Preview text:

1099050x, 0, DOI: 10.1002/hrm.22159 D o w n loaded

O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E from https://online

Gender diversity advantage at middle management: library.wile

Implications for high performance work system y .com/doi/

improvement and organizational performance 1 0 .1002/hrm.22159 b Min-Kyu Joo1 | Jeong-Yeon Lee 2 | Dejun Tony Kong 3 | Phillip M. Jolly4 y R M IT UNIVER

1Discipline of Organisational Studies, S ITY

University of Sydney Business School, Abstract L IB

University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia R

Research on women in leadership positions has largely focused on the board or top A R 2 Y

Department of Management, School of ,

management team (TMT) leadership level, showing that increased female representa- W i

Business, Seoul National University, Seoul, ley O South Korea

tion at these levels can benefit organizational performance. However, the strategic n line 3

Division of Organizational Leadership and L

implications of female representation at middle management have been largely ibra

Information Analytics, Leeds School of ry o

Business, University of Colorado, Boulder,

neglected. The current study addresses this issue in relation to High Performance n [05 Colorado, USA /

Work System (HPWS) improvement and organizational performance (profitability). 0 3 /2 4 0

Hospitality Management College of Health 2

By analyzing the multi-wave (2009, 2011, and 2013) Workplace Panel Survey (WPS) 3 ].

and Human Development, Pennsylvania State S ee t

University, University Park, Pennsylvania, USA

data collected from 1101 organizations in South Korea, we found a gender diversity h e Ter

advantage at middle management; that is, a higher level of gender diversity of middle m s Correspondence and

Min-Kyu Joo, Discipline of Organisational

management translated into a higher level of organizational performance due to C o n d

Studies, University of Sydney Business School, it

HPWS improvement. However, this advantage appeared only in the presence of a ion

University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia. s (htt

Email: minkyu.joo@sydney.edu.au

high level of subordinates' gender diversity. Our findings have important implications p s://on

for gender diversity and strategic human resource management. linelibrary.w K E Y W O R D S iley.

gender diversity, high performance work system, leadership, middle management, organizational com/t performance erms-and-conditions)

Companies in the top quartile for executive teams' gender diversity

executives (chairman, president, CEO, COO, etc.) are women (Eagly & o n W i

are 21% more likely to financially outperform their counterparts in the Carli, 2007) le

—it is not surprising that research has largely focused on y O n

bottom diversity quartile (Hunt et al., 2018). Post and Byron (2015)

the strategic implications of female representation at the top leader- line L

found that female board representation is positively related to

ship level (e.g., Leslie et al., 2017; Tinsley et al., 2016). ibrary

(a) organizational accounting-based performance in all countries and

Yet compared to what we know about organizational outcomes for rul

(b) organizational market performance in countries with greater gen-

and female representation in top leadership (board or TMT), our knowl- es of u

der parity (i.e., more equal access to resources and opportunities for

edge of female representation at middle management, and its implica- se; OA

women), presumably because female board representation benefits

tions for organizational performance, is rather limited. This gap is artic

monitoring and strategy involvement. Recent research has found that

glaring, given the importance of middle management to the develop- les are

when women join top management teams, organizations may shift

ment and implementation of organizational strategy. Middle managers, gover

from a buying to a building strategic approach (Post et al., 2022).

including but not limited to general line managers, functional line man- n ed by

These are but a few recent studies that have investigated the effects

agers, and team or project-based executives (Wooldridge et al., 2008), the a

of female executive leadership. Given that women are severely under- are p

“coordinator(s) between daily activities of the units and the strate- p licab

represented at the top of the corporate ladder l —only 6% of C-suite

gic activities of the hierarchy” (Floyd & Wooldridge, 1994, p. 48), and e Cre

are closer to daily operations but are often defined by their “lack (of) ative C

Jeong-Yeon Lee and Dejun Tony Kong are equal second authors.

the formal role authority held by their seniors to act strategically” o m m o n s L

Hum Resour Manage. 2022;1–21.

wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/hrm © 2022 Wiley Periodicals LLC. 1 icense 109 2 JOO 9 ET AL. 0 5 0 x , 0, Dow

(Rouleau & Balogun, 2011, p. 954). Indeed, Floyd and Wooldridge

expect a gender diversity advantage at middle management to be n load

(1997) noted that middle managers play crucial strategic roles when

strong in this collectivistic culture characterized by significant gender ed from

they “mediate, negotiate, and interpret connections between the orga-

inequality. In addition, the potential confounding effect of racial diver- https

nization's institutional (strategic) and technical (operational) levels”

sity would not be of great concern in our study using archival data ://onli

(p. 466). Moreover, middle managers also play key roles in developing

from South Korea, given the country's racial homogeneity, allowing us n elibr

and motivating employees (Kehoe & Han, 2020).

to focus more on gender effects. ary.wi

Therefore, middle managers can have a positive influence on

Our study makes several contributions to the gender diversity ley.com

the strategic operations and positioning of their organization

and strategic HRM literatures. First, the current study sheds critical /doi/

(e.g., improved decision making, strategy/system development, and

light on research on gender diversity. Previous research has focused 1 0 .100

implementation), thereby improving organizational performance

on how gender diversity at the top or bottom levels of the organiza- 2 /hrm

(Floyd & Wooldridge, 1992, 1994, 1997; Wooldridge & Floyd, 1990).

tion influences organizational performance (e.g., Carter et al., 2010; .22159

Though still underrepresented at middle management levels, women

Gonzalez & DeNisi, 2009). Although middle managers, who handle by RM

have made greater gains at this level than in the upper echelons of

the day-to-day operations of their organization, play central roles in IT U

organizations (Einarsdottir et al., 2018). Thus, it is important to shed

enhancing organizational performance, we have very little knowledge N IV E

greater light on the impacts that female representation at lower levels

about how and when gender diversity of middle management can R S ITY

of management may have on organizations. We introduce the term

enhance organizational performance. Our study provides some evi- L IB R

gender diversity advantage at middle management to indicate the

dence regarding the critical role that gender diversity of middle man- A R Y

potential enhancement of organizational performance from increased

agement plays in enhancing organizational performance via HPWS , W iley

gender diversity of middle management.1 Specifically, we argue that

implementation. Second, very little work has looked at the anteced- O n lin

increased gender diversity at middle management can enhance orga-

ents of HPWS systems or influences on their adoption and implemen- e Libr

nizational performance through strengthened HPWS implementation.

tation, and those that have focused largely on external or top-down ary on

However, simply increasing gender diversity of middle management is

drivers (Kim et al., 2021). Our work provides insights into the impor- [05/0

not beneficial for organizational performance; its advantage can be

tant ways in which the demographic characteristics of middle manage- 3 /2023

realized only when subordinates are gender diverse.

ment, namely gender diversity, can impact the possible development ]. See

In the current study, drawing from research suggesting that com-

and implementation of HR policies and practices that can contribute the Te

prehensive HR systems, known as high performance work systems

to an overall HPWS and organizational performance, contributing to rm s a

(HPWS), are positively associated with organizational performance

the gender diversity literature. Third, we attempt to clarify how and n d C o n

(Jiang et al., 2012), we argue that gender diversity of middle manage-

when gender diversity of middle management can be a competitive d ition

ment is indirectly and positively related to organizational performance

advantage for organizations and provide a new mechanism through s (http

via the improvement or development of HPWS. HPWS improvement

which a gender diversity advantage at middle management for HPWS s://onl

refers to the strengthening of existing HPWS through the implemen-

improvement and organizational performance is realized. Lastly, this inelibr

tation of additional high-value HR practices, which results in positive

study contributes significantly to the understanding of context in stra- ary.w

changes in the functions of HPWS and subsequent improvement in

tegic HRM research (i.e., South Korea) by exploring this phenomenon iley.co

organizational capabilities essential for performance in dynamic envi-

using a large sample of South Korean panel data and identifying a con- m /term

ronments (Jiang et al., 2012; Roberson et al., 2017).

textual factor (subordinate gender diversity) that may serve as a s-and

Specifically, we argue that an increased female representation at

boundary condition of a gender diversity advantage at middle -condi

middle management can facilitate the generation of information and management. tions)

knowledge around employee needs and desires, leading to more dif- o n W i

ferentiated solutions (Wiersema & Bantel, 1992). Given middle man- ley On

agers' important role in managing strategic and operational activities, 1 |

T H E O R E T I C A L F O U N D A T I O N S A N D line L

gender diversity of middle management has the potential to facilitate H Y P O T H E S E S ibrary

organizational performance indirectly through HPWS improvement, for rul

contingent upon nonmanagerial employees' gender diversity. HPWS 1.1 |

Strategic role of middle management es of u

is a comprehensive HR system intended to enhance organizational se; OA

performance and is arguably among the most effective means that

Strategy is often considered to be solely the domain of top manage- artic

middle managers can use to achieve strategic and operational goals.

ment. However, from the perspective of strategy as processual les are

By considering (a) HPWS improvement as an intermediary mechanism

(Whittington, 1993), stakeholders outside senior management, such gover

and (b) nonmanagerial employees' gender diversity as a boundary con-

as those in middle management, play a critical role in realizing strate- n ed by

dition, we help delineate how gender diversity of middle management

gic change because “strategy is a mix of deliberate intent and emer- the a

can indirectly enhance organizational performance. We term this key

gent actions and decisions, as a result of which formulation and p p licab

benefit a “gender diversity advantage at middle management.”

implementation of strategy are intertwined rather than being separate le Cre

We integrate research on gender diversity and strategic human

processes” (Currie & Procter, 2001, p. 55). Therefore, middle man- ative C

resources (HR) for our theorizing in the country of South Korea. We

agers are “not just passive recipients, but also active interpreters, o m m o n s License 109 JOO 9 ET AL. 3 0 5 0 x , 0, Dow

mediators, and intermediaries in implementing and reforming strategy

managers' impact on HR strategy is a function of their ability to influ- n load and policy e

” (Xie et al., 2013, p. 3481). In other words, middle managers

ence decision makers and exchange information with them in a pro- d from

are involved in organizing, directing, synthesizing, and controlling imple-

ductive way (Raes et al., 2011), middle managers must be able to https

mentation of strategic plans and thus have a substantial influence on

persuasively present and advocate for recommendations based on ://onli

strategic development processes (Floyd & Wooldridge, 2000; Huy,

collected information. Given the extant evidence that female middle n elibr

2001; Kehoe & Han, 2020; Rouleau & Balogun, 2011; Wooldridge

managers are more likely to engage in participative/democratic lead- ary.wi et al., 2008).

ership and collaborative negotiation, we propose that the presence of ley.com

We focus specifically on the key linking role that middle managers

higher gender diversity of middle management is likely to lead to /doi/

may play in connecting HR strategies and employees (Currie & greater improvement in HPWS. 1 0 .100

Procter, 2001). HR strategies are considered to be “third order' strate- 2 /hrm gies .2 …flowing

from, but also upwardly influencing…wider corporate 2 1 5 9

strategies” (Purcell, 2000, p. 62). Middle managers can play a signifi- 1.2 |

Gender diversity of middle management and by RM

cant role in HR strategy (Kehoe & Han, 2020), not only in terms of HPWS improvement IT U

downward implementation, but also through active identification of N IV E

beneficial practices and policies and the promotion of these policies

In order to effectively champion new ideas and alternatives regarding R S ITY

to organizational decision makers. In identifying, implementing (on a

HPWS, middle managers should pay attention to the needs of internal L IB R

local level), and providing resources to test emergent ideas, middle

human capital and provide suggestions for systems that will appropri- A R Y

managers engage in championing new ideas and alternatives, which is

ately address these needs. Middle managers should also be proficient , W iley

one of the primary pathways for middle managers' strategic involve-

at selling HPWS-related issues to top executives to obtain buy-in and O n lin

ment (Floyd & Wooldridge, 1992).

necessary financial resources (Dutton et al., 1997; Dutton & e Libr

The main purpose of championing new ideas and alternatives is

Ashford, 1993). Finally, they also must have an ability to encourage ary on

to adjust and improve the current content of strategy to benefit orga-

suggestions from employees and a strong willingness to implement [05/0

nizational functioning (Floyd & Lane, 2000; Mantere, 2005, 2008).

HPWS, helping their organization meet its employees' needs. In light 3 /2023

From an HR perspective, middle managers can serve as organizational

of these assertions, we identify a gender diversity advantage at middle ]. See

champions, persistently and persuasively advocating for entrepreneur-

management in that such diversity contributes to HPWS improve- the Te

ial or innovative options, initiatives, and strategies to senior manage-

ment; this is because of women's participative/democratic leadership rm s a

ment and HR management. They are implementers of organizational

in the process of gathering feedback and suggestions from subordi- n d C o n

strategy and observers of its effectiveness (Raes et al., 2011), and “act

nates and their collaborative negotiation in the process of solving d ition

as an initial screen” (Floyd & Wooldridge, 1994, p. 50) of HPWS

problems with senior managers and HR managers. Said differently, s (http

implementation in day-to-day operations as well as subordinates'

gender-diverse middle management (i.e., an increased proportion of s://onl

reactions to HPWS. If HPWS implementation is ineffective or subordi-

female middle managers) should lead subordinates to speak up about inelibr

nates have adverse reactions to HPWS, middle managers can select

issues (Eagly & Johnson, 1990) and should also possess a greater abil- ary.w

from a wide range of business opportunities, novel procedural pro-

ity to integrate diverse sets of information in ways that might lead to iley.co

posals, and administrative changes suggested at operating levels

innovative HR policy and practice solutions and then advocate for m /term

(Floyd & Wooldridge, 1994) and provide this information to strategic

those solutions (Eagly et al., 2003; Eagly & Johnson, 1990). Our argu- s-and

decision makers (Raes et al., 2011). Because middle managers “(live) in

ments to this effect are similar to those arguing for the benefits of -condi

the organizational space between strategy and operations,” they “are

gender diversity in new venture teams in the entrepreneurship litera- tions)

uniquely qualified to make such judgments” (Floyd & Wooldridge, 1994, ture (see Dai et al., 2019). o n W i

p. 50) and decide to which issues senior managers and HR managers

First, well-documented differences in information processing ley On

should pay attention (Wooldridge et al., 2008).

between males and females should lead to greater collection and integra- line L

As alluded to above, middle managers play two primary strategic

tion of suggestions from subordinates by middle management that is ibrary

roles: (1) collection of information regarding both the effectiveness of

more gender diverse. Women are likely to pay more attention to subtle for rul

the implemented strategy and potential suggestions and alternatives

information (Darley & Smith, 1995), are less likely to adopt problem- es of u

to existing strategy; and (2) identification, evaluation, and presentation

solving strategies that conform to existing beliefs or heuristics (Chung & se; OA

of new ideas and alternatives. Accordingly, we argue that two mana-

Monroe, 1998), retain more detailed information (Seidlitz & Ed, 1998), artic

gerial capabilities should be particularly important for successful

and have better recall after encountering new information (Erngrund les are

middle managers' effectiveness of influencing strategic HR decisions.

et al., 1996) than men. All of these findings support women's tendency gover

First, creating an environment where information regarding employee

to manage subordinates in a more participatory and democratic manner, n ed by

needs flows freely up to middle managers from subordinates is instru-

which promotes employee voice and input (Book, 2000; Greene the a

mental to information gathering (Kehoe & Han, 2020), because such

et al., 2003), thus providing the information necessary to understand the p p licab

an environment will make subordinates more willing to provide

needs of employees with respect to HR policies and practices. le Cre

insights and ideas on what employees believe would be valuable

Second, women tend to engage in greater levels of relational ative C

from an HR practice perspective. Second, considering that middle

information processing than men, meaning that they focus more on o m m o n s License 109 4 JOO 9 ET AL. 0 5 0 x , 0, Dow

the relationships between sets of individual pieces of information

which includes various measures such as pay, childcare costs, and per- n load

(Chung & Monroe, 1998), such as diverse suggestions from multiple

centage of senior positions (Economist, 2018). In South Korea, female ed from

subordinates as to HR policy preferences and needs. Such information

employees' contributions to their organization have been less valued or https

processing increases the likelihood that gender-diverse middle manage-

appreciated than those of their male counterparts, which results in gen- ://onli

ment will be able to craft innovative and norm-challenging HR policies

der inequality in promotion to top management (Cooper-Jackson, 2001) n elibr

and practices. However, this is only the first step to HPWS improve-

and a lack of women in upper management positions (Easton, 2015). ary.wi

ment. Middle managers must also persuade their senior management

Several critical factors constitute barriers to women's career advance- ley.com

to adopt new HR practices in order to accommodate the needs of

ment in South Korea, such as Confucianism, traditional norms, and gen- /doi/

employees (Ashford & Detert, 2015; Mirabeau & Maguire, 2014). Nota-

der stereotypes and roles (e.g., about married women with children) 1 0 .100

bly, despite its potential benefits at the operational level, improving

(Ibarra et al., 2013). Because women are burdened by both work and 2 /hrm

HPWS is not cost free to organizations, and therefore, finding a solu-

family demands and responsibilities, they feel the need to put extra .22159

tion that benefits all parties is important for the success of such negoti-

effort toward standing out in the workplace via their work performance by RM

ation (cf. Raes et al., 2011); it requires collaboration and problem

(Kim et al., 2020) while resolving the conflict between the roles of IT U

solving among all negotiation parties (Kong et al., 2014; Walton &

breadwinners and homemakers/caregivers (Cho et al., 2019). In addi- N IV E McKersie, 1965).

tion, many women in South Korea have limited networking and leader- R S ITY

Middle management's gender diversity can facilitate exploration

ship development opportunities, which make them struggle in rising to L IB R

of creative ideas and collaboration with senior managers and HR man-

management positions (Cho et al., 2017; Rowley et al., 2016). A R Y

agers, as women have been found to focus more on problem solving,

We focus on HPWS as an important mediator between gender , W iley

conflict resolution, and finding a mutually beneficial solution during

diversity of middle management and organizational performance in O n lin

negotiation (Brahnam et al., 2005; Henderson et al., 2013; Walters

South Korea because Bae and Lawler (2000) pointed out four reasons e Libr

et al., 1998). Taken together, these findings support the argument that

why HPWS could be important to implement in a collectivistic coun- ary on

gender-diverse middle management can help senior managers and HR

try such as South Korea. First of all, South Korea's collectivism facili- [05/0

managers formulate better HPWS strategy by directing attention

tates cooperation, loyalty, and harmony, which are aligned well with 3 /2023

toward strategic issues in regard to HPWS improvement and advocat-

HPWS (Lee & Johnson, 1998). Second, recent Korean culture can be ]. See

ing for resources for HPWS improvement. Hence, gender diversity of

characterized as a composite of Asian and Western values. That is, the Te

middle management can be a crucial driver of successful HPWS

Korean organizational culture shows that individualism and group har- rm s a

improvement (Gilbert et al., 2015).

mony are both equally strong. After the financial crisis in 1997, many n d C o n

In sum, since more gender-diverse middle management tends to

organizations operated their organizations with dynamic collectivism, d ition

focus on development, learning, individual/communal goals, and

reflecting multidimensional and paradoxical subcomponents: in-group s (http

voices (Paustian-Underdahl et al., 2014), with lateral and upward sup-

harmony, optimistic progressivism, and the hierarchical principle s://onl

port, they likely better serve as champions who gather information

(Cho & Yoon, 2001). Dynamic collectivism is defined as a mixture of inelibr

from subordinates about what issues require new ideas and alterna-

harmony and change, face-saving and aggressiveness, and emotional ary.w

tives that help improve the existing HPWS, and negotiate collabora-

community and impersonal achievement (Cho et al., 2014). iley.co

tively with senior managers and HR managers, thereby facilitating

The third reason is globalization (Bae et al., 2007). In order to m /term

HPWS improvement. In addition, HPWS can provide a context where

achieve better performance under globalization, organizations should s-and

female middle managers find a good fit with their cooperative man-

be more flexible to adapt to uncertainty in their environment. After -condi

agement style and soft skills (Kato & Kodama, 2017). Therefore, we

the 1997 financial crisis, the Korean Chaebols ti —large conglomerates— o n s)

predict a gender diversity advantage at middle management, such that

westernized their HRM systems (e.g., from seniority- to performance- o n W i

as more women are represented there, the greater HPWS improve-

based compensation) and increased employment flexibility (e.g., from ley On

ment will be. As such, we propose the following hypothesis:

high job security to more part-time or contingent job positions). Chae- line L

bols started emphasizing teamwork, employee empowerment, voice, ibrary

Hypothesis H1. Gender diversity of middle management

and merit-based hiring, incorporating many characteristics of HPWS for rul

in an organization is positively related to the level of HPWS

(Bae et al., 2007). Many South Korean organizations emphasize inno- es of u improvement.

vation, market culture, and risk-taking and implement HPWS (Rhee se; OA

et al., 2016). Relative to Western culture, collectivistic organizations artic

are more likely to encourage people to collaborate to better coordi- les are 1.3 |

Gender, management positions, and HPWS

nate and integrate organizations' skills and resources (Lee & gove in South Korea r

Miller, 1999). Knowledge exploitation and exploration through knowl- n ed by

edge transfer within the organization can be accomplished by such the a

Gender differences may play more critical roles in implementing HR

collaboration, which is aligned well with the core function of HPWS p p licab

practices in male-dominant cultures (Ciancetta & Roch, 2021; Hofstede (Miller & Shamsie, 1996). le Cre

et al., 2010; Williams & O'Reilly, 1998). South Korea is a relatively

Finally, because HPWS involves continuous training, it fits well ative C

unfriendly place for working women in terms of the glass-ceiling index,

with the fact that South Korean people value education and o m m o n s License 109 JOO 9 ET AL. 5 0 5 0 x , 0, Dow

development as a means to be competitive (Bae & Lawler, 2000). The

because they are more likely to have and accept unequal power distri- n load

above reasons explain the transformation of South Korean cultures,

butions within social institutions and for organizational representatives ed from

leading to more acceptance and willingness to work under HPWS

to invoke legitimate authority (Hofstede, 1984). Managers can flaunt https

(e.g., selective staffing, comprehensive training, outcome-based com-

authority more and enjoy greater hierarchical inequality in the higher ://onli

pensation, employee empowerment, participation in a decision making

power distance context, which thereby enhances the possibility that n elibr

process, etc.), and pointing to the need to understand the increasing

managers' strategic choices concerning low levels of HPWS will be ary.wi

role of HPWS in South Korean organizations. accepted. ley.com

Set against this context, we argue that the effect of gender diver- /doi/

sity of middle management on HPWS improvement is bounded by 1 0 .100 1.4 |

Subordinate gender diversity as a critical

gender diversity of subordinates for two reasons. First, while gender- 2 /hrm contingency

diverse middle management tends to have more engaging leadership .22159

and collaborative negotiation skills than gender-homogenous middle by RM

As previously discussed, national culture plays important role in imple-

management, the former faces challenges due to gender role incon- IT U

menting HR practices and perceiving leadership (Schuler, 2013;

gruity (i.e., a mismatch between their gender and middle manager role) N IV E

Stoeberl et al., 1998). We also argue that the national context of our

in South Korea. Whether female middle managers can effectively play R S ITY

data collection (South Korea) may influence the degree to which inter-

the champion role that facilitates HPWS improvement depends on L IB R

nal context (subordinate gender diversity) can shape the relationship

the internal environment; one important aspect of the internal envi- A R Y

between gender diversity of middle management and HPWS improve-

ronment is organizational demography. We argue that gender diver- , W iley

ment. Employees who are in individualistic countries may have an

sity of subordinates is a demography-related boundary condition. O n lin

independent view, while employees who are in collectivistic countries

South Korea ranked dead last in terms of gender egalitarianism in e Libr

such as South Korea, Japan, and China emphasize an interdependent

House et al.'s (2004) study; the culture values a masculine leadership ary on

view stressing connectedness and relationships (e.g., Guanxi; Chen

style, and thus, female middle managers in South Korea likely face [05/0

et al., 2013) as well as high vertical collectivism 3 / —high collectivism and

prejudice and discrimination from their male subordinates (cf. Eagly & 2 0 2 3

high power distance (Singelis et al., 1995). For example, organizations in

Carli, 2007; Eagly & Karau, 2002). ]. See

Japan still maintained traditional East Asian HR system (e.g., seniority-

For example, female middle managers, who are not common in the Te

based compensation and promotion, long-term employment; Bae

South Korea, may be viewed by male subordinates as less competent rm s a

et al., 2010). Traditional HR management in East Asian countries relied

or effective and thus be less accepted by male subordinates. In a n d C o n

more on informal personal relationships and people's judgment than on

male-dominant internal environment, female middle managers may be d ition

official and objective criteria and regulations (Lam et al., 2002; Xian

compelled to adjust their leadership behaviors to more dominant and s (http

et al., 2019). Confucian values and the Chinese family business model

assertive ones to match their male subordinates' preferences for mas- s://onl

based on traditional authority are pervasive in South Korea as well

culine leadership styles. By doing so, gender-diverse middle manage- inelibr (Claessens et al., 2000).

ment loses its advantage in participative/democratic leadership and ary.w

Traditional South Korean HR management has prevented

collaborative negotiation. As a result, the benefit of gender diversity iley.co

employees from becoming involved in decision making processes as

of middle management for HPWS improvement is less likely to hap- m /term

information was passed down from senior management (Deyo, 1989;

pen. By contrast, in an internal environment characterized by a higher s-and

Frenkel & Lee, 2010) and emphasized employee loyalty and long

level of subordinate gender diversity, female middle managers are not -condi

working hours. In these contexts, individuals perceived typical male

as threatened by negative gender stereotypes or role incongruity tions)

leadership styles as more appropriate than female leadership

(Paustian-Underdahl et al., 2014). Therefore, gender diversity of mid- o n W i

(Triandis, 1995); a majority of organizations did not have any women

dle management can translate into more widespread participative/ ley On

on their board in those counties (Low et al., 2015; The Japan

democratic leadership and collaborative negotiation, facilitating a fer- line L

Times, 2021; The Korea Herald, 2020). Despite high levels of technol-

tile environment for HPWS improvement. ibrary

ogy and economic development, traditional social and cultural norms

Second, the new ideas and alternatives that gender-diverse mid- for rul

are still alive, influencing beliefs about gender roles in those countries

dle management champions for HPWS improvement can come from es of u (Brooks, 2006).

subordinates. Female and male subordinates have different life and se; OA

While employees in countries where individualism is highly valued

work experiences. Due to such differences, they likely have different artic

seek opportunities and incentives for themselves, collectivism would

views on how the existing HPWS is working and how it should work. les are

lead employees to reorient their goals toward collective benefits.

Gender diversity, despite its potential for engendering conflict, can be gover

According to Schuler (2013), in countries where collectivism is strong,

a pivotal source of novel and useful ideas (Egan, 2005; Jackson n ed by

such as East Asian countries, HR practices that facilitate information

et al., 2003). Stated differently, gender diversity is a source of creative the a

sharing may be less prevalent. High power distance also prevents the

ideas and alternatives in that male and female employees have a p p licab

drive to seek personal benefits and would be well aligned with auto-

greater range of viewpoints and lived experiences (Mateos de Cabo le Cre

cratic leadership (Dorfman et al., 2012). In high power distance cultures,

et al., 2012) from which to draw to create suggestions for changes ative C

employees may agree with the strategic choices of management

and/or improvements in HR policies and practices. With these ideas o m m o n s License 109 6 JOO 9 ET AL. 0 5 0 x , 0, Dow

and alternatives, gender-diverse middle management is in a better

and comprehensive training opportunities are intended to help n load

position to collect information used to understand the issues and

employees acquire and develop their work-related knowledge, skills, ed from

potential solutions based on HPWS improvement.

and competencies. Practices such as developmental feedback, competi- https

Taken together, the above arguments lead us to hypothesize that

tive compensation, performance-based incentives, high-quality bene- ://onli

gender diversity of subordinates strengthens the link between gender

fits, clear promotion and career development opportunities, and job n elibr

diversity of middle management and the level of HPWS improvement.

security are designed to enhance employees' work motivation. Finally, ary.wi

practices such as team-based work, employee involvement systems, ley.com

Hypothesis H2. Subordinate gender diversity modifies

flexible job designs, and pathways for information sharing provide /doi/1

the relationship between gender diversity of middle man-

employees with the opportunity to use skills and motivation in ways 0 .100

agement in an organization and the level of HPWS

that achieve organizational objectives (Boon et al., 2019). 2 /hrm

improvement, such that this relationship is stronger when

As HPWS is improved, employees will have stronger ability, .22159

subordinate gender diversity is higher.

stronger motivation, and more opportunities to use their ability and by RM

motivation for their work (Huselid, 1995; Ramsay et al., 2000). Thus, IT U

employees can more efficaciously participate in collaborative decision N IV E 1.5 |

HPWS improvement and organizational

making processes and work with others in delivering high-quality R S ITY performance

output, thereby increasing their work efficiency (Boon et al., 2019) L IB R

and ultimately facilitating organizational performance. A R Y

HPWS, as a unique, inimitable, causally ambiguous, and synergetic , W iley

mechanism, can deliver organizations a sustainable competitive

Hypothesis H3. The level of HPWS improvement is posi- O n lin

advantage (Lado & Wilson, 1994). Wright et al. (1994) argued that

tively related to the level of organizational performance. e Libr

individual HR practices are not a competitive advantage as HR ary on

practices can easily be copied by competitors. However, it is difficult

Autonomous strategic behaviors are defined as activities that [05/0

to imitate bundles of HR practices due to the interdependence of

create substantial internal variations by diverging from or substituting 3 /2023

multiple practices and their synergistic effect (Lado & Wilson, 1994).

for existing strategic plans (Burgelman, 1991; Mirabeau et al., 2018). ]. See

Characteristics of HPWS bundles, such as unique historical paths, can

For reasons explained above, we argue that gender diversity of the Te

make them difficult for competitors to copy (Becker & Huselid, 2006).

middle management may create significant content-based variance rm s a

Indeed, Saridakis et al. (2017) found that HPWS, as a bundle of multi-

(i.e., implemented HR practices) between organizations by actively n d C o n

ple HR practices, facilitated organizational performance to a greater

facilitating autonomous strategic behaviors such as championing new d ition

extent than individual HR practices, and this effect appeared for both

ideas and initiatives related to programs and practices that constitute s (http

financial performance (e.g., accounting returns) and operational

HPWS (Noda & Bower, 1996). As a result, gender diversity of middle s://onl

performance (e.g., workforce productivity). The positive implication of

management represents a potential source of heterogeneity among inelibr

HPWS for organizational performance has been demonstrated using

organizations, which is the primary driver of “organizations' ability to ary.w

various indicators of organizational performance (e.g., Huselid, 1995;

derive rents from complex HR systems such as HPWS i ” (Chadwick & ley.co

Jiang et al., 2012; Messersmith et al., 2011; Saridakis et al., 2017) in

Flinchbaugh, 2021, p. 35), and thus creates a gender diversity advan- m /term

various countries, such as China, Japan, South Korea, Spain, Canada,

tage at middle management. HPWS is arguably among the most effec- s-and

the U.K., and the U.S. (Choi, 2014; Huselid, 1995; Prieto &

tive means for middle managers' achievement of strategic goals, as -condi

Santana, 2012; Rabl et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2007; Takeuchi

HPWS fosters human capital and employee motivation, which are two tions) et al., 2007).

important drivers of organizational performance (Jiang et al., 2012; o n W i

Following previous research (e.g., Jiang et al., 2012; Lepak

Messersmith et al., 2011) (see Figure 1 for our conceptual model). ley On

et al., 2006), we argue that HPWS has ability-, motivation-, and line L

opportunity-enhancing (i.e., AMO-enhancing) functions, satisfying

Hypothesis H4. The level of HPWS improvement medi- ibrary

employees' psychological needs for competence, relatedness, and

ates the interactive effect of gender diversity of middle for rul

autonomy (Ryan & Deci, 2000), and thus can help improve organiza-

management and subordinate gender diversity in an orga- es of u

tional performance. HPWS refers to “organizational actions or pro-

nization on the level of organizational performance. se; OA

cesses and job characteristics that focus on attracting, developing, artic

and motivating employees and providing opportunities to contribute” les are

(Boon et al., 2019, p. 2518). Lepak et al. (2006) conceptualized gover

systems of HR practices as falling into three distinct dimensions n —skill-, 2 | M E T H O D ed by

motivation-, and opportunity-enhancing HR practices. Stated the a

differently, HPWS provides three components to foster employee 2.1 | Sample p p licab

performance: ability, motivation, and opportunity (Jiang et al., 2012; le Cre

Lepak et al., 2006; Messersmith et al., 2011). Practices such as stan-

To test our hypotheses, we used the Workplace Panel Survey (WPS) ative C

dardized and well-developed recruitment practices, rigorous selection,

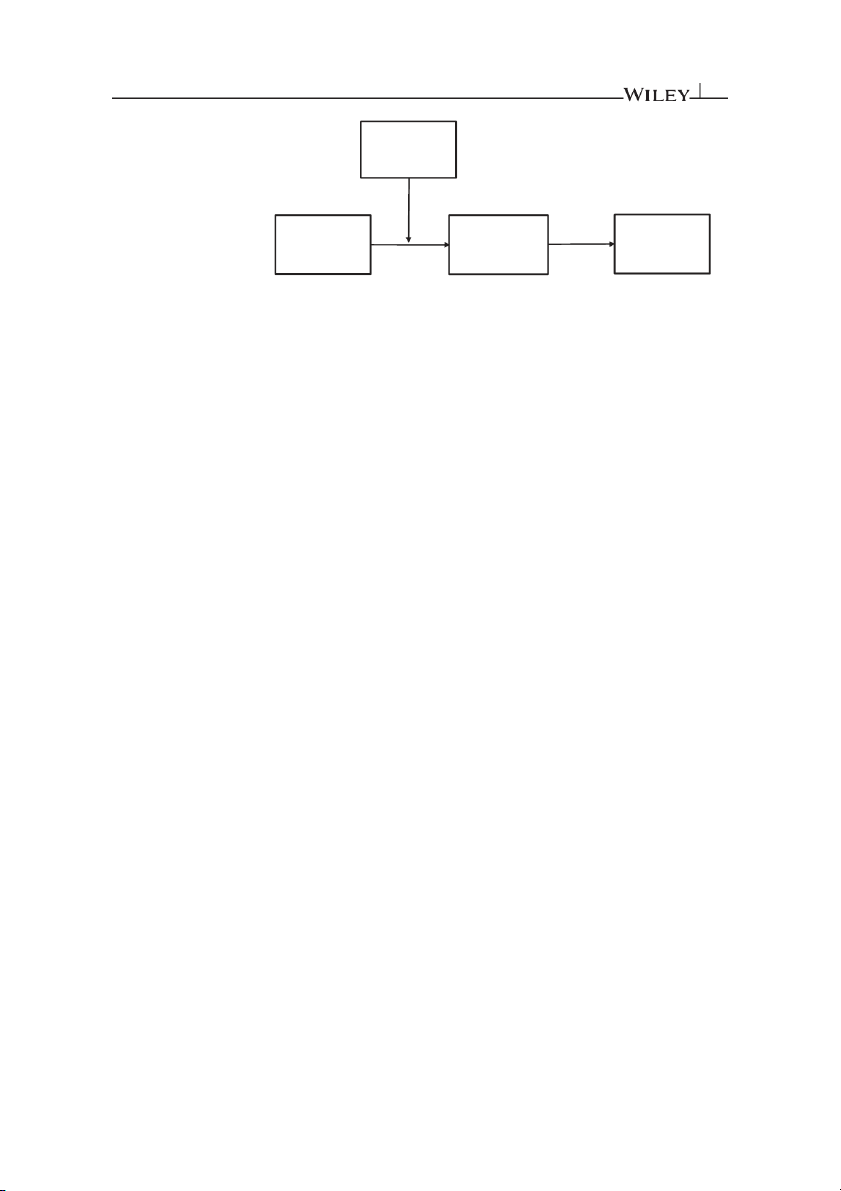

data2 collected in 2009, 2011, and 2013. This survey was conducted o m m o n s License 109 JOO 9 ET AL. 7 0 5 0 x , 0, Dow F I G U R E 1 Conceptual model n loa Gender Diversity d ed of Subordinates from (T1) h ttps://onlinelibrary.wile Gender Diversity High Performance y .c Organizational o m of Middle Work System /d Performance o i Management Improvement /10 (T3) .1 (T1) (T2-T1) 0 0 2 /hrm.22159 by RM

by the Korea Labor Institute, a government-funded policy research

(1977). We calculated this index by subtracting the sum of the respec- IT U

body, in tandem with the South Korean Ministry of Labor. Approxi-

tive squared proportions of male and female employees from 1; the N IV E

mately 1700 firms with 30 or more employees across the country

score ranged from 0 (most homogeneous) to 0.5 (most diverse) R S ITY

were randomly selected using stratified sampling and surveyed.

(Gonzalez & Denisi, 2009; Richard et al., 2004). L IB R

Organization-level data in 2009 and 2011 were available for 1737 A R Y

and 1770 organizations, respectively, while organization-level data in , X , W iley

2013 were available for 1621 organizations. B:I: ¼ 1 Pi2 O n lin

Individual interviews (Blaise system-based Computer-Assisted e Libr

Personal Interviewing) were conducted to obtain information related

where, P = the proportion of subordinates in the organization (male ary on

to human resources and labor relations. Mail and web surveys were

or female); i = the number of different categories represented in the [05/0

conducted to obtain data on employment status and financial status. organization (=2). 3 /2023

Organizations in the forestry, mining, fishing, and agriculture sectors,

HPWS improvement. We included HR practices to measure ]. See

as well as public service organizations, were excluded from the sam-

HPWS in the current study, which are highly overlapped with those in the Te

pling frame. The organization-level survey was completed by the HR

previous studies. According to the recent comprehensive review con- rm s a

manager and a labor union representative of each organization. The

ducted by Boon et al. (2019), HR practices most commonly used to n d C o n

data of the endogeneity control variables were collected in 2007

build HPWS are categorized into the following: training, participation/ d ition

(Time 0), those of the predictor and control variables in 2009 (Time 1);

autonomy, incentives, performance appraisal, recruiting, and selection, s (http

those of the mediator (i.e., HPWS improvement) in 2011 (Time 2), and

which are typically identified as core HR practices for HPWS s://onl

those of organizational performance (profitability) in 2013 (Time 3).

(Posthuma et al., 2013). We selected five of these six HR practice cat- inelibr

We matched the organization-level panel data across the 3 years

egories for our HPWS construct (Boon et al., 2019; Lepak ary.w

using unique identification numbers. The resulting final sample com-

et al., 2006). This HPWS composition was also similarly used across iley.co

prised 1101 organizations that provided suitable and usable data for

countries (e.g., the United States, China, Spain, the United Kingdom, m /term

analysis. After we matched identified numbers in each year, we used

Canada, and South Korea) (Rabl et al., 2014). s-and

1066 organizations to test Hypotheses H1 and H2. 621 organizations

Specifically, to create an index of HPWS in each organization, we -condi

were used to test Hypotheses H3 and H4. The response rates for

used twelve HR practices that encompass the types of practices iden- tions)

original samples were 70.3% (2009), 62.4% (2011), and 54.9% (2013),

tified by prior studies (cf., Huselid, 1995; Jiang et al., 2012): training, o n W i respectively.

recruiting, a regular and formal performance appraisal system, annual ley On

salary, profit sharing, incentives, employee suggestion program, small line L

group activities, regular team meetings, job rotation, multi-functional ibrary 2.2 |

Measures of key variables

training, and autonomy. For all practices except autonomy, HR man- for rul

agers responded to items (1 = yes, 0 = no), indicating whether or not es of u

Gender diversity of middle management (proportion of female middle

their respective organizations had implemented the respective HR se; OA

managers) (Time 1). Female middle managers included female team- practices. artic

or project-based executives, deputy general managers, and depart-

For autonomy, HR managers indicated the levels of autonomy in les are

ment managers. We aggregated them to derive the total number of

their organizations with respect to task, speed, recruiting, and training, gover

female middle managers in an organization. Then, we calculated gen-

ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A sample item n ed by

der diversity of middle management in each organization by dividing

was “the extent to which a major operating unit (e.g., team) of your the a

the total number of female middle managers by the total number of

workplace has autonomy regarding how to work at the unit. p ” We p licab middle managers (Kalev, 2009).

transformed these four scales into dummy codes (1 l –2 = 0, 3–4 = 1) e Cre

Gender diversity of subordinates (Time 1). Subordinates'gender

and then aggregated all of them to create an autonomy index. We ative C

diversity in each organization was indicated by the Blau's index

again transformed this value into dummy codes (0 o –2 = 0, 3–4 = 1), m m o n s License 109 8 JOO 9 ET AL. 0 5 0 x , 0, Dow

with 1 representing the effective implementation of autonomy prac-

organization were held by foreigners, using a percentage ranging from n load

tices and 0 representing the ineffective implementation or lack of 0% (no foreign stake) to 100%. ed from autonomy practices.

Proportion of female executives. As noted earlier, the proportion https

Ten items were summed to measure training. These items were

of female strategic leaders was found to predict organizational perfor- ://onli

corporate education, external group training, internet-based education

mance (Post & Byron, 2015). Therefore, we controlled for the propor- n elibr

and training, support for meetings to learn work-related skills,

tion of female executives in each organization, calculated by dividing ary.wi

employee training on the technical guidance, technical guidance, and

the number of female executives by the total number of executives. ley.com

employee training from the parent company/trust companies, paid or

In order to address the concern about firm-specific unobservable /doi/

unpaid day release training, tuition support for training institutions

characteristics, we included a variable related to management salary 1 0 .100

(including school), financial aid/loans for educational institutions, and

and a locality variable as the proxy of corporate culture in the models. 2 /hrm

participation in employee training programs during working hours.

Regarding management salary, we included the total salary of a middle .22159

Two items were used to measure recruiting: multi-media (e.g.,

manager before tax (first-year salary). Organizations in Seoul are more by RM

newspaper, radio, and television) recruiting and internet-based recruiting

likely to recruit and retain female employees (i.e., higher levels of gen- IT U

(1 = yes, 0 = no). We used four items to measure what types of incen-

der equality for all positions, including top management) and have N IV E

tives were in place (1) group performance-based incentive, (2) company

progressive and innovative corporate culture than organizations else- R S ITY

performance-based incentive, (3) business unit performance-based incen-

where in South Korea. It is plausible that organizations in Seoul have a L IB R

tive, and (4) department or team performance-based incentive

more progressive corporate culture, and therefore, organizations in A R Y (1 = yes, 0 = no).

Seoul are more likely to implement HPWS (Bae & Lawler, 2000) and , W iley

We summed each item to create indices of training (10 items),

promote gender diversity to a greater extent than organizations else- O n lin

recruiting (2 items), and incentives (4 items). It is appropriate to sum

where. Corporate cultures that emphasize gender equality or devalue e Libr

all indicators of HR practices because these practices' synergistic

discrimination toward women should be more conducive to overall ary on

effects on organizational performance are claimed to be realized from

gender diversity and female employees' career advancement, helping [05/0 their complementarity in bundles (Becker & Gerhart, 1996;

more female employees be promoted to management positions. For 3 /2023

MacDuffie, 1995). To obtain the improvement of HPWS from Time

example, most Chaebols where their culture is progressive and inno- ]. See

1 to Time 2, we aggregated all the practices and then subtracted

vative are in Seoul (dummy coded, 1 = Seoul, 0 = other areas). Our the Te

HPWS at Time 1 from HPWS at Time 2 (i.e., formative measure).

correlation table supports our arguments that locality could be a proxy rm s a

Organizational performance (Time 3). We focused on organiza-

for corporate culture. Being an organization in Seoul is positively cor- n d C o n

tional profitability. Following prior research, we divided the logarithm

related with gender diversity of middle management (r = 0.11, d ition

of net profit for 2013 (fiscal year) by the organizational size in 2013

p < 0.01), HPWS level at Time 2 (r = 0.07, p < 0.05), and gender diver- s (http

(indicated by the logarithm of the total number of full-time

sity of subordinates (r = 0.10, p < 0.01) as stated. s://onl employees; Shaw et al., 2013). inelibrary.w 2.4 | Endogeneity control iley.co 2.3 |

Measures of control variables m /term

We addressed the endogeneity of the relationship between gender s-and

We controlled for several variables theoretically predictive of organi-

diversity of middle management (i.e., the proportion of female middle -condi

zational performance. The data of these control variables were avail-

managers) and HPWS improvement by providing the fixed effect esti- tions)

able from the organization-level survey described above.

mates on the effect of gender diversity of middle management on o n W i

Industry differences. Industries affect organizational performance

HPWS improvement. We controlled for the possibility that gender ley On

(Datta et al., 2005). To account for the industry differences, we used

diversity of middle management is more likely to be related to HPWS line L

industry dummy variables created based on WPS-provided industry

improvement. Following prior research (Tang et al., 2018), we first ibrary codes.

regressed gender diversity of middle management at time t against a for rul

Organizational size. The larger an organization, the more effica-

set of antecedent variables measured 2 years prior, that is, year t 2. es of u

cious HR practices it may have (Arthur, 1994). Thus, an organization's

These instrumental variables included HR strategy s —whether the pri- e; OA

size could predict its performance. We operationalized the organiza-

mary goal of HR is to maximize savings on fixed labor costs and artic

tional size as the logarithm of the number of full-time employees.

whether HRM is based on individual performance (a five-point Likert les are

Organizational age. More established organizations tend to be

scale from 1 to 5). In order to account for the possibility that prior gover

less vulnerable to performance pressure (Hannan & Freeman, 1984).

birthrate in each organization's location might drive a higher level of n ed by

Thus, we controlled for the age of an organization, which was calcu-

gender diversity of middle management in the areas in which each the a

lated as the difference between 2009 and the founding year.

organization operates, we included birthrate ratio (the ratio of boys p p licab

Foreign stake. An organization's foreign stake can predict its per-

per one hundred girls) measured in 1990 (this year is the earliest one le Cre

formance (Douma et al., 2006). To measure an organization's foreign

we could obtain) by using the Korean government database (https:// ative C

stake, its HR managers indicated the extent to which the shares of the

kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/index.action).3 In addition, we included other o m m o n s License 109 JOO 9 ET AL. 9 0 5 0 x , 0, Do TA B L E 1 w

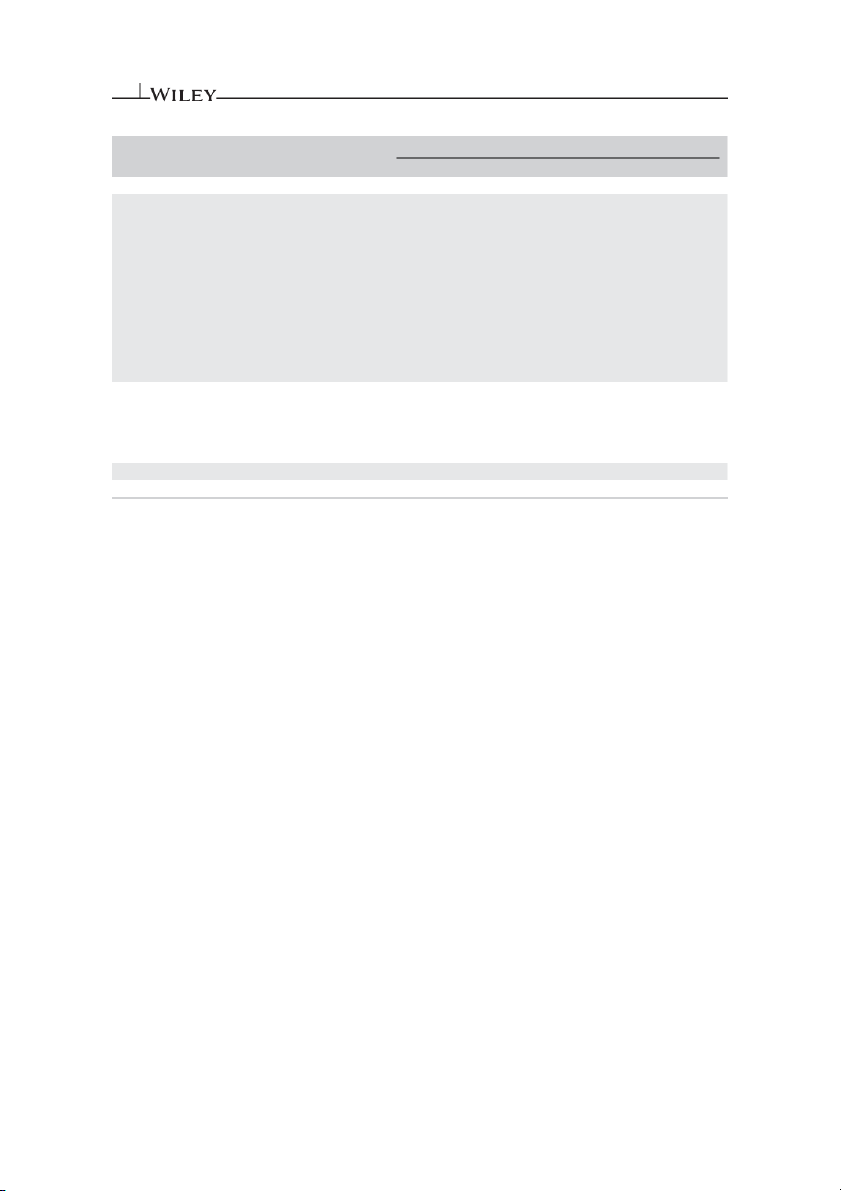

Descriptive statistics and correlations n loaded Variable M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 from h 1 Locality (proxy of 0.52 0.50 tt –– p s: corporate culture) //online 2 Management's salary 35.51 11.46 0.06* l –– ibrary 3 Service 0.50 0.50 0.20** 0.04 .w –– iley. 4 Finance 0.04 0.19 0.12** 0.20** 0.20** c –– o m /d 5 Organizational age 24.92 17.47 0.06* 0.07* 0.02 0.01 o i –– /10.1 6 Organizational size 4.98 1.24 0.10** 0.28** 0.01 0.07* 0.27** 0 0 –– 2 /hrm 7 Foreign stake 4.21 15.99 0.01 0.09** 0.13** 0.06* 0.01 0.16** –– .2215 8 Proportion of female 0.05 0.15 0.02 0.06* 0.07* 0.03 0.02 0.11** 0.01 9 –– by executives R M IT 9 GDMM (T1) 0.10 0.16 0.11** 0.02 0.31** 0.00 0.03 0.03 0.01 0.29** U –– N IV E 10 HPWS (T1) 8.63 4.56 0.04 0.43** 0.02 0.11** 0.05 0.31** 0.12** 0.09** 0.03 R S IT 11 HPWS (T2) 9.19 4.50 0.07* 0.32** 0.01 0.10** 0.07* 0.38** 0.19** 0.11** 0.04 Y L IB R 12 HPWS improvement 0.56 4.25 0.03 0.12** 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.07* 0.08* 0.01 0.08* A R (T2 Y –T1) , W il 13 Gender diversity of e 0.31 0.16 0.10** 0.10** 0.03 0.15** 0.02 0.09** 0.00 0.07* 0.18** y O n subordinates (T1) line Li 14 Organizational 1.63 0.55 0.11** 0.14** 0.07 0.06 0.09* 0.22** 0.10* 0.04 0.05 b rary performance (T3) on [0 15 Endogeneity control 0.10 0.03 0.28** 0.11** 0.16** 0.13** 0.02 0.16** 0.13** 0.04 0.20** 5 /03/20 Variable 10 11 12 13 14 15 2 3 ]. Se 10 HPWS (T1) e –– the T 11 HPWS (T2) 0.56** er –– m s an 12 HPWS improvement (T2 d –T1) 0.48** 0.46** –– C o n 13

Gender diversity of subordinates (T1) 0.14** 0.14** 0.00 d –– itions 14

Organizational performance (T3) 0.09* 0.18** 0.10* 0.06 ( –– h ttps: 15 Endogeneity control 0.24** 0.21** 0.03 0.16** 0.05 // –– o n line

Note: N = 1101. GDMM refers to gender diversity of middle management. Organizational performance (T3) was available from 644 organizations. The unit librar

of management's salary is one million won. T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; and T3 = Time 3. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. y .w iley.com/term

HR variables associated with work-life balance (i.e., selective work

conditional mediation model (Hayes, 2013). Before analyzing the data, s-and

hours and flexible work hours; yes = 1, no = 0) (Avery &

we centered the components for the interaction term around their -condi

McKay, 2006; Kato & Kodama, 2017) and family-friendly HR policies

respective means. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and cor- tions)

(maternity leave, parental leave, workplace childcare facilities, support

relations. We included the control variables at Step 1. Next, we exam- o n W i

for childcare cost, leaves for regular doctor visits during pregnancy,

ined the main effect of gender diversity of middle management at ley On

stillbirth vacation, and infertility leave; yes = 1, no = 0). We aggre-

Step 2. At Step 3, we added the moderating variable of gender diver- line L

gated all scores related to family-friendly HR policies. We also

sity of subordinates and its associated two-way interaction term ibrary

included favored recruitment processes for women (yes = 1, no = 0).

(i.e., gender diversity of middle management gender diversity of for rul

We then generated a predicted gender diversity of middle manage-

subordinates). As shown in Table 2, at Step 1, some of the control var- es of u

ment score and included it as an endogeneity control in the models.4

iables (i.e., management salary, organizational size, foreign stake, se; OA

HPWS at Time 1, and endogeneity control) reached (marginal) signifi- artic

cance, which accounted for 29% of the variance. Hypothesis H1 pre- les are 2.5 | Results

sents that gender diversity of middle management in an organization gover

is positively related to the level of HPWS improvement. At Step n ed by

Since all data have been conducted at an organizational level, multile-

2, gender diversity of middle management significantly predicted the the a

vel analysis such as hierarchical linear modeling or generalized latent

level of HPWS improvement (Model 2a: p

b = 1.95, SD = 0.73, p licab

and mixed modeling (GLLAMM) is not necessary for our study. We

p < 0.01), which supported Hypothesis H1. Hypothesis H2 states le Cre

believe that the PROCESS macro is a good tool to explore our

that subordinate gender diversity modifies the relationship between ative Commons License 109 10 JOO 9 ET AL. 0 5 0 x , 0, Do TA B L E 2 w

Results of hierarchical regression predicting high performance work system (HPWS) improvement n loaded

HPWS improvement (T2-T1) from htt Predictor

Model 1a b (SD)

Model 2a b (SD)

Model 3a b (SD) p s://on Intercept 0.39 (0.58) 0.59 (0.58) 0.66 (0.58) linelibr Control variables ary.wil

Locality (proxy of corporate culture) 0.04 (0.23) 0.03 (0.23) 0.11 (0.23) ey.com Management's salary 0.00 (0.00)** 0.00 (0.00)** 0.00 (0.00)** /doi/1 Service 0.19 (0.23) 0.02 (0.24) 0.05 (0.24) 0 .1002 Finance 0.42 (0.62) 0.35 (0.62) 0.31 (0.62) /hrm.22 Organizational age 0.01 (0.01) 0.01 (0.01) 0.01 (0.01) 1 5 9 b Organizational size 0.65 (0.10)*** 0.66 (0.10)*** 0.70 (0.10)*** y R M I Foreign stake 0.03 (0.01)*** 0.03 (0.01)*** 0.03 (0.01)*** T U N IV

Proportion of female executives 1.18 (0.76) 1.74 (0.79)** 1.82 (0.78)** E R S IT HPWS (T1) 0.55 (0.03)*** 0.55 (0.03)*** 0.56 (0.03)*** Y L IB Endogeneity control 6.66 (3.61)* 5.22 (3.64) 4.88 (3.62) R A R Y Independent variables , W ile

Gender diversity of middle management (T1) 1.95 (0.73)*** 1.26 (0.74)* y O n li

Gender diversity of subordinates 2.50 (0.71)*** n e Libr

Gender diversity of middle management Gender 15.48 (4.27)*** ary o diversity of subordinates n [05/0 F-value 43.77*** 40.67*** 36.99*** 3 /202 R2 0.293 0.298 0.314 3 ]. See th

Note: N = 1,101. GDMM refers to gender diversity of middle management. T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; T3 = Time 3. e Te

*p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01. rm s and Condition

gender diversity of middle management in an organization and the

bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CI ) to determine the sig- s 95% (http

level of HPWS improvement, such that this relationship is stronger

nificance of the conditional indirect effect. We tested the conditional s://onl

when subordinate gender diversity is higher. At Step 3, we found that

indirect effect using the SPSS PROCESS macro version 26 (Model 7; inelibr

the interaction of gender diversity of middle management and gender

Hayes, 2013). The conditional indirect effect was only found in the ary.w

diversity of subordinates was positively related to the level of HPWS presence of a higher ( i

b = 0.16, SD = 0.06, CI = [0.04, 0.30]) versus le 95% y .co

improvement (Model 3a: b = 15.48, SD = 4.27, p < 0.01). We found

lower level of subordinates' gender diversity (b = 0.07, SD = 0.06, m /term

that the respective variances explained by gender diversity of middle CI s 95% = [

0.22, 0.03]), thus supporting Hypothesis H4 (Table 4). -and

management, and the interaction term for HPWS improvement were -condi

1% and 2%. A follow-up simple slope test (see Figure 2) indicated that tions)

the relationship between gender diversity of middle management in 2.6 | Supplementary analyses o n W i

an organization and the level of HPWS improvement was positive ley On

(simple slope = 4.43, t = 5.56, p < 0.01) in the presence of higher gen-

Organizations that have greater improvement in HPWS may have line L

der diversity of subordinates (+1 SD), but was not significant (simple

more gender-diverse middle management. To address this concern, ibrary slope = 0.52, t =

0.77, p = 0.44) in the presence of a lower level

we used a cross-lagged approach (Finkel, 1995), which is “the optimal for rul of gender diversity of subordinates ( 1 SD). Accordingly,

way to understand causality in field settings” (Lang et al., 2011, es of u Hypothesis H2 was supported.

p. 605). This approach allowed us to compare the partial regression se; OA

Consistent with Hypothesis H3, the level of HPWS improvement

coefficients between variables measured at different time points. We artic

was positively related to organizational performance at Time 3 (Model

found that gender diversity of middle management at Time 1 was pos- les are

2b: b = 0.03, SD = 0.01, p < 0.01). HPWS improvement explained

itively related to the level of HPWS improvement at Time 2 (b = 0.05, gover

4.2% of the variance of organizational performance (Table 3).5

SD = 0.64, p < 0.05), but HPWS improvement at Time 1 was not sig- n ed by

Finally, to test Hypothesis H4, which states that the level of

nificantly related to gender diversity of middle management at Time the a

HPWS improvement mediates the interactive effect of gender diver- 2 ( p

b = 0.03, SD = 0.00, p = 0.28). The linkage between HPWS and p licab

sity of middle management and gender diversity of subordinates in an

organizational performance has been criticized for ambiguity of cau- le Cre

organization on the level of organizational performance, we per-

sality (Shin & Konrad, 2014; Wright et al., 2005). Thus, a reversed ative C

formed 10,000-sample bootstrapping (Hayes, 2013) and used the

causal relationship between organizational performance and the o m m o n s License