Preview text:

lOMoAR cPSD| 59078336

Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 86 (2025) 104322

Flash sale or continuing Sale? Examining the timing flow of E-tailers’ promotion effects Yiming Zhuang a, Xun Xu b,*

a Department of Management, College of Business, Engineering, and Computational & Mathematical Sciences, Frostburg State University, 101 Braddock Rd, Frostburg, MD, 21532, USA

b School of Global Innovation and Leadership, Lucas College and Graduate School of Business, San Jos´e State University, One Washington Square, San Jos´e, CA, 95192, USA A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Keywords: e-commerce

Fierce competition in the e-commerce landscape compels retailers to leverage price promotions to boost sales. Most of the Promotion timing flow

existing promotion literature investigated the consequence of promotion effects on increasing sales but did not analyze the

Promotion promptness and continuity

process. This study fills this literature gap by discussing the timing flow of e-tailers’ promotion effects. The objective of this

Consumer seniority and experience

research is to examine how the extent of promotion discount affects the promptness and continuity of the promotion effects,

Featured channel and products e-tailers

moderated by consumer seniority and experience, featured products, and featured channels. We collected data from

Woot.com in 2022, a popular United States–based e- tailer that commonly offers discounted products, and used regressions

to analyze the data. Our findings suggest that the discount extent affects the promptness and continuity of the promotion

effect in a U-shaped way. Therefore, an intermediate discount is optimal to achieve the highest promptness and continuity of

the promotion effect. In addition, the timing flow of the promotion effects is moderated by three aspects–consumer, channel,

and product. Consumers’ historical purchase behaviors, reflected by their experience, weaken the promptness of promotion

effects. Furthermore, consumer experience and the featured channel accelerate the continuity of promotion effects. The

featured products weaken the continuity of promotion effects. Our findings yield important managerial implications to guide

e-tailers in leveraging appropriate promotional discounts to attract consumers soon and continuously enhance sales. E-tailers

should also pay attention to the particular consumer segments and the channel and product features to achieve the best timing

flow of the promotion effects. 1. Introduction

From the demand side, consumers are heterogeneous in terms of their online

purchase experience for various reasons, such as information adoption

Retailers are currently using various marketing and operational strategies

willingness and capability, risk preferences, and shopping habits (Li and

to cope with fierce competition to attract consumers and generate more sales

Popkowski Leszczyc, 2024). Thus, e-tailers’ promotional effects may vary

(Guchhait et al., 2024). Price promotions are among the common approaches

among consumers with different online shopping experiences (Lian et al.,

(Wei et al., 2025). In the e-commerce context, this is especially true for e-tailers

2019; Peschel, 2021). From the supply side, e-tailers also often implement

for two reasons. Externally, e-tailers face competition from both the brick-and-

various operational and marketing efforts to improve the effects of online

mortar stores and all other e-tailers without geographical restrictions, causing

promotion (Khouja and Liu, 2020). Understanding the timing flow of

a high level of sales rivalry. Internally, e-tailers have more flexibility to adjust

promotion effects and the corresponding influential factors is important for e-

prices without the cost of reprinting and reposting the price label and can

tailers to implement the appropriate magnitude of price discount and provide

shorten the associated lead time for price changes (Tong et al., 2022). In

the corresponding inventory for the products given the corresponding

addition, price change information can spread more quickly and widely,

prediction of demand pattern based on the price promotion.

facilitated by internet-based information technology (Feng et al., 2021).

However, understanding the timing flow of promotion effects is complex.

One of the important measurements of the timing flow is promotion

promptness (Hochbaum et al., 2011; Spiekermann et al., 2011). Promptness

refers to how quickly consumers act on a promotional offer. A higher level of * Corresponding author.

promotion promptness is meaningful for companies’ success in three aspects.

The literature has proven the positive function of price promotions, with

First, a higher level of promotion promptness shows a higher attractiveness for

the majority focusing on increased sales (e.g., Dai et al., 2022; Drechsler et al.,

promotion. The prompt first response from the promotion helps firms

2017) as the consequence of promotions. However, very few studies have

overcome the challenges reflected by the proverb “The beginning is the most

focused on the process of the promotion effects, namely, the timing flow of

difficult part” and is easy to achieve: “Well begun, half done.” This benefits

promotion effects. Although e-tailers may want to use promotions to attract

firms by enhancing their self-confidence, organizational morals, and

consumers immediately, stimulating a high level of promotion promptness, a

reputation (Greenacre et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2014). Second, a higher level of

continuing demand flow is important for e-tailers to maintain long-term

promotion promptness can cause customers’ herd behavior to follow their

profitability (Hu and Tadikamalla, 2020). In addition, the rapid development of

peer consumers to purchase online, achieving the positive effect of “hunger

e-commerce has various features from both the demand and supply sides.

E-mail addresses: yzhuang@frostburg.edu (Y. Zhuang), xun.xu@sjsu.edu (X. Xu). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2025.104322

Received 14 November 2024; Received in revised form 21 April 2025; Accepted 7 May 2025 Available online 23 May 2025

0969-6989/© 2025 Elsevier Ltd. All rights are reserved, including those for text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies. lOMoAR cPSD| 59078336

Y. Zhuang and X. Xu Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 86 (2025) 104322

marketing” to trigger consumers to perceive the demand is higher than the

effects. E-tailers should leverage the promotion effects based on the property

supply, thus enhancing demand of the promoted products (Ali et al., 2021;

of the channel and product based on our findings.

Zhang et al., 2022). Third, a higher level of promotion promptness indicates

To answer the aforementioned four research questions, we employ

the short return of e-tailers’ effort, as a type of investment, which enhances

signaling theory that interprets price promotion as a signal sent from the e-

their cash flow and financial performance (Vorhies et al., 2009). Thus, our first

tailers to consumers. The data source is from a prominent discount platform:

research question is: How does the e-tailers’ price discount extent affect the

Woot.com, which sells various types of discounted products. We employed

promptness of the promotion effect? Understanding this research question is

regression techniques to find empirical evidence.

important because the intuition is that a higher discount can attract consumers

Our findings suggest that the extent of the discount affects the promptness

more immediately. However, although the larger discount can save consumers

and continuity of the promotion effect in a U-shaped pattern. In addition,

more purchasing costs, it is also possible that the discount, at a certain high

consumer seniority and experience weaken the promptness of promotion

level, may be unfavorably perceived by consumers as an indication of the low

effects. Furthermore, consumer experience and the featured channel

quality of the products or sellers’ eagerness to get rid of the existing inventory

strengthen the continuity of promotion effects. The featured products weaken

(Buil et al., 2013). This trade-off needs to be considered by e-tailers to

the continuity of promotion effects.

determine the optimal discount to attract consumers sooner to achieve a

The findings of our study provide both theoretical and managerial

relatively instant market response and financial return.

implications. Theoretically, our study extends the existing literature about

In addition, the second research question of this study is: how does e-

price promotion effects from the consequence perspective (e.g., Choi et al.,

tailers’ price discount extent affect the continuity of the promotion effect?

2024; Guan et al., 2024; Wei et al., 2025) to the timing flow aspect. Our

Continuity reflects the stability of the sales flow of the prompted products

findings are different from some previous studies that claimed the higher

(Deleersnyder et al., 2004; Forti et al., 2020). The importance of addressing

promotion extents can yield more positive effects on generating sales (e.g., Dai

this research question lies in the fact that although e-tailers may want to use

et al., 2022; Dreschsler et al., 2017) but demonstrate the intermediate

a flash sale to attract consumers in a short time period, a continuing demand

discount is most effective in achieving promptness and continuity of the

flow is important for e-tailers to maintain long-term profitability (Hu and

promotion effects. Our study is also the first to find the moderating factors of

Tadikamalla, 2020). A higher discount may contribute to the continuity of

these effects from a comprehensive framework including three dimensions,

promotional attractiveness due to consumers’ perceived larger benefits.

including consumer, product, and channel perspectives. Managerially, the

However, it may also stimulate consumers’ feelings about the non-specialty of

findings of our study urge e-tailers to take a holistic view of the timing flow of

the promotions, considering the promotions as a normal case (Zhang and

promotion effects, namely, the process of promotion effect rather than simply

Gong, 2023). Therefore, we want to help e-tailers determine the appropriate

the consequence. Our findings guide e-tailers in using intermediate discounts

discount extent to achieve a continuing flow of the promotion effect to

to achieve the promptness and continuity of the promotion effects as a

maintain the positive influence brought by price promotion.

marketing strategy. In addition, e-tailers should pay attention to the consumer

However, the promptness and continuity of promotion effects may depend

segment and their operational efforts to have the featured channel and

on various factors from consumer, channel, and product perspectives.

products accelerate the promptness and continuity of the promotion effects.

Correspondingly, from the consumer perspective, our third research question

The remainder of our paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the

is: how do the various types of consumers with different historical purchasing

relevant literature and elaborates on the theoretical background of this study.

behaviors, reflected by their seniority and purchase experience, moderate the

Section 3 proposes hypotheses. Section 4 presents our methodology, including

promptness and continuity of promotion effects? Understanding the answer

data collection, variable measurements, and analytical approach. Section 5

to this research question is essential because e-tailers’ promotion effects may

presents our empirical results. Section 6 discusses results and the theoretical

vary among various consumers with different online shopping experiences

and managerial implications. Section 7 concludes the study and provides

(Lian et al., 2019; Peschel, 2021). First, various consumers have different levels

directions for future research.

of seniority in terms of their membership. A longer membership can 2. Literature review

strengthen the ties with a provider (Chang et al., 2014) but could also allow

consumers to either value promotions more owing to the stronger attachment

In this section, we first review the relevant literature about promotions.

with the provider or less because of perceived accustomed promotional

Then, we elaborate on the theoretical background of this study.

activities with less excitement. Second, various consumers can have different

purchase experiences, being either new, having no or limited past purchases 2.1. Promotions

from the e-tailers, or being experienced purchasers with rich transaction

records. The purchase experience could also affect the consumer’s perception

Previous studies have discussed various impacts of price promotions, as

of the promotional discount. Therefore, e-tailers should have targeted actions

shown by the following five aspects. These aspects include purchase intention,

for each consumer segment based on their seniority and experience to achieve

sales, revenue and profits, consumer conversion rate, and consumer the best promotion effects.

perception. First, price promotions can enhance consumer purchase intention.

Last, from the channel and product perspectives, our fourth research

For example, using an experimental approach, Büyükdag et al. (2020)˘ found

question is: how do the highlighted channels and products affect the

that price promotion positively affects consumers’ purchase intention.

promptness and continuity of promotion effects? Knowing the answer to this

Second, price promotions have a positive effect on sales increase. For

question is essential because e-tailers also often implement various

example, Dai et al. (2022) found that price promotions can generate more

operational and marketing efforts to improve online promotion effects (Khouja

online sales, whereas price increase reduces online sales. The positive

and Liu, 2020). On the operational side, to better manage inventory and

promotion effects on bumping sales are also demonstrated in Drechsler et al.’s

distribution channels, e-tailers often draw support from a well-known platform

(2017) and McColl et al.’s (2020) study.

for fulfillment, using it as a featured channel and highlighting this information

Third, price promotion can generate more revenue and profit for firms.

on the product’s web page (McKay, 2022). On the marketing side, many

Although the lowered price reduces the marginal profit of the product, the

retailers make efforts to highlight products’ functions and advantages and list

positive promotion effects on revenue and profit were still demonstrated in

them in a featured program (MacDonald, 2021). Both the featured channels

previous research (e.g., Feng et al., 2021; Lin and Bowman, 2022). These

and the products in the featured program (i.e., featured products) may affect

effects are particularly significant for customers with high price and promotion

the aforementioned features of the promotions and the various promotion

sensitivity (Lin and Bowman, 2022). Regarding the detailed approach to lOMoAR cPSD| 59078336

Y. Zhuang and X. Xu Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 86 (2025) 104322

enhance revenue, Feng et al. (2021) built theoretical models to guide the listed

positive externality. Zhang et al. (2021) demonstrated that price promotions

sellers on the platform to implement the optimal promotional pricing

can make consumers feel they have more resources, which ultimately incurs

strategies to maximize the revenue.

the positive social externality that they have more donation behavior. The

Fourth, price promotions have a significant impact on consumers’

positive promotion externality can also be reflected by consumers’ green

conversion rate and engagement. For example, Tong et al. (2022) claimed that

awareness and trust and their green consumption (Guan et al., 2024). The

price promotions increase consumers’ conversion rates. This effect is stronger

effects of the promotion on consumer perception may not be linear. Zheng et

if the platforms serve the reseller mode rather than the marketplace mode. In

al. (2022) found that price promotion has an inverted U-shape effect on

addition, this effect is accelerated if the product has a longer line length. Zhang

consumers’ attribution ambiguity.

et al. (2020) found that price promotions enhance consumers’ engagement on

However, the achievement of promotion effects can be conditional, which

the platform by viewing more product webpages.

is examined in some of the previous research (e.g., McColl et al., 2020; Wei et

Fifth, price promotion affects consumers’ perceptions. Price promotions

al., 2025). For example, Chen et al. (2020) found that the high competition

enhance consumers’ perceived price attractiveness (Büyükdag ˘ et al., 2020).

level of retailers prevents the achievement of a mutual benefit for the

Choi et al. (2024) argued that price discounts can reduce consumers’ guilty

suppliers and e-tailers for their price promotion. Drechsler et al. (2017) found

feelings for hedonic consumption. However, besides the positive effects of

that the effect of price promotion of “X for $Y” on increasing sales is significant

price promotions, the negative effects can also exist. For example, Buil et al.

for utilitarian products but not for hedonic products. McColl et al. (2020)

(2013) found that price promotions reduce consumers’ perceived quality and

showed that the magnitude of the positive promotion effects on sales depends

brand association with the products. In addition, Shaddy and Lee (2020) found

on store size. This result is verified by Sinha and Verma (2020) study to find

that price promotions can trigger consumers’ psychology of reward-seeking

product categories moderate promotion effects. Fong et al. (2019) focused on

and eventually make them impatient. In addition, price promotion can have a targeted Table 1

Literature about the effects of Price Promotions. Authors (Year) Consequence Moderators of Key Findings Subject of Promotion Effects Promotion Effects Drechsler et Sales Product categories Promotion effects on al. sales are stronger for (2017) utilitarian products than hedonic products. Büyükdag ˘ Purchase intention N/A Promotion increases et al. purchase intention. (2020) Shaddy and Impatience N/A Promotion triggers Lee consumers’ reward- (2020) seeking psychology and makes them impatient. Zhang et al. Donation N/A Promotion leads (2021) consumers to feel more resources to have more donation behaviors.

Dai et al. (2022) Online sales Platform types Promotion generates more online sales. However, this effect is different between O2O and traditional B2C platforms. Lin and Revenue and Price sensitivity Promotion enhances Bowman profitability revenue and (2022) profitability, especially for consumers with high price sensitivity. Tong et al. Conversion rate Platform mode and Promotion increases (2022) product line length consumer conversion rate more for the platforms with the reseller mode and for the products with a longer line length. Zheng et al. Attribution N/A Promotion has an (2022) ambiguity inverted U-shape impact on consumers’ attribution ambiguity. Choi et al. Guilty feeling N/A Promotion reduces (2024) consumers’ guilty feelings about the consumption of hedonic products. lOMoAR cPSD| 59078336 Y. Zhuang and X. Xu

Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 86 (2025) 104322 Guan et al. Green trust and N/A Promotion enhances (2024) consumption consumers’ green trust and consumption. Wei et al. Purchase intention Quality cues The promotion effect on (2025) customer purchase intention is moderated by quality cues. This study Promptness and Consumer seniority, The discount extent continuity consumer affects the promptness experience, featured and continuity of the channel, and featured promotion effect in a U- product shaped way. Consumer experience weakens the promptness of promotion effects. In addition, consumer experience and the featured channel accelerate the continuity of promotion effects. Further, the featured products weaken the continuity of promotion effects.

promotions based on the history of individual purchases on an e-book

risk than brick-and-mortar store shopping, owing to the separated processes

platform. They found that the targeted promotions incur costs for crowding

of transaction and fulfillment (Yang et al., 2016).

out consumers’ dissimilar product purchases, although they can increase the

The information posted by e-tailers serves as signals to convey information

sales of the promoted products along with similar products. Wei et al. (2025)

about products and sellers, as an indication of product quality and

empirically tested that the positive promotion effect on customer purchase

specification and sellers’ capabilities and reputation (Rao et al., 2018).

intention is moderated by quality cues and mediated by consumers’ perceived

Signaling theory serves as the main theoretical foundation of this study.

quality. Table 1 summarizes the literature on the effects of price promotions.

Signaling theory refers to a case in which two parties, either individuals or

From Table 1 and the above review of price promotion literature, we can

organizations, have information asymmetry in the environment; one party, as

find that three aspects of literature gaps still exist, which highlight the

the sender, conveys the information to communicate with the other party, with

contributions of this study. First, existing literature on price discount

the expectation that the information is interpreted by this party as the receiver

promotion (i.e., price markdown) (e.g., Choi et al., 2024; Wei et al., 2025)

(Li et al., 2019). At the product level, positive signals can reduce information

focused on the consequences of price promotions without investigating the

asymmetry, motivating consumers to support products, trust sellers, and thus

process of promotion effects, namely, the timing effects of promotions. That

enhance their purchase intentions and behaviors (Mavlanova et al., 2012).

is, it is still unexplored how the consequences are incurred within a timeline

Pricing is one of the most important decisions for e-tailers and is also one

framework. This study fills in this literature gap by examining the timing effects

of the prominent signals perceived by consumers, as well as being among the

of price promotions from two dimensions–promptness and continuity. Second,

key elements for consumers’ purchase consideration (Feng et al., 2021). In this

most existing price promotion research (e.g., Dai et al., 2022; Tong et al., 2022)

study, we focus on the price promotion information posted by the e-tailers.

assumed the higher magnitude of price promotion has a more substantial

According to signaling theory, the key features of signals include

unidirectional effect. In this study, we investigated the nuanced impact of

observability, credibility, and reliability, which affect the effects of price

discounts with the change of the discount magnitude and found extreme

promotion signals. First, the observability of signals refers to the “degree to

discounts may not achieve the strongest effect. Instead, an intermediate

which a signal is easily attended to by an organizational outsider,” which can

discount can have the most significant impact, which can guide e-tailers’

affect signal strength (Drover et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2022). In this study, the

promotion actions. Third, among the price promotion research that discussed

observability of signals is reflected by the magnitude of promotions. Different

the moderating factors, most of them investigated this issue from a single

magnitudes of promotions can be observed from consumers with different

dimension, such as from the perspectives of product (Drechsler et al., 2017),

efforts, which reduces information asymmetry by different levels, making the

platform (Dai et al., 2022), and consumer (Lin and Bowman, 2022). In this

unobservable product information, such as product quality, more indicatable,

study, we examine the moderating factors that affect price promotions from a

influencing consumers’ purchase decisions (Kirmani and Rao, 2000).

comprehensive framework including three dimensions–consumer historical

In addition, the credibility of signals is defined as the combination of a

shopping behavior (i.e., seniority and experience), product (featured product),

signal’s honesty (i.e., the degree to which communicators engage in deception)

and channel (featured channel). In this way, our study can provide a holistic

and fit (i.e., the degree to which the signal accurately reflects the desired

view of the multi-perspective factors that can potentially affect the price

attributes of the signaler) (Connelly et al., 2011). In this study, we focus on the

promotion effect that guides e-tailers to focus on certain aspects to achieve

factors of featured channels and products and investigate how they influence the promotion effects best.

promotion effects. In e-commerce, where physical examination of products is

not possible and the credibility of sellers varies, the information asymmetry 2.2. Signaling theory

between buyers and sellers is particularly pronounced. Therefore, consumers

frequently depend on alternative signals to guide their purchasing decisions.

The delivery of information is key to enhancing consumers’ purchase

Featured channels, known for their reliability and reputation, and featured

intentions and behavior (Onofrei et al., 2022). This is particularly true in the e-

products, distinguished by their endorsement by platforms, act as such signals.

commerce context, which brings both more convenience and higher perceived

The mark of featured channels and products serves as an endorsement from lOMoAR cPSD| 59078336

Y. Zhuang and X. Xu Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 86 (2025) 104322

the platforms to enhance the credibility of the signals, which improves the

3.2. Continuity of promotion effect

strengths of the signals (Bergh et al., 2014).

Furthermore, the reliability of signals shows the magnitude of the reliable

Signaling theory suggests that a high promotion acts as a signal that has a

indicators for the signals (Connelly et al., 2025). A more reliable signal is

high strength to consumers, significantly influencing their perceptions and

perceived more favorably by the receivers, stimulating their decisions based

decision-making processes (Mitra and Fay, 2010). Such promotions can create

on the signals (Taj, 2016). Consumers with different historical purchase

a lasting impression, boosting product sales (Xia et al., 2020), and enhancing

behaviors have different seniority and purchase experiences, which may

product attractiveness, thereby giving products a competitive edge (Singh,

perceive different reliability of the signals because they have experienced

2012). This signal can have a higher level of observability due to the larger

promotions with varying frequencies in the past, affecting their purchasing

discount extent, which thus can persuade consumers to purchase a product

decisions. In this study, we examine the effect of the magnitude of price

even after an intensive online information search for substitutes, extending the

promotion on promptness and continuity, moderated by consumers’ seniority

duration of the promotion effects (Laroche et al., 2003).

and experience and featured channel and product, which thus reflects all of

However, a low discount may also yield higher continuity for the promotion

the three features of signals–observability, reliability, and credibility in

effect. This is because the low discount is not so attractive that consumers signaling theory.

would not worry that the products will be out of stock owing to large sales

(Natter et al., 2007). In addition, consumers have less perceived potential

3. Hypothesis development

regret if they miss a deal owing to a low discount (Liu et al., 2021). Further, the

low discount is less likely to incur clustered purchasing behavior because

3.1. Promptness of promotion effect

consumers’ purchases are more rational or need-oriented, rather than

impulsive (Rajan, 2020). Hence, the low discount may achieve the essence of

The price promotion effect can have different levels of promptness,

the proverb “A steady stream flows long.” Therefore, based on the preceding

depending on the level of the promotion. Price promotions act as

discussion, we propose the following hypothesis:

communicative signals offered by the seller as the signaler to the consumer as

H2. The promotion extent has a U-shaped, curvilinear effect on the continuity

the receiver. These signals vary in strength and can significantly influence

of promotion effects, such that it decreases at low levels of the promotion

consumer perceptions and behaviors. Consumers often conduct a cost-benefit

extent but increases at high levels.

analysis in their shopping process (Lee and Cunningham, 2001). As compared

to a lower level of promotion, a higher level of promotion is a potent signal

3.3. Moderating effect of consumer seniority

that has a higher level of signal observability because it reduces consumers’

purchase cost, thus being more attractive and generating their purchase

From the perspective of signaling theory, promoting a product is a crucial

intentions and behavior, which helps them make their purchase decisions in a

signal that reflects the seller’s marketing strategies and commitment to sales,

shorter time. Consumers thus tend to pay more attention to this promotional

influencing consumer perceptions favorably (Chen, 2018). However,

signal due to this higher signal observability (Sheehan et al., 2019). Further, as

consumers with different tenure on the platforms may have different

a stronger stimulus, a higher price promotion generates consumers’ positive

perceptions of the seller’s brand effect, thus motivating consumers’ intentions

consumption emotions and stimulates impulsive buying behavior (Zielke,

to explore the seller’s online store and other products differently (Feng et al.,

2014). Moreover, consumers are more likely to worry about regrets if they miss

2021). Consumers with different seniority levels have different time durations

a great deal or the products are more likely to be sold out owing to more

with the providers, which affects the tightness and thickness of the buyer-

purchases by other consumers when the promotion is high, and thus they are

supplier relationship (Autry and Golicic, 2010). The seniority level also affects

more likely to view the promotion as a flash sale, rapidly purchasing the

consumer loyalty on the platform. For the new consumers, they may be product (Liu et al., 2021).

enrolled in the platform due to price promotion (Walsman and Dixon, 2020). A

However, an extremely high discount can signal potential negative

higher promotion thus has a higher observability for them to attract more

attributes, leading to consumer skepticism and hesitancy in purchasing. When

purchases from new members owing to increased likelihood of surprise and

the discount is extremely high, consumers may view this signal as less

excitement about the higher discount, increased curiosity about exploring the

favorable because it may indicate that sellers want to get rid of the inventory

online shopping process on the platform, and increased eagerness about

quickly (Chen, 2018). The possible unfavorable reasons could be that the

exploring the benefits of membership (So et al., 2015). Consumers with a

products are approaching their expiration date and are historically unfavored

longer membership period tend to have less impulsive responses to high

by consumers, resulting in low sales. In addition, consumers may have

discounts, viewing the promotional signal as more reliable because they

concerns about the signal credibility, namely, view the signals as trustworthy

perceive the promotions as less unusual than new members might (Goel et al.,

because they may perceive the quality of the product as low, especially when

2022). Thus, highly senior consumers exhibit a weaker acceleration in purchase

the quality is often unobservable online and before consumption (Buil et al.,

timing in response to extreme discounts than newer consumers, which

2013; Kirmani and Rao, 2000). In addition, consumers may perceive the

weakens the promptness of promotion effects. Therefore, based on the above

production and distribution cost of the products skeptical and have concerns discussion, we hypothesize:

about whether additional charges can occur in the purchase, such as shipping

and handling fees in the online shopping environment (Jing, 2011). All of these

H3a. Consumer seniority weakens the promptness of promotion effects.

factors make consumers hesitant to purchase, weakening the price promotion

Consumers with a higher seniority level tend to be more cognitive rather

effect. Therefore, based on the preceding discussion, we propose the following

than emotional when facing promotions (Aydinli et al., 2014). This is because hypothesis:

they have observed the promotions more frequently than the new consumers.

H1. The promotion extent has a U-shaped, curvilinear effect on the

Thus, highly senior consumers tend to view the promotion signal as more

promptness of promotion effects, such that it decreases at low levels of the

reliable because they are more cognitive and have more understanding of

promotion extent but increases at high levels.

online shopping, which makes their buying patterns habits of purchasing

products more established and continuous based on promotions and their

preferences rather than impulsive buying, enhancing the continuity of

promotions. That is, consumers with a higher seniority level extend the

duration of the promotion effects due to their cognition and the more rational lOMoAR cPSD| 59078336

Y. Zhuang and X. Xu Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 86 (2025) 104322

attitude toward the promotions rather than simply exhibiting impulsive buying

3.5. Moderating effects of featured channel

behavior (Karbasivar and Yarahmadi, 2011). Therefore, based on the preceding

discussion, we propose the following hypothesis:

The featured channel, being well-known and reputable (Tong et al., 2022),

acts as a highly credible signal in the e-commerce context. Its prominence and H3b.

Consumer seniority strengthens continuity of promotion effects.

brand effects enhance the visibility and credibility of the signals it sends,

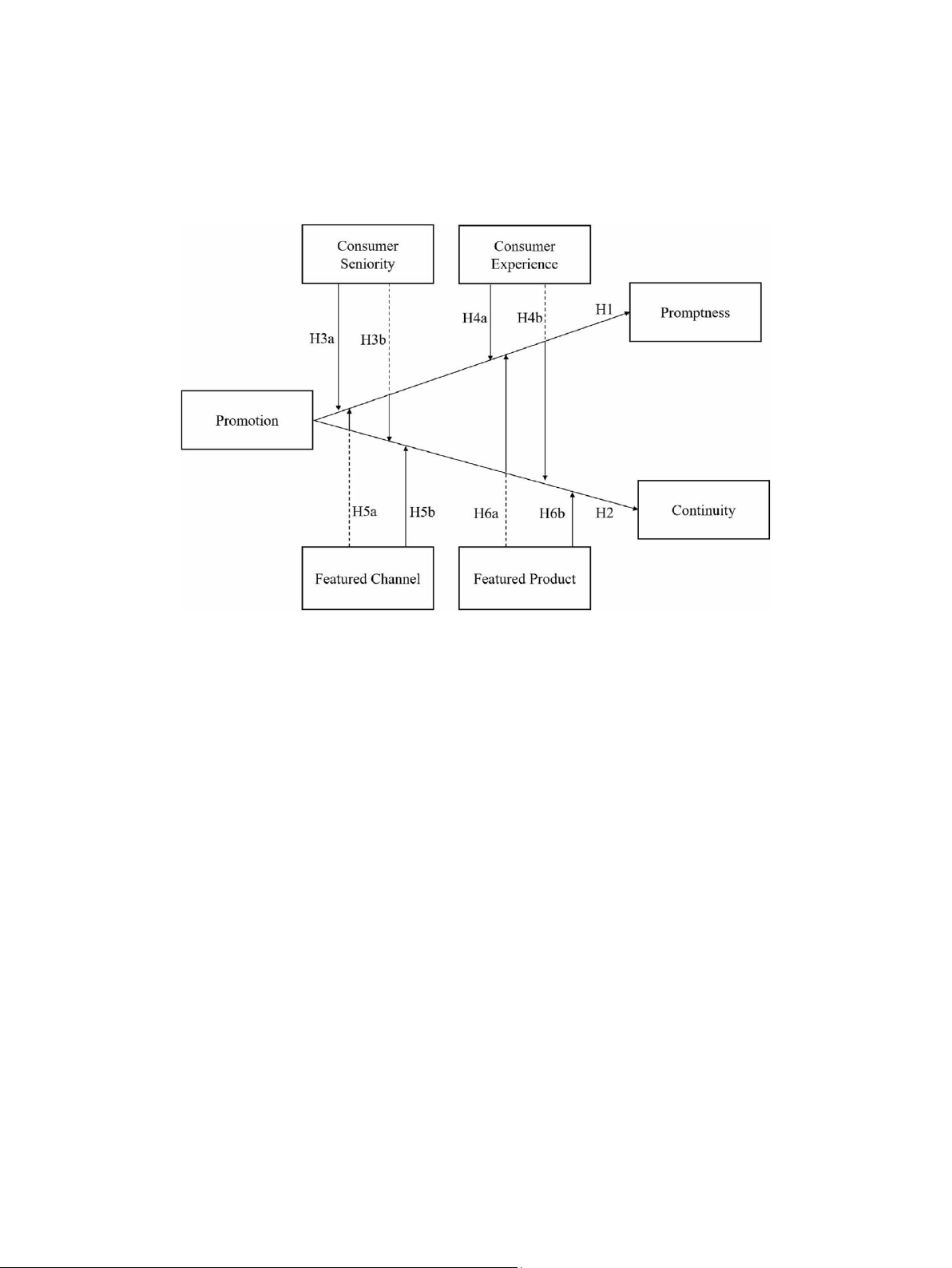

Fig. 1. The conceptual framework of this study.

3.4. Moderating effect of consumer experience

making these signals more easily attended to and valued by consumers. The

consumers thus have a high level of familiarity with the featured channel. It

Consumers with different purchasing experiences may perceive price

often offers an extra guarantee and additional services, which can reduce

promotions differently. An aggressive promotion gives consumers a strong

perceived risk in the e-commerce context, strengthening the signal credibility

signal that has a higher observability of the product’s value, enhancing its

(Vos et al., 2014). Thus, consumers have more trust in the featured channel,

market competitiveness (Singh, 2012). However, this signal not only indicates

valuing it highly (Jiang et al., 2008).

economic savings but also triggers a psychological response, stimulating the

Therefore, when the products distributed by the featured channel are

thrill and satisfaction for consumers derived from making a financially savvy

being promoted, the promotion signal tends to be viewed as having more

choice (Tu et al., 2017). This is particularly true for consumers with less

credibility because the featured channel serves as an endorsement or

historical purchasing experience because they may view the promotion as a

guarantee. The signals that have endorsement or guarantee can thus be

scarce resource and have a higher desire to grasp the opportunity (Wu et al.,

interpreted by consumers more favorably (Shek et al., 2003), leading them to

2021). The existing consumers with mature purchasing experience are more

weigh the signals more and value the promotions more highly. This way, the

likely to carefully consider the various attributes of the products, letting the

promotion effects can increase consumer promptness and continuity.

price play a less significant role in their purchase decisions (Jiang and

Particularly in the online context, consumers typically perceive higher risks

Rosenbloom, 2005). Thus, according to the above discussion, we raise the

than in the physical stores due to the loss of the opportunity to touch and feel following hypothesis:

the products before purchasing (Akram and Lavuri, 2024). Therefore,

consumers tend to find credible signals from the featured channel that are

H4a. Consumer experience weakens the promptness of promotion effects.

especially reassuring. Thus, the featured channel reduces the concerns of

In addition, experienced consumers typically have a clearer understanding

these consumers and strengthens the effects of the promotion. Therefore,

of the product value and more consistent purchasing patterns, which tends to

based on the preceding discussion, we propose the following hypotheses: H5a.

make them perceive promotions less as a stunt and more as a marketing

The featured channel strengthens the promptness of promotion effects.

strategy of the providers (Allender and Richards, 2012). As they have more

H5b. The featured channel strengthens the continuity of promotion effects.

experience, these consumers understand the duration of the promotion better

without too much negative influence from hungry marketing, which worries

about the scarcity of the promotion and the likelihood of stockout of the

3.6. Moderating effects of featured products

products (Zhang et al., 2022). That is, they view the promotion signal as having

higher reliability. Therefore, experienced consumers tend to exhibit a

Price promotions have a higher impact on price-sensitive and price-

continuing purchase flow when viewing the promotions, showing their higher

oriented consumers (Kim et al., 1999). Price typically signals the product

rationality toward the promotions (Li et al., 2023). Based on the preceding

quality, with a higher price indicating a higher production cost, thus signaling

discussion, we hypothesize the following:

a higher quality (Ho et al., 2011). Businesses often invest more effort in

H4b. Consumer experience strengthens continuity of promotion effects.

marketing their featured products (Zhu and Chen, 2015). The featured

products signal the competitive advantages of the products based on their lOMoAR cPSD| 59078336

Y. Zhuang and X. Xu Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 86 (2025) 104322

unique features, higher quality, and added value (Choi and Ahn, 2011). Thus,

included and excluded observations, as category-level patterns would most

consumers who care more about quality with unique features rather than price

likely reveal any non-random missing data mechanisms due to our data favor featured products more.

collection approach via Woot.com’s category-based scraping. The analysis

Therefore, when featured products are on promotion, they align more with

revealed highly similar distribution patterns across both groups. For example,

the needs of quality-oriented consumers rather than price-sensitive

the “Sports” category remained the largest, followed by “Home” and “Tools”

consumers, reducing the attractiveness of these promotions (Drechsler et al.,

in both the included and excluded sets. This consistency provides strong

2017). Therefore, price promotion effects on featured products may not be as

evidence that the missing data pattern is random.

strong as those on non-featured products, which are characterized by lower

In addition, potential concerns may exist regarding reduced statistical

prices and quality that attract price-oriented consumers (Han et al., 2001).

power due to the drop in observations due to missing data. To address this, we

This, in turn, leads to reduced consumer promptness and continuity in

conducted a power analysis to ensure that our final sample size of 1656

responding to the promotions of featured products (Aw et al., 2021).

observations provides adequate statistical power for our analysis. Specifically,

Therefore, based on the preceding discussion, we propose the following

our model incorporates 29 predictors, including main effects (Promotion, hypotheses:

Promotion2), moderators (Seniority, Experience, Channel, Product), interaction

terms, and control variables. The power analysis revealed the following

H6a. The featured products weaken the promptness of promotion effects.

minimum sample size requirements to detect different effect sizes: for small

H6b. The featured products weaken the continuity of promotion effects.

effects (f2 = 0.02), 423 observations are needed; for medium effects (f2 = 0.15),

We visually describe the conceptual framework of this study in Fig. 1.

83 observations are required; and for large effects (f2 = 0.35), 53 observations

are sufficient. With a final sample size of 1656 observations, we far exceed 4. Methodology

these thresholds. Thus, the drop in observations is not a concern for our study.

In this section, we first illustrate the process of data collection. Then we

4.2. Independent and dependent variables

discuss the construction of each variable in the model.

The core independent variable in this study is the extent of promotion 4.1. Data collection

(Promotion), measured as the discount in percentages. We obtained this

number by subtracting the final price from the original price and then dividing

We collected data from an e-tailer platform called Woot.com. Woot is a

the new number by the original price. The range of promotion extent was from

United States–based e-tailer. It was launched in July 2004 and later acquired 0 % to 93 %.

by Amazon in 2010. Since then, Woot has continued to run independently.

In this study, we have two dependent variables. First, we captured

Woot is known for offering a variety of discounted products. We chose Woot

Promptness as time lapses in seconds between the availability of the product

for two major reasons. First, the focus of this study is promotion, and Woot

and the first purchase. That is, a lower value of Promptness indicates the

offered a suitable context because it specializes in selling discounted products.

product is sold quickly. We divided this variable by 1000 to better interpret the

The Woot website shows the original price, list price, and discount percentage

regression results. In addition, we measured promotion continuity (Continuity)

for its products when available. In other words, consumers can notice

as the inversed value of the standard deviation of the percentage of sales per

discounts in percentages easily. Although some products on Amazon and eBay

hour. Woot offers distribution regarding the percentage of products sold

also show the discount percentages, that is not so common as it is on Woot

during each hour of each day. Standard deviations of these percentage

because Woot’s focus is discounted products. Second, this platform offers

numbers reflect the dispersion of the sales. That is, a product with a smaller

unique data to test our hypotheses. E-tailer websites such as Amazon and eBay

standard deviation indicates longer continuity in promotion. We took the

usually do not disclose the backgrounds of their consumers owing to privacy

inversed value of the standard deviation for the purpose of easy

issues. Although Woot does not disclose individual consumer information, it

interpretations. This approach means that higher values correspond to more

offers aggregate-level information about consumers for each product sold on

continuous promotion effects, which makes the data more straightforward to

its website. Specifically, on the page of each product, Woot displays descriptive interpret.

information about consumers who have purchased that product. For instance,

this information includes how long it took for the first unit to be sold. Woot

4.3. Moderating variables

also presents information regarding how many products consumers have

purchased on Woot before, how long the consumers have been registered on

In this study, we tested the moderating effects of four variables: purchase

Woot, and how many units are included in every order and are purchased in

seniority (Seniority), purchase experience (Experience), the featured channel every order.

(Channel) and the featured product (Product). We captured purchase seniority

We obtained data of interest from Woot in two steps. First, we used Woot’s

(Seniority) as the average number of days since consumers registered on

Application Programming Interface (API) to collect all available information in

Woot.com. Further, we measured purchase experience (Experience) as the

its database. Second, we developed a customized Python program to obtain

average number of products consumers had purchased before. Channel was

data that are not available via the API. We used the URL links of the products

operationalized as a binary variable to indicate whether a product is fulfilled

from the first step to retrieve all available products in the second step. We

by Amazon. Although Woot has operated independently after it was acquired

obtained 2206 products from Woot based on a search dated February 2, 2022.

by Amazon, some products sold on Woot are fulfilled by Amazon. Fulfillment

After dropping the observations with missing values in any variable following

by Amazon means products are stored, packaged, and then shipped by previous studies (e.

Amazon. However, all transaction processes are still completed on Woot. com.

g., Dong and Peng, 2013; Enders, 2003), we obtained 1656 products for the

Consumers can see a noticeable tag on the product web page, showing that

analysis. To ensure that the missing data mechanism did not introduce

this specific product is fulfilled by Amazon. We used 1 to denote if the product

systematic bias, we conducted a thorough analysis of the data structure.

is fulfilled by Amazon, otherwise 0. We captured

Specifically, we examined the distribution of product categories between the lOMoAR cPSD| 59078336

Y. Zhuang and X. Xu Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 86 (2025) 104322 Table 2

Descriptive statistics. Product to indicate whether the product was classified as Woot Plus product or not. A Woot Plus product is a featured product by Woot and is

highlighted on the product web page with a corresponding mark. We used 1 Variable Measure Mean Std. Dev. Min Max

to denote a Woot Plus product and 0 to denote a non-Woot Plus product.

Dependent Variables Promptness Numeric 27.188 77.117 0.194 522.270 4.4. Control variables Continuity Numeric 0.173 0.081 0.067 0.428

Independent Variables

We included product-related and transaction-related control variables in our Promotion Numeric 0.379 0.246 0.000 0.930 Moderators

models. The product-related control variables included Pictures, Condition, Seniority Numeric 321.370 40.827 183.000 365.000

Category, Replies, and Likes. Pictures referred to the number of pictures shown on Experience Numeric 17.800 3.981 6.000 25.000

the web page for the product. We divided this value by 10 for the purpose of easy Channel Binary 0.431 0.495 0.000

1.000 interpretation. A higher number of pictures would facilitate consumers’ knowledge Product Binary 0.910 0.286 0.000 1.000

Control Variables

of and familiarity with the product and thus could influence their purchase behavior Pictures Numeric 0.552 0.366 0.100

1.800 (Hou, 2007). In addition, Woot sells both new products and refurbished products, Condition Binary 0.921 0.269 0.000

1.000 and consumers may behave differently in relation to them (Neto et al., 2016). We Replies Numeric 0.295 1.005 0.000

7.000 thus included Condition as a control variable with the value of 1 meaning that the Likes Numeric 0.370 1.593 0.000 12.000 Mobile

product is new and 0 otherwise. Further, a variety of products are available on Woot Binary 0.005 0.069 0.000 1.000 Weekend Binary 0.030 0.170 0.000

1.000 under different categories, including groceries, home, PC, shirts, sports, technology, Category_Grocery Binary 0.063 0.243 0.000

1.000 and tools, which could generate consumers’ different purchase behaviors Category_Home Binary 0.270 0.444 0.000

1.000 (Kushwaha and Shankar, 2013). Thus, we included a binary variable (i. Category_PC Binary 0.066 0.248 0.000 1.000 Category_Shirt Binary 0.046 0.209 0.000 1.000 Category_Sport Binary 0.307 0.461 0.000 1.000 Category_Tech Binary 0.081 0.273 0.000 1.000 Category_Tools Binary 0.168 0.374 0.000 1.000 lOMoAR cPSD| 59078336

Y. Zhuang and X. Xu Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 86 (2025) 104322

e., Category) for each category and included them in the model. In addition, Woot platform offers a discussion forum for each item, functioning lOMoAR cPSD| 59078336

Y. Zhuang and X. Xu Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 86 (2025) 104322

similarly to reviews by providing user-generated content and social proof. We retrieved the number of discussion threads (Replies) and “likes” (Likes)

from these forums for each product and included them as control variables.

Transaction-related control variables included the distribution channel and sales ending time. We included Mobile as a control variable to

indicate whether the product was available on mobile only or not. We coded Mobile as 1 if the product was available on mobile only and 0 otherwise.

The mobile-only products were only available to consumers who used Woot’s mobile app, and the availability of distribution channel affected

consumers’ purchase behavior (Wang et al., 2015). In addition, we also considered whether the sales ending time was during the weekend

(Weekend) as a binary variable. Product sales that end during the weekend are more likely to attract more potential consumers due to their

availability (Subramanian and Subramanyam, 2012). We used 1 to indicate discounts for products that ended on weekends and 0 otherwise. Table

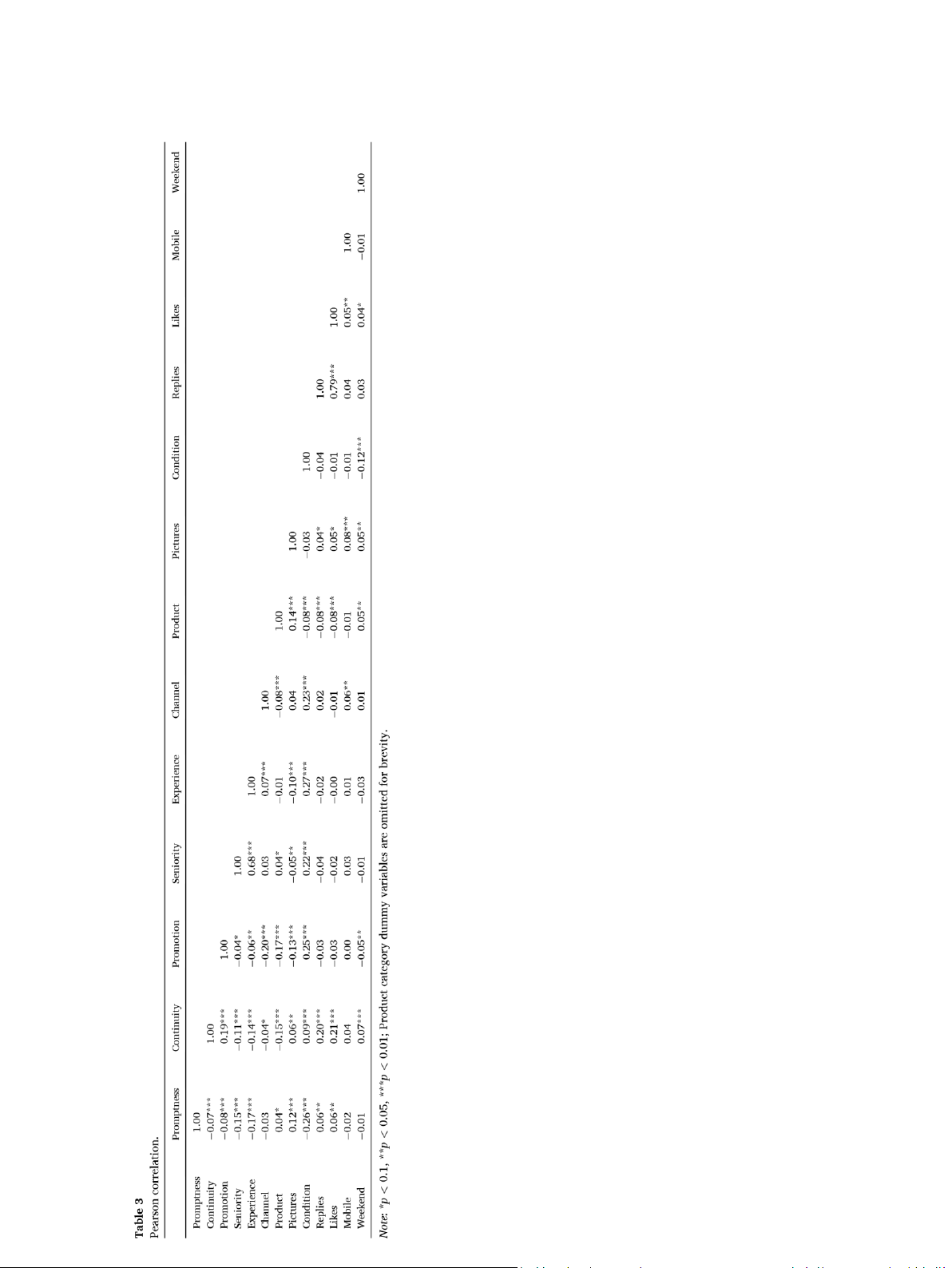

2 presents the descriptive statistics of all variables. Note, all continuous variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles. The correlations

between the variables are presented in Table 3. 4.5. Analysis

DVi =β0 + β1 Promotioni + β2 Promotion2i + β3 Channeli + β4Producti + β5 Picturesi +

β6 Conditioni + β7 Repliesi + β8 Likesi + β9 Mobilei + β10

Weekendi + Viφ + εi, (1)

To test for the curvilinear relationship of Promotion with Promptness (H1) and Continuity (H2), we include both the linear terms and quadratic terms

of Promotion in the regression. We specify the estimated model in Eq. (1):

where subscript i indicates each Woot product listing. The DV is Promptness or Continuity. Vi is a vector that includes all of the product category

dummy variables, and εi is the error term.

To test the moderating effects of consumer seniority, consumer experience, featured channels, and featured products on the impact of

promotion on Promptness and Continuity, we have included both the interaction terms between the moderators (i.e., Seniority, Experience, Channel,

Product) and the linear terms of Promotion and the moderators and the quadratic term of Promotion into the regression based on Eq. (1), which forms Eq. (2):

DVi =β0 + β1 Promotioni + β2 Promotion2i + β3 MODi + β4Promotioni × MODi + β5Promotion2i × MODi + β6 Picturesi + β7 Conditioni + β7 Repliesi + β8 Likesi +

β9 Mobilei + β10 Weekendi + Viφ + εi, (2)

where MOD refers to the moderator, which is Seniority, Experience, Channel, or Product. All other notations and variables are the same as in Eq. (1).

Given the potential correlation between the error terms in our promptness and continuity models, we employ Seemingly Unrelated Regression

(SUR) to account for this interdependence. SUR can estimate multiple equations simultaneously while accounting for cross-equation error

correlation and achieve more efficient estimation (Aruoba and Drechsel, 2024). To address the potential concerns of inference under

heteroskedastic, we adopted robust variance-covariance. Additionally, we calculated variance inflation factors for all explanatory variables, with all

values falling well below 10, offering evidence that multicollinearity is not a concern for our study (Kim, 2019; Shrestha, 2020). Table 4

5. Results and discussions Results of main effects. Variables Model 1(a) Promptness Model 1(b)

5.1. Results of promptness and continuity of promotion effect Based on the Continuity

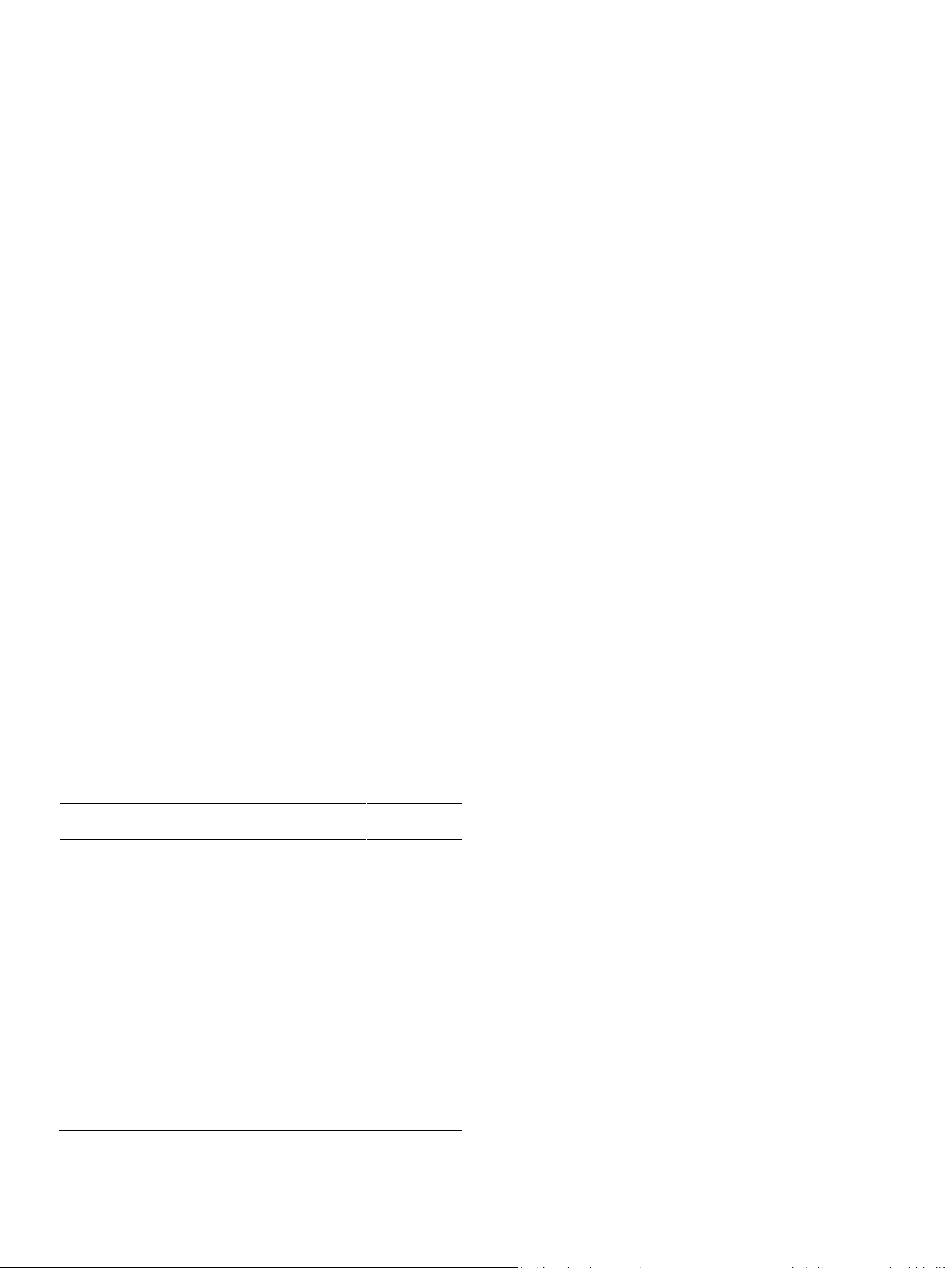

results of Model 1(a) shown in Table 4, we find that the impact of promotion Promotion Promotion2 − 72.035** (29.329) − 0.033 (0.029) 57.062** (27.413) 0.112*** (0.030)

on promptness follows a U-shaped curve (β = 57.062,p = 0.037). Therefore, H1 Channel − 1.355 (4.327) 0.006 (0.004)

is supported. This finding indicates that a greater promotion discount first Product − 4.906 (3.177) − 0.036*** (0.008)

attracts consumers to purchase the product quickly. However, consumers Pictures 7.498 (5.808) 0.016*** (0.006)

become more hesitant when the promotion extent increases even more. Condition − 36.652** (15.098) 0.037*** (0.011)

Greater discounts attract the consumer to place the order quickly for two Replies − 2.040 (3.121) 0.008** (0.004) Likes 3.165 (2.322) 0.007*** (0.002)

major reasons. First, it is easier to get consumers’ attention immediately when Mobile − 39.327** (18.839) 0.033 (0.043)

the promotion extent is relatively higher. Second, Woot is a smaller e-tailer Weekend − 9.588* (5.189) 0.050*** (0.012)

with limited inventory. Therefore, consumers may worry that products with Category_Home − 0.478 (3.611) − 0.018** (0.008)

greater discounts will sell out quickly without sufficient stock. However, Category_PC 2.910 (13.365) 0.003 (0.013) Category_Shirt − 23.200*** (7.619) 0.036** (0.014)

consumers have more hesitation when the promotion extent is extremely high, Category_Sport 4.868 (3.251) 0.009 (0.009)

based on two concerns. Although Woot is backed up by Amazon, it is still less Category_Tech 127.532*** (15.880) 0.049*** (0.011)

well known than other main e-tailers in the United States, like Amazon itself or Category_Tools 9.010** (4.267) − 0.013 (0.009)

eBay. Consumers may be concerned that Woot is a scam, often indicated by Constant 65.108*** (17.719) 0.142*** (0.016)

extremely large discounts. The second concern is that consumers may suspect # of Observations 1656 0.262 1656 0.180

the quality of the product owing to the discount size. Therefore, consumers R2

may need to take additional time to conduct research on the product to make χ2 153.377*** 339.806***

sure of its quality. These two concerns together delay consumers’ purchase of

Note: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01. Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

the products with an extremely high promotion extent. lOMoAR cPSD| 59078336

Y. Zhuang and X. Xu Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 86 (2025) 104322

The results of Model 1(b) in Table 4 show a U-shape between promotion (0.168) (0.000) (0.070) (0.000)

extent and promotion continuity (β = 0.112,p < 0.001), which offers evidence Promotion × Seniority 1.101 − 0.001*

supporting H2. That is, the continuity of a promotion effect follows a U-shaped (0.707) (0.001)

curve depending on the promotion’s extent. The turning point is at 0.153. Experience − 0.494 − 0.002*** − 3.456** 0.000

When the promotion extent is low, it is not so attractive that consumers hurry (0.768) (0.001) (1.586) (0.001)

to purchase it, which yields a steady sales flow. However, when the promotion

extent is high, the promotion can attract consumers over time so that the Promotion × 17.896** − 0.015*** (7.410) (0.006)

promotional continuity is also high. Thus, our findings suggest two alternative Experience Promotion2 386.047*** − 0.183

ways for e-tailers to keep a high promotional continuity, either by offering a 390.303* − 0.075

low or a high discount, but not by staying in the middle. We plot these U- (233.348) (0.222) (147.955) (0.132)

shaped relationships in Fig. 2. As we can observe from Fig. 2(a), when Seniority × − 1.041 0.001

promotions are either very low or very high, customers take longer to make Promotion2 (0.712) (0.001)

purchases (higher promptness values). The optimal discount level for the Experience × − 18.728** 0.017**

fastest purchases appears to be around 60 %. Similarly, Fig. 2(b) shows a U- Promotion2 (7.815) (0.007)

shaped relationship between promotion level and continuity but with a much Channel − 0.877 0.005 − 1.171 0.006

more gradual curve. The minimum point occurs at around a 20 % discount (4.311) (0.004) (4.328) (0.004)

level. After this point, there is a steady increase in continuity as promotion levels increase. Product − 5.089 − 0.032*** − 4.411 − 0.034*** (3.352) (0.008) (3.311) (0.008)

5.2. Results of moderating effects of consumer seniority and experience Pictures 7.311 0.013** 7.756 0.013** (5.732) (0.006) (5.713) (0.006)

Table 5 shows the results regarding the moderating effect of consumer

seniority and consumer experience. Specifically, the results from Model 2(a) Condition − 33.328** 0.040*** − 29.954** 0.038***

show that there is no statistically significant difference (15.249) (0.011) (14.992) (0.011)

(β =− 1.041,p = 0.144) in how highly senior and newer consumers accelerate Replies − 2.128 0.008** − 2.151 0.008**

their purchase timing in response to extreme discounts. Thus, H3a is not (3.111) (0.003) (3.112) (0.003)

supported. Psychologically, strong forces like the fear of missing out, scarcity- Likes 3.272 0.006*** 3.333 0.006***

driven urgency, and loss aversion apply universally, pushing all consumers to (2.312) (0.002) (2.314) (0.002)

act quickly on an extreme deal. Behaviorally, Woot’s customers–whether new

or long-standing–tend to be deal-oriented individuals who remain sensitive to Mobile − 40.421** 0.039 − 40.472** 0.039 price cuts. (18.673) (0.042) (18.213) (0.042)

The results from Model 2(b) show that consumer seniority does not Weekend − 10.052* 0.049*** − 11.761** 0.051***

weaken or strengthen the U-shaped relationship between promotion and (5.188) (0.012) (5.196) (0.012)

promptness (β = 0.001, p = 0.395). Thus, H3b is not supported. This could be

because extreme discounts can sustain consistent sales over time regardless of Category_Home − 0.876 − 0.021*** 0.259 − 0.022*** (3.706) (0.008) (3.666) (0.008)

buyer seniority. When prices drop significantly, both new and veteran shoppers

may find the deal too attractive to pass up, leading to more uniform purchasing Category_PC 1.842 − 0.004 1.875 − 0.004

activity. In addition, while senior customers may have more established buying (13.649) (0.013) (13.523) (0.013) patterns that could Table 5 Category_Shirt − 20.988*** 0.029** − 18.530** 0.028**

Moderating effects of consumer seniority and experience. (7.652) (0.013) (7.181) (0.013)

Variables Model 2(a) Model 2(b) Model 2(c) Model 2(d) Promptness Continuity Promptness Category_Sport 4.363 0.003 5.872 0.002 Continuity (3.732) (0.009) (3.689) (0.009) Promotion − 425.280* 0.261 − 388.052*** 0.232** (233.693) (0.171) (143.180) (0.106) Category_Tech 127.363*** 0.037*** 129.146*** 0.036*** Seniority − 0.175 0.000** 0.021 0.000

Fig. 2. Effects of promotion on promptness and continuity. lOMoAR cPSD| 59078336

Y. Zhuang and X. Xu Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 86 (2025) 104322 (16.448) (0.011) (16.497) (0.011)

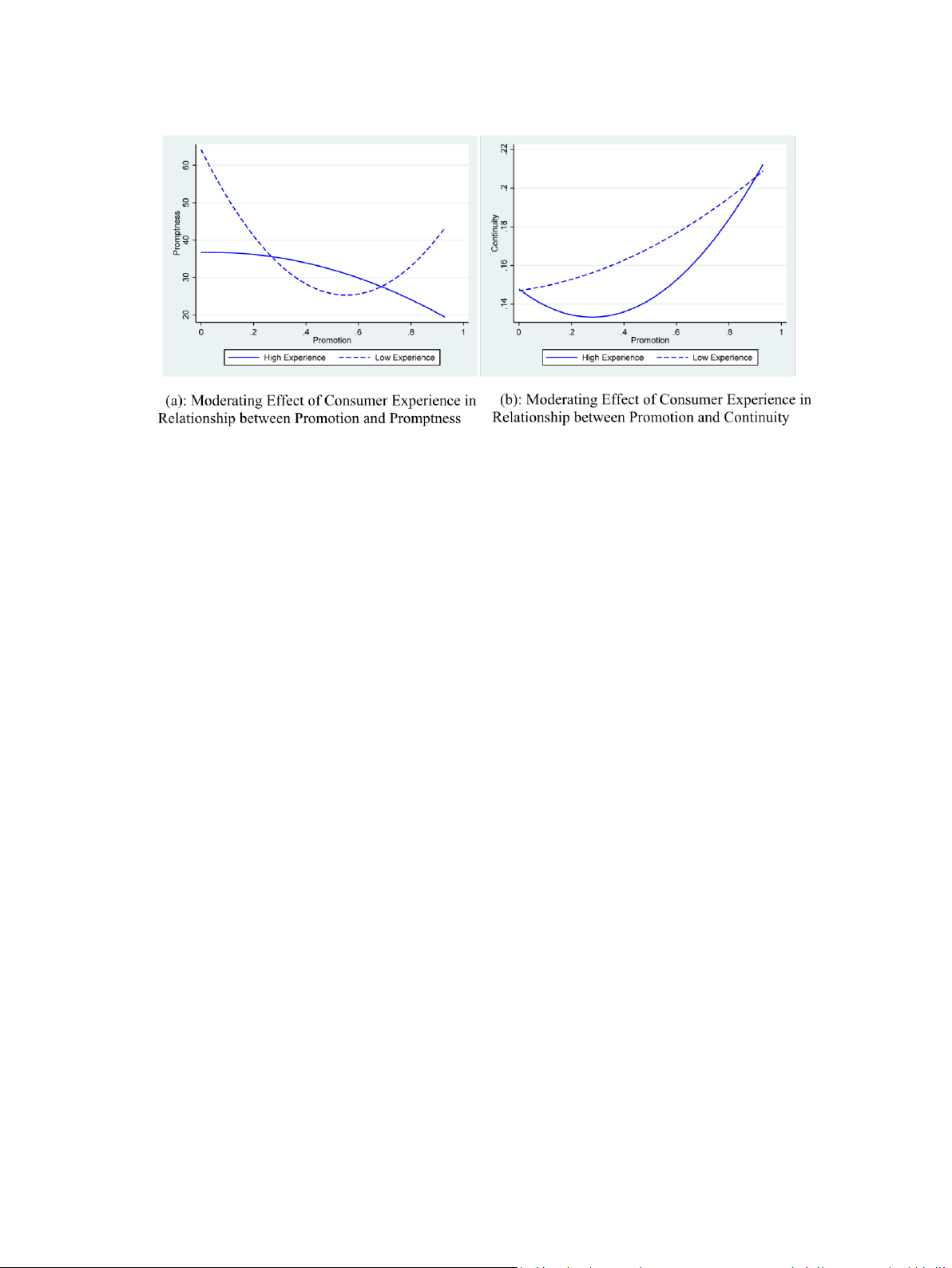

rushed decision-making (Simcock et al., 2006), thereby neutralizing the

moderating impact of featured channel on the impact of promotions on Category_Tools 8.606** − 0.017* 10.073** − 0.018** promptness. (4.377) (0.009) (4.372) (0.009)

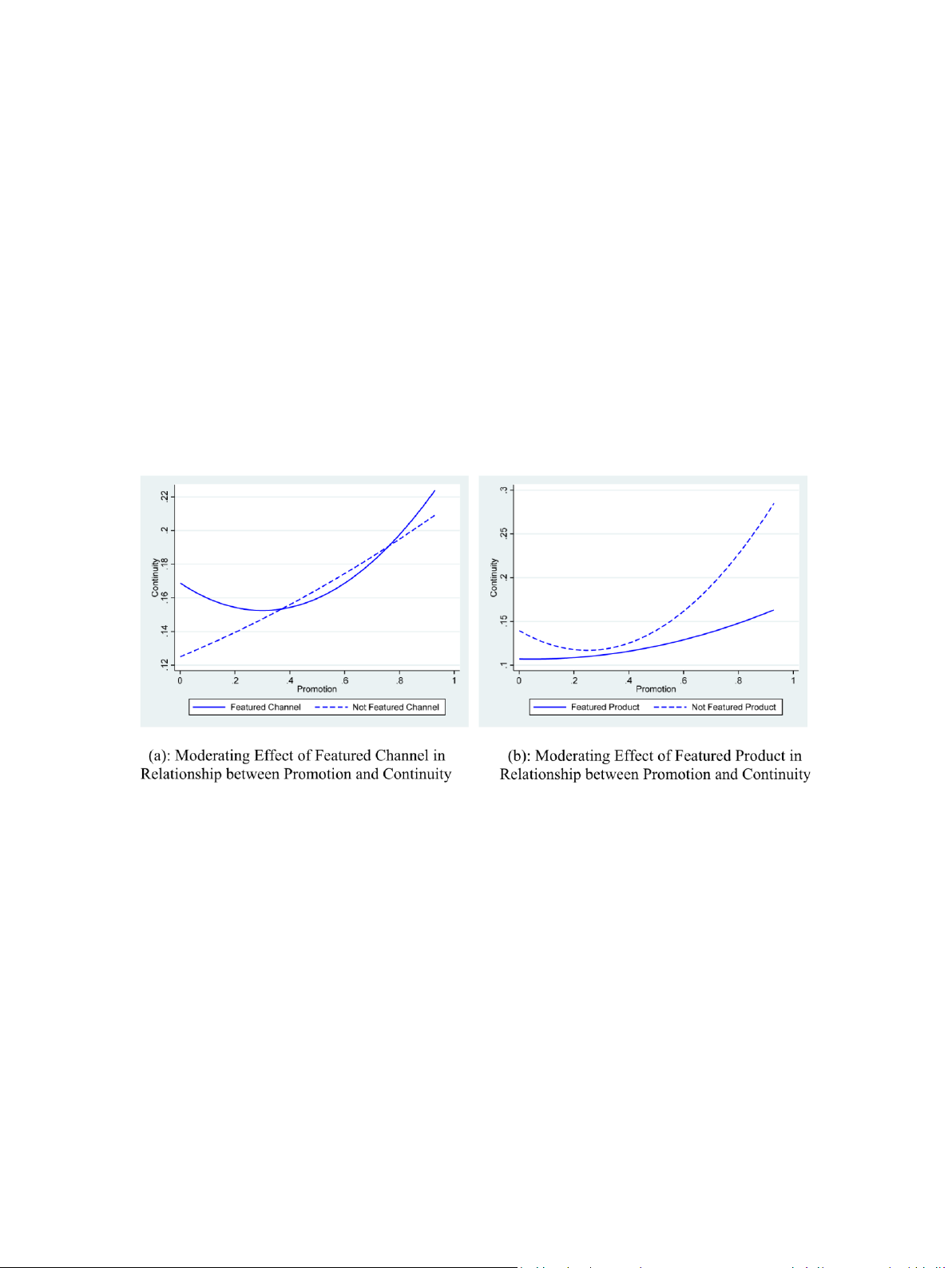

According to Model 3(b), a featured channel strengthens the U-shaped Constant 127.566** 0.115*** 111.991*** 0.146***

relationship between promotion and continuity (β = 0.156, p = 0.078), which (51.254) (0.030) (33.694) (0.024)

offers evidence in support of H5b. That means the nonlinear effect of

promotion on continuity increases when the products are fulfilled by Amazon.

The branding of Amazon increases consumers’ trust and reduces their # of 1656 1656 1656 1656

perceived risks. This benefit is particularly recognizable given that Woot is a Observations

relatively small e-tailer and is less well known. These products backed up by R2 0.265 0.197 0.268 0.197 χ2 156.075*** 385.212*** 150.147*** 394.239***

Amazon can continuously attract consumers for longer periods. In addition to

the enhancement of credibility, featured channels typically offer enhanced

service features such as better tracking systems, more flexible return policies,

Note: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01. Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

and superior customer support. These value-added services reduce post-

purchase anxiety and encourage consumers to maintain consistent purchasing

stabilize sales flow, they might also be more selective in their purchases due to

behavior. We plot this moderate effect in Fig. 4(a). This figure shows a more

accumulated experience with the platform’s promotional patterns. These

pronounced U-shaped relationship between promotion and continuity for

opposing forces could cancel each other out, resulting in no significant net

products sold through featured channels (shown by the solid line). In contrast,

moderating effect on the impact of promotions on promotion continuity.

non-featured channels (represented by the dashed line) display a much flatter,

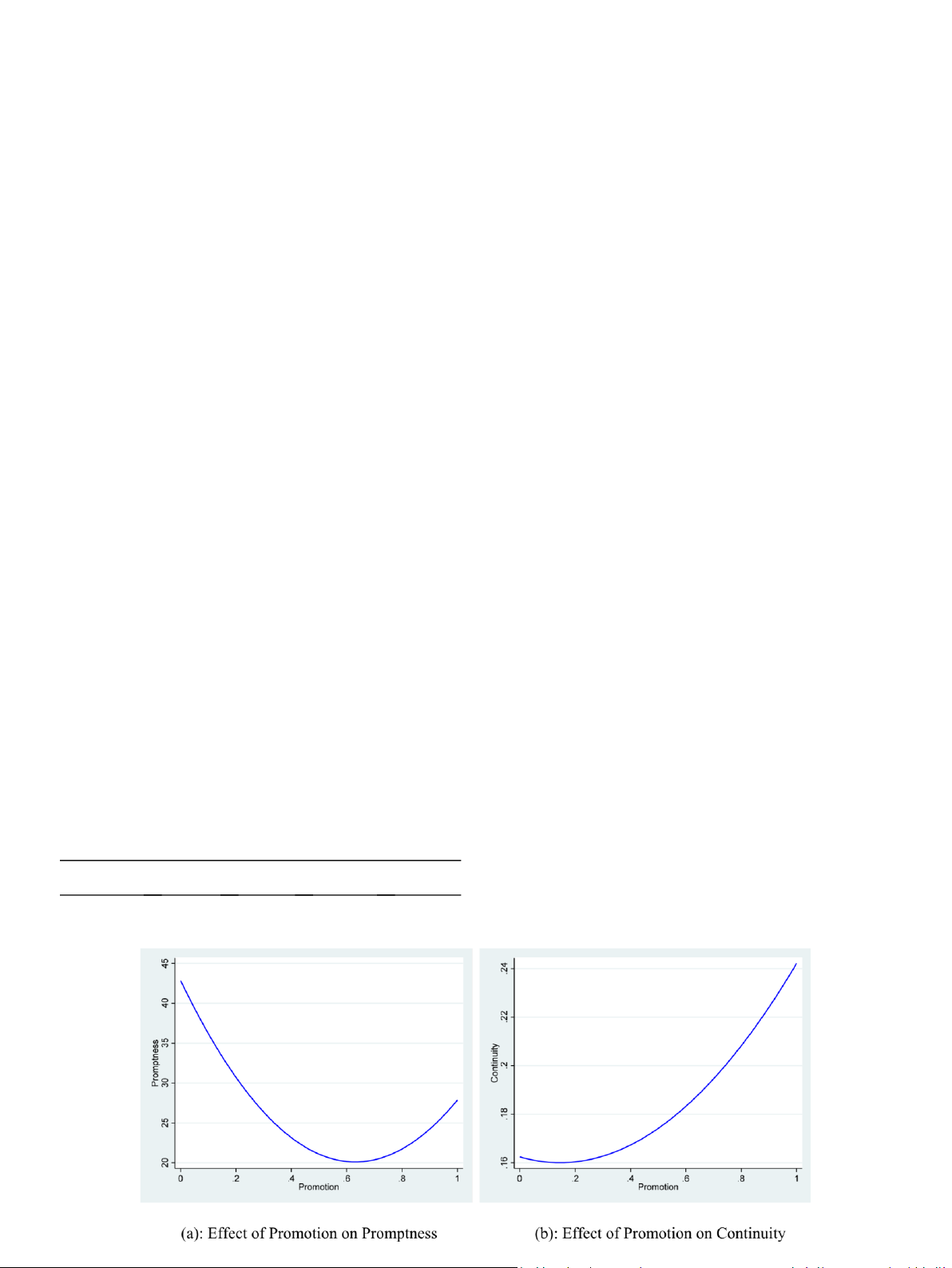

The results from Model 2(c) show that the U-shaped effect of promotion almost linear upward trend.

on promptness is weakened for more experienced consumers (β = − 18.728, p

In addition, the regression results for the moderating effect of featured

= 0.017). Thus, H4a is supported. More experienced consumers often

product appear in Table 6. The findings from Model 3(c) show that featured

understand product value more clearly and are less prone to impulse buying

product does not weaken or strengthen the U-shaped relationship between

when promotions arise. Their familiarity with price trends lets them discern

promotion and promptness (β = 60.612, p = 0.191). This means that whether

which deals are genuinely advantageous, making extreme discounts less likely

or not a product is highlighted as a featured product does not materially

to shift their purchasing timelines drastically. We plot this moderate effect in

change how consumers speed up their purchase timing in response to varying

Fig. 3(a). From the figure, we can observe a pronounced U-shaped relationship

discount levels. On the sale platforms like Woot, multiple promotions and deals

for less experienced consumers (represented by the dashed line). In contrast,

vie for consumer attention. In such an environment, a “featured” tag can get

more experienced consumers exhibit an almost linear, gradually declining

lost among the myriad of discounts, leading shoppers to focus more on price

relationship between promotion and promptness (shown by the solid line).

or brand familiarity rather than on special labeling. Thus, H6a is not

Meanwhile, the results from Model 2(d) show that the U-shaped effect of

promotion on continuity is strengthened for more experienced consumers (β

= 0.017, p = 0.019). Therefore, H4b is supported. This means that experienced

consumers react more strongly to both very low and very high promotion

levels, showing more consistent purchasing patterns in these extreme cases

compared to less experienced consumers. Experienced consumers usually

have extensive platform knowledge, which leads to more consistent

purchasing patterns. This is because they can better assess true value at low

promotion levels while also quickly identifying and acting on genuinely

attractive deals at high promotion levels. This behavior contrasts with less

experienced consumers, who tend to show more moderate and less strategic

responses across the promotion range. We plot this moderate effect in Fig.

3(b). As we can see, for consumers with high purchase experience (shown by

the solid line), there is a more pronounced U-shaped relationship between

promotion and continuity. In contrast, consumers with low purchase

experience (represented by the dashed line) exhibit a flatter and more gradual upward curve.

5.3. Results of moderating effects of featured channel and product

Table 6 shows the results regarding the moderating effect of the featured

channel. Specifically, the results from Model 3(a) show that a featured channel

does not weaken or strengthen the U-shaped relationship between promotion

and promptness (β = − 44.352,p = 0.639). Thus, H5a is not supported. This

nonsignificant moderating effect could stem from countervailing mechanisms.

On the one hand, a reputable featured channel could foster greater trust and

potentially shorten decision time. On the other hand, knowing a product

comes through a highly reliable channel might reduce the urgency to “buy

now,” which may lead consumers to deliberate longer. This finding aligns with

prior research indicating that lower perceived risk can reduce the need for lOMoAR cPSD| 59078336

Y. Zhuang and X. Xu Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 86 (2025) 104322

Fig. 3. Moderating effect of consumer experience in relationship between promotion and promptness or continuity. supported.

Shankar and Kushwaha, 2021), while our results about featured products

Results from Model 3(d) show that featured product weakens the U-

weakening continuity present an interesting contrast to traditional

assumptions about product featuring (e.g., Ku and Hsu, 2023; Wang and Qiu,

shaped relationship between promotion and continuity (β = − 0.291, p = 0.055). 2024).

Thus, H6b is supported. That means, while discount extent might normally

magnify or diminish sales consistency, featured products maintain steadier

sales regardless of promotional fluctuations. This could be explained by the

6.1. Theoretical implications

fact that being featured for a product confers an additional level of

endorsement and visibility on the platform, which can attract a steady stream

The findings of this study contribute to signaling theory and existing

of buyers who value the platform’s recommendation. As a result, these

promotion literature. First, the findings of our study extend signaling theory.

products may experience consistent demand that does not fluctuate

We find that the effects of the signals depend on the extent of the promotion

dramatically with different discount levels. In addition, featured products

discounts. Previous studies (e.g., Li et al., 2019; Martín et al., 2011) categorized

typically undergo more rigorous selection processes with superior product

various signals as positive or negative based on their effect. However, in this

attributes or unique value propositions. These inherent product qualities

study, we find that the positive or negative signals not only depend on the type

create a more sustainable competitive advantage that is less dependent on

of information posted but also on the magnitude reflected in the information.

price promotions to drive sales. We plot this moderate effect in Fig. 4(b). This

From the signalers’ perspective, the different magnitudes of promotion reveal

figure shows a more pronounced U-shaped relationship between promotion

the different reliabilities of the signals and have different observability. This

and continuity for non-featured products (represented by the dashed line). In

adds a new dimension to signaling theory, emphasizing that signal strength, in

contrast, featured products (shown by the solid line) demonstrate a much

terms of promotional discounts, influences its visibility and credibility.

flatter, more linear relationship.

Further, from the receivers’ perspective, the different magnitudes of

promotion may receive different levels of attention from various consumers 6. Discussion

and will be interpreted by them differently. Our findings reveal that the

magnitude of the signal strengths—namely, the promotion effects—depends

Our finding of a U-shaped relationship between promotion extent and both

on three aspects–consumers’ historical purchase behaviors, including their

promptness and continuity extends previous research in several ways. While

seniority and purchase experiences, channels, and products, which let the

prior studies (e.g., Dai et al., 2022; Drechsler et al., 2017) suggested that higher

signals be perceived with different credibility and reliability and lead

promotions generally yield stronger effects, our results reveal a more nuanced

consumers to have different valuations of the promotion.

relationship. The U-shaped pattern we found challenges the conventional

In addition, our study extends the promotion literature by focusing on the

wisdom that “more is better” in promotional discounting. This aligns with Buil

effect of platform promotions. Although most previous studies of promotion

et al.’s (2013) concerns about excessive discounts potentially reducing

effects have focused on the positive influence of promotion on sales (e.g.,

perceived quality while extending their work by identifying the specific

Parshakov et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020), in our study, we focused on the

patterns in consumer response timing. Additionally, our findings regarding

process rather than the consequence of promotions. Specifically, we

consumer characteristics provide interesting contrasts with existing literature.

investigate the timing effect of e-tailers’ promotions: promptness and

While studies found that consumer experience generally enhances promotion

continuity. The findings suggest that the promotion discount at an

effectiveness (e.g., Maity and Gupta, 2016; Peschel, 2021), our results show

intermediate level can amplify a promotion’s attractiveness by stimulating

that experience weakens promptness but strengthens continuity. This nuanced

consumers to purchase promptly and continuously. Further, our study

finding suggests that experienced consumers are less likely to make immediate

uncovers that the promotional effect is not uniform across all consumers;

purchases but maintain more consistent purchasing patterns over time. These

instead, it varies significantly based on consumer attributes such as seniority

results add important temporal dimensions to our understanding of how

and purchase history, channel attributes, and product attributes. Our findings

consumer characteristics influence promotion effectiveness. Moreover, our

thus support the moderating effects of these three aspects of attributes on

findings about featured channels and products both support and challenge

promotion performance. This finding introduces a new perspective to

existing research. The strengthening effect of featured channels on continuity

understanding promotion effects, suggesting that e-tailers’ promotions should

aligns with findings about channel credibility (e.g., Lee and Sharma, 2024;

segment the specific consumer, lOMoAR cPSD| 59078336

Y. Zhuang and X. Xu Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 86 (2025) 104322 Table 6

channel, and product groups. These findings thus offer a theoretical expansion

Moderating effects of featured channel and product.

in understanding promotion dynamics by revealing that the choice of the

Variables Model 3(a) Model 3(b) Model 3(c) Model 3(d) Promptness Continuity Promptness

above three aspects of groups crucially influences the effectiveness of price Continuity promotions. Promotion − 203.847*** 0.067* 7.155 − 0.181 (57.423) (0.040) (41.790) (0.171)

6.2. Managerial implications Channel − 49.459*** 0.044*** − 1.237 0.009** (13.896) (0.012) (4.381) (0.004)

Many businesses currently are aware of the positive function of

promotions, making promotions among the most common approaches to

Promotion × Channel 156.124** − 0.176***

increase sales. E-tailers should carefully design their promotion strategies with Promotion2 (69.710) (0.065)

comprehensive considerations (Dong et al., 2021; Okazaki et al., 2012). The 163.142*** 0.025 − 2.918 0.364**

findings of this study provide important managerial implications guiding (50.894) (-0.038) 0.156* (39.627) (0.152)

businesses, especially platforms or e-tailers, to implement promotions in Promotion2 − 44.352 (0.088) × awareness of their effects. (94.496) Channel

First, e-tailers should not evaluate promotion effects from a single Product − 4.517 − 0.035*** 17.331 − 0.033

perspective, such as sales generation. Instead, they should have a holistic view (2.991) (0.008) (11.830) (0.043)

of the promotion effect, including its properties, such as promptness and Promotion × Product − 81.490 (50.411) 0.175

continuity, rather than only focusing on aggregated sales quantities. That is, e- Promotion2 ×

tailers should pay attention to the consequences of promotional effects and 60.612 (0.171) Product (46.393) − 0.291*

the process, namely, the timing effect of promotions. This is because (0.152)

promptness and continuity affect the cash flow of e-tailers, which further

influences their operations and ultimately generates increased sales. In Pictures 8.516 0.014** 7.421 0.017*** (5.873) (0.006) (5.823) (0.006)

particular, e-trailers should focus on the long-term flow effect of promotions

by continuing to attract consumers’ purchases rather than pushing consumers Condition − 27.706* 0.030*** − 36.681** 0.035***

to purchase within a short period. In this way, continuous purchases can (15.031) (0.011) (15.076) (0.011)

smooth e- tailers’ cash flow to ensure their normal operations and create a

positive cycle to enhance their sales performance in the long run. An ideal Replies − 2.349 0.008** − 2.093 0.008**

situation for the timing flow of the promotion effects is to let consumers have (3.020) (0.003) (3.129) (0.003)

a quick response to the price promotions and a continuing flow to generate Likes 3.160 0.007*** 3.192 0.006***

sales. To achieve a high level of promptness and continuity of the promotion (2.265) (0.002) (2.325) (0.002)

effects, sellers should not offer steep discounts as it does not always increase

purchases but also hurts the marginal profits. On the one hand, e-tailers should Mobile − 39.260** 0.036 − 38.979** 0.034

offer a significant discount, rather than making the promotions “public stunts,” (17.090) (0.043) (18.822) (0.040)

to make the promotions visible to consumers. On the other hand, e-tailers

should not provide extremely high discounts because they increase Weekend − 21.973*** 0.055*** − 9.734* 0.049*** (6.842) (0.013) (5.204) (0.012)

consumers’ hesitation and reluctance to purchase and reduce the promptness

of the promotion’s effects. Thus, a balanced promotion discount, considering Category_Home − 2.959 − 0.016* − 0.547 − 0.021**