[ 10] CLASSICAL MUTAGENESIS TECHNIQUES 189

[I O] Classical Mutagenesis Techniques

By CHRISTOPHER W. LAWRENCE

Introduction

Generating mutants, to identify new genes and to study their properties, is the

starting point for much of molecular biology. Forward mutations and metabolic

suppressors obtained by reversion can provide powerful insights into the functions

and relationships of normal gene products. Similarly, mutations and intragenic

revertants provide the raw material for the analysis of gene product structure-

function relationships. Site-specific mutagenesis and other methods based on

recombinant DNA techniques are increasingly used for these purposes, and they

are clearly the methods of choice where particular changes in specified genes

or genetic sites are needed. Nevertheless, classical methods, in which cells are

treated with mutagens, are likely to remain the chief means for inducing mutations

in many circumstances because they require no prior knowledge of gene or product

and are generally applicable: the user need only specify an appropriate alteration

in phenotype. However, unless selection for the desired strain is possible, hunt-

ing for mutants can be extremely laborious and analyzing the material obtained

even more so. Good planning, efficient mutagenesis, careful choice of strain, and

effective mutant detection usually pay off in time and labor.

Choice of Mutagen and Dose

The best mutagens for most purposes are those that induce high frequencies

of base-pair substitutions and little lethality. The widely used alkylating agents

N-methyl-N'-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) and ethylmethane sulfonate

(EMS) fulfill these criteria but are highly specific in their action: they almost

exclusively produce transitions at G-C sites.1 For most purposes, such as forward

mutagenesis, this specificity is unlikely to pose any problem, though it may be

a disadvantage when, as in some kinds of reversion, particular kinds of muta-

tions at specified sites are needed. Germicidal ultraviolet light (254 nm UV) is

also a fairly efficient mutagen, and it has the advantage of producing a greater

range of substitutions 2,3: most occur in runs of pyrimidines, particularly T-T pairs,

and include both transitions and transversions. UV also induces a significant fre-

quency of frameshift mutations, almost exclusively of the single nucleotide deletion

variety. One or other of the chemical mutagens together with UV are likely to satisfy

1 S. E. Kohalmi and B. A. Kunz,

J. Mol. Biol.

204, 561 (1988).

2 B. A. Kunz, M. K. Pierce, J. R. A. Mis, and C. N. Giroux,

Mutagenesis

2, 445 (1987).

3 G. S. E Lee, E. A. Savage, R. G. Ritzel, and R. C. von Borstel,

Mol. Gen. Genet.

214, 396 (1988).

Copyright 2002. Elsevier Science (USA).

All rights reserved.

METHODS IN ENZYMOLOGY, VOL. 350 0076-6879/02 $35.00

190 MAKING MUTANTS [ 101

most experimental needs, and it may be an advantage to induce different samples

of mutants with each of these agents (for an example, see Ref. 4). Although base-

pair substitution mutagens have most general utility, the alkylating acridine mus-

tard ICR- 170 (2-methoxy-6-chloro-9- [3-(ethyl-2-chloroethyl)aminopropylamino]

acridine dihydrochloride can be used when + 1 frameshift mutations are required. 5-7

The majority of mutations induced by this agent are single G insertions in runs of

two or more G's, with preference for runs of three or more G's. 7

Choosing an optimal dose usually requires balancing the competing needs for

a high mutation frequency, reasonably high survival, and avoidance of multiple

mutations. The highest proportion of mutants per treated cell is usually found at

doses giving 10 to 50% survival. The highest fraction of mutations per surviving

cell most commonly requires a larger dose, but mutation frequencies often decline

at very high doses. In any case, it is desirable to avoid doses that kill more than

95% of cells, because they may select multicell clusters or atypically resistant

variants, which occur spontaneously in all cell populations. In addition, multiple

mutants become more common and may interfere with analysis. An indication

of the effectiveness of the mutagenic treatment in the particular strain used can

be obtained by measuring the frequency of canavanine-resistant mutants that it

induces.

Growth Conditions after Mutagen Treatment

After being treated with mutagens, cell cultures should be allowed to grow

for several generations under nonselective or permissive conditions, to enhance

the production and expression of mutations. With some mutagens, such as EMS,

mutations are thought to occur principally during S-phase replication, and un-

repaired damage can continue to produce mutations in successive generations.

However, with others, such as UV, most mutations probably occur during G1 ex-

cision repair synthesis. Growth is also required to promote dilution and turnover

of gene products, or the synthesis of new ones, to allow full expression of the

mutant or revertant phenotype. In addition, cells may require time to recover from

mutagen damage, which can cause some cells to stop growing temporarily or to

grow more slowly. Full recovery from mutagen damage is particularly important

when mutagen enrichment procedures are used.

Various ways of accomplishing outgrowth of mutagenized cultures can be

chosen, depending on experimental needs. Plating dilutions of treated cells on

solid medium, to get colonies for screening, has the advantage that each induced

mutation identified is of independent origin. Many of the desired mutations may

occur as sectors in otherwise normal colonies, however, and therefore be hard to

4 R. Sitcheran, R. Emter, A. Kralli, and K. R. Yamamoto,

Genetics

156, 963 (2000).

5 D. J. Brusick,

Murat. Res.

10, 11 (1970).

6 M. R. Culbertson, L. Charnas, M. T. Johnson, and G. R. Fink,

Genetics

86, 745 (1977).

7 L. Mathison and M. R. Culbertson,

Mol. Cell. Biol.

5, 2247 (1985).

[ 101 CLASSICAL MUTAGENESIS TECHNIQUES 191

detect by some screening procedures. Outgrowth in liquid medium is convenient

and allows segregation of pure mutant clones, but different mutant isolates may

represent repeat copies of the same, rather than independent, mutational events.

If outgrowth in liquid medium is needed, independent mutations can be isolated

by dividing the mutagenized culture before outgrowth and taking a single mutant

from each subculture. However, more than one mutant can be taken if they are

shown to be different by sequence analysis. When selective methods allow a large

number of cells to be spread on each plate, as in the selection of prototrophs from

an auxotrophic strain, outgrowth can be achieved by adding small amounts of the

required nutrilite to the medium. In experiments of this kind it is usually advisable

to spread no more than about 107 cells on each plate, since the efficiency with

which revertants are recovered drops greatly at higher cell densities. Finally, it

should be noted that all mutagens increase the frequency of rho ° petites, some,

like ICR-170, to very high levels. It may therefore be useful to grow mutagenized

cultures in medium containing a nonfermentable carbon source, such as glycerol,

to avoid recovering such strains.

Choice of Strain

With many experimental species, it is customary to isolate mutations in a

designated wild-type strain or genetic background, but there is no such wild type

of

Saccharomyces cerevisiae

in general laboratory use. However, many mutations

have been isolated in the haploid strains A364A and $288C, both of which are

obtainable from the Yeast Genetics Stock Center (Berkeley, CA). In addition, a

pair of strains of opposite mating type, X2180-1A and X2180-1B, that are both

isogenic with $288C are also available. These are useful for mutant "cleanup"

(see below).

Although these strains are sometimes useful, for many purposes it will be

necessary to select a strain tailored to meet the investigator's specific experimental

needs, and it is particularly important to examine the strain chosen carefully, to

ensure its suitability. In addition to building into it any particular mutations that

may be required for enrichment, selection, mutant detection, or analytical methods,

it is prudent to check that the parental strain performs satisfactorily with respect

to mating, transformation, and, when crossed to other strains, sporulation, since

some laboratory strains perform poorly in these respects. Nonflocculent strains

that give single-budded cells directly or after brief sonication are also highly

desirable. Further, haploid yeast strains may carry additional copies of one or

more chromosomes, and such aneuploidy may underlie the not-uncommon failure

to recover mutations at one locus, even though similar mutations at other loci are

found readily. When exhaustive mutagenesis studies are planned, it may there-

fore be desirable to use a variety of unrelated strains. Alternatively, the presence

of aneuploidy in the parental strain can be investigated genetically, by crossing it

with strains carrying recessive markers and analyzing the tetrads. Aneuploidy is

192 MAIONG MUTANTS [ 101

unlikely if2 : 2 segregation for these markers is observed. Pulsed gel electrophoresis

may also be used to detect aneuploidy. 8'9

Mutant Enrichment Procedures

Although mutants can sometimes be selected, they more often can be isolated

only by screening individual clones from mutagenized cell populations, a highly la-

borious process. Enrichment procedures, which increase the proportion of mutants,

can sometimes be used to reduce this labor. Various procedures of this kind have

been proposed, 1°-13 but most depend on the same principle: the use of conditions

which temporarily prevent mutant, but not nonmutant, growth and which pro-

mote the selective killing of growing cells. The method using inositol starvation 12

to achieve selective killing is convenient and has been widely used. For good

enrichment with mutagenized cultures, the cells must be grown nonselectively

for several generations, to allow mutant expression and to promote recovery of

damaged, but nonmutant, cells. To ensure the independent origin of the mutants

eventually isolated, such outgrowth can be done on solid medium. Alternatively,

a single mutant can be isolated from each of a series of liquid cultures.

Mutant "Cleanup"

Since strains treated with powerful mutagens often contain mutations in more

than one gene, the mutant phenotype initially observed may be a misleading com-

pound of several individual phenotypes. It is therefore usually helpful to "clean up"

the strain by placing the mutation of interest in a nonmutagenized genetic back-

ground. This can be done by repeated backcrossing to an untreated isogenic strain

or, if the locus in question's identity is known, by cloning the mutant gene by

PCR (polymerase chain reaction) and transferring it to an untreated strain by gene

replacement.

Safety

Powerful mutagens are powerful carcinogens: their use and disposal require

care. Chemical mutagens should be handled only in a hood, using protective

8 M. V. Olsen,

in

"The Molecular Biology of the Yeast

Saccharomyces,

Genome Dynamics, Protein

Synthesis, and Energetics" (J. R. Broach, J. R. Pringle, and E. W. Jones, eds.), p. 1. Cold Spring

Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, 1991.

9 A. J. Link and M. V. Olsen,

Genetics,

681 (1991).

1o R. Snow,

Nature (London)

211, 206 (1966).

11 B. S. Littlewood,

in

"Methods in Celt Biology" (D. M. Prescott, ed.), Vol. 11, p. 273. Academic

Press, New York, 1975.

12 S. A. Henry, T. E Donahue, and M. R. Culbertson,

Mol. Gen. Genet.

143, 5 (1975).

13 M. T. McCammon and L. W. Parks,

MoL Gen. Genet.

186, 295 (1982).

[ 10] CLASSICAL MUTAGENESIS TECHNIQUES 193

clothing, gloves and eye protection. MNNG decomposes to release volatile di-

azomethane, a powerful carcinogen, and EMS is itself volatile. Handle open bottles

only in a hood in good working condition (i.e., air flow at face height of 150 fpm)

with the window closed as much as possible, and avoid inhaling the volatile

materials. Keep a freshly made supply of 10% (w/v) sodium thiosulfate on hand, to

deal with accidental spills. Treatments with MNNG and EMS can be stopped, and

the mutagens destroyed, by making the cell suspension 5% in sodium thiosulfate,

using a filter-sterilized stock solution of this reagent. ICR-170, removed from cells

by centrifugation, can be destroyed by making the solution 0.1 M in sodium hy-

droxide. Supernatants of inactivated chemical mutagens are often toxic, so should

be handled with care; consult your institutional hazardous waste unit with respect

to their disposal. Germicidal UV (principally 254 nm UV) is particularly damag-

ing to the eyes, but it can also cause sunburn and skin cancer, and it is important

to avoid all exposure of the skin to the radiation by wearing a UV-opaque face

mask, opaque gauntlet gloves, and protective clothing if exposure is anticipated.

UV tubes should be housed in a wood or metal structure, with screened ventilation

louvers, painted matte black. Samples being irradiated can be observed through

6-mm-thick Lucite, which effectively blocks scattered UV.

Methods

MNNG and EMS Mutagenesis

1. Inoculate 10 ml (or other appropriate volume) of liquid YPD medium with a

freshly subcloned sample of the yeast strain to give approximately 1 x 106 cells/ml

(just detectably turbid). Incubate overnight at 30 ° with vigorous shaking. In the

morning, the culture should contain about 2 x 108 cells/ml.

2. Wash 2.5 ml of the overnight culture twice in 50 mM potassium phosphate

buffer, pH 7.0, and resuspend in 10 ml of this buffer. Cell concentration should be

~5

x l0 7

cells/ml. Check cell concentration with a hemocytometer, and adjust if

necessary. Observation of the cells on the hemocytometer slide will also indicate

the presence of cell clumping. If sonication is needed to disperse clumped cells,

chill cell suspension in ice and sonicate for 15 sec. A second cycle of chilling

and sonication can be given, but further cycles are unlikely to be of benefit. As

mentioned above under "Choice of Strain," it is important to select a strain that

gives single-budded cells directly, with brief sonication.

3. (a) For MNNG mutagenesis, add 40 #1 of a solution of MNNG in acetone

(10 mg/ml) to 10 ml of cells in a screw-cap glass tube, tighten the cap, and mix well.

Carry out all operations in a hood, wear gloves and a laboratory coat, and avoid

inhaling volatile substances. Incubate in the tightly capped tube at 30 ° without

shaking for 60 min. Add 40 lzl of acetone without MNNG to an identical cell

suspension to serve as control and for the determination of cell survival. The

MNNG solution is made by dispensing (in a hood, with window lowered as much

194 MAKING MUTANTS [ 10]

as possible) approximately 10 mg of MNNG into a capped, preweighed glass vial,

followed by reweighing and the addition of a sufficient volume of acetone to bring

the concentration to 10 mg/ml. Transfer MNNG from bottle to vial over a tray,

to catch accidental spills. Do not attempt to weigh in a hood, since the air flow

interferes with this process. MNNG is light sensitive, and the vial should therefore

be wrapped in aluminum foil or otherwise darkened, and the mutagen handled in

subdued light.

(b) For EMS mutagenesis, add 300/zl of EMS to 10 ml of cells in a screw-cap

glass tube, tighten the cap well, and vortex vigorously: EMS is poorly miscible in

the buffer. Incubate for 30 min at 30 ° with shaking. Carry out all operations in a

hood, wear gloves and a laboratory coat, and avoid inhaling volatile substances.

Most commercial samples of EMS contain contaminants that increase its toxicity

but not mutagenicity: redistilled EMS is a significantly better mutagen. Set up an

identical cell suspension without EMS to serve as control.

4. Stop MNNG and EMS mutagenesis in the cell suspensions by adding, in

a hood, an equal volume of a freshly made 10% (w/v) filter-sterilized solution

of sodium thiosulfate, mixing well, collecting the cells by centrifugation, and

washing them twice with sterile water. Dispose of the supernatants carefully, as

recommended by your institutional toxic waste facility. Treat control cells in the

same manner.

5. Incubate the cells in liquid medium or on plates as appropriate for the

particular experimental needs. The mutagen doses suggested above kill 50 to 90%

of the cells of most strains, but it is usually desirable to check the survival level of

the particular strain used by plating suitable dilutions of both treatod and untreated

cells. A dose-response determination, if one is needed, is best carded out by

exposing cells to varying concentrations of mutagen for a fixed time, since some

chemical mutagens undergo destruction in solution.

ICR-170 Mutagenesis

1. Inoculate 10 ml of liquid YPD medium with a freshly subcloned sample

of the yeast strain to give approximately 1 x 106 cells/ml (just detectably turbid).

Incubate overnight at 30 ° with vigorous shaking. Accurately determine the cell

concentration with a hemocytometer.

2. Inoculate 40 ml of liquid YPD with a sufficient volume of the overnight

to give a final cell concentration of 1 x 104 cell/ml, incubate at 30 ° with vigorous

shaking, and collect the cells by centrifugation when the culture reaches 1-3 x 107

cells/ml (mid log phase). Wash the cells twice with sterile water, resuspend the

pellet in 20 ml of 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and shake at 30 ° for

12hr.

3. Collect the starved cells by centrifugation and resuspend the pellet in sterile

water to a concentration of 2 x 106 cells/ml. Add 1 ml of an aqueous solution

[ 10] CLASSICAL MUTAGENESIS TECHNIQUES 195

containing 0.25 mg/ml of ICR-170 to 9 ml of the cell suspension, and treat for

60 min. Carry out exposure to the mutagen under red light in a dark room to

avoid photodynamic effects, which principally kill cells rather than mutating them.

Collect cells by centrifugation, and wash twice with water. Add 1 ml of water to

9 ml cells and handle identically to serve as control. To destroy the mutagen

in supernatants, make them 0.1 M in sodium hydroxide. Dispose of the treated

supernatants as advised by your institutional toxic waste facility.

4. Incubate the cells in liquid medium or on plates as appropriate for the

particular experimental needs. The mutagen dose suggested above should result

in 5-10% survival, but it is usually desirable to check survival in the particular

strain used. Highest mutation frequencies are found by starving mid-log-phase

cells, though the extent of their advantage over stationary-phase cells varies with

strain. 5

UV Mutagenesis

1. Inoculate 10 ml of liquid YPD medium with a freshly subcloned sample

of the yeast strain to give approximately 1 × 106 cells/ml (just detectably turbid).

Incubate overnight at 30 ° with vigorous shaking. In the morning, the culture should

contain about 2 × 108 cells/ml.

2. Wash cells twice in sterile water, sonicate if necessary, and irradiate them

either on plates or in suspension, according to need. Turn on UV tubes at least

10-15

min before use, to allow them to come to a constant temperature. To irradiate

on plates, spread 200/zl of an appropriate dilution of the cell suspension on each

plate, allow the liquid to be absorbed, and expose them, with lids removed, to

50 J/m 2 UV (or for an empirically determined time). Carry out the irradiation

under illumination from "gold" fluorescent lights (e.g., F40GO, Philips Lighting

Co., Somerset, New Jersey), or very low light, and incubate the plates in the dark

for at least 24 hr, to avoid photoreactivation. To irradiate suspensions, 30-50 ml

of washed cells in 0.9% (w/v) KC1 is placed in a standard 9-cm petri dish, stirred

vigorously and continuously with a magnetic mixer, and exposed to UV with

petri dish lid removed. Depending on the cell concentration, most suspensions

significantly absorb and scatter UV, and suspensions therefore usually need to be

exposed to higher UV fluences than cells on plates, to achieve the same level of

killing and mutagenesis. As a rough rule of thumb, relative to plates, suspensions

of 106 cells/ml or less should be exposed to equal UV fluences, suspensions of

107 cells/ml exposed to 1.5-fold higher fluences, and suspensions of 108 cells/ml

to 10-fold higher fluences. However, strains vary in this respect and an empirical

check on killing is desirable. High cell concentrations are best given long UV

exposures (5-10 min) at low fluence rates, but even so the results are often less

reproducible. If very long exposures are required, evaporation can be minimized

by covering the cell suspension with polyethylene film (e.g., a single layer cut

196 MAKING MUTANTS [ 101

from a thin food bag), secured around the dish with a rubber band. Most films

reduce the UV fluence by only 10-15%, but check the transmittance of a sample

in a spectrophotometer. Protect cells from photoreactivation as before.

A convenient source of UV can be made by enclosing G8T5 germicidal UV

tubes in a box containing ventilation holes screened with matte-black painted

panels to prevent the escape of direct or scattered radiation. Ventilation is needed

because the relative output of the tube at 254 nm, the major effective wavelength,

depends on tube temperature, which optimally should be about 30 °. A tube-to-

sample distance of at least 50 cm is needed to give uniform radiation. Tightly

woven metal mesh makes an excellent neutral filter to reduce fluence rates if this

is necessary.

A fluence of 50 J/m 2 kills about 50% of the cells in many strains, but it is

often easier to determine exposure time empirically. Many commercial UV meters

underread fluence rates by as much as a factor of 2, because they are calibrated

against collimated beams; depending on the particular arrangement of tubes and

kind of container used, cells are usually exposed to a wider arc of radiation than

a collimated beam. If needed, fluence rates for specific circumstances can be

determined by potassium ferrioxalate actinometry. 14

Checking Effectiveness of Mutagen Treatment

Some indication of the effectiveness of a given mutagen treatment in the

particular strain chosen can be obtained by measuring the frequency of canavanine-

resistant mutants that it induces. Resistance to high concentrations of canavanine,

an arginine analog, results from mutations that inactivate the arginine permease,

which prevents canavanine uptake. Strains auxotrophic for arginine cannot there-

fore be used, except those carrying

arg6

or

arg8

mutations, in which the arginine

requirement can be met by substituting ornithine.

Measurement of the frequency of canavanine resistant mutants is conveniently

estimated by the top agar method. 15 Spread ~"5 x 106 treated cells on synthetic

dextrose complete medium lacking arginine (SC-ARG), and suitable dilutions of

the cell suspension to measure survival. Also plate untreated cells cells to mea-

sure spontaneous mutation frequency and plating efficiency. As soon as the liquid

is absorbed, overlay each plate with 10ml of SC-ARG top agar cooled to 40 ° to

immobilize the cells. Incubate for 2-3 hr at 30 ° to allow for mutant expression, then

overlay plates containing 5 × 106 cells with 10ml of SC-ARG top agar containing

200/zg/ml canavanine sufate. Overlay plates for estimating survival with 10 ml

14 j. Jagger, "Introduction to Research in Ultraviolet Photobiology," p. 137. Prentice Hall, Englewood

Cliffs, NJ, 1967.

15 j. F. Lemontt and S. V. Lair,

Murat. Res.

93, 339 (1982).

[ 10] CLASSICAL MUTAGENESIS

TECHNIQUES

197

SC-ARG top agar without canavanine. Direct plating of mutagen treated cells on

SC-ARG + canavanine can kill a variable proportion of cells, because of the initial

existence of functional permease; pools of the preferentially incorporated arginine

may not always be adequate to offset canavanine toxicity. Measurement of the

induced frequency of canavanine resistant mutants in some standard strain, such as

$288C, provides a benchmark against which to determine results from other strains.

Synthetic dextrose complete medium contains, per liter, 1.67 g Difco (Detroit, MI)

yeast nitrogen base (without amino acids and ammonium sulfate), 5 g ammonium

sulfate, 20 gm dextrose, and such nutrilites as the strain requires (see below for

concentrations), solidified with 2% (plates) or 0.75% (overlay) agar.

Mutant Enrichment by Inositol Starvation

Selective killing of growing cells by starvation for inositol, and hence en-

richment of mutants unable to grow in the particular conditions used, was first

described

forNeurospora 16

and has since been developed for yeast. 12 A necessary

prerequisite is the presence of one or more

ino

mutations in the parent strain. Initial

studies 12 used an

ino1-13 ino4-8

double mutant, but a single mutant containing a

inol

deletion/disruption j7 is likely to be more convenient.

1. Mutagenize cells by one of the methods described above. Inoculate the

culture to be treated with a carefully subcloned strain: enrichment procedures

indiscriminately increase the frequency of all slow-growing cells, such as mito-

chondrial petites which can occur at high frequency in old cultures. If independent

mutations at any given locus are needed, distribute aliquots of the mutagenized

cells to different tubes before outgrowth, and carry out the procedure on each in

parallel.

2. Allow the treated cells to recover from the mutagen damage and to express

mutations by resuspending them in YPD or other appropriate medium at a concen-

tration of about 5 x 105 cells/ml, grow the culture to no more than 107 cells/ml, and

collect the cells by centrifugation: it is important to harvest exponential-phase cells.

3. Wash the cells in prewarmed prestarvation medium, resuspend in this

medium at a concentration of between 1 x 104 and 1 x l06 cells/ml, and incubate

for 3-4 hr under conditions that will stop the growth of the mutants for which en-

richment is desired. If histidine auxotrophs are sought, for example, prestarvation

medium is synthetic complete medium that contains inositol but not histidine. For

temperature-sensitive mutations, prestarvation medium is any complete medium

containing inositol, but the incubation is carried out at 35 °.

16 H. E. Lester and S. R. Gross,

Science

139, 572 (1959).

t7 M. Dean-Johnson and S. A. Henry,

J. Biol. Chem.

264, 1274 (1989).

198 MAKING MUTANTS [ 10l

4. Wash cells twice in prewarmed starvation medium and resuspend at a con-

centration of no more than 5 x 106 cells/ml. Starvation medium is prestarvation

medium lacking inositol. Incubate for 24 hr at 35 ° to enrich for temperature-

sensitive mutants; otherwise incubate at 30 °. At 30 °, cells begin to die after 5-6 hr,

and eventually only about 0.1-1% should remain viable.

5. Plate cells on any suitable permissive medium and incubate under per-

missive conditions to obtain well-separated colonies. Rich medium containing a

nonfermentable carbon source (e.g., YPG) can be used at this stage if selection

against petites is desirable.

6. Screen surviving clones for the desired mutant.

A second cycle of enrichment can be tried, but is usually not required when cells

are mutagenized. Solid medium can be used in place of liquid for the starvation

phase of the procedure, and surviving cells recovered from these plates by velveteen

replication.12 When this is done, the plating density needs to be adjusted to account

not only for inositol-less death, but also for the fact that only about 10% cells are

transferred by velveteen.

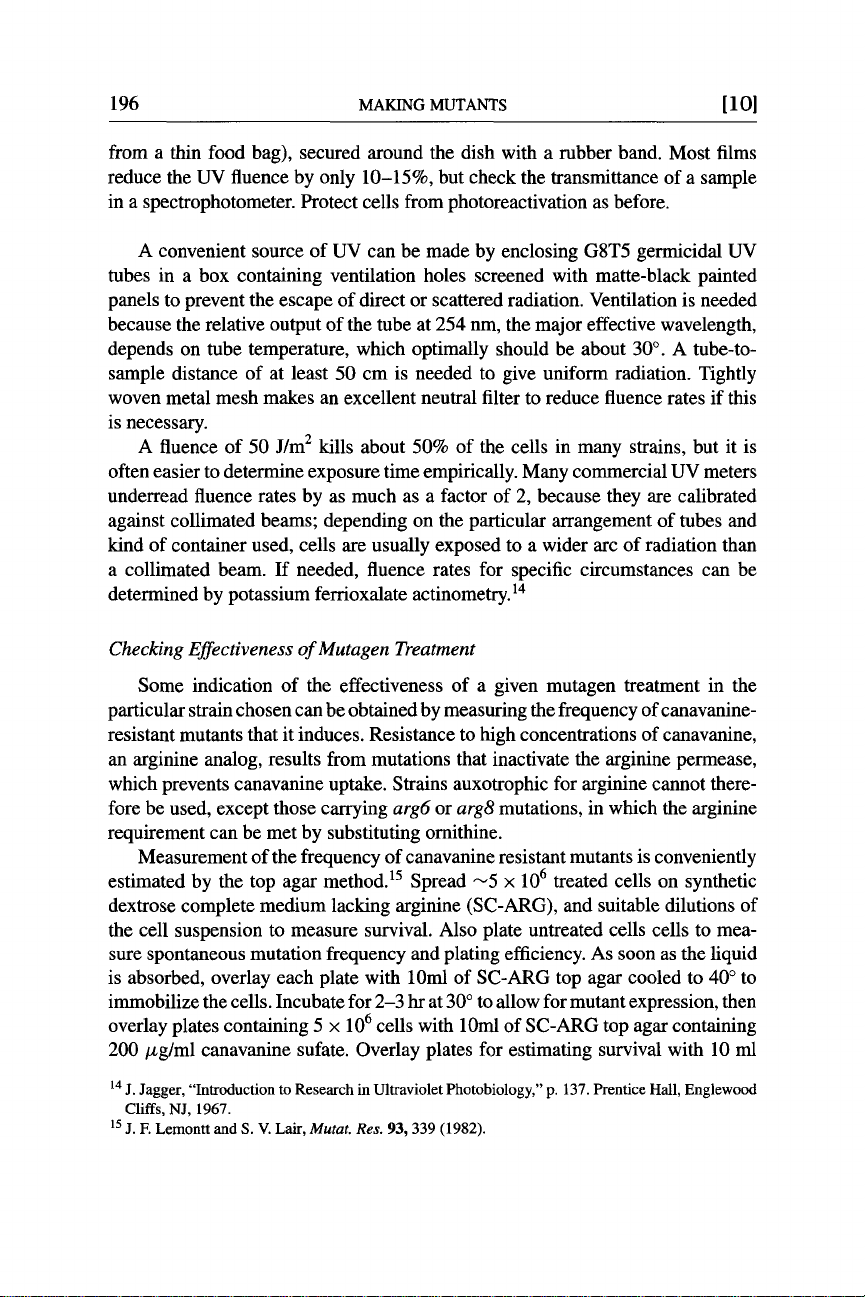

Inositol Starvation Medium per Liter

Ammonium sulfate 5 g

Potassium phosphate, monobasic 1 g

Magnesium sulfate 0.5 g

Sodium chloride 0.1 g

Calcium chloride 0.1 g

Boric acid 500/zg

Copper sulfate 40/zg

Potassium iodide 100/~g

Ferric chloride 200/zg

Manganese sulfate 400/~g

Sodium molybdate 200/zg

Zinc sulfate 400/zg

Biotin 2/zg

Calcium pantothenate 400/zg

Folic acid 2/zg

Niacin 400/zg

p-Aminobenzoic acid 200/zg

Pyridoxine hydrochloride 400/zg

Riboflavin 200/zg

Thiamin hydrochloride 400/zg

Dextrose 20 g

To prevent the selection of auxotrophs, the following nutrilites can be added

to the inositol starvation medium: adenine sulfate, uracil, L-arginine hydrochloride,

[

1 1] POINT MUTATIONS IN CLONED GENES

199

L-histidine hydrochloride, L-methionine, L-tryptophan, each at 20 mg/liter;

L-isoleucine, L-leucine, L-lysine hydrochloride, L-tyrosine, each at 30 mg/liter;

L-phenylalanine, 50 mg/liter; L-valine, 150 mg/liter; L-aspartic acid, L-glutamic

acid, each at 100 mg/liter; L-homoserine, L-threonine, each at 200 mg/liter;

L-serine, 375 mg/liter. The last five nuWilites can often be omitted from the medium,

since auxotrophs with these requirements are rare.

Synthetic prestarvation medium is inositol starvation medium plus 2000/zg of

inositol. Starvation medium can also be made using Difco vitamin-free yeast nitro-

gen base (16.9 g/liter), but this provides 1% dextrose and also histidine, methionine,

and tryptophan. YPD medium is 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% dextrose.

YPG medium is similar, but with 2% glycerol (v/v) replacing the dextrose.

[ i i] Introduction of Point Mutations into Cloned Genes

By BRENDAN CORMACK and IRENE CASTA/~IO

Introduction

In the 10 years since the publication of Guide to Yeast Genetics and Molecular

Biology, 1 the availability of the complete yeast genomic sequence and more re-

cently of a set of haploid and diploid strains deleted for each of the yeast open

reading frames (ORFs) has dramatically affected the practice of classical yeast

genetics. Researchers are likely to choose, when possible, to use the collection of

ORF deletion strains as the default for genetic screens and selections. There are, of

course, limitations to the utility of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae deletion collec-

tion: global methods of mutagenesis will still be required for genetic analysis of

strains with backgrounds different than the type strains used for the S. cerevisiae

knockout project 2,3 (see chapters 12 and 13). Equally, the genetic analysis of es-

sential genes still relies largely on the generation of point mutations in those genes

(for an alternative approach, exploiting repressible promoters and ubiquitin desta-

bilization of the gene product, see a recent review by Varshavsky. 5 This chapter

first discusses briefly the principle of the plasmid shuffle technique which is critical

to the generation and analysis of point mutants in essential genes. Second, two ap-

proaches to in vitro generalized mutagenesis of cloned yeast genes are discussed.

I C. Guthrie and G. R. Fink (eds.),

Methods Enzymol,

194 (1991).

2N. Backman, M. Biery, J. D. Boeke, and N. L. Craig,

Methods EnzymoL

350, [13], 2002 (this

volume).

3 A. Kumar, S. Vidam, and M. Snyder,

Methods EnzymoL

350, [12], 2002 (this volume).

4 Deleted in proof.

5 A. Varshavsky,

Methods Enzymol.

327, 578 (2000).

Copyright 2002, Elsevier Science (USAI.

All rights reserved.

METHODS IN ENZYMOLOGY, VOL. 350 0076-6879/02 $35.00

Bấm Tải xuống để xem toàn bộ.