Preview text:

Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing

ISSN: 1054-8408 (Print) 1540-7306 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/wttm20

Customer experience and engagement in

tourism destinations: the experiential marketing perspective Raouf Ahmad Rather

To cite this article: Raouf Ahmad Rather (2020) Customer experience and engagement in tourism

destinations: the experiential marketing perspective, Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 37:1,

15-32, DOI: 10.1080/10548408.2019.1686101

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2019.1686101 Published online: 17 Dec 2019.

Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1 View related articles View Crossmark data

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=wttm20

JOURNAL OF TRAVEL & TOURISM MARKETING 2019, VOL. 37, NO. 1, 15–32

https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2019.1686101 ARTICLE

Customer experience and engagement in tourism destinations: the experiential marketing perspective Raouf Ahmad Rather

Department of Tourism Studies, Central University of Kashmir, Jammu and Kashmir, Kashmir, India ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY

Tourism destinations are increasingly offering experiential services to promote the development of Received 2 August 2019

their competitive advantage. This research investigates the effects of customers’ tourism engage- Revised 17 September 2019

ment with experiential marketing activities and develops and tests a framework in this area. Accepted 11 October 2019

Findings suggest that customer engagement’s dimensions exert differing effects on customer KEYWORDS

experience and identification, which subsequently affect behavioral intention toward destinations. Experiential marketing;

Findings also suggest the indirect effects of customer engagement dimensions on behavioural customer experience;

intentions via experience and identification. Further, findings propose the significant difference customer engagement;

between first-time and repeat-visitors in terms of the underlying constructs. Theoretical and identification; behavioral

practical implications of results are discussed.

intention; first-time visitors; repeat-visitors; destination; tourism Introduction

(2019) propose that customers don’t like to purchase

the product/s, but rather the stories behind and the

Market globalization is influencing tourism industry

experience enabled by offerings.

globally. Economic downturn, intensified competition,

The reason behind the current tourism boom is

and growth of new technologies offer opportunities as

a question asked by both academics and industry.

well as threats (Hollebeek & Macky, 2019; Hultman,

Experiential marketing has been derived from the experi-

Skarmeas, Oghazi, & Beheshti, 2015). Researchers con-

ence economy concept (Pine & Gilmore, 1998), that is

sider the tourism industry as a technology adoption

undoubtedly strongly present in the highly intangible

pioneer, which innovates from computerized reservation

experience economy (Le et al., 2019; Quan & Wang,

systems to new marketing practices and E-business

2004; Song et al., 2015; Tsaur, Chiu, & Wang, 2007), as

(Hultman et al., 2015). In the context of this, tourism

illustrated by Disneyland’s 1955 opening (Hannam, 2004).

service providers are promptly employing branding stra-

Therefore, what does a customer gets from tourism or

tegies parallel to those product marketers in an attempt

travel offerings? First and foremost, the customer’s per-

to highlight the tourist destination uniqueness (Usakli &

ceived benefits lie in experience. While economic offer-

Baloglu, 2011). In accordance with these developments,

ings like goods, commodities, or services are external to

tourism destination numbers have increased to cater

customer, experiences are intrinsically personal and exist

with the fast developing demand of global tourism.

only in the customer’s minds who have been engaged on

With the help of these technologies, customers are pro-

intellectual, physical, emotional, and/or spiritual level

gressively shaping their own tourism experiences, as

(Hol ebeek, Glynn, & Brodie, 2014; Pine & Gilmore, 1998;

substantiated by Pine and Gilmore’s (1998) experiential

Tsaur et al., 2007). A delightful experience would last long

marketing perspective (Le, Scott, & Lohmann, 2019;

in customer’s minds and influence their consequent beha-

Schmitt, 1999a; Song, Ahn, & Lee, 2015). Kumar, Rajan,

viors. Consequently, managing the customer’s experien-

Gupta, and Dalla Pozza (2019) claims that the business

tial environment is a key concern for the survival and

development is shifting from products toward customer-

competitive advantage of tourism firms.

based processes. This leads Prahalad and Ramaswamy

Despite these invaluable conceptual works on the

(2003, p. 12) to propose that “a new point of view is

experience economy, empirical study remains limited.

required, one that allows individual customers to actively

One main reason probably lies in the fact that few of

construct their own consumption experiences through

these theoretical writings offer an easily operationalizable

personalized interaction, thereby co-creating unique

foundation for empirical investigation (Brodie & Hollebeek,

value for themselves.” Likewise, Hollebeek and Macky CONTACT Raouf Ahmad Rather r.raouf18@gmail.com

© 2019 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group 16 R. A. RATHER

2011). One exception to this observation is indeed offered

unknown. Addressing this research gap, this study investi-

by Pine and Gilmore (1998), which explicitly operationalizes

gates CE’s nomological network in tourism destination

the experience economy in terms of four dimensions:

marketing context. In particular, this research explores the

Escapism, esthetics, education, and entertainment. In addi-

role of CE dimensions in driving customer experience and

tion, “Given the relatively nascent state of the customer

customer identification, and their impact on behavioral

experience (CX) literature, there is limited empirical work

intention. Moreover, various constructs and variables

directly related to customer experience and the customer

have been examined as the consequences of CE in extant

journey” (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016, p. 70). For example,

research, incorporating brand usage intention and self-

“there is a strong need to explore how extant marketing

brand connection (Hollebeek et al., 2014), brand trust and

constructs, like customer engagement (CE) and commit-

co-creation (Rather, Hollebeek, & Islam, 2019), repatronage

ment, relate to customer experience and interact with each

intent and brand experience (Islam et al., 2019), electronic

other, resulting in the overall customer experience” (Lemon

word-of-mouth (Taheri, Jafari, & O’Gorman, 2014), satisfac-

& Verhoef, 2016, p. 85). Moreover, “there is a critical need

tion and loyalty (Rather, 2018a; So et al., 2014). Although

for researchers to develop and test such an integrated

given its relative significance, empirical research to under-

conceptual model of customer experience and the custo-

stand engagement while actually experiencing tourism

mer journey” (Homburg, Jozić & Kuehn, 2017; Lemon &

destinations/offerings are scant. Thus, there are few exist-

Verhoef, 2016, p. 85). Because of the absence of sound

ing studies and none (to our knowledge) in the area of

measurement development for CX, there exists a scarcity

tourism destination marketing that explores the associa-

of research on how CX can be affected and on the con-

tion between customer engagement dimensions and cus-

sequences of CX (Homburg et al., 2017; Lemon & Verhoef,

tomer experience and other related variables (e.g.

2016). Research have mostly investigated the drivers of

customer identification, behavioral intention) that are

customer value, commitment or satisfaction (e.g. Hultman

deemed to be of interest to tourism destinations/firms.

et al., 2015; Rather & Hollebeek, 2019; Song et al., 2015) but

Further, since engaged and loyal visitors have constantly

haven’t measured CX drivers as a broad construct (Islam,

been recognized as essential factors for market segment

Hollebeek, Rahman, Khan, & Rasool, 2019; Lemon &

(Brodie & Hollebeek, 2011; Liu, Lin, & Wang, 2012), little is

Verhoef, 2016; Verhoef et al., 2009). Thus, this research

known about the differences relating to first-time custo-

extends this gap by exploring the role of CE as a driver of

mers and repeat visitors (e.g. Chua, Lee, & Han, 2017; Li,

customer experience in a broader nomological network.

Cheng, Kim, & Petrick, 2008; Liu et al., 2012). The differences

Customer engagement/CE has transpired as a construct

between first-time and repeat tourists are getting more

of growing relevance in topical marketing literature and as

interest from the marketing and tourism scholar’s perspec-

a new technique in fostering consumer value and under-

tive. Information regarding visitor’s status like first-time

standing contemporary marketing (Brodie, Hollebeek,

and/or repeat tourists could be helpful in identifying

Jurić, & Ilić, 2011; Harrigan, Evers, Miles, & Daly,

a tourism destination’s position in its life cycle, signalling

2018; Hollebeek et al., 2019a; Kumar et al., 2019). The MSI

destination familiarity and market segmentation (Li et al.,

(2014–2016) and (2016–2018) positioned CE and CX as the 2008).

most significant research challenges in upcoming years.

Recent destination marketing and management

Over the previous decade, customer engagement research

research (e.g. Chen, Drennan, Andrews, & Hollebeek,

has been performed with online foci or substantial service

2018; Hultman et al., 2015; Le et al., 2019; Rather,

(e.g. Hollebeek & Andreassen, 2018). For example, existing

Hollebeek et al., 2019; Song et al., 2015; Taheri et al.,

research has examined customer engagement in virtual/

2014) develops on conventional marketing and branding

social media brand communities (e.g. Hollebeek et al.,

literature (such as Aaker, 1997), that proposes individuals

2014), with reference to hedonic (vs. utilitarian) brands

likely to identify towards brands or destinations. Customer

(Hollebeek, 2011) and integrated resort brands (Ahn &

engagement and customer brand identification/customer

Back, 2018), to name a few. In tourism/destination market-

identification are critical in purchase likelihood, brand

ing and management that signifies a particular service

choice, and finally success of brand (e.g. Aaker, 1997;

subsector, this research identifies studies which address

Hollebeek et al., 2014; Kumar & Kaushik, 2018). An exten-

customer engagement in heritage places/sites (Bryce,

sive consent subsists in management and marketing lit-

Ross, Kevin, & Taheri, 2015), social media interactions

erature on three different statements: (i) CE can lead to

(Harrigan et al., 2018), luxury hotel brands (Islam et al.,

sustainable competitive advantage, value-creating consu-

2019; Rather & Camilleri, 2019), and airline brands (So,

mers and develop strong loyal consumer base (ii) retain-

King, & Sparks, 2014), amongst others. In spite of extant

ing consumers is good business, and (iii) customer

insight, the role of tourism destination customer engage-

experience and identification are main drivers for future

ment and its specific conceptual associations remain

customer behavior, particularly in tourism, in which

JOURNAL OF TRAVEL & TOURISM MARKETING 17

intangible services/offerings are hard to assess before

thrill-seeking), which typically result from participation

consumption (Hultman et al., 2015; Kumar & Kaushik,

and/or direct observation in events, whether dreamlike,

2018; Kumar et al., 2019; Lemon & Verhoef, 201 ) 6 .

virtual or real (Schmitt, 1999b). In the tourism context,

Building on the above gaps, this study makes important

experience has been viewed as a subjective mental state

theoretical and managerial contributions. First, as sug-

felt by consumers (Tsaur et al., 2007). Further, experiences

gested multiple authors have called for more empirical

are normally not self-generated but induced. Experiences

studies that investigate CE phenomena, particularly in the

are linked to events which they react to. Furthermore,

tourism context (Harrigan et al., 2018; Kim & Chen, 2019; So

experiences can be described as complex, emerging

et al., 2014; Taheri et al., 2014). This research satisfies these

structures, that is, no two experiences are alike accurately

calls by investigating two major outcomes of customer

(e.g. Schmitt, 1999b; Tsaur et al., 2007).

engagement dimensions namely customer experience

In marketing, the idea of experience was first discussed

and identification and offers a framework in this area.

and conceptualized in the topical work of Hirschman and

Due to this association, the present research uncovers the

Holbrook (1982), which has to turn out to be an important

insights into those CE dimensions which are more favor-

element in understanding customer behavior through the

able in building tourism customer experience and identifi-

overall consumption experience (Coudounaris & Sthapit,

cation. This study thus examines the association between

2017; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). The experiential facets of

CE and CX, which although being studied conceptually so

consumption emerged at 1990s after Pine and Gilmore

far (e.g. Hollebeek, 2011; Hollebeek & Andreassen, 2018;

(1998) addressed how economies change. Economic activ-

Lemon & Verhoef, 2016), to the best of our information lags

ities intend not only for output but for experience through

behind as for empirical exploration is concerned.

consumption (Quan & Wang, 2004). Pine and Gilmore

The advancement of increased insight into customer

(1998) further advocate that experience represents

engagement’s role in influencing consumers’ overall jour-

a specific type of economic offering that generates compe-

ney-linked perceptions thereby reveals a worthwhile con-

titive benefit which is difficult to imitate or substitute.

tribution to the marketing and management literature

Based on these developments, Hirschman and Holbrook

(Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). Second, this research tests the

(1982) and Lemon and Verhoef (2016) propose customer

mechanism through which these outcomes affect beha-

experience orientation as an eminent approach for scholars

vioural intention. Third, the present research explores the

as well as marketing practitioners. Schmitt (1999a) argues

indirect effects of CE including affective, cognitive, and

that because traditional marketing provides a rational,

behavioral dimensions on behavioural intention through

engineering-driven and outdated, a need exists for the

customer experience and identification in tourism destina-

development of experiential marketing. The author also

tions. Fourth, this study also intends to explore the differ-

suggests that what consumer’s desire is communications,

ence between first-time and repeat customers in terms of

products, and marketing campaigns which touch their

customer’s engagement, experience, identification, and

hearts, overwhelm their senses, stimulate their minds and

loyalty constructs. Finally, future research directions are

include into their lifestyles. Customers thus desire for com-

discussed to address research gaps in the literature.

munications, marketing campaigns and offerings to deliver

Practically, the study findings reveal that CE makes an experience.

a substantial contribution to customer experience, there-

Consequently, experiential marketing is increasingly uti-

fore revealing a superior level of managerial significance.

lized by marketers to build experiential connections with

This study thus presumes that not only customer engage-

consumers (Homburg et al., 2017; Le et al., 2019; Schmitt,

ment should be regarded as an integrated strategic and 1999a). Schmitt 1

( 999a, 1999b) suggested the strategic

core aspects to promote increased customer experience,

experiential modules (SEMs) concept which marketing man-

but also guides to strong customer’s identification, which

agers can adopt to generate different kinds of CX for their

in turn effects behavioural intention.

consumers (Song et al., 2015; Tsaur et al., 2007). In experi-

ential marketing, the experiential modules include affective

experiences (FEEL), sensory experiences (SENSE), creative

Theoretical framework and hypotheses

cognitive experiences (THINK), behaviors and lifestyles

Experiential marketing is a rising marketing management

(ACT), social-identity experiences and physical experiences

philosophy (Le et al., 2019; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016; Song

which result from relating to a reference group/culture

et al., 2015; Tsaur et al., 2007), which has been shown

(RELATE). Experiential marketing aims to generate compre-

effective in driving tourist behavior (Brun, Rajaobelina, hensive integrated experiences which possess

Ricard, & Berthiaume, 2017; Rather, 2018c; Sharma &

simultaneously the qualities of FEEL, SENSE, ACT, THINK,

Nayak, 2019). Experiences are private events, which hap-

and RELATE. Each of these dimensions/aspects is

pen in reply to customer’s sense(s) being stimulated (e.g. discussed below. 18 R. A. RATHER Sense marketing Relate marketing

SENSE marketing or SENSE module are focused on

RELATE marketing extends outside the customer’s pri-

senses by generating sensory experiences due to sight,

vate, personal feelings, thereby linking the customer to

taste, touch, sound, and smell. Sense is the key response

something beyond its private state. RELATE campaigns

in which one individual engages in an experiential envir-

enrich customer’s desire for self-improvement (such as

onment. SENSE marketing can be employed to distin-

a future “ideal self”, which she/he desires to relate to).

guish firms, products, and brands (e.g. destinations) to

Relate appeal to the need to be recognized positively by

motivate consumers by adding value to products/ser-

others like one’s family, peers, and colleagues (Schmitt,

vices (e.g. through excitement or aesthetics) (Schmitt,

1999a). They relate the visitors to a large social system 1999a; Tsaur et al., 2007).

like sub-culture, a country, so on (Tsaur et al., 2007). Feel marketing Customer engagement

FEEL marketing enriches consumer’s emotions and

Although the engagement concept is examined across

inner feelings by generating affective experiences

fields including psychology (such as task engagement),

which range from slightly positive moods related to

organizational behavior (like employee engagement),

a brand/destination (e.g. for a non-involving) to

sociology (like civic engagement), and marketing (like

strong feelings/emotions of pride and joy (e.g. for

customer engagement; Ahn & Back, 2018; Hollebeek,

a customer durable, social marketing campaign or

Srivastava, & Chen, 2019b; So et al., 2014; Verhoef, technology) (Schmitt, 1999a).

Reinartz, & Krafft, 2010), its dynamics in particular set-

tings such as tourism remain nebulous (Harrigan et al.,

2018; Rather, Hollebeek et al., 2019; Taheri et al., 2014). Think marketing

The conceptualization and dimensionality of CE have

been a key topic of discussion. Based on different theo-

THINK marketing appeals to the intellect by generating

retical viewpoints, few researchers suggest customer

problem-solving, cognitive experiences, which engage con-

engagement to encompass both in-role and extra-role

sumes creatively. In tourism, one of the objectives is har-

consumer emotions, cognitions and behaviors (Islam

mony. It proposes that the tourism destination authority

et al., 2019; Kumar et al., 2019), whereas other authors

allocates itself to harmonizing the relationship between

restrict its scope to extra-role merely (e.g. helping beha-

nature and humankind. In tourism, various educational

viors/consumer citizenship (Van Doorn et al., 2010). The

tours accumulate the ideas of environmental security

present employs the former perspective which provides

on the explanation boards to engage its visitor’s divergent

a most influential, inclusive outlook of customer engage-

and convergent thinking via surprise, intrigue, and

ment (e.g. Harrigan et al., 2018; Hollebeek et al., 2014,

provocation (Tsaur et al., 2007). Such reconsiderations cre-

2019). Similarly, given its interactive theoretical roots

ate the problem-solving and cognitive experiences for its

(Brodie et al., 2011), customer engagement has been customers/visitors. viewed from relationship marketing perspectives

(Rather, 2018a) and SD logic perspectives (Hollebeek

et al., 2019b). These authors view customer engagement Act marketing

as customers’ resource investments in their interactions

ACT marketing appeals consumer’s lives by focusing their

(Kumar et al., 2019), which is highly relevant in tourism

physical experiences, showing customers alternative life- destination marketing.

styles and interactions, alternative ways of doing things.

Relatedly, there is no consent about CE’s definition. For

Rational perspectives to behaviour change (e.g. theories

example, Brodie et al. (2011, p. 258) defined CE as “a psy-

of reasoned actions) are just one of the several behavioural

chological state, which occurs by virtue of interactive cus-

change alternatives (Schmitt, 1999a). Changes in beha-

tomer experiences with a focal object (e.g. a brand/

viours and lifestyles are usually most inspirational, emo-

destination)”. Van Doorn et al. (2010, p. 254) defined CE as

tional and motivational and normally inspired by

“behaviors that go beyond transactions and may be speci-

exemplars like athletes or movie stars. In tourism, customers fically d fi

e ned as a customer’s behavioral manifestations

understand ways to appreciate focal objects (like other

that have a brand or firm focus, beyond purchase, resulting

customers) and change their lifestyles and attitudes (Tsaur

from motivational drivers”. Hollebeek et al. (2014, p. 154) et al., 2007).

define it as “a consumer’s positively valenced brand-related

JOURNAL OF TRAVEL & TOURISM MARKETING 19

cognitive, emotional and behavioral activity during or

et al., 2017), that, for Lemon and Verhoef 2 ( 016), could be

related to focal consumer/brand interactions”. Regardless

extended to other spiritual, sensory, and physical aspects.

of these differences, CE has been widely viewed to include

CX as a broad construct includes three typical phases of

affective, cognitive and behavioral dimensions, thus reveal-

purchase e.g. pre-purchase, purchase and post-purchase.

ing its multidimensional aspect (Harrigan et al., 2018;

Thus, it is a process which amalgamates cognitive as well as

Hollebeek et al., 2014; Taheri et al., 2014). Consequently,

affective components (Verhoef et al., 2009). Homburg,

omission of CE’s psychological aspects or behavioral activ-

Schwemmle, and Kuehnl (2015, p. 8) define CX as “the

ities would likely provide insufficient insight to properly

evolvement of a person’s sensorial, affective, cognitive,

investigate the concept (Ahn & Back, 2018; Hollebeek

relational and behavioural responses to a brand by living

et al., 2014). Although, neither the behavioral activities nor

through a journey of touch points along pre-purchase,

psychological aspects alone reflect the CE in full. True CE

purchase and post-purchase and continually judging this

should reveal the psychological connection in addition to

journey against response thresholds of co-occurring experi-

interactive behavioral participation towards the brand/

ences.” Lemon and Verhoef (2016) assert that CX results due

object (Ahn & Back, 2018; Rather, Hollebeek et al., 2019).

to the interaction between the consumer and parts/ele-

Thus, this study employs three-dimensional (cognitive,

ments of firm, like services, products, or employees.

affective, and behavioral) CE in this study (Ahn & Back,

Experience is specific to each consumer; thus, it is

2018; Hollebeek et al., 2014). Relatedly, cognitive CE refers

a personal experience with distinct levels of involvement

to “a consumer’s level of brand-related thought processing

including emotional, sensorial, rational, physical, and

and elaboration in a particular consumer/brand interac- spiritual.

tion”. Secondly, affective CE is defined as “a consumer’s

Brakus, Schmitt and Zarantonello (2009, p. 54) argue

degree of positive brand-related affect in a particular con-

that “customer experience . . . differs from motivational

sumer/brand interaction”. Thirdly, behavioral CE refers to “a

concepts, such as involvement,” thus further differenti-

consumer’s level of energy, effort and time spent on

ates brand/customer experience from customer engage-

a brand in a particular consumer/brand interaction”

ment’s motivational aspect (Hollebeek & Macky, 2019). In

(Hollebeek et al., 2014, p. 6).

spite of such differences, both CX and CE fit in

Given the interactive aspect of customer engagement,

a relational paradigm that aims to optimize consumer–

it has specific significance towards service context which

brand interactions from consumer and company view-

is typified by high customer–brand interaction (e.g.

points (e.g. Islam et al., 2019). Eventually, customer

Hollebeek & Macky, 2019; Islam et al., 2019; Rather, engagement’s intra-interaction focus ends in

Hollebeek et al., 2019). For instance, tourists are looking

a particular brand experience (e.g. Hollebeek &

for transformative, engaging, interactive, and enjoyable

Andreassen, 2019, Islam et al., 2019). Engaged customers

activities, often surrounding temporary modes of being.

are expected to play a key role in cocreating customer

On the basis of these features, customer engagement

experience and value (Brakus et al., 2009; Lemon &

has been generally examined via service-dominant (SD)

Verhoef, 2016). Furthermore, customer engagement’s

logic, which alike CE emphasizes the improvement of

influence on experience is addressed in hotel contexts

perceived value by virtue of interactivity (see Brodie

(Islam et al., 2019), and online branding literature

et al., 2011; Hollebeek et al., 2019b; Islam et al., 2019).

(Hollebeek et al., 2014). Therefore, regardless of concep-

tual assertions of customer engagement’s influence on

CX, this relationship is yet to be investigated empirically

CE as an antecedent of customer experience

as for our best knowledge. In response to this gap, we

Customer experience or CX acts as a crucial driver of com-

aim to investigate this association in tourism destination

petitive advantage and commercial success (Kim & Chen,

marketing context. This research proposes CE’s dimen-

2019; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). Regarding marketing – spe-

sions (i.e. cognitive, affective and behavioral) as impor-

cifically tourism destination services practitioners and aca-

tant predictors of customer experience with tourism

demics settle that focusing on CX is helpful and may destinations/sites. Thus:

generate a sustainable and unique advantage for any

brand (or destination) (Sharma & Nayak, 2019; Song et al.,

H1: Cognitive CE with the tourism destination positively

2015; Tsaur et al., 2007). Thus, defining CX concept and

influences customer experience.

ascertaining how to measure it is crucial for marketing

(Lemon & Verhoef, 2016; Sharma & Nayak, 2019). For exam-

H2: Affective CE with the tourism destination positively

ple, CX involves emotional and rational evaluations (Brun

influences customer experience. 20 R. A. RATHER

H3: Behavioral CE with the tourism destination positively

value for them (e.g. status, affiliation, identification;

influences customer experience.

Hollebeek, 2011; Rather & Hollebeek, 2019). Consumers

exchange, economic, social, emotional, cognitive, and phy-

sical resources with service marketers (e.g. Hollebeek, 2011;

Rather, 2018a). For customer engagement to persist both

Customer identification as a consequence of CE

consumer and marketer have to state that it is equivalent

(Harrigan et al., 2018; Rather, 2018a), defining customer

Social identity theory or SIT is a key theoretical underpin-

engagement as a social exchange. These claims imply

ning for marketing based customer identification (Hultman

that when tourists are engaged, they tend to identify

et al., 2015; Mael & Ashforth, 1992; Rather, Tehseen, &

themselves towards the destination/brand. Hence, higher

Parrey, 2018). Based on SIT, customer–brand identification

the customer’s cognitive, affective and behavioral engage-

or customer identification denotes a consumer’s psycholo-

ment, higher is the customer’s identification with the des-

gical state of feeling, perceiving and valuing their belong-

tination brand. Therefore, it is hypothesized:

ingness with the offering/brand (Rather & Hollebeek, 2019).

SIT proposes that individuals can spend substantial efforts

H4: Cognitive CE with the tourism destination positively

to build their own social identity, besides their personal

affects customer identification.

identity (e.g. Bhattacharya & Sen, 2003; Rather, Tehseen,

Itoo, & Parrey, 2019). These claims also fit with social

H5: Affective CE with the tourism destination positively

exchange theory or SET that focus on individuals’ likely

affects customer identification.

rewards from their social efforts (Hollebeek, 2011), thus

revealing a proper linkage between these perspectives as

H6: Behavioral CE with the tourism destination positively employed in the present research. Researchers

affects customer identification.

applied identification to consumer–brand relationships

(Bhattacharya & Sen, 2003; Rather & Hollebeek, 2019).

Behavioural intention as a consequence of

These researchers contend that consumers have social as customer identification

well as personal identities which collectively contribute to

their self-images. Customers engage in a matching process

Oliver (1997, p. 28) defined behavioral intention as

to identify offerings or brands which are congruent with

a “stated likelihood to engage in a behavior”. Zeithaml,

their sense of self (Escalas, 2004; Hultman et al., 2015). In

Berry, and Parasuraman (1996) conceptualize four types

line with this, Sprott, Czellar, and Spangenberg (2009)

of behavioral loyalty including purchase intention, price

argue the customer–brand engagement (CBE) in self-

sensitivity, complaining behavior and word-of-mouth.

concept construct, wherein CE and customers’ identifica-

Understanding how brands affect consumer behavioral

tion are linked. Hollebeek et al. (2014) ponder consumer

intention is key, as it is an indicator of actual ensuing

self-brand connection (SBC) as a consequence of CE that

consumption behavior (Ahn & Back, 2018; Coudounaris

develops from consumers’ particular interactive brand

& Sthapit, 2017; Rather & Hollebeek, 2019; Zeithaml et al.,

experiences. The connections that customers generate

1996). Strong customer’s identification can prove vital for

between a brand (e.g. destination) and their own identity

developing long-term relationships (Bhattacharya & Sen,

are known as customer identification. Consequently, desti-

2003; Rather, 2017, 2018b; Rather & Hollebeek, 2019),

nation brand/s is believed to be most important the more

such as by affecting brand re-buying intentions. Further,

closely they link to self (Kumar & Kaushik, 2018). Coherent

researchers recommend that identification increases cus-

with the literature, this study advocates that cognitive,

tomers’ resistance towards switching brands (Lam,

affective, and emotional CE will persuade customer’s iden-

Ahearne, Hu, & Schillewaert, 2010). In nation-brand set-

tification. For instance, Hollebeek et al. (2014) suggested

tings, people who articulated higher identification

that consumers’ cognitive and affective CE in social media

towards nation as a brand were most expected to visit

serve to predict customer’s self-brand connection and

and/or revisit the destination in future (Stokburger-Sauer,

identification towards the offering/brand. Relatedly,

2011). Through social identity theory-based insights, cus-

Harrigan et al. (2018) propose that customers engage

tomer identification could be employed to enlighten var-

actively towards social media tourism brands, and their

ious consumer-based consequences, including customer–

self-brand connection and/or identification is reinforced.

brand loyalty (Rather & Hollebeek, 2019). Thus, the cur-

Clearly, this connects their brand to the customer’s identity.

rent research proposes that tourists build heightened

As social exchange theory (SIT) implies that customers

loyalty with tourism destination by re-visiting it in the

would invest resources only when the exchange creates

nearby future if they cater to build a strong relationship

JOURNAL OF TRAVEL & TOURISM MARKETING 21

and identification with that specific tourism destination.

tourism destination extensively, whereas repeat-tourists Hence, it is assumed that:

explore it more intensively, spending more time at sites/

places by visiting smaller number of sites/places (Liu et al.,

H7: Customer identification with the tourism destination

2012). Moreover, first-time tourists start to gather informa-

positively affects behavioural intention.

tion earlier than repeat tourists (Li et al., 2008). In making

travel decisions, first-time tourists depend highly on recom-

mendations from friends, family, and travel professionals

(e.g. Li et al., 2008). Lehto, O’Leary, and Morrison 2 ( 004)

Behavioural intention as a consequence of

examined the effects of prior experience on vacation beha- customer experience

vior. They assert that repeat-trip varies from regular service/

Prior research has examined customer experience in zoos

product re-purchases as prior-trip experiences can’t be

(e.g. Tsaur et al., 2007), travel agencies (Rajaobelina, 201 ) 8 ,

duplicated. Further, a more differentiated and complex

wineries (Lee & Chang, 2012), resorts (Ahn & Back, 2018),

brand image and identification of tourism site builds

theme parks (e.g. Kao, Huang, & Wu, 2008), and yoga

once tourists spend some amount of time there (e.g.

tourism (Sharma & Nayak, 2019), to name a few.

Fakeye & Crompton, 1991; Lehto et al., 2004). Likewise,

Experience has also been used in tourism. For example,

Wang (2004) claims that repeat-tourists are more involved

previous research indicates that experiential marketing

in local life-linked activities, engaged in smaller number of

positively effects tourist emotions, satisfaction, and beha-

activities and tend to stay longer than first-time tourists. In

vioural intent in zoos (Lee & Chang, 2012; Tsaur et al.,

addition, while making travel decisions, repeat tourists

2007) and customers with a better experience tend to

depend largely on their personal experiences compared

recommend the firm to others. Therefore, we postulate

to other information sources, and thereby spent smaller

that customers develop strong loyalty (revisit) intentions

amount of time on travel planning (e.g. Li et al., 2008).

toward a destination if they have a positive experience

Hence, attaining support from the literature presented

with that destination. Recently, Sharma and Nayak (2019)

above, this study proposed that:

also found the influence of memorable tourism experi-

ences on tourist’s behaviour via destination image and

H9: There is a significant difference between first-time

tourist’s satisfaction. In the same way, CE is likely to estab- tourists and repeat tourists.

lish the core relationship marketing tenets of consumer/

tourist retention, loyalty and repeat patronage through Methodology

influencing CX (Verhoef et al., 2009, 2010). Hence, acquir-

ing support from the literature presented above, it is Research site

presumed in a tourist destination that:

Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) is the northern-most state of

India placed in the Himalayan Mountains. J&K is home to

H8: Customer experience with the tourism destination

various valleys like the Kashmir valley, Chenab valley, Sindh

positively affects behavioural intention.

valley, and Lidder valley. The famous and major tourism

sites/destinations of J&K, includes Srinagar, Gulmarg,

Differences between first-time and repeat

Phalgam, Kokernag, Daksum, and Jammu, were selected visitors

as the study settings for this research due to various rea-

Difference between first-time visitors and repeat visitors in

sons. Firstly, as mentioned, these sites/places provide pop-

terms of customer-based outcomes including experience,

ular tourism destinations in India. Secondly, these

identification, loyalty and satisfaction is questionable (Chua

attractions/destinations are well-renowned tourist spots,

et al., 2017; Shavanddasht & Allan, 2019). In tourist destina-

which offer leisure, recreation, cultural, adventure, religious

tion context, few research works indicated that first-time

and other attractions, thus providing broad insight into

customers showed a higher satisfaction level towards

consumer behaviors and motivations. Thirdly, in India, the

a destination compared to repeat customers (e.g. Liu

tourism industry offers a growing and substantive contri-

et al., 2012; Shavanddasht & Allan, 2019), other research

bution to employment and gross domestic product (IBEF,

studies indicated that the levels of satisfaction and loyalty

2019; UNWTO, 2017). Finally, the strong level of customer-

of repeat tourists have been more compared to first-time

provider interactivity in tourism makes the significance of

tourists (Li et al., 2008). Research established that first-time

investigating relational concepts, like customer engage-

customers are most expected in search of different experi-

ment and experience (Ahn & Back, 2018; Hollebeek &

ences (e.g. Liu et al., 2012). First-time customers explore the

Rather, 2019; Taheri et al., 2014). 22 R. A. RATHER Sampling and data collection

missing values. At last, 520 questionnaires were retained

for final examination that resulted in 83.67% of response

Using self-administrated survey technique, data were col-

rate (i.e. 520/600 = 83.67%). The descriptive analyses

lected from a major tourist destination that includes

revealed that 56% of sample were male and 44% female.

Srinagar, Gulmarg, Kokernag, Daksum, Jammu, and

An examination of the respondents’ age shows that 31%

Phalgam in Jammu and Kashmir, India. Both domestic

were 20–30 years, 20% of respondents were 31–49 years,

and international tourists visiting these destinations

29% of respondents were 41–50 years, while 20% were

were targeted to conduct the survey. Convenience sam-

above 51 years. With respect to respondents' educational

pling has been used to choose the participants for this

qualification, 10% had matriculation degree, and 40% had

research (Parrey, Hakim, & Rather, 2019; Taheri et al.,

graduation and post-graduation degrees, respectively.

2014). Questionnaire was pre-tested with a convenience

With respect to travel purposes, 70% were leisure, recrea-

sample of 40 participants in 10 days. On the basis of

tional, and adventure visitors, followed by 20% religious

results, relevant items were modified as required to

visitors, and 10% business clients. Moreover, 51% of visi-

ensure the clarity of items. Results showed no concerns

tors were first-time and 49% were repeat visitors.

about the readability of questionnaire. In the final study,

The sample profile of tourist/respondents is indicated

participants were asked to rate the items on 7-point Likert in Table 1.

scales ranged from 1 = strongly-disagree to 7 = strongly-

agree. Data have been collected from the tourists with the

help of four field investigators. The whole process of data Measures

collection has been examined personally by the author.

Data have been collected mostly during holidays, winter

A questionnaire was adopted to measure the variables

and summer periods when huge numbers of domestic as

or constructs enclosed in the proposed conceptual fra-

well as international visitors visiting at the above men-

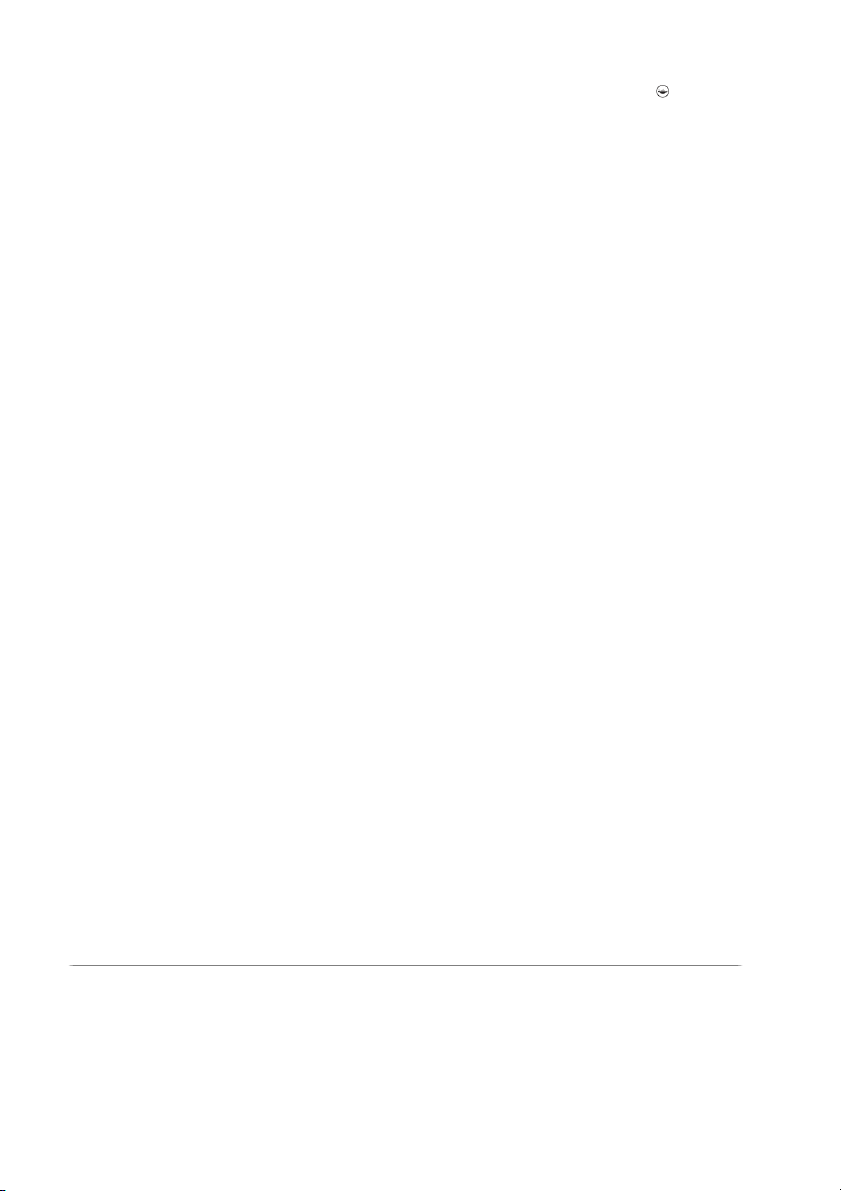

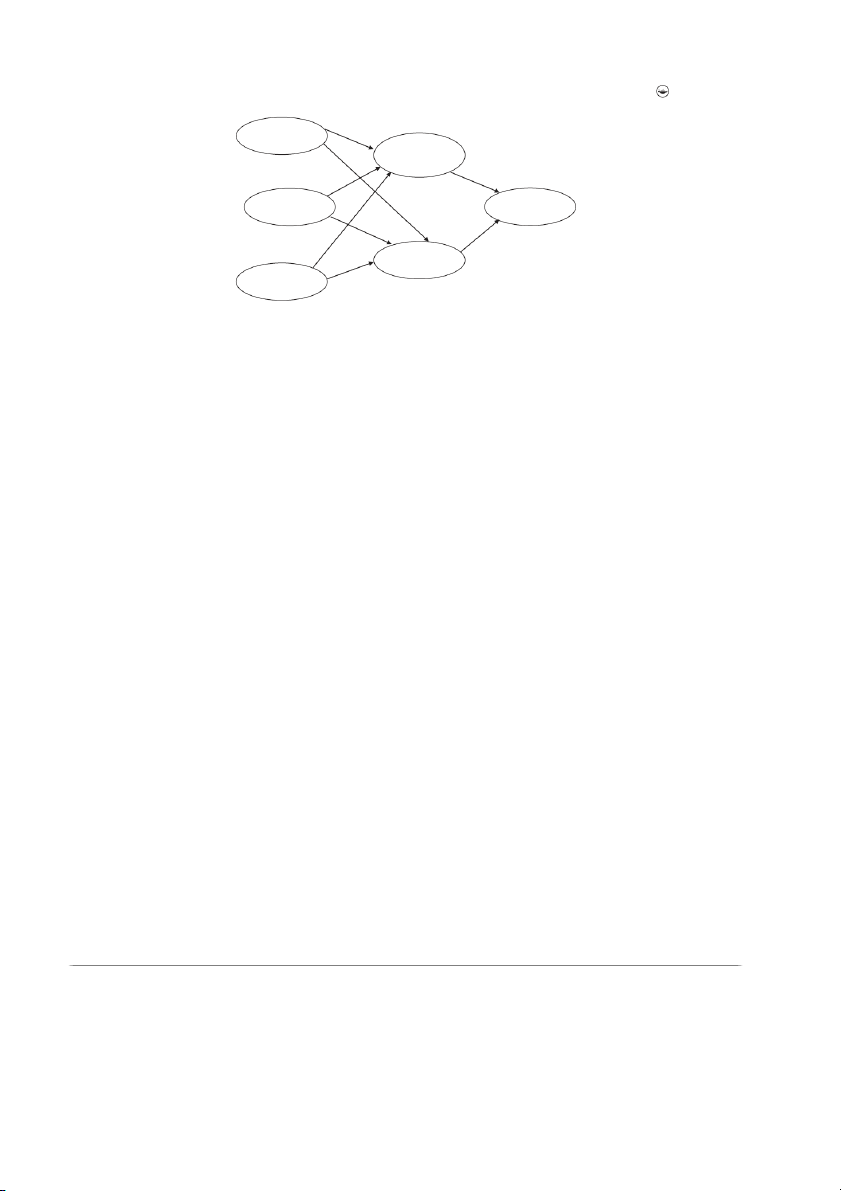

mework, as shown in Figure 1. The conceptualization of

tioned major tourism destinations. The surveys were con-

brand or customer experience is based on the strategic

ducted during the period of December 1 2018 to May 31

marketing management literature (Brakus et al., 2009;

2019. Surveyors approached tourists in the major areas

Pine & Gilmore, 1998; Schmitt, 1999a, 1999b) where the

where the possibility of finding tourists was maximum like

concept has been considered as a vital element for

hotels, bus stands, railway stations, relaxation spots, and

theory construction and testing. The construct has its

destination sites. This technique was often used by many

origins in Brakus et al. (2009) original brand experience

studies (e.g. Bryce et al., 2015; Sharma & Nayak, 2019).

scale but has been adapted to this research based on

Surveyors approached travelers and requested a few

Tsaur et al.’s (2007) more tourism specific five-

screening questions (like, are you a tourist? and your

dimensional conceptualization of customer experience,

main purpose of visiting the specific destination?). It facil-

including sense, relate, feel, think, and act. The customer

itates to determine the respondents' suitability in line with

experience dimensions were captured with 12 items in

the objectives of this research. Those suitable visitors who

total. A sample item includes: “I would like to share what

joined eagerly in the survey have been requested to recall

I experienced in this destination”. Customer engagement

their latest tourism destination experience in selected

tourism destinations. On an average, the participants Table 1. Sample profile.

take nearly 10 minutes to complete the questionnaires. Respondents’ Respondents

Based on the ratio of sample size to variables/items Variables Categories proportion (n = 520)

under examination, the present research estimated the Gender Male 56% 292

required sample size (Hair, Anderson, Babin, & Black, Female 44% 228 Age (years) 20 – 30 31% 162

2010). For that reason, 5:1 ratio is regarded as minimum; 31 – 40 20% 104

10:1 ratio is suggested as most acceptable; and 20:1 ratio 41 – 50 29% 150 Above 51 20% 104

is regarded as the more desired (Hair et al., 2010). As 29 Qualification Matriculation 10% 52

variables/items investigated in the present study, Graduation 40% 208

a sample size of minimum 580 (i.e. 29 * 20 = 580) has Post-graduation 40% 208 Others 10% 52

been considered as adequate (Hair et al., 2010). For data Reasons for Leisure 40% 208

collection, 600 customers have been approached. Five travelling Adventure 30% 156

hundred and thirty visitors/customers filled their ques- Religious 20% 104

tionnaires and send back it to field investigator. Out of Business 10% 52 Visitation First time visit 51% 266

530 filled questionnaires received from participants, 10 status

were deleted owing to the existence of outliers and Repeat visit 49% 254

JOURNAL OF TRAVEL & TOURISM MARKETING 23 Cognitive H1 Engagement Customer H4 Experience H2 H8 Affective Behavioural Engagement Intention H5 H3 H7 Customer Identification Behavioral H6 Engagement

Figure 1. Conceptual framework.

was measured by employing Hollebeek et al.’s (2014)

analysis has been employed to assess the psychometric

ten-item multidimensional scale with a sample item:

properties of the variables/constructs (Table 2). Survey

“Using this tourism destination stimulates my interest to

data have been tested for the measurement adequacy

learn more about this destination”. Customer identification

and underlying factor structure. Initially, standardized

was gauged by using Kumar and Kaushik (2018) four-

factor loadings (SFLs) for all items/indicators were eval-

item scale. A sample item includes: “If a story in the media

uated to verify if the items load on their own constructs.

criticized this destination, I would feel embarrassed”.

The results signify the substantial convergent validity,

Finally, behavioral Intention items were sourced from

where SFLs are above 0.70 (e.g. Hair et al., 2010). Further,

Coudounaris and Sthapit’ s (2017) three-item tourism-

Cronbach’s alpha value is in the acceptable range (0.-

based scale, with a sample item reading: “Visit this desti-

901–0.945) in accordance with the threshold; α greater

nation more in the next few years.” All the variables and

than 0.70 (Hair et al., 2010), verifying strong reliability.

measurement items are presented in Appendix A.

Constructs internal consistency is assessed due to values

of composite reliability (CR) that fall in the suggested

limit i.e. CR above 0.70 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Average Common method bias testing

variance extracted or AVE for each construct maintains

the convergent validity. The criterion value for AVE

Common method bias (CMB) may be problematic in

should be greater than 0.50 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981)

cross-sectional studies (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, &

(Table 2). Moreover, all the inter-construct correlations

Podsakoff, 2003). Thus, this study employed Podsakoff

are below 1, hence supporting the discriminant validity

et al.’s (2003) method to prove the presence of common

of the study (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Discriminant valid-

method bias in survey data. Firstly, the confidentiality

ity was further ascertained to compare the square root

and anonymity of participants were maintained.

value of AVE score of each factor/construct (Table 3) with

Secondly, CMB is unlikely if correlations are not very

inter-construct correlations (e.g. Hair et al., 2010).

high (below 0.9; Hair et al., 2010). In Table 3, correlation

Subsequently, this study generated a CFA model com-

matrix indicates that the lack of very high correlation

posed of six constructs with all the 29 indicators/items

values in survey data, thereby common method bias is

and the model attained a reasonable fit: χ2 = 252.84, df = not an issue in this study.

119, χ2/d. f. = 2.12, NFI = .94, CFI = .95, GFI = 0.91, and

RMSEA = .065, in line with criterion: NFI, CFI, TLI, GFI

greater than 0.90, and RMSEA less than 0.08 (Bentler & Analysis and results Bonnett, 1980). Measurement model

Data analysis was conducted by employing a two-stage

Structural model and hypothesis testing

structural equation modelling technique that is confir-

matory factor analysis or CFA followed by structural

Second, to perform the structural analysis, this study

equation modeling or SEM (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988).

adopted SEM using AMOS 20.0 software. Structural

Software AMOS 20.0 has been utilized to examine the

equation modeling approach facilitates the simulta- proposed relationships. First, confirmatory factor

neous estimation of relationships among various