Preview text:

lOMoAR cPSD| 40799667

Mills 2008 - Globalization and Inequality

Advanced reading (Đại học Khoa học Xã hội và Nhân văn, Đại học Quốc gia Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh) lOMoAR cPSD| 40799667 European Sociological Review

VOLUME 25 NUMBER 1 2009 1–8 1

DOI:10.1093/esr/jcn046, available online at www.esr.oxfordjournals.org

Online publication 30 August 2008 Globalization and Inequality Melinda Mills

Globalization is increasingly linked to inequality, but with often divergent and polarized findings.

Some researchers show that globalization accentuates inequality both within and between

countries. Others maintain that these claims are patently incorrect, arguing that globalization D o

has disintegrated national borders and prompted economic integration, lifting millions out of w n l

poverty, and closing the inequality gap. This article presents a review of current research that o ade

links globalization to inequality. Core problems behind contra-dictory findings appear to rest in d fr

the operationalization of inequality and globalization, availability and quality of data, population- o m

weighted versus unweighted estimates; and, the method of income calibration to a common h ttp

currency in the study of income inequality. A theoretical model charts the mechanisms linking ://es

globalization to inequality, illustrating how it generates increased inequality within industrialized r. o x

nations and decreased inequality within developing economies. The article concludes with a fo rd

description of the papers in this special issue and situates them within the broader literature. j o u rn al s.org/ at Cornell Introduction

problems in the study of inequality. The second section U n i

then defines globalization and develops a theoretical v er s

The rise of globalization has been accompanied by the

model to chart the mechanisms that link it to inequality ity

debate of whether it comes at the cost of grow-ing

in industrialized and developing economies. The article L ib

inequality. Globalization is increasingly linked to

concludes with a description of the papers in this rar y

inequality, but with often divergent and polarized

special issue and situates them within the broader on

results. Critics of globalization have argued that it

literature on this topic. Each article is provocative and D e

accentuates inequality both within and between coun-

challenging in its own right, addressing the many sides cem

tries (Firebaugh, 2003; Wade, 2004). Although globa-

of this topic from different areas of the world and b er

lization may improve both the relative and absolute

equally different perspectives within sociology. 1 5 ,

incomes of individuals around the world, some findings 2 0 1

show that there are clear winners and losers. Others Has Inequality Grown? 4

maintain that these claims are patently incor-rect,

arguing that globalization has disintegrated national A Critical Examination

borders and prompted economic integration, lifting

millions out of poverty and closing the inequal-ity gap

A review of the literature on globalization and

(Dollar and Kraay, 2002). But which of these findings

inequality reveals that evidence is vigorously argued in

are correct? Does globalization lead to higher

all directions. Some researchers appear to convinc-ingly

inequality? Why are there so many divergent results?

argue that there has been a growth in inequality over

The aim of this introductory article is to present a

time (Wade, 2004) whereas others adamantly report

review of current research on globalization and inequal-

stability or even a reverse in the inequality trend over

ity. The first section engages in a critical summary of

time (Firebaugh and Goesling, 2004; Milanovic, 2005;

the central findings in this area of research, followed by

Sala-i-Martin, 2006). The core problem behind these

isolating key conceptual and methodological

seemingly contradictory findings appears to be

The Author 2008. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

For permissions, please e-mail: journals.permissions@oxfordjournals.org lOMoAR cPSD| 40799667 2 MILLS

a methodological one, related to four key issues:

comparisons (Ravallion, 2003). The central difference

(i) the operationalization of inequality, (ii) availability

is whether the measures are calculated as household

and quality of data, (iii) population-weighted versus

consumption-based Gini indexes or using income-based

unweighted estimates; and, (iv) in the study of income

surveys. The difference is not trivial since con-

inequality, the technique used in the calibration of

sumption-based indices are both more commonly used

incomes into a common currency. These choices result

in developing economies (e.g. Asia, Africa, Central and

in different predictions about not only the direction of

Eastern Europe) and also produce estimates of lower

inequality, but also the onset of the timing of changes in

inequality. The reason that they are often applied in inequality trends.

these countries, as opposed to the income-based mea-

The classic and perhaps most obvious factor related

sures often used in developed economies, is attributed

to the divergent inequality findings is both a concep-

to the fact that the measurement of incomes is often

tual and data-related question: How is inequality

difficult in these contexts, due to higher levels of self- D

operationalized or measured? This is interrelated to the

employment in agriculture or business (IMF, 2007). o w

central research problem or motivation of the research,

Since consumption is also often self-reported, these n lo

but also to the second core issue, which is the

measures likewise suffer from typical methodological ade

availability and/or quality of data. The majority of the

problems such as differences in definitions of con- d fr

globalization and inequality literature has focused on

sumption; recall problems and variation in the length of o m

income inequality, often measured as a change in the

recall period, and other related factors. Income-based http

Gini coefficient (critically discussed in more detail

measures also suffer from similar data collection ://es

shortly) (Alderson and Nielson, 2002). Alternative

problems, including the fact that surveys are often not r. o

measures such as the mean logarithmic deviation of

entirely nationally representative and underreport the x fo

income (MLD) index of inequality are sometimes used

income of high-income groups, thereby under- rd jo

(Sala-i-Martin, 2006), but the Gini coefficient remains

estimating inequality. The operationalization of glob- u rn the dominant choice.

alization is another related issue, discussed in the next al s.o

Classic sociological approaches have characterized section. rg/

inequality as a multidimensional construct based on the

A third culprit of differences in estimates related to at C

stratifying factors of not only income, but also other

globalization and inequality is whether countries are o rn

social and cultural domains (Weber, 1958; Mills, 1963;

weighted by population size or treated merely as equal ell

Dahrendorf, 1979). Studies that deviate or expand upon

units in cross-national comparisons (Firebaugh, 1999). U n i

inequality beyond income are, however, rare. Sen Population-weighted studies report that income v er s

(1999) is an exception, maintaining that we need to

inequality has declined, due to the relatively high ity

examine inequality in personal freedoms. More

weight of China and India, where inequality has sharply L ib

recently, Goesling and Baker (2008) introduced a

declined over the past 20 years (Milanovic, 2005; Sala- rar y

multidimensional operationalization of inequality, by

i-Martin, 2006). These types of results provide a better on

examining not only income, but also health and

picture of global inequality as opposed to variations in D ecem

educational inequality across countries. Beyond the

cross-national differences. Unweighted results that treat

actual measure, there is also the question of whether

each country as equal are more useful to distinguish b er

inequality is studied as the unequal distribution of between cross-national differences related to 1 5 ,

income within or between countries (Alderson and

institutional effects such as national eco-nomic policy 201

Nielsen, 2002; Beckfield, 2006), or a combination of

or growth (Goesling and Baker, 2008). 4 both (Milanovic, 2005).

A final methodological problem that occurs when

A growing body of literature has focused on trends in

income is used as the central measure is the calibration

within-country income inequality. Here, the Gini index

of incomes to a common comparative currency. This in

is the most commonly used measure, which summarizes

turn produces divergent predictions about the timing or

the income distribution within a country (Ravallion,

onset of changes in inequality trends. Two central

2003). It illustrates the range between a perfectly equal

techniques used to calibrate incomes into a common

distribution (a Gini coefficient of 0) to the highest

currency across the countries are either via the

possible condition of inequality of

purchasing power parity (PPP) or unadjusted foreign

where one person would hold all of the income (a Gini

exchange rates. Studies that calibrate incomes using

coefficient of 1). Although the Gini measure is widely unadjusted foreign exchange rates, such as applied, there are some serious conceptual,

Korzeniewicz and Moran (2007), find that the decline

methodological, and definitional issues that make it

in inequality did not come about until the 1990s.

difficult to interpret when engaging in cross-national

Whereas those who use the PPP converters show lOMoAR cPSD| 40799667 GLOBALIZATION AND INEQUALITY 3

that population-weighted inequality started to decline

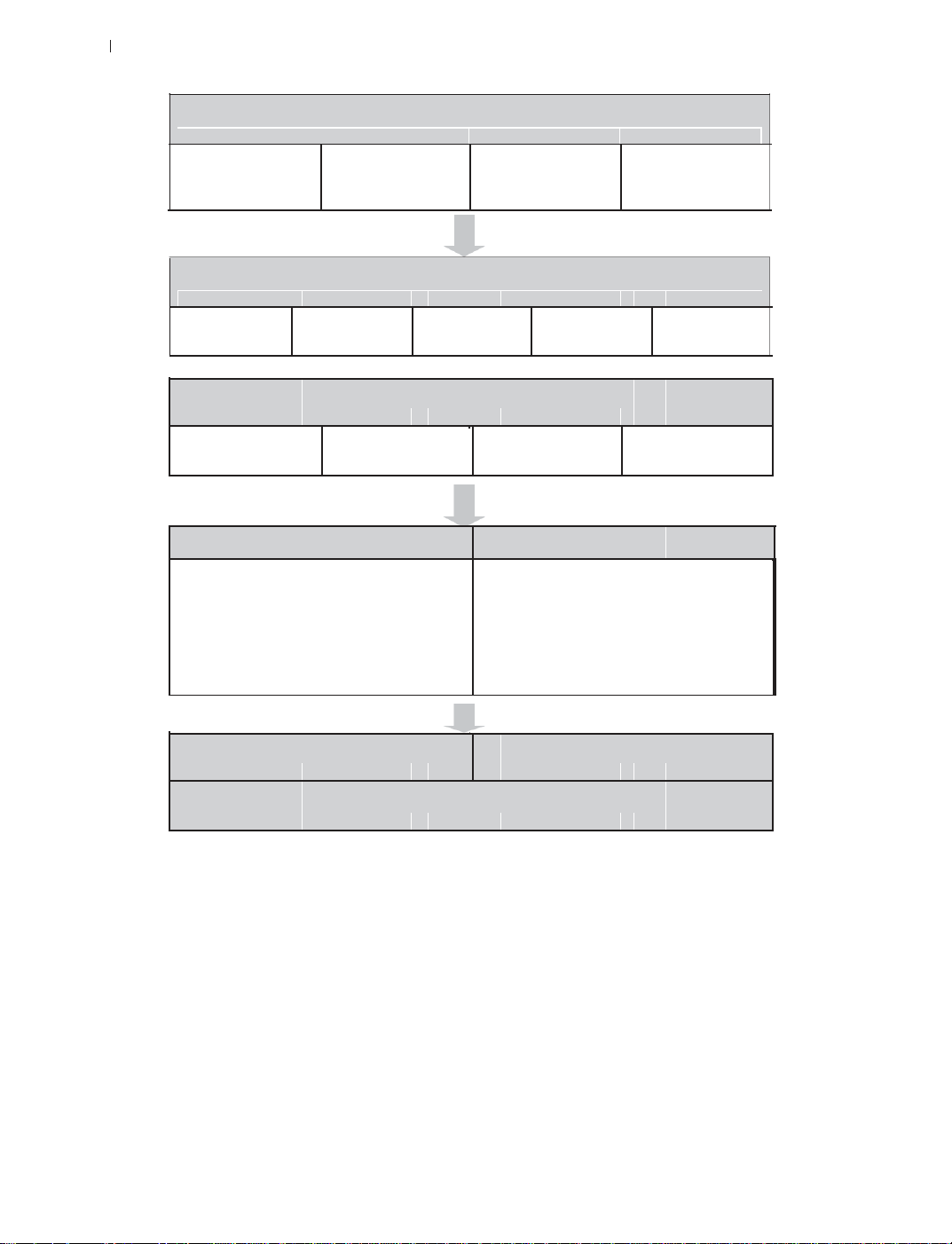

et al., 2008). Globalization can be defined as four

almost 10 years earlier in the early 1980s (Goesling and

interrelated structural shifts that roughly occurred since Baker, 2008).

the 1980s of: (i) internationalization of markets and

Although these measurement problems exist, there

declining importance of borders for economic

appears to be a general consensus about the trends in

transactions, (ii) tougher tax competition between

inequality. Among researchers using population-

countries, (iii) rising worldwide interconnectedness

weighted inequality measures, results show that there through new Information and Communication

has been a decline in income inequality across coun-

Technologies (ICTs), and (iv) the growing relevance

tries (Milanovic, 2005; Sala-i-Martin, 2006). Using and volatility of markets (Mills and Blossfeld,

population-weighted income inequality data from 138 2005). The mechanisms, which link these

countries from 1979 to 2000, Sala-i-Martin (2006), for

aspects of globalization to inequality, are outlined

example, showed that the level of income inequality in Figure 1.

across countries declined sharply over time. However, D

A central engine of globalization is the internation- o w

when income shares are examined by quintiles, we see

alization of markets and subsequent decline in the n lo

that income inequality has increased mainly in the

importance of national borders for all kinds of ade

middle- and high-income countries, and less so in the

economic transactions. This includes changes in laws, d fr

low-income countries (IMF, 2007). o

institutions, or practices that make various transactions m

There is also evidence that income inequality across

(in terms of commodities, labour, services, and capital) h ttp

countries far exceeds that of inequality within coun-

easier or less expensive across national borders, includ- ://es

tries and that it has grown across time (Korzeniewicz

ing trade. The growth of international regulatory insti- r. o

and Moran, 1997; Guille´n, 2001). As Goesling and

tutions and political agreements that facilitate capital x fo

Baker (2008, p. 184) state: ‘The world’s largest

flows have generally operated to liberalize and interna- rd jo

inequalities are not defined by race, class, or gender, but

tionalize financial markets, resulting in more financial u rn

by national borders’. Average incomes in the richest

openness (Fligstein, 2002). This includes the deregu- al s.o

countries in the world far exceed those in the poorest

lation of interest rates, privatization of government- rg/

countries, with estimates of incomes that are 40–50

owned banks and financial institutions, and the removal at C

times greater in these countries (Pritchett, 1997). This of credit controls. o rn

reflects the increasing divergence between countries

A second interrelated aspect of globalization is the ell

produced by globalization, not growing convergence U

rise in tougher tax competition, often accompanied by n i

(see also Mills et al., 2008). v

‘neoliberal’ globalization tendencies. The notion that er s

An additional area of study is within-country

capital and labour are increasingly mobile works as a ity L

inequality, which is highly dependent upon the nation

powerful threat for competition. Countries have mainly ibrar

under study. Examining the Gini coefficient of income

been affected in terms of a modification of the tax y

inequality, for example, Alderson and Nielsen (2002)

structure rather than through retrenchment of the on

demonstrate that globalization explains the longitudinal

welfare state (Massey, 2009). Central neo-liberal D ecem

trend of increasing inequality across 16 OECD

measures to enhance competition include the removal

countries. By examining the impact of glob-alization

or relaxation of government regulation of economic b er

measures such as direct investment outflow, North-

activities (deregulation), a shift towards the reliance on 1 5 ,

South trade and net migration rate over the period from

price mechanisms to coordinate economic activities 2 0 1

1967 to 1992, they find rising inequality within

(liberalization) and the transfer of ownership and 4

countries such as the United States, Australia, and

control over previously public ownership to private

Denmark and declining and then rising inequality in

entities (privatization). The core of these transforma-

countries such as Germany, Japan, Great Britain, and

tions has been to enhance efficiency, productivity and the Netherlands.

profitability while simultaneously allowing firms and

nations to be more competitive, flexible and react more

rapidly to change (Montanari, 2001).

The Impact of Globalization on

World trade, trade integration, and financial openness Inequality

have significantly grown since the early 1980s (IMF,

2007). World trade has, in fact, grown five times from

Globalization represents a set of economic, political,

the 1980s to 2005 with trade openness increasing

and cultural processes that operate simultaneously and

particularly in the former Eastern bloc and developing

has suffered from similar operationalization problems

Asian countries (IMF, 2007, p. 33). Integration and

(Held et al., 1999; Guille´n, 2001; Raab

financial openness has also intensified, lOMoAR cPSD| 40799667 4 MILLS GLOBALIZATION

Internationalization of Increased competition New ICTs & increased Rising relevance and markets between nations interconnectedness volatility of markets INCREASES IN: Financial Trade Foreign Direct ICT capital Migration and openness Investment investment & use mobility of D workers o w n lo ad e

NATIONAL INSTITUTIONAL FILTERS d fr o m Education systems Employment & Welfare regime Migration restrictions h tt industrial relations p : / systems /es r. o x fo rd j o u rn

INDUSTRIALIZED COUNTRIES DEVELOPING ECONOMIES al s Deindustrialization Industrialization .or g

Weaker bargaining position of labour / a

Capital flight/ international relocation of jobs Capital arrival/new jobs t C o

Increased premium on higher skills for rn knowledge-based industries

Increased premium on lower skills for labour- ell

Shift from higher wages in industrial sector intensive industries U n

to lower wages in service sector

Increase in wages for lower-skilled workers iver

Rise in higher-skilled workers’ incomes

Reduction in higher-skilled workers’ incomes si ty L ibrar y INCREASE IN INEQUALITY DECREASE IN INEQUALITY o n D ecem

AGGREGATE OBSERVATIONS OF INEQUALITY b e r 1 5 , 201

Figure 1 Mechanisms linking globalization to inequality. (Source: Adapted from Mills and Blossfeld, 2005). 4

particularly between the advanced economies. Trade is

in competition with low-wage workers in the South

often used as a tangible measure of globalization, using

(Wood, 1994). However, some argue that this does not

measures such as international trade, and speci-fically

hold, as the net effect of imports on average wages

‘North-South’ trade (Krugman and Lawrence, 1993;

appears to be minimal (Krugman and Lawrence, 1993).

Wood, 1994; Burtless, 1995; Alderson and Nielsen,

In addition to trade, another measure often used to

2002). As Figure 1 illustrates, trade is one factor of

capture globalization is the level of foreign direct

globalization that has the potential to increase

investment (FDI) and how it in turn impacts the income

inequality in industrialized countries due to the fact that

distribution of countries (Bornschier, Chase-Dunn and

it reduces the average wage and enhances inequalities in

Rubinson, 1978; Firebaugh, 1992). More intensive

the relative wages between skilled and unskilled

competition and the softening of trade bar-riers opens

workers. It reduces wages in the North due to the fact

new markets for firms based in industri-alized

that these workers are suddenly

countries. Globalization prompts a ‘capital flight’ lOMoAR cPSD| 40799667 GLOBALIZATION AND INEQUALITY 5

of firms as they engage in FDI to replace domestic

between individuals (Castells, 2001). New ICTs allow

production (Gereffi, 2009). Firms in search of lower

people to share information in order to connect and

labour costs and/or more lenient tax systems or

create an instant common worldwide standard of

employment regulations invest abroad. As a result,

comparison. Although the introduction of technology is

there is a process of deindustrialization in the home

not unique in itself, recent ICTs have fundamentally

country that weakens the bargaining position of work-

altered the scope (widening reach of networks of social

ers and produces rising inequality. This deindustrial-

activity and power), intensity (regularized connec-

ization entails a shift away from typically higher wages

tions), velocity (speeding up of interactions and

in the manufacturing and industrial sector in more

processes), and impact (local impacts global) of

industrialized countries to be replaced by comparatively

transformations (Held et al., 1999).

lower average wages in service sector jobs, thereby

New ICTs and technology have sometimes been

resulting in increased inequality (Alderson and Nielson,

included within the definition of globalization or as a

2002). Conversely, globalization appears to decrease D

parallel force. One way to measure the impact of ICTs o w

the level of inequality in many developing economies

is by examining the intensification of ICT capital n lo

via the growth in industrialization, new employment

investment within countries, such as higher national ade

possibilities, and increase in wages for lower-skilled

expenditures on computer hardware and software, and d fr

labour-intensive workers, accompanied by a subsequent

telecommunications equipment (Jorgenson and Vu, o m

reduction in the wages of higher-skilled workers. These

2005). Others have measured it by examining the level h ttp

factors operate together to decrease the level of

of socio-technical interconnectedness via measures such ://es

inequality within these countries. The contrasting

as the number of Internet hosts and users per capita and r. o

impacts of inequality are therefore a key reason why

other related communication technology availability x fo

results differ according to whether countries are rd

and usage within a society (Raab et al., 2008). ICTs, jo

population-weighted or treated as equal units. u

together with liberalized and internatio-nalized financial rn al

It is also not only firms that are mobile. We are

transactions, create a financial ‘super-market’ for global s.o

witnessing a growing number of migrant workers, par-

business-to-business transaction and stock exchanges, rg/

ticularly in light of more lenient mobility regulations in

cross-border banking, and finance that stretch across the at C

areas such as the European Union (Feld, 2005).

world on a real-time basis (Greenspan, 1997; Castells, o rn

Different countries have diverse levels of migrants,

2001). New technol-ogy has also prompted a wave of ell

which likewise contribute to the level of inequality

automation, char-acterized by flexible, and accelerated U n i

within each society. Borjas (2000) points to migration

production processes. It not only increases production, v er s

in the United States as a central factor contributing to

but also results in a shift from the demand for lower- ity

inequality. Borjas (2000) argues that immigration is

skilled workers to a more highly qualified knowledge- L ib

related to inequality in this context due to the fact that

based labour force (Brown and Campbell, 2002). rar y

both rises in immigration and inequality coincide with on

one another, and that there is not only a bifur-cation of

A final feature of globalization is the rise in both the D ecem

low and highly skilled migrants, but also a growth of

relevance, but also simultaneously, the volatility of

lower-skilled immigrants. Alderson and Nielson (2002,

markets. Market prices and their transformations b er

p. 1256) argue that ‘the combination of a high

increasingly convey information and set the standard 1 5 ,

immigration rate with an immigrant population

for the global demand of various goods, services and 2 0 1

characterized by low average skills and high skills

assets, and the relative costs of producing and offering 4

variance has been seen as a certain recipe for increased

them (Useem, 1996). Yet these markets are becoming

inequality’. This can be related to Grusky’s (2001)

ever more dynamic and unpredictable. Competition

work on income disparities as a function of race, class,

forces firms to operate in a state of perpetual innovation

and gender and Massey’s (2009) argument in this

and flexibility, which in turn heightens the instability of

volume that the realignment of the U.S. political

markets (Streeck, 1987). New ICTs likewise accelerate

economy and tax system is traced to racism in this

market transactions (Castells, 1996). This in turn makes country.

long-term developments of globalizing markets

A third aspect of globalization is the rising world-

inherently harder to predict. Global prices are also more

wide interconnectedness through the information and

liable to fluctuations because worldwide supply,

communication technology (ICTs) revolution, such as

demand, or both are becoming increasingly susceptible

microcomputers, the Internet, new satellite systems and

to random disrup-tions caused somewhere on the globe

fiber-optic cables. These accelerate the liberal-ization of

(for example, major scientific discoveries, technical

financial transactions and communication inventions, lOMoAR cPSD| 40799667 6 MILLS

new consumer fashions, major political upsets such as

Beck and Beck-Gernsheim propose a new theory of

wars and revolutions, economic upsets, and so on).

the ‘global generation’. In comparison to previous

Globalization is often presented as a blanket force

generations, they contend that this group departs from

impacting all nations in a similar manner. But countries

‘collective action to engage in individualist reaction’. It

have very different starting points and varying tendencies

is a generation at odds with itself and at its very heart

to accept or resist globalization, thereby influencing the

by definition ‘unpolitical’. They offer the critique of

level of within and between country inequalities (Sassen,

methodological nationalism and argue that the current

1996). National specific institutions, such as employment

global generation of youth is increasingly not limited to

and industrial relations systems, education systems, the

the borders of its own nation state. This generation, they

degree of decommodification from the welfare regime and

argue, takes on a transnational iden-tity, characterized

migration restrictions all operate as ‘filters’ of these

by growing diversity. Here, the authors enter the heated

globalization pressures (Mills et al., 2008). We know that

debate of migration and the human right to mobility.

there are distinct national variations of occupational

They also ponder the frag-mented identities of young D o w

structures and industries, patterns of labour-capital

Germans with an immi-grant background and depart n lo

negotiations, strike frequencies and collective agreements

from nation-bound generational constructs to build a ade

on wages, job security, labour conditions, and work hours

more transnational generational concept of the ‘global d fr

(Streeck, 1992; Soskice, 1993). Globalization operates to generation’. o m

disperse and fragment these national structures, and via the

The contribution by Gereffi is a strong representa- h ttp

threat of compe-tition, pose increased demands and

tion of the economic approach within this field of ://es

flexibility on the domestic labour force (Beck and Beck-

research and highlights the experiences of the emerg- r. o Gernsheim, 2009).

ing economies of China and Mexico. Although both x fo rd

countries engaged in export-oriented development jou Diverse approaches to

strategies in response to globalization, they experienced rn al

very different outcomes. Mexico took on the ultimate s

‘Globalization and Inequality’ .o

neo-liberal globalization model, characterized by FDI, rg/

privatization and financial openness. This was in con- at C

The papers in this special issue are intentionally diverse

trast to China who even in the light of high levels of o rn

and provocative, covering disparate theoretical and

foreign capital inflows and exports, still managed to ell

empirical approaches towards the topic of globaliza-

maintain a strong state-level approach. Gereffi con- U n i

tion, and inequality in addition to coverage in different

cludes by reflecting on why China has been so suc- v er s

areas of world. We start with the extreme example of

cessful in the U.S. market in comparison to Mexico, ity

the within-country inequality of the U.S. (Massey) and

which he largely attributes to supply-chain cities. L ib

then move to a discussion of intergenerational or age- rar

The final article by Buchholz and colleagues y

based inequality in Germany (Beck and Beck-

examines the impact of globalization on life course and on

Gernsheim). The focus then shifts to between country

employment careers inequalities across industria-lized D ecem

levels of inequality and diverse interpretations of

societies. It summarizes the results of a large research

globalization in Mexico and China (Gereffi). We then project (GLOBALIFE: Life Courses in the b er

conclude with an overarching paper that explores both

Globalization Process) that used micro-level panel and 1 5 ,

within and between-country inequality across the life

retrospective survey data across a variety of countries to 2 0 1

course of individuals in a variety of modern societies

examine inequalities across all phases of the life course. 4

(Buchholz et al., 2009).

They found that more highly-skilled mid-career men

The seminal contribution by Massey addresses the

were the most protected groups from the forces of

resurgence of income inequality in the United States. In

globalization, with young adults being the most

this study of arguably one of the most unequal societies

‘exposed’ and thus encountering the most difficulties.

in the world, Massey demonstrates how globalization

They conclude that globalization does not reduce, but

has resulted in extreme within-country inequality. He

rather strengthens existing social inequality struc-tures,

positions these key differences in relation to the unique which remains highly controlled by national

institutional filter within this country that exposes

institutional structures of social inequality.

individuals at the bottom of the socioeconomic

This brief review of globalization and inequality

hierarchy more overtly to globalization. Massey traces

demonstrated the importance of understanding the oper-

this inequality to America’s legacy of racism, where the

ationalization of concepts, choice of data, population-

political system aids the already wealthy to further

weighted or unweighted analyses, and the method of enhance their position.

income calibration in interpreting the seemingly lOMoAR cPSD| 40799667 GLOBALIZATION AND INEQUALITY 7

contrasting results in this area of research. Via a conceptual

modern societies. European Sociological Review,

model, this article also highlighted the potentially 25, in press.

divergent inequality outcomes in industrial versus

Burtless, G. (1995). International trade and the rise in developing economies that emerge because of earnings inequality. Journal of Economic globalization. Although globalization remains an

Literature, 33, 800–816.

inherently broad and complex construct, it is possible to

Castells, M. (1996). The information age: Economy,

partially operationalize and examine the impact of this

society and culture, Volume 1, Oxford: Blackwell.

macro-level force on different nations and the individuals

Castells, M. (2001). The Internet Galaxy. Oxford:

within them. Just as with inequality, however, it is key to Oxford University Press.

transparently express how global-ization is measured. Of

Dahrendorf, R. (1979). Life Chances. Chicago:

course, we must also contend that other exogenous factors University of Chicago Press.

are present and that direct causality is often difficult to

Dollar, D. and Kraay, A. (2002). Spreading the wealth. D

definitively establish. Regardless, there is evidence that

Foreign Affairs, 81, 120–133. o w

large changes in many societies across the world such as

Feld, S. (2005). Labor force trends and immigration in n lo

internationalization, financial openness, new ICTs and

Europe. International Migration Review, 39, 637– aded

migration are generating specific patterns of inequality in 662. fr o

industria-lized, and developing economies. The challenge

Firebaugh, G. (1992). Growth effects of foreign and m h

for the future will be handling the consequences of these

direct investment. American Journal of Sociology, ttp

increases (and decreases) in inequality and striving to 98, 105–130. ://es

create not only a more globally balanced society, but facing

Firebaugh, G. (1999). Empirics of world income r. o x

the large inequalities within our own countries.

inequality. American Journal of Sociology, 104, fo rd 1597–1630. jo u rn

Firebaugh, G. (2003). The New Geography of Global al s References .

Income Inequality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard o rg/ University Press. at C

Alderson, A. S. and Nielsen, F. (2002). Globalization

Firebaugh, G. and Goesling, B. (2004). Accounting for o r

and the great U-turn: income inequality in 16 n

the recent decline in global income inequality. ell

OECD countries. American Journal of Sociology,

American Journal of Sociology, 110, 283–312. U n 107, 1244–1299. i

Fligstein, N. (2002). The Architecture of Markets: v er

Beck, U. and Beck-Gernsheim, E. (2009). The global

An Economic Sociology of Twenty-First-Century s ity

generation and the trap of methodological nation-

Capitalist Societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton L ib

alism. For a cosmopolitan turn in the sociology of University Press. rar y

youth and generation. European Sociological

Gereffi, G. (2009). Development models and industrial on Review, 25, in press.

upgrading in China and Mexico. European D ecem

Beckfield, J. (2006). European regional integration and

Sociological Review, 25, in press.

income inequality. American Sociological Review,

Goesling, B. and Baker, D. P. (2008). Three faces of b er 71, 964–985. international inequality. Research in Social 1 5 ,

Borjas, G. J. (ed.) (2000). Issues in the Economics of

Stratification and Mobility, 26, 183–198. 2 0 1

Immigration, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Greenspan, A. (1997). The globalization of finance. The 4

Cato Journal, 17, 1–8.

Bornschier, V., Chase-Dunn, C. and Rubinson, R.

Grusky, D. B. (Ed.) (2001). Social Stratification: Class,

(1978). Cross-national evidence of the effects of

Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective.

foreign investment and aid on economic growth and Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

inequality: A survey of findings and a reanalysis.

Guille´n, M. (2001). Is globalization civilizing, destruc-

American Journal of Sociology, 84, 651–683.

tive or feeble? A critique of five key debates in the

social science literature. Annual Review of

Brown, C. and Campbell, B. A (2002). The impact of

Sociology, 27, 235–260.

technological change on work and wages. Industrial

Held, D., McGrew, A., Goldblatt, D. and Perraton, J. Relations, 41, 1–33.

(Eds) (1999). Global Transformations, Stanford.

Buchholz, S., Hofa¨cker, D., Mills, M., Blossfeld, H.-P.

CA: Stanford University Press.

et al. (2009). Life courses in the globalization

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2007). World

process: The development of social inequalities in

Economic Outlook 2007: Globalization and

Inequality. Washington, D.C.: IMF. lOMoAR cPSD| 40799667 8 MILLS

Jorgenson, D. W. and Vu, K. (2005). Information

World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No.

technology and the world economy. Scandinavian

3038, Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Journal of Economics, 107, 631–650.

Sala-i-Martin, X. (2006). The world distribution of

Korzeniewicz, R. P. and Moran, T. P. (1997). World-economic

income: falling poverty and . . . convergence,

trends in the distribution of income, 1965– 1992. American

period. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121,

Journal of Sociology, 102, 1000–1039. 351–397.

Krugman, P. and Lawrence, R. Z. (1993). Trade, Jobs

and Wages. Working Paper No. 4478, Washington,

Sassen, S. (1996). Losing Control? Sovereignty in an

D.C.: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Age of Globalization. New York: Columbia University Press.

Massey, D. (2009). Globalization and inequality:

Sen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom. New York:

explaining American exceptionalism. European Knopf.

Sociological Review, 25, in press. D

Soskice, D. (1993). The institutional infrastructure for o w

Milanovic, B. (2005). Worlds Apart: Measuring

international competitiveness: a comparative anal- n lo

International and Global Inequality. Princeton, NJ:

ysis of the UK and Germany. In Atkinson, A. B. ad Princeton University Press. e

and Brunetta, R. (Eds), The Economics of the New d fr

Mills, C. W. (1963). The sociology of stratification. In

Europe. London: Macmillan. o m

Horowitz, I. L. (Ed.), Power, Politics and People:

Streeck, A. (1987). The uncertainties of management in htt

The Collected Essays of C. Wright Mills. New York:

the management of uncertainties: employees, labor p ://

Oxford University Press, pp. 305–323. es

relations and industrial adjustment in the 1980s. r. o

Mills, M. and Blossfeld, H.-P. (2005). Globalization,

Work Employment and Society, 1, 281–308. x fo

uncertainty and the early life course: a theoretical rd jo

framework. In Blossfeld, H.-P., Klijzing, E., Mills,

Streeck, W. (1992). Social Institutions and Economic u rn

M. and Kurz, K. (Eds), Globalization, Uncertainty

Performance: Studies in Industrial Relations in al s.

and Youth in Society. London and New York:

Advanced Capitalist Economies. London: Sage. o rg Routledge, pp. 1–24. /

Useem, M. (1996). Investor Capitalism. New York: at C

Mills, M., Blossfeld, H.-P., Buccholz, S., Hofa¨cker, D. Basic Books. o r

et al. (2008). Converging divergences? An interna-

Wade, R. H. (2004). Is globalization reducing poverty n ell

tional comparison of the impact of globalization on

and inequality? World Development, 32, 567–589. U n

industrial relations and employment careers. iver

International Sociology, 23, 563–697. s

Weber, M. (1958). In Gerth, H. H. and Wright Mills, C. ity

Montanari, I. (2001). Modernization, globalization and

(Eds), From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology. New L ib

the welfare state: a comparative analysis of old and

York: Oxford University Press. rar

new convergence of social insurance since 1930.

Wood, A. (1994). North-South Trade, Employment, and y on

British Journal of Sociology, 52, 469–494.

Inequality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. D ecem

Pritchett, L. (1997). Divergence, big time. Journal of

Economic Perspectives, 11, 3–17. Author’s Address b er

Raab, M., Ruland, M., Scho¨nberger, B., Blossfeld, H.- 1 5

P. et al. (2008). GlobalIndex – A sociological , 2

Department of Sociology/ICS, Faculty of Behavioural 0 approach to globalization measurement. 1 4

and Social Sciences, University of Groningen,

International Sociology, 24, 599–634.

Grote Rozenstraat 31, 9712 TG, Groningen, The

Ravallion, M. (2003). The debate on globalization,

Netherlands. Email: m.c.mills@rug.nl

poverty and inequality: why measurement matters.