70 PROFICIENCY & CPE

ENGLISH READING

EXERCISES

Student Edition

Introduction

Thank you for buying "70 Proficiency and CPE English Reading Exercises:

Student Edition". I'm sure that you with find this collection of 70 different pieces

of writing not only very useful for improving your level of English but also interesting

to read too (I've specially chosen the topic of each text for this purpose). Below I will

explain a little about what you have bought, who it is for, how the exercises are

ordered, what parts of your English it will improve and what is the best way to do the

reading exercises in this eBook.

What you have bought

In the eBook, there are 70 different reading exercises. Each reading exercise has its

own text (mainly articles, but also a variety of other types of text like essays, reviews

etc...). The length of each text varies, although none is shorter than 1,000 words.

After each text is a vocabulary exercise for you to learn and remember 7 phrases and

words from the text. After this there a page for you to write a sentence in your own

words for each of these words and phrases once you have learnt the meaning of

them.

On the following 6 pages you will find a list of the 70 different reading exercises and

on which pages you can find each on.

1

List of exercises

Below you will find the names of the 70 different reading exercises that are included in this eBook and

the page where you can find each.

In addition, for each exercise it tells you what topics are used in the text. This is especially useful if you

want to improve the knowledge of specific topics for your students and the associated English

vocabulary used in them.

Number

Title

Topics

Page

1 The intelligence of plants

Nature, plants &

science

13

2

Superstitions and their strange

origins

Culture & history

19

3

Jordan: A spectacular country with

unfortunately too few tourists

Travel, culture &

nature

24

4

The myth of meritocracy in

education

Education &

society

29

5

The comparative failure of online

grocery shopping

Business,

technology &

society

35

6

Can fashion be considered to be

art?

The arts & fashion

42

7

Ten inventions that radically

changed our world

Inventions, history

& society

47

8

What makes solo endurance

athletes keep going?

Sport &

psychology

53

9

Is human habitation on Mars

possible?

Astronomy &

science

58

10

The questionable validity and

morality of using IQ tests

Psychology &

society

64

11

Is wind power the answer for our

future energy needs?

The environment

& energy

70

12 The history of astrology

Science,

astronomy, history

& psychology

75

2

List of exercises (continued)

Number

Title

Topics

Page

13

Our changing spending habits at

Christmas

Economics &

business

81

14 The importance of stories for us

The arts, literature,

culture & history

86

15

Is lab-grown meat a good thing for

us?

Food/drink,

science,

technology &

business

91

16

Is there any difference between

men’s and women’s brains?

Science,

psychology,

health & society

97

17

ASMR: Making money through

making very soft sounds

Technology,

culture & business

102

18

Why many of us don’t really work

when at work

Work, business &

society

107

19

The worrying disappearance of the

right to free speech at British

universities

Society, education

& philosophy

113

20

Changing the image of classical

music

The arts, music &

culture

118

21

The discovery which is reshaping

the theory of our origins

Anthropology &

archaeology

122

22 Sleep and its importance

Science, human

biology & health

127

23

Wealth and happiness: Are the two

connected?

Economics,

society & life

132

24

Punishing the parents for their kids

underage drinking

Society, health &

law

137

25

Reintroducing wolves and other

lost species back into the wild in

Britain

Nature, animals &

the environment

143

3

List of exercises (continued)

Number

Title

Topics

Page

26

Everest and death: Why people

are still willing to climb mountain of

the dead

Sport, society,

physical

geography &

psychology

150

27

The debate on whether being

overweight is unhealthy

Medicine, science

& health

157

28

The importance of Conrad’s ‘The

Heart of Darkness’

The arts, literature,

culture & history

163

29

The resistance to moving from

steam power to electricity in

manufacturing

Science, history &

economics

169

30 The significance of colour

Culture, design,

business,

psychology &

history

174

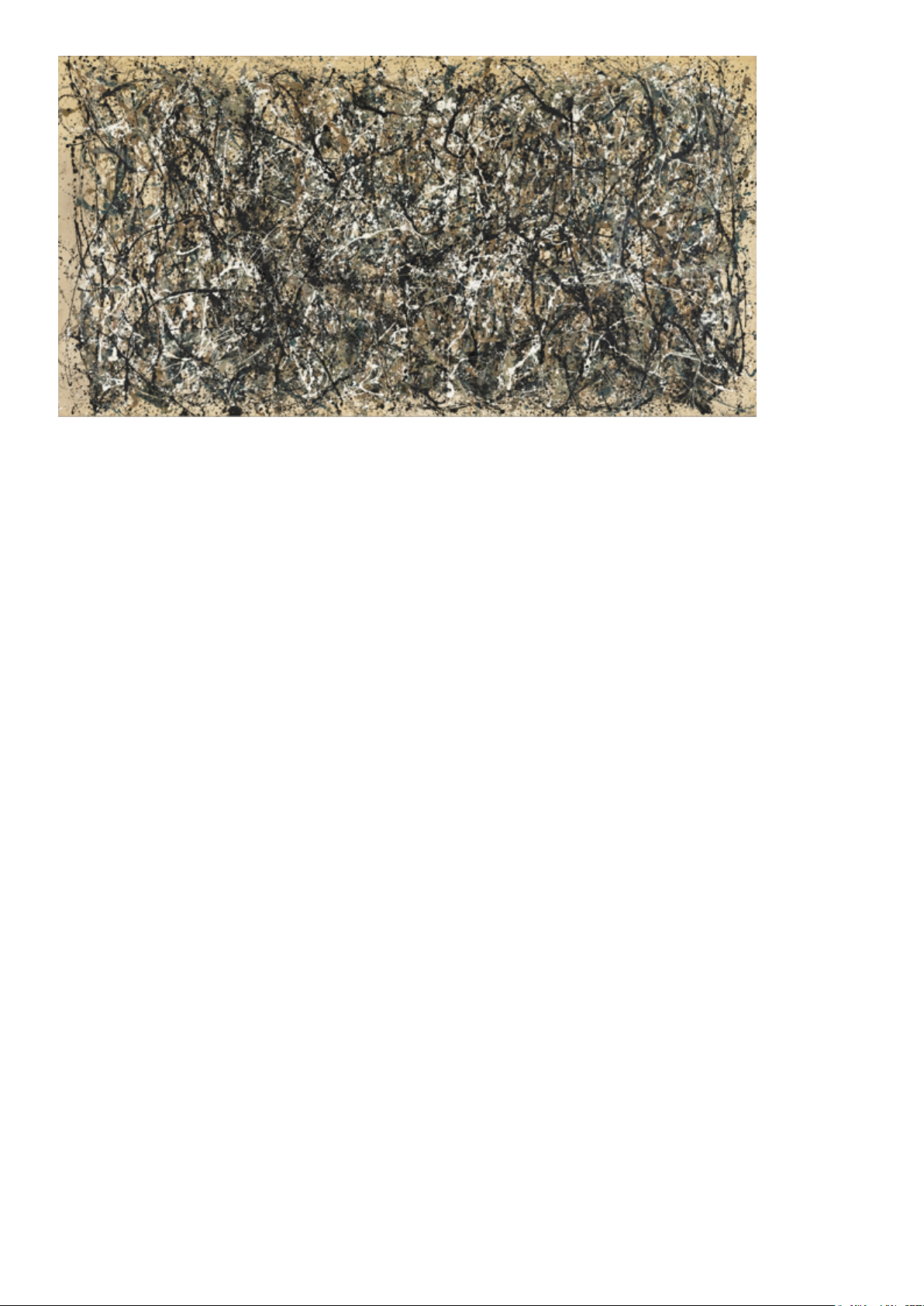

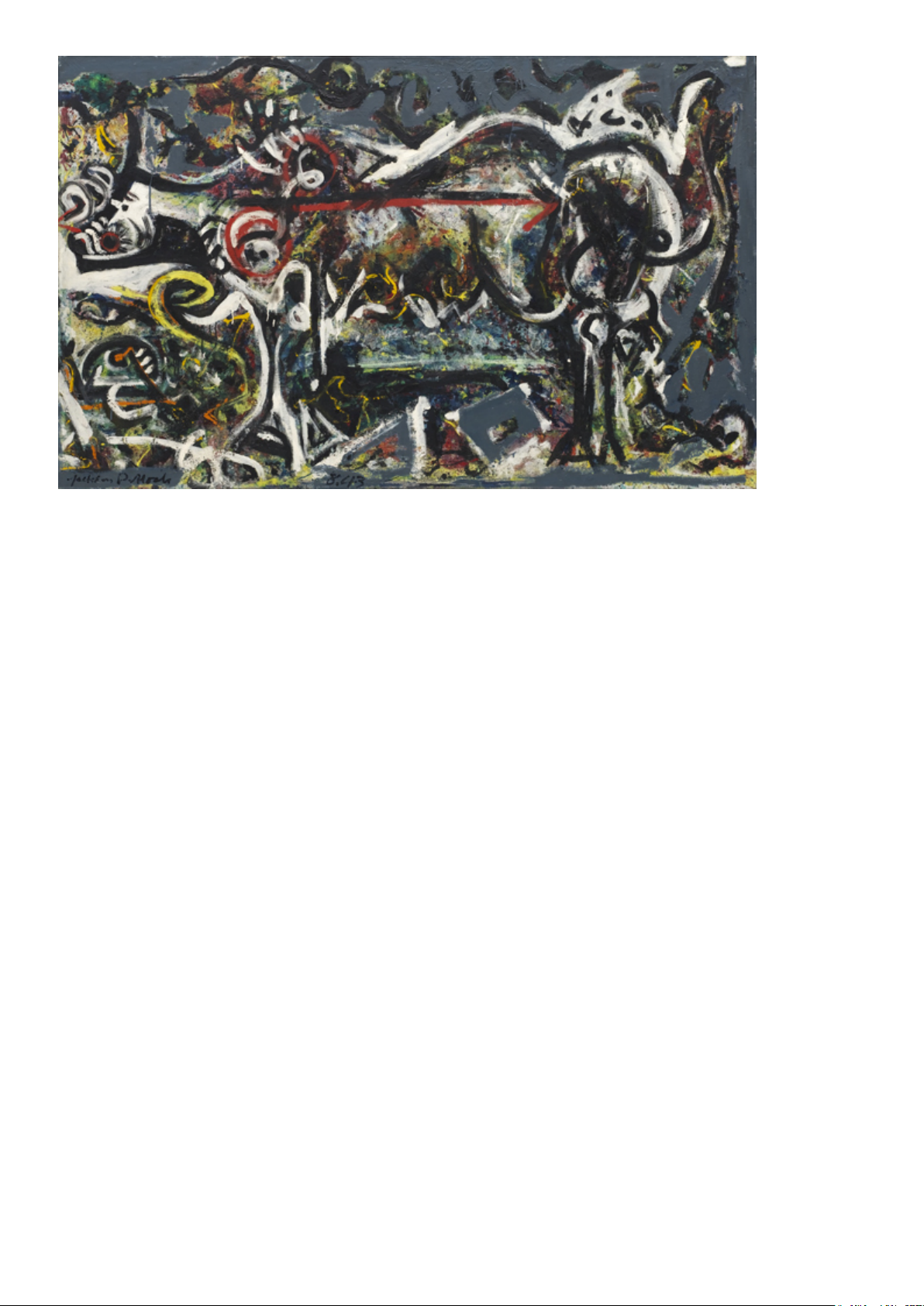

31 The work of artist Jackson Pollock

The arts, painting

& culture

182

32 Food imagery and manipulation

Psychology,

food/drink &

media

190

33

The urgency of acting now to stop

climate change

The environment

& nature

197

34

Trying to reverse the declining

demand for humanities majors in

America

Education &

university

205

35

How the tulip caused the world’s

first economic crash

Economics,

history & painting

210

36

A review of the film "Three

Billboards Outside Ebbing,

Missouri"

The arts & film

215

37

Our personality traits appear to be

mostly inherited

Psychology &

science

219

38

Is it right for people to go to Africa

to hunt?

Nature, society &

business

225

4

List of exercises (continued)

Number

Title

Topics

Page

39

The new palaces of the 21st

century

Architecture,

society & culture

232

40

Understanding contemporary

dance

The arts, dance &

history

238

41 America’s six best hiking trails

Travel, nature &

physical

geography

243

42

Why the disappearance of

livestock farming is good for us all

The environment

& farming

250

43 Can we trust our memories?

Science,

psychology &

health

255

44

Why Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein is

still relevant today

The arts, literature

& culture

260

45

Customer complaints are good for

business

Business

266

46

How the discovery of plate

tectonics revolutionised are

understanding of our planet

Science, geology

& history

271

47

Is there a conflict between saving

the planet and reducing poverty?

Society & the

environment

275

48 No more rock stars anymore

The arts, music &

technology

280

49

Are the rich better than the rest of

us?

Psychology &

society

286

50

Globalisation and how societies

have always evolved

Culture, society &

history

291

51

The reasons for the decline in wine

consumption in France

Food/drink,

culture & society

297

52

The merits of being a fair-weather

sports fan

Sport, society &

culture

302

5

List of exercises (continued)

Number

Title

Topics

Page

53

The reason why homeopathic

treatment does work with patients

Medicine &

science

307

54

Is the gentrification of parts of

cities a really bad thing?

Society,

economics &

human geography

312

55 The origins of the metric system

Science & history

318

56 Do prisons work?

Crime, society,

history & law

323

57

All you need to know about

depression

Science,

psychology &

health

329

58 The future of work

Work, technology

& society

334

59

The difficulties for us to colonise

the galaxy

Astronomy,

science, health &

technology

340

60

The shredding of Banksy’s “Girl

With Balloon” at auction: Stunt or

statement?

The arts, painting

& culture

345

61

Why a decline in the planet’s

biodiversity is a threat to us all

Nature & the

environment

350

62

Should we profile people in society

to predict behaviour?

Psychology,

society & crime

356

63

A review of Vincent LoBrutto’s

biography of Stanley Kubrick

The arts, film &

reviews

361

64

Is free trade between countries a

good thing?

Economics

366

65

Is freshwater the biggest challenge

we will face this century?

The environment,

society & physical

geography

372

66

The problems of relying on metrics

to gauge performance

Statistics,

business & work

378

6

List of exercises (continued)

Number

Title

Topics

Page

67

Should you use the carrot or the

stick with your children?

Psychology &

family

382

68

Stefan Zweig: The life of a citizen

of the world

The arts, literature,

culture & society

387

69

The evolution of science and

thought throughout the ages part 1

Science, history,

innovation,

society &

philosophy

392

70

The evolution of science and

thought throughout the ages part 2

Science, history,

innovation,

society &

philosophy

398

7

Who this eBook is for

The reading exercises (the texts and vocabulary exercises) in this eBook have been

specifically designed for people who have a proficiency level of English (higher C1 or

C2), are studying for the Cambridge Certificate of Proficiency in English (CPE) exam

or students who are looking to obtain a 8-9 mark in IELTS exams.

The texts have either been adapted or written for the needs of students learning

English at this level. What this means is that you should be able to easily understand

what the piece of text you are reading is about, but at the same time find parts of it

challenging (specifically with some of the vocabulary you are going to encounter in

the text). You are going to come across some vocabulary (but not too much, so you

get frustrated) which you are very likely not to have encountered before in English.

Vocabulary which you need to know and understand at this level.

The words and phrases in the vocabulary exercises have been specifically chosen

from each of the texts that you will read. The words and phrases in each vocabulary

exercise are ones which I have frequently noticed that students at this level don't

know, don't use or use incorrectly. In addition, the majority of these words and

phrases are ones which you will both see and be able to use in a variety of different

contexts.

The reading exercises in this eBook are not really appropriate for people who have

lower levels of English (upper-Intermediate, advanced or CAE). People who have

these levels of English will find the majority of the texts too difficult and likely

become frustrated.

How the exercises are ordered

Unlike our other reading exercise books (for intermediate/FCE and advanced/CAE

levels) the texts in the reading exercises contained in this eBook don't get

progressively more difficult (i.e. the text in reading exercise 1 isn't necessarily less

challenging than and the text in exercise 34 or 70). So you can do them in which ever

order you want.

You will probably find some of the reading exercises more challenging than others,

but this isn't necessarily down to the vocabulary used them, but because of the

knowledge you have of the topic(s) discussed in them. But due to there being other

reading exercises on each of the topics throughout the eBook, you should improve

your knowledge of the topic and its vocabulary the more reading exercises you do.

8

By all means miss out doing reading exercises if you don't think they are necessary

for yourself (that's why I've included 70 different exercises in this eBook, so you have

a choice of which to use).

What it will help you improve

The reading exercises that you will find here have been designed to improve your

English in a number of different areas.

Reading

By reading each text in the exercises, you will become more comfortable at reading

and understanding a range of different complex pieces of writing in English.

Vocabulary

You'll not only learn the meaning and use of advanced vocabulary in the vocabulary

exercises, but you'll also broaden your overall knowledge of English vocabulary. The

reading exercises cover a wide variety of different topics (from science to art). So,

you'll read about many topics which you otherwise wouldn't and learn the vocabulary

used when talking about them. And although broadening vocabulary is important for

everyone who wants to improve their level of English, it is especially important for

people doing exams (e.g. CPE, IELTS etc...).

Grammar

Although there are no grammar exercises in this eBook, the reading of the different

texts will reinforce your knowledge and use of both complex and simple grammatical

structures. The more you see grammatical structures being used, the more likely you

are to use them correctly yourself.

Writing

Although the focus of these exercises is on improving reading skills and vocabulary,

you can use the different texts to improve your own writing. To do this, you should

look at the different texts and see how they are structured (what comes first, second,

third etc...), how the different paragraphs are linked together and how the texts flow

(how the writers order the different things they talk about, to keep the people reading

them both interested and not confused). In addition, some of the vocabulary you will

learn in the vocabulary exercises is commonly used in written English.

9

The best way to use this eBook

Although you can do the reading exercises in this eBook however you like, I'm going

to recommend a method to use which will help you to improve your English more

quickly and effectively.

Read the text

The first thing to do is to read the text of each reading exercise. But before you do,

make sure you read the summary (which explains what the text is about) at the

beginning of the text. The reason why you need to read this first is that it will make

reading the text both quicker and easier.

Then read the text. The first time you read the text, you are doing it to understand

what it is talking about. Don't worry if you don't understand what all the vocabulary

means. If there are words and phrases you don't know or are confused with,

underline or highlight them (so you remember what they are). But don't think too

long about what they mean when first reading the text. You can do that later (I'll

explain when later).

Do the vocabulary exercise

After you have finished reading the text, have a break of about 5 to 10 minutes. Then

look at the vocabulary exercise of the text that you have just read.

In this part you are going to learn 7 words or phrases from the text you have just

read. You are going to learn what each of these mean and in what situations they are

used in. You will find that each word or phrase is in a sentence (or sentences) taken

from the text. Guess from the context (the sentence(s) in which the word or phrase is

in) what the meaning of the word or phrase is. When you think that you know what it

means, check in a dictionary to make sure that you are right.

After you have done this, create your own sentence with the word/phrase in your

mind (don't write it down) and say it out loud.

Remember when you do this, to use the same context in your own sentence that the

word or phrase is in from the text.

Do the same process for all the words and phrases.

Write your own sentences

The following day (not on the same day), write a sentence for the each of the 7 words

or phrases that you learnt from the vocabulary exercise. Write the sentences on the

page after the vocabulary exercise called "Write your own sentences with the

10

vocabulary". You can write the same sentence you created the day before or a

different sentence, it is your choice.

This eBook has been designed so that you can write the sentence you have created

directly in the eBook (in the coloured box below each word or phrase). This means

that you don't have to print out the reading exercise and it also makes it easier to find

and reread the sentences you have written in the future.

To write your sentences directly in the eBook, you need to open it with the Adobe

Acrobat application. Although you can open and read this eBook in many

different applications, most of them won't allow you to write directly into the eBook.

After you have written each sentence, read it out aloud again.

Why do all of this?

The main reason to do all of this is that it will make sure that you remember both the

meaning of the words or phrases and when they are used. I have tested this method

with people learning English and the ones who use it remember and use the words

and phrases a lot more than those that don't.

Look at the other words you don't know

It is your choice if you do this or not, but after you have done the sentences in the

vocabulary exercise you can look at the words and phrases that you underlined or

highlighted when you were reading the text. Use a similar process to learning and

remembering their meanings as you did with the vocabulary you learnt in the

vocabulary exercise (guess their meaning from the context, check in a dictionary,

create your own sentence etc...).

And that's it

That's all you have to do. I appreciate that after reading all this, it may seem like

there's a lot you have to do. But when you get used to doing it, it won't take you long

at all to do.

11

Use of the content

Please remember it's taken me a lot of time and effort to produce this eBook and all

the material in it. So I would really appreciate it if you didn't give copies of it to other

people. If you choose to do it, it will mean less people will buy it from me. This will

make it harder for me to dedicate my time to producing more of this type of content

in the future.

Although I'm sure that the majority of you won't do this, I have to stipulate what you

are legally not able to do with the content in this eBook. You are not permitted to

rebrand the eBook or content (or any part of it) as your own or resell it. In addition,

you are not allowed to publish the content or provide a link to download the content

or eBook for free on a digital medium (e.g. on a website, social media network etc...).

I apologise for having to do this, but I have to legally protect my rights.

If you have any questions about this or about anything connected to this eBook,

please don't hesitate to contact me (Chris) at contact@blairenglish.com.

12

EXERCISE 1

The intelligence of plants

Summary

This article discusses the increasing evidence that plants have a form of intelligence. Talking to a

co-author of a book on the subject, it explains why this is the case and why this hasn't really been

researched into in the past. It also says what the importance of plants is to our survival and that we

really need to start paying them more attention.

Plants are intelligent. Plants deserve rights. Plants are like the Internet – or more accurately the

Internet is like plants. To most of us these statements may sound, at best, insupportable or, at

worst, crazy. But a new book, Amazing Plants: the Intelligence of plants, by plant neurobiologist

(yes, plant neurobiologist), Stefano Rivili and journalist, Alessandra Vickers, makes a compelling

and fascinating case not only for plant sentience and smarts, but also plant rights.

For centuries Western philosophy and science largely viewed animals as unthinking automatons,

simple slaves to instinct. But research in recent decades has shattered that view. We now know

that not only are chimpanzees, dolphins and elephants thinking, feeling and personality-driven

beings, but many others are as well. Octopuses can use tools, whales sing, bees can count, crows

demonstrate complex reasoning, paper wasps can recognise faces and fish can differentiate types

of music. All these examples have one thing in common: they are animals with brains. But plants

don't have a brain. How can they solve problems, act intelligently or respond to stimuli without a

brain?

"Today's view of intelligence - as the product of the brain in the same way that urine is of the

kidneys - is a huge oversimplification. A brain without a body produces the same amount of

intelligence of the nut that it resembles," said Rivili, who as well as co-writing Amazing Plants, is

the director of the Institute of Plant Neurobiology in Milan.

As radical as Rivili's ideas may seem, he's actually in good company. Charles Darwin, who studied

plants meticulously for decades, was one of the first scientists to break from the crowd and

recognise that plants move and respond to sensation – i.e., are sentient. Moreover, Darwin – who

studied plants meticulously for most of his life, observed that the radicle – the root tip – "acts like

the brain of one of the lower animals."

Plant problem solvers

Plants face many of the same problems as animals, though they differ significantly in their

approach. Plants have to find energy, reproduce and stave off predators. To do these things, Rivili

argues, plants have developed smarts and sentience. "Intelligence is the ability to solve problems

and plants are amazingly good at solving their problems," Rivili noted. To solve their energy needs,

most plants turn to the sun – in some cases literally. Plants are able to grow through shady areas to

locate light and many even turn their leaves during the day to capture the best light. Some plants

have taken a different route, however, supplying themselves with energy by preying on animals,

including everything from insects to mice to even birds. The Venus flytrap may be the most famous

13

of these, but there are at least 600 species of animal-eating flora. In order to do this, these plants

have evolved complex lures and rapid reactions to catch, hold and devour animal prey.

Plants also harness animals in order to reproduce. Many plants use complex trickery or provide

snacks and advertisements (colours) to lure in pollinators, communicating either through direct

deception or rewards. New research finds that some plants even distinguish between different

pollinators and only germinate their pollen for the best.

Finally, plants have evolved an incredible variety of toxic compounds to ward off predators. When

attacked by an insect, many plants release a specific chemical compound. But they don't just throw

out compounds, but often release the precious chemical only in the leaf that's under attack. Plants

are both tricky and thrifty.

"Each choice a plant makes is based on this type of calculation: what is the smallest quantity of

resources that will serve to solve the problem?" Rivili and Vickers write in their book. In other

words, plants don't just react to threats or opportunities, but must decide how far to react.

The bottom of the plant may be the most sophisticated of all though. Scientists have observed that

roots do not flounder randomly but search for the best position to take in water, avoid competition

and garner chemicals. In some cases, roots will alter course before they hit an obstacle, showing

that plants are capable of "seeing" an obstacle through their many senses. Humans have five basic

senses. But scientists have discovered that plants have at least 20 different senses used to monitor

complex conditions in their environment. According to Rivili, they have senses that roughly

correspond to our five, but also have additional ones that can do such things as measure humidity,

detect gravity and sense electromagnetic fields.

Plants are also complex communicators. Today, scientists know that plants communicate in a wide

variety of ways. The most well known of these is chemical volatiles – why some plants smell so

good and others awful – but scientists have also discovered that plants also communicate via

electrical signals and even vibrations. "Plants are wonderful communicators: they share a lot of

information with neighbouring plants or with other organisms such as insects or other animals.

The scent of a rose, or something less fascinating as the stench of rotting meat produced by some

flowers, is a message for pollinators."

Many plants will even warn others of their species when danger is near. If attacked by an insect, a

plant will send a chemical signal to their fellows as if to say, "hey, I'm being eaten – so prepare

your defences." Researchers have even discovered that plants recognize their close kin, reacting

differently to plants from the same parent as those from a different parent. "In the last several

decades science has been showing that plants are endowed with feeling, weave complex social

relations and can communicate with themselves and with animals," write Rivili and Vickers, who

also argue that plants show behaviours similar to sleeping and playing.

And it turns out Darwin was likely right all along. Rivili has found rising evidence that the key to

plant intelligence is in the radicle or root apex. Rivili and colleagues recorded the same signals

given off from this part of the plant as those from neurons in the animal brain. One root apex may

not be able to do much. But instead of having just one root, most plants have millions of individual

roots, each with a single radicle.

So, instead of a single powerful brain, Rivili argues that plants have a million tiny computing

structures that work together in a complex network, which he compares to the Internet. The

strength of this evolutionary choice is that it allows a plant to survive even after losing 90% or

more of its biomass. "The main driver of evolution in plants was to survive the massive removal of

14

a part of the body," said Rivili. "Thus, plants are built of a huge number of basic modules that

interact as nodes of a network. Without single organs or centralised functions plants may tolerate

predation without losing functionality. The Internet was born for the same reason and, inevitably,

reached the same solution."

Having a single brain – just like having a single heart or a pair of lungs – would make plants much

easier to kill. "This is why plants have no brain: not because they are not intelligent, but because

they would be vulnerable," Rivili said. "In this way, it may be better to think of a single plant as a

colony, rather than an individual. Just as the death of one ant doesn't mean the demise of the

colony, so the destruction of one leaf or one root means the plant still carries on."

The wide gulf

So, why has plant sentience – or if you don't buy that yet, plant behaviour – been ignored for so

long? Rivili says this is because plants are so drastically different from us. For example, plants

largely live on a different timescale than animals, moving and acting so slowly that we hardly

notice they are, indeed, reacting to outside stimuli. Consequently, it is "impossible" for us to put

ourselves in the place of a plant. "We are too different; the fruit of two diverse evolutive

tracks...plants would appear very different to us," he says. "But at the same time, we have things in

common with them too. For example, we both have the same needs to survive and we evolved on

the same planet as well. We pretty much respond in the same way to the same impulses."

But due to these vast differences, Rivili says, plants fail to attract interest in the same way as, say, a

tiger or an elephant. "The love for plants is an adult love. It is almost impossible to find a baby

interested in plants; they love animals," he said. "No child thinks that a plant is funny. And for me

it was no different: I began to be interested in plants during my doctorate when I realised that they

were capable of surprising abilities."

This has resulted in very few researchers studying plant behaviour or intelligence, unlike queries

into animals. "Today the vast majority of the plant scientists are molecular biologists who know [as

much] about the behaviour of plants as much as I know of cricket," said Rivili. "We take plants for

granted. Expecting that they will always be there, not worrying or even considering the possibility

that one might not be."

Yet, humankind's disinterest and dispassion about plant behaviour and intelligence may be to our

detriment, and put our own very survival at stake.

Totally dependent on plants

Whilst plants are by no means as diverse as the world's animals (no one beats beetles for

diversity), they have truly conquered the world. Today, plants make up more than 99 percent of

biomass on the planet. Think about that: this means all the world's animals – including ants, blue

whales, and us – make up less than one percent. "So we depend on plants, thus plant conservation

is necessary for man's conservation," said Rivili.

Yet, human actions – including deforestation, habitat destruction, pollution, climate change, etc. –

have ushered in a mass extinction crisis. While plants in the past have fared better in previous

mass extinctions, there is no guarantee they will this time. "Every day a consistent number of plant

species that we have never encountered, disappears," noted Rivili.

At the same time, we don't even know for certain how many plant species exist on the planet.

Currently, scientists have described around 20,000 species of plants. But there are probably more

unknown than known. "We have no idea about the number of plant species living on the planet.

15

There are different estimates saying we know from 10 to 50% (no more) of the existing plants,"

said Rivili. Many of these could be wiped out without ever being described, especially as

unexplored rainforests and cloud forest – the most biodiverse communities on the planet –

continue to fall in places like Brazil, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo

and Papua New Guinea, among others.

Yet, we depend on plants not only for many of our raw materials and our food, but also for the

oxygen we breathe and, increasingly it seems, the rain we require. Plants drive many of the

biophysical forces that make the Earth habitable for humans – and all animals.

"Sentient or not sentient, intelligent or not, the life of the planet is green...The life on the Earth is

possible just because plants exist," said Rivili. "Is not a matter of preserving plants: plants will

survive. The conservation implications are for humans: fragile and dependent organisms."

Still, there are few big conservation groups working directly on plants – most target the bigger,

fluffier and more publicly appealing animals. Much like plant behaviour research, plant

conservation has been little-funded and long-ignored.

Rivili says the state of plant conservation and the rising evidence that plants are sentient beings

should make people consider something really radical: plants' rights. "It is my opinion that a

discussion about plants' rights is no longer deferrable. I know that the first reaction, even of the

more open-minded people, will be 'Jeez! He's exaggerating now. Plant's right is nonsense,' but

should we not care? After all the reaction of the Romans' to the proposal of rights for women and

children, was no different. The road to rights is always difficult, but it is necessary. Providing rights

to plants is a way to prevent our extinction."

16

Vocabulary exercise

1. lure (paragraph 6)

Plants also harness animals in order to reproduce. Many plants use complex trickery or provide

snacks and advertisements (colours) to lure in pollinators, communicating either through direct

deception or rewards.

2. ward off (paragraph 7)

Finally, plants have evolved an incredible variety of toxic compounds to ward off predators.

3. roughly (paragraph 9)

According to Rivili, they have senses that roughly correspond to our five, but also have additional

ones that can do such things as measure humidity, detect gravity and sense electromagnetic fields.

4. endowed with (paragraph 11)

In the last several decades science has been showing that plants are endowed with feeling, weave

complex social relations and can communicate with themselves and with animals

5. take plants for granted (paragraph 17)

We take plants for granted. Expecting that they will always be there, not worrying or even

considering the possibility that one might not be.

6. at stake (paragraph 18)

Yet, humankind's disinterest and dispassion about plant behaviour and intelligence may be to our

detriment, and put our own very survival at stake.

7. fared (paragraph 20)

While plants in the past have fared better in previous mass extinctions, there is no guarantee they

will this time.

17

Write your own sentences with the vocabulary

1. lure

2. ward off

3. roughly

4. endowed with

5. take plants for granted

6. at stake

7. fared

18

EXERCISE 2

Superstitions and their strange origins

Summary

This is an article which explains the historical origins of 9 commonly held superstitions (things

which are lucky or unlucky to do) in the Anglo-Saxon world.

Some superstitions are so ingrained in modern English-speaking societies that everyone, even

scientists, succumb to them (or, at least, feel slightly uneasy about not doing so). So why don't we

walk under ladders? Why, after voicing optimism, do we knock on wood? Why do non-religious

people "God bless" a sneeze? And why do we avoid at all costs opening umbrellas indoors? Is there

a logical explanation for them?

If you know what these superstitions originally emanated from, you’ll find that there kind of is.

And this is what you’re going to learn below for both the aforementioned and five other common

superstitious customs we have.

It's bad luck to open an umbrella indoors

Though some historians tentatively trace this belief back to ancient Egyptian times, the

superstitions that surrounded pharaohs' sunshades were actually quite different and probably

unrelated to the modern-day one about rain gear. Most historians think the warning against

unfurling umbrellas inside originated much more recently, in Victorian England.

In "Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things", the scientist and author Charles Panati wrote: "In

eighteenth-century London, when metal-spoked waterproof umbrellas began to become a common

rainy-day sight, their stiff, clumsy spring mechanism made them veritable hazards to open

indoors. A rigidly spoked umbrella, opening suddenly in a small room, could seriously injure an

adult or a child, or shatter a frangible object. Even a minor accident could provoke unpleasant

words or a minor quarrel, themselves strokes of bad luck in a family or among friends. Thus, the

superstition arose as a deterrent to opening an umbrella indoors."

It's bad luck to walk under a leaning ladder

This superstition really does originate 5,000 years ago in ancient Egypt. A ladder leaning against a

wall forms a triangle, and Egyptians regarded this shape as sacred (as exhibited, for example, by

their pyramids). To them, triangles represented the trinity of the gods, and to pass through a

triangle was to desecrate them.

This belief wended its way up through the ages. "Centuries later, followers of Jesus Christ usurped

the superstition, interpreting it in light of Christ's death," Panati explained. "Because a ladder had

rested against the crucifix, it became a symbol of wickedness, betrayal, and death. Walking under a

ladder courted misfortune."

In England in the 1600s, criminals were forced to walk under a ladder on their way to the gallows.

19

A broken mirror gives you seven years of bad luck

In ancient Greece, it was common for people to consult "mirror seers," who told their fortunes by

analyzing their reflections. As the historian Milton Goldsmith explained in his book "Signs, Omens

and Superstitions" (1918), "divination was performed by means of water and a looking glass. This

was called catoptromancy. The mirror was dipped into the water and a sick person was asked to

look into the glass. If their image appeared distorted, they were likely to die; if clear, they would

live."

In the first century A.D., the Romans added a caveat to the superstition. At that time, it was

believed that people's health changed in seven year cycles . A distorted image resulting from a

broken mirror therefore meant seven years of ill-health and misfortune, rather than outright

death.

When you spill salt, toss some over your left shoulder to avoid bad luck

Spilling salt has been considered unlucky for thousands of years. Around 3,500 B.C., the ancient

Sumerians first took to nullifying the bad luck of spilled salt by throwing a pinch of it over their left

shoulders. This ritual spread to the Egyptians, the Assyrians and later, the Greeks.

The superstition ultimately reflects how much people prized (and still prize) salt as a seasoning for

food. The etymology of the word "salary" shows how highly we value it. According to Panati: "The

Roman writer Petronius, in the Satyricon, originated 'not worth his salt' as opprobrium for Roman

soldiers, who were given special allowances for salt rations, called salarium 'salt money' the origin

of our word 'salary.'"

Knock on wood to prevent disappointment

Though historians say this may be one of the most prevalent superstitious customs in the United

States, its origin is very much in doubt. "Some attribute it to the ancient religious rite of touching a

crucifix when taking an oath," Goldsmith wrote. Alternatively, "among the ignorant peasants of

Europe it may have had its beginning in the habit of knocking loudly to keep out evil spirits."

Always 'God bless' a sneeze

In most English-speaking countries, it is polite to respond to another person's sneeze by saying

"God bless you." Though incantations of good luck have accompanied sneezes across disparate

cultures for thousands of years (all largely tied to the belief that sneezes expelled evil spirits), our

particular custom began in the sixth century A.D. by explicit order of Pope Gregory the Great.

A terrible pestilence was spreading through Italy at the time. The first symptom was severe,

chronic sneezing, and this was often quickly followed by death. [Is It Safe to Hold In a Sneeze?]

Pope Gregory urged the healthy to pray for the sick, and ordered that light-hearted responses to

sneezes such as "May you enjoy good health" be replaced by the more urgent "God bless you!" If a

person sneezed when alone, the Pope recommended that they say a prayer for themselves in the

form of "God help me!"

Hang a horseshoe on your door open-end-up for good luck

The horseshoe is considered to be a good luck charm in a wide range of cultures. Belief in its

magical powers traces back to the Greeks, who thought the element iron had the ability to ward off

20

evil. Not only were horseshoes wrought of iron, they also took the shape of the crescent moon in

fourth century Greece for the Greeks, a symbol of fertility and good fortune.

The belief in the talismanic powers of horseshoes passed from the Greeks to the Romans, and from

them to the Christians. In the British Isles in the Middle Ages, when fear of witchcraft was

rampant, people attached horseshoes open-end-up to the sides of their houses and doors. People

thought witches feared horses, and would shy away from any reminders of them.

A black cat crossing your path is lucky/unlucky

Many cultures agree that black cats are powerful omens but do they signify good or evil?

The ancient Egyptians revered all cats, black and otherwise, and it was there that the belief began

that a black cat crossing your path brings good luck. Their positive reputation is recorded again

much later, in the early seventeenth century in England: King Charles I kept (and treasured) a

black cat as a pet. Upon its death, he is said to have lamented that his luck was gone. The supposed

truth of the superstition was reinforced when he was arrested the very next day and charged with

high treason.

During the Middle Ages, people in many other parts of Europe held quite the opposite belief. They

thought black cats were the "familiars," or companions, of witches, or even witches themselves in

disguise, and that a black cat crossing your path was an indication of bad luck a sign that the devil

was watching you. This seems to have been the dominant belief held by the Pilgrims when they

came to America, perhaps explaining the strong association between black cats and witchcraft that

exists in the country to this day.

The number 13 is unlucky

Fear of the number 13, known as "triskaidekaphobia," has its origins in Norse mythology. In a

well-known tale, 12 gods were invited to dine at Valhalla, a magnificent banquet hall in Asgard, the

city of the gods. Loki, the god of strife and evil, crashed the party, raising the number of attendees

to 13. The other gods tried to kick Loki out, and in the struggle that ensued, Balder, the favorite

among them, was killed.

Scandinavian avoidance of 13-member dinner parties, and dislike of the number 13 itself, spread

south to the rest of Europe. It was reinforced in the Christian era by the story of the Last Supper, at

which Judas, the disciple who betrayed Jesus, was the thirteenth guest at the table.

Many people still shy away from the number, but there is no statistical evidence that 13 is unlucky.

21

Vocabulary exercise

1. ingrained (paragraph 1)

Some superstitions are so ingrained in modern English-speaking societies that everyone, even

scientists, succumb to them (or, at least, feel slightly uneasy about not doing so).

2. succumb to (paragraph 1)

Some superstitions are so ingrained in modern English-speaking societies that everyone, even

scientists, succumb to them (or, at least, feel slightly uneasy about not doing so).

3. a caveat (paragraph 9)

If their image appeared distorted, they were likely to die; if clear, they would live. In the first

century A.D., the Romans added a caveat to the superstition. At that time, it was believed that

people's health changed in seven year cycles.

4. disparate (paragraph 13)

Though incantations of good luck have accompanied sneezes across disparate cultures for

thousands of years (all largely tied to the belief that sneezes expelled evil spirits), our particular

custom began in the sixth century

5. rampant (paragraph 17)

In the British Isles in the Middle Ages, when fear of witchcraft was rampant, people attached

horseshoes open-end-up to the sides of their houses and doors.

6. revered (paragraph 19)

The ancient Egyptians revered all cats, black and otherwise, and it was there that the belief began

that a black cat crossing your path brings good luck.

7. ensued (paragraph 21)

The other gods tried to kick Loki out, and in the struggle that ensued, Balder, the favorite among

them, was killed.

22

Write your own sentences with the vocabulary

1. ingrained

2. succumb to

3. a caveat

4. disparate

5. rampant

6. revered

7. ensued

23

EXERCISE 3

Jordan: A spectacular country with

unfortunately too few tourists

Summary

This is a travel article written by a journalist who visited Jordan with her young daughter. She not

only talks about the places she visited whilst in the country, but also about the reasons why the

number of tourists visiting the country has drastically fallen in recent years and the consequences

this is having there.

"You are safe and sound here," the gift shop owner said, as he handed over some change. At

breakfast, the waiter had been similarly reassuring. "I always tell my guests they are in a very safe

place. There might be issues around the corner," he said, pouring out tea. "But here you are

perfectly safe."

After a while these repeated reassurances began to have the opposite than desired effect, and

actually became rather disconcerting. I hadn't expected to find Jordan anything other than

peaceful, but since the bottom has fallen out of the tourism industry because of the conflict in

neighbouring Syria, most people you meet have an urge to emphasise how risk-free a trip here is.

It's easy to see why. Thanks to the widespread sense of unease about travelling to the region,

Jordan, as well as being safe, is now extremely empty. Some of the country's most extraordinary

sites are virtually deserted; tourism has fallen 66% since 2011. As a tourist, you can't help feeling

worried for the people who depend for their livelihood on the travel industry (which has

historically contributed about 20% of GDP), but at the same time there is an uneasy pleasure in

visiting places like Petra, one of the new seven wonders of the world, in near silence.

Nothing had prepared me for how spectacular Jordan is, and perhaps part of the intense

experience of visiting now is tied up with the unusually solitary feeling you have as you walk

through its ancient sites.

After a late-night arrival in Amman with Rose, my 12-year-old daughter, we set off early and drove

through the desert to Petra, arriving late morning. When tourism here was at its peak, there were

as many as 3,000 visitors every day. On the day we visited in late October, only 300 people went

through the gates. This meant that walking in the Siq, the natural gorge that leads through red

sandstone rocks to the vast classical Treasury building, carved into the rockface in the first century

BC, felt very peaceful. There were no crowds with selfie-sticks, no umbrella-waving tour guides. It

was the most unfrazzling experience, which allowed us to look at the scenery and see it as it has

been for centuries.

Conservationists' concerns, referred to in my now out-of-date Lonely Planet Guide, about mass

tourism in Petra – the pernicious effects of humidity and the damage wrought by thousands of feet

trampling up the steps cut into the rock – are no longer so acute.

24

We had only one day in Petra, but there was so much we wanted to see that we walked 12 miles,

racing around in the heat to pack everything in, overwhelmed and stupefied by the quantity of

beautiful tombs and facades. Guidebook photographs do no justice at all to the splendour of the

site, the monumental architectural talent of the Nabateans (the nomadic people who built Petra)

and the mesmerising way sunlight changes the colour of the rock as the day progresses, from

orange to pink and, with dusk, to shadowy grey. This vast settlement is truly extraordinary. The

canyon alone and the sudden, amazing reveal of the Treasury is enough in itself to justify a visit,

but this is only the beginning.

We hurriedly climbed 700 steps up to the Monastery, a temple or tomb carved into the mountain

summit, drinking hot, sugary mint tea at the top in a cafe offering a view over the whole site. The

cafe owner appeared bemused by the reluctance of tourists to come. "It's perfectly safe here; there

are no terrorists here. But people have stopped coming," he told us.

The Foreign Office travel advice notes that there is "a high threat from terrorism" in Jordan – but

it makes the same warning about Egypt, and also Germany and France.

Jordan's defensiveness has built up over the past 15 years, as its location, sandwiched between

Syria, Iraq, Palestine, Israel and Egypt, has conspired to discourage visitors. First there was the

Intifada of 2000, then 9/11, then the war in Iraq. Then, just as things were beginning to pick up, in

2008 there was the global recession and, later, the violent aftermath of the Arab Spring,

culminating in a civil war in Syria. The key thing to remember is that the Foreign Office website

does not advise against travel to anywhere except a two-mile strip along the Syrian border (which

is far from tourist sites); it also notes that 60,820 British nationals visited Jordan in 2015 and that

most visits are trouble-free.

We had lunch at a restaurant under a canopy of trees at the centre of the site. Towards the end of

the day, we walked around the back of the site, up another 670 steps, past tombs and Bedouin

houses, to the High Place of Sacrifice – the exposed mountain plateau where the Nabateans

performed religious rituals. A long twisting trail leads to the summit. We arrived at sunset having

passed only four other tourists on the way up. The cafe near the top was closed – last year's price

list faded and flapping in the breeze and only a goat inside. Dotted everywhere were groups of

camels sitting on the ground, their legs tucked beneath them, with no customers.

There was some bitterness at the fickle nature of the global tourist market. "A bomb goes off in

Turkey and people think 'We shouldn't visit Jordan,' " a jewellery seller said. A man selling bottles

of sand with camel shapes formed from different coloured layers, said this was the worst year since

2002, mournfully displaying the blown sand vases that are no longer selling. His friend's hotel had

just closed and his business was very slow.

We walked back down at dusk, hurrying to make sure we were on flat ground before the light

disappeared completely. There was no one else in the courtyard in front of the Treasury, and we

walked silently up the Siq in the half light, watching the shadows creep up the rock, until it was

totally dark. We heard the sound of donkeys being led back to their stables, but barely saw them in

the darkness. As we reached the end of the gorge, we saw the beginnings of preparations for Petra

by Night, with candles being lit so tourists can walk along in the late evening.

We stayed at the lovely Petra Palace (doubles/twins from £57 B&B) in Wadi Musa, just a few

hundred metres from the entrance to the site, and ate in a cafe a few doors down, enjoying small

plates of hummus, kibbeh (fried lamb meatballs), baba ganoush (chargrilled aubergine), tabouleh

and stuffed vine leaves.

25

On our second day we drove for two hours down to Wadi Rum, the spectacular desert that T E

Lawrence described as "vast, echoing and godlike", with its rocks like melted wax emerging on the

skyline, their colours shifting in the light and alien shapes forming from the cavities. We hired a

guide, Abdullah, who drove us to sand dunes where we could climb the rocks for amazing views

and later we set up camp at the foot of a sandstone cliff. Abdullah made a fire and cooked meat-

and-vegetable stew and potatoes, which we ate by torchlight, and then rolled out carpets on the

sand so we could bed down in sleeping bags in the open. We woke up before dawn to watch the

sunrise over the rocks, and walked up one of the cliffs before a breakfast of sesame paste halva and

tea.

Later in the week we travelled to the Dead Sea for a night, where there were just a handful of

people floating in the salty water when we arrived at dusk, and then 30 miles north of Amman to

see Jerash, a huge Graeco-Roman settlement, with theatres, colonnades, a hippodrome, triumphal

arches, squares and mosaics depicting scenes of daily life – all well-preserved after an earthquake

in 749 buried the ruins in sand for centuries. It felt such a privilege to see this remarkable place so

empty – so unlike the jostling experience of walking through the Forum in Rome. In a time when

Peru has set a limit on the number of people walking the Inca Trail, and residents in Venice are

protesting against tourist numbers, visiting Jordan feels like being transported back to another

era, before charter flights and package holidays. When we arrived at 9.30am, there was one tour

bus in the car park. It got busier towards lunchtime, but most of the time we were alone among the

amphitheatres and plazas. We drank cardamom coffee in the Temple of Artemis, watching lizards

dart out from between the Corinthian columns, while a stray kitten tried to climb into my handbag.

Jordan clearly needs tourists to return. The big chain hotels are managing to weather the storm by

shifting marketing to locals, but the smaller businesses are suffering. "Before 2011, 70% of our

business came from Russia, Scandinavia, Germany and the UK. Now that has shifted to 70% of our

business coming from Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine and expat Iraqis," the manager of Dead Sea

Kempinski told me. "The bigger hotels can shift to weddings and the local market, but those who

are most affected are the people selling trinkets."

The Jordanian Tourism Board is fighting back in imaginative ways. It recently brought a group of

film producers and directors over from Los Angeles to show them the country's superb film

locations. It has encouraged Instagram stars to come and post picturesque scenes from the desert.

They like to remind visitors of the number of films made in Jordan, from Lawrence of Arabia to

Theeb, which won the Bafta for best foreign film last year, to The Martian and Indiana Jones and

the Last Crusade. The board is optimistic for 2017; UK visitors are already up 6% this year and the

Russian market is up 1,200%.

Jordan is home to 635,000 refugees from Syria, 80,000 of them in the Zaatari refugee camp in the

north of the country, and the World Bank has estimated that about a third of the country's nine

million population is made up of refugees – Palestinians and Iraqis as well as Syrians.

The country's attitude towards the crisis is in marked contrast to that of some other nations. "We

welcome refugees: they are our relatives," said our guide in Jerash, Talal Omar. "We have a long

history together and we speak the same language. You having a good holiday in Jordan is helping

Jordan tackle that issue. The money that tourists bring in to our country helps pay the overheads

we have from the refugees."

I'm not sure that going on holiday in Jordan can be presented as directly aiding the refugee crisis,

but certainly the reverse is true – that the absence of tourism is hugely problematic for the country.

26

Vocabulary exercise

1. disconcerting (paragraph 2)

After a while these repeated reassurances began to have the opposite than desired effect, and

actually became rather disconcerting.

2. livelihood (paragraph 3)

As a tourist, you can't help feeling worried for the people who depend for their livelihood on the

travel industry (which has historically contributed about 20% of GDP)

3. stupefied (paragraph 7)

but there was so much we wanted to see that we walked 12 miles, racing around in the heat to pack

everything in, overwhelmed and stupefied by the quantity of beautiful tombs and facades.

4. mesmerising (paragraph 7)

Guidebook photographs do no justice at all to the splendour of the site, the monumental

architectural talent of the Nabateans (the nomadic people who built Petra) and the mesmerising

way sunlight changes the colour of the rock

5. bemused (paragraph 8)

The cafe owner appeared bemused by the reluctance of tourists to come. "It's perfectly safe here;

there are no terrorists here. But people have stopped coming," he told us.

6. culminating in (paragraph 10)

Then, just as things were beginning to pick up, in 2008 there was the global recession and, later,

the violent aftermath of the Arab Spring, culminating in a civil war in Syria..

7. weather the storm (paragraph 17)

Jordan clearly needs tourists to return. The big chain hotels are managing to weather the storm

by shifting marketing to locals, but the smaller businesses are suffering.

27

Write your own sentences with the vocabulary

1. disconcerting

2. livelihood

3. stupefied

4. mesmerising

5. bemused

6. culminating in

7. weather the storm

28

EXERCISE 4

The myth of meritocracy in education

Summary

This article argues that the belief that both success in education is largely based on merit (i.e.

based on hard work and/or ability) and that it helps to make fairer society is wrong. Through

examining a number of countries, it explains how the educational system in those countries

reinforces the existing social order (benefiting those from more affluent backgrounds and men). It

ends by suggesting some things that can be done to make education fairer to all members of

society.

The idea of meritocracy has long pervaded conversations about how economic growth occurs in the

United States. The concept is grounded in the belief that our economy rewards the most talented

and innovative, regardless of gender, race, socioeconomic status, and the like. Individuals who rise

to the top are supposed to be the most capable of driving organizational and economic

performance.

More recently, however, concerns about the actual effects of meritocracies are rising. In the case of

gender, research across disciplines shows that believing an organization or its policies are merit-

based makes it easier to overlook the subconscious operation of bias. People in such organizations

assume that everything is already meritocratic, and so there is no need for self-reflection or

scrutiny of organizational processes. In fact, psychologists have found that emphasizing the value

of merit can actually lead to more bias in favor men.

Ironically, despite growing recognition of the pitfalls of meritocracy for women and minorities, the

concept has been exported to developing countries through economic policies, multilateral

development programs, and the globalization of media and curricula. In countries with deep social

divisions like India, where the number of women in the workforce dropped 11.4 percent between

1993 and 2012, the mantra of meritocracy has taken hold as a potential means to overcome these

divides and drive economic growth – especially in education.

Economist Claudia Goldin wrote in the Journal of Interdisciplinary History that when it comes to

education, historically, "Americans equate a meritocracy with equality of opportunity and an open,

forgiving, and publicly funded school system for all. To Americans, education has been the great

equalizer, and generator, of a ‘just' meritocracy." This idea also pervades economic development

and policy circles. India, a society once famous for its caste inequality and number of "missing

women," has embraced the value of meritocracy for the modern economy and now touts its success

in advancing merit over historic prejudices in education. Since 2010, the Right to Education Act

has guaranteed free schooling for all Indian children up to age 14, and by 2013, 92 percent of

children, nearly half of them girls, were enrolled in primary school, up from 79 percent in 2002.

And yet equal access to schools does not guarantee that the best and brightest will succeed. During

fieldwork in the Indian Himalayas between 2014 and 2015, we observed the poor quality of

education available to local children. Teachers were frequently absent from school, buildings

29

lacked proper sanitation, and parents often had to pay additional fees despite government

mandates. Rote memorization was a common teaching method, and many children had difficulty

answering questions that were not in the same format they learned. Studies by academics and the

United Nations Development Programme show similar problems in schools serving poor and rural

communities across India. Students at these schools do not receive the same quality of education

as their wealthy, urban peers, making it more difficult for them to succeed on merit.

Indians also hold up their exam-based university admission system as an example of meritocracy –

university acceptance is based only on exam scores. This belief in meritocracy may allow Indians to

overlook continuing disparities in acceptance rates and the underrepresentation of women in

STEM fields. To be accepted at elite Indian universities, students must score in the top percentiles

of national exams. But achieving a good exam score is not solely based on merit because of

differential access to resources. Liberalization in the education sector has created a boom in

private schools across India, as well as a thriving educational services industry. Private tutors,

after-school courses, test prep centers, and accelerated English programs abound, promising to

give children the extra edge they need to pass university entrance tests. Students from privileged

backgrounds with expensive private educations, highly educated parents, and the resources to

access test prep services consistently score higher on national exams than others.

Gender exacerbates these class differences, particularly in terms of admission to elite STEM

institutions – the Indian Institutes of Technology, or IITs. Only 8 percent of students at IITs are

women, though a much higher percentage of women study STEM subjects in high school. Fewer

women attend coaching classes in preparation for the IIT entrance exam, making them less likely

to receive sufficient admission scores. This underrepresentation seems to be due partly to the

belief, also common in the United States and elsewhere, that women are less suited to technical

jobs, and partly to parents' greater willingness to invest in a son's education. In India, sons are

expected to contribute to family income over the long-term. Daughters, on the other hand, are not

seen as long-term contributors, because they will marry into another family and are less likely to

enter the workforce. Because families do not invest as much in women's success in STEM fields,

female students are less likely to achieve the high exam scores required for IITs admission.

Believing in meritocracy has also allowed successful Indians to dismiss the continued presence of

bias. In 2006, the government announced plans to set aside additional places in federally-funded

universities for students from marginal caste groups. In response, medical students and doctors

demonstrated in cities across India, claiming that these quotas would "compromise the quality" of

health care and put patients at risk, because there would be fewer seats available to students with

the highest test scores. The demonstrators, mostly middle and upper-class people from urban

areas, also asserted that higher scores were a mark of higher intelligence. The supposedly objective

nature of admissions tests led these people to overlook how money, connections, and parental

involvement had ensured that they could do well on the entrance exam.

This story should sound familiar to readers regardless of their country of origin. Whether in the

United States or China, the mantra of meritocracy often helps divert attention from ongoing

inequalities.

In the United States, wealthier parents can also be more involved in children's education and

provide additional resources that ensure academic success. Studies by Harvard researchers have

demonstrated that SAT test questions are unconsciously biased in favor of white, middle class

students. Such inequalities have contributed to the growing educational achievement gap between

rich and poor Americans. But since success is widely believed to be the result of individual merit,

poor students are blamed for their failures.

30

While there is little gender bias in access to education in the United States, and more women than

men earn bachelor's degrees, gender bias continues at colleges in a surprising way. A smaller

percentage of female applicants are accepted to elite colleges than male applicants, because many

more qualified women apply to these schools. Universities accept a lower percentage of women to

maintain a gender ratio closer to 50-50 and since they are exempt from Title IX – the law banning

gender discrimination in the United States – these practices have gone unchallenged. Having

fewer women with elite degrees only compounds the well documented discrimination American

women continue to face in the labor market.

Like India, China relies on a national exam to determine admission to university. But rural,

migrant, and disabled children systematically receive lower-quality schooling than their urban

counterparts, resulting in lower exam scores. In fact, students from Beijing with access to better

schools are 41 times more likely to gain admission to top Chinese universities than students from

poor rural areas. Girls from rural areas are even more disadvantaged as they are less likely to

graduate from high school than boys and are consequently underrepresented in the college

population. The Chinese government has not made moves to address these issues, because the

school system is widely regarded as meritocratic, thus justifying any imbalances as the result of

differential ability and not differential access.

This is not to say that we should quit striving toward meritocracy. In its pure form, it is a worthy

ideal. But we must recognize that the idea of meritocracy has largely served to entrench the

privileges of the elite and justify their success. Claiming to be in a meritocracy is not the same as

achieving it, and policies created to improve opportunities, like exam-based admission, may not

work as expected. To move beyond the rhetoric of meritocracy to actual merit-based systems will

require significant changes to education and university admission including:

1. Improving educational access to all in order to improve the preparation for students of all

genders, races, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Governments could recruit and train

teachers from underserved communities, who will be more invested in student success, to

address imbalances in educational quality for girls and boys. This has been an important

recommendation for achieving better educational outcomes for indigenous peoples in Canada

who have been chronically under-served by the current education system. Governments

could also collaborate with local NGOs to train new teachers and improve school facilities

without dramatically increasing costs.

2. Changing admission processes to make university education more accessible to all

underrepresented groups. Admissions tests could be written by people of all genders from

many different backgrounds to ensure that one kind of life experience is not over-

represented. Alternatively, some schools are foregoing the use of entrance exams entirely in

order to engage in a more holistic assessment of university candidates. A recent study found

that high school grades are a better predictor of student success in college than standardized

test scores, and an increasing number of American universities are now "test-optional."

The advantage of exams is that they provide a score that can easily be compared across candidates.

The advantage of a holistic assessment is that it can account for multiple criteria of excellence.

Neither is a panacea for bias, which can creep in at different points. For exams, biased access to

resources or bias in the test may lead to differential test scores. For holistic assessments, the basis

of comparison is unclear and therefore prone to bias at the point of decision. Although the more

holistic admission system in the United States is also open to manipulation by elites, it can at least

31

attempt to account for the different advantages that individual applicants possess. Given the

challenges in education, acknowledging existing inequalities holds more promise for success than

believing we already know how to be meritocratic.

32

Vocabulary exercise

1. is grounded in (paragraph 1)

The concept is grounded in the belief that our economy rewards the most talented and

innovative, regardless of gender, race,

2. pitfalls of (paragraph 3)

Ironically, despite growing recognition of the pitfalls of meritocracy for women and minorities,

the concept has been exported to developing countries

3. disparities (paragraph 6)

This belief in meritocracy may allow Indians to overlook continuing disparities in acceptance

rates and the underrepresentation of women in STEM fields.

4. abound (paragraph 6)

Private tutors, after-school courses, test prep centers, and accelerated English programs abound,

promising to give children the extra edge they need to pass university entrance tests.

5. compounds (paragraph 11)

Having fewer women with elite degrees only compounds the well documented discrimination

American women continue to face in the labor market.

6. entrench (paragraph 13)

This is not to say that we should quit striving toward meritocracy. In its pure form, it is a worthy

ideal. But we must recognize that the idea of meritocracy has largely served to entrench the

privileges of the elite and justify their success.

7. are foregoing (paragraph 15)

Alternatively, some schools are foregoing the use of entrance exams entirely in order to engage

in a more holistic assessment of university candidates.

33

Write your own sentences with the vocabulary

1. is grounded in

2. pitfalls of

3. disparities

4. abound

5. compounds

6. entrench

7. are foregoing

34

EXERCISE 5

The comparative failure of online grocery

shopping

Summary

This article talks about the reasons why unlike other products (e.g. clothes, books, electronics

etc...), buying food/groceries online has not taken off in the United States. It explains the factors

which have caused this and what companies are now doing in order to get more consumers to do

their weekly food shopping online rather than in person in a supermarket.

Nearly 30 years ago, when just 15 percent of Americans had a computer, and even fewer had

internet access, Thomas Parkinson set up a rack of modems on a wine rack and started accepting

orders for the internet's first grocery delivery company, Peapod, which he founded with his brother

Andrew.

Back then, ordering groceries online was complicated – most customers through slow dial-up

modems, and Peapod's web graphics were so rudimentary customers couldn't see images of what

they were buying. Delivery was complicated, too: The Parkinsons drove to grocery stores in the

Chicago area, bought what customers had ordered, and then delivered the goods from the backseat

of their beat-up Honda Civic. When people wanted to stock up on certain goods – strawberry

yogurt or bottles of Diet Coke – the Parkinsons would deplete the stocks of the requested items in

local grocery stores.

Peapod is still around today. But convincing customers to order groceries online is still nearly as

difficult now as it was in 1989. Whilst twenty-two percent of apparel sales and 30 percent of

computer and electronics sales happen online today, only 3 percent of grocery sales are, according

to a report from Deutsche Bank Securities. "My dream was for it to be ubiquitous, but getting that

first order can be a bit of a hurdle," Parkinson told me from Peapod's headquarters in downtown

Chicago. (He is now Peapod's Chief Technology Officer; his brother has since left the company.)

Until online grocery-delivery companies are delivering to hundreds of homes in the same

neighborhood, it will be very hard for them to make a profit. Though it is an $800 billion business,

grocery is famously low-margin; most grocery stores are barely profitable as it is. Add on the labor,

equipment, and gas costs of bringing food to people's doors quickly and cheaply, and you have a

business that seems all but guaranteed to fail. "No one has made any great amount of money

selling groceries online," Sucharita Kodali, an analyst with Forrester Research, told me. "In fact,

there have been a lot more people losing money."

This is not true in every country. In South Korea, 20 percent of consumers buy groceries online,

and both in the United Kingdom and Japan, 7.5 percent of consumers do, according to Kantar

Consulting. But those are countries with just a few large population centers, which makes it easier

for delivery companies to set up shop in just a few big cities and access a huge amount of

purchasing power. In the United States, by contrast, people are spread out around rural, urban,

35

and suburban areas, making it hard to reach a majority of shoppers from just a few physical

locations. In South Korea and Japan, customers are also more comfortable with shopping on their

phones than consumers are in countries like the United States.

Still, companies are still trying to make online grocery delivery work in the United States. Today,

Peapod is one of dozens of companies offering grocery delivery to customers in certain metro

areas. In June 2017, Amazon bought Whole Foods for $13.4 billion and started rolling out grocery

delivery for its Prime members in a number of cities across the country; analysts predicted at the

time that the company's logistics know-how would allow it to leverage Whole Foods stores to

dominate grocery delivery. Also in 2017, Walmart acquired Parcel, a same-day, last-mile delivery

company. Two months after that, Target said it was buying Shipt, a same-day delivery service.

Kroger announced last May it was partnering with Ocado, a British online grocer, to speed up

delivery with robotically operated warehouses. Companies like ALDI, Food Lion, and Publix have

started working with Instacart to deliver groceries from their stores. FreshDirect recently opened a

highly automated 400,000-square-foot delivery center and says it plans to expand to regions

beyond New York, New Jersey, and Washington D.C. in the coming year.

The story of Peapod, which has had 30 years to perfect the art of online grocery delivery, suggests

that making money will be a challenge for even deep-pocketed retailers like Amazon. Peapod has

more experience than any other online grocery delivery company. It outlasted Webvan, which

raised $800 million before crashing in 2001, and beat out other big bets of the dot-com boom such

as Kozmo, Home Grocer, and ShopLink.