Preview text:

Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 18 (2003) 497–511

A web-based tunneling-induced buildingyutility damage assessment system: TURISK

Chungsik Yooa,*, Jae-Hoon Kimb Department a

of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Sungkyunkwan University, 300 Chun-Chun Dong, Jan-An Gu, Suwon,

Kyong-Gi Do 440-746, South Korea

bDepartment of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Sungkyunkwan University, 300 Chun-Chun Dong, Jan-An Gu, Suwon,

Kyong-Gi Do 440-746, South Korea

Received 1 October 2002; received in revised form 15 March 2003; accepted 15 March 2003 Abstract

Prediction of ground movements and assessment of risk of damage to adjacent buildingsyutilities have become an essential part

of the planning, design, and construction of a tunneling project in urban environments. A web-based tunneling-induced buildingy

utility damage assessment system, named TURISK, was developed. Currently available first order methods were implemented in

TURISK for prediction of tunneling-induced ground movements and assessment of damage to adjacent buildingsyutilities.

TURISK was written in a server-client internet environment using the Microsoft Visual Basic 6.0 in conjunction with the

MapGuide ActiveX Control software. The developed system was then implemented to the Daegu Metro Subway Line 2

construction site. The results demonstrated that the developed web-based buildingyutility assessment system can be used as an

efficient tool in the perspective of tunneling-induced settlement risk management for tunneling projects in urban areas. Practical

significance of tunneling-induced settlement risk assessment is also discussed.

䊚 2003 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Tunneling; Ground movement; Risk assessment; Building damage; Cast iron pipe; Internet 1. Introduction

therefore devoted to prevent the ground movements

associated with it. In this regard, prediction of ground

Due to rapid growth in urban development there has

movements and assessment of the risk of damage to

been a pressing need for construction of new tunnels

adjacent buildingsyutilities has become an essential part

for transportation systems and underground utilities.

of the planning, design and construction of a tunneling

Tunneling hasbecome an attractive alternative in creat-

project in the urban environments.

ing underground spaces for the transportation and utility

Tunnelling-induced settlement risk assessment needs

networks. An ever-increasing awareness of the environ-

to be conducted during initial design aswell asconstruc- ment hasals

o given a favor to tunneling over other

tion stages. During the initial design stage, the first-

construction alternatives. During tunneling, changes in

order simplified procedure outlined by Peck (1969) and

the state of stress in the ground mass around the tunnel

O’Reilly and New (1982) and extended by New and

and subsequent ground losses inevitably occur. These O’Reilly (1991), isus ually adopted to predict the

changes in the stress and ground losses are realized at

magnitude and extent of ground movements associated

the ground surface as a form of ground surface move-

with the proposed tunneling. The predicted magnitude

ments, which eventually impose strains onto nearby

and extent of the ground movementsare then used to

buildingsyutilities through translation, rotation, distor-

assess the potential damage to adjacent buildings and

tion and possibly damage. A substantial portion of the

utilities, again, using simplified approaches (Boscardin

cost of a tunneling project in the urban environments is

and Cording, 1987; Burland, 1995). When damage is

likely to occur, either modificationsto the initial design

or protective measures for the buildings and utilities are

*Corresponding author. Tel.: q82-31-290-7518; fax: q82-31-290- 7549.

provided. A second round of assessment is performed

E-mail address: csyoo@yurim.skku.ac.kr (C. Yoo).

during construction using measured settlement data as

0886-7798/03/$ - see front matter 䊚 2003 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/S0886-7798(03)00067-1 498

C. Yoo, J.-H. Kim / Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 18 (2003) 497–511

well asnewly obtained information, and correctionsare

In the above equations, Vs isthe volume of the

made to the initial assessment, if necessary.

settlement trough per unit distance of tunnel advance

In urban tunneling, which involvesa large number of

and i isthe inflection point defining the form and span

buildings and utilities, the previously described tunnel-

of the settlement trough on the assumption that the

ing-induced settlement risk assessment process may

semi-transverse (y-axis) settlement profile can be

require a considerable amount of computational effort

described by a normal probability equation. xi and xf

and therefore may be better suited in a computer-based

are the tunnel start point and the tunnel face position,

environment. Furthermore, the assessment process using

respectively, along the tunnel axis (ys0). G(a) can be

monitored data needsto be carried out on a real-time

determined from a standard probability table. n isthe

basis so that the decision making process regarding the

power of (zo–z) to which i isproportional and isusually

damage assessment does not hamper the tunnel construc-

assumed to be unity. Note that zo and z are the depth to

tion process. A web-based system with an efficient

tunnel center and the depth of settlement trough under

graphic-user-interface (GUI) isdes irable in order to

consideration. Respective ground strains can be obtained

effectively handle such a process. The GIS-based sys-

by taking derivativesof the above equationsasEqs .

tems such as those by Netzel and Kaalberg (1999) and (4)–(6).

Kimmance et al. (1999) were developed to facilitate the

process of construction risk management. w 2 z ynV y s y

In view of this, for better and efficient tunneling- ´ s expx | z 2

induced settlement risk assessment, a web-based tunnel- y 2i ~ y2piŽz y o z.

ing-induced buildingyutility damage assessment system S w 2 z y T y B E 1 xyx Žxyx . i

(TURISK) wasdeveloped and implemented to the i = C F x exp | U T 2

Daegu Metro Subway Line 2 construction site in Korea. D i G y 2i ~ V y2p

The developed system employs currently available first- w 2 z y B E xyx Žxyx . i

order simplified approaches for prediction of ground f C y F x exp | 2 i

movements and assessment of risk of damage to adjacent D G y 2i ~

buildingsyutilities. On-line computing concept was W 2 w z B E B E B E y xyxi xyx T f x |

employed in TURISK so that any authorized user can q y y X C F 1 C G F C G F 2 T (4) D i Gy D i G D i G~

have access to the system and perform an assessment Y

through the World Wide Web. In thispaper, the concept

and details of the system are described. An illustrative 2 B E n y ´ s y C w y1F 2 (5)

example on the field application of the developed system z y o z D i G is also presented. w 2 z y

2. Ground movements and buildingyutility damage nV y s y ´ s expx | x assessment 2 y 2i ~ y2piŽz y o z. S w 2 z

2.1. Ground movements and strains y B T E xyx Žxyx . i i U = C T F x exp | 2 D i G y 2i ~ V

In the developed system, the ground displacements w 2 W z

and associated strains for a given tunneling are calcu- y B E xyx Žxyx . i T f C y F x X exp | 2 T (6)

lated based on the procedure outlined by Peck (1969) D i G y 2i ~Y

and New and O’Reilly (1991). The vertical settlement

and horizontal displacements at any point on a deform-

It iswell known that the ground displacementsand

ing ground are calculated using Eqs. (1)–(3).

respective ground strains are significantly influenced by

the way in which the inflection point isselected. There w 2 zS B E B W E V y T xyx xyx T s i f x U | y X ws exp y

are several equations available for estimating the inflec- T C G F C G FT 2 (1) y 2i V ~ D i G D i GY y2pi

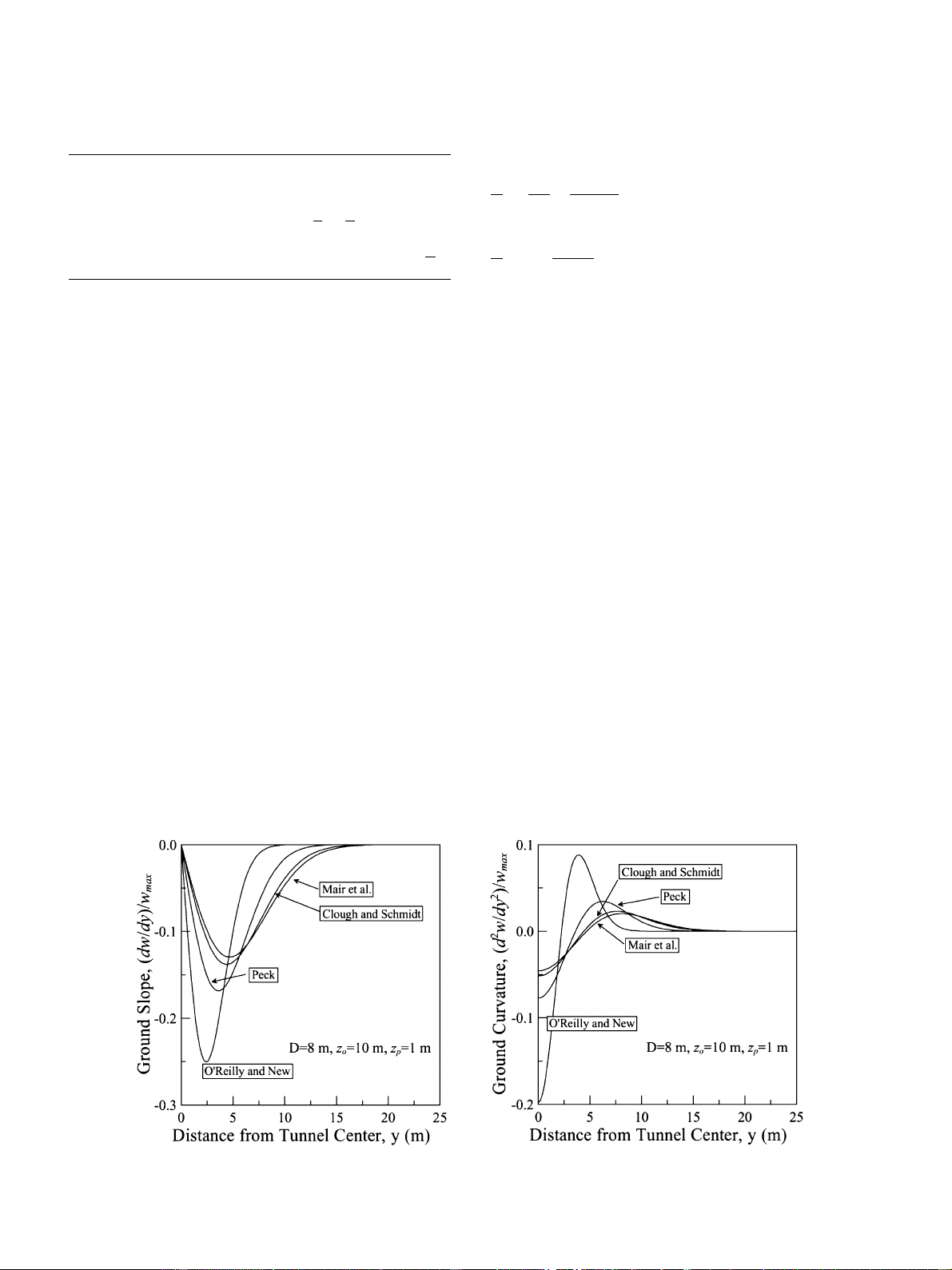

tion point astabulated in Table 1. Fig. 1 comparesthe

normalized ground slope and curvature curves generated yn vs yw (2)

using the various equations for the inflection point listed z y o z

in Table 1 for an 8-m-diameter circular tunnel. It isseen

that the normalized ground slope and curvature curves w 2 z nVs y

significantly vary with which equation is used for the us exp y x | 2 2p z y

inflection point. The equation by O’Reilly and New o z y 2i ~ Ž .

(1982) tends to yield the most conservative results S w 2 z w 2 zW y T Žxyx y . i Žxyx . f T

whereasthat by Clough and Schmidt U = x exp | (1981) the least y x X T exp |T 2 2 (3) V y 2i ~ y 2i Y ~

conservative results. An equation for the inflection point

C. Yoo, J.-H. Kim / Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 18 (2003) 497–511 499 Table 1

´d are likely to occur at the center and quarter span

Variousequationsfor inflection point points, respectively. Peck (1969)

is0.2(Dqzo) O’Reilly and New (1982) is0.43(z y o z) for clay S W D T L 3IE T is0.28(z y U s q X T ´ T b (7) o z)y0.1 for sand 0.8 D Bz L V 12t 2tLHG Y o E is C = F Clough and Schmidt (1981) 2 DDG w z B z E 2 S W D T HL G T isz x o 0.175q C 0.325 1y F| U s X 1q T ´ T d (8) Mair et al. (1993) y D zoG~ L V 18IE Y

In Eqs. (7) and (8), D isa maximum deflection of

should therefore be selected with due consideration of

the building, H isthe height of building, L isthe length local experiencess uch asworkmans hip and ground

of the building (but limited by any point of inflection

condition, among others. In TURISK, a user can either

or extent of settlement trough), E and G are, respectively,

directly select an equation for the inflection point or

Young’smodulusand shear modulusof the building, I

utilize measured settlement data, if available, to deter-

isthe second moment of inertia of the equivalent beam,

mine the location of inflection point. When using the

and t is the furthest distance from the neutral axis to the

measured data, TURISK automatically computes the

edge of the beam (i.e. Hy2 in the sagging zone and H

maximum settlement wmax and the inflection point i

in the hogging zone). For masonry structures which are

from a plot of the logarithm of the original recorded

the most damage-susceptible, the ratio of EyG isoften

settlements (log w) vs. the square of (y2) of the

taken as 2.6, which is consistent with an isotropic

transverse distance. Maximum settlement (wmax) can

Poisson’s ratio of ns0.3. A typical example of a

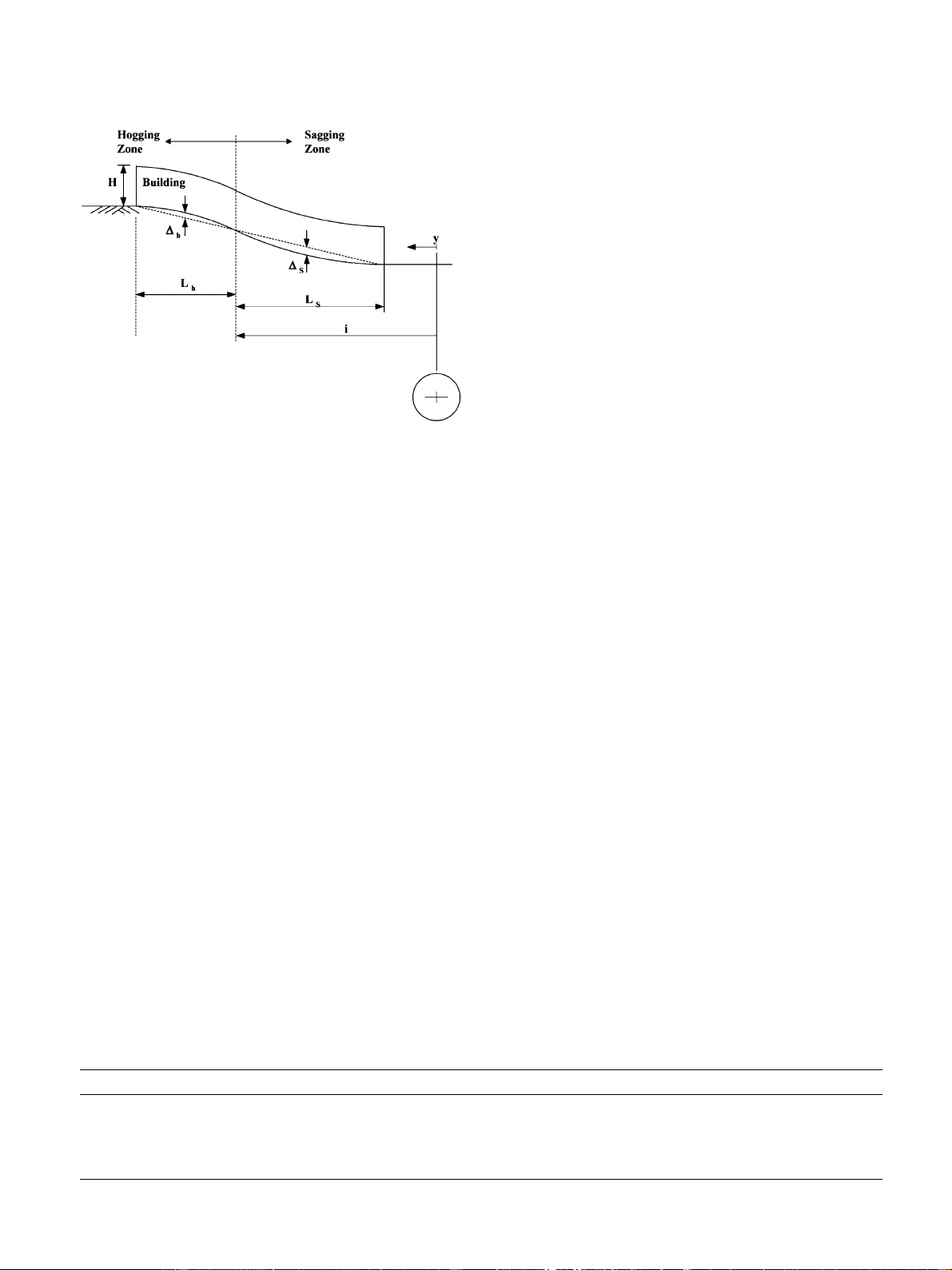

then be defined by the intercept of the regression line

building affected by a single tunnel settlement trough is

with the axis y2s0, and the value of i by the fact that shown in Fig. 2.

i2 isthe value of y2 where wyw s max 0.606.

Both transverse and longitudinal sections are evalu-

ated for possible damage. Horizontal strain (´h), which

2.2. Building damage assessment

isof particular concern in tunneling, iscalculated asthe

average horizontal strain across a section of the building

A first order building damage assessment procedure

based on the horizontal displacements across the build-

proposed by Burland (1995) wasimplemented in TUR-

ing using Eq. (2) and Eq. (3) for the transverse and

ISK, in which a building istreated asan idealized deep

longitudinal sections, respectively. The average horizon-

beam with span L and height H deforming under a

tal strain is then combined with the bending and diagonal

central point load. Bending strain (´b) and diagonal

strains obtained from Eq. (7) and Eq. (8) asEq. (9)

shear strain (´d) developed in a building subjected to

and Eq. (10) to give maximum bending strain (´bt) and

tunneling-induced ground movementsare calculated

diagonal shear strain (´dt). The potential damage isthen

using Eqs. (7) and (8), respectively. Note that ´b and

assessed using either ´bt or ´ , dt whichever isgreater.

Fig. 1. Comparison of ground slopes and curvatures using various equations of inflection point. 500

C. Yoo, J.-H. Kim / Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 18 (2003) 497–511

category particularly for brickwork or masonry is given

in Table 3, which wasfirst put forward by Burland et al. (1977).

Although the procedure implemented in TURISK is

more appropriate to brick or masonry structures, rein-

forced concrete frame structures on shallow foundations

can also be evaluated using the same methodology.

Note, however, that a lager EyG value of 12.5 isoften

used for the reinforced concrete frame structures rather

than 2.6 used for masonry structures with due consid-

eration of their flexibility in shear.

2.3. Utility damage assessment

During urban tunneling, utility pipelinesburied at

shallow depths are also subjected to a wave of ground

movements. Due to the difficulties involved in obtaining

Fig. 2. Building deformation associated with tunneling-induced

detailed information asto the condition of the pipelines ground settlement.

and jointing details, sophisticated analyses are of little

practical value at least during an initial assessment stage.

Although the ground–building interaction altersthe

In view of this, the simplified procedure proposed by

ground movement patternsat the building base level, no

Bracegirdle et al. (1996) and recently extended by Yoo

such an effect was considered. Such a simplified

(2001) were adopted in TURISK. The procedure adopt-

approach is justified here, since TURISK is developed

ed in TURISK employsthe green field ground displace-

for use in a first-order damage assessment stage. The

mentsto compute pipe strainsand joint rotationypullout

soil–structure interaction effect should be taken into

considering the worst scenario in terms of the location

consideration in a more elaborate second round of

and stiffness of pipe joints. For example, pipelines are

damage assessment for buildings and utilities evaluated

assumed to deform with the ground and no consideration

being at risk. More detailed description of the method

istaken of the actual location of jointsbetween the

adopted in TURISK isavailable elsewhere (Yoo, 2001).

individual pipes. Also assumed is that joints are located

at the most unfavorable position with no resistance ´ s

against rotation and slip. The procedure outlined below bt ´ q h ´b (9) ismore appropriate to cas t and ductile iron pipesfor

water and gas mains, which are considered to be the w 2 z0.5 2 x | ´ s dt 0.35´ q h Ž y 0.65´ q h. ´d~ (10)

most damage-susceptible. Details of the method adopted

in TURISK are given in subsequent paragraphs.

The limiting tensile strain (´lim) approach suggested

by Burland et al. (1977) wasadopted to relate computed

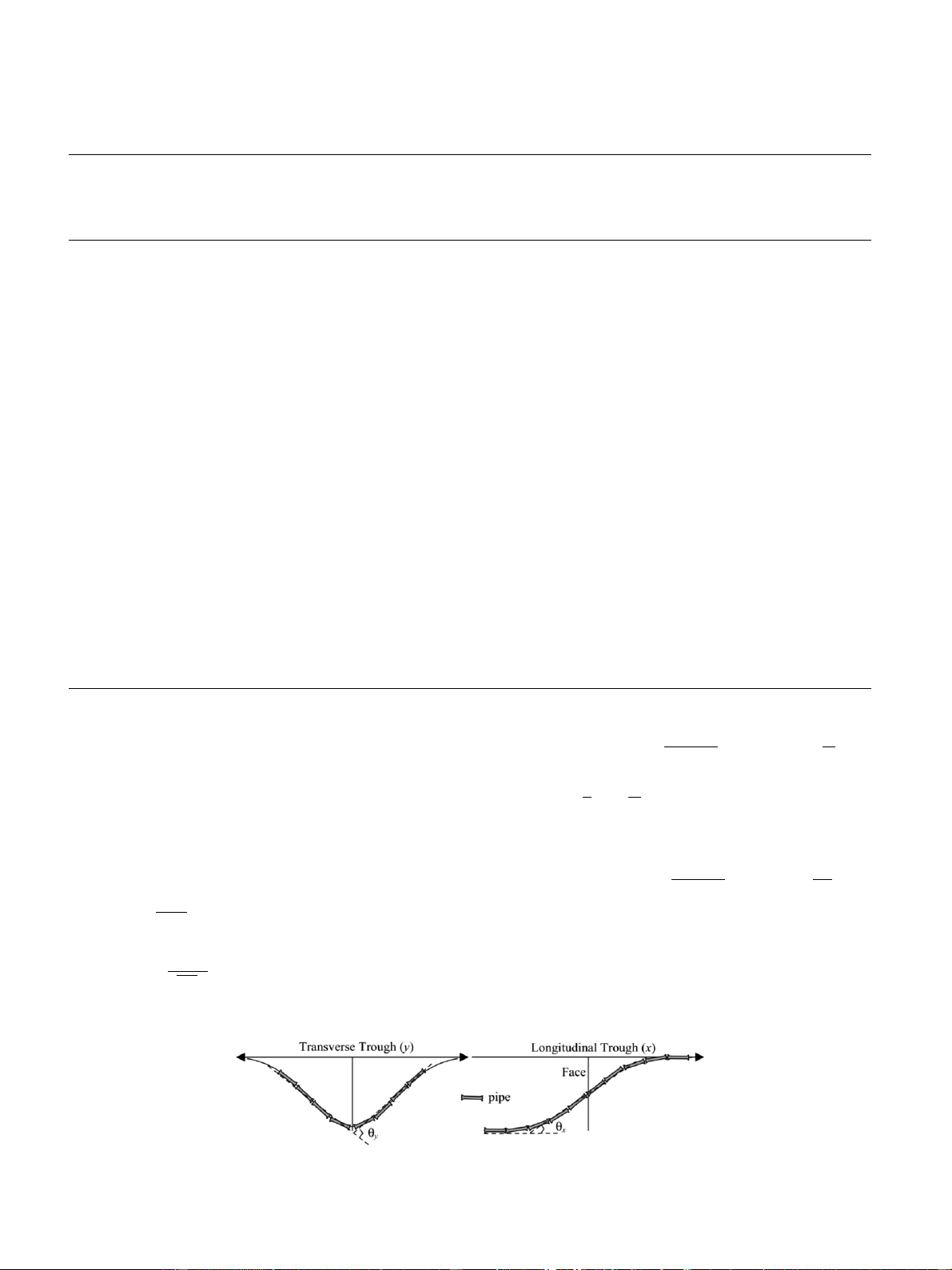

2.3.1. Joint rotation and pullout

strain to a damage level, which drew work on the

Joint rotations (ux, uy) for pipesparallel and trans-

concept of ‘critical tensile strain’, as a fundamental

verse to the tunnel axis, as illustrated in Fig. 3, can be

parameter determining the onset of cracking, proposed

computed using Eq. (11) and Eq. (12), respectively,

by Burland and Wroth (1974). The relationship between

assuming the worst conceivable configuration of joints.

the damage categoriesand the rangesof limiting tensile

Similarly, maximum potential pullouts (Rx, Ry) can be

strain in Table 2 proposed by Boscardin and Cording

approximated asthe maximum relative horizontal dis -

(1987) was used to directly relate a calculated tensile

placementsbetween two adjoining pipes, and therefore

strain to a degree of damage. The description of damage

for pipeswith an individual length (Lj), Rx and Ry can Table 2

Relationship between category of damage and limiting tensile strain (after Boscardin and Cording, 1987) Category of damage Normal degree of severity Limiting tensile strain (´ % lim ) 0 Negligible 0;0.05 1 Very slight 0.05;0.075 2 Slight 0.075;0.15 3 Moderate 0.15;0.3 4,5 Severe to very severe )0.3

C. Yoo, J.-H. Kim / Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 18 (2003) 497–511 501 Table 3 Description of damage category Category Normal Description of typical damage of degree (Ease of repair is underlined) damage of severity

Note: Crack width is only one factor in assessing category

of damage and should not be used on its own as a direct measure of it. 0 Negligible

Hairline crackslessthan approximately 0.1 mm 1 Very slight

Fine cracks which are easily treated during normal

decoration. Damage generally restricted to internal wall

finishes. Closed inspection may reveal some cracks in

external brickwork or masonry. Typical crack widths up to 1 mm 2 Slight

Crackseasily filled. re-decoration probably required.

Recurrent cracks can be masked by suitable linings.

Cracks may be visible externally and some repointing may

be required to ensure weathertightness. Doors and

windows may stick slightly. Typical crack widths up to 5 mm 3 Moderate

The cracksrequired some opening up and can be patched

by a mason. Repointing of external brickwork to be replaced.

Doorsand windowssticking. Service pipesmay fracture.

Weathertightness often impaired. Typical crack widths

are 5–15 mm or several greater than 3 mm 4 Severe

Extensive repair work involving breaking out and

replacing sectionsof wallsespecially over doorsand

windows. Windows and door frames distorted floor

sloping noticeably. Walls leaning or bulging noticeably1,

some loss of bearing in beams. Service pipes disrupted.

Typical crack widthsare 15–25 mm but also dependson the number of cracks 5 Very severe

Thisrequiresa major repair job involving partial or

complete rebuilding. Beamslose bearing, wallslean badly

and require shoring. Windows broken with distortion.

Danger of instability. Typical crack widths are greater than

25 mm but dependson the number of cracks.

be computed asEq. (13) and Eq. (14). Detailed deri- B S E B E 0.242V T s Lj

vationsof Eq. (13) and Eq. (14) are available elsewhere s y s U

Ry ZvmaxZ Zv ys ( iqL Z ) j C F 1y C 1.65 1q T F D z y o z GV D i G

(Yoo, 2001). Note that Eq. (13) and Eq. (14) for maximum pulloutswere us ed in TURISK in order to w 2z B E W 1 L T j = x X exp y C1q F |

eliminate the inherent conservatism in the approach T y 2 D i G Y ~

suggested by Bracegirdle et al. (1996) in which the (13)

maximum pulloutsare taken asthe maximum horizontal ground displacements. B S w 2 z E W 0.159V T L T s j s y s U X Rx Zu Z max Zu xs ( x q f L Z ) j C F 1yexp y x | T T 2 B E

D z yz G y 2i V V Y ~ o y s 1 u s y 2tan C F (14) 2 (11) D 2pi G

Note that Eq. (12) and Eq. (14) are for a pipeline B E V y s 1 u s

parallel to and directly above a tunnel, i.e. ys0. For a x tan 0.4 C F (12) 2 D y2pi G

pipeline parallel to but offset from the tunnel drive, i.e.

Fig. 3. Schematic view of pipe rotation. 502

C. Yoo, J.-H. Kim / Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 18 (2003) 497–511

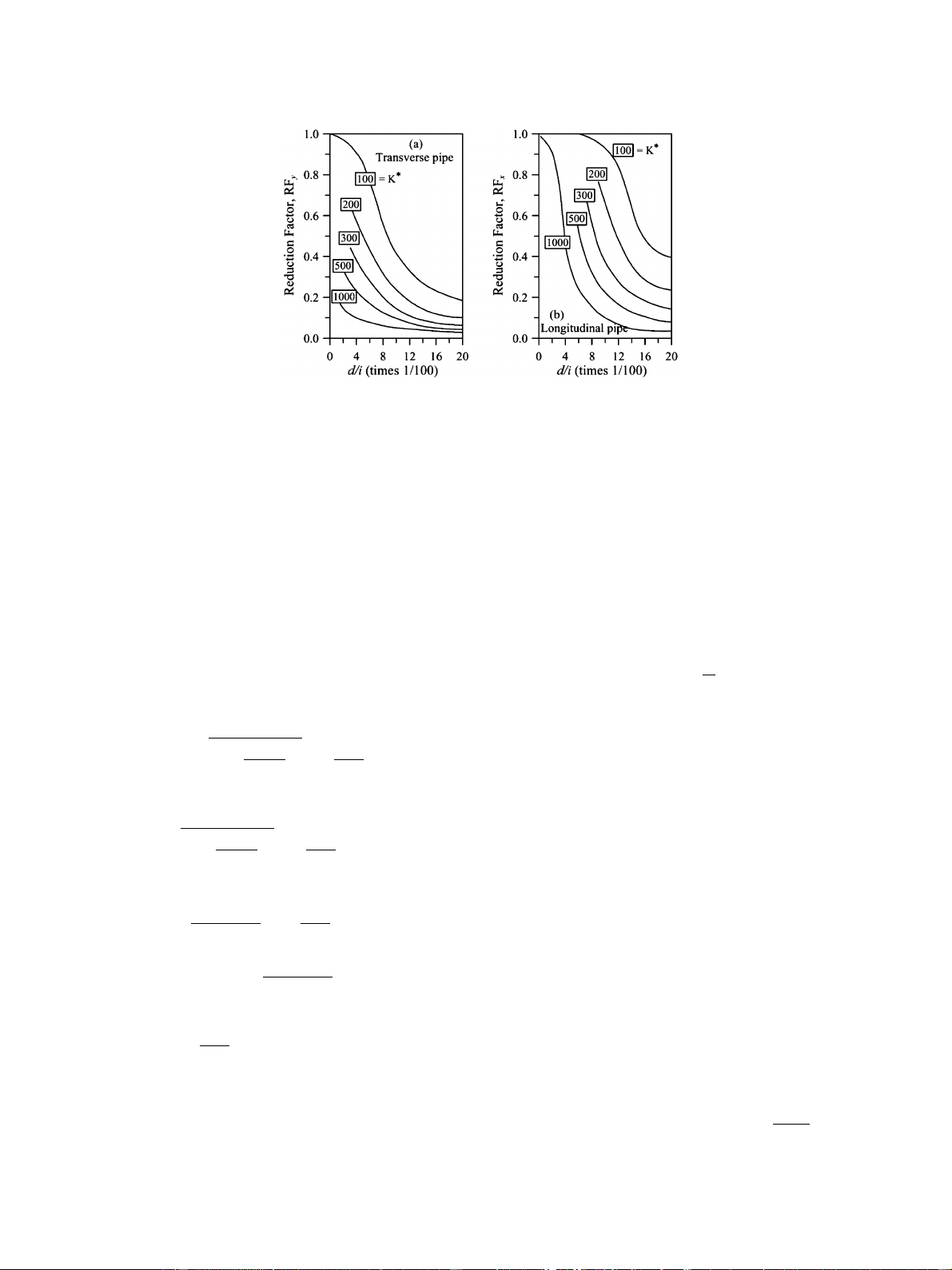

Fig. 4. Reduction factorsfor horizontal strain.

ysyp, the ground movement transverse to the pipeline 2.3.2. Pipe strains

causing longitudinal bending is the sum of vertical

Pipe strains associated with ground movements are

movement, w, and lateral movement, v, asdefined in

directly related to the ground curvature and the horizon-

Eq. (15a). The effect of offset, ysyp, thus, is to reduce

tal strain imposed on them. When assessing acceptable

the bending strain (´b) and joint rotation (ux) by the limitsfor additional s train due to tunneling-induced

factor, CF(´b, ux), given in Eq. (15b). Likewise, the

ground movements in otherwise sound pipes, some

horizontal strain (´h) and pullout (Rx) are reduced by

degree of conservatism is required accounting for pos-

the same magnitude that the longitudinal displacement

sible deterioration of the pipes due to previous ground

u isreduced, asdefined in Eqs . (16a) and (16b) as

movements and related corrosion. Under most circum-

CF(´h, Rx). Therefore, the pipe strains and rotationy

stances, the maximum tensile strains occur at locations

pullout for a pipeline parallel to but offset from the

of maximum hogging curvature and horizontal strain.

tunnel drive can be easily computed by applying the

For pipes transverse to the tunnel drive, this location

correction factorsto those for a pipeline directly above occursat a dis tance of y y

s 3i from the center of the the tunnel.

trough, while at xsx " f

i for pipesparallel to the line

of tunnel. The expression for ground strain, more cor- 2 w 2 z B E y y

rectly differential ground movement, may be conserva- p yp © © 8 wqv s 1 p C q F expx w | Ž .ysy max 2 y

tively equated with the effect on a buried pipeline by

D z yz G y 2i ~ o p

assuming zero pipe stiffness, but for all practical cases sCFŽ´ , b u . x wmax (15a)

pipe stiffness and slip at the soil–pipe interface can

greatly reduce the strain in the pipeline. In jointed 2 w 2 z B E y y p yp

pipelines, the axial forces that can develop are severely CF ´ , b u s x 1 C q F expx | Ž . 2 (15b)

y Dz yz G y 2i ~

limited by the very small forces that can be transferred o p at the pipe jointsand thes e jointsthen accommodate w 2 z

most of the differential ground movement (Attewell et y w 2 z Žxyx . f yyp u su x exp |expx |

al., 1986). In view of this, Attewell et al. (1986) ysyp max 2 2 y 2i ~ y 2i ~

suggested that reduction factors shown in Fig. 4, which w 2 z yŽxyx .

wasoriginally developed by Poulosand Davis(1980) f sCF x | (´ , h R ) x umaxexp

for piles subjected longitudinal movements, be used 2 (16a) y 2i ~

when estimating the horizontal pipe strains (´ay, ´ax).

The maximum tensile strains for rigidly jointed pipelines w 2 z yyp

transverse and parallel to the tunnel drive, respectively, CF(´ ,R )sexpx | h x 2 (16b) y 2i ~

can therefore be computed using Eqs. (17a), (17b) and

(17c) and Eqs. (18a), (18b) and (18c). The reduction

The potential for damage isevaluated using the allow-

factors are computed according to the relative stiffness

able limits for rotation and pullout suggested by Attewell E R

between the pipe and the soil as P A * K s where E

et al. (1986) in Table 4. The limitsvary with joint type p Eg

and condition prior to tunneling asshown in Table 4. and E , g

are the elastic moduli of pipe and soil and RA

C. Yoo, J.-H. Kim / Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 18 (2003) 497–511 503 A

performance on the likelihood of damage to adjacent isthe pipe area ratio p

in which Ap and rp are the 2 pr

buildingsyutilitiesso that modificationsto the proposed p

pipe sectional area and radius, respectively.

tunneling scheme can be made based on the parametric

study. Details of TURISK are described in subsequent ● Transverse pipe. paragraphs. ´ s 3.2. System structure ty ´ q by ´ay (17a) TURISK waswritten in a s erver-client environment 2 B E d d w V d s ´ s

using the Microsoft Visual Basic 6.0. Simple but robust by C Fs0.089 2 3 (17b) 2 D dy G i

GUI was developed focusing on user-friendliness. The

MapGuide ActiveX Control software was used to allow B E dv 0.178Vs

for TURISK to be used in a web-based environment. ´ s ay RF C y FmaxsRFy (17c) D dy G

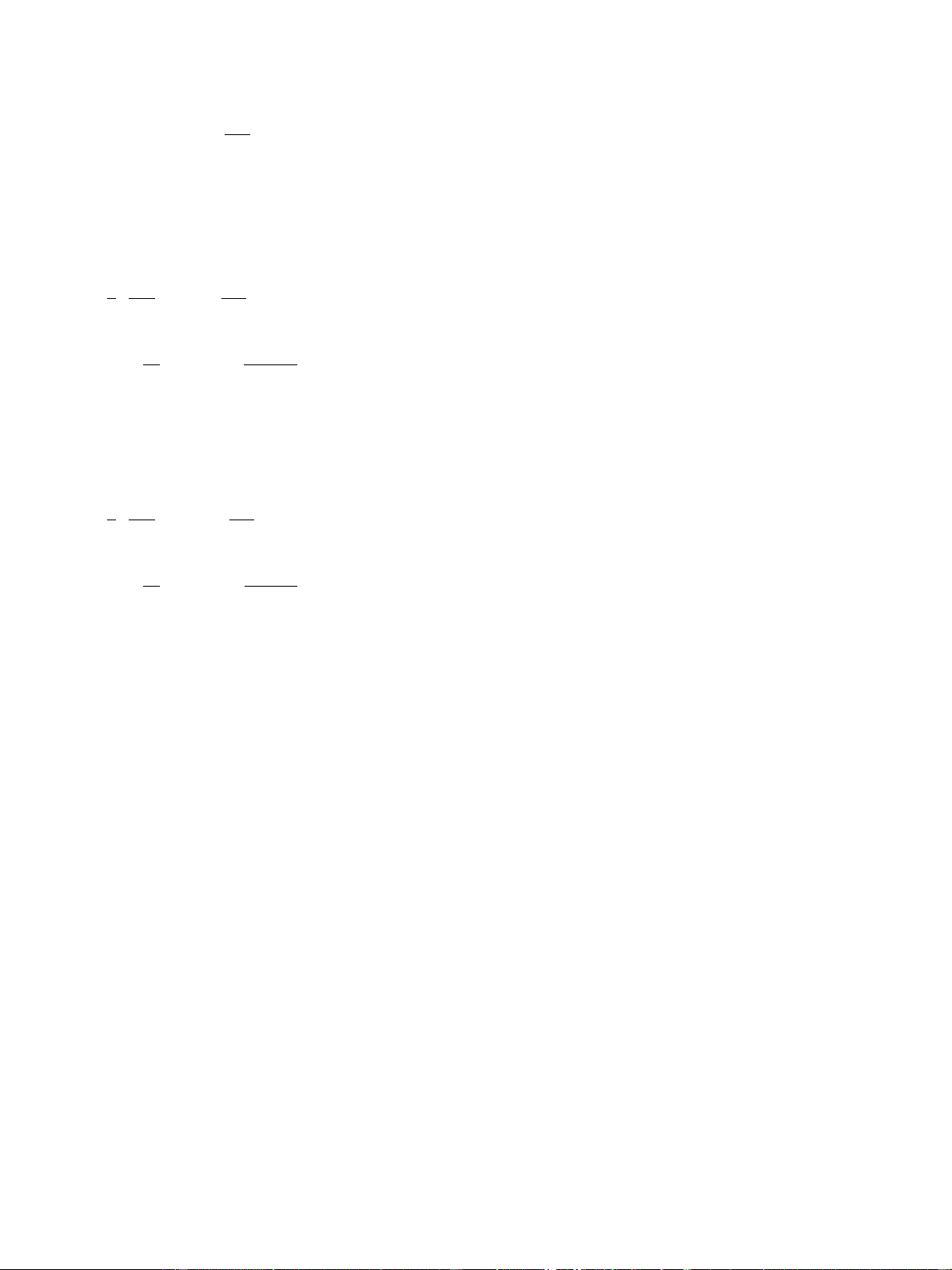

Fig. 5 shows an overview of TURISK. Žz y o z.i

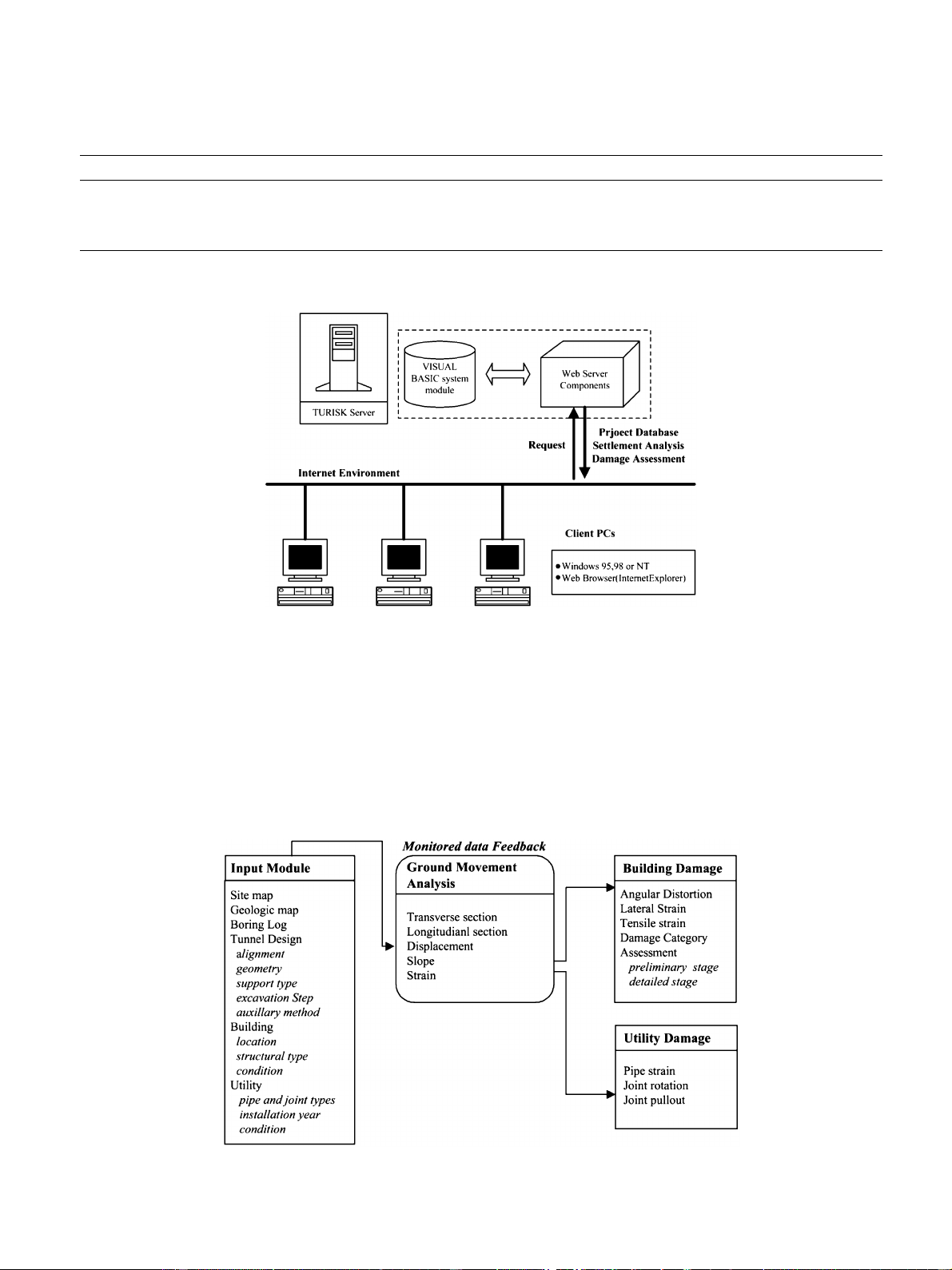

TURISK consists of three modules: (1) input module;

(2) ground movement analysis module; and (3) damage ● Longitudinal pipe.

assessment module. Each module can function indepen-

dently, but isfully interfaced with other modules. The ´ s tx ´ q bx ´ax (18a)

basic system structure is given in Fig. 6. 2 B E d d w V d 3.2.1. Input module s ´ s by C Fs0.0979 2 3 (18b) 2

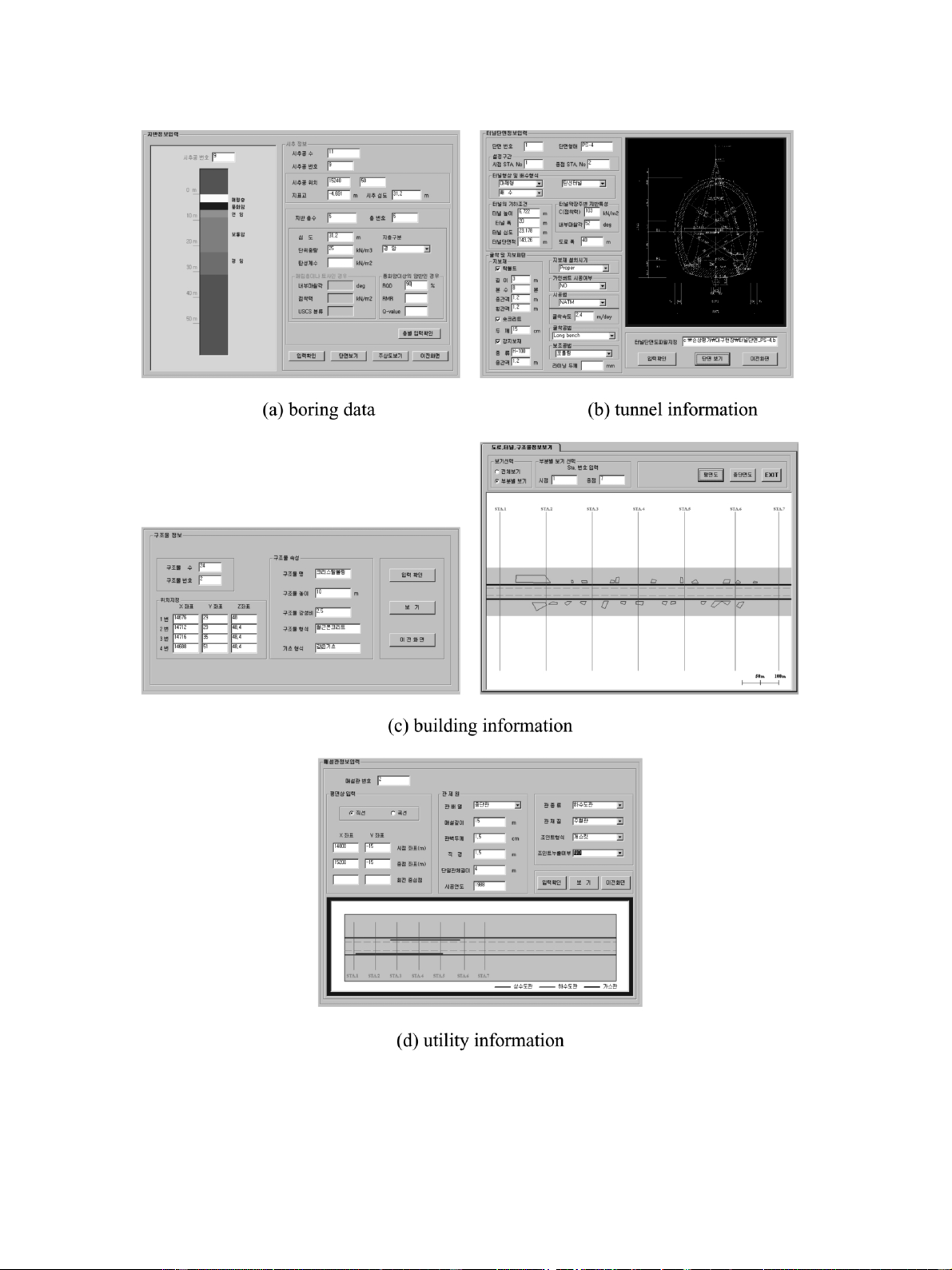

In the input module, an authorized user can input D dx G i

construction-related information for a given project

through user-friendly window-based GUI. The required B E dv 0.097Vs ´ s input itemsinclude s ite map, tunnel alignment and ax RF C x FmaxsRFx (18c) D dx G Žz y o z.i

design drawings, geological map, boring information,

buildingsyutilitiesinformation, etc. and therefore the

Allowable limits for strain increase shown in Table 5

module itself can be severed as a database for a

can be used to evaluate the potential for damage. It

particular tunneling project. Considering the nature of a

should, however, be noted that these limits are somewhat

tunneling project, inputsfor all information are made

conservative in nature as noted by Bracegirdle et al.

on a station basis, and are utilized later in computing (1996).

the magnitude and distribution of ground movements

and associated buildingsyutilitiesdamage levels. Exam- 3. TURISK development

plesof variouswindowsavailable in the input module are shown in Fig. 7. 3.1. Overview

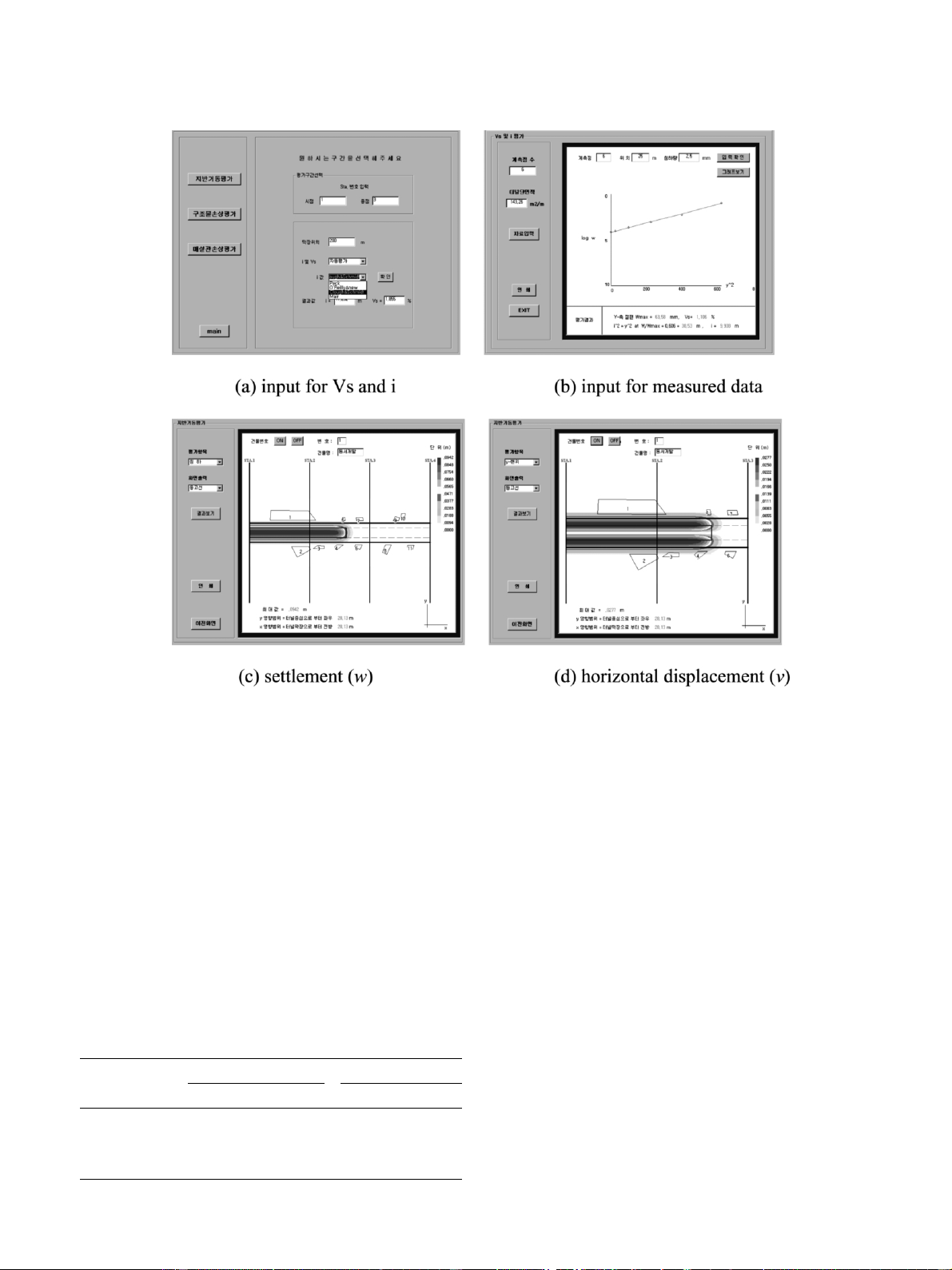

3.2.2. Ground movement analysis module

The process of settlement risk assessment associated

The magnitude and extent of ground movementsfor

with tunneling isrepetitive and computationally inten-

a given site are computed in this module using the

sive in nature, as mentioned previously. This type of equationspres

ented earlier in thispaper. The volume

process can therefore be more efficiently performed in

loss Vs and the inflection point i are the required input

a computer-based environment. In view of this, a web-

parameters. A user can specify a route to be analyzed

based tunneling-induced buildingyutility damage assess-

in terms of station numbers. Note that monitored trans-

ment system, TURISK, was developed.

verse settlement data, if available, can be fed back into

TURISK iscapable of predicting the magnitude and

the system so that the volume of settlement trough and

extent of ground movementsand anticipated degree of

the inflection point can be back-calculated and used in

damage to adjacent buildingsyutilitiesfor a given tun-

a subsequent analysis. A number of information can be

neling site. A web-based on-line computing concept is

extracted from the ground movement analysis module

employed to take advantage of the revolutionary internet

such as contour plots of ground displacements, slopes

technology, and therefore the system can be accessed

and strains, and transverse as well as longitudinal dis-

from anywhere through the World Wide Web. TURISK

placement profiles. Each contour plot is overlaid on a

allowsan authorized user to create a new project or to

plan drawing of tunnel alignment with buildingsand

modify any information of an existing project. The

utilitiesin place so that the likely magnitude and extent

surplusvalue of TURISK isthe ability to carry out a

of ground movementsto which buildingsyutilitiesare

parametric study with regard to the effect of tunneling

subjected can be visually identified. A parametric study 504

C. Yoo, J.-H. Kim / Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 18 (2003) 497–511 Table 4

Allowable limitsfor rotation and pullout (after Attewell et al., 1986) Joint type Rotation, u (degree) Pull-out, R (mm)

Lead-yarn joint in gasmain with history of leak None None

Lead-yarn joint in sound gas main 1.0 10

Lead-yarn joint in water mains1.5 15

Rubber gasket joint in gas or water mains 2.5 25

Fig. 5. TURISK system overview.

can be performed on the effect of tunneling performance

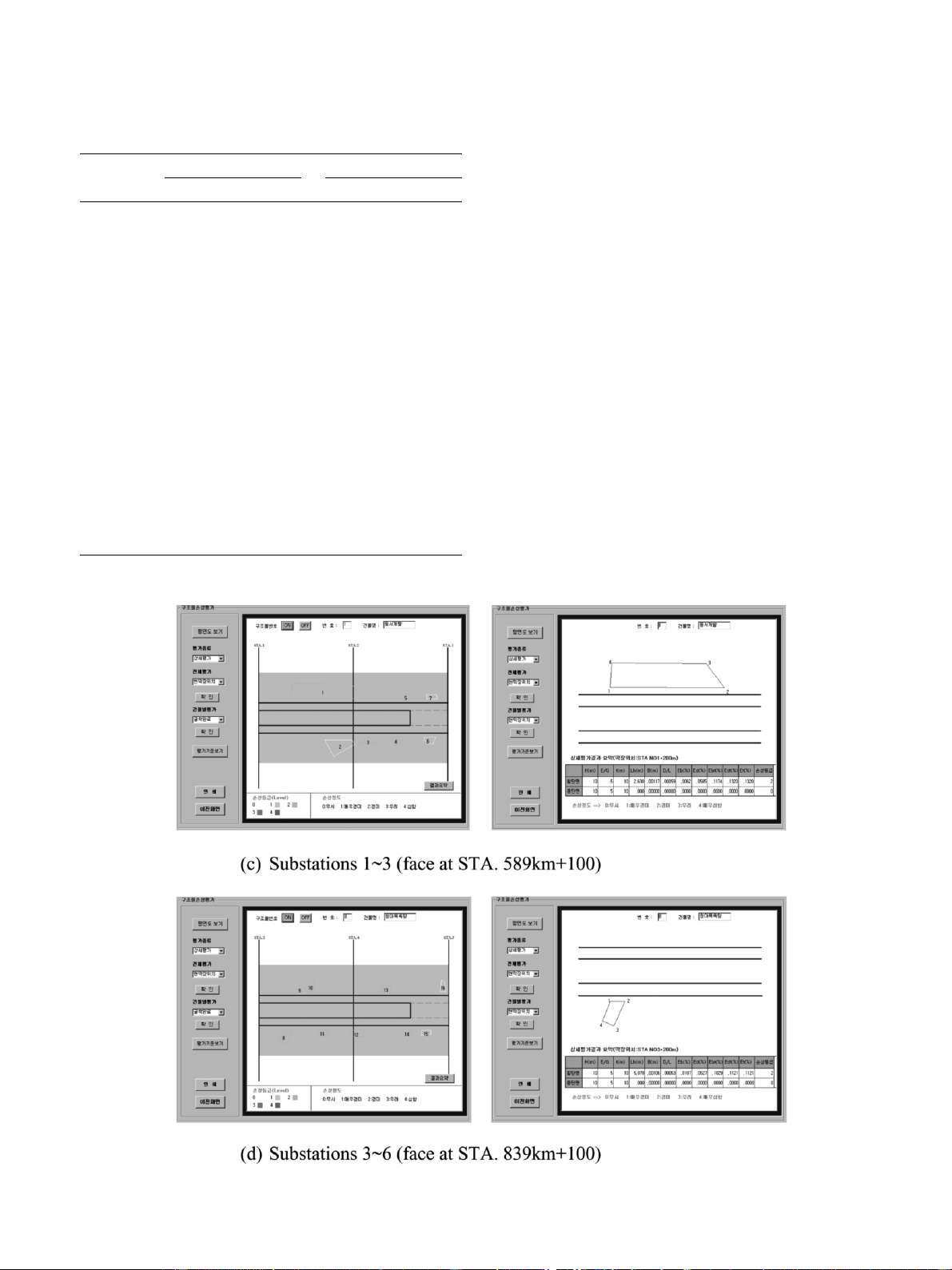

3.2.3. Buildingyutility damage assessment module

on the ground movementsby varying the input values

The buildingyutility damage assessment module com-

for Vs and i. Fig. 8 illustrates typical example windows

putes the maximum tensile strains for buildingsyutilities

of outputsavailable in the ground movement analys is

located within a route specified by a user. The bending, module.

diagonal shear, and horizontal strains are calculated by

Fig. 6. System structure of TURISK (a) boring data; (b) tunnel information; (c) building information; (d) utility information.

C. Yoo, J.-H. Kim / Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 18 (2003) 497–511 505

Fig. 7. Input module (a) input for Vs and i; (b) input for measured data; (c) settlement (w); (d) horizontal displacement (v).

projecting the predicted ground movementsat the loca-

category in accordance with the relationship in Table 2.

tion of each building and utility line. The calculated

Similarly, the pipe strains and joint rotationsypullouts

maximum tensile strain is then related to the damage

are calculated and compared with the acceptable limits 506

C. Yoo, J.-H. Kim / Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 18 (2003) 497–511

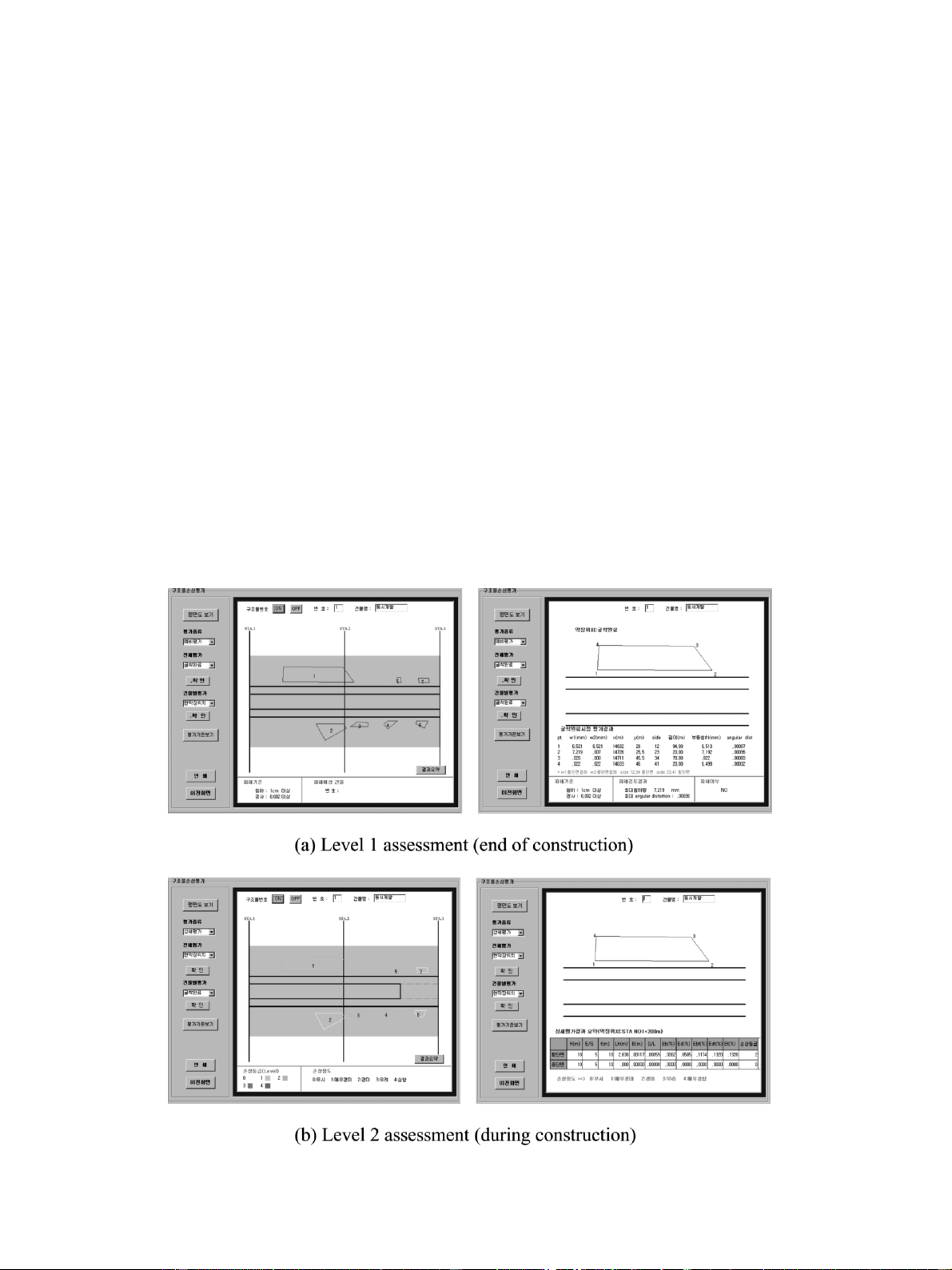

Fig. 8. Ground movement analysis module (a) Level 1 assessment (end of construction); (b) Level 2 assessment (during construction).

in Table 5. The results of damage assessment are

are further tested in the more elaborate Level 2 assess-

graphically presented in a manner that buildingsyutilities

ment for possible damage based on the procedures

can be identified with different colorsaccording to

outlined earlier. This allows a screening process, which anticipated damage levels.

eliminates any unnecessary data processing. Fig. 9

The assessment method employs a two-stage process

shows typical examples of the results of Level 1 and 2

(Level 1 and 2 assessments) in which buildingsare assessments.

eliminated from further stage, depending on the potential

degree of damage predicted. Note that a simple criterion

4. Implementation of TURISK

is used in the Level 1 assessment based on the allowable

limits of maximum ground settlement and slope, 10 mm

The developed system, TURISK, was implemented to

and 1y500, respectively. Only those buildingsyutilities

the Daegu Metro Subway Line 2 construction site in

subjected to settlement and slope greater than the limits

Korea, and tested for its applicability. Table 5 4.1. Site information

Allowable increase in strain (after Bracegirdle et al., 1996)

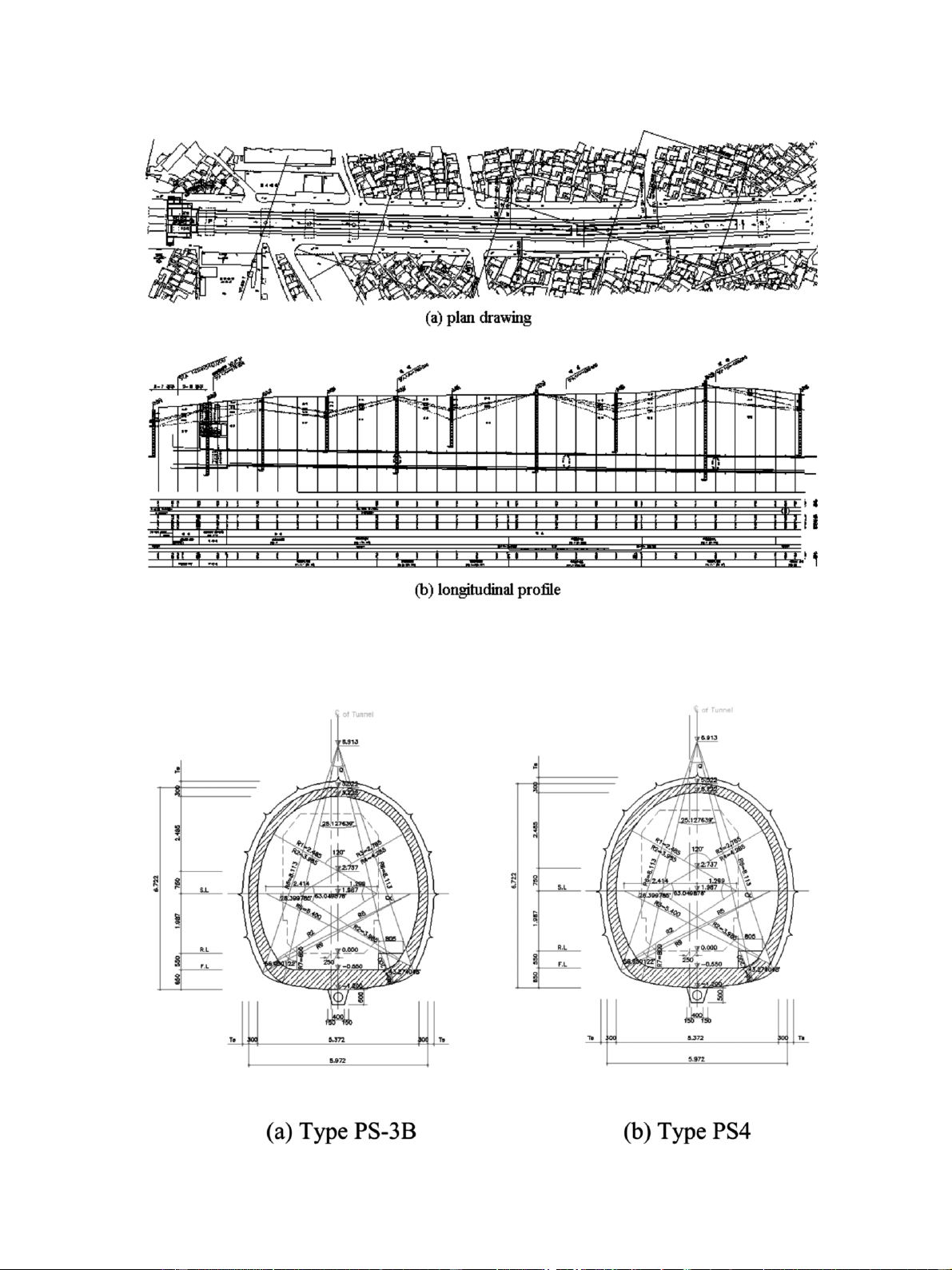

The test site consists of 1.2-km-long twin tunnels Material Design strain (m´) Allowable strain (m´)

constructed under heavily populated area as seen in Fig. Tensile Compressive Tensile Compressive

10a. North and south bound tunnels with a diameter Pit cast grey iron 370 1550 100 1200

(D) of 6.7 m were constructed approximately 1.0 D Spun cast grey 430;490 1770;2040

apart by the conventional drill and blasting method. The iron

ground at the site consists of 2.5 to 6.0 m of miscella- Ductile iron 820 1020 500 700

neous fill material including sand, gravel, and silty clay.

C. Yoo, J.-H. Kim / Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 18 (2003) 497–511 507

Underlying the fill layer isa 0 to 10-m-thick weathered

4.2. Predicted ground movements

zone followed by a sedimentary rock layer of shale or

Asmentioned earlier, the prediction of ground move-

sandstone having a uniaxial strength of in-tack rock

mentsrequiresthe volume of settlement trough Vs and

ranging 500;1000 MPa. The rock layer ischaracterized

the inflection point i. Local experiencesin s imilar

by a persistent bedding dipping 10;308SE with a

tunneling conditionsindicated that the ground s urface

number of non-persistent joints. The tunnels were

volume losses in the range of 1.0;1.8% with the

designed to be excavated in the sedimentary rock layer

inflection point ranging 9–11 m from the tunnel center-

with a cover depth of 19;25 m ass een in Fig. 10b

line. These values were then used to form an upper and

showing the longitudinal alignment profile. The tunnel

lower bounds in estimating the ground movements.

alignment followsmore or lessthe main street. Typical

Considering the varying tunnel cover depths along the

twin-tunnel sections are shown in Fig. 11.

tunnel alignment, the entire route wasdivided into

A number of old and new buildings exist alongside

substations according to tunnel cover depth. For each

the street. Note that only the buildings located within

substation, an average cover depth was used to compute

the zone of influence, i.e. up to 4.0 D away from the

the ground displacements. Presented in Table 6 are the

tunnel centerline, were selectively considered in the

estimated maximum ground displacements and slopes

system during the input process. A total of 52 buildings

for the upper and lower boundsof the surface volume

fell within the zone of influence. The required infor-

loss for the entire route. Note that x and y-directions

mation for the buildingswere obtained from alignment

correspond to parallel and transverse directions, respec-

mapping and general site reconnaissance. The site recon- tively, to the tunnel drive.

naissance indicated that no utility lines are in close

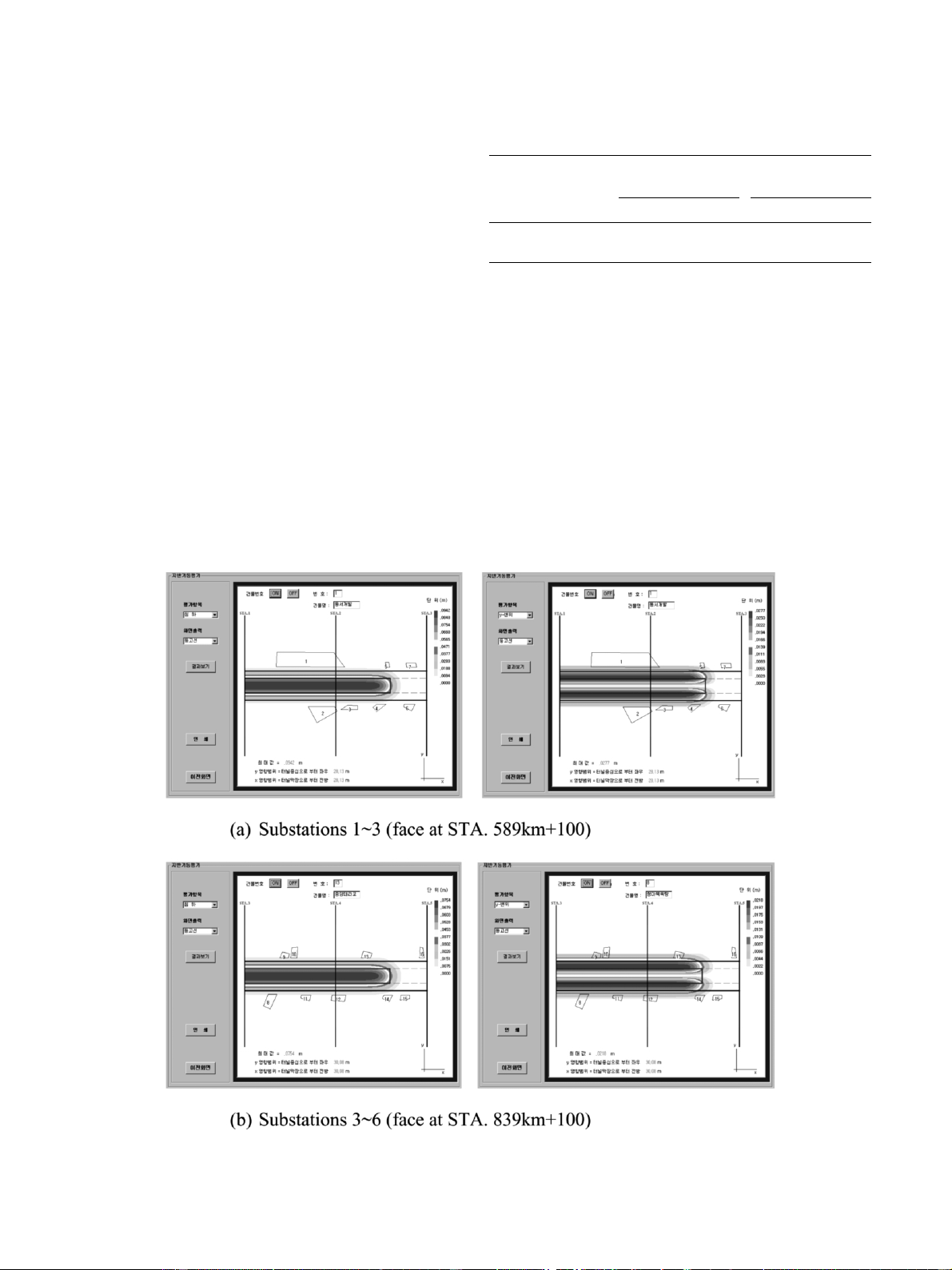

Presented in Fig. 12 are the contour plots of ground

proximity to the proposed tunnel alignment.sv671«s12)

displacements and slopes for a 350-m-long route with

Fig. 9. Damage assessment module (a) plan drawing; (b) longitudinal profile. 508

C. Yoo, J.-H. Kim / Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 18 (2003) 497–511

Fig. 10. Plan and longitudinal viewsof site (a) Type PS-3B; (b) Type PS4.

Fig. 11. Typical twin-tunnel sections (a) substations 1–3 (face at STA. 589 kmq100) Substations 3–6 (face at STA. 839 kmq100).

C. Yoo, J.-H. Kim / Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 18 (2003) 497–511 509 Table 6

the tunnel face at two different locations, i.e. STA.14

Results of ground movement analysis

km 589.050q100 and STA.14 km 839.050q100. As

noted, due to relatively large setbacks of the buildings, Vs Max surface Max horizontal Max the ground movementss eemed to only influence a

(%) settlement (mm) displacement (mm) slope

limited number of buildingsin clos e proximity to the

x-direction y-direction x-direction y-direction

edge of the street. With the help of window-based GUI, 1.0 25 5 7 1y1250 1y750

the buildings subjected to significant ground movements 1.8 36 9 13 1y650 1y430

can be easily identified. A parametric study on the

surface volume loss indicated that a volume loss of V s s

1.5% would yield satisfactory tunneling performance in

termsof damage to adjacent buildings . Thisvalue of

In the Level 2 damage assessment, the location of V s

tunnel face was varied to search the worst possible s 1.5% wass

trictly enforced during tunneling asa

controlling parameter of tunneling performance.

damage that might have been sustained by the buildings

during tunneling. Note that for each building tensile

4.3. Buildingyutility damage assessment

strains for all sidewalls were calculated and the maxi-

mum tensile strain was then related to the damage

Level 1 assessment indicated that only 24 buildings

category. The results of damage assessment for the

were expected to experience some degree of damage

buildings are summarized in Table 7. As seen, most of

according to the ground slope and settlement criteria.

the buildingsfell in the damage category 2 ‘s light’

Asmentioned, only the buildingsthat did not passthe

except two buildings, which exhibited the damage cat-

Level 1 assessment were further tested for potential

egory 3 ‘moderate’. Thiswasnot unexpected res ult damage in Level 2 assessment. s

ince the buildingsand utility linesare well s et back

Fig. 12. Contour plotsof settlement and y-direction horizontal displacement (c) substations 1–3 (face at STA. 589 kmq100) (d) substations 3– 6 (face at STA. 839 kmq100). 510

C. Yoo, J.-H. Kim / Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 18 (2003) 497–511 Table 7

from the tunnel alignment due to the relatively wide

Results of building damage assessment

street. The buildings categorized ‘slight’ and ‘moderate’ Building no. Max tensile strain (%) Damage category

were closely monitored during tunneling, and extra care

was taken to limit the ground surface volume loss V Transverse Longitudinal Transverse Longitudinal s

under 1.5%. No seriousdamageswere reported. Fig. 13 1 0.132 0.008 2 0

illustrates the results from the damage assessment 2 0.000 0.005 0 0 3 0.119 0.013 2 0 module. 4 0.131 0.016 2 0 5 0.139 0.014 2 0 6 0.132 0.016 2 0 5. Conclusions 7 0.136 0.017 2 0 8 0.137 0.014 2 0

A web-based tunneling-induced buildingyutility dam- 9 0.140 0.018 2 0 10 0.137 0.015 2 0

age assessment system (TURISK) wasdeveloped in this 11 0.127 0.015 2 0

study. The developed system employs the first-order- 12 0.124 0.010 2 0

simplified approaches for prediction of ground move- 13 0.137 0.014 2 0 14 0.127 0.015 2 0

ments and assessment of damage to adjacent buildings 15 0.127 0.015 2 0

and utilities. On-line computing concept was introduced 16 0.136 0.014 2 0

in TURISK so that any authorized user can have access 17 0.147 0.014 2 0 18 0.127 0.015 2 0

to the system and perform an assessment through the 19 0.137 0.012 2 0 World Wide Web. 20 0.146 0.015 2 0

The developed system, TURISK, was implemented 21 0.156 0.018 3 0 22 0.161 0.015 3 0

and tested for its applicability during construction of the 23 0.119 0.007 2 0

Daegu Metro Subway Line 2 in Korea. Through the 24 0.142 0.014 2 0

course of TURISK implementation, the system has been

Fig. 13. Level 2 damage assessment.

C. Yoo, J.-H. Kim / Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 18 (2003) 497–511 511

proven to be effective not only in predicting ground

Boscardin, M.D., Cording, E.G., 1987. Building response to excava-

movements and possible damage levels that might be

tion-induced settlement. J. Geotech. Eng. ASCE 115 (1), 1–21.

Burland, M.D., Wroth, C.P., 1974. Settlement of buildingsand

sustained by the adjacent buildingsyutilitiesbut also in

associated damage. SOA Review, Conference on the Settlement of

performing a parametric study to determine limiting

Structures. Pentech Press, Cambridge, London, pp. 611–654.

values of volume loss to avoid excessive damage to

Burland, J.B. et al., 1977. Behavior of foundation and structures’ nearby buildingsyutilitiesfor a given tunneling

SOA Report, Session 2, Proceedings of the 9th International environment.

Conference SMFE, Tokyo, vol. 2, pp. 495–546.

Considering the inherent conservatism of the methods

Burland, J.B., 1995. Assessment of risk of damage to buildings due

to tunneling and excavations, Invited Special Lecture to IS-Tokyo

employed in TURISK, it isimportant to perform more

1995: 1st International Conference on Earthquake Geotechnical

rigorous analyses taking the possible soil–structure Engineering.

interaction into consideration for buildings classified as

Clough, G.W., Schmidt, B., 1981. Design and performance of exca-

being at risk of category 3 damage (moderate) or greater.

vations and tunnels in soft clay. In soft Clay Engineering. Elsevier,

Similarly, a second round of more elaborate analyses pp. 569–634.

incorporating soil–pipe interaction must be employed

Kimmance, J.P., et al., 1999. Geographical information system (GIS)

application to construction and geotechnical data management on

for pipelines classified as being damaged. Nevertheless,

MRT construction projects in Singapore. Tunnel. Underground

TURISK described in this paper can be effectively used Space Technol. 14, 469–479.

as an efficient tool in a decision making process within

Mair, R.J., et al., 1993. Subsurface settlement profiles above tunnels

the framework of risk management during tunneling.

in clays. Geotechnique 43 (2), 315–320.

Netzel, H., Kaalberg, F.J., 1999 Settlement Risk Management with

GIS for the Amsterdam NorthySouth Metroline, Proceedingsof the Acknowledgments

World Tunnel Congress 1999. Oslo, pp. 129–136.

New, B.M., O’Reilly, M.P. (1991), Tunneling induced ground move-

This research was supported by KOLON Engineering

ments: predicting their magnitude and effect, 4th International

& Construction Co. and Ltd. and by SAFE (SAFEty

Conference on Ground Movementsand Structures. Cardiff.

and Structural Integrity Research Center) at Sungkyunk-

O’Reilly, M.P., New, B.M. (1982), ‘Settlementsabove tunnelsin the

wan University. The financial support is gratefully

United Kingdom—their magnitude and prediction’. Proceedingsof

Tunneling 1982, Institute of Mining Metallurgy, London, pp.173– acknowledged. 188.

Peck, R.B., 1969, Deep excavationsand tunneling in s oft ground, References

State of the Art Report, Proceedingsof the 7th International

Conference on SMFE, Mexico City, State of the Art Volume, pp.

Attewell, P.B., et al., 1986. Soil MovementsInduced by Tunneling 225–290.

and their Effectson Pipelinesand Structures. Blackie, New York.

Poulos, H.G., Davis, E.H., 1980. Pile Foundation Analysis and

Bracegirdle, A., Mair, R.J., Nyren R.J., Taylor, R.N., 1996. A

Design. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

methodology for evaluating potential damage to cast iron pipes

Yoo, C.S., 2001. Damage assessment of buried pipelines due to

induced by tunneling, Proceedingson the Geotechnical Aspectsof

tunneling-induced ground movements. J. Korean Geotech. Soc. 17

Underground Construction in Soft Ground, London, pp. 659–664. (4), 71–86.

Document Outline

- A web-based tunneling-induced building/utility damage assessment system: TURISK

- Introduction

- Ground movements and building/utility damage assessment

- Ground movements and strains

- Building damage assessment

- Utility damage assessment

- Joint rotation and pullout

- Pipe strains

- · Transverse pipe

- · Longitudinal pipe

- TURISK development

- Overview

- System structure

- Input module

- Ground movement analysis module

- Building/utility damage assessment module

- Implementation of TURISK

- Site information

- Predicted ground movements

- Building/utility damage assessment

- Conclusions

- Acknowledgements

- References