Preview text:

THE TOYOTA PRODUCTION SYSTEM RE-CONTEXTUALIZED

(With history, anecdotes and implementation tips) 4thEdition Includes Value Stream Mapping case by Staffan Nöteberg

Jose Berengueres, Ph. D

The Toyota Production System Re-contextualized 4th Edition ISBN 978-1-84753-477-4

Copyright © 2007-2012 by Jose Berengueres. All rights reserved. Revised 4rd English Edition, Dubai October 2012 Contents

1 Industry Framework ................................................................. 11

1.1 Toyota: Growth and efficiency .................................................... 11

1.2 Size Matters ............................................................................... 13

1.3 The consolidation wave of the 90s ............................................. 15

1.4 Organic growth vs. Acquisition ................................................... 18

2 Brief history of Toyota .............................................................. 21

2.1 Origin .......................................................................................... 21

2.2 The Beginnings .......................................................................... 21

2.3 Mommy’s Loom .......................................................................... 24

2.4 From the Loom to the Automobile .............................................. 25

2.5 Taiichi Ohno or the birth of TPS ................................................. 28

3 The Production System ............................................................ 31

3.1 Underlying Principles .................................................................. 31

3.2 Operative Targets ....................................................................... 33

3.3 The difference between “Lean” and “TPS” ................................. 33

3.4 Sociolinguistic barriers ............................................................... 35

3.5 A visit to Denso Academy .......................................................... 37

4 TPS step by step ...................................................................... 41

4.1 Poka-Yoke and Jidouka ............................................................. 41

4.2 Muda - Waste ............................................................................. 45

4.3 Standardization of Work ............................................................. 52

4.4 Visualization ............................................................................... 52

4.5 Itsutsu no Naze .......................................................................... 53

4.6 Heijunka and Push/Pull .............................................................. 55

4.7 Just-in-Time ................................................................................ 56

4.8 Gemba & Genchi Genbutsu ........................................................ 57

4.9 Kanban ....................................................................................... 58

4.10 Andon ....................................................................................... 59

4.11 Multi-product mini-batch ........................................................... 61

4.12 Sense of Crisis .......................................................................... 62

4.13 5S – Kaizen .............................................................................. 63

4.14 How-to Organize a Kaizen committee ...................................... 70

4.15 The P.D.C.A method ................................................................. 74

4.16 How–to A3 Report and Value Stream Mapping ........................ 78

5 Appendix: Fun facts about Japanese carmakers ..................... 81

References .................................................................................. 87 Industry Framework | 11

There is only one way... to be the best,

slogan of Nissan in the roaring 90s 1 Industry Framework

1.1 Toyota: Growth and efficiency

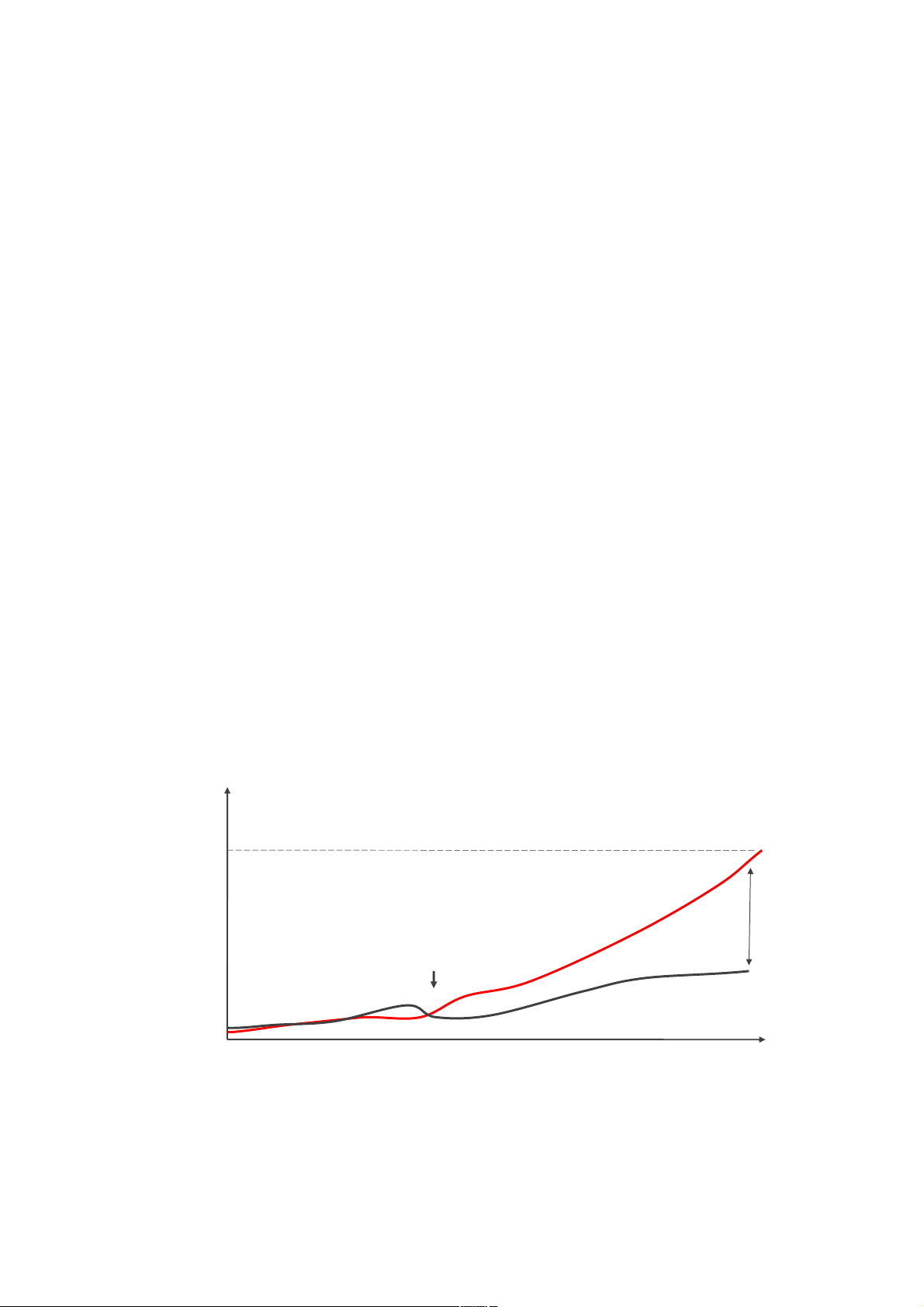

Figure 1 shows the benefit per car sold of two carmakers (Toyota and

Volkswagen). From all the volume manufacturers Toyota is the one that

makes the highest profit and with great distance from the rest of global

manufacturers. It is also the largest company by market capitalization per

car sold (five year average). Where lays the reason of this competitive

advantage? If we ask people at consulting firms, they say that Toyota is

not the most productive manufacturer ever. In 2006 in the key North

American market for instance, Nissan beats Toyota in labour productivity

(18 hours of labour to make a car vs. 22 hours for Toyota) and also in

pre-tax profit per car sold 1500 vs. 1000 EUR. (GM lost 1000 per car sold).

Toyota does not own the most productive plants either. Toyota 1000€ car Sold 1st Oil shock Profit per 331€ VolksWagen* 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

Figure 1 Profit per car sold of Toyota vs. Volkswagen (2005). What is the source

of Toyota’s competitive advantage? 12 | Jose Berengueres

However, on a global scale it is the only one manufacturer that uses its

factories nearest to its full capacity. 96 to 106% compared to a typical

75% industry average. It is also the volume manufacturer that produces the

most reliable cars (Harbour 2006). Consider this, in 2006 for each Toyota

car sold customers encountered 1.06 problems within 90 days of the

purchase. The industry average is 1.24 problems. As for the other

carmakers: Volkswagen rated 1.71. Nissan rated 1.21 (Initial Quality, J.D

Power 2006). What is the key of Toyota’s success? Of all the factors that

could explain Toyota’s growth: (i) labour productivity (ii) capacity utilization (iii) product quality

none of them seems more correlated with Toyota’s progression than

product quality. On the other hand, if we compare quality at Toyota,

Nissan and Volkswagen, (1.06, 1.21 and 1.71) the spread does not seem so

big. It is just 0.65 more problems per every one car sold. 65 per cent points

does not seem a big figure, but Toyota sold 10 million cars last year so

that's 6.5 million problems less to take care of. Taxi of choice

Lets take a look at taxi fleets in free markets such as Abu Dhabi, UAE.

The Toyota Camry is 70% of the total fleet:

Taxi Driver – These cars are driven 24 hours continuously in two

shift drivers. The company provides accommodation for the

drivers. Two drivers are assigned per car. When one driver works

the other sleeps, so the car is always driving. At this rate each

taxi logs 900 km per day, it can produce a daily income of

400-800Dhs (100-200$). Most taxis will reach the 600,000km

mark after two years. After they reach this mark, they are sold or scrapped.

Author – What about the other cars such as the Nissan Sunny or the Hyundai Sonata? Industry Framework | 13

Taxi Driver – Hyundai is not a bad car. It is good for family use,

but only Camry can go up to 600,000 km.

In the end, this tinny quality gap has had a clear effect for Toyota: (i) The hoarding of huge capitals (ii) Sustained growth

Therefore reducing (the causes of) such gap should be a top priority for

any manager that wishes to survive let alone succeed. But, how to close

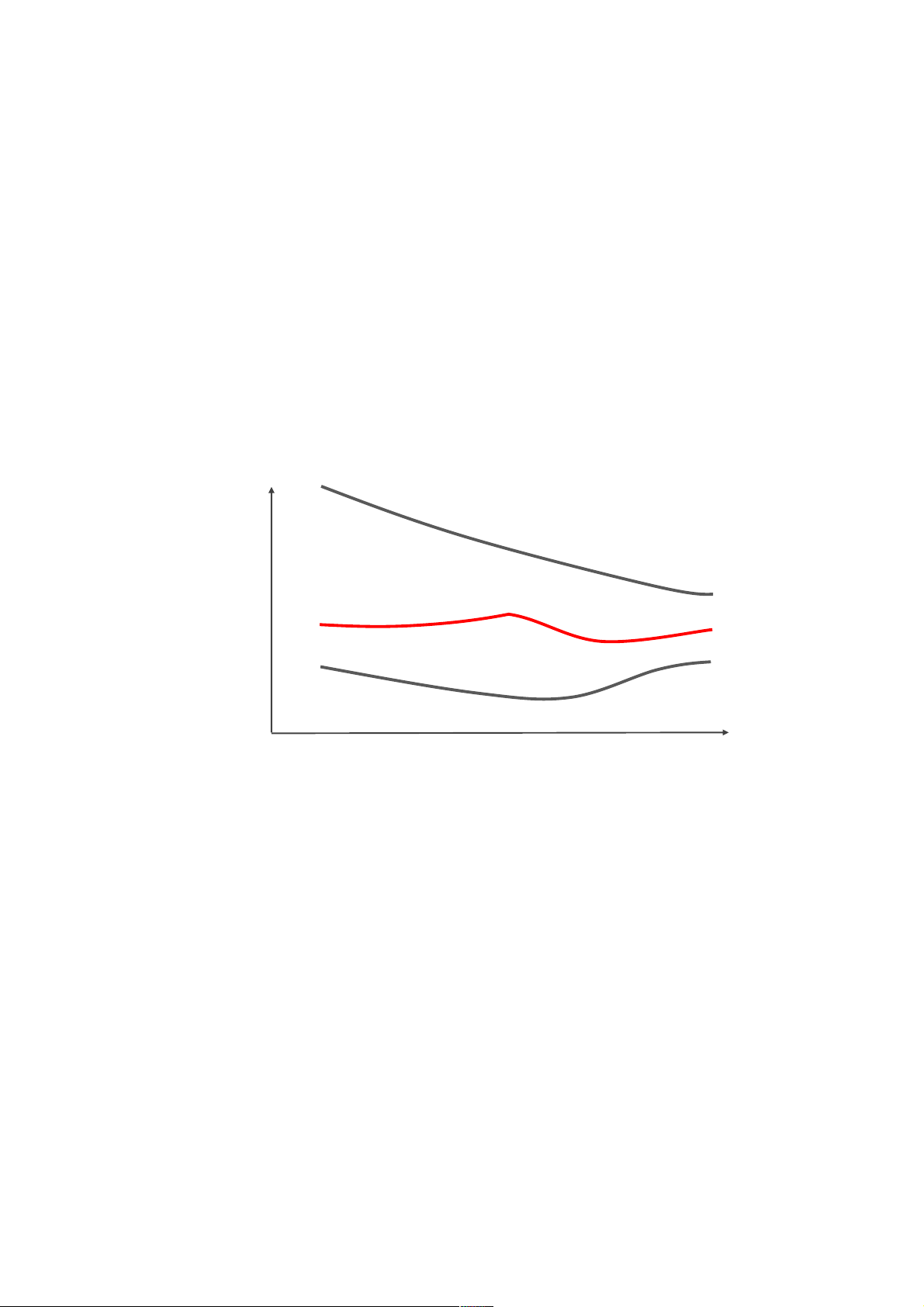

the quality gap? How to be efficient without compromising on quality? 32h icle Veh 24h urs per GM 21.4h Toyota bly Ho 19.2h Nissan Assem 19h 1999 2002 2005

Figure 2 Labour productivity evolution in North America (Harbour 2006).

Toyota is not the most productive maker in manpower terms. 1.2 Size Matters

Once mass-production of a new product commences a law, as precise as

Moore’s law can approximate the cost of producing an additional unit.

According to this law, the cost decreases exponentially not with time but

with the cumulative number of units produced. A way of being more

efficient is gaining size to reach the so-called scale economies. There are two ways of doing that: (i) Organically (ii) Merger and Acquisition 14 | Jose Berengueres

Organic growth refers to the growing of a plant: slow but steady. A

paradigmatic example of organic growth can be found in Inditex S.A of

Spain. The rationale behind most M&A is that the combination of two

entities in a bigger one results in an entity with larger operations and thus

able to undertake bigger economies of scale. That is the idea behind being

the cost leader. In the light of this reasoning an M&A operation is justified

if the future savings due to future scale economies are bigger than the cost

of transaction plus integration.

Are Future Savings larger than acquisition price + integration costs?

As we will see later M&A is a concept with no traction inside the Toyota

philosophy. Nevertheless, this does not mean that at Toyota they ignore

the importance of being big. On the contrary, an illustrative example can

be found in the battle that Toyota and Honda held for the hybrid market

some years ago. You probably remember the Prius: the best selling hybrid

car in history. Maybe the Honda Insight does not sound so familiar. Honda

Insight is also a hybrid car (less popular than the Prius) but that was first

to market. If you see a 1999 Honda Insight on the street you will quickly

realize the reason why it was less popular than the Prius: it is smaller and just two persons can fit in.

Figure 3 Layout of the two-seater Honda Insight of 1999. There was not enough

space for additional seats. Source: Honda/cartype.com.

The reason is that the rear of the Insight hosts hybrid components. Industry Framework | 15

Couldn’t Honda in the 90s develop a hybrid car for four passengers? The

answer is no. Honda (because of it smaller size) did not have enough

resources at that time to develop a specific platform for a larger hybrid.

Faced with the dilemma the Honda engineers had no choice but to reuse

an existing platform (the one of its bestselling compacts). This left no

space... Put in words by a Honda chief engineer:

“I already told (the higher ups) that by using such platform there

would not be enough space for 5 seats, but we already had been

told that there was not enough money to develop a specific

platform…” (Nikkei 2006)

On the other hand, Toyota due to its larger size could afford the risks (and

costs) of designing a Prius from zero including a new brand platform.

Building a hybrid was a direct order from at the time Toyota CEO, the

genial Hiroshi Okuda. The order was given in 1996 to a staff in a rather casual way:

“Well, now you don't have an excuse not to make a hybrid” (Nikkei 2006)

A decade later, the result is clear: Prius won, and the conclusion of the

Insight-Prius battle is that size matters. Every body knows it. In the

following section we will examine how this idea coupled with greed and

fear shaped the industry during the 90s.

1.3 The consolidation wave of the 90s

In the post-war era automobile industry, M&A was a fairly rare

phenomenon until the decade of the 90s when the sector enters a very

active phase believed to start with the acquisition of Rover by BMW. The

operation would later turn sour and would end up in BMW selling Rover.

Nevertheless, a cunning BMW would retain the rights to the Rover-owned

Mini brand and would successfully re-launch it some years later. Since

then, only a select bunch of deals has had positive returns on investment:

The re-purchase by General Motors of Hyundai Motor after the Korean

Won devaluation in 1997. The acquisition by Ford of Mazda by which 16 | Jose Berengueres

Ford through Mark Fields brings to Mazda a much-needed management

expertise that traces its origins to Mr. McNamara’s Whiz Kids. The

agreement between Nissan and Renault by which a “literally” desperate

Nissan, that had just been turned down by Daimler, (in the wake of the

Daimler-Mitsubishi alliance), accepts the management leadership of

Carlos Goshn in management matters (not technology):

“You tell us how to organize ourselves. But please... don’t tell us

how to make a car”. (Magee 2005).

Is Nissan a proud company? The acronym stands for Japanese Productions, in Japanese: Nippon Seisan.

NISSAN = NIP-PON + SEI-SAN

Nissan started producing cars in Yokohama at the same time as Toyota but

that ended up in a very different philosophical silo. Nissan grew out of

agglutinating smaller makers such as Datsun under Japanese government

directions. From the rest of the consolidation wave (read fear) that swept

across Detroit and Western Europe during the 90s few other deals had

positive returns on investment. An iconic example of a failed acquisition is

the takeover of Chrysler by German Daimler. Chrysler, as they say, was

the queen of Detroit in 1998. It had become thanks to the success of the Chrysler voyager:

“Voyager was the first minivan that could hold the bites and

parts of the extended family, dogs etcetera together” (Blue Ocean Strategy, 2005).

Daimler paid 36 billion dollars for it. In 2008 some analysts estimated that

it was worth less than 12 billion. The explanation offered by Liker on this

loss of value is as follows: at the end of the 90s Chrysler had managed to

establish Toyota-style relations with its supplier network. They had

succeeded in replicating what in Toyota they call an extended supplier

network (Liker 2003). This was starting to bear fruits with cars such as the

Chrysler Neon (a car that even sold some units in Europe during the 90s)

and the PT Cruiser (a car that looks like a shoe but that is popular among Industry Framework | 17

consumers because of its usability). However, after the Germans took over

Chrysler they imposed cost cutting drives that destroyed whatever

provider-relations Chrysler had built.

“At the Toyota Head Quarters they were really alarmed by the

progression of Chrysler” (Liker 2007)

Figure 4 More powerful but cheaper than the competition, the 1996 Chrysler

Neon revolutionized the car industry with powerful base engines. An example of

value innovation is shown here: the famous three clips instead of the customary

four helped cut costs at no visible loss for the customer.

On one occasion Toyota did buy one Chrysler Neon car. It was

disassembled in-house. Then it was shown to the press in the following way:

Ah… but look here. This panel is attached with clips! And only three of them.

Years later, the value destruction at Chrysler became apparent and

questioned the long-term logic of the Germanic cost cutting drives. The

lesson here is clear: it is better to treat your suppliers as part of your

family. If you squeeze them too much today, tomorrow they will lack competitive capacity. 18 | Jose Berengueres Teaching

A healthy provider is more useful than a zombie one at Toyota they say:

Treat your suppliers as an extension of your own company

1.4 Organic growth vs. Acquisition

The 90s lesson is that slower organic growth seems to be the only credible

ways to gain scale in order to survive in a globalizing market. It is the way

chosen (willingly or unwillingly) by Honda, BMW and Suzuki.

Additionally, in this framework of global overcapacity (currently

estimated at 75% in 2006) appears Toyota with record profits and its

production system. The visionary book The machine that changed the

world by Womack in 1990 and more recently the bestseller The Toyota

Way (Liker 2003) have decisively contributed to popularize the Toyota

production techniques in the West. All this factors have put Toyota and in

particular its production system in the spotlight. Not only due to financial

reasons but also because its long-term thinking rings a bell with

sustainable thinking. This is a remarkable fact because it is the first time

since Kung Fu made it to Hollywood that a thinking based on Confucian

principles has been so widely studied in West. Never the less, the Toyota

Production System is traditionally absorbed in the West under the names

such as Lean Management or GE’s Black Belt certification system. In fact,

there is no shortage of firms that try to import, copy or adapt the Toyota

Production System (from now on referred as TPS). However, experience

tells us that implementing TPS in the West is no easy task. In fact, it is not

even an easy thing to do in Japan. In spite that, several carmakers have

named its production systems after Toyota: Ford has its own FPS: Ford

Production System. Nissan has its own NPS: Nissan Production System.

Moreover, General Motors has a 50% joint venture with Toyota at the

NUMMI factory in California but for years has been unable to transplant

the experience of NUMMI to the rest of its factories (Liker 2003). At the

end NUMMI was a factory failure. The site is now the main site of Tesla Industry Framework | 19 Motors.

The teaching that we can extract from the 90s is that size does matters, but

there are no shortcuts. In the following chapters we explain the basics of

the TPS: its origins and concepts such as waste (muda) that stem precisely

from the Zen thinking of Less is More.