Preview text:

lOMoARcPSD|364 906 32

Context Effects on Consumer Choice

Rational choice theory suggests that consumer choices and preferences should be independent of

the context. As a simple example, it is assumed that consumers will evaluate a $5 discount the

same way regardless of context. However, this is not the case. Consumers tend to perceive the

value of the $5 discount as higher when it is on a product originally priced at $10 and lower on a

product originally priced at $100. The reason goes back to Chapter 8 and relative preferences.

Consumers appear to evaluate the $5 savings in the context of or relative to the original price of the product.

In a similar way, consumers are affected by the competitive context in which they make choices,

or what we referred to in Chapter 13 as the purchase situation. There are numerous context

effects on consumer choice. Here we will discuss two, the center-stage and decoy effects. These

effects may occur when a consumer faces a choice from three alternatives.³⁸

Center-stage effect: Where a product is physically located has an influence on preference for that

product. If choosing among three options, we tend to prefer, and choose, the one that is

physically positioned in the middle. This center-stage effect has been shown to occur in many

and varied situations including seating (71 percent choose to sit in the middle of three chairs), as

well as with the purchase of chewing gum (50 percent choose the middle of three packs). One

reason this may occur is that we tend to choose what we visually attend to, and it appears that we

tend to look first/most at items in the center. Gas stations have applied the center-stage effect to

increase sales of premium (the most expensive) gas by placing this option in the middle of the

two lower-priced options on the gas pump. Note how with the gasoline choice situation, the

center-stage effect is independent of attribute levels (e.g., quality, price) or the weights

consumers might attach to them but is, rather, a function of a completely other attribute (physical

location of the pump), which is irrelevant to the characteristics of gasoline, which therefore

violates rational choice theory.

Decoy effect: The decoy effect involves placing a third and clearly inferior brand into the choice

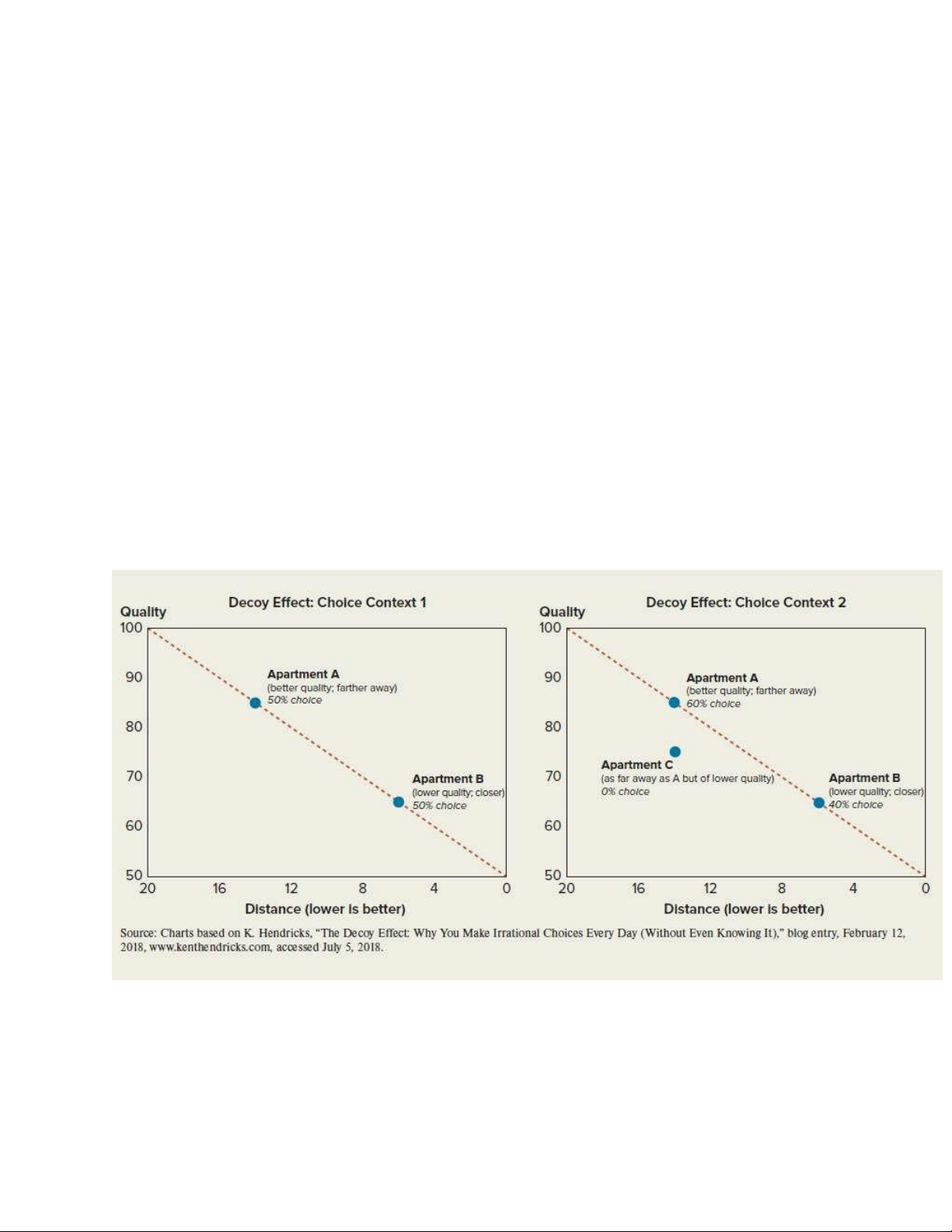

set to influence choice outcomes. We begin with Decoy Effect: Choice Context 1 (left graph), in

which there are two apartments (A and B) evaluated on two attributes (distance from campus in

miles and quality on a 1–100 scale where 100 is best). As the graph on the left shows, option A

is further from campus (a negative) but of higher quality (a positive), while option B is nearer to

campus (a positive) but of lower quality (a negative). In addition, because some consumers care

about quality more than distance and some are just the opposite, assume that the choice

percentages between A and B are split equally (50 percent choose A and 50 percent choose B).

Now consider Decoy Effect: Choice Context 2 (right graph). Here an apartment option is added

(Apartment C) that is clearly inferior to Apartment A (that is, Apartment A is said to dominate

C). An important point here is that Apartments A and B have not changed at all. Only the context

of choice has changed because a third option was added that is obviously inferior to Apartment A

and not obviously better than Apartment B. Rational choice theory would say that an irrelevant

choice option should not change a consumer's original choice. In this case, Apartment C should

be irrelevant. Those who chose A previously should never choose C because C is clearly inferior

(same distance as A but of lower quality). Those who chose B previously should still prefer B

because it is better than C on their more preferred attribute, namely distance. However, this is not

what happens. Instead, the addition of the decoy (Apartment C) appears to make it easier for

consumers to see how B is better than C, but it does not make it obvious that B is A better than

A. As a consequence, adding the "irrelevant" option of Apartment C triggers Apartment A’s

choice or market share to increase by pulling market share from Apartment B. In a sense, the

decoy "attracts" consumers to Apartment A, and it does so even if no one chooses the decoy, as shown in the figure.

Marketers can utilize these and other “contextual” factors to influence consumer choices and can

do so in such a way to move consumers "toward" the options they most want consumers to select

and "away" from options they might otherwise select. You might wonder how it is possible that

choice context can matter so much. One explanation, according to consumer choice expert Dan

Ariely, is that “we [as consumers] actually don’t know our preferences that well, and because we

don’t know our preferences that well, we’re susceptible to all the influences from external forces.” Critical Thinking Questions

1. Why do the center-stage and decoy effects contradict rational choice theory?

2. Besides typically looking first at the center of the screen, can you think of other reasons why

consumers prefer middle options on websites?

3. Do you see any ethical issues related to strategies designed to position brands against decoy alternatives? Explain.