Preview text:

27 Current and Resistance 27.1 Electric Current 27.2 Resistance 27.3

A Model for Electrical Conduction 27.4 Resistance and Temperature 27.5 Superconductors 27.6 Electrical Power

* An asterisk indicates a question or problem new to this edition. OQ27.1

Answer (d). One ampere–hour is (1 C/s)(3 600 s) = 3 600 coulombs.

The ampere–hour rating is the quantity of charge that the battery can

lift though its nominal potential difference. OQ27.2 (i) Answer (e). We require = 3 / Then = 1/3. (ii) Answer (d). 2/ 2 = 1/3 gives / = 1/ 3 . OQ27.3

The ranking is c > a > b > d > e. Because (a)

/ , so the current becomes 3 times larger. (b) 2

, so the current is 3 times larger. (c)

is 1/4 as large, so the current is 4 times larger. (d)

is 2 times larger, so the current is 1/2 as large. (e)

increases by a small percentage, so the current has a small decrease. OQ27.4 (i)

Answer (a). The cross-sectional area decreases, so the current

density increases, thus the drift speed must increase.

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part. Chapter 27

(ii) Answer (a). The cross-sectional area decreases, so the resistance

per unit length, / = / , increases. OQ27.5 Answer (c). / 1.00 V /10.0 0.100 A 0.100 C/s. Because current is constant, / / , and we find that 0.100 C/s 20.0 s 2.00 C OQ27.6

Answer (c). The resistances are: 2 , 1 2 2 1 4 2 , 2 3 2 2 / 9 2 . 2 3 OQ27.7

Answer (a). The new cross-sectional area is three times the original. 3 Originally, . Finally, . 3 9 9 OQ27.8

Answer (b). Using = 10.0 at = 20.0 °C, we have 0 1 or 0 1 10.6 10.0 1 0 8.57 10 4 C 1 90.0 C 20.0 C At = –20.0°C, we have 0 1 10.0 1 8.57 10 4 C 1 20.0 C 20.0 C 9.66 OQ27.9 Answer (a). = = 2 V/2 A = 1 . OQ27.10

Answer (c). Compare resistances: ( / 2)2 2 2 2 2 1 ( / 2)2 2 2 2 4 2 2 Compare powers: 2 . 2 2 OQ27.11 Answer (e). 2 . Therefore, 2 1 2 2 OQ27.12 (i)

Answer (a). = ∆ 2/ , and ∆ is the same for both bulbs, so the

25 W bulb must have higher resistance so that it will have lower power.

(ii) Answer (b). ∆ is the same for both bulbs, so the 100 W bulb

must have lower resistance so that it will have more current.

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part.

Current and Resistance OQ27.13

Answer (d). Because wire B has twice the radius, it has four times the

cross-sectional area of wire A. For wire A, = = . For wire B, = ( ) ( ) = (1/2) / = 2. CQ27.1

Choose the voltage of the power supply you will use to drive the 2

heater. Next calculate the required resistance as . Knowing

the resistivity of the material, choose a combination of wire length

and cross-sectional area to make . You will have to pay

for less material if you make both and smaller, but if you go too

far the wire will have too little surface area to radiate away the

energy; then the resistor will melt. CQ27.2

Geometry and resistivity. In turn, the resistivity of the material depends on the temperature. CQ27.3

The conductor does not follow Ohm’s law, and must have a

resistivity that is current-dependent, or more likely temperature- dependent. CQ27.4

In a normal metal, suppose that we could proceed to a limit of zero

resistance by lengthening the average time between collisions. The

classical model of conduction then suggests that a constant applied

voltage would cause constant acceleration of the free electrons. The

drift speed and the current would increase steadily in time.

It is not the situation envisioned in the question, but we can actually

switch to zero resistance by substituting a superconducting wire for

the normal metal. In this case, the drift velocity of electrons is

established by vibrations of atoms in the crystal lattice; the maximum

current is limited; and it becomes impossible to establish a potential

difference across the superconductor. CQ27.5 The resistance of copper with temperature, while the resistance of silicon

with increasing temperature. The

conduction electrons are scattered more by vibrating atoms when

copper heats up. Silicon’s charge carrier density increases as

temperature increases and more atomic electrons are promoted to become conduction electrons. CQ27.6

The amplitude of atomic vibrations increases with temperature.

Atoms can then scatter electrons more efficiently.

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part. Chapter 27 CQ27.7

Because there are so many electrons in a conductor (approximately

1028 electrons/m3) the average velocity of charges is very slow. When

you connect a wire to a potential difference, you establish an electric

field everywhere in the wire nearly instantaneously, to make

electrons start drifting everywhere all at once. CQ27.8

Voltage is a measure of potential difference, not of current. “Surge”

implies a flow—and only charge, in coulombs, can flow through a

system. It would also be correct to say that the victim carried a certain current, in amperes. Section 21.1 Electric Current *P27.1

The drift speed of electrons in the line is 2 / 4

The time to travel the 200-km length of the line is then 2 4

Substituting numerical values,

200 10 3 m 8.50 1028 m 3 1.60 10 19 C 0.02 m 2 4 1 000 A 1 yr 8.55 108 s 27.1 yr 3.156 107 s 2 *P27.2

The period of revolution for the sphere is , and the average

current represented by this revolving charge is . 2 P27.3 We use =

, where is the number of charge carriers per unit

volume, and is identical to the number of atoms per unit volume. We

assume a contribution of 1 free electron per atom in the relationship

above. For aluminum, which has a molar mass of 27, we know that Avogadro’s number of atoms,

, has a mass of 27.0 g. Thus, the mass per atom is 27.0 g 27.0 g 4.49 10 23 g atom 6.02 1023

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part.

Current and Resistance Thus, density of aluminum 2.70 g cm 3 mass per atom 4.49 10 23 g atom

6.02 1022 atoms cm 3 6.02 10 28 atoms m 3 Therefore, 5.00 A

6.02 1028 m 3 1.60 10 19 C 4.00 10 6 m 2 1.30 10 4 m s or, 0.130 mm s . P27.4

The period of the electron in its orbit is = 2 / , and the current

represented by the orbiting electron is 2 2.19 106 m s 1.60 10 19 C 2 5.29 10 11 m 1.05 10 3 C s 1.05 mA P27.5

If is the number of protons, each with charge , that hit the target in

time ∆ , the average current in the beam is / / , giving 125 10 6 C/s 23.0 s 1.80 10 16 protons 1.60 10 19 C/proton P27.6

(a) From Example 27.1 in the textbook, the density of charge carriers

(electrons) in a copper wire is = 8.46 × 1028 electrons/m3. With 2 and

, the drift speed of electrons in this wire is 2 3.70 C s 2 8.46 1028 m 3 1.60 10 19 C 1.25 10 3 m 5.57 10 5 m s

(b) The drift speed is smaller because more electrons are being

conducted. To create the same current, therefore, the drift speed need not be as great.

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part. Chapter 27 P27.7 From , we have =

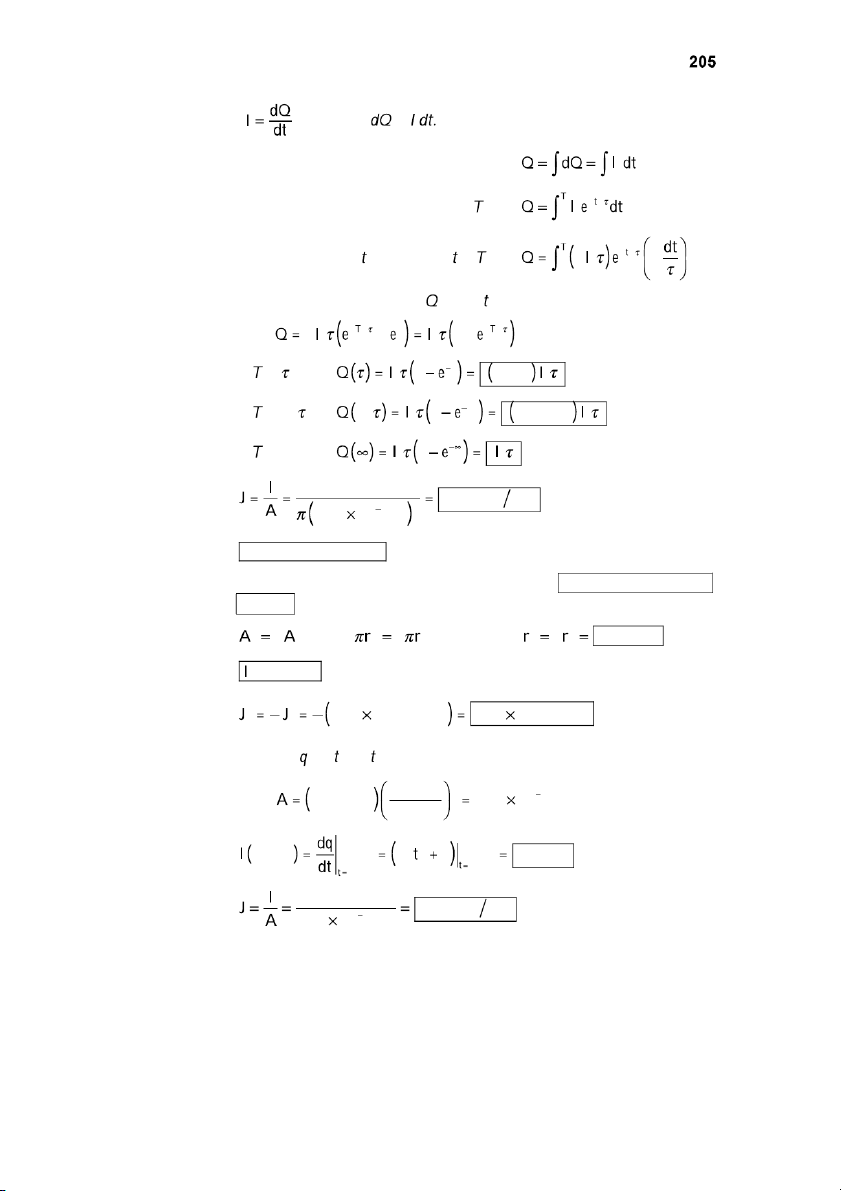

From this, we derive the general integral:

In all three cases, define an end-time, : – / 0 0

Integrating from time = 0 to time = : – – / – 0 0

We perform the integral and set = 0 at = 0 to obtain – – / 0 – 1 – – / 0 0 (a) If = : 1 1 0.632 0 0 (b) If = 10 : 10 1 10 0.999 95 0 0 (c) If = ∞: 1 0 0 5.00 A P27.8 (a) 99.5 kA m2 2 4.00 10 3 m (b) Current is the same.

(c) The cross-sectional area is greater; therefore the current density is smaller. (d) 4 or 2 4 2 so 2 0.800 cm . 2 1 2 1 2 1 (e) = 5.00 A 1 1 (f) 9.95 104 A/m2 2.49 104 A/m2 2 4 1 4 P27.9

We are given = 4 3 + 5 + 6. The area is 2 2.00 cm2 1.00 m 2.00 10 4 m2 100 cm (a) 1.00 s 12 2 5 17.0 A 1.00 s 1.00 s 17.0 A (b) 85.0 kA m2 2.00 10 4 m 2

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part.

Current and Resistance 1 P27.10

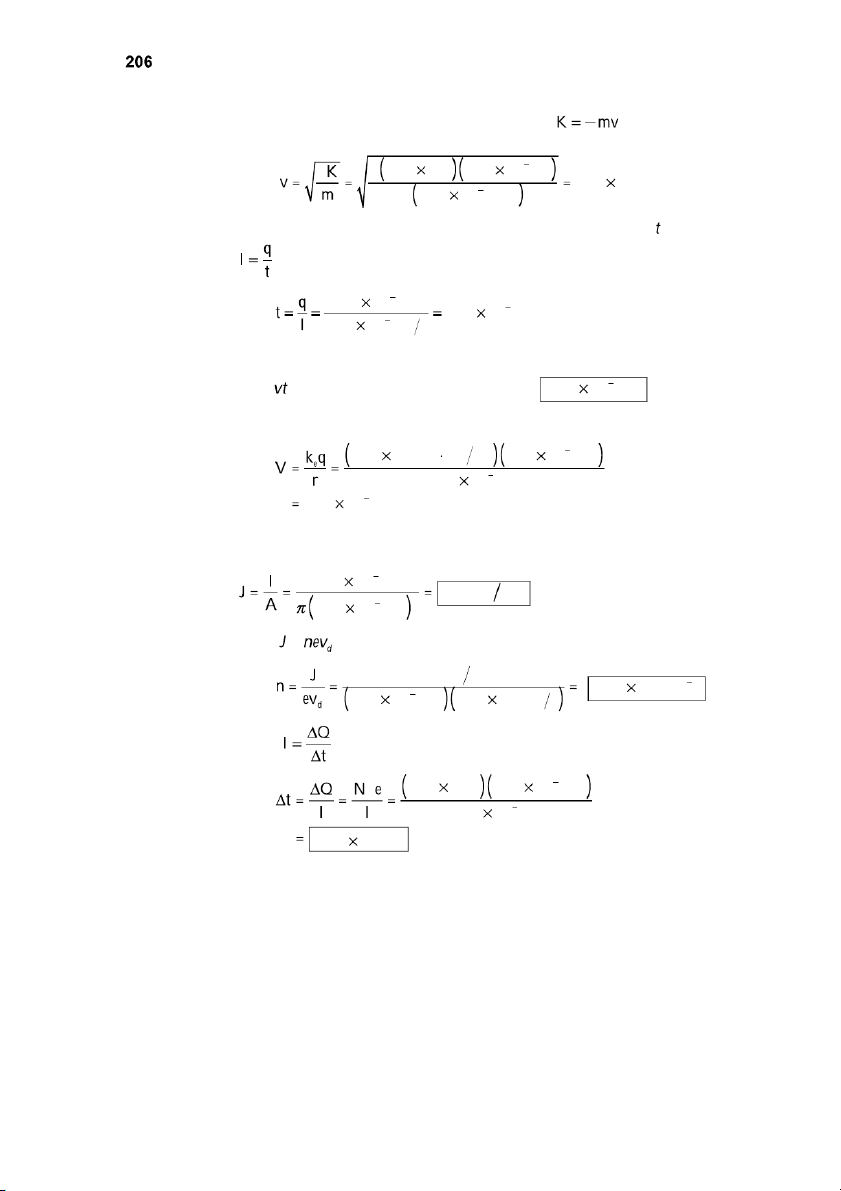

(a) We obtain the speed of each deuteron from 2 : 2 2 2 2.00 10 6 1.60 10 19 J 1.38 107 m/s 2 1.67 10 27 kg

The time between deuterons passing a stationary point is in , so 1.60 10 19 C 1.60 10 14 s 10.0 10 6 C s

So the distance between individual deuterons is

= (1.38 × 107 m/s)(1.60 × 10–14 s) = 2.21 10 7 m

(b) One nucleus will put its nearest neighbor at potential 8.99 109 N m2 C2 1.60 10 19 C 2.21 10 7 m 6.49 10 3 V

This is very small compared to the 2 MV accelerating potential, so

repulsion within the beam is a small effect. 8.00 10 6 A P27.11 (a) 2.55 A m2 2 1.00 10 3 m (b) From = , we have 2.55 A m2 5.31 1010 m 3 1.60 10 19 C 3.00 108 m s (c) From , we have 6.02 10 23 1.60 10 19 C A 8.00 10 6 A 1.20 1010 s (This is about 382 years!)

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part. Chapter 27 P27.12

To find the total charge passing a point in a given amount of time, we use , from which we can write 1 240 s 120 100 A sin 0 s 100 C 100 C cos cos 0 0.265 C 120 2 120 P27.13

The molar mass of silver = 107.9 g/mole and the volume is area thickness 700 10 4 m 2 0.133 10 3 m 9.31 10 6 m3

The mass of silver deposited is 10.5 103 kg m3 9.31 10 6 m3 Ag 9.78 10 2 kg

And the number of silver atoms deposited is 6.02 1023 atoms 1 000 g 9.78 10 2 kg 107.9 g 1 kg 5.45 1023 atoms The current is then 12.0 V 6.67 A 6.67 C s 1.80

The time interval required for the silver coating is 5.45 10 23 1.60 10 19 C 6.67 C s 1.31 104 s 3.64 h Section 27.2 Resistance P27.14 From Equation 27.7, we obtain 120 V 0.500 A 500 mA 240

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part.

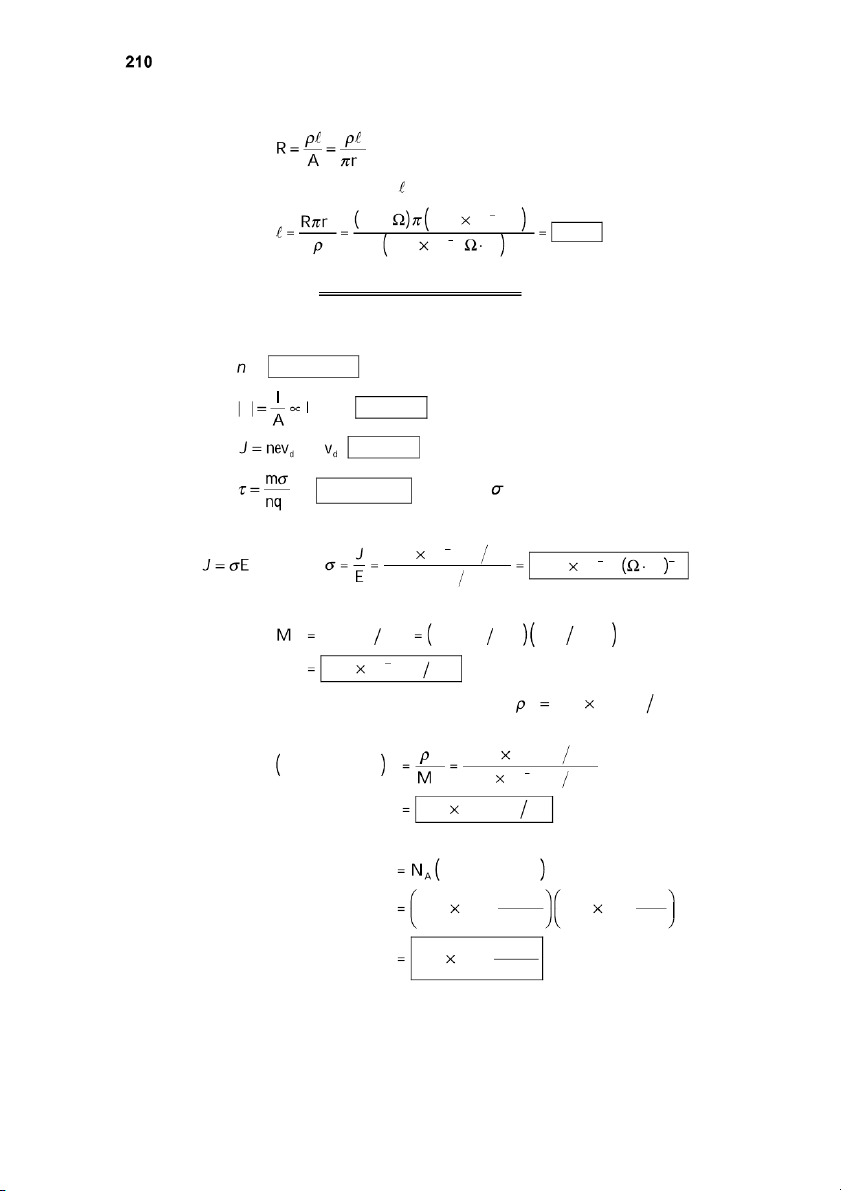

Current and Resistance *P27.15 From Ohm’s law, / , and from Equation 27.10, / / 2 /4

Solving for the resistivity gives 2 2 2.00 10 3 m 2 9.11 V 4 4 4 50.0 m 36.0 A 1.59 10 8 m

Then, from Table 27.2, we see that the wire is made of silver . P27.16 and . The area is 1.00 m 2 0.600 mm 2 6.00 10 7 m2 1 000 mm

From the potential difference, we can solve for the current, which gives 0.900 V 6.00 10 7 m 2 5.60 10 8 m 1.50 m 6.43 A P27.17

From the definition of resistance, 120 V 8.89 13.5 A P27.18 Using

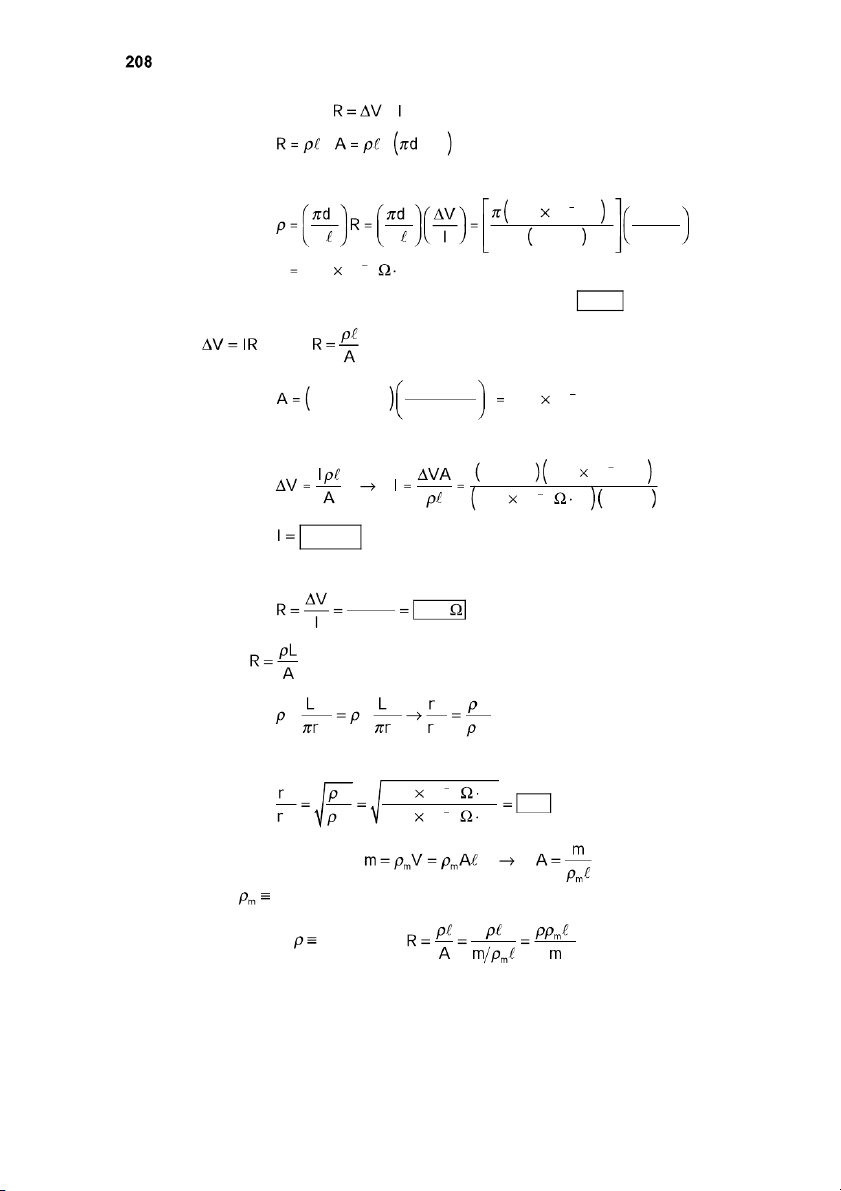

and data from Table 27.2, we have 2 Cu Al Al Al Cu 2 Al 2 2 Cu Al Cu Cu which yields 2.82 10 8 m Al Al 1.29 1.70 10 8 m Cu Cu P27.19 (a) Given total mass , where mass density. 2 Taking resistivity, .

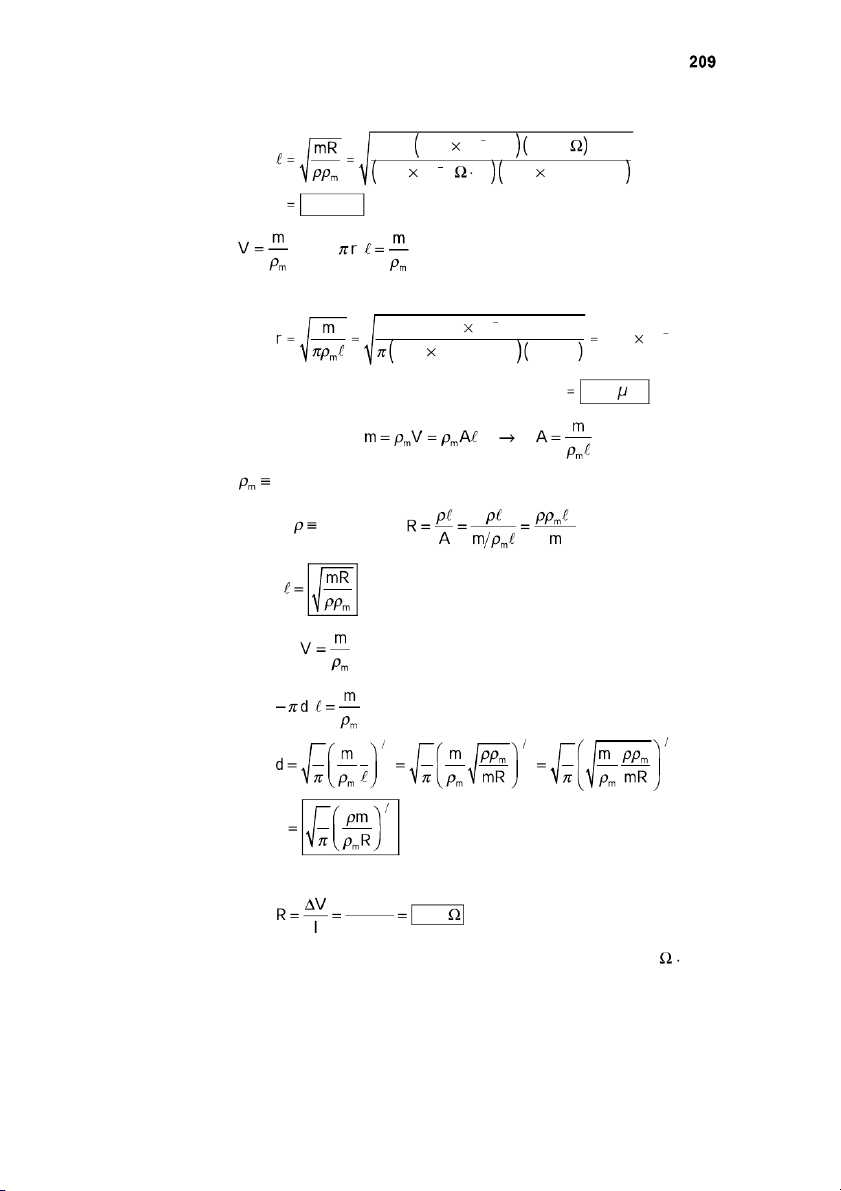

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part. Chapter 27 Thus, 1.00 10 3 kg 0.500 1.70 10 8 m 8.92 10 3 kg/m 3 1.82 m (b) , or 2 Thus, 1.00 10 3 kg 1.40 10 4 m 8.92 103 kg/m 3 1.82 m

The diameter is twice this distance: diameter 280 m P27.20 (a) Given total mass , where mass density. 2 Taking resistivity, . Thus, . (b) Volume , or 1 2 4 1 2 1 2 1 2 4 1 4 4 2 2 1 4 4 P27.21

(a) From the definition of resistance, 120 V 13.0 9.25 A

(b) The resistivity of Nichrome (from Table 27.2) is 1.50 × 10–6 m.

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part.

Current and Resistance

We find the length of wire from 2 solving for the length gives 2 2 13.0 2.50 10 3 m 170 m 1.50 10 6 m Section 27.3

A Model for Electrical Conduction *P27.22 (a) is unaffected. (b) J so it doubles . (c) so doubles. (d) is unchanged

as long as does not change due to a 2

temperature change in the conductor. 6.00 10 13 A m2 *P27.23 so 6.00 10 15 m 1 . 100 V m P27.24

(a) From Appendix C, the molar mass of iron is 55.85 g mol 55.85 g mol 1 kg 10 3 g Fe 5.58 10 2 kg mol

(b) From Table 14.1, the density of iron is 7.86 103 kg m 3 , so Fe the molar density is 7.86 103 kg m3 molar density Fe Fe 5.58 10 2 kg mol Fe 1.41 105 mol m3

(c) The density of iron atoms is density of atoms molar density atoms mol 6.02 1023 1.41 105 mol m3 atoms 8.49 1028 m3

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part. Chapter 27

(d) With two conduction electrons per iron atom, the density of charge carriers is

charge carriers atom density of atoms electrons atoms 2 8.49 10 28 atom m3 1.70 1029 electrons m 3

(e) With a current of = 30.0 A and cross-sectional area

= 5.00 × 10–6 m2, the drift speed of the conduction electrons in this wire is 30.0 C s

1.70 1029 m 3 1.60 10 19 C 5.00 10 6 m 3 2.21 10 4 m s P27.25

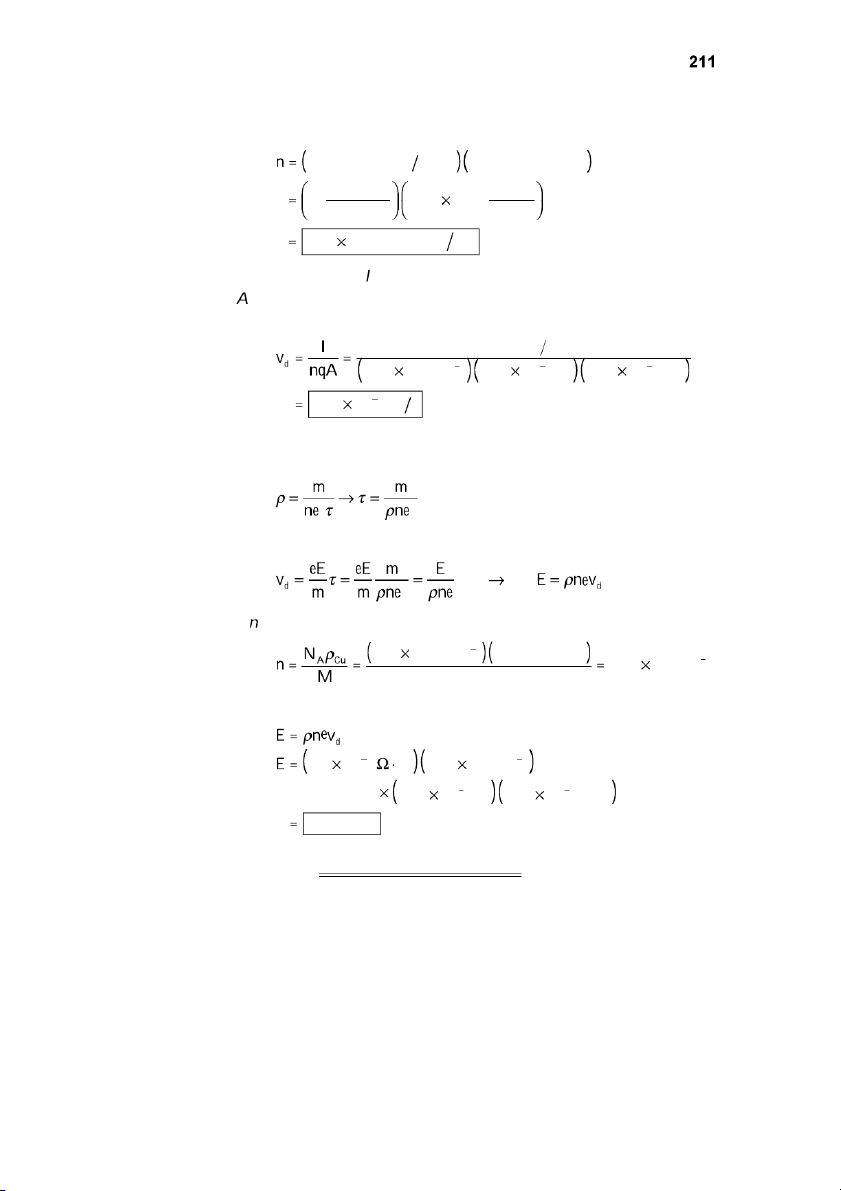

From Equations 27.16 and 27.13, the resistivity and drift velocity can be

related to the electric field within the copper wire: 2 2 and 2

where is the electron density. From Example 27.1,

6.0210 23 mol 1 8 920 kg/m3 8.46 10 28 m 3 0.063 5 kg/mol The electric field is then 1.7 10 8 m 8.46 1028 m 3 1.60 10 19 C 7.84 10 4 m/s 0.18 V/m

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part.

Current and Resistance Section 27.4 Resistance and Temperature P27.26 1 gives 0 140 19.0 1 4.50 10 3 C Solving, 1.42 103 C 20.0C And the final temperature is 1.44 103 C P27.27

If we ignore thermal expansion, the change in the material’s resistivity with temperature [1

] implies that the change in resistance 0 is

. The fractional change in resistance is defined by 0 0 = ( – )/ . Therefore, 0 0 0

5.00 10 3 °C 1 50.0°C 25.0°C 0.12 0

*P27.28 At the low temperature we write 1 0 0

where = 20.0°C. At the high temperature , 0 1 1 A 0 0 Then, 1.00 A 1 3.90 10 3 C 1 58.0 C 20.0 C 1 3.90 10 3 C 1 88.0 C 20.0 C 1.15 and 1.00 A 1.98 A . 0.579 P27.29

We use Equation 27.20 and refer to Table 27.2: 1 0 0 6.00 1 3.8 10 3 C 1 34.0 C 20.0 C 6.32 P27.30 (a) From =

/ , the initial resistance of the mercury is 9.58 10 7 m 1.000 0 m 1.22 2 4 2 1.00 10 3 m 4

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part. Chapter 27

(b) Since the volume of mercury is constant, gives

the final cross-sectional area as . Thus, the final 2 resistance is given by . The fractional change in the resistance is then 2 2 1 1 1 2 100.040 0 cm 1 8.00 10 4 increase 100.000 0 cm

*P27.31 (a) The resistance at 20.0°C is 1.7 10 8 m 34.5 m 0 2.99 0.25 10 3 m 2 and the current is 9.00 V 3.01 A 0 3.00

(b) At 30.0°C, from Equation 27.20, 1 0 2.99 1 3.9 10 3 C 1 30.0 C 20.0 C 3.10 The current is then 9.00 V 2.90 A 3.10 0 P27.32

(a) We require two conditions: 1 1 2 2 [1] 2 2

where carbon = 1 and Nichrome = 2, and for any 1 1 1 2 2 1 [2] 2 1 2 2

Setting equations [1] and [2] equal to each other, we have 1 1 2 2 1 1 1 2 2 1 2 2 2 1 2 2

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part.

Current and Resistance simplifying, 11 2 2 11 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 2 2 2 or 2 2 11 , which gives 2 2 2 1 [3] 2 2 2 1 1 1

The two equations [1] and [3] are just sufficient to determine 1 and . The design goal can be met. 2 (b) From Table 27.2, 0.5 10 3 C 1 and 0.4 10 3 C 1 . 1 2 Use equation [3] to solve for in terms of : 2 1 1 1 2 1 2 2

then substitute this into equation [1]: 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 1 2 1 2 2 2 3.5 10 5 m 0.5 10 3 10.0 1 (1.50 10 3m)2 0.4 10 3 1 0.898 m 1 and so 3.5 10 5 m 0.5 10 3 1 1 2 1 0.4 10 3 1 26.2 m 2 2 1.50 10 6 m Therefore, 0.898 m and 26.2 m. 1 2 P27.33

(a) The resistivity is computed from 1 – : 0 0 2.82 10–8 m 1 3.90 10–3 °C–1 30.0°C 3.15 10–8 m (b) The current density is 0.200 V/m 1 A J 3.15 10 –8 m V 6.35 106 A/m2

(c) The current density is related to the current by . 2 2 2 6.35 106 A/m 2 5.00 10 5 m 49.9 mA

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part. Chapter 27

(d) The mass density gives the number-density of free electrons; we

assume that each atom donates one conduction electron: 2.70 103kg 1 mol 103g 6.02 1023freee m3 26.98 g kg 1 mol 6.02 10 28 e/m 3 Now = gives the drift speed as 6.35 106 A/m 2

6.02 10 28 e–/m 3 –1.60 10–19 C/e– 6.59 10 4 m/s

The sign indicates that the electrons drift opposite to the field and current. (e) The applied voltage is 0.200 V/m 2.00 m 0.400 V . P27.34 For aluminum, 3.90 10 3 C 1 (Table 27.2) and 24.0 10 6 C 1 (Table 19.1) The resistance is then 1 1 1 0 1 2 0 1 1 3.90 10 3 C 1 120 C 20.0 C 1.23 1 24.0 10 6 C 1 120 C 20.0 C 1.71 P27.35

Room temperature is = 20.0°. From Equation 27.19, 0 1 3 Al 0Al Al 0 0 Cu

Then, substituting numerical values from Table 27.2 gives 1 3 0 Cu 1 0 Al 0 Al 1 3 1.7 10 8 m 1 3.9 10 3 C 1 2.82 10 8 m

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part.

Current and Resistance

and solving for the temperature gives 20.0 C 207 C 227 C

where we have assumed three significant figures throughout. Section 27.6 Electrical Power *P27.36 (a) 300 103 J C 1.00 10 3 C s 3.00 108 W

A large electric generating station, fed by a trainload of coal each day, converts energy faster. (b) 2 2 1 370 W m2 (6.37 106 m) 2 1.75 1017 W

Terrestrial solar power is immense compared to lightning and

compared to all human energy conversions. *P27.37 0.800 1 500 hp 746 W hp 8.95 10 5 W Then, from , 8.95 105 W 448 A 2 000 V P27.38 From Equation 27.21, 500 10 6 A 15 103 V 7.50 W P27.39 (a) From Equation 27.21, 1.00 103 W 120 V 8.33 A (b) From Equation 27.23, 2 2 120 V 2 1.00 103 W 14.4 P27.40 From Equation 27.21, 0.200 10 3 A 75.0 10 3 V 15.0 10 6 W 15.0 W

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part. Chapter 27 P27.41 From Equation 27.21, 350 10 3 A 6.00 V 2.10 W P27.42

If the tank has good insulation, essentially all of the energy electrically

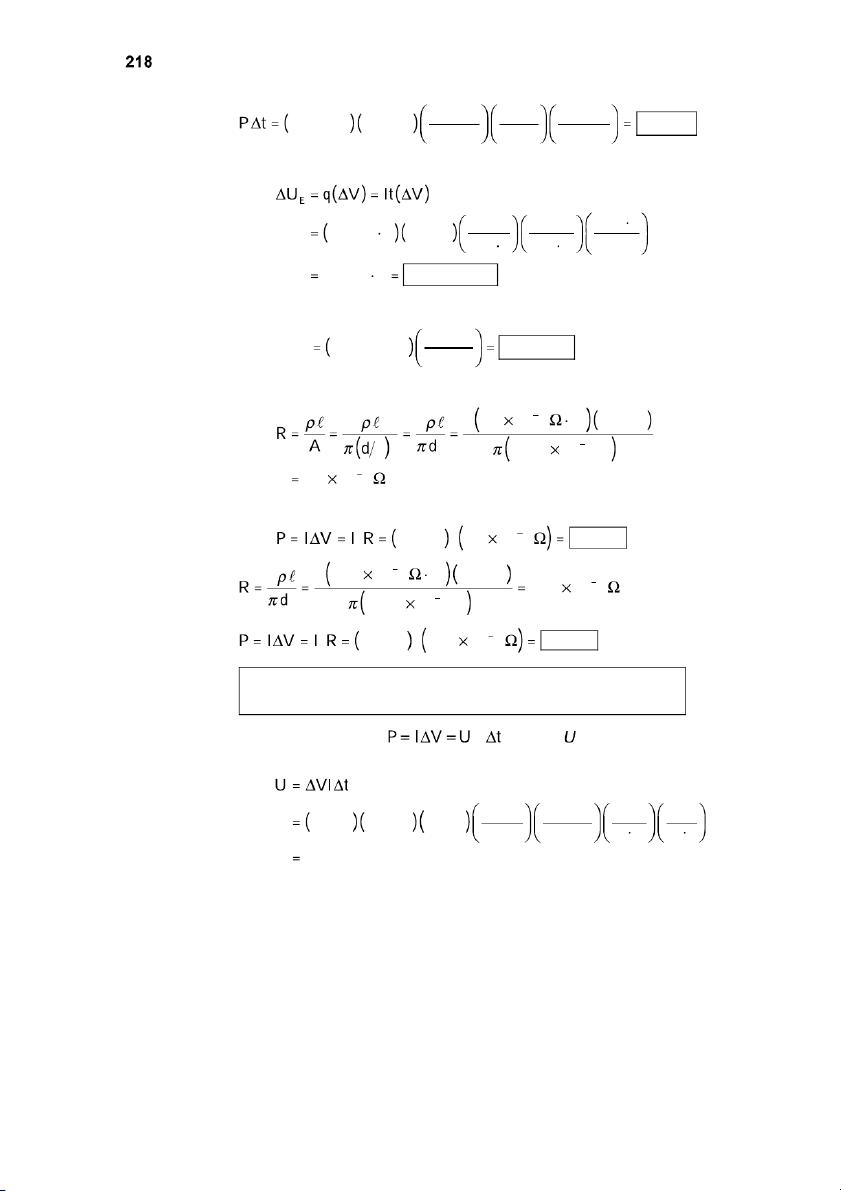

transmitted to the heating element becomes internal energy in the water: . internal electrical Our symbol represents the same (electrical) thing as the textbook’s

, namely electrically transmitted energy. ET Since and 2 / internal electrical where = 4 186 J/kg · °C the resistance is ( )2 240 V 2 1 500 s 6.53 4 186 J/kg °C 109 kg 29.0 C P27.43 From 2 /, we find that 2 (120 V)2 100 W 144 The final current is 140 V 0.972 A 144 The power during the surge is 2 140 V 2 136 V 144 So the percentage increase is 136 W – 100 W 100 W 0.361 36.1% P27.44

You pay the electric company for energy transferred in the amount . 7 d 24 h k 0.110 $ (a) 40 W 2 weeks 1 week 1 d 1 000 kWh $1.48 1 h k 0.110 $ (b) 970 W 3 min $0.005 34 60 min 1 000 kWh

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part.

Current and Resistance 1 h k 0.110 $ (c) 5 200 W 40 min $0.381 60 min 1 000 kWh P27.45

(a) The total energy stored in the battery is 1 C 1 J 1 W s 55.0 A h 12.0 V 1 A s 1 V C 1 J 660 W h 0.660 kWh

(b) The value of the electricity is $0.110 Cost 0.660 kWh $0.072 6 1 kWh P27.46

(a) The resistance of 1.00 m of 12-gauge copper wire is 4 4 1.7 10 8 m 1.00 m 2 2 2 0.205 10 2 m 2 5.2 10 3

The rate of internal energy production is 2 20.0 A 2 5.2 10 3 2.1 W 4 4 2.82 10 8 m 1.00 m (b) 8.54 10 3 2 0.205 10 2 m 2 2 20.0 A 2 8.54 10 3 3.42 W (c)

It would not be as safe. If surrounded by thermal insulation, it

would get much hotter than a copper wire. P27.47 The power of the lamp is / , where is the energy

transformed. Then the energy you buy, in standard units, is 24 h 3 600 s 1 J 1 C 110 V 1.70 A 1 day 1 day h V C A s 16.2 MJ

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part. Chapter 27

In kilowatt hours, the energy is 24 h 1 J 1 C W s 110 V 1.70 A 1 day 1 day V C A s J 4.49 kWh

So operating the lamp costs (4.49 kWh)($0.110/kWh) = $0.494 /day . P27.48

The energy taken in by electric transmission for the fluorescent bulb is 3 600 s 11 J s 100 h 3.96 10 6 J 1 h $0.110 k W s h cost 3.96 10 6 J $0.121 kWh 1 000 J 3 600 s For the incandescent bulb, 3 600 s 40 W 100 h 1.44 10 7 J 1 h $0.110 cost 1.44 10 7 J $0.440 3.6 106 J savings $0.440 $0.121 $0.319 P27.49

First, we compute the resistance of the wire: 1.50 10 6 m 25.0 m 298 2 0.200 10 3 m

The potential drop across the wire is then 0.500 A 298 149 V

(a) The magnitude of the electric field in the wire is 149 V 5.97 V m 25.0 m

(b) The power delivered to the wire is 149 V 0.500 A 74.6 W

(c) We use Equation 27.20 and Table 27.2: 0 1 0 298 1 0.400 10 3 C 320 C 337

© 2014 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part.