Preview text:

Journal of Personalized Medicine Case Report

Cardiac Arrest and Complete Heart Block: Complications after

Electrical Cardioversion for Unstable Supraventricular

Tachycardia in the Emergency Department

Adina Maria Marza 1,2 , Claudiu Barsac 1,3,*, Dumitru Sutoi 1 , Alexandru Cristian Cindrea 1,2 ,

Alexandra Herlo 4, Cosmin Iosif Trebuian 1,5 and Alina Petrica 1,6 1

Department of Surgery, “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, 300041 Timisoara, Romania;

marza.adina@umft.ro (A.M.M.); dumitru.sutoi@umft.ro (D.S.);

alexandru.cindrea.umfvbt@gmail.com (A.C.C.); trebuian.cosmin@umft.ro (C.I.T.); alina.petrica@umft.ro (A.P.) 2

Emergency Department, Emergency Clinical Municipal Hospital, 300079 Timisoara, Romania 3

Clinic of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, “Pius Brinzeu” Emergency Clinical County Hospital, 300736 Timisoara, Romania 4

Department of Infectious Diseases, “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, 300041 Timisoara,

Romania; alexandra.mocanu@umft.ro 5

Department of Anesthesia and Intensive Care, Emergency County Hospital, 320210 Resita, Romania 6

Emergency Department, “Pius Brinzeu” Emergency Clinical County Hospital, 300736 Timisoara, Romania *

Correspondence: claudiu.barsac@umft.ro; Tel.: +40-728950041

Abstract: Synchronous electrical cardioversion is a relatively common procedure in the emergency

department (ED), often performed for unstable supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) or unstable

ventricular tachycardia (VT). However, it is also used for stable cases resistant to drug therapy, which

carries a risk of deterioration. In addition to the inherent risks linked with procedural sedation, there

is a possibility of malignant arrhythmias or bradycardia, which could potentially result in cardiac

arrest following this procedure. Here, we present a case of complete heart block unresponsive to

transcutaneous pacing and positive inotropic and chronotropic drugs for 90 min, resulting in multiple

Citation: Marza, A.M.; Barsac, C.;

cardiac arrests. The repositioning of the transcutaneous cardio-stimulation electrodes, one of them

Sutoi, D.; Cindrea, A.C.; Herlo, A.;

placed in the left latero-sternal position and the other at the level of the apex, led to immediate

Trebuian, C.I.; Petrica, A. Cardiac

stabilization of the patient. The extubation of the patient was performed the following day, with full

Arrest and Complete Heart Block:

recovery and discharge within 7 days after the insertion of a permanent pacemaker. Complications after Electrical Cardioversion for Unstable

Keywords: supraventricular tachycardia; cardioversion; unstable patient; complete heart block;

Supraventricular Tachycardia in the

ineffective pacing; cardiac arrest; advanced life support

Emergency Department. J. Pers. Med.

2024, 14, 293. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/jpm14030293

Academic Editor: Gianluca Costa 1. Introduction Received: 17 February 2024

Patients with symptomatic supraventricular arrhythmias commonly present in the Revised: 4 March 2024

emergency department (ED), necessitating urgent management. Sporadically, complica- Accepted: 6 March 2024

tions may arise, but there is a lack of comprehensive literature regarding post-cardioversion Published: 9 March 2024

events for supraventricular tachycardia (SVT).

Traditionally, SVT encompasses all tachycardias except for ventricular tachycardias

(VTs) and atrial fibrillation (AF), with atrial rates exceeding 100 beats per minute at rest [1].

Narrow QRS tachycardia is defined as a QRS duration of 120 ms or less, while sometimes,

Copyright: © 2024 by the authors.

they may display a widened QRS complex exceeding 120 ms due to pre-existing conduction

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland.

delays either related to heart rate or to bundle branch blocks [1–3].

This article is an open access article

In the general population, the prevalence of SVT is 2.25 per 1000 individuals, with an

distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons

incidence of 35 per 100,000 person-years [1]; evidence from the United States indicates that

Attribution (CC BY) license (https://

they contribute to approximately 50,000 ED visits each year [4]. However, epidemiological

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/

studies on SVT populations are limited. Women face twice the risk of developing SVT 4.0/).

compared to men, while individuals aged 65 years or older have over five times the risk

J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14030293

https://www.mdpi.com/journal/jpm

J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 293 2 of 9

compared to their younger counterparts [1]. Additionally, SVT is also frequent in patients

with congenital heart disease [5].

The clinical presentations of SVT vary extensively, spanning from mild symptoms like

palpitations and breathing disturbances to severe symptoms associated with hemodynamic

instability and cardiogenic shock, which pose a risk to the patient’s life [6,7]. The assess-

ment and management of all arrhythmias consider both the patient’s condition and the

characteristics of the arrhythmia. The goal is to prevent cardiac arrest.

Therefore, the initial approach in the ABCDE assessment involves identifying the

patient’s adverse features, such as shock, syncope, acute heart failure, and myocardial

ischemia. Additionally, it is essential to consistently monitor the heart rhythm and blood

pressure and administer oxygen if SpO2 falls below 94%. Identifying and addressing

reversible causes, such as electrolyte imbalances or hypovolemia, should be conducted

in accordance with the 2021 European Resuscitation Council (ERC) Guidelines [8]. If

these signs are absent in a patient with regular tachycardia, vagal maneuvers will be

performed [9], with the inverted Valsalva maneuver demonstrated to be more efficient

in adults [1]. In the ED, the standard protocol includes conducting a thorough history,

physical examination, and a 12-lead ECG, supplemented by usual laboratory tests such

as full blood counts, biochemistry profile, and thyroid function assessment. If feasible,

transthoracic echocardiography should also be conducted.

If vagal maneuvers fail to resolve the issue, the initial drug of choice is adenosine

(6–12–18 mg) [1,8]. A recently published study by Xiao et al. compared the efficiency of Val-

salva maneuvers, adenosine, and their combination, but the results were inconclusive [10].

If adenosine proves ineffective, intravenous verapamil, diltiazem, or beta-blockers are the

subsequent treatment options for narrow complex SVT, while intravenous procainamide

or amiodarone are recommended for wide complex SVT. Given that atrioventricular node

blockers are contraindicated for patients with pre-excited atrial fibrillation [11], the differ-

ential diagnosis should be meticulously performed before their administration. If these

treatments are ineffective, synchronized cardioversion of up to three attempts is advised

to terminate the tachycardia. Having a stable patient provides the advantage of granting

the emergency physician the opportunity to seek expert advice for both the differential

diagnosis of SVT and its treatment if initial measures prove unsuccessful.

For unstable patients exhibiting life-threatening features, synchronized cardioversion

under sedation is the treatment of choice [12]. If unsuccessful, administering intravenous

amiodarone at a dose of 300 mg over 10–20 min or intravenous procainamide at a dose of

10–15 mg/kg over 20 min is recommended, followed by repeating synchronized shocks, if necessary [1,8].

Here, we describe a case of a patient requiring electrical cardioversion for SVT. Fol-

lowing the synchronized shock, the patient experienced severe bradycardia, subsequently

progressing to complete heart block unresponsive to medication and pacing, culminating in cardiorespiratory arrest. 2. Case Presentation

A 53-year-old male patient, a known smoker with no other comorbidities except for

a right bundle branch block (RBBB), arrived at the ED via a physician-staffed ambulance.

The patient presented with main complaints of palpitations and fatigue that started approx-

imately 8 h before arrival, along with diaphoresis and dyspnea exacerbated by minimal

efforts, particularly in the last hour.

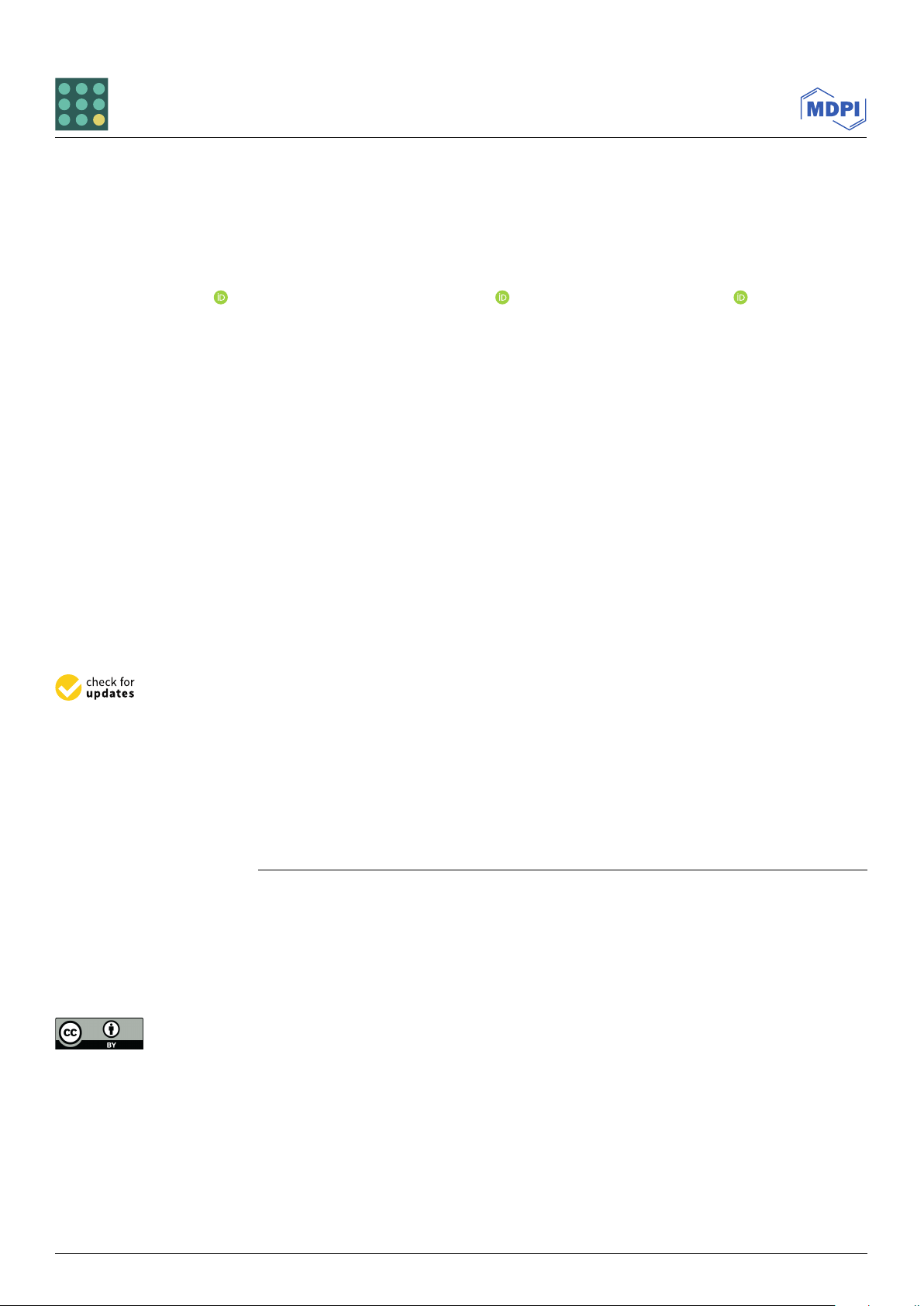

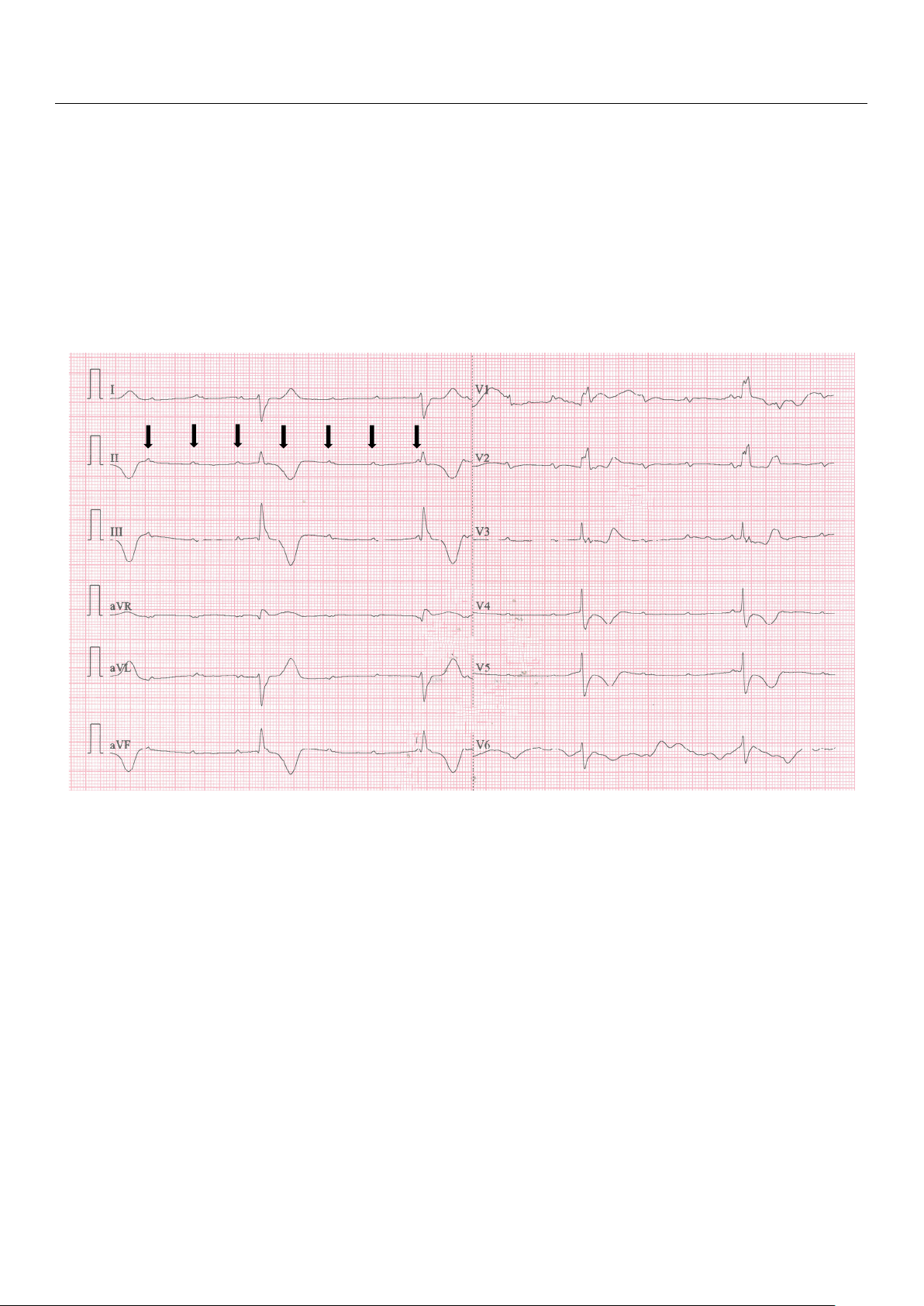

Before reaching the hospital, a 12-lead ECG (Figure 1) and vital signs monitoring

were conducted, revealing SVT with RBBB, a heart rate of 174 BPM, SpO2 at 98%, and

blood pressure of 130/80 mmHg. Deeming the patient’s condition stable, the emergency

physician attempted vagal maneuvers, which had no effect on the heart rate. Adenosine

was administered in three doses (6 mg, 12 mg, 18 mg), also with no impact on the pa-

tient’s condition. After a 30 min period during which 10 mg of metoprolol was slowly

J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, x FOR PEER REVIEW 3 of 10 J.

Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 293 3 of 9 intravenously intravenously administer admini ed stered without success, without succ the ess, th decision e deci was sion wa made s made to transfer to transf the patient er the patient to the ED. to the ED. Figure 1. Figure 1. A A12

12lead-ECG from the ambulance: regular rh

lead-ECG from the ambulance: regular r ythm tachycardia

hythm tachycardia (heart rate 174 (heart rate 174 BPM) and BPM) and wide QRS wide QRS complexes of 0 complexes of .14 s 0.14 s, , with rSR

with rSR’ pattern in V1 and V2; pattern in V1 and V2; finding findings s indicati indicativeve of of supraventric- supraventricular ular tachycardia (SVT) with tachycardia (SVT) with righ right t bundle branch block (R bundle branch block BBB). (RBBB). Upon arr Upon ival

arrival at the ED, the patient

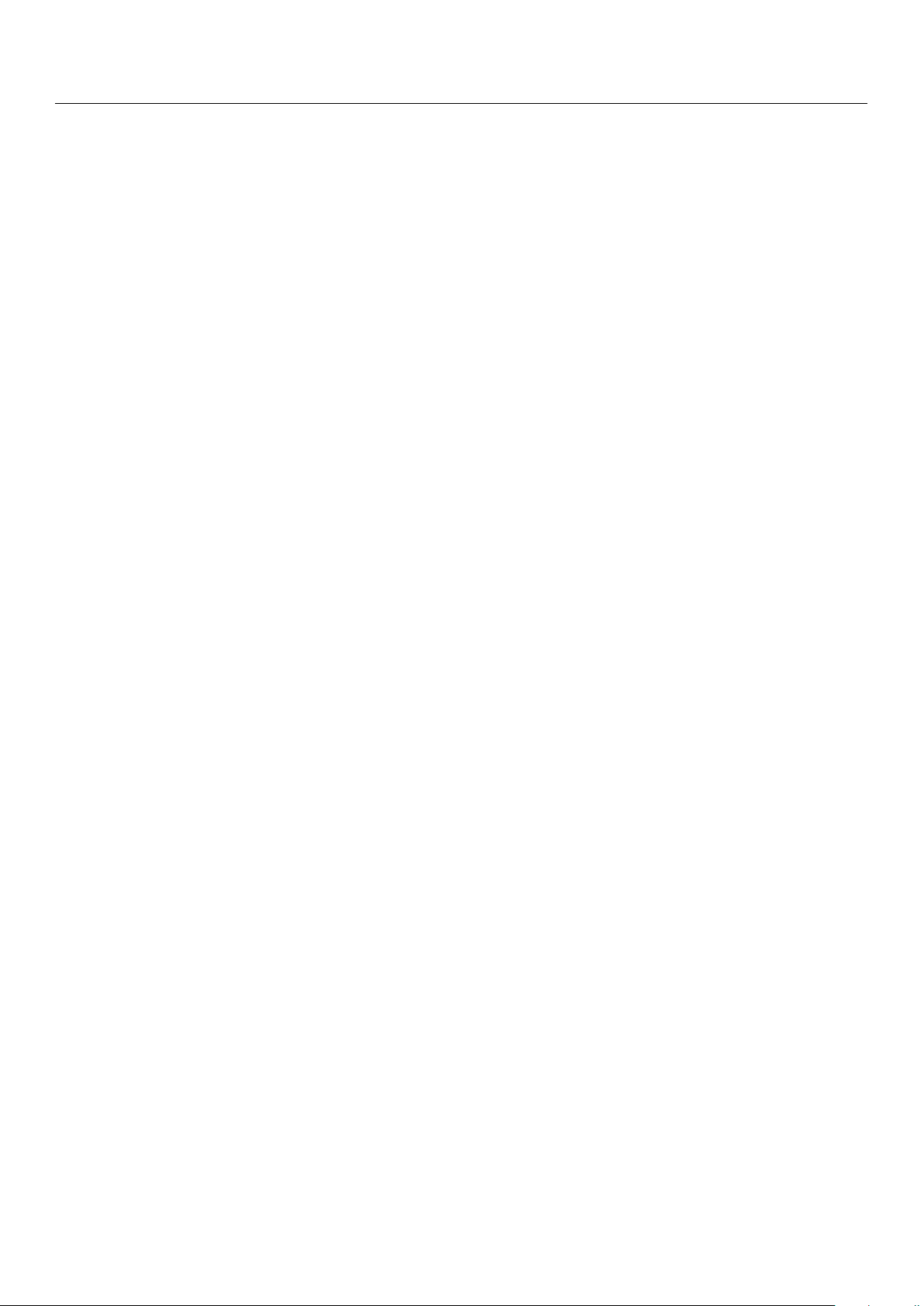

at the ED, the patient appeared appeared conscious an conscious d cooper and ative, b cooperative, ut he but he was was pale, d pale, iaphore diaphor tic, etic, and exh and ibited dy exhibited spnea dyspnea at re at r st. V est. i V tal signs ital signs indicated a periphe indicated a ral oxygen peripheral oxygen saturation of saturation of 93%, b 93%, lood p blood ressu pr re essure at at 90/60 m 90/60 mHg, mmHg,a he a art r heart ate of rate 1 of 74 174BPM, a BPM, cap a illary re capillary r fill efill time of 3 s, time of 3 s,and a barely det and a barely ectable radial detectable radial pulse. The pulse. EC The G show ECG ed SVT with showed SVT with RBBB, RBBB, as seen as seen in F in igure Figure 2.2 .

The patient was administered supplemental oxygen at a rate of 3 L/min; blood work-

up and arterial blood gas analysis were conducted (Table 1). After approximately 30 min,

it was decided that synchronous cardioversion with 70 joules was the optimal course of

action. The patient provided consent for the procedure and was sedated beforehand. J. Pers. Med. J. Pers. 2024 Med. , 2024 14, 14 293 , x FOR PEER REVIEW 4 of 4 of 9 10

Figure 2. First 12-lead ECG (recorded at 25 mm/s, and a voltage of 10 mm/mV) from ED—regular

Figure 2. First 12-lead ECG (recorded at 25 mm/s, and a voltage of 10 mm/mV) from ED—regular

rhythm tachycardia (heart rate 174 BPM), QRS duration of 0.14 s, rSR pattern in V1 and V2 (arrows),

rhythm tachycardia (heart rate 174 BPM), QRS duration of 0.14 s, rSR’ pattern in V1 and V2 (arrows),

absent P waves, negative T waves in V1 and V2; findings suggestive for SVT with RBBB.

absent P waves, negative T waves in V1 and V2; findings suggestive for SVT with RBBB.

The patient was administered supplemental oxygen at a rate of 3 L/min; blood work-

Table 1. Pathological values of the laboratory tests performed upon arrival in the ED.

up and arterial blood gas analysis were conducted (Table 1). After approximately 30 min, it was decided Laboratory t T hat est synchronous V car alue dioversion with Reference 70 jou Range les V w

alueas the optimal course Conventional of Units action. The p Blood atient provid glucose ed consent 146 for the procedure an

74–106 d was sedated beforehand. mg/dL Creatinine 1.52 0.70–1.30 mg/dL Table 1. Pathological D-dimer values of the laborator 1.89 y tests performed upon arriv <0.68 al in the ED. mg/L Lactate 2.52 0.36–0.75 mmol/L Labor NT atory -pr Te o-BNP st Value

10,217Reference Range Value <125 Conventional Un pg/mL its Blood glucose Troponin I 146 58.2 74–106 17–50 mg/dL ng/L Creat White inin blood e 1. cells 52 11.1 0.70–1.30 4.0–10.0 mg × /dL 109/µL Abbr D-dim eviations: er NT 1. -pro-BNP, 89 N-terminal pro-B-type <0.6 natriur 8 etic peptide. mg/L Lactate 2.52 0.36–0.75 mmol/L

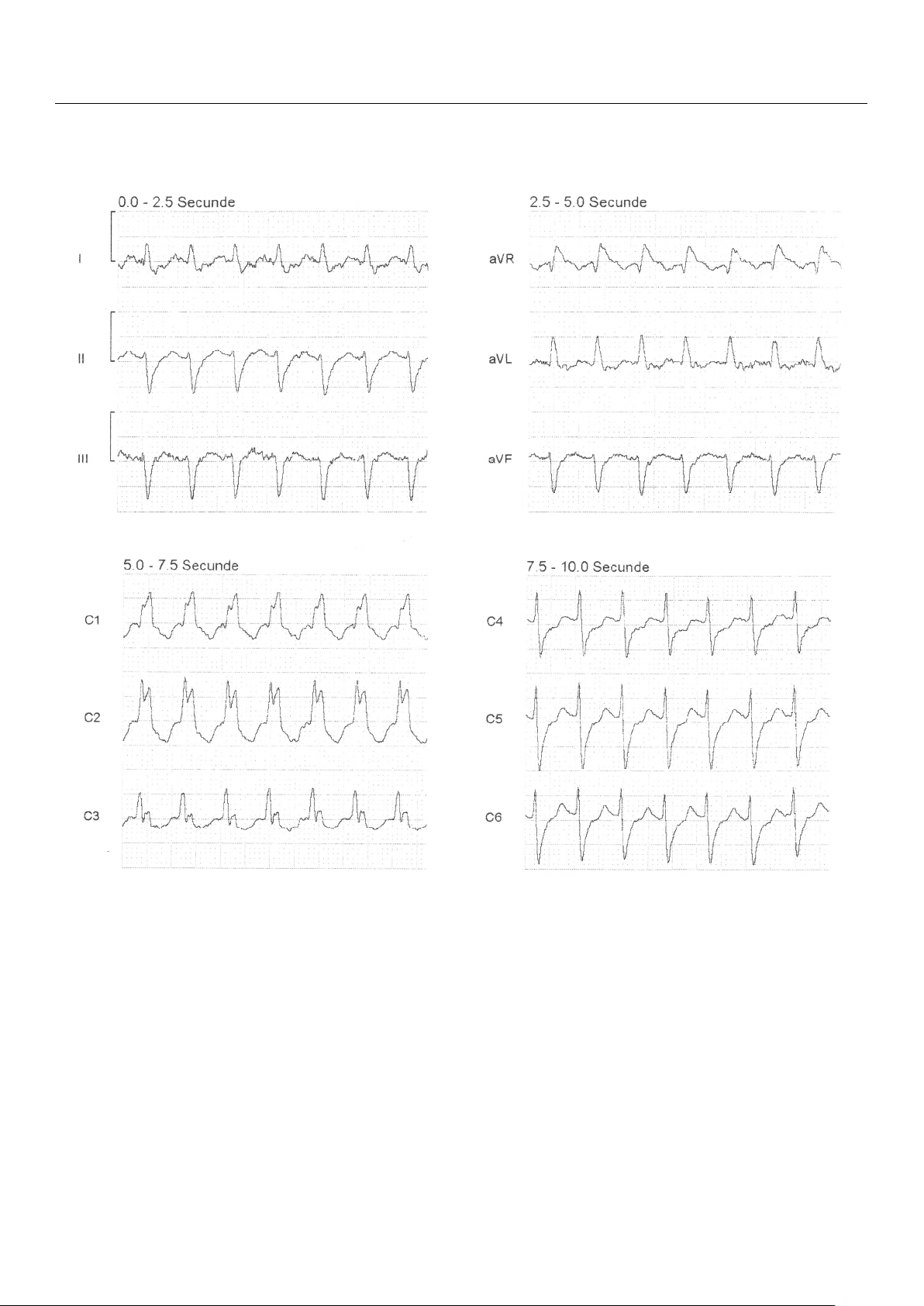

Following the initial synchronous shock, the patient experienced severe bradycardia NT-pro-BNP 10,217 <125 pg/mL

(Figure 3) for a few seconds, transitioning into asystole. Immediate resuscitation measures, Troponin I 58.2 17–50 ng/L

including chest compressions and bag-mask ventilation, were initiated. After about 30 s, White blood cells 11.1 4.0–10.0 ×109/µL

J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, x FOR PEER the patient REVIEW

exhibited spontaneous breathing and movement of limbs, opened his eyes, and 5 of 10

Abbreviations: NT-pro-BNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide. responded to verbal stimuli.

Following the initial synchronous shock, the patient experienced severe bradycardia

(Figure 3) for a few seconds, transitioning into asystole. Immediate resuscitation measures,

including chest compressions and bag-mask ventilation, were initiated. After about 30 s,

the patient exhibited spontaneous breathing and movement of limbs, opened his eyes, and

responded to verbal stimuli. Figure 3. Figure 3. The de The fibrillato defibrillator r

’s s rhythm recording during the electr rhythm recording during the ical electrical card car ioversion shows dioversion shows irreg irr ular egular bradycardia aft bradycardia er the synchro

after the synchr nous shock for onous shock for SVT.

A repeated ECG recording revealed a third-degree AV block (Figure 4), with a heart

rate of 23 BPM, and the patient was hemodynamically unstable. Intravenous Atropine 0.5

mg was administered, followed by additional doses every 2 min, up to a maximum of 3

mg. Simultaneously, Adrenaline was administered via a syringe infusion pump with 2

mcg/min, with no improvement in the patient s condition. Transcutaneous pacing was

initiated with a frequency set to “Demand” at 70 BPM, 80 mA intensity. Although the

monitor indicated efficient capture, the femoral pulse was not concordant. Pacing param-

eters were adjusted to 70 BPM with an increase in intensity up to 160 mA and even 200

mA for short periods of time, yet the myocardium remained unresponsive to external pac- ing.

Figure 4. A 12-lead ECG (recorded at 25 mm/s, and a voltage of 10 mm/mV) after ROSC shows atrio-

ventricular dissociation, with a ventricular heart rate of 27 BPM and QRS duration of 0.17 s, regular

P waves (arrows), variable PR interval, right axis deviation, negative T waves in DII, DIII, aVF, V4–

V6 and ST depression in the V3–V5 leads. The findings are consistent with a complete heart block

and myocardial ischemia in the infero-lateral territory.

Despite efforts to improve hemodynamic stability, the transcutaneous pacing re-

mained ineffective (Figure 5). The patient s thorax was shaved to enhance transcutaneous

conduction, and the initial electrode position (right subclavian/cardiac apex) was changed

to an antero-posterior and, later, to a latero-lateral position. The Adrenaline dose was in-

creased from 2 mcg/min to 20 mcg/min. Additionally, alternative medications, including

J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, x FOR PEER REVIEW 5 of 10

J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 293 5 of 9

Figure 3. The defibrillator s rhythm recording during the electrical cardioversion shows irregular

bradycardia after the synchronous shock for SVT.

A repeated ECG recording revealed a third-degree AV block (Figure 4), with a heart

A repeated ECG recording revealed a third-degree AV block (Figure 4), with a heart

rate of 23 BPM, and the patient was hemodynamically unstable. Intravenous Atropine

rate of 23 BPM, and the patient was hemodynamically unstable. Intravenous Atropine 0.5

0.5 mg was administered, followed by additional doses every 2 min, up to a maximum

mg was administered, followed by additional doses every 2 min, up to a maximum of 3

of 3 mg. Simultaneously, Adrenaline was administered via a syringe infusion pump with

mg. Simultaneously, Adrenaline was administered via a syringe infusion pump with 2

2 mcg/min, with no improvement in the patient’s condition. Transcutaneous pacing

mcg/min, with no improvement in the patient s condition. Transcutaneous pacing was

was initiated with a frequency set to “Demand” at 70 BPM, 80 mA intensity. Although

initiated with a frequency set to “Demand” at 70 BPM, 80 mA intensity. Although the

the monitor indicated efficient capture, the femoral pulse was not concordant. Pacing

monitor indicated efficient capture, the femoral pulse was not concordant. Pacing param-

parameters were adjusted to 70 BPM with an increase in intensity up to 160 mA and

eters were adjusted to 70 BPM with an increase in intensity up to 160 mA and even 200

even 200 mA for short periods of time, yet the myocardium remained unresponsive to

mA for short periods of time, yet the myocardium remained unresponsive to external pac- external pacing. ing.

Figure 4. A 12-lead ECG (recorded at 25 mm/s, and a voltage of 10 mm/mV) after ROSC shows atrio-

Figure 4. A 12-lead ECG (recorded at 25 mm/s, and a voltage of 10 mm/mV) after ROSC shows

ventricular dissociation, with a ventricular heart rate of 27 BPM and QRS duration of 0.17 s, regular

atrio-ventricular dissociation, with a ventricular heart rate of 27 BPM and QRS duration of 0.17 s,

P waves (arrows), variable PR interval, right axis deviation, negative T waves in DII, DIII, aVF, V4– rV6 and ST egular P depr wavesession (arr in the ows), V3–V5 leads. T variable PR he fi

interval, ndings are consistent with right axis deviation, a complete negative T h waves eart block in DII, DIII, and m aVF, yocardia V4–V6 l i and schem ST ia depr in th ession e infero-latera in the V3–V5 l territory leads. .

The findings are consistent with a complete heart

block and myocardial ischemia in the infero-lateral territory.

Despite efforts to improve hemodynamic stability, the transcutaneous pacing re- mained ineff Despite ecti ef ve ( forts Fi to gure impr 5). The pa ove tient s thorax hemodynamic was sh stability, av the ed to enhance tr transcutaneous anscutaneous pacing remained conduction, ineffective and the initial

(Figure 5). The electrode position patient’s thorax (ri was ght sub shavedclav to ian/card enhance iac apex) was changed transcutaneous conduc- to a tion,n antero-posteri and the initial or an electrd, la ode ter, to a la position tero-l (right ateral position. The subclavian/car A diac drena apex) line was dose was changed in- to an creased anter from 2 mcg/min to 20

o-posterior and, later, to mcg/ a min. later Addit o-lateral ionally, position. alternat The iv Adr e medicat enaline ions, dose incl was udin incr g eased

from 2 mcg/min to 20 mcg/min. Additionally, alternative medications, including Amino-

phylline 24 mg over 10 min and Dopamine via a syringe infusion pump at 10 mcg/kg/min, were administered.

Throughout the patient’s stay in the ED, he experienced cardiopulmonary arrest at

least 10 times, manifesting as either asystole or pulseless electrical activity. Each time, the

patient responded positively to external thoracic compressions, mechanical ventilation, and

Adrenaline administration, achieving a return of spontaneous circulation in less than 2 min.

The on-call physician at the regional Institute for Cardiovascular Diseases was con-

tacted and agreed to admit the patient once his condition was stable for transport. Despite

exhausting all available treatment options in the ED (which lacked equipment for transve-

J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, x FOR PEER REVIEW 6 of 10

Aminophylline 24 mg over 10 min and Dopamine via a syringe infusion pump at 10

mcg/kg/min, were administered.

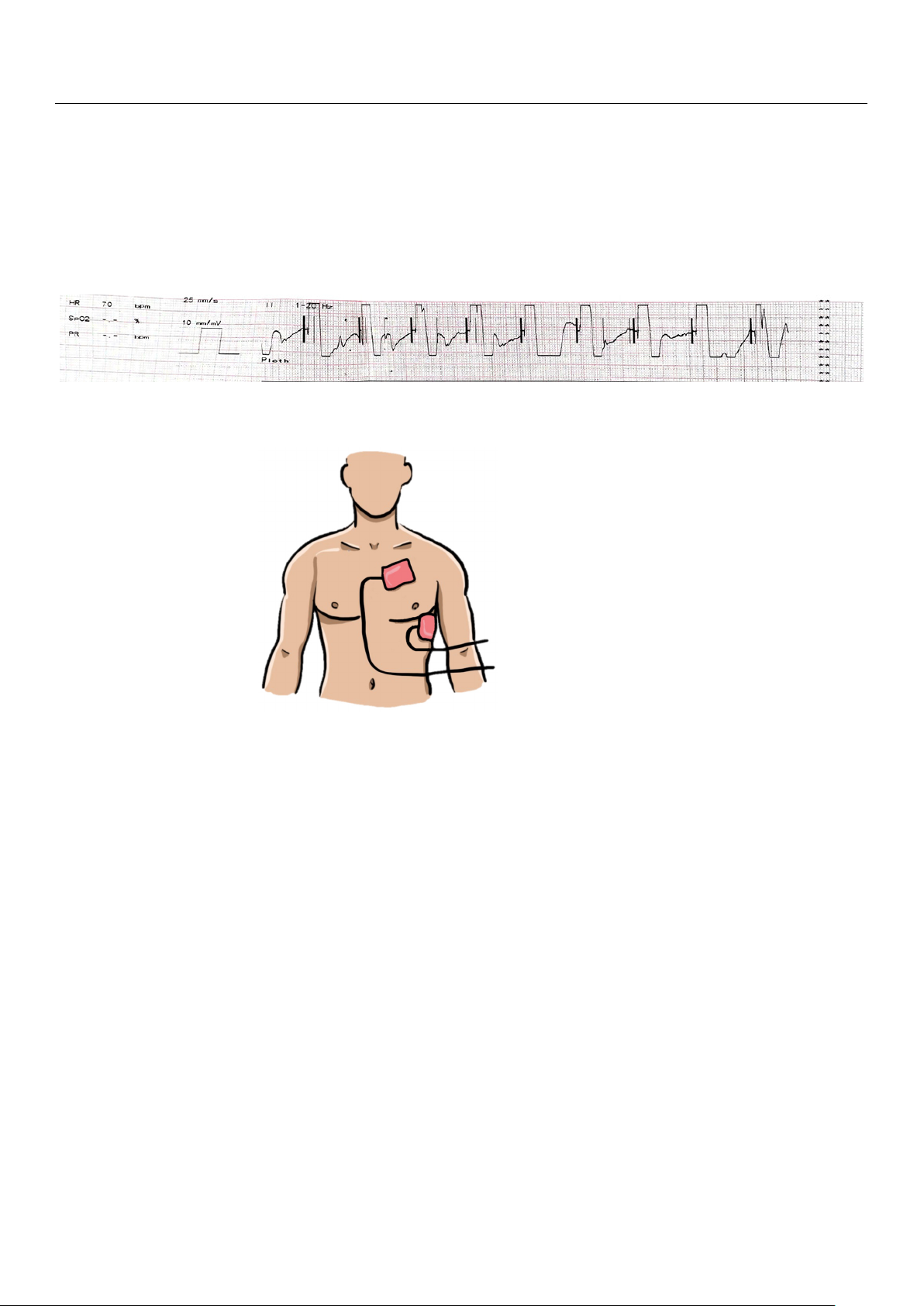

Figure 5. Transcutaneous pacing with ineffective capture and inconsistent femoral pulse. Pacing

J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 293

settings: mode—demand, frequency—70 BPM, intensity—160 mA. 6 of 9

Throughout the patient s stay in the ED, he experienced cardiopulmonary arrest at

least 10 times, manifesting as either asystole or pulseless electrical activity. Each time, the

nous pacing), the patient continued to experience severe hypotension between cardiopul-

patient responded positively to external thoracic compressions, mechanical ventilation,

monary arrest episodes due to the unresponsiveness to transthoracic cardio-stimulation.

and Adrenaline administration, achieving a return of spontaneous circulation in less than

J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, x FOR PEER Considering REVIEW

the inefficacy of pacing, attributable to the patient’s thoracic anatomy with 6 of a 10 2 min.

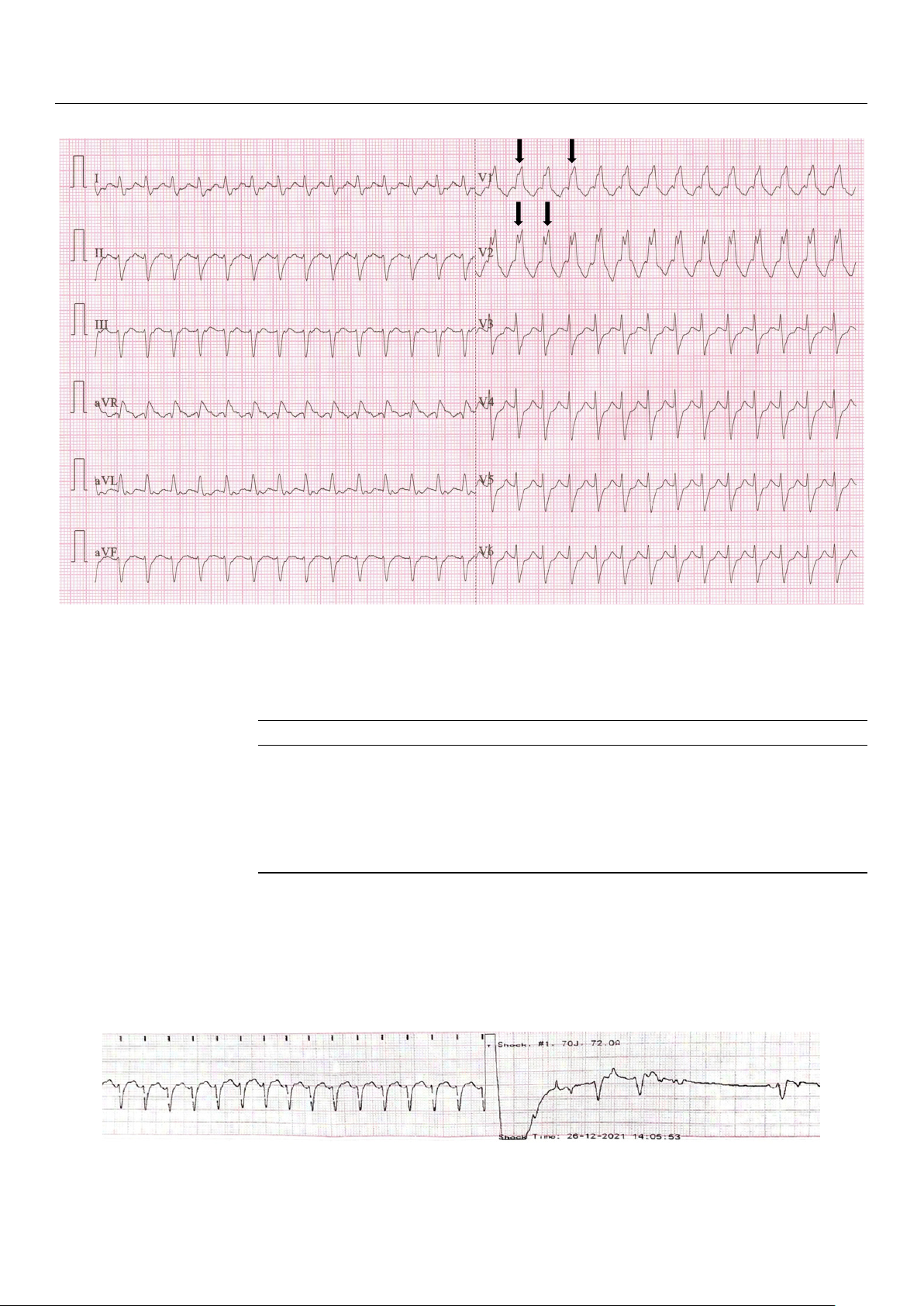

large anterior-to-posterior diameter, a decision was made to reposition the transthoracic

The on-call physician at the regional Institute for Cardiovascular Diseases was con-

pacing leads to subclavicular left (latero-sternal) and cardiac apex (replacing ECG lead V6) positions tacted (Figur and ag e 6). reed to Upon r admit eassessment, the patient on the change ce his cond in lead ition w position as stable resulte for tr d in successful ansport. Despite

Aminophylline 24 mg over 10 min and Dopamine via a syringe infusion pump at 10 pacing exha captur usti e, ng all confirmed availabl by e trea femoral arte tment opti ry ons i pulse n and the ED (an w incr hi ease ch la in blood cked equi pressur pment f e o values. r trans-

mcg/kg/min, were administered.

venous pacing), the patient continued to experience severe hypotension between cardio-

pulmonary arrest episodes due to the unresponsiveness to transthoracic cardio-stimula-

tion. Considering the inefficacy of pacing, attributable to the patient s thoracic anatomy

with a large anterior-to-posterior diameter, a decision was made to reposition the trans-

thoracic pacing leads to subclavicular left (latero-sternal) and cardiac apex (replacing ECG

lead V6) positions (Figure 6). Upon reassessment, the change in lead position resulted in Figure 5. Tran

successful pa scutaneous pacing with ine cing capture, confi ffective captu rmed by femoral re art and incons ery puls iste e an nt femoral pu d an increas lse. e Pacing in blood

Figure 5. Transcutaneous pacing with ineffective capture and inconsistent femoral pulse. Pacing setting pressus: mo re v d a e lu—dem es.

and, frequency—70 BPM, intensity—160 mA.

settings: mode—demand, frequency—70 BPM, intensity—160 mA.

Throughout the patient s stay in the ED, he experienced cardiopulmonary arrest at

least 10 times, manifesting as either asystole or pulseless electrical activity. Each time, the

patient responded positively to external thoracic compressions, mechanical ventilation,

and Adrenaline administration, achieving a return of spontaneous circulation in less than 2 min.

The on-call physician at the regional Institute for Cardiovascular Diseases was con-

tacted and agreed to admit the patient once his condition was stable for transport. Despite

exhausting all available treatment options in the ED (which lacked equipment for trans-

venous pacing), the patient continued to experience severe hypotension between cardio-

pulmonary arrest episodes due to the unresponsiveness to transthoracic cardio-stimula-

tion. Considering the inefficacy of pacing, attributable to the patient s thoracic anatomy

with a large anterior-to-posterior diameter, a decision was made to reposition the trans-

thoracic pacing leads to subclavicular left (latero-sternal) and cardiac apex (replacing ECG

lead V6) positions (Figure 6). Upon re

assessment, the change in lead position resulted in successful p Figure 6.

Figure 6. Pl acing capture, con Placement of both firmed by femor acement of both transcutaneou transcutaneous s stima stimulationl ul art atioe electrry pul odes s on e an n electrode t s he d an incre left ase on the left h hemithorax: in blood emithorax: subclavicu- pressu su lar left re v bclavicu a (later lu lar lees. ft (latero- o-sternal) sternal) and and cardiac cardia apex (r c apex (replacing eplacing ECG lead ECG V6) lead V6) positions. positions. Approximat Appr ely 9 oximately 0 min 90 min after t after he init the ial initial card car ioversion a dioversion ttempt, the patient attempt, the s st patient’s ability stability allowed fo allowed r for transportatio transportationn t to o t the hre regiona egional l Instit Institute ut fore for Ca Car rdiova diovascular scular D Diseases isease for s for transve- transv nous enous pacing pacing. The . The final final eva evaluation luation in indicated di a cated blood a bl pr ood essur pr e of essure of 115/50 115/50 mmHg, mmH heart g, rate hea of rt ra 70 te of BPM, 70 BPM, consi consistent stent f femoral emoral pulse, puls GCS of e, GCS 3 with of 3 wi the th the pa patient tient mecha mechanically nically ventilated ventilat under ed under cont continuous inuous sedative sedative medic medication a and ti r on and receiv eceiving ing inotr ino opic tropic and and vasopr vasopressor essor medica- medicat tion ion (Adren (Adrenaline aline and Dopamin and Dopamine). e Emer ). Em gency ergency transthorac transthoracic i echocarc echocardio diography graphy showed a show left ed a left ventricle ve ofntricle o normal f normal size size w with pr ith pres eserved erved

systolic systolic function, an function, an ejectio ejection n fr fraction action of 50%, of 50%, me medio-basal dio-basal h hypokinesiaypokines of the ia o lateral f th wall,e lateral w concentric all left , concentr ventricularic left v hypertr entricul ophy, ar grade hyp II ertrop mitral hy, and grade II m tricuspid r itral egur and tricu gitation, spid reg medium urgitation, m secondary edium s pulmonaryecondary pulm hypertension, onary dilated

right ventricle, and a posterior pericardial fluid blade measuring below 1 cm.

Upon arrival at the regional Institute for Cardiovascular Diseases, the patient’s con-

dition improved with the placement of the transvenous pacing probe, later replaced with

a permanent pacemaker implant. The following day, the patient was extubated, demon- strating complete hemodynamic

and neurologic recovery, and was discharged from the hospital a week later.

Figure 6. Placement of both transcutaneous stimulation electrodes on the left hemithorax:

subclavicular left (latero-sternal) and cardiac apex (replacing ECG lead V6) positions. 3. Discussion Approximat Synchr e onizedly 9 car 0 min aft dioversioer t n, ahe initial card potentially ioversion life-saving a pr ttempt, the patient ocedure, is s st commonly ability utilized al inlow the ed fo emer r transport gency ation t department o t for he regional Instit hemodynamically ute for Ca unstable rdiova tachyarr scular D hythmias.isease Emers for gency transvenou physicians s pacing should . The fi possess na a l eva thor luation i ough ndicated a bl understanding ood of pr the essure of 115 indications /50 and mmHg, potential heart rate of 7 complications 0 BPM, consi before r stent femoral ecommending or pulse, GCS performing of this 3 with the pa intervention. tient mecha The eff nical ectivenessly of ve fr ntilated un equently der cont utilized inuous anti-arr sedativ hythmic e m dr edic ugs is at r ion and receiv estricted in ing these inotropic and situations, vasopressor primarily due to

medication (Adrenaline and Dopamine). Emergency transthoracic echocardiography

showed a left ventricle of normal size with preserved systolic function, an ejection fraction

of 50%, medio-basal hypokinesia of the lateral wall, concentric left ventricular

hypertrophy, grade II mitral and tricuspid regurgitation, medium secondary pulmonary

J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 293 7 of 9

concerns over side effects and their potential to induce arrhythmias, thereby limiting their usage [13].

When selecting the appropriate method for cardioversion, it is important to follow

the current guidelines and carefully weigh the potential benefits and risks associated with

each intervention. Sometimes, the patient is at the threshold of receiving either electrical or

drug cardioversion and requires a prompt decision to distinguish between the two, given

that both interventions carry inherent risks. Ventricular fibrillation (VF) as a complication

of electrical cardioversion was documented in numerous studies, particularly when car-

dioversion takes place during the vulnerable period of repolarization, typically around the

peak of the T wave on the ECG [14,15]. In 2004, Lyndon and Abdul described such a case,

highlighting the significance of adjusting the lead configuration on the defibrillator monitor

to prevent mistaking the high T wave for the R wave, thereby averting the induction

of VF during the administration of synchronous external electric shock [15]. Kaufmann

et al. described two cases of iatrogenic ventricular fibrillation after the cardioversion of

pre-excited atrial fibrillation due to inadvertent T-wave synchronization [16].

In this scenario, the patient was presented with recent-onset palpitations lasting several

hours, and appropriate drug therapy had already been administered in prehospital settings.

Given the unavailability of intravenous verapamil or diltiazem in the region, the only

remaining option for terminating the tachycardia was electrical cardioversion. Considering

the patient’s known history of right bundle branch block, the tachycardia was managed as

SVT. Chronologically, the decision to proceed with electrical cardioversion was made over

an hour after the last bolus of metoprolol, during which time no significant reduction in heart rate was observed.

Severe bradycardia, immediately followed by complete heart block and subsequent

cardiac arrest with pulseless electrical activity, was an unexpected and rarely reported

complication of synchronized cardioversion. Similar outcomes were described by Gallagher

et al., who conducted a retrospective cohort study examining the relationship between

shock energy and arrhythmic complications of electrical cardioversion. Sinus bradycardia

or a slow junctional escape rhythm was observed in 22 cases, with 20 resolving within

minutes after cardioversion. While two patients required permanent pacing before hospital

discharge, neither needed rate support while awaiting pacemaker implantation. None of

these patients experienced cardiac arrest. They also found that the incidence of ventricular

fibrillation (VF) following shocks of <200 J was significantly higher compared to higher

energy shocks (5 out of 2959 vs. 0 out of 3439 shocks, p = 0.021). Additionally, non-

sustained broad complex tachycardia occurred in four cases, all lasting less than 10 s: two

after shocks > 200 J and two after shocks less than 200 J. The induction of atrial fibrillation

(AF) was significantly more common with shocks of <200 J (20 out of 930 shocks vs. 1 out

of 313 shocks at ≥200 J, p = 0.015) [17].

The success of cardioversion relies on several factors, with time being the most crucial.

In this case, the patient experienced symptoms for several hours, and the initial EKG

recording, which revealed SVT with a heart rate of 174, was conducted more than three

hours prior to arriving at the ED. Nevertheless, the patient initially declined to come to the

hospital. The prolonged duration of the tachyarrhythmia could potentially lead to both

post-repolarization and conduction delays due to global ischemia, as described in other

studies, which reported VF as a complication following cardioversion for AF [18,19].

Furthermore, a proposed theory regarding the mechanism of complete heart block

in this patient was the administration of intravenous metoprolol before cardioversion,

given that beta blockers are known as drugs with sinoatrial and/or atrioventricular nodal-

blocking properties [20]. In a retrospective and prospective study conducted by Osmonov

et al. involving 108 patients treated with atrioventricular blockers and presenting symp-

tomatic type II second- or third-degree AV block, 2:1 AV block, atrial fibrillation, and brad-

yarrhythmia, it was found that 36 patients treated with metoprolol experienced metoprolol-

induced AV blocks that persisted or recurred in 24 patients [21].

J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 293 8 of 9

However, the maximum therapeutic dose of 15 mg (recommended by ESC guidelines,

American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Prac-

tice Guidelines, and the Heart Rhythm Society for stable SVT) [1,20] was not achieved in

this case; only 10 mg was administered intravenously in 2.5 mg boluses, with no discernible

effect on heart rate following the last bolus. This hypothesis was considered due to the

lack of effectiveness of the transcutaneous pacing, assuming the patient had a stronger

response to beta-blockers. Unfortunately, glucagon, the antidote for beta-blocker overdose,

was unavailable at the time in any of the hospitals in the area, preventing the assessment of this hypothesis.

Also, myocardial ischemia or metabolic disturbances such as acidosis and hypoxia

were described as factors that can elevate the pacing threshold and potentially prevent

capture [22]. The patient experienced both metabolic acidosis and severe hypoxemia in

the period following cardioversion, conditions that were rectified only after successful cardiac pacing.

Successful capture is typically identified by a widened QRS complex, succeeded by

a clear ST segment and broad T wave. A pulse rate manually confirmed in the femoral

artery or right carotid artery notably lower than the pacing rate displayed on the pacing

unit monitor may suggest a lack of capture [22].

In this case, achieving efficient capture required placing the electrodes closer together.

While we cannot definitively assert that this positional change was the sole factor stabilizing

the patient, given the limited application to only one patient, it proved to be the sole

measure in a unique and critical situation that yielded an immediate positive effect, leading

to a sudden improvement in the patient’s condition. Consequently, we cannot consistently

advocate or recommend this procedure in routine practice. However, in similar situations

where other well-known methods prove ineffective and the patient’s condition continuously

deteriorates, as exemplified in this case report, it may be considered a life-saving measure. 4. Conclusions

Cardiac arrest and complete heart block are uncommon complications following

electrical cardioversion. Given the infrequency of capture failure cases with transcutaneous

pacing, addressing each isolated case can provide significant benefits to both the ED and

prehospital staff, particularly in the management of atypical situations.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, A.M.M.; methodology, A.M.M. and C.B.; software, A.C.C.;

validation, C.B., C.I.T. and A.P.; investigation, A.M.M., A.H. and C.I.T.; resources, A.M.M.; data

curation, A.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.M. and A.P.; writing—review and editing,

A.M.M., D.S., C.B., A.C.C., A.H. and A.P.; visualization, D.S. and A.C.C.; supervision, A.P. All authors

have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: The APC was funded by “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy from Timisoara.

Institutional Review Board Statement: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration

of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Emergency Clinical Municipal Hospital from

Timisoara, Romania (number 10050/12.04.2023).

Informed Consent Statement: Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement: The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 293 9 of 9 References 1.

Brugada, J.; Katritsis, D.G.; Arbelo, E.; Arribas, F.; Bax, J.J.; Blomström-Lundqvist, C.; Calkins, H.; Corrado, D.; Deftereos, S.G.;

Diller, G.-P.; et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Supraventricular TachycardiaThe Task Force for the

Management of Patients with Supraventricular Tachycardia of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 655–720. [CrossRef] [PubMed] 2.

Bibas, L.; Levi, M.; Essebag, V. Diagnosis and Management of Supraventricular Tachycardias. Can. Med Assoc. J. 2016, 188,

E466–E473. [CrossRef] [PubMed] 3.

Ding, W.Y.; Mahida, S. Wide Complex Tachycardia: Differentiating Ventricular Tachycardia from Supraventricular Tachycardia.

Heart 2021, 107, 1995–2003. [CrossRef] [PubMed] 4.

Murman, D.H.; McDonald, A.J.; Pelletier, A.J.; Camargo, C.A. U.S. Emergency Department Visits for Supraventricular Tachycardia,

1993–2003. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2007, 14, 578–581. [CrossRef] [PubMed] 5.

Wasmer, K.; Eckardt, L. Management of Supraventricular Arrhythmias in Adults with Congenital Heart Disease. Heart 2016, 102,

1614–1619. [CrossRef] [PubMed] 6.

Patti, L.; Ashurst, J.V. Supraventricular Tachycardia; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. 7.

Shah, R.L.; Badhwar, N. Approach to Narrow Complex Tachycardia: Non-Invasive Guide to Interpretation and Management.

Heart 2020, 106, 772–783. [CrossRef] [PubMed] 8.

Current ERC Guidelines. Available online: https://cprguidelines.eu/ (accessed on 31 January 2024). 9.

Prabakaran, S.; Slappy, R.; Merchant, F. Supraventricular Tachycardia. In Handbook of Outpatient Cardiology; Springer International

Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 409–422. 10.

Xiao, L.; Ou, X.; Liu, W.; Lin, X.; Peng, L.; Qiu, S.; Zhang, Q. Combined Modified Valsalva Maneuver with Adenosine

Supraventricular Tachycardia: A Comparative Study. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 78, 157–162. [CrossRef] [PubMed] 11.

Kotadia, I.D.; Williams, S.E.; O’Neill, M. Supraventricular Tachycardia: An Overview of Diagnosis and Management. Clin. Med.

2020, 20, 43–47. [CrossRef] [PubMed] 12.

Littmann, L.; Olson, E.G.; Gibbs, M.A. Initial Evaluation and Management of Wide-Complex Tachycardia: A Simplified and

Practical Approach. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 37, 1340–1345. [CrossRef] [PubMed] 13.

Narasimhan, B.; Gandhi, K.; Moras, E.; Wu, L.; Da Wariboko, A.; Aronow, W. Experimental Drugs for Supraventricular

Tachycardia: An Analysis of Early Phase Clinical Trials. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2023, 32, 825–838. [CrossRef] [PubMed] 14.

Ebrahimi, R.; Rubin, S.A. Electrical Cardioversion Resulting in Death from Synchronization Failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 1994, 74, 100–102. [CrossRef] [PubMed] 15.

Xavier, L.C.; Memon, A. Synchronized Cardioversion of Unstable Supraventricular Tachycardia Resulting in Ventricular Fibrilla-

tion. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2004, 44, 178–180. [CrossRef] [PubMed] 16.

Kaufmann, M.R.; McKillop, M.S.; Burkart, T.A.; Panna, M.; Conti, J.B.; Miles, W.M. Iatrogenic Ventricular Fibrillation after

Direct-Current Cardioversion of Preexcited Atrial Fibrillation Caused by Inadvertent T-Wave Synchronization. Tex. Heart Inst. J.

2018, 45, 39–41. [CrossRef] [PubMed] 17.

Gallagher, M.M.; Yap, Y.G.; Padula, M.; Ward, D.E.; Rowland, E.; Camm, A.J. Arrhythmic Complications of Electrical Cardiover-

sion: Relationship to Shock Energy. Int. J. Cardiol. 2008, 123, 307–312. [CrossRef] [PubMed] 18.

Sucu, M.; Davutoglu, V.; Ozer, O. Electrical Cardioversion. Ann. Saudi Med. 2009, 29, 201–206. [CrossRef] [PubMed] 19.

SIMS, J.J.; MILLER, A.W.; UJHELYI, M.R. Regional Hyperkalemia Increases Ventricular Defibrillation Energy Requirements. J.

Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol 2000, 11, 634–641. [CrossRef] [PubMed] 20.

Page, R.L.; Joglar, J.A.; Caldwell, M.A.; Calkins, H.; Conti, J.B.; Deal, B.J.; Estes, N.A.M.; Field, M.E.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Hammill,

S.C.; et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Management of Adult Patients With Supraventricular Tachycardia: Executive

Summary. Circulation 2016, 133, e471–e505. [CrossRef] [PubMed] 21.

Osmonov, D.; Erdinler, I.; Ozcan, K.S.; Altay, S.; Turkkan, C.; Yildirim, E.; Hasdemir, H.; Alper, A.T.; Cakmak, N.; Satilmis, S.; et al.

Management of Patients with Drug-Induced Atrioventricular Block. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2012, 35, 804–810. [CrossRef] [PubMed] 22.

Doukky, R.; Bargout, R.; Kelly, R.F.; Calvin, J.E. Using Transcutaneous Cardiac Pacing to Best Advantage: How to Ensure

Successful Capture and Avoid Complications. J. Crit. Illn. 2003, 18, 219–225. [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual

author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to

people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

Document Outline

- Introduction

- Case Presentation

- Discussion

- Conclusions

- References