Preview text:

18

THERMAL PROPERTIES OF MATTER 18.1. (a)

IDENTIFY: We are asked about a single state of the system.

SET UP: Use Eq. (18.2) to calculate the number of moles and then apply the ideal-gas equation. 4 m 4.86 ×10− kg EXECUTE: tot n = = = 0.122 mol. 3 M 4.00 ×10− kg/mol

(b) pV = nRT implies p = nRT /V . T must be in kelvins, so T = (18 + 273) K = 291 K.

(0.122 mol)(8.3145 J/mol ⋅ K)(291 K) 4 p = =1.47 ×10 Pa. 3 − 3 20.0 ×10 m 4 5

p = (1.47 ×10 Pa)(1.00 atm/1.013×10 Pa) = 0.145 atm.

EVALUATE: The tank contains about 1/10 mole of He at around standard temperature, so a pressure

around 1/10 atmosphere is reasonable. 18.2.

IDENTIFY: pV = nRT. SET UP: 1 T = 41.0 C

° = 314 K. R = 0.08206 L ⋅ atm/mol ⋅ K. pV p V p V

EXECUTE: n and R are constant so = nR is constant. 1 1 2 2 = . T 1 T 2 T

⎛ p ⎞⎛ V ⎞ 2 2 3 2 T = 1 T ⎜ ⎟⎜

⎟ = (314 K)(2)(2) =1.256×10 K = 983 C ° . ⎝ 1 p ⎠⎝ 1 V ⎠ pV (b) (0.180 atm)(2.60 L) n = = = 0.01816 mol. RT

(0.08206 L ⋅ atm/mol ⋅ K)(314 K) tot m

= nM = (0.01816 mol)(4.00 g/mol) = 0.0727 g.

EVALUATE: T is directly proportional to p and to V, so when p and V are each doubled the Kelvin

temperature increases by a factor of 4.

18.3. IDENTIFY: pV = nRT.

SET UP: T is constant.

EXECUTE: nRT is constant so 1 p 1 V = 2 p 2 V . 3 ⎛ V ⎞ ⎛ ⎞ 1 0.110 m 2 p = 1 p ⎜ ⎟ = (0.355 atm)⎜ ⎟ = 0.100 atm. ⎜ 3 ⎟ ⎝ 2 V ⎠ 0.390 m ⎝ ⎠

EVALUATE: For T constant, p decreases as V increases.

18.4. IDENTIFY: pV = nRT. SET UP: 1 T = 20.0 C ° = 293 K. p nR p p

EXECUTE: (a) n, R and V are constant. = = constant. 1 2 = . T V 1 T 2 T ⎛ p ⎞ 2 ⎛ 1.00 atm ⎞ 2 T = 1 T ⎜ ⎟ = (293 K)⎜ ⎟ = 97.7 K = 1 − 75 C. ° ⎝ 1 p ⎠ ⎝ 3.00 atm ⎠

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. 18-1 18-2 Chapter 18 (b) 2 p =1 0 . 0 atm, 2 V = 3.00 L. 3

p = 3.00 atm. n, R and T are constant so pV = nRT = constant. 2 p 2 V = 3 p 3 V . ⎛ p ⎞ 2 ⎛ 1 0 . 0 atm ⎞ 3 V = 2 V ⎜ ⎟ = (3 0 . 0 L)⎜ ⎟ =1.00 L. ⎝ 3 p ⎠ ⎝ 3.00 atm ⎠

EVALUATE: The final volume is one-third the initial volume. The initial and final pressures are the same,

but the final temperature is one-third the initial temperature.

18.5. IDENTIFY: We know the pressure and temperature and want to find the density of the gas. The ideal gas law applies.

SET UP: MCO = (12 + 2[16]) g/mol = 44 g/mol. M = 28 g/mol. ρ = pM . 2 N2 RT

R = 8.315 J/mol ⋅ K. T must be in kelvins. Express M in kg/mol and p in Pa. 5 1 atm =1.013×10 Pa. 3 (650 Pa)(44 10− × kg/mol) EXECUTE: (a) 3 Mars: ρ = = 0.0136 kg/m . (8.315 J/mol ⋅ K)(253 K) 5 3

(92 atm)(1.013 10 Pa/atm)(44 10− × × kg/mol) 3 Venus: ρ = = 67.6 kg/m . (8.315 J/mol ⋅ K)(730 K) Titan: 178 T = − + 273 = 95 K. 5 3

(1.5 atm)(1.013 10 Pa/atm)(28 10− × × kg/mol) 3 ρ = = 5.39 kg/m . (8.315 J/mol ⋅ K)(95 K)

EVALUATE: (b) Table 12.1 gives the density of air at 20°C and p = 1 atm to be 3 1.20 kg/m . The density

of the atmosphere of Mars is much less, the density for Venus is much greater and the density for Titan is somewhat greater.

18.6. IDENTIFY: pV = nRT and the mass of the gas is tot m = nM.

SET UP: The temperature is T = 22 0 . °C = 295 1

. 5 K. The average molar mass of air is 3 M 28 8 10− = . × kg/mol. For helium 3 M 4 00 10− = . × kg/mol. −3 pV (1 00 . atm)(0.900 L)(28 8 . ×10 kg/mol) E − XECUTE: (a) 3 tot m = nM = M = =1 0 . 7 ×10 kg. RT

(0.08206 L ⋅ atm/mol ⋅ K)(295.15 K) −3 pV (1.00 atm)(0 9 . 00 L)(4.00 ×10 kg/mol) (b) −4 tot m = nM = M = = 1 4 . 9 ×10 kg. RT

(0.08206 L ⋅ atm/mol⋅ K)(295.15 K) N pV EVALUATE: n = =

says that in each case the balloon contains the same number of molecules. NA RT

The mass is greater for air since the mass of one molecule is greater than for helium.

18.7. IDENTIFY: We are asked to compare two states. Use the ideal gas law to obtain 2 T in terms of 1 T and

ratios of pressures and volumes of the gas in the two states.

SET UP: pV = nRT and n, R constant implies pV/T = nR = constant and 1 p 1 V / 1 T = 2 p 2 V / 2 T EXECUTE: 1

T = (27 + 273) K = 300 K 5 1 p =1.01×10 Pa 6 5 6 2

p = 2.72×10 Pa +1.01×10 Pa = 2.82×10 Pa (in the ideal gas equation the pressures must be absolute, not gauge, pressures) 6 3

⎛ p ⎞⎛V ⎞ ⎛ . × ⎞⎛ . ⎞ 2 2 2 82 10 Pa 46 2 cm 2 T = 1 T ⎜ ⎟⎜ ⎟ = 300 K⎜ ⎟⎜ ⎟ = 776 K ⎜ 5 ⎟⎜ 3 ⎟ ⎝ 1 p ⎠⎝ 1 V ⎠ 1 0 ⎝ . 1×10 Pa 499 cm ⎠⎝ ⎠ 2 T = (776 − 273) C ° = 503 C °

EVALUATE: The units cancel in the 2 V / 1

V volume ratio, so it was not necessary to convert the volumes in 3 cm to 3

m . It was essential, however, to use T in kelvins.

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Thermal Properties of Matter 18-3

18.8. IDENTIFY: pV = nRT and . m = nM

SET UP: We must use absolute pressure in pV = nRT. 5 1 p = 4.01×10 Pa, 5 2 p = 2 8 . 1×10 Pa. 1 T = 310 K, 2 T = 295 K. 5 3 p V (4 0 . 1×10 Pa)(0.075 m ) EXECUTE: (a) 1 1 1 n = = =11.7 mol. 1 RT (8.315 J/mol ⋅ K)(310 K) m = nM = (11 7 . mol)(32.0 g/mol) = 374 g. 5 3 p V (2 81 . ×10 Pa)(0.075 m ) (b) 2 2 2 n = = = 8 5 . 9 mol. 275 m = g. 2 RT (8 31 . 5 J/mol⋅ K)(295 K)

The mass that has leaked out is 374 g − 275 g = 99 g.

EVALUATE: In the ideal gas law we must use absolute pressure, expressed in Pa, and T must be in kelvins.

18.9. IDENTIFY: pV = nRT. SET UP: 1 T = 300 K, 2 T = 430 K. pV p V p V

EXECUTE: (a) n, R are constant so = nR = constant. 1 1 2 2 = . T T T 1 2 3

⎛ V ⎞⎛ T ⎞ ⎛ ⎞ 1 2 3 0.750 m ⎛ 430 K ⎞ 4 2 p = 1 p ⎜ ⎟⎜ ⎟ = (7.50×10 Pa)⎜ ⎟⎜ ⎟ =1.68×10 Pa. ⎜ 3 ⎟ ⎝ 2 V ⎠⎝ 1 T ⎠ 0.480 m ⎝ 300 K ⎠ ⎝ ⎠

EVALUATE: Since the temperature increased while the volume decreased, the pressure must have

increased. In pV = nRT , T must be in kelvins, even if we use a ratio of temperatures. 18.10.

IDENTIFY: Use the ideal-gas equation to calculate the number of moles, n. The mass to m tal of the gas is tota m l = nM .

SET UP: The volume of the cylinder is 2

V = πr l, where r = 0.450 m and 1 l = 5 . 0 m. T = 22.0 C ° = 293.15 K. 5 1 atm =1 013 . ×10 Pa. 3 M 32 0 10− = . × kg/mol. 8 R = .314 J/mol ⋅ K.

EXECUTE: (a) pV = nRT gives 5 2 pV (21.0 atm)(1 01

. 3 ×10 Pa/atm)π(0.450 m) (1.50 m) n = = = 827 mol. RT (8.314 J/mol⋅ K)(295.15 K) (b) 3 − tot

m al = (827 mol)(32.0×10 kg/mol) = 26.5 kg

EVALUATE: In the ideal-gas law, T must be in kelvins. Since we used R in units of J/mol ⋅ K we had to

express p in units of Pa and V in units of 3 m .

18.11. IDENTIFY: We are asked to compare two states. Use the ideal-gas law to obtain 1 V in terms of 2 V and the

ratio of the temperatures in the two states.

SET UP: pV = nRT and n, R, p are constant so V/T = nR/p = constant and 1 V / 1 T = 2 V / 2 T EXECUTE: 1

T = (19 + 273) K = 292 K (T must be in kelvins) 2 V = 1 V ( 2 T / 1 T ) = (0 60 . 0 L)(77 3 . K/ 292 K) = 0.159 L

EVALUATE: p is constant so the ideal-gas equation says that a decrease in T means a decrease in V. 18.12.

IDENTIFY: Apply pV = nRT and the van der Waals equation (Eq. 18.7) to calculate p. S − ET UP: 3 6 3 400 cm = 400×10 m . 8 R = .314 J/mol ⋅ K.

EXECUTE: (a) The ideal gas law gives 6

p = nRT/V = 7.28×10 P a while Eq. (18.7) gives 6 5.87 ×10 Pa.

(b) The van der Waals equation, which accounts for the attraction between molecules, gives a pressure that is 20% lower.

(c) The ideal gas law gives 5

p = 7.28×10 Pa. Eq. (18.7) gives 5 p = 7 1

. 3×10 Pa, for a 2.1% difference.

EVALUATE: (d) As n/V decreases, the formulas and the numerical values for the two equations approach each other. 18.13.

IDENTIFY: We know the volume of the gas at STP on the earth and want to find the volume it would

occupy on Venus where the pressure and temperature are much greater.

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. 18-4 Chapter 18

SET UP: STP is T = 273 K and p =1 atm. Set up a ratio using pV = nRT with nR constant. V

T =1003 + 273 = 1276 K. pV p V p V

EXECUTE: pV = nRT gives = nR = constant, so E E V V = . T E T V T ⎛ ⎞⎛ ⎞ E p V T ⎛ 1 atm ⎞⎛1276 K ⎞ V V = E V ⎜ ⎟⎜ ⎟ = V ⎜ ⎟⎜ ⎟ = 0.0508 . V ⎝ V p ⎠⎝ E T ⎠ ⎝ 92 atm ⎠⎝ 273 K ⎠

EVALUATE: Even though the temperature on Venus is higher than it is on Earth, the pressure there is

much greater than on Earth, so the volume of the gas on Venus is only about 5% what it is on Earth. 18.14.

IDENTIFY: pV = nRT. SET UP: 1 T = 277 K. 2

T = 296 K. Assume the number of moles of gas in the bubble remains constant. pV p V p V

EXECUTE: (a) n, R are constant so = nR = constant. 1 1 2 2 = and T 1 T 2 T V

⎛ p ⎞⎛ T ⎞ 2 1 2 ⎛ 3.50 atm ⎞⎛ 296 K ⎞ = ⎜ ⎟⎜ ⎟ = ⎜ ⎟⎜ ⎟ = 3.74. 1 V ⎝ 2 p ⎠⎝ 1 T ⎠ ⎝ 1 0 . 0 atm ⎠⎝ 277 K ⎠

(b) This increase in volume of air in the lungs would be dangerous.

EVALUATE: The large decrease in pressure results in a large increase in volume. 18.15.

IDENTIFY: We are asked to compare two states. First use pV = nRT to calculate 1 p . Then use it to obtain 2 T in terms of 1

T and the ratio of pressures in the two states.

(a) SET UP: pV = nRT. Find the initial pressure 1 p . nRT (11 0

. mol)(8.3145 J/mol⋅ K)(23.0 + 273.15)K EXECUTE: 1 6 1 p = = = 8 7 . 37×10 Pa 3 − 3 V 3.10×10 m SET UP: 5 7 2

p =100 atm(1.013×10 Pa/1 atm) = 1 0 . 13×10 Pa

p/T = nR/V = constant, so 1 p / 1 T = 2 p / 2 T 7 ⎛ p ⎞ ⎛ 1.013×10 Pa ⎞ EXECUTE: 2 2 T = 1 T ⎜ ⎟ = (296 15 . K)⎜ ⎟ = 343 4 . K = 70.2 C ° ⎜ 6 ⎟ ⎝ 1 p ⎠ 8 ⎝ .737 ×10 Pa ⎠

(b) EVALUATE: The coefficient of volume expansion for a gas is much larger than for a solid, so the

expansion of the tank is negligible. 18.16.

IDENTIFY: F = pA and pV = nRT

SET UP: For a cube, V/A = . L

EXECUTE: (a) The force of any side of the cube is F = pA = (nRT/V )A = (nRT )/L, since the ratio of area

to volume is A/V =1/ .

L For T = 20.0 C ° = 293.15 K, nRT

(3 mol)(8.3145 J/mol ⋅ K)(293.15 K) 4 F = = = 3.66×10 N. L 0 2 . 00 m

(b) For T = 100 00 . °C = 373.15 K, nRT (3 m ol)(8.3145 J/m ol⋅ K)(373.15 K) 4 F = = = 4.65×10 N. L 0.200 m

EVALUATE: When the temperature increases while the volume is kept constant, the pressure increases and

therefore the force increases. The force increases by the factor 2 T / 1 T . 18.17.

IDENTIFY: Example 18.4 assumes a temperature of 0 C

° at all altitudes and neglects the variation of g

with elevation. With these approximations, M / gy RT p 0 p e− = . S − − ET UP: ln( x e ) = − . x For air, 3 M = 28 8 . ×10 kg/mol. RT

EXECUTE: We want y for p = 0.90 0 p so 0 90 − . = Mgy/RT e and y = − ln(0.90) = 850 m. Mg

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Thermal Properties of Matter 18-5

EVALUATE: This is a commonly occurring elevation, so our calculation shows that 10% variations in

atmospheric pressure occur at many locations. 18.18.

IDENTIFY: From Example 18.4, the pressure at elevation y above sea level is M / gy RT p 0 p e− = . S −

ET UP: The average molar mass of air is 3 M = 28.8×10 kg/mol. 3 − 2 Mgy . × .

EXECUTE: At an altitude of 100 m, 1

(28 8 10 kg/mol)(9 80 m/s )(100 m) = = 0 0 . 1243, and the RT (8.3145 J/ mol⋅ K)(273 15 . K)

percent decrease in pressure is 0 − .01243 1− 0 p/p =1− e = 0.0124 =1 2 . 4 . , At an altitude of 1000 m, Mgy − . 2 /RT = 0 1

. 243 and the percent decrease in pressure is 0 1243 1− e = 0 1 . 17 =11.7 . ,

EVALUATE: These answers differ by a factor of (11.7%)/(1 24%) .

= 9.44, which is less than 10 because the

variation of pressure with altitude is exponential rather than linear. 18.19.

IDENTIFY: We know the volume, pressure and temperature of the gas and want to find its mass and density. S − − ET UP: 3 3 V = 3.00×10 m . 295 T = K. 8

p = 2.03×10 Pa. The ideal gas law, pV = nRT, applies.

EXECUTE: (a) pV = nRT gives 8 − 3 − 3 pV (2.03 × 10 Pa)(3.00 × 10 m ) 14 n = =

= 2.48 ×10− mol.The mass of this amount of gas is RT (8.315 J/mol ⋅ K)(295 K) 14 − 3 − 1 − 6

m = nM = (2.48 × 10

mol)(28.0 × 10 kg/mol) = 6.95 × 10 kg. 16 m 6.95 × 10− kg (b) 13 − 3 ρ = = = 2.32 ×10 kg/m . 3 − 3 V 3.00 × 10 m

EVALUATE: The density at this level of vacuum is 13 orders of magnitude less than the density of air at STP, which is 1.20 kg/m3. 18.20. IDENTIFY: Mgy/RT p 0 p e− =

from Example 18.4 gives the variation of air pressure with altitude. The pM density ρ of the air is ρ =

, so ρ is proportional to the pressure p. Let ρ be the density at the RT 0

surface, where the pressure is 0 p . 3 − 2 Mg (28.8×10 kg/mol)(9 8 . 0 m/s ) S − −

ET UP: From Example 18.4, 4 1 = =1 2 . 44×10 m . RT (8 31 . 4 J/mol⋅ K)(273 K) −4 −1 3 ρ M ρ ρ E − . × . × XECUTE: (1 244 10 m )(1 00 10 m) p = 0 p e = 0.883 0 p . = = constant, so 0 = and p RT p 0 p ⎛ p ⎞ ρ = ρ0 ⎜ ⎟ = 0 8 . 83ρ0. ⎝ 0 p ⎠

The density at an altitude of 1.00 km is 88.3% of its value at the surface.

EVALUATE: If the temperature is assumed to be constant, then the decrease in pressure with increase in

altitude corresponds to a decrease in density.

18.21. IDENTIFY: Use Eq. (18.5) and solve for p.

SET UP: ρ = pM/RT and p = RT ρ /M T = ( 5 − 6.5 + 273.15) K = 216.6 K For air 3 M 28 8 10− = . × kg/mol (Example 18.3) 3

(8.3145 J/mol ⋅ K)(216.6 K)(0.364 kg/m ) EXECUTE: 4 p = = 2 2 . 8×10 Pa 3 28.8×10− kg/mol

EVALUATE: The pressure is about one-fifth the pressure at sea-level. 18.22.

IDENTIFY: The molar mass is M = NA ,

m where m is the mass of one molecule. SET UP: 23

NA = 6.02 ×10 molecules/mol. E − XECUTE: 23 21

M = NAm = (6.02 ×10 molecules/mol)(1.41×10

kg/molecule) = 849 kg/mol.

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. 18-6 Chapter 18 E −

VALUATE: For a carbon atom, 3

M =12×10 kg/mol. If this molecule is mostly carbon, so the average 849 kg/mol

mass of its atoms is the mass of carbon, the molecule would contain = 71,000 atoms. 3 12 ×10− kg/mol 18.23. IDENTIFY: The mass tot

m is related to the number of moles n by tot m

= nM. Mass is related to volume by ρ = m/V.

SET UP: For gold, M =196.97 g/mol and 3 3

ρ =19.3×10 kg/m . The volume of a sphere of radius r is 4 3 V = π r . 3 EXECUTE: (a) tot m = nM = (3 0

. 0 mol)(196.97 g/mol) = 590.9 g. The value of this mass of gold is

(590.9 g)($14.75/g) = $8720. m 0 5 . 909 kg (b) 5 − 3 V = = = 3 0 . 6×10 m . 4 3 V = π r gives 3 3 ρ 19 3 . ×10 kg/m 3 1/3 1/3 5 − 3 ⎛ 3V ⎛ ⎞ 3[3.06×10 m ] ⎞ r = ⎜ ⎟ = ⎜ ⎟ = 0 019 . 4 m = 1 9

. 4 cm. The diameter is 2r = 3.88 cm. 4π ⎜ 4π ⎟ ⎝ ⎠ ⎝ ⎠

EVALUATE: The mass and volume are directly proportional to the number of moles. 18.24.

IDENTIFY: Use pV = nRT to calculate the number of moles and then the number of molecules would be N = nNA. S − ET UP: 5 1 atm =1 013 . ×10 Pa. 3 6 3 1 0 . 0 cm =1 0 . 0×10 m . 23 NA = 6 022 . ×10 molecules/mol. 14 − 5 6 − 3 pV (9 00

. ×10 atm)(1.013×10 Pa/atm)(1.00×10 m ) E − XECUTE: (a) 18 n = = = 3.655×10 mol. RT (8.314 J/mol ⋅ K)(300.0 K) 18 23 6 N nN − = A = (3.655 ×10

mol)(6.022×10 molecules/mol) = 2.20×10 molecules. pVN N VN N N (b) A N = so A = = constant and 1 2 = . RT p RT 1 p 2 p ⎛ ⎞ 2 p 6 ⎛ 1.00 atm ⎞ 19 N2 = 1 N ⎜ ⎟ = (2.20×10 molecules)⎜ ⎟ = 2 4 . 4×10 molecules. 14 − ⎝ 1 p ⎠ ⎝ 9 0 . 0×10 atm ⎠

EVALUATE: The number of molecules in a given volume is directly proportional to the pressure. Even at

the very low pressure in part (a) the number of molecules in 3 1 0 . 0 cm is very large. 18.25.

IDENTIFY: We are asked about a single state of the system.

SET UP: Use the ideal-gas law. Write n in terms of the number of molecules N.

(a) EXECUTE: pV = nRT, n = N/NA so pV = (N/NA)RT

⎛ N ⎞⎛ R ⎞ p = ⎜ ⎟⎜ ⎟T ⎝ V ⎠ N ⎝ A ⎠ ⎛ 80 molecules ⎞⎛ 8 31 . 45 J/mol ⋅ K ⎞ 12 p = (7500 K) ⎜ ⎟⎜ ⎟ = 8.28×10− Pa 6 − 3 23

⎝ 1×10 m ⎠⎝ 6.022×10 molecules/mol ⎠ 17 p 8 2 10− = . ×

atm. This is much lower than the laboratory pressure of 14 9 10− × atm in Exercise 18.24.

(b) EVALUATE: The Lagoon Nebula is a very rarefied low pressure gas. The gas would exert very little

force on an object passing through it. 18.26.

IDENTIFY: pV = nRT = NkT

SET UP: At STP, T = 273 K, 5 p =1.01×10 Pa. 9 N = 6×10 molecules. 9 2 − 3 NkT (6 ×10 molecules)(1.381×10 J/molecule ⋅ K)(273 K) E − XECUTE: 16 3 V = = = 2.24×10 m . 5 p 1.01×10 Pa 3 L = V so 1/3 6 L V 6 1 10− = = . × m.

EVALUATE: This is a small cube.

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Thermal Properties of Matter 18-7 m N 18.27. IDENTIFY: n = = M NA S − ET UP: 23 NA = 6 022 .

×10 molecules/mol. For water, 3 M =18×10 kg/mol. m 1.00 kg EXECUTE: n = = = 55.6 mol. 3 M 18×10− kg/mol 23 25 N = nNA = (55 6

. mol)(6.022×10 molecules/mol) = 3.35×10 molecules.

EVALUATE: Note that we converted M to kg/mol. N 18.28.

IDENTIFY: Use pV = nRT and n = with 1

N = to calculate the volume V occupied by 1 molecule. NA

The length l of the side of the cube with volume V is given by 3 V = l . SET UP: T = 27 C ° = 300 K. 5 p =1.00 atm =1 0 . 13×10 Pa. 8 R = .314 J/mol ⋅ K. 23 NA = 6 022 . ×10 molecules/mol.

The diameter of a typical molecule is about 10 10− m. 9 0 3 nm 0 3 10− . = . × m. N

EXECUTE: (a) pV = nRT and n = gives NA NRT (1 0 . 0)(8.314 J/mol⋅ K)(300 K) 26 − 3 V = = = 4 0 . 9 ×10 m . 1/ 3 9 l V 3 45 10− = = . × m. 23 5

NA p (6.022 ×10 molecules/mol)(1.013 ×10 Pa)

(b) The distance in part (a) is about 10 times the diameter of a typical molecule.

(c) The spacing is about 10 times the spacing of atoms in solids.

EVALUATE: There is space between molecules in a gas whereas in a solid the atoms are closely packed together. 18.29.

(a) IDENTIFY and SET UP: Use the density and the mass of 5.00 mol to calculate the volume. ρ = m/V

implies V = m/ρ, where m = tot

m , the mass of 5.00 mol of water. E − XECUTE: 3 tot m

= nM = (5.00 mol)(18.0×10 kg/mol) = 0.0900 kg m 0.0900 kg Then 5 − 3 V = = = 9 0 . 0×10 m 3 ρ 1000 kg/m (b) One mole contains 23

NA = 6.022×10 molecules, so the volume occupied by one molecule is 5 − 3 9 0 . 0×10 m /mol 29 − 3 = 2.989×10 m /molecule 23 (5.00 mol)(6 022 . ×10 molecules/mol) 3

V = a , where a is the length of each side of the cube occupied by a molecule. 3 2 − 9 3 a = 2.989 ×10 m , so 10 a 3 1 10− = . × m. (c) E −

VALUATE: Atoms and molecules are on the order of 10 10

m in diameter, in agreement with the above estimates. 3RT 18.30. IDENTIFY: 3

Kav = kT. v = . 2 rms M

SET UP: M Ne = 20.180 g/mol, MKr = 83 80

. g/mol and MRn = 222 g/mol. EXECUTE: (a) 3

Kav = kT depends only on the temperature so it is the same for each species of atom in 2 the mixture. v M 83.80 g/mol v M 222 g/mol (b) rms,Ne Kr = = = 2 0 . 4. rms,Ne Rn = = = 3.32. r v ms,Kr M Ne 20.18 g/mol rm v s,Rn M Ne 20 18 . g/mol rms v ,Kr MRn 222 g/mol = = =1 6 . 3. rms v ,Rn MKr 83.80 g/mol

EVALUATE: The average kinetic energies are the same. The gas atoms with smaller mass have larger v rms.

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. 18-8 Chapter 18 3RT 18.31.

IDENTIFY and SET UP: rm v s = . M EXECUTE: (a) rm

v s is different for the two different isotopes, so the 235 isotope diffuses more rapidly. v M 0.352 kg/mol (b) rms,235 238 = = =1.004. rm v s,238 M235 0.349 kg/mol EVALUATE: The rms v

values each depend on T but their ratio is independent of T. 18.32.

IDENTIFY and SET UP: With the multiplicity of each score denoted by , i

n the average score is ⎛ 1/2 1 ⎞ ⎡⎛ ⎞ ⎤ ∑ 1 n x ⎜ ⎟ and the rms score is 2 ∑ n x . ⎢⎜ ⎟ ⎝150 i i ⎠ 150 i i ⎥ ⎝ ⎠ ⎣ ⎦ EXECUTE: (a) 54.6 (b) 61.1

EVALUATE: The rms score is higher than the average score since the rms calculation gives more weight to the higher scores. N m 18.33. IDENTIFY: tot pV = nRT = RT = RT. NA M

SET UP: We know that V = V and that A B A T > B T .

EXECUTE: (a) p = nRT/V ; we don’t know n for each box, so either pressure could be higher. ⎛ N ⎞ pVN (b) pV = ⎜ ⎟ RT so A N =

, where N is Avogadro’s number. We don’t know how the pressures N A ⎝ A ⎠ RT

compare, so either N could be larger. (c) pV = ( to

m t/M )RT. We don’t know the mass of the gas in each box, so they could contain the same gas or different gases. (d) 1 2 3

m(v )av = kT. T > T and the average kinetic energy per molecule depends only on T, so the 2 2 A B

statement must be true. (e) rm

v s = 3kT/m. We don’t know anything about the masses of the atoms of the gas in each box, so

either set of molecules could have a larger rm v s.

EVALUATE: Only statement (d) must be true. We need more information in order to determine whether

the other statements are true or false. 18.34.

IDENTIFY: We can relate the temperature to the rms speed and the temperature to the pressure using the

ideal gas law. The target variable is the pressure. 3RT SET UP: rm v s =

and pV = nRT, where n = m/M. M 3RT EXECUTE: Use rms v to calculate T: rm v s = so M 2 3 − 2 rm

Mv s (28.014×10 kg/mol)(182 m/s) nRT T = =

= 37.20 K. The ideal gas law gives p = . 3R 3(8.314 J/mol ⋅ K) V 3 m 0.226 ×10− kg 3 n = =

= 8.067 ×10− mol. Solving for p gives 3 M 28.014 ×10− kg/mol 3

(8.067 ×10− mol)(8.314 J/mol ⋅ K)(37.20 K) 3 p = =1.69×10 Pa. 3 − 3 1.48×10 m

EVALUATE: This pressure is around 1% of atmospheric pressure, which is not unreasonable since we

have only around 1% of a mole of gas. 3kT 18.35. IDENTIFY: rms v = m

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Thermal Properties of Matter 18-9 S − − −

ET UP: The mass of a deuteron is 27 27 27 m = p m + n m =1 673 . ×10 kg +1 6 . 75×10 kg = 3 3 . 5×10 kg. 8 c = 3 0 . 0×10 m/s. 23 k 1 381 10− = . × J/molecule ⋅ K. 23 − 6 3(1 3

. 81×10 J/molecule⋅ K)(300×10 K) v E − XECUTE: (a) 6 rms rm v s = =1 9 . 3×10 m/s. 3 = 6.43×10 . 27 3.35×10− kg c −27 ⎛ m ⎛ ⎞ 3 3 . 5×10 kg ⎞ (b) 2 7 2 10 T = ( ⎜ ⎟ rms v ) = ⎜ ⎟(3 0 . ×1 0 m/s) = 7.3×1 0 K. ⎜ 23 ⎝ 3k ⎠

3(1 381 10− J/molecule K) ⎟ ⎝ . × ⋅ ⎠

EVALUATE: Even at very high temperatures and for this light nucleus, rms v

is a small fraction of the speed of light. 3RT n p 18.36. IDENTIFY: rm v s =

, where T is in kelvins. pV = nRT gives = . M V RT S −

ET UP: R = 8.314 J/mol ⋅ K. 3 M = 44 0 . ×10 kg/mol. 3(8 3 . 14 J/mol⋅ K)(273.15 K)

EXECUTE: (a) For T = 0 0 . C ° = 273 15 . K, rm v s = = 393 m/s. For 3 44 0 . ×10− kg/mol T = 1 − 00.0 C ° =173 K, rm

v s = 313 m/s. The range of speeds is 393 m/s to 313 m/s. n 650 Pa

(b) For T = 273 15 . K, 3 = = 0 2

. 86 mol/m . For T =173 15 . K, V (8 3 . 14 J/mol ⋅ K)(273 1 . 5 K) n 3 = 0 4

. 52 mol/m . The range of densities is 3 0 2 . 86 mol/m to 3 0.452 mol/m . V

EVALUATE: When the temperature decreases the rms speed decreases and the density increases. 18.37.

IDENTIFY and SET UP: Apply the analysis of Section 18.3. E − − XECUTE: (a) 1 2 3 3 23 21

m(v )av = kT = (1.38×10 J/molecule ⋅ K)(300 K) = 6 2 . 1×10 J 2 2 2

(b) We need the mass m of one molecule: 3 M 32 0 . ×10− kg/mol 26 m = = = 5.314×10− kg/molecule 23

NA 6.022×10 molecules/mol Then 1 2 2 − 1 m(v )av = 6 2

. 1×10 J (from part (a)) gives 2 21 − 21 − 2 2(6.21×10 J) 2(6 2 . 1×10 J) 5 2 2 (v )av = = = 2 3 . 4×10 m /s 26 m 5.314×10− kg (c) 2 4 2 2 rm

v s = (v )rms = 2.34×10 m /s = 484 m/s (d) 26 23 p m rm v − − = s = (5.314 ×10 kg)(484 m/s) = 2.57 ×10 kg ⋅ m/s 0.20 m 0 2 . 0 m

(e) Time between collisions with one wall is 4 t = = = 4.13×10− s rms v 484 m/s G

In a collision v changes direction, so 23 − 2 − 3 Δp = 2m rms v = 2(2 5

. 7×10 kg ⋅ m/s) = 5.14×10 kg ⋅ m/s dp 23 p Δ 5.14×10− kg ⋅ m/s F = so 19 F = = =1.24×10− N dt av 4 t Δ 4.13×10− s (f) 19 − 2 1 − 7 pressure = F/A = 1 2 . 4×10 N/(0.10 m) =1.24×10 Pa (due to one molecule) (g) 5 pressure =1 atm =1 0 . 13×10 Pa Number of molecules needed is 5 1 − 7 21 1 0

. 13×10 Pa/(1.24×10 Pa/molecule) = 8.17×10 molecules 5 3 pV (1 0 . 13×10 Pa)(0 1 . 0 m)

(h) pV = NkT (Eq. 18.18), so 22 N = = = 2.45×10 molecules 23 kT (1 3

. 81×10− J/molecule⋅ K)(300 K)

(i) From the factor of 1 in 2 1 2 (v ) = (v ) . 3 x av av 3

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. 18-10 Chapter 18

EVALUATE: This exercise shows that the pressure exerted by a gas arises from collisions of the molecules of the gas with the walls. 18.38.

IDENTIFY: Apply Eq. (18.22) and calculate λ. S − − − ET UP: 5 1 atm =1 013 . ×10 Pa, so 8 p = 3 5 . 5×10 Pa. 10 r = 2 0 . ×10 m and 23 k =1 3 . 8×10 J/K. 23 kT (1 3 . 8×10− J/K)(300 K) EXECUTE: 5 λ = = =1 6 . ×10 m 2 1 − 0 2 8 4π 2r p 4π 2(2 0 . ×10 m) (3 5 . 5×10− Pa)

EVALUATE: At this very low pressure the mean free path is very large. If v = 484 m/s, as in Example 18.8, λ

then tmean = = 330 s. Collisions are infrequent. v

18.39. IDENTIFY and SET UP: Use equal rms v

to relate T and M for the two gases. rms v

= 3RT/M (Eq. 18.19), so 2rm

v s/3R = T/M, where T must be in kelvins. Same rm

v s so same T/M for the two gases and N T /M N = H T /MH . 2 2 2 2 ⎛ M ⎞ ⎛ 28.014 g/mol ⎞ E N XECUTE: 2 3 N T = H T ⎜ ⎟ = ((20 + 273)K)⎜ ⎟ = 4 071 . ×10 K 2 2 ⎜ M ⎟ H ⎝ ⎠ ⎝ 2 0 . 16 g/mol ⎠ 2 N T = (4071− 273) C ° = 3800 C ° 2

EVALUATE: A N2 molecule has more mass so N2 gas must be at a higher temperature to have the same rm v s. 3kT 18.40. IDENTIFY: rm v s = . m S − ET UP: 23 k =1 3 . 81×10 J/molecule⋅ K. 23 3(1 3

. 81×10− J/molecule ⋅ K)(300 K) E − XECUTE: (a) 3 rm v s = = 6.44×10 m/s = 6 4 . 4 mm/s 16 3.00×10− kg

EVALUATE: (b) No. The rms speed depends on the average kinetic energy of the particles. At this T, H2

molecules would have larger rms v

than the typical air molecules but would have the same average kinetic

energy and the average kinetic energy of the smoke particles would be the same.

18.41. IDENTIFY: Use Eq. (18.24), applied to a finite temperature change. SET UP: = 5 /2 V C R for a diatomic ideal gas and = 3 /2 V C R for a monatomic ideal gas.

EXECUTE: (a) Q = nC T

Δ = n(5 R ΔT. 5 V

Q = (2.5 mol)( )(8.3145 J/mol⋅ K)(50.0 K) = 2600 J. 2 ) 2 (b) 3

Q = nC ΔT = n( R) T Δ . 3 V

Q = (2.5 mol)( )(8.3145 J/mol⋅ K)(50.0 K) = 1560 J. 2 2

EVALUATE: More heat is required for the diatomic gas; not all the heat that goes into the gas appears as

translational kinetic energy, some goes into energy of the internal motion of the molecules (rotations). 18.42.

IDENTIFY: The heat Q added is related to the temperature increase ΔT by Q = nC T Δ . V

SET UP: For ideal H2 (a diatomic gas), ,H = 5/2 , V C

R and for ideal Ne (a monatomic gas), 2 ,Ne = 3/2 . V C R Q EXECUTE: C T Δ = = constant, V so C T Δ = C T Δ n ,H H ,Ne Ne. V V 2 2 ⎛ V C ,H ⎞ ⎛ 5/2 R ⎞ 2 Δ Ne T = ⎜ ⎟Δ H T = (2.50 C ) ⎜ ⎟ ° = 4.17 C° = 4 .17 Κ ⎜ ⎟ . 2 V C ,Ne ⎝ 3/2 R ⎠ ⎝ ⎠

EVALUATE: The same amount of heat causes a smaller temperature increase for H2 since some of the

energy input goes into the internal degrees of freedom. 18.43.

IDENTIFY: C = Mc, where C is the molar heat capacity and c is the specific heat capacity. m pV = nRT = RT. M

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Thermal Properties of Matter 18-11 SET UP: 3 M −

N = 2(14.007 g/mol) = 28.014 ×10 kg/mol. For water, w

c = 4190 J/kg ⋅ K. For N2, 2 20 76 J/mol K. V C = . ⋅ C 20 76 . J/mol ⋅ K c EXECUTE: (a) c w N = = = 741 J/kg ⋅ K. = 5.65; w

c is over five time larger. 2 3 M 28 01 . 4×10− kg/mol cN2 (b) To warm the water, 4 Q = mcw T Δ = (1 0

. 0 kg)(4190 J/mol ⋅ K)(10.0 K) = 4 1 . 9×10 J. For air, 4 Q 4.19×10 J m = = = 5.65 kg. cN T Δ (741 J/kg ⋅ K)(10.0 K) 2 mRT (5 6 . 5 kg)(8 3 . 14 J/mol⋅ K)(293 K) 3 V = = = 4.85 m . 3 − 5 Mp

(28.014×10 kg/mol)(1.013×10 Pa)

EVALUATE: c is smaller for N2, so less heat is needed for 1.0 kg of N2 than for 1.0 kg of water. 18.44.

(a) IDENTIFY and SET UP: 1 R contribution to 2 V

C for each degree of freedom. The molar heat capacity

C is related to the specific heat capacity c by C = Mc. EXECUTE:

= 6(1 = 3 = 3(8 3.145 J/mol⋅K) = 24 9. J/mol⋅K V C R R

. The specific heat capacity is 2 ) 3 c C /M (24 9 J/mol K)/(18 0 10− = = . ⋅ . × kg/mol) =1380 J/kg ⋅ K V V .

(b) For water vapor the specific heat capacity is c = 2000 J/kg ⋅ K. The molar heat capacity is 3 C Mc (18 0 10− = = . ×

kg/mol)(2000 J/kg ⋅ K) = 36.0 J/mol ⋅ K.

EVALUATE: The difference is 36.0 J/mol ⋅ K − 24 9 . J/mol ⋅ K =11 1

. J/mol ⋅ K, which is about 2.7(1 R ; 2 )

the vibrational degrees of freedom make a significant contribution. 18.45. IDENTIFY: = 3 V C R gives V

C in units of J/mol ⋅ K. The atomic mass M gives the mass of one mole. SET UP: For aluminum, 3

M = 26.982 ×102 kg/mol. 24 9 . J/mol⋅ K

EXECUTE: (a) = 3 = 24.9 J/mol ⋅ K. V C R = = 923 J/kg ⋅ K. V c 3 26.982 ×102 kg/mol

(b) Table 17.3 gives 910 J/kg ⋅ K. The value from Eq. (18.28) is too large by about 1.4%.

EVALUATE: As shown in Figure 18.21 in the textbook, CV approaches the value 3R as the temperature

increases. The values in Table 17.3 are at room temperature and therefore are somewhat smaller than 3R. 18.46.

IDENTIFY: Table 18.2 gives the value of v/ rms v

for which 94.7% of the molecules have a smaller value of 3RT v/ rm v s. rms v = . M S − ET UP: For N2, 3 M = 28 0 . ×10 kg/mol. v/ rms v =1 6 . 0. v 3RT EXECUTE: rms v = = , so the temperature is 1.60 M 2 3 Mv (28.0×10− kg/mol) 2 4 − 2 2 2 T = =

v = (4.385×10 K ⋅s /m )v . 2 2 3(1 6 . 0) R 3(1.60) (8 3 . 145 J/mol ⋅ K) (a) 4 − 2 2 2 T = (4 38

. 5×10 K ⋅s /m )(1500 m/s) = 987 K (b) 4 − 2 2 2 T = (4 3

. 85×10 K ⋅s /m )(1000 m/s) = 438 K (c) 4 − 2 2 2

T = (4.385 ×10 K ⋅s /m )(500 m/s) = 110 K

EVALUATE: As T decreases the distribution of molecular speeds shifts to lower values. 18.47.

IDENTIFY: Apply Eqs. (18.34), (18.35) and (18.36). k / R N R S − ET UP: Note that A = = . 3 M = 44 0 . ×10 kg/mol. m / M NA M E − XECUTE: (a) 3 2 mp v = 2(8 3

. 145 J/mol ⋅ K)(300 K)/(44 0 . ×10 kg/mol) = 3 37 . ×10 m/s.

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. 18-12 Chapter 18 (b) 3 − 2 av

v = 8(8.3145 J/mol ⋅ K)(300 K)/(π (44 0

. ×10 kg/mol)) = 3.80×10 m/s. (c) 3 − 2 rms v

= 3(8.3145 J/mol⋅ K)(300 K)/(44 0

. ×10 kg/mol) = 4.12×10 m/s.

EVALUATE: The average speed is greater than the most probable speed and the rms speed is greater than the average speed. 3/2 8π ⎛ m ⎞ 18.48.

IDENTIFY and SET UP: Eq. (18.33): 2⑀/ f (v) kT = ⑀e ⎜ ⎟ m ⎝ 2πkT ⎠ df

At the maximum of f (⑀), = 0. d⑀ 3/2 df 8π ⎛ m ⎞ d E − XECUTE: ⑀/ = ( kT ⑀e ) ⎜ ⎟ = 0 d⑀ m ⎝ 2πkT ⎠ d⑀ d This requires that −⑀/ ( kT ⑀e ) = 0. d⑀ −⑀/kT −⑀/ − (⑀/ ) kT e kT e = 0 ⑀/ (1 ⑀/ ) kT kT e− − = 0

This requires that 1− ⑀/kT = 0 so ⑀ = kT, as was to be shown. And then since 1 2 ⑀ = mv , this gives 2 1 2 mp mv = kT and v =

kT m , which is Eq. (18.34). 2 mp 2 / EVALUATE: 3 rm v s = m v p. The average of 2

v gives more weight to larger v. 2 18.49.

IDENTIFY: Refer to the phase diagram in Figure 18.24 in the textbook.

SET UP: For water the triple-point pressure is 610 Pa and the critical-point pressure is 7 2.212×10 Pa.

EXECUTE: (a) To observe a solid to liquid (melting) phase transition the pressure must be greater than the triple-point pressure, so 1

p = 610 Pa. For p < 1

p the solid to vapor (sublimation) phase transition is observed.

(b) No liquid to vapor (boiling) phase transition is observed if the pressure is greater than the critical-point pressure. 7 2 p = 2 2 . 12 ×10 Pa. For 1 p < p < 2

p the sequence of phase transitions are solid to liquid and then liquid to vapor.

EVALUATE: Normal atmospheric pressure is approximately 5 1 0

. ×10 Pa, so the solid to liquid to vapor

sequence of phase transitions is normally observed when the material is water. 18.50.

IDENTIFY and SET UP: If the temperature at altitude y is below the freezing point only cirrus clouds can form. Use T = 0

T −α y to find the y that gives T = 0.0 C ° . T − T . ° − . ° EXECUTE: 0 15 0 C 0 0 C y = = = 2.5 km α 6 0 . C°/km

EVALUATE: The solid-liquid phase transition occurs at 0°C only for 5

p =1.01×10 Pa. Use the results of

Example 18.4 to estimate the pressure at an altitude of 2.5 km. Mg( y y )/ 2 1 RT 2 p 1 p e − = Mg( y2 − 1 y )/RT =1 1

. 0(2500 m/8863 m) = 0.310 (using the calculation in Example 18.4) Then 5 0 31 5 2 p (1 01 10 Pa)e− . = . × = 0.74×10 Pa.

This pressure is well above the triple point pressure for water. Figure 18.24 in the textbook shows that the

fusion curve has large slope and it takes a large change in pressure to change the phase transition

temperature very much. Using 0.0°C introduces little error. 18.51.

IDENTIFY: Figure 18.24 in the textbook shows that there is no liquid phase below the triple point pressure.

SET UP: Table 18.3 gives the triple point pressure to be 610 Pa for water and 5 5.17 ×10 Pa for CO2.

EXECUTE: The atmospheric pressure is below the triple point pressure of water, and there can be no

liquid water on Mars. The same holds true for CO2.

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Thermal Properties of Matter 18-13 EVALUATE: On earth 5 at

p m =1×10 Pa, so on the surface of the earth there can be liquid water but not liquid CO2. 18.52.

IDENTIFY: The ideal gas law will tell us the number of moles of gas in the room, which we can use to find the number of molecules.

SET UP: pV = nRT, N = nNA, and m = nM. EXECUTE: (a) 27.0 T = C ° + 273 = 300 K. 5 p =1.013×10 Pa. 5 3 pV (1.013×10 Pa)(216 m ) n = = = 8773 mol. RT (8.314 J/mol ⋅ K)(300 K) 23 27

N = nNA = (8773 mol)(6.022×10 molecules/mol) = 5.28×10 molecules. (b) 3 3 6 − 3 8 3

V = (216 m )(1 cm /10 m ) = 2.16 ×10 cm . The particle density is 27 5.28×10 molecules 19 3 = 2.45×10 molecules/cm . 8 3 2.16×10 cm (c) 3 m nM (8773 mol)(28.014 10− = = × kg/mol) = 246 kg.

EVALUATE: A cubic centimeter of air (about the size of a sugar cube) contains around 1019 molecules,

and the air in the room weighs about 500 lb! 18.53.

IDENTIFY: We can model the atmosphere as a fluid of constant density, so the pressure depends on the

depth in the fluid, as we saw in Section 12.2.

SET UP: The pressure difference between two points in a fluid is Δp = ρgh, where h is the difference in height of two points. EXECUTE: (a) 3 2 4

Δp = ρgh = (1.2 kg/m )(9.80 m/s )(1000 m) = 1.18 ×10 Pa.

(b) At the bottom of the mountain, 5

p = 1.013 × 10 Pa. At the top, 4 p = 8.95 × 10 Pa. 5 ⎛ p ⎞ ⎛1.013 ×10 Pa ⎞

pV = nRT = constant so b b p b V = pt t V and t V = b V ⎜ ⎟ = (0.50 L)⎜ ⎟ = 0.566 L. ⎜ 4 p ⎟ ⎝ t ⎠ 8.95 ⎝ ×10 Pa ⎠

EVALUATE: The pressure variation with altitude is affected by changes in air density and temperature and

we have neglected those effects. The pressure decreases with altitude and the volume increases. You may

have noticed this effect: bags of potato chips “puff up” when taken to the top of a mountain.

18.54. IDENTIFY: As the pressure on the bubble changes, its volume will change. As we saw in Section 12.2, the

pressure in a fluid depends on the depth.

SET UP: The pressure at depth h in a fluid is p = 0 p + ρg , h where 0

p is the pressure at the surface. 5 0 p = a

p ir =1.013×10 Pa. The density of water is 3 ρ = 1000 kg/m . EXECUTE: 5 3 2 5 1 p = 0

p + ρgh =1.013 × 10 Pa + (1000 kg/m )(9.80 m/s )(25 m) = 3.463 × 10 Pa. 5 2 p = a p ir =1.013 ×10 Pa. 3 1

V =1.0 mm . n, R and T are constant so pV = nRT = constant. 1 p 1 V = 2 p 2 V 5 ⎛ p ⎞ ⎛ 3.463 ×10 Pa ⎞ and 1 3 3 2 V = 1 V ⎜ ⎟ = (1.0 mm )⎜ ⎟ = 3.4 mm . ⎜ 5 ⎟ ⎝ 2 p ⎠ 1.013 ⎝ ×10 Pa ⎠

EVALUATE: This is a large change and would have serious effects.

18.55. IDENTIFY: The buoyant force on the balloon must be equal to the weight of the load plus the weight of the gas. F

SET UP: The buoyant force is B

F = ρairVg. A lift of 290 kg means B − ho

m t = 290 kg, where m is g hot

the mass of hot air in the balloon. m = V ρ . F EXECUTE: B ho m t = ρhotV. − ho

m t = 290 kg gives (ρ − ρ )V = 290 kg. g air hot

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. 18-14 Chapter 18 290 kg 290 kg pM Solving for ρ hot gives 3 3 ρhot = ρair − =1.23 kg/m − = 0.65 kg/m . ρ = . 3 V 500.0 m hot ho RT t pM ρair = . ρ T = ρ T so R hot hot air air ai T r 3 ⎛ ρ ⎞ ⎛ ⎞ air 1.23 kg/m ho T t = a T ir ⎜ ⎟ = (288 K)⎜ ⎟ = 545 K = 272 C ° . ⎜ 3 ρ ⎟ ⎝ hot ⎠ 0.65 kg/m ⎝ ⎠

EVALUATE: This temperature is well above normal air temperatures, so the air in the balloon would need considerable heating. 18.56. IDENTIFY: V Δ = β 0 V T Δ − 0 V k p Δ S − − − − ET UP: For steel, 5 1 β = 3.6×10 K and 12 1 k = 6.25×10 Pa . EXECUTE: 5 1 β − − 0 V T

Δ = (3.6×10 K )(11.0 L)(21 C ) ° = 0.0083 L. 12 − 7 − o kV p

Δ = −(6.25×10 /Pa)(11 L)(2.1×10 Pa) = 0 − 00

. 14 L. The total change in volume is V

Δ = 0.0083 L − 0.0014 L = 0 00 . 69 L. (b) Yes; V

Δ is much less than the original volume of 11.0 L.

EVALUATE: Even for a large pressure increase and a modest temperature increase, the magnitude of the

volume change due to the temperature increase is much larger than that due to the pressure increase. 18.57.

IDENTIFY: We are asked to compare two states. Use the ideal-gas law to obtain m2 in terms of m1 and the

ratio of pressures in the two states. Apply Eq. (18.4) to the initial state to calculate m1.

SET UP: pV = nRT can be written pV = (m/M )RT

T, V, M, R are all constant, so p/m = RT/MV = constant. So 1 p / 1 m = 2 p / 2

m , where m is the mass of the gas in the tank. EXECUTE: 6 5 6 1 p =1.30×10 Pa +1 0 . 1×10 Pa =1 4 . 0×10 Pa 5 5 5 2 p = 2.50×10 Pa +1 0 . 1×10 Pa = 3.51×10 Pa 1 m = 2 2 3 1 p /

VM RT; V = hA = hπ r = (1.00 m)π (0 06 . 0 m) = 0 0 . 1131 m 6 3 3

(1 40 10 Pa)(0 01131 m )(44 1 10− . × . . × kg/mol) 1 m = = 0 2 . 845 kg (8.3145 J/mol ⋅ K)((22 0 . + 273 15 . )K) 5 ⎛ p ⎞ ⎛ 3 5 . 1×10 Pa ⎞ Then 2 2 m = 1 m ⎜ ⎟ = (0.2845 kg)⎜ ⎟ = 0.0713 kg. ⎜ 6 ⎟ ⎝ 1 p ⎠ 1 4 ⎝ . 0×10 Pa ⎠ 2

m is the mass that remains in the tank. The mass that has been used is 1 m − 2 m = 0.2845 kg − 0 0 . 713 kg = 0 213 . kg.

EVALUATE: Note that we have to use absolute pressures. The absolute pressure decreases by a factor of

four and the mass of gas in the tank decreases by a factor of four. 18.58.

IDENTIFY: Apply pV = nRT to the air inside the diving bell. The pressure p at depth y below the surface of the water is p = at p m + ρg . y SET UP: 5 p =1 0 . 13×10 Pa. 30 T = 0.15

K at the surface and T′ = 280 1 . 5 K at the depth of 13.0 m.

EXECUTE: (a) The height h′ of the air column in the diving bell at this depth will be proportional to the

volume, and hence inversely proportional to the pressure and proportional to the Kelvin temperature: p T′ ′ at p m T h′ = h = h . p′ T at p m + ρgy T 5 (1.013×10 Pa) ⎛280 15 . K ⎞ h′ = (2 3 . 0 m) ⎜ ⎟ = 0.26 m. 5 3 2 (1 013 . ×10 Pa) + (1030 kg/m )(9.80 m/s ) (73 0 . m) 300 ⎝ .15 K ⎠

The height of the water inside the diving bell is h − h′ = 2.04 m .

(b) The necessary gauge pressure is the term ρgy from the above calculation, 5 ga p uge = 7.37×10 P a.

EVALUATE: The gauge pressure required in part (b) is about 7 atm.

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Thermal Properties of Matter 18-15 N p 18.59.

IDENTIFY: pV = NkT gives = . V kT S − ET UP: 5 1 atm = 1.013×10 Pa. K T = C T + 273 15 . . 23 k =1 3 . 81×10 J/molecule⋅ K. EXECUTE: (a) C T = K T − 273 15 . = 94 K − 273 15 . = −179 C ° 5 N p (1.5 atm)(1.013×10 Pa/atm) (b) 26 3 = = =1 2 . ×10 molecules/m 23 V kT (1 38

. 1×10− J/molecule⋅ K)(94 K) (c) For the earth, 5

p =1.0 atm =1.013×10 Pa and T = 22 C ° = 295 K. 5 N (1 0 . atm)(1 0 . 13×10 Pa/atm) 25 3 = = 2 5

. ×10 molecules/m . The atmosphere of Titan is about 23 V

(1.381×10− J/molecule ⋅ K)(295 K)

five times denser than earth’s atmosphere.

EVALUATE: Though it is smaller than Earth and has weaker gravity at its surface, Titan can maintain a

dense atmosphere because of the very low temperature of that atmosphere. 18.60.

IDENTIFY: For constant temperature, the variation of pressure with altitude is calculated in Example 18.4 3RT to be Mgy/RT p 0 p e− = . rms v = . M S − ET UP: 2 gEarth = 9 8 . 0 m/s . 460 T = C ° = 733 K. 3 M = 44 0 . g/mol = 44.0×10 kg/mol. 3 − 2 3 Mgy (44 0 . ×10 kg/mol)(0 894 . )(9.80 m/s )(1 00 . ×10 m) EXECUTE: (a) = = 0 0 . 6326. RT (8 3 . 14 J/mol ⋅ K)(733 K) −Mgy/RT 0 − .06326 p = 0 p e = (92 atm)e

= 86 atm. The pressure is 86 earth-atmospheres, or 0.94 Venus- atmospheres. 3RT 3(8.314 J/mol ⋅ K)(733 K) (b) rms v = = = 645 m/s. 3 M 44 0 . ×10− kg/mol rms v

has this value both at the surface and at an altitude of 1.00 km. EVALUATE: rms v

depends only on T and the molar mass of the gas. For Venus compared to earth, the

surface temperature, in kelvins, is nearly a factor of three larger and the molecular mass of the gas in the

atmosphere is only about 50% larger, so rms v

for the Venus atmosphere is larger than it is for the earth’s atmosphere. 18.61.

IDENTIFY: pV = nRT

SET UP: In pV = nRT we must use the absolute pressure. 1 T = 278 K. 1 p = 2.72 atm. 2 T = 318 K. pV p V p V

EXECUTE: n, R constant, so = nR = constant. 1 1 2 2 = and T 1 T 2 T 3 ⎛ ⎞⎛ ⎞ ⎛ . ⎞ 1 V 2 T 0 0150 m ⎛ 318 K ⎞ 2 p = 1 p ⎜ ⎟⎜ ⎟ = (2.72 atm)⎜ ⎟⎜ ⎟ = 2 9 . 4 atm. ⎜ The final gauge pressure is 3 ⎟ ⎝ 2 V ⎠⎝ 1 T ⎠ 0 ⎝ .0159 m ⎝ 278 K ⎠ ⎠

2.94 atm −1.02 atm =1.92 atm.

EVALUATE: Since a ratio is used, pressure can be expressed in atm. But absolute pressures must be used.

The ratio of gauge pressures is not equal to the ratio of absolute pressures.

18.62. IDENTIFY: In part (a), apply pV = nRT to the ethane in the flask. The volume is constant once the m

stopcock is in place. In part (b) apply tot pV =

RT to the ethane at its final temperature and pressure. M S − − ET UP: 3 3 1.50 L =1.50×10 m . 3

M = 30.1×10 kg/mol. Neglect the thermal expansion of the flask. EXECUTE: (a) 5 4 2 p = 1 p ( 2 T / 1

T ) = (1.013×10 Pa)(300 K/490 K) = 6.20×10 Pa. 4 3 − 3 ⎛ p V ⎞

⎛ (6.20×10 Pa)(1.50×10 m ) ⎞ (b) 2 3 − tot m = ⎜ ⎟M = ⎜ ⎟(30.1×10 Kg/mol) =1.12 g. ⎜ ⎟ ⎝ 2 RT (8.3145 J/mol ⎠ ⋅ K)(300 K) ⎝ ⎠

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. 18-16 Chapter 18

EVALUATE: We could also calculate tot m with 5

p =1.013×10 Pa and T = 490 K, and we would obtain

the same result. Originally, before the system was warmed, the mass of ethane in the flask was 5 ⎛1.013×10 Pa ⎞ m = (1.12 g)⎜ ⎟ =1.83 g. ⎜ 4 6.20 10 Pa ⎟ ⎝ × ⎠ 18.63.

(a) IDENTIFY: Consider the gas in one cylinder. Calculate the volume to which this volume of gas

expands when the pressure is decreased from 6 5 6

(1.20×10 Pa +1.01×10 Pa) =1.30 ×10 Pa to 5 1 0

. 1×10 Pa. Apply the ideal-gas law to the two states of the system to obtain an expression for 2 V in terms of 1

V and the ratio of the pressures in the two states.

SET UP: pV = nRT

n, R, T constant implies pV = nRT = constant, so 1 p 1 V = 2 p 2 V . 6 ⎛1.30×10 Pa ⎞ EXECUTE: 3 3 2 V = 1 V ( 1 p / 2 p ) = (1.90 m )⎜ ⎟ = 24.46 m ⎜ 5 1 01 10 Pa ⎟ ⎝ . × ⎠

The number of cylinders required to fill a 3 750 m balloon is 3 3 750 m / 24.46 m = 30 7 . cylinders.

EVALUATE: The ratio of the volume of the balloon to the volume of a cylinder is about 400. Fewer

cylinders than this are required because of the large factor by which the gas is compressed in the cylinders.

(b) IDENTIFY: The upward force on the balloon is given by Archimedes’s principle (Chapter 12):

B = weight of air displaced by balloon = ρairVg. Apply Newton’s second law to the balloon and solve for

the weight of the load that can be supported. Use the ideal-gas equation to find the mass of the gas in the balloon.

SET UP: The free-body diagram for the balloon is given in Figure 18.63.

mgas is the mass of the gas that is inside

the balloon; mL is the mass of the load that is supported by the balloon. EXECUTE: ∑ y F = may B − L m g − g m asg = 0 Figure 18.63 ρ airVg − L m g − g m asg = 0 L m = ρairV − g m as Calculate ga

m s, the mass of hydrogen that occupies 3 750 m at 15°C and 5 p =1.01×10 Pa. pV = nRT = ( ga

m s/M )RT gives 5 3 3

(1 01 10 Pa)(750 m )(2 02 10− . × . × kg/mol) ga m s = pVM/RT = = 63 9 . kg (8.3145 J/mol ⋅ K)(288 K) Then 3 3 L m = (1 23

. kg/m )(750 m ) − 63.9 kg = 859 kg, and the weight that can be supported is 2 L w = L

m g = (859 kg)(9.80 m/s ) = 8420 N. (c) L m = ρairV − g m as gas m

= pVM/RT = (63.9 kg)((4 00 . g/mol)/(2.02 g/mol)) =126 5

. kg (using the results of part (b)). Then 3 3 L m = (1 23

. kg/m )(750 m ) −126.5 kg = 796 kg. 2 L w = L

m g = (796 kg)(9.80 m/s ) = 7800 N.

EVALUATE: A greater weight can be supported when hydrogen is used because its density is less.

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Thermal Properties of Matter 18-17 18.64.

IDENTIFY: The upward force exerted by the gas on the piston must equal the piston’s weight. Use

pV = nRT to calculate the volume of the gas, and from this the height of the column of gas in the cylinder. SET UP: 2

F = pA = pπ r , with 0.100 r = m and 4

p = 0.500 atm = 5.065×10 Pa. For the cylinder, 2 V = π r . h 2 4 2 pπ r (5.065×10 Pa)π (0.100 m) EXECUTE: (a) 2

pπ r = mg and m = = =162 kg. 2 g 9.80 m/s

(b) V = πr2h and V = nRT/p. Combining these equations gives h = nRT/πr2p, which gives

(1.80 mol)(8.314 J/mol ⋅ K)(293.15 K) h = = 276 m. 2 4 π (0.100 m) (5.065×10 Pa)

EVALUATE: The calculation assumes a vacuum ( p = 0) in the tank above the piston. 18.65.

IDENTIFY: Apply Bernoulli’s equation to relate the efflux speed of water out the hose to the height of

water in the tank and the pressure of the air above the water in the tank. Use the ideal-gas equation to relate

the volume of the air in the tank to the pressure of the air.

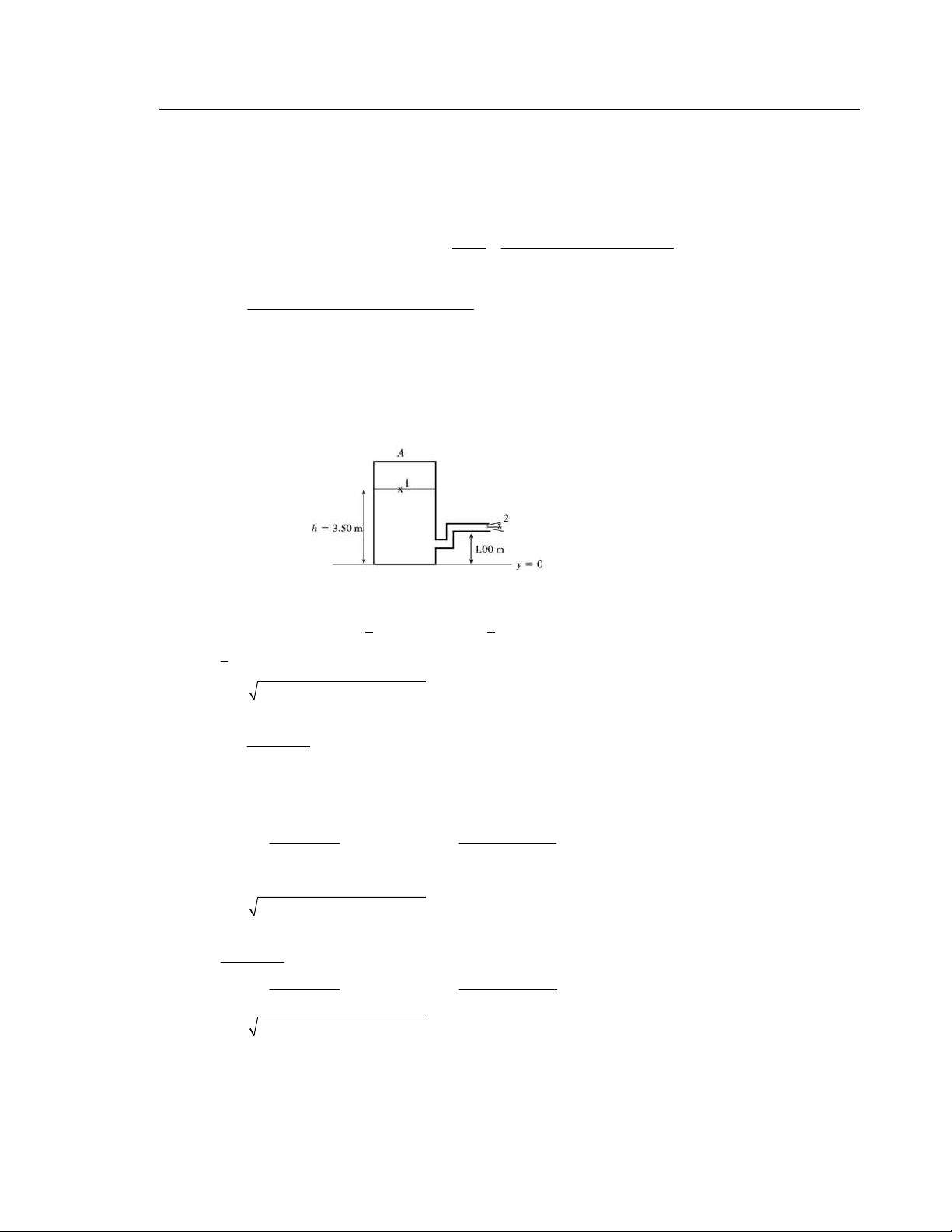

(a) SET UP: Points 1 and 2 are shown in Figure 18.65. 5 1 p = 4 2 . 0×10 Pa 5 2 p = a p ir =1 0 . 0×10 Pa large tank implies 1 v ≈ 0 Figure 18.65 EXECUTE: 1 2 1 2 1 p + ρg 1 y + ρ 1 v = 2 p + ρgy2 + ρ 2 v 2 2 1 2 ρ 2 v = 1 p − 2 p + ρg( 1 y − y2) 2 2 v = (2/ρ)( 1 p − 2 p ) + 2g( 1 y − y2) 2 v = 26 2 . m/s (b) h = 3 0 . 0 m

The volume of the air in the tank increases so its pressure decreases. pV = nRT = constant, so pV = 0 p 0 V ( 0

p is the pressure for 0 h = 3 5

. 0 m and p is the pressure for h = 3.00 m)

p(4.00 m − h)A = 0 p (4 00 . m − 0 h )A ⎛ 4 0 . 0 m − 0 h ⎞ 5 ⎛ 4.00 m − 3.50 m ⎞ 5 p = 0 p ⎜ ⎟ = (4.20×10 Pa)⎜ ⎟ = 2.10×10 Pa ⎝ 4.00 m − h ⎠ ⎝ 4.00 m − 3.00 m ⎠

Repeat the calculation of part (a), but now 5 1 p = 2 1 . 0×10 Pa and 1 y = 3.00 m. 2 v = (2/ρ)( 1 p − 2 p ) + 2g( 1 y − y2) 2 v =16.1 m/s h = 2.00 m ⎛ 4 0 . 0 m − 0 h ⎞ 5 ⎛ 4 0 . 0 m − 3 5 . 0 m ⎞ 5 p = 0 p ⎜ ⎟ = (4.20×10 Pa)⎜ ⎟ =1 05 . ×10 Pa ⎝ 4.00 m − h ⎠ ⎝ 4.00 m − 2.00 m ⎠ 2 v = (2/ρ)( 1 p − 2 p ) + 2g( 1 y − y2) 2 v = 5.44 m/s (c) 2

v = 0 means (2/ ρ)( 1 p − 2 p ) + 2g( 1 y − y2) = 0 1 p − 2 p = −ρg( 1 y − y2)

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. 18-18 Chapter 18 1

y − y2 = h −1 0 . 0 m ⎛ 0.50 m ⎞ 5 ⎛ 0 5 . 0 m ⎞ p = 0 p ⎜ ⎟ = (4.20×10 Pa)⎜ ⎟. This is p so ⎝ 4.00 m − h ⎠ ⎝ 4.00 m − h ⎠ 1, 5 ⎛ 0 5 . 0 m ⎞ 5 2 3 (4.20×10 Pa)⎜ ⎟ −1.00×10 Pa = (9 80

. m/s )(1000 kg/m )(1.00 m − h) ⎝ 4.00 m − h ⎠

(210/ (4.00 − h)) −100 = 9.80 − 9 80

. h, with h in meters.

210 = (4.00 − h)(109.8 − 9.80h) 2

9.80h −149h + 229.2 = 0 and 2

h −15.20h + 23.39 = 0 quadratic formula: 1 h = 15 20 . ± (15 2

. 0) − 4(23.39) = (7.60 ± 5 8 . 6) m 2 ( 2 )

h must be less than 4.00 m, so the only acceptable value is h = 7.60 m − 5.86 m = 1.74 m

EVALUATE: The flow stops when p + ρg( 1

y − y2) equals air pressure. For h =1.74 m, 4 p = 9.3×10 Pa and 4 ρg( 1

y − y2) = 0.7× 10 Pa, so 5 p + ρg( 1 y − y2) =1 0 . ×

10 Pa, which is air pressure. 18.66.

IDENTIFY: Use the ideal gas law to find the number of moles of air taken in with each breath and from

this calculate the number of oxygen molecules taken in. Then find the pressure at an elevation of 2000 m and repeat the calculation.

SET UP: The number of molecules in a mole is 23 NA = 6 022 . ×10 molecules/mol.

R = 0.08206 L ⋅ atm/mol ⋅ K. Example 18.4 shows that the pressure variation with altitude y, when constant temperature is assumed, is Mgy/RT p − 0 p e− = . For air, 3 M = 28.8×10 kg/mol. pV (1 00 . atm)(0.50 L)

EXECUTE: (a) pV = nRT gives n = = = 0.0208 mol. RT

(0.08206 L ⋅ atm/mol ⋅ K)(293.15 K) 23 21

N = (0.210)nNA = (0 21 . 0)(0.0208 mol)(6 0 . 22×10 molecules/mol) = 2 6 . 3×10 molecules. 3 − 2 Mgy (28 8

. ×10 kg/mol)(9.80 m/s )(2000 m) (b) = = 0.2316. RT (8 31 . 4 J/mol⋅ K)(293.15 K) −Mgy/RT 0 − 2 . 316 p = 0 p e = (1 0 . 0 atm)e = 0 7 . 93 atm.

N is proportional to n, which is in turn proportional to p, so ⎛ 0.793 atm ⎞ 21 21 N = (2 6 ⎜

⎟ . 3×10 molecules) = 2.09×10 molecules. ⎝ 1.00 atm ⎠

(c) Less O2 is taken in with each breath at the higher altitude, so the person must take more breaths per minute.

EVALUATE: A given volume of gas contains fewer molecules when the pressure is lowered and the temperature is kept constant. 18.67.

IDENTIFY and SET UP: Apply Eq.(18.2) to find n and then use Avogadro’s number to find the number of molecules.

EXECUTE: Calculate the number of water molecules N. m 50 kg Number of moles: tot 3 n = = = 2 7 . 78×10 mol 3 M 18.0×10− kg/mol 3 23 27 N = nN A = (2 77

. 8×10 mol)(6.022×10 molecules/mol) =1 7 . ×10 molecules

Each water molecule has three atoms, so the number of atoms is 27 27 3(1.7 ×10 ) = 5.1×10 atoms

EVALUATE: We could also use the masses in Example 18.5 to find the mass m of one H2O molecule: 26 m 2 99 10− = . × kg. Then 27 N = to

m t/m =1.7×10 molecules, which checks. N 18.68.

IDENTIFY: pV = nRT =

RT. Deviations will be noticeable when the volume V of a molecule is on the NA

order of 1% of the volume of gas that contains one molecule.

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Thermal Properties of Matter 18-19 4

SET UP: The volume of a sphere of radius r is 3 V = π r . 3 RT

EXECUTE: The volume of gas per molecule is

, and the volume of a molecule is about NA p 4 10 − 3 2 − 9 3 0 V = π (2.0×10 m) = 3.4×10

m . Denoting the ratio of these volumes as f, 3 RT (8 31 . 45 J m / ol ⋅ K)(300 K) 8 p = f = f = (1.2 ×10 Pa) f . 23 29 − 3 NA 0 V (6 02 . 2 ×10 molecules m / o l)(3.4 ×10 m )

“Noticeable deviations” is a subjective term, but f on the order of 1.0% gives a pressure of 6 10 Pa.

EVALUATE: The forces between molecules also cause deviations from ideal-gas behavior. 18.69.

IDENTIFY: Eq. (18.16) says that the average translational kinetic energy of each molecule is equal to 3 kT. 2 3kT rm v s = . m S − ET UP: 23 k =1 3 . 81×10 J/molecule⋅ K. EXECUTE: (a) 1 2

m(v )av depends only on T and both gases have the same T, so both molecules have the 2

same average translational kinetic energy. rms v is proportional to 1/2

m− , so the lighter molecules, A, have the greater rm v s.

(b) The temperature of gas B would need to be raised. T v T T (c) rms = = constant, so A B = . m 3k mA B m 26 ⎛ m ⎞ ⎛ 5.34×10− kg ⎞ B 3 T = ⎜ ⎟T = ⎜

⎟(283.15 K) = 4.53×10 K = 4250 C ° . B A ⎜ 27 m − ⎟ ⎝ A ⎠ 3 ⎝ .34×10 kg ⎠ (d) B

T > TA so the B molecules have greater translational kinetic energy per molecule. 3kT EVALUATE: In 1 2 3

m(v )av = kT and v =

the temperature T must be in kelvins. 2 2 rms m 18.70.

IDENTIFY: The equations derived in the subsection Collisions Between Molecules in Section 18.3 can be

applied to the bees. The average distance a bee travels between collisions is the mean free path, λ. The average dN 1

time between collisions is the mean free time, tmean. The number of collisions per second is = . dt tmean S − ET UP: 3 3 V = (1 2 . 5 m) =1.95 m . 2 r = 0 750 . ×10 m. v =1.10 m/s. 2500. N = 3 V 1.95 m EXECUTE: (a) λ = = = 0.780 m = 78.0 cm 2 2 − 2 4π 2r N 4π 2(0 75 . 0×10 m) (2500) λ 0.780 m

(b) λ = vtmean, so tmean = = = 0.709 s. v 1 1 . 0 m/s dN 1 1 (c) = = =1 4 . 1 collisions/s dt tmean 0.709 s

EVALUATE: The calculation is valid only if the motion of each bee is random. 18.71.

IDENTIFY: The mass of one molecule is the molar mass, M, divided by the number of molecules in a mole, N 1

A. The average translational kinetic energy of a single molecule is 2 3

m(v )av = kT. Use 2 2

pV = NkT to calculate N, the number of molecules. S − − ET UP: 23 k =1 3 . 81×10 J/molecule⋅ K. 3 M = 28 0 . ×10 kg/mol. 295 T = 15 . K. The volume of the balloon is 4 3 3 V = π (0 2 . 50 m) = 0 065 . 4 m . 5 p =1.25 atm = 1 27 . ×10 Pa. 3

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. 18-20 Chapter 18 3 M 28 0 . ×10− kg/mol E − XECUTE: (a) 26 m = = = 4.65×10 kg 23 NA 6 022 . ×10 molecules/mol (b) 1 2 3 3 2 − 3 2 − 1

m(v )av = kT = (1.381×10 J/molecule ⋅ K)(295 1 . 5 K) = 6.11×10 J 2 2 2 5 3 pV (1.27 ×10 Pa)(0.0654 m ) (c) 24 N = = = 2.04×10 molecules 23 kT

(1.381×10− J/molecule ⋅ K)(295.15 K)

(d) The total average translational kinetic energy is N (1 2 m(v ) − av = (2.04 ×10 molecules)(6 1

. 1×10 J/molecule) =1.25×10 J. 2 ) 24 21 4 24 N 2.04×10 molecules

EVALUATE: The number of moles is n = = = 3.39 mol. 23 NA 6 0 . 22×10 molecules/mol 3 3 4 Ktr = nRT = (3 3 . 9 mol)(8 3 . 14 J/mol⋅ K)(295 1

. 5 K) =1.25×10 J, which agrees with our results in part (d). 2 2 18.72.

IDENTIFY: U = mgy. The mass of one molecule is m = / M NA. 3 Kav = kT. 2 SET UP: Let 0

y = at the surface of the earth and h = 400 m. 23

NA = 6.022 ×10 molecules/mol and 23 k 1 38 10− = . × J/K. 15 0 . °C = 288 K. 3 M ⎛ 28.0×10− kg/mol ⎞ E − XECUTE: (a) 2 22 U = mgh = gh = ⎜ ⎟(9 80 . m/s )(400 m) =1 8 . 2×10 J. ⎜ 23 N ⎟ A 6 ⎝ .022×10 molecules/mol ⎠ 22 3 2 ⎛ 1 8 − . × 2 10 J ⎞

(b) Setting U = kT, T = ⎜ ⎟ = 8.80 K. ⎜ 23 2 3 1 38 10− J/K ⎟ ⎝ . × ⎠

EVALUATE: (c) The average kinetic energy at 15.0 C

° is much larger than the increase in gravitational

potential energy, so it is energetically possible for a molecule to rise to this height. But Example 18.8

shows that the mean free path will be very much less than this and a molecule will undergo many collisions

as it rises. These numerous collisions transfer kinetic energy between molecules and make it highly

unlikely that a given molecule can have very much of its translational kinetic energy converted to

gravitational potential energy. 18.73.

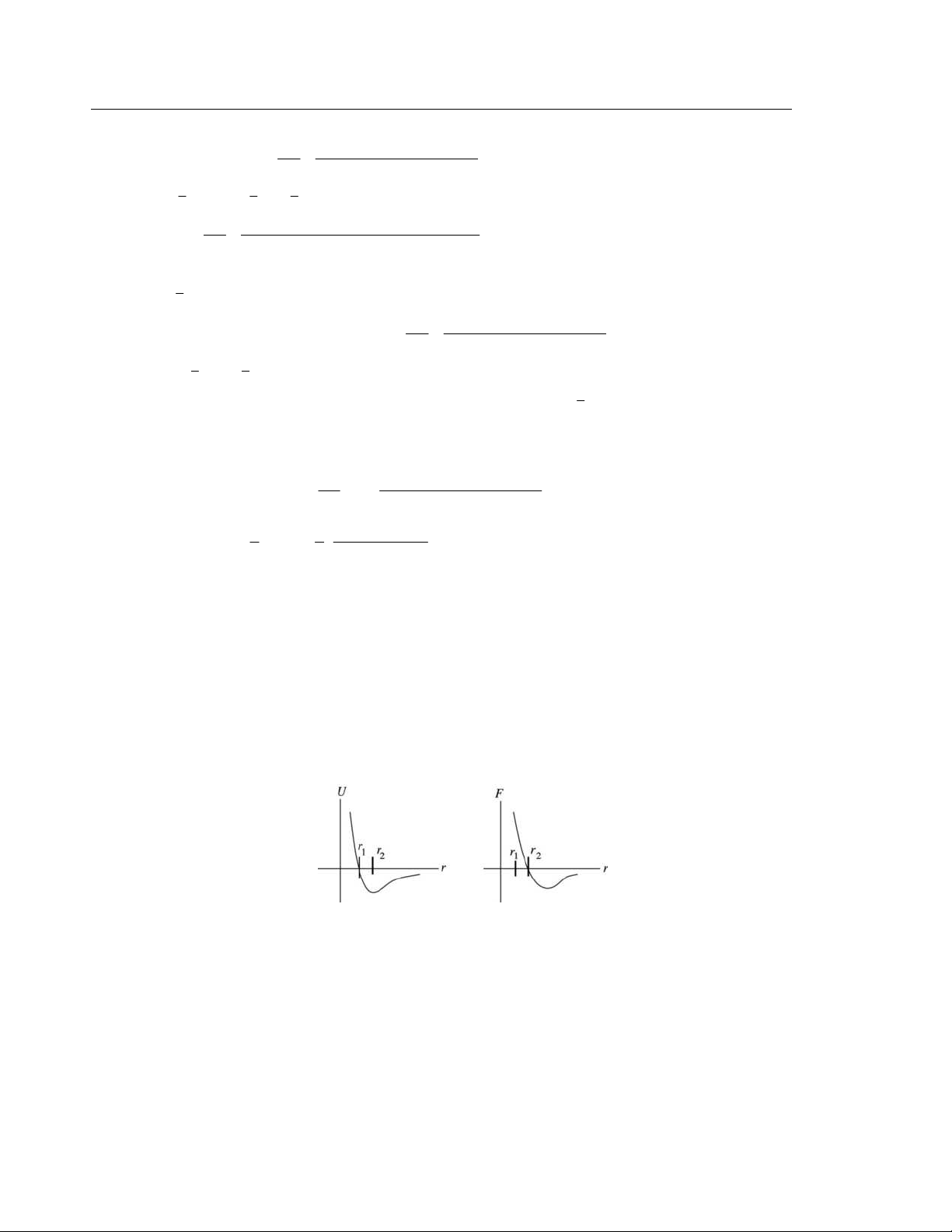

IDENTIFY and SET UP: At equilibrium F (r) = 0. The work done to increase the separation from r2 to ∞

is U (∞) −U ( 2 r ). (a) EXECUTE: 12 6

U (r) = U0[( 0 R /r) − 2( 0 R /r) ] Eq. (14.26): 13 7

F (r) =12(U0/ 0 R )[( 0 R /r) − ( 0

R /r) ]. The graphs are given in Figure 18.73. Figure 18.73

(b) equilibrium requires F = 0; occurs at point 2 r . 2

r is where U is a minimum (stable equilibrium).

(c) U = 0 implies 12 6 [( 0 R /r) 2( 0 R /r) ] = 0 6 ( 1r/ 0 R ) =1/2 and 1/6 1 r = 0 R /(2) F = 0 implies 13 7 [( 0 R /r) − ( 0 R /r) ] = 0 6 ( 2 r / 0 R ) =1 and 2 r = 0 R Then 1/6 1/ − 6 1 r / 2 r = ( 0 R /2 )/ 0 R = 2

© Copyright 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. This material is protected under all copyright laws as they currently exist.

No portion of this material may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher.