Practice Tests for the

gifted

Compiler: Ngo Minh

Chau

1

PRACTICE TEST 1

I. LISTENING

Part 1: You will hear a radio report about Ocean Biodiversity. Complete the sentences, using NO

MORE THAN TWO WORDS for each answer.

Ocean Biodiversity

Biodiversity hotpots

areas containing many different species

important for locating targets for (1)

at first only identified on land

Boris Worm, 2005

identified hotspots for large ocean predators, e.g. sharks

found that ocean hotspots:

- were not always rich in (2)

- had higher temperatures at the (3)

- had sufficient (4) in the water

Lisa Balance, 2007

looked for hotspots for marine (5)

found these were all located where ocean currents meet

Census of Marine Life

found new ocean species living:

- under the (6)

- near volcanoes on the ocean floor

Global Marine Species Assessment

Want to list endangered ocean species, considering:

- population size

- geographical distribution

- rate of (7)

Aim: to assess 20,000 species and make a distribution (8) for

each one

Recommendations to retain ocean biodiversity

increase the number of ocean reserves

establish (9) corridors (e.g. for turtles)

reduce fishing quotas

catch fish only for the purpose of (10)

Part 2: Listen to the information about London Heathrow Airport. Write NO MORE THAN

THREE WORDS for each answer.

1. Which terminal takes British Airways flights to Philadelphia?

2. How long does it take to travel by coach between terminals?

3. Where do you go if you do not have a boarding pass for a connecting flight?

4. How many passengers can a taxi carry?

5. How long is the journey on the underground?

Part 3: You are going to listen to a conversation. As you listen, indicate whether the following

statements are true or not by writing.

T for a statement which is true; F for a statement which is false;

N if the information is not given.

1. Napoleon controlled all of Europe at one time

2. Austria and Russia fought fiercely against Napoleon, but England did not.

3. Napoleon lost most of his soldiers when he attacked England.

4. Napoleon died before he reached the age of fifty-two.

5. He was married when he was very young.

Part 4: You will hear a radio discussion about writing a novel. For questions 1-5, choose the answer

(A, B, C or D) which fits best according to what you hear.

1. What does Louise say about Earnest Hemingway‘s advice to writers?

A. It‘s useful to a certain extent. B. It applies only to inexperienced novelists.

C. It wasn‘t intended to be taken seriously. D. It might confuse some inexperienced novelists.

2. Louise says that you need to get feedback when you .

A. have not been able to write anything for some time

B. are having difficulty organizing your ideas

C. are having contrasting feelings about what you have written

D. have finished the book but not shown to anyone

3. Louise says that you should get feedback from another writer because _ .

A. it is easy to ignore criticism from people who are not writers

B. another writer may be kinder to you than friends and relatives

C. it is hard to find other people who will make an effort to help you

D. another writer will understand what your intentions are

4. What does Louise regard as useful feedback?

A. a combination of general observations and detailed comments

B. both identification of problems and suggested solutions

C. comments focusing more on style than on content

D. as many points about strengths as weaknesses

5. What does Louise say about the people she gets feedback from?

A. Some of them are more successful than her. B. She doesn‘t only discuss writing them.

C. She also gives them feedback on their work.

D. It isn‘t always easy for her to get together with them.

II. LEXICO - GRAMMAR

Part 1: Choose the word or phrase (A, B, C or D) which best completes each sentence.

1. I was to believe that she was a representative of the Labour Party.

A. declared B. carried C. led D. explained

2. It has been kept for about ten years that the minister‘s son committed a crime.

A. unaware B. secret C. mystery D. obscure

3. One could see with the eye that there was a lighthouse on the promontory.

A. naked B. sole C. nude D. shut

4. These two items don‘t differ much. The is even more apparent when you put them

together.

A. similarity B. likelihood C. coincidence D. analogy

5. Your rude behavior was an to the host and his wife. I don‘t think they will ever invite us to

their home again.

A. abuse B. insult C. injury D. aversion

6. For almost fifty years, the citizens of this country were from travelling abroad unless they

were politicians.

A. suspended B. rejected C. averted D. forbidden

7. I wouldn‘t their position in the market. They may appear to be very influential one day in

the future.

A. undertake B. underestimate C. underwrite D. undercharge

8. We can‘t admit a person who hasn‘t the required number of points at the entrance

examination.

A. scored B. assessed C. settled D. qualified

9. he delivers the report, it will be sent to the headquarters.

A. On the point B. At once C. Immediately D. Soon enough

10. The most probable for your chronic headache is lack of good rest.

A. factor B. background C. origin D. reason

11. This cheese isn‘t fit for eating. It‘s all over after lying in the bin for so long.

A. rusty B. mouldy C. spoiled D. sour

12. I cannot think of the correct answer. Could you drop me a small please?

A. tip B. idea C. hint D. word

13. It was time we went home after having spent the whole afternoon in the neighbor‘s

garden.

A. only B. just C. near D. about

14. Why not ask the tailor to shorten the jacket a little unless you don‘t want it to perfectly

with the trousers?

A. go B. do C. make D. suit

15. Studs was only the boy‘s . His real name was William.

A. label B. nickname C. identity D. figure

16. It‘s interesting how the rumour about my promotion began to .

A. progress B. spread C. publicize D. emit

17. What we saw was absolutely unusual. Crowds of people from all four of the world were

cheering the arrival of the astronauts.

A. corners B. edges C. spots D. places

18. Mr. Henson‘s bitter comments on the management‘s mistakes gave to the conflict which

has already lasted for four months.

A. cause B. ground C. goal D. rise

19. Numerous have prevented us from going to the lakeside again this year.

A. inhibitions B. deterrents C. impairments D. adversities

20. That tall fair woman me of my mother.

A. reminds B. remembers C. reminisces D. recalls

Part 2: Complete the following sentences with the words given in the brackets. You have to

change the form of the word.

Obsessed with your inbox

It was not so long ago that we dealt with colleagues through face-to-face (0) interation

(Interact) and with counterparts and customers by phone or letter. But the world of communication

has (1) undergone (go) a dramatic transformation, not all for the good. Email, while (2)

undoubtedly (doubt) a swift means of communication providing your server is fully (3)

functional (function) and that the address you have contains no (4)

inaccuracies (accurate) has had a (5) significant

(signify) effect on certain people‘s behavior, both at home and in business. For

these people, the use of email has become (6) irresistibly (resist)

addictive to the extent that it is (7) threatening

(threat) their mental and physical health. Addicts spend their day (8)

compulsively (compulsion) checking for the email and have a (9)

tendency (tend) to panic if their server goes down. It is estimated that one in six people spend

four hours a day sending and receiving messages the equivalent to more than two working days a

week. The negative effect on (10) production (produce) is something employers are well

aware of.

Part 3: Identify 10 errors in the following passage and correct them.

1 Unlike many other species of turtle, the red-car terrapin is not rare. In fact, four to

2 five million hatchings are exported annually from American farms. About

3 200,000 are sold in the United Kingdom.

4 It is ranked that as many as 90 per cent of the young terrapins die in their

5 first year because of the poor conditions in which they are kept. Those which

6 survive may live for 20 years and arrive the size of a dinner plate. At this staging

7 they require a large tank with heat and specialized lightning.

8 Terrapins carry salmonella bacteria which can poison people. This is why

9 the sale of terrapins was banished in the United States in 1975. They are still,

10 however, exported to the United Kingdom.

11 Modern turtles come from a very antique group of animals that lived over

12 200 million years ago. At this time dinosaurs were just beginning to establish

13 them.

14 Different types of turtles have interesting features: some box turtles are

15 known to have lived for over 100 years, since other species of turtles can remain

16 underwater for more than 24 hours. And the green turtle is the most prolific of all

17 reptiles, lying as many as 28,000 eggs each year.

18 If unwanted pet turtles are unreleased into the wild, many will die and

19 those which survive will threaten the lives of native plants and animal.

Part 4: Complete each of the following sentences with a suitable preposition or particle.

1. I‘m extremely pressed for.............money these days. Could you lend me a few pounds, please?

2. It‘s a great pity that those beautiful birds are vulnerable…to..........so much harm.

3. Tom hasn‘t attended classes for about two months and consequently he is rather..................done with

his lesson?

4. Must you always be so envious of.............your cousin‘s toys?

5. Adam felt really sick at heart after his girlfriend had walked out.................on him.

6. It‘s ……worth……. any hope that the Italian champion will retain the title. Nobody‘s giving her

any chances this year.

7. It was me who Cindy used to take by..............her confidence. Yet, on this particular occasion she

refused to reveal her secret to anyone, even me.

8. It isn‘t so much fatigue as lack of commitment ………in…. finishing the task that makes you so

inoperative.

9. Michael showed his disgust…towards.the way he was treated by refusing to speak to anyone.

10. I know Pete‘s conduct was intolerable, but don‘t be too hard…on.........him

III. READING

Part 1: Complete the following article, using only ONE word for each space. (10 pts)

The Legend of the Root

Ginseng is one of the great mysteries of the east. Often referred to as the

―

elixir of

life

‖

, its widespread use in oriental medicine has led to many myths and legends building up around

this remarkable plant. Ginseng has featured (1) as an active ingredient in oriental

medical literature for over 5,000 years. Its beneficial effects were, at one time, (2)

so widely recognized and praised that the root was said to (3) its

worth its weight in gold.

(4) despite the long history of ginseng, no one fully knows how it works. The

active part of the plant is the root. Its full name is Panax Ginseng – the word Panax, (5) like

the

wor

d panacea, coming from the

Gr

eece for

―

all healing

‖

. There is growing interest by western

scientists (6) in the study of ginseng. It is today believed that this remarkable plant

may (7) have beneficial effects in the treatment of many diseases (8)

that are difficult to treat with synthetic drugs.

Today, ginseng is no longer a myth or a legend. Throughout the world it is becoming widely

recognized that this ancient herb holds the answer to relieving the stresses and ailments of modern

living. It is widely used for the treatment of various ailments (9) such as arthritis,

diabetes, insomnia, hepatitis and anaemia. However, the truth behind (10) how _

ginseng works still remains a mystery. Yet its widespread effectiveness shows that the remarkable

properties are more than just a legend.

Part 2: Read the text below and decide which answer (A, B, C or D) best fit each gap.

Secretaries

What‘s in a name? In the case of the secretary, or Personal Assistant (PA), it can be something

rather surprising. The dictionary calls a secretary

―

anyone who (1) correspondence,

keep

s

records and does clerical work for others‖. But while this particular job definition looks a

bit (2)

, the word‘s original meaning is a hundred times more exotic and perhaps more appropriate.

The word itself has been with us since the 14

th

century and comes from the mediaeval Latin word

se

c

retarius

meaning

―

something

hidden‖

. Secretaries started out as those members of staff

with

knowledge hidden from others, the silent ones mysteriously (3)

organizations. Some years ago

―

something hidde

n‖

probably meant (4) _

the secret machinery of

out of sight, tucked

away with all the other secretaries and typists. A good secretary was an unremarkable one,

efficiently (5) orders, and then returning mouse-like to his or her station behind the

typewriter, but, with the (6) of new technology, the job effectively upgraded itself and the

role has changed to one closer to the original meaning. The skills required are more demanding and

more technical. Companies are (7) that secretarial staff should already be (8) trained

in, and accustomed to working with, a (9) of word processing packages. The professionals in

the (10) business point out that nowadays secretarial staff may even need some management

skills to take on administration, personnel work and research.

1. A. deals B. handles C. runs D. controls

2. A. elderly B. unfashionable C. outdated D. aged

3. A. operating B. pushing C. functioning D. effecting

4. A. kept B. covered C. packed D. held

5. A. satisfying B. obeying C. completing D. minding

6. A. advent B. approach C. entrance D. opening

7. A. insisting B. ordering C. claiming D. pressing

8. A. considerably B. highly C. vastly D. supremely

9. A. group B. collection C. cluster D. range

10. A. appointment B. hiring C. recruitment D. engagement

Part 3: Choose the correct answer.

Space pilots, vertical farmers and body part makers are just some of the jobs the next generation

could be doing in 20 years‘ time.

This is what expert future researchers came up with in a study on ‗The shape of jobs to come‘ –

which analysed future trends such as population growth and climate change alongside developments

in science and technology to create a list of potential jobs under the ongoing digital revolution that

will prompt a need for virtual lawyers, virtual clutter organisers, waste data handlers and personal

branders.

The foresight study by UK-based Fast Future, a global futures research and consulting firm,

paints an interesting picture of the jobs we could be doing by 2030:

Safeguarding the environment will be more prominent than ever, with climate change reversal

specialists, vertical farmers and weather modification police all attempting to deal with the impact

of climate change and population growth;

Old age wellness managers, memory augmentation surgeons and body part makers will be

needed to cope with an ageing society, enhancing the quality of life for a population where life

expectations could reach over 100; and

Breakthroughs in space travel will lead to people swapping the office for the final frontier as

space pilots, space architects and space tour guides.

Of the top 20 future jobs highlighted, a global survey of future thinkers revealed:

The British are keen to ‗boldly go‘ – with space jobs the most aspirational, alongside nano-

medics and memory augmentation surgeons;

Cars, crops and older people could be the focus for many in tomorrow‘s workforce, with old age

wellness managers, vertical farmers and alternative vehicle developers creating the most jobs;

For those looking to make the big bucks, nano-medicine, memory augmentation surgery and

virtual law are the areas you should be telling your kids about, with the Fast Future panel predicting

that these will be the best paid jobs in 2030;

Future jobs that benefit society will be the most popular, with climate change reversal specialist,

social ‗networking‘ worker and old age wellness manager topping the poll in the popularity stakes;

and

Work won‘t all be ‗fun‘ in the future, with the least exciting jobs being weather modification

police to protect us from cloud theft, quarantine enforcers preventing the spread of diseases and

waste data handlers who will dispose of our electronic mess.

―

The list of future jobs highlights the vast array of exciting things today‘s schoolchildren could

be doing in 20 years‘ time, all made possible by fields of science and innovation in which Britain

has real expertise,‖ said Fast Future chief executive officer Rohit Talwar, who conducted the study.

―

We‘re crossing the boundaries between science fiction and reality, and what we‘re seeing in

the movies are becoming genuine career opportunities. Alongside futuristic sounding high-tech jobs

at the cutting edge of scientific fields – like nano-medicine, the jobs of the future also include

very

‗high touch‘ occupations, such as old age wellness managers, narrowcasters and personal branders.‖

1. It can be inferred from the text that expert future researchers .

A. create potential jobs B. study future jobs

C. reverse future trends D. analyse waste data

2. According to Fast Future, the next generation could be doing all of the following jobs except

.

A. space plots B. virtual farmers C. virtual lawyers D. nano-medics

3. The

wor

d

―

impact

‖

is closest in meaning to .

A. size B. affection C. affluence D. effect

4. It can be inferred from the text that all of the following is true except .

A. We will have to deal with an ageing society because human beings will live longer in 20 years‘

time.

B. Environmental pollution will be less of a problem for us in 20 years‘ time.

C. Human beings will be able to travel with ease in space thanks to breakthrough scientific and

technological advancements.

D. We will stop producing science fiction movies because all what we see in them will have come

true.

5. The word

―

swappin

g

‖

is closest in meaning to _ .

A. relocating B. selling C. renovating D. leasing

6. According to the text, which of the following jobs will be paid?

A. vertical farmers B. old age wellness managers

C. nano-medics D. space architects

7. The word

―

aspiration

al

‖

is closest in meaning to .

A. exciting B. influential C. rewarding D. useful

8. According to the text, which of the following jobs will be the least popular?

A. climate change reversal specialists B. alternative vehicle developers

C. waste data handlers D. personal branders

9. According to the text, weather modification police .

A. stop epidemic spread B. fight harmful clouds

C. reverse climate change D. arrest cloud bandits

10. What is the best title for the text?

A. The best paid jobs in 2030 B. Breakthrough in research and technology in 2030

C. Trends related to job hunting in 2030 D. Career opportunities in 2030

Part 4: Read the following passage and answer questions 1-10.

SO YOU WANT TO BE AN ACTOR?

A.

A

risky job

If you tell someone that you want to make a career as an actor, you can be sure that

within two minutes the word

―

risky

‖

will come up. And, of course, acting

is

a

very risky career – let there be more mistakes about that. The supply of actors is far

greater

than the demand for them.

Practice Tests for the

gifted

Compiler: Ngo Minh

Chau

8

B.

Once you choose to become an actor, many people who you thought were your closest

friends will tell you

―

You‘re crazy

‖

, though some may react quite differently. No two

people will give you the same advice. But it is a very personal choice you are making.

C.

The

road to

success

There are no easy ways of getting there – no written examinations to pass, and no

absolute guarantee that when you have successfully completed your training you will

automatically make your way in the profession. It‘s all a matter of luck plus talent. Yet

there is a demand for new faces and new talent, and there is always the prospect of

excitement, glamour and the occasional rich reward.

D.

I have frequently been asked to define this magical thing called talent, which everyone

is looking out for. I believe it is best described as natural skill plus imagination – the

latter being the most difficult quality to access. And it has a lot to do with the person‘s

courage and their belief in what they are doing and the way they are putting it across.

E.

Where does the desire to act come from? It is often very difficult to put into words

your own reasons for wanting to act. Certainly, in the theatre the significant thing is

that moment of contact between the actor on the stage and a particular audience. And

making this brief contact is central to all acting, wherever it takes place – it is what

drives all actors to act.

F.

If you ask actors how they have done well in the profession, the response will most

likely be a shrug. They will know certain things about themselves and aspects of their

own technique and the techniques of others. But they will take nothing for granted,

because they know that they are only as good as their current job, and that their fame

may not continue.

G.

Disappointment is the greatest enemy of the actor. Last month you may have been out

of work, selling clothes or waitressing. Suddenly you are asked to audition for a part,

but however much you want the job, the truth is that it may deny you. So actors tend

not to talk about their chances. They come up with ways of protecting themselves

against the stress of competing for a part and the possibility of rejection.

H.

Essentia

l

qualities

Nobody likes being rejected. And remember that the possibility is there from the very

first moment you start going in for parts professionally. You are saying that you are

available, willing and hopefully, talented enough for the job. And, in many ways, it‘s

up to you, for if you don‘t care enough, no one will care for you.

For questions 1-5, choose the correct heading for paragraphs B-G from the list of headings

below. Write the correct numbers (i-viii) in the corresponding numbered boxes.

i. Dealing with unpleasant feelings

ii. What lies behind the motive?

iii. Your own responsibility

vi. Reactions toward the job

vii. Uncertainties about the future

1. Paragraph B vi 2. Paragraph D iii 3. Paragraph E ii

4. Paragraph F vii 5. Paragraph G i

For questions 6-10, complete the sentences below by writing NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS

taken from the reading passage.

6. Every actor cares about the contract between himself and a group of audience.

7. Talent is characterized as a combination of skills and imagination .

Practice Tests for the

gifted

Compiler: Ngo Minh

Chau

Television

Computer

9

8. What the actor has to deal with very often is the sense of disappointment - chances

for a part are narrow no matter how much you like the part.

9. If actors become famous, it is very likely that they will be as a return.

10. The rejection t is very likely to happen as soon as you start your profession

and it is very stressful.

IV. WRITING

Part 1: Read the following extract and use your own words to summarize it. Your summary

should be about 80 words long. You MUST NOT copy the original.

A tertiary education is an investment for your future. It is giving three to five years of your life

towards what you will eventually do with your life and for many of you, your journey begins right

after O level. Therefore, you need to make this decision wisely. Here are some pointers to help you

make informed decisions about the college you want to enrol in.

Before choosing a college, you should first know what you want to study. Check the list of

online colleges and universities for those that offer what you want and select the ones that meet

your requirement. You may also want to find out about the location of your campus. Would you

rather be close to home or do you want to be as far away and as independent as possible? It is also

best to find out as much as you can about housing arrangements before you decide on an institution

of higher learning to reduce any hassle later. Some colleges offer on-campus accommodation or

will help you look for outside accommodation. Last but not least, make sure you have the finances

to see you through your studies as college education can be expensive.

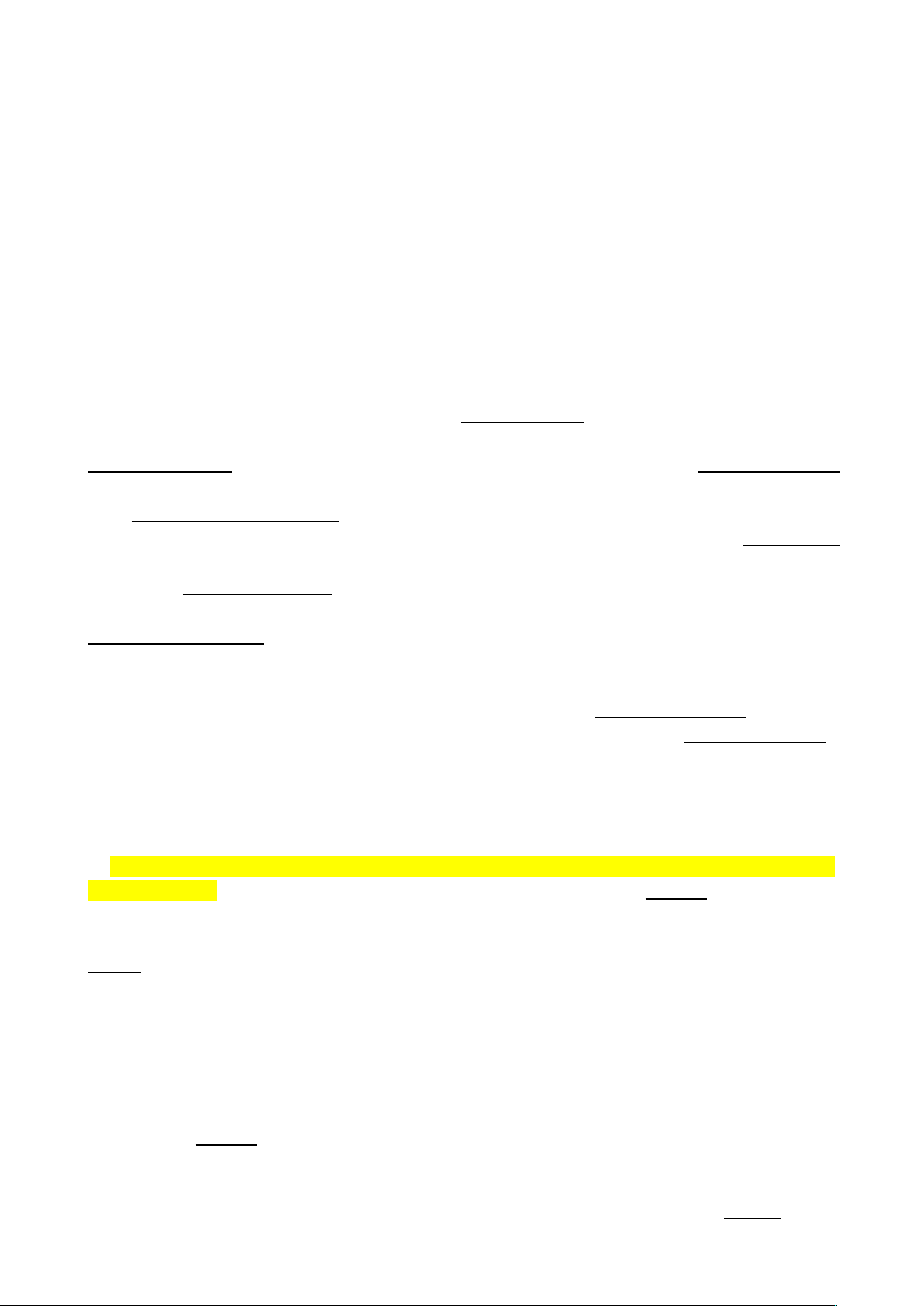

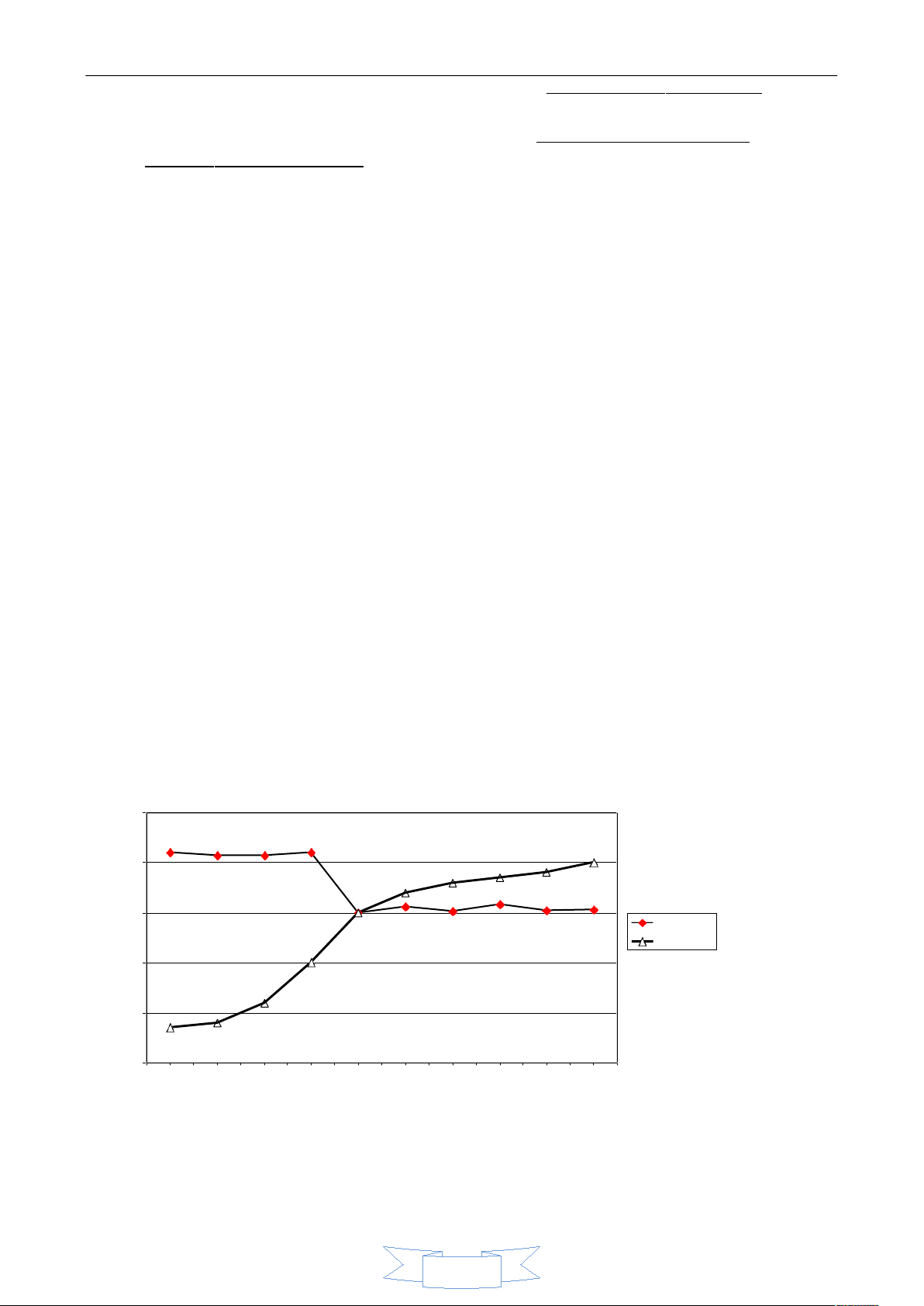

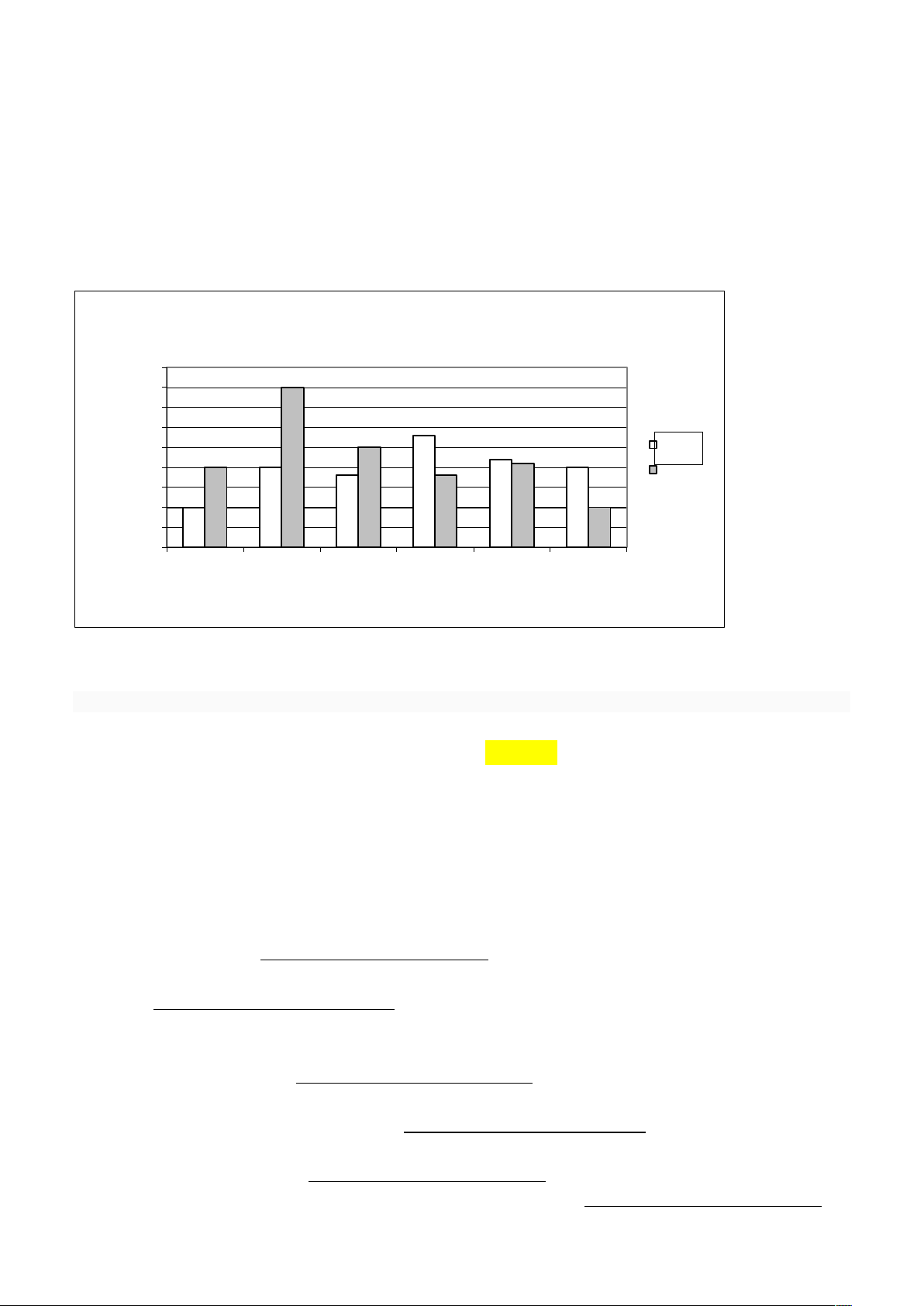

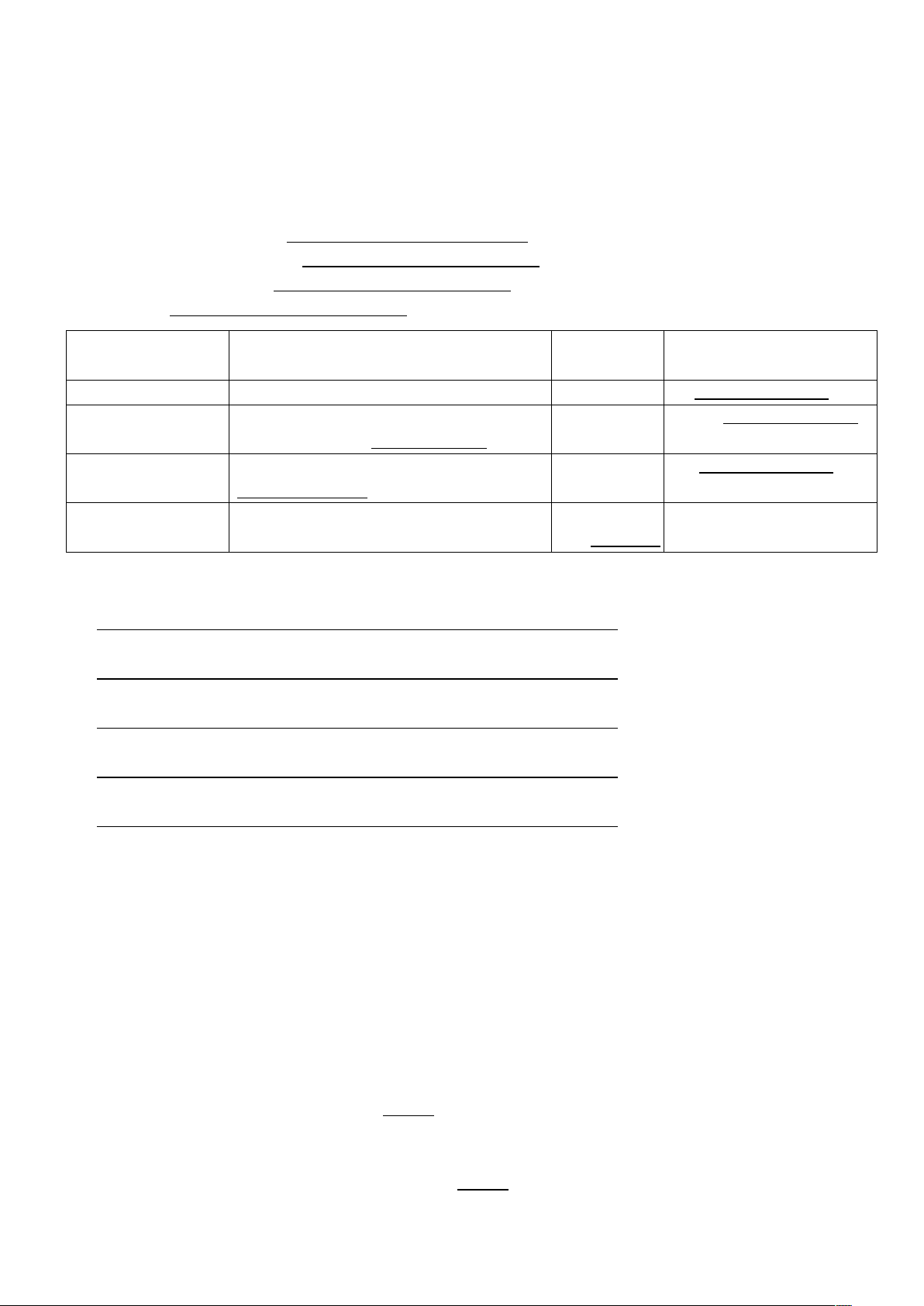

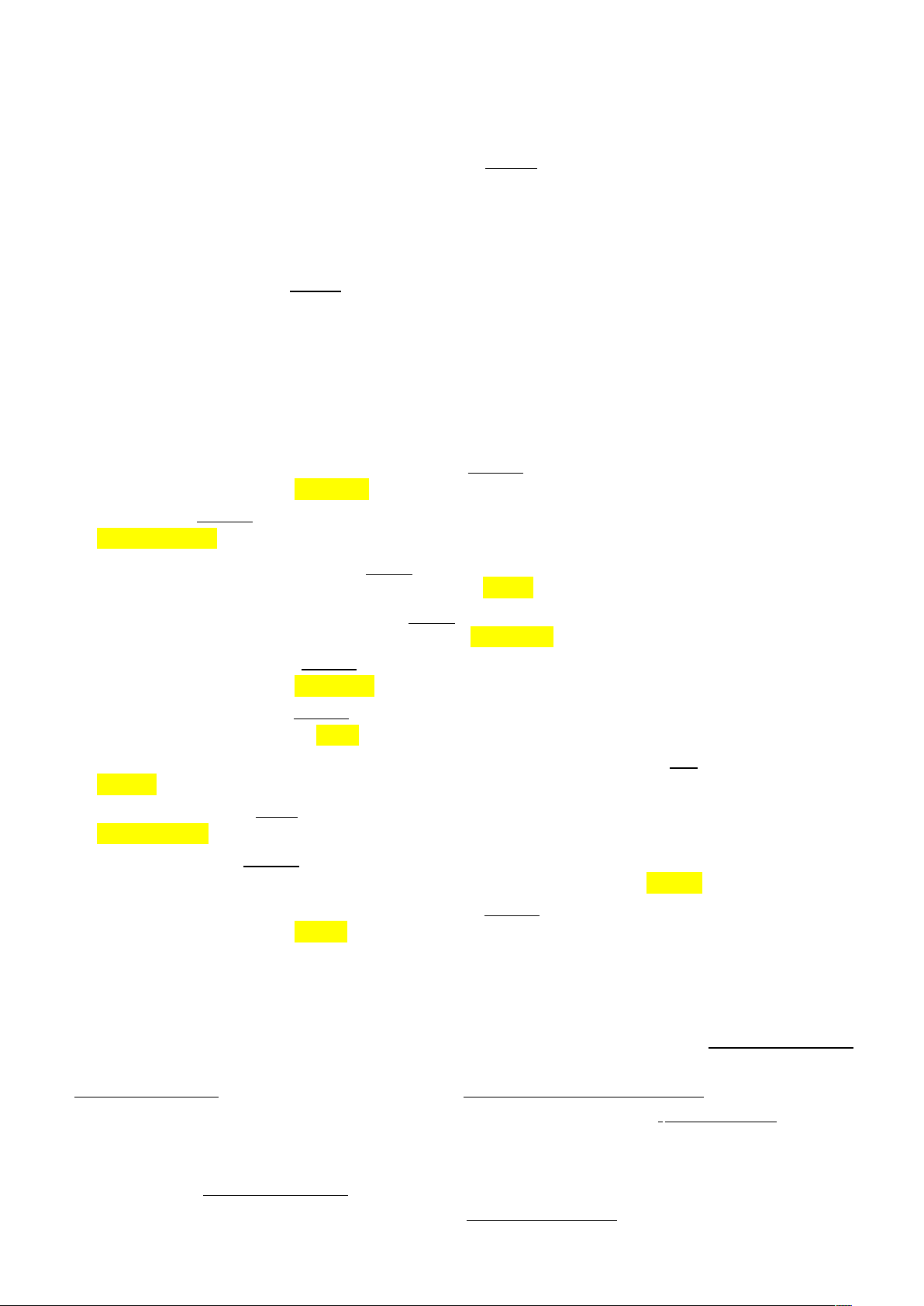

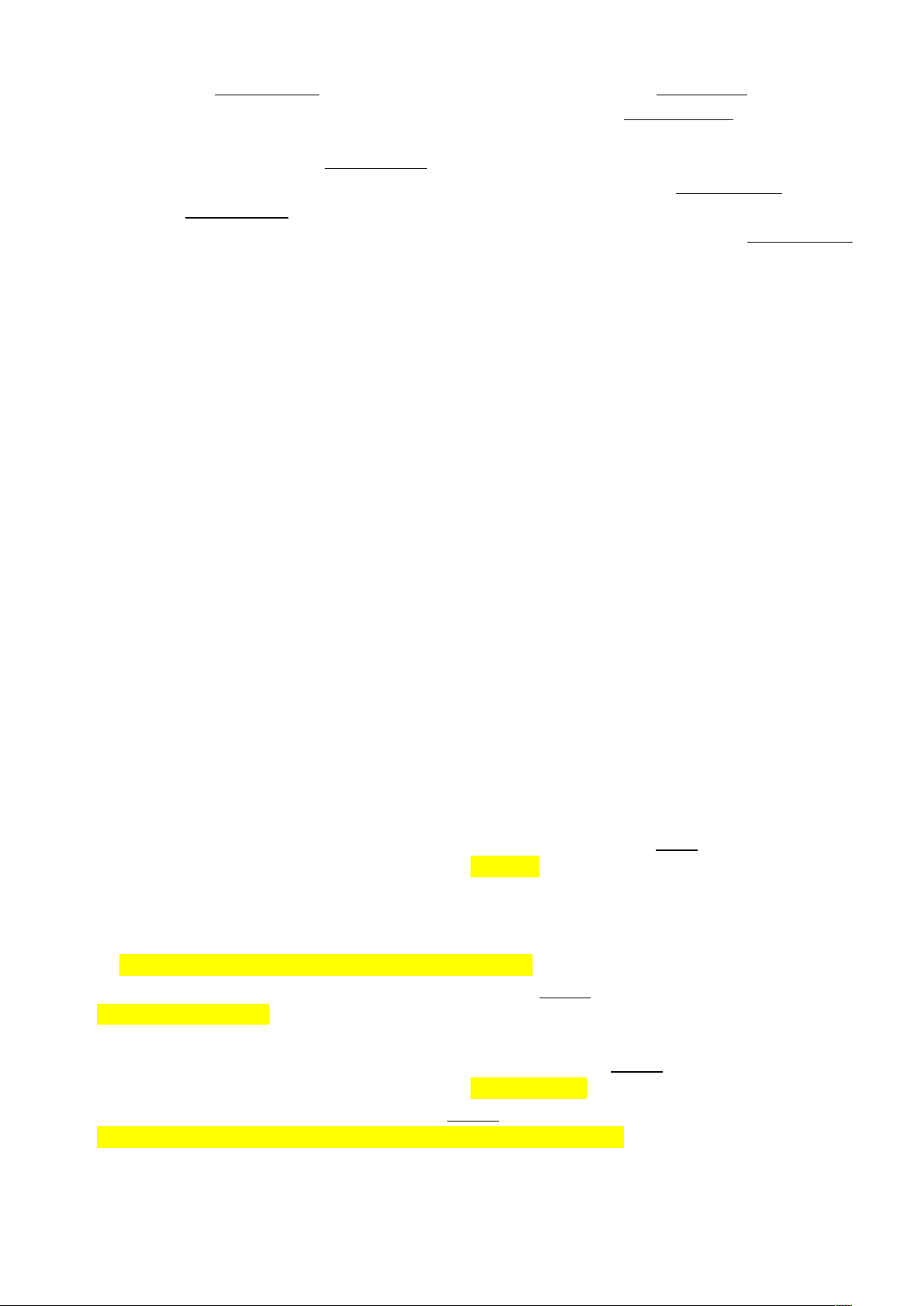

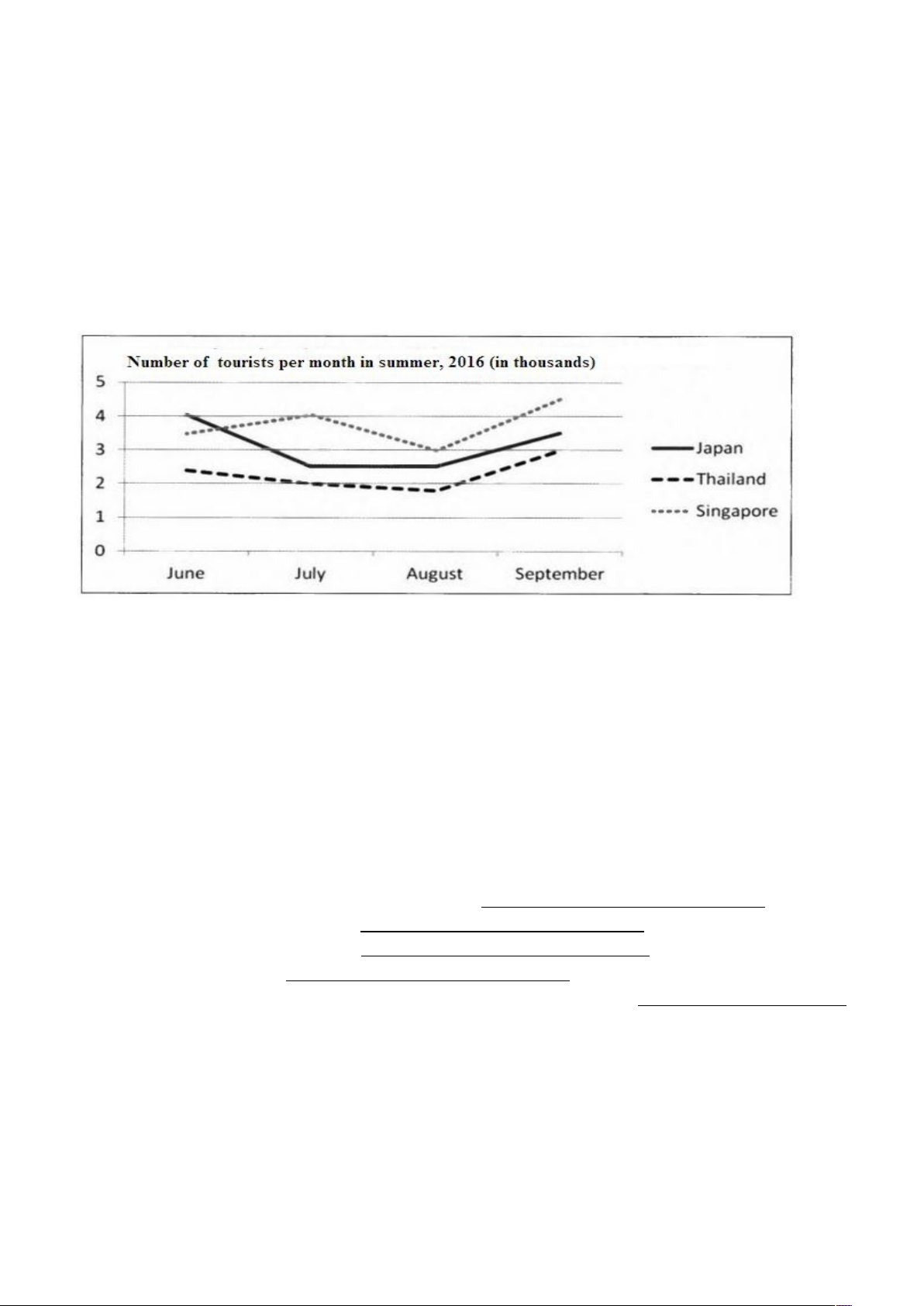

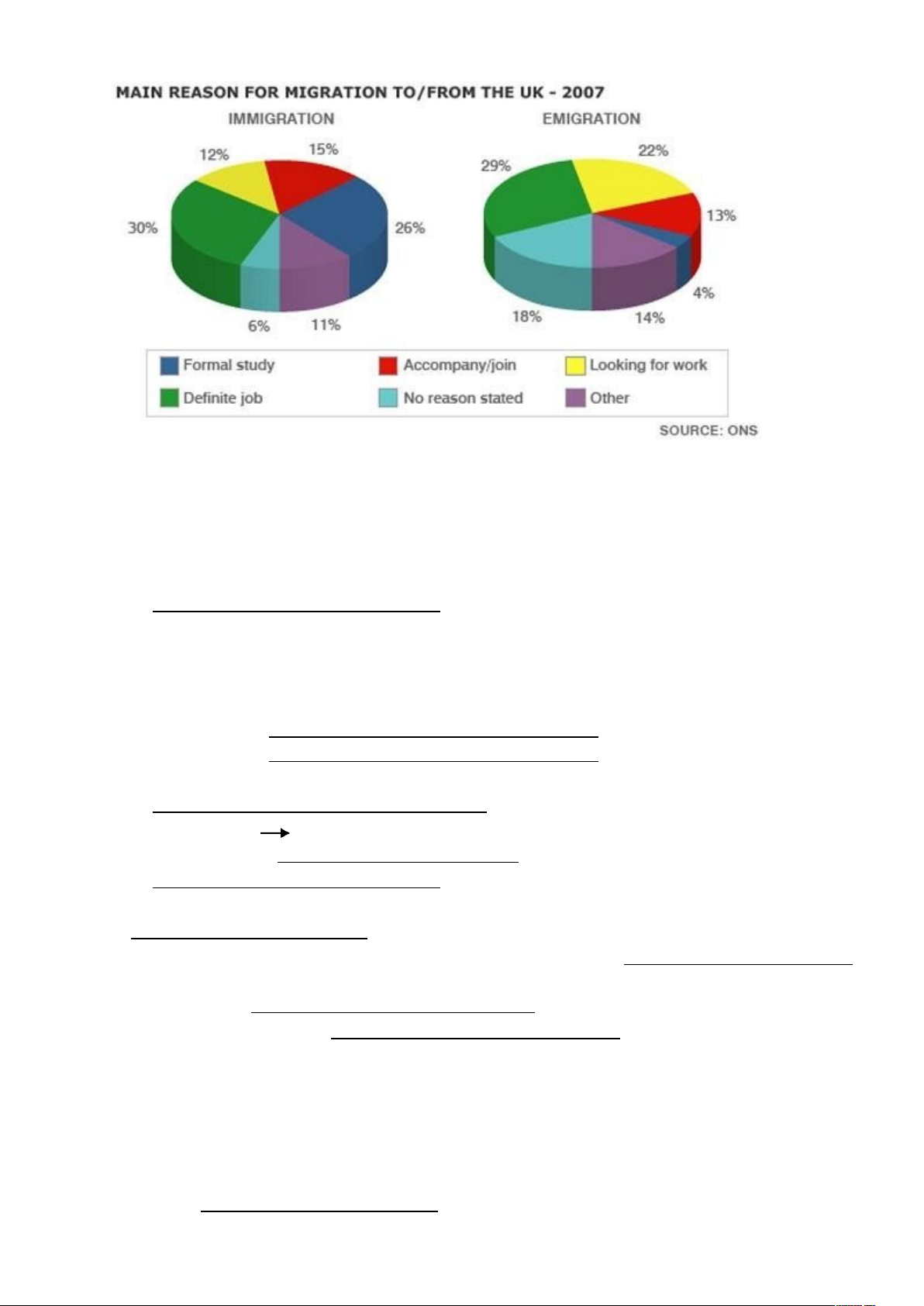

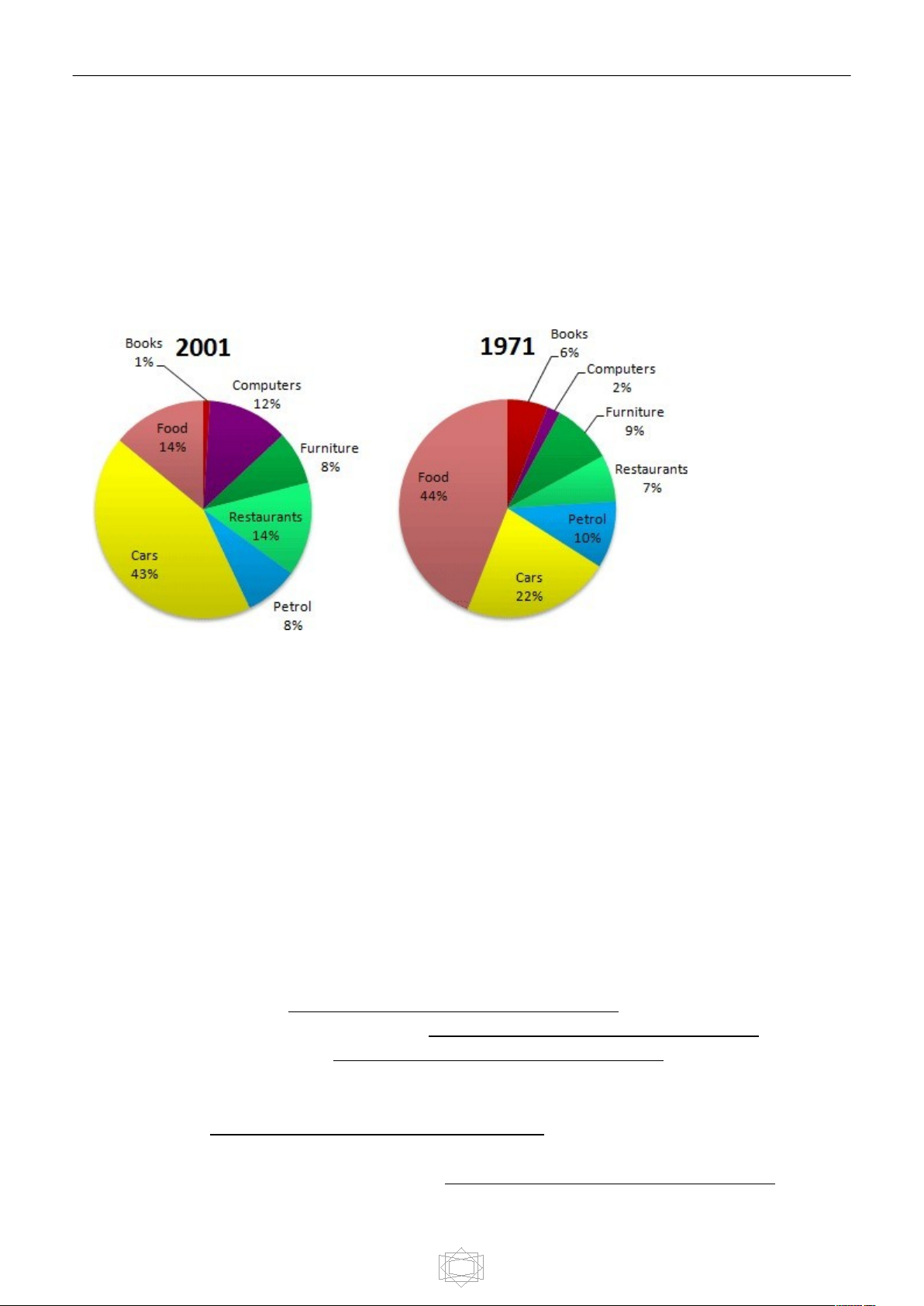

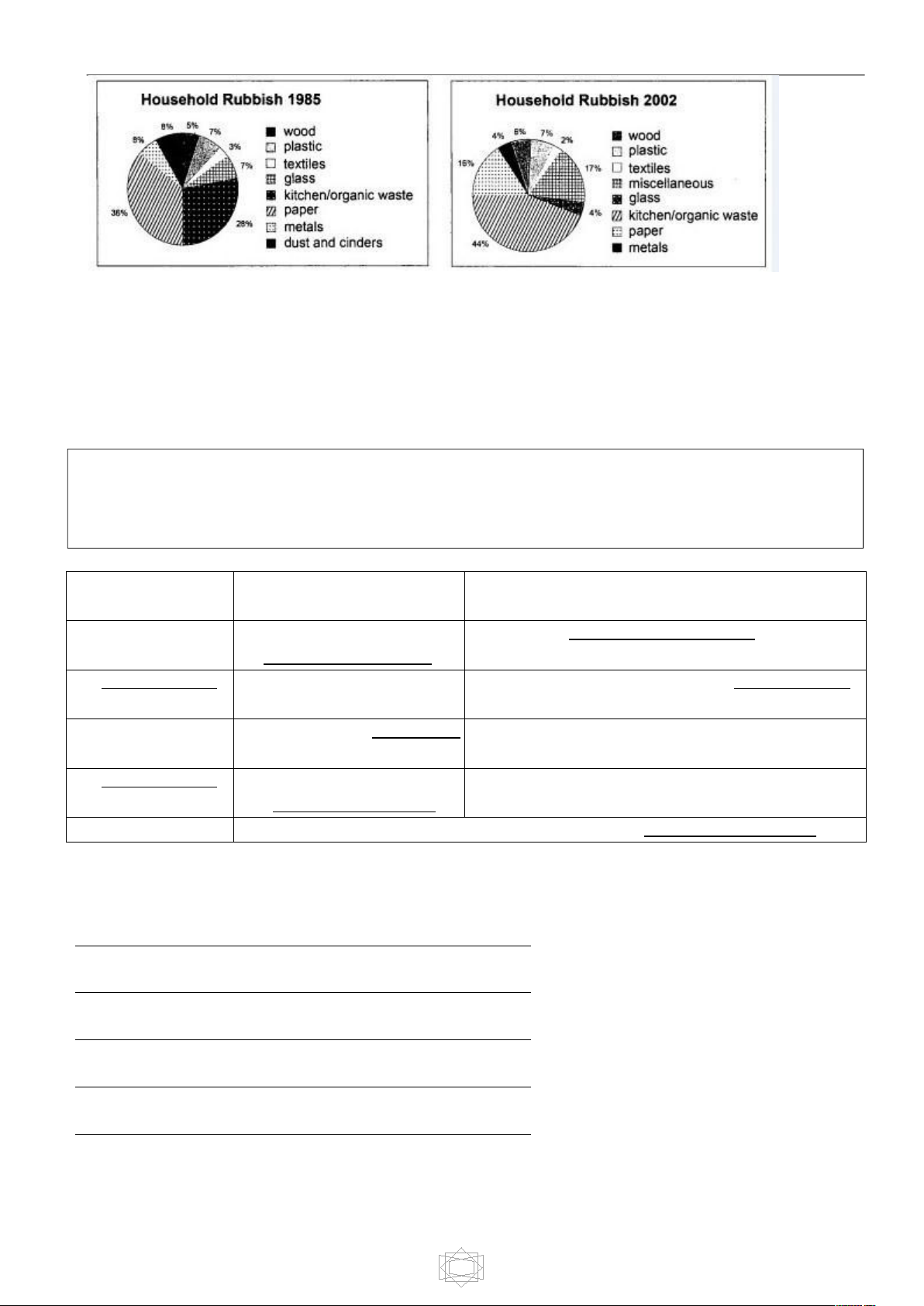

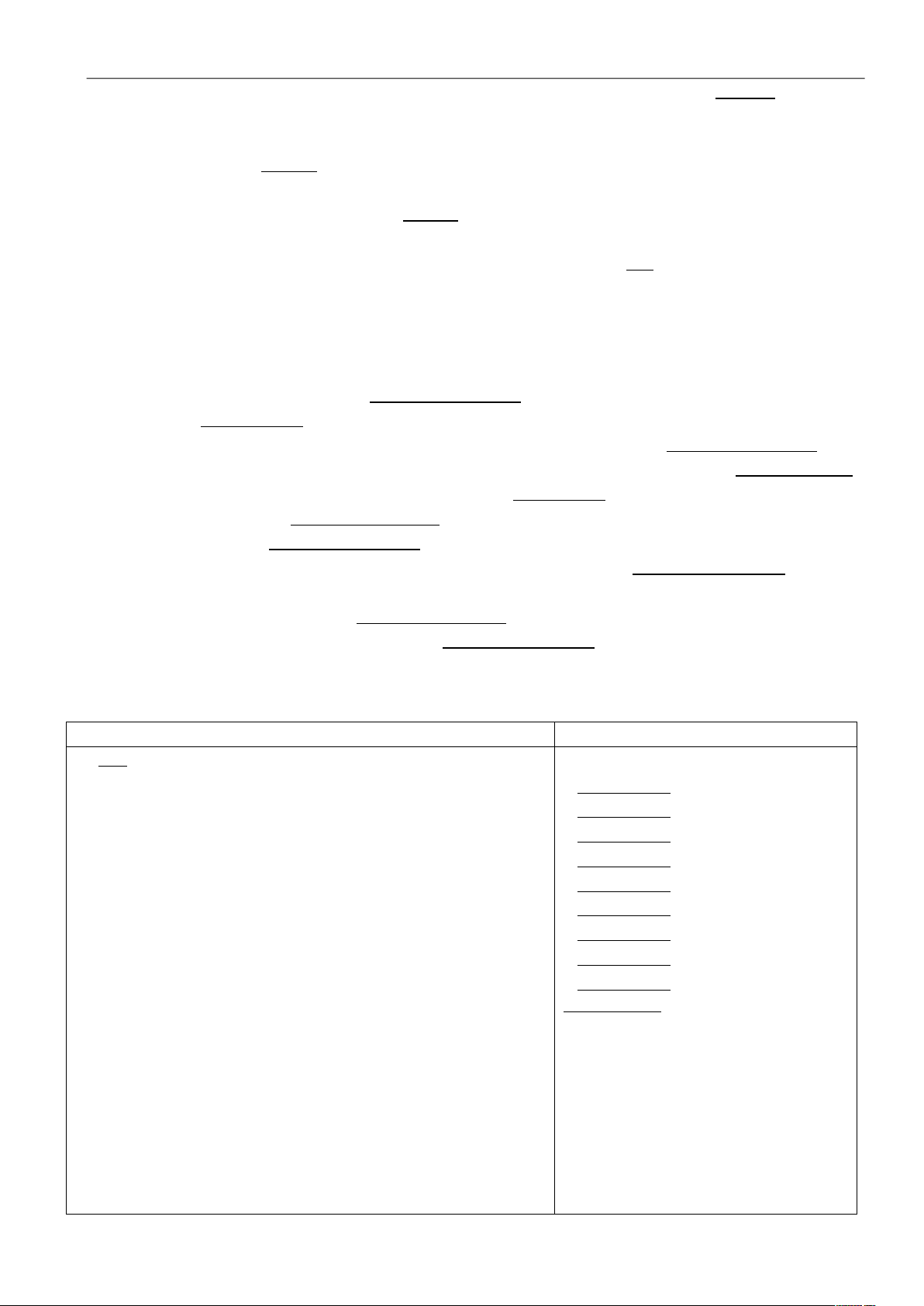

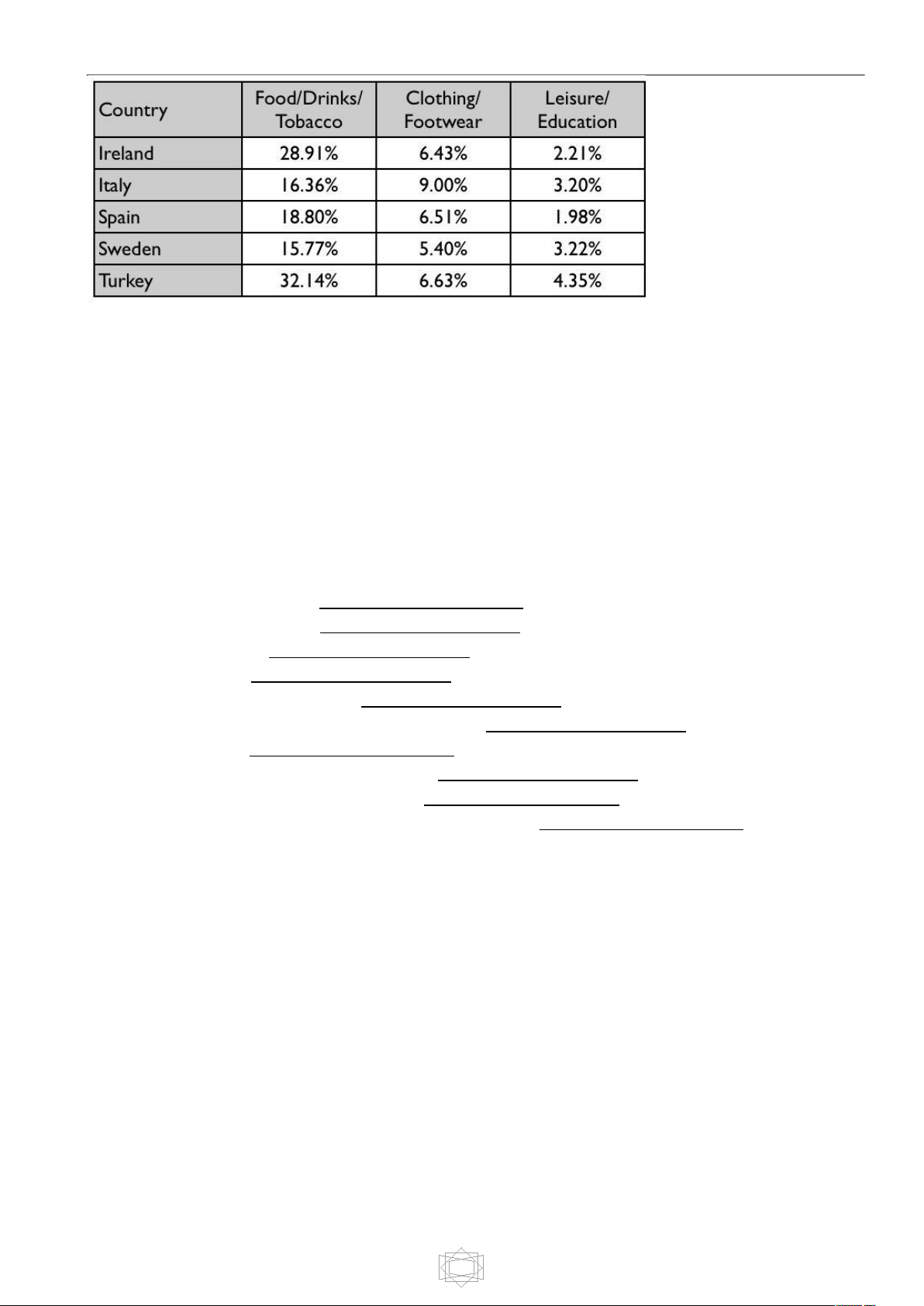

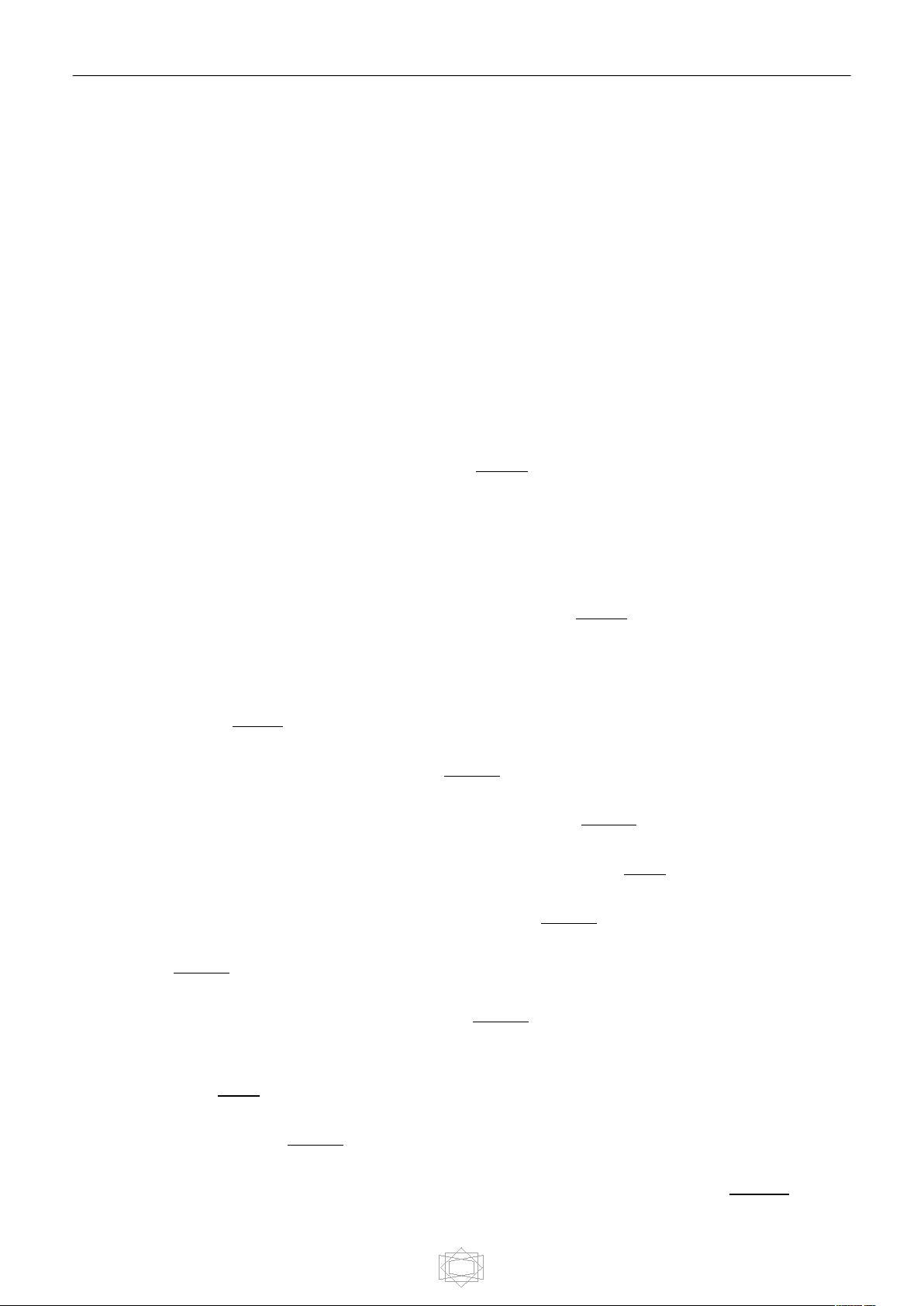

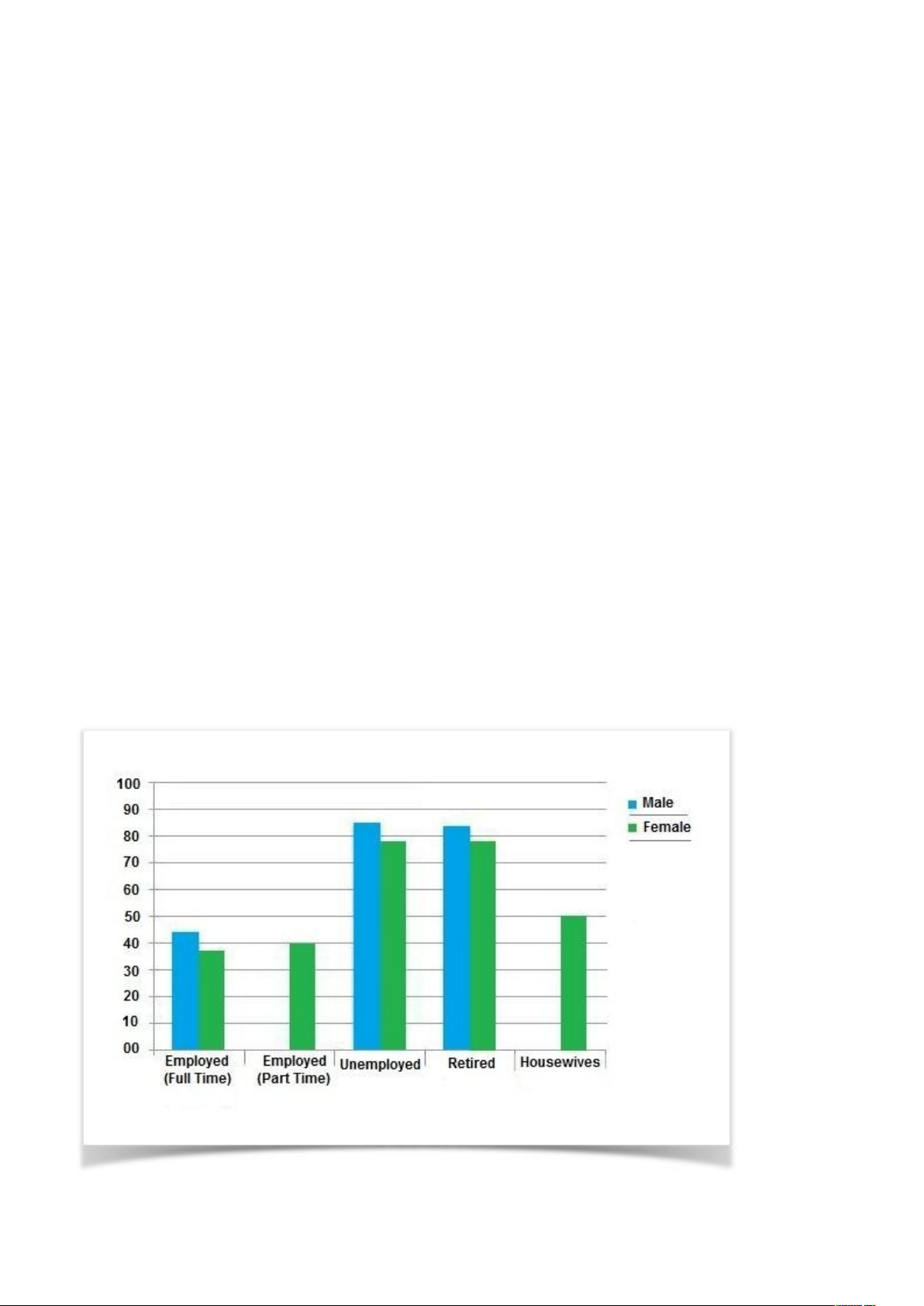

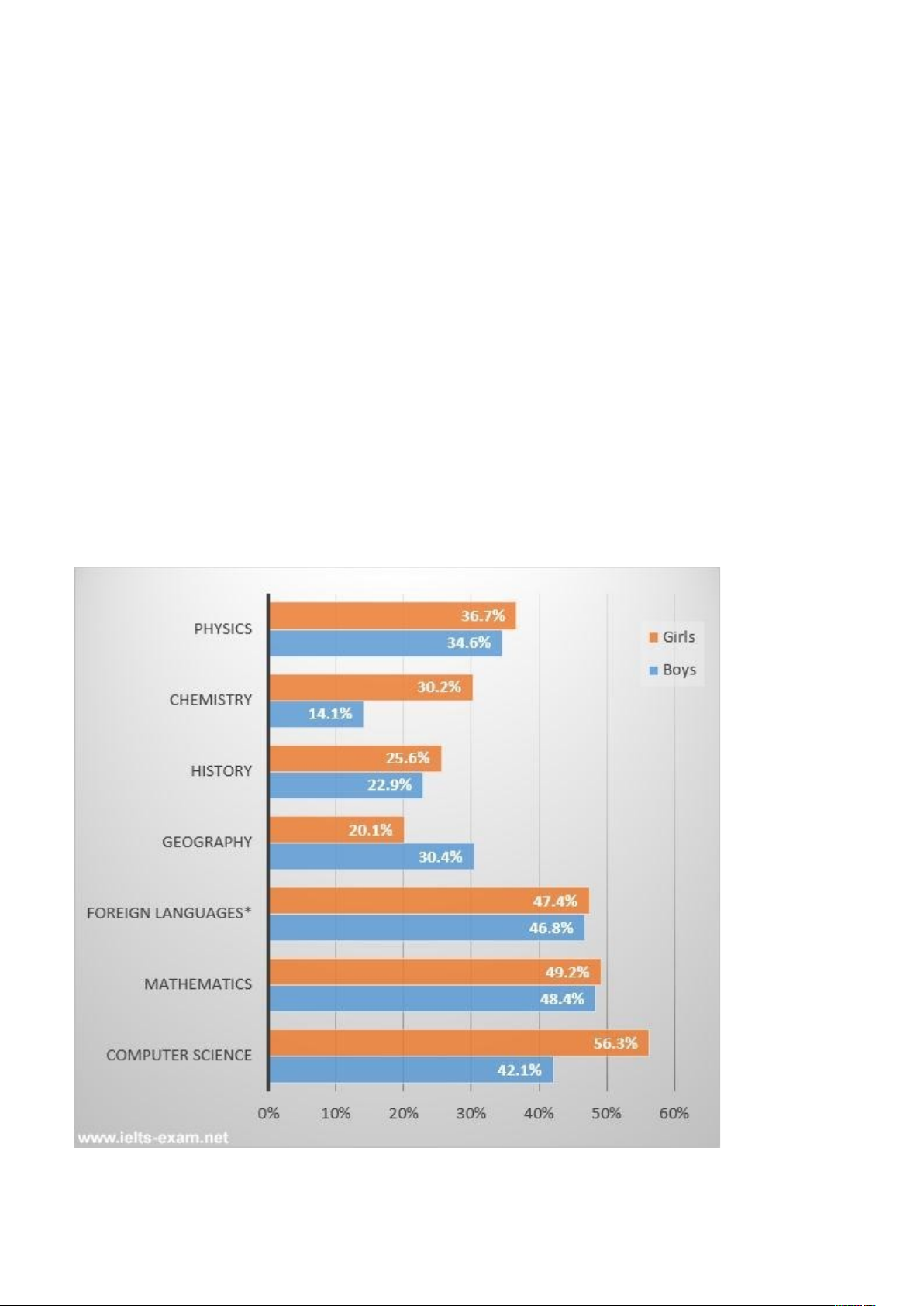

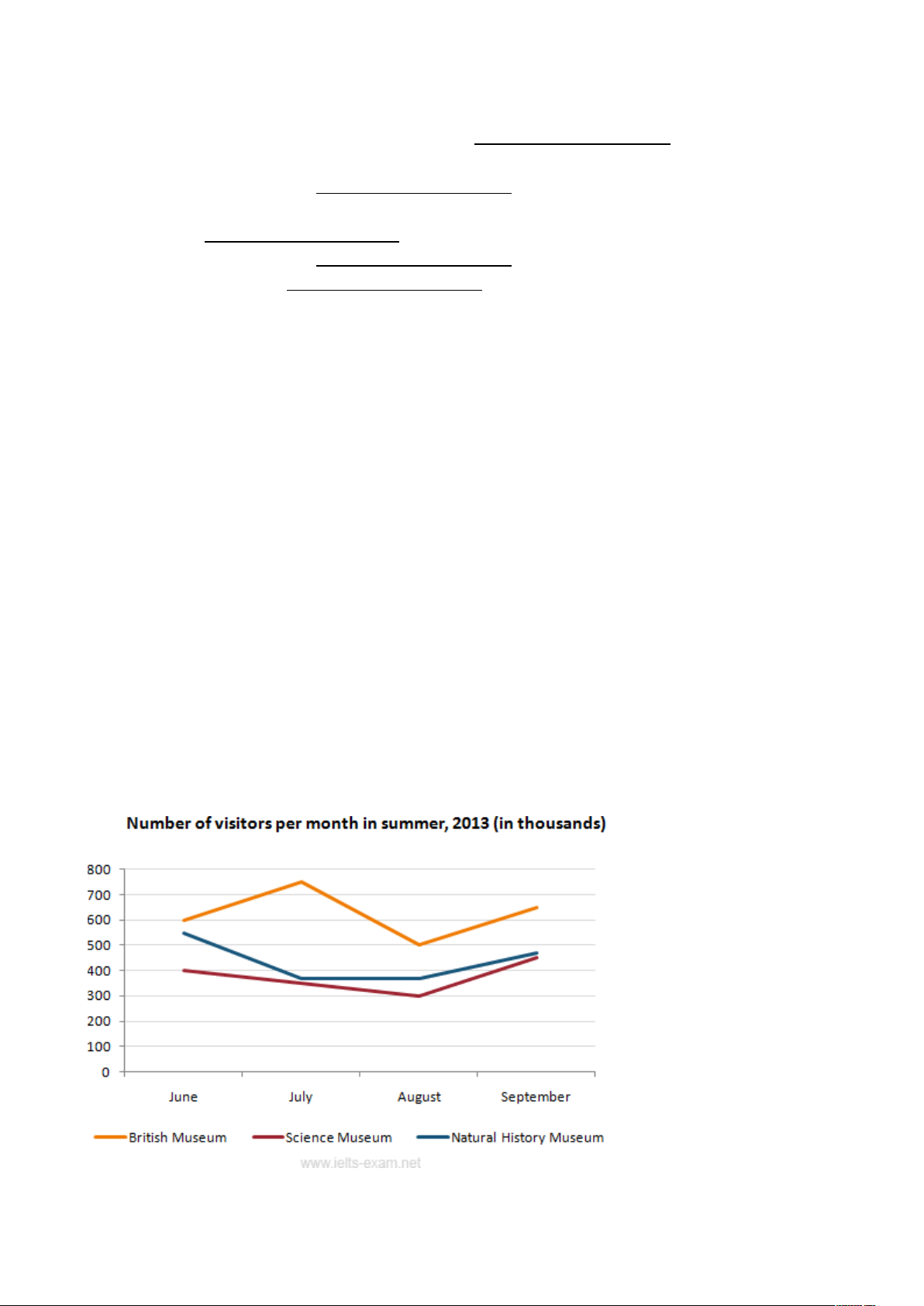

Part 2: Graph describing

The graph shows the number of hours children aged 10-11 spend on watching TV and

computers in the UK from 2000 to 2009.

Write a report for a university lecturer describing the information shown. Write about 150

words.

Time schoolchildren (10 - 11 years old) spent on different home activities

25

20

15

10

5

0

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009

Part 3. Essay writing

Some schools often get students’ ideas to evaluate their teachers. In your opinion, should all

schools ask students to evaluate their teacher?

Use specific reasons and examples to support your answer.

Hours per week

PRACTICE TEST 2

I. LISTENING

Part 1: Listen to a lecture about behavior of Dolphins and complete the note below. Write NO

MORE THAN THREE WORDS AND/OR A NUMBER for each answer.

BEHAVIOUR OF DOLPHINS

- almost 40 species of dolphin - found (1)

- usually in shallower seas - carnivores

SOCIALISING

- very sociable and live in pods

- super-pods may have more than (2) _ dolphins

- have strong social bonds

- help other animals - Moko helped a whale and calf escape from (3)

- have been known to assist swimmers

CULTURE

- discovered in May 2005 that young bottlenose dolphins learn to (4)

- dolphins pass knowledge from mothers to daughters, whereas primates pass to (5)

AGGRESSION

- dolphins may be aggressive towards each other

-Like humans, this is due to disagreements over (6) and competition for females

- Infanticide sometimes occurs and the killing of porpoises

FOOD

- dolphins have a variety of feeding methods, some of which are (7) to

one population

- Methods include:

herding

coralling

(8) or strand feeding

whacking fish with their flukes

PLAYING

- have a variety of playful activities

- common behaviour with an object or small animal include:

carrying it along

passing it along

(9) away from another dolphin

throwing it out the water

- may harass other animals

- playful behaviour may include other (10) such as humans

Part 2: Listen to a tutor and a student discussing transport. Write NO MORE THAN THREE

WORDS AND/OR A NUMBER for each answer.

1. What is John researching?

.

2. Apart from pollution, what would John like to see reduced?

.

3. According to John‘s tutor‘s, what can cars sometimes act as?

.

Practice Tests for the

gifted

Compiler: Ngo Minh

Chau

11

4. How much does John‘s tutor pay to drive into London?

.

5. In Singapore, what do car owners use to pay their road tax?

.

Part 3: Listen to the classroom conversation about the benefits of sport and decide whether the

following statements are true (T) or False (F). Write T or F in the space given.

Statements True (T) False (F)

1. The class have already talked about at least three of the physical effects

sport has on the human body.

2. Doing sport can slow down the production of chemicals in the brain that

make us feel good.

3. It doesn‘t matter which sport you choose, as long as you‘re good at it.

4. Swimmers or tennis players are responsible for their own achievements.

5. Being part of a team requires you to practise more regularly.

Part 4: You will hear a radio discussion about children who invent imaginary friends. Choose the

best answer (A, B, C or D) which fits best according to what you hear.

1. In the incident that Liz describes, .

A. her daughter asked her to stop the car B. she had to interrupt the journey twice

C. she got angry with her daughter D. her daughter wanted to get out of the car

2. What does the presenter say about the latest research into imaginary friends?

A. It contradicts other research on the subject.

B. It shows that the number of children who have them is increasing.

C. It indicates that negative attitudes towards them are wrong.

D. It focuses on the effect they have on parents.

3. How did Liz feel when her daughter had an imaginary friend?

A. always confident that it was only a temporary situation

B. occasionally worried about the friend‘s importance to her daughter

C. slightly confused as to how she should respond sometimes

D. highly impressed by her daughter‘s inventiveness

4. Karen says that one reason why children have imaginary friends is that _ .

A. they are having serious problems with their real friends

B. they can tell imaginary friends what to do

C. they want something that they cannot be given

D. they want something that other children haven‘t got

5. Karen says that the teenager who had invented a superhero is an example of .

A. a very untypical teenager B. a problem that imaginary friend can cause

C. something she had not expected to discover D. how children change as they get older

II. LEXICO-GRAMMAR

Part 1: Choose the best option A, B, C or D to complete the following sentences.

1. She agreed to go with him to the football match although she had no interest in the game at

all.

A. apologetically B. grudgingly C. shamefacedly D. discreetly

2. The smoke from the burning tyres could be seen for miles.

A. sweeping B. billowing C. radiating D. bulgingo

3. A common cause of is the use of untreated water in preparation for foods, which is quite

common in certain underdeveloped countries.

A. displeasure B. malnutrition C. eupepsia D. dysentery

4. Among scientists and non-scientists , many now say that it‘s a given that human-induced

warming threatens to disrupt life on Earth.

A. respectively B. alike C. both D. likewise

5. We are pleased to inform you that we have decided to your request for British citizenship.

A. give B. grant C. permit D. donate

6. Only after he had carefully the figures did he make any comments.

A. estimated B. watched C. scrutinised D. remarked

7. I‘m not sufficiently versed computers to understand what you‘re saying.

A. to B. into C. about D. in

8. Tom‘s normally very efficient but he‘s been making a lot of mistakes .

A. of late B. for now C. in a while D. shortly

9. On the way to Cambridge yesterday, the road was blocked by a fallen tree, so we had to make a

.

A. deviation B. digression C. detour D. departure

10. Let us hope that _ a nuclear war, the human race still survive.

A. in relation to B. with reference to C. in the event of D. within the realm of

Part 2: Give the correct forms of the words given to complete the passages.

ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE

Alternative medicine is, by definition, an alternative to something else: modern, Western medicine.

But the term ‗alternative‘ can be (1) misleading (LEAD), even off-putting for some people.

Few (2) practitioners (PRACTICE) of homeopathy, acupuncture, (3) herbalism

(HERBAL) and the like regard therapies as complete substitutes for modern medicine. Rather, they

consider their disciplines as (4) substitutes (SUPPLY) to orthodox medicine. The problem is

that many doctors refuse even to recognize ‗natural‘ or alternative medicine. To do so calls for a (5)

radically (RADICAL) different view of health, illness and cure. But whatever doctors may think,

the demand for alternative forms of medical therapy is stronger than ever before, as the (6) limitations

(LIMIT) of modern medical science become more widely understood. Alternative therapies are often

dismissed by orthodox medicine because they are sometimes (7) administered (ADMINISTRATION)

by people with no formal medical training. But, in comparison with many traditional therapies, western

medicine as we know it today is a very recent phenomenon. Until only 150 years ago, herbal medicine

and simple (8) inorganic (ORGAN) compounds were the most effective treatment

available. Despite the medical establishment‘ (9) intolerant (TOLERATE) attitude,

alternative therapies are being accepted by more and more doctors, and the World Health Organization

has agreed to promote the (10) intergration (INTEGRATE) of proven, valuable,

`alternative´ knowledge and skills in western medicine.

Part 3: There are 10 mistakes in the following passage. Write the mistakes and corrections in the

space given.

True relaxing is most certainly not a matter of flopping down in front of the television with a

welcome drink. Nor is it about drifting into an exhausted sleep. Useful though these responses to

tension and over-tiredness might be, we should distinguish among them and conscious relaxation in

terms of quality and effect. Regarded of the level of tiredness, real relaxation is a state of alert yet in the

same time passive awareness, in which our bodies are at rest while our minds are waken.

Moreover, it is as natural for a healthy person to be relaxed when moving as resting. Being relaxed

in action means we bring the appropriate energy to everything we do, so to have a feeling of health

tiredness by the end of the day, rather than one of exhaustion. Unfortunately, as a result of living in

today‘s competitive world, we are under constant strain and have difficult in coping, let alone nurturing

our body‘s abilities. Which needs to be rediscovered is conscious relaxation. With that in mind we must

apply ourselves to understand stress and the nature of its causes how deep-seated.

Part 4. Fill in each blank with the correct preposition(s)/ particle(s.

1. Footballers used to abide bt the referee‘s decision, but nowadays they are just as likely to punch

him in the mouth.

2. My speech is okay but I just hope I don‘t dry up as soon as I get to the podium.

3. My brother has always been on the fringe of the Labour party, never at the centre.

4. The paintings were given to the state by the millionaire in lieu of taxes.

5. Did you know that Samantha has taken up Martin again - they‘re spending lots of time

together.

6. I‘ve been asked to key information of the computer immediately.

7. I don‘t like him as every time he asks me to do something, his voice is always laden with

threat.

8. I feel quite nostalgic _ about the place where I grew up.

9. I was thinking of going to live in Scotland, but when I heard that I would have to wear a kilt, I

decided against it.

10. Good hygiene helps keep down the levels of infection.

III. READING

Part 1. Read the article below and circle the word which best fits each space.

Broadcasting has democratized the publication of language, often at its most informal, even

undressed. Now the ears of the educated cannot escape the language of the masses. It (1) them

on the news, weather, sports, commercials, and the ever-proliferating game shows. This wider

dissemination of popular speech may easily give purists the (2) that language is suddenly going

to hell in this generation, and may (3) the new paranoia about it.

It might also be argued that more Armericans hear more correct, even beautiful, English on

television than ever before. Through television more models of good usage (4) more American

homes than was ever possible in other times. Television gives them lots of (5) English too, some

awful, some creative, but that is not new.

Hidden in this is a (6) _ fact: our language is not the special private property of the language

police, or grammarians, or teachers, or even great writers. The (7) of English is that it has always

been the tongue of the common people, literate or not.

English belongs to everybody: the funny (8) of phrase that pops into the mind of a farmer

telling a story; or the (9) salesman‘s dirty joke; or the teenager saying, "Gag me with a spoon";

or the pop lyric - all contribute, are all as (10) as the tortured image of the academic, or the line

the poet sweats over for a week.

1. A. circles B. surrenders C. supports D. surrounds

2. A. thought B. idea C. sight D. belief

3. A. justify B. inflate C. explain D. idealise

4. A. render B. reach C. expose D. leave

5. A. colloquial B. current C. common D. spoken

6. A. central B. stupid C. common D. simple

Practice Tests for the

gifted

Compiler: Ngo Minh

Chau

14

7. A. genii B. genius C. giant D. generalisation

8. A. turn B. twist C. use D. time

9. A. tour B. transport C. travel D. travelling

10. A. valued B. valid C. truthful D. imperfect

Part 2: Fill in the blanks with one suitable word for each to complete the following passage.

Throughout our lives, right from the moment when as infants we cry to express our hunger, we are

engaged in social interaction of one form or another. Each and (1) every time we encounter

fellow human beings, some kind of social interaction will take place, (2)whether

a bus and paying the fare for the journey, or socializing with friends. It goes without (3)

it‘s getting on

saying,

therefore, that we need the ability to communicate. Without some method of (4) transmitting

intentions, we would be at a(n) (5) complete loss when it came to interacting socially.

Communication (6) involves the exchange of information which can be anything from a gesture

to a friend signalling boredom to the presentation of a university thesis which may only ever be read by

a (7) handful of others, or it could be something in (8) between the two. Our highly developed

languages set us (9) apart from animals. But for these languages, we could not communicate

sophisticated or abstract ideas. Nor could we talk or write about people or objects mot immediately

present. (10) were _ we restricted to discussing objects already present, we would be able to make

abstract generalizations about the world.

Part 3: Read the passage then circle the best option A, B, C or D.

PERCEPTION

It is often helpful when thinking about biological processes to consider some apparently similar yet

better understood non-biological process. In the case of visual perception an obvious choice would be

colour photography. Since in many respects eyes resemble cameras, and percepts photographs, is it not

reasonable to assume that perception is a sort of photographic process whereby samples of the external

world become spontaneously and accurately reproduced somewhere inside our heads? Unfortunately,

the answer must be no. The best that can be said of the photographic analogy is that it points up what

perception is not. Beyond this it is superficial and misleading. Four simple experiments should make

the matter plain.

In the first a person is asked to match a pair of black and white discs, which are rotating at such a

speed as to make them appear uniformly grey. One disc is standing in shadow, the other in bright

illumination. By adjusting the ratio of black to white in one of the discs the subject tries to make it look

the same as the other. The results show him to be remarkably accurate, for it seems he has made the

proportion of black to white in the brightly illuminated disc almost identical with that in the disc which

stood in shadow. But there is nothing photographic about his perception, for when the matched discs,

still spinning, are photographed, the resulting print shows them to be quite dissimilar in appearance.

The disc in shadow is obviously very much darker than the other one. What has happened? Both the

camera and the person were accurate, but their criteria differed. One might say that the camera recorded

things as they look, and the person things as they are. But the situation is manifestly more complex than

this, for the person also recorded things as they look. He did better than the camera because he made

them look as they really are. He was not misled by the differences in illumination. He showed

perceptual constancy. By reason of an extremely rapid, wholly unconscious piece of computation he

received a more accurate record of the external world than could the camera.

In the second experiment a person is asked to match with a colour card the colours of two pictures in

dim illumination. One is of a leaf, the other of a donkey. Both are coloured an equal shade of green. In

making his match he chooses a much stronger green for the leaf than for the donkey. The leaf evidently

looks greener than the donkey. The percipient makes a perceptual world compatible with his own

experience. It hardly needs saying that cameras lack this versatility.

In the third experiment hungry, thirsty and satiated people are asked to equalize the brightness of

pictures depicting food, water and other objects unrelated to hunger or thirst. When the intensities at

which they set the pictures are measured it is found that hungry people see pictures relating to food as

brighter than the rest (i.e. to equalize the pictures they make the food ones less intense), and thirsty

people do likewise with

―

dr

ink‖

pictures. For the satiated group no difference

s

are obtained be

tw

een the

different objects. In other words, perception serves to satisfy needs, not to enrich subjective experience.

Unlike a photograph the percept is determined by more than just the stimulus.

The fourth experiment is of a rather different kind. With ears plugged, their eyes beneath translucent

goggles and their bodies either encased in cotton wool, or floating naked in water at body temperature,

people are deprived for considerable periods of external stimulation. Contrary to what one might

expect, however, such circumstances result not in a lack of perceptual experience but rather a surprising

change in what is perceived. The subjects in such an experiment begin to see, feel and hear things

which bear no more relationship to the immediate external world than does a dream in someone who is

a

slee

p. The

se

people are not a

slee

p yet their hallucinations, or

so-called

―

autistic

‖

perceptions, may be

as vivid, if not more so, than any normal percept.

1. In the first paragraph, the author suggests that .

A. colour photography is a biological process B. vision is rather like colour photography

C. vision is a sort of photographic process

D. vision and colour photography are very different

2. What does the word

―

it

‖

in the f

irst

paragraph refer to ?

A. perception

B. the photographic process

3. In the first experiment, it is proved that a person _

.

C. the comparison with photography

D. the answer

A. makes mistakes of perception and is less accurate than a camera

B. can see more clearly than a camera

C. is more sensitive to changes in light than a camera

D. sees colours as they are in spite of changes in the light

4. What does the word

―

th

at

‖

in the

sec

ond paragraph refer to ?

A. the proportion of black to white

B. the brightly illuminated disc

5. The second experiment shows that .

C. the other disc

D. the grey colour

A. people see colours according to their ideas of how things should look

B. colours look different in a dim light

C. cameras work less efficiently in a dim light D. colours are less intense in larger objects

6. What does the word

―

s

atiated

‖

in the fourth paragraph mean?

A. tired B. bored C. not hungry or thirsty D. nervous

7. What does

―

to equal

ize

th

e

brightn

e

ss

‖

in the fourth paragraph mean?

A. To arrange the pictures so that the equally bright ones are together

B. To change the lighting so that the pictures look equally bright

C. To describe the brightness D. to move the pictures nearer or further away

8. The third experiment proves that .

A. we see things differently according to our interest in them

B. pictures of food and drink are especially interesting to everybody

Practice tests for the national examination for the

gifted

Compiler: Ngô Minh

Châu

16

C. cameras are not good at equalising brightness

D. satiated people see less clearly than hungry or thirsty people

9. The expression

―

c

ontrar

y to w

h

at o

n

e m

igh

t expect

‖

occurs the fifth paragraph. What might one

expect?

A. that the subjects would go to sleep

B. that they would feel uncomfortable and disturbed

C. that they would see, hear and feel nothing

D. that they would see, hear and feel strange things

10. The fourth experiment proves that .

A. people deprived of sense stimulation go mad

B. people deprived of sense stimulation dream

C. people deprived of sense stimulation experience unreal things

D. people deprived of sense stimulation lack perceptual experience

Part 4. Read the following passage and do the task following.

VIEWS OF INTELLIGENCE ACROSS CULTURES

A In recent years, researchers have found that people in non-Western cultures often have ideas about

intelligence that are considerably different from those that have shaped Western intelligence tests.

This cultural bias may therefore work against certain groups of people. Researchers in cultural

differences in intelligence, however, face a major dilemma, namely: how can the need to compare

people according to a standard measure be balanced with the need to assess them in the light of

their own values and concepts?

B For example, Richard Nesbitt of the University of Michigan concludes that East Asian and Western

cultures have developed cognitive styles that differ in fundamental ways, including how

intelligence is understood. People in Western cultures tend to view intelligence as a means for

individuals to devise categories and engage in rational debate, whereas Eastern cultures see it as a

way for members of a community to recognize contradiction and complexity and to play their

social roles successfully. This view is backed up by Sternberg and Shih-Ying, from the University

of Taiwan, whose research shows that Chinese conceptions of intelligence emphasize

understanding and relating to others, and knowing when to show or not show one‘s intelligence.

C The distinction between East Asia and the West is just one of many distinctions that separate

different ways of thinking about intelligence. Robert Serpell spent a number of years studying

concepts of intelligence in rural African communities. He found that people in many African

communities, especially in those where Western-style schooling is still uncommon, tend to blur the

distinction between intelligence and social competence. In rural Zambia, for instance, the concept

of nzelu includes both cleverness and responsibility. Likewise, among the Luo people in rural

Kenya, it has been found that ideas about intelligence consist of four broad concepts. These are

named paro or practical thinking, luoro, which includes social qualities like respect and

responsibility, winjo or comprehension, and rieko. Only the fourth corresponds more or less to the

Western idea of intelligence.

D In another study in the same community, Sternberg and Grogorenko have found that children who

score highly on a test of knowledge about medicinal herbs, a test of practical intelligence, often

score poorly on tests of academic intelligence. This suggests that practical and academic

intelligence can develop independently of each other, and the values of a culture may shape the

direction in which a child‘s intelligence develops.

It also tends to support a number of other studies which suggest that people who are unable to

solve complex problems in the abstract can often solve them when they are presented in a familiar

context. Ashley Maynard, for instance, now professor of psychology at the University of Hawaii,

conducted studies of cognitive development among children in a Mayan village in Mexico using

toy looms, spools of thread, and other materials drawn from the local environment. The research

suggested that the children‘s development, could be validly compared to the progression described

by Western theories of development, but only by using materials and experimental designs based

on their own culture.

E The original hope of many cognitive psychologists was that a test could be developed that was

absent of cultural bias. However, there seems to be an increasing weight of evidence to suggest

that this is unlikely. Raven‘s Progressive Matrices, for example, were originally advertised as

‗culture free‘ but are now recognized as culturally loaded. Such non-verbal intelligence tests are

based on cultural constructs which may not appear in a particular culture. It is doubtful whether

cultural comparisons of concepts of intelligence will ever enable us to move towards creating a test

which encompasses all aspects of intelligence as understood by all cultures. It seems even less

likely that such a test could be totally free of cultural imbalance somewhere.

The solution to the dilemma seems to lie more in accepting that cultural neutrality is unattainable

and that administering any valid intelligence test requires a deep familiarity with the relevant

culture‘s values and practices.

Questions 1-5

Choose the correct heading for each paragraph A–E from the list of headings below (i-ix). There are

more headings than paragraphs. Write your answers in the corresponding numbered boxes.

List of Headings

i Research into African community life

ii Views about intelligence in African societies

iii The limitations of Western intelligence tests

iv The Chinese concept of intelligence

v The importance of cultural context in test design

vi The disadvantages of non-verbal intelligence tests

vii A comparison between Eastern and Western understanding of intelligence

viii Words for

―

intelligence

‖

in

African languages

ix The impossibility of a universal intelligence test

Your answers

1. Section A iii

2. Section B vii

3. Section C i

4. Section D v

5. Section E ix

Questions 6-10

Look at the researchers in 6-10 and the list off findings below. Match each researcher with the correct

finding. Write your answers in the corresponding numbered boxes.

Your answers

6. Ashley Maynard e

7. Richard Nesbitt g

8. Sternberg and Grogorenko d

9. Sternberg and Shih-Ying a

10. Robert Serpell c

List of findings

A There is a clear relationship between intelligence and relationships with others in Chinese culture.

B Children frequently scoring well in academic tests score better in practical tests.

C The difference between intelligence and social competence is not distinct in many African

communities.

D Children frequently scoring well in practical tests score less well in academic tests.

E In experiments to measure cognitive development, there is a link between the materials used and the

test results.

F The connection between intelligence and social competence in many African communities is not

clear.

G The way cognition is viewed in East Asian cultures differs fundamentally from those in Western

cultures.

H Chinese culture sees revelations about one‘s intelligence as part of intelligence.

IV. WRITING

Part 1: Summarize in no more than 120 words, the various communicative methods practiced by

animals in the wild.

Communication is part of our everyday life. We greet one another, smile or frown, depending on our

moods. Animals too, communicate, much to our surprise. Just like us, interaction among animals can

be both verbal and non-verbal. Singing is one way in which animals can interact with one another.

Male blackbirds often use their melodious songs to catch the attention of the females. These songs are

usually rich in notes variation, encoding various kinds of messages. Songs are also used to warn and

keep off other blackbirds from their territory, usually a place where they dwell and reproduce. Large

mammals in the oceans sing too, according to adventurous sailors. Enormous whales groan and grunt

while smaller dolphins and porpoises produce pings, whistles and clicks. These sounds are surprisingly

received by other mates as far as several hundred kilometers away. Besides singing, body language also

forms a large part of animals' communication tactics. Dominant hyenas exhibit their power by raising

the fur hackles on their necks and shoulders, while the submissive ones normally "surrender" to the

powerful parties by crouching their heads low and curling their lips a little, revealing their teeth in

friendly smiles.Colors, which are most conspicuously found on animals are also important means of

interaction among animals. Male birds of paradise, which have the most gaudy colored feathers often

hang themselves upside down from branches, among fluffing plumes, displaying proudly their feathers,

attracting the opposite sex. The alternating black and white striped coats of zebras have their roles to

play too. Each zebra is born with a unique set of stripes which enables its mates to recognize them.

When grazing safely, their stripes are all lined up neatly so that none of them loses track of their

friends. However, when danger such as a hungry lion approaches, the zebras would dart out in various

directions, making it difficult for the lion to choose his target. Insects such as the wasps, armed with

poisonous bites or stings, normally have brightly painted bodies to remind other predators of their

power. Hoverflies and other harmless insects also make use of this fact and colored their bodies

brightly in attempts to fool their predators into thinking that they are as dangerous and harmful as the

wasps too.

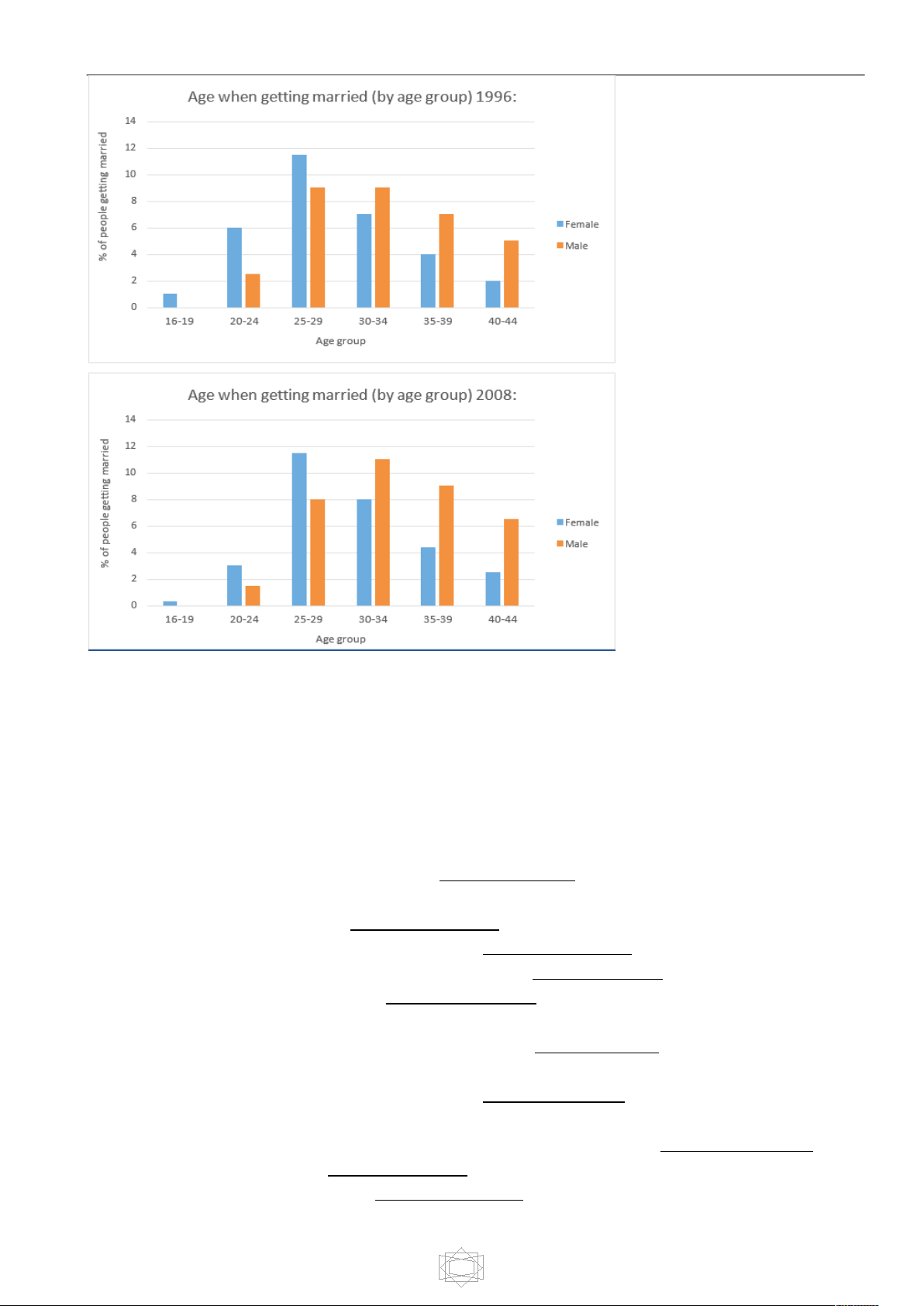

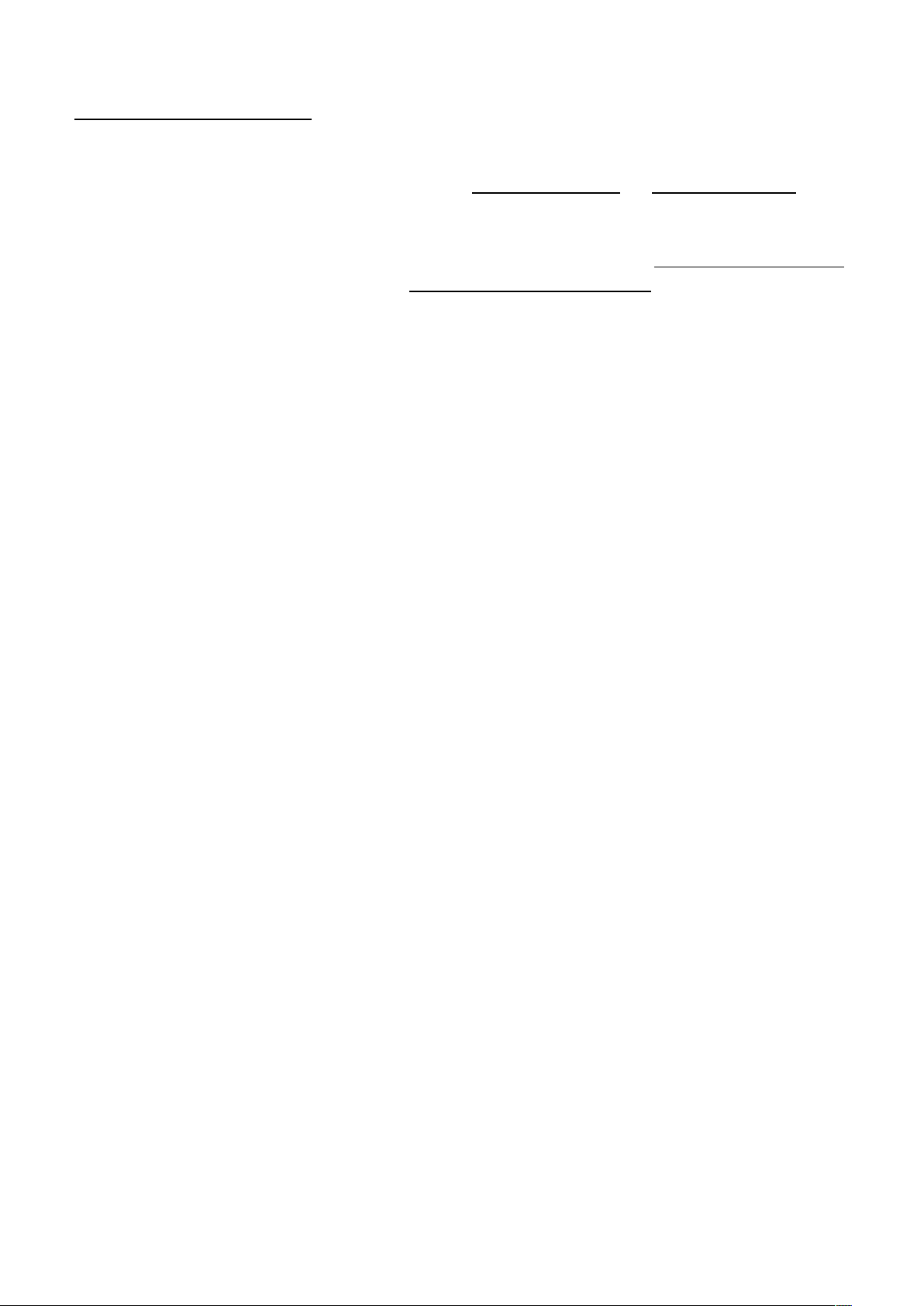

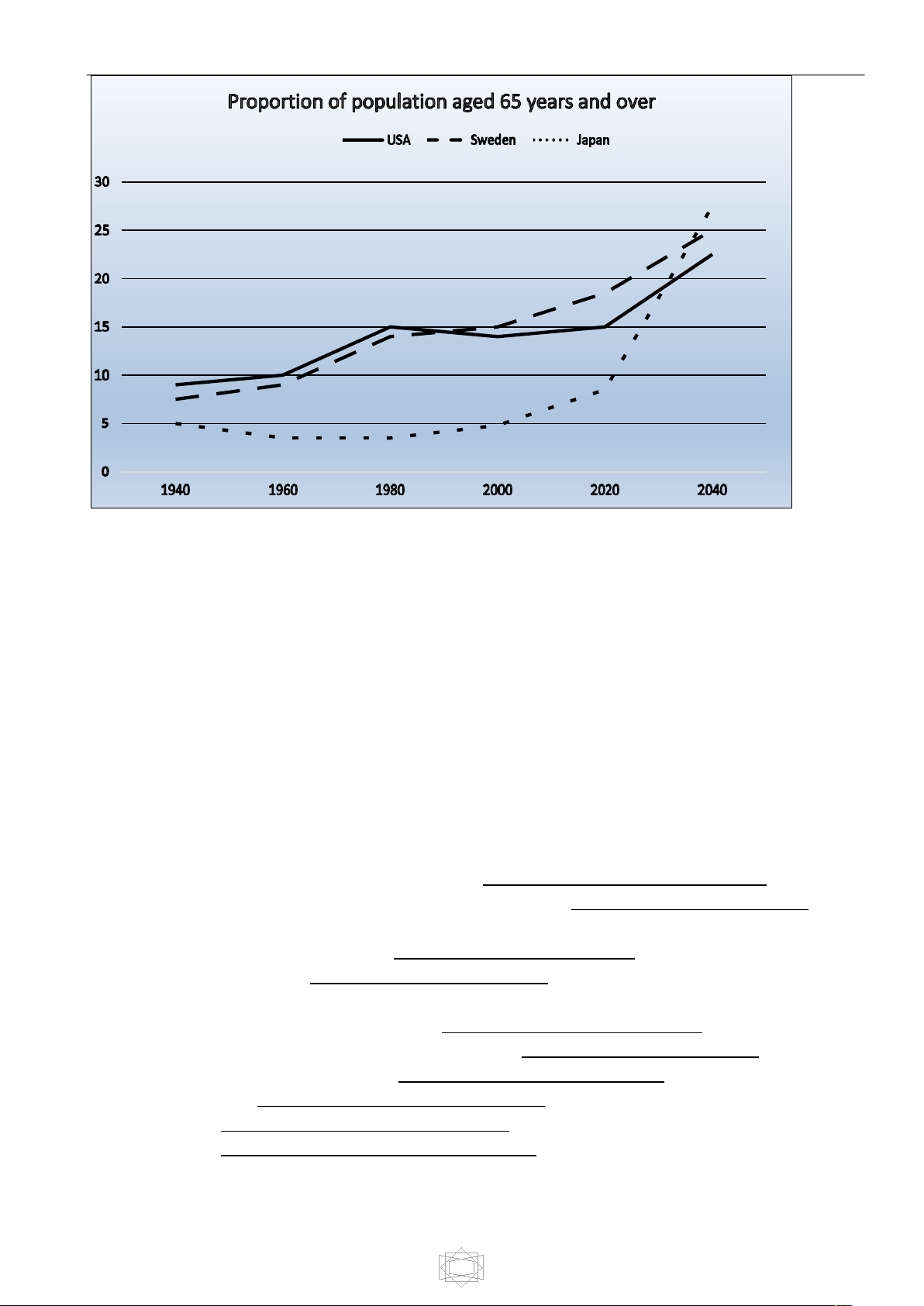

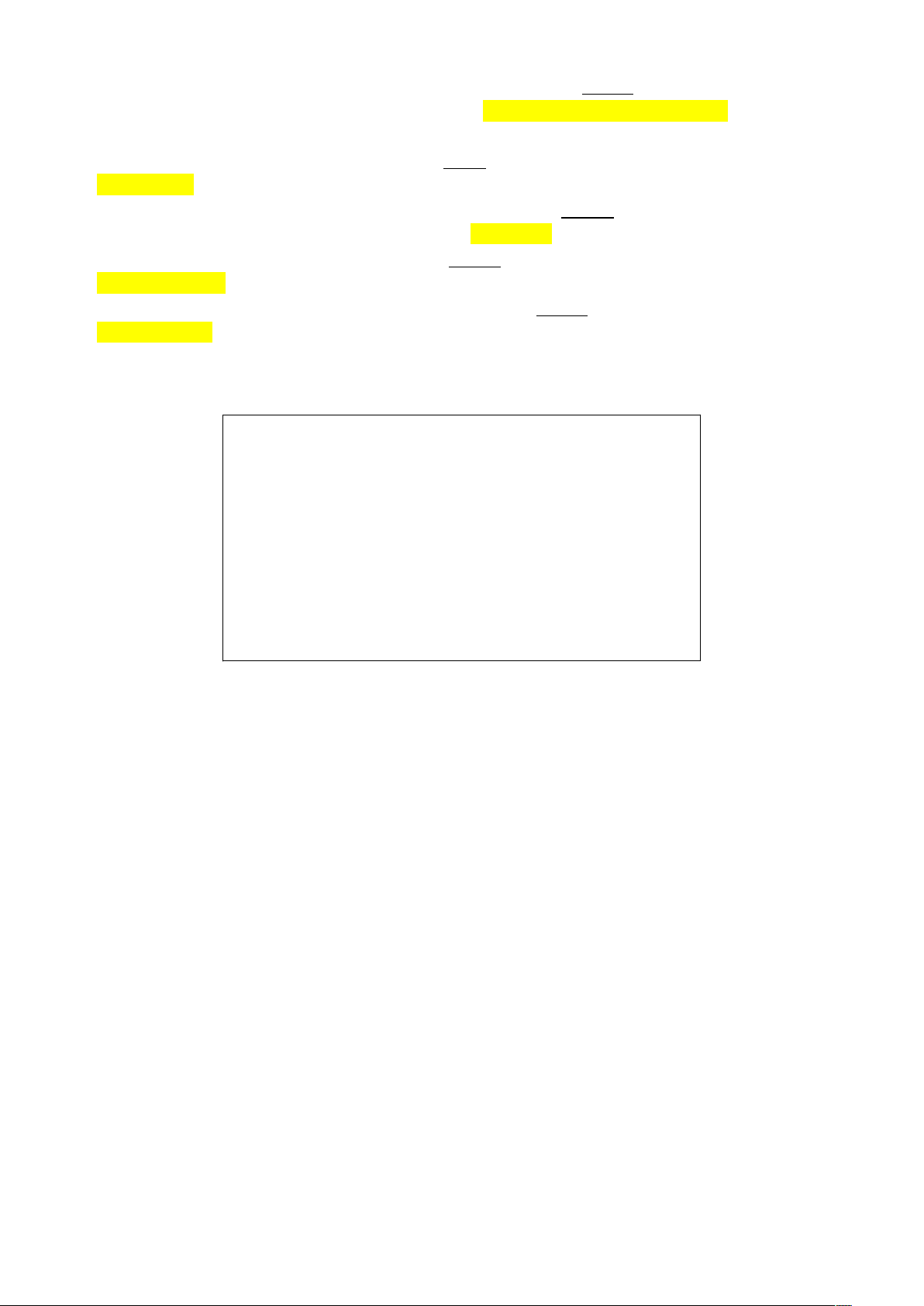

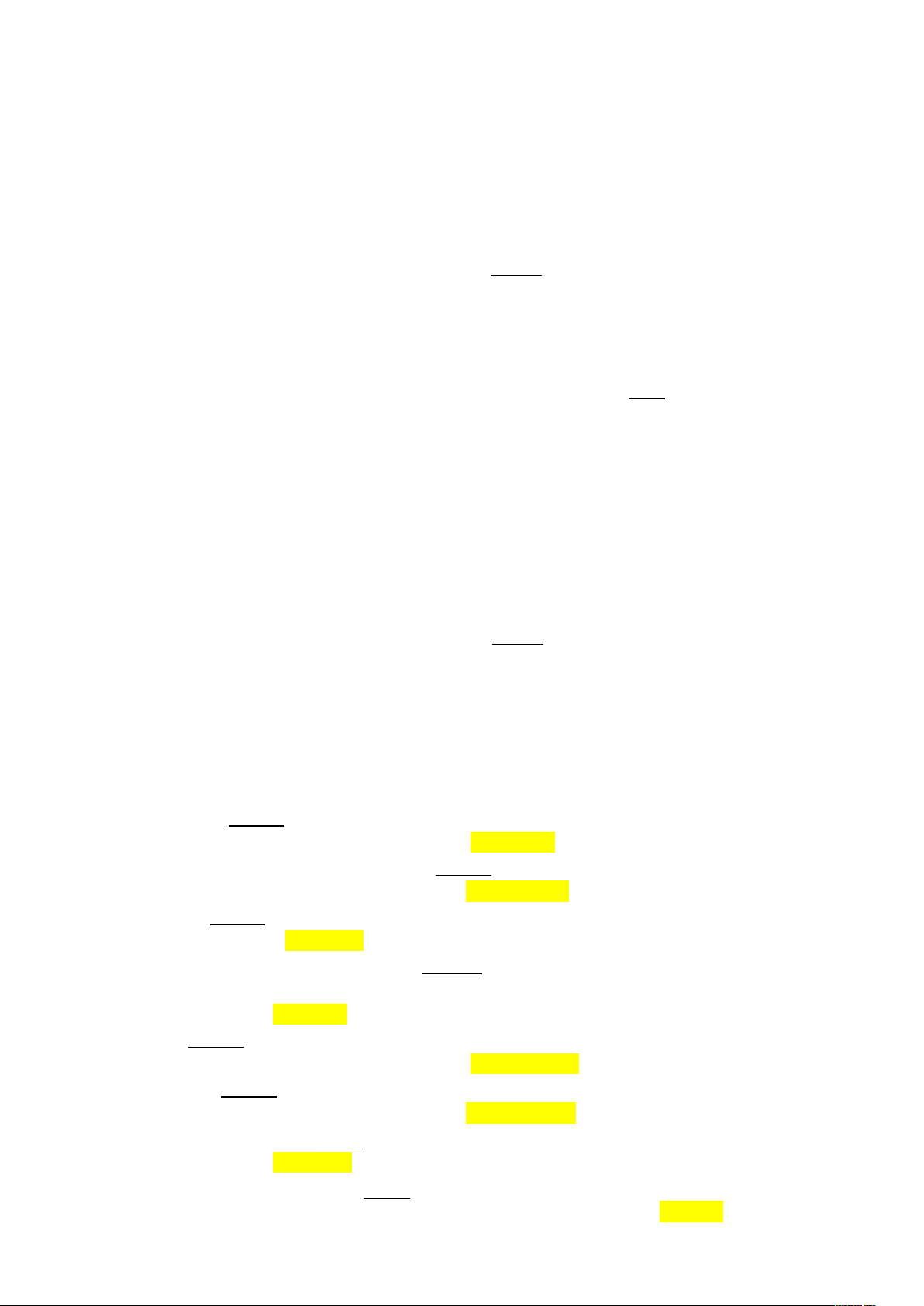

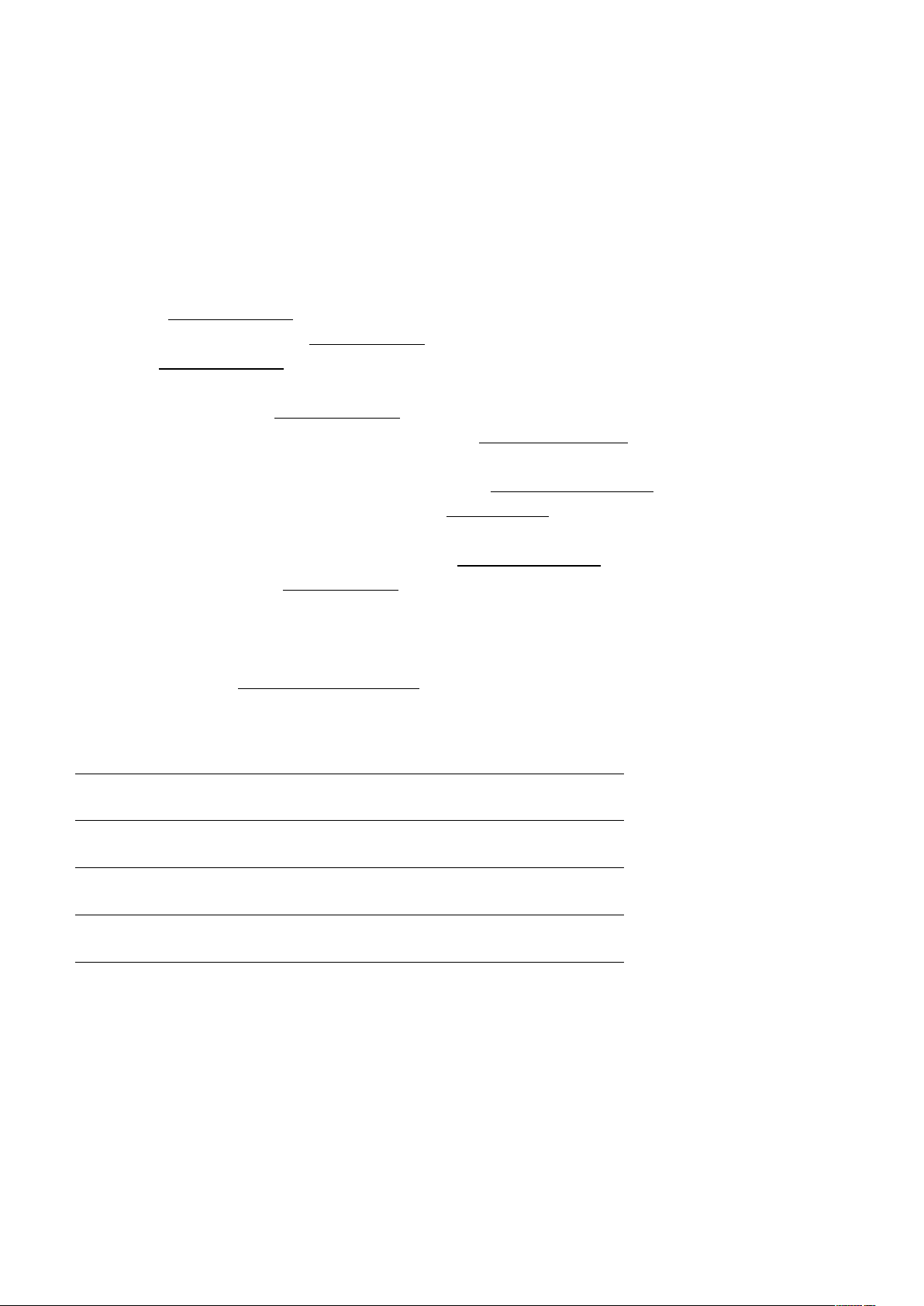

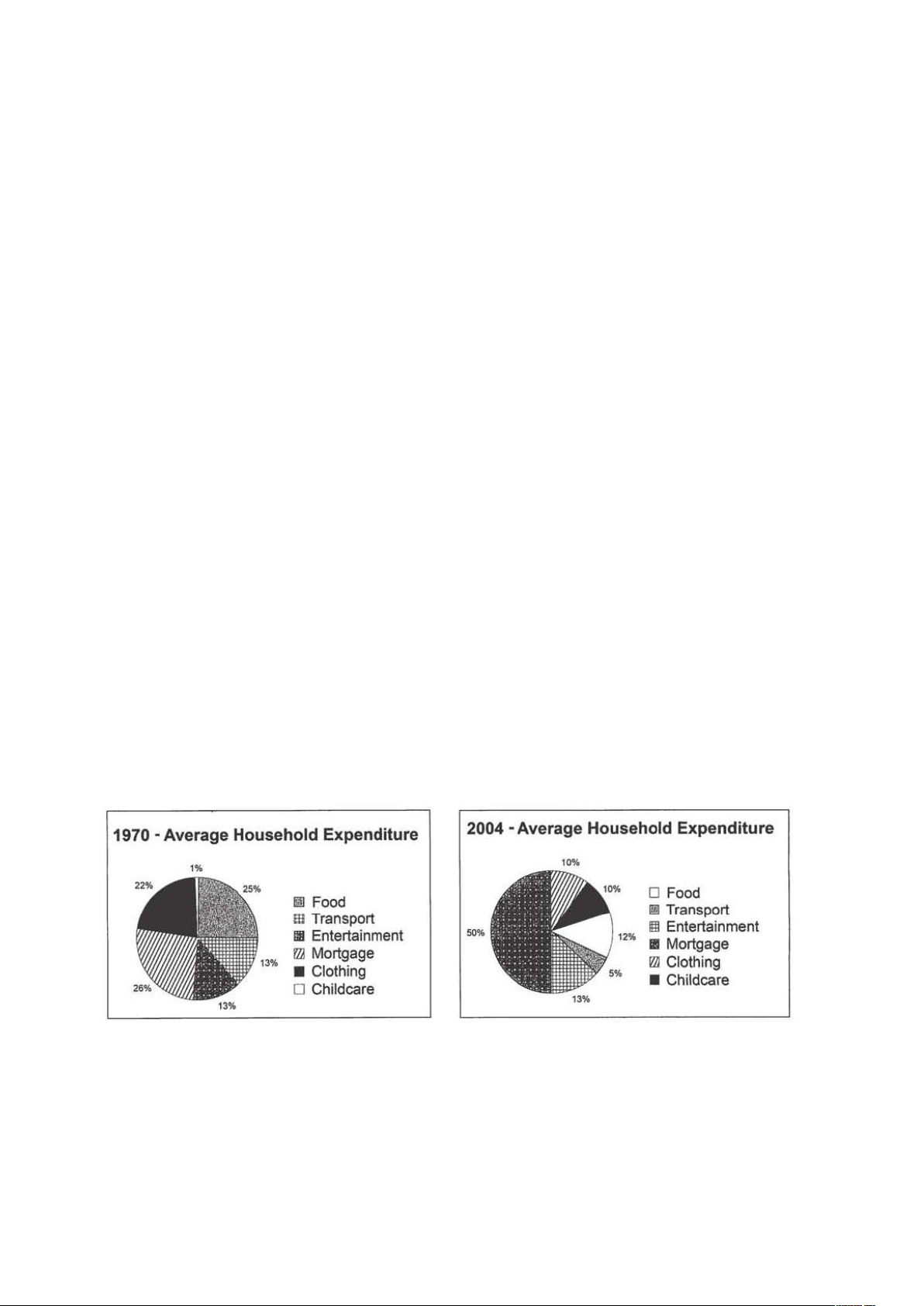

Part 2. The charts below give information on the ages of people when they got married in one

particular country in 1996 and 2008. Summarise the information by selecting and repairing the

main features, and make comparisons where relevant.

Practice tests for the national examination for the

gifted

Compiler: Ngô Minh

Châu

19

Part 3. Essay

STEM education is one of the latest ideas in the educational sphere. Write an essay about 350 words

about advantages and disadvantages of STEM education.

I. LISTENING

PRACTICE TEST 3

Part 1. Listen to the passage and then fill in the blank with NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS.

CHERRIES

During the visit to a number of fruit farms in (1) , the speaker found broad agreement

among most of the growers about fruit planting.

The speaker gives the example of (2) as a crop being replaced by cherries.

To protect young trees from extremes of weather, a (3) may be used.

Cherries are prone to cracking because there is hardly any (4) on the skin of the fruit.

The speaker compares the cherry to a (5) when explaining the effect of rain on the

fruit.

Shoppers are advised to purchase cherries which have a (6) stem and look fresh and

tasty.

The traditional view was that cherries need up to (7) before they produce a useful

crop.

The most popular new variety of cherry tree amongst farmers has the name (8) .

While picking cherries, keep a (9) in your mouth to stop you eating too many.

That way you end up with at least a (10) of this delicious fruit in your basket!

Practice tests for the national examination for the

gifted

Compiler: Ngô Minh

Châu

20

Part 2. Listen to the recording and answer the following questions.

1. What kind of food do people in the north of China eat more than ones in the south?

2. What is the first change of the diet in China?

3. Where are the snack foods now being seen?

4. What kind of dishes does the man prefer?

5. What does Chinese cooking rely on?

Part 3. You are going to hear a conversation between Richard and Louise. As you listen, indicate

whether the statements are True (T), False (F) Not Given (NG).

1. Richard does most of the washing up in his family.

2. Richard‘s father makes him clean his shoes.

3. Louise doesn‘t mind shopping for food.

4. Louise prefers to wait for her grandparents to visit her.

5. Louise‘s father repairs the car himself.

Part 4. You will hear a radio interview in which an artist called Sophie Axel is talking about her life

and career. Choose the best answer (A, B, C or D) which fits best according to what you hear.

1. Sophie illustrates the importance of colour in her life by saying she .

A. has coloured daydreams B. associates letters and colours

C. paints people in particular colours D. links colours with days of the week

2. Sophie‘s attitude to risk is that her children should be .

A. left to cope with it B. warned about it

C. taught how to deal with it D. protected from it

3. Shophie‘s mother and aunt use their artistic gifts professionally in the .

A. pictures they paint together B. plays they perform on stage

C. objects they help to create D. clothes they design and make

4. Sophie was a failure at art school because she _ .

A. was not interested in design B. favoured introspective painting

C. was very pessimistic D. had a different approach to art

5. When Sophie had no money to repair her bike, she offered to .

A. take a part-time job B. publicise a national charity

C. produce an advertisement D. design posters on commission

II. LEXICO-GRAMMAR

Part 1. Choose the best answer (A, B, C or D) to complete each sentence below.

1. Why did you and mention the party to George? It was supposed to be a surprise.

A. let the cat out of the bag B. put the cat among the pigeons

C. have kittens D. kill two birds with one stone.

2. It‘s a shame to fall out so badly with your own _ .

A. heart to heart B. flesh and blood C. heart and soul D. skin and bone

3. They were able to over their meal and enjoy it instead of having to rush back to work.

A. loiter B. stay C. linger D. dwell

4. I thought something terrible had happened but it was all a in a teacup.

A. storm B. gale C. breeze D. wind

5. It is necessary that the problem solved right away.

A. would be B. might be C. be D. is

6. In the northern and central parts of the states of Idaho and churning rivers.

A. majestic mountains are found B. found majestic mountains

C. finding majestic mountains D. are found majestic mountains

7. According to the _ of the contract, tenants must give six months‘ notice if they intend to leave.

A. laws B. rules C. terms D. details

8. I know it‘s difficult but you‘ll just have to _ and bear it.

A. laugh B. smile C. grin D. chuckle

9. I didn‘t want to make a decision , so I said I‘d like to think about it.

A. in one go B. there and then C. at a stroke D. on and off

10. We are not in a _ hurry so let‘s have another coffee.

A. dashing B. racing C. rushing D. tearing

Part 2. Read the passage and give the correct form of the words given in brackets.

EXTRACT FROM A BOOK ABOUT MEETING

We are (1. SURE) assured by the experts that we are, as a species,

designed for face-to- face communication. But does that really mean having every meeting in person?

Ask the bleary-eyed sales team this question as they struggle (2. LABOUR) labouriously through

their weekly teambuilding session and that answer is unlikely to be in the (3. AFFIRM) affirmative

. Unless you work for a very small business or have an

(4. EXCEPT) exceptionally high boredom threshold, you doubtless spend

more time sitting in meetings than you want to. Of course, you could always follow business

Norman‘s example. He liked to express (5. SOLID) solidarity with customers

queuing at the (6. CHECK) checkout by holding management meetings standing

up. Is email a realistic (7. ALTER) alternative ? It‘s clearly a powerful tool for disseminating

information, but as a meeting substitute it‘s seriously flawed. Words alone can cause trouble. We‘re all

full of (8. SECURE) insecurities that can be unintentionally triggered by others and people are

capable of reading anything they like into an email. There is also a (9. TEND) tendency

for email to be used by people who wish to avoid ‗real‘ encounters

because they don‘t want to be (10. FRONT) confronted with any awkwardness.

Part 3. The passage below contains 10 mistakes. Underline the mistakes and write their correct

forms in the space provided in the column on the right. (0) has been done as an example.

When a celebrity, a politics or other person in the media spotlight loses their temper in public, they

run the risk of hitting the headings in a most embarrassing way. For such uncontrolling outbursts of

anger are often triggered by what seem to be trivial matters and, if they are caught on camera, can make

the person appear slightly ridiculousness. But it‘s not only the rich and famous who is prone to fits of

rage. According to recent surveys, ordinary people are increasingly tending to lose their cool in public.

Although anger is a potentially destructive emotion that uses up a lot of energy and creates a high level

of emotional and physical stress - and it stops us thinking rational. Consequently angry people often

end up saying, and doing things they later have cause to regret. So, how can anger be avoided? Firstly,

diet and lifestyle may be to blame. Tolerance and irritability certainly come to the surface when

someone hasn‘t slept properly or has skipped a meal, and any intake of caffeine can make things worst.

Take regular exercise can help to ease and diffuse feelings of aggression, however, reducing the

chances of an angry response. But if something or someone does make you angry, it‘s advisable not to

react immediately. Once you‘ve calmed down, things won‘t look half as badly as you first thought.

1. line 1: politics politician

Part 4. Fill in each blank with a suitable particle or preposition.

2. Don‘t forget the date. I‘m banking for your help.

3. It was decided to break up diplomatic relations with that country.

4. The police arrived immediately after the call and caught the burglar on the spot.

5. Over 3,000 workers were laid out when the company moved the factory abroad.

6. They worked very hard in their new business venture and their efforts eventually paid off .

7. As the day wore by , I began to feel more and more uncomfortable in their company.

8. There was strong evidence to suggest that the judge presiding the case had been bought offb .

9. It‘s like a bolt from the blue.

10. I didn‘t do much work, but I‘m

relieved that I scraped over my exam.

11. The unemployment data must be seen as the background of world recession.

III. READING

Part 1. Read the following passage and choose the correct word(s) to each of the questions.

Secretaries

What‘s in a name? In the case of the secretary, or Personal Assistant (PA), it can be something rather

surprising. The dictionary calls a secretary

―

anyone who handles correspondence, keeps recor

ds

and

does clerical work for others‖. But while this particular job (1)

_ looks a bit outdated, the word‘s

original meaning is a hundred times more exotic and perhaps more appropriate. The word itself has

been with us since the 14

th

century and comes from the medieval Latin word secretarius meaning

―

something

hidden‖

. Secretaries started out as those members of staff with knowledge hidden

from others, the silent ones mysteriously (2) the secret machinery of organizations.

Some years ago

―

something hidden

‖

probably meant (3) out of

si

ght, tucked a

wa

y with all the

other secretaries and typists. A good secretary was an unremarkable one, efficiently (4)

orders,

and then returning mouse-like to his or her station behind the typewriter, but, with the (5) of new

office technology, the job (6) upgraded itself and the role has changed to one closer to the

original meaning. The skills required are more demanding and more technical. Companies are (7)

that secretarial staff should already be (8)

trained in, and accustomed to working with, a

(9) of word processing packages. In addition to this, they need the management skills to take on

some administration, some personnel work and some research. The professionals in the (10)

business point out that nowadays secretarial staff may even need some management skills to take on

administration, personnel work and research.

1. A. explanation B. detail C. definition D. characteristic

2. A. operating B. pushing C. vibrating D. effecting

3. A. kept B. covered C. packed D. held

4. A. satisfying B. obeying C. completing D. minding

5. A. advent B. approach C. entrance D. opening

6. A. truly B. validly C. correctly D. effectively

7. A. insisting B. ordering C. claiming D. pressing

8. A. considerably B. highly C. vastly D. supremely

9. A. group B. collection C. cluster D. range

10. A. appointment B. hiring C. recruitment D. engagement

Part 2. Fill in each numbered blank with one suitable word to complete the passage.

My new friend’s a robot

In fiction robots have a personality, (1) but reality is disappointingly different. Although

sophisticated (2) enough to assemble cars and assist during complex surgery, modern robots are

dumb automatons, (3) incapable of striking up relationships with their human

operators.

However, change is (4) on the horizon. Engineers argue that, as robots begin to make (5)

up a bigger part of society, they will need a way to interact with humans. To this end they

will need artificial personalities. The big question is this: what does a synthetic companion need to have

so that you want to engage (6) with it over a long period of time? Phones and computers have

already shown the (7) extent to which people can develop relationships with inanimate electronic

objects.

Looking further (8) ahead , engineers envisage robots helping around the house, integrating

with the web to place supermarket orders using email. Programming the robot with a human–like

persona and (9) giving it the ability to learn its users‘ preferences, will help the person feel (10)

at ease with it. Interaction with such a digital entity in this context is more natural than

sitting with a mouse and keyboard.

Part 3. Read the following passage and choose the correct answer to each of the questions.

Birds that feed in flocks commonly retire together into roosts. The reasons for roosting communally

are not always obvious, but there are some likely benefits. In winter especially it is important for birds

to keep warm at night and conserve precious food reserves. One way to do this is to find a sheltered

roost. Solitary roosters shelter in dense vegetation or enter a cavity - horned larks dig holes in the

ground and ptarmigan burrow into snow banks - but the effect of sheltering is magnified by several

birds huddling together in the roosts, as wrens, swifts, brown creepers, bluebirds and anis do. Body

contact reduces the surface area exposed to the cold air, so the birds keep each other warm. Two

kinglets huddling together were found to reduce their heat losses by a quarter, and three together saved

a third of their heat.

The second possible benefit of communal roosts is that they act as

―

information centers

‖

. During the

day, parties of birds will have spread out to forage over a very large area. When they return in the

evening some will have fed well, but others may have found little to eat. Some investigators have

observed that when the birds set out again next morning, those birds that did not feed well on the

previous day appear to follow those that did. The behavior of common and lesser kestrels may illustrate

different feeding behaviors of similar birds with different roosting habits. The common kestrel hunts

vertebrate animals in a small, familiar hunting ground, whereas the very similar lesser kestrel feeds on

insects over a large area. The common kestrel roosts and hunts alone, but the lesser kestrel roosts and

hunts in flocks, possibly so one bird can learn from others where to find insect swarms.

Finally, there is safety in numbers at communal roosts since there will always be a few birds awake

at any given moment to give the alarm. But this increased protection is partially counteracted by the

fact that mass roosts attract predators and are especially vulnerable if they are on the ground. Even

those in trees can be attacked by birds of prey. The birds on the edge are at greatest risk since predators

find it easier to catch small birds perching at the margins of the roost.

1. What does the passage mainly discuss?

A. How birds find and store food. B. How birds maintain body heat in the winter.

C. Why birds need to establish territory. D. Why some species of birds nest together.

2. The word

―

c

onserv

e

‖

in the first paragraph is closest in meaning to

_.

A. retain B. watch C. locate D. share

3. Ptarmigan keep warm in the winter by .

A. building nests in trees B. huddling together on the ground with other birds

C. digging tunnels into the snow D. burrowing into dense patches of vegetation

List of Headings

i Different accounts of the same journey

ii Bingham gains support

iii A common belief

iv The aim of the trip

v A dramatic description

vi A new route

vii Bingham publishes his theory

viii Bingham‘s lack of enthusiasm

4. The word

―

magnified

‖

in the first paragraph is closest in meaning to .

A. combined B. caused C. modified D. intensified

5. The author mentions kinglets in the passage as an example of birds that .

A. protect themselves by nesting in holes B. usually feed and nest in pairs

C. nest together for warmth D. nest with other species of birds

6. Which of the following statements about lesser and common kestrels is TRUE?

A. The lesser kestrel feeds sociably but the common kestrel does not.

B. The lesser kestrel and the common kestrel have similar diets.

C. The common kestrel nests in larger flocks than does the lesser kestrel.

D. The common kestrel nests in trees; the lesser kestrel nests on the ground.

7. The word

―

forage

‖

in the passage

is

c

losest

in meaning to .

A. fly B. assemble C. feed D. rest

8. Which of the following is NOT mentioned in the passage as an advantage derived by birds that

huddle together while sleeping?

A. Some members of the flock warn others of impending dangers.

B. Staying together provides a greater amount of heat for the whole flock

C. Some birds in the flock function as information centers for others who are looking for food.

D. Several members of the flock care for the young.

9. Which of the following is a disadvantage of communal roosts that is mentioned in the passage?

A. Diseases easily spread among the birds. B. Food supplies are quickly depleted.

C. Some birds in the group will attack the others.

D. Groups are more attractive to predators than individual birds are.

10. The word

―

th

ey

‖

in the third paragraph refers to .

A. a few birds B. mass roosts C. predators D. trees

Part 4. Read the passage including seven paragraphs and do the following tasks.

Task 1. Choose the correct heading for each paragraph from the list of headings below. Write the

correct number, i-viii, in boxes 1-5 below.

Paragraphs Your answers:

Paragraph A iv

1. Paragraph B …vi……….

2. Paragraph C ……viii…….

3. Paragraph D ……v…….

4. Paragraph E ……i…….

5. Paragraph F ……vii…….

Paragraph G iii

The Lost City

An explorer’s encounter with the ruined city of Machu Picchu, the most famous icon of the Inca

civilisation

A When the US explorer and academic Hiram Bingham arrived in South America in 1911, he was

ready for what was to be the greatest achievement of his life: the exploration of the remote hinterland to

the west of Cusco, the old capital of the Inca empire in the Andes mountains of Peru. His goal was to

locate the remains of a city called Vitcos, the last capital of the Inca civilisation. Cusco lies on a high

plateau at an elevation of more than 3,000 metres, and Bingham‘s plan was to descend from this

plateau along the valley of the Urubamba river, which takes a circuitous route down to the Amazon and

passes through an area of dramatic canyons and mountain ranges.

B When Bingham and his team set off down the Urubamba in late July, they had an advantage over

travellers who had preceded them: a track had recently been blasted down the valley canyon to enable

rubber to be brought up by mules from the jungle. Almost all previous travellers had left the river at

Ollantaytambo and taken a high pass across mountains to rejoin the river lower down, thereby cutting a

substantial corner, but also therefore never passing through the area around Machu Picchu.

C On 24 July they were a few days into their descent of the valley. The day began slowly, with

Bingham trying to arrange sufficient mules for the next stage of the trek. His companions showed no

interest in accompanying him up the nearby hill to see some ruins that a local farmer, Melchor Arteaga,

had told them about the night before. The morning was dull and damp, and Bingham also seems to

have been less than keen on the prospect of climbing the hill. In his book Lost City of the Incas, he

relates that he made the ascent without having the least expectation that he would find anything at the

top.

D Bingham writes about the approach in vivid style in his book. First, as he climbs up the hill, he

de

sc

ribe

s

the ever-pre

se

nt

possi

bility of deadly snakes,

―

capable of making considerable springs when