Preview text:

Willingness to Communicate in English:

A Microsystem Model in the Iranian EFL Classroom Context

GHOLAM HASSAN KHAJAVY, BEHZAD GHONSOOLY, AND AZAR HOSSEINI FATEMI Ferdowsi University of Mashhad Mashhad, Iran CHARLES W. CHOI Pepperdine University Malibu, CA, United States

This study examined willingness to communicate (WTC) in English

among Iranian EFL learners in the classroom context. For this pur-

pose, a second language willingness to communicate (L2WTC)

model based on WTC theory (MacIntyre, Clement, D€ornyei, & Noels,

1998) and empirical studies was proposed and tested using structural

equation modeling (SEM). This model examined the interrelation-

ships among WTC in English, communication confidence, motiva-

tion, classroom environment, attitudes toward learning English, and

English language achievement. A total of 243 English-major university

students in Iran completed a questionnaire. The proposed SEM

model adequately fitted the data. Results of the SEM indicated that

classroom environment was the strongest direct predictor of L2WTC;

communication confidence directly affected WTC; motivation indi-

rectly affected WTC through communication confidence; English lan-

guage proficiency indirectly affected WTC through communication

confidence; and the classroom environment directly affected atti-

tudes, motivation, and communication confidence. doi: 10.1002/tesq.204

Foreign/second language (L2) teaching has undergone many

changes and revisions over the past century. In the past, English

language teaching emphasized the mastery of structures, but more

recently the communicative competence of the language learners and

the use of language for the purpose of communication have been

emphasized (Cetinkaya, 2005). Communicative language teaching

TESOL QUARTERLY Vol. 50, No. 1, March 2016 154

© 2014 TESOL International Association 15457249, 2016, 1,

(CLT) highlights the use of language for meaningful communication D ownl

in the process of foreign and second language acquisition. As MacIn- oaded

tyre and Charos (1996) maintain, “recent trends toward a conversa- from h

tional approach to second language pedagogy reflect the belief that ttps://

one must use the language to develop proficiency, that is, one must online

talk to learn” (p. 3). L2 learners cannot become proficient unless they library.

use language communicatively. In spite of this, when language learners w iley.c

have the opportunity to use the second language, they show differ- om/do

ences in speaking the L2. Some learners seek every opportunity to i/10.1

speak the L2 in the classroom, while others remain silent. 002/te

Willingness to communicate (WTC) in the second or foreign sq.204

language is the construct that explains the differences in learners’ by Rm

intention to communicate in the L2. It is considered to be an individ- it Uni

ual difference variable and has been recently investigated by many versity

researchers (Cao, 2011; Ghonsooly, Khajavy, & Asadpour, 2012; MacIn- Libra

tyre & Legatto, 2011; Peng, 2012). WTC is defined as “a readiness to ry, Wile

enter into discourse, at a particular time with a specific person or per- y Onl

sons, using L2” (MacIntyre, Cl i

ement, D€ornyei, & Noels, 1998, p. 547). ne Lib

It is seen as the ultimate goal of language learning because a higher rary on

willingness to communicate in a foreign language (L2WTC) facilitates [28/0

L2 use (MacIntyre et al., 1998). 5/2024

L2WTC has been investigated in relation to different personality, ]. Se

affective, and social psychological variables (e.g., Cetinkaya, 2005; e the T

MacIntyre & Charos, 1996; Yashima, 2002). However, most of these erms a

studies examined L2WTC in the English as a second language nd Co

(ESL) context (Baker & MacIntyre, 2000; Clement, Baker, & nditio

MacIntyre, 2003; MacIntyre, Baker, Cl n ement, & Donovan, 2002; s (htt

MacIntyre & Charos, 1996). Previous research investigated it with a ps://on

scale developed by McCroskey and Baer (1985) where participants linelib

are placed into situations that they have rarely experienced in their rary.wi

everyday lives (e.g., talk with a friend while standing in line; Cao & ley.com

Philp, 2006; Peng & Woodrow, 2010). An important distinguishing /term

feature of the English as a foreign language (EFL) context from the s-and-

ESL context is that learners usually do not have the opportunity to condit

use the L2 outside the classroom (Oxford & Shearin, 1994). There- ions) o

fore, the language classroom is the best context for practicing and n Wile

communicating the L2 in EFL contexts. Despite this, very few stud- y Onli

ies have explored the role of the language classroom context (e.g., ne Lib

Cao, 2011; Peng, 2012; Peng & Woodrow, 2010), and if investigated rary fo

at all, most have been done in the Chinese EFL context. Further- r rules

more, none of the models examined in EFL classroom contexts of use

using structural equation modeling (SEM) has integrated a mixture ; OA a

of psychological, contextual, and linguistic variables. Given that Iran rticles

is an EFL context and no study has examined the L2WTC in the are governed b

WILLINGNESS TO COMMUNICATE IN ENGLISH 155 y the applicable Creative C 15457249, 2016, 1, language classroom context of Iran, this study examines D ownl

psychological, contextual, and linguistic variables of L2WTC in the oaded

Iranian EFL context. For this purpose, the present study proposes a from h

model to investigate these variables. The accurate examination of ttps://

this comprehensive model provides a useful viewpoint of L2 commu- online

nication in the EFL classroom context in general, and the Iranian library.

context in particular. Moreover, the proposed model can help L2 w iley.c

learners understand what factors affect their willingness to communi- om/do

cate in English. Based on this, they can become aware of their own i/10.1

communication preferences and, therefore, foster communication 002/te

and speaking in the classroom. Hence, language learners’ willingness sq.204

to communicate in English in the Iranian EFL context is examined by Rm

within the WTC framework proposed by MacIntyre et al. (1998) and it Uni

Peng and Woodrow (2010) using SEM. versity Library, Wi

English Language Teaching in Iran ley Online Lib

Formal language teaching in Iran starts at junior high school. Two rary on

languages are taught, English and Arabic, and both of them are [28/0

compulsory school subjects. However, due to its international usage, 5/2024

English is preferred to Arabic (Pishghadam & Naji, 2011). Taguchi, ]. Se

Magid, and Papi (2009) state that Iranian students learn English to e the T

enter prestigious universities, to study and live abroad, and to get erms a

access to information. English lessons involve a teacher reading short nd Co

sentences with new vocabulary words; those sentences are translated, nditio

and then the explicit grammatical rules are explained (Papi & Abdol- ns (htt

lahzadeh, 2012). At the university level, all students have to pass a ps://on

three-credit general English course, where the emphasis is on reading linelib

skills and structure (Noora, 2008). rary.wiley.com/term Willingness to Communicate s-and-condit

Willingness to communicate was originally investigated in the con- ions) o

text of first language communication. McCroskey and Baer (1985) n Wile

consider willingness to communicate as a personality trait and y Onli

explain that individuals show similar tendencies in different commu- ne Lib

nication contexts. However, it is a different concept when it is rary fo

applied in second or foreign language learning. MacIntyre et al. r rules

(1998) state that it is almost impossible to equate first language will- of use

ingness to communicate (L1WTC) with L2WTC. Following this, they ; OA a

developed a WTC model for the L2 that integrates psychological, rticles

linguistic, and contextual variables. According to this model, dual are governed b 156 TESOL QUARTERLY y the applicable Creative C 15457249, 2016, 1,

characteristics including both trait and state factors affect individuals’ D ownl

L2WTC, which is different from the trait feature of willingness to oaded

communicate in L1. Trait L2WTC refers to a stable personality char- from h

acteristic that people show in their communication in L2 (MacIntyre, ttps://

Babin, & Clement, 1999). L2WTC might best be approached, by online

both teachers and researchers, from a state-like perspective. This is library.

significant because people show differences in their communicative w iley.c

competence ranging from almost no L2 competence to full L2 com- om/do

petence (MacIntyre et al., 1998). i/10.1

Empirical research on L2WTC has revealed that it is related to 002/te

many other variables. One of the most important factors involved in sq.204

L2WTC is L2 self-confidence, and this refers to the “overall belief in by Rm

being able to communicate in the L2 in an adaptive and efficient it Uni

manner” (MacIntyre et al., 1998, p. 551). L2 self-confidence is a versity

construct composed of two dimensions: perceived competence and a Libra lack of anxiety (Cl r

ement, 1980, 1986). Perceived competence refers y, Wile

to learners’ self-evaluation of their L2 skills (Peng, 2009), and for- y Onl

eign language anxiety is defined as “worry and negative emotional ine Lib

reaction aroused when learning or using a second language” (Mac- rary on

Intyre, 1999, p. 27); foreign language anxiety is seen as one of the [28/0

obstacles to L2 learning and achievement. L2 self-confidence was 5/2024

found to be the most significant predictor of L2WTC in many stud- ]. Se

ies (Cetinkaya, 2005; Ghonsooly et al., 2012; Kim, 2004; Peng & e the T

Woodrow, 2010; Yashima, 2002; Yashima, Zenuk-Nishide, & Shimizu, erms a 2004). nd Conditions (ht Motivation and Attitudes tps://onlinelib

Research in the field of L2 motivation began with the work of Gard- rary.wi

ner and his associates (Gardner, 1985; Gardner & Lambert, 1972). In ley.com

Gardner’s (1985) socioeducational model of second language acquisi- /term

tion, groups of attitudes—integrativeness and attitudes toward the s-and-

learning situation—support the learners’ level of L2 motivation. Moti- condit

vation is measured by L2 learners’ desire to learn the L2, motivational ions) o

intensity, and the attitudes toward L2 learning. These three clusters n Wile

(integrativeness, attitudes toward the learning situation, and motiva- y Onli

tion) are called integrative motive. ne Lib

Early research on L2WTC utilized the socioeducational framework rary fo

by applying motivation and integrativeness as two important variables r rules

in MacIntyre et al.’s (1998) pyramid model. Although Gardner’s socio- of use

educational model was a dominant theory of motivation, it has its own ; OA a

limitations; among them is its limited applicability in foreign language rticles

settings (D€ornyei, 1990; Oxford & Shearin, 1994). The reason is that are governed b

WILLINGNESS TO COMMUNICATE IN ENGLISH 157 y the applicable Creative C 15457249, 2016, 1,

in EFL contexts language learners do not communicate with the target D ownl

language community but learn the foreign language in the classroom. oaded

Because foreign language learners do not have sufficient contact with from h

the target language community, they may not form attitudes toward ttps://

the target community (D€ornyei, 1990). online

Motivational studies changed their focus to cognitive and humanis- library.

tic aspects of motivation during the 1990s. One of the most salient w iley.c

educational psychology theories of this period is self-determination om/do

theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985). SDT claims that human beings have i/10.1

three innate psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and related- 002/te

ness. Autonomy refers to the sense of unpressured willingness to per- sq.204

form an action, competence is the need for showing one’s capacities, by Rm

and relatedness is the need that a person feels he or she belongs with it Uni

and is connected with significant others. It is proposed that the degree versity

of satisfaction of these needs leads to different types of motivation Libra (Deci & Ryan, 2000). ry, Wile

Noels, Pelletier, Clement, and Vallerand (2000) applied SDT to L2 y Onl

research, investigating the role of intrinsic and extrinsic motives. ine Lib

Intrinsic motivation refers to the desire to do something because it is rary on

interesting and pleasing. When learning is a goal in itself, and students [28/0

find the task interesting and challenging, they are intrinsically 5/2024

motivated. Extrinsic motivation comes from external factors, that is, ]. Se

learning for instrumental goals (such as earning reward or avoiding e the T

punishment). Intrinsic motivation is composed of three parts: knowl- erms a

edge refers to motivation to do an activity for exploring new ideas, nd Co

accomplishment is the sensation of achieving a goal or a task, and stimu- ndition

lation is the fun and excitement involved in doing a task. s (htt

Consistent with Deci and Ryan’s (1985) SDT theory, Noels et al. ps://on

(2000) also distinguish three types of extrinsic motivation: external, in- linelib

trojected, and identified regulation. r

External regulation, which is the ary.wi

least self-determined type of motivation, refers to activities that are ley.com

external to the learner, such as tangible benefits. The second type of /term

motivation, which is more internal, is introjected regulation. It refers to s-and-

doing an activity due to some kind of internal pressure, such as condit

avoiding guilt or ego enhancement. The most self-regulated type of ions) o

extrinsic motivation is identified regulation; this is where students carry n Wile

out an action due to personally related reasons and a desire to attain y Onli

a valued goal. Noels et al. also state that, when students have neither ne Lib

an intrinsic nor extrinsic reason to do an action, they are unmotivated rary fo

and they will leave the activity as soon as possible. r rules

One of the features of SDT is that, unlike the socioeducational of use

model, it can be applied in EFL classroom contexts. The rationale for ; OA a

choosing SDT as the motivational framework, according to Peng and rticles

Woodrow (2010), is that, first, the theoretical principles of SDT relate are governed b 158 TESOL QUARTERLY y the applicable Creative C 15457249, 2016, 1,

human beings’ basic psychological needs to environmental factors D ownl

(this is consistent with the ecological perspective of the present study). oaded

Second, the socioeducational model is useful for examining the from h

motivational patterns of multilingual contexts, but has little explor- ttps://

atory power for understanding and explaining motivational features in online

the EFL classrooms (D€ornyei, 2005). Therefore, the present study, library.

which was conducted in an Iranian EFL classroom context, uses SDT w iley.c as the motivational framework. om/doi/10.1002/te Language Classroom Environment sq.204 by Rm

Many researchers in the field of social psychology believe that behav- it Uni

ior is specific to the situation in which it occurs (MacLeod & Fraser, versity

2010). In other words, behavior is a function of both environment and Libra

person. From an ecological point of view, which examines how each ry, Wile

component in a context is related to other components, the notion of y Onl

context in L2 learning is emphasized (Cao, 2009). Also, based on Bron- ine Lib

fenbrenner’s (1979) ecological perspective on human development, rary on

both person and environment play a part in development. The ecologi- [28/0

cal approach to research in language classrooms has recently attracted 5/2024

the attention of L2 researchers (Cao, 2009, 2011; Peng, 2012; Peng & ]. Se

Woodrow, 2010). The ecological perspective in language learning con- e the T

siders individuals’ cognitive processes related to their experiences in the erms a

physical and social world (Leather & Van Dam, 2003). nd Co

Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological perspective investigates human nditio

development across a set of interrelated structures called ecosystems. ns (htt

There are four layers within this model: microsystem, mesosystem, exo- ps://on

system, and macrosystem. The microsystem is the innermost layer and linelib

is the immediate setting which contains the developing person. This rary.wi

layer is related to a face-to-face interaction with persons and objects in ley.com

the immediate situation (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). The mesosystem /term

examines the developing person in situations beyond the immediate s-and-

setting. The exosystem comprises the linkages and processes taking condit

place between two or more settings, at least one of which does not ions) o

contain the developing person, but in which events occur that indi- n Wile

rectly affect processes in a person’s immediate setting (Bronfenbren- y Onli

ner, 1979). Finally, the macrosystem involves micro-, meso-, and ne Lib

exosystems as a manifestation of a particular culture or subculture. It rary fo

was Peng (2012), based on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological perspective, r rules

who provided operational definitions of these layers with regard to of use

L2WTC. As examples of these ecosystems, the language classroom is ; OA a

considered as a microsystem (the home environment), students’ past rticles

experiences outside the language classroom are considered examples are governed b

WILLINGNESS TO COMMUNICATE IN ENGLISH 159 y the applicable Creative C 15457249, 2016, 1,

of a mesosystem (Peng, 2012), and curriculum design and course D ownl

assessments are examples of an exosystem. The sociocultural and oaded

educational context in Iran is an example of a macrosystem (Peng, from h 2012). ttps://

Some studies have applied this model to explain the dynamic and online

situational nature of L2WTC (Cao, 2009; Kang, 2005; Peng, 2012). library.

Research in L2WTC has indicated that students’ motivation, beliefs, w iley.c

teaching methods, attitudes, L2 proficiency, and self-confidence are om/do

among the factors that are related to the microsystem—that is, the lan- i/10.1

guage classroom itself (Cao, 2011; Peng, 2012). 002/te

The microsystem level of L2WTC, or the very context of the class- sq.204

room environment, is the main focus of the present study. Therefore, by Rm

in the current research, characteristics of both environment and per- it Uni

son are explored for a better understanding of L2WTC in the Iranian versity

EFL context. For this purpose, six variables were selected in line with Libra

the microsystem level of the ecological perspective: L2WTC, L2 self- ry, Wile

confidence, L2 motivation, classroom environment, attitudes, and L2 y Onl

achievement. L2WTC, L2 self-confidence, L2 motivation, and attitudes ine Lib

are considered as individual differences variables. L2 achievement is rary on

considered as a linguistic variable, and the classroom environment is [28/0

used to capture the role of contextual variables in L2WTC. The ratio- 5/2024

nale for choosing these variables was based on MacIntyre et al.’s ]. Se

(1998) pyramid model and Peng and Woodrow’s (2010) findings in e the T the classroom environment. erms a

Peng and Woodrow (2010) considered only three components of nd Co

the language classroom environment: teacher support, student cohe- nditio

siveness, and task orientation. Their justification for selecting these ns (htt

variables was based on previous empirical research that showed that ps://on

the teacher, the students, and the learning tasks were the relevant fac- linelib

tors in the language classroom environment (Cl r ement, D€ornyei, & ary.wi

Noels, 1994; Williams & Burden, 1997). ley.com

Teacher support refers to the extent to which the teacher helps, /term

supports, trusts, befriends, and is interested in students (Dorman, s-and-

Fisher, & Waldrip, 2006). Wen and Clement (2003) explain that the condit

teacher’s support might have a direct effect on WTC. Student cohe- ions) o

siveness refers to the extent to which students know, help, and support n Wile

each other (Dorman et al., 2006). Clement et al. (1994) found that y Onli

student cohesiveness greatly influenced interaction and learning in ne Lib

the classroom. Learners in a cohesive group may feel more encour- rary fo

aged to study and perform learning tasks (Peng, 2009). Task orienta- r rules

tion refers to the extent to which it is important to complete activities of use

and solve problems (Dorman et al., 2006). Attractive and useful tasks ; OA a

lead to student engagement, and tasks that are meaningful, relevant, rticles are governed b 160 TESOL QUARTERLY y the applicable Creative C 15457249, 2016, 1,

and have a reasonable degree of difficulty can enhance performance D ownl quality (Kubanyiova, 2007). oaded from https:/ Hypothesized Model /onlinelibrary.

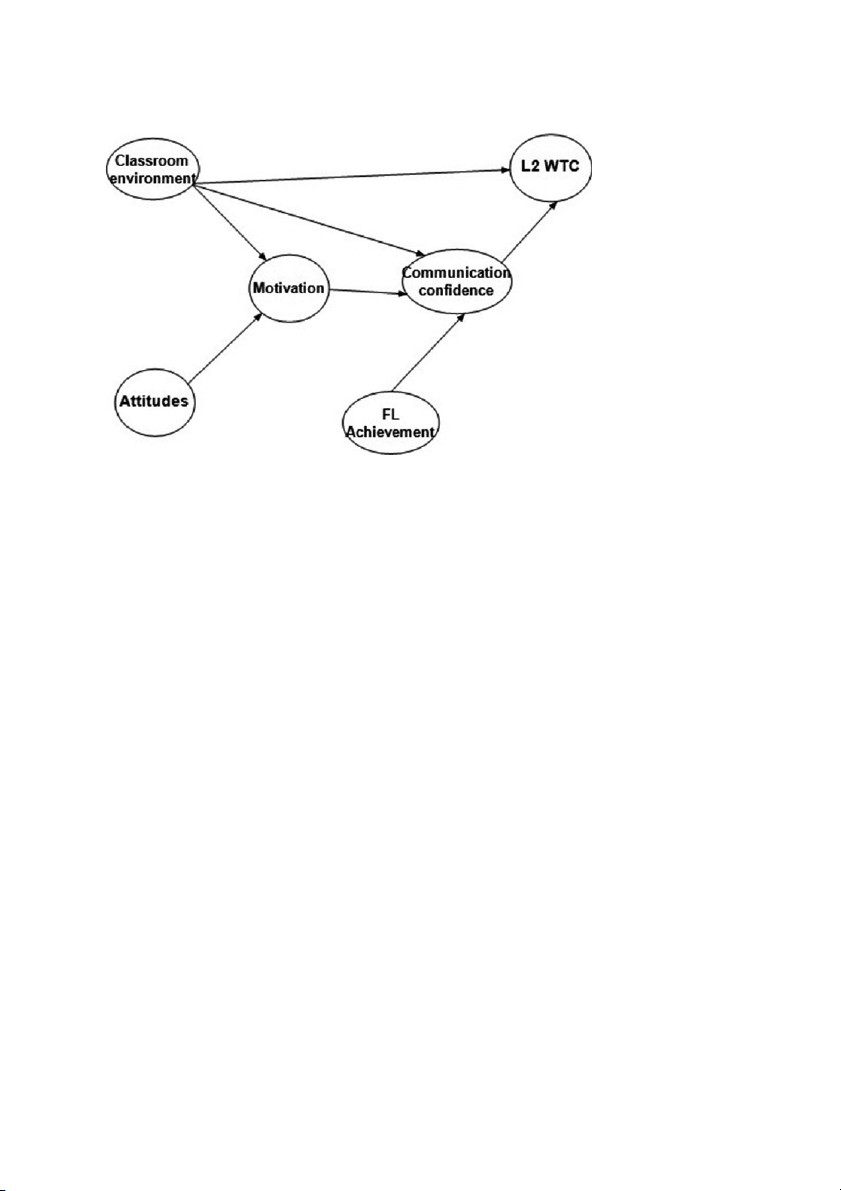

In order to examine the interrelationships between the selected w iley.c

variables (i.e., L2WTC, communication confidence, motivation, atti- om/do

tudes toward learning English, English language achievement, and i/10.1

classroom environment), a structural model is proposed. Model speci- 002/te

fications are based on the knowledge of the theory and/or empirical sq.204 research (Byrne, 2010). by Rm

Consistent with the L2WTC theory (MacIntyre et al., 1998) and pre- it Uni

vious empirical studies (Cetinkaya, 2005; Ghonsooly et al., 2012; Peng versity

& Woodrow, 2010; Yashima, 2002), we hypothesize a path from com- Libra

munication confidence to L2WTC. ry, Wile

Following Peng and Woodrow (2010), we hypothesized that class- y Onl

room environment directly influences motivation, communication con- ine Lib

fidence, and L2WTC. Therefore, three paths from classroom rary on

environment to motivation, communication confidence, and L2WTC [28/0 were hypothesized. 5/2024

MacIntyre et al.’s (1998) pyramid model shows that motivation indi- ]. Se

rectly affects L2WTC. Recent empirical studies (Cetinkaya, 2005; e the T

Ghonsooly et al., 2012; Peng & Woodrow, 2010; Yashima, 2002) have erms a

also indicated that motivation influences L2WTC indirectly through nd Co

communication confidence. Accordingly, we added a path from moti- nditio

vation to communication confidence. ns (htt

In MacIntyre et al.’s (1998) pyramid model, L2 proficiency is ps://on

among the factors that indirectly affects L2WTC. Although Yashima’s linelib

(2002) findings did not show the significant effect of L2 achievement rary.wi

on communication confidence, Gardner, Tremblay, and Masgoret ley.com

(1997) indicated that L2 achievement is a very strong predictor of /term

communication confidence. In the present study, a path from L2 s-and-

achievement to communication confidence was drawn. condit

Finally, a path from attitudes to motivation was postulated. This ions) o

path was based on Gardner’s socioeducational model and empirical n Wile

research (Gardner et al., 1997; MacIntyre & Charos, 1996) in which y Onli

attitudes affect motivation. It should be noted that in the present study ne Lib

only attitudes toward learning English were included to make it fit in rary fo

the EFL classroom context. The hypothesized model is shown in r rules Figure 1.

of use; OA articles are governed b

WILLINGNESS TO COMMUNICATE IN ENGLISH 161 y the applicable Creative C

15457249, 2016, 1, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/tesq.204 by Rmit University Library, Wiley Online Library

FIGURE 1. Proposed model of WTC in English in the Iranian EFL classroom context. on [28/05/202 METHODOLOGY 4]. See the Setting and Participants Terms and Co

A total of 243 undergraduate EFL university students participated in nditio

this study, including 148 females (60.9%), 84 males (34.6%), and 11 ns (htt

(4.5%) participants who did not disclose their gender. Participants ps://on

were selected from two universities in a city in the northeast of Iran. linelib

All participants had passed the highly competitive university entrance rary.wi

exam, and all of them were studying English as an academic major. ley.com

The age range of the participants was 18–42; the mean age was 21.87 /term

(SD = 2.97). Age information was missing for 13 participants. We did s-and

not select non–English major university students because they do not -condi

develop a functional English proficiency, they do not have the chance tions)

to speak English in classrooms, and their English class time is limited on Wil

to reading and vocabulary. Therefore, asking them about situations in ey Onl

which they speak English in the classroom would be irrelevant. ine Library for rule Instrumentation s of use; OA a

WTC in English. Ten items from Peng and Woodrow (2010, rticles

adapted from Weaver, 2005) were used in this study to measure WTC are governed b 162 TESOL QUARTERLY y the applicable Creative C 15457249, 2016, 1,

in English. Previous research (Peng & Woodrow, 2010) has shown a D ownl

two-factor solution for WTC in English: WTC in meaning-focused activ- oaded

ities (e.g., giving a speech in the classroom) includes six items, and from h

WTC in form-focused activities (e.g., asking the meaning of a word) ttps://

includes four items. Students answered the questions on a 7-point online

Likert scale from 1 (definitely not willing) to 7 (definitely willing). The library.

items assess the extent to which the participants are willing to commu- w iley.c

nicate in certain classroom situations. om/doi/10.1

Perceived communicative competence in English. Six items from 002/te

Peng and Woodrow (2010, adapted from Weaver, 2005) were used on sq.20

an 11-point can-do scale ranging from 0% to 100%. Students were 4 by R

asked to show the percentage of the time they felt competent commu- m it Un nicating in English. iversity Libr

Communication anxiety in English. Ten items from Horwitz (1986) ary, W

were translated and validated by Khodadady and Khajavy (2013) in the iley On

Iranian context. The scale was used for assessing communication anxi- line L

ety on a 7-point Likert scale measuring the extent to which the partici- ibrary

pants felt anxious in various classroom communication situations from on [28

1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). A sample item is “I start to /05/20

panic when I have to speak without preparation in language class.” 24]. See the

Autonomous motivation to learn English. Eighteen items from Term

Noels et al. (2000) translated and validated by Khodadady and Khajavy s and

(2013) in the Iranian context were used to measure subcomponents of C ondit

intrinsic motivation (knowledge, accomplishment, and stimulation) ions (h

and extrinsic motivation (external, introjected, and identified regula- ttps://

tion) from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree) on a Likert scale. onlinel

In this study, to have an overall indicator of perceived autonomy, we ibrary.

used the Relative Autonomy Index (RAI; Ryan & Connell, 1989). To w iley.c

this end, first, a weight was assigned to each of the motivational sub- om/te scales (external regulation, 2; introjected, 1; identified, +1; knowl- rm s-a

edge, +2, accomplishment, +2; and stimulation, +2). Then, these nd-con

weighted scores were summed. A higher RAI score demonstrates a ditions

higher level of autonomous (self-determined) motivation. A sample ) on W

item is “I learn English in order to get a more prestigious job later iley O on.” nline Library

Classroom environment. Thirteen items from Peng and Woodrow for ru

(2010, adapted from Fraser, Fisher, & McRobbie, 1996) were used for les of

assessing classroom environment. These items measured teacher sup- use; O

port, student cohesiveness, and task orientation on a 7-point Likert A articles are governed b

WILLINGNESS TO COMMUNICATE IN ENGLISH 163 y the applicable Creative C