Preview text:

12 Maintaining Positive Employee Relations OVERVIEW:

In this chapter, we will cover... ■ Employee Relations

■ Employee Relations Programs For Building and

Maintaining Positive Employee Relations ■ The Ethical Organization

■ Managing Employee Discipline

■ Employee Engagement Guide For Managers MyLab Management Improve Your Grade! LEARNING OBJECTIVES When you see this icon, visit

www.pearson.com/mylab/management for

When you finish studying this chapter, you should be able to:

activities that are applied, personalized, and offer immediate feedback. 1. Define employee relations.

2. Discuss at least four methods for managing employee relations.

3. Explain what is meant by ethical behavior.

4. Explain what is meant by fair disciplinary practices.

5. Answer the question, “How do companies become ‘Best Compa- nies to Work For’?” Learn It

If your professor has chosen to assign this, go to www.pearson.com/mylab/

management to see what you should particularly focus on and to take the Chapter 12 Warm Up. 39 3 7 9

398 PART 5 • EMPLOYEE AND LABOR RELATIONS INTRODUCTION

Enrique had worked as a waiter at a well-known all-night restaurant in the Coney

Island section of Brooklyn, New York for several years. He enjoyed the job, but not

the commute. Unless he left the restaurant promptly at 1:00 a.m., he’d miss his Q

train connection to his home in Queens. Then, what should be a 45-minute train

and bus ride would take him 2 1/2 hours. One night, two noisy out-of-town men sat

down at one of his tables at about 12:45 a.m. When he explained he’d have to leave

in 15 minutes, they objected loudly. Enrique’s supervisor came over and told him

he’d just have to stay until they finished their meal. That could keep him working

until 2:00A.M. Enrique followed his supervisor back to the kitchen and told him, “Let

someone else take over; you know I have to get home.” His supervisor smiled and

said, “Enrique, if you don’t like your job here, I know many people who would.”

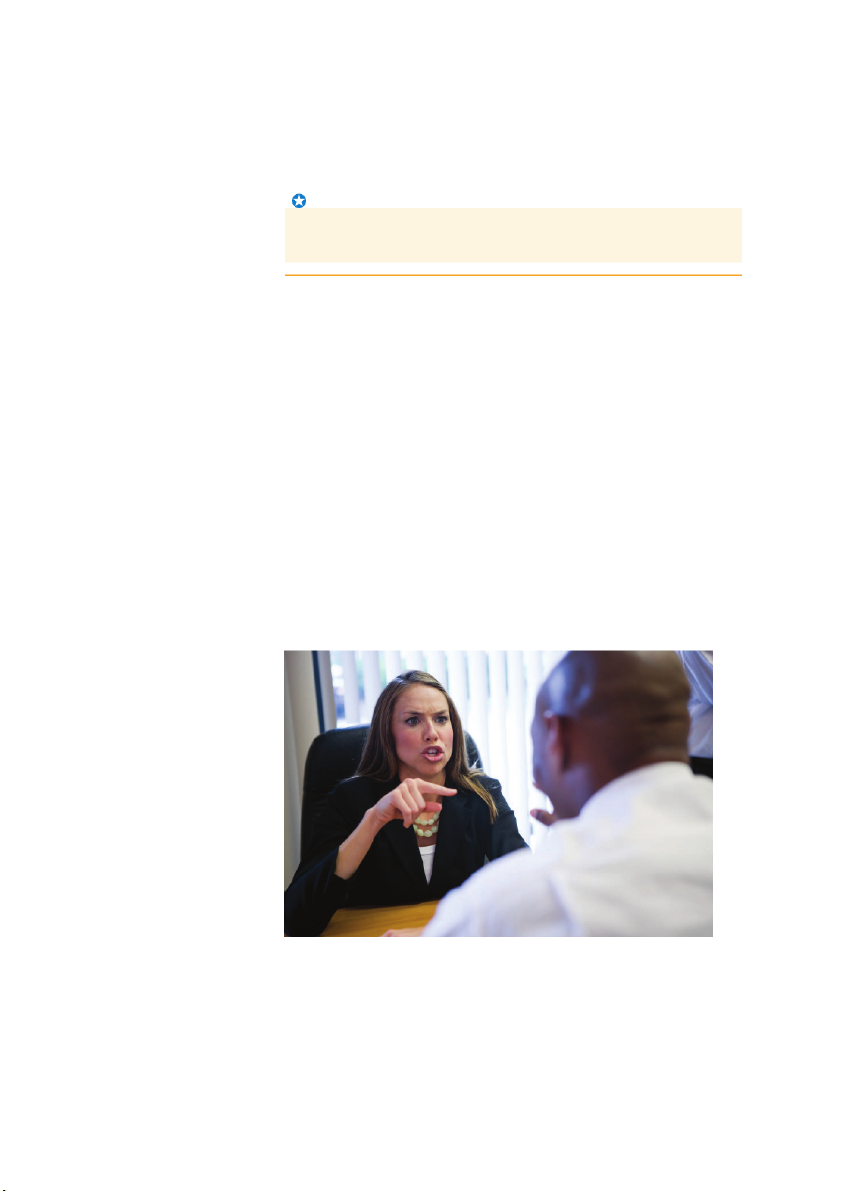

Source: Franek Strzeszewski/Getty Images. LEARNING OBJECTIVE 1 Define employee Employee Relations relations.

It’s obvious to anyone who has worked for even a few days that some companies

are better to work for than are others. Some companies we’ve touched on in this

book—Wegmans, SAS, and Google, for instance—show up repeatedly on “Best

Companies to Work For” lists, while others seem to always have labor problems

and negative press. This commonsense observation reflects the fact that some W LE O D

companies do have better employee relations than do others. G N K E

Employee relations is the management activity that involves establishing and B

maintaining the positive employee–employer relationships that contribute to sat- A S E employee relations

isfactory productivity, motivation, morale, and discipline, and to maintaining a

The activity that involves establish-

positive, productive, and cohesive work environment.1 Whether you’re recruiting

ing and maintaining the positive

employees, asking employees to work overtime, managing union organizing cam-

employee–employer relationships

paigns, or doing some other task, it obviously makes sense to have employees “on

that contribute to satisfactory

your side.” Many employers therefore endeavor to build positive employee rela-

productivity, motivation, morale,

and discipline, and to maintaining

tions, on the sensible assumption that doing so beats building negative ones. Man-

a positive, productive, and cohe-

aging employee relations is usually assigned to HR and is a topic human resource sive work environment.

management certification tests address.

CHAPTER 12 • MAINTAINING POSITIVE EMPLOYEE RELATIONS 399 LEARNING OBJECTIVE 2 Discuss at least four

Employee Relations Programs For Building methods for managing

and Maintaining Positive Employee Relations employee relations.

HR activities such as effective training, fair appraisals, and competitive pay and

benefits (all of which we discussed in previous chapters) can go far toward building

positive employee relations. However, most employers also institute special

“employee relations programs.” These programs include employee fair treatment

programs, programs for improving employee relations through improved com-

munications, employee recognition/relations programs, employee involvement

programs, and having fair and predictable disciplinary procedures. We’ll begin

with how to ensure fair treatment. W LE O D Ensuring Fair Treatment G N K E

Unfair treatment at work is demoralizing. It reduces morale, poisons trust, increases B

stress, and negatively impacts employee relations and performance.2 Employees of A S E

abusive supervisors are more likely to quit and to report lower job and life satisfac-

tion and higher stress.3 The effects on employees of such abusiveness are particu-

larly pronounced where the abusive supervisors seem to have support from fair treatment

higher-ups.4 Even when someone witnesses abusive supervision vicariously—for

Reflects concrete actions, such

instance, by seeing a coworker being abused—it triggers adverse reactions,

as “employees are treated with

including further unethical behavior.5 At work, fair treatment reflects concrete

respect,” and “employees are

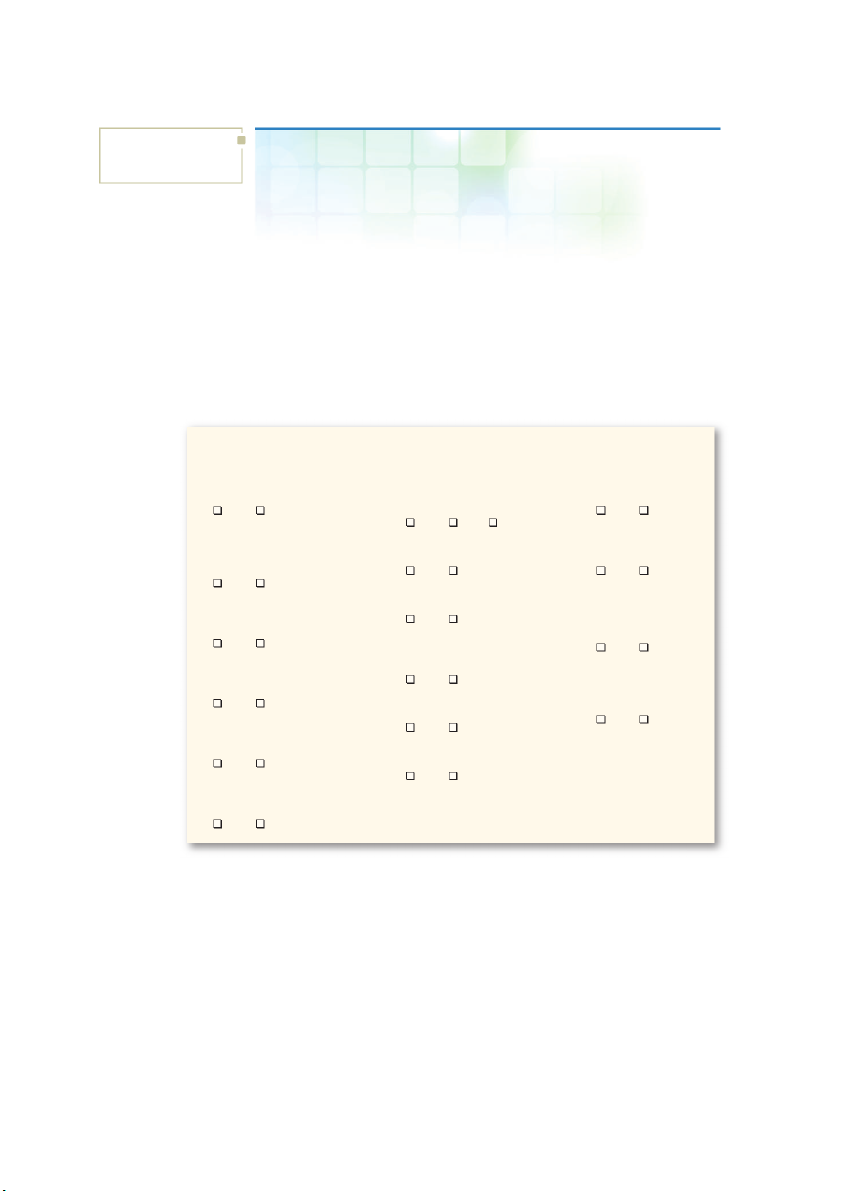

actions such as “employees are treated with respect,” and “employees are treated treated fairly.” fairly” (see Figure 12.1).6 Figure 12.1

What is your organization like most of the time? Circle Yes if the item describes your Perceptions of Fair

organization, No if it does not describe your organization, and ? if you cannot decide. Interpersonal Treatment Scale IN THIS ORGANIZATION: Source: “The Perceptions of

1. Employees are praised for good work Yes ? No Fair Interpersonal Treatment Scale: Development and

2. Supervisors yell at employees (R) Yes ? No Validation of a Measure of

3. Supervisors play favorites (R) Yes ? No

Interpersonal Treatment in the Workplace” by Michelle A. 4. Employees are trusted Yes ? No Donovan, Journal of Applied

5. Employees’ complaints are dealt with effectively Yes ? No Psychology, 1998, Volume 83(5).

6. Employees are treated like children (R) Yes ? No

7. Employees are treated with respect Yes ? No

8. Employees’ questions and problems are responded Yes ? No to quickly 9. Employees are lied to (R) Yes ? No

10. Employees’ suggestions are ignored (R) Yes ? No

11. Supervisors swear at employees (R) Yes ? No

12. Employees’ hard work is appreciated Yes ? No

13. Supervisors threaten to fire or lay off employees (R) Yes ? No

14. Employees are treated fairly Yes ? No

15. Coworkers help each other out Yes ? No

16. Coworkers argue with each other (R) Yes ? No

17. Coworkers put each other down (R) Yes ? No

18. Coworkers treat each other with respect Yes ? No

Note: R = the item is reverse scored

400 PART 5 • EMPLOYEE AND LABOR RELATIONS

There are many reasons why managers should be fair, including the golden

rule. What may not be so obvious is that unfairness can backfire. For example,

victims of unfairness exhibit more workplace deviance, such as theft and sabo-

tage.7 They also suffer a range of ill effects including poor health, strain, and

psychological conditions.8 Unfairness leads to increased tensions between the

employee and his or her family or partner.9 Abusive supervisors undermine their

subordinates’ effectiveness and may prompt them to act destructively.10 In terms

of employee relations, employees’ perceptions of fairness correlate with enhanced

employee commitment; enhanced satisfaction with the organization, jobs, and

leaders; and enhanced organizational citizenship behaviors.11

A study illustrates the effects of unfairness. College instructors first completed

surveys concerning the extent to which they saw their colleges as treating them procedural justice

with procedural and distributive justice. (Procedural justice refers to justice in the

Refers to just procedures in the

allocation of rewards or discipline, in terms of the procedures being even-handed

allocation of rewards or discipline,

and fair; distributive justice refers to a system distributing rewards and discipline

in terms of the actual procedures

in which the actual results or outcomes are even-handed and fair.) Procedural being even-handed and fair.

justice items included, for example, “In general, the department/college’s proce- distributive justice

dures allow for requests for clarification or for additional information about a

Refers to a system of distributing

decision.” Distributive justice items included, “I am fairly rewarded considering

rewards and discipline in which

the responsibilities I have.”

the actual results or outcomes are

Then the instructors completed organizational commitment questionnaires, even-handed and fair.

with items such as “I am proud to tell others that I am part of this department/

college.” Their students then completed surveys, with items such as “The instructor

was sympathetic to my needs” and “The instructor treated me fairly.”

The results were impressive. Instructors who perceived high distributive and

procedural justice were more committed. Furthermore, these instructors’ students

reported higher levels of instructor effort, prosocial behaviors, and fairness, and

had more positive reactions to their instructors.12 So in this case, treating profes-

sors badly backfired on the university. Treating others fairly produced improved

employee commitment and results.

The accompanying HR Practices Around the Globe feature shows how one

employer in China improved the fairness with which it treated employees. HR Practices Around the Globe

The Foxconn Plant in Shenzhen, China

The phrase social responsibility tends to trigger images of charitable contributions and

helping the homeless, but it actually refers to much more. For example, it refers to the

honesty of the company’s ads; to the quality of the parts it builds into its products; and

to the honesty, ethics, fairness, and “rightness” of its dealings with customers, suppliers,

and, of course, employees. The basic social responsibility question is always whether

the company is serving all its constituencies (or “stakeholders”) fairly and honestly. social responsibility

Corporate social responsibility thus refers to the extent to which companies should Refers to the extent to which

and do channel resources toward improving one or more segments of society other

companies should and do channel

than just the firm’s owners or stockholders.13

resources toward improving one

A worker uprising at Apple’s Foxconn iPhone assembly plant in Shenzhen, China or more segments of society

shows that workers around the globe want their employers to treat them in a fair and

other than the firm’s owners or socially responsible manner. stockholders.

After the uprising over pay and work rules at the Foxconn plant, Apple asked the

plant’s owner to have the Fair Labor Association (FLA) survey the plant’s workers. The

FLA found “tons of issues.”14 For example, employees faced “overly strict” product-

quality demands without adequate training: “Every job is tagged to time, there are

targets on how many things must be completed within an hour,” said Xie Xiaogang, 22,

who worked at Foxconn’s Shenzhen plant. “In this environment, many people cannot

take it.”15 Heavy overtime work requirements and having to work through a holiday week were other examples.

CHAPTER 12 • MAINTAINING POSITIVE EMPLOYEE RELATIONS 401

Hon Hai, the Foxconn plant’s owner, soon changed its plant human resource prac-

tices, for instance, raising salaries and cutting mandatory overtime. Those changes were

among 284 made by Foxconn after the audits uncovered violations of Chinese regula-

tions.16 The changes show that fair treatment is a global obligation. Talk About It – 1

If your professor has chosen to assign this, go to www.pearson.com/mylab/

management to discuss the following question. How would you explain the fact that

workers in such diverse cultures as America and China seem to crave fair treatment?

Bullying Some workplace unfairness is subtle. For example, unstated policies

requiring law firm associates to work seven days per week may unfairly eliminate

working mothers from partner tracks. Other unfairness is blatant. For example,

one survey of 1,000 U.S. employees concluded that about 45% said they had worked for abusive bosses.17

Unfortunately, bullying and abusiveness—singling out someone to harass and

mistreat—is a serious problem. The U.S. government (www.stopbullying.gov/) says

bullying involves three things:

• Imbalance of power. People who bully use their power to control or harm,

and the people being bullied may have a hard time defending themselves.

• Intent to cause harm. Actions done by accident are not bullying; the bully has a goal to cause harm.

• Repetition. Incidents of bullying happen to the same person over and over by

the same person or group, and that bullying can take many forms, such as:

• Verbal: name-calling, teasing

• Social: spreading rumors, leaving people out on purpose, breaking up friendships

• Physical: hitting, punching, shoving

• Cyberbullying: using the Internet, mobile phones, or other digital tech- nologies to harm others

Undoubtedly, the perpetrator is to blame for bullying. However, how some people

behave do make them more likely victims.18 Those “more likely” include submissive People who bully use their power to control or harm, and the people being bullied may have a hard time defending themselves.

Source: Purestock/Getty Images.

402 PART 5 • EMPLOYEE AND LABOR RELATIONS

victims (who seem more anxious, cautious, quiet, and sensitive), provocative vic-

tims (who show more aggressive behavior), and victims low in self-determination

(who seem to leave it to others to make decisions for them). High performers can

earn colleagues’ envy and thus suffer victimization.19 Victims of abusive super-

vision will often suffer in silence because they fear retribution.20 Building team

cohesion through team-building training, social gatherings, and friendly inter-team

competition can head off such envy and victimization.21

The employer and the manager are responsible for ensuring that the employee

is treated fairly and with respect, and that its employees treat each other respect-

fully.22 Techniques for minimizing unfairness (discussed in previous chapters)

include hiring competent and well-balanced employees and supervisors, ensuring

equitable pay, instituting fair performance appraisal systems, and having policies

requiring fair treatment of all employees. Communications systems and employee

involvement programs (discussed next) can also reduce unfairness and improve employee relations.

Improving Employee Relations Through Communications Programs

Many employers use communications programs to bolster their employee relations

efforts. They do this, first, on the reasonable assumption that employees feel better

about their employers when they’re “kept in the loop” about what is happening. For

example, one university’s website says, “We believe in keeping our employees fully

informed about our policies, procedures, practices and benefits.”23 This employer

uses an open-door policy to encourage communication between employees and man-

agers, an employee handbook covering basic employment information, and “the

opportunity to keep abreast of University events and other information of interest

through the website, e-mai ,l and hard copy memoranda.”24

To paraphrase one writer, no one likes getting complaints, but actively solicit-

ing complaints is important for employers who want to find out what’s bother-

ing employees, and to short-circuit inequitable treatment and maintain positive

employee relations.25 Options include hosting employee focus groups, making

available ombudsman and suggestion boxes, and implementing telephone and Web-based hotlines.

Some use hotline providers. A vendor sets up the hot lines for the employer,

receives the employees’ comments, and provides ongoing feedback to the employer

about employees’ concerns, as well as periodic summaries and trends. Exit inter-

views provide another opportunity to sample one’s employee relations.26 And

supervisors can use open-door policies and “management by walking around” to

informally ask employees “how things are going.”

Using Organizational Climate Surveys Employee attitude, morale, or climate

surveys often play a part in employee relations efforts. Employers use the surveys

to “take the pulse” of their employees’ attitudes toward organizational issues such

as leadership, safety, fairness, and pay, and to thereby get a sense of whether their

employee relations need improvement. The dividing lines between attitude surveys,

satisfaction or morale surveys, and climate surveys are somewhat arbitrary; several organizational climate

experts define organizational climate as the perceptions a company’s employees The perceptions a company’s

share about the firm’s psychological environment, for instance in terms of things

employees share about the firm’s

like concern for employees’ well-being, supervisory behavior, flexibility, apprecia-

psychological environment, for

tion, ethics, empowerment, political behaviors, and rewards.27

instance, in terms of things like

Many such surveys are available off the shelf. For instance, one SHRM sample

concern for employees’ well-being,

survey has employees use a scale from 1 (“to a very little extent”) to 5 (“to a very

supervisory behavior, flexibility,

great extent”) to answer questions such as, “Overall, how satisfied are you with appreciation, ethics, empower-

your supervisor?”, “Overall, how satisfied are you with your job?”, and “Does

ment, political behaviors, and rewards.

doing your job well lead to things like recognition and respect from those you work

with?”28 Many employers use online surveys from firms like Know Your Company

CHAPTER 12 • MAINTAINING POSITIVE EMPLOYEE RELATIONS 403

(http://knowyourcompany.com).29 Google conducts an annual “ Goo glegeist”

survey focusing on matters such as engagement and willingness to leave.30 Other

employers create specialized surveys. For example, we’ll look at the FedEx Survey

Feedback Action (SFA) program at the end of this chapter.

Develop Employee Recognition/Relations Programs

In addition to using two-way communications tools like climate surveys to help

improve employee relations, employers use other methods.

Most notable are employee recognition and award programs like those we

touched on in Chapters 10 and 11. For example, one trade journal notes how

one employer, the Murray Supply Co., held a special dinner for all its employees,

at which it gave out special awards for things like safe driving, tenure with the

company, branch employee of the year, and companywide employee of the year.31

As here, employers often distribute such awards with much fanfare at special

events such as awards dinners. One SHRM survey found that 76% of organiza-

tions surveyed had such employee recognition programs, and another 5% planned

to implement one within the next year.32

Instituting recognition and service award programs requires planning.33

For example, instituting a service award program requires reviewing the tenure

of existing employees and establishing meaningful award periods (one year, five

years, etc.). It also requires establishing a budget, selecting awards, having a pro-

cedure for monitoring what awards to actually award, having a process for giving

awards (such as special dinners or staff meetings), and periodically assessing

program success. Similarly, instituting a recognition program requires developing

criteria for recognition (such as customer service, cost savings, etc.), creating

forms and procedures for submitting and reviewing nominations, selecting mean-

ingful recognition awards, and establishing a process for actually awarding the recognition awards.

Use Employee Involvement Programs

Employee relations also tend to improve when employees get involved with the

company in positive ways, and so employee involvement is another useful employee relations strategy.

Getting employees involved in discussing and solving organizational issues

provides several benefits. Employees often know more about how to improve their

work processes than anyone, so asking them is often the simplest way to boost

performance. Getting them involved in addressing some issue will also hopefully

boost their sense of ownership of the process. It may also signal to them that their

opinions are valued, thereby contributing to better employee relations.

Employers use various means to encourage employee involvement. Some orga-

nize focus groups. A focus group is a small sample of employees who are presented

with a specific question or issue and who interactively express their opinions and

attitudes on that issue with the focus group’s assigned facilitator.

TRENDS SHAPING HR: Digital and Social Media

SOCIAL MEDIA AND EMPLOYEE INVOLVEMENT Many employers

use social media such as the photo-sharing website Pinterest to encourage

involvement.34 One survey found that just over half of employers use social

media tools to communicate with employees and to help develop a sense of

community.35 For example, Red Door Interactive used a Pinterest-based proj-

ect it called “San Diego Office Inspiration.” This encouraged employees to

contribute interior design and decor ideas for its new offices.36

404 PART 5 • EMPLOYEE AND LABOR RELATIONS

Using Employee Involvement Teams Employers also use teams to gain suggestion teams

employees’ involvement in organizational issues. Suggestion teams are temporary Temporary teams whose members

teams whose members work on specific assignments, such as how to cut costs or

work on specific analytical assign-

raise produc tivity. One employer, an airline, split employees such as baggage han-

ments, such as how to cut costs or

dlers and ground crew into separate teams, linking team members via its website raise productivity.

for brainstorming and voting on ideas.37 Some employers formalize this process problem-solving teams

by appointing semipermanent problem-solving teams. These teams identify and

Teams that identify and research

research work processes and develop solutions to work-related problems.38 They

work processes and develop solu-

usually consist of the supervisor and five to eight employees from a common work

tions to work-related problems. area.39 quality circle

A quality circle is a special type of formal problem-solving team, usually com-

A special type of formal problem-

posed of 6 to 12 specially trained employees who meet weekly to solve problems

solving team, usually composed of

affecting their work area.40 The team first gets training in problem-analysis tech-

6 to 12 specially trained employees

niques (including basic statistics). Then it applies the problem-analysis process who meet once a week to solve

(problem identification, problem selection, problem analysis, solution recommenda-

problems affecting their work area.

tions, and solution review by top management) to solve problems in its work area.41

In many facilities, specially trained teams of self-managing employees do their

jobs with little or no oversight from supervisors. For many, such teams epitomize self-managing/self-directed

employee involvement. A self-managing/self-directed work team is a small (usually work team

8 to 10 members) group of carefully selected, trained, and empowered employees

A small (usually 8 to 10 members)

who basically run themselves with little or no outside supervision, usually for the

group of carefully selected, trained,

purpose of accomplishing a specific task or mission.42 The “specific task or mis- and empowered employees who

sion” might be an Acura dashboard installed or a fully processed insurance claim.

basically run themselves with little

In any case, such teams have two distinguishing features. They are selected, trained,

or no outside supervision, usually

and empowered to supervise and do virtually all of their own work, and their work

for the purpose of accomplishing a

results in a specific item or service. specific task or mission.

For example, the GE aircraft engine plant in Durham, North Carolina is a self-

managing team-based facility. The plant’s workers work in teams, all of which report

to the factory manager.43 In such teams, employees “train one another, formulate

and track their own budgets, make capital investment proposals as needed, handle

quality control and inspection, develop their own quantitative standards, improve

every process and product, and create prototypes of possible new products.”44 As

the vice president of another company said about organizing his firm around teams,

“People on the floor were talking about world markets, customer needs, competi-

tors’ products, making process improvements—all the things managers are supposed to think about.”45

Using Suggestion Systems Employee suggestion systems can produce significant

savings and, through involvement and awards, improved employee relations. For

example, one study several years ago of 47 companies concluded that the firms

had saved more than $624 million in one year from their suggestion programs;

more than 250,000 suggestions were submitted, of which employers adopted over

93,000 ideas.46 Furthermore, employees like these programs. In one survey, 54%

of the 497 employees surveyed said they made more than 20 suggestions per year,

while another 24% said they made between 10 and 20 suggestions per year.47 The

accompanying HR in Practice feature provides an example. HR in Practice

The Cost-Effective Suggestion System48

A Lockheed Martin unit in Oswego, New York developed what it called its “Cost-Effec-

tiveness Plus” suggestion program to encourage and recognize employees for stream-

lining processes. With the Cost-Effectiveness Plus program, employees electronically

submit their ideas. These are then evaluated and approved by the local manager and

the program’s coordinator (and by higher management when necessary). This particular

CHAPTER 12 • MAINTAINING POSITIVE EMPLOYEE RELATIONS 405

program reportedly saves this facility about $77,000 per implemented idea, or more than $100 million each year.

Today’s suggestion systems are more sophisticated than the “suggestion boxes”

of years ago.49 The main improvements are in how the manager formalizes and com-

municates the suggestion process. The head of one company that designs and installs

suggestion systems lists the essential elements of an effective employee suggestion system as follows:50

• Senior staff support

• A simple, easy process for submitting suggestions

• A strong process for evaluating and implementing suggestions

• An effective program for publicizing and communicating the program

• A program focus on key organizational goals Talk About It – 2

If your professor has chosen to assign this, go to www.pearson.com/mylab/

management to discuss the following: Based on this, write a one-page outline

describing an employee suggestion system for a small department store. HR and the Gig Economy Getting Gig Workers Involved51

Can an employer do anything to make short-term gig workers who are “just passing

through” feel engaged in its activities? The answer, it seems, is “yes.”

First, understand that (like everyone), gig workers each come to the job with his or

her own set of needs. Most important, some gig workers are more “hobbyists,” while

others are in it full-time to support themselves and their families.

For example, one researcher interviewed Uber and Lyft drivers. He found that how

the drivers reacted to things like pay cuts depended on why the drivers were driving.

Many were not primarily driving for the money, but for social interaction and to relax

from their full-time jobs. (For example, one full-time psychotherapist who earned over

$100 per hour as a therapist wasn’t too upset by Uber pay cuts. He was just happy to

have a chance to unwind from 40 hours per week of helping people deal with their

problems). Most such “hobbyist” drivers weren’t financially dependent on driving. On

the other hand, drivers who were more financially dependent on driving were under-

standably quite upset by the cuts.

In any case, here are several suggestions for improving gig-worker employee relations:

• Don’t treat gig workers like they’re disposable. Even if it’s a short gig,

communicate with the worker and get to know him or her. Recognize their contributions.

• Make signing on as frictionless as possible. Many gig workers are looking for

part-time flexible gigs, and they want to work, not do paperwork.

• Research shows that most employers put little or no time into onboarding gig

workers, which is a mistake: even an abbreviated onboarding-welcoming process

is better than nothing. Put some time into giving them a brief background on

your company and project, and on making them feel part (but clearly an indepen-

dent-contractor part) of your business.

• Although it’s important legally to make it clear that they are independent con-

tractors, to the extent possible share company news and seek feedback from

your gig workers, and include them in intracompany communications and, to the

extent possible, in company social and educational events.

406 PART 5 • EMPLOYEE AND LABOR RELATIONS LEARNING OBJECTIVE 3 Explain what is meant by The Ethical Organization ethical behavior.

People face ethical choices every day. Is it wrong to use a company credit card for

personal purchases? Is a $50 gift to a client unacceptable? Compare your answers

by doing the quiz in Figure 12.2.

Most everyone reading this book rightfully views themselves as an ethical

person, so why include ethics in a human resource management book? For three

reasons: First, ethics is not theoretical. Instead, it greases the wheels that make

businesses work. Managers who promise raises but don’t deliver, salespeople who

say “The order’s coming” when it’s not, production managers who take kickbacks

from suppliers—they all corrode the trust that day-to-day business transactions depend on.

Second, it is hard to even imagine an e

un thical company with good employee relations.

Third, ethical dilemmas are part of human resource management. For example,

your team shouldn’t start work on the new machine until all the safety measures

are checked, but your boss is pressing you to start: What should you do? One

survey found that 6 of the 10 most serious ethical work issues—workplace safety, Figure 12.2

The Wall Street Journal Workplace Ethics Quiz

Source: Ethics and Compliance Officer Association, Waltham, MA and the Ethical Leadership Group, Global

Compliance’s Expert Advisors, Wilmette, IL. (Printed in The Wall Street Journal, October 21, 1999, pp. B1–B4).

© 1999 by Ethics and Compliance Officer Association. Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

CHAPTER 12 • MAINTAINING POSITIVE EMPLOYEE RELATIONS 407

employee records security, employee theft, affirmative action, comparable work,

and employee privacy rights—were HR-related.52 Another found that 54% of

human resource professionals surveyed had observed misconduct ranging from

violations of Title VII to violations of the Occupational Safety and Health Act.53 ethics

Ethics are “the principles of conduct governing an individual or a group”—the

The study of standards of conduct

principles people use to decide what their conduct should be.54 Of course, not all

and moral judgment; also the stan-

conduct involves ethics.55 For example, buying an iPad usually isn’t an ethical dards of right conduct.

decision. Instead, ethical decisions are rooted in morality. Morality refers to

society’s accepted standards of behavior. To be more precise, morality (and there-

fore ethical decisions) always involves the most fundamental questions of what is

right and wrong, such as stealing, murder, and how to treat other people. W LE O DG N K E Ethics and Employee Rights B A S E

Societies don’t rely on employers’ ethics or sense of fairness or morality to ensure

that they do what’s right. Societies also institute various laws and procedures for

enforcing these laws. These laws lay out what employers can and cannot do, for

instance, in terms of discriminating based on race. In so doing, these laws also

carve out explicit rights for employees. For example, Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act gives employees the right to bring legal charges against an employer who they

believe discriminated against them due to race.

Employee rights is thus part and parcel of all the employment laws we discuss

in this book. For example, the National Labor Relations Act established the right

of employees to engage in collective bargaining. And the Fair Labor Standards Act

gave employees the right to a minimum wage and overtime pay.

The bottom line is that although ethics, fairness, and morality certainly help

determine how employers treat their employees, remember that the enforceable

rights embedded in employment law also govern what employers and employees can do.

What Shapes Ethical Behavior at Work?

Why do people do bad things? It’s complicated. However one review of over

30 years of ethics research concluded that three factors combine to determine the

ethical choices we make.56 The authors titled their paper “Bad Apples, Bad Cases,

and Bad Barrels.” This title highlighted their conclusion that when

“Bad apples” (people who are inclined to make unethical choices) must deal with

“Bad cases” (ethical situations that are ripe for unethical choices) while working in

“Bad barrels” (company environments that foster or condone unethical

choices), . . . then this mixture combines to determine whether someone acts ethically.

Here’s a closer look at what they found.

The Person (What Makes Bad Apples?)

First, because people bring to their jobs their own ideas of what is morally right

and wrong, each person must shoulder much of the credit (or blame) for his or her ethical choices.

For example, researchers surveyed CEOs to study their intentions to engage

in two questionable practices: soliciting a competitor’s technological secrets and

making illegal payments to foreign officials. The researchers concluded that the

CEOs’ personal predispositions more strongly affected their decisions than did

outside pressures or characteristics of their firms.57 The most principled people,

with the highest level of “cognitive moral development,” think through the impli-

cations of their decisions and apply ethical principles. How would you rate your

408 PART 5 • EMPLOYEE AND LABOR RELATIONS

own ethics? Figure 12.2 (page 406) presented a short self-assessment survey (you’ll

find typical survey takers’ answers on page 425). Furthermore, employees who

identify more strongly with the organization are also more likely to engage in

unethical actions to support it, so strong loyalty isn’t always a blessing.58 Similarly,

employees who worry about being excluded from a group may support the group’s

unethical behavior just to stay in the group.59

Which Ethical Situations Make for Ethically Dangerous (Bad Cases) Situations?

But, it’s not just the person but the type of decision that’s important. For example,

these researchers found that “smaller” ethical dilemmas prompt more bad choices.

What determines “small”? Basically, how much harm can befall victims of the

choice, or the number of people potentially affected. People seemed more likely to

“do the wrong thing” in “less serious” situations, in other words. That obviously

doesn’t mean that some people don’t do bad things when huge consequences are

involved; it just means that people seem to cut more ethical corners when small

things are involved. The problem is that one thing often leads to another; people

start by doing small bad things and then “graduate” to larger ones.60 W LE O DG N E

What Are the “Bad Barrels”?—The Outside Factors K B That Mold Ethical Choices A S E

Finally, the study concluded that some companies produce more poisonous social

environments (“outside factors” or “barrels”) than do others; these bad environ-

ments in turn trigger unethical choices.61 For example, companies that encouraged

an “everyone for him or herself” culture were more likely to suffer from unethical

choices. Those that encouraged employees to consider the well-being of everyone had

more ethical choices. Most important, a company whose managers put in place “a

strong ethical culture that clearly communicates the range of acceptable and unac-

ceptable behavior” was associated with fewer unethical decisions in the workplace.62

Steps Managers Take to Create More Ethical Environments

Given this, here are some steps managers can take to create more ethical environments.

Reduce Job-Related Pressures If people did unethical things at work solely for

personal gain, it perhaps would be understandable (though inexcusable). The scary

thing is that it’s often not personal interests but the pressures of the job. As one

former executive said at his trial, “I took these actions, knowing they were wrong,

in a misguided attempt to preserve the company to allow it to withstand what I

believed were temporary financial difficulties.”63

A study illustrates this. It asked employees to list their reasons for taking

unethical actions at work.64 For most of these employees, “meeting schedule pres-

sures,” “meeting overly aggressive financial or business objectives,” and “helping

the company survive” were the three top causes. “Advancing my own career or

financial interests” ranked about last.65 Reducing such “outside” pressures helps head off ethical lapses.

“Walk the Talk” It’s hard to resist even subtle pressure from one’s boss. So it’s not

surprising that according to one report, “the level of misconduct at work dropped

dramatically when employees said their supervisors exhibited ethical behavior.”66

Examples of how supervisors lead subordinates astray ethically include:

• Tell staffers to do whatever is necessary to achieve results.

• Overload top performers to ensure that work gets done.

CHAPTER 12 • MAINTAINING POSITIVE EMPLOYEE RELATIONS 409

• Look the other way when wrongdoing occurs.

• Take credit for others’ work or shift blame.67

Some managers also urge employees to apply a quick “ethics test” to evaluate

whether what they’re about to do fits the company’s code of conduct. For example,

Raytheon Co. asks employees who face ethical dilemmas to ask: Is the action legal? Is it right? Who will be affected?

Does it fit Raytheon’s values?

How will it “feel” afterward?

How will it look in the newspaper?

Will it reflect poorly on the company?68

Have Ethics Policies and Codes Managers use ethics policies and codes to signal

that their companies are serious about ethics. For example, IBM’s code of ethics says, in part:

Neither you nor any member of your family may, directly or through

others, solicit or accept from anyone money, a gift, or any amenity that

could influence or could reasonably give the appearance of influencing

IBM’s business relationship with that person or organization. If you or

your family members receive a gift (including money), even if the gift was

unsolicited, you must notify your manager and take appropriate measures,

which may include returning or disposing of what you received.69

Enforce the Rules Having rules without enforcing them is futile. Managers’ state-

ments and encouragement can reduce unethical employee behavior, but knowing

that one’s behavior is actually being monitored and the rules enforced is what

has the biggest impact.70 Ethics audits monitor things like conflicts of interest,

giving and receiving gifts, employee discrimination, and access to company infor-

mation.71 One study found that fraud controls such as whistleblower hotlines,

surprise audits, fraud training for employees, and mandatory vacations can each

reduce internal theft by around 50%.72 Firms, such as Lockheed Martin Corp.,

also appoint chief ethics officers.73 W LE O DG N E

Encourage Whistleblowers Some companies encourage employees to use hot- K

lines and other means to “blow the whistle” on the company when they discover B A S E

fraud. Several U.S. laws, including Dodd Frank, the False Claims Act, the U.S.

Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act, and U.S. federal

sentencing guidelines address whistleblowing.74 Under the U.S. Securities and

Exchange Commission’s whistleblower program, whistleblowing awards aren’t

just limited to company employees. Consultants, independent contractors, ven-

dors, and sometimes even internal audit and compliance personnel, working in

the United States or abroad, are also eligible.

Foster the Right Culture75 Managing people and shaping their behavior depends

on shaping the values they use as behavioral guides. For example, if management

really believes “honesty is the best policy,” the actions it takes should reflect this

value. Managers therefore have to think through how to send the right signals to organizational culture

their employees—in other words, create the right culture. Organizational culture

The characteristic values, tradi-

is the “characteristic values, traditions, and behaviors a company’s employees

tions, and behaviors a company’s

share.” A value is a basic belief about what is right or wrong, or about what you employees share.

should or shouldn’t do. (“Honesty is the best policy” would be a value.) Creating a culture involves: