Preview text:

lOMoAR cPSD| 45734214 JUSTICE MINISTRY HANOI LAW UNIVERSITY GROUP ASSIGNMENT

PUBLIC INTERNATIONAL LAW

Topic: Analyze the modes of legal acquisition of

territory in international law. Refer to the

practice of some states

L Ớ P: N02-TL04 NHÓM: 03 lOMoAR cPSD| 45734214

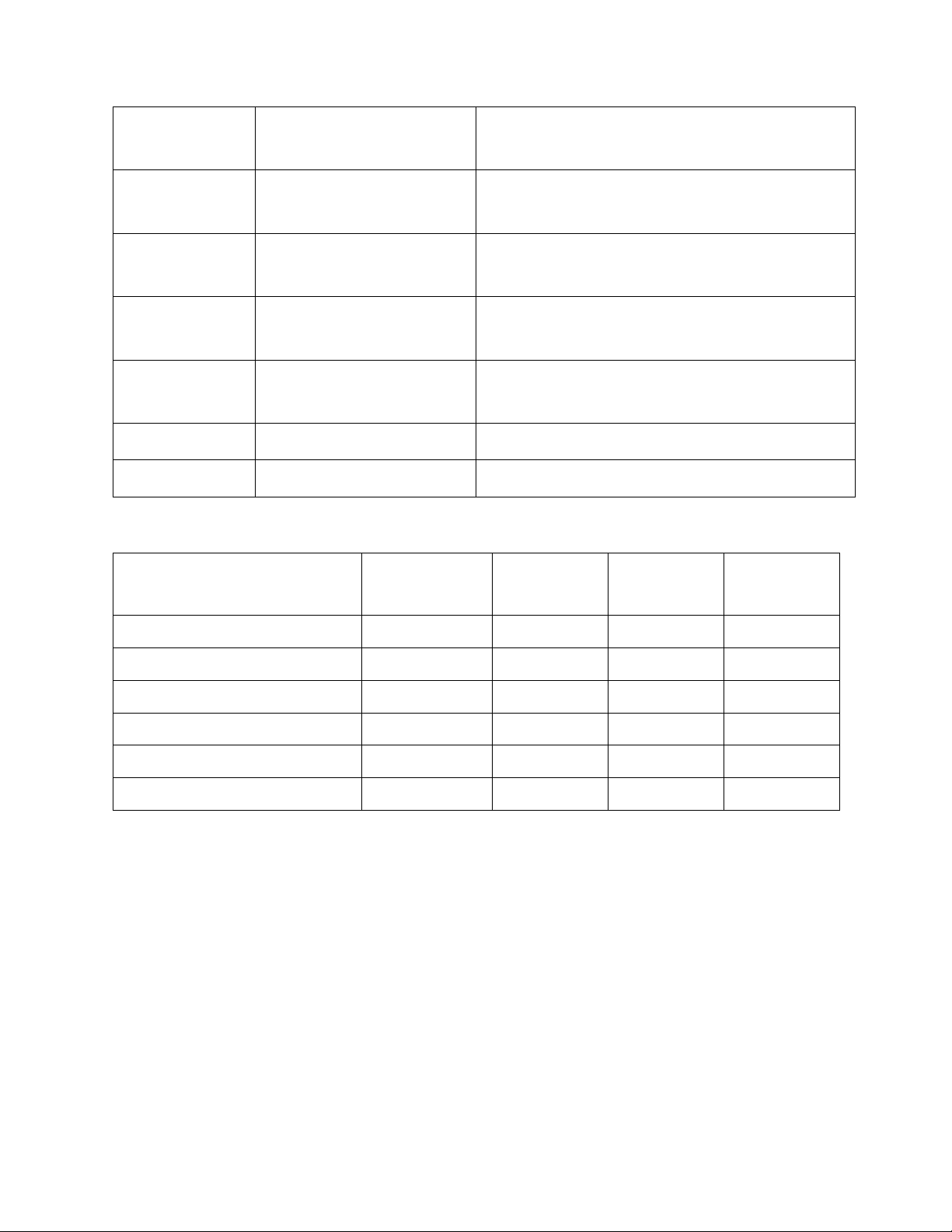

TEAMWORK QUALITY ASSESSMENT TABLE 1. Work assignment table Student’s number Members Task 463037 Nguyễn Bảo Trang

Word + The modes of legal acquisition of Leader

territory in International Law 463034 Phạm Đỗ Minh Quân International Practices on Territorial Acquisition 463035 Đỗ Thị Thanh Tâm

The modes of legal acquisition of territory in International Law 463039 Nguyễn Thị Kim Vân

International Practices on Territorial Acquisition 463040 Hoàng Hà Vy Overview 463041 Trần Châu Anh

Powerpoint + Conclusion + Introduction

2. Evaluation of teamwork results Participating Article Submission Members attitude quality time Rating Nguyễn Bảo Trang Positive Good On time A Phạm Đỗ Minh Quân Positive Good On time A Đỗ Thị Thanh Tâm Positive Good On time A Nguyễn Thị Kim Vân Positive Good On time A Hoàng Hà Vy Positive Good On time A Trần Châu Anh Positive Good On time A TABLE OF CONTENT

INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 3

CONTENT ............................................................................................................. 4

I. Overview ............................................................................................................ 4

1. National territory ................................................................................................ 4

2. Legal acquisition of territory .............................................................................. 5

II. The modes of legal acquisition of territory in International Law .............. 5 lOMoAR cPSD| 45734214

1. Occupation .......................................................................................................... 5

2. Accretion ............................................................................................................. 5

3. Cession ................................................................................................................ 6

4. Conquest ............................................................................................................. 7

5. Prescription ........................................................................................................ 8

III. International Practices on Territorial Acquisition ..................................... 8

1. Island of Palmas Case ........................................................................................ 8

2. Alaska Pacific Fisheries v. United States ......................................................... 10

CONCLUSION ................................................................................................... 11

REFERENCE MATERIAL ............................................................................... 11 INTRODUCTION

International Law is based on the concept of the State. No State can exist without

territory. International disputes pertaining to land title as well as the precise determination

of State boundaries, are the subject of international proceedings. As you know, the

international community comprises States, and the existence of the States are defined by

their territory and sovereignty. The sovereignty sits at the heart of International Law. The

title to territory is based on sovereignty. State exercises its supreme authority within its

territory. The territorial sovereignty enables a State to exercise its fullest measure of

sovereignty powers over its land territory. In order to function as a State, the State must

possess territory. However, there are territories over which there is no sovereign.

So how can an entity acquire its own territory in international law while under

classical international law, until a new state is created, there is no legal person in existence

competent to hold title. None of the traditional modes of acquisition of territorial title

satisfactorily resolves the dilemma, which has manifested itself particularly in the

postSecond World War period with the onset of decolonization. In recent years, based on

discussions in international conferences and institutions, such as United Nations,

international law considered two methods by which a new entity may gain its independence

as a new state: by constitutional means, that is by agreement with the former controlling

administration in an orderly devolution of power, or by non-constitutional means, usually

by force, against the will of the previous sovereign. In case that the new entity gains its

independence contrary to the wishes of the previous authority, whether by secession or lOMoAR cPSD| 45734214

revolution. It may be that the dispossessed sovereign may ultimately make an agreement

with the new state recognizing its new status, but in the meantime the new state might well

be regarded by other states as a valid state under international law. Where a state gains its

sovereignty in opposition to the former power, new facts are created and the entity may

well comply with the international requirements as to statehood, such as population,

territory and government. Other states will then have to make a decision as to whether or

not to recognize the new state and accept the legal consequences of this new status.

Historically, there have been several distinct methods for acquiring sovereignty over the

land. These categories are now widely acknowledged to be insufficient in many ways. The

categorization of these modes was inspired by Roman law rules governing the acquisition

of land by private parties. Cession, efficient occupation, accretion, conquest or subjugation,

and prescription are acquisition modes. CONTENT I. Overview

1. National territory

During the process of human development, along with the emergence of nations,

international law has gradually formed and developed.

International law is a system of legal principles and norms that regulate relationships

between subjects of international law. A country is an entity made up of three elements:

human, territory and sovereign government.

National territory is one of the indispensable constituent elements of a country to determine

whether a country is a subject of international relations and international law. Countries

develop in a close relationship with their territories. Territory is the basis and material

foundation for a country to exist and develop. According to international law, national

territory belongs to the complete and exclusive sovereignty of the nation. Therefore, a

country's territorial sovereignty - a part of national sovereignty is the country's supreme,

complete and exclusive power over its territory. Countries have the right to occupy, use and

dispose of their territory independently. So, in territorial disputes, determining a country's

territorial sovereignty is of fundamental importance. lOMoAR cPSD| 45734214

2. Legal acquisition of territory

Territorial acquisition is the act of a country establishing its sovereignty over a new

territory, or in other words, expanding its existing territory, adding a new territory to the national territorial map.

International law on territorial acquisition is a branch of law that appeared early and played

an important role. Territorial acquisition provisions help resolve the question of how a state

can legally establish sovereignty over a new territory against the claims of other states.

Through the history of development, it seems that there is no country that does not have

territorial fluctuations, and this branch of international law will legalize or illegalize these fluctuations. II.

The modes of legal acquisition of territory in International Law

1. Occupation

Occupation is a method of acquiring territory which belongs to no one (terra nullius) and

which may be acquired by a state in certain situations. The occupation must be by a state

and not by private individuals, it must be effective and it must be intended as a claim of

sovereignty over the area. The high seas cannot be occupied in this manner for they are res

communis, but vacant land may be subjected to the sovereignty of a claimant state. It relates

primarily to uninhabited territories and islands, but may also apply to certain inhabited lands.

2. Accretion

This describes the geographical process by which new land is formed and becomes attached

to existing land, as for example the creation of islands in a river mouth or the change in

direction of a boundary river leaving dry land where it had formerly flowed. Where new

land comes into being within the territory of a state, it forms part of the territory of the state

and there is no problem. When, for example, an island emerged in the Pacific after an under-

sea volcano erupted in January 1986, the UK government noted that: ‘We understand the

island emerged within the territorial sea of the Japanese island of Iwo Jima. We take it

therefore to be Japanese territory.’1 As regards a change in the course of a river forming a

boundary, a different situation is created depending on whether it is imperceptible and

slight or a violent shift (avulsion). In the latter case, the general rule is that the boundary

1 C. C. Hyde, International Law, 2nd edn, Boston, 1947, vol. I, pp. 355–6; O’Connell, International Law, pp. 428– 30;

and Oppenheim’s International Law, pp. 696–8 lOMoAR cPSD| 45734214

stays at the same point along the original river bed.2 However, where a gradual move has

taken place the boundary may be shifted3. If the river is navigable, the boundary will be the

middle of the navigable channel, whatever slight alterations have occurred, while if the

river is not navigable the boundary will continue to be the middle of the river itself. This

aspect of acquiring territory is relatively unimportant in international law but these rules

have been applied in a number of cases involving disputes between particular states of the United States of America.

3. Cession

This involves the peaceful transfer of territory from one sovereign to another (with the

intention that sovereignty should pass) and has often taken place within the framework of

a peace treaty following a war. Indeed the orderly transference of sovereignty by agreement

from a colonial or administering power to representatives of the indigenous population

could be seen as a form of cession. Cession has the effect of replacing one sovereign by

another over a particular piece of territory, so the acquiring state cannot possess more rights

over the land than its predecessor had. This is an important point, so that where a third state

has certain rights, for example, of passage over the territory, the new sovereign must respect

them. It is expressed in the land law phrase that the burden of obligations runs with the

land, not the owner. In other words, the rights of the territorial sovereign are derived from

a previous sovereign, who could not, therefore, dispose of more than he had. This contrasts

with, for example, accretion, which is treated as an original title, there having been no

previous legal sovereign over the land. The Island of Palmas case emphasizes this point. It

concerned a dispute between the United States and the Netherlands. The claims of the

United States were based on an 1898 treaty with Spain, which involved the cession of the

island. It was emphasized by the arbitrator and accepted by the parties that Spain could not

thereby convey to the Americans greater rights than it itself possessed. The basis of cession

lies in the intention of the relevant parties to transfer sovereignty over the territory in

question3. Without this it cannot legally operate. Whether an actual delivery of the property

is also required for a vae against the territorial integrity or political independence of any

state. However, force will be legitimate when exercised in self-defense. Whatever the

circumstances, it is not the successful use of violence that in international law constituted

2 Georgia v. South Carolina 111 L.Ed.2d 309, 334; 91 ILR, pp. 439, 458 3

ICJ Reports, 1992, pp. 351, 546.

3 Sovereignty over the territorial sea contiguous to and the airspace above the territory concerned would pass with

the land territory: see the Grisbadarna case, 11 RIAA, p. 147 (1909) and the Beagle Channel case, HMSO, 1977; 52

ILR, p. 93. This suggests the corollary that a cession of the territorial sea or airspace would include the relevant land

territory: see Oppenheim’s International Law, p. 680 lOMoAR cPSD| 45734214

the valid method of acquiring territory. Under the classical rules, formal annexation of

territory following upon an act of conquest would operate to pass title. It was a legal fiction

employed to mask the conquest and transform it into a valid method of obtaining land under

international law. However, it is doubtful whether an annexation

proclaimed while war is still in progress would have operated to pass a good title to

territory. Only after a war is concluded could the juridical status of the disputed territory

be finally determined. This follows from the rule that has developed to the effect that the

control over the relevant territory by the state purporting to annex must be effective and

that there must be no reasonable chance of the former sovereign regaining the land.

Acquisition of territory following an armed conflict would require further action of an

international nature in addition to domestic legislation to annex. Such further necessary

action would be in the form either of a treaty of cession by the former sovereign or of international recognition.

4. Conquest

Conquest, the act of defeating an opponent and occupying all or part of its territory, does

not of itself constitute a basis of title to the land. It does give the victor certain rights under

international law as regards the territory, the rights of belligerent occupation, but the

territory remains subject to the legal title of the ousted sovereign. Sovereignty as such does

not merely pass by conquest to the occupying forces, although complex situations may

arise where the legal status of the territory occupied is, in fact, in dispute prior to the

conquest. Conquest, of course, may result from a legal or an illegal use of force. By the

Kellogg–Briand Pact of 1928, war was outlawed as an instrument of national policy, and

by article 2(4) of the United Nations Charter all member states must refrain from the threat

or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.

However, force will be legitimate when exercised in self-defense. 4 Whatever the

circumstances, it is not the successful use of violence that in international law constituted

the valid method of acquiring territory. Under the classical rules, formal annexation of

territory following upon an act of conquest would operate to pass title. It was a legal fiction

employed to mask the conquest and transform it into a valid method of obtaining land under

international law. However, it is doubtful whether an annexation proclaimed while war is

still in progress would have operated to pass a good title to territory. Only after a war is

concluded could the juridical status of the disputed territory be finally determined. This

follows from the rule that has developed to the effect that the control over the relevant

4 article 51 of the UN Charter and below, chapter 19. lOMoAR cPSD| 45734214

territory by the state purporting to annex must be effective and that there must be no

reasonable chance of the former sovereign regaining the land.

5. Prescription

Prescription is a mode of establishing title to territory which is not terra nullius (meaning)

and which has been obtained either unlawfully or in circumstances wherein the legality of

the acquisition cannot be demonstrated. It is the legitimation of a doubtful title by the

passage of time and the presumed acquiescence of the former sovereign, and it reflects the

need for stability felt within the international system by recognizing that territory in the

possession of a state for a long period of time and uncontested cannot be taken away from

that state without serious consequences for the international order.

To establish such a case for the usurpation of title, certain prerequisites need to be clearly established: (1)

Possession must be exercised à titre de souverain. There must be a display of state

authority and the absence of recognition of sovereignty in another state, for example under

conditions of a protectorate leaving the protected state with a separate personality. Without

adverse possession there can be no prescription. (2)

The possession must be public, peaceful, and uninterrupted. As Johnson has

remarked: ‘Publicity is essential because acquiescence is essential’. By contrast in a

situation of competing state activity, as in Island of Palmas, publicity will not play an

important role because acquiescence may not be relevant except in minor respects. (3)

Finally, possession must persist. In the case of recent possession it is difficult to

adduce evidence of tacit acquiescence. A few writers have prescribed fixed periods of

years. Such suggestions are due to a yearning after municipal models and to the influence

of the view that ‘acquiescence’ may be ‘implied’ in certain conditions. The better view is

that the length of time required is a matter of fact depending on the particular case.

III. International Practices on Territorial Acquisition

1. Island of Palmas Case 1.1. Case background

Palmas (Miangas) is an island of little economic value or strategic location. It is 2.6 km in

north–south length and 1.0 km in east–west width. In 1606, Spain occupied this island;

however, the nation gave up sovereignty over this island and left. After that, The

Netherlands established sovereignty over the island through agreements signed between

the Netherlands and native leaders. In 1898, Spain ceded the Philippines to the United lOMoAR cPSD| 45734214

States in the Treaty of Paris (1898) and Palmas is located within the boundaries of that

cession. In 1906, the United States discovered that the Netherlands also claimed

sovereignty over the island. After unsuccessful reconciliations, on January 23, 1925, the

United States of America and the Netherlands referred their dispute concerning sovereignty

over the Island of Palmas to arbitration by a sole arbitrator. The sole arbitrator was asked

to determine whether the Island of Palmas (or Miangas) in its entirety formed a part of the

territory belonging to the United States of America or of the territory of the Netherlands.

The arbitrator in the case was Max Huber, a Swiss lawyer.

1.2. The views of the litigants: The USA:

The United States, as successor to Spanish sovereignty in the Philippines, relied heavily on

the principle of first possession. Historically, Spain occupied this island earlier than the

Netherlands. Legally, according to the map attached to the 1898 Treaty of Paris, Palmas

belongs to the Philippines. In 1899, the United States informed the Netherlands about the

Treaty of Paris, which the Netherlands had no opinion about. Additionally, the Treaty of

Munster 1648 obtained a declaration of peace between Spain and the Netherlands including territorial issues.

Therefore, the USA claimed that Palmas Island is part of Philippine territory and the United

States took possession of the first discoverer through the transfer of legal ownership from

Spain Palmas forms a geographical part of the Philippine group and is closer to the

Philippines than the Dutch East Indies. • The Netherland:

The Netherlands rejected the above arguments and used the actual, peaceful and continuous

exercise of sovereignty over the island since 1677 as the basis to prove its territorial

sovereignty over the island of Palmas. The Netherlands said that Palmas previously

belonged to the local state of Tabukan. Thus, the Tabukan state is the actual direct possessor

of Palmas Island, not Spain, even though Spain discovered Palmas Island first. In addition,

Tabukan reached an agreement with the Netherlands that the Netherlands would manage

and control Palmas and deny other nations control over the island. 1.3. Final discussion

Max Huber admitted that Spain first discovered the island of Palmas, but to determine

territorial sovereignty, the country that discovered that territory must supplement the above

incomplete title with actual possession. within a reasonable period of time. However, there

is no evidence of any Spanish activity on the island of Palmas. He said Spain could not

transfer to the United States more than the rights which this nation possesses.

Next, regarding the silence of the Netherlands under the Treaty of Paris, the arbitrator said

that it was true that the Netherlands had no objections or reservations when notified by the lOMoAR cPSD| 45734214

United States of the 1898 Treaty of Paris, but its territorial sovereignty A State cannot be

affected merely because it had remained silent before an Agreement which has notified it

and which appears to have decided upon a part of its territory.

Then, Tabukan directly depended on the Dutch State through agreements recognizing the

protection rights of the Dutch State and The Netherlands collected taxes on the island's

residents and placed its national emblem and flag on the island before 1898.

From the above arguments, Max Huber declared the island of Palmas under Dutch sovereignty.

Types: The nature of the dispute is due to territorial acquisition between the United States

and Spain and the dispute over the sovereignty of Palmas between the Netherlands and Spain.

2. Alaska Pacific Fisheries v. United States 2.1. Case background

Alaska is bordered by Canada to the east, the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Pacific Ocean

to the west and south, and faces mainland Russia across the Bering Strait. Alaska has an

area of 1.7 million square kilometers and is home to nearly half of the world's glaciers.

Russians began to settle in Alaska in 1784 but it was very limited. Around the 19th century,

the Russian territory of Alaska was also an international trade center. Merchants traded

cloth, Chinese tea and even ice. The shipbuilding industry also developed here and there

were many factories and mineral mines, especially gold. However, because of financial

difficulties and concerns about not being able to defend Alaska because Britain was

expanding its influence in western Canada and Russia was worried. Therefore, the Tsar

intended to sell Alaska to the United States. 2.2. Processes

Russia sent a survey team to Alaska to evaluate natural resources here. Valued at about 10

million USD, most surveyors believed that Russia should not sell Alaska, instead it should

focus on reform for development. Ignoring the survey team's advice, Tsar Alexander II

ordered the assessment to be forwarded to the US government. Negotiations went smoothly

and after a short period of discussion, on March 30, 1867, in Washington DC, then US

Secretary of State William H. Seward and Russian Minister Edouard de Stoeckl signed the

Treaty to sell Alaska to the US. Accordingly, Russia agreed to sell approximately 1.7

million square kilometers of land to the US for 7.2 million USD. The United States Senate

ratified the treaty on April 9, 1867, with 37 votes in favor and 2 votes against. However,

arranging money to pay for Alaska was delayed for more than a year due to opposition lOMoAR cPSD| 45734214

from the House of Representatives. The House of Representatives finally passed it in June

1868, with 113 votes in favor and 48 votes against. Russia officially handed over Alaska to

the United States in October 18675. 2.3. Final discussion

Alaska became American land. Currently, Alaska is a developed land with 25% of

America's oil and more than 50% of seafood coming from this land. Besides, this is a land

with countless rare flora and fauna species along with abundant mineral reserves, so this

land has a lot of potential for further development.

Type: Acquisition of territory by transfer CONCLUSION

Territorial sovereignty is defined as a state’s ability to assume that other states (as well as

other global subjects of law) refrain from performing activities about state sovereignty.

This judicial scenario, or interpretive right of exclusion, is opposable erga omnes. Its vital

necessity is based on the efficacy of a State’s sovereignty in its territory and within its borders. REFERENCE MATERIAL

1. Charter of the United Nations

2. Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969.

3. Malcolm N. Shaw, International Law, 6th ed., CUP, 2008.

4. REPORTS OF INTERNATIONAL ARBITRAL AWARDS. Island of Palmas case

(Netherlands, USA), 4 April 1928.

5. Alaska Pacific Fisheries v. United States, 248 U.S. 78, 1918

6. Check for the Purchase of Alaska (1868), 2022

5 Milestone Documents, ‘Check for the Purchase of Alaska (1868)’, 2022.