Preview text:

lOMoARcPSD|36041561

PowerPoint Lecture Notes for Chapter 1:

Ten Principles of Economics

Principles of Economics 5th edition, by N. Gregory Mankiw

Premium PowerPoint Slides by Ron Cronovich Dear Colleague, C H A P T E R 1

Ten Prin cip les of Econ om ics

Thank you for using the Premium PowerPoints for Mankiw’s

Principles of Economics. I update these approximately once EcP Po R R I n N N C C I o P P L L Em E S S O O Fi F cs

per year, to update the data, fix any typos, and incorporate the N. N Gr G egory Ma M nkiw

best suggestions from users like yourself. If you have any Premium PowerPoint Slides

suggestions, corrections, or feedback, please email me at by Ron Cronovich

rcronovich@carthage.edu. Check the textbook’s website to

© 2009 South-Western, a part of Cengage Learning, all rights reserved

make sure you’re always using the most recent version.

In this area (the “notes” section), I occasionally include notes

that are visible only to you and will not display during your

presentation in class. In slides with data tables or charts, the

notes area provides the source information (often a URL or

web address to the original data). In other slides, the notes

area provides information that might be helpful when teaching

this material, particularly for new instructors and grad assistant teachers.

For chapter 1, most instructors try to cover this chapter in a

single class session (especially those that are teaching the

second of a two-semester sequence). If you are teaching a

“principles of microeconomics” course, you might consider

skipping Principles 8-10, which deal with macroeconomics.

Near the end of the chapter are four slides titled “FYI: How to

Read Your Textbook.” In the notes section of these slides, I

describe an in-class activity that teaches effective reading skills to students. In th is ch ap ter,

look for th e an sw ers to th ese q u estion s:

§ What kinds of questions does economics address?

§ What are the principles of how people make decisions?

§ What are the principles of how people interact?

§ What are the principles of how the economy as a whole works? 5

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

You might want to elaborate a bit on some of the points made

Wh at Econ om ics Is All Ab ou t

§ Scarcity: the limited nature of society’s here. Some examples: resources

§ Economics: the study of how society manages

its scarce resources, e.g. §

“How do people decide how much to work?” Time is scarce

how people decide what to buy,

how much to work, save, and spend

resource – there’s just not enough time to do everything we’d

§ how firms decide how much to produce, how many workers to hire

like to do. How do we decide how much of our time to spend

§ how society decides how to divide its resources

between national defense, consumer goods,

working? There’s a tradeoff: the more time we spend

protecting the environment, and other needs

working, the higher our income, and therefore the more stuff

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 6

we can buy. But, the more time we spend working, the less

time we have for leisure – hanging out with friends, going

hiking, watching movies, etc. (You might want to ask your

students how THEY decide how much time to spend working.

Some will say it depends on how many classes they are taking,

or the time requirements of the available jobs. But probably at

least a few will say the wage – the higher the wage, the more worthwhile to work.)

“How do firms decide what kind of labor to hire?” Firms can

hire unskilled or skilled workers. The skilled workers are

more productive, but cost more than the unskilled workers.

“How do firms decide how much to produce?” Ask your

students, and see if any of them say “it depends on the price of

the product they sell.” (Probably some will say “it depends on

whether there’s a lot of demand for the product”. To which

you might respond “and if there’s a lot of demand for the

product, what does that mean for the price that firms can get for the product?”)

Decision-making is at the heart of economics. The individual

The principles of H O W P EO PLE

must decide how much to save for retirement, how much to M AKE D D ECIS IO N S

spend on different goods and services, how many hours a week

to work. The firm must decide how much to produce, what

kind of labor to hire. Society as a whole must decide how

much to spend on national defense (“guns”) versus how much

to spend on consumer goods (“butter”).

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

H O W PEO PLE M AKE D ECISIO N S

Principle #1: People Face Tradeoffs

Al decisions involve tradeoffs. Examples:

§ Going to a party the night before your midterm leaves less time for studying.

§ Having more money to buy stuff requires working

longer hours, which leaves less time for leisure.

§ Protecting the environment requires resources

that could otherwise be used to produce consumer goods.

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 8

H O W PEO PLE M AKE D ECISIO N S

HEADS UP. The 5th edition uses “equality.” The fourth and

Principle #1: People Face Tradeoffs

earlier editions used “equity” here.

§ Society faces an important tradeoff:

efficiency vs. equality

§ Efficiency: when society gets the most from its

You may want to elaborate verbally on the last bullet to insure scarce resources

§ Equality: when prosperity is distributed uniformly that the point is clear. among society’s members

§ Tradeoff: To achieve greater equality,

could redistribute income from wealthy to poor.

But this reduces incentive to work and produce,

“Redistribute income from wealthy to poor” is accomplished

shrinks the size of the economic “pie.”

through the progressive tax system, as well as social programs

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 9

like food stamps and unemployment insurance that try to

provide a safety net for people at the low end of the income distribution.

“But this reduces the incentive to work” – the reward for

working hard is a high income. Taxes reduce this reward, and

therefore reduce the incentive to work hard.

H O W PEO PLE M AKE D ECISIO N S

Principle #2: The Cost of f Someth thing Is

What You Give Up to Get It

§ Making decisions requires comparing the costs

and benefits of alternative choices.

§ The opportunity cost of any item is

whatever must be given up to obtain it.

§ It is the relevant cost for decision making.

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 10

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

H O W PEO PLE M AKE D ECISIO N S

Here’s a fun tangent if you have the class time and are so

Principle #2: The Cost of f Someth thing Is inclined:

What You Give Up to Get It Examples: The opportunity cost of…

Ask your students about the saying “The best things in life are

…going to college for a year is not just the tuition,

books, and fees, but also the foregone wages.

free.” Ask them to name some of these things that supposedly

…seeing a movie is not just the price of the ticket,

are free. Ask them what “free” means in this context. The

but the value of the time you spend in the theater.

idea here is to get them to see that even things without an

explicit monetary cost are not truly “free” because they have

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 11 an opportunity cost.

For example, when you ask them to name the “best things”

that are “free,” they will respond with answers like love, sitting

at the top of a mountain you just climbed and enjoying an

awesome view, or maybe witnessing the joy of a child who has

just been given a new toy. In each case, there is no explicit

monetary cost, but there’s an opportunity cost.

For example, a day spent climbing a mountain represents a day

of foregone wages. And the fact that the mountain offers the

incredible view probably means that land has been set aside for

a national park that might otherwise have been used to produce

industrial chemicals, or for a subdivision of million-dollar homes.

With love, it’s less obvious, but if prodded enough, your

students will be able to think of non-monetary costs associated

with love. For example, you might not want to see the latest

Ashton Kutcher film, you might think he’s the world’s worst

actor. But your boyfriend/girlfriend/teenage daughter or other

loved one is DYING to see it, they are BEGGING you to take

them. So you take them. That’s true love, don’t you think?

And it’s certainly not free.

H O W PEO PLE M AKE D ECISIO N S

Principle #3: Rational People Think at th the Margin Rational people

§ systematically and purposefully do the best they

can to achieve their objectives.

§ make decisions by evaluating costs and benefits

of marginal changes – incremental adjustments to an existing plan.

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 12

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

H O W PEO PLE M AKE D ECISIO N S

See the textbook for two classic examples:

Principle #3: Rational People Think at th the Margin

1. The diamond-water paradox: water is essential for life but Examples:

§ When a student considers whether to go to

virtually free; diamonds are inessential but expensive.

college for an additional year, he compares the

fees & foregone wages to the extra income

2. The near-zero marginal cost of an airline taking an extra

he could earn with the extra year of education.

passenger when the flight isn’t full.

§ When a manager considers whether to increase

output, she compares the cost of the needed

labor and materials to the extra revenue.

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 13

H O W PEO PLE M AKE D ECISIO N S

Principle #4: People Respond to to Incenti ti ves

§ Incentive: something that induces a person to

act, i.e. the prospect of a reward or punishment.

§ Rational people respond to incentives. Examples:

§ When gas prices rise, consumers buy more

hybrid cars and fewer gas guzzling SUVs.

§ When cigarette taxes increase, teen smoking falls.

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 14

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

Most of these PowerPoint chapters have two or three Active A A C C T I V V E E L L E E A A R R N I N G G 1 Ap p lyin g t t h e p p rin cip les

Learning activities. They break up the lecture with a short in-

You are sel ing your 1996 Mustang. You have

already spent $1000 on repairs.

class activity for immediate reinforcement, application, or

At the last minute, the transmission dies. You can

assessment of the material in the preceding slides.

pay $600 to have it repaired, or sell the car “as is.”

In each of the following scenarios, should you

A good idea is to give students time to formulate their answers

have the transmission repaired? Explain.

before asking for volunteers to share their answers with the

A. Blue book value is $6500 if transmission works, $5700 if it doesn’t

class. When the questions or exercises are more complex,

B. Blue book value is $6000 if transmission works, $5500 if it doesn’t

consider having them work in pairs. 15

Digression on class participation:

In general, it’s not a good idea to try to solicit participation by

saying “Now who can tell me the answer to….”. The

invariable result is regular participation by very few students –

the quick thinkers who have the confidence to answer

spontaneously in front of the class – while most students remain silent.

When students have a bit of time to think through their

answers, they are more likely to be comfortable sharing their

answers with you and the class.

Even better: try a simple, time-tested activity called “THINK-

PAIR-SHARE.” Pair students up. Pose a question or

problem. Have students work on the problem individually for

a couple minutes. Then, allow a couple minutes to work in

pairs: each student tries to explain to the other why his or her

answer is correct, and the other offers feedback. In many

cases, they come up with better answers by working together.

Finally, ask for volunteers. Students are much more likely to

participate since they have had the opportunity to “test” their

answers on a classmate. And those who do not participate will

at least have had the chance to share their answer with, and get

feedback from, one other student.

Activities like these are useful to break up a lecture every 20

minutes or so. They help maintain students’ attention spans,

and increase their comprehension of the material you cover.

These activities are also useful for quick, informal assessment

– often, they will alert you to problems (such as students not

getting what you think they’re getting) which you can then

correct before moving on to cover additional material. End of digression.

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561 A A C C T I V V E E L L E E A A R R N I N G G 1 An sw ers

Cost of fixing transmission = $600

A. Blue book value is $6500 if transmission works, $5700 if it doesn’t

Benefit of fixing the transmission = $800 ($6500 – 5700).

It’s worthwhile to have the transmission fixed.

B. Blue book value is $6000 if transmission works, $5500 if it doesn’t

Benefit of fixing the transmission is only $500.

Paying $600 to fix transmission is not worthwhile. 16

If you wish, you can omit this slide and just give this A A C C T I V V E E L L E E A A R R N I N G G 1 An sw ers

information to the class verbally. Observations:

§ The $1000 you previously spent on repairs is

irrelevant. What matters is the cost and benefit

of the marginal repair (the transmission).

§ The change in incentives from scenario A

to scenario B caused your decision to change. 17

Whether we’re talking about the U.S. economy, or the local

The principles of

economy, the term “economy” simply means a group of people H O W PEO PLE IN TERACT interacting with each other.

These interactions play a critical role in the allocation of

society’s scarce resources. For example, the interaction of

buyers and sellers determines the prices of goods and the

amounts produced and sold. These interactions are an

important part of what economists study.

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561 H O W PEO PLE IN TERACT

If each person had to grow his own food, make his own

Principle #5: Trade Can Make Everyone

clothes, cut his own hair, we would have a world full of Bett tter Off ff

skinny, unfashionable poor people having bad hair days every

§ Rather than being self-sufficient,

people can specialize in producing one good or day of the week.

service and exchange it for other goods.

§ Countries also benefit from trade & specialization:

§ Get a better price abroad for goods they produce

It’s far more efficient for each person to specialize in

§ Buy other goods more cheaply from abroad than could be produced at home

producing a good or service, and then exchanging it with other

people for the things they produce.

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 19

The statement “trade can make everyone better off” should not

be hard to understand, if you think about it for a moment:

Each of two parties would not voluntarily enter into an

exchange if it made either of them worse off, now would they?

The same principles apply at the national and international

level: International trade allows countries to sell their exports

abroad and get a higher price, and to buy things from abroad

more cheaply than they could produce at home.

In addition, trade gives a country’s consumers access to a

greater variety of goods – including goods they might not be

able to get at all. For example, U.S. consumers enjoy a variety

of fresh produce year-round. This would not be possible without international trade. H O W PEO PLE IN TERACT

A market economy is “decentralized,” meaning that there is no

Principle #6: Markets Are Usually A Good

government committee that makes the decisions about what Way to Organize ze Economic Activity

goods to produce and so forth. Instead, many households and

§ Market: a group of buyers and sellers

(need not be in a single location)

firms make their own decisions:

§ “Organize economic activity” means determining § what goods to produce § how to produce them

* Each of many households decides who to work for and what § how much of each to produce § who gets them goods to buy.

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 20

* Each of many firms decides whom to hire and what goods to produce.

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561 H O W PEO PLE IN TERACT

In all versions of this textbook except Brief Principles of

Principle #6: Markets Are Usually A Good

Macroeconomics, market efficiency and the invisible hand are Way to Organize ze Economic Activity

covered more thoroughly in Chapter 7.

§ A market economy allocates resources through

the decentralized decisions of many households

and firms as they interact in markets.

§ Famous insight by Adam Smith in

The Wealth of Nations (1776):

Each of these households and firms

acts as if “led by an invisible hand”

to promote general economic well-being.

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 21 H O W PEO PLE IN TERACT

Principle #6: Markets Are Usually A Good Way to Organize ze Economic Activity

§ The invisible hand works through the price system:

§ The interaction of buyers and sellers determines prices.

§ Each price reflects the good’s value to buyers

and the cost of producing the good.

§ Prices guide self-interested households and

firms to make decisions that, in many cases,

maximize society’s economic well-being.

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 22 H O W PEO PLE IN TERACT

[“Govt” is an abbreviation for government. Throughout all of

Principle #7: Governments ts Can Someti times

the Premium PowerPoint chapters, I try to use abbreviations Improve Market t Outcomes

the way a thoughtful instructor would use them if writing on a

§ Important role for govt: enforce property rights (with police, courts)

chalkboard. If you prefer to spell the word out, just use your

§ People are less inclined to work, produce, invest,

or purchase if large risk of their property being

mouse to highlight “govt” and then type out the full word.] stolen.

Two examples of the idea in the second bullet point:

A restaurant won’t serve meals if customers do not pay before

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 23 they leave.

A music company won’t produce CDs if too many people

avoid paying by making illegal copies.

Many fledging market economies are struggling through the

transition from central planning because they have not

developed institutions that protect and enforce property rights.

The British news magazine The Economist has lots of current

examples of this. An older but still interesting example comes

from a column that Mankiw wrote in the June 12, 2000 issue

of Fortune magazine entitled “Ukraine: How Not To Run An Economy.”

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561 H O W PEO PLE IN TERACT

Principle #7: Governments ts Can Someti times Improve Market t Outcomes

§ Market failure: when the market fails to allocate

society’s resources efficiently § Causes:

§ Externalities, when the production or consumption

of a good affects bystanders (e.g. pollution)

§ Market power, a single buyer or seller has

substantial influence on market price (e.g. monopoly)

§ In such cases, public policy may promote efficiency.

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 24 H O W PEO PLE IN TERACT

Principle #7: Governments ts Can Someti times Improve Market t Outcomes

§ Govt may alter market outcome to promote equity

§ If the market’s distribution of economic well-being

is not desirable, tax or welfare policies can change

how the economic “pie” is divided.

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 25

The items in this list are meant to get students thinking about A A C C T I V V E E L L E E A A R R N I N G G 2 D iscu ssion Q Q u estion s

Principles 6 and 7 in the context of specific examples, and to

In each of the following situations, what is the

government’s role? Does the government’s

generate discussion rather than arrive at definitive answers.

intervention improve the outcome?

NOTE: Discussing the entire list would consume a lot of

a. Public schools for K-12

b. Workplace safety regulations

class time (20-25 minutes). Two would suffice. Pick your

c. Public highways

favorite two and delete the others. Of course, you can skip

d. Patent laws, which allow drug companies to

charge high prices for life-saving drugs

this slide entirely if you wish to get through the chapter as quickly as possible. 26

Here are some notes which might help guide the discussion:

a. Public schools. The alternative would be private schools.

The cost of education would be concentrated among those with

school-aged children, rather than spread over all taxpayers, so

the price per child would likely be high. Some families would

not be able to afford to enroll their children in schools, and

would either home-school the children or raise them without

education. Is the benefit to society of having an educated

population large enough to justify making people without

children share in the cost? Could the private sector provide

education more efficiently (either at lower cost or higher

quality) than the public sector?

b. Workplace safety regulations. Without such regulations,

would firms provide a safe environment for their workers?

Some students will say “no – look at how bad working

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

conditions are in poor countries which have no safety

regulations.” Another view is dropping such regulations

would make workers better off. Workers may view the safety

of their work environment as part of their wage: the less safe

the environment at a specific firm, the higher the wage the firm

will have to offer to make workers willing to work there. If

workers vary with respect to their tolerance for unsafe

conditions, then workers with a high risk tolerance would be

better off if given the option to work for higher wages in

factories that aren’t as safe. Such workers would be worse off

if the government required all firms to provide equally safe conditions.

c. Public highways. The alternative would be toll highways

operated by the private sector. People who use highways more

would pay more, and people that use them less would pay less,

which seems fairer than having everyone pay equally for

highways. (Actually, everyone does not pay equally - people

who use public roads more buy more gas, and therefore pay

more gas tax.) If there are external benefits to society of

having a national highway system, then the private sector

would under-provide this good.

d. Patent laws. I’ve kind of loaded the question with the

wording on the slide. If you wish, change it to just “Patent

laws.” Is it fair that drug companies charge such high prices

for drugs that some people need to stay alive? If drug prices

are regulated, how might pharmaceutical firms respond?

The principles of H OW TH E ECO N OM Y Y AS A WH O LE WO RKS

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

H O W TH E ECO N O M Y AS A WH O LE WO RKS

“Rich countries” refers to countries like the U.S., Japan, and Principle #8: A countr tr y’s standard of f living Germany. depends on its ability ty to to produce goods & services.

§ Huge variation in living standards across

“Poor countries” refers to countries like India, Indonesia, and countries and over time:

§ Average income in rich countries is more than Nigeria.

ten times average income in poor countries.

§ The U.S. standard of living today is about

eight times larger than 100 years ago.

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 28

H O W TH E ECO N O M Y AS A WH O LE WO RKS Principle #8: A countr tr y’s standard of f living depends on its ability ty to to produce goods & services.

§ The most important determinant of living standards:

productivity, the amount of goods and services produced per unit of labor.

§ Productivity depends on the equipment, skills, and

technology available to workers.

§ Other factors (e.g., labor unions, competition from

abroad) have far less impact on living standards.

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 29

H O W TH E ECO N O M Y AS A WH O LE WO RKS

Principle #9: Prices rise when th the government t prints to to o much money.

§ Inflation: increases in the general level of prices.

§ In the long run, inflation is almost always caused by

excessive growth in the quantity of money, which

causes the value of money to fall.

§ The faster the govt creates money,

the greater the inflation rate.

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 30

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

H O W TH E ECO N O M Y AS A WH O LE WO RKS

While the long-run effect of increasing the quantity of money Principle #10: : Society ty faces a short- t-run

is inflation, the short-run effects are more complicated - and tr tr adeoff

ff between inflation and unemployment

controversial. However, most mainstream economists believe

§ In the short-run (1 – 2 years),

many economic policies push inflation and

the following: An increase in the quantity of money causes

unemployment in opposite directions.

§ Other factors can make this tradeoff more or less

spending to rise, which causes prices to rise, which induces

favorable, but the tradeoff is always present.

firms to produce more goods and services, which requires that

they hire more workers. Hence, in the short-run, increasing

the quantity of money causes inflation to rise, but

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 31 unemployment to fall.

Of course, REDUCING the quantity of money would have the

opposite effects (inflation would fall, while unemployment would rise) in the short run.

Keep in mind, though, the lesson from Principle #9: In the

long run, changing the quantity of money only affects

inflation. We will learn in a later chapter what determines the

rate of unemployment in the long run, and we will see that it

has nothing to do with the quantity of money.

The second bullet addresses the following point: In some

decades, due to factors outside of the control of policymakers,

inflation and unemployment are both high (e.g. 1970s) – or

low (e.g. 1990s). Yet, given these other factors, policymakers

can always reduce unemployment temporarily by creating

more inflation, or vice versa.

FYI: H ow to Read You r Textb ook

Most new college students have not been taught good study 1. Read before class.

skills, yet we professors often assume they have such skills.

You’ll get more out of class.

This is the first of four slides that summarize an FYI box

2. Summarize, don’t highlight.

Highlighting is a passive activity that won’t improve

which describes proven strategies for learning and retention.

your comprehension or retention.

Instead, summarize each section in your own

words. Then, compare your summary to the one at the end of the chapter.

If you’re pressed for time, you can of course skip these slides,

but please urge your students to read this FYI box.

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 32

But if you can spare 30 minutes of class time, there’s a very

effective activity you can do in class which lets students see

for themselves the power of active reading and teaching a

partner. I describe this activity in the notes section of the

fourth “FYI: How to Read Your Textbook” slide. This

activity could replace showing these four slides in class,

though your students should still read the corresponding FYI box in the book.

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

FYI: H ow to Read You r Textb ook

If you do not like “They are often good practice for the 3. Test yourself.

exams,” please feel free to delete it. I’ve found, though, that

Try the “Quick Quiz” that follows each section before

moving on to the next section.

students are more motivated to work practice problems when

Write your answers down, compare them to the

answers in the back of the book. If your answers

they think that doing so will help them earn a higher score on

are incorrect, review the section before moving on. the exam.

4. Practice, practice, practice.

Work through the end-of-chapter review questions

and problems. They are often good practice for the

exams. And the more you use your new knowledge, the more solid it will become.

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 33

FYI: H ow to Read You r Textb ook

If your classroom computer has a live internet connection, you 5. Go online.

should be able to click on the link and visit the textbook’s

The book comes with excellent web resources,

including practice quizzes, tools to strengthen your

website. It’s worth taking 2-3 minutes of class time to show

graphing skills, helpful video clips, and other

resources to help you learn the textbook material students the resources there.

more easily and effectively. Visit:

http://academic.cengage.com/economics/mankiw 6. Study in groups.

Get together with a few classmates to review each

chapter, quiz each other, and help each other understand the material.

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 34

FYI: H ow to Read You r Textb ook

Here’s the activity I mentioned a few slides back. I have used 7. Teach someone.

it many times with terrific results.

The best way to learn something is to teach it to

someone else, such as a study partner or friend.

8. Don’t skip the real world examples.

Read the Case Studies and “In The News” boxes in

Find two newspaper articles on topical economic issues. The

each chapter. They will help you see how the new

terms, concepts, models, and graphs apply to the

articles must be (1) short enough that a beginning college

real world. As you read the newspaper or watch the

student can read either of them in 10 minutes or less, (2)

evening news, see if you can find the connections

with what you’re learning in the textbook.

appropriate for the lay reader, and (3) very interesting. Make

enough copies for all students in your class. Use different

TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 35

colored paper for each article, e.g. yellow for Article 1 and

blue for Article 2. In class, instruct students to pair up. In

each student pair, one student is assigned Article 1, the other

assigned Article 2. Tell students they will have 15 minutes to

read their assigned article. Then, each student will have 5

minutes to teach the contents of his or her article to his or her

partner. Tell students it is not acceptable to merely give a

paragraph-by-paragraph summary when teaching their articles to their partner.

Use your timer or a watch to announce when the 15 minutes

are up and it’s time to start teaching. Five minutes later,

announce when it’s time for the other student to teach his/her

article. Five minutes later, stop the activity and re-group as a

class. Ask your students the following four questions.

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

PowerPoint Lecture Notes for Chapter 2:

Thinking Like An Economist

Principles of Economics 5th edition, by N. Gregory Mankiw

Premium PowerPoint Slides by Ron Cronovich

Besides introducing students to the economic way of thinking, C H A P T E R 2

this chapter introduces the Production Possibilities Frontier,

Th in k in g Lik e An Econ om ist

the first of many graphs covered in the textbook. The PPF

will be used extensively in Chapter 3 (Interdependence and EcP Po R R I Nn N C C I o P P L L Em S S O O i F cs the Gains from Trade). N. N Gr G eg e ory Ma M nkiw Premium PowerPoint Slides

It would be helpful to ask your students to bring calculators to by Ron Cronovich

© 2009 South-Western, a part of Cengage Learning, all rights reserved

class on the day you cover this chapter (as well as Chapter 3). In th is ch ap ter,

look for th e an swers to th ese q u estion s:

§ What are economists’ two roles? How do they differ?

§ What are models? How do economists use them?

§ What are the elements of the Circular-Flow Diagram?

What concepts does the diagram illustrate?

§ How is the Production Possibilities Frontier related

to opportunity cost? What other concepts does it illustrate?

§ What is the difference between microeconomics and

macroeconomics? Between positive and normative? 5

T h e Econ om ist as Scien tist § Economists play two roles:

1. Scientists: try to explain the world

2. Policy advisors: try to improve it

§ In the first, economists employ the scientific method,

the dispassionate development and testing of

theories about how the world works.

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 6

Assu m p tion s & M od els

§ Assumptions simplify the complex world, make it easier to understand.

§ Example: To study international trade,

assume two countries and two goods.

Unrealistic, but simple to learn and

gives useful insights about the real world.

§ Model: a highly simplified representation of a more complicated reality.

Economists use models to study economic issues.

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 7

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

Som e Fam iliar M od els A road map

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 8

Som e Fam iliar M od els A model of human anatomy from high school biology class

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 9

Som e Fam iliar M od els A model airplane

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 10

Som e Fam iliar M od els The model teeth at the Don’t f or get dentist’s office t o f loss!

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 11

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561 O u r Fir st M od el:

Th e Ci rcu lar-Flow D iagram

§ The Circular-Flow Diagram: a visual model of

the economy, shows how dollars flow through

markets among households and firms § Two types of “actors”: § households § firms § Two markets:

§ the market for goods and services

§ the market for “factors of production”

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 12

The “definition” of capital shown on this slide (“buildings Factors of Prod u ction

§ Factors of production: the resources the

and machines”) is the same that appears in the corresponding

economy uses to produce goods & services, including

section of the chapter. A more formal definition will be § labor § land

provided in subsequent chapters.

§ capital (buildings & machines used in production)

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 13

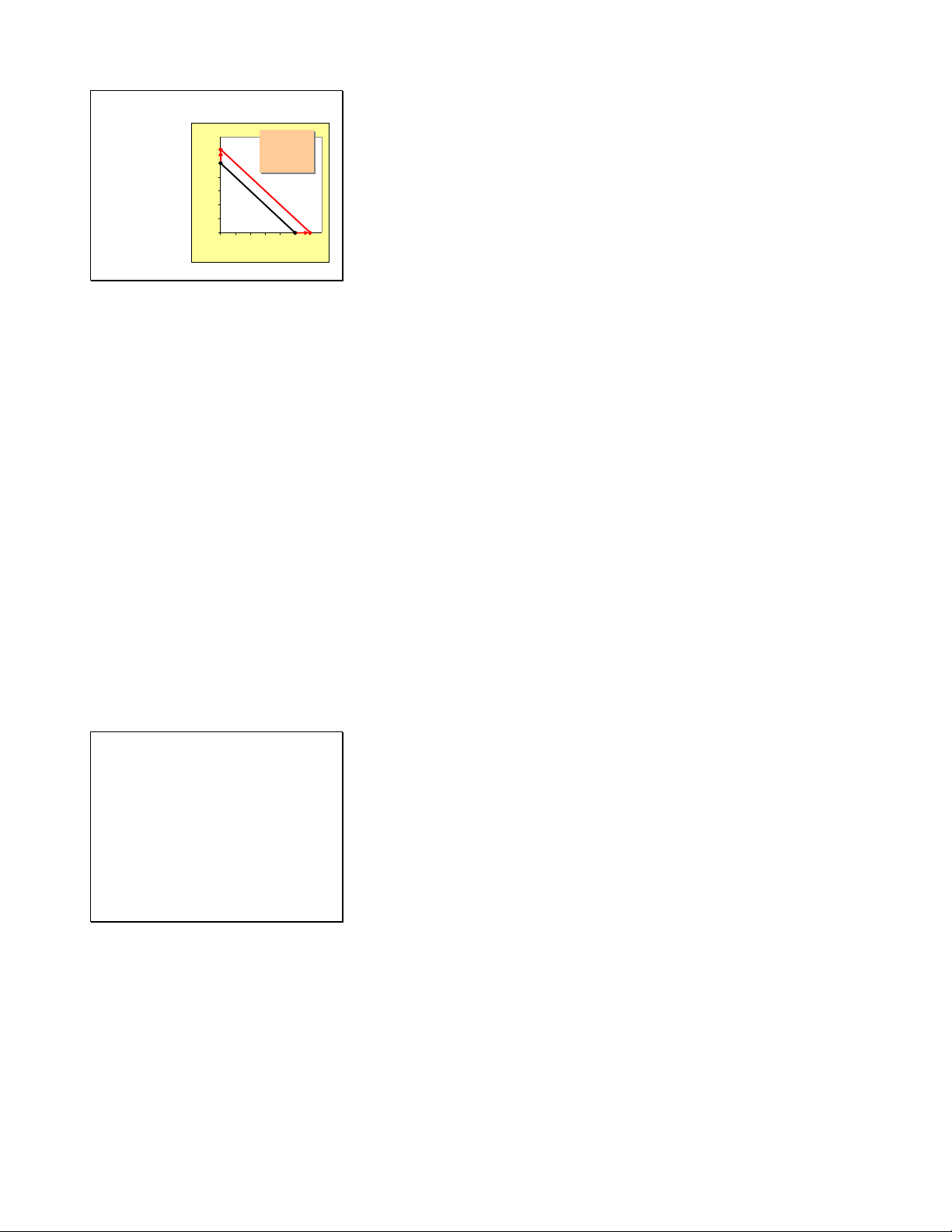

FIG URE 1: The Circular-Flow Diagram

This and the following slide build the Circular-Flow Diagram Households: piece by piece. § Own th th e fa fa ctors of p f p roduction, sell/r /r ent th t th em to to fi fi rms fo fo r income § Buy and c c onsume g g oods & services Firms Households Firms: § Buy/h /h ire facto to rs of production, , use them to to produce goods and services § Sell g g oods & & services

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 14

FIG URE 1: The Circular-Flow Diagram

In this diagram, the green arrows represent flows of Revenue Spending Markets for

income/payments. The red arrows represent flows of goods G & S Goods & G & S sold Services bought

& services (including services of the factors of production in

the lower half of the diagram). Firms Households Factors of Labor, land, production Markets for capital

To keep the graph simple, we have omitted the government, Factors of Wages, rent, Production Income

financial system, and foreign sector, as discussed on the next profit

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 15 slide.

You may wish to change the order in which the elements

appear. To do so, look for “Custom Animation” in your version of PowerPoint.

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561 O u r Secon d M od el:

Th e P rod u ct ion Possib ili ties Fron tier

§ The Production Possibilities Frontier (PPF):

a graph that shows the combinations of

two goods the economy can possibly produce

given the available resources and the available technology § Example:

§ Two goods: computers and wheat

§ One resource: labor (measured in hours)

§ Economy has 50,000 labor hours per month available for production.

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 16 PPF Exam p le Suggestion:

§ Producing one computer requires 100 hours labor.

Show first row. Explain how we get the production numbers

§ Producing one ton of wheat requires 10 hours labor. Employment of

from the employment numbers. Then, show the rest of the Production labor hours

employment numbers, and give students 3 minutes to Computers Wheat Computers Wheat A 50,000 0 500 0

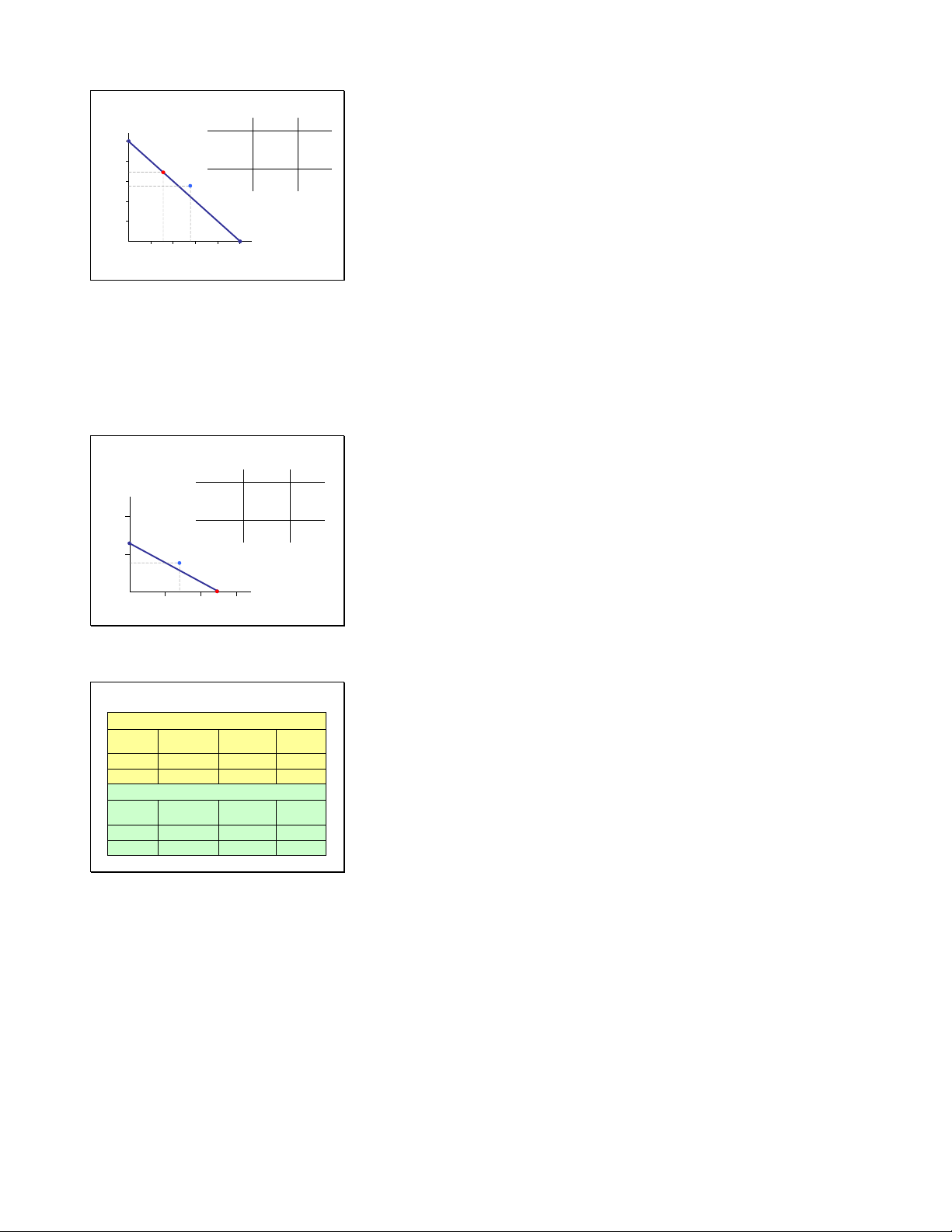

compute the production numbers for each employment B 40,000 10,000 400 1,000 allocation. C 25,000 25,000 250 2,500 D 10,000 40,000 100 4,000 E 0 50,000 0 5,000 PPF Exam p le Wheat Point Production (tons) on Com- 6,000 graph Wheat puters E 5,000 A 500 0 D 4,000 B 400 1,000 3,000 C C 250 2,500 2,000 D 100 4,000 B 1,000 E 0 5,000 A 0 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 Computers

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 18

This exercise leads students to discover for themselves that A A C C T I V E E L L E E A A R R N N I N G G 1 P oin t s off t t h e P P PF

points under the PPF are possible but inefficient, while points

A. On the graph, find the point that represents

(100 computers, 3000 tons of wheat), label it F. above it are not possible.

Would it be possible for the economy to produce

this combination of the two goods? Why or why not?

B. Next, find the point that represents

(300 computers, 3500 tons of wheat), label it G.

Would it be possible for the economy to produce

this combination of the two goods? 19

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561 A A C C T I V E E L L E E A A R R N N I N G G 1 An sw ers Wheat § Point F: (tons) 100 computers, 6,000 3000 tons wheat 5,000 § Point F requires 4,000 40,000 hours 3,000 of labor. F Possible but 2,000 not efficient: 1,000 could get more 0 of either good 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 w/o sacrificing Computers any of the other. 20 A A C C T I V E E L L E E A A R R N N I N G G 1 An sw ers Wheat § Point G: (tons) 300 computers, 6,000 3500 tons wheat 5,000 § Point G requires 4,000 G 65,000 hours 3,000 of labor. 2,000 Not possible 1,000 because economy 0 only has 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 50,000 hours. Computers 21

Th e P PF: W h at We Kn ow S o Far

Points on the PPF (like A – E) § possible

§ efficient: all resources are fully utilized

Points under the PPF (like F) § possible

§ not efficient: some resources underutilized

(e.g., workers unemployed, factories idle)

Points above the PPF (like G) § not possible

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 22

Th e P PF an d O p p ort u n ity Cost

§ Recall: The opportunity cost of an item

is what must be given up to obtain that item.

§ Moving along a PPF involves shifting resources

(e.g., labor) from the production of one good to the other.

§ Society faces a tradeoff: Getting more of one

good requires sacrificing some of the other.

§ The slope of the PPF tells you the opportunity

cost of one good in terms of the other.

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 23

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

Th e PPF an d O p p ortu n ity C ost

Here, the “rise” is a negative number, because, as you move The slope of a line

to the right, the line falls (meaning wheat output is reduced). Wheat (tons) equals the –1000 6,000 slope = = –10 “rise over the run,” 100 the amount the line 5,000 rises when you 4,000

Moving to the right involves shifting resources from the move to the right 3,000 by one unit.

production of wheat (which causes wheat output to fall) to the 2,000 Here, the 1,000 opportunity cost of

production of computers (which causes computer production 0 a computer is 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 10 tons of wheat.

to rise). Producing an additional computer requires the Computers

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 24

resources that would otherwise produce 10 tons of wheat.

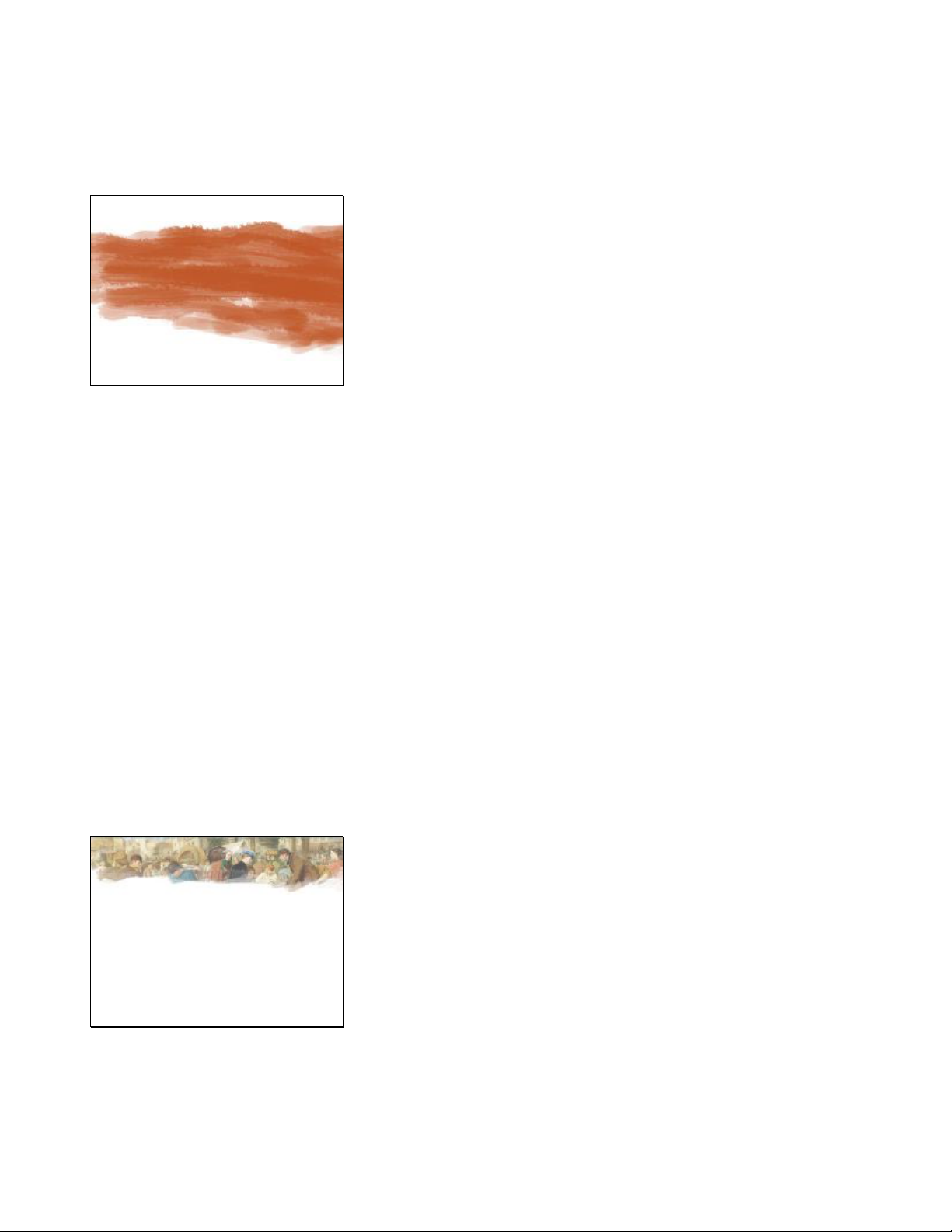

This exercise reinforces the material on the preceding slide. It A A C C T I V E E L L E E A A R R N N I N G G 2 P PF a

a n d O p p ortu n ity C ost

is especially useful if you plan to cover Chapter 3

In which country is the opportunity cost of cloth lower? FRANCE ENGLAND

(Interdependence and the Gains from Trade) after completing Wine Wine 60 0 600 Chapter 2. 50 0 500 40 0 400 30 0 300 20 0 200 10 0 100 0 0 0 10 0 2 00 3 0 0 40 0 0 100 200 300 400 Cloth Cloth25

There are two ways to get the answer. A A C C T I V E E L L E E A A R R N N I N G G 2 An sw ers

The hard way is to compute the slope of both PPFs. The

England, because its PPF is not as steep as France’s. FRANCE ENGLAND

slope of France’s PPF equals -600/300 = -2, meaning that Wine Wine 60 0 600

France must give up two units of wine to get an additional 50 0 500 40 0 400

unit of cloth. The slope of England’s PPF = -200/300 = -2/3, 30 0 300 20 0 200

meaning that England only must sacrifice 2/3 of a unit of 10 0 100 0 0

wine to get an additional unit of cloth. Thus, the opportunity 0 10 0 2 00 3 0 0 40 0 0 100 200 300 400 Cloth Cloth26

cost of cloth is lower in England than France.

The question, however, does not ask for the numerical values

of the opportunity cost of cloth in the two countries. It only

asks which country has a lower opportunity cost of cloth.

There is an easy way to determine the answer. Students must

remember that the slope of the PPF equals the opportunity

cost of the good measured on the horizontal axis. Then,

students can simply “eyeball” the two PPFs to determine

which is steepest. From the graphs show, it’s pretty easy to

see that England’s PPF isn’t as steep, and therefore the

opportunity cost of cloth is lower in England than in France.

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

The PPF shows the tradeoff between the outputs of different

Econ om ic G row th an d th e PPF With additional

goods at a given time, but the tradeoff can change over time. Wheat Economic (tons) resources or an Economic growth shifts 6,000 improvement in growth shifts t t h h e e P P P P F F technology, 5,000 o o u u ttw w a a rrd d .. the economy can 4,000

For example, over time, the economy might get more workers produce more 3,000 computers,

(or more factories or more land). Or, a more efficient 2,000 more wheat, 1,000 or any combination

technology might be invented. Both events – an increase in in between. 0 0 100 200 300 400 500 600

the economy’s resources or an improvement in technology – Computers

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 27

cause an expansion in the set of opportunities. That is, both

allow the economy to produce more of one or both goods.

This is a simple example of economic growth, an important

subject that gets its own chapter in the macroeconomics portion of the textbook.

In the example shown on this slide, economic growth causes a

parallel outward shift of the PPF. Since the new PPF is

parallel to the old one, the tradeoff between the two goods is

the same. However, this need not always be the case. For

example, if a new technology had more impact on the

computer industry than on the wheat industry, then the

horizontal (computer) intercept would increase more than the

vertical (wheat) intercept, and the PPF would become flatter:

the opportunity cost of computers would fall, because the

technology has made them relatively cheaper (relative to

wheat). Going into more detail here is probably beyond the scope of this chapter.

T h e Sh ap e of th e PPF

§ The PPF could be a straight line, or bow-shaped

§ Depends on what happens to opportunity cost

as economy shifts resources from one industry to the other.

§ If opp. cost remains constant, PPF is a straight line.

(In the previous example, opp. cost of a

computer was always 10 tons of wheat.)

§ If opp. cost of a good rises as the economy

produces more of the good, PPF is bow-shaped.

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 28

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

Wh y th e PPF M igh t Be Bow -Sh ap ed r As the economy e e shifts resources B from beer to mountain bikes: § PPF becomes steeper § opp. cost of mountain bikes increases Mountain Bikes

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 29

Wh y th e PPF M igh t Be Bow -Sh ap ed

Here, we are using “workers” for the more general

“resources,” to keep things simple and consistent with the At point A, r A A tt A A ,, o o p p p p .. c c o o s s tt o o ff e A mtn bikes is low. most workers are e mtn bikes is low. B previous examples. producing beer, even those that are better suited to building bikes. So, do not have to give up much beer to get more bikes. Mountain Bikes

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 30

Wh y th e PPF M igh t Be Bow -Sh ap ed At B, most workers r e A A tt B B ,, o o p p p p .. c c o o s s tt are producing bikes. e B of mt t n biikes The few left in beer is h h ig g h h .. are the best brewers. Producing more B bikes would require shifting some of the best brewers away from beer production, would cause a big Mountain drop in beer output. Bikes

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 31

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

Wh y th e PPF M igh t Be Bow -Sh ap ed

The bow-shaped PPF is more realistic. However, the linear

§ So, PPF is bow-shaped when different workers

PPF is simpler to work with, and we can learn a lot about how

have different skills, different opportunity costs

of producing one good in terms of the other.

the economy works using the linear PPF. In Chapter 3, we

§ The PPF would also be bow-shaped when

there is some other resource, or mix of

will use a linear PPF to show how trade can make two

resources with varying opportunity costs

(E.g., different types of land suited for

countries (or two individuals) better off. different uses).

Note: In the “Problems and Applications” at the end of the

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 32

chapter, problem 4 asks students to construct a PPF for an

economy with three different workers (Larry, Moe, and

Curly), each with a different opportunity cost. The PPF ends

up having three line segments (one for each worker), which--

very roughly--approximates a bow-shape. After students

work through and understand this problem, it should not be

hard for them to understand the following: the more different

kinds of workers (or, more generally, resources) there are, the

closer the PPF will resemble a smooth bow shape. In an

actual economy like the U.S., there are millions of different

workers with different opportunity costs, so a smooth bow-

shaped PPF is a nearly perfect approximation to the actual PPF. T h e PPF: A Su m m ary

§ The PPF shows all combinations of two goods

that an economy can possibly produce,

given its resources and technology.

§ The PPF illustrates the concepts of

tradeoff and opportunity cost, efficiency and inefficiency,

unemployment, and economic growth.

§ A bow-shaped PPF illustrates the concept of increasing opportunity cost.

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 33

M icroecon om ics an d Macroecon om ics

§ Microeconomics is the study of how households

and firms make decisions and how they interact in markets.

§ Macroeconomics is the study of economy-wide

phenomena, including inflation, unemployment, and economic growth.

§ These two branches of economics are closely

intertwined, yet distinct – they address different questions.

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 34

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

T h e Econ om ist as Policy Ad visor

§ As scientists, economists make positive statements,

which attempt to describe the world as it is.

§ As policy advisors, economists make normative statements,

which attempt to prescribe how the world should be.

§ Positive statements can be confirmed or refuted, normative statements cannot.

§ Govt employs many economists for policy advice.

E.g., the U.S. President has a Council of Economic

Advisors, which the author of this textbook chaired from 2003 to 2005. 35 A A C C T I V E E L L E E A A R R N N I N G G 3 Id en t ifyin g p p ositive vs. n . n orm ative

Which of these statements are “positive” and which

are “normative”? How can you tell the difference?

a. Prices rise when the government increases the quantity of money.

b. The government should print less money.

c. A tax cut is needed to stimulate the economy.

d. An increase in the price of burritos will cause an

increase in consumer demand for video rentals. 36 A A C C T I V E E L L E E A A R R N N I N G G 3 A A C C T I V E E L L E E A A R R N I N G G 3 An sw ers An sw ers

a. Prices rise when the government increases the

c. A tax cut is needed to stimulate the economy. quantity of money.

Normative – another value judgment.

Positive – describes a relationship, could use

d. An increase in the price of burritos will cause an

data to confirm or refute.

increase in consumer demand for video rentals.

b. The government should print less money.

Positive – describes a relationship.

Normative – this is a value judgment, cannot be

Note that a statement need not be true to be confirmed or refuted. positive. 37 38

Wh y Econ om ists D isagree

§ Economists often give conflicting policy advice.

§ They sometimes disagree about the validity of

alternative positive theories about the world.

§ They may have different values and, therefore,

different normative views about what policy should try to accomplish.

§ Yet, there are many propositions about which most economists agree.

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 39

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

Proposition s ab ou t Wh ich M ost

This slide and the next show several of the 14 propositions

Econ om ists Agree (and % w h o agree)

appearing in Table 1 of the chapter. For the full list, see

§ A ceiling on rents reduces the quantity and

quality of housing available. (93%) Table 1 in the chapter.

§ Tariffs and import quotas usually reduce general economic welfare. (93%)

§ The United States should not restrict employers

Note: Some of the terms appearing in these statements have

from outsourcing work to foreign countries. (90%)

§ The United States should eliminate agriculture

not yet been defined, so you may wish to define them to subsidies. (85%)

students as they appear on the screen. continued…

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 40

If you’re pressed for time, delete the following slide and refer

your students to Table 1 in the chapter.

Proposition s ab ou t Wh ich M ost

Econom ists Agree (an d % agreein g)

§ The gap between Social Security funds and

…Continued from previous slide.

expenditures will become unsustainably large

within the next fifty years if current policies remain unchanged. (85%)

§ A large federal budget deficit has an adverse effect on the economy. (83%)

§ A minimum wage increases unemployment among

young and unskilled workers. (79%)

§ Effluent taxes and marketable pollution permits

represent a better approach to pollution control

than imposition of pollution ceilings. (78%)

THINKING LIKE AN ECONOMIST 41

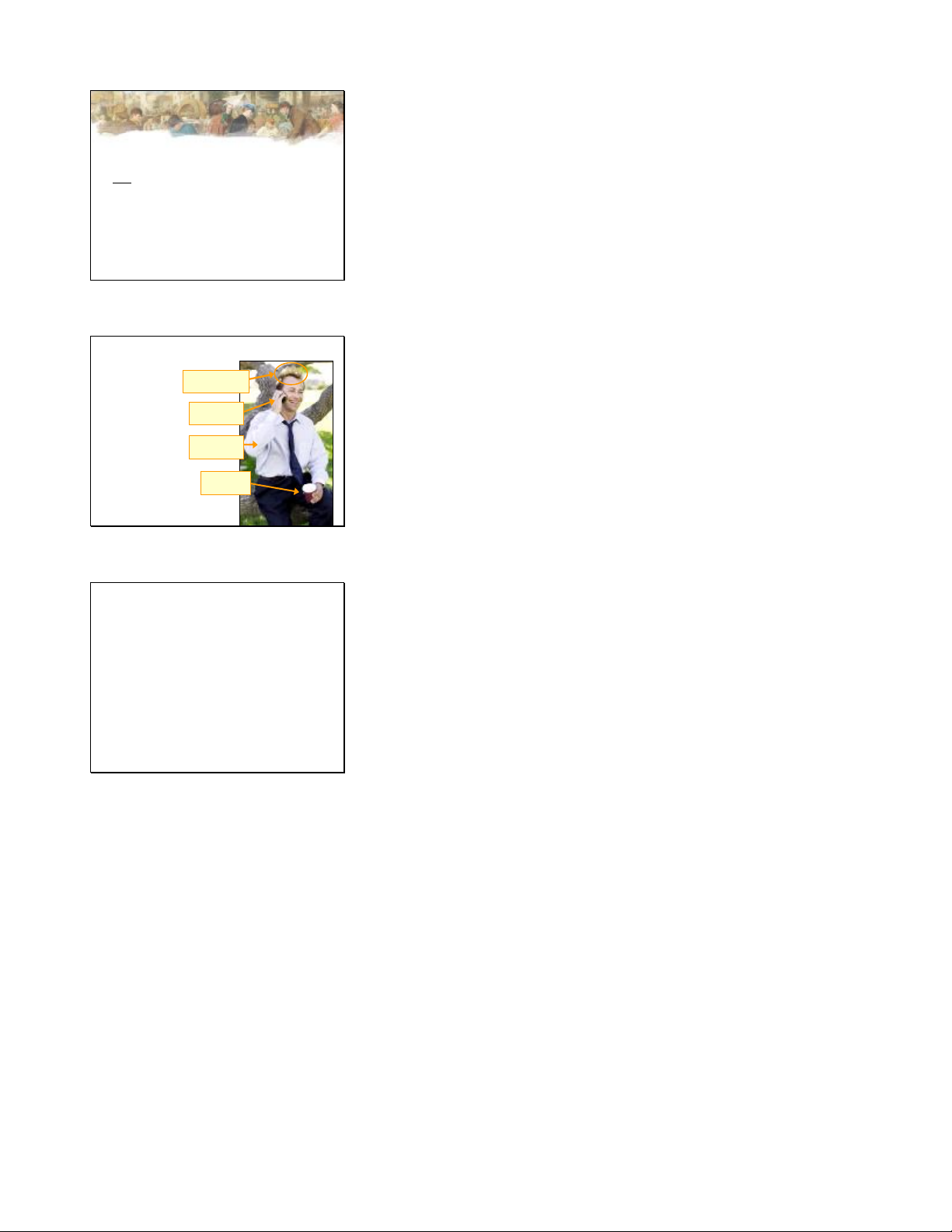

FYI: Wh o Stu d ies Econ om ics?

This FYI lists people who studied economics in college. It is a

§ Ronald Reagan, President of the United States

§ Barbara Boxer, U.S. Senator

fun way to lighten up the lecture. On the other hand, if you’re

§ Sandra Day-O’Connor, Former Supreme Court Justice

§ Anthony Zinni, Former General, U.S. Marine Corps

running short on time, this is a good candidate to skip –

§ Kofi Annan, Former Secretary General, United Nations

§ Meg Witman, Chief Executive Officer, eBay

students will readily find it when they read the chapter.

§ Steve Ballmer, Chief Executive Officer, Microsoft

§ Arnold Schwarzenegger, Governor of California, Actor

§ Ben Stein, Political Speechwriter, Actor, Game Show Host

§ Mick Jagger, Singer for the Rolling Stones

(Due to space limitations, this slide omits a few of the names § John Elway, NFL Quarterback § Tiger Woods, Golfer

in the corresponding FYI box in the text.)

§ Diane von Furstenburg, Fashion Designer 42 CH APTER SUM MARY

§ As scientists, economists try to explain the world

using models with appropriate assumptions.

§ Two simple models are the Circular-Flow Diagram

and the Production Possibilities Frontier.

§ Microeconomics studies the behavior of

consumers and firms, and their interactions in

markets. Macroeconomics studies the economy as a whole.

§ As policy advisers, economists offer advice on how to improve the world. 43

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

PowerPoint Lecture Notes for Chapter 3:

Interdependence and the Gains from Trade

Principles of Economics 5th edition, by N. Gregory Mankiw

Premium PowerPoint Slides by Ron Cronovich C H A P T E R 3

Please ask your students in advance to bring calculators

to class. This PowerPoint chapter includes simple in-class

In terd ep en d en ce an d th e

exercises which lead students to see for themselves the gains G ain s from Trad e

from trade arising from comparative advantage. EcP Po R R I n N N C C I o P P L L Em S S O O i F cs N. N Gr G eg e ory Ma M nkiw

This PowerPoint chapter covers the same topics as Chapter 3 Premium PowerPoint Slides

in the textbook (comparative & absolute advantage, the gains by Ron Cronovich

© 2009 South-Western, a part of Cengage Learning, all rights reserved

from trade), but using a different example and a different

approach that is likely to benefit your students. The textbook

presents these topics using an example involving two

individual producers (the farmer & rancher). After the

example, the textbook states that its lessons apply to

countries as well as individual producers. This PowerPoint

presentation takes the opposite approach, illustrating the

concepts with an example involving two countries, and then

states that that the lessons apply to individuals as well as

countries. Seeing the analysis both ways, and seeing a

different example in class than in the textbook, will help

students better learn these concepts.

The example in this PowerPoint chapter builds on the PPF

example introduced in the Chapter 2 PowerPoint. (It is not

essential to cover the Chapter 2 PowerPoint before this one, though.)

This PowerPoint omits “Should Tiger Woods Mow His Own

Lawn?” It’s a great example of comparative advantage, but

it does not introduce any new concepts, and students can

easily understand it on their own.

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561 In th is ch ap ter,

look for th e an sw ers to th ese q u estion s:

§ Why do people – and nations – choose to be economically interdependent?

§ How can trade make everyone better off?

§ What is absolute advantage?

What is comparative advantage?

How are these concepts similar? How are they different? 5 In terd ep en d en ce Every day hair gel from you rely on Cleveland, OH many people from around cell phone the world, from Taiwan most of whom you’ve never met, dress shirt from China to provide you with the goods and services coffee from Kenya you enjoy. In terd ep en d en ce

§ One of the Ten Principles from Chapter 1:

Trade can make everyone better off.

§ We now learn why people – and nations – choose to be interdependent,

and how they can gain from trade.

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 7

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

The lessons illustrated by this international trade example O u r Exam p le

§ Two countries: the U.S. and Japan

also apply to trade between two individual producers. Note

§ Two goods: computers and wheat

that this chapter in the textbook does the reverse: It develops

§ One resource: labor, measured in hours

the lessons in the context of an example involving two

§ We will look at how much of both goods

each country produces and consumes

individual producers, and then states that the lessons also

§if the country chooses to be self-sufficient

§if it trades with the other country

apply to international trade. So, between this PowerPoint

and the textbook chapter, students will see the same concepts

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 8

and lessons developed in two different but entirely consistent approaches and examples.

The example here is highly contrived and unrealistic in order

to illustrate complex concepts as simply as possible. The

example has some qualities that make it especially valuable:

* The two goods are fundamentally different (one is

agricultural, the other manufactured), which makes gains

from trade based on comparative advantage very likely. An

example using more similar goods, say laptop computers and

MP3 players, would not be appropriate for this chapter

because it would more likely give rise to inter-industry trade,

and the gains would likely arise from a source other than

comparative advantage (probably increasing returns to scale).

* In the example here, it turns out that the U.S. has an

absolute advantage in both goods, yet both countries gain

from trade. Students see, therefore, that comparative

advantage, not absolute advantage, is what’s necessary for

trade to be mutually beneficial.

* In the real world, one often sees gains from trade based on

comparative advantage occurring between countries that are

very different – such as between rich industrialized countries

and poor developing countries. This example shows that

trade based on comparative advantage can also occur

between countries that are at similar levels of

industrialization and income. (Of course, the U.S. and Japan

are very different; but they are far more similar than are, say, the U.S. and Botswana.)

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

If you just covered Chapter 2, point out to your students that

Prod u ction Possib ilities in t h e U.S.

§ The U.S. has 50,000 hours of labor

the U.S. PPF here is the same as in the Chapter 2

available for production, per month. PowerPoint. § Producing one computer requires 100 hours of labor. § Producing one ton of wheat requires 10 hours of labor.

Warn students that, in a few moments, they will be asked to

derive Japan’s PPF. They will need to follow the same steps

that you are about to show for deriving the U.S. PPF.

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 9

Deriving the intercepts, or endpoints of the PPF: Th e U.S. PPF Wheat (tons) The U.S. has enough labor 5,000 to produce 500 computers,

The U.S. has 50,000 labor hours. or 5000 tons of wheat, 4,000 or any combination along 3,000 the PPF. 2,000

It takes 100 hours to produce a computer. If the U.S. uses all 1,000

its labor to produce computers, then it will produce Computers 0 100 200 300 400 500

50,000/100 = 500 computers. Hence, the horizontal intercept

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 10 is (500 computers, 0 wheat).

It takes 10 hours to produce a ton of wheat. If the U.S. uses

all its labor to produce wheat, then it will produce 50,000/10

= 5000 tons of wheat. Hence, the vertical intercept is

(0 computers, 5000 tons of wheat).

The PPF is the straight line that connects the two endpoints.

Of course, the U.S. could choose a different point. The

Th e U.S. With ou t Trad e Wheat (tons)

actual choice will depend on the preferences of society. (In

Suppose the U.S. uses half its labor 5,000

to produce each of the two goods.

the following chapter – on supply and demand – we will 4,000

Then it will produce and consume 250 computers and

learn what determines how much of each good society 3,000 2500 tons of wheat. 2,000 produces.) 1,000 Computers 0 100 200 300 400 500

Important note for students:

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 11

Without trade, a country consumes what it produces.

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

Using this information to draw Japan’s PPF requires a A A C C T I V V E E L L E E A A R R N I N G G 1 D erive Jap an’s PPF

calculator (or the ability to do long division).

Use the following information to draw Japan’s PPF.

§ Japan has 30,000 hours of labor available for production, per month.

If your students have the “gutted handout” of these slides,

§ Producing one computer requires 125 hours of labor.

they can draw their PPF on the axes provided on the

§ Producing one ton of wheat requires 25 hours of labor. following slide.

Your graph should measure computers on the horizontal axis. 12

This activity should take only 3 minutes of class time. It’s

good practice & review for students, and helps break up the lecture.

Horizontal intercept: (30,000 labor-hours)/(125 hours per Jap an ’s PPF computer) = 240 computers. Wheat Japan has enough labor to (tons) produce 240 computers, 2,000 or 1200 tons of wheat,

Vertical intercept: (30,000 labor-hours)/(25 hours per ton of or any combination along the PPF. wheat) = 1200 tons of wheat. 1,000 Computers 0 100 200 300

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 13 Jap an With ou t Trad e Wheat (tons)

Suppose Japan uses half its labor to produce each good. 2,000

Then it will produce and consume 120 computers and 600 tons of wheat. 1,000 Computers 0 100 200 300

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 14

Con sum ption With and Withou t Trade § Without trade,

§ U.S. consumers get 250 computers and 2500 tons wheat.

§ Japanese consumers get 120 computers and 600 tons wheat.

§ We will compare consumption without trade to consumption with trade.

§ First, we need to see how much of each good is

produced and traded by the two countries.

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 15

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

Give your students a few minutes to solve these problems A A C C T I V V E E L L E E A A R R N I N G G 2

Prod uction u nd er trad e

before showing the answers on the next slides. This will

1. Suppose the U.S. produces 3400 tons of wheat.

How many computers would the U.S. be able to

break up the lecture, get the students involved, and give them

produce with its remaining labor? Draw the

point representing this combination of

practice with “word problems.”

computers and wheat on the U.S. PPF.

2. Suppose Japan produces 240 computers.

How many tons of wheat would Japan be able

It is not necessary that all students finish both problems

to produce with its remaining labor? Draw this point on Japan’s PPF.

before moving on. It’s fine if most finish the first, and a few 16

finish the second. However, the second problem is easy for most students.

Note that most students will need a calculator to solve the first problem.

Point out to students that the red dot represents the

U.S. Prod u ctio n With Trad e Wheat (tons)

combination (160 computers, 3400 tons of wheat). We will 5,000 Producing 3400 tons of wheat requires 34,000 labor hours.

assume that this is the combination the U.S. produces in the 4,000 The remaining 16,000

scenario in which the U.S. trades. 3,000 labor hours are used to produce 160 computers. 2,000 1,000 Computers 0 100 200 300 400 500

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 17

The red dot represents the combination (240 computers, 0

Jap an ’s Prod u ction With Trad e

tons wheat). We will assume this is the combination that Wheat Producing 240 computers (tons)

requires all of Japan’s 30,000 Japan produces. labor hours. 2,000 So, Japan would produce 0 tons of wheat.

Point out that, just because Japan is not producing any wheat 1,000

does not mean that Japan’s consumers must all go on the Computers 0

Atkins diet (which shuns bread and other foods made from 100 200 300

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 18

wheat). When trade is allowed, Japan can trade some of its

computers for wheat produced in another country.

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

These terms are so basic that many instructors skip this slide.

Basic In tern ation al Trad e Term s § Exports:

goods produced domestically and sold abroad

To export means to sell domestically produced

There’s a subtle point that you might want to mention (if goods abroad.

you’re anal like me), or that your students might ask about § Imports:

goods produced abroad and sold domestically

(especially if tourism is an important part of your local

To import means to purchase goods produced in other countries. economy).

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 19

Someone from Germany or South Korea visits Las Vegas

and spends $200 on a pair of tickets to a show. How should

we classify this and other expenditures by foreign tourists on

lodging and entertainment while they are vacationing here?

Answer: we count it in U.S. exports. It doesn’t matter that

the service was consumed here. What matters is that it was

produced here but sold to a foreign buyer.

Hence, a more precise definition of exports would be goods

and serviced produced here and purchased by foreign buyers.

This stricter definition of exports doesn’t care whether the

good or service was consumed in the buyer’s home country or in the exporting country.

Similarly, a stricter and more precise definition of imports

would include purchases by domestic residents of goods and

services produced abroad – including entertainment and

lodging services that tourists from the U.S. consume in the foreign countries they visit.

Some students need help figuring out that consumption of a A A C C T I V V E E L L E E A A R R N I N G G 3

Consu m p tion u nd er trade

good is the difference between the amount produced and the

Suppose the U.S. exports 700 tons of wheat to

Japan, and imports 110 computers from Japan. amount exported.

(So, Japan imports 700 tons wheat and exports 110 computers.)

§ How much of each good is consumed in the

U.S.? Plot this combination on the U.S. PPF.

§ How much of each good is consumed in Japan?

Plot this combination on Japan’s PPF. 20

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

U.S. Con su m p tion With Trad e

The red point again represents production. Wheat (tons) computers wheat 5,000 produced 160 3400 + imported 110 0

Trade un-tethers consumption from production. The light 4,000 – exported 0 700 = amount

blue point represents consumption. Notice that the 3,000 270 2700 consumed 2,000

consumption point is above the PPF. Without trade, it would 1,000

not be possible to consume this combination of the two Computers 0 100 200 300 400 500 goods!

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 21

In a sense, international trade is like technological progress:

it allows society to produce quantities of goods that would otherwise not be possible.

Jap an ’s Con su m p tion With Trad e

Again, the light blue point representing consumption is

above the PPF. Without trade, it would not be possible to computers wheat Wheat produced 240 0 (tons)

consume this combination of the goods. + imported 0 700 2,000 – exported 110 0 = amount 130 700 consumed 1,000 Computers 0 100 200 300

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 22

These tables summarize the gains from trade for both

Trad e Makes Both Cou ntries Better O ff U.S. countries.

consumption consumption gains from without trade with trade trade computers 250 270 20 wheat 2,500 2,700 200 Japan

consumption consumption gains from without trade with trade trade computers 120 130 10 wheat 600 700 100

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 23

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

The last bullet point states that gains from trade will arise if

Wh ere D o Th ese G ain s Com e From ?

§ Absolute advantage: the ability to produce a

each country has an absolute advantage in something. We

good using fewer inputs than another producer

will see next, though, that absolute advantage is not required

§ The U.S. has an absolute advantage in wheat:

producing a ton of wheat uses 10 labor hours

for both countries to gain from trade. in the U.S. vs. 25 in Japan.

§ If each country has an absolute advantage

in one good and specializes in that good,

then both countries can gain from trade.

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 24

Wh ere D o Th ese G ain s Com e From ?

§ Which country has an absolute advantage in computers?

§ Producing one computer requires 125 labor hours in Japan, but only 100 in the U.S.

§ The U.S. has an absolute advantage in both goods!

So why does Japan specialize in computers?

Why do both countries gain from trade?

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 25

Tw o M easu res of th e Cost of a G ood

§ Two countries can gain from trade when each

specializes in the good it produces at lowest cost.

§ Absolute advantage measures the cost of a good

in terms of the inputs required to produce it. § Recall:

Another measure of cost is opportunity cost.

§ In our example, the opportunity cost of a

computer is the amount of wheat that could be

produced using the labor needed to produce one computer.

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 26

O p p ortu n ity Cost an d

Com p arative Ad van tage

§ Comparative advantage: the ability to produce

a good at a lower opportunity cost than another producer

§ Which country has the comparative advantage in computers?

§ To answer this, must determine the opp. cost of a computer in each country.

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 27

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

O p p ortu n ity Cost an d

Com p arative Ad van tage

§ The opp. cost of a computer is

§ 10 tons of wheat in the U.S., because producing

one computer requires 100 labor hours,

which instead could produce 10 tons of wheat.

§ 5 tons of wheat in Japan, because producing

one computer requires 125 labor hours,

which instead could produce 5 tons of wheat.

§ So, Japan has a comparative advantage in

computers. Lesson: Absolute advantage is not

necessary for comparative advantage!

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 28

Com p arative Ad van tage an d Trad e

§ Gains from trade arise from comparative

advantage (differences in opportunity costs).

§ When each country specializes in the good(s)

in which it has a comparative advantage,

total production in all countries is higher,

the world’s “economic pie” is bigger,

and all countries can gain from trade.

§ The same applies to individual producers

(like the farmer and the rancher) specializing

in different goods and trading with each other.

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 29

Allow a few minutes for students to work on this problem. A A C C T I V V E E L L E E A A R R N I N G G 4

Ab solu te & com parative ad van tage

Ask for volunteers to share their answers.

Argentina and Brazil each have 10,000 hours of labor per month. In Argentina,

§ producing one pound coffee requires 2 hours

Variation: Before asking for volunteers, instruct students to

§ producing one bottle wine requires 4 hours In Brazil,

compare their answers with their neighbors. Not everyone

§ producing one pound coffee requires 1 hour

§ producing one bottle wine requires 5 hours

will volunteer to explain their answer to the class, but

Which country has an absolute advantage in the

production of coffee? W hich country has a

everyone will at least get to explain his or her answer to a

comparative advantage in the production of wine? 30 classmate. A A C C T I V V E E L L E E A A R R N I N G G 4 An sw ers

Brazil has an absolute advantage in coffee:

§ Producing a pound of coffee requires only one

labor-hour in Brazil, but two in Argentina.

Argentina has a comparative advantage in wine:

§ Argentina’s opp. cost of wine is two pounds of

coffee, because the four labor-hours required

to produce a bottle of wine could instead produce two pounds of coffee.

§ Brazil’s opp. cost of wine is five pounds of coffee. 31

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

Unan sw ered Q u estion s….

The 5th edition adds a brief explanation of the range of prices

§ We made a lot of assumptions about the quantities

that will permit gains from trade, in the context of the

of each good that each country produces, trades,

and consumes, and the price at which the farmer-rancher example.

countries trade wheat for computers.

§ In the real world, these quantities and prices would

be determined by the preferences of consumers

and the technology and resources in both

The second bullet point mentions technology and resources. countries.

§ We will begin to study this in the next chapter.

In our example, the technology is how many labor-hours are

§ For now, though, our goal was merely to

required to produce each good. The resources are simply the

see how trade can make everyone better off.

INTERDEPENDENCE AND THE GAINS FROM TRADE 32

quantity of labor-hours available in each country.

In the following chapter (on supply & demand), students will

begin their study of how prices and quantities are determined. CHAPTER SUMM ARY

§ Interdependence and trade allow everyone to enjoy

a greater quantity and variety of goods & services.

§ Comparative advantage means being able to

produce a good at a lower opportunity cost.

Absolute advantage means being able to produce a good with fewer inputs.

§ When people – or countries – specialize in the

goods in which they have a comparative advantage,

the economic “pie” grows and trade can make everyone better off. 33

Downloaded by Nga T??ng (ngahuong55@gmail.com) lOMoARcPSD|36041561

PowerPoint Lecture Notes for Chapter 4:

The Market Forces of Supply and Demand

Principles of Economics 5th edition, by N. Gregory Mankiw

Premium PowerPoint Slides by Ron Cronovich

This is perhaps the most important chapter in the textbook. C H A P T E R 4

It’s worth mentioning to your students that investing extra

Th e M ark et Forces of

time to master this chapter will make it easier for them to

Su p p ly an d D em an d