Preview text:

INTRODUCTION 1 INTRODUCTION1

1.1 WHAT IS MORPHOLOGY?

The term morphology is generally attributed to the German poet, novelist, playwright,

and philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749 1832) – , who coined it early in the

nineteenth century in a biological context. Its etymology is Greek: morph- means ‗shape,

form‘, and morphology is the study of form or forms. In biology morphology refers to the study

of the form and structure of organisms, and in geology it refers to the study of the configuration

and evolution of land forms. In linguistics morphology refers to the mental system involved in

word formation or to the branch of linguistics that deals with w r

o ds, their internal structure, and how they are formed.

1.2 THE EMERGENCE OF MORPHOLOGY

Although students of language have always been aware of the importance of

words, morphology, the study of the internal structure of words did not emerge as a

distinct sub-branch of linguistics until the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, its

importance has always been assumed, as attest ed by its central role in Panini's

fourth-century BC grammar of Sanskrit, the Astadhyayi, for instance.

Early in the nineteenth century, morphology played a pivotal role in the

reconstruction of Indo-European. In 1816, Franz Bopp published the results of a

study supporting the claim, originally made by Sir William Jones in 1786, that

Sanskrit, Latin, Persian and the Germanic languages were descended from a common

ancestor. Bopp's evidence was based on a comparison of the grammatical endings of words in these languages.

Between 1819 and 1837, Bopp's contemporary, Jacob Grimm, published his

classic work, Deutsche Grammatik. By making a thorough analytical comparison of

sound systems and word-formation patterns, Grimm showed the evolution of the

grammar of Germanic languages and the relationships of Germanic to other Indo - European languages.

Later, under the influence of the Darwinian theory of evolution , the philologist

Max Muller contended, in his Oxford lectures of 1899, that the study of the evolution

1 The content of this part is adapted from Aronoff, M., & Fudeman, K. (2011). What is Morphology? (2nd Ed.) Wiley

Blackwell and Katamba, F., & Stoneham, J. (2006) Modern Linguistics: Morphology. Palgrave. 2 INTRODUCTION

of words would illuminate the evolution of language just as in biology, morphology,

the study of the forms of organisms, had thrown light on the evolution of species. His

specific claim was that the study of the 400 -500 basic roots of the Indo-European

ancestor of many of the languages of Europe and Asia was the key to understanding

the origin of human language (cf. Muller, 1899, cited in Matthews, 1974).

Such evolutionary pretensions were abandoned very early on in the history of

morphology. Since then morpholo gy has been regarded as an essentially synchronic

discipline, that is to say, a discipline focusing on the study of word -structure at one

stage in the life of a language rather than on the evolution of words. But, in spite of

the unanimous agreement among linguists on this point, morphology has had a

chequered career in twentieth-century linguistics, as we shall see.

1.3 MORPHOLOGY IN AMERICAN STRUCTURAL LINGUISTICS

Adherents to American structural linguistics, one of the dominant schools of

linguistics in the first part of the twentieth century, typically viewed linguistics not

so much as a 'theory' of the nature of language but rather as a body of descriptive and

analytical procedures. Ideally, linguistic analysis was expected to proceed by

focusing selectivel y on one dimension of language structure at a time before tackling

the next one. Each dimension was formally referred to as a linguistic level. The

various levels are shown in [1.1]. [1.1] Semantic level: deals with meaning Syntactic level: deals with sentence-structure Morphological level: deals with word-structure

Phonology (or phonemics): deals with sound systems

The levels were assumed to be ordered in a hierarchy, with phonology at the bottom and

semantics at the top. The task of the analyst producing a description of a language was seen as

one of working out, in separate stages, first the pronunciation, then the word-structure, then

the sentence-structure and finally the meaning of utterances. It was considered theoretically

reprehensible to make use of information from a higher level, for example, syntax, when

analysing a lower level such as phonology. This was the doctrine of separation of levels.

In the early days, especially between 1920 and 1945, American structuralists grappled

with the problem of how sounds are used to distinguish meaning in language. They built upon

nineteenth-century work, such as that of Dufriche-Desgenettes (Joseph, 1999) and Baudouin

de Courtenay (1895), and further developed and refined the theory of the phoneme (cf., Sapir,

1925; Swadesh, 1934; Twaddell, 1935; Harris, 1944).

As time went on, the focus gradually shifted to morphology. When structuralism was in

its prime, especially between 1940 and 1960, the study of morphology occupied centre stage.

Many major structuralists investigated issues in the theory of word-structure (cf. Bloomfield,

1933; Harris, 1942, 1946, 1951; Hockett, 1952, 1954, 1958). Nida's coursebook entitled

Morphology, published in 1949, codified structuralist theory and practice. It introduced

generations of linguists to the descriptive analysis of words. INTRODUCTION

The structuralists' methodological insistence on the separation of levels that we noted

above was a mistake […]. Despite this flaw, there was much that was commendable in the

structuralist approach to morphology. One of the structuralists' main contributions was the

recognition of the fact that words may have intricate internal structures. Whereas traditionally

linguistic analysis had treated the word as the basic unit of grammatical theory and

lexicography, the American structuralists showed that words are analysable in terms of

morpheme. These are the smallest units of meaning and/or grammatical function. Previously,

word-structure had been treated together with sentence-structure under grammar. The

structuralists viewed morphology as a separate sub-branch of linguistics. Its purpose was 'the

study of morphemes and their arrangements in forming words' (Nida, 1949: 1).

4 WHAT IS A WORD? 2 WHAT IS A WORD? 2

The assumption that languages contain words is t aken for granted by most

people. Even illiterate speakers know that there are words in their language. True,

sometimes there are differences of opinion as to what units are to be treated as words.

For instance, English speakers might not agree whether all right is one word or two

and as a result disputes may arise as to whether alright is the correct way of writing all

right. But, by and large, people can easily recognise a word of their language when

they see or hear one. And normally their judgements as t o what is or is not a word do

coincide. English speakers agree, for example, that the form stlody in the sentence The

stlody cat sat on the mat is not an English word - but all the other forms are. 2.1 THE LEXEME

However, closer examination of the nature of the 'word' reveals a somewhat

more complex picture than painted above. What we mean by 'word' is not always

clear. As we shall see in the next few paragraphs, difficulties in clarifying the nature

of the word are largely due to the fact that the term 'word' is used in a variety of

senses that usually are not clearly distinguished. In taking the existence of words for

granted, we tend to overlook the complexity of what it is we are taking for granted. Exercise 1

What would you do if you were reading a book and you encountered the

'word' pockled for the first time in this context?

He went to the pub for a pint and then pockled off.

You would probably look up that unfamiliar word in a dictionary, not under

pockled, but under pockle. This is because you know that pockled is not going to be

listed in the dictionary. You also know, though nobody has told you, that the words

pockling and pockles will also exist. Furthermore, you know that pockling, pockle, pockle s

and pockled are all in a sense different manifestations of the 'same' abstract vocabulary item.

2 The content of this part is adapted from Fromkin, V. A. (ed.) (2000) Linguistics: An Introduction to Linguistic Theory.

Oxford: Blackwell; Katamba, F., & Stoneham, J. (2006) Modern Linguistics: Morphology. Palgrave and Kuiper, K., &

W. S. Allan (1996) An Introduction to English Language: Sound, Word and Sentence. London: MacMillan. WHAT IS A WORD?

We shall refer to the 'word' in this sense of abstract vocabulary item using the

term lexeme. The forms pockling. pockle, pockle

s and pockled are different realisations

(or representations or manifestations) of the lexeme POCKLE (lexemes will be written

in capital letters). They all share 3 core meaning although they are spelled and

pronounced differently. Lexemes are the vocabulary items that are listed in the

dictionary (cf. Di Sciullo and Williams, 1987). Exercise 2

Which ones of the words below belong to the same lexeme? see catches taller boy catching sees sleeps woman catch saw tallest sleeping boys sleep seen tall jumped caught seeing jump women slept jumps jumping 2.2 WORD-FORM

As we have just seen above, sometimes, when we use the term 'word', it is not

the abstract vocabulary item with a common core of meaning, the lexeme, that we

want to refer to. Rather, we may use the term 'word' to refer to a particular physical

realisation of that lexeme in speech or writing that is, a particular word-form. Thus,

we can refer to see, sees, seeing, saw and seen as five different words. In this sense,

three different occurrences of any one of these word -forms would count as three

words. We can also say that the word-form see has three letters and the word-form

seeing has six. And, if we were counting the number of words in a passage, we would

gladly count see, sees, seeing, saw and seen as five different word-forms (belonging to the same lexeme).

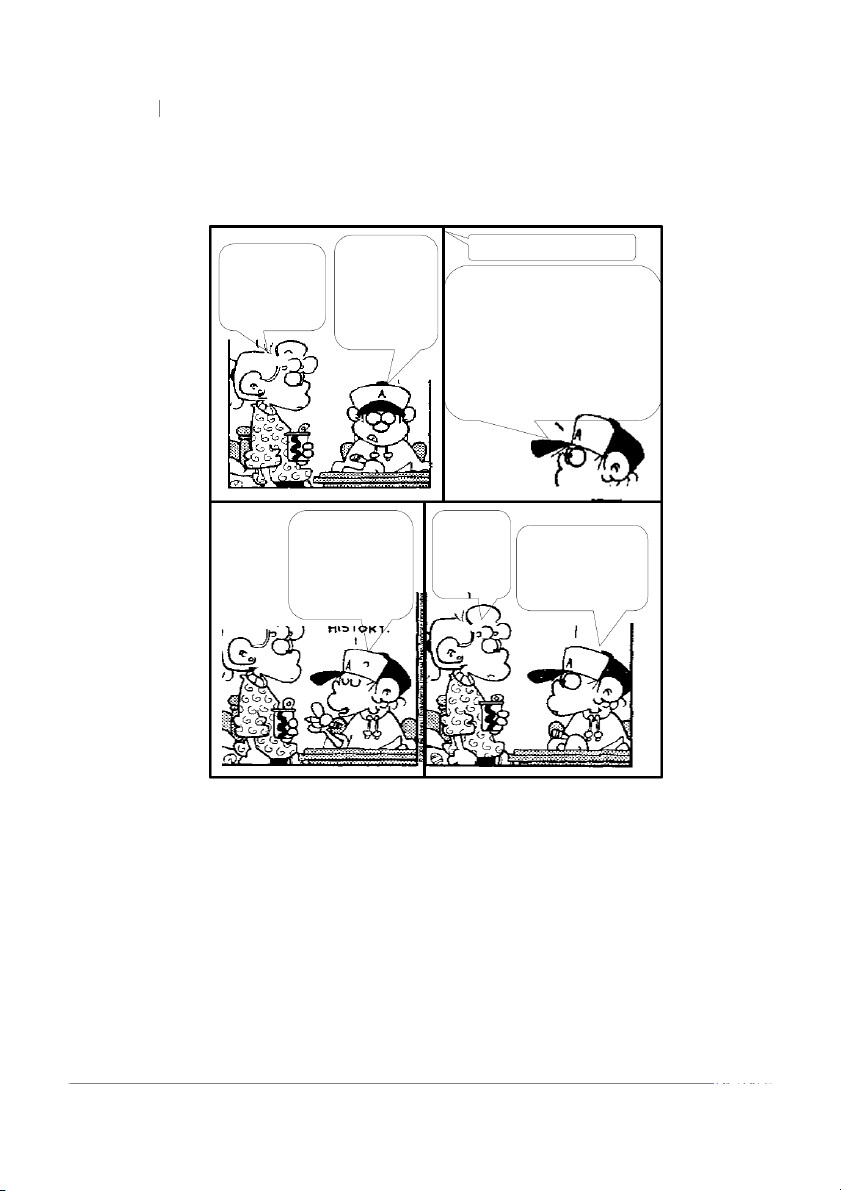

2.3 CONTTENT WORDS AND FUNCTION WORDS

Languages make an important distinction between two kinds of words —content words

and function words. Nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs are the content words. These words

denote concepts such as objects, actions, attributes, and ideas that we can think about like

children, anarchism, soar, and purple. Content words are sometimes called the open class

words because we can and regularly do add new words to these classes. A new word,

steganography, which is the art of hiding information in electronic text, entered English with

the Internet revolution. Verbs like disrespect and download entered the language quite

recently, as have nouns like byte and email.

Different languages may express the same concept using words of different grammatical

classes. For example, in Akan, the major language of Ghana, there are only a handful of

adjectives. Most concepts that would be expressed with adjectives in English are expressed by

verbs in Akan. Instead of saying "The sun is bright today," an Akan speaker will say "The sun brightens today."

There are other classes of words that do not have clear lexical meaning or obvious

concepts associated with them, including conjunctions such as and, or, and but; prepositions

such as in and of; the articles the, a/an, and pronouns such as it and he. These kinds of words

are called function words because they have a grammatical function. For example, the articles

6 WHAT IS A WORD?

indicate whether a noun is definite or indefinite — the boy or

a boy. The preposition of

indicates possession as in "the book of yours," but this word indicates many other kinds of relations too. What do you mean? Ho H w o ’ w s ’ s y o y u o r u r 5 0 5 0 0 - We W l e ll,l ,b a b s a e s d e d o n o n wo w r o d r d h i h s i t s o t r o y r y pa p s a t s tp e p r e f r o f r o m r a m n a c n

I know I’ll use “the” about 25 tim pa p p a e p r e r c o c m o i m n i g n ? g ? I’ I m ’ m r e r a e d a y d y a a

“and” at least 15. “in”, “if”,”it” a qu q a u r a t r e t r e r d o d n o e n . e .

“but” should give me another 30-

Toss in the usual “is”, “was”, “wi

verb assortment and I’m sitting

comfortably at 120-plus words be I even start. Th T e h e k e k y e y t o t o w r w i r tiitn i g n g Yo Y u o u ne n v e e v r e r a a h i h s i t s o t r o y r y e s e s s a s y a y i s i s fa f i a li l to t o Th T a h n a k n s k . s .Wh o Wh ' o d d w e w e kn k o n w o i w n i g n g y o y u o r u r am a a m z a e z e m e m . e . fi f g i h g t h ti n i n W o W r o l r d l d W a W r a r I , I , es e s s a s y a y h i h s i t s o t r o y r . y . by b y t h t e h e w a w y a ? y ?

"Fox Trot" copyright © 2000 Bill Amend. Reprinted with permission of Universal Press Syndicate. All rights reserved.

Function words are sometimes called closed class words. It is difficult to think of new

conjunctions, prepositions, or pronouns that have recently entered the language. The small set

of personal pronouns such as I, me, mine, he, she, and so on are part of this class.

[…]These two classes of words have different functions in language. Content words

have semantic content (meaning). Function words play a grammatical role; they connect the

content words to the larger grammatical context. WHAT IS A WORD?

2.4 WORDS AND THEIR GRAMMATICAL CATEGORIES

[…] In a dictionary the words of a language are classified by grammatical

category. In this section we will look at grammatical cate gories and how words may

be assigned to particular categories. The reason for examining this property of words

first is that the later section in this chapter, where we look at the internal structure of

words, depends on being able to identify a word's grammatical category.

[…] Before looking at the specific grammatical categories of English lex emes we

need to look in a little more detail at the way they change their form. Look, for

example, at the lexeme TRY. Depending on how it is functioning it can take any of the

following forms: try, tries, tried, trying, as in the following sentences: The horse must try,

The horse tries, The horse tried, The horse is trying. We can call each of these forms a

grammatical word form of the lexeme, since it is the grammar of English which

requires the lexeme TRY to have these different forms in different syntactic contexts.

The grammatical endings which create these different grammatical word forms are

termed inflections. The form of the lexeme to which they are attached is termed the

. The processes whereby words come to have internal structure such as a stem

and inflection are morphological processes, the morp hology of words having to do

with their internal structure. Since inflections are associated with both the

morphological structure of words and the syntactic functions of words, the categories

for which words inflect are often called morphosyntactic catego ries. Tense, which

accounts for the past-tense inflection -ed in tri-ed, is an example of a morphosyntactic

category. Properties such as present tense or past tense are therefore morphosyntactic properties.

The categories which we will look at in this sect ion are four major lexical

categories: nouns, adjectives, verbs and adverbs. We will be looking at the

morphosyntactic categories for which they inflect. At the section‘s conclusion we

will briefly look at prepositions, although these do not have any chara cteristic grammatical endings. 2.4.1 Nouns

Traditionally, a noun is a naming word; typically the name of a pers on place, or

thing. For example, snake, rat, alligator, Fred, chainsaw, lawnmower are all nouns.

For each of the above words we can find a set of objec ts to which the word is

normally used to refer (although the name of a partic ular snake, rat, or alligator may

be Fred or Freda for those with whom the animal is on intimate terms). Exercise 3

Consider the following nouns. Do they pose any problems for our definition of a noun?

anger, fame, cyclops, Zeus, Hamlet, Lilliput, furniture

It is impossible to point to an object in the physical world to which these words

refer. Anger is a feeling and fame is an abstract quality; cyclops, and Zeus are both

mythical beings; Hamlet is a fictional character, whi le Lilliput is a fictitious place.

8 WHAT IS A WORD?

Furniture is not a person or a place or a thi ng either, or even a set of objects. In fact it

isn't any particular thing but class of things. Unlike alligators, where we can say of a

particular alligator, ‗That's an alligator,‘ we cannot say when pointing to a chair,

'That's a furniture.' So although their meaning may be useful in identifying some

nouns, we must look elsewhere for some supporting facts about nouns if we are to

become more familiar with them and be able to tell whethe r a particular word is a

noun. To do that we will look at the inflections whic h nouns characteristically take.

Most nouns inflect for the morphosyntactic category of number and, as such,

have a plural form like -s or -es. For example: snapper snappers bee bees rosella rosellas box boxes

Some nouns mark their plural in other ways, for exampl e: foot feet mouse mice louse lice child children ox oxen

Other nouns never mark their plurals overtly: sheep sheep deer deer

while some nouns never occur without the plural marker, for example scissors and

trousers. These are facts about the form of nouns. If a word has plural form, then it

belongs to the category

noun. (Note that the reverse does not follow: namely, that if a

word has no plural form then it is not a noun.)

Notice that although words like sheep and deer do not take an ending to indicate

that they are plural, they do have a plural form. It happens to be identical to their

singular form. On the basis of this we can see the necessity to make a distinction

between a lexeme and a grammatical word. There are two grammatical words with the

word form sheep. One is the singular form of the lexeme SHEEP and the other the

plural form. So SHEEP is a noun because it has a plural form.

We can also identify nouns by looking at the words that typically appear with

them in a sentence or phrase. Most nouns appear with either a(n) or the, or refer to

things that can be counted, for example: a wombat the wombat three wombats a barbecue the barbecue one barbecue […] WHAT IS A WORD?

2.4.2 Adjectives

Traditionally adjectives ascribe a property or quality to an object, for example: the ripe apple the evil alligator

Adjectives may take two different endings, giving three forms, for example: big bigger biggest tall taller tallest

The adjective without the ending is called the standard form and repre sents the

positive degree of comparison. The one with the -e

r ending is the comparative, and is

used when we compare two objects for the same property. For example:

My dad is taller than your dad.

The -est ending is called the superlative (literally: raised above), and is

superlative used when we are comparing three or more objects for the same prop erty. For example:

Your dad may be taller than my dad but Raewyn's dad is the tallest.

Not all adjectives take the -e

r and -est endings; some use more and most. For example: evil more evil most evil incredible more incredible most incredible

The morphosyntactic category which has the morphosyntactic prop erties of

comparative and superlative is called comparison. The unmarked form of the adjective

shows the positive morphosyntactic property of this category. In other words,

adjectives which show comparison show it in three forms: the simple positive form,

the comparative form, and the superlative form. Exercise 4

Co nsi de r th e f oll owi n g li st of ad je cti ves , an d d iv id e t hem i nt o thr ee

gro ups : tho se w hi ch tak e t he -e

r and — est en di ng s, tho se wh ic h t ak e

more an d most, an d t h ose w hi ch tak e nei th er o f th e ab ov e.

hig h, wi de, d ead , red , med ica l, u gl y, nar r ow, ab sol ut e, pa in ful , fin al

Those adjectives that have comparative and superlative fo rms are called

gradable, while those that do not are called non-gradable. What we mean by gradable

is that there are degrees of the particular property rather than just the presence or

absence of it. A medical bill cannot be more or less medical, at least as far as the

English language is concerned.

As to their function, English adjectives may appear either bef ore a noun or after

a form of the verb to be (am, is, are, was, were, being or been), for example:

10 WHAT IS A WORD? the ripe apple the apple is ripe the evil alligator the alligator is evil

Not all adjectives may appear in both of these positions. Some may only appear

before nouns, while others may only appear after a form of the verb to be. Exercise 5

Consider the following list of adjectives. Which may appear only before a noun,

which may appear only after the verb to be, and which may appear in both positions?

older, elder, hungry, ill, red, ugly, afraid, utter, incredible, loath. Exercise 6

Below is a portion of a short story with its adjectives in itali cs. What

would the description be like without the adjectives?

His name described him better than I can. He looked like a great,

stupid, smiling bear. His black matted head bobbed forward and his long

arms hung out as though he should have been on all fours and was

only standing upright as a trick. His legs were short and bowed, ending

in strange, square feet. He was dressed in dark blue denim, but his feet

were bare; they didn't seem to be crippled or deformed in any way, but

they were square, just as wide as they were long.

(John Steinbeck, ‗Johnny Bear‘)

If you remove the adjectives which come after forms of to be, the sentences

become ungrammatical. When you remove all the adjectives which come before

nouns, as well, there is virtually no description left. 2.4.3 Verbs

The grammatical class of verbs may be divided into two groups - lexical verbs

and auxiliary verbs. The class of auxiliaries is quite small, and contains the

following: has, had, have, be, is, are, was, were, do, does, did, can, could, shall, should, will,

would, may, might, and must. […] In this section we will concentrate on the class of lexical verbs.

Traditionally verbs are defined as denoting actions or states, for example eat,

drink, run, speak, forgive, understand, hate. The first four of these verbs denote actions,

that is, in doing these things we perfo rm some physical action, while the final three

denote states, that is, we can 'do' these things without performing any physical action.

English verb lexemes have more grammatical words associated with them than

either nouns or adjectives. Each verb lexeme has five as sociated grammatical words. WHAT IS A WORD?

The changes in form associated with each grammatical word, listed below, are often

brought about by adding an inflection to the verb. V V-s V-ed V-ing V-en call calls called calling called

Let us look at the morphosyntactic categories that give rise to these different

grammatical words and word forms. The first category is tense All English verbs can

take tense and there are two tenses: past and present. The present tense form of CALL

is call and the past tense form is called. You may ask what happens to the future in

English. The future is not indicated by a word form but can be indicated by other

means, such as the auxiliary verb will as in will call.

The next inflected form, the one ending in -s, indicates a number of

morphosyntactic categories. It is found only if the verb to which it is attached is in

the present tense, the noun in front of it in a sim ple two-word sentence must be

singular and can be substituted for by he, she, or it, for example:

he, she, it, the postman, Mary/calls in the mornin g.

Such nouns are in what is termed the third person: not the speaker, who is the

first person, or the person being addressed, the second person, but the person or

thing spoken about, the third person. So here we have an inflection which indicates

the state of not one morphosyntactic category but three: tense, number and person.

The V-ing and V-en forms are called participles. The V-ing form is the

progressive participle and the V—en form is called the perfect participle. […] The

simple form of verbs without any endings is called the infinitive. It is often

introduced by the word to, for example, to call.

Verbs like call are regular, and regular verbs form the majority of verbs in

English. For regular verbs the past tense form and the perfect participle form are

identical. So how can we tell that these identical forms represent different

grammatical words? In part because they have different functions in phrases and

sentences, but also because, in the case of irregular verbs, the forms are different.

There are about 200 irregular verbs: V-stem V-s V-ed V-ing V-en meet meets met meeting Met put puts put putting Put write writes wrote writing written bring brings brought bringing brought […]

We can now note that not all changes of word form are by way of in flection,

that is the addition of an ending. Some morphosyntactic categories are realised in

particular lexemes by changes to the stem of the lexeme.

12 WHAT IS A WORD? 2.4.4 Adverbs

The class of adverbs may be divided into two groups: degree, and general

adverbs. Degree adverbs are a small group of words like very, more, and most. They

must always appear with either an adjective or a general adverb, for example: She runs very quickly. *She runs very.

This sculpture is more beautiful. *This sculpture is more.

General adverbs are a large class, and may appear without a degree adverb. For example: She runs quickly.

Traditionally, adverbs tell us how (manner), where (place), or when (time) the action

denoted by a verb occurs. For example: She runs quickly. How The cat sat here. Where They left yesterday. When

Adverbs have no inflected forms, although they do take comparison like adjectives,

but by using the more and most forms, for example more quickly, most quickly.

Many of adverbs end with -ly, for example quickly, quietly, properly, instantly, seemingly, stupidly.

The sharp-eyed reader will notice that the -ly ending which forms adverbs is

attached to adjectives. It is not an inflection since it does not relate to any

morphosyntactic categories such as tense or number. We s hall have more to say about

such word-forming endings in the next section.

2.4.5 Prepositions

The last major syntactic category we will look at in this chapter is preposi tion.

Prepositions are words such as in, out, on, by, which often indicate locations in tim e or space, or direction.

While nouns, adjectives, verbs, and adverbs are members of open classes

because the classes they belong to are very large, and while it is possible to add new

items to any one of these open classes, prepositions are members of a c losed class.

Other closed classes of words are conjunctions, for example and, but, because, or,

determiners, for example a, an, the, these, those; and the class of auxiliary verbs we

looked at earlier in this chapter. It is not possible to add new member s to the closed

classes. In fact, there is no record of anyone ever adding a new conjunc tion to the

language. Because the function of these words requires us to look more closely at the

grammar of sentences we will leave discussing them until Part II, whe re we look at sentence structure. MORPHEMES 3 MORPHEMES 3

3.1 MORPHEMES: THE SMALLEST UNITS OF MEANING

Morphology is the study of word-structure. The claim that words have structure

might come as a surprise because normally speakers think o f words as indivisible

units of meaning. This is probably due to the fact that many words are

morphologically simple. For example, the, fierce, elephant, eat, boot, at, fee, mosquito,

etc., cannot be segmented (i.e., divided up) into smaller units that are themselves

meaningful. It is impossible to say what the -quito part of mosquito or the -erce part of fierce means.

But very many English words are morphologically complex. They can be broken

down into smaller units that are meaningful. This is true of words like desk-s and boot-

s, for instance, where desk refers to one piece of furniture and boot refers to one item

of footwear, while in both cases the -s serves the grammatical function of indicating plurality.

The term morpheme is used to refer to the smallest, indivisible units o f semantic

content or grammatical function from which words are made up. By definition, a

morpheme cannot be decomposed into smaller units which are either meaningful by

themselves or mark a grammatical function like singular or plural number in the

noun. If we divided up the word fee [fi:] (which contains just one morpheme) into, say,

[f] and [i:], it would be impossible to say what each of the sounds [f] and [i:] means

by itself, since sounds in themselves do not have meaning.

How do we know when to recognise a single sound or a group of sounds as

representing a morpheme? Whether a particular sound or string of sounds is to be

regarded as a manifestation of a morpheme depends on the word in which it appears.

So, while un- represents a negative morpheme and has a meaning that can roughly be

glossed as 'not' in words such as un-just and un-tidy, it has no claim to morpheme

status when it occurs in uncle or in under, since in these latter words it does not have

any identifiable grammatical or semantic value, because -cle and -der on their own do

not mean anything. (Morphemes will be separated with a hyphen in the examples.)

Lego provides a useful analogy: morphemes can be compared to pieces of Lego

that can be used again and again as building blocks to form di fferent words.

Recurrent parts of words that have the same meaning are isolated and recognised as

manifestations of the same morpheme. Thus, the negative morpheme un- occurs in an

3 The content of this part is adapted from Aronoff, M., & Fudeman, K. (2011). What is Morphology? (2nd Ed.) Wiley

Blackwell; Fromkin, V. A. (ed.) (2000) Linguistics: An Introduction to Linguistic Theory. Oxford: Blackwell; and

Katamba, F., & Stoneham, J. (2006) Modern Linguistics: Morphology. Palgrave 14 MORPHEMES

indefinitely large number of words, besides those listed above. We find it i n unsafe,

unclean, unhappy, unfit, uneven, etc.

However, recurrence in a large number of words is not an essential property of

morphemes. Sometimes a morpheme may be restricted to rela tively few words. This is

true of the morpheme -dom, meaning 'condition, state, dignity', which is found in

words like martyrdom, kingdom, chiefdom, etc. (Glosses, here and elsewhere in the

book, are based on definitions in the Oxford English Dictionary OED.)

It has been argued that, in an extreme case, a morpheme may occur i n a single

word. Lightner (1975) has claimed that the morpheme -ric meaning 'diocese' is only

found in the word bishopric. But this claim is disputed by Bauer (1983) who suggests

instead that perhaps -ric is not a distinct morpheme and that bishopric should be listed

in the dictionary as an unanalysable word. We will leave this controversy at that and

instead see how morphemes are identified in less problematic cases. Exercise 7

List two other words that contain each morpheme represented below. a. -er as in play-er, call-er

-ness as in kind-ness, good-ness b. e - x as in ex-wife, ex-minister

pre- as in pre-war, pre-school

mis- as in mis-kick, mis-judge (i)

Write down the meaning of each morpheme you identify. (If you are in doubt,

consult a good etymological dictionary.)

(ii) What is the syntactic category (noun, adjective, verb, etc.) of the form which

this morpheme attaches to and what is the category of the resulting word?

Your answer should confirm that, in each example in exercise 7, the elements

recognised as belonging to a given morpheme contribute an identifiable meaning to

the word of which they are a part. The form -e

r is attached to verbs to derive nouns

with the general meaning 'someone who does X' (where X indicates whatever action

the verb involves). When -ness is added to an adjective, it produces a noun meaning

'having the state or condition (e.g., of being kind)'. […]

. Finally, the morphemes ex-

and pre- derive nouns from nouns while mis- derives verbs from verbs. We can gloss

the morpheme ex- as 'former', pre- as 'before' and mis- as 'badly'.

So far we have described words with just one or two morphemes. In fact, it is possible to

combine several morphemes together to form more complex words. This can be seen in long

words like unfaithfulness and reincarnation, which contain the morphemes un-faith-ful-ness

and re-in-carn-at-ion respectively. […] MORPHEMES

3.2 MORPHEMES, MORPHS AND ALLOMORPHS

The morpheme is the smallest difference in the shape of a word that correlates with the

smallest difference in word or sentence meaning or in grammatical structure.

The analysis of words into morphemes begins with the isolation of morphs. A morph is a

physical form representing some morpheme in a language. It is a recurrent distinctive sound

(phoneme) or sequence of sounds (phonemes) Exercise 8

Study the data in the following sentences and identify the morphs. 8a. I parked the car. 8b. We parked the car. 8c. I park the car. 8d. He parks the car. 8e. She parked the car. 8f. She parks the car. 8g. We park the car. 8h. He parked the car.

The answer to exercise 8 is given below Morph Recurs in ‗I‘ 8a and 8c ‗she‘ 8e and 8f ‗he‘ 8d and 8h ‗the‘ in all the examples ‗car‘ in all the examples ‗park‘

in all the examples, sometimes with an –ed suffix,

sometimes with an –s suffix and sometimes on its own ‗-ed‘

suffixed to park in 8a, 8b, 8e, 8h ‗-s‘ suffixed to park in 8d, 8f

[..] Each different morph represents a separate morpheme, but this is not

always the case. Sometimes different morphs may represent the same morpheme.

For instance, the past tense of regular verbs in English which is spelled -e d is realised in speech by /

/, /d/ or /t/. The phonological properties of the last segment

of the verb to which it is attached determine the choice: [3.1] It is realised as:

a. / d/ if the verb ends in /d/ or /t/ e.g. 'mend' /mend/ 'mended' / /

'paint' /pe nt/ 'painted' /pe nt d/

b. /d/ after a verb ending in any voiced sound except /d/

e.g. 'clean' /kli:n/ 'cleaned' /kli:nd/ 'weigh'/we / 'weighed' / /

c. /t/ after a verb ending in any voiceless consonant other than /t/

e.g. 'park' /pa:k/ 'parked' /pa:kt/ 'miss'/ / 'missed' / / 16 MORPHEMES

If different morphs represent the same morpheme, they ar e grouped together and

they are called allomorphs of that morpheme So,/ d/, /d/ and /t/- are grouped together

as allomorphs of the past tense morpheme in English.

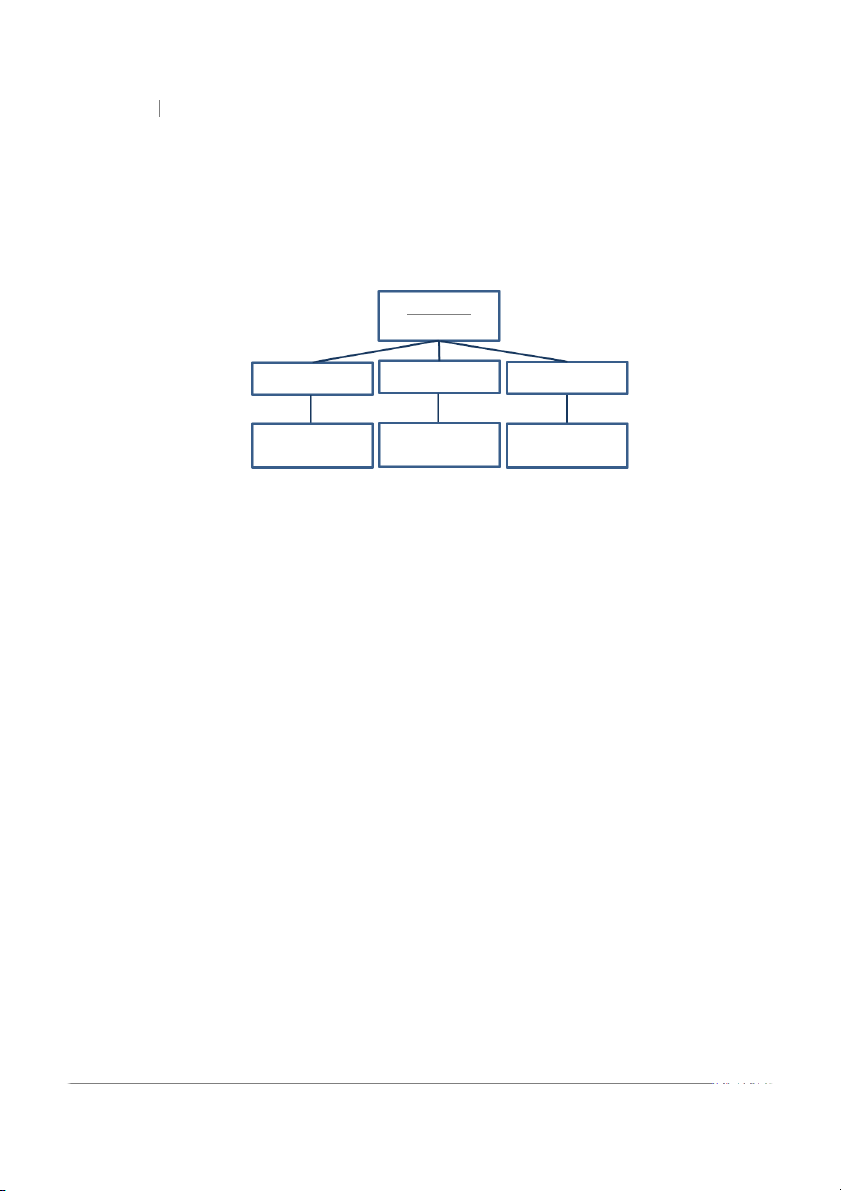

The relationship between morphemes, allomorphs and morphs can be

represented using a diagram in the following way: e.g. Morpheme ―past tense” Allomorph Allomorph Allomorph morph morph morph / d/ /d/ /t/

We can say that: (1) / d/, /d/ and /t/ are English morphs; and (2) we can group

all these three morphs together as allomorphs of the past tense morpheme.

The central technique used in the identification of morphemes is based on the

notion of distribution, that is, the total set of contexts in which a particular linguistic

form occurs. We classify a set of morphs as allomorphs of the same morpheme if they

are in complementary distribution. Morphs are said to be in complementary

distribution if: (1) they represent the same meaning or serve the same grammatical

function; and (2) they are never found in identical contexts. So, the three morphs /- d/,

/-d/ and /-t/ which represent the English regular past tense morpheme are in

complementary distribution. Each morph is restricted to the contexts specified in

[3.1]. Hence, they are allomorphs of the same morpheme.

3.3 TYPES OF MORPHEMES

3.3.1 Roots and Stems

Morphologically complex words consist of a root and one or more affixes. A root is a lexical

content morpheme that cannot be analyzed into smaller parts. Some examples of English roots

are paint in painter, read in reread, and ceive in conceive. A root may or may not stand alone

as a word (paint does; ceive doesn't).

A stem is a base unit to which another morphological piece is attached. The stem can be

simple, made up of only one part, or complex, itself made up of more than one piece.

Now consider the word reconsideration. We can break it into three morphemes: re-, consider,

and -ation. Consider is called the stem. H r

e e it is best to consider consider a simple stem.

Although it consists historically of more than one part, most present-day speakers would treat

it as an unanalyzable form. We could also call consider the root. A root is like a stem in MORPHEMES

constituting the core of the word to which other pieces attach, but the term refers only to

morphologically simple units. For example, disagree is the stem of disagreement, because it

is the base to which -ment attaches, but agree is the root. Taking disagree now, agree is both the

stem to which dis- attaches and the root of the entire word.

3.3.2 Free and Bound Morphemes

Our morphological knowledge has two components: knowledge of the individual

morphemes and knowledge of the rules that combine them. One of the things we

know about particular morphemes is whether they can stand alone or whether they

must be attached to a host morpheme.

“L OO KS LIK E WE SPEND MOST OF OUR T

INGING. YOU KNOW, LIKE SLEEPING, EATING, RUNNING, CLIMBING”

"Dennis the Menace" ® copyright © 1987 by North America Syndicate. Used

by permission of Hank Ketchum.

Some morphemes like boy, desire, gentle, and man may constitute words by them-

selves. These are free morphemes. Other morphemes like -ish, -ness, -ly, dis-, trans-,and

un- are never words by themselves but are always parts of words. These affixes are

bound morphemes. We know whether each affix precedes or follows other mor-

phemes. Thus, un-, pre- (premeditate, prejudge), and bi- (bipolar, bisexual) are prefixes.

They occur before ether morphemes. Some morphemes occur only as suffixes,

following other morphemes. English examp les of suffix morphemes are -ing (e.g.,

sleeping, eating, running, climbing), -er (e.g., singer, performer, reader, and beautifier), -ist

(e.g., typist, copyist, pianist, novelist, collaborationist, and linguist), and -ly (e.g., manly,

sickly, spectacularly, and friendly), to mention only a few. 18 MORPHEMES

3.3.3 Inflectional and Derivational Morphemes

[…] Morphemes can be divided into two major functional categories, namely

derivational morphemes and inflectional morphemes. This reflects a recognition of

two principal word-building processes: inflection and derivation. While all

morphologists accept this distinction in some form, it is nevertheless one of the most

contentious issues in morphological theory. We will briefly introduce you here to the

essentials of this distinction.[…]

3.3.3.1 Derivational Morphemes

Inflectional and derivational morphemes form words in different ways.

Derivational morphemes form new words either:

(i) by changing the meaning of the base (or stem) to which they are attached, for

example, kind vs un-kind (both are adjectives but with opposite mean ings); obey vs

dis-obey (both are verbs but with opposite meanings). Or:

(ii) by changing the word-class that a base (or stem) belongs to, for example, the

addition of -ly to the adjectives kind and simple produces the adverbs kind-ly and

simp-ly. As a rule, it is possible to derive an adverb by adding the suffix -ly to an adjectival base (or stem).

[…] Sometimes the presence of a derivational affix causes a major grammatical

change, involving moving the stem from one word-class into another, as in the case

of -less which turns a noun into an adjective. In other cases, the change caused by a

derivational suffix may be minor. It may merely shift a stem to a different subclass

within the same broader word-class. That is what happens when the suffix -ling is

attached to duck above.

Further examples are given below. In [3.2a], the diminutive suffix -let is attached

to nouns to form diminutive nouns (meaning a 'small something'). In [3.2b], the

derivational suffix -shi

p is used to change a concrete noun stem into an abstract noun (meaning 'state, condition'): [3.2] a. pig ~ pig-let b. friend ~ friend-ship book ~ book-let leader ~ leader-ship

The tables in [3.3] and [3.4] list some common derivational prefixes and

suffixes, the classes of the stems to which they can be attached and the words that are

thereby formed. It will be obvious that in order to determine which morpheme a

particular affix morph belongs to, it is often essential to know the s tem to which it

attaches because the same phonological form may repre sent different morphemes

depending on the stem with which it co-occurs.

Note: These abbreviations are used in the tables below: N for noun, N (abs) for

abstract noun, N (conc) for concrete noun, V for verb, Adj for adjective, and Adv for adverb. MORPHEMES [3.3] Prefix Word-class of Meaning Word-class of Example input stem output word in- Adj ―not‖ Adj in-accurate un- Adj ―not‖ Adj un-kind un- V ―reversive‖ V un-tie dis- V ―reversive‖ V dis-continue dis- N(abs) ―not‖ N (abs) dis-order dis- Adj ―not‖ Adj dis-honest dis- V ―not‖ V dis-approve re- V ―again‖ V re-write ex- N ―former‖ N ex-mayor en- N ―put in‖ V en-cage [3.4] Suffix Word-class Meaning Word-class of Example of input stem output word -hood N ―status‖ N (abs) child-hood -ship N ―state or condition‖ N (abs) king-ship -ness Adj

―quality, state or condition‖ N (abs) kind-ness -ity Adj ―state or condition‖ N (abs) sincer-ity -ment V

Result or product of doing the N govern-ment

action indicated by the verb‖ -less N ―without‖ Adj power-less -ful N ―having‖ Adj power-ful -ic N ―pertaining to‖ Adj democrat-ic -al N

―pertaining to, of the kind‖ Adj medicin-al -al V ―pertaining to or act of‖ N (abs) refus-al -er V ―agent who does whatever N read-er the verb indicate‖ -ly Adj ―manner‖ Adv kind-ly 20 MORPHEMES

To sum up the discussion so far, we have observed that derivational affixes are

used to create new lexemes by either: (i) modifying significantly the meaning of the

stem to which they are attached, without necessarily changing its grammatical

category (see kind and unkind above); or (ii) they bring about a shift in the grammatical

class of a stem as well as a possible change in meaning (as in the case of hard (Adj)

and hardship (N (abs)); or (iii) they may cause a shift in the grammatical subclass of a

word without moving it into a new word-class (as in the case of friend (N (conc)) and friend-ship (N (abs)). Exercise 9

Study the data below that contain the derivational prefix en- a. Stem New word b. Stem New word cage en-cage noble en-noble large en-large rich en-rich robe en-robe rage en-rage danger en-danger able en-able

(i) State the word-classes (e.g., noun, adjective, verb, etc.) of the stem to which en- is prefixed.

(ii) What is the word-class of the new word resulting from the prefixation of en- in each case?

(iii) What is the meaning (or meanings) of en- in these words?

Consult a good dictionary, if you are not sure.

You will have established that the new word resulting from the prefixation of en-

in exercise 9 is a verb. But there is a difference in the input stem. Sometimes en- is

attached to adjectives as seen in [3.5a], and sometimes to nouns, as in [3.5b]: [3.5] a. Adj stem New Verb b. Noun stem New Verb able en-able robe en-robe large en-large danger en-danger noble en-noble rage en-rage rich en-rich cage en-cage

Interestingly, this formal difference correlates with a semantic distinction. So,

we conclude that there are two different prefixes here which happen to be

homophonous. The en- in [3.5a] has a causative meaning (similar to make'). To enable

is to 'make able', to enlarge is to 'make large', etc., while in [3.5b] en- can be

paraphrased as 'put in or into'. To -encage is to 'put in a cage' and to endanger is to 'put

in danger' etc. (Notice the very special nature of en- in these cases - unlike most

prefixes in English, which never affect the class of the form to which they attach, en-

may change the class from adjective (e.g., large) or noun (e.g., cage) to verb.)