Preview text:

International Journal of Educational Research 49 (2010) 195–209

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

International Journal of Educational Research

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / i j e d u r e s

Pedagogical treatment and change in preservice teacher beliefs: An experimental study Nihat Polat *

Department of Instruction and Leadership in Education, Duquesne University, 600 Forbes Avenue, 319 Fisher Hall, Pittsburgh, PA 15282, USA A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history:

This study addresses if preservice English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers’ beliefs Received 13 May 2010

about the effectiveness of authentic, commercial, and teacher-made instructional

Received in revised form 15 January 2011

materials can be changed after a semester-long pedagogical treatment. Data were Accepted 1 February 2011

collected from 90 preservice EFL teachers (Experimental: 45, Control: 45) at a public Available online 5 April 2011

university in Turkey using questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and retrospective

reflection essays. Data analyses involved t-tests, multivariate analysis of gain scores, and Keywords:

interview transcriptions. Findings suggested that although change in preservice teachers’ Preservice teachers

beliefs after a well-structured treatment was not very common, they were far from rare. Change

Qualitative results also revealed that some beliefs of participants became more favorable Beliefs

about the effectiveness of some aspects of these materials while others remained Materials Experimental

unchanged or became less favorable.

ß 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction

Instructional materials can greatly affect success in second language (L2) learning, particularly in EFL (English as a Foreign

Language) settings where learning is overwhelmingly contingent upon formal classroom instruction. Hence, selecting

effective instructional materials is an important concern for EFL teachers who, now, hold more autonomy and power in

decision-making than ever before. As they select materials, EFL teachers are affected by their beliefs about language learning

and teaching; however some of these beliefs can be detrimental to successful L2 education. Therefore, due to their beliefs,

EFL teachers may select and use materials that can negatively affect their students’ learning.

In the hope that they will re-evaluate and change those pre-existing beliefs that may be debilitating to L2 learning and

teaching, preservice EFL teachers undergo a substantial amount of course and fieldwork. Research has revealed that despite

their preservice education, teachers often unwittingly cling tightly to their beliefs because they are deeply rooted in life-long

experiences (Pajares, 1992; Peacock, 2001), which ultimately influence their classroom practice (Fang, 1996; Kagan, 1992;

Polat, 2009; Raths, 2001; Thompson, 1992). This study examines whether a strictly structured instructional treatment can

have an effect on altering preservice EFL teachers’ beliefs about the effectiveness of different kinds of instructional materials.

If the treatment is, in fact, effective in altering these specifically targeted beliefs, then we can be more hopeful that they will

make better choices in selecting materials as inservice teachers.

Although there has been considerable research on teacher beliefs, research of this kind in Foreign Language Education

(FLE) has either been limited to inservice teacher beliefs about instructional materials development or preservice teachers’

general beliefs about overall instructional practices. What appears to be lacking however, is research on preservice teachers’

* Tel.: +1 412 396 4464; fax: +1 412 396 1995.

E-mail address: polatn@duq.edu.

0883-0355/$ – see front matter ß 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2011.02.003 196

N. Polat / International Journal of Educational Research 49 (2010) 195–209

beliefs about the effectiveness of instructional materials. Using a mixed-method comparative analysis of experimental and

control groups, this study examines if preservice EFL teacher beliefs about the effectiveness of five aspects of authentic,

commercial, and teacher-made materials can be changed through a constructed treatment. As operationalized in this study,

authentic materials can include restaurant menus, newspapers, movies, and so forth while commercial materials (textbooks,

multimedia, and other professionally constructed materials) are created by publishing companies. Teacher-made materials

(written or recorded texts, worksheets, etc.) are created for a specific group of L2 learners by their teachers. 2. Literature review

2.1. Teacher beliefs about language teaching/learning

The construct of ‘teacher beliefs’ has been used extensively in many areas of educational research with numerous

operational definitions that often include components relating to teaching principles, epistemological perspectives, and

professional knowledge (Allen, 2002; Barcelos, 2003; Borg, 2003; Fang, 1996; Kagan, 1992; Nespor, 1987; Pajares, 1992;

Richardson, 1996). For example, Harvey (1986) defines beliefs as ‘‘a set of conceptual representations which signify to its

holder a reality or given state of affairs of sufficient validity, truth or trustworthiness to warrant reliance upon it as a guide to

personal thought and action’’ (p. 146), while Woods (1996) defines them as implicit theories. In an attempt to clear up what

he referred to as a messy construct in his seminal work almost two decades ago, Pajares (1992) examined the construct of

beliefs from a myriad number of different perspectives. He found that, in educational research, beliefs are generally defined

and operationalized in relation to numerous other factors such as cognition, self-efficacy, values, and knowledge, pointing to

the distinctions made between knowledge and beliefs as a difficult one.

One thing that most beliefs researchers have come to agree on is the fact that making a distinction between knowledge

and beliefs is very difficult if possible at all (Abelson, 1979; Borg, 2003; Breen & Candlin, 1987; Grossman, Wilson, &

Shulman, 1989; Lewis, 1990; Pajares, 1992; Verloop, Driel, & Meijer, 2001; Woods, 1996). Hence, such a distinction is

purposefully avoided because even one of the most cited beliefs researchers, Kagan (1992) stated that ‘‘most of a teacher’s

professional knowledge can be regarded more accurately as a belief’’ (p. 73), defining beliefs as a ‘‘piebald form of personal

knowledge’’ (p. 85). Teachers construct and articulate their personal knowledge, theories, perceptions, assumptions,

perspectives, ideologies, principles, and so forth in the form of belief systems or filtering them through belief structures

(Nespor, 1987). For that matter, teachers hold beliefs about what knowledge is, how it is acquired, and how it can be/is learnt

and taught as well. Therefore, in educational research, beliefs are generally used as representations of knowledge, theories,

and so forth (Pajares, 1992). In line with current research, this study adopts a comprehensive definition of beliefs that

represents an inter-dependent complex system of experiential, affective, cognitive, and meta-cognitive repertoire of

perceptions, perspectives, ideologies, knowledge, theories, and principles that are somewhat related to teachers’ decision-

making and instructional practices.

As categorized by Barcelos (2003), previous research about beliefs has used various research paradigms including

normative, metacognitive, and contextual approaches. Although findings of previous research have been unclear concerning

the interaction of beliefs and theoretical and practical variables, some studies have suggested that teachers hold many beliefs

about learning and teaching and that these beliefs are situated within the specific context of the sociocultural conditions

where learning takes place. Research has also revealed that there are firmly established reasons behind teacher beliefs (Polat,

2009) since they are shaped by teachers’ long-lived self-reflections, motivations, previous classroom experience, and so

forth, which may solely or interactionally affect the degree of change that can occur in beliefs in teacher education programs

(Nespor, 1987; Raths, 2001). Given that the formation of beliefs occurs experientially in a person’s life (Barcelos, 2003),

teacher educators may wish to explore ways for preservice teachers to re-evaluate and reshape their existing beliefs rather

than focusing on constructing new ones.

Research, particularly in EFL contexts, has also investigated teacher beliefs regarding L2 learners and learning (Horwitz,

1999), L2 teaching (McLean & Bullard, 2000), L2 teacher development (Peacock, 2001), and L2 subject matter and knowledge

(Freeman, 1994). A number of other studies have explored the relationship between EFL preservice teacher beliefs and their

classroom practices (Borg, 2003; Fang, 1996; Polat, 2009), L2 learning experience (Johnson, 1994; Numrich, 1996), and

teacher education programs (Cabaroglu & Roberts, 2000; Kagan, 1992). Although these studies have focused on rather

different aspects of preservice teacher beliefs, they have consistently reported that teachers hold stable pedagogical beliefs

about L2 learning and teaching, that their beliefs are not easy to change, that there are numerous reasons behind their beliefs,

and that their instructional practices are somewhat related to their beliefs.

Research on ‘change’ in preservice teacher beliefs, as a result of teacher education, is rather rare and controversial (Raths,

2001). Some studies have suggested that changing preservice teachers’ beliefs can be challenging (Pajares, 1992; Weinstein,

1989). For instance, Kagan (1992) suggested that preservice teachers’ beliefs did not change much during their teacher

education course and fieldwork. In a recent longitudinal study, Peacock (2001) reported that a three-year TESL instruction

program resulted in very little change in the beliefs of preservice teachers. On the other hand, other studies have found that it

is not rare to observe some change in preservice teacher beliefs as a result of a given pedagogical treatment (Freeman, 1994;

Richardson, 1996). For example, Stofflett and Stoddart (1994) and Tom (1997) have suggested that preservice teachers tend

to modify their existing beliefs during teacher preparation courses when their counterproductive beliefs are specifically

targeted. Similarly, Joram and Gabriele (1998) have suggested that special treatments that specifically target detrimental

N. Polat / International Journal of Educational Research 49 (2010) 195–209 197

beliefs can be effective in leading to change. This study hypothesizes that although changing preservice teachers’ beliefs

maybe difficult and challenging, it is far from rare.

2.2. Instructional materials and L2 education

Instructional materials play a critical role in overall instructional design because they can affect learning objectives and

activities, pedagogical content, and teacher and student roles and interactions (McGrath, 2002; Tomlinson, 2003). Although

the selection of instructional materials depends on the particularities of the socio-cultural setting and learners’ needs and

goals, it is particularly critical in EFL settings since L2 learners are overwhelmingly dependent on the comprehensible input

they receive through the instructional materials provided by their teachers. Littlejohn and Windeatt (1989) argued that

materials have both underlying instructional philosophies and methods and invisible curricula. Hence, considering the role

of instructional materials in EFL classrooms and the growing teacher autonomy in decision-making, selecting them is not a

trivial decision for teachers to make (Ur, 1996). What is more, the existing research on the effectiveness of different material

sources is rather contentious. For example, while some researchers underscored authenticity in instructional materials

(Clarke, 1989; Willis, 1996), others (Guariento & Morley, 2001) reported that authentic materials may be more effective for

high proficiency levels and in tasks where total comprehension is not expected.

Researchers like Omaggio-Hadley (2001), on the other hand, approached materials from a methods-perspective,

advocating for the use of both authentic and commercial materials. She argued that commercial materials like picture books

can make input more comprehensible for L2 learners with lower proficiency levels whereas authentic materials can enhance

the development of listening and reading skills by situating the experience in real-like contexts. Similarly, Jordan (1997)

suggested that non-authentic materials were more effective for earlier stages of L2 learning, but that authentic materials

were better for situations where students deal with materials from a familiar subject area. Others, like Martinez (2002)

claimed that authentic materials can be culturally biased and incomprehensible for learners with lower proficiency levels.

As for the effectiveness of commercial materials, Richards (2001) argued that the process of language learning has

historically been determined by commercial textbooks. While McGrath (2006) argued that textbooks are widely used in EFL

classes and highly acknowledged in L2 education, Allwright (1990) emphasized that because materials can control learning

and teaching, the use of textbooks may obstruct teacher freedom and flexibility. Similarly, Shannon (1983) suggested that

prescribed commercial materials make it seem like the materials are responsible for student learning, alienating teachers

from their profession. Although some researchers (Williams, 1983) underscored the adaptation of materials for specific

settings, others (Brown & Yule, 1983) highlighted what teachers can do with the pre-existing materials rather than trying to

find materials that would interest all learners in different contexts. In this sense, teacher-made materials maybe more

effective because they target specific audiences, and are more culturally heterogeneous and geographically diverse (Ariew,

1989). Others, like Jia, Eslami, and Burlbaw (2006) reported that ESL teachers perceived their personal materials to be more

objective since they were designed for specific learners and contexts.

Comparative research on the appropriateness and effectiveness of a wide variety of materials might be extremely helpful

for teachers. Such information might provide guidance for teachers in their decision-making. This idea is reinforced by

several studies that noted that teachers’ initial choices of materials, among other factors, influenced their classroom

practices (Brophy, 1982; McGrath, 2006; Shavelson & Stern, 1981). Thus, a more systematic examination of preservice EFL

teachers’ beliefs about different kinds of materials is warranted. This diagnostic analysis of beliefs can be the first step in

addressing whether preservice EFL teachers change their beliefs about these materials as a result of a structured pedagogical intervention. 3. Research design

Previous research has addressed the challenges involved in the study of teacher beliefs (Kagan, 1992; Woods, 1996),

identifying specific difficulties embedded in the empirical examination of beliefs (Pajares, 1992). Such research used

normative (Horwitz, 1999), metacognitive (Wenden, 1987), and contextual (Kramsch, 2003) approaches (to study beliefs,

Barcelos, 2003). Some used narratives and life histories to provide in-depth analyses of a few teachers’ beliefs (Fang, 1996;

Woods, 1996), while others used surveys to study teacher beliefs in broader frameworks using larger sample sizes (for

reviews see Arnett & Turnbull, 2007; Barcelos, 2003; Borg, 2003; Fang, 1996; Horwitz, 1999; Lee, 2005; Llurda, 2005; Pajares,

1992). Unlike most previous studies, this study utilizes a control group to provide empirical evidence of statistical

significance about changes in the beliefs of preservice teachers after a pedagogical treatment while triangulating the results

with qualitative data (Patton, 2002). 3.1. Participants and setting

Participants (N = 90) included 67 female and 23 male preservice EFL teachers selected from a large public university in

Eastern Turkey. Participants completed the same three and a half year undergraduate EFL program without any possibility of

elective courses. Curriculum analysis results indicated that all participants had taken both general education and area-

specific courses including methods of language teaching, basic linguistics, SLA theories, and language curriculum and

assessment. They also joined a practicum at middle-high schools in the city, completing the same assignments required for 198

N. Polat / International Journal of Educational Research 49 (2010) 195–209

graduation. Note that during the practicum, participants were randomly assigned to different cooperating teachers in groups of

five at 18 school districts under the supervision of two senior faculty members. The school districts were selected based on a set

of criteria (teacher quality, basic facilities, etc.) enforced by the university, and the cooperating teachers were trained to follow

the same guidelines and competencies that were also followed by the supervisors in assisting these preservice teachers.

Upon admission, students were randomly divided into two classes of 56 (4A/4B) by the department. After explaining the

project and its voluntary nature, only 97 students chose to participate in the study; however, data from seven students was

not used due to partial incompletion of surveys and/or partial or incomplete participation in the experiment. Analyses of

participants’ backgrounds indicated no noteworthy difference in their previous teaching experience or professional

development. Yet, most came from a variety of different cities and had been exposed to different instructional materials as L2

learners. Only two participants began part-time teaching positions while data collection was still in progress. 3.2. Research questions

This study explores preservice EFL teacher beliefs about the effectiveness of several aspects of different kinds of

instructional materials, as well as any changes in those beliefs. The research questions are:

1. Do preservice EFL teacher beliefs about the effectiveness of authentic, commercial, and teacher-made materials regarding

five aspects (pedagogy, program, learner, language, and practicality-related) vary significantly?

2. Did their beliefs change after the structured pedagogical treatment about the effectiveness of these instructional

materials? If so, for which of the five aspects of these materials did the change occur?

3.3. Experimental and control groups and the treatment

The current study was conducted in two intact classes; 4A was randomly assigned as the control and 4B as the

experimental group. An analysis of group GPAs also suggested that students were randomly grouped. The researcher taught

both groups the same required course entitled ‘Textbook analysis and evaluation’ using the same teaching philosophy,

instructional materials, and assessment methods. Unlike the control group (4A), the experimental group (4B) was offered

additional 20-min mini lessons by the researcher (a total of 280 min) regarding three different kinds of ESL/EFL materials

throughout the 14-week academic semester, focusing on the context of instructional materials as they related to various

aspects of instructional practices.

To make the connection between the treatment and change in beliefs clear and consistent, the content of the treatment

was meticulously based on specific items used in the questionnaires. Change, as operationalized and measured in this study,

refers to differences in a participant’s beliefs as reported on the pre- and post tests. In other words, rather than adopting a

broader definition of ‘‘change’’ as used in previous research, it is defined here as the difference between the pre- and post-test

scores of the experimental group as compared to the pre- and post-test scores of the control group in order to ensure that its

operationalization is consistent with the instrumentation and the measurement of the current study. For triangulation

purposes, the quantitative results were also supplemented with two qualitative sources. Hence, as measured in this study,

participants’ beliefs about aspects of these three kinds of materials could become significantly more favorable, less favorable,

or remain unchanged after the treatment.

The treatment aimed to engage participants in higher levels of thinking so that they would construct solid backgrounds, re-

evaluate, and then re-form their beliefs about the effectiveness of various aspects of authentic, commercial, and teacher-made

materials. Therefore, among numerous methods of instructional delivery, an explicit method based on Savignon and Sysoyev

(2002) comprising three stages of explanation, analysis, and evaluation was implemented. The explicit method not only

provided theoretical instructional opportunities for learners but it also engaged them in applying theoretical foundations and

thereby achieving higher levels of learning through affective and metacognitive synthesis and evaluation (Do¨rnyei, 1995).

The Explanation part, the first eight sessions of the treatment, comprised theoretical instruction, providing information

regarding the fundamental constructs and complexities of the five aspects of authentic, commercial, and teacher-made

materials as they related to numerous instructional components. These sessions also provided participants with basic

background knowledge about the effectiveness of these materials and situated their roles in overall EFL education. The first

Explanation sessions aimed to develop an understanding of the big picture behind the complexity of factors involved in the

analysis, evaluation, and selection of instructional materials. Namely, the connection between the effectiveness of

instructional materials and basic EFL teacher competencies including language aspects, SLA theories, EFL methods, L2 learner

variables, socio-cultural awareness, EFL curriculum, and assessment and evaluation was explained. For example, what kinds

of materials would an audio-lingual teacher use versus a Content/Task-Based instructor, and Why? During the remaining

sessions, the five aspects of the three kinds of materials (program and content-related, pedagogical, language-related,

learner-related, and practical) were further explored. Based on the questionnaire items (Appendix A), participants were first

taught about the effective use of materials in different kinds of programs and settings (Aspect 2), including EFL, ESL, ESP,

bilingual, and preparatory programs.

Next, differences between these materials regarding pedagogical considerations (Aspect 1) were explained. In other

words, based on questionnaire items, several comparisons were made for participants concerning the effective use of these

N. Polat / International Journal of Educational Research 49 (2010) 195–209 199

kinds of materials related to current EFL methods, teaching culture, kinds of tasks and activities, student and teacher roles

and interactions, and so forth. For instance, which of these is more effective in: teaching culture, providing more meaningful

tasks and activities, providing more collaboration and dialog among students? Which are more teacher-dependent? Which

are more effective as primary versus supplementary materials?

After pedagogical considerations, participants learned about the language-related aspects of these materials (Aspect 3).

Some of these sessions highlighted the quality of language and its use, while others emphasized the originality of contexts,

skills integration, and effectiveness in developing the Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BICS) and the Cognitive

Academic Language Proficiency (CALP) (Cummins, 2003). As for L2 learner variables (Aspect 4), these materials were

compared vis-a`-vis their effectiveness in being enjoyable, motivating, anxiety-provoking, and meeting the needs of learners.

They were also compared concerning certain issues including gender bias, and age and proficiency level appropriateness.

Finally, participants were instructed about how these materials differ regarding the quality of design, organization, form

variety, and availability (Aspect 5).

During the three Analysis sessions, following the Explanation part, participants individually worked to comparatively analyze

some sample materials pertaining to the five aspects. They were provided with specific items used in the Explanation part and

asked to use them as bases for their analyses. The final part of the treatment, Evaluation, was conducted in three sessions in

which participants wrote one evaluation report for each kind of material about its effectiveness in terms of the five aspects

utilizing specific items used in the Explanation and Analysis parts as bases for their evaluations. These sessions aimed to help

them engage in higher levels of thinking by re-evaluating, refining and re-forming their beliefs about these materials.

3.4. Measuring beliefs: instruments and procedures

Data collection included a Beliefs about EFL Materials Questionnaire (BAEFLMQ), semi-structured interviews,

retrospective reflection essays, practicum assignments and guidelines, and curriculum and coursework evaluations.

Student GPAs were also used to ensure randomization in group assignments. Both groups were given a pre-questionnaire

about their beliefs about the five aspects of authentic, commercial, and teacher-made materials during the first week of the

semester prior to the first treatment session. At the end of the semester both groups were given the same questionnaire

(delayed post-test) again to explore if any significant changes in beliefs had occurred. Note that this questionnaire was given

to participants three weeks after the semester had ended to minimize short-term information recall possibilities. The

questionnaire items are presented in categories in Appendix A.

Five randomly selected participants from the experimental group were also given 30-min semi-structured interviews for

the in-depth understanding of the phenomenon and for data triangulation purposes (Patton, 2002). Some of these interview

questions included: Do you think your beliefs about the effectiveness of these materials have changed after undergoing these mini

lessons? If so, about which aspects? How? Why? Why not? Each participant was also asked to write a retrospective reflection

(Brevig, 2006; Gass & Mackey, 2000) essay in which they explained if and how the treatment might have impacted any ‘change’ in their beliefs.

The BAEFLMQ was administered to groups of 45 students at two different sessions during the same day, aiming to

measure participants’ beliefs about the five aspects of authentic, commercial, and teacher-made materials. Using this survey,

participants reported their beliefs about each kind of material as compared to the others, indicating their answers on a Likert

scale from 1 to 5: (1) strongly disagree, and (5) strongly agree.

Participants’ beliefs about the pedagogical aspect were measured via BAEFLMQ on items related to methods, instructional

procedures, teacher–student roles and interactions, and so forth. While their beliefs about program-related considerations

were measured on differences between programs, their goals, learners’ needs, and so on, beliefs about the language aspect

were measured on items pertaining to content, context, skill integration, correct and natural language use, and the effective

use of BICS and CALP. Beliefs about learner-related considerations were measured on items comprising affective, cognitive,

and meta-cognitive learner variables, as well as age and gender. Finally, measurement of beliefs about the practicality aspect

included design, organization, and availability.

3.5. Standardization and reliability of the instrument

The BAEFLMQ was generated based on an extensive review of previous research and the feedback of several ‘beliefs’

researchers. Moreover, it was piloted and its internal consistency reliability was measured through Cronbach’s alpha, using

SPSS. The criteria for the selection of items were determined based on the assumption that a systematic evaluation of

different aspects of instructional materials, as presented in this study, must involve guidelines and checklists that are

rigorously grounded in existing theoretical and empirical research in the field. Therefore, two kinds of sources were utilized

in the selection process: (1) previous research on the role of instructional materials in the planning, implementation, and

assessment and evaluation of language learning and teaching, and (2) multiple materials evaluation checklists and

systematic evaluation guidelines published in top-tier journals. Thus, first, a large selection of SLA, L2 teacher education, and

applied linguistics literature on different roles that instructional materials might play in L2 learning and teaching were

reviewed and synthesized to identify the five aspects that are examined in this study (Allwright, 1990; Breen & Candlin,

1987; Clarke, 1989; Ellis, 1997; Guariento & Morley, 2001; Littlejohn & Windeatt, 1989; McDonough & Shaw, 1993; McGrath,

2002; Nunan, 2004; Richards, 2001). 200

N. Polat / International Journal of Educational Research 49 (2010) 195–209

Second, to triangulate the data and ensure the validity and reliability of the instrument only the items that were used in

multiple evaluation checklists that also yielded adequate internal reliability levels were included in the BAEFLMQ. More than

a dozen evaluation checklists, rubrics and guidelines that have been established as systematic instruments were analyzed for

item selection for each aspect under study (for these checklists and guidelines see: Allwright, 1981; Cunningsworth, 1995;

Reinders & Lewis, 2006; Sheldon, 1988; Tomlinson, 2003; Ur, 1996; Williams, 1983). As a result, 40 items that had been used

in multiple checklists and guidelines were then included in the pilot version of the instrument. This version was given to 32

other preservice teachers who were also in the same program. The reliability of responses to individual items on the pilot

version was determined using Cronbach’s alpha, a model that measures the internal consistency of items that are presumed

to measure the same construct (Stemler, 2004). Although the alpha levels for these 40 items ranged from .57 to .73, only six

items yielded alpha levels below .70, a level that is considered acceptable in educational research (Stemler, 2004). To

construct the final version these six items were deleted, which brought up the reliability of the instrument for the remaining

34 items to .73. The BAEFLMQ was, then, given to the participants in this study. Finally, another Cronbach’s alpha analysis

was performed to measure the internal consistency of participants’ responses to each item. Results revealed that the

BAEFLMQ was moderately reliable (a = .75), with alpha levels ranging from .70 to .74 for the individual items. 3.6. Data analysis

A series of both repeated measure and between-groups multivariate analyses of variance and t-tests were performed,

comparing and contrasting participants’ beliefs about the effectiveness of these materials vis-a`-vis the five aspects. To

examine possible changes in beliefs resulting from the treatment, a multivariate analysis of gain scores involving differences

between the pre-and post-test (questionnaires) data were performed for all aspects of these materials using SPSS. The

interviews were audio-taped, transcribed, and returned to participants for modifications or clarifications. Then, participants’

accounts regarding aspects of these materials were combined and synthesized (Rubin & Rubin, 2005). Analyses of

retrospective reflection essays involved shared themes related to the construct of ‘change’ in beliefs (Brevig, 2006). 4. Results 4.1. Quantitative

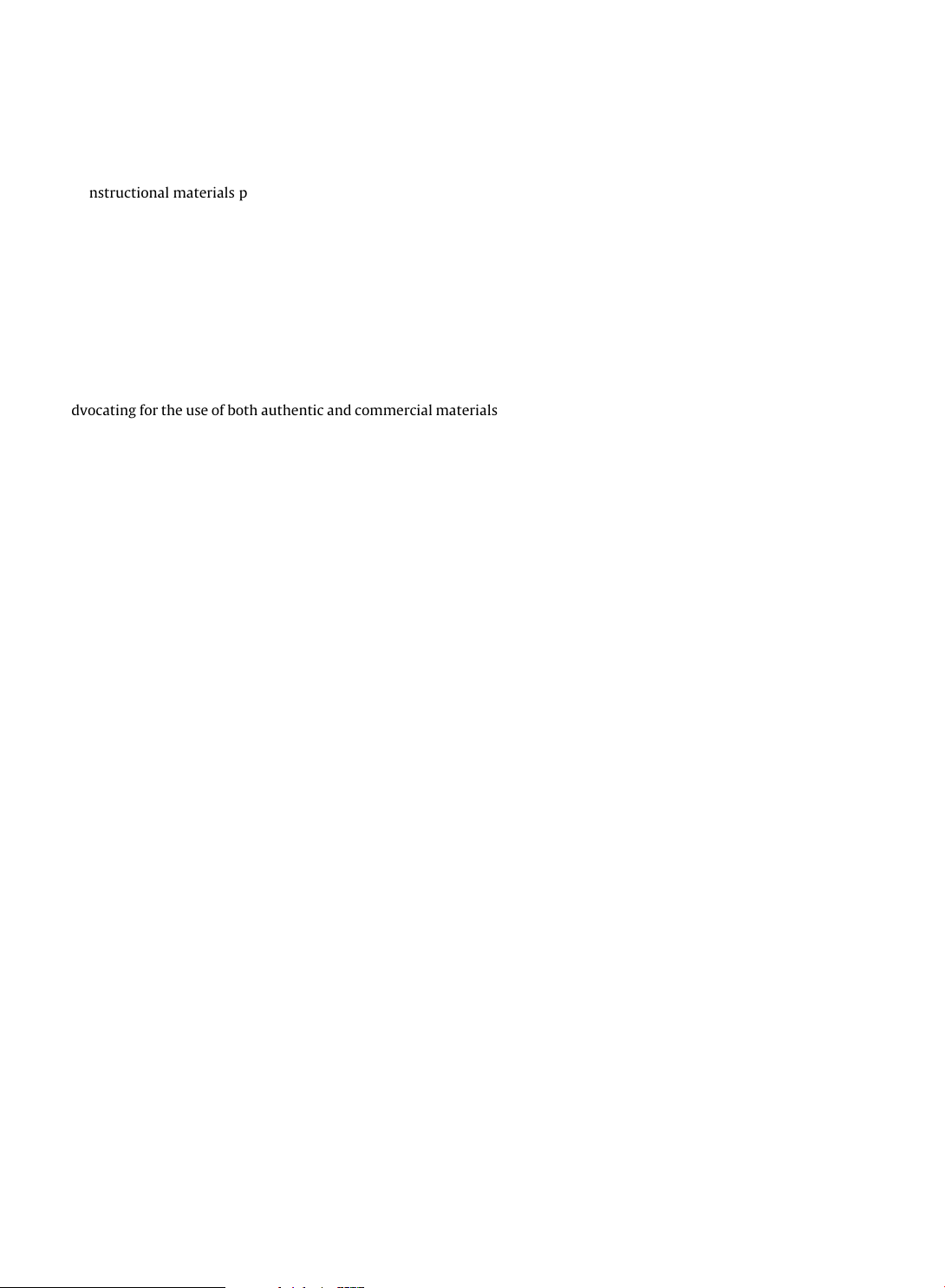

The first research questions addressed variation in the beliefs of all participants before the treatment. Therefore, based on

the pre-test data, participants’ mean scores for each kind of material as the dependent measure and the five aspects as the

repeated measure were inserted into a two-way ANOVA model. A statistically significant interaction effect was found for the

variation in participants’ beliefs about the effectiveness of different aspects of these materials, F(8, 82) = 19.05, p < .01,

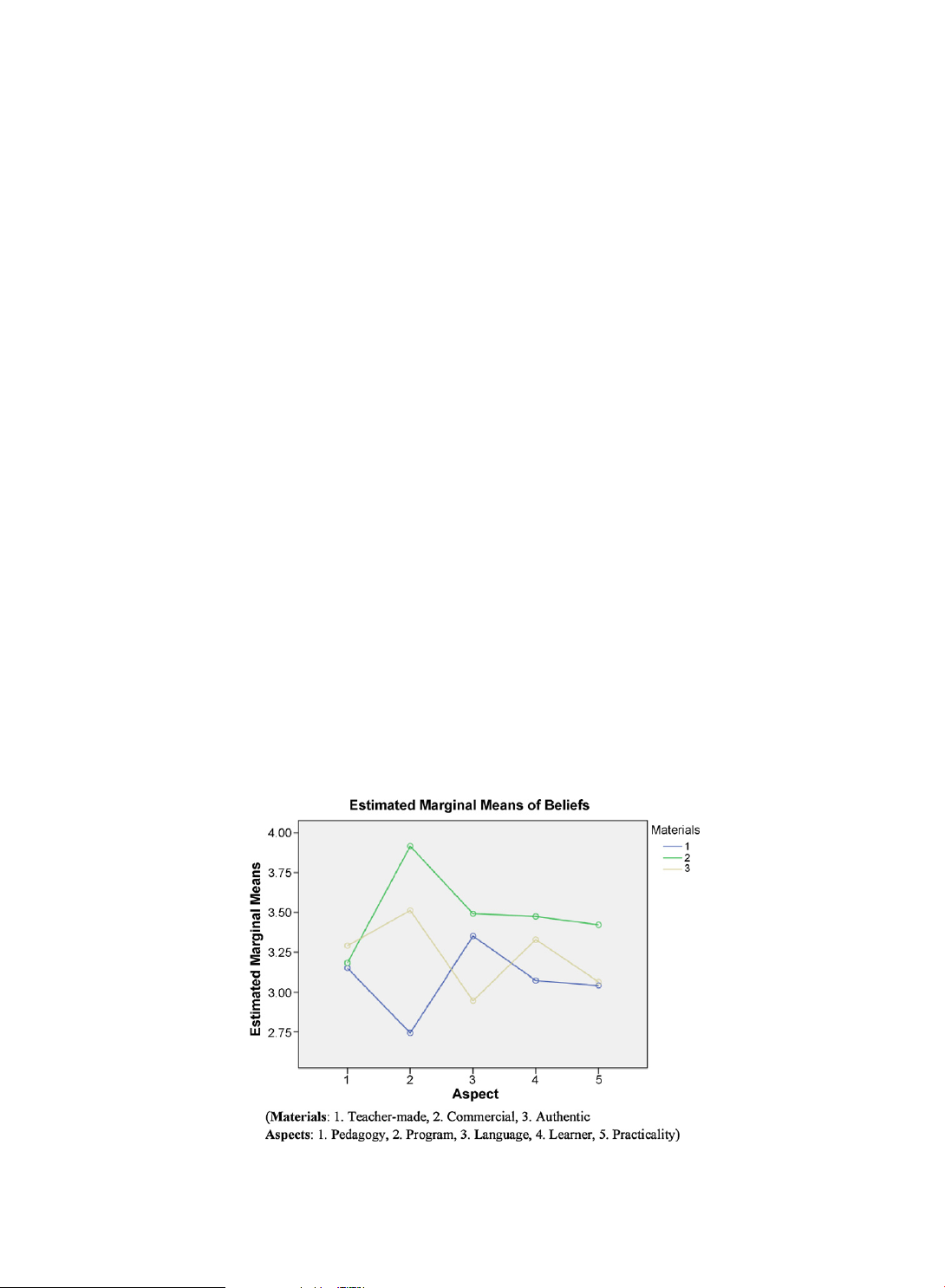

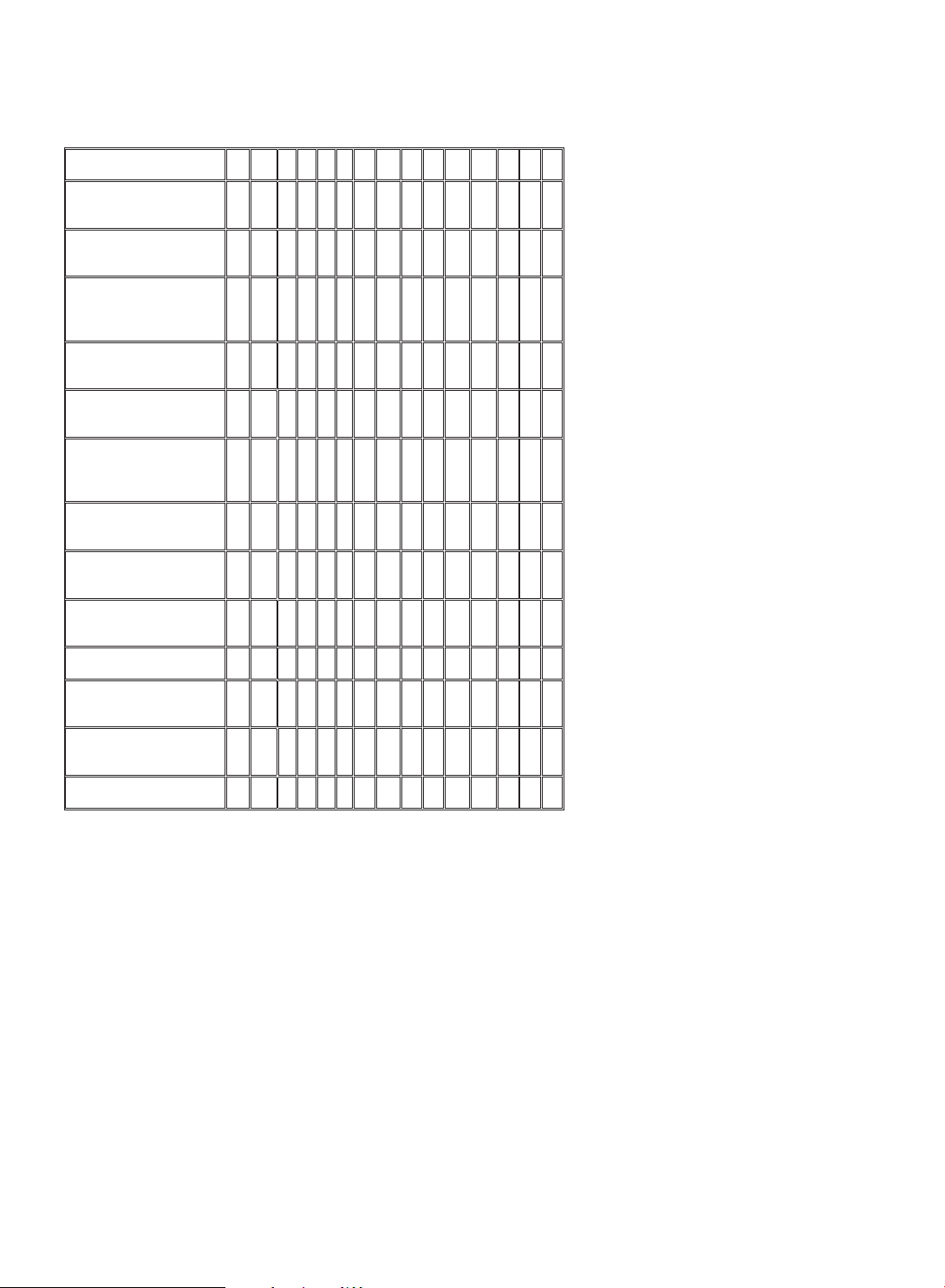

partial h2 = .65, d = .35 (Fig. 1). Therefore, 15 sets of paired t-tests were performed to address where the variance in beliefs existed. [()TD$FIG]

Fig. 1. The figure presents mean differences in participants’ beliefs regarding the five aspects of the three kinds of materials.

Materials: 1. Teacher-made, 2. commercial, 3. authentic.

Aspects: 1. Pedagogy, 2. program, 3. language, 4. learner, 5. practicality.

N. Polat / International Journal of Educational Research 49 (2010) 195–209 201 Table 1

Summary of the T-test results about variance in teacher beliefs prior to the treatment. Aspects/kinds TM-C TM-A C-A Aspect 1 (t = .473, p = .64) (t = 2.245, p = .027) (t = 1.532, p = .13) Aspect 2 (t = 16.816, p < .001) (t = 9.332, p < 001) (t = 6.292, p < 001) Aspect 3 (t = 2.479, p = .015) (t = 5.117, p < .001) (t = 8.950, p < 001) Aspect 4 (t = .6.653, p < .001) (t = 3.502, p < .01) (t = 2.245, p = .030) Aspect 5 (t = 4.919, p < .001) (t = .280, p = .78) (t = 4.299, p < .001)

Materials: 1. Teacher-made (TM), 2. commercial (C), 3. authentic (A).

Aspects: 1. Pedagogy, 2. program, 3. language, 4. learner, 5. practicality.

To avoid making a type 1 error, Bonferroni adjustments were made for each significance level. A Bonferroni adjustment

involves dividing a pre-determined significance level (i.e., .05) by the number of times a given test is performed. For example,

analyses for this study involve 15 (3 kinds of materials 5 aspects) sets of t-tests. Therefore, the significance level for each of

these t-tests was .0033 (i.e., .05/15). Despite the obtained overall significance concerning variation in beliefs, results indicate

that the reported beliefs varied significantly only regarding some aspects of these materials.

Table 1 demonstrates that in terms of the effective use of each kind of material in current ELT methods and meaningful

presentation, practice, and reinforcement of various tasks and activities, differences in the reported beliefs of these teachers

about teacher-made and commercial, teacher-made and authentic, and commercial and authentic materials were not

significant. Unlike Aspect 1, participants’ reported beliefs about all three sets of comparisons regarding Aspect 2 varied

significantly. In other words, participants reported significantly different beliefs about effective uses of these materials in

different programs (Table 1). Beliefs about the quality of language content and effectiveness in teaching different aspects of

language, Aspect 3, seemed to vary significantly for teacher-made and authentic and commercial and authentic but not for

teacher-made and commercial materials.

Table 1 also demonstrates that participants in this study appeared to believe that in terms of the effectiveness of these

materials as they relate to different aspects of learner variables (Aspect 4), teacher-made and commercial, and teacher-made

and authentic materials were different; however, their beliefs seemed to be similar concerning commercial and authentic

materials. Finally, Table 1 demonstrates that concerning overall organization, design, and availability (Aspect 5), participants

reported no difference in beliefs between teacher-made and authentic materials while their beliefs seemed to vary

significantly about teacher-made and commercial, and commercial and authentic materials.

Having found a significant amount of variation in beliefs, a three-way ANOVA was created to address if the treatment did,

in fact, lead to some ‘change’ in beliefs regarding these aspects of materials. Among other common methods of analyses for

pretest/posttest data (Warner, 2008), the ‘gain’ score design, a simpler form of analysis (APA Manual, 2005, p. 139) was used.

Using SPSS, gain scores and differences between pre- and post-test scores for each measure as dependent variables were

inserted into the multivariate analysis model, with the two treatment conditions as a between factor.

Results indicated that the change in the pattern of results across the five aspects of these materials was significant,

F(15,75) = 2.41, p < .05. Therefore, the next step was to explore where those differences in beliefs occurred as a result of the

treatment. Table 2 shows that statistically significant changes in beliefs occurred on five measures. Treatment seemed to

lead to change in beliefs about the effectiveness of three aspects of teacher-made materials and two aspects of commercial

materials. No significance was obtained for any aspect of the authentic materials.

Of the five statistically significant differences obtained regarding change in beliefs, three were about the teacher-made

materials. Table 2 demonstrates that, concerning such materials, the difference between the pre- and post-test scores of the

experimental and control groups for Aspect 1 is statistically significant, F(1,89) = 5.50, p < .05. This result confirmed that

participants’ beliefs about the pedagogical aspects of teacher-made materials became less favorable as a result of the treatment.

Another significant result about teacher-made materials was obtained for Aspect 3. Data revealed a significant difference,

F(1,89) = 4.75, p < .05, in change in beliefs between the experimental and control groups pertaining to the language-related Table 2

Mean differences regarding changes in beliefs about aspects of materials. Aspects/Ms Experimental Control Direction of change TM-Aspect 1 M = .344, SD = .54 M = .073, SD = .56 Negative TM-Aspect 3 M = .447, SD = .86 M = .097, SD = .64 Negative TM-Aspect 5 M = .462, SD = .75 M = .026, SD = .59 Negative CM-Aspect 2 M = .171, SD = .39 M = .107, SD = .77 Positive CM-Aspect 5 M = .393, SD = .69 M = .046, SD = .91 Positive AM-1,2,3,4,5 No change No change No change TM,C,A-Aspect 4 No change No change No change

Materials: 1. Teacher-made (TM), 2. commercial (C), 3. authentic (A).

Aspects: 1. Pedagogy, 2. program, 3. language, 4. learner, 5. practicality. 202

N. Polat / International Journal of Educational Research 49 (2010) 195–209

aspect of the teacher-made materials. The highest significance obtained for the difference in change in beliefs about teacher-

made materials between the experimental and control groups was related to practicality (Aspect 5), F(1,89) = 9.25, p < .05.

This result indicated that, after the treatment, participants’ beliefs became less favorable about the language-related aspect of teacher-made materials.

Although, quite unexpectedly, the treatment did not seem to result in any significant change in beliefs about the

effectiveness of any aspect of authentic materials, participants’ beliefs seemed to have changed about two aspects of

commercial materials. Table 2 shows that the two statistically significant changes that occurred concerning commercial

materials were related to Aspect 2, F(1,89) = 4.61, p < .05, and Aspect 5, F(1,89) = 4.11, p < .05. These results suggested that

participants’ beliefs about the effectiveness of commercial materials became more favorable, relating to both program-

related and practical aspects as a result of the treatment. 4.2. Qualitative

To capture an in-depth understanding of ‘change’ in beliefs, interviews and retrospective reflection essays from five

participants were analyzed. All five participants’ accounts consistently suggested that the treatment did generate

engagement in retrospective self-reflection and metacognitive evaluation (Gass & Mackey, 2000) of their beliefs about

numerous aspects of these materials. Results suggested that participants not only became more aware of the complex role of

instructional materials in L2 learning but also questioned and reformed their current beliefs about the effectiveness of these

materials. For example, Nevin, when asked if, how, and why her beliefs about the effectiveness of these materials changed

after undergoing these mini lessons, stated:

I never thought that materials can be related to so many things in foreign language teaching. . .I mean I did not know

that when you pick a material you automatically make decisions about teacher-student roles, instructional methods,

students’ motivation, and so forth. . .

Most of these accounts support the quantitative results, providing further evidence that a change in beliefs occurred in

both directions; participants’ beliefs became more favorable regarding certain aspects of some materials, while becoming

even less favorable about certain aspects of other materials after the treatment. For example, in response to the same

questions, another participant, Asli commented:

I always thought that teacher-made materials were most effective in terms of helping students to learn specific things

in class. . .But, now, I understand that they are very form-based and grammar-oriented and also very teacher-centered.

As we learned in the mini lessons, when you think about new ELT methods like task-based, these are not as effective as

commercial materials,. . .Commercial materials have CDs, videos, well-organized content. . .For example, I also think

teacher-made materials don’t have high quality language. . .They mostly have short sentences and easy words. . .

overall it’s like I+0 with only one new thing to learn. . .Maybe I used to think that they were most effective because the

teachers presented them best because they know their own materials best.

Moreover, data also indicated that as a result of these introspective reflection processes, participants developed a sense of

agency (Ball, 2009) and ownership about future decision-making pertaining to instructional materials. For instance, in the interview, Feride responded:

During my practicum my advisor (cooperating) teacher told me that the ELT teachers have a meeting in the beginning

of the year and they make decisions about books and materials. To be honest, I was not thinking about it, but after

these lessons, I am definitely thinking about going to this meeting when I start my job next year because the selection

of materials can affect everything. . .teacher-student roles, classroom activities, students’ motivation, and even testing. . .

Participants also commented on the effectiveness of the pedagogical treatment. Results suggested that the explicit

method of treatment delivery, particularly the analysis and evaluation stages, were rather effective in instigating

participants’ engagement in metacognitive reflection, reevaluation, and reformation of their beliefs about the effectiveness

of these materials. These results revealed that, as intended, these two particular stages of the explicit method did engage the

participants in higher levels of thinking (Do¨rnyei, 1995; Savignon & Sysoyev, 2002), triggering some targeted changes in

beliefs. For instance, in his retrospective reflection essay, Mahmut wrote:

I think I have changed my mind about some of these materials especially after I did the comparative analysis because it

was a lot of work and thinking. We had to compare the three kinds of materials about the five aspects. Therefore, we

had to really focus, think, and sometimes go back and look at our notes. . ..The part that influenced my beliefs mostly is

the evaluation stage because then I had to write the report and I had to consider every aspect of each kind of

material. . .Before I wrote my evaluation, I actually made a table for myself and wrote words or phrases about

comparisons and how my beliefs changed about which aspect. . .

The interview data also provided some interpretive evidence about why no significant changes in beliefs occurred about

any aspect of authentic materials after the treatment. Data suggested that participants made connections between their lack

N. Polat / International Journal of Educational Research 49 (2010) 195–209 203

of prior knowledge and previous exposure to authentic materials with their current uncertainty and ambivalence towards

the impact of the treatment on change in their beliefs. For instance, Zehra commented:

. . .I’m not sure, really, about authentic materials. . . I mean, when I was learning English people didn’t use authentic

materials. . .I never saw a real restaurant menu in English or watch real American movies in my English lessons. . .So, I

don’t. . .I. . .I. . .never thought of them as instructional materials until now. . .But even now, I cannot really picture in my

head about how, when, in which classes, for which students they can be more effective materials. . . 5. Discussion

Results of the study revealed a significant amount of variation in participants’ beliefs about the effectiveness of these

materials regarding five aspects; nevertheless, variation in beliefs was not present across all aspects of materials.

Participants’ beliefs did not seem to vary for teacher-made and commercial or for commercial and authentic materials

concerning the pedagogical aspects. Concerning the practical aspects, beliefs did not appear to vary for teacher-made and

authentic materials. As for overall organization, design, variety of forms and availability aspects, participants reported no

significant differences in effectiveness between teacher-made and authentic materials. This might be due to the lack of

confidence in teachers as professional materials developers (Richards, 2001); the fact that authentic materials are not

professionally developed; and that the availability of authentic materials is dependent on access to the Internet, and other socio-economic opportunities.

Preservice EFL teachers reported no significant differences in their beliefs about the effectiveness of these three types

of materials in meaningfully presenting, practicing and reinforcing various tasks and activities in EFL classrooms. This

result is interesting because it challenges Zacharias’ findings (2005) that many EFL teachers in Indonesia markedly

preferred internationally published commercial materials to local ones due to reasons including accurate language use

and availability. This result reveals that beliefs of preservice teachers’ in Turkey may be different from those of teachers

in Indonesia, supporting Barcelos’ (2003) argument that beliefs are situated within the particulars of a socio-cultural

context. Notably, although no significant variation in the pedagogical aspect was obtained for two of the three paired

comparisons between kinds of materials; it is one of the five areas in which change in beliefs occurred after the treatment.

Several researchers (Pajares, 1992; Peacock, 2001; Raths, 2001; Tatto, 1998) have suggested that teacher education is

not very effective in changing beliefs. Findings of this study reveal that structured treatments can lead to some

significant changes in specifically targeted beliefs. Results suggested changes in participants’ beliefs concerning three

aspects of teacher-made and two aspects of commercial materials, indicating approximately a 30% change. Note that

these results were also triangulated with the interview and retrospective reflection essay data. Unlike some previous

studies, these findings, especially those pertaining to teacher-made and commercial materials, reveal that while some

teacher beliefs have become more favorable, others appeared to become less favorable about certain aspects of some materials.

Results suggested that, after the treatment, preservice EFL teacher beliefs became more favorable about the

effectiveness of teacher-made materials regarding the pedagogical, language-related, and practical aspects. These

results are interesting because they suggest that changes in teacher beliefs are not as markedly rare as some previous

studies have suggested (Peacock, 2001). Participants were exposed to both theoretical and practical knowledge about

the five aspects of these materials through an explicit method of treatment (Savignon and Sysoyev, 2002). Consequently,

as documented in the qualitative data, after undergoing the treatment, particularly the analysis and evaluation stages,

participants altered some of their beliefs about the effectiveness of teacher-made materials compared to commercial and authentic materials.

As for commercial materials, results indicated that the two statistically significant changes that occurred in

participants’ beliefs were tied to program-related considerations and practical aspects, suggesting that observing some

change in teacher beliefs as a result of teacher education is not uncommon (Freeman, 1994; Richardson, 1996). In other

words, unlike the situation for teacher-made materials, participants came to believe that, compared to teacher-made

and authentic materials, commercial materials are more effective in offering learning opportunities in different

programs such as ESL/EFL, bilingual, preparatory, and so forth. Similarly, participants reported a changed belief that

commercial materials are the most effective concerning content, context, skills integration, correct and natural language

use, and effective use of BICS and CALP. These results are also rather evident in the qualitative accounts and are in

agreement with Joram and Gabriele’s (1998) findings that special treatments targeting specific preservice teacher

beliefs can be effective in leading to change.

It is interesting that no statistically significant change in beliefs occurred for any aspect of authentic materials. The

retrospective reflection essays suggested that this may have been due to relatively underdeveloped beliefs about such

materials since, as argued by Raths (2001), teachers construct beliefs as a result of their previous experiences. Considering

the EFL situation in Turkey participants had very little experience (Polat, 2008) with such materials as EFL learners, and used

the treatment as an opportunity to construct new beliefs rather than alter their existing beliefs about them. Although some

differences between participants’ pre- and post-test scores existed, the treatment did not seem to help participants construct

new beliefs that were significantly different. As evidenced in the qualitative data, this appears to have been due to a number 204

N. Polat / International Journal of Educational Research 49 (2010) 195–209

of reasons, including a lack of ‘‘apprenticeship of observation’’ (Lortie, 1975) that would have provided opportunities for

reflection, lack of classroom experiences with such materials as L2 learners (Horwitz, 2008), or the longer time typically

needed for teacher candidates to develop new beliefs (Zeichner & Tabachnick, 1981). 6. Implications

Many of us who teach in EFL/ESL teacher education programs occasionally encounter student questions about

instructional materials such as: How do materials relate to the learner’s age, gender, proficiency level, goals, and motivation?

Can materials make learning activities teacher or student-centered? Should materials integrate literacy, language skills, and

content areas? Undoubtedly, the most exciting part of these questions is the indication that preservice teachers are aware of

the potential role of instructional materials. Given the differences in preservice teachers’ answers, it is not surprising that

Cotton (2006) found that teachers were unwilling to use materials that went against their beliefs about instructional

materials. This supports the notion that only a substantial change in beliefs can lead to actual changes in instructional practices.

In brief, this study makes the following claims: preservice EFL teacher beliefs vary significantly about different

aspects of instructional materials, and structured treatments can lead to change in some specifically targeted beliefs.

These findings propose several direct implications for EFL/ESL teacher education programs. To assure consistency

between beliefs and recommended instructional practices, and thereby the achievement of teacher and program goals,

teacher education programs need to examine preservice teacher beliefs about multiple instructional constituents

(Lazaraton & Ishihara, 2005), making them more realistic and current-theory and research-oriented (Richardson, 1996).

The obtained statistically significant differences in participants’ beliefs after the treatment are heartening, indicating

that teacher education is making an impact on preservice teachers’ beliefs.

Finally, recent developments in ESL/EFL methods, especially the development of content and task-based approaches

(Horwitz, 2008), have triggered special concerns about instructional materials. Undoubtedly, due to new teacher roles as

scaffolders, materials developers, and socio-cultural environment designers, as well as the overwhelming amount of CALL

and other commercial materials, L2 teacher education programs have to make some changes in order to incorporate

courses about the selection and use of instructional materials (Richardson, 1996). For example, although teachers did not

used to have much say in textbook selection in many EFL settings, they are currently gaining more power to select

materials, and the findings of this study suggest that preservice teachers do hold different kinds of beliefs about numerous

aspects of different kinds of instructional materials. Hence, with the use of computers in many EFL settings, EFL teachers

need to become more competent both in constructing their own materials and adapting authentic materials for their

students. After all, preservice teachers seem to believe that some materials are more effective than others in facilitating student learning.

7. Limitations and future directions

The current study was limited in the fact that, like other socio-psychological factors, ‘pedagogical beliefs’ (Barcelos,

2003) is an abstract construct; therefore the operationalization and quantification of such a construct in surveys can

pose some inherent subjectivity issues despite efforts to minimize this potential risk trough the qualitative data. Also,

the use of intact groups has its own limitations that may confound the interpretation of some findings. Moreover,

although the length of study (14 weeks) and the statistical measures of significant variance should reduce a possible

Hawthorne effect, some change in participants’ beliefs could have occurred due to their awareness of being studied

(Landsberger, 1961). Finally, although these preservice teachers were randomly assigned to their supervising faculty

members and cooperating teachers who strictly followed the practicum guidelines, their beliefs about instructional

materials may still have been affected by differences in their practicum experience.

Results suggest that the treatment seems to have resulted in altering some beliefs about certain aspects of some

kinds of materials, while other beliefs seemed to have remained unchanged. Taken together, these results might suggest

that, if specifically targeted, well structured pedagogical treatments can help preservice teachers reform their

pedagogical beliefs about various aspects of instructional planning and practice. Therefore, teacher education programs

should identify and analyze teacher beliefs about fundamental instructional components and design their programs

accordingly to ensure more effective practices. The findings of this study, then, raise a question about the nature and

kinds of beliefs that have and have not changed after the treatment. Hence, why and how these teachers have come to

construct such beliefs about different aspects of these materials also needs to be examined through a mixed-method design. Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Jeff Miller for his input on the data analysis section of this study. I am deeply grateful to all the preservice

teachers, particularly the experimental group, for their participation. I also acknowledge with thanks the IJER reviewers for their constructive feedback.

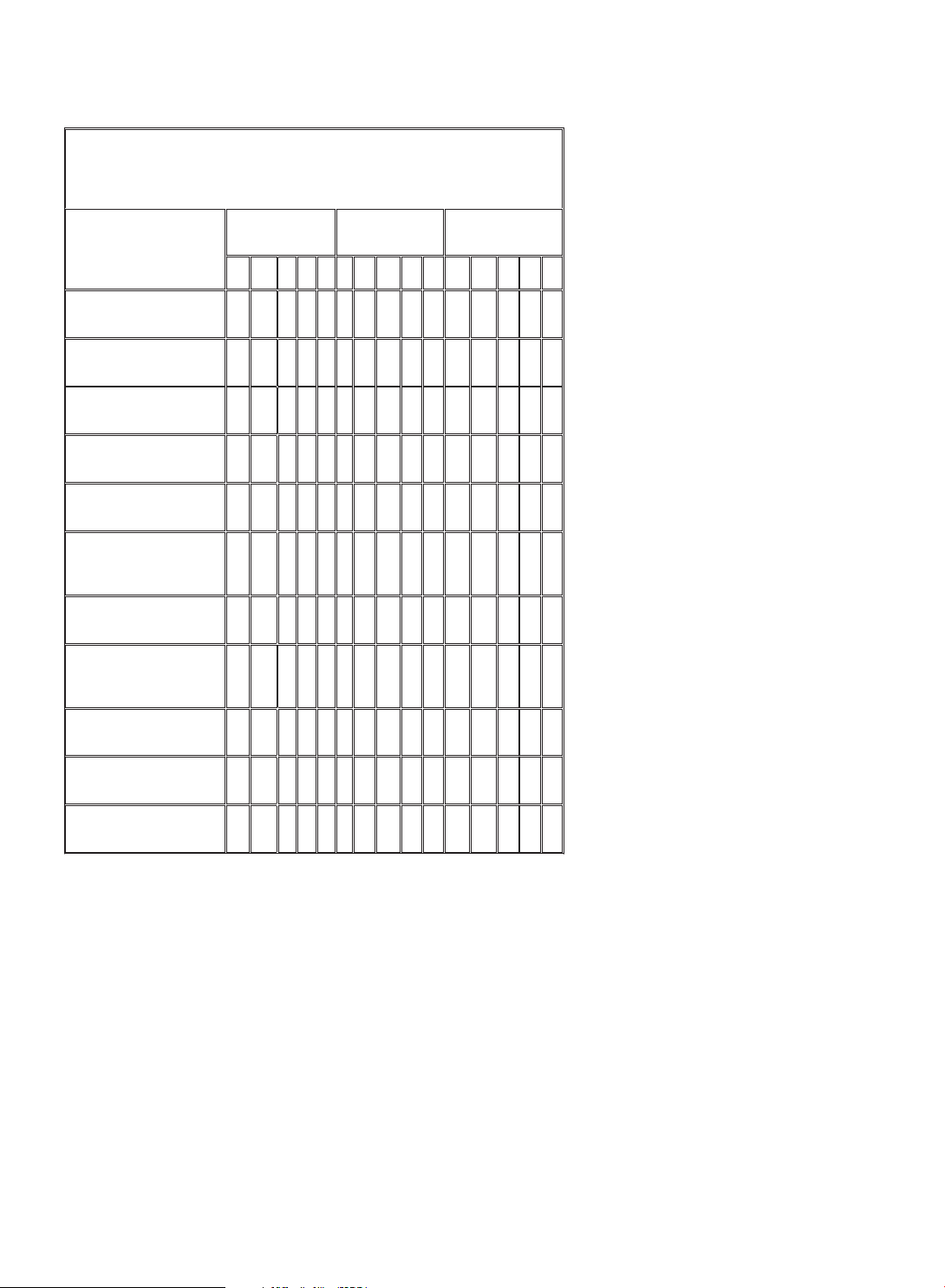

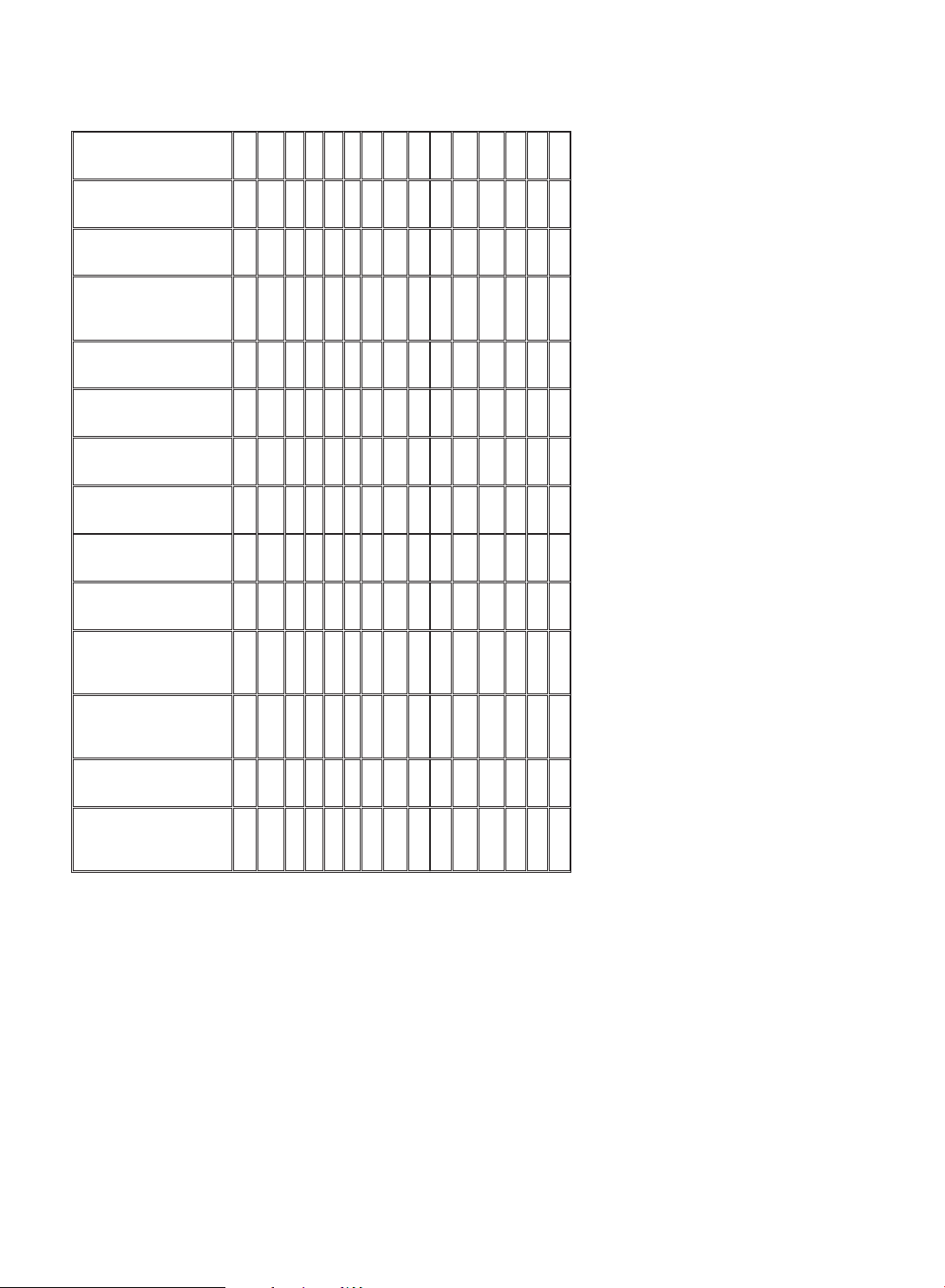

N. Polat / International Journal of Educational Research 49 (2010) 195–209 205 Appendix A. Questionnaires

Below are some beliefs that people might have about different kinds of materials used

in foreign language education settings. Please, read each statement and then decide if

you (1) strongly disagree, (2) disagree, (3) neither agree not disagree, (4) agree, (5) strongly agree. Teacher-Made Commercial Authentic Materials (TM) Materials (C) Materials (A) 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1.Pedagogical Considerations Are more effective to use with current methods. Are more appropriate and effective to teach culture Are more teacher- dependent. Provide more varied tasks and activities. Are more effective to practice and reinforce a task. Provide more meaningful tasks and activities Encourage more collaboration and dialog among students. Are more effective as supplementary sources. Are more effective as primary sources. 2. Program-Related Considerations 206

N. Polat / International Journal of Educational Research 49 (2010) 195–209 Appendix A. (Continued) Are more effective for EFL settings. Are more effective for ESL settings. Are more effective in bilingual programs. Are more effective in language preparatory programs. Are more effective for ESP/EAP programs. 3. Language-Related Consideration Have richer language content. Have more original > contexts. Language skills better integrated. Have more correct and natural language. Are more effective for Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills. Are more effective for Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency. 4. Learner-Related Considerations Are better well-suited to needs and objectives of specific learners

N. Polat / International Journal of Educational Research 49 (2010) 195–209 207 Appendix A. (Continued) Have less gender bias Have more age- appropriate content. Have more level- appropriate content. Maintain the learners’ interest and attention better. Make learners more anxious. Are more enjoyable to work with. Are better for intermediate and lower- level learners. Are better for upper and advanced learners. 5.Practical Considerations Have more visually appealing designs. Are more well-organized. Are more professionally developed. Are available in various forms. Are more easily available

**Note that in the actual questionnaires the items were randomly ordered. They are presented here in terms of the aspects under

study to make the review process easier. References

Abelson, R. P. (1979). Differences between belief and knowledge systems. Cognitive Science, 3, 355–366.

Allen, L. Q. (2002). Teachers’ pedagogical beliefs and the standards for foreign language learning. Foreign Language Annals, 35, 518–529.

Allwright, R. L. (1981). What do we want teaching materials for? ELT Journal, 36(1), 5–18.

Allwright, R. L. (1990). What do we want teaching materials for? In R. Rossner & R. Bolitho (Eds.), Currents in language teaching (pp. 131–147). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ariew, R. (1989). The textbook as curriculum. In T. Higgs (Ed.), Curriculum, competence and the foreign language teacher (pp. 11–34). Illinois: National Textbook

Company, The Penn State University.

Arnett, K., & Turnbull, M. (2007). Teacher beliefs in second and foreign language teaching: A state-of-the-art review. In H. J. Siskin (Ed.), From thought to action:

Exploring beliefs and outcomes in foreign language programs (pp. 9–28). Boston, MA: Thomson & Heinle.

Ball, A. F. (2009). Toward a theory of generative change in culturally and linguistically complex classrooms. American Educational Research Journal, 46, 45–72.

Barcelos, A. M. F. (2003). Researching beliefs about SLA: A critical review. In P. Kalaja & A. M. F. Barcelos (Eds.), Beliefs about SLA: New research approaches (pp. 7–

33). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Borg, S. (2003). Teacher cognition in language teaching: A review of research on what language teachers think, know, believe, and do. Language Teaching, 36(2), 81–109.

Breen, M., & Candlin, C. (1987). Which materials? A consumer’s and designer’s guide. In Sheldon, L. (Ed.). ELT textbooks and materials: Problems in evaluation and

development. ELT Documents 126. (pp.13–38). .

Brevig, L. (2006). Engaging in retrospective reflection. The Reading Teacher, 59, 522–530. 208

N. Polat / International Journal of Educational Research 49 (2010) 195–209

Brophy, J. (1982). How teachers influence what is taught and learned in classrooms. Elementary School Journal, 83, 1–13.

Brown, G., & Yule, G. (1983). Teaching the spoken language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cabaroglu, N., & Roberts, J. (2000). Development in student teachers’ pre-existing beliefs during a 1-year PGCE programme. System, 28, 387–402.

Clarke, D. F. (1989). Communicative theory and its influence on materials production. Language Teaching, 22, 73–86.

Cotton, D. R. E. (2006). Implementing curriculum guidance on environmental education: The importance of teachers’ beliefs. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 38, 67– 83.

Cummins, J. (2003). BICS and CALP: Origins and rationale for the distinction. In C. B. Paulston & G. R. Tucker (Eds.), Sociolinguistics: The essential readings (pp. 322– 328). London: Blackwell.

Cunningsworth, A. (1995). Choosing your coursebook. Oxford: Heinemann.

Do¨rnyei, Z. (1995). On the teachability of communicative strategies. TESOL Quarterly, 29, 55–85.

Ellis, R. (1997). The empirical evaluation of language teaching materials. ELT Journal, 1, 36–42.

Fang, Z. (1996). A review of research on teacher beliefs and practices. Educational Research, 38, 47–65.

Freeman, D. (1994). Knowing into doing: Teacher education and the problem of transfer. In D. C. S. Li, D. Mahoney, & J. C. Richards (Eds.), Exploring second language

teacher development (pp. 1–20). Hong Kong: City Polytechnic of Hong Kong.

Gass, S. M., & Mackey, A. (2000). Stimulated recall methodology in second language research. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Grossman, P. M., Wilson, S. M., & Shulman, L. S. (1989). Teachers of substance: Subject matter knowledge for teaching. In M. C. Reynolds (Ed.), Knowledge base for

the beginning teacher (pp. 23–36). Oxford: Pergamon.

Guariento, W., & Morley, J. (2001). Text and task authenticity in the EFL classroom. ELT Journal, 4, 347–353.

Harvey, O. J. (1986). Belief systems and attitudes toward the death penalty and other punishments. Journal of Psychology, 54(2), 143–159.

Horwitz, E. K. (1999). Cultural and situational influences on foreign language learners’ beliefs about language learning: A review of BALLI studies. System, 27, 557– 576.

Horwitz, E. K. (2008). Becoming a language teacher: A practical guide to second language learning and teaching. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Jia, Y., Eslami, Z. R., & Burlbaw, L. M. (2006). ESL teachers’ perceptions and factors influencing their use of classroom-based reading assessment. Bilingual Research Journal, 30, 407–430.

Johnson, K. E. (1994). The emerging beliefs and instructional practices of preservice English as a second language teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 10(4), 439–452.

Joram, E., & Gabriele, A. (1998). Preservice teacher’s prior beliefs: Transforming obstacles into opportunities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 2, 175–191.

Jordan, R. R. (1997). English for academic purposes: A guide and resource for teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kagan, D. M. (1992). Implication of research on teacher belief. Educational Psychologist, 27, 65–70.

Kramsch, C. (2003). Metaphor and the subjective construction of beliefs. In P. Kalaja & A. M. F. Barcelos (Eds.), Beliefs about SLA: New research approaches (pp. 109–

128). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Landsberger, H. A. (1961). Hawthorne Revisited. The American Catholic Sociological Review, 22, 76–77.

Lazaraton, A., & Ishihara, N. (2005). Understanding second language teacher practice using microanalysis and self-reflection: A collaborative case study. The

Modern Language Journal, 4, 529–542.

Lee, O. (2005). Science education and English language learners: Synthesis and research agenda. Review of Educational Research, 75, 491–530.

Lewis, H. (1990). A question of values. New York: Harper & Row.

Littlejohn, A., & Windeatt, S. (1989). Beyond language learning: Perspective on materials design. In R. K. Johnson (Ed.), The second language curriculum (pp. 155–

175). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Llurda, E. (2005). Non-native language teachers; perceptions, challenges and contributions to the profession. New York: Springer Science.

Lortie, D. (1975). Schoolteacher: A sociological study. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Martinez, A. (2002). Authentic materials: An overview. Karen’s Linguistic Issues. Retrieved from http://www3.telus.net/linguisticsissues.

McDonough, J., & Shaw, C. (1993). Materials and methods in ELT. Oxford: Blackwell.

McGrath, I. (2002). Materials evaluation and design for language teaching. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

McGrath, I. (2006). Teachers’ and learners’ images for coursebooks. ELT Journal, 60, 171–180.

McLean, M., & Bullard, J. E. (2000). Becoming a university teacher: Evidence from teaching portfolios. Teacher Development, 4(1), 79–101.

Nespor, J. (1987). The role of beliefs in the practice teaching. Curriculum Studies, 19, 317–328.

Numrich, C. (1996). On becoming a language teacher: Insights from diary studies. TESOL Quarterly, 30, 131–153.

Nunan, D. (2004). Task-based language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Omaggio-Hadley, A. (2001). Teaching language in context. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 3, 307–332.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Peacock, M. (2001). Preservice ESL teachers’ beliefs about second language learning: A longitudinal study. System, 29, 177–195.

Polat, N. (2008). Pre-service teachers’ general and specific beliefs about authentic, commercial and teacher-made EFL materials: Pedagogical and practical

considerations. In N. Kunt, J. Shibliyev, & F. Erozan (Eds.), ELT profession: Challenges & prospects (pp. 114–122). Lincom Studies in Second Language Teaching, Germany: LINCOM Publishing.

Polat, N. (2009). Matches in beliefs between teachers and students, and success in L2 attainment: The Georgian example. Foreign Language Annals, 42, 229–249.

Raths, J. (2001). Teachers’ beliefs and teaching beliefs. Early Childhood Research & Practice, 3, 385–392.

Reinders, H., & Lewis, M. (2006). An evaluative checklist for self-access materials. ELT Journal, 60(3), 272–278.

Richards, J. C. (2001). Curriculum development in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Richardson, V. (1996). The role of attitudes and beliefs in learning to teach. In J. Sikula (Ed.), Handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 102–119). New York: MacMillan.

Rubin, H. J., & Rubin, I. S. (2005). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Savignon, J. S., & Sysoyev, V. P. (2002). Sociocultural strategies for a dialogue of cultures. The Modern Language Journal, 86, 508–521.

Shannon, P. (1983). Commercial reading materials, a technological ideology, and the deskilling of teachers. The Elementary School Journal, 87, 307–329.

Shavelson, C., & Stern, P. (1981). Research of teachers’ pedagogical thoughts, judgments, decisions, and behavior. Review of Educational Research, 51, 455–498.

Sheldon, L. (1988). Evaluating ELT textbooks and materials. ELT Journal, 42, 237–246.

Stemler, S. E. (2004). A comparison of consensus, consistency, and measurement approaches to estimating inter-rater reliability. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 9, 1–19.

Stofflett, R. T., & Stoddart, T. (1994). The ability to understand and use conceptual change pedagogy as a function of prior learning experience. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 1, 31–51.

Tatto, M. T. (1998). The influence of teacher education on teachers’ beliefs about purposes of education, roles. Journal of Teacher Education, 49, 66–77.

Thompson, A. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and conceptions: A synthesis of the research. In D. Grouws (Ed.), Handbook of research in mathematics teaching and learning

(pp. 127–146). New York: MacMillan.

Tom, A. R. (1997). Redesigning teacher education. Albany, NY: SUNYP.

Tomlinson, B. (Ed.). (2003). Developing materials for language teaching. London: Continuum International.

Ur, P. (1996). A course in language teaching: Practice and Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Verloop, N., Driel, J. V., & Meijer, P. C. (2001). Teacher knowledge and the knowledge base of teaching. International Journal of Educational Research, 35, 441–461.

Warner, R. M. (2008). Applied statistics: From bivariate to multivariate techniques. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

Weinstein, C. S. (1989). Teacher education students’ preconceptions of teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 40, 53–60.

N. Polat / International Journal of Educational Research 49 (2010) 195–209 209

Wenden, A. (1987). How to be a successful language learner: insights and prescriptions from L2 learners. In A. Wenden & J. Rubin (Eds.), Learner strategies in

language learning (pp. 103–117). London: Prentice Hall.

Williams, D. (1983). Developing criteria for textbook evaluation. ELT Journal, 3, 251–255.

Willis, J. (1996). A framework for task-based learning. London: Longman Hierarchy.

Woods, D. (1996). Teacher cognition in language teaching: Beliefs, decision-making and classroom practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zacharias, N. T. (2005). Teachers’ beliefs about internationally-published materials: A survey of tertiary English teachers in Indonesia. RELC Journal, 36, 23–37.

Zeichner, K., & Tabachnick, B. R. (1981). Are the effects of university teacher Education washed out by the school experience? Journal of Teacher Education, 3, 7–11.

Document Outline

- Pedagogical treatment and change in preservice teacher beliefs: An experimental study

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Teacher beliefs about language teaching/learning

- Instructional materials and L2 education

- Research design

- Participants and setting

- Research questions

- Experimental and control groups and the treatment

- Measuring beliefs: instruments and procedures

- Standardization and reliability of the instrument

- Data analysis

- Results

- Quantitative

- Qualitative

- Discussion

- Implications

- Limitations and future directions

- Acknowledgements

- Questionnaires

- (Continued)

- References

- (Continued)