Preview text:

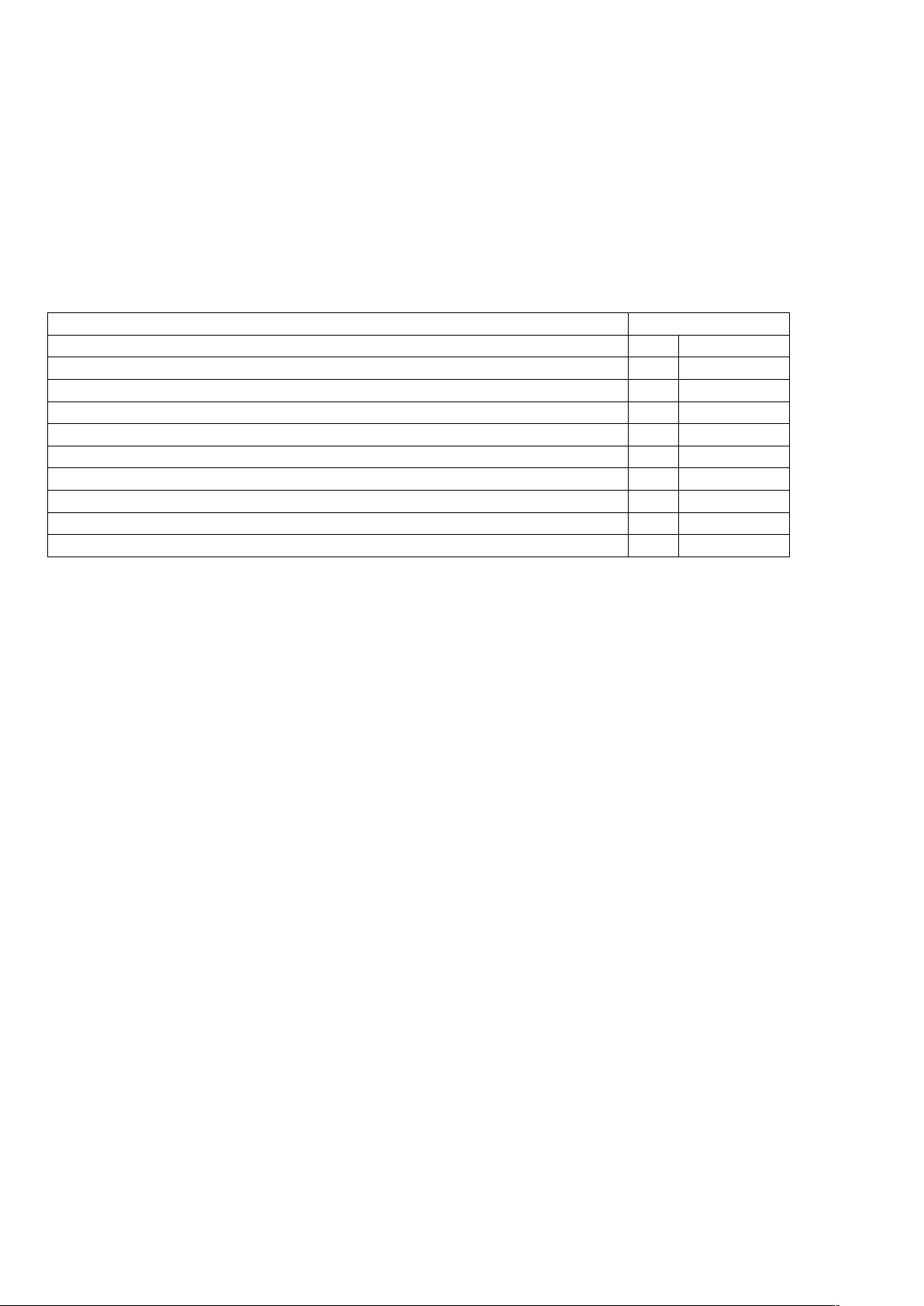

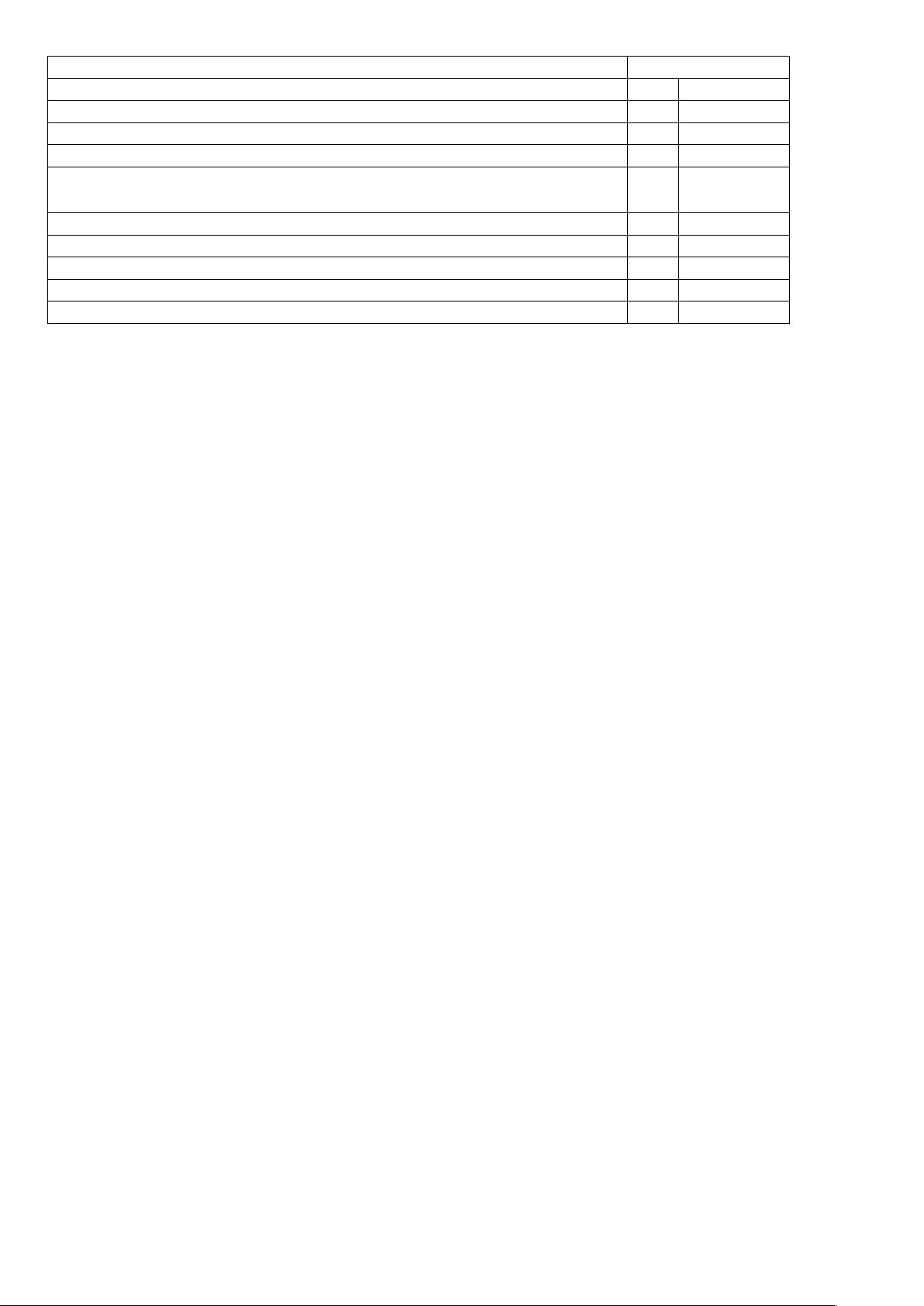

III. READING (50 POINTS)

Part 1. For questions 46-55, fill each of the following numbered blanks with ONE suitable word and

write your answers in the corresponding numbered boxes provided.

One of the strongest influences on teenagers today is that of their peers. What their friends think, how they

dress and how they act in class and out of it (46)_______ the behaviour of nearly every teenager. In their

(47)_______ not to be different, some children go so (48)_______ as to hide their intelligence and ability in

case they are made fun of. Generally, teenagers do not want to stand out from the (49)_______. They want

to fit in, to be accepted. In psychological terms the importance of peer pressure can not be overemphasized.

There is a lot of evidence that it has great (50)_______ on all aspects of their lives, from the clothes they

wear, the music they listen to and their (51)_______ to studies, to their ambitions in life, their relationships

and their (52)_______ of self-worth. However, as adolescents grow up into young adults, individuality

becomes more acceptable and in their (53)_______ for their personal style, the teenager and young adult

will begin to experiment and be more willing to (54)_______ the risk of rejection by the group. Concern

about intellectual ability and achieving good exam results can dominate as the atmosphere of competition

develops and worries about the future (55)_______ any fears of appearing too brainy.

Part 2. For questions 56-68, read the following passage and do the tasks that follow. THINK HAPPY

It’s no joke: even scientists at the Royal Society are now taking the search for the source of happiness very seriously.

A. What would Sir Isaac Newton have made of it? There he was, painted in oils, gazing down at one of the

strangest meetings that the Royal Society, Britain’s most august scientific body, has ever held. If Newton

had flashed a huge grin, it would have been completely appropriate, for beneath him last week a two- day

conference was unfolding on a booming new field of science: investigating what makes people happy.

Distinguished professors strode up to the podium, including one eminent neurologist armed with videos of

women giggling at comedy films; another was a social scientist brandishing statistics on national

cheerfulness. Hundreds of other researchers sat scribbling notes on how to produce more smiles.

B. The decision by the Royal Society to pick ‘the science of wellbeing’ from hundreds of applications for

conferences on other topics is no laughing matter. It means that the investigation of what makes people

happy is being taken very seriously indeed. ‘Many philosophies and religions have studied this subject, but

scientifically it has been ignored,’ said Dr Nick Baylis, a Cambridge University psychologist and one of the

conference organisers. ‘For the Royal Society to give us its countenance is vital, because that states that

what we are doing deserves to be acknowledged and Investigated by the best scientific minds.’

C. At first sight, the mission of Baylis – and the growing number of other scientists working on happiness

research – appears fanciful. They want to deploy scientifically rigorous methods to determine why some

people are lastingly happy while others tend to misery. Then they envisage spreading the secret of happiness

across the globe and, in short, increasing the sum of human happiness. ‘If someone is happy, they are more

popular and also healthier, they live longer and are more productive at work. So it is very much worth having’ he says.

D. Baylis, the only ‘positive psychology’ lecturer in Britain, knows that the aims of happiness research

might sound woolly, so he is at pains to distance himself from the brigades of non- academic self-help gurus.

He refers to ‘life satisfaction’ and ‘wellbeing’ and emphasises that his work, and that of others at the

conference, is grounded in solid research. So what have the scientists discovered – has a theory of happiness been defined yet?

E. According to Professor Martin Sellgman, probably the world’s leading figure in this field, happiness

could be but a train ride – and a couple of questionnaires – away. It was Seligman, a psychologist from

Pennsylvania University, who kick-started the happiness science movement with a speech he made as

President of the American Psychological Association (APA). Why, asked Seligman, shocking delegates at

an APA conference, does science only investigate suffering? Why not look into what steps increase

happiness, even for those who are not depressed, rather than simply seek to assuage pain? For a less well-

known scientist, the speech could have spelt the end of a career, but instead Seligman landedfunding of

almost £18m to follow his hunch. He has been in regular contact with hundreds of other researchers and

practising psychologists around the world, all the while conducting polls and devising strategies for increasing happiness.

F. His findings have led him to believe that there are three main types of happiness. First, there is ‘the

pleasant life’ – the kind of happiness we usually gain from sensual pleasures such as eating and drinking or

watching a good film. Seligman blames Hollywood and the advertising industry for encouraging the rest of

us, wrongly as he sees it, to believe that lasting happiness is to be found that way. Second, ị there is ‘the

good life’, which comes from enjoying something we are good or talented at. The key to this, Seligman

believes, lies in identifying our strengths and then taking part in an activity that uses them. Third, there is

‘the meaningful life’. The most lasting happiness, Seligman says, comes from finding something you believe

in and then putting your strengths at its service. People who are good at communicating with others might

thus find long-lasting happiness through becoming involved in politics or voluntary work, while a rock star

wanting to save the world might find it in organising a charity concert.

G. Achieving ‘the good life’ and ‘the meaningful life’ is the secret of lasting happiness, Seligman says. For

anybody unsure of how to proceed, he has an intriguing idea. To embark on the road to happiness, he

suggests that you need a pen, some paper and, depending on your location, a railway ticket. First, identify a

person to whom you feel a deep debt of gratitude but have never thanked properly. Next, write a 300-word

essay outlining how important the help was and how much you appreciate it. Then tell them you need to

visit, without saying what for, turn up at their house and read them the essay. The result: tears, hugs and

deeper, longer-lasting happiness, apparently, than would come from any amount of champagne.

H. Sceptics may insist that science will always remain a clumsy way of investigating and propagating

happiness and say that such things are better handled by artists, writers and musicians – if they can be

handled at all. And not everybody at the conference was positive about the emerging science. Lewis

Wolpert, professor of biology as applied to medicine at University College London, who has written a

bestseller about his battle with depression, said: ‘If you were really totally happy, I’d be very suspicious. I

think you wouldn’t do anything, you’d just sort of sit there in a treacle of happiness. There’s a whole world

out there, and unless you have a bit of discomfort, you’ll never actually do anything.’

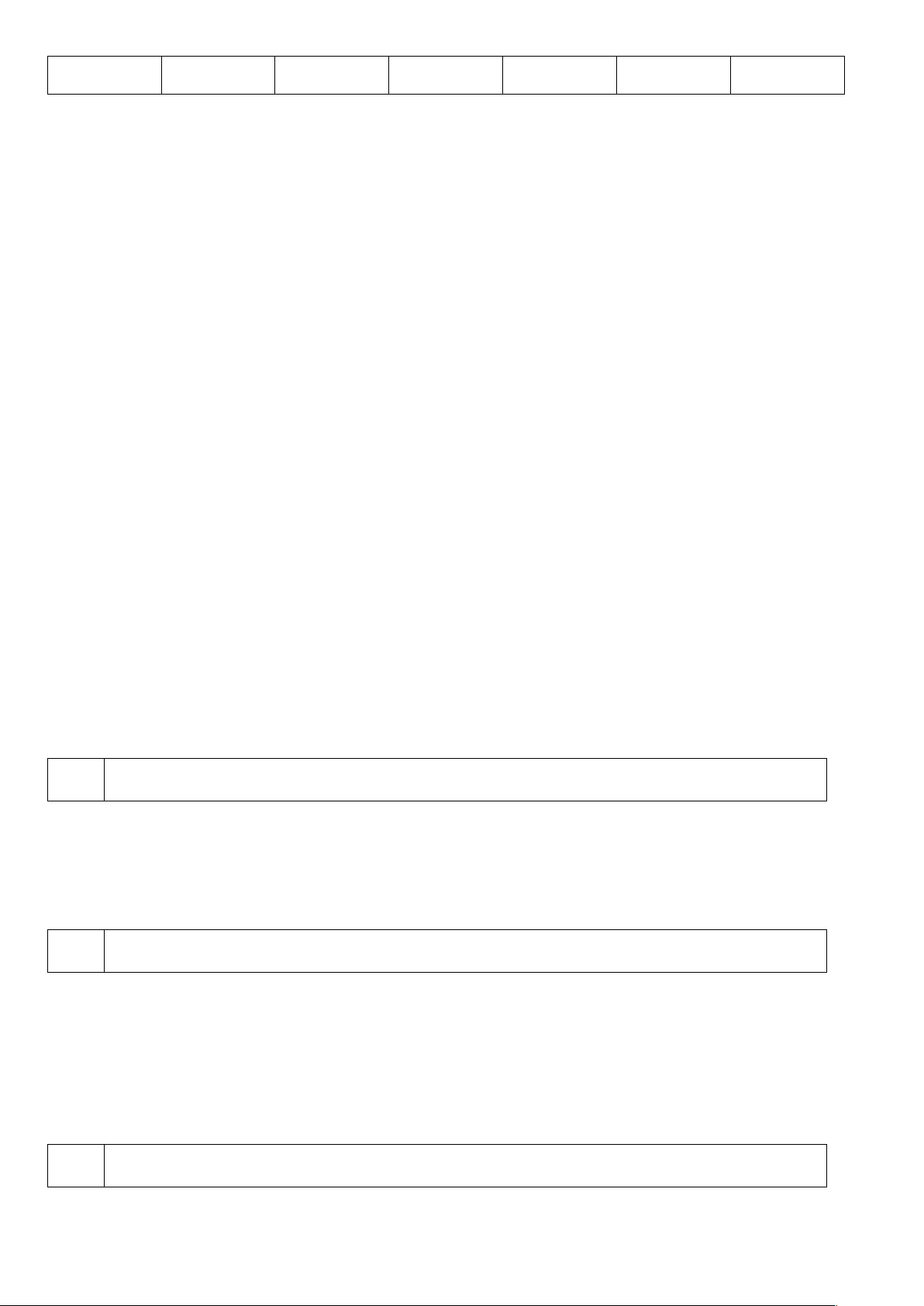

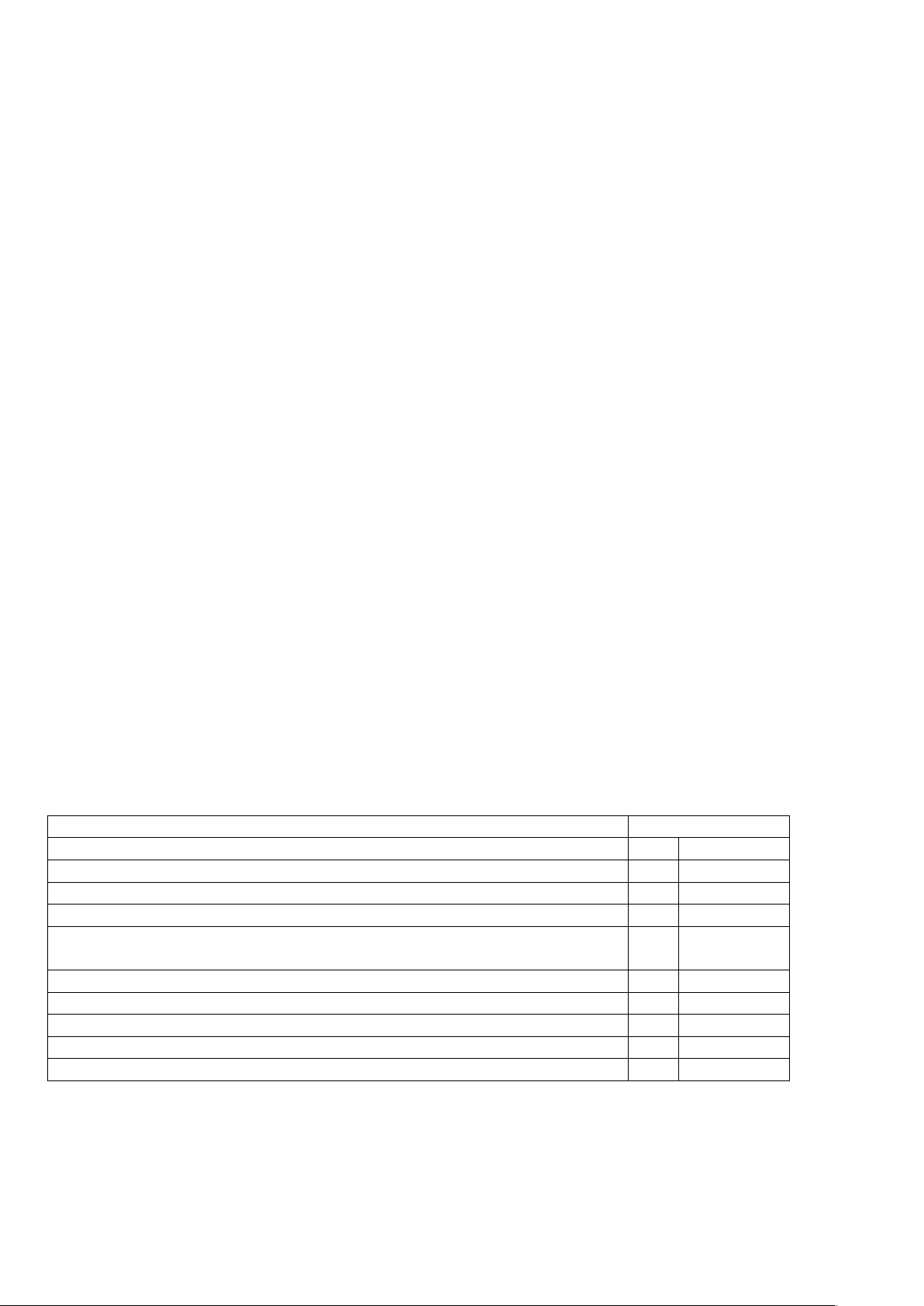

Questions 56-59: There are eight paragraphs marked A-H in the passage. In which paragraph is the

following mentioned? Write your answers in the corresponding numbered box provided.

56. a view that complete happiness may not be a desirable goal

57. a reference to the potential wider outcomes of conducting research into happiness

58. an implication of the fact that the conference was held at all

59. a statement concerning the possible outcome of expressing a certain view in public

Questions 60-62: Complete the sentences below with words taken from the passage. Use NO MORE

THAN THREE WORDS for each answer. Write your answers in the corresponding numbered box provided.

60. At the conference, research into happiness was referred to as the _______.

61. Baylis and others intend to use _______ to find out what makes people happy or unhappy.

62. Baylis says he should not be categorised among the _______ who do not have academic credentials.

Questions 63-68: Complete the sentences below using words from the box. Write your answers in the

corresponding numbered box provided.

Seligman’s categories of happiness Seligman’s first type of happiness involves the enjoyment of pleasures

such as (63)_______. He believes that people should not be under the (64)_______ that such things lead to

happiness that is not just temporary. His second type is related to (65)_______. Identification of this should

lead to (66)_______ and the result is ‘the good life’. His third type involves having a strong (67)_______

and doing something about it for the benefit of others. This, according to

Seligman, leads to happiness that has some (68)_______. confidence entertainment incentive leadership thrill perseverance illusion effort ability theory celebration participation ego permanence leadership encouragement exaggeration concept conviction support

Part 3. In the passage below, seven paragraphs have been removed. For questions 69-75, read the

passage and choose from the paragraphs A-H the one which fits each gap. There is ONE extra

paragraph which you do not need to use. Write your answers in the corresponding numbered box provided.

STEP THIS WAY FOR AN ALTERNATIVE ECONOMY

I remember the day I met an idealistic pilgrim

Mark Boyle, or Saoirse as he preferred to be called, had set out to walk 12,000 kilometres from his home in

the UK to Gandhi’s birthplace in India. His mission was to prove that his dream of living in a money-free

community really did have legs. I met him in Brighton soon after the start of his epic journey. Obviously, I’d

no sooner caught sight of him approaching than I’d started peering downwards, because he’s obligingly

stuck out a sandal-clad foot to give me a closer look. The “boys”, as he called them on his blog, had become famous in their own right. 69.

There was indeed plenty more in the world to worry about yet something about this man – his gentleness, his

over-active conscience, his poor feet – brought out all my maternal instincts. Saoirse, then twenty-eight, still

had another two and a half years of walking ahead of him, carrying no money and very few possessions

along a hair-raising route through Europe and central Asia, to his ultimate destination in India. 70.

It had all begun, it transpired, when Saoirse (Gaelic for "freedom" and pronounced "sear-shuh") was

studying business and economics at Galway University. "One day I watched the film Gandhi, and it just

changed the whole course of my life. I took the next day off lectures to start reading about him, and after

that I just couldn't read enough, it made me see the whole world in a different way." 71.

The idea behind the website grew out of that seemingly simple proposition. You signed up and listed all the

available skills and abilities and tools you had, and donated them to others. In return you might make use of

other people's skills. For example, people borrow power tools, have haircuts or get help with their vegetable plots. 72.

I asked anxiously about his planning for the journey, and he said that he was leaving it all in the hands of

fate. So far, he had been in places where his friends and fellow Freeconomists could help him, so mainly he

had had arrangements for places to sleep and eat. Otherwise, he had tried to talk to people, to explain what

he was doing and hope that they would give him a hand. His T-shirt said, in big letters, "Community Pilgrim". 73.

His itinerary was certainly challenging - and he did not even have a single visa lined up. "They don't give

visas more than about three months in advance in a lot of countries," he said, "so I thought I would just go

for it." But I had my doubts whether some of the countries involved would let a westerner - even a gentle

hippy such as Saoirse – just stroll in. 74.

Once I had suppressed my concerns for his welfare, I found myself thinking that, actually, it is only our

cynical, secular age that finds the notion of a pilgrimage odd. The idea of spiritual voyages seems to be built

into every religion and, for most believers, Saoirse's faith - that he would be looked after, that everything

would turn out OK, that what he was doing was a good thing to do for humanity – would not be odd at all.

Most cultures accept the idea of a good person, a saint or a prophet. 75.

After nearly an hour's talking, Saoirse was starting to look tired: but made one final attempt to explain.

"Look, if I've got £100 in the bank and somebody in India dies because they needed some money, then, in a

way, the responsibility of that person's death is on me. That's very extreme, I know, but I've got more than I

need and that person needed it. And if you know that, then you've either got to do something about it, or you

have to wake up every morning and look at yourself in the mirror." His eyes were now red-rimmed, I think

with emotion and exhaustion. We said our goodbyes. And I could not help noticing that he was limping. Those poor, poor feet. The missing paragraphs:

A. After two weeks of solid walking from his starting point in Bristol at a rate of around 25 miles a day, his

discomfort was readily apparent, despite the sensible footwear. "It's all right," he said. "I've got blisters, but

bombs are falling in some places."

B. For Saoirse, both pilgrimage and this enterprise were only the first steps. His long-term vision was to

nurture a money-free community where people would live and work and care for each other. Perhaps that

was why when I met him that day, he struck me as an idealist who was going to come unstuck somewhere along the way.

C. Was there a back-up plan if any failed to materialise ? He said he didn’t really have one because that

would be "contrary to the spirit of the thing". Was he prepared to be lonely, scared, threatened? He said he

had spent the previous few months trying to work through the fear, but that he "just had to do it".

D. His mentor’s exhoration to "be the change you want to see in the world" had particular meaning for him.

Then, a few years later, he was sitting with a couple of friends talking about world problems - sweatshops,

war and famine etc – when it struck him that the root of those things was the fear and insecurity and greed

that manifests itself in our quest for money. He wondered what would happen if you just got rid of it?"

E. Indeed, his faith in human kindness, rather worryingly, seemed to know no bounds. I convinced myself,

however, that ordinary folk he’d meet along the way would mostly see that he was sincere, if a little

eccentric, and would respond to that.

F. I wondered if his mother at least shared some of these anxieties. All I learnt though was that she was,

like his father, thoroughly supportive and was following his progress keenly through the website.

G. Pehaps it is, in fact, only in the contemporary western world, the world of the selfish gene, that extreme

altruism is, according to Richard Dawkins at least, "a misfiring”. Because from all I ‘d heard, there it was

before me on a pavement in Brighton. I felt I still hadn’t got to the bottom of what drove Saoirse on, however.

H. He was undertaking that extraordinary pilgrimage to promote the idea of "freeconomy", a web-based

money-free community. What’s more, he’d be relying just on the kindness and generosity of strangers and

contacts that he’d made through the site. I pressed him for deeper reasons.

Part 4. For questions 76-85, read an extract from an article on anthropology and choose the answer A,

B, C or D that fits best according to the text. Write your answers in the corrresponding numbered boxes provided.

1) Anthropology distinguishes itself from the other social sciences by its greater emphasis on fieldwork as

the source of new knowledge. The aim of such studies is to develop as intimate an understanding as possible

of the phenomena investigated. Although the length of field studies varies from a few weeks to years, it is

generally agreed that anthropologists should stay in the field long enough for their presence to be considered

‘natural’ by the permanent residents.

2) Realistically, however, anthropologists may never reach this status. Their foreign mannerisms make them

appear clownish, and so they are treated with curiosity and amusement. If they speak the local language at

all, they do so with a strange accent and flawed grammar. They ask tactless questions and inadvertently

break rules regarding how things are usually done. Arguably this could be an interesting starting point for

research, though it is rarely exploited. Otherwise, anthropologists take on the role of the ‘superior expert’, in

which case they are treated with deference and respect, only coming into contact with the most high-ranking

members of the society. Anthropologists with this role may never witness the gamut of practices which take

place in all levels of the society.

3) No matter which role one takes on, anthropologists generally find fieldwork extremely demanding.

Anthropological texts may read like an exciting journey of exploration, but rarely is this so. Long periods of

time spent in the field are generally characterised by boredom, illness and frustration. Anthropologists in the

field encounter unfamiliar climates, strange food and low standards of hygiene. It is often particularly trying

for researchers with middle-class, European backgrounds to adapt to societies where being alone is

considered pitiful. It takes a dedicated individual to conduct research which is not in some way influenced by these personal discomforts.

4) Nonetheless, fieldwork requires the researcher to spend as much time as possible in local life. A range of

research methodologies can be utilised to extract information. (1) These can be classified as emic or etic. (2)

While emic descriptions are considered more desirable nowadays, they are difficult to attain, even if the

researcher does his utmost to reproduce the facts from the natives’ point of view. (3) More often than not,

aspects of the researcher’s own culture, perspective and literary style seep into the narrative. Moreover,

research generally involves translations from one language to another and from speech into writing. In doing

this, the meaning of utterances is changed. (4) The only truly emic descriptions can be those given by the

natives themselves in their own vernacular.

5) The least invasive type of research methodology is observation. Here, the researcher studies the group and

records findings without intruding too much on their privacy. This is not to say, however, that the presence

of the researcher will have minimal impact on the findings. An example was Richard Borshay Lee, who, in

studying local groups in the Kalahari refused to provide the people with food so as not to taint his research,

leading to an inevitable hostility towards the researcher which would not otherwise have been present.

6) A variant on the observation technique, participant observation requires that the anthropologist not only

observes the culture, but participates in it too. It allows for deeper immersion into the culture studied, hence

a deeper understanding of it. By developing a deeper rapport with the people of the culture, it is hoped they

will open up and divulge more about their culture and way of life than can simply be observed. Participant

observation is still an imperfect methodology, however, since populations may adjust their behavior around

the researcher, knowing that they are the subject of research.

7) The participatory approach was conceived in an attempt to produce as emic a perspective as possible. The

process involves not just the gathering of information from local people, but involves them in the

interpretation of the findings. That is, rather than the researcher getting actively involved in the processes

within the local community, the process is turned on its head. The local community is actively involved in the research process.

76. The main premise of the text is :

A. the steps to be followed when undertaking anthropological fieldwork.

B. a history of anthropological fieldwork methodology.

C. the effects that an anthropological fieldwork has on local communities.

D. the problems with conducting anthropological fieldwork.

77. The main reason for anthropological researchers remaining in a community for an extended period of time is that:

A. they can gather as much information as possible.

B. they can try out a range of different research methodologies.

C. they want local people to behave naturally around them.

D. they need time to become accustomed to the conditions.

78. What does the passage say about researchers who are considered a ‘clown’ by locals?

A. They do culturally unacceptable things without realising it.

B. They do not gain respect among high-ranking members of the community.

C. They cannot conduct any research of value.

D. They do not study the language and culture of the region before their arrival.

79. What does ‘gamut’ mean? A. idea or impression B. prohibition or taboo C. range or extent D. secret or mystery

80. The writer believes that the most difficult aspect of fieldwork for educated westerners is A. the lack of companionship. B. poor sanitary conditions.

C. failure to meet expectations. D. never being left alone.

81. In paragraph 3, it is implied that:

A. the fieldworker’s emotions and mood prejudice the research.

B. the longer a researcher spends in the field, the more depressed he gets.

C. middle-class Europeans find field research more difficult than researchers from other backgrounds.

D. anthropological texts tend to exaggerate the difficult conditions that researchers experience.

82. Where in paragraph 4 does this sentence belong?

A native’s point of view of his own lifestyle is emic, while the analytical perspective of the outsider is etic. A. (1) B. (2) C. (3) D. (4)

83. Why is the example of Richard Borshay Lee given in paragraph 5?

A. to demonstrate that observation is an ineffective method of gathering data.

B. to highlight why it is important that researchers minimize their impact on a community.

C. to show the dangers of researchers trying to lessen their impact on a community

D. to show how a researcher’s choice of methodology can influence the validity of his findings.

84. How does participant observation differ vary from straightforward observation?

A. It requires the researcher to become actively involved in the daily lives of those being studied.

B. It allows the subjects of the research a greater degree of privacy.

C. It eradicates the problem of research subjects altering their behaviour towards researchers.

D. It takes longer to perform this type of research effectively.

85. Which of the following is NOT true of the participatory approach?

A. It attempts to reduce etic accounts of a culture to a minimum.

B. It does not require a researcher to be present.

C. It aims to involve the subjects in both information gathering and analysis.

D. It is the reverse of the participant observation technique.

Part 5. The passage below consists of four paragraphs marked A, B, C and D. For questions 86-95, read

the passage and do the task that follows. Write your answers in the corrresponding numbered boxes provided.

CHEER UP: LIFE ONLY GETS BETTER

Human’s capacity for solving problems has been improving out lot for 10,000 years, says Matt Ridley

A The human race has expanded in 10,000 years from less than 10 million people to around 7 billion. Some

live in even worse conditions than those in the Stone Age. But the vast majority are much better fed and

sheltered, and much more likely to live to old age than their ancestors have ever been. It is likely that by

2110 humanity will be much better off than it is today and so will the ecology of our planet. This view,

which I shall call rational optimism, may not be fashionable but it is compelling. This belief holds that the

world will pull out of its economic and ecological crises because of the way that markets i goods, services

and ideas allow human beings to exchange and specialise for the betterment of all. But a constant drumbeat

of pessimism usually drowns out this sort of talk. Indeed, if you dare to say the world is going to go on being

better, you are considered embarassingly mad.

B Let me make a square concession at the start: the pessimists are right when they say that if the world

continues as it is, it will end in disaster. If agriculture continues to depend on irrigation and water stocks are

depleted, then starvation will ensue. Notice the word “if”. The world will not continue as it is. It is my

proposition that the human race has become a collective problem – solving machine which solves problems

by changing its ways. It does so through invention driven often by the marker: scarcity drives up price and

that in turn encourages the development of alternatives and efficiencies. History confirms this. When whales

grew scarce, for example, petroleum was used instead as a source of oil. The pessimists’ mistake is

extrapolating: in other words, assuming that the future is just a bigger version of the past. In 1943 IBM’s

founder Thomas Watson said there was a world market for just five computers – his remarks were true

enough at the time, when computers weighed a ton and cost a fortune.

C Many of today’s extreme environmentalists insist that the world has reached a ‘turning point’ – quite

unaware that their predecessors have been making the same claim for 200 years. They also maintain the only

sustainable solution is to retreat – to halt economic growth and enter progressive economic recession. This

means not just that increasing your company’s sales would be a crime, but that the failure to shrink them

would be too. But all this takes no account of the magical thing called the collective human brain. There was

a time in human history when big-brained people began to exchange things with each other, to become

better off as a resut. Making and using tools saved time – and the state of being ‘better off’ is, at the end of

the day, simply time saved. Forget dollars of gold. The true measure of something’s worth is indeed the

hours it takes to acquire it. The more humans diversified as consumers and specified as producers, and the

more they exchanged goods and services, the better off they became. And the good news is there is no

inevitable end to this process.

D I am aware that an enormous bubble of debt has burst around the world, with all that entails. But is this

the end of growth? Hardly. So long as somebody allocates sufficient capital to innovation, then the credit

crunch will not prevent the relentless upward march of human living standards. Even the Great Depression

of the 1930s, although an appalling hardship for many, was just a dip in the slope of economic progress. All

sorts of new products and industries were born during the depression: by 1937, 40% of Dupont’s sales came

from products that had barely existed before 1929, such as enamels and cellulose film. Growth will resume –

unless it is stifled by the wrong policies. Somebody, somewhere, is still tweaking a piece of software, testing

a new material, of transferring a gene that will enable new varieties of rice to be grown in African soils. The

latter means some Africans will soon be growing and and selling more food, so they will have more money

to spend. Some of them may then buy mobile phones from a western company. As a consequence of higher

sales, an employee of that western company may get a pay rise, which she may spend on a pair of jeans

made from cotton woven in an African factory. And so on. Forget wars, famines and poems, This is

history’s greatest theme: the metastasis of exchange and specialisation.

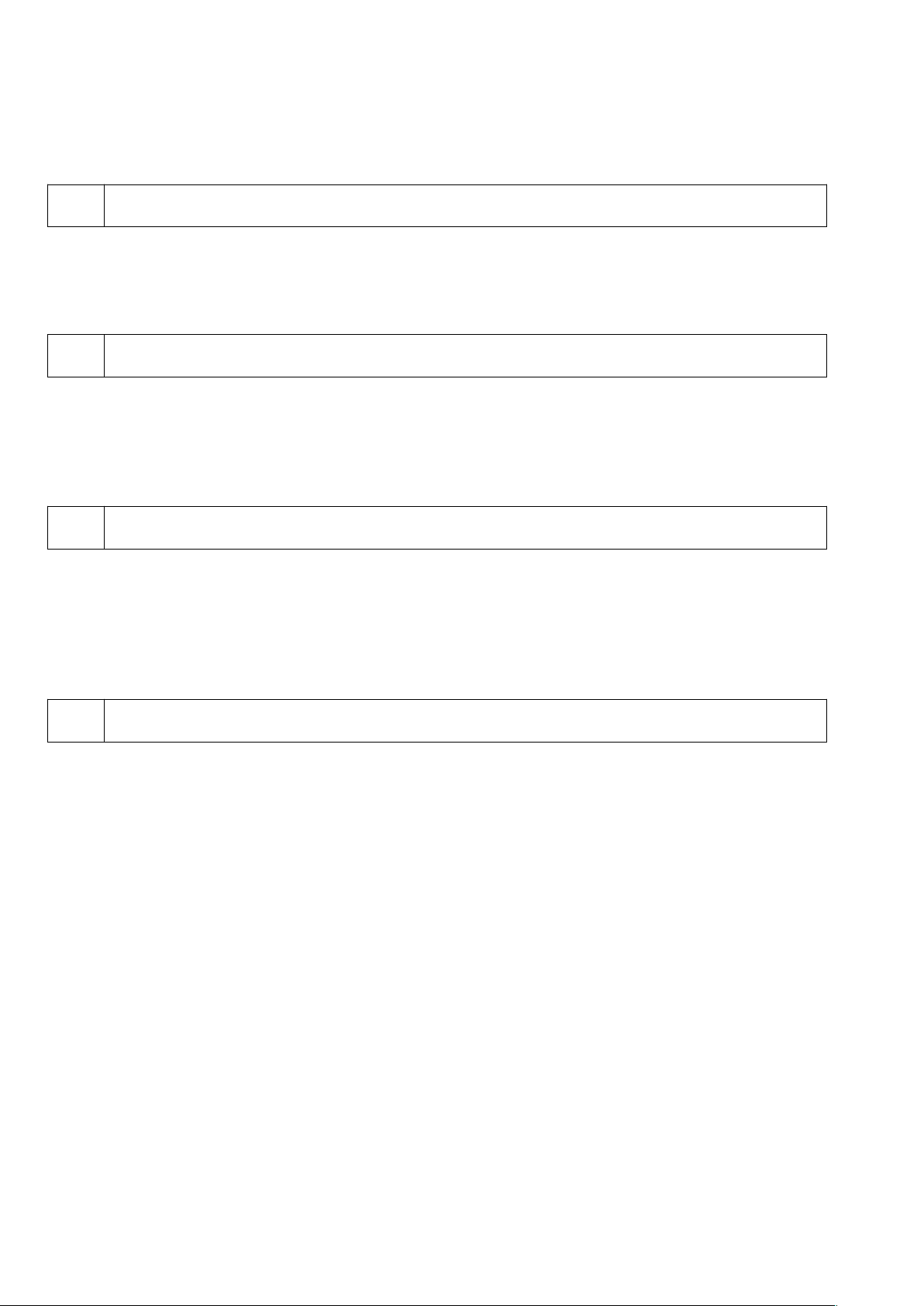

In which section does the writer Your answers:

exemplify how short-term gloom tends to lift? 86.

mention a doom-laden prophecy that is obvious? 87.

express his hope that progress is not hindered by abominable decisions? 88.

acknowledge trying to find common ground with his potential adversaries? 89.

identify unequivocally how money needs to be invested? 90.

suggest that his views are considered controversial? 91.

indicate an absurd scenario resulting from an opposing view to his own? 92.

mention the deplorable consequences of taking a positive stance? 93.

define prosperity in life in an original approach? 94.

give an example of well-intentioned ongoing research? 95. III. READING (50 POINTS)

Part 1. For questions 46-55, fill each of the following numbered blanks with ONE suitable word and

write your answers in the corresponding numbered boxes provided.

Few inventions have had more scorn and praise (46)________ upon them at the same time than television.

And few have done so much to unite the world (47)________ one vast audience for news, sport, information

and entertainment. Television must be rated (48)________ printing as one of the most significant inventions

of all time in the field of communications. In just a few decades it has (49)________ virtually every home in

the developed world and an ever-increasing proportion of homes in developing countries. It took over half a

century from the first suggestion that television might be (50)________ before the first flickering

(51)_______ were produced in laboratories in Britain and America. In 1926 John Logie Baird’s genius for

publicity brought television to the (52)________ of a British audience. It has since reached such

(53)________ of success and (54)________ on such a pivotal function that it is difficult to imagine a world

(55)________ of this groundbreaking invention.

Part 2. For questions 56-68, read the following passage and do the tasks that follow. READING WARS

A. In many developed countries literacy skirts are under siege. This is true even in societies where access

to primary education is universal and governments invest heavily in education. New Zealand, for example,

was leading the world in literacy rates in 1970, but tumbled to thirteenth place in 2001 and then again to

twenty-fourth just a few years tater. Test scores in the USA also slumped ten percent during the 1990s

despite the country riding an economic boom for much of the decade. In some cases these statistics reverse

trends that were in motion for over a century and a half. The steady, gradual expansion of literacy across

social groups and classes was one of the greatest successes of the period of industrialization that began in the mid-1850s.

B. This reversal of fortunes has lead to widespread contention over the pedagogy of teaching literacy.

What was once a dry and technical affair—the esoteric business of linguists and policy analysts—rapidly

escalated into a series of skirmishes that were played out in high-visibility forums: Newspapers ran special

features, columns and letters-to-the-editor on the literacy crisis; politicians successfully ran their national

campaigns on improving reading test scores; and parents had their say by joining Parent Teacher

Associations (PTAs) and lobby groups.

C. The arguments around reading pooled into two different classroom methodologies: constructivism and

behaviorism. The constructivist methodology grew from a holistic conception of knowledge creation that

understood reading and writing to be innate, humanistic and interpretative practices that suffered when they

were spliced and formalized within rigid doctrines, strict rules and universal skill-sets. Constructivists

associate words with meanings; each word might be thought of as a Chinese ideogram. Students are

encouraged to learn individual words and skip over and guess words they do not understand, or learn to

interpret those words by situating them within the lexical infrastructure of the sentence and the story's wider

narrative. These practices materialize as learning processes centered on guided group reading and

independent reading of high-quantity, culturally diverse literature or textual composition that emphasises

pupils conveying their own thoughts and feelings for real purposes such as letters to pen pals or journal entries.

D.Behaviorism sees the pedagogial process in a less dialectical fashion—words are initially taught not

lexically, as vehicles to convey meaning, but rather sub-lexically, as a combination of features that can be

separated and learnt in a schematic process. The behaviorist approach does not focus on words at all in the

early stages of learning. Rather, it is centered on a universally applicable method of teaching students to

isolate graphemes and phonemes with the intention that students will eventually learn to synthesize these

individual parts and make sense of spoken words textually. In this way, individual components are not

equated with the strokes of a brush on a Chinese ideogram, but rather as the focal pieces of interpretation—

as in, for example, learning to read musical notations or Morse Code. Because of its emphasis on universal

rules, behaviorism is much more conducive to formal examination and the consolidation of results across

regions and countries. The ability to master language is considered to rest in the acquisition of a set of skills

that exist independently of individuals. Classroom learning is therefore based upon the transmission of

knowledge from tutor to student, rather than seen as an internalized process that erupts within the students themselves.

E. So who comes out on top? It is not easy to say. Champions of behaviorism have claimed victory

because constructivist learning took over in the late 1980s, just before test scores on literacy began sinking

across the West. Constructivists, however, can make the valid claim that the behaviorist approach has a

heavy methodological bias towards testing and examination, and that test results do not represent the ability

of individuals to use and interpret language freely and creatively. Furthermore, different socio-economic

groups respond in different ways to each method. Those from wealthier families tend to do well regardless

of the method, but thrive on the constructivist approach implemented in the 1990s. Children from poorer

families, however, are better served by behaviorism. These outcomes have ramped up levels of socio-

economic based educational disparities in educational systems that have pushed the constructivist method.

F. It is unlikely that either constructivism or behaviorism will be permanently sidelined from curricula in

the near future. Most teachers find it easier to incorporate aspects of each approach. Constructivism may

ultimately hold the trump card because of its proven success with pupils who come from families where they

are introduced to reading and writing in various forms from a young age—this process of 'living and

learning' and immersing oneself in language is a sound principle. In a world rife with social inequities,

households with illiterate parents and a scarcity of funding for education, however, the behaviorist approach

may have the upper hand in teaching children to access the basic skills of literacy quickly and efficiently,

even if some linguistic creativity is crushed in the process.

Questions 56-62: There are six paragraphs marked A-F in the passage. In which paragraph is the

following mentioned? Write your answers in the corresponding numbered box provided.

56. A reason why constructivism might increase inequalities in society

57. Ways in which people debated the merits of different ways of teaching reading

58. A comparison between forms of communication that build meaning from isolated parts

59. Reasons why a method that is theoretically superior might not always work effectively in practice

60. An explanation of why measuring the success of different reading methods is difficult

61. An example of an activity that teachers might use to develop writing skills

62. Evidence of a national decline in reading standards Your answers 56. 57. 58. 59. 60. 61. 62.

Questions 63-65: Which THREE of the following are features of constructivism? Choose THREE letters,

A-G. Write your answers in the corresponding numbered box provided.

A.Students learn best by working on their own.

B.People are naturally inclined to develop language abilities.

C.It is vital that a disciplined and regulated approach is used.

D.It is important that students understand every word they encounter.

E.Language is best learnt as a single, organic process.

F.Everyone learns to read and write in a similar manner.

G.Context can provide helpful cues to understanding words.

Questions 66-68: Which THREE of the following are features of behaviorism? Choose THREE letters,

A-G. Write your answers in the corresponding numbered box provided.

A.The whole of a word is less important than its parts.

B.There is not a common set of conventions.

C.Students learn best by working on their own.

D.Meaning is created by connecting word fragments.

E.Linguistic capacities are built into people.

F.Students learn by receiving information from teachers.

G.It is difficult to judge how well students are doing collectively.

Part 3. In the passage below, seven paragraphs have been removed. For questions 69-75, read the

passage and choose from the paragraphs A-H the one which fits each gap. There is ONE extra

paragraph which you do not need to use. Write your answers in the corresponding numbered box provided.

MERGING ART&SCIENCE: A FALSE PREMISE

The current vogue is for believing that art and science should be brought together. This obsession for

showing that art - particularly the visual arts - is similar to science in content and the creative processes is

bemusing. I detect in it an element of social snobbery - artists are envious of scientists and scientists want to be thought of as artists. 69.

If Watson and Crick had not got the structure of DNA we know that Franklin and Klug would soon have had

it. Indeed simultaneous discovery is a common feature of science. If one could rerun the history of science

and start again it would have a different history but the end results would be the same: water would be H2O

and genes would code for proteins but the names would be different. 70.

Whatever the feelings of the scientist these are absent from the final understanding of a process. while art is

a personal creation and contains the personal views of the artist. And since science is a communal process a

scientist has to be very aware of what is known about the problem being investigated. There are strict

criteria about lack of contradiction and, of course, correspondence with reality. Science makes progress, we

build on the work of our current and earlier colleagues. To talk about progress in art makes no sense, there is change but not progress. 71.

Thus, I cannot understand what is being referred to when there is reference to critical thinking in art. In what

sense can a painting be right or wrong? Anyone can have views about a painting and engage in art

discussions. Non-scientists can thrill to scientific ideas but to make meaningful comments about them, and I

exclude their application to technology, one actually has to have detailed knowledge; science needs a much

greater, and quite different, intellectual effort. 72.

It is very rare for referees to recommend acceptance without changes. This can be a complex procedure but

in general authors are grateful for the careful reading and criticism of their paper. Even so we reject about

half of all papers we receive. Paintings, however, are neither revised nor can be shown to be wrong. 73.

The idea of creativity makes scientists want to be thought of as artists and vice versa and there may well be

something similar in all human creativity, but that it is particularly similar in scientists and artists is without

foundation. The similarity between art and science is even less than that between billiards and rugby, both of which at least use a ball. 74.

It seems just poetic licence to suggest that this picture did much to convince European scientists that the

great mystery of life might be explained in terms of electrochemical forces. (Although it may be that Jan

Vermeer did indeed discover that more compelling illusions can be achieved through a kind of optical

illusion that makes special use of the perceptual system inside our brains, rather than through the details that reach our eyes). 75.

Art does not explain, but it broadens our experience in ways that are not clearly understood. I value it in its

own terms, but it has nothing to do with understanding how the world works. To pretend that it does is to

trivialise science and do nothing for art. We should stop pretending that the two disciplines are similar, and

instead rejoice in the very different ways that they enrich our culture.. The missing paragraphs:

A. What are the criteria used by the director of a gallery and his or her advisers when selecting for

exhibition? Is he or she like the editor of a science journal? No, for there is nothing in art like the peer

review so fundamental to science; there are no art critics, just art writers. As the editor of a scientific journal,

it is extremely rare that my personal view determines whether or not a paper gets published. My role is to

choose a good editorial board and to know to whom the papers to be reviewed should be sent.

B. Bringing visual artists and scientists together merely makes them feel elevated: it is not a scientific

experience. Although it must be said that science has had a strong influence on certain artists - in the efforts

to imitate nature and thus to develop perspective or in the area of new technologies - art has contributed virtually nothing to science.

C. Then of the hundreds of thousands of papers published each year, few have a lifetime of more than a

few years. Most disappear with little if any trace. The original papers, with very rare exceptions, like those

of Einstein, are never part of scientific culture and they are not for sale. Science, unlike art, is not entertainment.

D. What intrigued me at the opening was how the exhibits were chosen. There is less of a problem with

well established artists such as Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon or Matisse. It is the very modern works that present the problem.

E. How different from this are all the arts. No Shakespeare - no Hamlet; no Picasso - no Guernica .

Moreover a work of art is capable of many interpretations and has moral content. There is but one correct

scientific explanation for any set of observations and reliable scientific understanding has no moral or

ethical content; that is to say that the scientist does not allow his own reactions to come into play.

F. The Oxford University art historian Martin Kemp takes a very different view from mine here. He claims

that during the 'Scientific Revolution' some artists were able to play an active role in the dialogue between

seeing and knowing. He gives the fiery emissions of Joseph Wright's volcanoes painted in the late eighteenth

century as an example. Wright's painting of Vesuvius erupting may be dramatic but it owes nothing to geology..

G. Art is not constrained by reality. It cannot be shown to be wrong. And of all the arts, painting is the one

least related to science as it does not deal with complex ideas or explanations, is the easiest to appreciate,

and the response is often an emotional one. Ideas in the visual arts come from art critics and historians, not the works themselves.

H. Science is about understanding how the world works, there being only one right description of any

observed phenomenon. Unlike the arts it is a collective endeavour in which the individual is ultimately

irrelevant - geniuses merely speed up discovery.

Part 4. For questions 76-85, read an extract from an article on the design of green building and choose

the answer A, B, C or D that fits best according to the text. Write your answers in the corrresponding

numbered boxes provided.

1) There has, in recent years, been an outpouring of information about the impact of buildings on the natural

environment; Information which explains and promotes green and sustainable construction design, strives to

convince others of its efficacy and warns of the dangers of ignoring the issue. Seldom do these documents

offer any advice to practitioners, such as those designing mechanical and electrical systems for a building,

on how to utilise this knowledge on a practical level.

2) While the terms green and sustainable are often considered synonymous, in that they both symbolise

nature, green does not encompass all that is meant by sustainability, which can be defined as minimizing the

negative impacts of human activities on the natural environment, in particular those which have long-term

and irreversible effects. Some elements of green design may be sustainable too, for example those which

reduce energy usage and pollution, while others, such as ensuring internal air quality, may be considered

green despite having no influence on the ecological balance.

3) Although there are a good many advocates of ‘green’ construction in the architectural industry, able to

cite ample reasons why buildings should be designed in a sustainable way, not to mention a plethora of

architectural firms with experience in green design, this is not enough to make green construction come into

being. The driving force behind whether a building is constructed with minimal environmental impact lies

with the owner of the building; that is, the person financing the project. If the owner considers green design

unimportant, or of secondary importance, then more than likely, it will not be factored into the design.

4) The commissioning process plays a key role in ensuring the owner gets the building he wants, in terms of

design, costs and risk. At the predesign stage, the owner’s objectives, criteria and the type of design

envisaged are discussed and documented. This gives a design team a solid foundation on which they can

build their ideas, and also provides a specific benchmark against which individual elements, such as costs,

design and environmental impact can be judged.

5) Owners who skip the commissioning process, or fail to take ‘green’ issues into account when doing so,

often come a cropper once their building is up and running. Materials and equipment are installed as

planned, and, at first glance, appear to fulfil their purpose adequately. However, in time, the owner realises

that operational and maintenance costs are higher than necessary, and that the occupants are dissatisfied with

the results. These factors in turn lead to higher ownership costs as well as increased environmental impact.

6) In some cases, an owner may be aware of the latest trends in sustainable building design. He may have

done research into it himself, or he may have been informed of the merits of green design through early

discussion with professionals. However, firms should not take it as read that someone commissioning a

building already has a preconceived idea of how green he intends the structure to be. Indeed, this initial

interaction between owner and firm is the ideal time for a designer to outline and promote the ways that

green design can meet the client’s objectives, thus turning a project originally not destined for green design into a potential candidate.

7) Typically, when considering whether or not to adopt a green approach, an owner will ask about additional

costs, return for investment and to what extent green design should be the limiting factor governing

decisions in the design process. (1) Many of these costs are incurred by the increased cooperation between

the various stakeholders, such as the owner, the design professionals, contractors and end-users. (2)

However, in green design, they must be involved from the outset, since green design demands interaction

between these disciplines. (3) This increased coordination clearly requires additional expenditure. (4) A

client may initially balk at these added fees, and may require further convincing of the benefits if he is to

proceed. It is up to the project team to gauge the extent to which a client wants to get involved in a green

design project and provide a commensurate service.

8) Of course, there may be financial advantage for the client in choosing a greener design. Case studies cite

examples of green/sustainable designs which have demonstrated lower costs for long-term operation,

ownership and even construction. Tax credits and rebates are usually available on a regional basis for

projects with sustainable design or low emissions, among others.

76. The writer’s main purpose is to:

A. explain to professionals how they can influence clients to choose greener designs.

B. explain the importance of green building design in reducing long-term damage to the environment

C. explain to owners commissioning a building why ignoring green issues is costly and dangerous.

D. explain to professionals why it is important to follow the correct procedures when a building is commissioned.

77. The examples of green and sustainable designs given in paragraph 2 show that:

A. designs must be sustainable in order for them to be described as green.

B. for the purposes of this paper, the terms green and sustainable have the same meaning.

C. some sustainable designs are green, while others are not.

D. some designs are termed green, even though they are not sustainable.

78. According to paragraph 3, the reason for the lack of green buildings being designed is that:

A. few firms have any experience in design and constructing buildings to a green design.

B. construction companies are unaware of the benefits of green and sustainable designs.

C. firms do not get to decide whether a building is to be constructed sustainably.

D. firms tend to convince clients that other factors are more important than sustainability.

79. In paragraph 4, what does the word ‘benchmark’ mean? A. standard B. target C. process D. comparision

80. Which of the following is NOT true about the commissioning process?

A. It is conducted before the building is designed.

B. It is a stage that all clients go through when constructing a building.

C. It is a step in the design procedure in which the client’s goals are identified.

D. It provides the firm with a measure of how well they did their job.

81. In paragraph 5, what does the phrase ‘come a cropper’ mean? A. experience misfortune B. change one’s mind C. notice the benefits D. make a selection

82. In paragraph 6, the writer implies that:

A. most clients enter the commissioning process with a clear idea of whether or not they want a green building.

B. designers are usually less concerned about green design than the clients are.

C. the commissioning process offers a perfect opportunity to bring up the subject of green design.

D. firms should avoid working with clients who reject green designs in their buildings.

83. Where in paragraph 7 does this sentence belong?

In a typical project, landscape architects and mechanical, electrical and plumbing engineers do not become

involved until a much later stage. A. (1) B. (2) C. (3) D. (4)

84. In paragraph 7, what does ‘balk at’ mean? A. display shock towards B. agree to pay C. question the reason for D. understand the need for

85. Green buildings are most likely to incur more expense than conventional buildings due to:

A. higher taxes incurred on sustainable buildings.

B. higher long-term operational costs.

C. the higher cost of green construction materials.

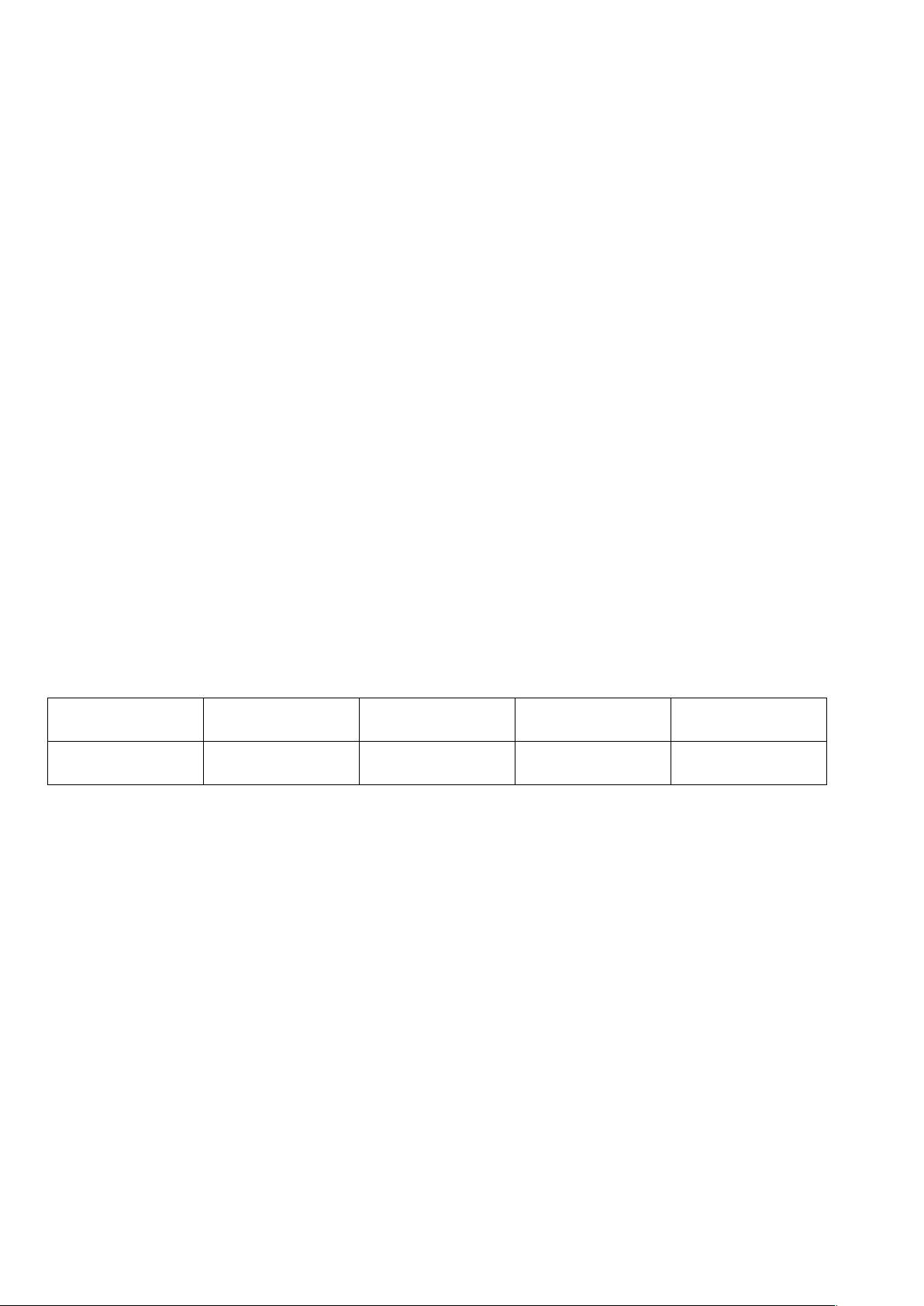

D. increased coordination between construction teams. Your answers 76. 77. 78. 79. 80. 81. 82. 83. 84. 85.

Part 5. The passage below consists of four paragraphs marked A, B, C and D. For questions 86-95, read

the passage and do the task that follows. Write your answers in the corrresponding numbered boxes provided. IT’S NOT FAIR

Do animals share our sense of unfairness over displays of greed?

A How often have you seen rich people take to the streets, shouting that they're earning too much?

Protesters are typically blue-collar workers yelling that the minimum wage has to go up, or that their jobs

shouldn't go overseas. Concern about fairness is always asymmetrical, stronger in the poor than the rich.

And the underlying emotions aren't as lofty as the ideal itself. Children become thoroughy indignant at the

slightest discrepancy in the size of their slice of pizza compared to their sibling's. Their shouts of "That's not

fair!" never transcend their own desires. We're all for fair play so long as it helps us. There's even an old

story about this, in which the owner of a vineyard rounded up labourers at different times of the day. Early

in the morning, he went out to find labourers, offering each 1 denarius. But he offered the same to those

hired later in the day. The workers hired first thing in the morning expected to get more since they had

worked through the heat of the day, yet the owner didn't feel he owed them any more than he had originally promised.

B That this sense of unfairness may turn out to be quite ancient in evolutionary terms as well became clear

when graduate student Sarah Brosnan and I discovered it in monkeys. When testing pairs of capuchin

monkeys, we noticed how much they disliked seeing their partner get a better deal. We would offer a pebble

to one of the pair and then hold out a hand so that the monkey could give it back in exchange for a cucumber

slice. Alternating between them, both monkeys would happily barter 25 times in a row. The atmosphere

turned sour, however, as soon as we introduced inequity. One monkey would still receive cucumber, while

its partner now enjoyed grapes, a favourite food with monkeys. While that monkey had no problem, the one

still working for cucumber would lose interest. Worse, seeing its partner with juicy grapes, this monkey

would get agitated, hurl the pebbles out of the test chamber, sometimes even those measly cucumber slices.

A food normally devoured with gusto had become distasteful.

C There is a similarity here with the way we reject an unfair share of money. Where do these reactions

come from? They probably evolved in the service of cooperation. Caring about what others get may seem

petty and irrational, but in the long run it keeps one from being taken advantage of. Had we merely

mentioned emotions, such as "resentment" or "envy," our findings might have gone unnoticed. Now we

drew the interest of philosophers, anthropologists and economists, who almost choked on the monkey

comparison. As it happened, our study came out at the very time that there was a public outcry about the

multimillion dollar pay packages that are occasionally given out on Wall Street and elsewhere.

Commentators couldn't resist contrasting human society with our monkeys, suggesting that we could learn a thing or two from them.

D Our monkeys have not reached the point at which their sense of fairness stretches beyond egocentric

interests - for example, the one who gets the grape never levels the outcome by giving it to the other - but in

cooperative human societies, such as those in which men hunt large game, anthropologists have found great

sensitivity to equal distribution. Sometimes, successful hunters aren't even allowed to carve up their own kill

to prevent them from favouring their family. These cultures are keenly aware of the risk that inequity poses

to the social fabric of their society. Apes, as opposed to monkeys, may have an inkling of this connection.

High-ranking male chimpanzees, for example, sometimes break up fights over food without taking any for

themselves. During tests, a female received large amounts of milk and raisins, but noticed her friends

watching her from a short distance. After a while, she refused all rewards. Looking at the experimenter, she

kept gesturing to the others, until they were given a share of the goodies. She was doing the smart thing.

Apes think ahead, and if she had eaten her fill right in front of the rest, there might have been repercussions

when she rejoined them later in the day.

In which section does the writer mention Your answers:

A robust response to news of the writer’s research? 86.

One animal harbouring resentment towards another? 87.

An animal thinking of the consequences of their actions? 88.

Any unfairness provoking a strong and egocentric reaction? 89.

The animal behaviour shown not going as far as equivalent human 90. behaviour?

A sense of injustice from people having to cope with adverse conditions? 91.

A justification for the irrational sense of unfairness? 92.

An animal’s feeling of injustice leading to preposterous behaviour? 93.

Unfairness among humans being perceived by those who are less well-off? 94.

Examples of both humans and animals behaving with fairness? 95. III. READING

Part 1. For questions 46-55, fill each of the following numbered blanks with ONE suitable word and

write your answers in the corresponding numbered boxes provided.

Today many people find that the pressure they have at work makes their jobs untenable as they have to put

their families totally in the (46)________. So working from home, being more at the (47)________ of your

family rather than your current boss, has great appeal to many as they (48)________ up their own businesses

from bedrooms or garages. But don’t just think about it. Now is the time to start, so (49)________ while the

iron’s hot. Providing you are disciplined in what you do, and embrace the (50)________ of working mostly

alone and without the team spirit (51)________ by working alongside others, then what’s stopping you?

You gain far more (52)________ as you can choose the working hours that suit you. You will still have to

meet deadlines, but they are ones that you or customers have (53)________. And if you are at a

(54)________ end during quiet times, you can go out and do things you couldn’t do before. But don’t get

(55)________ away with the idea of making millions. You’ll need to be determined and work hard to

succeed, but it’ll pay off in the end.

Part 2. For questions 56-68, read the following passage and do the tasks that follow. WHAT IS PERSONALITY?

A. We are all familiar with the idea that different people have different personalities, but what does this

actually mean? It implies that different people behave in different ways, but it must be more than that. After

all, different people find themselves in different circumstances, and much of their behaviour follows from

this fact. However, our common experience reveals that different people respond in quite remarkably

different ways even when faced with roughly the same circumstances. Alan might be happy to live alone in

a quiet and orderly cottage, go out once a week, and stay in the same job for thirty years, whilst Beth likes

nothing better than exotic travel and being surrounded by vivacious friends and loud music.

B. In cases like these, we feel that it cannot be just the situation which is producing the differences in

behaviour. Something about the way the person is ‘wired up’ seems to be at work, determining how they

react to situations, and, more than that, the kind of situations they get themselves into in the first place. This

is why personality seems to become stronger as we get older; when we are young, our situation reflects

external factors such as the social and family environment we were born into. As we grow older, we are

more and more affected by the consequences of our own choices (doing jobs that we were drawn to,

surrounded by people like us whom we have sought out). Thus, personality differences that might have been

very slight at birth become dramatic in later adulthood.

C. Personality, then, seems to be the set of enduring and stable dispositions that characterise a person.

These dispositions come partly from the expression of inherent features of the nervous system, and partly

from learning. Researchers sometimes distinguish between temperament, which refers exclusively to

characteristics that are inborn or directly caused by biological factors, and personality, which also includes

social and cultural learning. Nervousness,for example, might be a factor of temperament, but religious piety is an aspect of personality.

D. The discovery that temperamental differences are real is one of the major findings of contemporary

psychology. It could easily have been the case that there were no intrinsic differences between people in

temperament, so that given the same learning history, the same dilemmas, they would all respond in much

the same way. Yet we now know that this is not the case.

E. Personality measures turn out to be good predictors of your health, how happy you typically are – even

your taste in paintings. Personality is a much better predictor of these things than social class or age. The

origin of these differences is in part innate. That is to say, when people are adopted at birth and brought up

by new families, their personalities are more similar to those of their blood relatives than to the ones they grew up with.

F. Personality differences tend to manifest themselves through the quick, gut-feeling, intuitive and

emotional systems of the human mind. The slower, rational, deliberate systems show less variation in output

from person to person. Deliberate rational strategies can be used to over-ride intuitive patterns of response,

and this is how people wishing to change their personalities or feelings have to go about it. As human

beings, we have the unique ability to look in at our personality from the outside and decide what we want to do with it.

G. So what are the major ways personalities can differ? The dominant approach is to think of the space of

possible personalities as being defined by a number of dimensions. Each person can be given a location in

the space by their scores on all the different dimensions. Virtually all theories agree on two of the main

dimensions, neuroticism (or negative emotionality) and extroversion (or positive emotionality). However,

they differ on how many additional ones they recognise. Among the most influential proposals are openness,

conscientiousness and agreeableness. In the next section I shall examine these five dimensions.

Questions 56-62: There are seven paragraphs marked A-G in the passage. Choose the correct heading for

each paragraph from the list below. Write your answers in the corresponding numbered box provided. List of Headings I A degree of control Ii

Where research has been carried out into the effects of family on personality Iii

Categorising personality features according to their origin Iv

A variety of reactions in similar situations V

A link between personality and aspects of our lives that aren’t chosen Vi

A possible theory that cannot be true Vii Measuring personality Vii

Potentially harmful effects of emotions i Ix

How our lives can reinforce our personalities X

Differences between men’s and women’s personalities 56. Paragraph A 57. Paragraph B 58. Paragraph C 59. Paragraph D 60. Paragraph E 61. Paragraph F 62. Paragraph G

Questions 63-68: Do the following statements reflect the claims of the writer? Write your answers in the

corresponding numbered box provided. Write YES

if the statement reflects the claims of the writer NO

if the statement reflects the claims of the writer

NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

63. Alan and Berth illustrate contrasting behaviour in similar situations.

64. As we grow older, we become more able to analyse our personalities.

65. Nervousness is an example of a learned characteristic.

66. The discovery of differences in temperament has changed the course of psychological research.

67. Adopted children provide evidence that we inherit more of our personality than we acquire.

68. The rational behaviour of different people shows greater similarity than their emotional behaviour.

Part 3. In the passage below, seven paragraphs have been removed. For questions 69-75, read the

passage and choose from the paragraphs A-H the one which fits each gap. There is ONE extra

paragraph which you do not need to use.

VALUES FOR A GODLESS AGE

When the Berlin Wall came tumbling down in 1989 so did the plaster cast which had kept the idea of human

rights in limbo. It was now free to evolve in response to the changing conditions of the late twentieth century. 69.

Of course, in one sense, the quest for universal human rights standards after the Second World War was an

early attempt to communicate across national boundaries, albeit a rather faltering endeavour, with its claims

to universality challenged both in terms of authorship and content. More recently, a loosening of the reins of

the human rights dialogue has ushered in wider debate.. 70.

Perhaps the best known of these is Amnesty International, established in 1961. Before Amnesty, there were

very few organizations like it, yet now there are thousands operating all over the world. Whether

campaigning for the protection of the environment or third-world debt relief, any such organization is

engaged in the debate about fundamental human rights. And it is no longer just a soft sideshow. 71.

The fact that strangers from different countries can communicate with each other through the worldwide

web is having a similar effect in dealing a blow to misinformation. During one recent major human rights

trial over sixty websites sprang up to cover the proceedings, while sales of the government-controlled

newspaper in that country plummeted. 72.

The effect of increased responsibility at this highest level has been to continually extend the consideration of

who is legally liable, directly or indirectly, under international human rights law. In part, this is an

acknowledgement that even individuals need to be held responsible for flagrant breaches of others' rights,

whether these are preventing protesters from peacefully demonstrating or abusing the rights of children. 73.

It has been noted that paradoxically, in such circumstances, it may be in the interests of human rights

organizations to seek to reinforce the legitimacy and authority of the state, within a regulated global framework. 74.

Part of the new trend in human rights thinking is therefore to include powerful private bodies within its

remit. The International commission of Jurists has recently explored ways in which international human

rights standards could be directly applied to transnational corporations. 75.

Whatever the way ahead, the lessons of the past must be learnt. Any world view or set of values which is

presented as self-evident is ultimately doomed to failure. The case for human rights always needs to be made

and remade. In a world where globalization too often seems like a modernized version of old-fashioned

cultural imperialism, it is important to query the claim that human rights are universally accepted. The missing paragraphs:

A. This is, after all, a uniquely propitious time, as the values and language of human rights are becoming

familiar to more and more people, who judge the merits or otherwise of political and economic decisions

increasingly in human rights terms. Arguments seem fresh and appealing in many quarters where once they sounded weak and stale.

B. On a global scale, it is not strong states that are the problem here but weak ones, as they fail to protect

their citizens from private power -whether it is paramilitaries committing murder and torture or transnational

corporations spreading contamination and pollution.

C. The problem is that the growth of globalization makes the protection of nation states a pointless goal in

certain circumstances. Transnational corporations with multiple subsidiaries operating in a number of

countries simultaneously wield significant economic and political power and it is often extremely difficult

for the state - both home and host governments - to exercise effective legal control over them.

D. If the proliferation of pressure groups has raised the profile of the human rights debate, satellite

television has reinforced much of the content of their campaigns. The fact that from our armchairs we can all

see live what is happening to others around the world has had an enormous impact on the way the struggle

for human rights is viewed. It would not be remotely believable to plead ignorance nowadays, for 24-hour

news coverage from the world's hotspots reaches us all.

E. The results of its investigations were published in 1999 in a unique pamphlet on Globalization, Human

Rights and the Rule of Law. The issue to be faced is whether to treat these and other corporations as 'large

para-state entities to be held accountable under the same sort of regime as states', or whether to look for

different approaches to accountability 'that are promulgated by consumer groups and the corporations themselves'.

F. No longer the preserve of representatives of nation states meeting under the auspices of the United

Nations, a developing conversation is taking place on a global scale and involving a growing cast of people -

for an increasing range of pressure groups now frame their aspirations in human rights terms.

G. One of the most significant of these is what has come to be called 'globalization', the collapsing of

national boundaries in economic, political and cultural life. From the expanding role of the world's financial

markets and the spread of transnational corporations to the revolution in communications and information

technology, more and more areas of people's lives are affected by regional, international or transnational

developments, whether they are aware of this or not.

H. Not only must states not infringe rights, and enforce those rights which fall within their direct sphere

(like providing a criminal justice system or holding fair elections), but they also have 'positive obligations' to

uphold rights enshrined in human rights treaties, even when it is private parties which have violated them.

Part 4. For questions 76-85, read an extract from an article on Charles Darwin's Theory of Evolution

and choose the answer A, B, C or D that fits best according to the text.

[1] Charles Darwin's Theory of Evolution is known as one of the most important and controversial scientific

theories ever published. Darwin was an English scientist in the 19th century best known for his book “On

the Origin of Species.” In his book, Darwin postulated different species shared characteristics of common

ancestors, that they branched off from common ancestors as they evolved, and that new traits and

characteristics were a result of natural selection. The theory is based on the assumptions that life

developed from non-life and progressed and evolved in an indirect manner. Therefore, the Theory of

Evolution, while controversial, has shaped and influenced the modern scientific world's thinking on the

development of life itself. Darwin was born February 12, 1809 in England. Although initially entering into

medicine, Darwin chose to pursue his interest in natural science and embarked on a five-year journey aboard

the H.M.S. Beagle, a British sloop belonging to the Royal Navy. Because of his experience aboard the

Beagle, he laid the foundation for his Theory of Evolution while also establishing himself within the

scientific community. Specifically, Darwin's keen observation of the fossils and wildlife he saw during his

time on the Beagle served as the basis for the cornerstone of his theory: natural selection.

[2] Natural selection contributes to the basis of Darwin's Theory of Evolution. One of the core tenets of

Darwin's theory is that more offspring are always produced for a species than can possibly survive. Yet, no

two offspring are perfectly alike. As a result, through random mutation and genetic drift, over time offspring

develop new traits and characteristics. Over time beneficial traits and characteristics that promote survival

will be kept in the gene pool while those that harm survival will be selected against. Therefore, this natural

selection ensures that a species gradually improves itself over an extended duration of time. On the other

hand, as a species continues to 'improve' itself, it branches out to create entirely new species that are no

longer capable of reproducing together.

[3] Through natural selection, organisms could branch off of each other and evolve to the point where they

no longer belong to the same species. Consequently, simple organisms evolve into more complex and

different organisms as species break away from one another. Natural selection parallels selective breeding

employed by humans on domesticated animals for centuries. Namely, horse breeders will ensure that horses

with particular characteristics, such as speed and endurance, are allowed to produce offspring while horses

that do not share those above-average traits will not. Therefore, over several generations, the new offspring

will already be pre-disposed towards being excellent racing horses.

[4] Darwin's theory is that 'selective breeding' occurs in nature as 'natural selection' is the engine behind

evolution. Thus, the theory provides an excellent basis for understanding how organisms change over time.

Nevertheless, it is just a theory and elusively difficult to prove. One of the major holes in Darwin's theory

revolves around “irreducibly complex systems.” An irreducibly complex system is known as a system where

many different parts must all operate together. As a result, in the absence of one, the system as a whole

collapses. Consequently, as modern technology improves, science can identify these “irreducibly complex

systems” even at microscopic levels. These complex systems, if so inter-reliant, would be resistant to

Darwin's supposition of how evolution occurs. As Darwin himself admitted, “To suppose that the eye with

all its inimitable contrivance for adjusting the focus for different distances, for admitting different amounts

of light, and for the correction of spherical and chromatic aberration, could have been formed by natural

selection, seems, I free confess, absurd in the highest degree".

[5] In conclusion, “On the Origin of Species” is known as one of the most consequential books ever

published. Darwin's Theory of Evolution remains, to this day, a lightning rod for controversy. The theory

can be observed repeatedly, but never proven, and there are a plethora of instances that cast doubt on the

processes of natural selection and evolution. Darwin's conclusions were a result of keen observation and

training as a naturalist. Despite the controversy that swirls around his theory, Darwin remains one of the

most influential scientists and naturalists ever born due to his Theory of Evolution.

76. The word 'postulated' in paragraph 1 is closest in meaning to: A. disagreed B. proved C. opposed D. hypothesized

77. Which sentence is most similar to the following sentence from paragraph 1?

The theory is based on the assumptions that life developed from non-life and progressed and evolved in an indirect manner.

A. The Theory of Evolution is founded on evidence that non-organic compounds are the basis of life, developed in an unguided way.