes compared to conventional picking methods.

It emphasises exploring the improvement in logistics processes with the use of smart

It emphasises exploring the improvement in logistics processes with the use of smart

glasses and eventually offers the possibility of a competitive advantage.

glasses and eventually offers the possibility of a competitive advantage.

Humans will continue to play a crucial role in production and logistics operations due

Humans will continue to play a crucial role in production and logistics operations

to their adaptability and sensorimotor abilities in an increasingly digitalised world. Thus,

due to their adaptability and sensorimotor abilities in an increasingly digitalised world.

ergonomics, flexibility, and occupational safety should be improved [56]. The goal is to

Thus, ergonomics, flexibility, and occupational safety should be improved [56]. The goal

design logistics operations processes so people and machines can operate, interact, and

is to design logistics operations processes so people and machines can operate, interact, integrate easily [57]. and integrate easily [57].

Several strategies aim to increase user friendliness and acceptance by deliberately

Several strategies aim to increase user friendliness and acceptance by deliberately

minimising the number of necessary contacts between humans and the system. This

minimising the number of necessary contacts between humans and the system. This

allows the user to concentrate more on their task, increasing productivity and reducing

allows the user to concentrate more on their task, increasing productivity and reducing

the susceptibility to workplace errors. Intelligent devices are designed to be as invisible as

the susceptibility to workplace errors. Intelligent devices are designed to be as invisible as

possible to the user and to support him in his activity by providing him with the appropriate

possible to the user and to support him in his activity by providing him with the contextual information [57].

appropriate contextual information [57].

For pick-by-vision and the associated process optimisations to result in actual human-

For pick-by-vision and the associated process optimisations to result in actual

added value, it is crucial to consider factors influencing the acceptance and usability of the

human-added value, it is crucial to consider factors influencing the acceptance and information system [23,58,59].

usability of the information system [23,58,59].

To increase user acceptance, it is essential to consider both the physical and psycho-

To increase user acceptance, it is essential to consider both the physical and

logical strain on the employee [57]. Ergonomics and mental stress are the most crucial psycholog requir ica ements l strain for on the employ accepting smart ee [57]. devices [58].Ergonomics and Employees must ment be al stress are aware of the the most advantages

crucial requirements for accepting smart devices [58]. Employees must be aware of the Logistics 2024, 8, 106 7 of 25

of wearable technology and incorporate it into their everyday work activities. Wearables

should offer quantifiable value, for instance, regarding mobility or weight. Ideally, they

should not be noticeable to the employee in the work process but should integrate natu-

rally [60]. However, ergonomics is not limited to the wearability of smart glasses but also

to the ergonomics of the user interface. It is possible that extended use of smart glasses in

workplaces can cause visual fatigue and impair attention [61]. Although AR helps lessen

head and neck motions while operating, workers may become distracted or confused by the information [62].

In addition to ergonomics, an essential aspect of acceptance is privacy and the associ-

ated protection of that privacy [59]. The challenge is that indoor localisation and task and

error tracking are critical to the performance of such a system [63]. This exposes users to

increased surveillance by supervisors [59].

The following research objective is derived to make the theory tangible and to create

a possibility of assessing acceptability based on various criteria:

RO2: To assess the employees’ acceptance level of using smart glasses in the picking process without concerns. 3. Methodology

As mentioned in previous sections, this study has one research question and two

objectives. A mixed-method study was conducted to achieve the objectives, and the

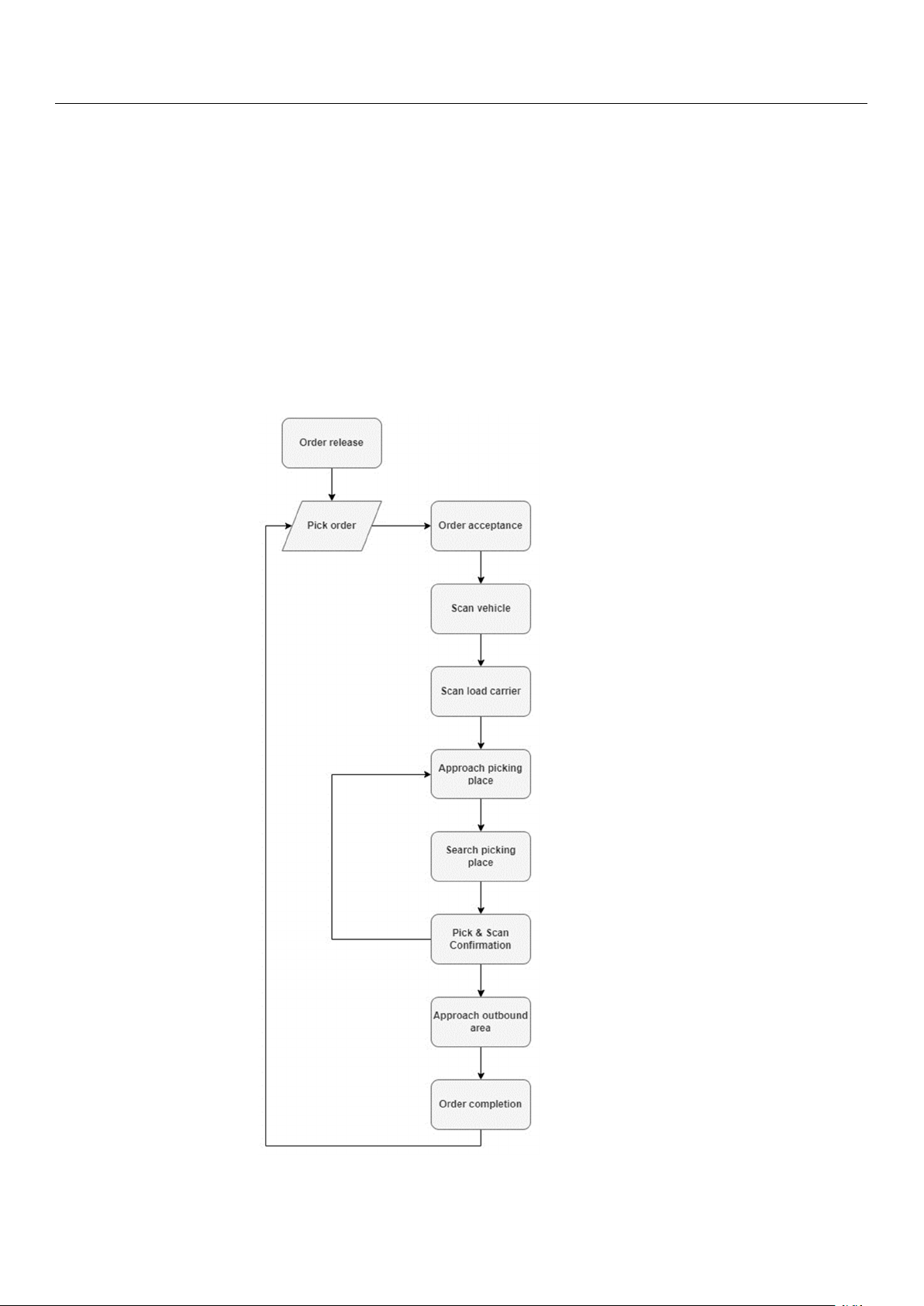

following steps were implemented. 3.1. Research Objective 1 a.

The following methods were performed to assess the increase in efficiency of smart glasses in picking operations. i.

Two test series (one was in a test environment while the other was in live

business operation) were conducted in the year 2022 in the warehousing

facilities of the case company, i.e., the German 3PL logistics service provider

(LSP). The data on the same picking process with and without using smart

glasses was collected for comparison. The process flow within the two tests

was defined in advance (Appendix A). During the data collection phase, the

employee is accompanied over one week to collect all the data. The same

selector performed the picking operation in both test series to reduce external

and human influences, such as picking and moving speeds. ii.

Based on the collected data, a regression analysis was conducted to deter-

mine the relationship strength between the dependent variable (throughput

time) and the independent variables (setup time, search time, and pick time).

Waiting time and travel time were kept constant. iii.

Ten scenarios were created using the collected data and historical data on

order picking from the case company for 2021. These scenarios were thor-

oughly evaluated to generalise the possible increase in efficiency considering

the number of picking locations and the number of picks per picking location. b.

The following method was performed to assess the increase in the effectiveness of smart glasses. i.

A cost–benefit analysis (CBA) was performed to identify the savings the pick-

by-vision approach can achieve. This analysis used the data collected in the

test series and developed scenarios. 3.2. Research Objective 2 a.

This objective was achieved using a structured interview-based survey, the details of

which are presented as follows: Logistics 2024, 8, 106 8 of 25 i.

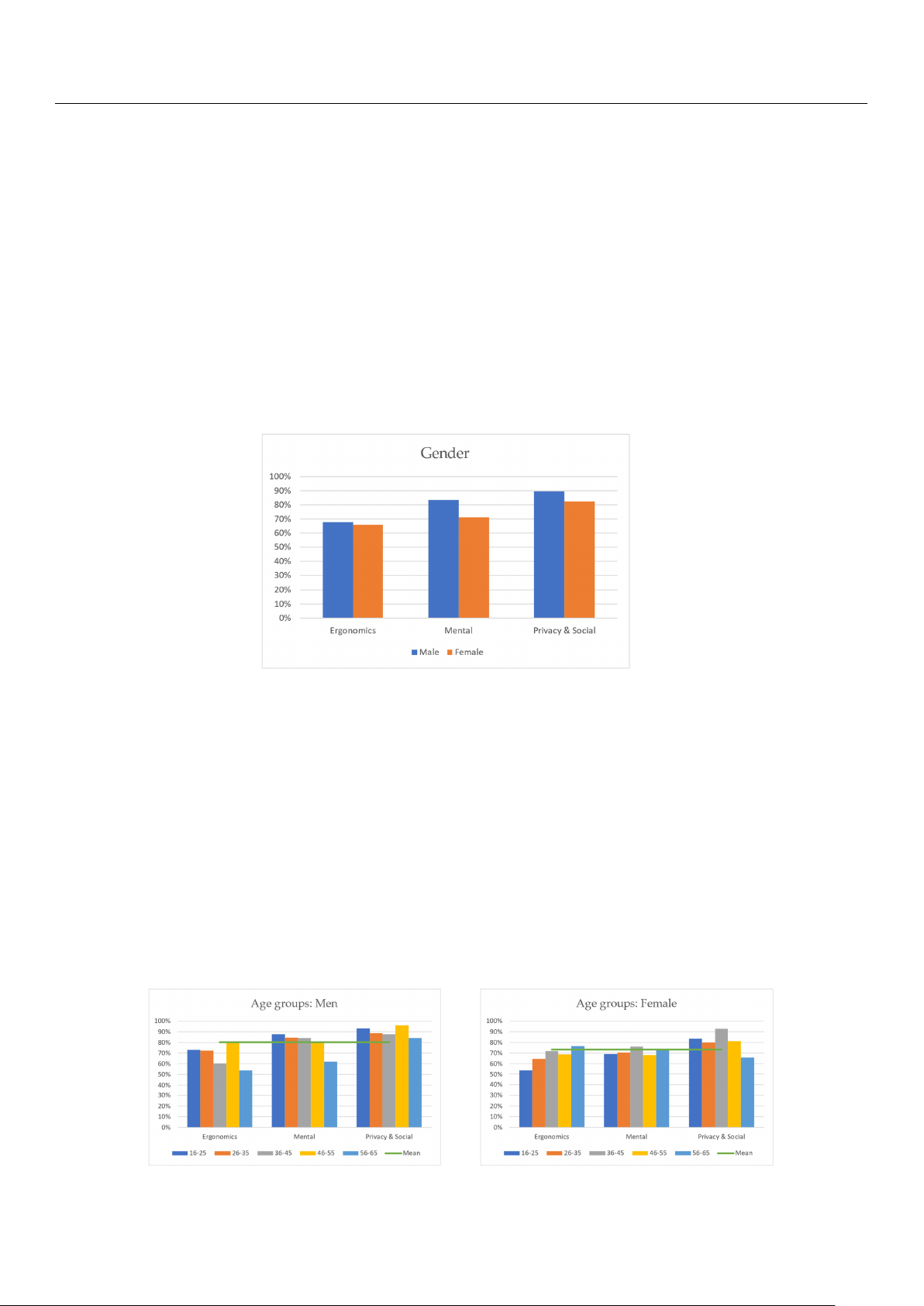

An interview guide was prepared with 13 questions (10 closed-ended state-

ments and one open-ended question). These questions were divided into

the three essential attributes around human acceptance: ‘ergonomics’ (four

statements), ‘mental’ (three statements), and ‘privacy & social’ (three state-

ments). The ten closed-ended statements followed a seven-point Likert-type

scale from ‘not true at all’ to ‘true exactly’, with a ‘neutral’ in the centre,

and were considered quantitative data [64]. The answer that reflected 100%

acceptance is assigned a seven, while all the answers are then assigned values in descending order. ii.

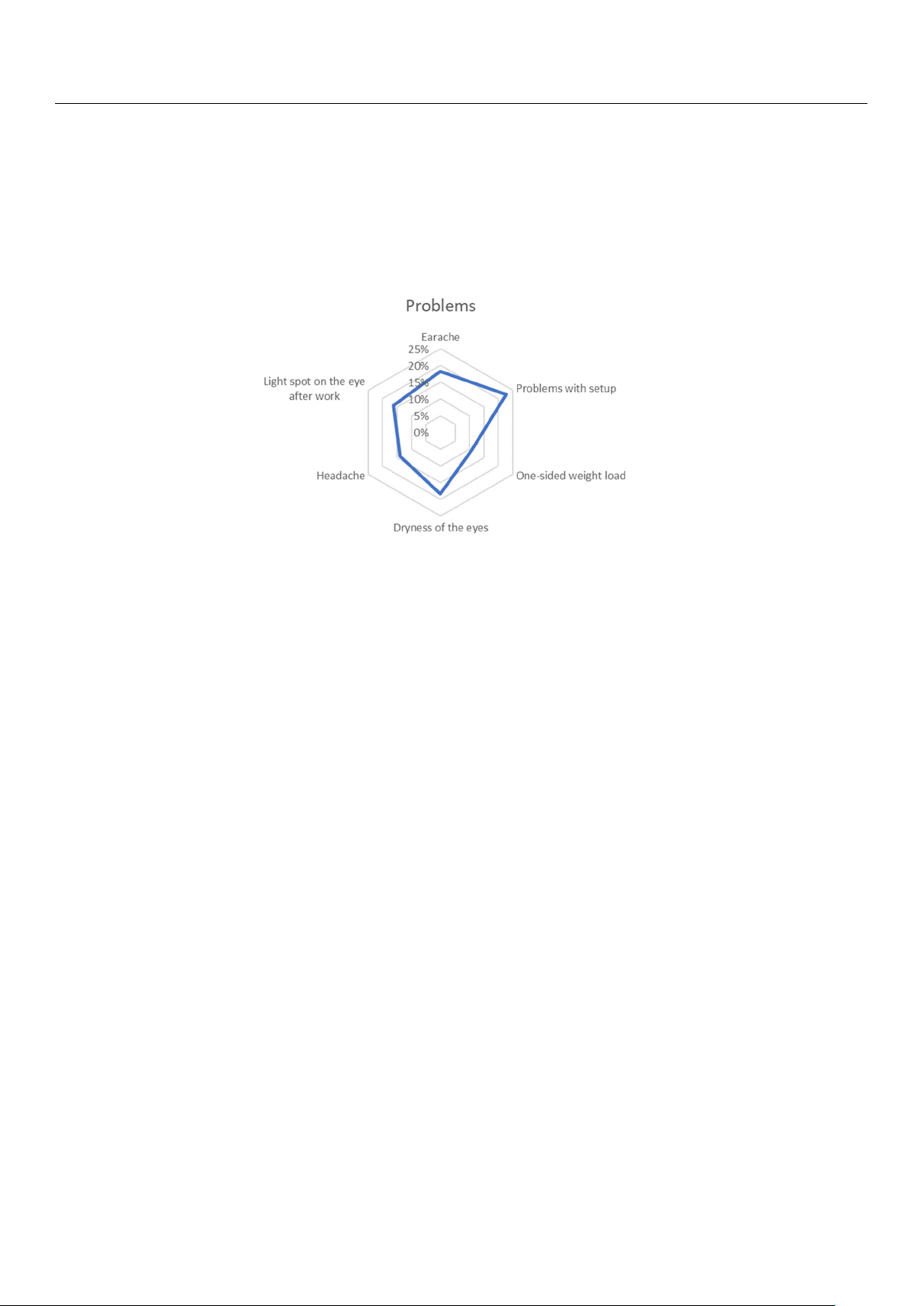

The only open-ended question was about possible concerns regarding the

technology. To analyse this question, the first-order codes were developed us-

ing direct responses, and similar responses were categorised into six concerns as the second-order code. iii.

The interview questions were tested and validated as part of a pilot test

where ten employees of the case company were interviewed, and each gave

individual feedback. The interviews took 10–15 min per interviewee. The

phrasing was improved as an outcome of the pilot. iv.

The inclusion criteria required that the respondents be those who use smart

glasses technology daily or have worked with them in the last year. v.

To assess the broader acceptance of smart glasses, 86 respondents were in-

cluded. They were employees from different companies in the LSP sector.

The sample data were divided into 37% women and 63% men. The interviews were conducted face-to-face.

The diversity of the mixed-method approach allowed for rich data collection, which

had the advantage of building a comprehensive view through enhanced triangulation.

These data collection and analysis methods were chosen to achieve the research objectives effectively and objectively.

4. Findings and Discussion

The aim is to achieve the two research objectives in two steps: RO1 is achieved using

the tests performed, regression analysis, scenario analysis, and cost–benefit analysis (CBA),

while RO2 is realised by analysing the data collected through structured interviews.

4.1. RO1: To Assess the Impact of Smart Glasses in Increasing the Effectiveness and Efficiency of

the Picking Processes Compared to Conventional Picking Methods

RO1 is achieved in two parts: (a) first, the ‘efficiency’ part by two test series, regression

analysis, and scenario analysis, and (b) second, the ‘effectiveness’ part via CBA.

4.1.1. Assessing the ‘Efficiency’ of Smart Glasses

To make a scientifically relevant statement about achieving RO1, two different series

of tests were carried out. The first series of tests are based on a test environment outside

the daily business, while the second one is conducted during the live daily business. The

average pick quantity per day based on historical data for the period January–July 2022 is

10,754 picks per day. The average order size based on the total of all orders in 2021 is five

pick positions with three picks each. According to this, a picking activity must be carried out 15 times per order.

Within the pick-by-vision method, the company does not use the option of visual

guidance in route optimisation through the warehouse but a direct location display in the

employee’s field of vision. The smart glasses provide visual information about the storage

location of the material to be picked, the order size, and the respective pick quantity of the

item. To reduce a possible source of error, the order picker confirms the location in advance.

Afterwards, the order picker is provided with the order’s picking information. The scan

confirmation is performed via a scanner integrated into the system, which maintains

Logistics 2024, 8, x FOR PEER REVIEW 9 of 27 Logistics 2024, 8, 106 9 of 25

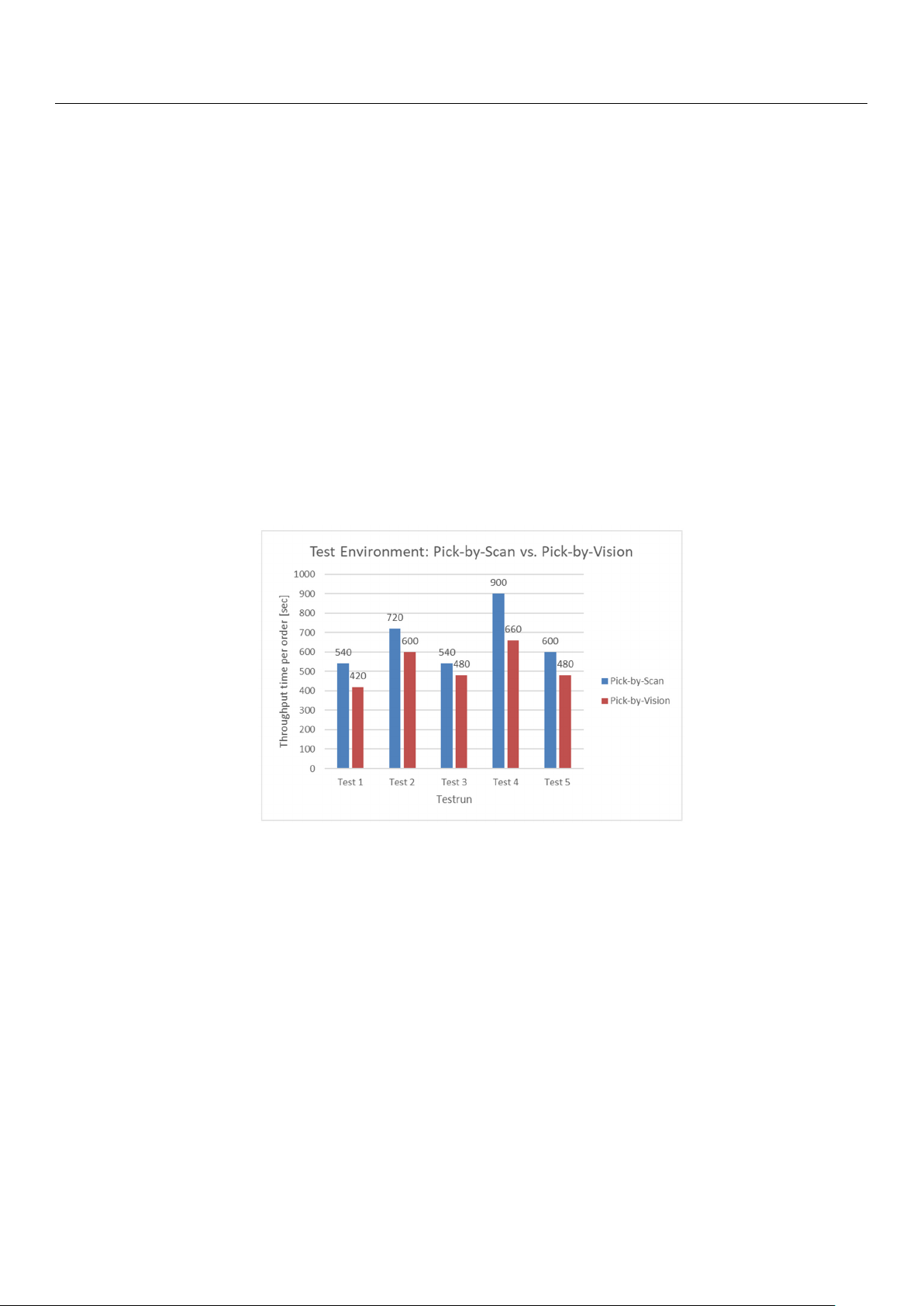

The scan confirmation is performed via a scanner integrated into the system, which the ma advantage intains th of “hands-fr e advantage ee” or of “h der ands- picking free” or compar der pic ed k to the pick-by-scan ing compar method ed to the pick with -by-scan a hand-held scanner method with a ha . nd-held scanner. T T est est series series 1—pick-by-scan 1—pick-by-sc vs. an vs. pick-by-vision pick-by-vision in in the the test environment: test environm Five ent: Five picking picking processes wer processes wee carried re carr out using ied ou the t usin conventional g the conven pick-by-scan

tional pick-b and pick-by-vision y-scan and pi methods. ck-by-vision Accordingly methods. , the Acco exact rdingl picking y, the locations exact pick wer ing e loc s a tored in tions we the order re stored for in each test the order run for and then each test picked run using and th the pick-by-scan

en picked usin and pick-by-vision g the pick-by-sc methods. an and pi The ck measur -by-visionement period for methods. The the throughput measurement time of a complete period for th order with the respective e throughput time of a

predefined pick quantity starts

complete order with the respective with the predefi order ned pi acceptance ck quantity . It sta ends rts wiwith providing th the order ac the wholly ceptan picked or ce. It ends wi der in the th providi goods ng the issue zone. wholly pi This cked trial series order in thaims to obtain

e goods issu a basic comparison e zone. This trial of seri the es aitechnologies ms to obta based on in a basic throughput comparis time. on of Due to the the technolo standar gies ba disation, it sed on thro is then ughput tpossible ime. to Due make to th a e st statement andardis about ation, it a is potential incr then possibl ease (or e to ma decr ke a ease) stat in ef ement aficiency bout a .

potential increase (or decrease) in efficiency. Figur Figu e re 2 visualises 2 visualises the th thr e th oughput roughput times time of pick-by-scan s of pick-by-sc and an an pick-by-vision d pick-by-visi for on for the the respective respective test series. test seri It can be seen that es. It can be seen th the pick-by-vision at the pick-by-visi method has on method ha a significantly s a significantly shorter throughput time

shorter throughput time in each in ea test series ch test seri compar

es compar ed to the conventional

ed to the conventional pick-by-scan pick-by-scan method. The average method. The av time erage ti per me pick, including per pick, includinsear g sech ar times, ch ti picking mes, picki times, ng ti travel mes, tratimes, vel ti etc., mes, amounts etc., am to 39.76 s with

ounts to 39.76 the conventional s with the conv pick-by-scan entional pi method. ck-by-scan The pick-by-vision method. The pi method ck-by-vision can be quant method ca ified n be her quan e ti with fied an average here with of an av31.81 s per erage of pick. On 31.81 s pe average, r pick. the On av pick-by-vision erage, the pick- method by-vis is ion 7.95 met s h faster od is per 7.95 pick s fa than ster the per conventional pick than pick-by-scan the conventionalmethod, pick-b corr y-sca esponding n method, to a 25% incr correspondi ease in ef ng to a 25 ficiency % in . crease in efficiency. Figure 2. Figure 2.Te T st estenvironm envir ent: co onment: mparison of pi comparison of ck-by-scan and pick-by-scan pick and -by-vision. pick-by-vision. The Thesystem’s performanc system’s e can performance canbe ev be aluated evaluatedbased on based onthe throughp the thr ut ti oughput mes obt times ained obtained in the test en in the test vironment an environment d the respect and the r ive espective pick quantity (F pick quantity igure (Figure 3). The 3). The average orde average or r der picking perf picking ormance wi performance thin the test en within the test vi envir ronment of the pi onment of the ck-by-sca pick-by-scan n method i method is s 95 95.42 .42 picks picks pe per hourr h perour per em employee. ploy The ee. The pick

pick-by-vision -by-vision method method achieves an achieve average s an averag performance e of performa 117.92 nce of picks 11 per 7.92 hour picks per per hour pe employee. r employ The differ ee. T ence in he d the ifference in the performance of perfor the mance o two f systems the two syst amounts toems amo 23.58%. unts t Basedo 23 on .5 a 8%. Based on population of a po 7.48pu h lati per on of shift, 7.48 h p 713.75 er sh picksift, 71 per 3.75 shift pick can s be per shift can achieved be achieved mathematically mathematic per order ally per o picker withrder the picker with the conventional conventional pick pick-by-scan -by- method. The

scan method. The pick-by-vision

pick-by-vision method achieves method a 882.04 chi picks eves per 882.0 shift. 4 picks per shift.

Test series 2—pick-by-scan vs. pick-by-vision in day-to-day operations: The study is

conducted on a sample basis and is intended to represent the population of all orders in the

case company. A sample’s reliability, size, and representativeness play a significant role in

meaningful results [65,66]. The measurement basis of the trial series is based on a total of

10 orders with a total of 105 items and 256 picks of the pick-by-scan method and 12 orders

with 108 items and 367 picks of the pick-by-vision method. One position is equivalent to one picking location. Logistics 2024 Logistics , 20248 , , 8106 , x FOR PEER REVIEW 10 of 10 of 25 27

Figure 3. Order-picking performance per employee (test environment).

Figure 3. Order-picking performance per employee (test environment). Test The ser twoies 2 test —pick series -by-s assistcan in vs. pick-b achieving y-vision RO1 by in day-to-day oper concluding that a ations: The st smart glasses-e udy is nabled conducted on pick-by-vision a samp appr le b oach asis incr and eases is inte the ef nded to repre fectiveness s and ent the population efficiency of the of all o picking r pr ders in ocesses the case compar com ed to pany. A sam conventional ple’s reli picking ability, s

methods.ize, and representativeness play a significant role in R mean egressio in n gfu Ana l re ysi su s: lt T s he [6 c 5, oll6 e6 c ]. Th ted de atmeas a are urement examine basi d for s of nor t m h a e t lit r y ia u l se singrie th s e is K b ol ased mog on orov a – tota Smi l r of 10 nov orders wi test before th a tota further l of 105 analysis. items a The testnd 256 pi assumes cks of in its the pick- null by-sca hypothesis n m that ethod a the nd tested 12 orders wi variable is th 108 i normally tems and 36 distributed. 7 picks of th

The test is e pick-by-vision me

suitable for smaller thod. One po samples (n < sition 30) [ is 67]. equiv The alent to critical one pick value for ing the location.

maximum difference for a sample size (n = 22) at a significance level The two test series of alpha 0.05 [68, assist in 69]. The achiev values ing in T RO1 able by conc 2 show lud thating that a the null smart glasse hypothesis, s-en “a abled normal pick-by-vision distribution appro exists”, ach in cannot creases the e

be rejected. ffectiveness and efficiency of the picking processes

compared to conventional picking methods.

Table Regression Analysis: 2. Kolmogor The

ov-Smirnov test. collected data are examined for normality using the

Kolmogorov–Smirnov test before further analysis. The test assumes in its null hypothesis Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test

that the tested variable is normally distributed. The test is suitable for smaller samples (n

Test Statistics (p-Value)

Critical Value (Quantile K)

< 30) [67]. The critical value for the maximum difference for a sample size (n = 22) at a Throughput Time 0.2016 0.2809

significance level of alpha 0.05 [68,69]. The values in Table 2 show that the null hypothesis, Setup Time 0.0977 0.2809

“a normal distribution exists”, cannot be rejected. Travel Time 0.1002 0.2809 Search Time 0.1743 0.2809

Table 2. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test Pick Time . 0.1664 0.2809

Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test

The next step is identifying the relationship between the dependent and independent

Test statistics (p-value)

Critical Value (Quantile K)

variables through a regression analysis [70]. The dependent variable is the throughput Throughput Time 0.2016 0.2809

time of the picking process. The independent variables directly influencing the throughput time Se ar tup Ti e me setup, travel, search, 0. and 0977 picking times. Table 3 0.2809 illustrates the results from the r Tra egr vel Ti essionme analysis. Multiple 0 R .1002 is 0.9873, indicating a robust 0.2809 linear relationship [71]

between the predictor (independent variables) and the response (dependent: throughput Search Time 0.1743 0.2809

time) variables. The quality of the relationships can be inferred from the R-square of 0.9747, Pick Time 0.1664 0.2809

meaning that the variations in the dependent variable almost wholly explain the variation

in the throughput time. According to [71], 0.05 is a reliable F-value significance level, and the r The egr next ession step is identify table confirms ing the its relation value at sh

0.025.ip between the dependent and independent variables t Regar hrough ding a the regre coef ssion ficients, ana if lys all is [7 other 0]. The pr de edictor pendent v variables a r riable emain is the throughp constant, each ut co- time of the efficient is pick viewed ing as pr the ocess. The average independent increase in the r variab esponse les dir variable ectly for infl each uen unit cing incr the ease throughput time are in a particular pr setup, edictor v travel ariable , sea [72, rch, a 73]. nd pickin Looking at g ti the mes. coef Table 3 ficients, ill it ustrates t becomes he res clear ults that from t the he reg travel ression time (1.160ana 5) lys has is. M the u gr ltiple eatest R is 0.98 positive 73, in corr dicati elation ng a rob with u the st thrlinear rela oughput tionshi time p and [71] betw influences een it the predictor (ind significantly. e However pen , dent v because ar the iables) value isand the above response 1, a certain (dependent: inaccuracy is th pr roughput esent due time) v to ariables. The multicollinearity. qua Thelity of the rel dependent ationships variables can of be travel inferred time (p f = rom the R- 0.0000206), squar sear e ch of 0. time (9 p74 = 7, meaning 0.04511), th and at the v picking ariat time ions (p = in the dependent 0.000000137) corr vari elate able with alm the ost wholly dependent explain the v variable of a thr riation in oughput the throughput time and are time. Accordi statistically ng to [ significant 71] as , 0.0 the 5 p is a reli -values a arb e le F- less value than sign 0.05 i[fic 74 a ].nce lev The el, and variable the regression “setup-time” ( table p = confi 0.8878 rm > s its v 0.05) alue seems at 0. to 025 have. no significant influ-

ence on the throughput time of the process, and this is due to its smaller percentage of time

in the overall picking process.

Logistics 2024, 8, x FOR PEER REVIEW

Logistics 2024, 8, x FOR PEER REVIEW 11 of 27 11 of 27

Logistics 2024, 8, x FOR PEER REVIEW

Logistics 2024, 8, x FOR PEER REVIEW 11 of 27 11 of 27

Logistics 2024, 8, x FOR PEER REVIEW

Logistics 2024, 8, x FOR PEER REVIEW 11 of 27 11 of 27

Logistics 2024, 8, x FOR PEER REVIEW

Logistics 2024, 8, x FOR PEER REVIEW 11 of 27 11 of 27

Table 3. Results of the regression analy sis.

Table 3. Results of the regression analysis.

Logistics 2024, 8, x FOR PEER REVIEW

Logistics 2024, 8, x FOR PEER REVIEW 11 of 27 11 of 27

Table 3. Results of the regression analy sis.

Table 3. Results of the regression analysis.

Logistics 2024, 8, x FOR PEER REVIEW

Logistics 2024, 8, x FOR PEER REVIEW 11 of 27 11 of 27 Regression

Table 3. Results of the regression analy sis. Regr ANOVA ession

Table 3. Results of the regression analysis. ANOVA Regression

Table 3. Results of the regression analysis. Regr ANOVA ession Table 3. Result Sign s of ific the regr anc essi e on analysis. ANOVA Significance Statistic Va Regression lues Item df Statis SS tic Va

Table 3. Results of the regression analysis. Regr ANOVA ession MS lues F Item df SS

Table 3. Results of the regression analysis. ANOVA MS F Sign F ificance Sign F ificance Statistic Va Regression lues Item df Statis SS tic Va

Table 3. Results of the regression analysis. Regr ANOVA ession MS lues F Item df SS

Table 3. Results of the regression analysis. ANOVA MS F Significance Significance Multi Sta pl tis e R tic 0.9872 Va 553 Regression lues 2 Regression 4 1 Sta , Multi2 Item df 9 pl tis 3 e ,37 R tic 0.64 0.9 32 SS Va 3 872 ,34 Regression lues 2.66 5532 ANOVA MS 1 63. 55553 Re 2. gressi5 F 0 × 10 F −13 on F 4 1,2 Item df 93,370.64 32 SS 3,342.66 ANOVA MS 163. 55553 2.5 F 0 × 10−13 Sign F ificance Sign F ificance R-Squa Multi Sta pl tis re 0 e R tic 0 Regr .9 .9 ession 746 872 Va 730 553 lues 6 2 R Reesidual 1 gression 7 4 R- 1 Sta 3 , Multi Item df 3 2p tis ,608 Squa 9l3 e , R tic Regr .3 37 1 re 0 0.64 0.9 .9 3 ession 1 2 SS Va 976 7463 872 , lues ANOVA .9 730 34 553 MS 6 2.66 2 1 63. 55553 Re 2. gressi5 F 0 on 6 Residual 1 × 10−13 7 4 1 3, Item df 3 2 ,608 93, .3 37 1 0.64 3 12 SS 976 3, ANOVA .9 34 MS 6 2.66 163. 55553 2.5 F 0 × 10−13 Sign F ificance Sign F ificance Adjus R- Sta t Multi ed Squa pl tis R- re 0 e R tic 0.9 .9746 872 Va 730 553 lues 6 2 R Reesidual 1 gression 7 4 Adjus R- 1 Sta t, Multi ed 3 Item df 3 Squa 29 pl tis R- ,608 3 e , R tic .3 37 1 re 0 0.64 0.9 .9 3 12 SS Va 976 7463 872 , lues.9 730 34 553 MS 6 2.66 2 1 63. 55553 Re 2. gressi5 F 0 on 6 Residual 1 × 10−13 7 4 1 3, Item df 3 2 ,608 93, .3 37 1 0.64 3 12 SS 976 3, .9 34 MS 6 2.66 163. 55553 2.5 F 0 × 10−13 Sign F ificance Sign F ificance R-Squa Multi Sta pl tis e R tic 0 re 0.9 . 687 746 872 Va 137 730 553 lues 8 6 2 R Re Tota esi l 21 dual 1 gression 7 4 R- 1, 1 Sta , Multi32 3 Item df 3 29 pl tis 6, Squa3 e 9 , tic 7 ,608 37 R 8. .3 96 0 re 0 0.64 .9 . 687 746 32 872 SS Va 137 1 1976 730 3,34 553 lues 8 .9 MS 6 2.66 2 1 63. 6 55 R Re Tota esi 553 l 2 21 . gressi5 F 0 on dual 1 × 10−13 7 4 1, 1,32 3 Item df 3 296, 3 9 , 7 ,608 378. .3 96 0.64 32 SS 3,342.66 MS 163. 55553 2.5 F 0 × 10−13 Square Adjusted R- Square Adjusted R- 1 1976.96 F F R-Squa Multiple R 0 re 0.9 . 687 746 872137 730 5538 6 2 R Re Tota esi l 21 dual 1 gression 7 4 R- 1, 1, Multi32 33 29 pl 6, Squa3 e 9 , 7 ,608 37 R 8. .3 96 0 re 0 0.64 .9 . 687 746 32 872137 1 1976 730 3,34 5538 .96 2.66 2 163. 6 55 R Re Tota esi 553 l 2 21 . gressi50 on dual 1 × 10−13 7 4 1, 1,32 33 296, 3 9 , 7 ,608 378. .3 96 1 0.64 3 12976 3, .9 34 6 2.66 163. 55553 2.50 × 10−13 Standa Sq rd Err uare Adjusted Multiple o R- R r Adjusted R- R-Squa 0 re 0.9 . 687 746 872137 730 5538 6 2 R Re Tota esi l 21 gression 4 Standa Sq rd Err uare dual 17 R- 1, 1, Multi32 33 29 pl 6, Squa3 e 9 , o 7 37 R r ,608 8. .3 96 0 re 0 0.64 .9 . 687 746 32 872137 1 1976 730 3,34 5538 .96 2.66 2 163. 6 55 R Re Tota esi 553 l 2 21 . gressi50 on dual 1 × 10−13 7 4 1, 1,32 33 296, 3 9 , 7 ,608 378. .3 96 0.64 323,342.66 163. 55553 2.50 × 10−13 Square Adjusted R- 44.681535 Square Adjusted R- 44.681535 1 1 976.96 R- (SE Standa ) rd Error Squa 0 re 0.9 . 687 746137 7308 6 R Tota esi l 21 dual 17 R- (SE Standa 1, 3 ) rd Err 32 3 6, Squa 9o 7r ,608 8. .3 96 0 re 0.9 . 687 746137 1 1976 7308 .96 6 R Tota esi l 21 dual 17 1, 32 33 6,97 ,608 8. .3 96 Square Adjusted R- 44.681535 1 1976.96 Square Adjusted R- 44.681535 Observation (SE Standa ) rd Err Adjusted s o R- 22 r 0.96871378 Total 21 (SE Standa 1, ) 326, rd Err 9o 7r 8.960.9687 1378 Total 21 1,326,978.96 Square 44.681535 Observation Adjusted s R- 22 Square 44.681535 Logistics 2024 Standa , 8, 106 (SE) rd Error 0.96871378 Total 21 (SE Standa 1, ) 326, rd Err 9o 7r 8.960.9687 1378 Total 11 of 25 Observations 22 21 1,326,978.96 Square 44.681535 Observations 22 Square 44.681535 Lower Lower Ite Standa m (SE) Co Observation rd Err sor efficients 22 SE t-Sta

t p-value Lower Ite Standa m (SE) rd Error 44.681535 Observation95% Co s Upper effici 95% ents 22 SE Upper 95.0% t-Sta t

p-value Lower 95% Upper 95% Upper 95.0% 44.681535 (SE Standa ) rd Error (SE Standa ) rd Error 95.0 % Lower 95.0 % Lower Item Co Observations efficients

22 SE t-Stat p-value Lower Item 44.681535 Observation95% Co s Upper effici 95% ents 22 SE Upper 95.0%

t-Stat p-value Lower 95% Upper 95% Upper 95.0% 44.681535 Intercept 4 Lower Lower Item (SE) 4 Co .384566 Observations effici 2 ents 132.17 7 0. 22 SE 3357 t-S 97 tat 0.7 p411 3271 Int− e234 Item (SE) .4840 -value Lower 95 3 rcept 4 4 Co 2 Observation95% 3 .384 s effic .i25 566 323 Upper ents − 2 132. 234 17 95 95% .4 .0 841 3 7 0 %. 22 SE 3357 t-Sta 2 t 3.25 322 97 0.7 p 7 411 Upper 95.0% 3271 −234.4840 -value Lower 95 3 2 95% 3.25 323 Upper −234 95 95% .4 .0 841 3 % 23.25 3227

Table 3. Results of the regression analysis. Upper 95.0% Lower Lower Setup Time Inte Item Observation s − rcept 40.642 4 Co .384231 566 effici 6 4 ents . 22 4830 2 132.17 6 −0.143 7 0. SE 3 t-S 257 357 tat 4 0.8 97 0.7 p877 411 712 3276 Int−e10 1 − Ite .10 234 m .4066 Setup Time -value Lower Observation 840 s 24 8 − 95 3 rcept 44 Co . 95% 8 0.642 2 .384161 231 3 effic .i25 566 991 6 4 Upper ents . 22 4 − 323 − 2 132. 10 830 17 95% .10 6 234 95 .4 .0 066 8 −0.143 841 3 7 0 %. SE 3357 t-Sta .t8 2 161 2573.25 991 4 0.8 322 97 0.7 p 4 877 411 Upper 95.0% 712 7 3276 −10 1 − .10 234.4066 840 -value Lower 24 8 95 3 . 95% 8 2 161 3.25 991 Upper − 323 −10 95% .10 234 95 .4 .0 066 8 841 3 % .8 2 161 3.25 991 3224 7 Upper 95.0% 95.0% Lower 95.0% Lower Tra Intercept 4 Item 4 Co .384566 effici 2 ents 132.17 7 0. SE 3357 t-S 97 tat 0.7 p4113271 Int− e234 Item .4840 -value Lower 95 3 rcept 4 4 Co 2 95% 3 .384 effic .i25 566323 Upper ents − 2 132. 234 17 95% .4841 3 7 0. SE 3357 t-Sta 2 t 3.25322 97 0.7 p 7 411 Upper 95.0% 3271 −234.4840 -value Lower 95 3 2 95% 3.25323 Upper −234 95% .4841 323.253227 Upper 95.0% Regression vel Time Setup Time 1−.1605 0.642016 2315 0 6 4.1 .4994 8309 6 5 − .8173 0.143 349 257 2 4 0 ..0 8 6 × 10 877 − 7125 0 Trav 6 − .7 el Ti 10 ANOV 396 me .10066 Setup Time A 14 1−.1 1 24 8.5 605 .8 0.642818 016 161 231391 5 0 6 4.1 991 .4 0 − .7 994 10 830 396 9 .10 6 14 5 − .8 Lower 173 0.143 1 066 8..5 8 257 818 349 161 391 2 4 0 ..0 8 6 991 × 10 4 877 − 7125 0 6 − .7 10 396 .10 14 066 1 24 8.5 .8818 161391 991 0 − .7 10396 .10 14 Lower 1 066 8..5 8 818 161 391 9914 Intercept 4 Item 4 Co .384566 effici 2 ents 132.17 7 0. SE 3357 t-S 97 tat 0.7 p4113271 Int− e234 Item .4840 -value Lower 95 3 rcept 4 4 Co 2 95% 3 .384 effic .i25 566323 Upper ents − 2 132. 234 17 95 95% .4 .0 841 3 7 0 %. SE 3357 t-Sta 2 t 3.25322 97 0.7 p 7 411 Upper 95.0% 3271 −234.4840 -value Lower 95 3 2 95% 3.25323 Upper −234 95 95% .4 .0 841 3 % 23.253227 Upper 95.0% Statistic Search Ti Travel Ti Setup Time V me me alues 0. 1− 5 . 368 1 0.642488 6052317 0165 0 6 4.06..4959 18309 9949 Item 6 05−.7.8713 173 0.143 474 349 257 df 42 4 0 ..5.081 × 10 6 8777126 −10.10066 Setup Time 24 8 − .8 0.642161 231991 6 4.4 −10 830 .10 6 066 8 −0.143 .8161 257 991 4 0.8 4

8777126 −10.1006624 8.8161991 −10.10066 8.81619914 − × 10 2 − 5 Tra SS − v 0.931 Search Ti 0.7 el Ti 558 me 396 me MS 42 2 0. 1 5 14 .1 1.0 368 .5 605052 4887 818 0165 0. 0 6 .1F 562 −0.931 959 391 0. 9 7 9949 95.0 0 3965.. Significance 558 2 %78 713 173 . 14 0 1. 052 474 5 349 4 8182..F 561 505 1 × 10 391 6 − × 10 2 − 5 −0.931 0.7 558 396 42 2 14 1.0 .5052 818562 −0.931 391 0.7 95.0 558 2 396% . 14 0 1. 052 5 561 818 5 391 Trav Int el Ti e me Setup Time 1− rcept 4.14605 0.642 .384016 231 5665 0 6 4.1 .4994 830 2 132.179 6 5−.8173 0.143 7 0.3 349 257 357 2 4 0 .. 97 0. 0876877 411712 3276 Int−e10 1 − .10 234.4066 Setup Time 84024 8 − 95 3 rcept 44 .8 0.642 2 .384161 231 3.25 566991 6 4.4 − 323 − 2 132. 10 830 17 .10 6 234.4066 8 −0.143 841 3 7 0.3357 .8 2 161 2573.25991 4 0.8 322 97 0.7 4 877 411712 7 3276 −10 1 − .10 234.4066 84024 8 95 3.8 2 161 3.25991 − 323 −10.10 234.4066 8 841 3.8 2 161 3.25991 3224 7 − × 10 2 −5 0 Trav .7 el Ti39614 me 1.1 1.5 605818 016391 5 0.1 0.7 994 396 9 14 5.8173 1.5818 349 391 2.06 − × 10 2 −5 0.739614 1.5818391 0.739614 1.5818391 Multiple Pi Inte R ck Ti Search Ti 0.98725532 me me 1 0 rcept 4..0 5 4 777 368 .384119 488 5663 7 00..16 2 132. Regr 068 959 179 9 ession 1 00..082 7713 7 0.3 293 474 357 41 4. 97 0. 3 .5 7 71 411 1,293,370.64 × 10− × 10 8 327 0 Pi − Inte .8 1 − 521 ck Time 0.931 Search Time 234.4 323,342.66 904 558 840 8 1 0 rcept 4..0 5 4 1 42 2 95 3.3 777 .0 368 2 .384032 119 488 3. 5663 0527 25 163.55553 334 0 0..16 0 562 − 323 − 2 132. .8521 068 959 179 0.931 9 234.41 00.7 7 0.3 2.50 905 1 .082 558 2 713 841 3 357 × .3 .0 23 10 474 − 052 13 032 293 .25333 14. 97 0. 3 561 .5 322 7 8 71 × 10 5 − × 10 8 7 411327 0 − .8 1 − 521 0.931 234.4 904 558 840 8 1 42 2 95 3.3 .0 2 032 052 3.25334 0 562 − 323 −.8521 0.931 234.4905 1 558 2 841 3.3 .0 2 032 052 3.25333 561 3228 5 Travel Time Setup Time 1−.1605 0.642016 2315 0 6 4.1 .4994 8309 6 5 − .8173 0.143 349 257 2 4 0 ..0 8 6 × 10 877 7 − 7125 0 Trav 6 − .7 el Ti 10 396 .10 Setup Time 14 me 066 1−.1 1 24 8.5 605 .8 0.642818 016 161 231391 5 0 6 4.1 991 .4 0 − .7 994 10 830 396 9 .10 6 14 5 − .8173 0.143 1 066 8..5 8 257 818 349 161 391 2 4 0 ..0 8 6 9914

8777126 −10.1006624 8.8161991 −10.10066 8.81619914 − × 10 2 −5 0.739614 1.5818391 0.739614 1.5818391 R-Squar Pi e ck Ti Search Ti 0.97467306 me me 1 0..05777 368119 4883 7 00..16 Residual 068 9599 9 100..082 7713293 474 1714.3 .571 × 10− × 10−233,608.31 8 0 Pi − .8521 ck Ti 0.931 Search Ti 904 me 558 me 1976.96 8 1 0..05 1 42 2.3 777 .0 368032 119 052 488334 3 7 00..16 0 562 −.8521 068 9599 0.931 9 905 1 00.7 1 .082 558 2 713 .3 .0032 293 052 474 333 14.3 561 .58 71 × 10 5 − × 10 8 0 − .8521 0.931 904 558 8 1 42 2.3 .0032 052334 0 562 −.8521 0.931905 1 558 2.3 .0032 052333 5618 5 Travel Time Setup Time 1−.1605 0.642016 2315 0 6 4.1 .4994 8309 6 5 − .8173 0.143 349 257 2 4 0 ..0 8 6 8777126 −10.10066 Setup Time 24 8 − .8 0.642161 231991 6 4.4 −10 830 .10 6 066 8 −0.143 .8161 257 991 4 0.8 4

8777126 −10.1006624 8.8161991 −10.10066 8.81619914 − × 10 2 −5 0 Trav .7 el Ti39614 me 1.1 1.5 605818 016391 5 0.1 0.7 994 396 9 14 5.8173 1.5818 349 391 2.06 − × 10 2 −5 0.739614 1.5818391 0.739614 1.5818391 Adjusted Pick Time Search Time 1 0..05777 368119 4883 7 00..16068 9599 9 100..082 7713293 474 14.3 .571 × 10− × 10 8 0 Pi − .8521 ck Ti 0.931 Search Ti 904 me 558 me 8 1 0..05 1 42 2.3 777 .0 368032 119 052 488334 3 7 00..16 0 562 −.8521 068 9599 0.931 9 905 1 00.7 1 .082 558 2 713 .3 .0032 293 052 474 333 14.3 561 .58 71 × 10 5 − × 10 8 0 − .8521 0.931 904 558 8 1 42 2.3 .0032 052334 0 562 −.8521 0.931905 1 558 2.3 .0032 052333 5618 5 Travel Ti 0.96871378 me 1.16050165 0.1Reg 994 T a 9 otal rding th 5.8173349 21 e coeffi 2. ci 0 ent 6 s 1,326,978.96 , if a − × 10 2 −5 Tra ll ot 0 v . her 7 el Ti396 me predict 14 1.1 o 1. r v 5 605 a 818 016 ri 5 abl 0. e 1 s rem Reg 391 0.7 994 a 9 a 396 i rd5 n . const ing th 14 8173 1. a 5 349 nt, e e coeffi 8182. a 0 ch cient 6 s, 391 if a − × 10 2 −5 ll ot 0. her 7396 predict 14 o 1. r v 5 a 818 riables rem 391 0.7 a 396 in const 14 1. a 5 nt, e 818 ach 391 R-Squar Pi e ck Time Search Time 1 0..05777 368119 4883 7 00..16068 9599 9 100..082 7713293 474 14.3 .571 × 10− × 10 8 0 Pi − .8521 ck Ti 0.931 Search Ti 904 me 558 me 8 1 0..05 1 42 2.3 777 .0 368032 119 052 488334 3 7 00..16 0 562 −.8521 068 9599 0.931 9 905 1 00.7 1 .082 558 2 713 .3 .0032 293 052 474 333 14.3 561 .58 71 × 10 5 − × 10 8 0 − .8521 0.931 904 558 8 1 42 2.3 .0032 052334 0 562 −.8521 0.931905 1 558 2.3 .0032 052333 5618 5 coefficient is Regard viewed ing th as the e coeffi av ci er ent ag s,− e 2 incre if a ase ll ot in her the response v predictor vari ar coei ablab ffi e le fo Rega r e cient is s remai rd a nch un view ing th it incre ed const as the ant, e e coeffi a cise aver ch ent ag s,− e 2 incre if a ase ll ot in her the response v predictor vari ari ablab e le for e s remai a nch unit incre constant, e ase ch Standar Pi d ck Time Search Time 1 0..05777 368119 4883 7 00..16068 9599 9 100..082 7713293 474 14.3 .571 × 10− × 10 8 0 Pi − .8521 ck Ti 0.931 Search Ti 904 me 558 me 8 1 0..05 1 42 2.3 777 .0 368032 119 052 488334 3 7 00..16 0 562 −.8521 068 9599 0.931 9 905 1 00.7 1 .082 558 2 713 .3 .0032 293 052 474 333 14.3 561 .58 71 × 10 5 − × 10 8 0 − .8521 0.931 904 558 8 1 42 2.3 .0032 052334 0 562 −.8521 0.931905 1 558 2.3 .0032 052333 5618 5 44.681535 in a coe part ffi ic Rega ul rda cient is r predict viewed ing th or e coe va as the ffi riab av cientle ers, [7 ag 2, e 7 if a 3]. incre Lookin ase ll ot in her g at the t predicthoe coe r varffi response v i c a i in a r coe ablent iab ffi e s, it become partic Rega ul le fo s rema rda r e cient is i ra nch view ing th s un constclear that predict ed a or nt e coe va it incre as the , e ffi riab a cise av ch entle ers, [7 ag 2, e 7 if a 3]. incre Lookin ase ll ot in her g at the t predicthoe coe r varffi response v i c a i r ablent iab e s, it become le for e s remai a nch s un constclear that it incre ant, e ase ch Error Pi (SE) ck Time 1.07771193 0.10689 10.082293 1.37 × 10−8 0 Pi .8521 ck Ti 904 me 8 1.0 1.3 777032 119334 3 0.1 0.8521 0689 905 10 1 .082 .3032 293 333 1.38

7 × 10−8 0.85219048 1.3032334 0.8521905 1.30323338 in a coe part ffi ic Rega ul rda cient is r predict viewed ing th or e coe va as the ffi riab av cientle ers, [7 ag 2, e 7 if a 3]. incre Lookin ase ll ot in her g at the t predicthoe coe r varffi response v i c a i in a r coe ablent iab ffi e s, it become partic Rega ul le fo s rema rda r e cient is i ra nch view ing th s un constclear that predict ed a or nt e coe va it incre as the , e ffi riab a cise av ch entle ers, [7 ag 2, e 7 if a 3]. incre Lookin ase ll ot in her g at the t predicthoe coe r varffi response v i c a i r ablent iab e s, it become le for e s remai a nch s un constclear that it incre ant, e ase ch Observations 22

the travel time (1.1605) has the greatest positive correlation with the throughp the travel time (1 ut ti .1605 me ) haan s d

the greatest positive correlation with the throughput time and coefficient is Regard viewed ing th as the e coeffi av ci er ent ag s, e incre if a ase ll ot in her the response v predictor vari ar coei ablab ffi e le fo Rega r e cient is s remai rd a nch un view ing th it incre ed const as the ant, e e coeffi a cise aver ch ent ag s, e incre if a ase ll ot in her the response v predictor vari ari ablab e le for e s remai a nch unit incre constant, e ase ch influences it the tra in a vel ti particul signi m aer (1 ficant .1605 predict)oly r . ha How s variab ev le er, the grea [72,b7e3ca test p ]. u o s si e ti tvh e e Lookin val g at u t e correla h is ti ab e coe ov in on wi ffi e 1, fl the tra ci in a a v ents part ce ic rt uences it el ti ul ain m aer inac signi (1 fi th the throughp .16 , it becomes curac cant ut ti 05 predict)oly r . me hav y a s is How nd clear that riab ev le er, the grea [72,b7e3ca test p ]. u o s si e ti tvh e e Lookin val g at u t e correla h is ti ab e coe ov on wi ffi e 1, ci a ents certain inac th the throughp , it becomes curac ut time y a is nd clear that Item Coefficients SE coeffiReg t-Stat cient is ard viewed ing th p-value as the e coeffi av ci er ents Lower ag , e if a 95% increase ll ot Upper in her the 95% predictor vaLower response v ri ar coeiffi able 95.0% able fo Rega r e cient is s remai rd a n Upper ch un viewed const ing th 95.0% it incre as the ant, e e coeffi a cise aver ch ent ag s, e incre if a ase ll ot in her the response v predictor vari ari ablab e le for e s remai a nch unit incre constant, e ase ch influences it the tra in a vel ti particul signi m aer (1 ficant .1605 predict)oly r . ha How s variab ev le er, the grea [72,b7e3ca test p ]. u o s si e ti tvh e e Lookin val g at u t e correla h is ti ab e coe ov in on wi ffi e 1, fl the tra ci in a a v ents part ce ic rt uences it el ti ul ain m aer inac signi (1 fi th the throughp .16 , it becomes curac cant ut ti 05 predict)oly r . me hav y a s is How nd clear that riab ev le er, the grea [72,b7e3ca test p ]. u o s si e ti tvh e e Lookin val g at u t e correla h is ti ab e coe ov on wi ffi e 1, ci a ents certain inac th the throughp , it becomes curac ut time y a is nd clear that Intercept 44.3845662 132.177 coeffi 0.335797 present due to cient is view 0.74113271 multicollineari ed as the aver − ag234.484095 ty. The de e increase in 323.25323 pendent vari the − response v 234.4841 ables of travel time present due t ( o ar coeiab ffi le for e cient is a 323.253227 p = 0. mult 0000206 icollin ),

earity. The dependent variables of travel time (p = 0.0000206), ch un view it incre ed as thease

average increase in the response variable for each unit increase influences it the tra in a vel ti particul signi m aer (1 ficant .1605 predict)oly r . ha How s variab ev le er, the grea [72,b7e3ca test p ]. u o s si e ti tvh e e Lookin val g at u t e correla h is ti ab e coe ov in on wi ffi e 1, fl the tra ci in a a v ents part ce ic rt uences it el ti ul ain m aer inac signi (1 fi th the throughp .16 , it becomes curac cant ut ti 05 predict)oly r . me hav y a s is How nd clear that riab ev le er, the grea [72,b7e3ca test p ]. u o s si e ti tvh e e Lookin val g at u t e correla h is ti ab e coe ov on wi ffi e 1, ci a ents certain inac th the throughp , it becomes curac ut time y a is nd clear that Setup Time −0.6422316 4.48306 search −0.1432574 time present du (p e t = o 0.0 0.88777126 451 mult 1), a icollinnd pi eari −10.1006624 cking ti ty. The m de e (p 8.8161991 = 0.0000 pendent var 00 i 137 −10.10066 ) correla search ables of trav te wi time present du (p el time e t ( o 8.81619914 th the dependent = 0 p .0 = 451 0. mult 0 1), 000 a icollinn 206 ear d pi ), i cking ti ty. The m de e (p = 0.0000 pendent var 00 i 137) correla

ables of trav te with the dependent el time (p = 0.0000206 ), influences it the tra in a vel ti particul signi m aer (1 ficant .1605 predict)oly r . ha How s variab ev le er, the grea [72,b7e3ca test p ]. u o s si e ti tvh e e Lookin val g at u t e correla h is ti ab e coe ov in on wi ffi e 1, fl the tra ci in a a v ents part ce ic rt uences it el ti ul ain m aer inac signi (1 fi th the throughp .16 , it becomes curac cant ut ti 05 predict)oly r . me hav y a s is How nd clear that riab ev le er, the grea [72,b7e3ca test p ]. u o s si e ti tvh e e Lookin val g at u t e correla h is ti ab e coe ov on wi ffi e 1, ci a ents certain inac th the throughp , it becomes curac ut time y a is nd clear that Travel Time 1.16050165 0.19949 variab search 5.8173349 le of t time present du h (p e t = o 0.02.06 roughp 451 mult × ut t 1) i10 icollin − , an 5 med pi eari 0.739614 and a ckire st n ty. The at g ti de ist me i ( ca p 1.5818391 ll = y s 0.0 i pendent v gn 000 ari ifi 00137 v0.739614 cant as the ariab ) correla search ables of trav p-v present dualue le of t time h te wi (p el time e t = ( o 1.5818391 s ar 0 p .0 = e less tha roughp 0. mult ut 451 0 t 1) i 000m , a icollin e n 206n th the dependent ear and a d pi ), i ckire st n ty. The at g ti de ist me i ( ca p ll = y s 0.0 i pendent v gn 000 ari ifi 00cant as the 137) correla ables of trav p-value te wi el time ( s ar p = e less tha 0.0000206n th the dependent ), present d infl the trav ue t uences it el timoe mult signi (1 fi .16 icollin cant 05) ly. ha ear s ity. The However, the grea d beecpendent v a test p u o s si e ti tvh e e varliables of trav ue correla is ti abov infl on wi the trael time present d e 1, a v ue t cert uences it el tim ( o e p ain (1= signi 0 fi th the throughp .16 . mult 0 inac0 000 cant ut ti 5) l 206 icollin curac y. me ha y an s ), earity. The is How d ever, the grea d beecpendent v a test p u o s si e ti tvh e e varliables of trav ue correla is ti abov on wi el time e 1, a cert (p ain = 0 th the throughp .0 inac 000 ut ti 206 curac me y an), is d Search Time 0.53684887 0.69599 0. v 05 ari [7 ab search 0.7713474 4]. Th le of t time ( e v hp = a 0.04.51 roughp 451 × riable ut t 1) i10− , an 2 med pi − “setup-t 0.93155842 im and a cki e” rn ( e st g tip atist me i ( ca p 2.0052562 ll = y s 0.0 ign 000 ifi 00137 − = 0.8878 > 0.05 0. v 0.931558 ) seem 05 ari s to ha [7 ab search 4] cant as the ) correlap-v le of t time v . Th te wi ( e alue hp 2.00525615 no si e v = a0ri s ar .0 gni ab roughp le ut 451 fi t 1) i, cant “s aet me n up e less than th the dependent -t d pi im and a cki e” rn ( e st g tip at m = 0.887 ist e i ( ca p ll = 0.8 y s 0 > i 0.05 gn 000 ifi 00 ) seem 137 s to ha cant as the ) correlap-v v te wi e no si alues ar gnificant e less than th the dependent present d infl ue t uences it o mult signifi icollin cantly. earity. The However, d beecpendent v ause the varliables of trav ue is abov infl el time present d e 1, a ue t cert uences it ( o p ain = signi 0 fi . mult 0 inac 000 cantl 206 icollin curac y. y ), earity. The is However, d beecpendent v ause the varliables of trav ue is abov el time e 1, a cert (p ain = 0.0 inac 000206 curacy ), is Pick Time 1.07771193 0.10689 0. v 05 ari [7 ab search 10.082293 4]. Th le of t time ( e v hp = a 0.01.37 riab roughp 451 × le ut t 1) i10 , a − n 8 “set meup-t d pi 0.85219048 im and a cki e” rn ( e st g tip atist me i ( ca p 1.3032334 = 0.887 ll = 0.8 y s 0 > i 0.05 gn 000 ifi 00137 0.8521905 ) seem 0. v 05 ari s to ha [7 ab search 4] cant as the ) correlap-v le of t time v . Th te wi ( e alue hp 1.30323338 th the dependent = 0.04511), an

d picking time (p = 0.000000137) correlate with the dependent

influence on the throughput time of the process, and this is d inu fle to its smaller uence on th e va per no si ri s arab roughp c utentage e throughput time of the gni le fi ti cant “set meup e less than -tim and a e” r ( e st process, p at = 0.887 isticall and t 8 y s > i gn h i is is d 0.05 fi ue to its smaller ) seems to ha cant as the p-v ve alue per no si s ar centage gnificant e less than variable of t search time present du h ( e troughp p = o 0.0 mult ut 451 t 1) im , a icollin e n and a d pi eari ckire st n ty. The at g ti de ist me i ( ca p ll = y s 0.0 i pendent v gn 000 ari ifi 00cant as the 137 variab ) correla search ables of trav p-v present dualue le of t time h te wi (p el time e t ( o s ar = 0 p .0 = e less tha roughp 0. mult ut 451 0 t 1) i 000m , a icollin e n 206n th the dependent ear and a d pi ), i ckire st n ty. The at g ti de ist me i ( ca p ll = y s 0.0 i pendent v gn 000 ari ifi 00cant as the 137) correla ables of trav p-value te wi el time ( s ar p = e less tha 0.0000206n th the dependent ), of time in 0. fl 05 [7 in the uence on t 4]. Th ov h erall pic e variable k in “s g process. e throughput time of the etup-time” ( process, p = 0.887 and t 8 > h 0.05 of time is is d in 0. u fl ) seem 05 [7 in the uence on t s to ha 4] v . Th ov h e erall pic e to its smaller e va per no si riab c gni le kfi in “s g process. entage e throughput time of the cant etup-time” ( process, p = 0.887 and t 8 > his is d 0.05 ue to its smaller ) seems to have per no si centage gnificant variable of t search time h ( roughp p = 0.0 ut 451 t 1) im , a e n and a d pickire st n at g ti ist me i ( ca p ll = y s 0.0 ign 000 ifi 00cant as the 137 variab ) correla search p-value le of t time h te wi (p s ar = 0.0e less tha roughput 451 t 1) im , a e n n th the dependent and a d pickire st n at g ti ist me i ( ca p ll = y s 0.0 ign 000 ifi 00cant as the 137) correlap-value te wi s are less than th the dependent of time in 0. fl 05 [7 in the uence on t 4]. Th ov h erall pic e variable k in “s g process. e throughput time of the etup-time” ( process, p = 0.887 and t 8 > h 0.05 of time is is d in 0. u fl ) seem 05 [7 in the uence on t s to ha 4] v . Th ov h e erall pic e to its smaller e va per no si riab c gni le kfi in “s g process. entage e throughput time of the cant etup-time” ( process, p = 0.887 and t 8 > his is d 0.05 ue to its smaller ) seems to have per no si centage gnificant 0. varThe 05i [7 ab r 4]egression The regressio . Th le of t e v h a analysi n analy riab roughp le ut ti ss “s m further eteup-tim and ar helps e” ( e stp at explain is further helps expl = 0.887 isticall RO1, ain RO 8 y s > i gnifi concluding 1, concludi 0.05) seem 0. v 05 ari [7 cant as the ab that ng th s to ha 4]. Th p-v le of t optimising at opti The regressio m n isi ve h no si e v alue ari s ar gni ab roughp le ut t the ng t analys he

is further helps explain RO1, concluding that optimising the infl fiicant “set meup e less than -tim and a e” r ( e stp at = 0.887 isticall 8 y s > i 0.05 gnifi ) seems to ha

cant as the p-v ve no si alues ar gnificant e less than The regressio of time in the uence on tov h n analy erall pick sis further helps e ing process. e throughput time of the xplain process, RO and t 1, c h onclud is is d inu fl ing t of time hat in the uence on t op ov h t e to its smalleri The regressio m n is per icng erall pick t analys h in e is further helps e g process. entage e throughput time of the xplain process, RO and t 1, c h onclud is is du ing that opt e to its smallerimis per icng the entage independent in 0. fl 05 [74] variables independent vari uence on t . Th h e vari can able change ables ca “setup the -tim thr e” oug e throughput time of the (p hput time process, = 0.8878 > and and t h 0.05incr 0.ease is is d inu fl ) seem 05 [ ef 7 fi 4] ciency independent v uence on t s to hav . Th h e .a e vIn

n change the throughput time and increase eri e to its smaller aricontinua- fficiency. In

ables can change the throughput time and increase efficiency. In per no si ab centage e throughput time of the gni le fi cant “setup-time” ( process, p = 0.887 and t 8 > his is d 0.05 ue to its smaller ) seems to have per no si centage gnificant independent of time v in the a ovriables c The regression erall pic a analy

k n change the throughput time and increase e sis further helps e ing process. xplain RO1, c independent oncluding t of time h v at in the a ovrffi i opti The regressio c n i mency. In ables c isi erall pic a ng analy

k n change the throughput time and increase e t s h in e is further helps e g process. xplain RO1, concluding that ffi opti ci mency. In ising the tion, infl these continua of time same in the uence on th variables tion, these sa overall pic wer kin e me va influenced riables we g process.

e throughput time of the heavily re infl process, by the and th pick-by-vision uenced heavily b contin y ua of time is is d inu fl app in the uence on tov h roach, the pick-b tion, these sa e to its smaller perc thus y-vision me v

ariables were influenced heavily by the pick-by-vision erall picking process. entage

e throughput time of the process, and this is due to its smaller percentage continuation, these sa independent vari The regression me v ables ca analys ariables were is further helps e in x fl pl uenced heavily b ain RO1, c conti o n ncludi y ua the pick-b

n change the throughput time and increase e independent ng th v at arffi i opti The regressio c n i m y-visio tion, these sa ables c isi a ng t analys n me v h aria ency. In e bles were is further helps e in x fl pl uenced heavily b ain RO1, concludi y the pick-b

n change the throughput time and increase e ng that ffi opti ci m y-visio ising t n h ency. In e achieving of time higher approach, th in the ef ov ficiency erall pic .

us achieving higher efficiency.

approach, thus achieving higher efficiency. king process.

of time in the overall picking process. continuation, these sa independent vari The regression me v ables ca analys ariables were is further helps e in x fl pl uenced heavily b ain RO1, c conti o n ncludi y ua the pick-b

n change the throughput time and increase e independent ng th v at arffi i opti The regressio c n i m y-visio tion, these sa ables c isi a ng t analys n me v h aria ency. In e bles were is further helps e in x fl pl uenced heavily b ain RO1, concludi y the pick-b

n change the throughput time and increase e ng that ffi opti ci m y-visio ising t n h ency. In e Scenario Scenari approach, th Analysis: o Analysis The regression The us achieving analys data sets : The data higher effici aggr ency egated sets aggrega . t is further helps expl to ain a ROmean ed to a me 1, co value, an va ncludi and lue, Scenari approach, o th ng th the at op r ti The regressio espective and the respe Analysis c us achieving tive : The data sets aggrega higher efficiency.

ted to a mean value, and the respective m n ising t analys he

is further helps explain RO1, concluding that optimising the approach continua , thus achieving tion, these sa independent vari higher e me v ables ca aria ffi b cienc les w y e . re infl approach uenced heavily b contin y ua , thus achieving the pick-b tion, these sa

n change the throughput time and increase e independent varffi i ci higher e y-visio ables ca n me v aria ency. In ffi b cienc les w y e .

re influenced heavily by the pick-b

n change the throughput time and increase effici y-vision ency. In standar stand d a deviation rd dev Scenari i o independent var of ation Anal i the of ysis test the ables ca series test se : The datacan ries cbe an seen in sets aggrega T be seent able in T 4 a . This ble 4. ed to a me data stand an vaset This da ard serves ta s lue, e Scenarit se devi o independent v as rv

n change the throughput time and increase e ari a ation Anal ffi basis es as of the and the respe ysis ci ables cfor a bcasi tivs test se e rie : The data s can be seen sets aggrega in t Table 4. ed to a m This d ean va ata s lue, et serves as a b and the respecasi tivs e ency. In

an change the throughput time and increase efficiency. In Scenari approach continua , o th Analysis: The data us achieving

tion, these same varia sets aggrega higher effi b cienc les w y e . re in ted to a m fl ean va conti lue, approach uenced heavily b n y ua , and the respe Scenario th Analysi the pick-b s tion, these sa c us achieving tiv y-visio en me v : The data aria sets aggrega higher effi b cienc les w y e . re in ted to a m fl ean value,

uenced heavily by and the respe the pick-b ctiv y-visio en further for stand conti analyses. further ard devi nua Based analys ation of on es. tion, these sa the Base the collected d on test series c me variab data the co an les we and re i determined llected dat be seen in a Table nfl time 4. for elements and determ stand in further This da a ta s rd e dev uenced heavily b contin y ua in t se i combination ed time e analy rv l s ation e es m of ents i es. Base as a b the as n i d on s the co test series canllected dat be seen in a T and determ able 4. in This da ed time ta set se e rv le es ments i as a bas n i s the pick-by-visio tion, these sa n me v