Preview text:

58 PARTT\NO SHIP TYPES, SHIPPING ORGANISATIONS AND DOCUMENTATION

4 Ships and Specifications

It is estimated that almost 90% of all global trade today is transported by sea.

It is therefore fundamentally important that a logistics service provider must

have a complete knowledge and understanding of the various types of vessels

available in the freight market, the different functions of each type of vessel,

and how they are operated. Registration of a ship

Just as cars need to be registered before they are allowed on the road, so too do ships

need to be officially registered. Each vessel is given a unique code, which is used for

radio communications and as identification on all documentation. Ships do not have

to be registered in the country that they are built or based in, so owners are likely to

register their vessels in those countries that offer the best financial benefits - lower tax

rates or tax-free status - which add up to substantial cost reductions.

A complete list of calling codes of every vessel around the world is kept on a central

record at Lloyd's Register of Shipping in London, along with records of their movements and last reported position.

One of the most important documents on board any vessel is the logbook. Officers must

keep a daily record of each and every event that takes place on board the ship. Typical

entries would include the ship's current position, the ship's course, all ports of call,

weather conditions, and any other special e

vents, such as the handling of claims.

PART 2 Iii Ships and Specifications 5 9

Classification of ships

Every four years (although one year's grace is normally given), the class certificate for

a particular ship expires. It is immobilised for several days, while a series of extensive

checks are conducted by a classification society to ensure that the vessel is in satisfactory

condition to be carrying its cargo and crew. If the ship meets the requirements, it is re

classified according to the standard of its construction and on-board equipment.

T his process not only deems a ship seaworthy, but also determines the cost of insurance

for both the ship and the cargo it carries - a ship with a higher classification fetches a

lower insurance premium than one with a lower classification; it is therefore advantageous

for owners to maintain their ships to the highest standard.

Apart from these surveys to maintain classification, ships also undergo annual checks,

to make sure that the general condition of the ship, including its anchors and cables, is

satisfactory. A load-line survey is also done at the same time.

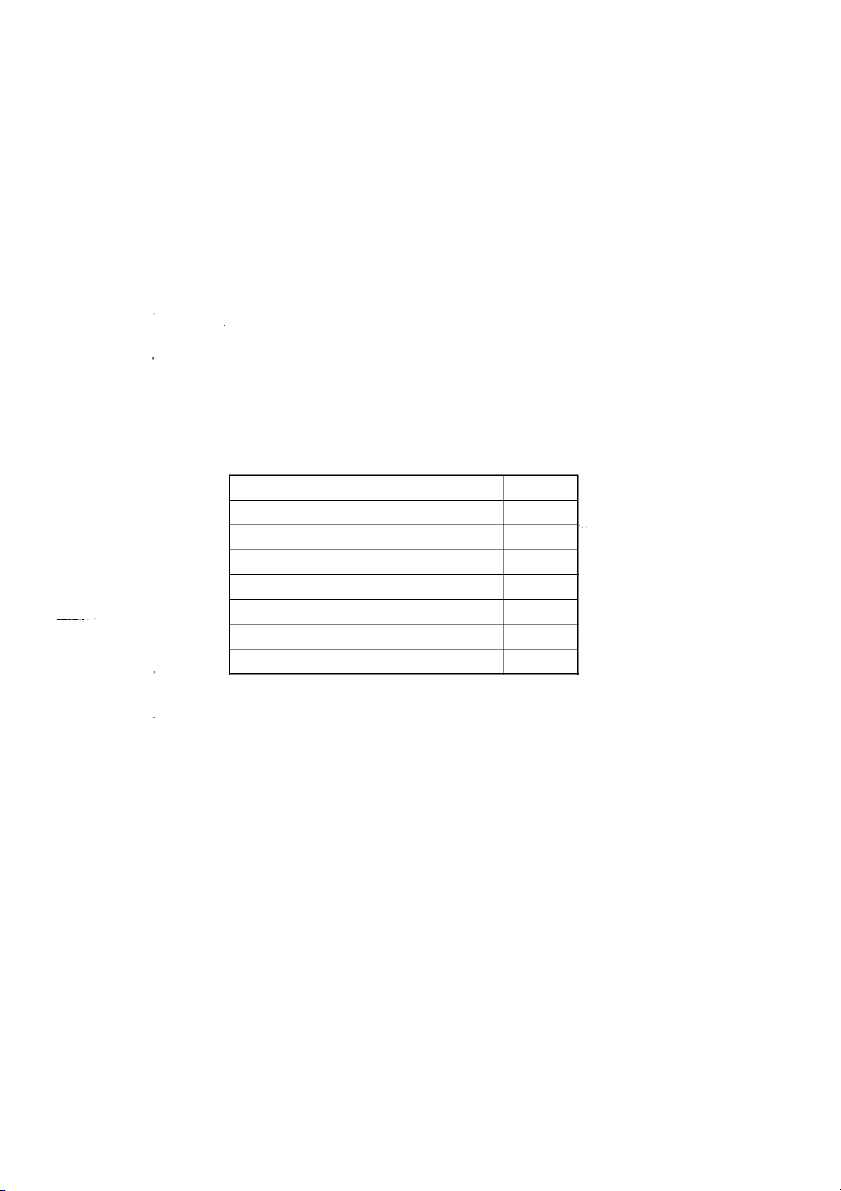

Some major international classification societies are: Company/Nationality Symbol

Lloyd's Register of Shipping, London/UK LR

American Bureau of Shipping, New York/USA AB Bureau Veritas, Paris/France BV

Germanischer Lloyd, Berlin/Germany GL Det Norske Veritas/Norway NV Nippon Kaiji Kyokai/Japan NK Registro Italian Navale/ltaly RL The Plimsoll Mark

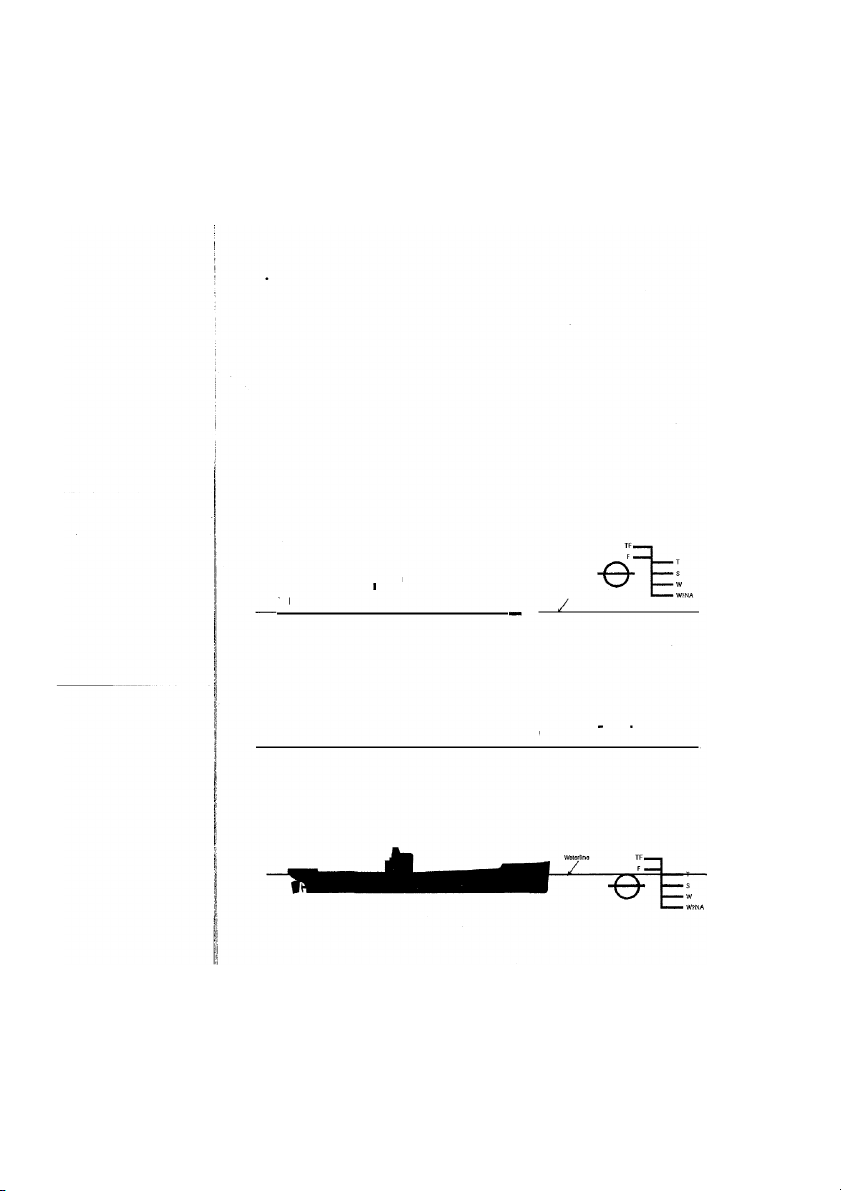

In 1836, public concern grew over the number of ships and crew lost at sea. The British

Parliament appointed a committee to investigate, and legislation was passed in 1850 to

create the Marine Department of t

he Board of Trade. Its role was to enforce the application

of laws governing manning, crew competence, and operation of merchant vessels. In 1870,

Samuel Plimsoll, a merchant and shipping reformer, created a safety limit: a "load-line".

In the Merchant Shipping Act of 1875, this line (known as the Plimsoll Mark) became

an internationally accepted reference to limit the weight of cargo loaded aboard ships.

How low a boat is able to safely sit in the water can be measured by its draught, which

is the vertical distance from the bottom of the keel to the waterline. 6 O

Guides to International Logistics l !l Seafreight Forwarding

Some factors for determining the Plimsoll Mark include: structural strength; • compartmentalisation; • deck height; • transverse stability; • hull form; • length of the ship; • type of vessel; • cargo on board; and • season and zone.

In addition to having this line permanently marked on both sides of the hull, each

vessel must carry a load line certificate, issued by a classification society, stipulating the

distances and draughts required for that particular vessel. ---- --- Waterline -, ----IIL-- ..., ·

Laying empty with little or no ballast _e_�y _ ___ �1----""-'-line �,,,.,,,....IM

Loaded to legal limits for sea conditions expected in the

North Atlantic in winter - plenty of reserved buoyancy Loaded deep for tropical seas

PART 2 Ill Ships and Specifications 6 1

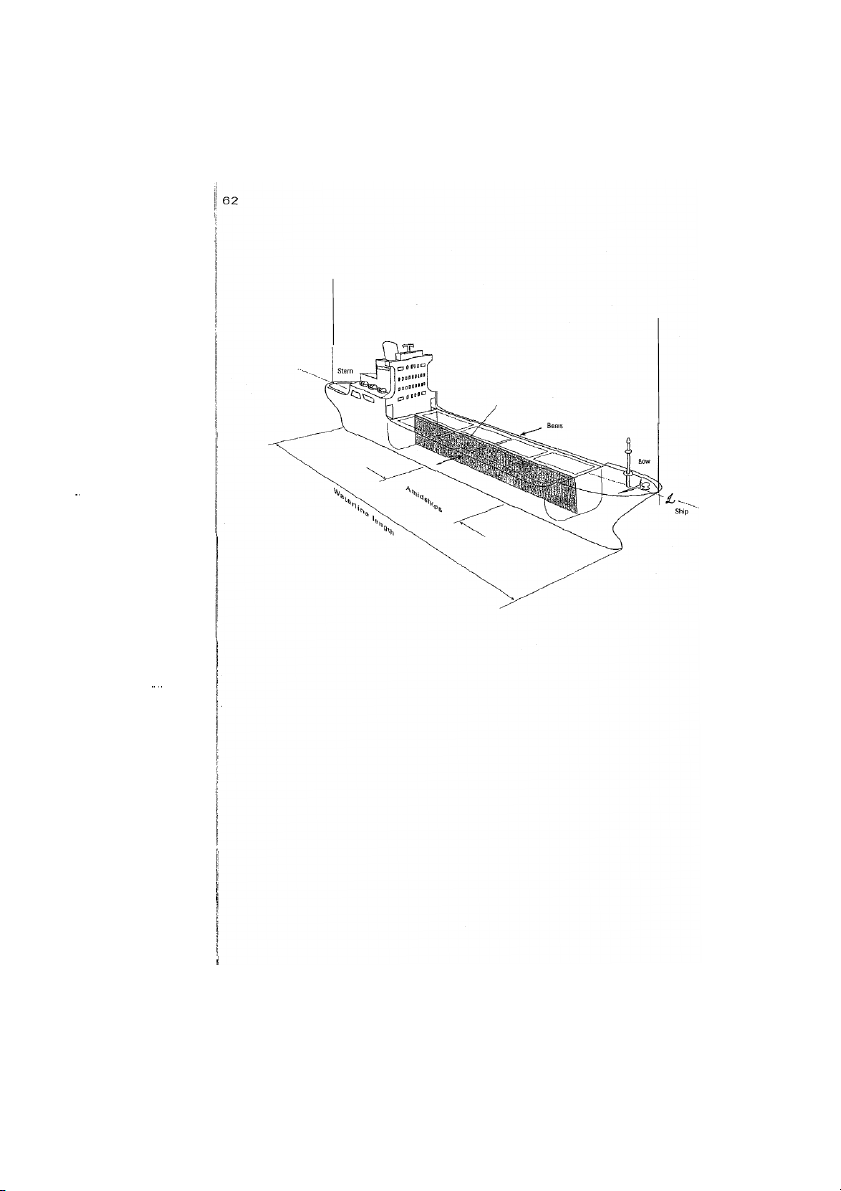

The profile of a ship and commonly used terms Length Overall (LOA)

The greatest length of the ship, from fore to aft. This length is important when docking the vessel. Beam

The greatest breadth of the ship, from port to starboard. Draught

The distance from the bottom of the keel to the waterline. Freeboard

The distance from the waterline to the top of the deck plating at the side of the deck amidships. Displacement

The weight of the ship and all that it contains - cargo, fuel, water, stores, crew and

effects. A ship can have different displacements at different draughts. Lightweight

The weight of a ship when empty of stores, fuel, water, crew or their effects. Deadweight (DWTI

The difference between the displacement and the lightweight.

The Gr oss Register Tonne (GRTI

The total cubic measurements of the ship (including engine room, bunker tanks for fuel

and water, seamen's accommodation). The Net Register Tonne (N RTI

The NRT is the available cubic capacity for cargo.

1 register tonne = 100 ft3 (2.8316 m3)

The register tonne is a cubic measure and not a weight indication. Other descriptions of

the ship's cubic capacity are grain (its capacity to hold bulk cargo) and bale (its capacity to hold packed cargo).

Guides to International Logistics m Seafreight Forwarding

------ L-------- enoth overall �fl ------------- ------- ---_ � --- � Centertine bulkhead Profile of a ship Speed and how to calculate it

A ship's speed is measured in knots, which can be expressed in nautical miles per hour.

1 nautical mile = l' (minute) of the earth's surface at the equator = 1,852 m.

Since 1 ° = 60', 1 ° = 60 nautical miles. By formula:

Speed (knots)= Distance (nautical miles)-+- Time (hours)

Therefore, if the distance and time travelled are known, then the ship's speed can be

calculated. Likewise, if the speed and the distance between two ports are known, then

the transit time can be calculated.

PART 2 Iii Ships and Specifications 6 3

The term "knot" originates from the time of the sailing ship, when a rope tied with knots

at regular intervals of 48 feet (8 fathoms) was thrown into the sea behind the ship in

order to find its speed. The number of knots that passed through the hand of the seaman

holding the rope per 28 seconds, as measured by an hourglass, told roughly how fast the ship was going. Types of ships Liner vessel

Liner vessels work to a fixed schedule;

they sail on specific dates between

predetermined groups of ports, irrespective

of whether they have a full load of cargo.

It is imperative that these vessels keep

to their sailing schedule, to maintain the

reputation of the shipping company that

owns them. A majority of container ship

owners today operate liner services on

most of the world trading routes. However,

some conventional or break bulk vessels

also still operate liner services in certain parts of the world where the nature and the

volume of cargo and the port conditions warrant the use of such vessels. Tramp vessel Tramp vessels sail only when

there is a sufficient quantity of cargo on board; they do

not operate on a fixed sailing schedu le. These vessels

generally carry cargo in bulk, such as coal, grain, timber,

sugar, ore, fertiliser, cement clinker, copra, bauxite and phosphates. As many of these types of cargo are seasonal, it would only be viable to transport them a shipload at a time. Many tramp vessel operators work on a much

smaller scale than their liner counterparts, and must therefore have an intimate knowledge

of market conditions and their business demands.

Guides to International Logistics l!il Seafreight Foiwarding 64 11 Container ship

A container ship is especially constructed and fitted to handle and transport containerised

cargo. Most container ships have no loading gear, so the containers are handled and

loaded by large gantry quay cranes while the ships are in the ports.

The conr:ept of using containers in the transport industry was introduced inl 956 by an

American trucker called Malcolm McLean. He initiated "container traffic" as it is known

today, moving cargo between the US coasts via the Panama Canal. In doing so, he began

competing with other truckers and railways. Since its beginning, containerisation has

grown into a massive business and it is today the main mode of sea transport arou_nd

the world. To accommodate the increasing amount of cargo being moved on a daily

PART 2 l!i Ships and Specifications 6!:

basis and the growing demand for shorter delivery times, container ships have grown

to a carrying capacity of 8,000 TE Us. In this industry, it is important to be able to predict

supply and demand; the next generation of 10,000-TEU vessels are already in the order

books of some shipyards and will be in service from 2007.

Conventional or break bulk ship

Break bulk ships are characterised by large open hatches, and are fitted with boom

and-winch gears or deck cranes. Loading and unloading of these ships is done by

either the port's shore cranes or by the ship's derricks - shipside operations are carried

out manually by stevedores. As much manpower is needed to facilitate the running of

break bulk ships, they are now primarily used at ports where labour is cheap. These

ports lack modern facilities or inland rail/highway connections, which are required to

support efficient container ship operations. Although break bulk ships were extensively

used up until the middle of the 1960s, they are no longer commercially viable, and fewer

of these ships are being built each year. RO/RO (Roll On/Roll Off) ship

RO/RO ships are designed to carry automobiles and heavy trucks as their primary cargo.

These vehicles are driven or towed on and off the ship, using either the ship's own ramps

or shore-based ramps: thus the name Roll On/Roll Off.

These ships can also load break bulk goods, heavy cargo and containers, but because

they are not designed specifically to accommodate cargo which can be stacked in a

uniform manner, the space below decks cannot be utilised as efficiently as on a container

ship. This other cargo is loaded onto a low-bed trailer and trucked over a ramp into the ship's hold. LASH ship

The Lighter Aboard Ship (LASH) was introduced in 1969. It is a single-decked vessel

with large hatches, wing tank arrangements, and clear access to the stern.

LASH barges are deployed to smaller

ports to collect and drop off cargo, after

which they are towed to a marshalling

point out at sea, and subsequently loaded

onto the LASH ship. A typical lash barge

has dimensions 18.75m x 9.5m x 3.96m,

cubic capacity of 555m3 and an average deadweight of 385 tonnes. 6 6

Guides to International Logistics II! Seafreight Forwarding

A LASH ship has the capacity for 64-89 barges. They are used to transport large amounts

of inexpensive cargo, and operate in regions with extensive inland waterways and shallow

ports. As on-board cranes are used to hoist the barges off and lower them into the water,

no special docks or terminals are required. Bulk carrier

Bulk carriers are normally tramp vessels which are chartered for a single voyage, or for

transporting seasonal cargo such as grain, ore and coal. These vessels resemble tankers,

but have no loading gears and can vary in size. Some of the biggest bulk carriers are

about 75,000 DWT, or Panamax - the term used to d

escribe the maximum size of a vessel

that can pass through the Panama Canal. Oil tanker

Oil tankers are the largest of all ocean-going transport vessels, with sizes varying from

50,000 DWT to 360,000 DWT. There are two categories of these super tankers: the VLCCs

(Very Large Crude Carriers), with a size of 280,000 DWT, and the ULCCs (Ultra Large

Crude Carriers), with a size of 360,000 DWT and above. 6 7

PART 2 IS! Ships and Specifications

When the Suez Canal was temporarily closed in 1976, these tankers were forced to take

a much longer journey around the Cape of Good Hope, which had a direct bearing on

costs and delivery times. Tanker tonnage therefore had to increase to over 360, 000 DWT.

drawing over 20 metres draught, to meet market demands.

However, the use of the ULCC has diminished due to several factors. Recent oil spills

and the resultant damage to the environment has made them a potential hazard. They

are also extremely costly to maintain, and the discovery of new sources of oil that are

geographically closer to importing countries means that it is no longer necessary or

financially viable to transport oil using such large vessels. LNG/LPG tanker

LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas) and LPG (Liquefied Petroleum Gas) tankers are used solely

for the transportation of liquefied gas and are therefore specially constructed to·carry

them in special pressurised tanks. Most contracts for LNG tankers are taken out on a COA

(Contract of Affreightment) basis, and they are therefore chartered out long-term.