Preview text:

Applied Thermal Engineering 248 (2024) 123146

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Applied Thermal Engineering

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ate Research Paper

Pin fin-PCM composite heat sink solution for thermal management of cylindrical Li-ion battery

Rajesh Akula, Abhiram Minnikanti, C. Balaji ∗,1

Heat Transfer and Thermal Power Laboratory, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Madras (IIT Madras), Chennai 600036, India A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Keywords:

Phase Change Material (PCM) based heat sink is a state-of-the-art cooling technique for the effective thermal Phase change material

management of Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs). The low thermal conductivity of PCMs (<0.5 W∕m K) adversely Pin fins

affects their cooling performance. Fins are the most commonly used structures in augmentation with PCMs to Battery thermal management

enhance their effective thermal conductivity. All the studies on the thermal management of LIBs using PCM-fin Passive cooling

composites are confined to plate fins. Pin fins are very popular in electronic cooling and latent heat thermal Li-ion battery

energy storage, as they distribute heat uniformly into the PCM. In consideration of the above, the present study Electric vehicles Enthalpy-porosity approach

introduces pin fins into the thermal management of 18650 LIBs. Initially, the temperature regulation capability

of the paraffin based heat sinks with plate and pin fins, which have the same volume fraction of 2.4%, are

numerically investigated using commercially available ANSYS Fluent software. Preliminary results confirmed

that the pin fins outperform plate fins by recording a 3.3 ◦C lower average battery surface temperature for

a 5C discharge rate. The thermal performance of the pin fins is further investigated numerically for various

pin fin numbers (130, 200, 260, and 390), pin fin sizes (1, 1.4, 2, 3, 3.5, and 4 mm), heat loads (3, 4, and

5C discharges), ambient conditions (15, 25, and 35 ◦C), and PCMs (Eicosane, Paraffin wax, and Tetracosane).

Among multiple pin fin-based heat sink configurations, a heat sink with 260 pin fins of side 1 mm is observed

to be the best heat sink from all the above characterizations considered. The numerical results of the pin fin

heat sink with 260 fins are further validated against in-house experiments within a 5% discrepancy. Finally,

an attempt also has been made to implement this best heat sink for thermal regulation of actual Panasonic

NCR18650BD battery with variable heat generation and proved its effectiveness in thermal management. 1. Introduction

reduces the life span, and sometimes may leads to thermal runaway.

In addition, the cost of battery packs holds a major share in the cost

Global climate change and air pollution have been a cause of

of any EV. Therefore, it is important to focus on an effective ther-

concern in recent years. The Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicles

mal management system that keeps the battery under safe operating

have been replaced with Electric Vehicles (EV) and Hybrid Electric temperatures [6].

Vehicles (HEV) to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and dependence on

Various thermal management techniques proposed in the literature

fossil fuels [1]. The HEVs/EVs are powered by hundreds of Lithium-

can be categorized into active and passive groups. In active cool-

ion batteries (LIBs) connected in series or parallel [2]. The vivid

implication of LIBs in EVs/HEVs are due to their high specific energy,

ing, a device that works on external energy is required to dissipate

long cycle life, and low auto-discharge features over other battery

heat from the LIBs to the ambient. Sending forced air using blowers,

chemistries [3]. However, the performance of the LIBs degrades with

forced liquid using pumps, and devices like thermoelectric coolers

an increase in their operating temperatures. The operating temperature

are examples of active cooling techniques [7,8]. In passive cooling,

of the LIBs is always on the rise under normal ambient conditions,

the generated heat is transferred by a natural phenomenon such as

as they generate heat during their charge/discharge operations due to

conduction, convection, and radiation. Heat spreaders, Phase Change

chemical reactions, charge transfer, and internal ohmic resistances. The

Material (PCM) based heat sinks, and heat pipes are examples in this

maximum operating temperature of LIBs is identified to be 60 ◦C from

passive cooling category [9]. Active cooling techniques are usually

the perspective of thermal safety and chemical efficiency [4,5]. The op-

more effective and capable than their counterparts in dissipating large

erating temperature above this limit degrades the battery performance, ∗ Corresponding author.

E-mail address: balaji@iitm.ac.in (C. Balaji). 1 Professor at IIT Madras.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.123146

Received 4 October 2023; Received in revised form 12 March 2024; Accepted 7 April 2024 Available online 16 April 2024

1359-4311/© 2024 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. R. Akula et al.

Applied Thermal Engineering 248 (2024) 123146 Nomenclature Subscripts 𝐴, 𝐵, 𝐶

Specific thermal resistance at melting point 𝐴𝑙 Aluminum temperature, K cm2∕W 𝑎𝑚𝑏 Ambient

𝐴 ∗, 𝐵 ∗, 𝐶 ∗

Specific thermal resistance at melt front 𝑏𝑎𝑡 Battery detach point, K cm2∕W 𝐶𝑢 Copper

𝐴′, 𝐵′, 𝐶′

Specific thermal resistance at thermal con- 𝑓 𝑖𝑛 Fin trol point, K cm2∕W ℎ𝑜𝑢 Housing 𝐴𝑚𝑢𝑠ℎ𝑦 Mushy zone constant, kg∕m3 s 𝑖 Tensor index 𝐴𝑏

Surface area of the battery, m2 𝑟𝑒𝑓 Reference state 𝐶 Specific heat, J∕kg K Acronyms ⃖⃗ 𝑔

Acceleration due to gravity, 9.81 m∕s2 ℎ

Total specific enthalpy, J∕kg C-rate

Charge/discharge current per nominal bat- ℎ𝑠 Sensible enthalpy, J∕kg tery capacity ℎ𝑙

Total latent heat content in body, J∕kg DAQ Data Acquisition ℎ0

Overall heat loss coefficient, W∕m2 K ED Energy Density 𝐼 current, A EDC Electric Density per Cost 𝑘 Thermal conductivity, W∕m K EV Electric Vehicles 𝐿 Latent heat of the PCM, J∕kg HEV Hybrid Electric Vehicles 𝑙 Fin height, mm ICE Internal Combustion Engine 𝑃 Power, P LIB Lithium ion batteries 𝑝 Pressure, N∕m2 PCM Phase Change Material 𝑞 Heat generation, W PRESTO PREssure STaggering Option 𝑞′

Volumetric heat generation, W∕m3 SIMPLE

Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure Linked ⃖⃖⃗ 𝑆 Source term, N∕m3 Equations 𝑡 Time, s SPT Set Point Temperature 𝑇 Temperature, ◦C TCE Thermal Conductivity Enhancer 𝑇𝑎 Ambient temperature, ◦C 𝑇𝐶

Temperature of battery at thermal control point, ◦C

cooling systems due to their advantages: lighter weight, simple design, 𝑇𝑚

Melting temperature of the PCM, ◦C

reliability, less prone to failure, and environmentally friendly [12,13].

𝑇𝑠𝑜𝑙𝑖𝑑𝑢𝑠

Solidus temperature of the PCM, ◦C

C-rate is the measure of current being used to charge or discharge

𝑇𝑙𝑖𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑑𝑢𝑠

Liquidus temperature of the PCM, ◦C

LIBs. The motors of EVs require more power during vehicle accelera- 𝑉 Voltage, V

tion. As a result, the batteries are discharged at higher C-rates (typically 𝑉𝑛 Nominal voltage, V

more than 2C). Whereas, the C-rates used for charging the vehicle are 𝑣 Volume, mm3

intentionally kept low to eliminate the adverse effects such as lithium 𝑣𝑡 Total volume, mm3

plating and capacity fading [14]. The amount of heat generation from ⃖⃗ 𝑣 Superficial velocity, m∕s

LIBs is proportional to the C-rate of charge or discharge [15]. In ⃖⃗ 𝑣

view of high discharge rates and low charge rates, the typical battery

𝑙𝑖𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑑

Liquid velocity of the PCM, m∕s 𝑉

thermal cycle consists of a heat generation phase for a shorter duration 𝑃 𝐶𝑀 Volume of the PCM, m3

(discharging phase) followed by a rest phase (charging phase) for a 𝑤 Fin width, mm

longer duration [16]. Since passive cooling techniques perfectly handle 𝑟, 𝜃, 𝑧 Radial coordinates

cyclic heat loads of moderate magnitudes, they can also be the best Greek letters

choice for the thermal management of LIBs. Many studies in literature

reported the potential use of passive cooling techniques for thermal 𝛼 Ratio of heat transfer area

management of LIBs [17–19]. Out of various passive cooling techniques 𝛾 Liquid fraction

available, solid–liquid Phase Change Material (PCM) based heat sinks 𝛥𝑇

Maximum temperature difference on the

are receiving the utmost attention from researchers all over the world battery surface, ◦C

due to their noteworthy characteristics, including high thermal energy 𝜇 Viscosity, Pa s

storage density, enhanced temperature uniformity, low cost, and stable 𝜌 Density, kg∕m3 chemical properties [20,21]. 𝜎 Uncertainty

Despite multiple advantages offered by the PCM, lower thermal 𝜙 Volume fraction of fins

conductivity of the PCM (typically <0.5 W∕m K) confines its vivid im-

plications in the battery thermal management systems. Lower thermal

conductivities offered by PCMs in heat sinks do not allow complete

exploitation of available latent heat, which makes cooling systems

amounts of heat into ambient [10]. However, disadvantages, including

inefficient and ineffective. Researchers have made considerable efforts

to discover several thermal conductivity enhancement techniques to

high cost, noise, maintenance, and external power requirements, hinder

overcome the drawback of lower thermal conductivities of PCMs [22,

their widespread applicability in various cooling requirements [11].

23]. One such method is suspending thermal conductive fillers into

Some Li-ion powered devices operate intermittently/cyclically, gener-

the PCM. This method was discussed by Samimi et al. [24], in which

ate moderate heat and do not require continuous assistance from the

carbon fibers are mixed with paraffin (a type of PCM), and reported

cooling system. In such cases, passive cooling systems dominate active

that the average thermal conductivity of PCM is enhanced by 105% 2 R. Akula et al.

Applied Thermal Engineering 248 (2024) 123146

and also proved that the thermal performance of mixture (PCM +

and PCM or water and PCM, also received greater advantage with

carbon fibers) surpassed air and pure PCM. Apart from adding fillers,

addition of fins in the PCM domain [42,43]. All these studies on PCM

saturating PCM into porous media, such as aluminum or copper foams,

based heat sinks for battery thermal management had used plate fins

can also effectively enhance the thermal conductivity [25] by creating

as the thermal conductivity enhancers to increase the effective thermal

thermal conductive paths. Khateeb et al. [26] proved that adding conductivity of the PCM.

aluminum foam to PCM in a PCM-based heat sink applied to a LIB

Though the usage of plate fins in PCM is effective, redesigning

module resulted in a temperature drop of 50%. In addition to the above-

them into pin fins may further enhance the thermal performance. It

mentioned Thermal Conductivity Enhancers (TCEs), finned structures

is noteworthy to mention here that the pin fins are the most effective

can also significantly improve the effective thermal conductivity of the

and common type of TCEs used in conjunction with PCM for electronic

PCM. Simple design, ease of fabrication, and enhanced heat transfer are

cooling and LHTES systems due to their superior performance over

the major features of the finned designs. Fins are predominantly used

other fin configurations whilst handling constant, cyclic, and surge heat

in various cooling techniques for thermal management of electronics,

loads [44]. Very few studies are available on application of pin-fin heat

automotive, and aerospace applications [27–30]; and also in energy

sinks for battery thermal management. Guo et al. [45] conducted three-

storage devices such as solar thermal storage systems, refrigeration

dimensional numerical studies on BTMS employing a mini-channel

systems, and cold storage systems to enhance heat transfer [31,32]. In

cold plate with pin fins. In their study, the performance of BTMS

the field of latent heat thermal energy storage (LHTES), many studies

is evaluated using Efficiency Index (𝐸𝐼) which considers both heat

concluded that the presence of fins spurred the rate of heat transfer

transfer performance and pressure loss. They found that the pin fins

into/away from the PCM and improved the thermal performance of

can improve the heat transfer performance of BTMS with acceptable LHTES systems [33,34].

pressure loss, i.e., 𝐸𝐼 > 1. The authors further added that the EI of

Despite having numerous applications for fin structures in various

vertically arranged pin fins was 4.54% higher than that of horizontally

fields of thermal management and thermal storage, their usage still

arranged pin fins. Mohammadian and Zhang [46] also worked on incor-

needs attention in the realm of thermal management of LIBs. In the

poration of pin fins with linear increment of height in the direction of

limited research available on PCM-fin composite heat sinks for thermal

coolant flow to enhance heat transfer. The effect of pin fin arrangement,

management of 18650 LIBs, the studies conducted by Wang et al.

discharge rates, inlet air flow velocities, and temperatures on battery

[35], Weng et al. [36], and Sun et al. [37] are significant. Wang

are investigated. There are a few more studies on the use of pin fins in

et al. [35] experimentally examined the thermal behavior of cylindrical

the BTMS, however, they too had discussed the designs for enhancing

heat transfer between pouch batteries and coolant [47] but not between

battery when it was inserted in paraffin-fin composite structure. They

the cylindrical batteries and the coolant. Akula and Balaji [15] were

concluded from the experimental results that the composite PCM-fin

one of the earliest in introducing pin fins for thermal regulation of

system had good thermal performance with prolonged work time.

cylindrical batteries for higher discharge rates. The authors considered

The authors further identified the logarithmic dependence of the time

three heat sinks with zero, 130, and 260 pin fins to investigate the effect

averaged Nusselt number with the heat transfer area. Weng et al. [36]

of pin fins on the temperature distribution over battery surface. From

conducted series of experiments on PCM based heat sink without and

the detailed experimental investigation, the authors concluded that the

with fins for thermal management of 18650 cylindrical Li-ion batteries

heat sink with 260 pin fins outperformed other heat sink configurations

to investigate the effects of fin configurations on the temperature

by recording 14.2, 17.6, and 19.1 ◦C lower temperatures compared to

evaluation under 1C/2C discharge rates. The authors proved from the

plain heat sink for discharge rates 2, 3, and 4C, respectively. However,

experimental investigations that increasing fin number beyond certain

the study had considered only three heat sinks to propose the best heat

limit does not yield any thermal advantage. From their study, they sink.

further identified that the optimum number of longitudinal fins were

Based on the detailed literature survey conducted on the BTMS, it is

four for the maximum thermal regulation in a limited-space mod-

clear that the effect of geometrical parameters associated with pin fins

ule. Zare et al. [38] also studied the effect of fin number in addition to

for thermal management of cylindrical LIBs using PCM based heat sinks

the other parameters including heat storage capacity, energy density,

have not been studied so far, either experimentally or numerically.

and heat storage capacity on thermal performance. From the detailed

The goal of this study is not only to address these gaps but also the

numerical investigations, the authors found that the BTMS with four

following shortcomings of the previous studies: impact of pin fin shape,

internal–external plate fins regulated the operating temperature of the

size, and number on the temporal evolution of temperature distribution

battery below 45 ◦C even at the ambient temperature of 35 ◦C, while

on LIBs, quantification of the influence of various PCMs and ambient

providing 32.81, 11.11, and 10.02% higher fin efficiency, heat storage

temperatures on the thermal regulation capability of pin fins, and

capacity, and energy density, respectively, compared to the BTMS

thermal performance comparison of pin fin based heat sinks proposed

without fins. Furthermore, Sun et al. [39] proposed novel fin structures

in the present study against literature for different heat loads generated

constituting straight and arc fins for heat transfer enhancement. From

by the LIBs operate at higher discharge rates.

their experimental investigations, they proved that the proposed fins

prolong the working time of the battery by 54%–90% compared to pure

2. Numerical methodology

PCM under various discharge conditions. Zhang et al. [40] introduced

different fin configurations including straight, cross, branch, T, I, V, and 2.1. Physical model

N-shape fins to enhance the effective thermal conductivity of the PCM

and compared their thermal performance against conventional straight

The main idea of the present study is to find the best pin fin

fins under 5C discharge rate. From the numerical investigations, they

configuration that reports the lowest average temperature and thermal

concluded that all the newly introduced fin configurations showed su-

gradients on the battery surface. Four heat sinks with 0, 2, and 4 plate

perior performance over conventional straight fins. The authors further

fins are initially considered. These heat sinks are geometrically in line

modified the new designs by changing transverse fin converge area

with the heat sinks considered by Wang et al. [35] in their experimental

and fin number to obtain the thermal regulation advantage of 3.14

study for thermal management of an 18650 Li-ion battery. Later, a

and 3.92 ◦C, respectively. Similarly, Weng et al. [41] also studied the

heat sink configuration employing 130 pin fins with the same volume

thermal performance of PCM based heat sinks with fins of shapes V,

fraction as 2 and 4 plate fins, is introduced. Following this, pin fins

Y, and X under ambient temperature of 40 ◦C and observed that the

with different fin sizes and fin numbers are also modeled and simulated

X-shaped fins delivered the best performance by regulating the battery

to identify the best heat sink configuration. All the numerical models

temperature below 47 ◦C. From the holistic perspective, the hybrid

in the present study are designed using the Design modular software

battery thermal management systems, which are combinations of air

available in commercial Ansys 2020R2. 3 R. Akula et al.

Applied Thermal Engineering 248 (2024) 123146

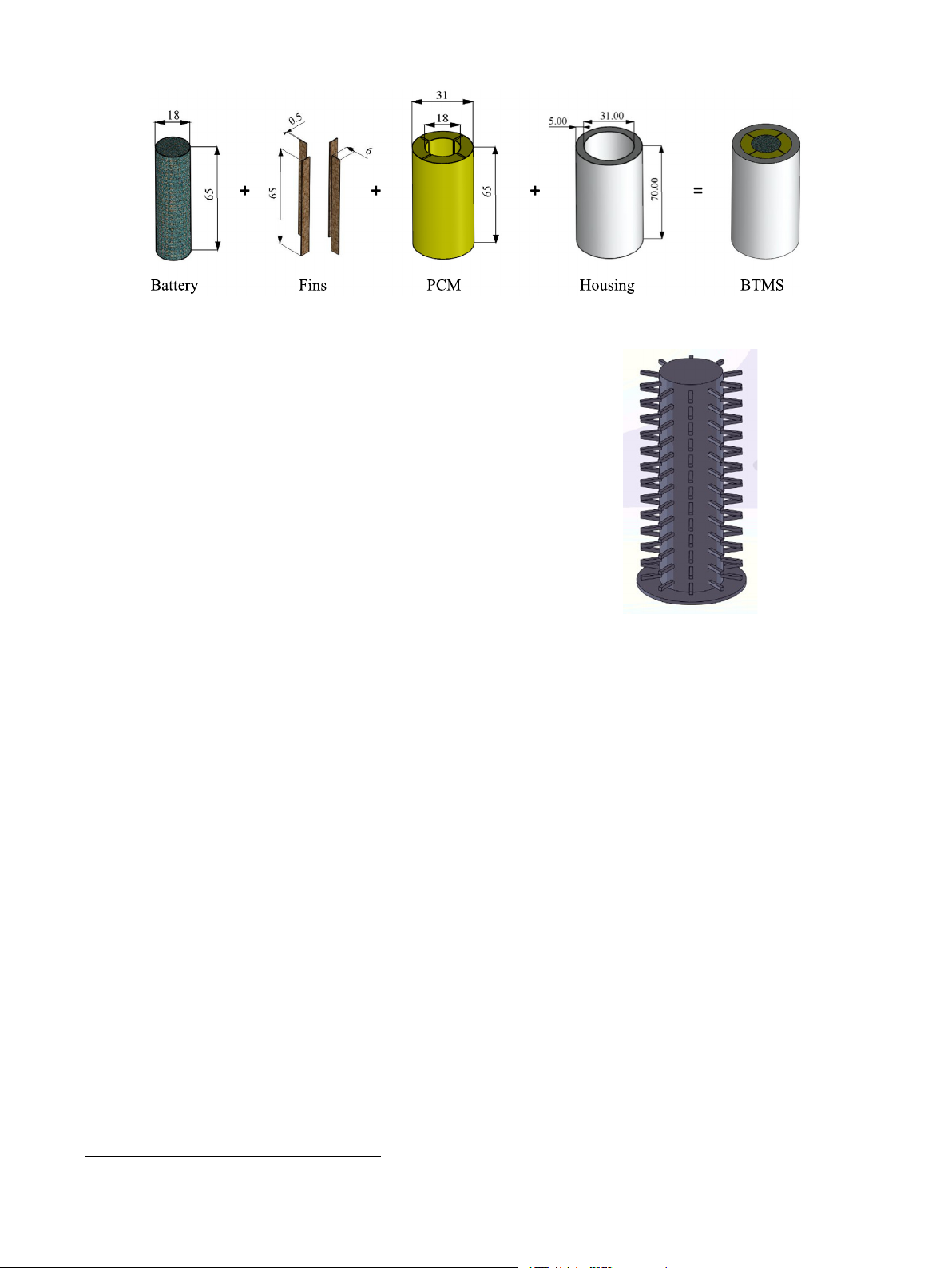

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of BTMS with four plate fins.

Heat sink configurations with plate fins

Three heat sinks, with zero, two, and four plate fins attached on

the outer periphery of the simulated battery, are considered in the

present study for preliminary investigations. In the case of heat sink

configuration with two plate fins, the fins on the battery surface are

separated by 180 degrees. Whereas, for heat sink configuration with

four plate fins, the fins are separated by 90 degrees. The arrangement

of BTMS in the present study is as follows: The 18650 simulated battery

is placed at the center surrounded by fins submerged in PCM. The outer

housing and heat sink base (5 mm thick) further confines the PCM in

the heat sink (see Fig. 1). All the plate fins, either in the case of heat

sink with two or four plate fins, have dimensions of length (or height)

and width equal to 65 and 6 mm, respectively. The thickness of each

fin is equal to 1 mm in the case of the heat sink with two plate fins,

whereas it is equal to 0.5 mm in the case of the heat sink with four plate

fins. Battery with the fins setup is placed in a housing with length, inner

diameter, and thickness are equal to 70, 31, and 5 mm, respectively.

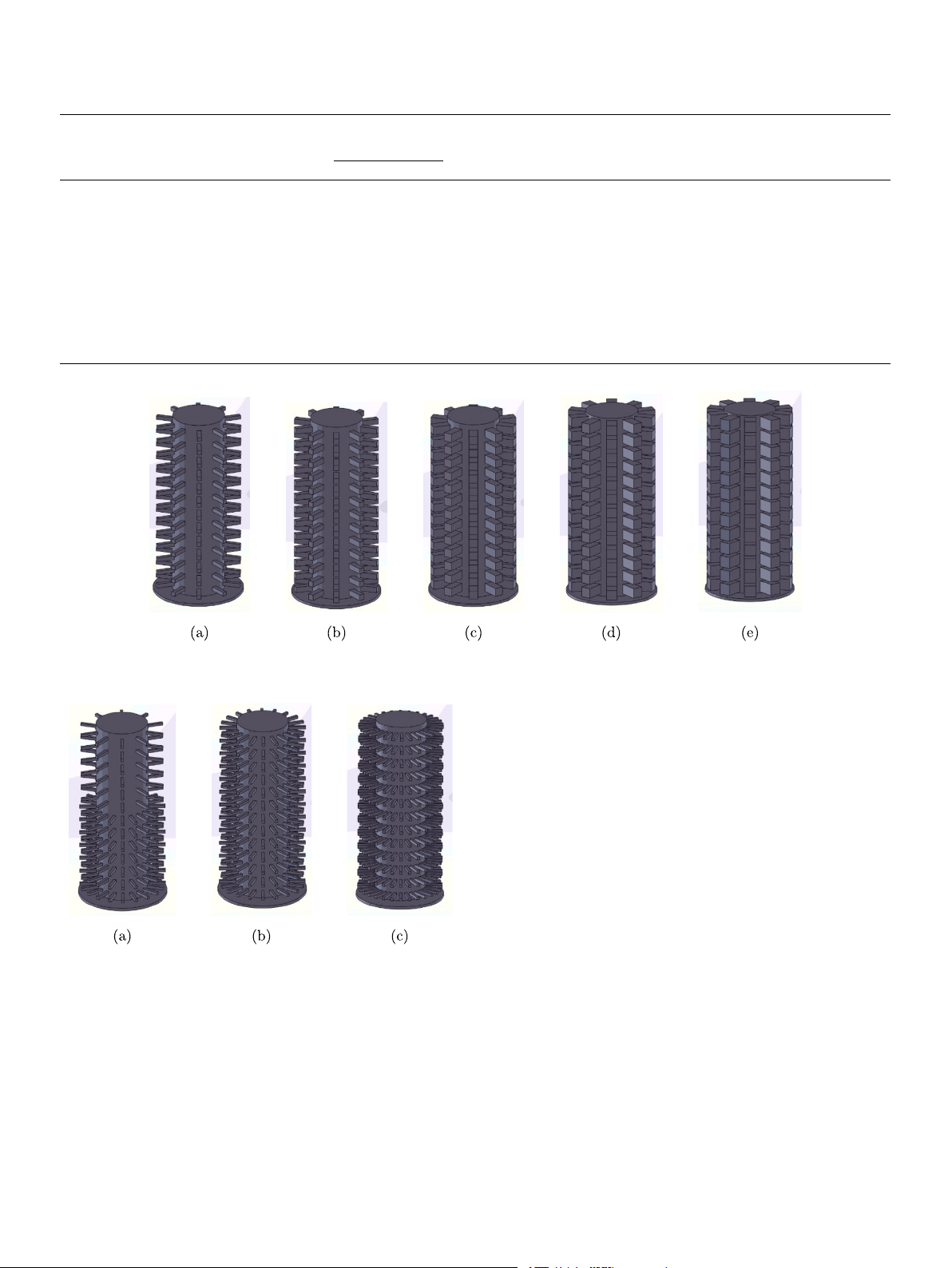

Fig. 2. Schematic representation of base, and battery with 130 pin fins (each fin of

The gap between the battery with fins and the housing is filled with

size 1 mm) on its outer periphery.

PCM. The volume fraction of fins (𝜙) in the present study is defined as

the ratio of volume of fins to the combined volume of fins and PCM

(see Eq. (1)). As per the definition, the volume fraction of fins for the

Heat sink configurations with various pin fins

heat sinks with 2 and 4 plate fins is the same and equal to 2.4%.

To comprehensively evaluate the advantages offered by pin fins,

various heat sink configurations with different fin numbers and sizes

Volume fraction of fins(𝜙)

are considered. The dimensions and arrangement of the 130-pin fin

Volume of fins (𝑣𝑓𝑖𝑛) = (1)

heat sink, with each fin having a square cross-section of a side equal to

Volume of fins (𝑣𝑓𝑖𝑛) + Volume of PCM (𝑣𝑃 𝐶𝑀 )

1 mm, are already discussed in the previous section. Further, five more

heat sinks, each has 130 fins with square cross-section, but with sides

equal to 1.4, 2, 3, 3.5, and 4 mm are modeled to identify the effect of

Heat sink configuration with 130 pin fins

fin size (see Fig. 3) on the thermal performance. The volume fractions

A heat sink employing 130 pin fins with the same volume fraction

of fins for these five heat sink configurations with fin sizes 1.4, 2, 3,

of 2.4% is modeled numerically, as shown in Fig. 2. All the designed

4.5, and 4 mm are calculated to be 4.7, 9.6, 21.6, 29.4, and 38.4%,

pin fins have a square cross-section, with side and length are equal to

respectively. In addition to these five heat sinks, three more heat sinks,

1 and 6 mm, respectively. A total of 13 fin sets, each containing ten

each with square fins of side 1 mm, but with different fin numbers

equally spaced pin fins along the circumference in the radially outward

equal to 200, 260, and 390 are also modeled as shown in Fig. 4. The fin

direction from the battery, are placed at equidistant positions (3.7 mm)

arrangement for heat sinks with 260 and 390 fins is the same as that

along the length of the battery. The simulated battery with 130 fins

with 130 fins, but the number of fins on each fin set is doubled and

is placed in the same PCM and housing with the same geometrical

tripled, respectively. The heat sink with 200 fins is a special case. In

dimensions considered for heat sinks with plate fins. The ratio of heat

this configuration, seven fin sets, with 20 fins in each set, are attached

transfer area (𝛼) is defined as the ratio of contact areas between battery

from the bottom of the battery, whereas six fin sets, with ten fins in

and PCM for with and without fins (see Eq. (2)). The contact area,

each set, are attached from the top. Each fin set is equally spaced along

between PCM and battery with fins, changes based on the fin size and

the battery length, as observed in other pin-fin configurations in this

number of fins. Whereas, the contact area between PCM and battery

study. The reason behind considering the heat sink configurations with

without fins is the same for all the fin configurations and the value is

this fin arrangement is as follows. Conduction and convection are the

equal to 3670 mm2. As per the definition, the values of 𝛼 for the heat

dominating modes of heat transfer in the bottom and top portions of

sinks with 2 and 4 plate fins, and 130 pin fins are equal to 1.39, 1.81,

cylindrical arrangements, respectively, when they erected vertically. and 1.81 respectively.

Hence, the heat sink configuration, with more fins at the bottom and

Contact area between PCM and battery with fins

fewer fins at the top, may have a high chance of enhancing conduction 𝛼 = (2)

Contact area between PCM and battery without fins

and convection simultaneously in the PCM domain. The geometrical

parameters, such as spacing and volume fraction of the fins, and the 4 R. Akula et al.

Applied Thermal Engineering 248 (2024) 123146 Table 1

Geometric parameters associated with the heat sinks considered in this study. S.no Heat sink No. of Fin size (mm) Spacing Fins’ PCM Volume Fin’s heat Ratio of type fins b/w fins volume volume fraction transfer heat transfer (mm) (mm3) (mm3) of fins area (mm2) area (𝛼) Width (w) Height (l) 1 Plain heat sink 0 – – – 0.0 32 500.0 0 0 1.00 2 Two plate fins 2 1.0 65.0 27.3 780.0 31 720.0 2.4 1560 1.39 3 Four plate fins 4 0.5 65.0 13.6 780.0 31 720.0 2.4 3120 1.81 4 130 pin fins (1 mm) 130 1.0 1.0 4.7 780.0 31 720.0 2.4 3120 1.81 5 130 pin fins (1.4 mm) 130 1.4 1.4 4.3 1528.8 30 971.2 4.7 4368 2.12 6 130 pin fins (2 mm) 130 2.0 2.0 3.7 3120.0 29 380.0 9.6 6240 2.56 7 130 pin fins (3 mm) 130 3.0 3.0 2.7 7020.0 25 480.0 21.6 9360 3.23 8 130 pin fins (3.5 mm) 130 3.5 3.5 2.2 9555.0 22 945.0 29.4 10 920 3.54 9 130 pin fins (4 mm) 130 4.0 4.0 1.7 12 480.0 20 020.0 38.4 12 480 3.83 4.7 (Top) 10 200 pin fins (1 mm) 200 1.0 1.0 1200.0 31300.0 3.7 4800 2.25 1.8 (Bottom) 11 260 pin fins (1 mm) 260 1.0 1.0 1.8 1560.0 30 940.0 4.8 6240 2.63 12 390 pin fins (1 mm) 390 1.0 1.0 0.9 2340.0 30 160.0 7.2 9360 3.44

Fig. 3. Schematic representation of battery and 130 fins, with each fin of size equal to (a) 1.4 mm, (b) 2 mm, (c) 3 mm, (d) 3.5 mm, and (e) 4 mm.

particular C-rate, the discharge/charge current is capacity times the C-

rate, and the duration is capacity times inverse of the C-rate. With this

mathematical definition, one can calculate the current and operating

time of the battery for any discharge rate. For example, a battery with

3 Ah capacity produces 6 A of current for 0.5 h when it is discharge

at a rate of 2C. Batteries generate heat in proportion to their discharge

rates. The heat generation from any LIB varies continuously with time,

even for a constant discharge. Despite variable heat generation with

time in the real batteries, a constant heat load, obtained by the time

average of varying heat generation, is taken as a heat load in the

present study for simplifying the analysis. Constant heat generation

is a valid assumption and widely used by researchers in the thermal

management studies of LIBs [39,48–50]. Heat generation rates of a

Panasonic NCR18650BD battery are observed to vary between 2.6 to

5.6, 4.2 to 8.0, and 6.4 to 10.4 W, in almost linear fashion, for 3C, 4C,

Fig. 4. Schematic representation of battery with number of fins on each battery are

equal to (a) 200, (b) 260, and (c) 390, with each fin of size equal to 1 mm.

and 5C discharge rates, respectively [15]. Given this, the time average

heat generation rates from the same battery are taken as 4, 6, and 8 W

for 3, 4, and 5C discharge rates for thermal performance evaluation of

ratio of heat transfer area (𝛼) for all the heat sinks considered in the

the above-mentioned heat sinks.

present study are tabulated in Table 1.

The present study conducts thermal performance comparison stud-

ies among different heat sinks for a 5C discharge rate. The best heat sink 2.2. Heat generation

obtained from this thermal analysis for a 5C discharge rate is further

characterized for 3 and 4C discharge rates and their corresponding

As mentioned in the introduction chapter, the rate at which the

results are also reported. After obtaining the best heat sink from the

battery is charged/discharged is defined as the C rate. For example,

thermal performance comparison analysis with constant heat loads, it

if a battery has a capacity of 3 Ah and is discharged at a 1C rate, it

is again characterized for transient heat loads obtained from Panasonic

indicates that 3 A of current can be withdrawn for one hour. For a

NCR18650BD battery at 3, 4, and 5C discharge rates. 5 R. Akula et al.

Applied Thermal Engineering 248 (2024) 123146 Table 2

energy equations are solved in the solid regions (battery, housing, and

Thermophysical properties of the materials considered in the present study [54,55]. fins) of the heat sinks. Materials Thermal Specific heat Density ( ) ( ) conductivity (J/kg K) (kg/m3) 𝜕 𝜕 𝜕𝑇

𝜌𝑏𝑎𝑡ℎ𝑏𝑎𝑡 = 𝑘𝑏𝑎𝑡 + 𝑞′ (3) (W/m K) 𝜕𝑡 𝜕𝑥𝑖 𝜕𝑥𝑖 ( ) Acrylic 0.21 1470 1190 𝜕 ( ) 𝜕 𝜕𝑇 𝜌 = 𝑘 (4) Aluminum 202 900 2719 𝜕𝑡

ℎ𝑜𝑢ℎℎ𝑜𝑢 𝜕𝑥 ℎ𝑜𝑢 𝑖 𝜕𝑥𝑖 Copper 401 385 8933 ( ) 𝜕 ( ) 𝜕 𝜕𝑇 Panasonic NCR18650BD 𝑘 = 0.413 959 1113 𝑟

𝜌𝑓𝑖𝑛ℎ𝑓𝑖𝑛 = 𝑘𝑓𝑖𝑛 (5)

𝑘 = 𝑘 = 1.78 𝜕𝑡 𝜕𝑥 𝜕𝑥 𝜃 𝑧 𝑖 𝑖

In Eqs. (3)–(5), 𝑞′, 𝜌, ℎ, and 𝑘 represent volumetric heat generation,

density, specific enthalpy, and thermal conductivity, respectively. Suf-

2.3. Mathematical formulation

fixes 𝑏𝑎𝑡, ℎ𝑜𝑢, and 𝑓 𝑖𝑛 represent the domains of battery, housing, and

fins, respectively. The continuity, momentum, and energy conservation

Thermal performance evaluations of different heat sink configura-

equations solved in the PCM domain are as follows.

tions in the present study are performed using ANSYS Fluent 2020 R2. Continuity equation:

The properties of aluminum are assigned to housing and the simulated

𝜕𝜌 + 𝜌(∇.⃖⃗𝑣) = 0 (6)

battery domains, whereas the properties of copper are assigned to fins. 𝜕𝑡

The gap between the housing, fins, and battery is filled with PCM. Momentum equation:

Paraffin wax is the most commonly used PCM for low temperature ( )

thermal management applications due to its noteworthy characteristics 𝜕⃖⃗ 𝑣 𝜌 + ⃖⃗ 𝑣.∇⃖⃗ 𝑣

= −∇𝑝 + 𝜇∇2 ⃖⃗

𝑣 + 𝜌⃖⃗ 𝑔 + ⃖⃖⃗ 𝑆 (7) 𝜕𝑡

including suitable melting point temperature, high latent heat, and low

thermal expansion coefficient [37,38,40]. In view of several advantages Energy equation:

with paraffin wax, the heat sinks considered in the present study are 𝜕

filled with the same PCM for their thermal performance comparison.

(𝜌ℎ) + ∇.(𝜌⃖⃗

𝑣ℎ) = ∇.(𝑘∇𝑇 ) (8) 𝜕𝑡

Moreover, an additional investigation is also carried out at the end of

In Eq. (7), 𝜇 represents dynamic viscosity of the PCM. The pressure in

present study to identify the effect of PCM on the thermal performance

the PCM domain is represented by 𝑝, and the gravity that acts vertically

of the heat sink. Properties of all the materials used in the present study

downwards in the −ve 𝑧-direction is represented by ⃖⃗ 𝑔.

are articulated in Tables 2 and 3. Although the battery is made of com-

The ratio of volumes of liquid PCM to total PCM in each mesh cell

posite materials in reality, the reason behind choosing an aluminum rod

is defined as the liquid fraction. The melt front movement in the cells

as a simulated battery in the present study is as follows: Invariably, all

is tracked using their respective liquid fraction values. The region of

studies on thermal management of LIBs in literature focused on surface

the solid–liquid phase transition in PCM is a porous zone with porosity

temperature of the battery. While designing cooling systems for LIBs at

equal to the liquid fraction in that particular cell. The solidus and

high discharge rates, real batteries are not preferred in the experiments

liquidus temperatures are used to define porosity or liquid fraction, 𝛾,

due to safety concerns. The real batteries are replaced with metallic

in a particular cell, as follows.

rods integrated with heaters. Actual heat generation profiles from the

real batteries, which are estimated using battery models, are used to ⎧ ⎪0

𝑇 < 𝑇𝑠𝑜𝑙𝑖𝑑𝑢𝑠

power the heaters in the metallic rods to mimic the actual battery ⎪

𝑇 − 𝑇𝑠𝑜𝑙𝑖𝑑𝑢𝑠

behavior. By using highly conductive material (aluminum in this study) 𝛾 = ⎨ 𝑇 𝑇

𝑠𝑜𝑙𝑖𝑑𝑢𝑠 < 𝑇 < 𝑇𝑙𝑖𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑑𝑢𝑠

𝑙𝑖𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑑𝑢𝑠 − 𝑇𝑠𝑜𝑙𝑖𝑑𝑢𝑠

as the simulated battery, its surface and core temperatures are almost ⎪ ⎪1 𝑇 > 𝑇

the same and higher than the surface temperature of actual battery ⎩

𝑙𝑖𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑑𝑢𝑠

under the same heat generation rates. It is always better to design

The superficial velocity (⃖⃗

𝑣) in the governing equations is equal to

a cooling system for higher temperatures than the usually observed

porosity (𝛾) times the liquid PCM velocity vector (⃖⃗

𝑣𝑙𝑖𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑑 )

temperatures on the surface of the actual batteries. As a result, the

heat sink, which is designed based on the temperature evaluations ⃖⃗

𝑣 = 𝛾 × ⃖⃗

𝑣𝑙𝑖𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑑 (9)

of simulated battery will definitely work for real battery. The same

The total enthalpy (ℎ) of the PCM in a particular cell at a time instant

assumption has been considered by several researchers in their studies

is the sum of sensible enthalpy (ℎ

on BTMS [51–53]. However, out of all the heat sink configurations

𝑠) and the utilized latent heat (ℎ𝑙 )

obtained from the temperature state and liquid fraction, respectively,

considered in Section 2.1, the outperforming heat sink, which effec- as shown below

tively regulates the thermal excursions of the simulated battery, is again

tested for its applicability for a real battery with actual thermophysical

ℎ = ℎ𝑠 + ℎ𝑙 (10) properties.

The following assumptions are made while performing the numeri- where, cal simulations [57,58]. 𝑇

ℎ𝑠 = ℎ𝑟𝑒𝑓 + 𝐶.𝑑𝑇 (11)

(i) Unsteady, laminar flow of the liquid PCM. ∫𝑇𝑟𝑒𝑓

(ii) Density variation of the PCM is taken care by the Boussinesq

ℎ𝑙 = 𝛾𝐿 (12) approximation.

(iii) The thermal conductivity, density, and specific heat of the PCM

In the above equations (Eqs. (11) and (12)), the notations C and L

in both the solid and liquid phases are constant [41,42].

represent specific heat and latent heat of the PCM, respectively.

(iv) Volume expansion of the PCM is negligible [37,38,40].

The momentum sink term in Eq. (7) is given by

(v) Radiation heat loss from any surface is negligible. (1 − 𝛾)2 ⃖⃖⃗ 𝑆 = − . 𝐴

(vii) The contact resistance between the heat sink and the TCEs is

𝑚𝑢𝑠ℎ𝑦.⃖⃗ 𝑣 (13) 𝛾3 + 𝑐 negligible.

In Eq. (13), c is a small number (0.001), added to 𝛾3, to avoid zero

In the PCM domain, the governing equations for continuity, mo-

in the denominator. The mushy zone, an interface of solid and liquid

mentum, and energy are solved, simultaneously, using the enthalpy-

phases, allows a smooth velocity transition from solid to liquid phases.

porosity approach proposed by Voller and Prakash [59]. The following

The development of velocity vectors and their strength in the liquid 6 R. Akula et al.

Applied Thermal Engineering 248 (2024) 123146 Table 3

Thermophysical properties of the PCMs considered in the present study [38,55,56]. Materials Thermal conductivity Specific heat Latent heat Melting point Density Thermal expansion (W/m K) (kJ/kg K) (J/kg) (◦C) (kg/m3) coefficient (K−1) Eicosane 0.23 2.10 (solid) 255 000 35–42 781 (solid) 0.00086 2.42 (liquid) 759 (liquid) Paraffin wax 0.22 1.93 (solid) 272 600 41–44 880 (solid) 0.00076 2.38 (liquid) 770 (liquid) Tetracosane 0.25 1.87 (solid) 289 600 47–54 777 (solid) 0.00094 2.29 (liquid) 746 (liquid)

PCM is decided by the mushy zone constant (𝐴𝑚𝑢𝑠ℎ𝑦) in the momentum

using Ansys Fluent 2020R2 are conducted on each mesh model for

equation (Eq. (7)). The increase in the mushy zone constant decreases

every heat sink configuration, and the temporal variation of average

the strength of convection currents in the liquid PCM and vice versa.

battery temperature for 5C discharge is noted. Fig. 5(b) shows the

temperature–time history of the average battery temperature of the

2.4. Initial and boundary conditions

plain heat sink for the three grid sizes 1, 0.5, and 0.32 mm when

subject to a discharge rate of 5C (constant heat generation rate of

The initial and boundary conditions are set in accordance with the

8 W). The maximum discrepancy in the average battery temperatures

experiments conducted by Wang et al. [35].

obtained from the grid sizes 0.5 mm and 0.32 mm are less than 1%. At time, 𝑡 = 0

By taking accuracy and computational cost as important objectives, 𝑇 = 𝑇

the mesh with an element size of 0.5 mm has been taken as the

𝑏𝑎𝑡 = 𝑇𝑓 𝑖𝑛 = 𝑇𝑃 𝐶𝑀 = 𝑇ℎ𝑜𝑢 = 25 ◦C (14)

optimum grid size for generating mesh on the plain heat sink. Grid

The top and bottom surfaces of the heat sink are insulated,

and time independence studies are also conducted for all the remaining 𝜕𝑇 𝜕𝑇 𝜕𝑇 𝜕𝑇

heat sink configurations considered in Section 2.1. Their results show = 𝑏𝑎𝑡 = 𝑃 𝐶𝑀 = ℎ𝑜𝑢 = 0 (15) 𝜕𝑧 𝜕𝑧 𝜕𝑧 𝜕𝑧

that the grid size of 0.5 mm is sufficient to accurately predict the

At the interface between battery and PCM, the following equation is

temporal variation of average temperature for the remaining heat sink valid

configurations. However, the solutions did not converge during melting 𝜕𝑇 𝜕𝑇

when the time step size was 0.5 s. Given this, a time step size of 0.1 s − 𝑏𝑎𝑡 𝑃 𝐶𝑀 𝑘𝑏𝑎𝑡 = −𝑘 (16) 𝜕𝑟 𝑃 𝐶𝑀 𝜕𝑟

is set for the melting, and 0.5 s is used during the pre and post-melting

Natural convection heat loss with heat loss coefficient ℎ

phases of PCM for all the heat sinks in all the simulations carried out 0 (details of the choice of ℎ in this study.

0 are given in Section 2.6) is given as a boundary condition

on the outer curved surface of the housing, as follows 𝜕𝑇

2.6. Validation of current numerical methodology − ℎ𝑜𝑢 𝑘𝑏𝑎𝑡 = ℎ 𝜕𝑟

0(𝑇ℎ𝑜𝑢 − 𝑇𝑎𝑚𝑏) (17)

The Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure Linked Equations (SIMPLE)

To validate the numerical methodology adopted in the present

algorithm is used for pressure-velocity coupling, and the PREssure

study, the numerical results for the heat sink configurations with plate

STaggering Option (PRESTO) scheme is adopted for pressure correction

fins are compared against the experimental results of the same heat sink

equations. The Second Order upwind scheme is used for discretizing

configurations reported by Wang et al. [35] for a discharge rate of 5C

momentum and energy equations, and the first-order implicit method

(constant heat load of 8 W). A parametric study is conducted to identify

is used for transient formulation. The under-relaxation value factors

the appropriate heat loss coefficient (ℎ0), which needs to be given as a

are set at 0.3, 1.0, 0.7, and 0.9 for pressure, density, momentum, and

boundary condition on the outer walls of the heat sinks in the numerical

liquid fraction, respectively. The convergence criteria for continuity,

simulations, to quantify the heat loss to the ambient. Three heat loss

momentum, and energy equations are set at 10−4, 10−6, and 10−8,

coefficients 5, 10, and 15 W/m2K are applied as boundary conditions

respectively. The Aqua cluster, a high-performance computing facility

on the outer surface of the housing in the current numerical modeling

at the Indian Institute of Technology Madras, India, is used to perform

and compared the obtained numerical results against the experimental the computations.

results reported by Wang et al. [35]. The discrepancy between the

experimental results reported by Wang et al. [35] and the numerical

2.5. Grid independence study

results obtained for heat loss coefficient of 10 W/m2K is the lowest

compared to heat loss coefficients 5 and 15 W/m2K (see Fig. 6(a)).

Grid and time-step independence studies are necessary to ascertain

In view of this, a heat loss coefficient of 10 W/m2K is applied as the

the appropriate spatial and temporal discretization for generating mesh

boundary condition on the outer surface of the housing for validation

on various heat sink configurations considered in the present study.

of other heat sink configurations with 2 and 4 plate fins. Figs. 6(b)

As fin dimensions change from geometry to geometry and the full

Navier–Stokes equations are being solved in the PCM domain, the

and 6(c) show the comparison of the average battery temperatures

mesh quality of both fins and PCM domains decides the accuracy of

obtained from the current numerical methodology, with 10 W/m2K as

simulation results. Given this, the grid independence study is conducted

the heat loss coefficient, against experimental results reported by Wang

only for the PCM and fin domains. Tetrahedral elements with different

et al. [35] for 2 and 4 plate fins, respectively. The maximum difference

element sizes, 1, 0.5, and 0.32 mm, are considered to generate a

between the experimental and the numerical results for the heat sink

mesh in the PCM and fin domains. The same type of elements with

configurations with 2 and 4 plate fins is identified to be less than 5%.

a 1 mm size is chosen to generate a mesh in other parts of the heat

Given the close agreement between the experimental and numerical

sink (battery and housing) for all the heat sink geometries presented

results, the current numerical methodology is assumed to give accu-

in Section 2.1. Fig. 5(a) shows the plain heat sink with tetrahedral

rate results. Hence, the same numerical methodology is adopted to

mesh elements of size 1 mm in the battery and housing domains and

explore the flow and heat transfer characteristics of the other heat sink

of size 0.32 mm in the PCM and fins domains. Numerical simulations

configurations considered in this study. 7 R. Akula et al.

Applied Thermal Engineering 248 (2024) 123146

Fig. 5. Figures showing (a) meshed model of plain heat sink with tetrahedral elements of size 0.32 mm in the PCM and fin domains and the same type of elements with size

1 mm in the battery and housing domains, and (b) results of the grid independence study conducted on a plain heat sink for 5C discharge (constant heat load of 8 W).

Fig. 6. Comparison of average temperature–time histories, obtained experimentally by Wang et al. [35] and numerically from the current numerical methodology, for (a) plain

heat sink with heat loss coefficients 5, 10, and 15 W∕m2K, and for (b) heat sinks with 2 plate fins and for (c) 4 plate fins with heat loss coefficient equal to 10 W∕m2 K.

3. Results and discussion

be as low as possible for any configuration to be considered as the best-performing heat sink.

Two performance metrics are used in the present study to evaluate

This section is organized as follows. Initially, the advantage of

the thermal performance of the heat sinks. One is the average surface

adding PCM to the heat sink is quantified. After that, the superiority

temperature of the battery, and other is the maximum temperature dif-

of the pin fins over plate fins in the thermal regulation of the battery

ference on the surface of the battery. The average surface temperature

is presented. Following this, the influence of changing fin size and

and the maximum temperature difference on the battery surface should

the effect of changing fin number on the battery temperature are 8 R. Akula et al.

Applied Thermal Engineering 248 (2024) 123146

the operation in terms of temperature uniformity and regulation of

average temperatures. It is further observed from Fig. 8 that the heat

sink with 130 pin fins records slightly higher average temperatures than

latter heat sinks near the set point temperature (SPT) of 60 ◦C (see

Fig. 8(b)). However, this difference is observed to be minimal (<1 ◦C).

In view of lower operating temperatures (except near SPT) and higher

temperature uniformity throughout the operation, the heat sink with

130 pin fins is a better option compared to heat sinks with 2 and 4 plate

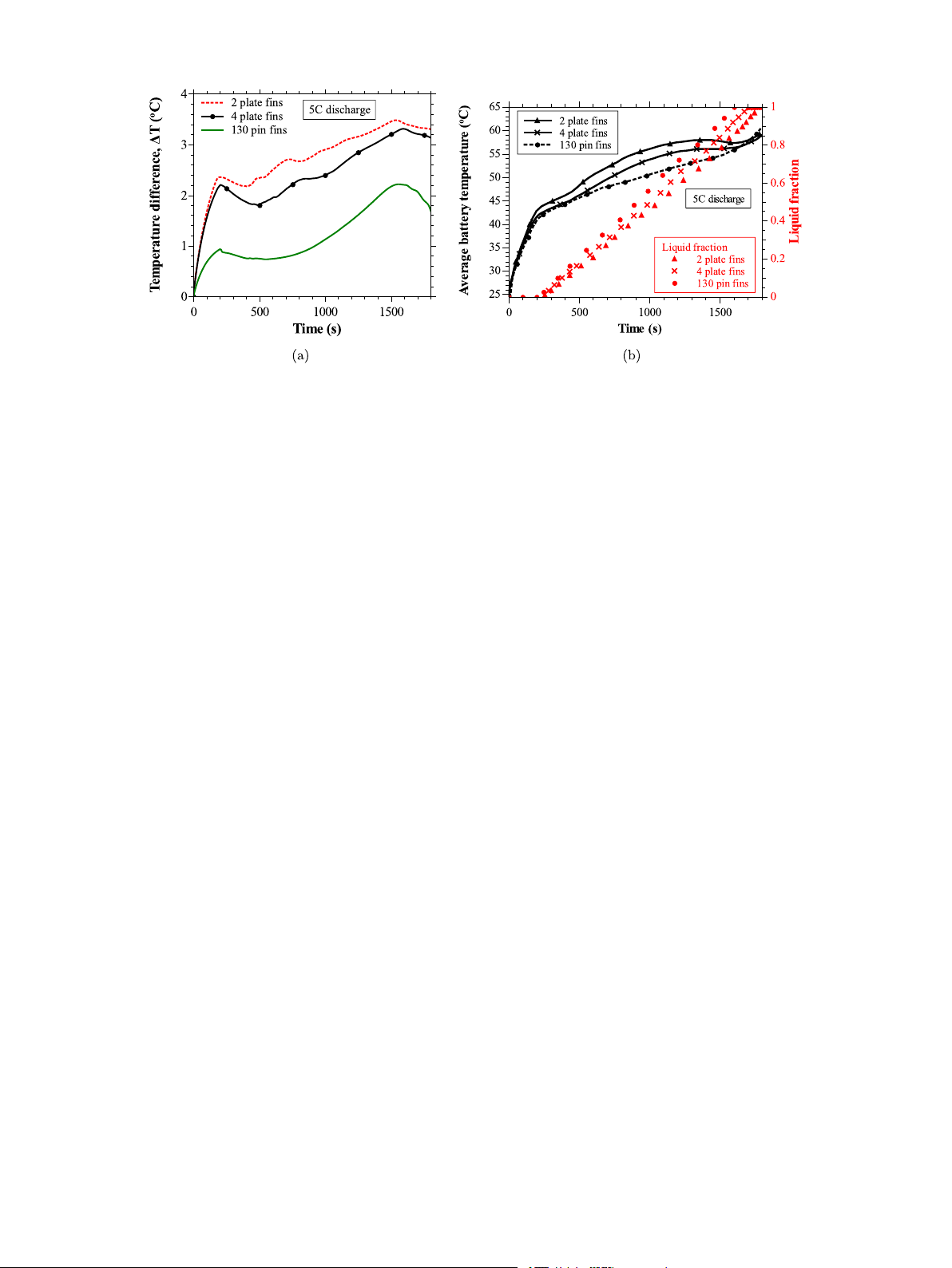

fins. From the liquid fraction-time histories reported in Fig. 8(b), it is

clear that the accelerated melting of PCM in consequence of uniform

and swift diffusion of heat through pin fins is the major reason for the

greater thermal regulation with heat sink of 130 pin fins. The superior

performance of pin fins over plate fins can be further explained using

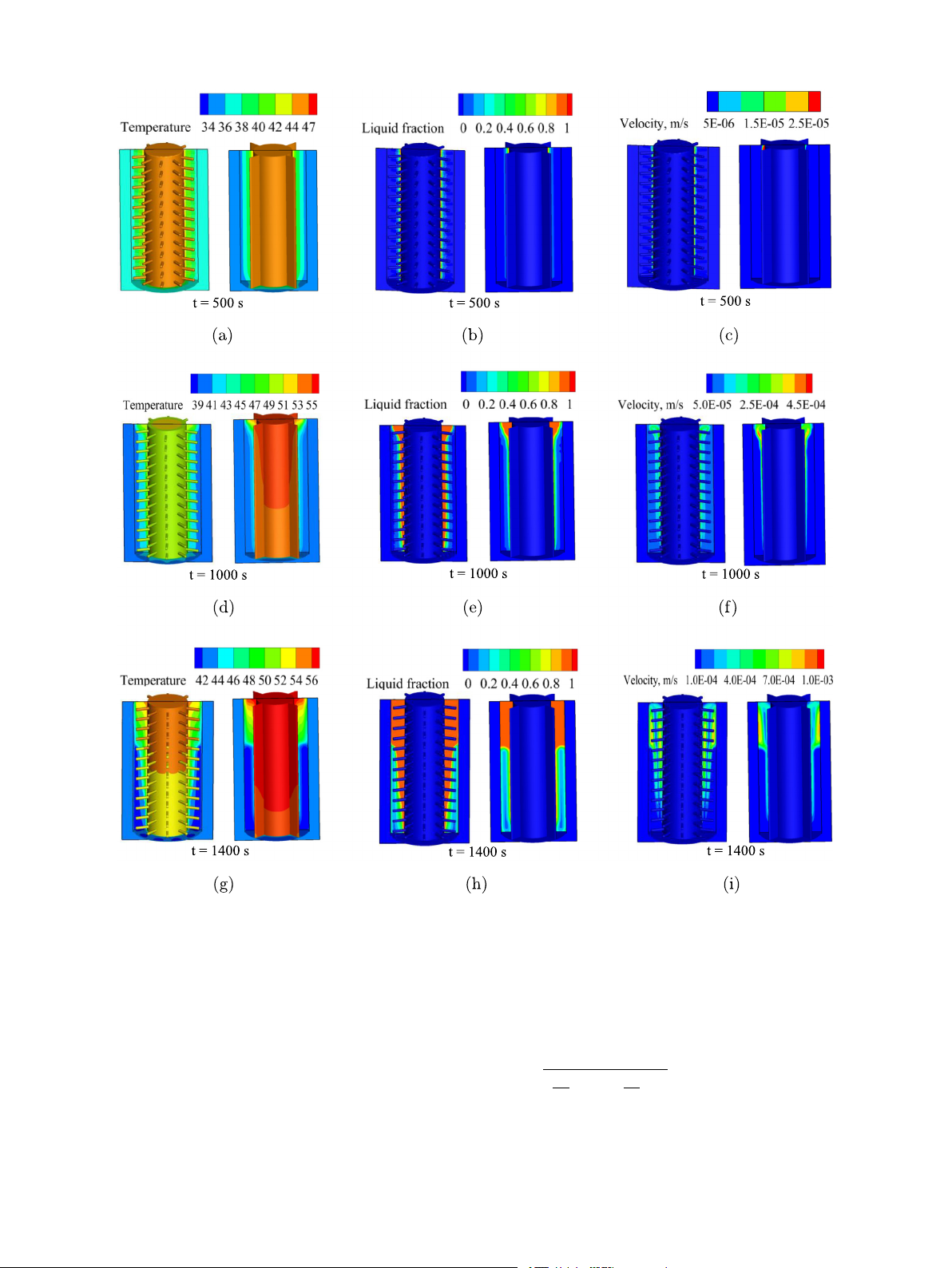

temperature, liquid fraction, and velocity contours. Fig. 9 shows the

temperature, liquid fraction, and velocity contours for these two heat

sinks (heat sink with 130 pin fins and heat sink with 4 plate fins)

at mid plane of the battery. The contours presented in Fig. 9 are at

three different time instants: (1) at the onset of melting, i.e., 𝑡 = 500 s

(Figs. 9(a)–9(c)), (2) during melting, i.e., 𝑡 = 1000 s (Figs. 9(d)–9(f)),

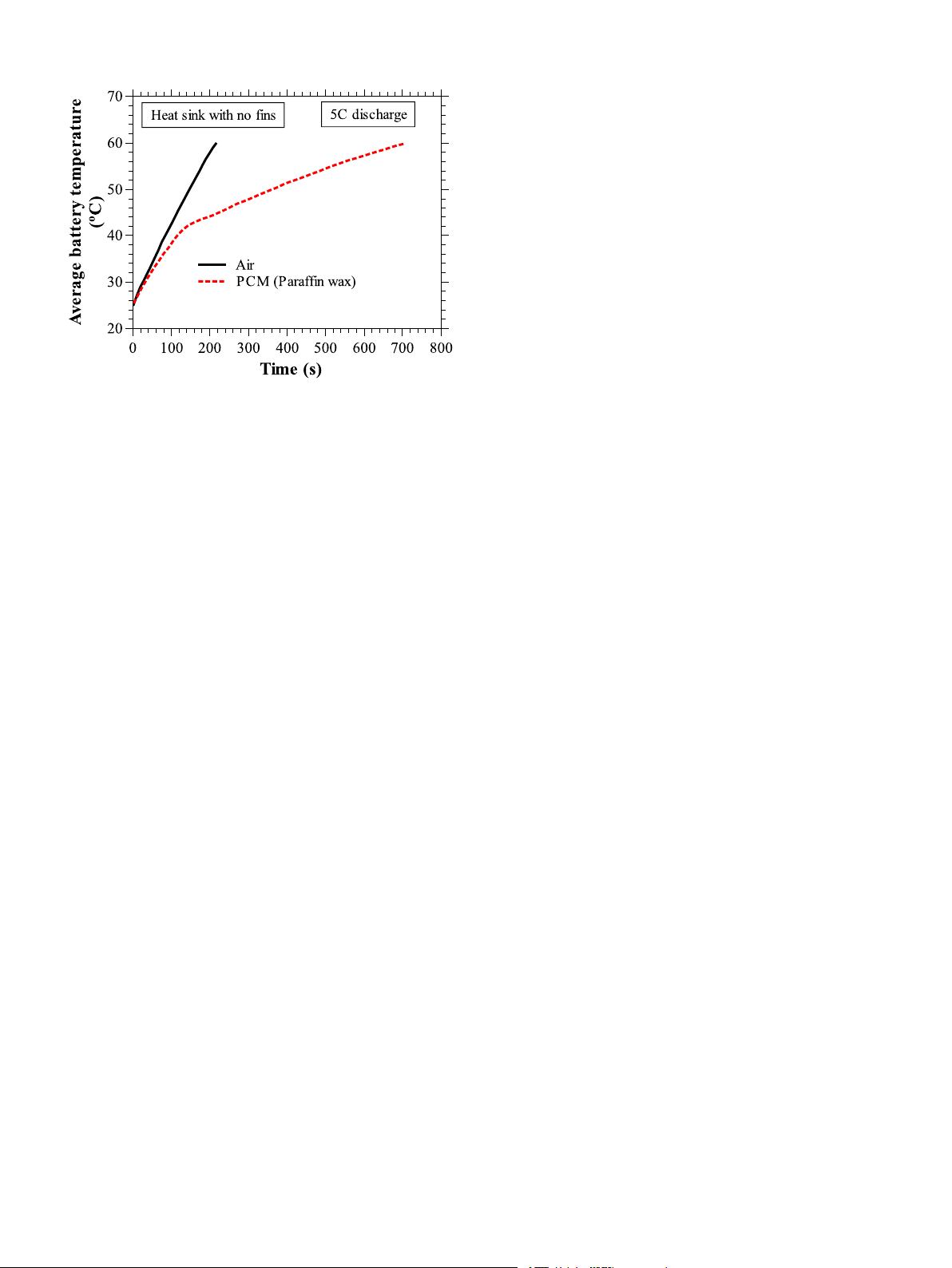

Fig. 7. Comparison of temperature–time histories obtained from plain heat sink, for air

and (3) at the thermal control point of the heat sink with four plate fins,

and PCM as working fluids, when the discharge rate of battery is equal to 5C (constant

i.e., 𝑡 = 1400 s (Figs. 9(g)–9(i)). The thermal control point is the instant heat load of 8 W).

at which the housing of the heat sink reaches the liquidus temperature

(for paraffin wax, it is 44 ◦C) of the PCM, beyond which the heat sink

no longer absorbs heat in the form of latent heat. Despite stronger

conferred. The best heat sink among all the heat sinks is selected and

convection currents in the PCM for the heat sink with four plate fins, the

validated against in-house experiments. Next, the best heat sink is

melt front movement and the temperature distribution in the PCM are

further characterized for various ambient conditions, heat loads, and

more uniform for the heat sink with 130 pin fins than its counterpart

PCMs. Finally, the best heat sink is tested to check its applicability for

due to the dominance of conduction created by pin fins in the domain

thermal management of actual battery with transient heat generation.

of PCM. In the total operation, the heat sink having 130 pin fins records

a 3.3 ◦C lower average temperature than the heat sink with four plate

3.1. Effect of PCM on the thermal performance of the plain heat sink

fins. In addition, the maximum temperature difference on the surface

of the battery for the heat sink with 130 pin fins is confined below

Fig. 7 shows the comparison between the temporal evaluation of the

2.2 ◦C, whereas it is 3.2 ◦C for the heat sink with four plate fins. Given

average surface temperature of the battery for plain heat sink (heat sink

this, the heat sink with 130 fins (fin size: 1 mm) is considered the base

with no fins) filled with air and PCM under 5C discharge rate (constant

heat sink in the upcoming studies to compare the improvement in the

8 W heat load). From the figure, it is clear that the time required to

thermal performance of other heat sinks with pin fins.

reach a Set Point Temperature (SPT) of 60 ◦C is just 214 s when air

is the working fluid, and this gets extended to 716 s when the air is

3.3. Effect of volume fraction of pin fins

replaced with PCM (paraffin wax). Considering the high latent heat

capacity of the PCM, the operating time of 716 s is still very low. The

The volume fraction of the pin fins is varied from the base model

low thermal conductivity of PCM hinders the diffusion of heat, and as

(heat sink with 130 pin fins of size 1 mm) by (i) increasing the fin size

a consequence, only a little heat is absorbed by the PCM, and more

by keeping the number of fins constant (130 fins) and by (ii) increasing

the number of fins by maintaining the fin size constant (fin size: 1 mm).

heat is stored as sensible heat in the battery, which results in a rapid

In the first case, a total of five heat sink configurations are considered

temperature rise of the battery due to minimal latent heat exploitation.

with fin sizes equal to 1.4, 2.0, 3.0, 3.5, and 4.0 mm, resulting fin

Hence, the heat sink reaches the SPT of 60 ◦C reasonably early. Given

volume fractions equal to 4.7, 9.6, 21.6, 29.4, and 38.4%, respectively

this, the use of thermal conductivity enhancers is inevitable for the

(see Fig. 3). In the second case, three heat sink configurations with 200,

effective diffusion of heat into the core of the PCM and better utilization

260, and 390 fins of volume fractions 3.7, 4.8, and 7.2%, respectively,

of the available latent heat in the PCM. are simulated (see Fig. 4).

3.2. Advantage of pin fins over plate fins

3.3.1. Effect of fin size

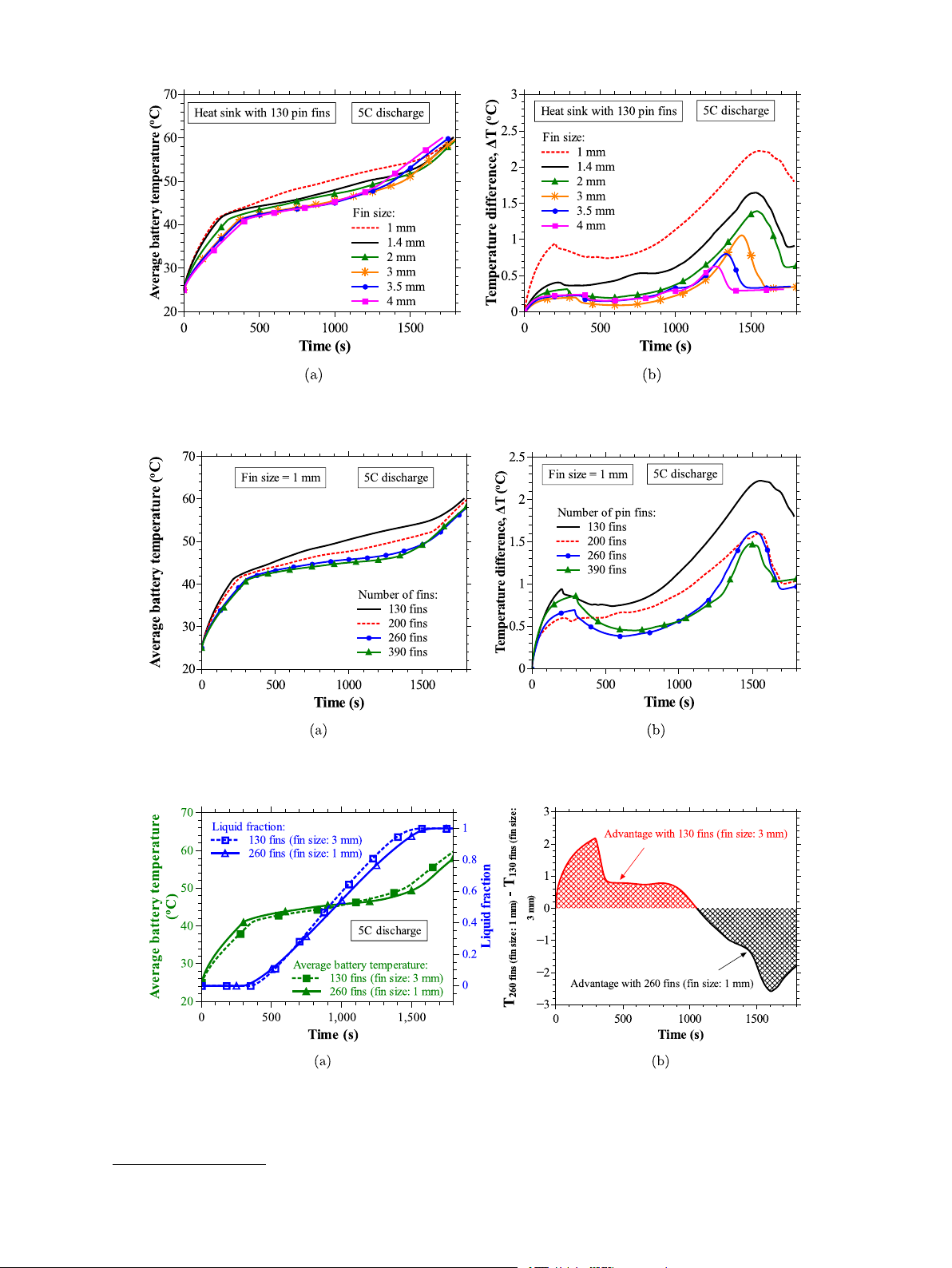

Fig. 10 shows the temporal evaluation of average temperature and

In the previous section (Section 3.1), it was established that the

the maximum temperature difference on the surface of the battery for

TCEs are essential to improve the heat sink performance by creating

five heat sink configurations, each employing 130 pin fins of square

thermal conductive paths for the input heat to diffuse into the core of

cross-section, of size equal to 1.4, 2.0, 3.0, 3.5, and 4.0 mm for a 5C

the PCM. As discussed earlier, the plate-fin heat sink with 2 and 4 fins,

discharge rate. As the fin size increases from 1 to 3 mm, the average

and the pin fin heat sink with 130 fins (see Fig. 2) are designed and sim-

temperature and the temperature difference on the surface of the

ulated to comprehensively understand the thermal regulation capability

battery decreases. After that, the increase in fin size adversely affected

of the heat sink with pin and plate fins. Figs. 8(a) and 8(b) compare

the thermal regulation capability by recording lower operating times

the numerical results for the maximum temperature difference and the

and higher thermal gradients compared to a heat sink with a 3 mm

average battery temperature on the battery surface, respectively, for the

fin size (see Figs. 10(a) and 10(b)). This is because the improvement

heat sinks with 2 and 4 plate fins and the heat sink with 130 pin fins.

in the thermal conductivity overcomes the reduction in the available

The point to be noted here is that the volume fraction of these three

latent heat of the composite PCM (combination of fins and PCM) till

heat sinks is equal to 2.4%. Though the volume fraction of fins is the

fin size increases from 1 to 3 mm, which means the positive impact

same for the heat sinks with 2 and 4 plate fins, the latter shows superior

of the increase in effective thermal conductivity of PCM dominates the

performance over the former due to its high value of 𝛼. Despite having

negative effect of reduction in its volume. Based on these results, the

the same 𝜙 and 𝛼, it can be seen from Fig. 8 that the heat sink with 130

heat sink with a fin size of 3 mm is considered optimum in regulating

pin fins outperforms the heat sinks with 2 and 4 plate fins throughout

thermal excursions during high heat generation rates from the battery. 9 R. Akula et al.

Applied Thermal Engineering 248 (2024) 123146

Fig. 8. Comparison of (a) the maximum temperature difference on the surface of the battery, and (b) average surface temperature–time and liquid fraction-time histories for heat

sink configurations with 2 and 4 plate fins, and 130 pin fins for 5C discharge rate (constant heat load of 8 W) of the battery.

3.3.2. Effect of fin number

battery. However, it also reduces the space available to accommodate

In the previous section (Section 3.3.1), the effect of increase in

the PCM in the heat sink, resulting in less latent heat availability. As a

volume fraction due to increase in fin size was studied in detail. This

result, the heat sink with 130 fins (fin size: 3 mm) exhibits superior and

section presents an elaborate discussion on the effect of increase in

poor performance during the initial and final stages of the operation,

fin volume fraction by increase in the number of fins. Figs. 11(a) and

respectively, over the heat sink with 260 fins (fin size: 1 mm) (see

11(b) show the time-varying responses of average temperature and

Fig. 12(b)). Apart from thermal performance, the weight of the heat

the maximum temperature difference on the surface of the battery,

sink also plays a significant role in choosing the best heat sink. It is

respectively, for the heat sinks with 130 (base case), 200, 260, and

observed from the weight calculations that the heat sink with 130 fins

390 fins. Please refer to Section 2.1 for a detailed discussion on the

(fin size: 3 mm) is 12.2% more weighed than its counterpart, i.e., the

design and dimensions of the heat sink having 200, 260, and 390 fins.

heat sink with 260 fins (fin size: 1 mm). Considering the thermal

The volume fractions offered by these heat sinks with the number of

performance and weight metrics, the heat sink with 260 fins, each

fins equal to 200, 260, and 390 are 3.7%, 4.8%, and 7.2%, respec-

fin of size 1 mm, is finalized as the best heat sink among all heat

tively. One can assess from Figs. 11(a) and 11(b) that the thermal

sinks considered in the present study. To further explore the thermal

performance of the heat sinks increases with an increase in fin number.

behavior of the best heat sink (i.e., 260 fins with each fin size equal

This is because of increase in locations on the battery to dissipate heat

to 1 mm) for various ambient conditions, heat loads, and PCMs, the

uniformly into the overall volume of the PCM resulted by the increase

remaining heat sinks considered in the present study are omitted from

in fin number. However, the thermal performance of the heat sink is

analysis in the ensuing sections.

improved marginally beyond 260 pin fins, which means, doubling (260

fins) and tripling (390 fins) the fins from the base heat sink (130 fins)

3.4. Experimental validation of the best performing heat sink

showed similar results because the advantage of uniform diffusion of

heat with the number of fins beyond 260 is counterbalanced by the

In-house experiments are conducted on the best-performing heat

disadvantage of reduction in the latent heat of the PCM. Despite having

sink (260 pin fin heat sink with each fin of size 1 mm) to validate the

a little advantage in thermal regulation with 390 pin fins, the heat sink

above numerical results for paraffin wax at 5C discharge (constant heat

with 260 fins can be considered as the better choice by keeping the

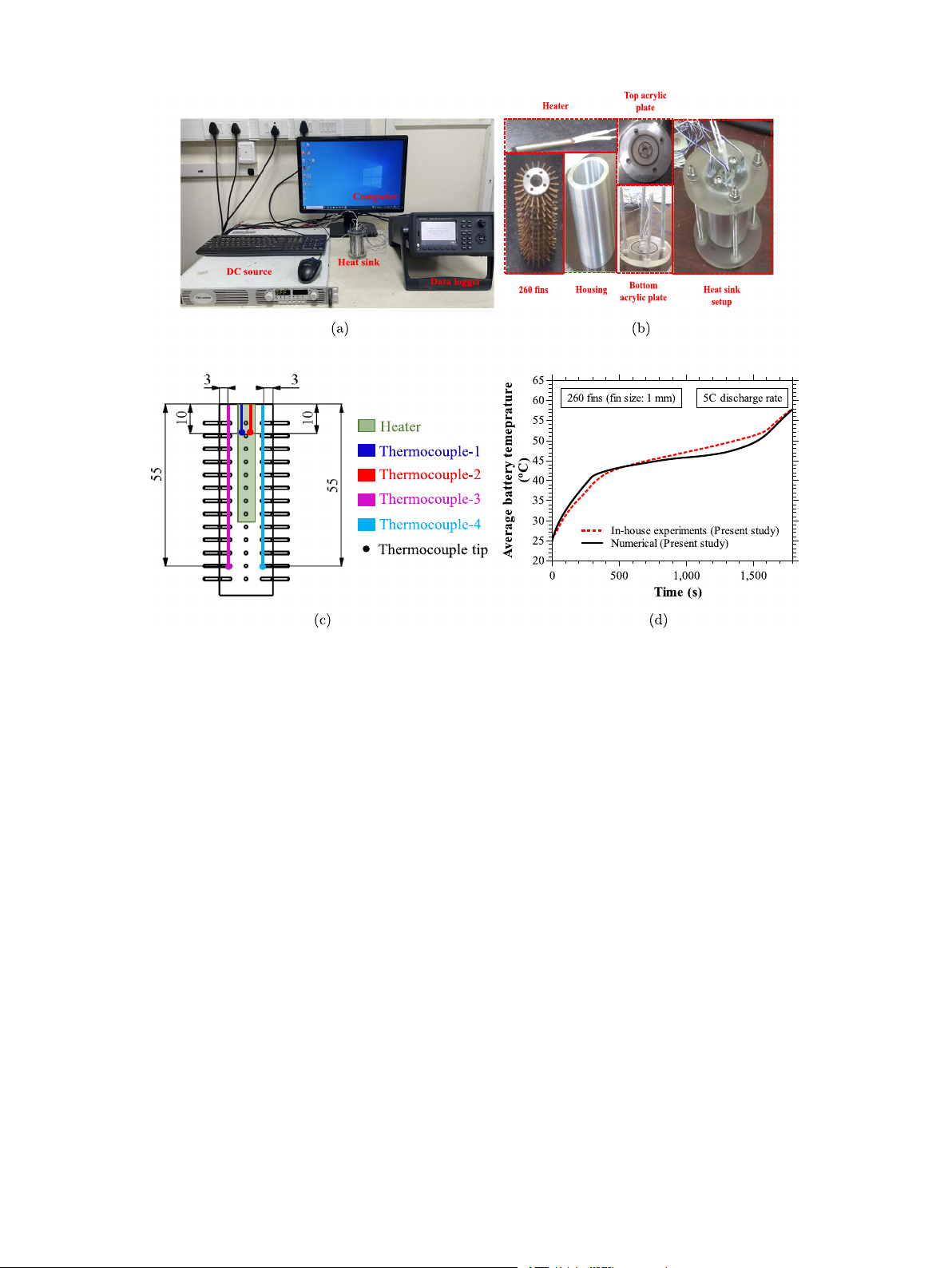

load of 8 W). Figs. 13(a), 13(b), and 13(c) show the experimental setup,

thermal performance, weight, and intricacy involved in fabricating the

parts of the 260 pin fin heat sink, and locations of the thermocouples heat sinks as the metrics.

inserted in the heat sink, respectively. The heat sink consists of a rod-

In Section 3.3.1, the heat sink with 130 fins (each fin of size 3 mm)

type heater (diameter = 6.5 mm, length = 40 mm), an aluminum rod

turned out to be the best heat sink when the thermal performances

having the same dimensions as 18650 battery (diameter = 18 mm,

of the heat sinks with different fin sizes were compared. Based on

length = 65 mm) with 260 copper fins (each fin dimension = 1 ×

the results presented in Section 3.3.2, it is seen that the heat sink

1 × 6 mm3) brazed on its curved surface, a cylindrical housing (inner

with 260 fins (each fin of size 1 mm) results out to be the best heat

diameter = 31 mm, thickness = 5 mm, height = 65 mm), and two

sink when the thermal performance of heat sinks with different fin

acrylic plates. A cylindrical groove of dimensions equal to the heater is

numbers was compared. Fig. 12(a) compares the thermal performance

made at the center of the aluminum rod from the top to accommodate

of these two best heat sinks, i.e., heat sink with 130 fins (fin size:

the heater. The heater and aluminum rod combination replicates the

3 mm) and heat sink with 260 fins (fin size: 1 mm), on the metric of

cylindrical 18650 Li-ion battery with heat generation. Four holes are

average battery temperature, for 5C discharge, to finalize the one best

made in the aluminum rod, two at a depth of 55 mm and the other two

heat sink. From Fig. 12(a), it is clear that a heat sink with 130 fins

at a depth of 10 mm from the top, to insert four T-type thermocouples

(fin size: 3 mm) records lower average battery temperature during the

to measure the temporal evaluation of average temperature (average of

conduction-dominated phase (pre-melting and initial phase of melting).

four thermocouple readings at a instant) and the temperature difference

During later phases of melting and post-melting, the average battery

(average of first and second thermocouple readings at a instant- average

temperature obtained with a heat sink having 130 fins (fin size: 3 mm)

of third and fourth thermocouple readings at a instant) in the battery

surpasses the heat sink with 260 fins (fin size: 1 mm). The volume

(see Fig. 13(c)). The thermocouples are calibrated, and the uncertainty

fractions of fins in the heat sink with 130 fins (fin size: 3 mm) and

in the temperature measurements is measured to be within ±0.25 ◦C.

260 fins (fin size: 1 mm) are 21.6 and 4.7%, respectively. A higher

The battery with thermocouples and housing is placed over the bottom

volume fraction of fins helps to diffuse more heat into the PCM from the

acrylic plate and sealed with top another acrylic plate, and the whole 10 R. Akula et al.

Applied Thermal Engineering 248 (2024) 123146

Fig. 9. The contours of temperature (a, d, and g) in ◦C, liquid fraction (b, e, and h), and velocity (c, f, and i) in m/s on the middle plane at three time instants: (i) onset of

melting, i.e., 𝑡 = 500 s (a, b, c), (ii) during melting, i.e., 𝑡 = 1000 s (d, e, f), and (iii) at the thermal control point.i.e, 𝑡 = 1400 s (g, h, i).

setup is tightened with a nut and bolt locking system. Initially, the

and voltage in the DC power leads to uncertainty in the heat generation

amount of PCM (in grams) required to fill the heat sink cavity is

from the heater. The propagation of this error in the fundamental

calculated from the mass, density, and volume relation. The required

quantities (current and voltage) to the derived quantity (power) can

amount of solid PCM is taken into a beaker, and then, it is heated

be calculated using the method of propagation of errors using the

to 80 ◦C using a temperature water bath. The melted PCM in the

beaker is poured into the heat sink through a hole provided in the

following equation (see Eq. (18)).

top acrylic plate using a glass funnel. The PCM is filled up to 95% √( )2 ( )2

volume available in the heat sink. The remaining 5% of the volume is 𝜕𝑃 𝜕𝑃 𝜎𝑃 = ± 𝜎𝑉 + 𝜎𝐼 (18)

left out for thermal expansion of the PCM during melting, as its thermal 𝜕𝑉 𝜕𝐼

expansion coefficient is 0.00076 K−1 [39]. The heater placed in the

In the above equation, 𝜎

aluminum rod is connected to the DC power supply (TDK Lambda DC

𝑉 and 𝜎𝐼 represent uncertainties in voltage and

current, which are observed to be ± 0.1 V and ± 0.01 A, respectively.

source) to generate the required heat. The thermocouples are connected

to DAQ (Agilent 34970 A), and DAQ is connected to a computer to

The voltage and current values set in the DC power source to obtain

measure temperatures for every interval of 5 s. The resolution of current

8 W power output are equal to 12.5 V and 0.64 A. The uncertainty in 11 R. Akula et al.

Applied Thermal Engineering 248 (2024) 123146

Fig. 10. Comparison of (a) average temperature–time history, (b) maximum temperature difference-time history on the surface of battery for heat sink configurations having 130

pin fins with each fin size equal to 1, 1.4, 2, 3, 3.5, and 4 mm.

Fig. 11. Comparison of (a) average temperature–time history, (b) maximum temperature difference-time history on the surface of the battery for heat sink configurations having

number of fins equal to 130, 200, 260, and 390 with each fin of size 1 mm.

Fig. 12. Comparison of (a) average surface temperature–time history of the battery for heat sinks with 260 fins (fin size: 1 mm) and 130 fins (fin size: 3 mm) and (b) advantage

of one heat sink over other during complete operation in terms of temperature regulation.

the power supply is calculated using Eq. (18), as follows.

The uncertainty in the power supply is calculated to be ±0.14 W for √

a nominal power of 8 W. The percentage of uncertainty is just 1.75% 𝜎𝑃 = ±

(0.64 × 0.1)2 + (12.5 × 0.01)2 = ±0.14 W (19)

and can be ignored. Each experiment is conducted twice to check the 12 R. Akula et al.

Applied Thermal Engineering 248 (2024) 123146

Fig. 13. Figure showing (a) photograph of the experimental setup, (b) parts of the 260 pin fin heat sink used, (c) location of the thermocouple positions in the battery, and (b)

average surface temperature–time histories for heat sink with 260 pin fins (fin size: 1 mm) obtained from in-house experiments and numerical simulations for 5C discharge rate.

repeatability. In each experiment, the initial and ambient tempera-

on the heat sink is investigated numerically. The initial temperatures

tures are almost constant and equal 25 ± 1 ◦C. Fig. 13(d) compares

of the heat sink, PCM, and battery are set at the respective ambient

the temperature–time histories of the heat sink, with 260 fins (fin

temperatures (either 15, 25, or 35 ◦C) when studying the effect of

size: 1 mm) obtained from both in-house experiments and numerical

ambient temperature on the thermal performance of the heat sink.

simulations, for paraffin wax as PCM, when subject to a discharge

The average temperature–time histories of the battery and the liquid

rate of 5C. Fig. 13(d) clearly shows that the numerical results are in

fraction-time histories of the PCM for ambient temperatures 15, 25,

good agreement with the experimental results, within the maximum

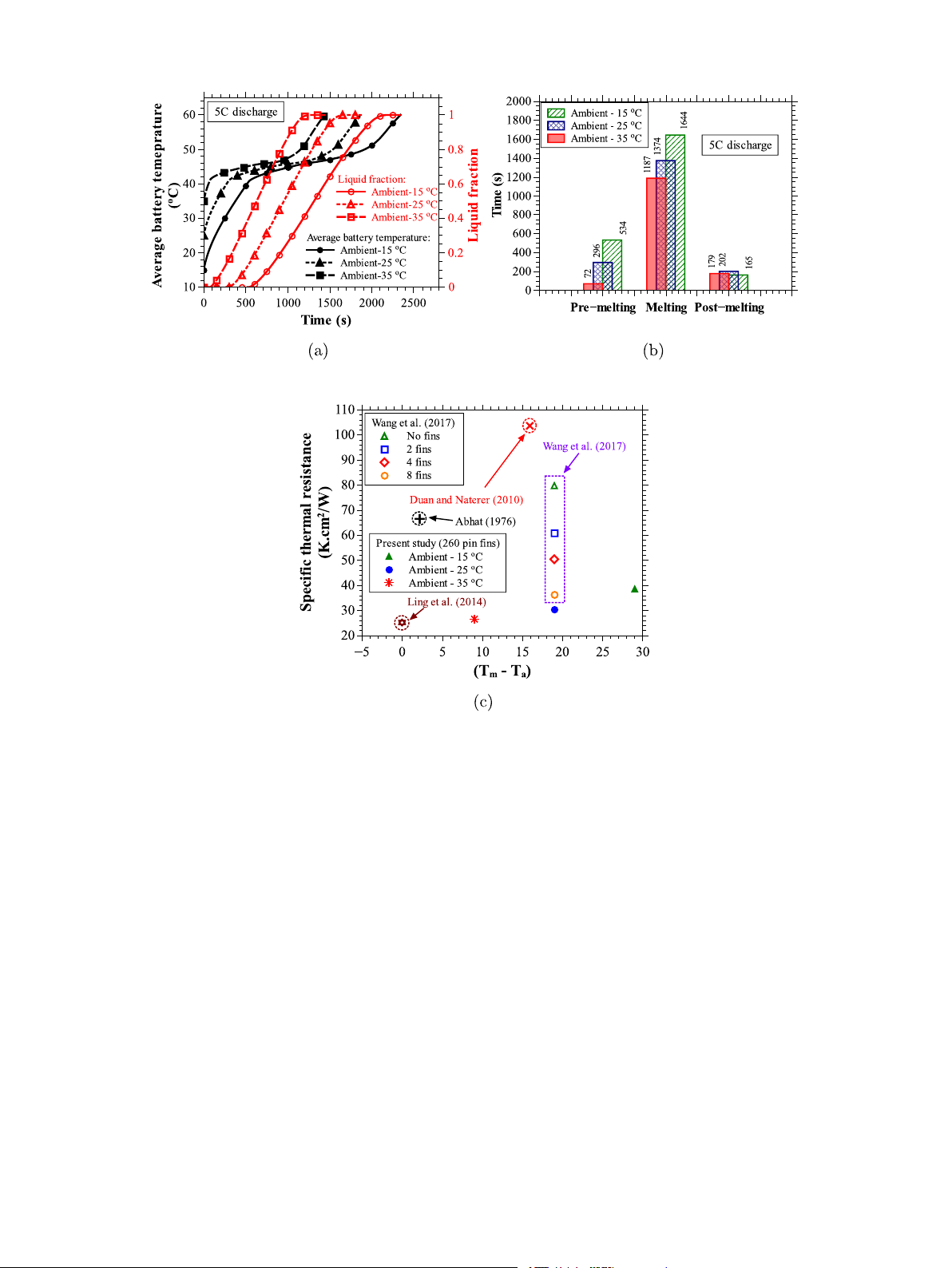

and 35 ◦C are depicted in Fig. 14(a). From intuition, one can easily

discrepancy of 5%. The deviation between the experimental and nu-

understand that the heat sink with lower ambient temperature takes

merical results could be attributed to the assumptions employed in the

longer to reach the set point temperature consequent upon higher

numerical simulations including constant thermophysical properties of

temperature difference between the initial and set point temperatures.

the PCM during phase change, and omitting contact thermal resistance

Fig. 14(b) shows the durations recorded for the pre-melting, phase and radiation heat losses.

transition, and post-melting phases when the ambient temperatures are

15, 25, and 35 ◦C. An interesting point to be noted here is that the effect

3.5. Thermal characterization of 260 pin fin heat sink

of ambient temperature is more pronounced on the operating time

during pre-melting phase followed by the melting and post-melting

From above discussion, it is understood that the heat sink with 260-

phases. The amount of time taken by the heat sink to complete the

pin fins outperforms all other heat sink configurations. This section

pre-melting phase is reduced by 86.5% when the ambient temperature

reports the results of parametric studies, conducted numerically, on

is increased from 15 ◦C to 35 ◦C. This is primarily because of equating

the 260 pin fin heat sink for ambient temperatures 15 and 35 ◦C, for

the initial and ambient temperatures. The heat sink takes longer time to

different PCMs, and for discharge rates 3C and 4C (constant heat loads

reach the melting point temperature of the PCM (41 ◦C) for lower initial 4 and 6 W).

temperature, i.e., 15 ◦C compared to the higher initial temperatures,

i.e., 25 and 35 ◦C. During the melting and post melting phases, the

3.5.1. Effect of different ambient conditions

respective starting temperatures of the heat sink for the three ambient

Electric vehicles operate in different geographic regions and differ-

temperatures is almost the same. However, the influence of ambient

ent seasons. As a result, the ambient conditions are subject to change

temperatures is more pronounced on operating time during melting

both geographically and seasonally. The battery pack should have a

phase (a reduction of 27.8% in operating time when the ambient tem-

stable performance regardless of the ambient conditions. In all the

perature is increased from 15 to 25 ◦C) than during post-melting phase.

above comparison studies, the ambient temperature is fixed at 25 ◦C.

This could be attributed to the presence of unmelted PCM near the walls

In this section, the effect of ambient temperatures (15 and 35 ◦C)

of housing at ambient temperature equal to 15 ◦C, which potentially 13 R. Akula et al.

Applied Thermal Engineering 248 (2024) 123146

delays the completion of phase change. During post melting phase,

in the thermal resistance. Nevertheless, the thermal resistances at the

the heat sink acts as a insulator due to lower thermal conductivity of

thermal control point of Eicosane, Paraffin, and Tetracosane are equal

the liquid PCM and absence of unmelted PCM. As a result, the surface

to 28, 30.4, and 31.1 K cm2∕W, respectively, which are observed to be

temperatures of the battery are minimally unaffected by the change in

lower than the thermal resistance offered by the heat sinks considered ambient temperatures.

in the studies of Sun et al. [37], Zare et al. [38], and Zhang et al.

Introducing the concept of thermal resistance in a heat sink is an en-

[40]. Sun et al. [37] introduced a novel design consist of longitudinal

gineering approach to evaluate and compare the thermal performance

fins and cylindrical rings for heat transfer enhancement. Zare et al. [38]

of the present heat sink against other heat sinks in literature [35,60].

proposed an innovative combination of internal and external fins to

In the present study, the thermal resistance of the heat sink is defined

create PCM silos around the battery surface. Zhang et al. [40] tested

at the thermal control point using the following equation [35].

nine new branch fin designs to solve the problem of the lightweight ( )

design of metal fins and to strengthen the heat transfer. Fig. 15(c)

𝑇𝐶 − 𝑇𝑚 𝐴𝑏 𝑅

compares the thermal resistance of the best designs in each respective 𝐶𝑚 = (20) 𝑞

studies of Sun et al. [37], Zare et al. [38], and Zhang et al. [40] are

In the above equation, 𝑇𝐶 represents the battery temperature at the

calculated using Eq. (20) and compared against the thermal resistance

thermal control point, and 𝑇𝑚, 𝐴𝑏, and 𝑞 are the liquidus temperature

offered by the present heat sink. From the figure, it is clear that the best

of the PCM, surface area of the battery, and heat load, respectively.

heat sink obtained in the present study offers lower thermal resistance

Fig. 14(c) shows the comparison of specific thermal resistance offered

compared to other heat sinks in literature.

by the present heat sink and the other heat sinks reported by Wang

In any BTMS, the active cooling systems such as air/water cooling

et al. [35], Ling et al. [48], Duan and Naterer [61], and Abhat [62] at

must act as the primary cooling system due to incapability of passive

the thermal control point for different ambient temperatures. The figure

cooling systems including PCM based heat sinks in handling continuous

shows that the heat sink considered in the present study records lower

heat loads with high magnitudes. Nonetheless, the passive cooling

thermal resistance than other heat sinks reported in the literature.

systems can be integrated with active cooling systems to take care of

Further, it is also observed that the thermal resistance of the heat

the extra heat left out by the primary cooling system such that the

sink considered in the present study decreases with an increase in the

size and external power consumption of the primary cooling system

ambient temperature. This leads to an advantage of exhibiting good

can be reduced. The present study focuses only on the characterization

thermal response by the present heat sink even at higher ambient

of PCM based heat sinks during melting in the absence of active temperatures.

cooling system. Further thermal characterization of these heat sinks

during solidification of PCM in the absence of active cooling system is

3.5.2. Effect of different phase change materials

absolutely necessary to finalize the best PCM. From the present study,

The heat sink with 260 fins (fin size: 1 mm) obtained in the above

it is observed that the PCM with a low melting point temperature

discussion is also tested for other phase change materials, namely

is preferred during melting in the absence of active cooling system.

Eicosane and Tetracosane. The thermophysical properties of these

However, in the presence of an active cooling system, the thermal

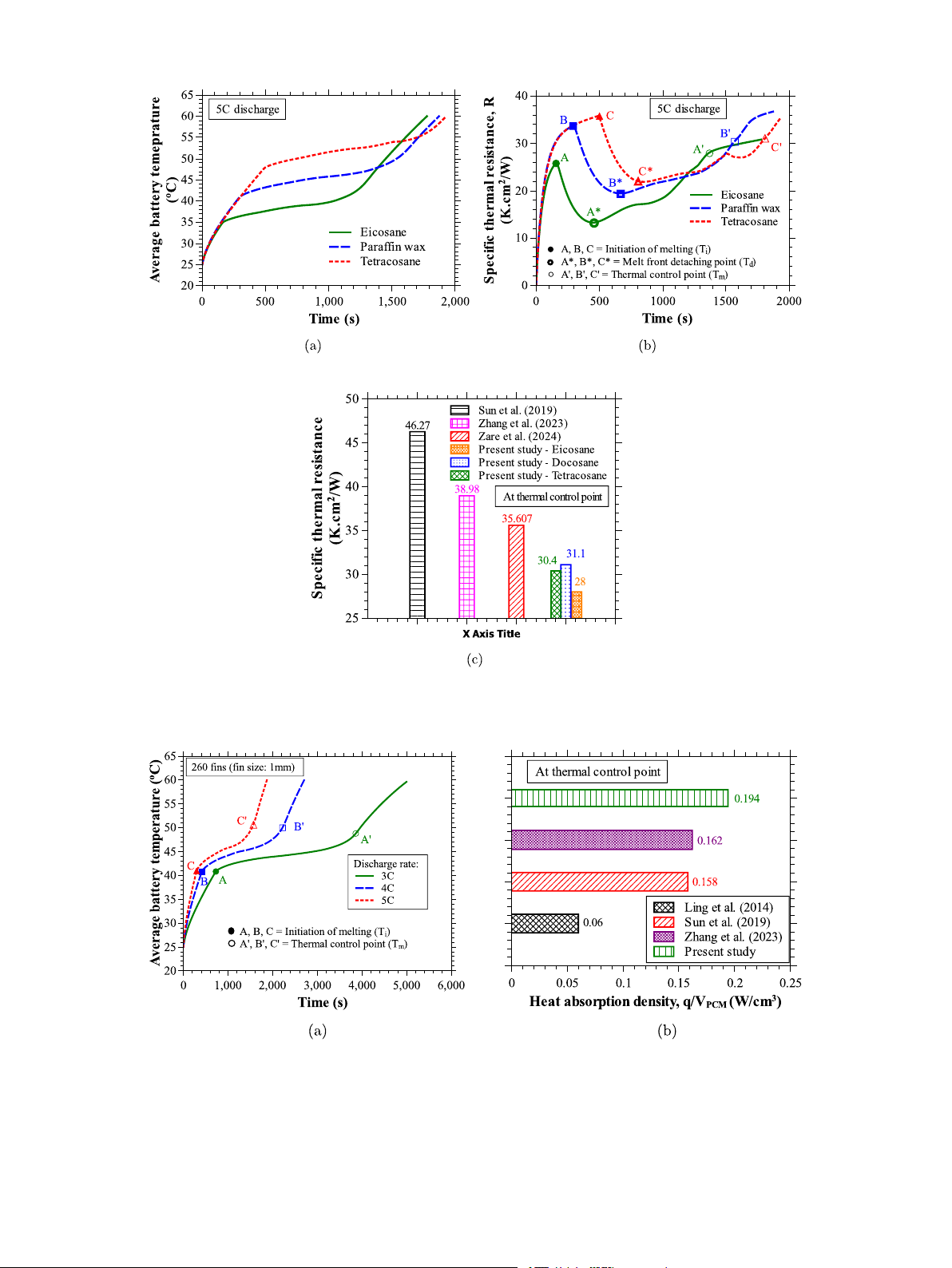

PCMs are reported in Table 3. Fig. 15(a) compares the average surface

conditions might differ, and a PCM with low melting point temperature

temperature–time history of the battery for three PCMs, Eicosane, might not be optimal.

Paraffin wax, and Tetracosane, for a 5C discharge rate. These numerical

simulations are conducted at initial and ambient temperatures of 25 ◦C.

3.5.3. Effect of different heat loads

From Fig. 15(a), it is clear that the thermal responses of the heat

So far, in the present study, a constant heat load of 8 W was

sinks are aligned to the respective melting point temperatures of the

considered as a heat generation from a Panasonic NCR18650BD battery

PCM. Despite having different phase change temperatures, the heat sink

at a 5C discharge rate. In the present section, the thermal behavior of

records almost the same phase change durations and operating times

the best heat sink obtained above (heat sink having 260 fins with 1 mm

(time to reach set point temperature) due to similar thermophysical

fin size) is characterized by other discharge rates, namely 3C (constant

properties offered by these three PCMs. In addition to the average

heat load of 4 W) and 4C (constant heat load of 6 W), and its thermal

temperature–time histories, the maximum temperature and tempera-

performance is compared against 5C discharge (constant heat load of

ture difference-time histories on the battery surface are also observed. 8 W).

The trend of maximum and average temperatures is almost the same

The average surface temperature–time histories obtained numeri-

and the difference between them is just 2 ◦C for all the respective PCMs.

cally from the heat sink with 260 fins of size 1 mm for discharge

Further, the maximum temperature difference is also confined below

rates 3, 4, and 5C are shown in Fig. 16(a). The heat sink registers

2 ◦C with this heat sink employing 260 pin fins.

lower operating times (time to reach set point temperature) for higher

The temperature plateaus observed at the onset of melting and the

discharge rates and vice versa. However, the heat sink attains the

thermal control point are almost equal to the solidus and liquid tem-

same battery temperatures at the initiation of melting and thermal

peratures, respectively, for all PCMs. The elimination of superheating

control points for the three discharge rates considered, which signifies

and the quick response of the heat sink can be attributed to the lower

the capability of swift response of the proposed heat sink to result

thermal resistance offered by the heat sink. The quantified thermal

in higher operating times even for higher discharge rates. The same

resistance of the heat sink can be seen from the plot, which depicts

phenomenon can be further analyzed using a parameter termed heat

the thermal resistance variation with time for the three PCMs (see

absorption density, which is defined as the ratio of heat load (𝑞) to

Fig. 15(b)). The points A, A*, A’, and B, B*, B’, and C, C*, C’ represent

the volume of PCM (𝑉𝑃 𝐶𝑀 ) considered in the heat sink. Heat sinks

onset melting, melt front detach point, and thermal control point for

with higher heat absorption density are preferred in electric vehicle

Eicosane, Paraffin, and Tetracosane, respectively. The melt front detach

applications as they yield high thermal performance even for small

point is the time instant at which the overall battery surface is no longer

amounts of PCM. The characteristic of high heat absorption density

in contact with the melt front of the PCM. The thermal resistance of

eliminates the space constraint and reduces the chances of the cooling

the heat sink for all the PCMs is the lowest at the melt front detach

system being overweighted. Fig. 16(b) compares the heat absorption

point compared to the initiation of melting and thermal control points

density of the present heat sink against the heat sinks proposed by Sun

because of lower battery temperature due to the melt front near the

et al. [37], Zhang et al. [40], and Ling et al. [48]. From the figure, it

battery surface. As the melt front moves away from the battery surface

is clear that the heat sink considered in the present study offers higher

post melt front detach point, the temperature difference between the

heat absorption density over other heat sinks in literature to reach the

battery and the remaining system rises. Consequently, there is a rise thermal control point. 14 R. Akula et al.

Applied Thermal Engineering 248 (2024) 123146

Fig. 14. Comparison of (a) average battery temperature–time histories and liquid fraction-time histories, (b) durations of pre-melting, phase transition, and post-melting, and c)

thermal resistance against heat sinks reported in literature, for 260 pin fin heat sink at ambient temperatures 15, 25, and 35 ◦C.

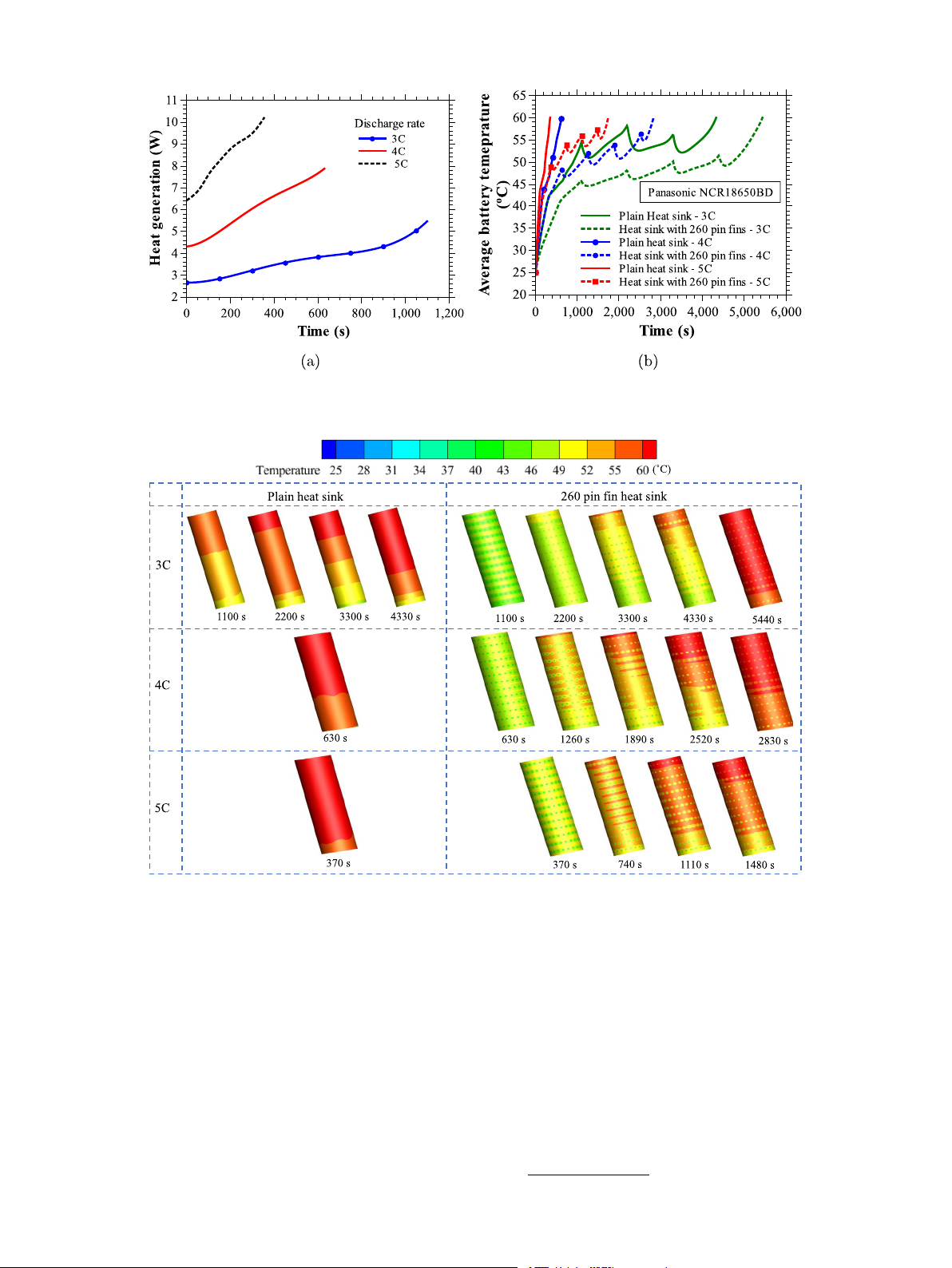

3.6. Effect of 260 pin fin heat sink on the real battery

numerical methodology using the Newman P2D model, please refer to

our earlier work [15]. Fig. 17(a) shows the temporal variation of the

Till now, a simulated battery made of aluminum with a constant

heat generation calculated using the Newman P2D model for 3, 4, and

heat generation assumption is considered to mimic the thermal behav-

5C discharge rates. The calculated time-varying heat generation has

ior of a real battery. In addition, various heat sinks are tested for the

been given as a volumetric source term in the composite cylindrical rod

thermal management of this simulated battery at 3, 4, and 5C discharge

with dimensions and thermophysical properties the same as that of the

rates. In this section, the best heat sink, i.e., the heat sink with 260 pin

Panasonic NCR18650BD battery. The cylindrical composite material

fins, obtained from the above thermal management studies conducted

with variable heat generation is assumed as the real battery, and its

on the simulated battery is further characterized numerically to study

thermal management is attempted with a 260-pin fin heat sink in this

its thermal regulation capability when the simulated battery is replaced section.

with a real battery. Furthermore, an economic analysis is also presented

The operating durations of the Panasonic NCR18650BD battery for

at the end of this section to discuss the practical feasibility of employing

3, 4, and 5C discharge rates are 1760, 630, and 370 s, respectively.

260 pin fin heat sink in the EVs.

If the temporal evolution of the average temperature on this battery

surface with and without 260 pin fins does not reach the SPT of 60 ◦C

3.6.1. Thermal performance evaluation

An actual Panasonic NCR18650BD battery, with thermophysical

at the end of any discharge rate, the simulation is continued with

properties reported in Table 2, is considered, and the experiments are

the same discharge rate in a loop. The thermal performance of the

conducted to identify its voltage and temperature–time histories for