Preview text:

Le, H.T., Dang, D.T., & Tran, H.P. – A Grammar of the English language 4. GRAMMATICAL UNITS

The first step usually taken in the study of grammar is to identify units in

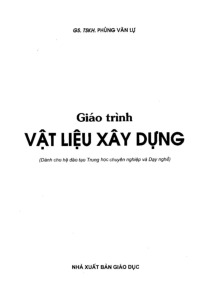

the stream of speech (or writing, or signing) - The following five-rank

hierarchy is a widely used model in the study of grammar: SENTENCES SENTENCES are analyzed into are used to build CLAUSES CLAUSES are analyzed into are used to build PHRASES PHRASES are analyzed into are used to build WORDS WORDS are analyzed into are used to build MORPHEMES MORPHEMES

Morphemes are the ''lower'' limit of grammatical enquiry, for they have

no grammatical structure. Similarly, sentences form the ''upper'' limit of

grammatical study, because they do not usually form a part of any larger grammatical unit.

Part IV will deal with the definitions of these five grammatical units and discussion round them.

4.1. MORPHEMES AND WORDS

In traditional grammar, words are the basic units of analysis.

Grammarians classify words according to their parts of speech and identify

and list the forms that words can show up in. As you can easily see, many

words in the English language have no internal grammatical structure. These

words (e.g., yes, boat, car, head, etc.) can be analyzed into constituent sounds

or syllables but none of these has a meaning in isolation.

Le, Dang, & Tran (2015) A Grammar of the English language. ĐH HN Page 1

Le, H.T., Dang, D.T., & Tran, H.P. – A Grammar of the English language

By contrast, many words can be divided into parts, each of which has

some kind of independent meaning. The smallest meaningful elements/units

into which words can be analyzed are known as morphemes; and the way

morphemes operate in language provides the subject matter of morphology.

Although speakers of English probably know more about words than

any other parts of their language, words are extremely difficult entities to

define in either universal or language-specific terms. Like most linguistic

entities, they are Janus-like. They look in two directions - upward toward

phrases and sentences and downward toward their constituent morphemes.

Therefore, a better way to understand words is to study how they are divided

into smaller elements, or, in other words, how they are formed. Word-

building (or word-formation) will be discussed later in this section.

Free and bound morphemes

As mentioned above, words can be analyzed into morphemes, the

smallest grammatical meaningful units. You may observe that some

morphemes can stand alone as independent words since they carry full

semantic weight. These are called free morphemes:

E.g., care in careful, happy in unhappiness, order in disorder, etc.

However, many morphemes cannot stand alone in the language. They

are bound morphemes which only add the meaning or grammatical function

of a free morpheme, and cannot stand alone; e.g.,-ful in careful, un- & -ness

in unhappiness, dis- in disorder, etc.

Allomorphs: Any of two or more alternative forms of a unit of meaning

(eg. The morpheme –es in benches and the –s in hats) that vary with its

environment. Morphemic variants are allomorphs. They are the same

morpheme but they vary in pronunciation and/or spelling, such as the /t/ in the

word worked, the /d/ in the word listened and the /id/ in the word added and

the variants in the following words: reader/visitor/liar.

Roots, Stems, Bases and Affixes

Le, Dang, & Tran (2015) A Grammar of the English language. ĐH HN Page 2

Le, H.T., Dang, D.T., & Tran, H.P. – A Grammar of the English language

Besides being free or bound, morphemes can also be classified as root,

stem, or affix. A root morpheme (or root) is the basic form to which other

morphemes can be attached. In English most roots are free morphemes, but

not all. For instance, the words chronology, chronic, and chronograph all

contain the root chron- (meaning, basically, ''time''), which is not free, but

bound, because it never occurs alone as a word. Similarly renovate and novice

contain a bound root nov- (meaning, basically, ''new'').

Stems are also forms to which other morphemes can be attached. Stems

differ from roots in that they may be made up of more than one morpheme.

All roots are stems, but many stems are not roots (but contain them). Stems

are sometimes created by the juxtaposition of two roots in a compound. Both

baby and sit are roots (and stems), but baby-sit is a stem (but not a root)

because -er can be attached to it. Stems can also be formed by adding

meaningless elements to certain roots. The -n- in binary and trinity is one

such stem-forming element, attached to the roots bi- ("two") and tri- ("three").

Another is the -o- in chronograph and chronology. These stem-forming

element are not morphemes because by ‘morphemes we mean ''smallest unit

with a meaning''. Stem-formers have no meaning or grammatical function.

They are present only for phonological reasons. Base or base form:

(1) The basic or uninflected form of a verb. This is also called ‘base

form’. Go, like, sing, eat are all bases or base forms, in contrast to: went, likes,

sung, ate which are not. This is applied to verbs only.

The base form of a verb functions:

a/ non-finitely, as the infinitive (eg.: You must go/ She can speak/ We

should do it carefully)

b/ finitely: + as the imperative (eg.: Listen! / Be quiet. / Have a biscuit. /

Come on. / Hurry up.)

+ as the present indicative tense for all persons other than the third – 3rd

person singular (eg.: I always listen as opposed to He always listens / I teach

English as opposed to She teaches English, (the verb be is an exception to this).

Le, Dang, & Tran (2015) A Grammar of the English language. ĐH HN Page 3

Le, H.T., Dang, D.T., & Tran, H.P. – A Grammar of the English language

+ as the so-called present subjunctive (eg.: They insisted that he listen. /

The boss demanded that nobody be absent from the company’s meeting.).

(2) The base or base form is used as an element in word formation

a/ The terminology of word formation is confused. Many words consist

of an irreducible ‘core’ word (a free morpheme) to which one or more affixes

(bound morphemes) are attached, eg.: sing + s = sings, great + er = greater,

great + ly = greatly, infect + ious = infectious, in + discrete = indiscrete.

Such basic core words as elements in larger words may be called base

morphemes, but are more often called roots (or stems).

b/ Another type of word when stripped of an affix is no longer a

complete word, but a ‘bound morpheme’. Eg.: Gratuitous apparently has the

suffix –ous (compare: pompous, montrous, outrageous, famous, dangerous,

……), just as gratuity has a noun suffix –y but there is no word *gratuit. Such

a form may be termed a base (or a base morpheme) in some systems. (But

the term stem and root are also used.)

c/ A different problem arises with a word such as unanswerable. It

clearly consists of the prefix un-, the word answer, and the suffix –able. But

we do not have the word: *unanswer; we can only attach un- to answerable.

Some linguists therefore specifically reverse the term base for a word such as

answerable in the context of unanswerable. In this usage, a base is not as

basic as the ‘core’ element (here: answer). But other linguists use stem as the

label here, possibly also including forms such as: gratuit-

Affix is a general term for prefix and suffix, which are both bound

morphemes. Prefixes are morphemes added before a word to form a new

word. Suffixes are morphemes added after a word in the formation of a new word.

One complication in morphological structure is the existence of infixes.

An infix is a bound morpheme occurring right inside another morpheme,

unlike the other affix types, prefixes and suffixes. In English, there are no

infixes, but they are not uncommon in the languages of the world. English has

some morphological phenomena which at first glance look like infixation, but

are better described otherwise. Plurals like "geese" for "goose" and "feet" for

"foot" do not contain infix morphemes, despite appearances, because [gs] and

[ft] are not morphemes. Rather, what English has in words like these is the

result of a replacement process, a kind of morphological irregularity (cases

Le, Dang, & Tran (2015) A Grammar of the English language. ĐH HN Page 4

Le, H.T., Dang, D.T., & Tran, H.P. – A Grammar of the English language

like speedometer, spokeswoman, fisherman, or abso-blooming-lutely in abso-

blooming-lutely awful, etc., are advised to be seen in the same direction.)

''Lexical'' and ''grammatical'' morphemes

Lexical morphemes express meanings that can be relatively easily

specified by using dictionary terms or by pointing out examples of things,

events, or properties which the morphemes can be used to refer to: tree, burp,

above, red, pseudo-, anti, -ism, honest. Grammatical morphemes have one

(or both) of two characteristics. First, they express very common meanings,

meanings which speakers of the language unconsciously consider important

enough to be expressed very often. Verb tense morphemes are an example. In

Max played and Max loves donuts, -ed and -s are grammatical morphemes.

Another example is morphemes expressing noun number (singular vs. plural).

The other characteristic that grammatical morphemes may exhibit is the

expression of relations within a sentence (instead of denoting things,

properties, or events in the world). The verb suffix -s for third person singular

present tense, for example, besides indicating tense, marks 'agreement' between subject and verb.

The definition of ''grammatical morpheme'' is disjunctive: any morpheme

is ''grammatical'' if it fits either (or both) of the two characteristics: (1) It

expresses a very common meaning or is specifically required in some context;

or (2) it expresses a relation within a sentence rather than denoting things,

activities, etc., in the world.

Some of the most commonly used grammatical morphemes in English

are bound: for example, -s, -ed, -ing, -er, -est. Others are free, that is,

independent words. A few examples of free grammatical morphemes are the,

passive by, as in ...as...as..., to before infinitive verbs. Free grammatical

morphemes are also called function words.

Inflection and derivation

Le, Dang, & Tran (2015) A Grammar of the English language. ĐH HN Page 5

Le, H.T., Dang, D.T., & Tran, H.P. – A Grammar of the English language

Another useful morphological distinction is between two kinds of bound

morphemes: inflectional and derivational. Roughly speaking, a derivational

morpheme creates - ''derives'' - a new word when attached, while an

inflectional morpheme creates a new form of the old word.

Inflectional morphology and derivational morphology are two main

fields traditionally recognized within morphology. Inflectional morphology

studies the way in which words vary (or inflect) in order to express

grammatical contrasts in sentences, such as singular/plural or past/present

tense. Thus, morphemes like -s in boys, -es in potatoes, -ies in lorries or -es in

'He goes to school every day’, went from go are called inflectional morphemes.

Altogether, there are only eight inflectional affixes (all suffixes) in

English: plural (-s and its irregular variants, e.g., as in men); -'s (possessive); -

s (verb suffix for third person singular present tense); -ing (verb suffix

meaning ‘in progress’); -er (comparative); -est (superlative suffix); 'perfect'

suffix on verbs (-en, and variants, e.g., as in put and gone); and past tense (-ed

and irregular variants, e.g., as in bought and ate).

Derivational morphology, however, studies the principles governing the

construction of new words, without reference to the specific grammatical role

a word might play in a sentence. In the formation of drinkable from drink, or

taxation from tax, for example, we see the formation of different words, with

their own grammatical properties. Elements that are added to a word to form

new word(s) are called derivational morphemes. A more traditional term for

derivational morphemes is affixes (prefixes and suffixes). Actually, affixation

(or derivation) including prefixation and suffixation is a productive way to form new words in English.

Other ways of forming new words

Like all other languages in the world, English changes, new words are

created through a variety of creative mechanisms. Besides derivation,

important processes include compounding, conversion or ''zero-derivation''

(eg.: hand(n) – to hand(v)/ water(n) – to water(v)/ dog(n) – to dog(v)/

empty(adj) – to empty(v)……….), the use of acronyms, extending brand

Le, Dang, & Tran (2015) A Grammar of the English language. ĐH HN Page 6

Le, H.T., Dang, D.T., & Tran, H.P. – A Grammar of the English language

names to the realm of common nouns, ''blends'', ''clippings'', and extending the

domain of derivational morphemes.

(1). Compounding/Composition

There are new words in English which are produced by combining two

or more roots or stems. Compound words, though certainly fewer in quantity

than root words or derived words, still represent one of the most typical and

specific features of English word-structure. There are different kinds of

compound words. Structurally, there are neutral compound words (eg. White- board, table-tennis, warm-hearted, TV programme, U-bomb,…),

morphological compound words ( eg. Salesgirl, handicraft, speedometer,

agro-forestry,…) and syntactical compound words (eg. Merry-go-round, good-for-nothing, forget-me-not, know-what,

one-know-everything,…).

Semantically, there are idiomatic compound words (eg. Red-tape, lady-bird,

green-fly, blue-bottle,…) and non-idiomatic compound words (eg. School-

boy, man-doctor, toy-train, room-mate, white-board-marker, ceiling- fan,…).

Words like football, handbook, toothpick, White House, and lawn mover

are compounds, which can be defined as words containing at least two roots.

As you can see, compounds are sometimes spelled as single words,

sometimes as word sequences. The meanings of a compound aren't always

predictable from the meanings of its constituents, and therefore, dictionaries

provide individual entries for compounds. For instance, girlfriend means

more than just a friend who is a girl, sweetheart relies on metaphor to relate

its form and its meaning, overlap can denote only a state, never an event (an

overlap exists rather than happens), a firing squad is not just a squad that

fires, but one that executes by firing, sandpaper has a narrower meaning than

just ''paper with sand (on it), and both bag man and bag lady mean more than 'man (woman) with a bag''.

A list of English compounds 1. Compound nouns

a. Noun + Noun: bath towel; boyfriend; death blow

b. Verb + Noun: pickpocket; breakfast

c. Noun + Verb: nosebleed; sunshine

d. Adjective + Noun: deep structure; fast-food e. Verb + Verb: make-believe

f. Particle + Noun: in-crowd; downtown

Le, Dang, & Tran (2015) A Grammar of the English language. ĐH HN Page 7

Le, H.T., Dang, D.T., & Tran, H.P. – A Grammar of the English language

g. Adverb + Noun: now generation

h. Verb + Particle: cop-out; dropout

i. Phrase compounds: son-in-law 2. Compound verbs a. Noun + Verb: skydive

b. Adjective + Verb: fine-tune c. Particle + Verb: overbook d. Adjective + Noun: brownbag 3. Compound adjectives

a. Noun + Adjective: card-carrying; childproof

b. Verb + Adjective: fail-safe

c. Adjective + Adjective: open-ended

d. Adverb + Adjective: cross-modal

e. Particle + Adjective: overqualified f. Noun + Noun: coffee table g. Verb + Noun: roll-neck

h. Adjective + Noun: red-brick; blue-collar i. Particle + Noun: in-depth

j. Verb + Verb: go-go; make-believe

k. Adjective/Adverb + Verb: high-rise

l. Verb + Particle: see-through; tow-away 4. Compound adverbs Up-tightly cross-modally 5. Neoclassical compounds

astronaut; hydroelectric; mechanophobe

(2). Conversion (Zero-derivation)

A word changes its class without any change of form, e.g., carpet

becomes to carpet; hand becomes to hand, eye – to eye, back – to back, face –

to face, comb – to comb, pen – to pen, brush – to brush, room – to room, table

– to table, lunch – to lunch, cook – to cook, nurse – to nurse, dog – to dog,

Le, Dang, & Tran (2015) A Grammar of the English language. ĐH HN Page 8

Le, H.T., Dang, D.T., & Tran, H.P. – A Grammar of the English language

monkey – to monkey, fish – to fish, whale – to whale, bottle – to bottle, honey-

moon – to honey-moon, yellow – to yellow, … . (3). Acronymy

Another word-formation process turns word-initial letter sequences into

ordinary words: laser from light amplification by stimulated emission of

radiation, NATO from North Atlantic Treaty Organization, WTO from World

Tourism Organization, UNICEF from United Nations International

Children’s Educational Fund, FAQ from frequently asked questions, CD-

ROM from Compact Disc read-only memory, radar from radio detecting and ranging, etc.

(4). Brand names

This word-formation process turns brand names into common nouns,

sometimes verbs: kleenex, xerox (n, v), scotch tape. (5). Blendings

Two words merge into each other, e.g., brunch (breakfast + lunch),

Chunnel (Channel + tunnel), telex (teleprinter + exchange), and motel (motor

+ hotel), smog (smoke + fog), bit (binary + digit), Eurovision (European +

television), cyborg (cybernetic + organism), … . (6). Clippings

This process creates an informal shortening of a word, often to a single

syllable, e.g., ad, gents, flu, telly, phone, bus, lab, gas, maths, pants,… .

(7). Extending the domain of derivational morphemes

Another word-formation process is making a derivational morpheme

more productive than it was. One frequently criticized example of this is the

extension of -ize to create forms such as prioritize and containerize. This kind

of word-creation is found frequently in a child's first language acquisition. 4.2. PHRASES

Le, Dang, & Tran (2015) A Grammar of the English language. ĐH HN Page 9

Le, H.T., Dang, D.T., & Tran, H.P. – A Grammar of the English language

A phrase is a level of structure between a word and a clause. In both

traditional and more modern grammar a phrase often consists of two or more

words that ‘go together’, eg. at the beginning, very young indeed, in the

classroom. However, in traditional grammar (where a clause must contain a

finite verb) phrases include what are now often classified as non-finite clauses

(eg. having said that) or verbless clauses (eg. if possible). In modern grammar

phrases are still defined in terms of form. But a phrase can consist of a single

head-word; it could also contain a finite clause if that is dependent on the head-word.

A phrase is an element of structure typically containing more than one

word, but lacking the subject-predicate structure usually found in a clause.

Phrases are classified into functional types related to word class, such as noun

phrases, verb phrases, adjective phrases, adverb phrases and preposition

phrases. In generative grammar, the term has a broader sense as part of a

general characterization of the first stage of sentence analysis – the phrase-

structure part of a grammar.

Traditionally, phrases are an extension of the single word parts of speech

named accordingly: noun phrase, adjectival phrase, and adverbial phrase. The

traditional definition of a phrase calls it ''a group of words that does not

contain a verb and its subject and is used as a single part of speech''.

Phrases are not introduced by conjunctions, nor do they contain a finite

verb (i.e., a verb which is inflected to show tense). In fact the phrase is

traditionally defined as a cohesive group of words containing no finite verb

but making a unit that functions as part of a sentence (Ridout and Christie,

The Fact of English, 1963).

This traditional definition employs three different criteria: semantic (''a

cohesive group of words''); structural (''containing no finite verb but making a

unit''); and functional (''functions as part of a sentence''). A phrase, following

the definition given above, functions as a coherent entity within the sentence.

A look at the phrases in the examples below, and the words with which these

phrases could be replaced, will suggest that this function is in essence the

same as that of various parts of speech (Noun, Adjective, Adverb):

Le, Dang, & Tran (2015) A Grammar of the English language. ĐH HN Page 10

Le, H.T., Dang, D.T., & Tran, H.P. – A Grammar of the English language

Eating at restaurants gives me indigestion. (as a noun; subject of the sentence)

The cat ran under the chair. (as an adverb of place)

The jacket with a striped pattern is mine. (as an adjective; part of a longer noun phrase)

Despite appearances, Mary is not at all a shy person. (as a sentence adverb)

He ate his sandwiches with great delight. (as an adverb of manner) Note:

Sometimes the function of the phrase is doubtful:

I like the vase on the table.

a) I like the vase which is on the table. (an adjectival phrase)

b) I like the vase to be on the table. (an adverbial phrase)

Phrases are essentially a means of expanding the vocabulary potential of

English by giving us a far wider range of Nouns, Adverbs, etc. So phrases, as

we have said before, are an extension of the single-word parts of speech.

The phrase as a verb:

A verb phrase (VP) always contains a main verb as its head. It can be a

single word (eg. spoke, told) or it may also contain one or more auxiliary

verbs (eg. must have been leaving). A finite verb phrase always functions as

the verbal element (V) in finite clause structure.

The phrase as a noun:

A noun phrase (NP) contains a noun as head – with or without

modification. A noun phrase may contain a relative clause in some modern

analysis (eg. the woman I love).

Le, Dang, & Tran (2015) A Grammar of the English language. ĐH HN Page 11

Le, H.T., Dang, D.T., & Tran, H.P. – A Grammar of the English language

The phrase as adjective:

The adjective (or adjectival) phrase (Adj) is usually distinguished from

the other types by virtue of its modifying a noun, i.e., in functional terms. In

practice, this means that an adjectival phrase nearly always occurs as a

modifier of the head noun within a noun phrase:

The man on the bench is drunk.

People in poor countries often suffer from malnutrition.

Because of the strict placing in English of the adjectival phrase after the

noun it modifies, misplacement of the phrase can give rise to amusing or

misleading misinformation, as in the advertisement below:

‘Wanted, zinc bath for adult with strong bottom.’

‘Sports leather coat for lady in perfect condition.’

The phrase as adverb:

Structurally, the adverb (or adverbial) phrase is identical with the

adjectival phrase (both are begun with a preposition), but its position in the

sentence is usually different. The major difference between the two types of

phrase lies in their functions: whereas the adjectival phrase modifies a noun,

the adverbial phrase modifies a verb, and can usually be replaced by a single- word adverb:

The assailant struck the man behind the ear.

The assailant struck the man behind the railway station.

The lecture begins at one o'clock.

They treated the suggestion with little respect.

She did it for no particular reason.

Le, Dang, & Tran (2015) A Grammar of the English language. ĐH HN Page 12

Le, H.T., Dang, D.T., & Tran, H.P. – A Grammar of the English language

Phrase as a preposition:

A preposition (or prepositional) phrase (PP) is rather different from the

other four types of phrases. In form, they are non-headed, and must contain at

least two words – a preposition plus its object (or complement), usually a

noun. Preposition phrases have two main functions. They can be the

adv(erbial) in clause structure (eg. please put that in the box) or they can

operate at a lower level as part of a noun phrase (eg. a Jack-in-the box)

Most phrases can be seen as expansions of a central element (the head),

and these are often referred to as "endocentric" phrases (also as basic

phrases). They have the same grammatical function as the central word or the head: cars the cars the big cars all the cars big all the cars in the garage big

Phrases which cannot be analyzed in this way are then called "exocentric": inside / the cars.

The internal structure of an endocentric phrase is commonly described in a three-part manner: all the big cars in the garage PREMODIFIER HEAD POSTMODIFIER

Le, Dang, & Tran (2015) A Grammar of the Enlish language. ĐH HN Page 13

Le, H.T., Dang, D.T., & Tran, H.P. – A Grammar of the English language

As mentioned above, the head is the central element of a phrase. It is the

required lexical constituent in the phrase. In modern grammars it is the head

that gives the phrase its identity.

According to contemporary syntax, any phrase may be one or more

words long, e.g., a noun phrase includes either a single noun or a group of

words that functions like a single noun. The key syntactic notion of function

is bought into focus in order to define the phrase in a way that it makes the

study of grammar simpler (although it can confuse those who aren't aware of

this practice in contemporary syntax.) One consequence of this change is that

it appears to any single word into a phrase and thus to destroy the distinction

between words and phrases that the traditional definition maintains clearly. In

fact, this problem doesn't arise, for only five phrase types will be defined in

English, each of which will have only a certain range of parts of speech that

normally function as phrasal heads.

In considering word classes (or parts of speech), contemporary syntax

classifies English phrases into: (1) Noun Phrase (NP):

Functional formula: (Pre-modifier) + Head + (Post-modifier)

Examples of noun phrases can be:

(a) I love coffee; Pandas live in southwest China [Head alone]

(b) The pandas died; Her nose is straight [Pre-modifier + Head]

(c) arguments about abortion; printers of good quality [Head+ Post-modifier]

(d) the decision on national security

[Pre-modifier + Head + Post-modifier] (2) Verb Phrase (VP): Functional formula:

(Auxiliary) + Head + (Object/Complement) + (Modifier) Examples of verb phrases are:

Le, Dang, & Tran (2015) A Grammar of the English language. ĐH HN Page 14

Le, H.T., Dang, D.T., & Tran, H.P. – A Grammar of the English language

(a) Mr. Truong walks; Everybody dies [Head alone]

(b) Mr. Truong is walking; Mr. Truong does not cry [Aux + Head]

(c) Mr. Truong delivered a long speech; Mr. Truong gave me a drink [Head + Object(s)]

(d) Mr. Truong considers grammar a living thing [Head + complement]

(e) Mr. Truong works a great deal; He stays up very late [Head + Modifier]

(f) Mr. Truong has considered grammar a living thing for a long time

[All the above combined]

(3) Adjective Phrase (Adj P):

Functional formula: (Intensifier) + Head + (Complement)

Examples of typical adjective phrases can be seen below:

(a) difficult q u e s t i o n s [Head alone]

(b) very difficult q u e s t i o n s [Intensifier + Head]

(c) aware of the matter [Head + Complement]

(d) aware that humans are destroying the environment [Head + Compl.]

(e) quite aware of the matter [Intensifier + Head + Complement]

(4) Adverb Phrase (AP):

Functional formula: (Intensifier) + Head

Examples of typical adverb phrases appear below:

(a) carefully [Head alone]

(b) very carefully [Intensifier + Head]

(5) Prepositional Phrase (PP):

Functional formula: Head + Object

Examples of typical prepositional phrases can be:

Le, Dang, & Tran (2015) A Grammar of the English language. ĐH HN Page 15

Le, H.T., Dang, D.T., & Tran, H.P. – A Grammar of the English language (a) on the table (b) of good quality

(c) with malice toward none

(d) beyond the blue horizon

(e) from the center of Bombay

In the formula above the heads are a noun, a verb, an adjective, an

adverb, and a preposition respectively. We will not go on with a detailed

discussion on this classification of phrase because of the limited scope of this book.

4.3. CLAUSES and SENTENCES

Syntax, we have said, is concerned with the way words combine to form

sentences. The sentence, as well as being a combination of words, is also

often defined by traditional grammarians as the expression of a complete

thought, which it can only do if it contains both a subject and a predicate. In

the most basic subject-predicate sentence, the subject is that which the

sentence is about, and the predicate is what says something about the subject.

For example, in Quang laughed, Quang is the subject and laughed is the

predicate. Dividing sentences into their parts like this is called parsing in traditional grammar.

A sentence that cannot be subdivided into constituent sentences is

known as a simple sentence. And a complicated sentence contains in it

combined simple sentences. A sentence within a sentence is sometimes called

in modern term an embedded sentence. The traditional term for embedded sentences is clauses.

A clause looks like a complete sentence appearing as part of something

larger which also looks like a complete sentence. Like a sentence, clause must

have a subject and a finite verb.

The various units that make up the structure of a clause are usually given

functional labels, such as Subject (S), Verb (V), Complement (C), Object (O),

Le, Dang, & Tran (2015) A Grammar of the English language. ĐH HN Page 16

Le, H.T., Dang, D.T., & Tran, H.P. – A Grammar of the English language

and Adverbial (A). A number of clause types can be identified in this way, such as: S + V The girl + is dancing. S + V + O The girl + kissed + her dog. S + V + C The girl + is + sick. S + V + A

The girl + lay + on the ground. S + V + O + O

The girl + gave + her dog + a bone. S + V + O + C

The girl + called + her dog + Honey. S + V + O + A

The girl + beat + her dog + yesterday.

S + V + O + C + A The girl + made + him + happy + often.

Clauses are combined in two main ways to form more complex

sentences; they may either be co-ordinated, as when a number of clauses of

equal (grammatical) standing or importance are joined together (e.g., I ate

steamed rice and you ate fried rice.) or one clause may be subordinate to

another, which is known as the main clause. Thus in I ate steamed rice while

you ate fried rice, I ate steamed rice is the main clause to which the rest is

subordinate. In other words, coordination and subordination (also

embedding) are two main ways of making sentence more complex.

Coordination results in sentences known as compound sentences and

subordination results in sentences known as complex sentences.

As mentioned above, the sentence can be defined by traditional

grammarians as a combination of words which expresses a complete thought.

However, modern studies avoid this emphasis because of the difficulties

involved in saying what thoughts are. For example, an egg can be a thought

but not a sentence; I shut the door, as it was cold is one sentence with two thoughts.

Some traditional grammars give a logical definition to the sentence. The

most common approach proposes that a sentence: has a subject (= the topic of

the sentence) and a predicate (= what is being said about the topic). This

approach works well for a great number of sentences but not all. For example,

what is the topic (or topics) in "It is raining and Michael asked Mary for a pen"?

Le, Dang, & Tran (2015) A Grammar of the English language. ĐH HN Page 17

Le, H.T., Dang, D.T., & Tran, H.P. – A Grammar of the English language

Linguistic approaches:

Linguists aim to analyze the linguistic constructions that occur,

recognizing the most independent of them as sentences. Thus a sentence is the

largest unit to which syntactic rules apply - 'an independent linguistic form,

not included by virtue of any grammatical construction in any larger linguistic

form' (L. Bloomfield, 1933, p.170).

Sentences are allowed to omit part of their structure and thus are

dependent on a previous sentence. Sentences of this kind are known as elliptical sentences. A: Where are you going? B: To town.

Further discussion on different types of clauses and sentences will be

found in later parts of the book.

Le, Dang, & Tran (2015) A Grammar of the English language. ĐH HN Page 18