Preview text:

PART INTRODUCTION 1 Managing Human 1Resources Today OVERVIEW:

In this chapter, we will cover . . . ■

■ THE TRENDS SHAPING HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

■ CONSEQUENCES FOR TODAY’S HUMAN RE SOURC E MANAGERS ■ THE PLAN OF THIS BOOK LEARNING OBJECTIVES MyManagementLab®

When you finish studying this chapter, you should be able to: Improve Your Grade!

When you see th is icon, visit

1. Answer the questions, “What is human resource

www.mymanagementlab.com for

management?” and “Why is knowing HR management

activities that are applied, personalized,

concepts and techniques important to any supervisor and offer immediate feedback. or manager?”

2. Describe with examples what trends are influencing human resource management.

3. Discuss at least five consequences today’s trends have for human resource management.

4. Outline the plan of this book. Learn It

If your professor has chosen to assign this, go to www.mymanagementlab.com

to see what you should particularly focus on and to take the Chapter 1 Warm Up. 33 34 PART 1 • INTR ODU CTIO N INTRODUCTION

It was her first week working as an Executive Team Leader

(assistant manager) in charge of the sales floor at the

new Target store, and Tori was excited to be supervis

ing about 40 employees. As was usual, the store had its

own human resource team, but Tori was still surprised at

how much time she spent on “HR”. These tasks included

personally interviewing prospective sales associates, and

then making sure that each was properly trained, evalu

ated, and awarded pay hikes. She mentioned this to a

friend who worked at another chain, and who said,

“No, that’s pretty much par for the course—I spend

about a third of my time on tasks like that too.” S ource: John Gress/Corbis. LEARNING OBJECTIVE 1

WHAT IS HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT? Answer the questions,

To understand what human resource management is, we should first review what “What is human resource

managers d o. The new Target store is an organization. An organ ization co nsists of people management?” and

(in th is case, people like sales and maintenance employees) with formally assigned rol es “Why is knowing HR

who work together to achieve the organization’s goals. A manager is someone who is management concepts

responsi ble for accomplishing the organization’s goals, and who does so by managing the and techniques important

efforts of th e organization’s people. to any supervisor or

Most writers agree that manag ing involves performing five basic functions: plan manager?”

ning, organizing, sta ffing, leading, and controlling. In total, these functions represent the

management process. Some of t he specific activities invo lved in each function include:

• Planning. Establishing goals and standards; developing rules and procedures; developing plans and forecasts organization

• O rganizing. Giving each subor dinate a specific task; esta blishing departments; A group consisting of people

delegating authority to subord inates; establishing channels of authority and

with formally assigned roles who

communication; coordinating the work of subor dinate s work together to achieve the

• Staffing. Determining w hat type of people shou ld be hired; recruiting prospect ive em organization’s goals.

ployees; selecting emp loyees; setting perf ormance standards; compensating employees;

evaluating performance; counseling employees; trainin g and developing empl oyees manager •

Someone who is responsible for

Leading. Getting oth ers to get the j ob done; maintaining moral e; motivating

accomplishing the or gan ization’s subordinates goals, and who does so by

• Controllin g. Setting standards such as sales quotas, qualit y standards, or managing the efforts of the

production levels; checking to see how actual performance compares with these organization’s people.

standards; taking corrective action as needed managing

In this book, we will focus on one of these functions—the staffing , personnel manage

To perform five basic functions:

ment, or human resource management (HRM function. Human resource management

planning, organizing , staff ing,

is the process of acquiring, training , appraising, and compensating employees, and of leading, and controlling .

attending to their labor relations, health and safet y, and fairness concerns. The topics management process

we’ll discuss should therefore provide you wit h the concepts and techniques you’ll need

The five bas ic fu nct ions of

to perform the “people” or personnel aspects of manag ement. These include:

planning, organizing, staff ing, leading, and controlling .

• Conducting job anal yses (determining the nature of each employ ee’s job).

• Planning labor needs and recruitin g job candidates. human resource • Selecting job candidates. management (HRM)

• Orienting and training new employees.

The process of acquiring, training, • appraising, and compensating

Managing wages and salaries (compensating employees). •

employees, and of attending to

Providing incentives and benefits .

their labor relations, health and • Appraising performance . safety, and fairness concerns.

• Communicating (interviewing, counseling, disciplining). CHAPTER 1

MANAGING H UMAN R SOURC ES TODAY 35

• Training emp lo yees, and developing managers.

• B uild ing employee relations and engagement.

And what a manager should know about:

• Equal opportunity and affirmative action.

• Employee health and safety.

• Handling grievances and labor relations.

Why Is Human Resource Management Important to All Managers?

Why are the concepts and techniques in this book important to all manag ers? Perhaps

it’s easier to answer th is b y l isting some of th e personnel mistakes you don’t want to make

while manag ing. For example, you don’t want

• To h ave your empl oyees not doing their best.

• To h ire the wrong person for the j ob.

• To experience h igh turnover.

• To h ave your company in court due to your d iscriminatory actions.

• To have your company cited for unsafe practices.

• To let a lack of training undermine your department’s effectiveness .

• To commit any unfair l abor practices.

Carefully stud ying th is book can help you avoid mistakes like these. More impor

tant, it can help ensure that you get results—through people Remember that you could d o

everyth ing else rig ht as a manager—lay brilliant pl ans, draw clear organization charts, set

up modern assembly lines, and use sophisticated accounting controls—but still fail, for in

stance, b y h iring the wrong people or by not motivating subordinates. On the other hand ,

many manag ers—from g enerals to presidents to supervisors—have been successful even

without adequate plans, organizations, or contro ls. Th ey were successful because th ey had

the knack f or hiring the right people for t he right jobs and then motivating, appraising, and

developing them. Remember as you read this book that getting results is the bottom line of

managing and that, as a manager, you will have to get th ese results through people. This fact

hasn’t changed from the dawn of management. As one company president summed it up:

For many years it has been said that capital is the bottleneck for a developing

industry. I don’t think th is any l onger h olds true. I th ink it’s the workforce and th e

company’s inability to recruit and maintain a good workforce t hat d oes constitute

the bottleneck for production. I don’t know of any maj or proj ect backed by g ood

ideas, vig or, and enthusiasm that has been stopped by a shortage of cash. I do know

of in dustries whose growt h has been partly stopped or h ampered because they can’t

maintain an efficient and enthusiastic l abor force, and I think this will hold true even more in th e future.2

At no time in our history has that statement been more true than it is today. As we’ll

see in a moment, intensif ied g lobal competition, tech nol ogical ad vances, and economic

uph eaval h ave triggered competitive turmoil. In this environment, th e future b elongs to

those managers who can improve performance while managing change; but doing so

requires getting results through engage d and committed employees. Human resource

management practices an d pol icies pl ay a big rol e in hel ping managers do this .

Here is another reason to study this book: you mi ght spend time as a human resource

manager. For example, about a thir d of large U.S. businesses surveyed appointed non-HR

managers to be their top human resource executives. Thus, Pearson Corporation (which

publish es this b ook) promoted the h ead of one of its publishing divisions to chief human

resource executive at its corporate headquarters. Why? Some think these people may be

better equipped to integrate the firm’s human resource activities (such as pay policies) with

the company’s strategic needs (such as by tying executives’ incentives to corporate goals).3

However most top human resource executives do have prior human resource experi

ence. About 80% of those in one survey worked their way up within HR. About 17% had

the HR Certification Institute’s Senior Prof essional in Human Resources (SPHR) desig

nation, and 13% were certified Professional in Human Resources (PHR). The Society 36 PART 1 • INTR ODU CTION

for Human Resource Management (SHRM) offers a brochure descri bing a lternative

career paths wit hin human resource management. 4 Find it at www.shrm.org.

HR for S mall Businesses

And here is one final reason to study this book:y ou may well end up as your own human

resource manager. More than half the people working in the United States today work for

small firms. Small businesses as a group also account for most of the 600,000 or so new

businesses created every year.5 Statistically speaking, therefore, most people graduating

from college in the next few years either will work for small businesses or will create

new small businesses of their own. If you are managing your own small firm with no h u

man resource manager, you’ll probably have to handle HR on your own. To do that, you

must be able to recruit, select, train, appraise, an d reward employees. There are special

HR Tools for Line Managers and Small Businesses features in most chapters. T hese show

small business owners how to improve their human resource management practices. Line and Staff Aspects of HRM

All managers are, in a sense, human resource managers, because they all get involved in ac

tivities such as recruiting, interviewing, selecting, and training. Yet most f irms al so h ave a

separate human resource department with its own human resource manager. How do the du-

ties of this d epartmental HR manager and h is or her staff rel ate to l ine managers’ h uman re

source duties? Let’s answer this by starting with short definitions of line versus staff authority. Line versus Staff Authority authority

Authority is the right to make decisions, to direct the work of others, and to give orders.

The right to make decisions, direct

In management, we usually distin guish between line authority and staff authority. Line

others’ work, and give orders.

auth ority gives managers the rig ht (or authority) to issue orders to ot her managers or

employees. It creates a superior–subordinate relationship. Staff authority g ives a man

ager the rig ht (authority) to advise other manag ers or employees. It creates an advisory line manager

relations hi p. Line managers h ave l ine authority. Th ey are auth orized to give ord ers. Staff

A manager who is authorized to

managers h ave staff authority. They are authorized to assist and advise line managers.

direct the work of subordinates

Human resource managers are staff managers. They assist and advise line managers in

and is responsible for accomplish

areas li ke recruiting, hiring, and compensation .

ing the organization’s tasks.

In practice, HR and line managers sh are responsibi lity for most human resource staff manager

activities. For example, human resource and line managers in about two-thirds of the

A manager who assists and advises

firms in one survey shared responsibi lity for skills training.6 (Thus, the supervisor mi ght line managers.

describe what training she thinks the new employee nee ds, HR might design the train

ing, and the supervisors might t hen ensure t hat the training is having the desired effect.)

Line Managers’ Human Resource Management Responsibilities

The direct handling of people always has been an integral part of ever y line manager’s

responsibility, from presi dent down to the first- line supervisor. For examp le, one company

outlines its line supervisors’ responsibilities for e ffective human resource management

under t he following general headings:

1. Placing the right person in the rig ht jo b

2. Starting new emplo yees in the or ganization (orientation)

3. Training employees for jobs that are new to them

4. Improving t he job performance of each person

5. Gaining creative cooperation an d developing smoot h working relationships

6. Interpreting the company’s policies and procedures

7. Controlling labor costs

8. Developing the abilities of each person

9. Creating and maintaining departmental morale

10. Protecting employees’ health and physical conditions

In small organizations, line managers may carr y out all these personnel duties

unassisted. But as the organization grows, line manag ers need the assistance, specialized

knowledge, and advice of a separate human resource staff. CHAPTER 1

MANAGING HUMAN R SOURC ES TODAY 37 The Human Resource Department

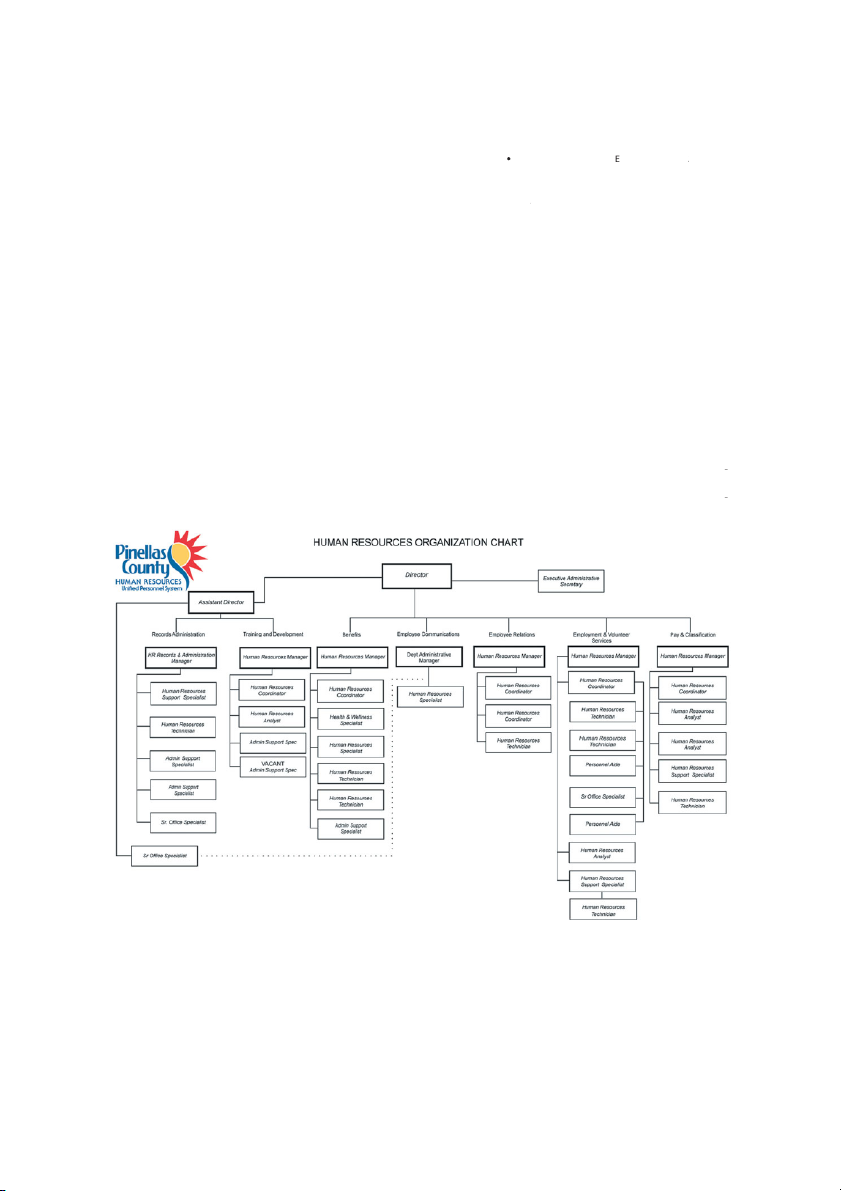

In l arger f irms, the human resource department provid es such sp ecial ized assistance.

Fig ure 1.1 sh ows human resource manag ement j obs in one org anization. Typical p ositions

include compensation and benefits manager, empl oyment and recruiting s upervisor,

training specialist, and employee relations executive. Examples of job duties include:

Recruiters: Maintain contacts within the community and perhaps travel extensively

to search for qualified job applicants.

Equal employment opportunity (EEO) representatives or affirmative action

coord inators: Investigate and resolve EEO grievances, examine or ganizational

practices for potential violations, and compile and submit EEO reports.

J ob analysts: Collect and examine detailed information about j ob duties to prepare j ob descriptions.

Compensation managers: Develop compensation plans and handle the employee benefits program.

Training specialists: Plan, organize, and d irect training activities.

Labor relations special ists: Advise management on all aspects of union– management rel ations.

Many big employers are taking a new look at how they organize their human resource

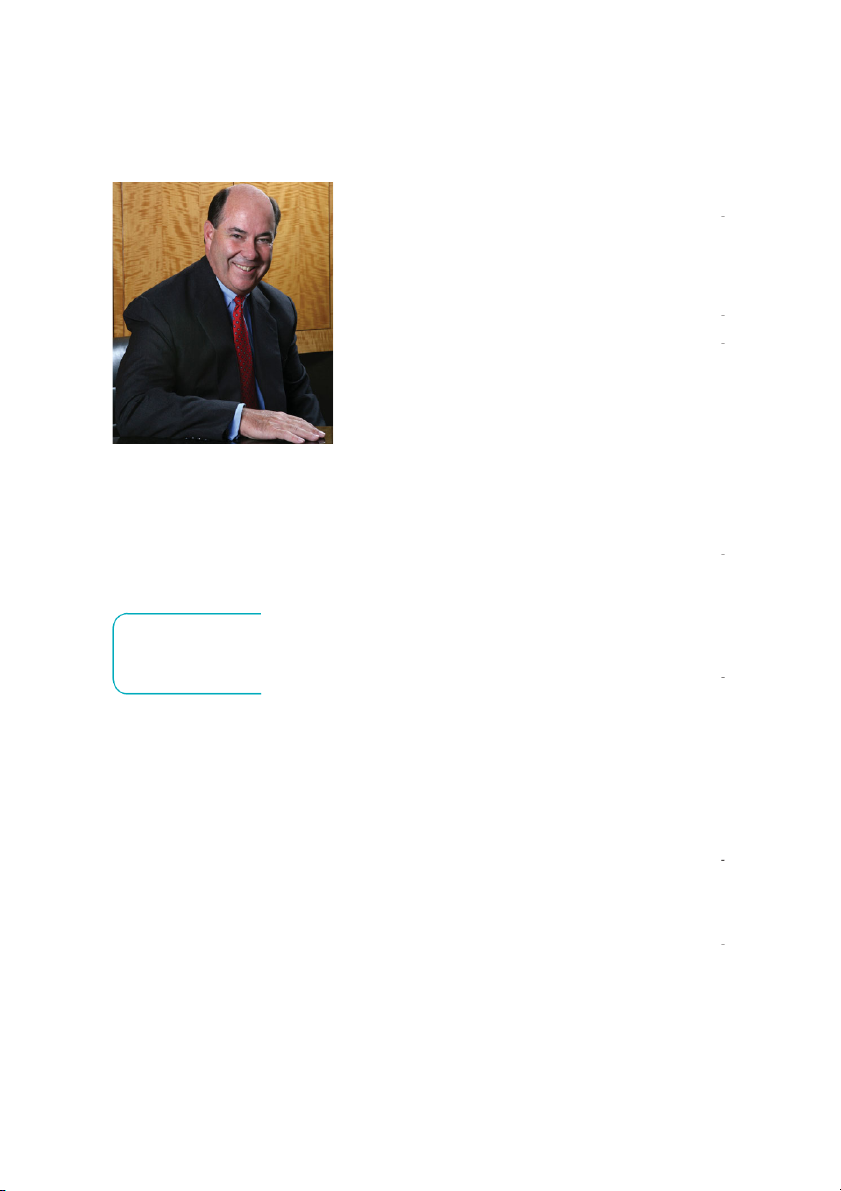

funct ions.7 For example, J. Rand all MacDonald, IBM’s former senior vice presi dent of hu

man resources, saw that the traditional human resource organization divides HR activities

into separate “silos” (as in Figure 1.1) such as recruitment, training, and employee rela

tions. MacDonald took a diff erent approach. He split IBM’s 330,000 employees into th ree FIGURE 1.1

Human Resource Department Organization Chart Showing Ty pical HR Job Titles

Source: “Human resource development organization chart showing t ypical HR job titles,” www.co.pinellas.fl.us/persnl/pdf/orgchart.pdf.

Courtesy of Pinellas County Human Resources. Reprinted with permission. 38 PART 1 • INTR ODU CTION

segments for HR purposes: executive and technical, managers, and rank

and file. Now separate h uman resource management teams (consisting of

recruitment, training , and pay specialists, for instance) focus on each em

ployee segment. Each team ensures the employees in each segment get the

specialized testing, training, and rewards they require.8

One survey found that 44% of the large firms they surveyed planned

to change how they organize and deliver their HR services.9 Most plan to

use technology to institute more “shared services” or “transactional”

arrangements.10 These will establ ish centralized HR units whose employees

are shared by all the companies’ departments to obtain advice on mat

ters such as discipline problems. The shared services HR teams offer their

services through intranets or central ized ca ll centers; th ey aim to pro

vide managers and employees with specialize d support in day-to- day HR

activities (such as changing b enefits plans). You may also find specialize d

corporate HR teams within a company. These assist top manag ement in

top-level issues such as developing the personnel aspects of th e company’s

long-term strategic plan. Embedded HR teams have HR generalists (also

known as “relationship managers” or “HR business partners”) assigned

to functional departments like sales and production. They provide the

J. Randall MacDonald and IBM

selection and other assistance th e d epartments need . Centers of e xperti se

reorganized its human resource

are basically specia lized HR consulting firms within t he company. For

management group to focus

example, one center might provide specialized advice in areas such as

on the needs of specific groups

organizational change to all th e company’s various units. of IBM employees.

Small firms (say, those with less than 100 employ ees) g enerally don’t Sour ce : IBM.

have the critical mass required for a full-time human resource manager (let

alone an HR department).11 Th e owner and his or her oth er managers (and perhaps th e

firm’s office manager) handle tasks suc h as placing help-wante d ads and signing employ

ees on. Gaining a command of the techniques in this book should help you to manage a

small firm’s human resources more effectively. LEARNING OBJECTIVE 2 THE TRENDS SHAPING HUMAN Describe with examples RESOURCE MANAGEMENT what trends are

Working cooperatively with line managers, human resource managers have long helped influencing human

employers h ire and fire employees, administer benefits, and conduct appraisa ls. How resource management.

ever, changes are occurring in the environment of human resource management that are

requiring it to pl ay a more central ro le in org anizations. These trends include workforce

diversity trends, technological trends, and economic trends. Figure 1.2 sums up major

trend s that are changing how employers an d t heir HR managers do things. Workforce Diversity Trends

The composition of the workforce will continue to change over the next few years;

specifically, it will continue to become more diverse with more women, minority group

members, and older workers in the workforce.12 Table 1.1 offers a bird’s eye view.

Between 1990 and 2020, the percent of the workforce that the U.S. Department of Labor

classifies as “white, non-Hispanic” will drop from 77.7% to 62.3%. At the same time, the

percent of t he workforce t hat it classifies as Asian will rise from 3.7% to 5.7%, and those

of Hispanic origin will rise from 8.5% to 18.6%. The percentages of younger work

ers will fall, while those over 55 years of age will leap from 11.9% of the workforce in

1990 to 25.2% in 2020.13 Many employers call “the aging workforce” a big problem. The

problem is that there aren’t enough young er workers to replace the projected number

of baby boom–era older workers (born roughly 1946–1964) retiring.14 Many emp loyers

are bring ing retirees back into the workforce (or just trying to keep them from leaving).

Demog raphic trends are also making finding and hiring of employees more challeng

ing. In the U.S., labor force growth is not expected to keep pace with job growth, with an

estimated shortfall of about 14 million college-educated workers by 2020.15 One study of

35 large g lobal companies’ senior human resource officers said “talent manag ement”—the CHAPTER 1

MANAGING HUMAN R SOURC ES TODAY 39 FIGURE 1.2 Important Trends and C onsequences f or Human I mportant T rends Resource Manag ement Their Conseq uences for HR Management

• Workforce Diversit y Trends • H R and Performance • Technology and Work force • H R and Performance and Trends Sustainability

• Globalization and Competition

• HR and Emp loyee Engagement Trends • H R and the Manager’s HR • Economic Challen ges Consequences for Philosophy • Economic and Workf orce • H R and Strategy HR Pro jection s

• Sustainability and Strateg ic M anagement H uman R esource M anagement • H R and Human Resource Competencies

• H R and The Manager’s S kills

• The HR Mana ger’s Competencies • HR and Et hi cs • H RCI Certification

TABLE 1.1 Demographic Groups as a Percent of the Workforce, 1990–2020 Ag e, Race, a nd Ethnicity 1990 2000 20 10 2020 Age: 16–24 7.9% 15.8% 13.6% 11.2% 25–54 70.2 71.1 66.9 63.7 55 11.9 13.1 19.5 25.2 Wh ite, non-Hispanic 77.7 7 2.0 67.5 62.3 Black 10.9 11.5 11.6 12.0 Asian 3.7 4.4 4 .7 5.7 Hispanic orig in 8.5 11.7 14.8 18. 6

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Economic News Release 2/1/12. www.bls.gov/news.release/ ecopro.t01.htm

a cquisition, development and retention of tal ent to fill the companies’ empl oyment needs— ranked as their top concern.16

With overa ll proj ected workforce shortfalls, many employers are h iring foreig n

workers for U.S. jobs. The H-1B visa program lets U.S. employ ers recruit skilled for

eign professionals to work in the United States wh en they can’t find qualif ied American

workers. U.S. employers bring in about 181,000 foreign workers per y ear under these

programs. Particu larly with h igh unemploy ment, such programs face opposition.17

O th er firms are sh ifting to nontrad itional workers. Nontraditional workers are th ose

who hold multiple j obs, or who are “temporary” or part-time workers, or those work

ing in al ternative arrangements (such as a mother–daughter team sh aring one cl erical

job). Others serve as “independent contractors” for specific projects. Almost 10% of

American workers—13 million people—fit this nontraditional workforce categ ory.

Technology and Workforce Trends

Technological change will continue to shift employment growth from some occupations to

others, while continuing to contribute to a rise in productivity (albeit slower productivity

growth th an in past years).18 When someone thinks of “technology jobs,” the jobs at com

panies like Apple and Google come to mind, but actually technology affects all sorts of j obs.

At Alcoa Aluminum’s Davenport Works plant in Iowa, a computer stands at each work post

to help each employee control his or her machines or communicate data. Walk through the

typical automobile manufacturing plant today, and hundreds of robots are doing many of 40 PART 1 • INTR ODU CTION Technology chang ed

t he natu re of work a nd therefore the skills that workers must bring to their jobs. For example high-tech jobs often mean replacing manual labor with highly trained technicians.

Source: Konstantin Kokoshkin/Global Look/ Corbis.

th e manual job s th at workers used to do. One f ormer college student b ecame a team l eader

in a plant with automated machines. He and his team type commands into computerized

mach ines that create precision parts.19 Thanks to information technology, about 17 million

people now work from remote locations at least once per month. “Co-working sites” offer

freelance workers office space and access to Wi-Fi and office e quipment.20 Even hu man

resource managers work different ly. For example, they use LinkedIn an d Facebook

(and many others) to recruit job candidates (see for example USAirForceRecruiting on

Facebook.com21, and online testing services such as www.criteriacorp.com) to do pre-hire

testi ng.22 They also use (as we’ll see) a variety of other mobile and onl ine tools to he lp

manage employee training, appraisal, compensation, and sa fety. Service Jobs

At the same time, there has been an enormous shift from manufacturing jobs to service

jobs in North America and Western Europe. Tod ay over two-thirds of the U.S. work

force is employe d in producing and delivering services, not products. By 2020, service-

p roviding industries are expected to account for 131 million out of 150 million (87%) of

wage and salary j obs overall . So in th e next few y ears, al most all the new j obs added in

t he United States will be in services, not in goods-producing industries.23 Human Capital

For employers, one big consequence of t hese demographic and technological trends is a

growing emphasis on their companies’ “human capital,” in other words on their workers’

k nowl edge, education, training , sk ills, and expertise. Service job s l ik e consul tant and

l awyer always emphasized work er education and knowl ed ge more than d id trad itional

manufacturing jobs. And toda y’s proliferation of IT-related businesses like Goog le and

Faceboo k d emands hig h levels of employee innovation, and t herefore human capital. But

as we’ve seen, even “traditional” manufacturing jobs are increasingly technology–based.

And bank tellers, retail clerks, bill collectors, mortg ag e processors, and packag e deliver

ers today need a level of technologica l sophistication they wouldn’t have need ed a few

years ag o. In our increasing ly knowledg e-based economy, “. . the acquisition and devel

opment of superior human capital appears essential to firms’ profitability and success.”24

For managers, the challenge of relying on human capital is that they have to man

age such workers differently. For example, empowering workers to make more decisions

presumes that they are selected, trained, and rewarded to make more decisions them

selves. Employers need new human resource management practices to select, train, and

engage these employees .25 The accompanying HR as a Profit Center illustrates how one

employer took advantage of its human capital. CHAPTER 1

MANAGING HUMAN R SOURC ES TODAY 41 HR AS A PROFIT CENTER

Boosting Customer Service

A bank installed special software that made it easier for its customer service representatives

to handle customers’ inquiries. However, the bank did not otherwise change the service

reps’ jobs in any way. Here, the new software system did help the service reps handle more

c alls. But otherwise, this bank saw no big performance gains.26

A second bank installed the same software. But, seeking to capitalize on how the new

software freed up customer reps’ time, this bank also had its human resource team upgrade

the customer service representatives’ jobs. This bank taught them how to sell more of the

bank’s services, gave them more authority to make decisions, and raised their wages. Here,

the new computer system dramatically improved product sales and profitability, thanks to

the newly trained and empowered customer service reps. Value-added human resource

practices like these improve employee perf ormance and company profitability.27 Talk About It – 1

If your professor has chosen to assign this, go to w ww.mymanagementlab.com to

d iscuss the following: Discuss three more specific examples of what you believe this

s econd bank’s HR department could have done to improve the reps’ performance. Globalization and Competition

Globalization refers to companies extend ing their sal es, ownersh ip, and/or manufac

turing to new markets abroa d. Thus Toyota builds Camrys in Kentucky, while Apple

a ssembl es iPhones in China. Free trade areas—agreements that red uce tariffs and barri

e rs among trading partners—further encourage international trade. NAFTA (th e North

American Free Trade Ag reement) and the EU (European Union) are examples.

Global ization has boomed for the past 50 or so years. For exampl e, the total sum of

U.S. imports and exports rose from $47 billion in 1960, to $562 bill ion in 1980, to ab out

$4.7 trillion recently.28 C hanging economic and politica l philosoph ies drove this boom.

Governments dropped cross-border taxes or tariffs, formed economic free trade areas,

a nd took other steps to encourage the free flow of trade among countries. The funda

mental economic rational e was that by doing so, all countries would gain, an d indeed,

e conomies around the world d id grow quickly until recently.

At the same time, globalization vastly increased international competition. More global

ization meant more competition, and more competition meant more pressure to be “world

class”—to l ower costs, to make employees more prod uctive, and to d o things better and less

e xpensively. Many firms responded successfully while others failed. When Swedish furni

ture retailer IKEA built its first U.S. furniture superstore in New Jersey, its superior styles

a nd management systems grabbed market share from domestic competitors, driving many

out of business. Such global competition is a two-way street. IBM, Microsoft, Apple, Face

book, and countl ess smaller American firms have major market shares around th e world.

As multinational companies j ockey for position, many transfer operations abroad,

not just to seek cheaper labor but to tap into new markets. For example, Toyota

has thousands of sal es employees based in America, while GE has over 10,000 employ

e es in France. The search for g reater efficiencies prompts some empl oyers to offshore

(export jobs to lower-cost locations abroad, as when Dell offshored some call-center jobs

to India). Some employers offshore even highly skilled jobs such as lawy er.29 Managing

the “people” aspects of globalization is a big task for any company that expands abroad—

a nd for its HR managers. Due to rising costs abroad and customer pushback, many firms

today are bring ing jobs back.30 Economic Challenges

Although g lobalization and technology supported a g rowing g lobal economy, the past

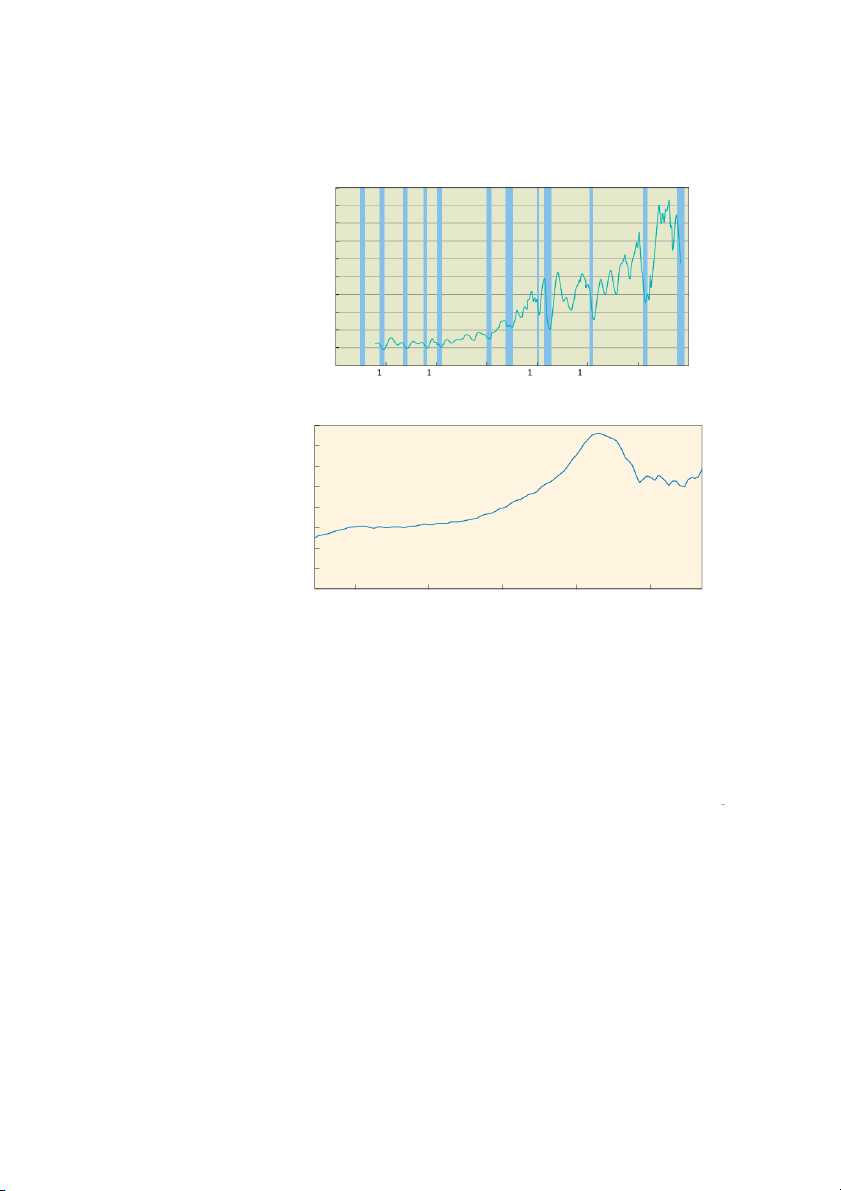

few years were di fficult economicall y. As you can see in Figure 1.3, Gross National 42 PART 1 • INTR ODU CTION FIGURE 1.3 900

Gross National Prod uct, 800 rs ) 1940–2010 la ol 700 f D

Source: “Gross National Product o 600 (GNP)” by FRED Economic illions 500

Data/St. Louis Fed., from Federal B Reserve Bank of St. Louis. go, 400 Aar 300 Ye 200 fr om e 100 hang (C 0 –100 1 940 9 50 960 1970 980 990 2000 2010

S had ed areas indi cate U .S. recessio ns.

2009 r esear ch. stl ouisfed. org FIGURE 1.4 200 Case-Shiller Home 175

Price Indexes June 1988– 150 June 20 13 12 5

Source: S&P Dow Jones In dices LLC. Assessed September 30, 100 2013. 75 50 2 5 1 990 1995 2000 2005 20 10

Product (GNP)—a measure of the United States of America’s total output— boomed

between 2001 and 2007. During this period, home prices (see Figure 1.4) leaped as

much as 20% per year. Unemployment remaine d docile at about 4.7%.31 Then, around

2007–2008, all these measures fell off a cliff. GNP fell. Home prices dropped by 10% or

more (depending on city). Unemployment nationwide soon rose to more th an 10%.

Why did a ll this happen? It’s complicate d. Many governments strippe d away ru les and

regulations. For example, in America and Europe, the rules that prevente d commercial

banks from expanding into new businesses such as investment banking were relaxed. Giant,

multinational “financial supermarkets” such as Citibank emerged. With fewer regulations,

more businesses an d consumers were soon deep ly in debt. Home buyers bought homes

with little money down. Banks freely lent money to developers to build more homes. For

almost 20 years, U.S. consumers spent more than they earned. The United States became a

debtor nation. Its ba lance of pa yments (exports minus imports) went from a healthy posi

ti ve $3.5 billion in 1960, to a huge minus (imports exceeded exports) $497 b ill ion deficit

more recently.32 The only way the countr y could keep buying more from abroad than it

sold was by borrowing money. So, much of t he boom was bui lt on debt.

Around 2007, all those years of accumulatin g debt ran their course. Banks and

other financial institutions found themselves owning trillions of dollars of worthless

l oans. Governments stepped in to try to prevent th eir coll apse. Lending d ried up. Many

businesses and consumers stopped buy ing. The economy tanked.

Economic and Workforce Projections

Economic trends are pointing up toda y, and hopefully they will continue to do so. For

example, the unemployment rate had fa llen from a high o f more than 10% a few years

ago to around 6% in 2014, and economic activity was also picking up. CHAPTER 1

MANAGING HUMAN R SOURC ES TODAY 43

However, th at d oesn’t necessarily mean clear sailing for the economy. For one thing ,

the “Great Recession” of 2007–2009 certainly grabbed every one’s attention. After see

ing the economy tank the wa y it did, many corporations became hesitant to spend big

money expanding factories and equipment. The financial meltdown and writing off

excessive debt left banks reluctant to make new loans, so prospective small business own

ers find it hard to start new businesses. With their mortgages (often still) underwater,

their credit card and tuition loan debts still hanging over them, and many still without

good jobs, consumers are understandably wary about pulling out all the stops when it

comes to spend ing.33 The Federal Reserve Boar d, which supported economic expansion

after the Great Recession, started reducing support in 2014 (because the economy was

l ooking better, and because of the huge debts it had run up supporting the expansion).

At the same time, productivity increases are slowing, which may further retard economic

growth.34 And after what the world went through in 2007–2009, it’s doub tful that the

deregulation, leveraging, and globalization that drove economic growth for the previous

50 years will continue unabated.

Compl icating all this is the fact th at th e l ab or force in America is growing more

sl owly than expected (which is not good, b ecause if empl oyers can’t get enough work

ers, they can’t expand). To be precise, th e Bureau of Labor Statistics projects the labor

force to grow at 0.5% per year throug h 2012 to 2022, compared wit h an annual growth

rate of 0.7% during the 2002–2012 decade.35 Why the sl ower labor force growth? Mostly

because with baby boomers aging, the “labor force participation rate” is declining—in

other words, the percent of the population that wants to work is declining. Add it all up,

and the b ottom line looks to be slower economic growth ahead. The Bureau of Labor

Statistics projects that gross domestic product (GDP) will increase by 2.6% annually

from 2012 to 2022, slower than the 3% or higher rate that more or less prevailed from the

mid -1990s th rough the mid-2000s.3 6

THE UNBALANCED LABOR FORCE There is other economic news. Al th ough th e unemploy

ment rate is d ropping, it’s doing so in part because fewer people are looking for jobs

(remember the shrinking labor participation rate). Furthermore, demand for workers

is unbalanced; for example, an “average” unemployment rate of, say, 6% masks the fact

that the unempl oyment rate for, say, recent college graduates was much higher, while

that of software eng ineers was much lower.37 In fact, almost half of empl oyed U.S. college

graduates are in jobs that generally require l ess than a four-year coll ege education.38

Why did this happen? In brief , because most of th e jobs th at th e economy added in

the past few years don’t require coll ege educations, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics

say s that will probably continue. Occupations th at do not typically require postsecondary

ed ucation employ ed nearly 2⁄ of workers in 2012.39 And, “2 ⁄ rds of the 30 occupations

with the largest proj ected employment increases from 2012 to 2022 typically do not

require postsecondary education for entry.”40

The result is an unbalanced lab or force: in some occupations (such as high-tech)

unemployment rates are low, while in others unemployment rates are still very high;

recruiters in many companies can’t find candidates, while in oth ers there’s a wealth of

can didates41; and many people working today are in jobs “below” their expertise (which

may, or may not, help to explain why about 70% of employ ees report being ps ychologi

c all y disengaged at work). In any case, slow growth and l abor unbalances mean more

pressure on employ ers (and their human resource managers and l ine managers) to get

the best efforts from their employees. CONSEQUENCES FOR TODAY’S LEARNING OBJECTIVE 3 Discuss at least five HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGERS c onsequences today’s

Trends like these bode well for human resource management. For much of the 20th cen trends have for human

tury, “personnel” manag ers focused mostly on day-to-day activities. In the earliest firms, resource management.

they took over hiring and firing from supervisors, ran the payroll department, and ad

ministered benefits plans. As expertise in testing emerged, the personnel department 44 PART 1 • INTR ODU CTION

pl ay ed a bigger role in empl oy ee sel ection and training.42 New union l aws in the 1930s

added “Helping the employer deal with unions” to its duties. With new equal employ

ment laws in the 1960s, employers be gan relying on HR for avoiding discrimination claims.43

Today’s employers face new challenges. Demographic trends make finding and hir-

ing employees more difficult and make managing diversity more important. Employers

must also focus on addressing the equal employment laws that diversity has engendered.

Technology and service trends mean employers must effectively manage their employ-

ees’ knowledge, skills, an d expertise—t heir human capital. G lo balization requires special

HR expertise. A s lower-growing economic pie means more pressure on employers to get

the best efforts from their employ ees. Employ ers expect their “people experts”—their

h uman resource managers—to d eal with th ese challenges. Here is h ow h uman resource managers are responding. HR and Performance

Employers expect their human resource managers to help lead their companies’

perf ormance-improvement eff orts. Today’s h uman resource manager is in a powerful

position to d o th is, and uses th ree main levers to do so. Th e f irst is the HR department

lever. He or she ensures that the human resource management function is delivering

its services efficiently. For example, t his mi ght include outsourcin g certain HR activi

ties such as b enefits management to more cost-effective outsid e vend ors, controlling

HR function headcount, and using technology suc h as portals an d automate d online

employee prescreening to deliver its services more cost-effectively.

The second is the employee costs l ever . For example, the human resource manager

takes a prominent role in ad vising top management about the company ’s staffing l evels,

and in setting and controlling the firm’s compensation, incentives, and bene fits policies.

The third is thes trateg ic results lever. Here the HR manag er puts in place the policies

and practices that produce t he emp loyee competencies and ski lls the company needs

to ach ieve its strategic goals. For example, (see the HR as a Profit Center feature on

page 41) the bank’s new software helped its customer service reps improve their

perf ormance, thanks to new human resource training and compensation practices. We’ll

encounter many similar examples in t his book.

HR AND PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT Improving per formance requires being able to

measure what you are doing. For example, when IBM’s J. Randall MacDonald needed

$100 million to reorganize its HR operations several years ago, he told top management,

“I’m going to deliver talent to you that’s skilled and on time and ready to be deployed.

I will be abl e to measure the skills, te ll you what ski lls we have, what [skills] we don’t have

[and ] then sh ow you how to fill th e gaps or enhance our training.”44

Human resource managers use performance measures (or “metrics”) to validate

claims li ke these. For examp le, median HR expenses as a percentag e of companies’ total

operating costs average just under 1%. On average, there is about 1 human resource staff person per 100 empl oy ees.45

HR AND EVIDENCE-BASED MANAGEMENT Basing decisions on such evidence is the heart

of evidence-based human resource management. This is the use of data, facts, analytics,

scientific rigor, critical evaluation, and critically evaluate d research/case studies to

support human resource management proposa ls, decisions, practices, and conc lusions.46

Put simply, evidence-based human resource management means usin g the best-available

evidence in making decisions about the human resource management practices you are

focusing on.47 The evidence may come from actual measurements (such as, how did the

t rainees like this prog ram?). It may come from existing data (such as, what happened

t o company profits after we installed th is training program?). Or, it may come from

p ubl ish ed research stu dies (such as, wh at does the research literature conc lude ab out the

best way to ensure that trainees remember what they learn?).

Sometimes, companies transl ate their f ind ings into what management gurus call

high-performance work systems, “sets of human resource management practices that CHAPTER 1

MANAGING HUMAN R SOURC ES TODAY 45

together produce superior employ ee performance.”48 For example, at GE’s assembly plant

in Durham, North Carolina, highly trained self-directed teams produce high -precision

aircraft parts. We’ll discuss performance measurement and high-performance work sys tems in Chapter 3

HR AND ADDING VALUE The bottom line is that today’s employers want their HR managers

to add value by boosting profits and performance. Professors Dave Ulrich and Wayne

Brockbank describe this as the “HR Value Proposition.”49 They say human resource

programs (such as screening tests) are just a means to an end. The human resource

manager’s ultimate aim must be to add val ue. Adding value means h elping the firm and

i ts employees improve in a measura ble way as a result of th e human resource manager’s

a ctions. We’ll see in this book how human resource practices do this. For example, we’ll

use, in each chapter, HR as a Profit Center features like the one on page 41 to ill ustrate this.

HR and Performance and Sustainability

In a world where sea levels are rising, glaciers are crumbling, and increasing numbers of

people view financial inequity as outrageous, more and more peopl e say that businesses

c an’t just measure “performance” in terms of maximizing profits. They argue instead

that companies’ efforts should be “sustainable,” by which they mean judged not just on

profits, but on their environmental and social performance as well.50 As one example,

PepsiCo has a goal to deliver “Performance with Purpose”—in other words, to deliver

financial performance while also achieving human sustainability, environmental sus-

tainability, and talent sustainabil ity. PepsiCo wants to ach ieve business and f inancial suc

c ess while leaving a positive imprint on society (www.pepsico.com, then click What We

Believe, and t hen Perf ormance with Purpose). PepsiCo is not alone. In one survey, about

80% of large surveye d companies report their sustainabil ity performance.51 We’ll see that

sustainability trends have important consequences for human resource manag ement. HR and Employee Engagement employment engagement

Empl oyee engagement refers to being psych ologically involved in, connected to, and The e xtent to which a n

c ommitted to getting one’s jobs done. Engaged employees “experience a hig h level of

organization’s employees are

c onnectivity with th eir work tasks,” and th erefore work hard to accomplish their task- psychologically involved in,

related goals.52 Engaged employees do their jobs as if th ey own th e company. connected to, and committed

Employee engagement is important because it drives performance. For example (as to getting one’s j obs done.

we will discuss more fully inCh apter 3), base d on one Ga llup survey, business units with

the highest levels of employee engagement have an 83% chance of performing above t he

company median; those with the lowest employ ee eng agement have only a 17% chance.53

A survey by consu ltants Watson Wy att Worldwide concl uded that companies with highly

engaged employees have 26% higher revenue per empl oyee.54

The problem for employers is that, depend ing on the study, onl y about 21–30% of

employ ees nationally are engaged.55 For example, Gallup recentl y found th at ab out 30%

of employees were eng aged, 50% were not eng aged, and 20% were actively disengaged (anti-management).56

We will see in this book that managers improve empl oyee engagement by taking

concrete steps to do so. For example, after facing serious challeng es a few y ears ago, Kia

Motors (UK) turned its performance around, in part by boosting employee engagement.57

As we will discuss more fully in Chapter 3, they did this with new HR programs, includ

i ng new leadership development programs, newempl oyee recognition programs, improved

internal communications programs, a ne w employee development program (including, for

instance, using the company’s appraisal process to identify employees’ training needs),

and by modif ying its compensation and other pol icies. We use special Employee Engage

ment Guide for Manag ers sections in Chapters 3–14 to show how managers use human

resource activities such as recruiting and selection to improve employee engagement.

HR and the Manager’s Human Resource Philosophy

People’s actions are always based in part on the basic assumptions they make; this is espe

c ially true in regard to human resource management. The basic assumptions you make 46 PART 1 • INTR ODU CTION

about people—Can t hey be trusted? Do th ey dis like work? Why do they act as the y do?

How should they be treate d?—tog ether comprise your phi losophy of human resource

management. And every personnel decision you make—the people y ou hire, the training

you provide, your leadership style, and the like—reflects (for better or worse) this basic p hilosophy.

How do you go about developing such a philosophy? To some extent, it’s preor

dained. There’s no doubt that you will bring to your job an initial philosophy based

on your experiences, education, values, assumptions, and background. But your phi-

l osophy doesn’t h ave to be set in stone. It sh ould evol ve as you accumul ate knowled ge

and experiences. For example, after a worker uprising in China at the Foxconn plant

owned by Hon Hai that assembles Apple iPhones, the personnel philosophy at the

pl ant softened in response to its empl oyees’ and Apple’s discontent.58 In any case, no

manager should manage others without first understanding the personnel philosophy

that is driving his or her actions.

One of the th ings mold ing your own phil osophy is that of your organization’s top

management. While it may or ma y not be stated, it is usually communicated by their ac-

tions and permeates every level and department in the organization. For exampl e, here

is part of the personnel p hi losophy of the founder of t he Polaroid Corp., stated many years ag o:

To give everyone working for the company a personal opportunity within the com

pany for full exercise of his talents—to express his opinions, to share in the progress

of th e company as far as h is capacity permits, and to earn enough money so that

the need for earning more will not always be the first thing on h is mind . The op

portunity, in short, to make his work here a fully rewarding and important part of h is or h er life.59

Current “best companies to work for” lists include many organizations with simi

lar philosophies. For example, the CEO of software giant SAS has said, “ We’ve worked

hard to create a corporate culture that is based on trust between our employees and the

company . . a culture t hat rewar ds innovation, encourages employees to try new things

and yet doesn’t penalize them for taking chances, and a culture that cares about em

ployees’ personal and professional g rowth.”60 The accompanying HR in Practice feature shows some exampl es. The SAS Institute, Inc. is built on 200 tree-covered acres in Cary, N.C. SAS is the world’s largest software company in private hands. Its 8,000 employees around the globe recently generated about $1.1 billion in sales. The company is famous f or its progressive benefits and employee relations programs. Sour ce : AP Photo/Ka re n Tam CHAPTER 1

MANAGING HUMAN R SOURC ES TODAY 47 HR IN PRACTICE

SAS and Google Put Their HR Philosophies into Practice

Companies with positive employee relations tend to be the sorts that show up in an

nual “Best Companies to Work For” lists. For example, at the software company SAS,

which has extraordinary benefits and a history of not laying off employees, one long-term

employee said, “I just can’t imagine leaving SAS, and I felt that way for a very long time .

if somebody offered to double my salary, I wouldn’t even think about it.”61 Employee turn

over, about 20% in software companies, is about 3% at SAS.62 Similarly, when Google

founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin began building Google, they set out to make it a

great place to work. Google doesn’t just offer abundant benefits (and stock options).63

Google’s team of social scientists run little experiments, for instance to determine if

s uccessful middle managers have certain skills, and what’s the best way to remind

p eople to contribute to their 401(k)s.64 The aim is to keep employees happy (and Google successful and growing). Talk About It – 2

If your professor has chosen to assign this, go to w ww.my managementlab.com to

d iscuss the following question. Do you think that maintaining positive employee

relations is particularly important given today’s competitive environment? Give examples o f why or why not. Watch It

How does a company actual y go about putting its human resource philosophy into ac

tion? If your professor has chosen to assign this, g o to www.mymangementlab.com

to watch the video Human Resource Management (Patagonia) and then answer the

questions to show what you do in this situation. HR and Strategy

We’ve seen that strengthening organizational performance and b uilding engaged work

teams puts a company ’s human resource managers in a more central role. One conse-

quence is that HR manag ers tend to be more invol ved tod ay in devel oping th e company’s

strategic plan. Most companies have a strategic plan, a pl an for h ow it will b alance its

internal strengths and weaknesses with external opportunities and threats in order to

maintain a competitive advantage. Traditionally , the j ob of developing such a plan is

one primarily f or the company’s operating (line) managers. Thus, company X’s president

migh t decide to enter new mark ets, drop prod uct lines, and embark on a five-year cost-

c utting plan. Then the president would more or less leave the personnel implications of

that plan (hiring or firing workers, and so on) to be carried out by the human resource

manager. Toda y, human resource managers usually get much more involved in develop

ing and implementing strateg ic plans.

Chapter 3 (Human Resource Management Strategy and Anal ysis) expands on this. In

strategic human resource

brief, we will see there that strategic human resource management m ean s formulating management

and executing human resource policies and practices that produce th e employ ee competen

Formulating and executing human

cies and behaviors the company needs to achieve its strategic aims. The bas ic idea be hind

resource policies and practices that

strategic human resource manag ement is this: In formulating human resource manage produce the employee competen

ment policies and practices, the manager’s aim should be to produce the employee skills

cies and behaviors the company

a nd behaviors that the company needs to achieve its strategic aims. So, for example,

needs to achieve its strategic aims.

when Yahoo’s CEO wanted to improve her company’s innovation and productivity a few

years ago, she turned to her new HR manager (a former investment banker). Yahoo then

instituted many new HR policies. It eliminated telecommuting to bring workers back

to the office where they could continuously interact, and adopted new benefits (such as 48 PART 1 • INTR ODU CTION

16 weeks’ paid maternity l eave) to l ure new engineers and to mak e Yahoo a more attrac

t ive place in which to work.65

We will use a model startin g with Chapter 3 to illustrate this idea, but in brief t he

model follows this three-step sequence: Set the firm’s strategic aims Pinpoint the

employee behaviors and skills we need to achieve these strategic aims Decide what

HR policies and practices will enable us to produce these necessary employee behaviors and skills.

Sustainability and Strategic Human Resource Management

As mentioned earlier, sustainability trends have important consequences for human re-

source mana gement. Strategic human resource management means putting in place the

h uman resource pol icies and practices that produce th e employee skills and b eh aviors

that are necessary to achieve the company’s strateg ic g oals. When those strateg ic g oals

include sustainabilit y issues, then it follows that human resource mana gers should have

HR policies to support these goals .

For example, recall that PepsiCo wants to deliver Performance with Purpose, in

other words financia l per formance w hi le a lso achieving human sustainabi lity, environ

mental sustainability, and talent sustainability. PepsiCo has goals to measure financial

perf ormance, for instance in terms of sh areholder value and long -term f inancial per

formance. Its goa ls for human sustaina bility inclu de providing clear nutrition informa

tion on products. Environmental sustainability goals include protecting and conserving

g lobal water supplies. Talent sustainability goa ls include respecting workp lace human

ri ghts and creating a safe and healthy wor kpl ace.66

P epsiCo’s human resource manag ers can have an important impact on helping the

company achieve t hese goals .67 For example, it can use its workforce planning processes

to help determine how many and what sorts of environmental sustainability (“green”)

jobs the company will need to recruit for. It can work with top management to institute

flexible work arrangements that help sustain the environment by reducing commuting.

It can change its employee or ientation process to include more emphasis on socializ

ing new employees into PepsiCo’s sustaina bi lity goals. It can mo dify its perf ormance

appraisal systems to measure the extent to which managers and employees are successful

in reaching t heir individua l sustaina bi lity goals. T hey can put in pl ace incentive systems

th at motivate employees to achieve PepsiCo’s sustainab il ity goal s. Th ey can institute

safety and health practices aimed at eliminating unsafe conditions and improving worker

safety. They can ma ke Talent Sustaina bility part o f t he company’s HR Philosophy, for

example by emphasizing the need to foster a respect fu l work environment.68 And they

can institute employee rel ations programs aimed at maintaining positive employee

relations and ensuring that employees have a safe, fulf illing, and respectful tenure at t he

company. The bottom line is that human resource mana gement can play a central role in

supporting a company’s sustainabil ity efforts.

HR and Human Resource Competencies69

It’s more complicated being a human resource manager to day. Tas ks like formulating

strategic plans and making data-based decisions require new skills. HR mana gers can’t

just b e good at trad itional personne l tasks l ike hiring and training (although th at is still

very important). Instead, they must “speak the CFO’s lang uage” by defending human

resource plans in measurable terms (such as return on investment).70 To create strate

gic plans, the human resource manager must understand strategic plannin g, market

ing, production, and finance.71 As companies merge and expand abroad, he or she must

be able to formulate and implement large-scale org anizational chang es, drive employee

engagement, and redesign organizational structures and work processes. None o f this is easy. HR and the Manager’s Skills

T his book aims to help managers devel op the ski lls t hey’ ll nee d to carry out t he

human resource management-related aspects of their jobs, such as recruiting , selecting , CHAPTER 1

MANAGING HUMAN R SOURC ES TODAY 49

training , appraising , and incentivizing employees, and providing th em with a safe and

fulf ill ing work environment.72 Special Building Your Manag ement Skills features in each

chapter cover matters such as h ow to interview j ob candid ates and train new employ

e es. Special HR Tools for Line Managers and Small Businesses features aim to provide

small business owners and managers in particular with techniques they can use to better

manage their small businesses. Special Know Your Employment Law features highlight

the practical information all managers need to make better HR-related decisions that

work. Employee Engag ement Guide for Managers features show how managers improve e mpl oyee engagement.

The Human Resource Manager’s Competencies

Aside from skills like these, what sorts of competencies does someone need to be an ef

fective human resource manager today? When asked “Why do you want to be a human

resource manager?” many people basically say, “Because I’m a people person.” Being

sociable is certainly important. But Figure 1.5 sh ows some other competencies experts have unearthed.

P rofessor Dave Ul rich an d his colleag ues say that toda y’s human resource manag ers

need to be strategic positioners—for instance, they have to have t h e breadth of business

knowledge necessary to be able to help top management develop its strategic plan. They

have to be c redible activists—for instance, th ey need th e knowl edg e and expertise and

leadership abilities that makes them “both c redibl e (resp ected, ad mired, l istened to) and

active (offers a point of view, takes a position, challenges assumptions).”73 They should

be capability builders—f or instance, abl e to create a fulf illing work environment for

e mpl oyees and al ign the empl oyees’ efforts with the company’s goals. They sh ould be

change champions—for instance, able to initiate a broad company-wide change, and

then put in place the HR policies necessary to sustain that change. They should be HR

Innovators and Integrators—f or instance, abl e to id entify new peopl e-rel ated solutions

for improving the company and to optimize human capital through workforce planning

and anal ytics. And t hey should b e techno logy proponents—for instance able to put in

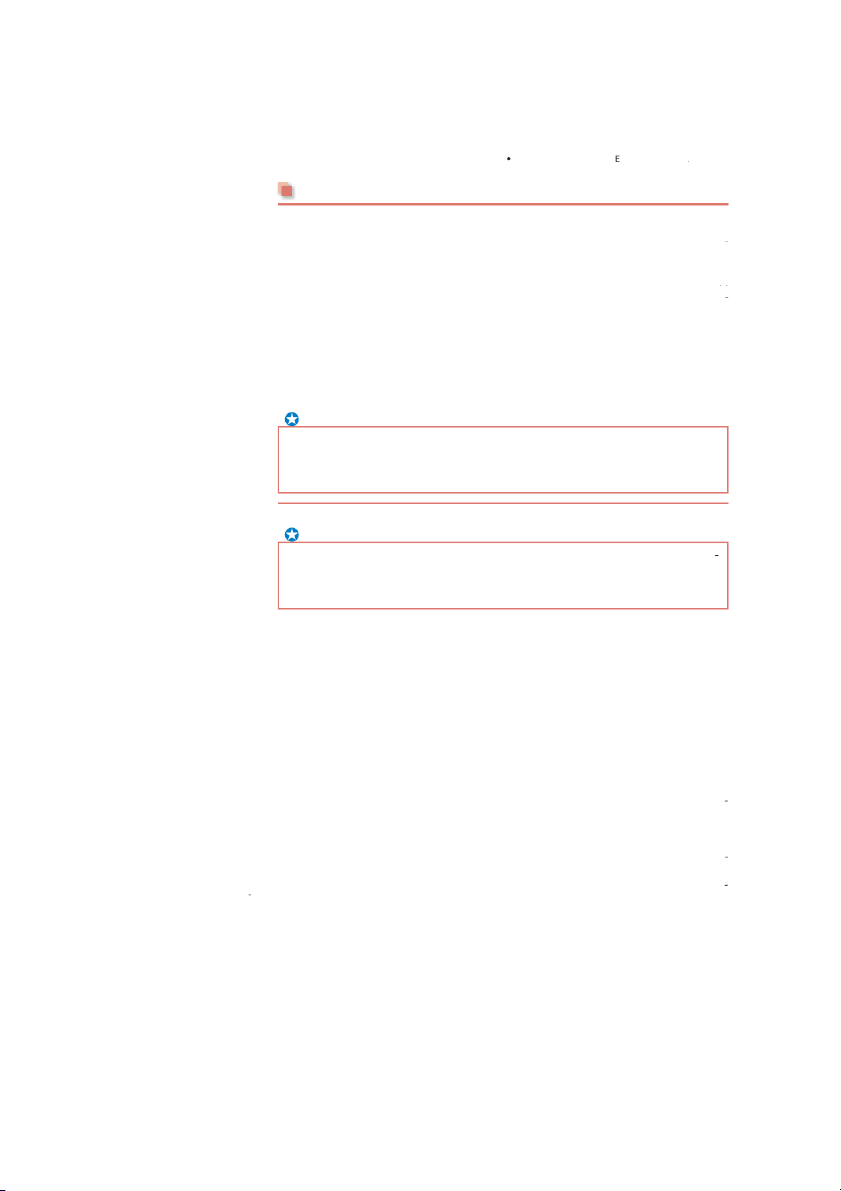

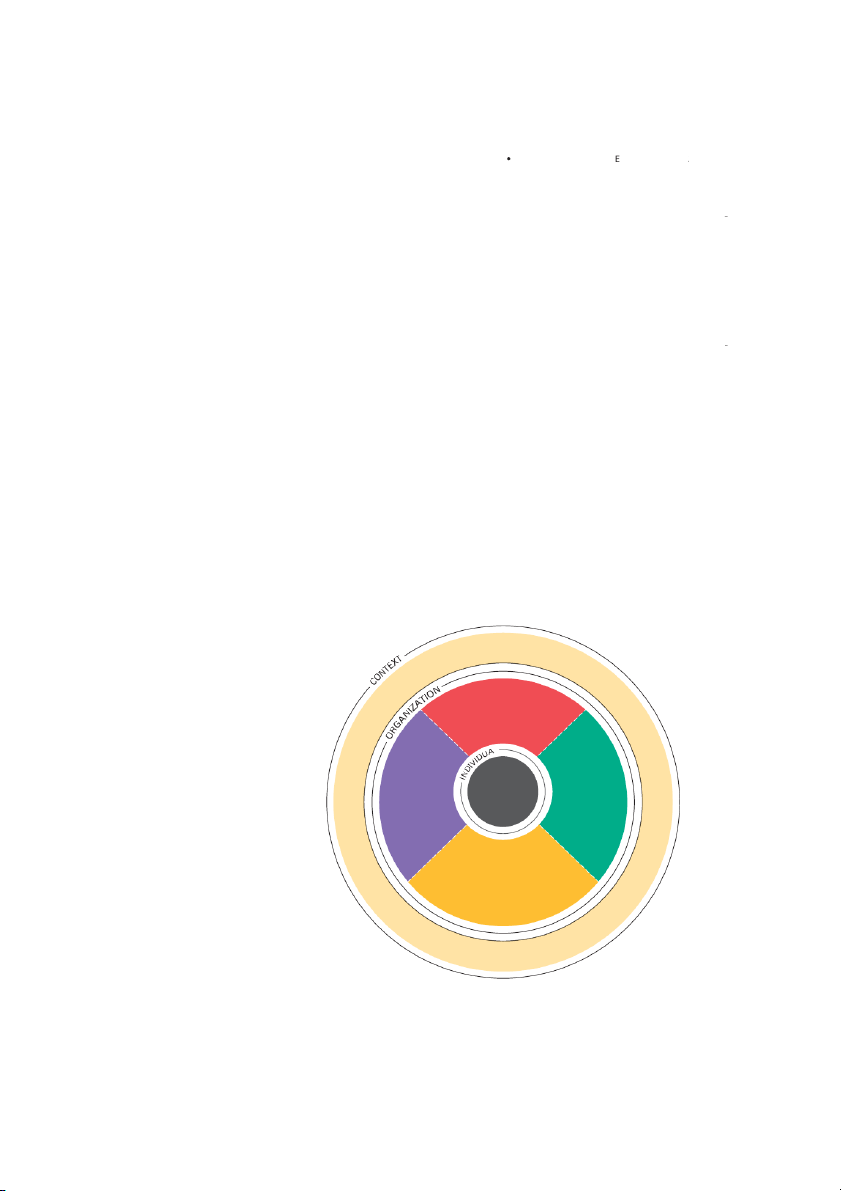

place new technology that helps the company recruit applicants via social med ia. FIGURE 1.5 The Huma n Resource S trate g ic P osit ione r

Manager’s Competencies

Source: The RBL Group, © 2012. Capability Builder L Change Credible Technology Champion Activist Proponent HR Innovator & Integrator 50 PART 1 • INTR ODU CTION HR and Ethics

Regrettably, news reports today are filled with stories of otherwise competent mana g

ers who have run amok. For example, prosecutors file d criminal charges a gainst several

Iowa meatpacking plant human resource managers who allege dly violate d employment

l aw by hiring children younger than 16. 74 Behaviors like these risk torpedoing even ot h ethics

erwise competent managers and employers. Ethics means the standards someone uses to

The principles of conduct governing

decide what his or her conduct should be. We will see that many serious workplace ethical

an individual or a group; specifical y,

issues—workplace safety and emplo yee privac y, for instance—are human resource man-

the standards you use to decide agement related.75 w hat your conduct should be. HRCI Certification

Many HR managers use certification to s how their mastery of mo dern human resource

management knowledge. The HR Certification Institute (HRCI) is an independent cer-

t ify ing org anization for human resource professionals (see www.hrci.org ). Throug h

t esting, HRCI award s several cred ential s, includ ing Professional in Human Resources

(PHR), and Senior Professional in Human Resources (SPHR). The evidence to date gen

erally suggests a positive relationship between human resource managers’ competence

as reflected by PHR or SPHR certification, and the human resource managers’ effective

ness.76 Managers can take an online HRCI practice quiz by going to www.hrci.org and

clicking on Exam Preparation and then on Sample Questions.77

The HRCI Knowl edge Base (see Append ix A of this book, pp. 515–523 addresses

seven main topic areas: Strategic Business Management, Workforce Planning and

Employment, Human Resource Development, Total Rewar ds, Employee and Labor

Relations, Risk Management, an d Core Knowledge. The space this book devotes to t hese

topics roughly f oll ows the HRCI weigh ting suggestions.

The Knowledge Base also lists about 91 specific “Knowledge of ” subject areas

withinthese seven main topic areas with which those taking the test should be familiar;

we use special Knowledge Base icons s tarting in Ch apter 2 to d enote coverage of HRCI k nowl ed ge topics. THE PLAN OF THIS BOOK LEARNING OBJECTIVE 4 O utline the plan of

This book has two main aims: to provide all future mana gers, not j ust HR managers, with t his book.

th e practical h uman resource sk ill s (for instance h ow to interview, train, engage, and

appraise employees) they nee d to produce an engaged and hig h-performing workforce;

and to cover the HRCI’s “A Body of Knowledge” in a relativel y compact and economical

14-ch apter soft cover format. Specia l main features—Employee Engagement Guide for

Managers, Bui lding Your Management S kills, HR Tools for Line Managers and Small

Businesses, and Know Your Equal Employment Law—help illustrate important points. The Chapters

We’ve organized the b ook as follows:

Part 1: Introduction (Chapters 1, 2, 3)

1. Managing Human Resources Today

2. Managing Equal Opportunity and Diversit y W hat y ou need to know about

equal opportunity laws as they re late to human resource manag ement activities

suc h as interviewing, selectin g employees, and eva luating per formance.

3. Human Resource Strategy and Analysis What is strategic planning, strategy

formulation and execution, and evidence-based mana gement.

Part 2: Staffing: Workforce Planning and Employment (Chapters 4, 5, 6)

4. Job Analysis and Talent Management What is talent management? How to

analyze a job and how to determine the job’s requirements, specific duties, and

responsibilities, as well as what sorts of people nee d to be hired.

5. Personnel Planning and Recruiting Workforce planning and techniques for recruiting employees . CHAPTER 1

MANAGING HUMAN R SOURC ES TODAY 51

6. Selecting Employ ees Wh at manag ers sh ould know about testing, interviewing , and se lecting employ ees.

Part 3: Training and Human Resource Development ( Chapters 7, 8, 9) C

7. Training and Developing Employees Providing the training and develop- H A

m ent necessary to ensure that your employees have the knowledge and skills P T

required to accomplish their tasks. E R

8. Performance Management and Appraisal Techniques for managing and 1 appraising performance.

9. Managing Careers Causes of and solutions for employee turnover, and how

to h elp employees manage their careers.

Part 4: Compensation and Total Rewards (Chapters 10, 11)

10. Developing Compensation Pl ans How to develop market-competitive pay plans.

11. Pay f or Performance and Employee Benef its Devel oping total reward

programs, including incentives and benefits plans for employees.

Pa rt 5: Employee and Labor Relations (Chapters 12, 13, 14)

12. Maintaining Positive Employee Relations Developing employee relations

programs and employee involvement strategies; ensuring eth ical and f air

treatment through d iscipl ine and grievance processes.

13. Lab or Rel ations and Collective Bargaining T he relations between unions and

management, including union-organizing campaigns, negotiating and agreeing

on coll ective-bargaining agreements between unions and management, and manag ing the ag reement.

14. Improving Occupational Safety, Health, and Risk Management The causes of

accid ents, how to make th e workplace safe, and laws governing your responsi

bilities in regard to employ ee safety and health.

Part 6: Special Issues in Human Resource Management (Modules A, B)

M odu le A: Managing HR Globall y Applying human resource management

policies and practices in a global environment.

M odule B: Managing Human Resources in Small and Entrepreneurial Firms

Special HRM methods small business managers can use to compete more successfully. Review MyManagementLab

Go to mymanagementlab.com to complete the problems marked with this icon SUMMARY

1. Staffing, personnel management, or human resource

relations, healt h and sa fety, and fairness concerns.

manag ement include activities such as recruiting,

The HR manager and his or her department provide

selecting, training, compensating, appraising, and

various staff services to line management, including

d eveloping. Human resource management is the

a ssisting in the hiring, training, evaluatin g, reward

process of acquiring , training, appraising , and com

ing, promoting, disciplining, and safety of employees

pensating employees, and of attending to their labor

a t all levels. HR management is a part of every line 52 PART 1 • INTR ODU CTION

manager’s responsibilities. These responsib ilities

achieving certification to deve lop and display one’s

include placing the right person in the rig ht job and competencies.

th en orienting, training , and compensating the per

4. This book aims to hel p manag ers develop th e sk ills C H

son to improve his or her job performance. Reasons

th ey’ll need to carry out the human resource A

every manager needs HR expertise include avoiding

management-related aspects of their jobs, such as P T

HR mistakes (such as high turnover); getting results;

recruiting, selecting, training, appraising, and in E R

spending time as an HR manager; and being in a

centivizing employees, and providing them with 1

small business where the owner needs to do most

a safe and fulfilling work environment. There is a HR tasks him or herself.

special emphasis on building skill s and in fostering

2. Trends are requiring HR to play a more central role

employee engagement. Special Building Your Man

in organizations. These trends include workforce

agement Skills features in each chapter cover matters

diversity, tech nolog ical ch ang e, globalization, and

such as how to interview jo b candidates an d train economic challeng es.

new empl oyees. Special HR Tool s for Line Mana g

3. The consequences for HR of such trends include

ers and Small Businesses features aim to provide

more focus on performance (incl uding measuring

small business owners and managers in particular

performance and doing so in terms of sustainab il

with techniques they can use to better manag e their

ity ); needing to foster employ ee eng agement and a

small businesses. Special Know Your Employment

supportive HR ph ilosophy ; devel oping strateg ic HR

Law features highlig ht the practical information all

skills (including for implanting th e company’s sus

manag ers need to make better HR-related decisions

tainabil ity pl ans); developing the necessary HR skills

th at work. Employee Engagement Guid e for Manag

and competencies; und erstanding th e ethica l conse

ers features show how managers improve employee

quences of one’s d ecisions; and (f or HR managers) engagement. KEY TERMS organization 34 line manager 36 manager 34 staff manager 36 managin g 34 empl oyment engagement 45 management process 34

strategic human resource management 47

h uman resource management (HRM) 34 ethics 50 authority 36 Try It

How would you do applying the concepts and skills you learned in this chapter? If

your professor has chosen to assign this, go to www.mymanagementlab.com

and complete the Human Resource Management simulation. DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1-1. What is human resource management?

1-4. Wh y is it essential for managers to know about

1-2. Explain with at least five examples why “a HRM concepts and tec hniques?

knowledge and proficiency in HR manag ement

1-5. Discuss with examples four important issues

concepts and techniques is important to all

influencing HR management today. supervisors or manag ers.”

1-6. Explain HR manag ement’s role in relation to the

1-3. Discuss the chang ing trends in workforce firm’s line management.

d iversity. How do these the trends influence

1-7. Compare the authority of line and staff HRM?

managers. Give examples of each.