Preview text:

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/363148568

The Economics of Consumer Credit on an E-Commerce Platform Preprint · August 2022 CITATIONS READS 0 43 1 author: Ji Huang

The Chinese University of Hong Kong

9 PUBLICATIONS48 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

E-Commerce Consumer Lending View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Ji Huang on 31 August 2022.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

The Economics of Consumer Credit on an E-Commerce Platform Ji Huang∗

The Chinese University of Hong Kong August 31, 2022 Abstract

Digitalization nurtured the integration of E-commerce, payment, and consumer lend-

ing. Point-of-Sale financing offered on E-commerce platforms (e.g., “Buy Now, Pay

Later”) poses a new challenge for financial regulators. This paper analyzes E-commerce

consumer credit’s economics and welfare implications through a stylized model. First,

if they access the same technology, platforms provide more credit than banks because

of the synergy between E-commerce and consumer lending. Second, E-commerce con-

sumer credit increases platforms’ market power and efficiency losses. Third, E-commerce

consumer credit amplifies the credit channel of monetary policy transmission. Fourth,

platforms lend more excessively than banks when consumers are present biased.

Keywords: consumer credit, E-commerce platform, economy of scope, BNPL, FinTech

∗I would like to thank useful comments from Markus Brunnermeier, Chong Huang (discussant), Liang Lu,

Yang K. Lu, Jinfei Sheng, Michael Song, and Wei Xiong. Jiang Siqi and Zheng Zehao offered superb research

assistance. Contact Details: 9/F Esther Lee Building, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong

Kong, China. Email:jihuang@cuhk.edu.hk. 1 Introduction

Chinese regulators halted the highly anticipated IPO of Ant Group in November 2020 due to the

concern of financial instability given the FinTech company’s fast expansion. A few days before

the incident at the 2020 Bund Summit, Jack Ma, the founder of the E-commerce platform

Alibaba Group and Ant Group, openly criticized the suitability of the current regulatory

framework Basel Accords for China’s financial system on the ground of the revolutionary

modern technology for finance (i.e., FinTech).

The Chinese Billionaire was right! The Basel Accords only address regulatory issues with

financial services undertaken by standalone banks. Modern Tech companies, however, have

integrated the function of consumer lending with E-commerce and payment to various degrees.

Ant Group is a “division” of the Alibaba E-commerce conglomerate. The popular “Buy Now,

Pay Later” (BNPL) products, Point-of-Sale (POS) installment consumer loans, also serve as

a means of payment that retailers widely accept across countries. The consumer lending of a

standalone bank lacks the synergy between that of E-commerce platforms and other lines of

their businesses. This paper will analyze the economics and welfare implications of E-commerce

platforms’ consumer lending, focusing on the return to scope.

This paper considers a three-period general equilibrium model with an E-commerce plat-

form. The platform provides the E-commerce service in the first two periods. Firms choose

to sell products in either the physical or E-commerce markets or stay inactive. The advantage

of E-commerce is to lower the operating cost of a firm. There are two types of agents: savers

and borrowers. In the first two periods, savers enjoy high labor wages, and borrowers have

high labor income in the third period. A standalone bank and the platform can conduct the

financial intermediation service. The two have the same technology and charge the same net interest spread.

The platform charges fees to firms that sell products in the platform market. Due to

purchasing habits or the lack of confidence in virtual stores, the platform offers consumer

rebates to maintain the demand and clear the E-commerce market. Alternatively, the platform

could increase demand by providing POS financing as borrowers face binding credit constraints.

The substitution between consumer rebate (price instrument) and consumer credit (quantity

instrument) is the core trade-off of the platform optimization problem.

If the bank does not supply sufficient consumer credit, the E-commerce platform is inclined

to provide more consumer credit to exploit the economy of scope. When borrowers’ credit con-

straints are very tight, offering more consumer credit is more effective in increasing the platform

demand than consumer rebates. Therefore, the platform finds it more cost-efficient to provide

consumer credit and cut consumer rebates. Note that I assume the standalone bank accesses

the same intermediation technology as the platform. One insight of the paper is that the

often-cited FinTech or Big Data is not necessarily the only reason that E-commerce platforms

provide more consumer credit than standalone banks. The return to scope could also drive the 2

E-commerce provider to incur more costs to verify consumers’ pledgeable incomes and supply

more credit. This economy-of-scope motive suggests that the E-commerce platform could play

a more critical role than banks if a government intends to promote financial inclusion.

E-commerce consumer credit increases the E-commerce platform’s market power and the

efficiency loss with E-commerce services. Since borrowers face binding credit constraints, they

become less price-sensitive when the platform provides more credit. Therefore, the price (i.e.,

consumer rebates) elasticity goes down if the supply of E-commerce consumer credit increases.

On the firm side, the increase in the credit-driven demand for platform products also lowers

firms’ platform fee sensitivity. Overall, the paper highlights that along with the rise in E-

commerce consumer credit, the price elasticities on both the merchant and the customer sides

decline, and the deadweight loss with E-commerce rises.

The supply of E-commerce consumer credit has positive externalities that standalone banks

do not internalize. The enhanced demand for the platform products makes more firms switch

to the E-commerce market and economize on their operating costs at the intensive margin.

At the extensive margin, more firms survive due to the reduced overhead expenses in the E-

commerce environment. As a general equilibrium consequence, the labor market improves,

and households inside and outside the E-commerce system enjoy higher labor wages, which

raises the aggregate demand. When the standalone bank provides consumer credit, it does not

internalize the above social benefits. The E-commerce platform does not intend to internalize

these social benefits. The platform’s revenue comes from the volume of the (platform) market

transaction. When the platform tries to raise revenue, it increases the market transaction

and social benefits via the demand channel. In addition, the paper shows that the positive

externalities of E-commerce consumer credit are more significant in a less productive economy.

E-commerce consumer credit amplifies the effectiveness of the credit channel of monetary

policy transmission. Note that the E-commerce platform is more engaged in providing con-

sumer credit than banks, and consumer credit itself has important aggregate implications. The

monetary authority modifies the cost of credit creation via its impact on the risk-free bench-

mark rate. The presence of E-commerce consumer credit opens up a new channel that allows

the effect of monetary policy work through the E-commerce system and drives the aggregate

demand, firms’ entries and exits, total output, and aggregate productivity.

The purchase decision of present-biased consumers is particularly sensitive to the availability

of POS financing, which provides extra credit exactly when consumers can barely resist the

temptation. Given the synergy between E-commerce and consumer lending, the platform is

more inclined to extend credit to present-biased consumers than the standalone bank. Since

present-biased borrowers take on more debt, the demand for E-commerce products increases

in the first period. At the same time, labor wages and households’ incomes rise. The welfare

of households outside the E-commerce system improves because of the impulse purchase of

the present-biased borrowers. Nevertheless, when the demand from the behavior consumer 3

increases, the platform tends to lower the consumer rebates, which is not in favor of rational

consumers. Moreover, over-indebted consumers would have limited purchasing capacity in the

second period, which reduces the total output. Overall, E-commerce POS financing and the

present bias of behavior consumers together could cause the over-indebtedness of the economy.

Note that if only banks provide consumer credit in the model, present-biased consumers alone

do not lead to the excessive borrowing problem. In reality, when standalone banks extend

consumer credit, the time consumers obtain credit cards does not coincide with when they purchase products or services.

Literature. This paper is at the intersection of consumer credit literature (see a survey paper

Zinman (2014)) and recent studies on E-commerce, e.g., Fan, Tang, Zhu and Zou (2018), Luo,

Wang and Zhang (2019), Couture, Faber, Gu and Liu (2021). In particular, I emphasize

the complementarity between consumer credit provision and the E-commerce business. The

positive feedback within an E-commerce ecosystem could lead to over-borrowing issues on the household side.

In the consumer credit literature, there are theories of the undersupply of consumer credit

and also theories of oversupply. The undersupply of consumer credit is typically the conse-

quence of asymmetric information (e.g., Einav, Jenkins and Levin (2012) Dobbie and Skiba

(2013) and Karlan and Zinman (2009)). Households could take excessive leverage in the pres-

ence of negative externalities that are caused by asset fire-sales (Mian, Sufi and Trebbi, 2015;

Campbell, Giglio and Pathak, 2011), deleveraging in the liquidity trap (Eggertsson and Krug-

man, 2012; Guerrieri and Lorenzoni, 2017), or systemic risk (Khandani et al., 2013). In my

paper, regular banks undersupply consumer credit as they do not internalize the social benefit

that the aggregate productivity becomes higher when more firms operate on the E-commerce

platform. Excessive borrowing could also exist in my model because while the E-commerce

providers extend consumer credit to enhance the transaction, the platform and merchants

charge higher markup to consumers (i.e., lower consumer rebates in the model).

My paper also contributes to the platform economics literature that starts with Rochet and

Tirole (2003), Rochet and Tirole (2006), Caillaud and Jullien (2003), and Armstrong (2006).

The innovation of the paper is to incorporate the intertemporal dimension to the platform’s

decision (i.e., consumer lending) and highlight the general equilibrium effects of E-commerce

services on aggregate productivity, labor wage, and firm entries. It is vital to consider these

aspects given the accelerating development of E-commerce platforms like Alibaba and Amazon

in the past decade. For simplicity, the network externalities feature is absent in the model. In

addition, my paper also touches upon the scope of a platform.

My paper is related to the literature on present-biased behavior (Phelps and Pollak, 1968;

Laibson, 1997). To conduct welfare analysis, I employ the temptation preference with self-

control developed by Gul and Pesendorfer (2001). Similar to Barro (1999), ˙Imrohoro˘glu et al.

(2003), Luttmer and Mariotti (2003), and Krusell, Kuru¸s¸cu and Smith Jr (2010), this paper 4

also explores the general equilibrium implication of consumers’ present bias. In particular, I

highlight that the credit creation of E-commerce providers amplifies the over-indebtedness of

present-biased consumers, which could negatively impact the aggregate economy.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 1 discusses the complementarity and

the integration of E-commerce, E-payment, and consumer lending within a platform, which

sets the stage for my theoretical model. In Section 2, I present main results via a stylized

model. Section 3 focuses on the excessive lending with POS financing when consumers have present-biased preferences. 1

Digitalization of Business Environment

The completion of an ordinary transaction relies on the infrastructure of various types: physi-

cal, financial, legal, etc. A retailer wants to open a store in a popular mall that many customers

visit and also needs to accept various means of payment that customers frequently use. In ad-

dition, credit creation is also crucial for a vibrant business ecosystem as it increases consumers’

purchasing power. In a traditional offline business environment, different entities provide and

maintain the infrastructure of various sorts. For instance, property companies manage shop-

ping centers; payment companies, such as VISA and MasterCard, maintain payment networks;

and banks extend consumer credit.

With digitalization and internet proliferation, IT companies tend to integrate the provisions

of different infrastructures to pursue the return to scale and scope. This section will first review

cases in which Tech companies integrate the infrastructural services of E-commerce, payment,

and consumer lending. Second, I will discuss the complementarity between the three types of

services. Third, I will present the importance of E-commerce for the Chinese economy, which

is the backdrop of my model, in the following section. 1.1

Integration of E-Commerce, Payment, and Consumer Lending

Alibaba Group and its affiliate company Ant Group (hereafter, Ali) operate a giant online

ecosystem that fully integrates E-commerce, payment, and consumer lending. Ali owns the

largest E-commerce platform and the largest E-payment platform in China. It also plays a

critical role in the consumer lending market in China. While it cooperates with financial

institutions and facilitates their consumer lending on its platform, Ali also extends consumer

credit itself, largely financed via securitization. As of mid-2020, the balance of consumer credit

that involves Ant Group accounts for almost 20 percent of short-term consumer credit in China,

according to Ant Group’s IPO prospectus.

JD.com, which runs the second-largest E-commerce platform in China, is also active in

the consumer lending market. The main consumer credit that JD.com extends, Baitiao, is 5 Table 1: Consumer Credit

This table presents the balances of total consumer credit, short-term consumer credit, and consumer

credit arranged or assisted by Ant Group. Aggregate statistics are from Financial Stability reports

published by the People’s Bank of China. Ant Group’s data are from its IPO prospectus. Figures’ unit is trillion RMB.

consumer credit short-term Ant Finance (% as of short-term) 2017 9.62 6.80 0.52 (7.00%) 2018 12.0 8.80 0.84 (9.55%) 2019 14.0 9.92 1.62 (16.3%) 2020 15.1 8.77 1.73 (19.7%)

a Point-of-Sale installment loan for consumers. Merchants on its platform generally accept

Baitiao as a means of payment, although JD.com does not own a payment network beyond its E-commerce platform.

Amazon is an E-commerce platform provider with a global presence. Amazon issues its

credit card in the U.S., relying on the existing payment network Visa. In the rest of the

world, it cooperates with local financial firms and offers POS installment loans on its platform

to consumers. Merchants selling high-price items tend to accept POS credit as a means of payment.

Tencent and PayPal both run enormously large payment networks. Neither owns an E-

commerce platform, and their consumer lending businesses have minimal contribution to their

total revenues. For instance, although Tencent operates the second largest E-payment network

in China, the lending business only contributes 3 percent of Tencent’s FinTech income as of

2020, and the E-payment business generates 96 percent.1

“Buy Now, Pay Later” (BNPL) products, which have been growing rampantly world-

wide since 2019, are essentially POS installment loans.2 Unlike credit cards, BNPL typically

does not involve interest or require an in-depth credit check. Although they were primarily ac-

cepted as a means of payment for online shopping at the early stage, BNPL products have now

become increasingly available for in-store purchases. The primary source of revenues for BNPL

companies is the fees paid by merchants that are proportional to the BNPL-financed trans-

action values. 3 A BNPL FinTech company operates a standard two-sided platform between

merchants and customers that integrates the functions of payment and consumer lending. 1 The figures are reported by research articles of Huachuang Securities.

https://cj.hczq.com/paidArticles/45733?t=1629531347540.

2 According to a McKinsey report, banks lost $8 billion to $10 billion in revenue per year to BNPL companies

over the past couple of years. See the McKinsey & Company article “Buy now, pay later: Five business

models to compete” https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/financial-services/our-insights/buy-now-pay-later-

five-business-models-to-compete

3 According to Alcazar and Bradford (2021), the fees incurred by BNPL purchases are from 1.5 to 7 percent

of transaction values; and the fees of debit- or credit-card transactions are within 1 to 3 percent. 6 1.2

Complementarity and the Scope of a Platform

It appears natural that there exist complementarities between services of E-commerce, pay-

ment, and consumer lending for a platform, as I will illustrate in detail later. A challenging

question is why there is no such integration in the traditional offline business environment.4

It is beyond the scope of the paper to address the question. Readers may find answers in

the organizational economics literature (Brynjolfsson and Milgrom, 2013; Roberts and Saloner, 2013)

E-Commerce and Consumer Lending. Although no scientific research quantifies to what

extent consumer credit offered by E-commerce platforms could enhance their transaction vol-

umes, platforms themselves do report some statistics. According to Ant Group, online mer-

chants of electrical appliances could raise average transaction volume by 41 percent with the

help of Huabei credit; general merchants could increase transaction conversion rate by 40 per-

cent and sales by 23 percent once they allow for Huabei credit; customers’ purchasing capacity

is raised by 10 percent on average, and the rise becomes 50 percent conditional on customers’

monthly income below 1000 RMB. 5 In 2016, JD.com reported that Baitiao credit raises the

average transaction volume by 135 percent on Nov. 11 sales day.6 Similar results also found for

online merchants that accept BNPL, these POS financing products increase conversion rates

by 20 − 30% and raise average ticket sales by 30 − 50% according to an RBC Capital Markets article.7

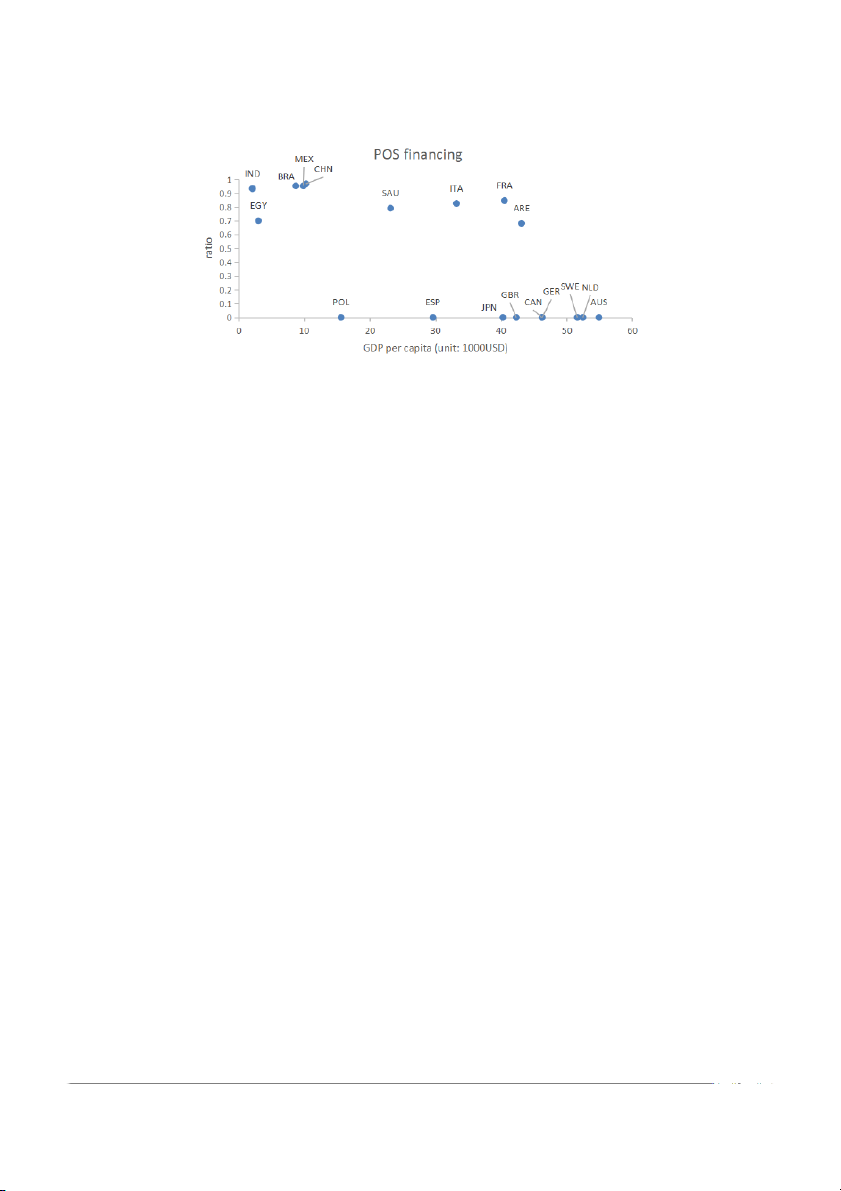

Amazon has a presence across multiple countries. The accessibility of POS financing differs

for similar products on Amazon’s platform in different countries. I collected 50 high-value

products sold on Amazon’s platforms in multiple countries and calculated the proportion of

products with POS financing options for each country. As Figure 1 shows, POS financing is

more accessible in countries with low GDP per capita. This fact is not surprising. Consumers

tend to have tight credit constraints in low-income countries. Merchants can significantly

increase their sales by accepting the payment method of POS financing.8 This suggestive

evidence is consistent with the finding of Guttman-Kenney, Firth and Gathergood (2022) that

BNPL is used more often in less developed regions in England.

Credit Card versus POS Financing. The issuance and the usage of a credit card are two

decisions made separately along the time dimension (by issuer and consumers, respectively).

4 One exception is probably American Express, which integrates the payment service with credit card is-

suance. However, since it primarily serves high-end customers, who should not have tight credit constraints by

the selection, clients treat Amex credit cards more as a means of payment rather than lines of credit.

5 Ant Group’s promoting page for Huabei https://open.alipay.com/static/activity/huabei.htm. and Ant

Group’s official social media account (Wechat) https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/AYIsmRzhiZUBWzRrAJG39A.

6 21jingji news article http://www.21jingji.com

7 https://www.rbccm.com/en/insights/tech-and-innovation/episode/2021-outlook-massive-shift-in-e-

commerce-spend “2021 Outlook: Payments, Processing ,and IT Services” by Dan Perlin.

8 There are multiple factors behind this phenomenon: financial development, regulatory environment, etc.

It appears promising to conduct a comprehensive and thorough empirical study along this line. 7

Figure 1: POS Financing on Amazon

The figure shows the relationship between the accessibility of POS financing in a country and

its GDP per capita. I hand-collected 50 almost identical products sold cross multiple countries

on Amazon’s platforms, and calculated the proportion of them with POS financing option. The U.S. is excluded.

When they check out products, consumers take their credit limits as given. Whether to use

cash or credit cards is only a matter of the means of payment. POS financing, like BNPL, is

the consumer credit extended on-site when customers pay for products or services. Checking

out with BNPL allows consumers to enjoy higher purchasing power than cash or credit cards.

Therefore, POS financiers have higher bargaining powers than card issuers when they negotiate

fees paid by merchants. And POS financing is often regarded as merchant-subsidized consumer credit.

E-Payment and Consumer Lending. The detailed transaction information that E-payment

companies can access exclusively (i.e., Big Data) could help them screen borrowers and assess

their default probabilities. Parlour, Rajan and Zhu (2020), Ghosh, Vallee and Zeng (2021), and

Ouyang (2021) consider the synergy between E-payment and consumer lending from theoretical

and empirical perspectives. It appears that major E-commerce platforms are more active than

major E-payment platforms in the consumer lending industry. It is again beyond the scope of

my paper to answer the question, and I suspect that one may find the driving forces behind

the scope of a platform from the organizational economics perspective. 1.3 China: a Digitalized Economy

The model I will present takes the Chinese economy, which is deeply digitalized, as its back-

ground. E-commerce, mobile payment, and various platforms have penetrated every facet of

life for anyone in China. Even offline businesses like restaurants and tourist sites still rely

on different platforms, e.g., social media, delivery, short video, etc., for publicity and cus-

tomer acquisition. In this subsection, I will present some simple statistics of aggregate and 8

internet-based consumption in China.

Table 2: Internet-Based Consumption

This table presents the total consumption, internet-based consumption (goods and services in the

third column and goods only in the fourth one), and retail transaction volume of leading E-commerce

platforms (Alibaba Group, JD.com, and Pingduoduo) in China. Aggregate level data are from the

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). Platforms’ data are from their annual reports. Platforms’

calculation of their transaction volume is not in line with NBS. Figures’ unit is trillion RMB.

total consumption internet-based internet-based goods Ali JD Pin∼ 2017 36.63 7.18 (19.6%) 5.48 (15.0%) 4.82 0.14 2018 38.10 9.01 (23.6%) 7.02 (18.4%) 5.73 1.68 0.47 2019 41.16 10.6 (25.8%) 8.52 (20.7%) 6.59 2.09 1.01 2020 39.20 11.8 (30.0%) 9.76 (24.9%) 7.49 2.61 1.67

According to its National Bureau of Statistics, the internet-based consumption of goods and

services has accounted for more than 20 percent of total consumption since 2017 (see Columns 2

to 4 in Table 2). The figure jumped to 30 percent in 2020, partly due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Concerning the consumption of goods, its size increases from 15 percent to 25 percent of total

consumption from 2017 to 2020. A key feature of the E-commerce market in China is the tense

concentration by a few conglomerates, i.e., Ali, JD.com, and the newcomer Pinduoduo. Table

2 compares the volume of their self-reported retail transactions and the total internet-based

consumption each year.9 Among the three platforms, the entire transaction volume of JD.com

and Pinduoduo is only half of the giant Ali. 2

An E-Commerce Platform with Rational Customers

Given the significance of E-commerce for the aggregate economy in China, I build a general

equilibrium model that captures the key features of E-commerce platforms and the consumer

credit they extend. The framework is used to analyze the effects of E-commerce credit creation

on the aggregate economy and social welfare and also sheds light on the potential policy

intervention regarding the consumer credit supply of E-commerce platforms. 2.1 Model

The economy lasts for three periods, with a single E-Commerce platform that exists only in

the first two periods. A homogeneous perishable consumption good serves as num´eraire. A

unit measure of heterogeneous firms exists in all three periods. Each firm employs Lt efficiency

9 Platforms’ calculation of their transaction volume is not the same as that by NBS. For instance, platforms

include orders that have been canceled into the total trading volumes. 9

units of labor to produce consumption goods according to the technology ALα − ξ, where t

ξ denotes the overhead/operating cost, which is uniformly distributed over [ξl, ξh] across all

firms, and A and α are positive constants. Firms choose to operate in either the traditional

physical market or an E-commerce market serviced by the platform. Operating in the platform

market allows a firm to cut its overhead expense in half, for which the platform charges a fee

φ. Given the wage wt, a firm’s profit is either ALα − ξ − w t tLt

if it operates in the physical market; or ALα − 0.5ξ − φ t t − wtLt

if it operates in the platform market.

The utility function of an economic agent is ln (c1 + ce > 0} η + β (ln (c

) − 1 {ce > 0} η) + β2 ln (c 1) − 1 {ce1 2 + ce 2 2 3) , where

ct, t = 1, 2, 3, denotes the consumption of goods purchased from the physical market, ce, t = 1, 2, t

the consumption of goods purchased from the platform, η > 0 is the preference disutility

parameter from the platform transaction. The disutility could reflect the habits of purchasing

products in the physical market or the lack of trust in the new business mode of E-commerce.

η is assumed to be distributed uniformly over η, ¯

η across all agents (η ≥ 0). Due to the

disutility of platform consumption, the platform provides discounts at rate τt, t = 1, 2 to its customers.

There are two types of consumers with different labor income streams: savers and borrowers.

The measure of each type is 0.5. Although all agents supply labor inelastically in each period,

savers provide 3, 3 , 0 efficiency units of labor in periods 1, 2, and 3, respectively, and borrowers 2 2

provide 1, 1 , 2 efficiency units of labor in periods 1, 2, and 3. Hence, the aggregate labor 2 2

supply is constant over time. And, savers’ labor income stream is 3w w 2 1, 3 2 2, 0, and borrowers’ labor income stream is 1w w

. The total profits of all firms and the platform in each 2 1, 1 2 2, 2w3

period denoted by Tt, t = 1, 2, 3 are paid back to all agents evenly as dividend payouts.

Liquidity provision is necessary for both savers and borrowers to smooth their consump-

tion. The financial service includes two components: 1) the storage technology that transfers

consumption goods one-to-one from one period to the next; 2) the technology of verifying

borrowers’ pledgeable income in period 3 and determining the credit limit ¯bt, t = 1, 2. As-

sume that the technological cost associated with the credit limits are given by χ ¯ 1 b1 and 10 χ ¯ 2 b2

in periods 1 and 2, respectively. Both χ1 (·) and χ2 (·) are increasing and convex with

χ1 (0) = χ2 (0) = 0. Both standalone banks and the E-commerce platform can access the same

financial technology. Since the platform operates only in the first two periods, it provides finan-

cial service from period 1 to period 2. ¯be denotes the credit limit offered by the platform, which

is POS financing given its link to the sales of merchants on the platform. The net interest

spread for the financial intermediation is assumed to be a positive constant ν. To simplify the

following analysis, I make two assumptions regarding financial technology and the net interest spread.

Assumption 1 χ1(·) and χ2(·) are such that 1) borrowers’ credit constraints are binding in

the first two periods, and 2) the constraint is tighter period 1.

Assumption 2 The net interest margin ν is sufficiently small.

Remark 1: Consumer Discount and Disutility. For simplicity, I assume that the product

market is fully competitive. Hence, firms obtain no mark-up. The consumer discount can be

interpreted as the reduction in mark-up in reality that merchants and platforms jointly offer.

The disutility parameter refers to the match value between a consumer and the platform. This

parameter could be negative, capturing the fact that consumers enjoy the convenience or other

benefits of online shopping. In this case, merchants or the platform could charge a higher

mark-up in a more general model.

Remark 2: Relation to Two-Sided Platform Models. In this model, firms are subject to

the pure-membership fee, and consumers obtain pure-usage subsidies (i.e., negative usage fees).

The match value for a firm of ξ-type is 1ξ and that for a consumer with disutility parameter 2

η is −η. The platform only incurs a sunk cost to establish the exchange market infrastructure

without any per-usage or per-agent costs involved. More importantly, I assume that there is a

perfect matching technology accessible to both the platform market and the physical market.

That is, firms’ likelihood of selling all their products is independent of the number of consumers

joining the platform and vice versa. Relaxing the perfect matching assumption would allow for

the cross-side externalities, which is at the core of the multi-sided platform literature.

Remark 3: Financial Technology. In the real world, platforms use Big Data and Machine

Learning to minimize the expenses of screening and monitoring procedures. Hence, the plat-

forms’ financial service efficiency could be close to regular banks. I assume that the platform

exists in the first two periods so that the labor wage in period 3 is easily fixed. To some

extent, the platform internalizes the negative consequence of consumer lending in period 1.

Assumption 1 ensures that the platform’s credit extension in Period 1 has intertemporal effects

on borrowers’ consumption in Period 2. Assumption 2 is to ensure that the revenue from the

financial service is not large enough to distort the platform’s optimal choice in the E-commerce business. 11 2.2 Characterization

I will first consider firms’ production decisions and relate the fee φt that the firm charges

to the demand for seller’s permits. Switching to the consumers’ optimal choices, I find the

connection between the demand for platform products, consumer rebates, and consumer credit.

Lastly, I analyze the platform’s profit maximization problem regarding the choice of seller’s

fees, consumer rebates, and credit. 2.2.1

Production Optimization and Supply Side

A firm’s labor employment decision is independent of its type ξ. Given the labor market

clearing wage wt in period t, a firm’s labor demand is 1 Aα 1 α − Lt = l(wt) ≡ , (1) wt

if it operates. It is straightforward to observe that a firm would not operate in the physical market if its profit ALα − ξ − w t tLt < 0.

Plugging the optimal labor employment Lt, the above condition becomes 1 1 α − 1 (Aα) 1 α 1 α − (wt)− − − ξ < 0. α Hereafter, I let ˜ ξt denote ˜ 1 1 α ξ(w 1 α 1 α t) ≡ − 1 (Aα) − (w − , α t)−

which is the before-operating-cost profit that all active firms have. It is easy to see that in

period 3 when the E-commerce market does not exist, the labor market clearing condition implies w3 or ˜ ξ3 must be such that ˜ Z ξ(w3) l(w3)dF (ξ) = 1 ξ

In periods 1 and 2, firms consider the option of paying the platform fee φt to operate in the

platform market. Since the platform could help firms to cut their operating expenses in half,

firms with 0.5ξ ≥ φt would prefer the platform market to the physical market if they choose

to operate. It is easy to see that firms with ξ > 2 ˜ ξt − 2φt (i.e., ˜

ξt − 0.5ξ − φt > 0) would suffer

negative profits if they operate in the platform market.

To sum up, firms with ξ < 2φt choose to stay in the physical market; firms with ξ between 2φt and 2˜

ξt − 2φ switch to the E-commerce market. Hence, if φt < 0.5 ˜ ξ (i.e., 2 ˜ ξt − 2φ > ˜ ξt), 12

there are firms, which are unable to survive in the physical market, starting to undertake their

businesses thanks to E-commerce. In addition, firms with ξ between 2φt and ˜ ξt could enjoy

higher profits given the lower operating expenses.

In periods 1 and 2, the labor market clearing condition is Z 2 ˜ ξ(wt)−2φt l(wt)dF (ξ) = 1. ξ

Hence, given the platform fee φt, the labor market clearing condition uniquely determines the

labor wage wt and the supply of consumption goods in the platform market, which is − φt 1 Z 2˜ξ(wt) 2 S (φt; wt) = F 2 ˜

ξ(wt) − 2φt − F (2φt) Al(wt)α − ξdF (ξ) . 2 2φt Note that ˜ ξ(w Al(w t) t)α = . 1 − α Then, 1 + α 2 + 2α S (φ ˜ ˜ t; wt) = ξ(w ξ(wt)φ (1 − t. (2) α) ¯ t)2 − ξ − ξ (1 − α) ¯ ξ − ξ

Although the labor market clearing condition determines the labor wage wt given the plat-

form fee φt, I assume that the platform does not manipulate the labor market clearing wage wt via choosing φt.

Lastly, firms’ total profits in periods 1 and 2 are Z 2φt Z 2 ˜ ξ(wt)−2φt T f = ˜

˜ξ(wt) − 0.5ξ − φtdF (ξ) ; t ξ(wt) − ξdF (ξ) + ξ 2φt in period 3, ˜ Z ξ(w3) T f ˜ 3 = ξ(w3) − ξdF (ξ) . ξ 2.2.2

Consumption Optimization and Demand Side

Physical market goods and platform market goods are perfect substitutes. As long as the

platform discount rate τt is positive, agents would strictly prefer either physical or platform

market consumption depending on the disutility parameters η. I will first consider savers’

consumption optimization problem and then discuss borrowers’ choices. 13

Given the (risk-free) saving rate R, a saver’s problem is max

: ln (c1 + ce) − 1 {ce > 0} η + β ln (c

) − 1 {ce > 0} η + β2 ln (c 1 1 2 + ce 2 2 3) c1,ce ,c 1,c2,ce 2 3 c c 3 3 1 3 T3 c e 2 + (1 − τ2) ce2 1 + (1 − τ1) c + + ≤ I ≡ w w + 1 1 + T1 + R R2 2 R 2 2 + T2 R2 The consumption rule is I c1 = 1 {η > − ln (1 − τ 1 + β + β2 1)} , I ce1 = 1 {η ≤ − ln (1 − τ (1 − τ 1)} 1) (1 + β + β2) βRI c2 = 1 {η > − ln (1 − τ 1 + β + β2 2)} βRI ce2 = 1 {η ≤ − ln (1 − τ (1 − τ 2)} 2) (1 + β + β2) β2R2I c3 = 1 + β + β2

In period t, savers with η > − ln (1 − τt) prefer the physical market goods to the platform

market goods. The term − ln (1 − τt) captures the utility benefit of consumer discounts offered by the platform.

The consumption decision is more delicate for a borrower due to the platform’s consumer

credit. Hereafter, I conjecture that ¯

be ≥ ¯b1, i.e., the platform is willing to provide more credit

than the bank. Given the borrowing rate Rb = R + ν, a borrower’s problem is max

: ln (c1 + ce) − 1 {ce > 0} η + β ln (c > 0} η + β2 ln (c 1 1 2 + ce2) − 1 {ce2 3) c e 1,c ,b 1,b1,c2,ce 2 2,c3 1 c e 1 + (1 − τ1) c > 0} ¯ be + (1 − 1 {ce > 0}) ¯ 1 ≤ w T b b 2 1 + 1 + 1, b1 ≤ 1 {ce1 1 1 1 c e 2 + (1 − τ2) c2 ≤ w

2 2 + T2 − Rbb1 + b2, b2 ≤ ¯ b2 c3 ≤ 2w3 + T3. 14

The consumption rule in this case is 1 c1 = w 1 {η > − ln (1 − τ 2 1 + T1 + ¯b1 1) + ∆} 1 w1 + T1 + ¯be ce = 2 1 1 {η ≤ − ln (1 − τ 1 − τ 1) + ∆} 1 1 c2 = w 1 {η > − ln (1 − τ 2 2 + T2 − Rbb1 + ¯b2 2)} 1 w2 + T2 − Rbb1 + ¯b ce = 2 2 2 1 {η ≤ − ln (1 − τ2)} 1 − τ2 c3 = 2w3 + T3 − Rb¯ b2 ,where ! ¯be − ¯b Rb ¯be − ¯b 1 ∆ ≡ ln 1 + 1 + β ln 1 − (3) 1 w 1 w 2 1 + T1 + ¯ b1 2 2 + T2 − Rb¯ b1 + ¯b2

For a borrower, the benefit of the platform consumption consists of two components: 1) the

purchasing discount captured by − ln (1 − τ1); 2) the utility benefit of the extra platform

consumer credit captured by ∆. When a borrower chooses the platform over the physical

market, her funds at disposal increase by ¯be − ¯b1 in Period 1, which translates to the utility benefit ¯be − ¯b ln 1 + 1 . 1 w 2 1 + T1 + ¯ b1

At the same time, the borrower’s disposable income declines by Rb ¯be − ¯b 1 in period 2, whose

utility cost is captured by the second logarithm term of equation 3.

Given the consumption decisions of both savers and borrowers, the demand function for the platform market goods is − ln (1 − τ 1) − η I ∆0.5w1 + T1 + ¯be g 2 τ1, ¯ be = + 0.5w1 + T1 + ¯be + (4) 2(1 − τ 1) ¯ η − η 1 + β + β2 2(1 − τ1) ¯ η − η

in Period 1, of which the measure of savers is − ln(1−τ1)−η and the measure of borrowers is ¯ η−η

− ln(1−τ1)+∆−η. Note that endogenous variables w1, T1, w2, T2, w3, and T3 also affect the demand. ¯ η−η

For brevity, I highlight τ1 and ¯be chosen by the platform on the left-hand side of equation 4.

In period 2, the measure of both savers and borrowers that prefer platform products is

− ln(1−τ2)−η . Note that if − ln(1 − τ ¯ η−η

2) > − ln(1 − τ1) + ∆, borrowers of type η ∈ − ln(1 −

τ1) + ∆, − ln(1 − τ2) stay in the physical market in Period 1 and then switch to the platform

market in Period 2. Nevertheless, it does not yield any novel insight to consider this case. I

only consider the scenario where − ln(1 − τ2) ≤ − ln(1 − τ1) + ∆. Hence, the demand function 15

for platform products in period 2 is − ln (1 − τ 2) − η βRI 1 g 2 τ2, ¯ be = + w2 + T2 − Rb¯be + ¯b2 (5) 2(1 − τ 2 2) ¯ η − η 1 + β + β2 2.2.3 Financial Service

Both the standalone bank and the platform provide financial services. I first consider the

standalone bank’s profit maximization problem. The bank absorbs total deposit savings dt and extend credit ¯

bt to each borrower. Let F b denote the measure of borrowers who stay t

with the physical market, which equals F (¯

η) − F (− ln (1 − τ1) + ∆) in Period 1 and F (¯ η) −

F (− ln (1 − τ2)) in period 2. Taking F b as given, the bank’s optimization problem in period t t is max : RbF b¯b ¯b χ ¯ t t + dt − F b t t − F b t bt − Rdt d ¯ t ,bt s.t. d ¯ t ≥ F b b χ ¯ t t + F b t bt

The constraint of the bank optimization problem reflects that the verification cost of a bor-

rower’s pledgeable income is paid out of the bank’s deposit savings. For simplicity, I consider

an economy with excess savings, which implies that the saving rate R offered by liquidity

providers equals its opportunity cost 1. Given Rt = 1 and Rb = R t t + ν , the bank’s problem reduces to max : ν¯ b ¯ t − χt bt ¯ bt

The credit limit ¯bt offered by the bank in period t is determined by the first order condition ν = χ0 ¯b . (6) t t

The bank profit generated in period t is denoted by T b. t 2.2.4 Platform’s Optimization

The platform’s primary revenue is the fee of a seller’s permit. The output of the E-commerce

service is then the measure of seller’s permits denoted as Yt, whose price is fee φt. Firms’ choice

of where to operate discussed in Section 2.2.1 yields Y t = F 2 ˜ ξ(wt) − 2φt − F (2φt) ,

which defines an inverse demand function given the distribution of firm type ˜ ξ ¯ ξ − ξ φ(Y t t) = − Y 2 4 t. (7) 16

The platform needs to make sure that all firms can sell their products in the platform

market, i.e., the platform market clearing condition must hold 1 + α 2 + 2α D ˜ ˜ t = S (φt) = ξ(w ξ(w (1 − t)φt(Yt). (8) α) ¯ t)2 − ξ − ξ (1 − α) ¯ ξ − ξ 1 + α = ˜ ξ(w 2(1 − t)Yt α)

I now consider the platform product demand Dt as the input, and the linear production function

above transforms inputs into outputs, i.e., the measure of firms paying the platform fees. The

input’s unit cost is τt, which is determined by the demand functions of the platform products D1 = g1(τ1, ¯be) (9) D2 = g2(τ2, ¯be) (10)

Let τ1(D1, ¯be) and τ2(D2, ¯be) denote the implicit functions defined by equations (9) and (10),

respectively. To sum up, the platform’s E-commerce profit is φtYt − τtDt

in period t, where Yt is the output and Dt the input. Since the platform is the monopoly

providing the E-commerce service, it has market power over the output price φt and the input cost τt.

The profit of the platform’s financial services is

− ln (1 − τ1) + ∆ − η ν¯be − χ¯be, 2 ¯ η − η

where − ln(1−τ1)+∆−η is the measure of borrowers that buy products on the platform. Then, the 2(¯η−η)

platform’s profit maximization problem is

− ln (1 − τ1) + ∆ − η max : φ ¯

1(Yt)Yt − τ1D1(Y1) + φ2(Y2)Y2 − τ2D2(Y2) + ν¯be − χ1 be Y ¯ 1,Y2,be 2 ¯ η − η

Note that variables τ1, τ2, and ∆ depend on the choice variables of the optimization problem.

First-order conditions w.r.t. Y1 and Y2 are dφ dD ∂τ ¯ 1 dD ν¯be − χ1 be φ 1 1 1 1 + Y1 − τ − (1 − δ) D ; dY 1 1 = 0, where δ ≡ 1 dY1 ∂D1 dY1 2D1(1 − τ1) ¯ η − η dφ dD ∂τ dD φ 2 2 2 2 2 + Y − D dY 2 − τ2 2 = 0 2 dY2 ∂D2 dY2

The marginal benefit of issuing more seller’s permits Yt is the permit fee φt deducting the price 17

effect dφtY < 0. The marginal cost is that the platform needs to retain more costumers dY t t τ dDt dDt t

and also offer more rebates ∂τt D dY

t to individual customers. In period 1, the rise in t ∂Dt dYt

the consumer discount τ1 increases the financial service revenue because more borrowers choose

the platform products. However, Assumption 2 guarantees that the increase in consumer rebate

expenses dominates the marginal increase in the financial service revenue, i.e., δ < 1.

First-order condition w.r.t. ¯ be is ∂τ ∂τ

− ln (1 − τ1) + ∆ − η 0 = − 1 2 D ¯ 1 − D2 +

ν − (1 − δ) χ0 be (11) ∂¯be ∂¯be 2 ¯ η − η t 1 1 βRb + − ν¯be − (1 − δ)χ1(¯ be) 2 0.5w1 + T1 + ¯be 0.5w2 + T2 − Rb¯be + ¯b2

Compared with the bank’s first-order condition (6), the additional benefit of offering higher

consumer credit is to lower the expense of consumer rebates in period 1 and increase the

proportion of consumers choosing the platform by raising ∆. Note that since ∂g1 > 0 and ∂τ1

∂g1 > 0, equation 9 yields ∂¯ be ∂τ ∂g1 1 = − ∂¯be < 0 ∂¯ be ∂g1 ∂τ1

fixing Dt, which indicates the supplementarity between consumer discount offering and credit

provision. Nevertheless, more debt inherited from period 1 dampens the demand in period 2,

leading to more consumer discounts. 2.2.5 Equilibrium

Equilibrium Definition. I define an equilibrium where the E-commerce platform has monopoly

power over both its seller permit fees and consumer discount rates:

1. On the production side, taking labor wages (wt, t = 1, 2, 3) and platform fees (φt, t = 1, 2)

as given, firms solve their profit maximization problems, which yield their demands for

labor (1), the supply for the platform products (2), and the inverse demand function for the platform permits (7).

2. On the demand side, taking labor the platform consumer discounts (τt, t = 1, 2), wages

(wt, t = 1, 2, 3), and income transfers (Tt, t = 1, 2, 3) as given, households solve their util-

ity maximization problems, which give rise to the inverse demand functions for platform

products (9) and (10) combining with the platform market clearing condition (8).

3. Taking the gross risk-free rate R and net interest margin ν as given, the standalone bank

solves its profit optimization problem, which determines the credit limits ¯b1 and ¯b2 for

consumers in the physical market in Periods 1 and 2.

4. Taking the demand functions, R, and ν as given, the platform solves its optimization

problem, which determines the platform fees (φt, t = 1, 2), consumer discount rates 18

(τt, t = 1, 2), and also the credit limit ¯be for its customers in Period 1.

5. The labor market clears in each period.

The market clearing conditions of the platform seller permits and the platform products have

been embedded in the inverse demand function of platform permits and platform products,

respectively. The physical markets are clear by Walras’s Law. 2.3 Platform’s Credit Creation

In this subsection, I will show that the platform would fulfill the credit creation role left by the

banking system if there is a shortage of consumer credit in period 1. Suppose that the platform sets the credit limit at ¯

be = ¯b1 and I will focus on the platform profit’s first-order derivative

w.r.t. ¯be. Later, I will show that the marginal benefit of raising ¯ be from ¯ b1 is strictly positive if

¯b1 is sufficiently small compared to the second-period credit limit ¯b2. Credit limits offered by

the standalone bank will be treated as if they were parameters since the optimality conditions that determine ¯

b1 and ¯b2 are independent of other equilibrium conditions (see equation 6).

Suppose the credit limit offered by the standalone bank decreases, borrowers’ funds at

disposal decline in period 1 and increase in period 2. To prevent the sharp decline in the

demand for platform products, the platform has to raise the consumer discount rate in period

1. For the similar reason, the platform finds it optimal to lower the discount rate in period 2. Lemma 1 If ¯be = ¯

b1, τ1 − τ2 is decreasing in ¯b1. Proof. See Appendix A.

Suppose it is too expensive to obtain customers via the price instrument. In that case, the

platform finds it cost-saving to resort to the quantity instrument, i.e., offering borrowers more

credit to boost their demands for platform products. I formalize this idea in the following theorem. Theorem 1 If ¯

b1 is sufficiently lower than ¯b2, the platform finds it optimal to offer a credit limit ¯ be that is higher than ¯b1

Proof. I will show that the right-hand side of the platform’s first-order condition w.r.t. ¯ be

(equation 11) is strictly positive if ¯

be = ¯b1 and ¯b1 is sufficiently lower than ¯b2. Given that ¯be = ¯b ¯

1, since ν = χ01 b1 , the right-hand side of equation (11) reduces to a

positive term (the second line of equation 11) plus ∂τ ∂τ − 1 2 D1 − D2 (12) ∂¯be ∂¯be (− ln(1 − τ1) − η)2 (− ln(1 − τ2) − η)2 = − Rd 1 − ln(1 − τ1) − η 1 − ln(1 − τ2) − η

The above equation is given by the substitution rates between the discount rate τ1 and ¯ be and 19