Preview text:

Business Horizons (2014) 57, 595—605

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect www.elsevier.com/locate/bushor Supply chain analytics Gilvan C. Souza

Kelley School of Business, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405, U.S.A. KEYWORDS Abstract

In this article, I describe the application of advanced analytics techniques Supply chain

to supply chain management. The applications are categorized in terms of descrip- management;

tive, predictive, and prescriptive analytics and along the supply chain operations Analytics;

reference (SCOR) model domains plan, source, make, deliver, and return. Descriptive Optimization;

analytics applications center on the use of data from global positioning systems Forecasting

(GPSs), radio frequency identification (RFID) chips, and data-visualization tools to

provide managers with real-time information regarding location and quantities of

goods in the supply chain. Predictive analytics centers on demand forecasting at

strategic, tactical, and operational levels, all of which drive the planning process in

supply chains in terms of network design, capacity planning, production planning, and

inventory management. Finally, prescriptive analytics focuses on the use of mathe-

matical optimization and simulation techniques to provide decision-support tools

built upon descriptive and predictive analytics models.

# 2014 Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Why analytics in supply chain

analytical approaches to make decisions that better management? match supply and demand.

Well-planned and implemented decisions con-

The supply chain for a product is the network of

tribute directly to the bottom line by lowering

firms and facilities involved in the transformation

sourcing, transportation, storage, stockout, and

process from raw materials to a product and in

disposal costs. As a result, analytics has historically

the distribution of that product to customers. In

played a significant role in supply chain manage-

a supply chain, there are physical, financial, and

ment, starting with military operations during and

informational flows among different firms. Supply

after World War II–—particularly with the develop-

chain analytics focuses on the use of information

ment of the simplex method for solving linear pro-

and analytical tools to make better decisions regard-

gramming by George Dantzig in the 1940s. Supply

ing material flows in the supply chain. Put

chain analytics became more ingrained in decision

differently, supply chain analytics focuses on

making with the advent of enterprise resource plan-

ning (ERP) systems in the 1990s and more recently

with ‘big data’ applications, particularly in descrip-

tive and predictive analytics, as I describe with

E-mail address: gsouza@indiana.edu some examples in this article.

0007-6813/$ — see front matter # 2014 Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2014.06.004 596 G.C. Souza

The Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR)

pallets (even at the product level), and transactions

model developed by the Supply Chain Council

involving barcodes. Information is derived from the

(www.supply-chain.org) provides a good framework

vast amounts of data collected from these sources

for classifying the analytics applications in supply

through data visualization, often with the help of

chain management. The SCOR model outlines four

geospatial mapping systems. RFID is a significant

domains of supply chain activities: source, make,

improvement over barcodes because it does not

deliver, and return. A fifth domain of the SCOR

require direct line of sight. Accurate inventory re-

model–—plan–—is behind all four activity domains.

cords are critical in supply chains as they trigger

Furthermore, a key input of the supply chain plan-

regular replenishment orders and emergency orders

ning process is demand forecasting at all time

when inventory levels are too low. Although RFID

frames: long, mid, and short term with planning

technology helps in significantly reducing the fre-

horizons of years, months, and days, respectively.

quency of manual inventory reviews, such reviews

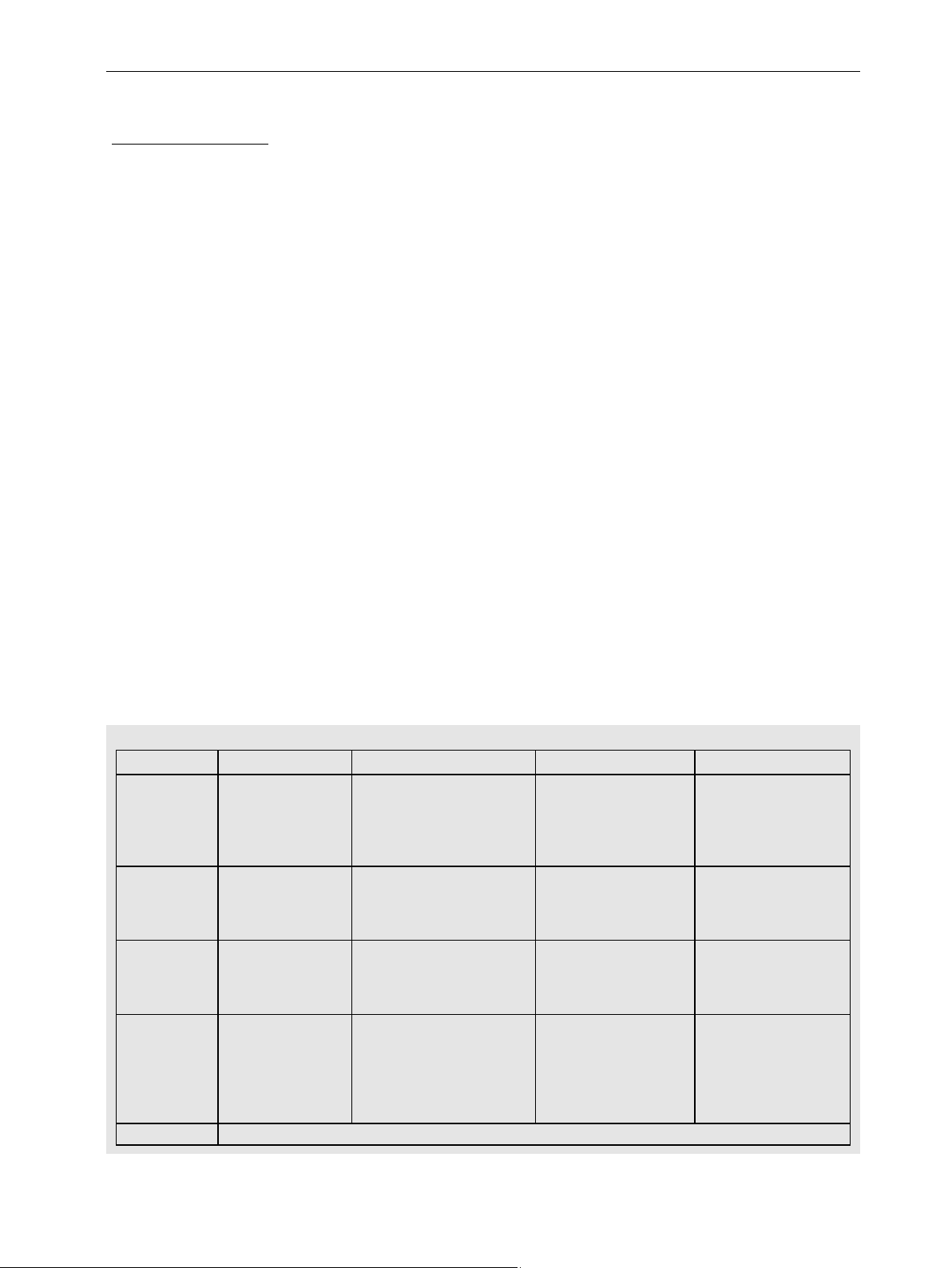

Table 1 illustrates different decisions in each of the

are still needed because of data inaccuracy due to,

four SCOR domains that can be aided by analytics.

for example, inventory deterioration or damage or

These decisions are further classified into strategic, even tag-reading errors.

tactical, and operational according to their time

Predictive analytics in supply chains derives de- frame.

mand forecasts from past data and answers the

Analytics techniques can be categorized into

question of what will be happening.

three types: descriptive, predictive, and prescrip-

Prescriptive analytics derives decision recom-

tive. Descriptive analytics derives information from

mendations based on descriptive and predictive

significant amounts of data and answers the ques-

analytics models and mathematical optimization

tion of what is happening. Real-time information

models. It answers the question of what should be

about the location and quantities of goods in the

happening. Arguably, the bulk of academic re-

supply chain provides managers with tools to make

search, software, and practitioner activity in supply

adjustments to delivery schedules, place replenish-

chain analytics focuses on prescriptive analytics.

ment orders, place emergency orders, change trans-

In Table 2, I provide a summary of analytics

portation modes, and so forth. Traditional data

techniques–—descriptive, predictive, and prescrip-

sources include global positioning system (GPS) data

tive–—used in supply chains in terms of the four SCOR

on the location of trucks and ships that contain

domains of source, make, deliver, and return. I

inventories, radio frequency identification (RFID)

elaborate on Table 1 and Table 2 in the next

data originating from passive tags embedded in sections. Table 1.

SCOR model and examples of decisions at the three levels SCOR Domain Source Make Deliver Return Activities Order and receive Schedule and Receive, schedule, Request, approve, and materials and manufacture, repair, pick, pack, and determine disposal of products remanufacture, or ship orders products and assets recycle materials and products Strategic Strategic Location of plants Location of Location of return (time frame: sourcing Product line mix distribution centers centers years) Supply chain at plants Fleet planning mapping Tactical

Tactical sourcing Product line Transportation and Reverse distribution (time frame: Supply chain rationalization distribution planning plan months) contracts Sales and Inventory policies operations planning at locations Operational Materials Workforce scheduling Vehicle routing Vehicle routing (for (time frame: requirement Manufacturing, order (for deliveries) returns collection) days) planning tracking, and scheduling and inventory replenishment orders Plan

Demand forecasting (long term, mid term, and short term) Supply chain analytics 597 Table 2.

Analytic techniques used in supply chain management Analytics Source Make Deliver Return Techniques Descriptive Supply chain mapping Supply chain visualization Predictive

Time series methods (e.g., moving average, exponential smoothing, autoregressive models)

Linear, non-linear, and logistic regression

Data-mining techniques (e.g., cluster analysis, market basket analysis) Prescriptive Analytic hierarchy process Mixed-integer linear Network flow

Game theory (e.g., auction design, programming (MILP) algorithms contract design) Non-linear programming MILP Stochastic dynamic programming

2. Plan: Demand forecasting using

are derived from time-based demands for the predictive analytics

SKUs that use those parts, so parts have dependent

demand. In contrast, SKUs have independent

Demand forecasting is a critical input to supply

demand. Demand forecasts for items subject to inde-

chain planning. Different time frames for demand

pendent demand require predictive analytics techni-

forecasting require different analytics techniques.

ques, whereas forecasts for dependent demand items

Long-term demand forecasting is used at the stra-

are obtained directly from the MRP system. Demand

tegic level and may use macro-economic data, de-

forecasts for independent demand items are also used

mographic trends, technological trends, and

to plan for inventory safety stocks at other locations,

competitive intelligence. For example, demand fac-

such as distribution centers and retailers.

tors for commercial aircraft at Boeing include ener-

Demand forecasting for independent demand

gy prices, discretionary spending, population

items is usually performed using time-series methods,

growth, and inflation, whereas demand factors for

for which the only predictor of demand is time. Time-

military aircraft include geo-political changes, con-

series methods include moving average, exponential

gressional spending, budgetary constraints, and

smoothing, and autoregressive models. For example,

government regulations (Safavi, 2005). Causal fore-

Winter’s exponential smoothing method incorporates

casting methods–—called such because they analyze

both trend and seasonality and can be used for both

the underlying factors that drive demand for a

short-term and mid-term forecasting. In an autore-

product–—are used at this level. Analytics causal

gressive model, demand forecast in one period is a

forecasting methods include linear, non-linear,

weighted sum of realized demands in the previous and logistic regression. periods.

To illustrate demand forecasting for tactical and

Mid-term forecasting can also benefit from

operational supply chain decisions, consider the

causal forecasting methods, especially in non-

production planning process for an original equip-

manufacturing industries or the manufacturing of

ment manufacturer (OEM) such as Whirlpool. At the

non-discrete items. For example, in order to fore-

product family level (e.g., refrigerators), the sales

cast monthly demand for truckload (TL) freight

and operations planning (S&OP) process uses aggre-

services, Fite, Taylor, Usher, English, and Roberts

gate demand forecasts in monthly time buckets to

(2002) considered 107 economic indexes as poten-

establish aggregate production rates, aggregate

tial predictors, including the purchasing manager’s

levels of inventories, and workforce levels. The

index, the Dow Jones stock index, the consumer

aggregate plan is revised on a rolling basis as new

goods production index, automotive dealer sales,

data is available. The S&OP plan, as well as more

U.S. exports, the producer commodities price index

refined demand forecasts at the stock-keeping unit

for construction materials and equipment, interest

(SKU) level, is used to derive the master production

rates, and gasoline production. They used stepwise

schedule (MPS), which details weekly production

regression to identify the most relevant indexes and

quantities at the SKU level for a typical planning

found parsimonious models for predicting TL de-

horizon of 8—12 weeks. The MPS and the bill of

mand for specific industries and regions. Their mod-

materials are then used to plan production and

el only predicts industry-wide demand for TL

sourcing at the part level through a materials re-

services (nationally or by region); the connection

quirement planning (MRP) system that is embedded

to demand forecasts at the firm level was made

in most ERP software. Time-based demands for parts

using historical market shares. 598 G.C. Souza

Data mining has also been used for demand fore-

Firms are very familiar with their first-tier sup-

casting in conjunction with traditional forecasting

pliers (i.e., those that directly supply them) and

techniques (Rey, Kordon, & Wells, 2012). Usually,

perhaps their second-tier suppliers (i.e., those that

the data-mining step precedes the use of causal

supply first-tier suppliers), but some of their lower-

forecasting techniques by finding appropriate de-

tier suppliers may be unknown. A recent example is

mand drivers (i.e., independent variables) for a

the November 2012 fire at the Bangladesh factory

product that can be used in regression analysis.

that killed more than 100 workers. An audit of the

For example, Dow Chemical uses a combination of

factory by Walmart in 2011 ruled it out as a supplier.

data mining and regression techniques to forecast

However, one of Walmart’s suppliers continued to

demand at the strategic and tactical levels (e.g.,

subcontract work to that factory (Tsikoudakis,

identifying demand trends), which is useful for its

2013). The threat of disruptions like natural disas-

pricing strategy and for configuring and designing its

ters, social and political unrest, and major strikes

supply chain to respond to these trends (Rey & Wells,

makes it imperative for firms to map their supply

2013). Data-mining methods usually involve cluster-

chains. For example, Cisco (2013) uses supply chain

ing techniques. So, if a retailer finds out, for exam-

mapping and enterprise social networking to iden-

ple, that demand for cereal is strongly related to

tify its vulnerabilities to supply chain disruptions as

milk sales, then the retailer may build a causal

well as to collaborate with its suppliers and part-

forecasting model that predicts cereal sales with

ners. The open source tool sourcemap.com, devel-

milk sales as one of the predicting variables. Market

oped at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

basket analysis is a specific data-mining technique

allows one to visualize and map a supply chain; the

that provides an analysis of purchasing patterns at

tool can also be used for purposes such as carbon

the individual transaction level, so a retailer can

footprint estimation. An example is shown in

analyze the frequency with which two product cat- Figure 1.

egories (e.g., DVDs and baby products) are pur-

chased together. Lift for a combination of items is

3.2. Source: Tactical decisions

equal to the actual number of times the combina-

tion occurs in a given number of transactions divided

In contrast to strategic sourcing, tactical sourcing

by the predicted number of times the combination refers to the process of achieving specific

occurs if items in the combination were indepen-

objectives–—such as determining costs for parts,

dent. Lift values above 1 indicate that items tend to

materials, or services–—through structured procure-

be purchased together. This kind of analysis can be

ment mechanisms like auctions. The central prob-

useful when building causal regression models for

lem in procurement auctions centers on mechanism

demand forecasting. It can also aid in promotion

design: How should one structure the rules of an

activities because the retailer can predict how much

auction so that bidders (i.e., suppliers) behave in a

sales of Product 1 would increase if there is a

manner that results in minimal procurement cost

promotion for Product 2 if the two products are

(and desired performance) for the buyer? Auctions often purchased together.

can be open (i.e., bidders can view and respond to

bids) or sealed and one shot or dynamic (which occur 3. Source

over several rounds of bidding). Government auc-

tions tend to be one-shot, sealed auctions, whereas

3.1. Source: Strategic decisions

open, dynamic auctions are common in industrial

procurement (Beil, 2010). Buyers must consider the

Strategic sourcing is the process of evaluating and

total procurement cost as bidders usually bid on

selecting key suppliers. There is limited use of

contract payment terms only (e.g., unit cost). Ad-

analytics for strategic sourcing in practice even

ditional logistics costs, if paid by the buyer, must be

though academics prescribe the use of sophisticated

taken into account in the bid price. The prescriptive

multi-criteria decision-making techniques such as

analytics used here is centered on game theory,

analytic hierarchic process (AHP). AHP decomposes

which is used to determine auction rules. Procure-

a complex problem (e.g., selecting a supplier among

ment auctions are widely used in practice.

a diverse set) into more easily comprehended sub-

A commonly used payment contract in sourcing is

problems that can be analyzed separately. In the

wholesale price, via which the buyer (i.e., retailer)

supplier-selection problem, these sub-problems

pays the seller (i.e., manufacturer) a fixed price per

might include distinct evaluations of factors like

unit. Under this contract, retailers are exposed to

cost, quality, delivery speed, delivery reliability,

demand risk: they bear the entire costs of over-

volume flexibility, product mix flexibility, and sus-

stocking and therefore have an incentive to stock

tainability. These evaluations are then weighed.

less than what is optimal for the supply chain as a Supply chain analytics 599 Figure 1.

Example of supply chain mapping using sourcemap.com

Source: free.sourcemap.com/view/6585/

whole. Recognizing this, academics have used a

problem can be illustrated when deciding where to

combination of game theory and statistics to pre-

build DCs that serve as intermediary stocking

scribe more sophisticated contracts that will im-

and shipping points between existing plants and

prove product availability in retailers. For example,

retailers. This problem is formulated as a mixed-

in a buy-back contract, retailers can return unsold

integer linear program (MILP). Data requirements

units to the manufacturer and receive a partial

include yearly aggregate demands for the product

refund. Although such contracts can improve supply

family at each retailer, plant capacities, unit ship-

chain performance, the wholesale price contract is

ping costs between each pair of locations, and the

still widely used, perhaps due to its simplicity.

annual fixed cost of operating a DC at each potential

location. Decision variables include the quantity to

ship between locations and binary variables that 4. Make

indicate if each DC should be open or closed. The

objective function minimizes total shipping and 4.1. Make: Strategic decisions

fixed DC costs. Constraints ensure that demand is

met at all locations, that companies only ship prod-

Network design determines the optimal location and

ucts from a DC if it is open, and that all plant

capacity of plants, distribution centers (DCs), and

capacities are respected. The solution provides

retailers. The simplest form of the network design

the location (i.e., where to open the DCs) as well 600 G.C. Souza

as the allocation of plants to the DCs, the allocation

meets fluctuating demand by producing at a constant

of DCs to retailers, and the capacity of each DC.

rate and holding inventory to meet the peak demand.

Variations of this simple MILP formulation include

Alternatively, the firm can use a chase strategy,

multiple products, transportation capacities between

adjusting workforce levels monthly to meet fluctuat-

locations, multiple transportation modes between

ing demand. Firms frequently use a hybrid strategy

locations, a multi-year planning horizon, multiple between chase and level.

echelons (i.e., tiers in the supply chain), demand

Product proliferation and mass customization have

uncertainty, supply uncertainty, and reverse flows

been widely documented (e.g., Rungtusanatham &

(e.g., the collection of used products for recycling

Salvador, 2008). For product proliferation and mass

and remanufacturing). When the problem incorpo-

customization, the plant must adapt from a mass

rates multiple products, the analysis also provides the

production environment–—designed for economies

product mix at each plant. When many of the varia-

of scale, with fewer products produced in dedicated

tions above are incorporated and the problem is large

lines and setup costs spread over long production

(e.g., thousands of retailers and potential DC and

runs–—to a flexible production environment. This

plant locations), the problem may become too diffi-

adaptation is made possible with the aid of flexible

cult to solve to optimality using off-the-shelf optimi-

manufacturing technology or changes in the product

zation software. Therefore, many researchers have

and process design that support a postponement

proposed well-performing heuristics, such as genetic

strategy (Lee, 1996). In a postponement strategy, algorithms, that ensure good–—and sometimes

the step in the manufacturing process in which prod-

optimal–—solutions. Genetic algorithms use a divide

uct differentiation occurs–—from gray boxes to

and conquer (the feasible region) approach to finding

SKUs–—is located closer to the customer, which allows

a good solution to the MILP as opposed to optimal

the firm to carry inventory of gray boxes instead of

branch and bound algorithms, which are combinato-

SKUs, and thus lessens differentiation time. Post- rial in nature.

ponement mitigates the negative impacts of in-

Some of the data necessary to perform such

creased product proliferation, such as increased

analysis requires a preliminary level of analysis so

forecasting uncertainty at the SKU level; increased

it can be extracted, cleaned, and aggregated from

inventory costs; and complexity costs, such as re-

ERP systems. Network design, however, is only per-

search and development, testing, tooling, returns,

formed infrequently for each firm, including during

and obsolescence. Postponement requires changes in

mergers and acquisitions. As a result, it is not part of

product and process design, and it may not be feasi-

standard ERP software. Specialized software makes

ble for products like automobiles, for which strict

it easy to input this data, specify the constraints,

quality guidelines in final assembly preclude signifi-

perform the optimization, and visualize the results,

cant customization at dealers. As an alternative, especially for large problems.

firms may increase supply chain performance through

product rationalization using analytics, as shown in 4.2. Make: Tactical decisions Table 3.

We have previously described the S&OP process,

4.3. Make: Operational decisions

which is used for planning aggregate workforce

and inventory levels on a medium planning horizon

Manufacturing scheduling is the last step in the

based on demand forecasts, underlying costs, and

planning process after MRP plans are released. An

actual sales. Academics have proposed MILP models

MRP plan specifies quantities and due dates for all

for this process. For each month in the planning

parts. Scheduling then sequences the jobs (i.e.,

horizon, decision variables include the amount to

parts) by the different resources necessary for

produce for each product family using regular time,

manufacturing the part in order to meet the due

overtime, and subcontracting and the number of

dates. In general, there are n jobs to be scheduled in

workers to be hired and laid off. The objective

m different resources, and the processing time, due

function minimizes total cost, which comprises total

date, and weight (i.e., priority) of each job in each

production cost (i.e., regular time, overtime, and

resource are known. This problem takes different

subcontracting), total inventory cost, total wages,

forms depending on the decision maker’s objective,

total hiring cost, and total layoff cost. Constraints

the number of resources, and how the jobs are

may come from, among others, inventory and work-

processed with the resources. An objective function force balancing, regular production capacity,

minimizes the maximum completion time, or the

and overtime production. Many practitioners use

maximum lateness, across all jobs. There can be

rules-based heuristics. For example, one heuristic

precedence relationships, setup times, or even

is a level production strategy, via which the firm

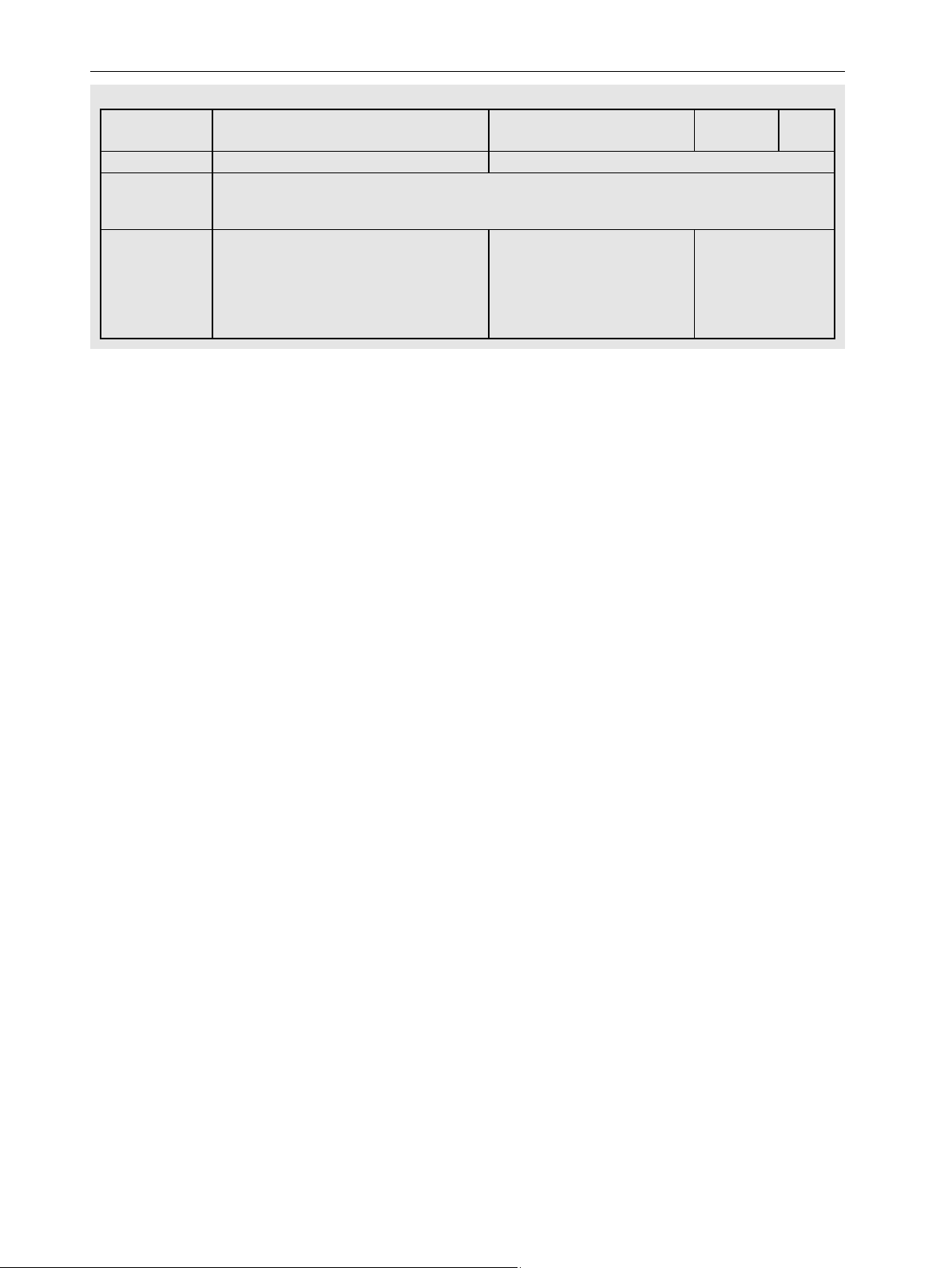

sequence-dependent setup times (i.e., when the Supply chain analytics 601 Table 3.

Product rationalization at Hewlett-Packard

Hewlett-Packard (HP) has developed optimization tools for product rationalization (Ward et al., 2010). One tool

requires proposed new product line extensions to meet minimum complexity return-on-investment (ROI)

thresholds. Complexity ROI is defined as the incremental margin minus variable complexity costs, divided by fixed

complexity costs. Variable complexity costs are largely driven by forecasting uncertainty and resulting increased

inventory costs, whereas fixed complexity costs are driven by criteria such as research and development, tooling,

and manufacturing setup costs. With another tool, HP uses a maximum flow algorithm on an existing product line to

perform product rationalization. The tool acknowledges that in firms with configurable product lines, some

products, such as power supplies, may generate little revenue on their own but are critical components for high-

revenue orders and for overall order fulfillment. Order coverage is defined as the percentage of a given set of past

orders that can be met from the rationalized product portfolio. Similarly, revenue coverage is the smallest portfolio

of products that covers a given percentage of historical order revenue. This optimization tool revealed how HP can

offer only 20% of previously offered features in laptops and reach 80% revenue coverage. After implementing the

recommendations, HP realized significantly reduced inventory costs and increased gross margins.

setup time for a job at a resource depends on the

The decision maker needs demand forecasts for

previous job there, such as in processing industries

each time block (e.g., 12 p.m.—1 p.m. on Monday),

like the chemical industry). Scheduling problems

which can be obtained through predictive forecast-

can be formulated as MILPs, and the combinatorial

ing models. This problem can be formulated as an

nature of these problems makes them very hard to

MILP in which decision variables include the number

solve to optimality for large problems. As a result,

of employees assigned to each tour and the number

significant effort has been devoted to finding good

of employees necessary to meet demands within

solutions through heuristics because other compli-

each time block. The objective function minimizes

cations arise in practice, such as adding new jobs to

total labor costs. Complications, such as workers’

the existing pool of processing jobs as well as chang-

preferences, multiple locations, task assignments,

ing priorities and preferences. In terms of software,

and so forth, increase the size of the MILP model to

some ERP systems have scheduling modules (e.g.,

such an extent that heuristics are almost certainly

the Applied Planning and Optimization module in

needed. Some ERP vendors have workforce sched-

SAP) that use genetic algorithms to provide good

uling modules for specific applications like retail and

solutions to MILPs found in determinist scheduling.

hospitality. There are also vendors for industry-spe-

These algorithms can provide good solutions to fairly

cific software, such as call centers and health care

large problems, such as 1 million jobs over 1,000

providers. Many airlines, which are heavy analytics

resources (Pinedo, 2008). There are a few compa-

users, have developed their own scheduling algo-

nies such as Taylor (www.taylor.com) that specialize rithms.

in providing scheduling software with many function-

alities not present in ERP systems. Although the

discussion above has centered on manufacturing 5. Deliver and return

scheduling, some of the same algorithms can be used

in other scheduling problems like assigning gates at

5.1. Deliver and return: Strategic

an airport or trucks at a cross-docking location. decisions

Workforce scheduling can be challenging for ser-

vice industries, such as call centers, hospitals, and

In Section 4, I presented the network design problem

airlines, in which there is seasonal demand, not only

of planning the location of DCs and return centers.

for time of the year (common in manufacturing), but

Another strategic decision here is fleet planning,

also for day of the week and hour of the day. A

which can be described as the dynamic acquisition

common way of modeling these problems is

and divestiture of delivery vehicles to meet the

by defining tours. A tour is a combination of time

demand for deliveries or returns collection. This

blocks within a day and within days of the week that

problem is formulated as an MILP, or dynamic pro-

add up to the necessary work hours per employee. gramming, as in Table 4.

An example of a tour would be Monday, 8 a.m.—1

p.m.; Tuesday, 1 p.m.—6 p.m.; Thursday, 8 a.m.—6

5.2. Deliver and return: Tactical decisions

p.m.; and Friday, 8 a.m.—6 p.m. Tours should be

feasible; for example, it is not very convenient for

In transportation and distribution planning, the firm

most people to work from 8 a.m.—10 a.m. and

distributes a set of products from source nodes (i.e.,

then from 3 p.m.—5:00 p.m. on the same day.

supply points such as factories) to sink nodes 602 G.C. Souza Table 4.

Fleet planning for Coca-Cola Enterprises

Coca-Cola Enterprises (CCE) has started replacing some of its fleet of diesel delivery trucks with diesel-electric

hybrid vehicle (HEV) trucks. How the company chooses to invest those dollars depends on volatile fuel costs, usage-

based deterioration, and seasonal demand. Wang, Ferguson, Hu, and Souza (2013) have provided a prescriptive

analytics model that takes into consideration CCE’s historical maintenance costs, purchasing costs for both diesel

and HEV trucks, CCE demand data, and historical diesel price data to calibrate a stochastic model that simulates

diesel prices dynamically. Using dynamic programming, the optimal policy is obtained, at each period of a planning

horizon and for each realization of diesel prices, that determines how many trucks of each type (diesel and HEV)

CCE should acquire and/or divest. Wang et al. found that at the current outlook of diesel prices, CCE should include

both HEV (54%) and diesel trucks (46%) in its capacity portfolio. In this regard, CCE could use HEV trucks to meet its

average baseline demand and then deploy diesel trucks to supplement the delivery fleet during peak demand seasons.

(i.e., demand points such as retail locations)

replenishment lead times are variable. Data re-

through intermediary storage nodes (e.g., DCs). This

quirements include historic demand and forecasting

problem is solved using a multi-commodity network

data, replenishment lead times, the desired service

flow model, which is a linear programming formula-

level (i.e., a desired fill rate or stock-out probabili-

tion with a special structure. In the network formu-

ty), holding cost, and the fixed cost of placing a

lation, there can be multiple arcs between each pair

replenishment order. The inventory policy parame-

of nodes. Each arc represents a shipping mode with a

ters–—reorder point and order quantity–—can be

given capacity, such as rail, truckload (TL), less than

computed using exact algorithms or approximate

truckload (LTL), and air. The amount to ship in each

formulas, which are embedded in most supply chain

arc in the network for each commodity and time

software, including in some ERP systems modules.

period is considered. Constraints include capacity at

More often, the supply chain has multiple stocking

each arc, time period, and node, as well as flow-

points for the same product. For example, a product

balancing at each node. Data requirements include

can be stocked at a DC and multiple different retailers

shipping costs in each arc, forecasts of supply avail-

in different regions. Although one can set inventory

able at each source node (provided by the S&OP

policies at each location that use only local demand

plan), point forecasts for demand at each sink node

and replenishment lead-time information, this ‘local

(from predictive analytics models), and arc capaci-

optimization’ approach is not optimal for the supply

ties. Economies of scale in shipping can also be

chain. Due to risk pooling, it may be optimal to have

incorporated. Problems of realistic size have thou-

some level of inventory at the DC so that higher-than-

sands of nodes, resulting in millions of decision

normal demand in one retailer can be balanced against

variables. However, such problems can be solved

lower-than-normal demand at another retailer. This

efficiently with numerical algorithms based on the

situation calls for an integrated inventory policy for

network simplex method, which is embedded in

the entire supply chain; the theory that prescribes

supply chain optimization software. Despite exten-

these inventory policies is called multi-echelon inven-

sive planning, disruptions (e.g., traffic, weather)

tory theory. The complication in multi-echelon inven-

and demand uncertainty often require plan modifi-

tory theory arises when the DC does not have sufficient

cation, and descriptive analytics tools can be quite

inventory to meet all incoming orders from retailers at

valuable. For example, the Control Tower descrip-

a given period. In that case, the optimal inventory-

tive analytics system allows Procter & Gamble (P&G)

rationing policy is complex, and even more so if there

to see all the transportation occurring in its near

are more than two echelons. There are, however,

supply chain (i.e., inbound, outbound, raw materi-

several well-performing heuristics that are computa-

als, and finished product). With this technology,

tionally simple, such as the guaranteed service level

P&G has reduced deadhead movement (i.e., when

heuristic (Graves & Willems, 2000), which has been

trucks travel empty or not optimally loaded) by 15%

implemented in software like Optiant. An example of

and thus has reduced costs (McDonald, 2011).

successful application is provided in Table 5. Another important decision is determining

supply levels at nodes in a distribution network–—

5.3. Deliver and return: Operational

that is, setting inventory policies. The science for decisions

setting inventory policies (i.e., reorder point and

order-up-to level or order quantity) for a product

The vehicle routing problem (VRP) optimizes the

at a single location, such as a DC, is mature, even

sequence of nodes to be visited in a route, for

when demand is uncertain and non-stationary and

example, for a parcel delivery truck, for a returns Supply chain analytics 603 Table 5.

Multi-echelon inventory management at P&G

Before 2000, P&G used only single-location inventory models, which optimize inventory levels locally given that

location’s own replenishment lead time. However, starting in 2005—2006, P&G started implementing multi-echelon

inventory models based on the guaranteed service level heuristic in its more complex supply networks. At a

particular stage in the supply chain, inventory is set to meet a desired service level based on a guaranteed delivery

time to the customer (S), its own replenishment lead time when ordering from a preceding stage (SI), and its

processing time (T). Essentially, the method sets safety stock levels as if it was a single location with a

replenishment lead time of SI + T - S. Note that SI for a stage is equal to S for a preceding stage. Through dynamic

programming, the method finds the optimal S for each stage to minimize holding costs across the supply chain. The

multi-echelon supply chain approach to inventory management was implemented at 30% of P&G’s locations using

Optiant software and consequently saved the company $1.5 billion in inventory costs in 2009 compared to the

single-location models previously in place (Farasyn et al., 2011). Table 6.

Vehicle routing at Waste Management, Inc.

Waste Management, Inc. (WM) is a leading provider of solid waste collection and disposal services. It has a fleet of

more than 26,000 vehicles running nearly 20,000 routes. In 2003, the company implemented the WasteRoute

vehicle-routing software, which included GIS capabilities and navigational capabilities, and integrated it with a

relational database containing customer information. An origin-destination matrix was then developed that

considered constraints such as time and distance traveled between any two points, speed limits, and one-way

streets. By implementing the combined prescriptive and descriptive analytics software, the firm saved $44 million in 2004. Source: www.informs.org

collection truck, or for both. The optimal sequence

to match their fixed capacity through prices and

takes into account the distances between each pair

other mechanisms that will be described next. This

of nodes; expected traffic volume; left turns; and

is known as revenue management.

other constraints placed on the routes, such as

Revenue management started in the airline in-

delivery and pickup time windows. Known as the

dustry after deregulation, with the problem of allo-

travelling salesman problem (TSP), the classical VRP

cating seats in a flight to fare classes. Allocation

problem only takes into account the distances be-

policies are nested. For instance, suppose there are

tween each pair of nodes: In what sequence should

two fare classes: $150 (Fare Class 1) and $90 (Fare

nodes be visited, ending at the same starting point?

Class 2). The decision maker sets a booking limit for

This problem can be formulated as an MILP. The TSP

Fare Class 2 and then determines the booking limit

problem is combinatorial in nature, and is hard

of Fare Class 1 based on the capacity of the flight.

to solve beyond a few thousand nodes (Funke &

Data requirements for the computation of booking

Gruenert, 2005). Among others, complications such

limits include demand forecasts for the different

as multiple vehicles, vehicle capacities, tour-length

classes (as a probability distribution) at different

restrictions, and delivery and pickup time windows

times before departure, cancellation probabilities,

result in an MILP that is very difficult to solve, thus

up-selling probabilities (i.e., the probability that a

requiring heuristic approaches. In addition to heu-

customer will buy a higher fare if the lower fare is

ristic approaches, vehicle-routing software incorpo-

unavailable), and fare values. The problem is sig-

rates descriptive analytics, as shown in Table 6.

nificantly more complex in a network. For example,

one passenger goes from Indianapolis (IND) to

New York (JFK), whereas another passenger goes 6. Modulating demand to match

from IND to Rochester (ROC) via JFK. In this case, capacity: Revenue management

heuristic approaches, such as bid-price controls, are

used. The bid price for a resource (e.g., a seat in a

The SCOR model implicitly assumes that managers

specific flight IND-JFK) is the marginal cost to the

plan their operations–—source, make, deliver, and

network of consuming one unit of that resource.

return–—based on demand forecasts. Therefore, the

When a customer demand arises (e.g., IND-ROC via

SCOR model plans capacity to match a given de-

JFK), then the demand’s revenue is compared

mand. Industries with perishable capacities, like

against the sum of bid prices for all resources asso-

airlines, hospitality, and transportation, must take

ciated with the demand request (i.e., bid prices for

a reverse approach, so firms modulate their demand

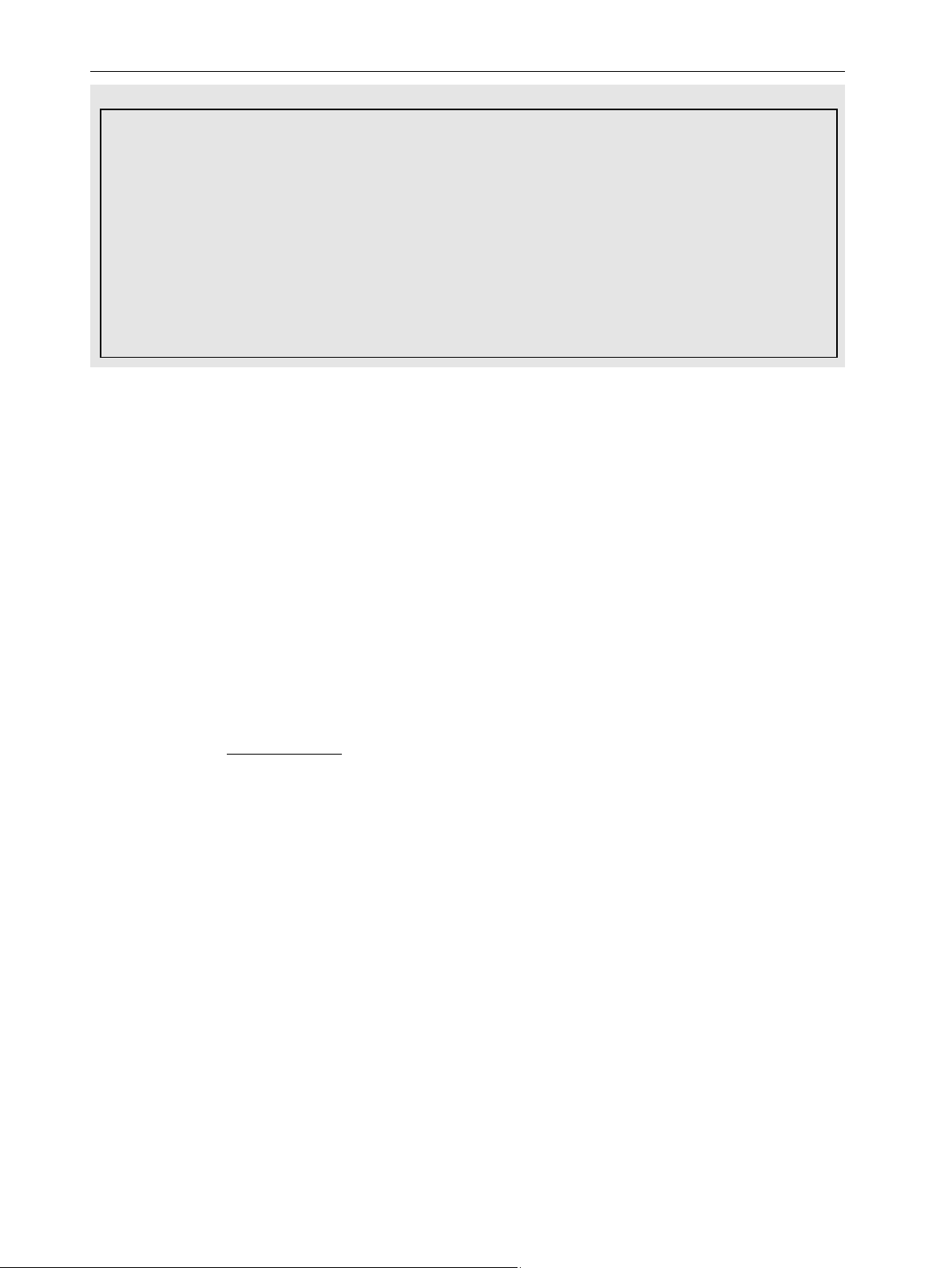

a seat IND-JFK and for a seat JFK-ROC). The demand 604 G.C. Souza Table 7. Additional information on analytics

research, particularly linear programming and

techniques for supply chain management

optimization. For example, inventory theory is more

than 50 years old, and there were significant

General overview: Snyder and Shen (2011)

contributions to production planning in the 1980s. Network design: Funaki (2009)

Therefore, analytics in supply chain management is Auctions: Krishna (2002)

not new. More recent applications include the inte-

Sales and operations planning: Jacobs, Berry, Whybark, and Vollmann (2011)

gration of price analytics and supply chain manage-

Transportation and distribution planning: Ahuja,

ment in the field of revenue management, for which Magnanti, and Orlin (1993)

the problem revolves around managing demand in

Inventory management: Zipkin (2000)

an environment with fixed and perishable capacity.

Dynamic pricing and revenue management: Talluri

Revenue management research and practice (par- and Van Ryzin (2004)

ticularly in manufacturing) is relatively new because

Manufacturing scheduling: Pinedo (2008)

many demand models can only be calibrated with

Workforce scheduling: Campbell (2009)

significant amounts of data, which just recently

became available from modern ERP systems and web technologies.

With big data, new opportunities arise. I have

is accepted if the revenue is higher than the sum of

heard consultants praising the potential of harness-

bid prices. Bid prices can be approximated through

ing social networks for supply chain management, linear programming.

for example, by detecting local trends in demand to

In capacity allocation, fare prices are given as

adjust inventories and prices. There is indeed po-

they are determined by market forces. Another way

tential there, although many firms still struggle to

to manage uncertain demand for fixed capacity–—be

match basic supply and demand in a world with

it flight seats, hotel rooms, rental cars, or inventory

increased product proliferation, competition, and

in a retail environment–—is through pricing. As ar-

globalization (i.e., longer lead times). Among other

gued by Talluri and Van Ryzin (2004, p. 175), ‘‘the

benefits, big data has the potential to improve

distinction between quantity and price controls is

demand forecasting methods, detect supply chain

not always sharp (for instance, closing the availabil-

disruptions, and improve communications in supply

ity of a discount class can be considered equivalent

chains that are often global (see Table 7).

to raising the product’s price to that of the next

highest class).’’ However, using price as a direct

mechanism to match demand with capacity is an References

important enough practical problem to merit special

treatment. Dynamic pricing has gained significant

Ahuja, R., Magnanti, T., & Orlin, J. (1993). Network flows:

traction lately, particularly in retailing (i.e., mark-

Theory, algorithms, and applications. Upper Saddle River,

down pricing), e-commerce, and even manufactur- NJ: Prentice Hall.

ing (e.g., Ford’s offering of incentives at its auto

Beil, D. (2010). Procurement auctions. In J. J. Hasenbein (Ed.),

dealers). The key is to find a good predictive demand

2010 tutorials in operations research: Risk and optimization

in an uncertain world. Linthicum, MD: INFORMS.

model: At price p, what is the expected demand

Campbell, G. (2009). Overview of workforce scheduling software.

d( p) for the product? Demand models may be linear

Production and Inventory Management Journal, 45(2), 7—22.

(d( p) = a-bp), exponential (i.e., constant elastici-

Cisco. (2013). Building a collaboration architecture for a global

ty), logit (i.e., S-curve), or discrete-choice. There

supply chain. Retrieved June 14, 2013, from http://www.

are many vendors of dynamic pricing software, and

cisco.com/en/US/solutions/collateral/ns340/ns858/c22- 613680_sOview.html

software calibrates the demand models using histor-

Farasyn, I., Humair, S., Kahn, J., Neale, J., Rosen, O., Ruark, J.,

ical point-of-sale data. In addition, data on available

et al. (2011). Inventory optimization at Procter & Gamble:

inventories is necessary for the price-optimization

Achieving real benefits through user adoption of inventory

algorithm. Different price-optimization algorithms

tools. Interfaces, 41(1), 66—78.

are embedded in these packages based on non-linear

Fite, J., Taylor, G., Usher, J., English, J., & Roberts, J. (2002).

Forecasting freight demand using economic indices. Interna- and dynamic programming.

tional Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Manage- ment, 32(4), 299—308.

Funaki, K. (2009). State of the art survey of commercial software 7. Conclusion

for supply chain design. Retrieved June 18, 2013, from http://

www.scl.gatech.edu/research/supply-chain/GTSCL_ scdesign_software_survey.pdf

Supply chain management is a fertile area for the

Funke, B., & Gruenert, T. (2005). Local search for vehicle routing

application of analytics techniques, which has his-

and scheduling problems: Review and conceptual integration.

torically been the case through the use of operations

Journal of Heuristics, 11(4), 267—306. Supply chain analytics 605

Graves, S., & Willems, S. P. (2000). Optimizing strategic safety

inertia, and transition hazard. Production and Operations

stock placement in supply chains. Manufacturing and Service Management, 17(3), 385—396.

Operations Management, 2(1), 68—83.

Safavi, A. (2005). Forecasting demand in the aerospace and

Jacobs, R., Berry, W., Whybark, D. C., & Vollmann, T. (2011).

defense industry. Journal of Business Forecasting, 24(1),

Manufacturing planning and control for supply chain manage- 2—7. ment. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Snyder, L. V., & Shen, Z-J. M. (2011). Fundamentals of supply

Krishna, V. (2002). Auction theory. New York: Academic Press.

chain theory. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Lee, H. (1996). Effective inventory and service management

Talluri, K., & Van Ryzin, G. (2004). The theory and practice of

through product and process redesign. Operations Research,

revenue management. New York: Springer. 44(1), 151—196.

Tsikoudakis, M. (2013, January 13). Supply chain disasters and

McDonald, R. (2011, November). Inside P&G’s digital revolution.

disruptions can cause lasting reputation damage. Business

McKinsey Quarterly. Available at http://www.mckinsey.com/

Insurance. Retrieved June 14, 2013, from http://www.

insights/consumer_and_retail/inside_p_and_ampgs_digital_

businessinsurance.com/article/20130113/NEWS06/ revolution 301139968

Pinedo, M. (2008). Scheduling theory, algorithms and systems

Wang, W., Ferguson, M., Hu, S., & Souza, G. C. (2013). Dynamic (3rd ed.). New York: Springer.

capacity investment with two competing technologies.

Rey, T., Kordon, A., & Wells, C. (2012). Applied data mining for

Manufacturing and service operations management, 15(4),

forecasting using SAS. Cary, NC: SAS Institute. 616—629.

Rey, T., & Wells, C. (2013, March 7). Integrating data mining and

Ward, J., Zhang, B., Jain, S., Fry, C., Olavson, H., Amaral, J.,

forecasting. Analytics. Retrieved June 17, 2013, from http://

et al. (2010). HP transforms product portfolio management

www.analytics-magazine.org/march-april-2013/765-

with operations research. Interfaces, 40(1), 17—32.

integrating-data-mining-and-forecasting

Zipkin, P. (2000). Foundations of inventory management.

Rungtusanatham, M. J., & Salvador, F. (2008). From mass produc- New York: McGraw-Hill.

tion to mass customization: Hindrance factors, structural

Document Outline

- Supply chain analytics

- Why analytics in supply chain management?

- Plan: Demand forecasting using predictive analytics

- Source

- Source: Strategic decisions

- Source: Tactical decisions

- Make

- Make: Strategic decisions

- Make: Tactical decisions

- Make: Operational decisions

- Deliver and return

- Deliver and return: Strategic decisions

- Deliver and return: Tactical decisions

- Deliver and return: Operational decisions

- Modulating demand to match capacity: Revenue management

- Conclusion

- References