lOMoARcPSD|44862240

4 ĐỀ IELTS READING THI THẬT 2018

1. Breeding Bittern.........................................................................................................................................3

2. The Origins of Laughter...........................................................................................................................12

3. The Adolescents.......................................................................................................................................22

4. Detection of a meteorite lake....................................................................................................................33

lOMoARcPSD|44862240

lOMoARcPSD|44862240

1. Breeding Bittern

A. Breeding bitterns became extinct in the UK by 1886, but following recolonisation early last

century, numbers rose to a peak of about 70 booming (singing) males in the J950s, falling to fewer than 20

by the 1990s. In the late 1980s, it was clear that the bittern was in trouble, but there was little information

on which to base recovery actions.

B. Bitterns have cryptic plumage and a shy nature, usually remaining hidden withinthe cover of reed

bed vegetation. Our first challenge was to develop standard methods to monitor their numbers. The boom

of the male bittern is its most distinctive feature during the breeding season, and we developed a method to

count them using the sound patterns unique to each individual. This not only allows us to be much more

certain of the number of booming males in the UK, but also enables us to estimate local survival of males

from one year to the next.

C. Our first direct understanding of the habitat needs of breeding bitterns came from comparisons of

reed bed sites that had lost their booming birds with those that retained them. This research showed that

bitterns had been retained in reed beds where the natural process of succession, or drying out, had been

slowed through management. Based on this work; broad recommendations on how to manage and

rehabilitate reed beds for bitterns were made, and funding was provided through the EU Life Fund to

manage 13 sites within the core breeding range. This project though led by the RSPB, involved many other

organisations.

D To refine these recommendations and provide fine-scale, quantitative habitatprescriptions on the

bitterns’preferred feeding habitat, we radio-tracked male bitterns on the RSPB’s Minsmere and Leighton

Moss reserves. This showed clearpreferences for feeding in the wetter reed bed margins, particularly within

the reed bed next to larger open pools. The average home range sizes of the male bitterns we followed

(about 20 hectares) provided a good indication of the area of reed bed needed when managing or creating

habitat for this species. Female bitterns undertake all the incubation and care of the young, so it was

important to understand their needs as well. Over the course of our research, we located 87 bittern nests and

found that female bitterns preferred to nest in areasof continuous vegetation, well, into the reed bed, but

where water was still present during the driest part of the breeding season.

E The success of the habitat prescriptions developed from this research has been spectacular. For

instance, at Minsmere, booming bittern numbers gradually increased from one t0 10 following reedbed

lowering, a management technique designed to halt the drying out process. After a low point of 11

booming males in 1997, bittern numbers in Britain responded to all the habitat management work and

started to increase for the first time since the 1950s.

F The final phase of research involved understanding the diet, survival and ‘dispersal of bittern

chicks. To do this we fittedsmall radio tags to young bittern chicks in the nest, to determine their fate

through to fledging and beyond. Many chicks did not survive to fledging and starvation was found to be the

most likely reason for their demise. The fish prey fed to chicks was dominated by those species penetrating

into the reed edge. So, an important element of recent studies (including a PhD with the University of Hull)

has been the development of recommendations on habitat and water conditions to promote healthy native

fish populations.

G Once in dependent, radio-tagged young bitterns were found to seek out new sitesduring their first

winter; a proportion of these would remain on new sites to breed if the conditions were suitable. A second

lOMoARcPSD|44862240

EU LIFE funded project aims to provide these suitable sites in new areas. A network of 19 sites

developed thr ough this partnership project will secure a more sustainable UK bittern population with

successful breeding outside of the core area, less vulnerable to chance events and sea level rise.

H By 2004, the number of booming malebitterns in the UK had increased to 55, with almost all of

the increase being on those sitesundertaking management based on advice derived from our research.

Although science has been at the core of the bittern story, success has only been achieved through the trust,

hard work and dedication of all the managers, owners and wardens of sites that have implemented, in some

cases very drastic, management to secure the future of this wetland species in the UK. The constructed

bunds and five major sluices (水闸) now control the water level over 82 ha, with a further 50 ha coming

undercontrol in the winter of 2005/06. Reed establishment has principally used natural regeneration or

planted seedlings to provide small core areas that will in time expand to create a bigger reed area. To date

nearly 275,000 seedlings have been planted and reed cover is extensive. Over 3 km of new ditches have

been formed, 3.7 km of existing ditch have been re-profiled and 2.2 km of old meander(former estuarine

features) have been cleaned out.

I Bitterns now regularly winter on the site with some indication that they are staying longer into the

spring. No breeding has yet occurred but a booming male was present in the spring of 2004. A range of

wild flower breed, as well as a good number of reed bed passerines including reed bunting, reed,sedge and

grasshopper warblers. Numbers of wintering shoveler have increased so that the site now holds a UK

important wintering population. Malltraeth Reserve now forms part of the UK network of key sites for

water vole (a UK priority species) and 12 monitoring transects have been established. Otter and brown-hare

occur on the site as does the rare plant, pillwort.

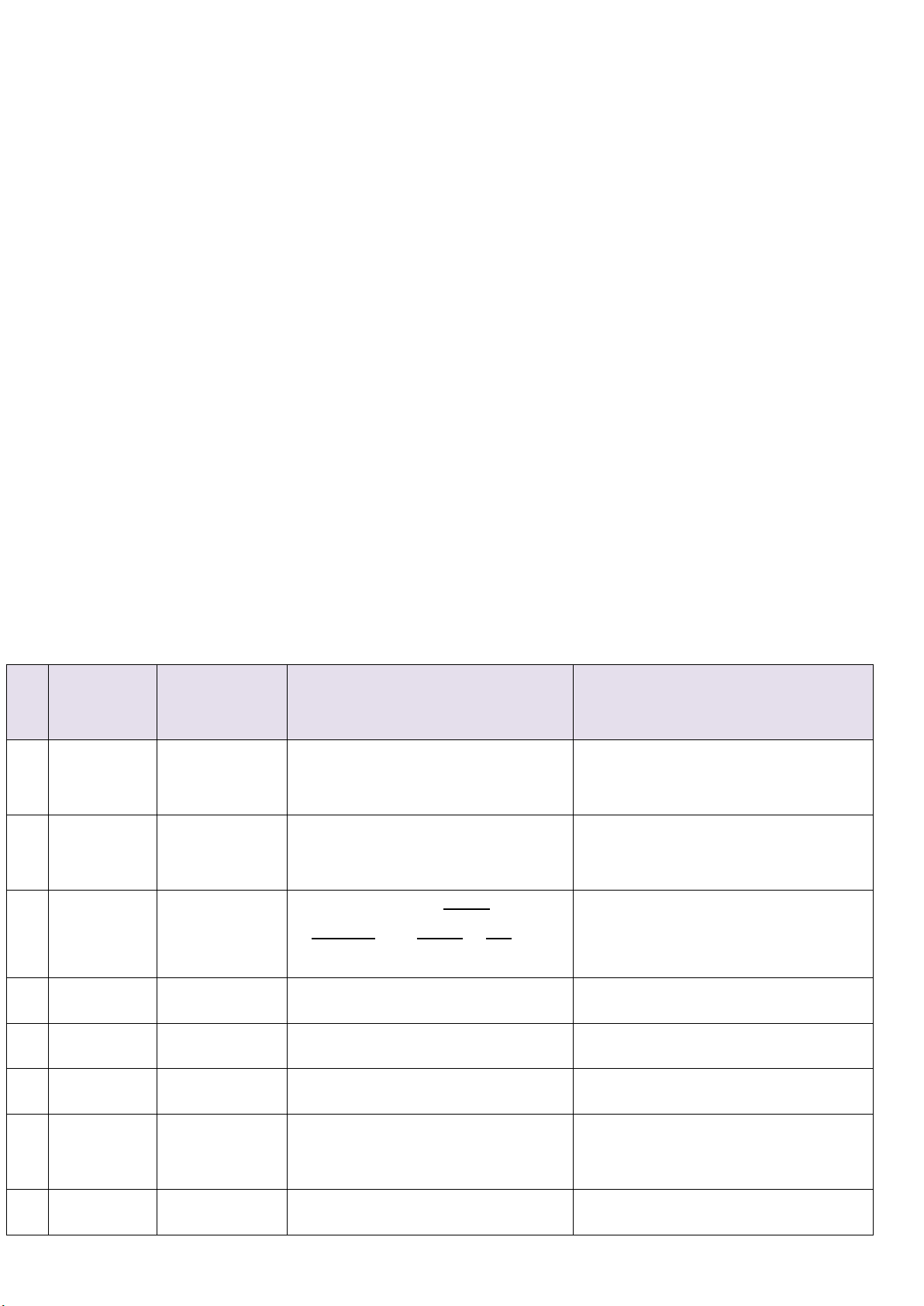

Questions 14-20

The reading passage has seven paragraphs, A –H.

Choose the correct heading for paragraphs A-H from the list below.

Write the correct number, i-ix, in boxes 14-20 on your answer sheet.

List of Headings

i. research findings into habitats and decisions made

ii. fluctuation in bittern number iii. protect the

young bittern iv. international cooperation works

v. began in calculation of the number.

vi. importance of food vii. Research

has been successful. viii. research

into the reed bed

ix. reserve established holding bittern in winter

14 Paragraph A

15 Paragraph B

16 Paragraph C

17 Paragraph D

18 Paragraph F

19 Paragraph G

20 Paragraph H

lOMoARcPSD|44862240

Questions 21-26

Answer the questions below.

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS AND/OR.A NUMBERfrom the passage for

each answer.

21 When did the bird of bitten reach its peak of number?

22 What does the author describe the bittern’s character?

23 What is the main cause for the chick bittern’s death?

24 What is the main food for chick bittern?

25 What system does it secure the stability for bittern’s population? 26 Besides bittern and rare vegetation,

what mammal does the protection plan benefit?

Question 27

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D. Write your answers in boxes 27 0n your answer sheet.

27. What is the main purpose of this passage?

A Main characteristic of a bird called bittern.

B Cooperation can protect an endangered species.

C The difficulty of access information of bittern’s habitat and diet.

D To save wetland and reed bed in UK

Key

14 . Paragraph A

Answer: ii fluctuation in bittern numbers Key

words: fluctuation, numbers

‘Fluctuation in bittern numbers’ means the changes (increase and decrease) in the population of bitterns. In

the first paragraph, it says: ‘Breeding bitterns became extinct in the UK by 1886, but following

recolonisation early last century, numbers rose to a peak of about 70 booming (singing) males in the

1950s, falling to fewer than 20 by the 1990s’.

This means the number of bitterns reached the highest number – 70 males in the 1950s, and then declined to

20 males in the 1990s. Therefore, the answer is ii.

14. Đoạn A

Đáp án: ii sự thay ổi trong số lượng chim vạc

Từ khóa: sự thay ổi, số lượng

‘Sự thay ổi trong số lượng’ muốn nói ến sự tăng và giảm trong quần thể chim vạc.

Đoạn ầu tiên có nói rằng: ‘Chim vạc tuyệt chủng tại Vương quốc Anh vào năm 1886, nhưng sau tái thuộc ịa

hóa ở ầu thế kỉ trước, con số ã chạm móc cao nhất ở khoảng 70 con chim vạc ực vào những năm 1950, và

giảm xuống còn ít hơn 20 con vào những năm 1990’. Vì vậy, câu trả lời là ii.

15 . Paragraph B:

Answer: v began in calculation of the number. Key

words: calculation of number

‘Calculation of the number’ means the counting of the population of bitterns.

Paragraph B refers to ‘Our first challenge’ – so this was the beginning of the study. Then the paragraph

describes the method used: ‘The boom of the male bittern is its most distinctive feature during the breeding

season, and we developed a method to count them using the sound patterns unique to each individual.’.

Therefore, the answer is v.

lOMoARcPSD|44862240

15. Đoạn B:

Câu trả lời: v khởi ầu việc tính số lượng

Từ khóa: việc tính số lượng

‘Việc tính số lượng’ ý chỉ việc ếm số lượng những con chim vạc.

Đoạn B nhắc ến ‘Thử thách ầu tiên’ – vậy nên ây là khởi ầu của cuộc nghiên cứu. Sau ó, oạn văn miêu tả

phương pháp ược sử dụng: ‘Sự tăng nhanh trong số lượng chim vạc ực là ặc iểm nổi bật nhất của chúng

trong mùa sinh sản, và chúng tôi ã phát triển một phương pháp ể ếm chúng bằng việc sử dụng những tần

sóng âm thanh riêng biệt với mỗi cá thể.’. Vì vậy, câu trả lời là v.

16. Paragraph C:

Answer: i research findings into habitats and decisions made Key

words: research, habitats, decisions

‘Research findings into habitats and decisions made’ means studying where the bitterns preferred to live

and breed and reommending how to manage those habitats.

In paragraph C, it refers to: ‘Our first direct understanding of the habitat needs of breeding bitterns...’

and: ‘Based on this work, broad recommendations on how to manage...reed beds for bitterns were

made....’

Therefore, the answer is i.

16. Đoạn C:

Đáp án: i những kết quả trong nghiên cứu về môi trường sống và các quyết ịng ược ưa ra Từ

khóa: nghiên cứu, môi trường sống, quyết ịnh

‘Những kết quả trong nghiên cứu về môi trường sống và các quyết ịng ược ưa ra’ nói ến việc tìm hiểu về

những nơi sống ược chim vạc ưu chuộng và những gợi ý về việc quản lý những môi trường sống ó. Đoạn C

nhắc ến ‘Hiểu biết trực tiếp ầu tiên của chúng ta là những nhu cầu về môi trường sống ối với chim vạc..’ và:

‘Theo như nghiên cứu này, những gợi ý về việc quản lý … bãi sậy cho những con chim vạc ã ược ưa ra...’

Vì vậy, câu trả lời là i.

17. Paragraph D:

Answer: viii research into the reed bed Key

words: reed bed

‘Research into the reed bed’ means studying how the bitterns use reed beds to feed and to build nests.

Paragraph D refers to where bitterns prefer to feed and how to manage the reed beds to provide more food

and nesting sites. In paragraph D, it says: ‘The average home range sizes of the male bitterns we followed

(about 20 hectares) provided a good indication of the area of reed bed needed when managing or

creating habitat for this species. Female bitterns undertake all the incubation and care of the young, so it

was important to understand their needs as well. Over the course of our research, we located 87 bittern

nests and found that female bitterns preferred to nest in areas of continuous vegetation, well, into the

reed bed, but where water was still present during the driest part of the breeding season.’ Therefore,

the answer is viii.

17. Đoạn D:

Đáp án: viii nghiên cứu về các bãi sậy

Từ khóa: bãi sậy

‘Nghiên cứu về các bãi sậy’ nói ến cách mà chim vạc sử dụng các bãi sậy ể kiếm ăn và xây tổ.

Đoạn D nói ến những nơi chim vạc thích kiếm ăn và các quản lý các bãi sậy ể cung cấp nhiều thức ăn và

nơi làm tổ hơn. Đoạn D nói rằng: ‘Kích cỡ tổ trung bình của những chim vạc ực mà chúng ta ã theo dõi

(khoảng 20 héc ta) ã nói lên diện tích bãi sậy cần thiết khi quản lý và tạo môi trường sống cho loài chim

này. Những con chim vạc cái ảm nhận việc ấp trứng và nuôi nấng những con con, vậy nên việc hiểu những

lOMoARcPSD|44862240

nhu cầu của chúng cũng rất quan trọng. Xuyên suốt quá trình nghiên cứu, chúng tôi ã ịnh vị ược 87 ổ chim

vạc và tìm ra rằng những con chim vạc cái thích làm tổ ở những nơi có nhiều cây, sâu bên trong bãi sậy

nhưng cần phải có ủ lượng nước trong thời iểm khô hạn nhất của mùa sinh sản.’. Vì vậy, áp án là viii.

18. Paragraph F:

Answer: vi importance of food Key

words: importance, food

‘Importance of food’ means how much food is needed and how much food affects the population of

bitterns.

The opening sentence of this paragraph mentions ‘diet’ and ‘survival’. In paragraph F, it says: ‘Many

chicks did not survive to fledging and starvation was found to be the most likely reason for their

demise.’ ‘So, an important element of recent studies (including a PhD with the University of Hull) has

been the development of recommendations on habitat and water conditions to promote healthy native fish

populations.’

This means many of the chicks could not survive because of the lack of food and that maintaining a stable

fish population has been prioritised in protecting the bitterns. Therefore, vi is the answer.

19. Đoạn F:

Đáp án: vi tầm quan trọng của thức ăn Từ

khóa: tầm quan trọng, thức ăn

‘Tầm quan trọng của thức ăn’ nói ến lượng thức ăn cần thiết của chim vạc và tầm ảnh hưởng ể thức ăn ối

với chúng.

Câu ầu tiên của oạn ã nhắc ến ‘chế ộ ăn uống’ và ‘sự sống sót’. Đoạn F nói rằng: ‘Rất nhiều con chim non ã

không thể sống sót ể mọc lông và sự thiếu lương thực chính là lí do khả dĩ nhất cho cái chết của chúng.’ ‘Vì

vậy, một phần quan trọng trong những nghiên cứu gần ây (bao gồm nghiên cứu tiến sĩ với Đại học Hull)

chính là những gợi ý về môi trường và iều kiện nguồn nước ể phát triển quần thể cá bản ịa khỏe mạnh’.

Điều này có nghĩa rằng rất nhiều con chim non không thể sống sót vì sự thiếu thốn lương thực và rằng việc

duy trì quần thể cá ổn ịnh ã ược ề cao trong việc bảo vệ chim vạc. Vì vậy, áp án là vi.

19 . Paragraph G:

Answer: iii protect the young bittern Key

words: protect, young

‘Protect the young bittern’ indicates that the paragraph would discuss conservation of young bitterns. In

paragraph G, it says: ‘Once independent, radio-tagged young bitterns were found to seek out new sites

during their first winter’. The EU Life Project provided money to create and manage these new sites to

“secure a sustainable bittern population”.

Protect young bitterns: secure a sustainable bittern population with successful breeding. Therefore,

iii is the answer.

19. Đoạn G:

Đáp án: iii bảo vệ những con chim vạc non

Từ khóa: bảo vệ, non

‘Bảo vệ những con chim vạc non’ gợi ý rằng oạn văn sẽ bàn luận về việc bảo tồn chim vạc con.

Đoạn G nói rằng: ‘Một khi tự lập, những con chim vạc ược gắn tần số âm thanh sẽ tìm những nơi ở ở trong

mùa ông ầu tiên của chúng’. Chiến dịch EU Life ã cung cấp kinh tế ể tạo ra và quản lý những ịa iểm mới

này ể ‘ ảm bảo một quần thể chim vạc ổn ịnh’.

Bảo vệ chim vạc non: ảm bảo quần thể chim vạc ổn ịnh có khả năng sinh sản. Vì

vậy, áp án là iii.

lOMoARcPSD|44862240

20 . Paragraph H:

Answer: vii research has been successful

Key words: success

‘Research has been successful’ refers to the increase in numbers of bitterns in the UK.

In paragraph H, it says: ‘By 2004, the number of booming male bitterns in the UK had increased to 55,

with almost all of the increase being on those sites undertaking management based on advice derived from

our research’ and ‘...success has only been achieved through the trust, hard work and dedication of all the

managers, owners and wardens of sites....’ Therefore, vii is the answer.

20. Đoạn H

Đáp án: vii nghiên cứu thành công Từ

khóa: thành công

‘Nghiên cứu thành công’ muốn nói ến sự tăng trưởng trong số lượng chim vạc ở Vương quốc Anh. Đoạn H

nói rằng: ‘Đến năm 2004, số lượng chim vạc ực ở Vương quốc Anh sẽ tăng lên 55, với hầu hết sự tăng

trưởng là tại những nơi dưới sự quản lý dựa trên lời khuyên từ nghiên cứu của chúng tôi’ và ‘… thành công

ạt ược không chỉ vì niềm tin, sự siêng năng và sự tận tụy của tất cả những nhà quản lý, chủ sở hữu và người

cai quản các ịa iểm ó…’ Vì vậy, áp án là vii.

21 . When did the bittern reach its peak number?

Answer: (the) 1950s

Key words: reach peak number

Based on the question, we have to find the period of time in which the bittern population reached its highest

point. Since it asked ‘when’, it’s important to know that the information need is a year or period of time, so

try to find the appropriate numbers.

In paragraph A, it says ‘Breeding bitterns became extinct in the UK by 1886, but following recolonisation

early last century, numbers rose to a peak of about 70 booming (singing) males in the 1950s, falling to

fewer than 20 by the 1990s’

Therefore, the answer is (the) 1950s.

21. Tại thời iểm nào số lượng chim vạc ã chạm mốc cao nhất?

Đáp án: những năm 1950

Từ khóa: cạm móc cao nhất

Dựa vào câu hỏi, chúng ta cần tìm một khoảng thời gian khi mà quần thể chim vạc ã ạt con số cao nhất. Vì

câu hỏi là ‘khi nào’ nên iều quan trọng là tìm một năm hoặc một gian oạn nào ó, vậy nên hãy tìm ến những

con số phù hợp.

Ở oạn A ã nói ‘Chim vạc có khả năng sinh sản ã tuyệt chủng ở Vương quốc Anh vào năm 1886, nhưng sau

tái thuộc ịa hóa ở ầu thế kỉ trước, con số ã chạm móc cao nhất ở khoảng 70 con chim vạc ực vào những

năm 1950, và giảm xuống còn ít hơn 20 con vào những năm 1990’. Vì vậy áp án là ‘những năm 1950’.

22. How does the author describe the bittern’s character?

Answer: (being) shy

Key words: character=nature

Based on the question, we have to find words describing the personalities/ features of bitterns, preferably

adjectives talking about characters.

In paragraph B, it says: ‘Bitterns have cryptic plumage and a shy nature, usually remaining hidden within

the cover of reed bed vegetation’.

Therefore, the answer is: shy/a shy nature

lOMoARcPSD|44862240

22. Tác giả ã miêu tả tính cách của chim vạc như thế nào? Đáp

án: ngại ngùng

Từ khóa: tính cách = bản năng tự nhiên

Dựa vào câu hỏi, chúng ta phải tìm những từ miêu tả tính cách của chim vạc, có thể là các tính từ nói về

tính cách.

Đoạn B nói rằng: ‘Chim vạc có một bộ lông kín áo và tính cách ngại ngùng, thường hay trốn sau sự chắn

của các cây sợi’.

Vì vậy, áp án là: ngại ngường/ tính cách ngại ngùng.

23 . What is the main cause of death of bittern chicks?

Answer: starvation

Key words: cause, chick, death

Based on the question, we have to find reasons why the young bitterns are not able to survive.

In paragraph F, it says: ‘Many chicks did not survive to fledging and starvation was found to be the most

likely reason for their demise’.

Did not survive = died, most likely reason = main cause, demise = death Therefore,

the answer is starvation.

23. Nguyên nhân chính dẫn ến cái chết của những con chim vạc non là gì?

Đáp án: sự thiếu lương thực

Từ khóa: nguyên nhân, chim con, cái chết

Dựa vào câu hỏi, chúng ta cần tìm những lý do vì sao những con chim vạc non ã không thể sống sót. Đoan

F ã nói: ‘Rất nhiều con chim non ã không thể sống sót ể mọc lông và sự thiếu lương thực chính là lí do khả

dĩ nhất cho cái chết của chúng.’

Không thể sống sót = chết, lí do khả dĩ nhất = nguyên nhân chính Vì

vậy, áp án là sự thiếu lương thực.

24 . What is the main food for bittern chicks?

Answer: (native) fish

Key words: main food, chick

Based on the question, we have to find out what young bitterns eat the most.

In paragraph F, it says ‘The fish prey fed to chicks was dominated by those species penetrating into the

reed edge. So, an important element of recent studies (including a PhD with the University of Hull) has

been the development of recommendations on habitat and water conditions to promote healthy native fish

populations.’ Therefore, the answer is (native) fish.

24. Thức ăn chính của những con chim vạc non là gì? Đáp án: Cá (bản ịa)

Từ khóa: thức ăn chính, non

Dựa vào câu hỏi, cúng ta cần tìm ra món ăn mà chim vạc non thích nhất.

Đoạn F nó rằng: ‘Những con cá ể chim non ăn ã bị chiếm bởi các loài xâm nhập vào bìa bãi sậy. Vì vậy,

một phần quan trọng trong những nghiên cứu gần ây (bao gồm nghiên cứu tiến sĩ với Đại học Hull) chính

là những gợi ý về môi trường và iều kiện nguồn nước ể phát triển quần thể cá bản ịa khỏe mạnh’. Vì vậy,

áp án là cá (bản ịa).

25. What system is used to secure stability for the population of bitterns?

Answer: a partnership project /network of sites

Keywords: system, secure stability

lOMoARcPSD|44862240

Based on the question, we have to find an organisation or institution that helps sustain the number of

bitterns.

In paragraph G, it says: ‘A network of 19 sites developed through this partnership project will secure

a more sustainable UK bittern population with successful breeding outside of the core area, less

vulnerable to chance events and sea level rise.’. Therefore, the answer is a partnership project/network

of sites.

25. Hệ thống nào ã ược sử dụng ể bảo ảm sự ổn ịnh cho quần thể chim vạc? Đáp

án: một dự án hợp tác/ một mạng lưới cái ịa iểm Từ khóa: hệ thống, bảo ảm sự

ổn ịnh

Dựa vào câu hỏi, chúng ta phải tìm ra một tổ chức góp phần bảo tồn số lượng chim vạc.

Đoạn G nói rằng: ‘Một mạng lưới gồm 19 ịa iểm ược xây dựng trong dự án hợp tác này sẽ bảo ảm một

quần thể chim vạc ổn ịnh với khả năng sinh sản ngoài khu vực trung tâm, không dễ bị ảnh hưởng bởi các sự

kiện ngẫu nhiên và sự dâng của mực nước biển.’. Vì vậy, áp án là một dự án hợp tác/ một mạng lưới cái

ịa iểm.

26 . Besides bitterns and rare vegetation, what mammal does the protection plan benefit?

Answer: (the) water vole/water voles

Key words: mammal, benefit

Based on the question, we have to find the animals – mammals, that are positively influenced by the

protection plan.

In paragraph I, it says: ‘Malltraeth Reserve now forms part of the UK network of key sites for water vole

(a UK priority species)...’ So, the management of this kind of wetland site is also good for a rare species of

mammal, the water vole (an animal which looks like a rat, but which likes wet areas to find food). Although

other animals/mammals are mentioned, and also several plants, this mammal is linked to key sites which

are protected by the management plans.

So, the answer is (the) water vole/water voles.

26. Ngoài chim vạc và thực vật quý hiếm, ộng vật có vú nào ã hưởng lợi ích từ kế hoạch bảo vệ?

Đáp án: chuột nước

Từ khóa: ộng vật có vú, lợi ích

Dựa vào câu hỏi, ta cần phải tìm một loài ộng vật có vú dược ảnh hưởng tích cực bởi kế hoạch quản lý.

Đoan I nói rằng: ‘Bảo tồn Malltraeth hiện ã hình thành một phần mạng lưới những ịa iểm quan trọng ở

Vương quốc Anh cho chuột nước (một loài vật quan trọng của Vương quốc Anh)…’ Vì vậy, sự quản lý loại

ất ẩm này cũng ã mang lại lợi ích cho một loài ộng vật có vú – chuột nước. Đáp án là chuột nước.

27 . What is the main purpose of this passage?

A Main characteristic of a bird called the bittern.

B Cooperation can protect an endangered species.

C The difficulty of access to information about the bittern’s habitat and diet.

D To save wetland and reed bed in the UK

Answer: B

The main purpose of the passage is the biggest message the passage wants to convey and probably the idea

that was discussed the most.

The passage introduced the bittern – an endangered species - and went on to describe the research studying

their habitats and survival. The ending paragraphs discussed an international project that helps to maintain

the population of this bird and its achievements. Therefore, B is the answer.

lOMoARcPSD|44862240

For A. only one characteristic of bitterns was mentioned – shyness - and this was not further developed, so

A is not the answer.

For C, the passage talked about bittern’s habitat and diet, but not the difficulties in finding those pieces of

information. C is not the answer.

For D, the passage mentioned protecting wetland and reed bed, but this is in the consideration of the bittern,

as indicated by the title, not these sites themselves. D is not the answer.

27. Mục ích chính của oạn trích là gì?

Đáp án: B

Mục ích chính của oạn trích chính là thông iệp lớn nhất mà oạn văn muốn truyền tải và có lẽ là luận iểm

ược bàn luận nhiều nhất.

Đoạn văn ã giới thiệu chim vạc – một loài vật có nguy cơ tuyệt chủng, và sau ó tiếp tục nói về nghiên cứu

về môi trường sống và sự sống sót của chúng. Những oạn vă cuối bàn luận vè một dự án quốc tế nhằm giúp

bảo tồn chim vạc và những thanh tựu của dự án ó. Vì vậy, áp án là B.

Đáp án A: duy nhất một tính cách của chm vạc ược nhắc ến – ngại ngùng và không ược triển khai thêm

nữa, vì vậy A không phải áp án.

Đáp án C: ọa n trích nói về môi trường sống và thức ăn của chim vạc nhưng không nói ến những khó khăn

trong việc tìm hiểu về những thông tin ó. C không phải áp án.

Đáp án D: oạn văn nhắc ến bảo tồn ất ẩm là bãi sậy nhưng là của chim vạc, chứ không chỉ là những ịa iểm

này. D không phải áp án.

Q Key words

in questions

Similar words

in the text

Meaning Tạm dịch

15 calculation a method to

count

counting the number of something Cách ếm số lượng

16 habitat home a place where something/ some one

lives

Nơi ở của cái gì ó/ ai ó

19 protect secure to make certain something

is protected from danger or risk

Bảo vệ cai gì khỏi các nguy hiểm hay

nguy cơ

21 reach a peak rise to a peak reaching the highest point or number Chạm mốc cao nhất

22 character nature a particular quality of something Một tính chất ặc biệt nào ó

23 young (bird) chick a baby bird Chim non

23 main cause most likely

reason

the biggest reason contributing to a

result

Lý do lớn nhất dẫn ến kết quả nào ó

23 death demise the end of life Sự kết thúc của sự sồng

lOMoARcPSD|44862240

24 food starvation the state of having no food for a long

period, often causing death

Tình trạng thiếu thức ăn trong khoảng

thời gian dài, thường dẫn ến tử vong

26 vegetation plant trees, living things that grow in earth, in

water, or on other plants

Cây

Một thực thể sống mọc ở trên ất, nước

hay các loài cây khác

2. The Origins of Laughter

While joking and wit are uniquely human inventions, laughter certainly is not. Other creatures, including

chimpanzees, gorillas and even rats, laugh. The fact that they laugh suggests that laughter has been around

for a lot longer than we have.

There is no doubt that laughing typically involves groups of people. “Laughter evolved as a signal to others

-it almost disappears when we are alone,” says Robert Provine, a neuroscientist at the University of

Maryland. Provine found that most laughter comes as a polite reaction to everyday remarks such as “see

you later”, rather than anything particularly funny. And the way we laugh depends on the company we’re

keeping. Men tend to laugh longer and harder when they are with other men, perhaps as a way of bonding.

Women tend to laugh more and at a higher pitch when men are present, possibly indicating flirtation or

even submission.

To find the origins of laughter, Province believes we need to look at play. He points out that the masters of

laughing are children, and nowhere is their talent more obvious than in the boisterous antics, and the

original context is play. Well-known primate watchers, including Dian Fossey and Jane Goodall, have long

argued that chimps laugh while at play. The sound they produce is known as a pant laugh. It seems obvious

when you watch their behavior -they even have the same ticklish spots as we do. But after removing the

context, the parallel between human laughter and a chimp’s characteristic pant laugh is not so clear. When

Provine played a tape of the pant laughs to 119 of his students, for example, only two guessed correctly

what it was.

These findings underline how chimp and human laughter vary. When we laugh the sound is usually

produced by chopping up a single exhalation into a series of shorter with one sound produced on each

inward and outward breath. The question is: does this pant laughter have the same source as our own

laughter? New research lends weight to the idea that it does. The findings come from Elke Zimmerman,

head of the Institute for Zoology in Germany, who compared the sounds made by babies and chimpanzees

in response to tickling during the first year of their life. Using sound spectrographs to reveal the pitch and

intensity of vocalizations, she discovered that chimp and human baby laughter follow broadly the same

pattern. Zimmerman believes the closeness of baby laughter to chimp laughter supports the idea that

laughter was around long before humans arrived on the scene. What started simply as a modification of

breathing associated with enjoyable and playful interactions has acquired a symbolic meaning as an

indicator of pleasure.

Pinpointing when laughter developed is another matter. Humans and chimps share a common ancestor that

lived perhaps 8 million years ago, but animals might have been laughing long before that. More distantly

related primates, including gorillas, laugh, and anecdotal evidence suggests that other social mammals can

do too. Scientists are currently testing such stories with a comparative analysis of just how common

laughter is among animals. So far, though, the most compelling evidence for laughter beyond primates

comes from research done by Jaak Panksepp from Bowling Green State University, Ohio, into the

ultrasonic chirps produced by rats during play and in response to tickling.

All this still doesn’t answer the question of why we laugh at all. One idea is that laughter and tickling

originates as a way of sealing the relationship between mother and child. Another is that reflex response to

tickling is protective, alerting us to the presence of crawling creatures that might harm us or compelling us

to defend the parts of our bodies that are most vulnerable in hand-to-hand combat. But the idea that has

gained most popularity in recent years is that laughter in response to tickling is a way for two individuals to

signal and test their trust in one another. This hypothesis starts from the observation that although a little

lOMoARcPSD|44862240

tickle can be enjoyable, if it goes on too long it can be torture. By engaging in a bout of tickling, we put

ourselves at the mercy of another individual, and laughing is what makes it a reliable signal of trust

according to Tom Flamson, a laughter researcher at the University of California, Los Angels. “Even in rats,

laughter, tickle, play and trust are linked. Rats chirp a lot when they play,” says Flamson. “These chirps can

be aroused by tickling. And they get bonded to us as a result, which certainly seems like a show of trust.”

We’ll never know which animal laughed the First laugh, or why. But we can be sure it wasn’t in response to

a prehistoric joke. The funny thing is that while the origins of laughter are probably quite serious, we owe

human laughter and our language-based humor to the same unique skill. While other animals pant, we

alone can control our breath well enough to produce the sound of laughter. Without that control there would

also be no speech -and no jokes to endure.

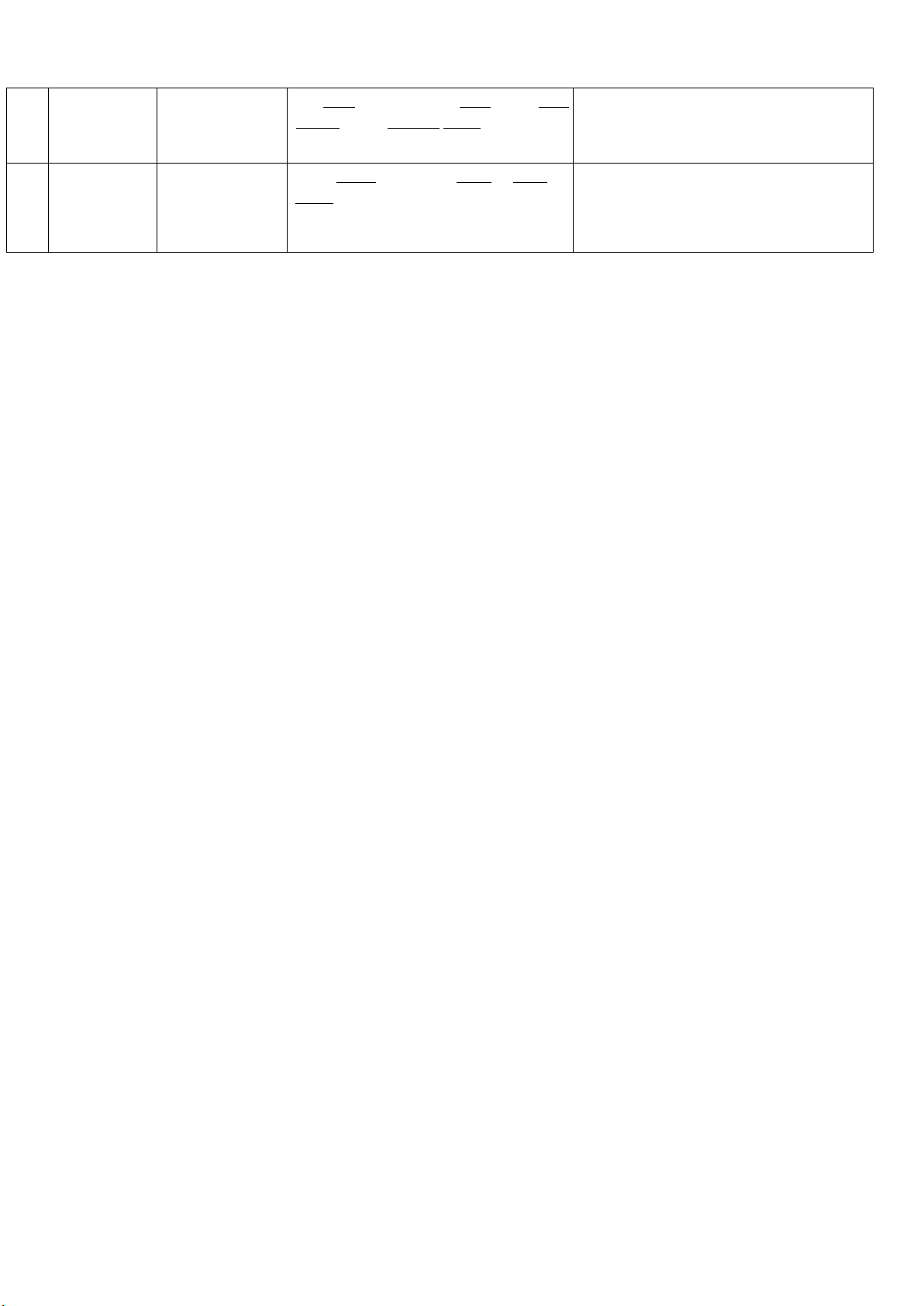

Questions 1-6

Look at the following research findings (questions 1-6) and the list of

people below

Match each finding with the correct person A, B, C or D.

Write the correct letter A, B, C or Din boxes 1-6 on your answer

sheet NB you my use any letter more than one.

1. Babies and some animals produce laughter which sounds similar

2. Primates are not the only animals who produce laughter

3. Laughter can be used to show that we feel safe and secure with others

4. Most human laughter is not a response to a humorous situation

5. Animal laughter evolved before human laughter

6. Laughter is a social activity

Lists of people A

Provine

B Zimmerman

C Panksepp

D Flamson

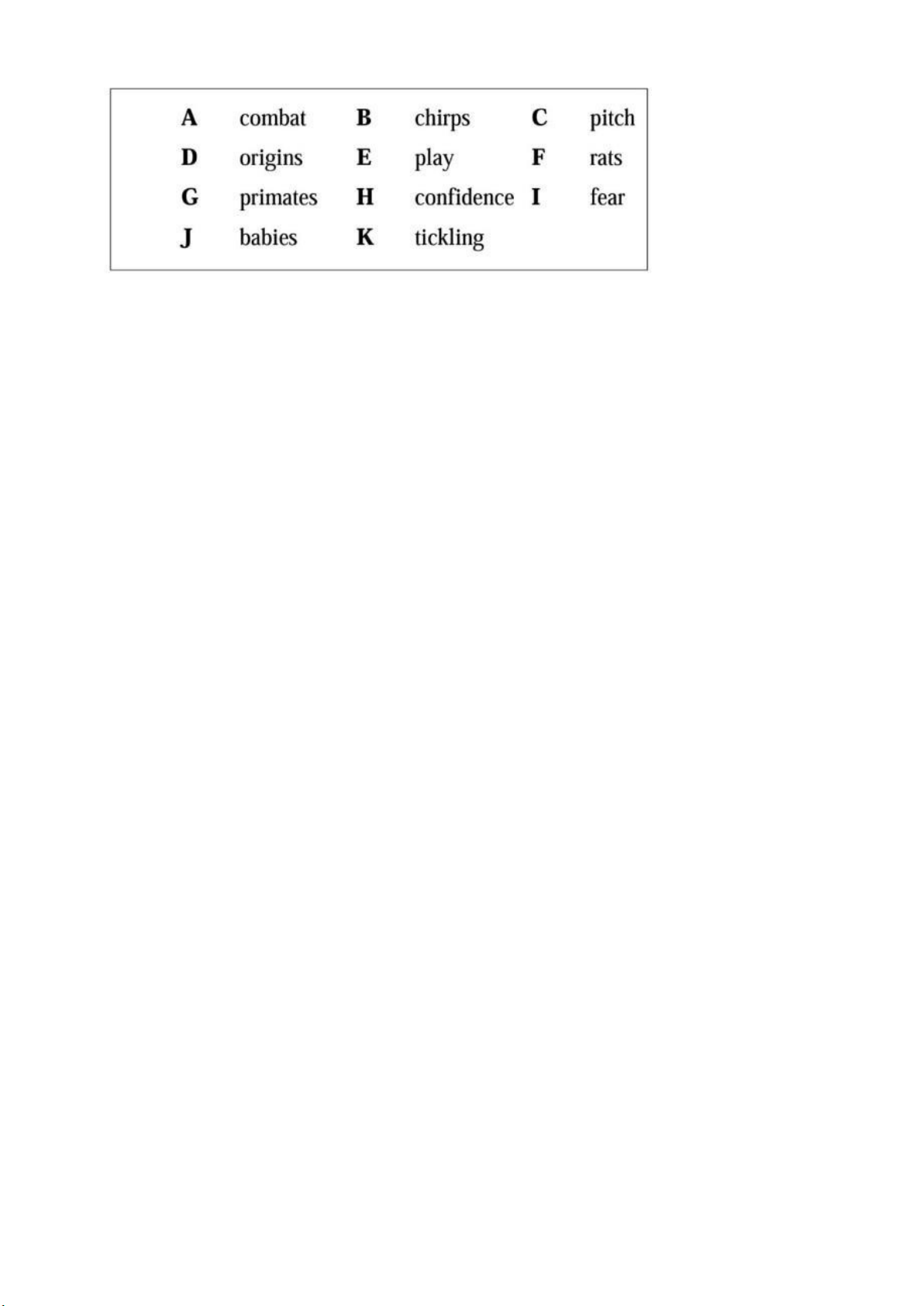

Questions 7-10

Complete the summary using the list of words, A-K, below

Write the correct letter, A-K, in boxes 7-10 on your answer sheet.

Some scientists believe that laughter first developed out of 7 __________________________________ .

Research has revealed that human and chimp laughter may have the same 8

____________ . Scientists have long been aware that 9 _____________________ laugh, but it now

appears that laughter might be more widespread than once thought. Although the reasons why humans

started to laugh are still unknown, it seems that laughter may result from the 10 we feel with another

person.

lOMoARcPSD|44862240

Question 11-13

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Reading Passage 1?

On your answer sheet please write

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts with the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

11. Both men and women laugh more when they are with members of the same sex.

12. Primates lack sufficient breath control to be able to produce laughs the way humans do.

13. Chimpanzees produce laughter in a wider range of situations than rats

1 - 6. Look at the following research findings (questions 1-6) and the list of people

Match each finding with the correct person A, B, C or D.

1. Babies and some animals produce laughter which sounds similar

2. Primates are not the only animals who produce laughter

3. Laughter can be used to show that we feel safe and secure with others

4. Most human laughter is not a response to a humorous situation

5. Animal laughter evolved before human laughter

6. Laughter is a social activity

Lists of people

A Provine

B Zimmerman

C Panksepp

D Flamson

lOMoARcPSD|44862240

5

Answer: 1. B – 2. C – 3. D – 4. A – 5. B – 6. A Paragraph

1: There is no doubt...

Paragraph 2: To find the origins...

Paragraph 3: These findings underline...

Paragraph 4: Pinpointing when...

Paragraph 5: All this still...

Paragraph 6: We’ll never know...

1. Babies and some animals produce laughter which sounds similar

Key words: sounds similar

Based on the question and particularly the key words, we need to find the information about a comparison

between babies’ laughter and some animals’ laughter. In the last sentences of the third paragraph, when

talking about Zimmerman, the author mentioned “she discovered that chimp and human baby laughter

follow broadly the same pattern”. This means that Zimmerman was the one who did research about the

similarity in the way babies and some animals produce laughter.

Tạm dịch:

1. Trẻ sơ sinh và một số ộng vật tạo tiếng cười nghe giống nhau

Từ khóa: nghe giống nhau

Dựa trên câu hỏi và ặc biệt là các từ khóa, chúng ta cần phải tìm thông tin về một sự so sánh giữa tiếng cười

của em bé và của một số loài ộng vật. Trong câu cuối cùng của oạn thứ ba, khi nói về Zimmerman, tác giả ề

cập ến việc "cô phát hiện ra rằng tiếng cười của tinh tinh và của con người có nhiều iểm giống nhau".

Điều này có nghĩa rằng Zimmerman là người ã nghiên cứu về sự tương ồng trong cách những ứa trẻ và một

số loài ộng vật tạo ra tiếng cười.

2. Primates are not the only animals who produce laughter

Key words: primates, not the only

Based on the question and particularly the key words, we need to find the information about animals that

produce laughter. In the fifth sentence of the fourth paragraph, the author mentioned “So far, though, the

most compelling evidence for laughter beyond primates comes from research done by Jaak Panksepp”.

“laughter beyond primates” refers to laughter comes from other kinds of animals, which means primates are

not the only animals who produce laughter. The author of that research was Panksepp.

Pay attention to the meaning of “beyond”. “Beyond” very often has a meaning of ‘outside the limits of

something’. http://dictionary.cambridge.org/grammar/british-grammar/beyond Tạm dịch:

2. Linh trưởng không phải là ộng vật duy nhất tạo ra tiếng cười

Từ khóa: linh trưởng, không phải duy nhất

Dựa trên câu hỏi và ặc biệt là các từ khóa, chúng ta cần phải tìm thông tin về các loài ộng vật tạo ra tiếng

cười. Trong câu thứ năm của oạn thứ tư, tác giả ề cập ến "Tuy nhiên, cho ến nay, các bằng chứng thuyết

phục nhất cho tiếng cười bởi các loài khác ngoài linh trưởng xuất phát từ nghiên cứu thực hiện bởi Jaak

Panksepp". "Tiếng cười của loài khác ngoài linh trưởng" ề cập ến tiếng cười ến từ các loại ộng vật khác, có

nghĩa là các loài linh trưởng không phải là ộng vật duy nhất tạo ra tiếng cười. Chủ nhân của nghiên cứu ó là

Panksepp.

lOMoARcPSD|44862240

Hãy chú ý ến ý nghĩa của "beyond". "Beyond" thường mang nghĩa 'ngoài giới hạn của một cái gì ó'.

http://dictionary.cambridge.org/grammar/british-grammar/beyond

3. Laughter can be used to show that we feel safe and secure with others

Key words: safe and secure

Based on the question and particularly the key words, we need to find the information about the signal or

the message laughter can send out. In the fifth paragraph, the author gave some possibilities about the

meaning of laughter. One of those possibilities is the idea of Tom Flamson: “By engaging in a bout of

tickling, we put ourselves at the mercy of another individual, and laughing is what makes it a reliable

signal of trust according to Tom Flamson”. In the statement above, “safe” and “secure” can be considered

as the replacement of “reliable” and “trust”.

Tạm dịch:

3. Tiếng cười có thể ược dung ể thể hiện rằng ta cảm thấy an toàn và ược bảo vệ với người khác

Từ khóa: an toàn và ược bảo vệ

Dựa trên câu hỏi và ặc biệt là các từ khóa, chúng ta cần phải tìm thông tin về các tín hiệu hoặc những lời

nhắn tiếng cười có thể truyền ạt ra. Trong oạn thứ năm, các tác giả ã ưa ra một số khả năng về ý nghĩa của

tiếng cười. Một trong những khả năng là ý tưởng của Tom Flamson: "Bằng cách cù nhau, chúng ta khiến

người khác hoàn toàn có quyền kiểm soát mình, và cười là tín hiệu áng tin cậy của lòng tin, theo Tom

Flamson". Trong tuyên bố trên, "an toàn" và " ược bảo vệ" có thể ược coi là sự thay thế của " áng tin cậy"

và "lòng tin".

4. Most human laughter is not a response to a humorous situation

Key word: not a response, humorous situation

In the second sentence of the first paragraph, the author wrote “Provine found that most laughter comes as

a polite reaction to everyday remarks such as “see you later”, rather than anything particularly funny”. In

this sentence, “comes as a polite reaction” can be considered as “a response”, “funny” as “humorous”. So

the statement above belongs to Provine.

Response = reaction

Humorous = funny Tạm

dịch:

4. Hầu hết tiếng người của con người không phải là phản ứng trước một tình huống hài hước

Từ khóa: không phải là phản ứng, tình huống hài hước

Trong câu thứ hai của oạn ầu tiên, tác giả viết "Provine tìm ra rằng hầu hết tiếng cười ến như là một phản

ứng lịch sự với những nhận xét hàng ngày như "gặp lại sau nhé", chứ không phải bất cứ iều gì ặc biệt buồn

cười". Trong câu này, " ến như là một phản ứng lịch sự" có thể ược coi như là "một phản ứng", "buồn cười"

là "hài hước". Vì vậy, tuyên bố trên là của Provine.

Response (phản ứng) = reaction (phản ứng)

Humorous (Hài hước) = funny (buồn cười)

5. Animal laughter evolved before human laughter

Key word: evolve, before

Based on the question and particularly the key words, we need to find the information about when laughter

developed. In the third paragraph, the author mentioned “Zimmerman believes the closeness of baby

lOMoARcPSD|44862240

laughter to chimp laughter supports the idea that laughter was around long before humans arrived on the

scene”

Tạm dịch:

5. Tiếng cười của ộng vật tiến hóa trước khi tiếng cười của con người

Từ khóa: tiến hoá, trước

Dựa trên câu hỏi và ặc biệt là các từ khóa, chúng ta cần phải tìm các thông tin về thời gian tiếng cười phát

triển. Trong oạn thứ ba, tác giả ề cập "Zimmerman tin rằng sự liên quan mật thiết giữa tiếng cười của em bé

và của tinh tinh ủng hộ cho ý tưởng rằng tiếng cười ã tồn tại trong một khoảng thời gian dài trước khi

con người xuất hiện"

6. Laughter is a social activity Keyword: social

Based on the question and particularly the key words, we need to find the information about the limit of

laughter. In the first sentence of the passage, it is stated that Provine claimed “There is no doubt that

laughing typically involves groups of people. “Laughter evolved as a signal to others -it almost disappears

when we are alone”. “Groups of people” refers to “society”. Besides, laughter “almost disappears when we

are alone” so obviously the researcher here is trying to suggest that laughter is a social activity.

Tạm dịch:

6. Tiếng cười là một hoạt ộng xã hội Từ khóa: xã hội

Dựa trên câu hỏi và ặc biệt là các từ khóa, chúng ta cần phải tìm các thông tin về giới hạn của tiếng cười.

Câu ầu tiên của oạn văn có nói rằng Provine tuyên bố "Không còn nghi ngờ gì nữa, tiếng cười thường liên

quan ến các nhóm người. "Tiếng cười phát triển như là một tín hiệu cho những người khác – nó gần như

biến mất khi chúng ta ở một mình". "Một nhóm người" nói về "xã hội". Bên cạnh ó, tiếng cười "gần như

biến mất khi chúng ta ang ở một mình" như vậy rõ ràng là nhà nghiên cứu ở ây ang gợi ý rằng tiếng cười là

một hoạt ộng xã hội.

7. Some scientists believe that laughter first developed out of ____.

Answer: E. play

Key word: first developed

Based on the question and particularly the key words, we need to find the information about the origins of

laughter. And the second paragraph is used to discuss this issue, due to its opening “to find the origins of

the laughter”. In this paragraph, the author mentioned “He points out that the masters of laughing are

children, and nowhere is their talent more obvious than in the boisterous antics, and the original context is

play”.

Original context = first developed.

Tạm dịch:

7. Một số nhà khoa học tin rằng tiếng cười ược phát triển ầu tiên từ việc ____.

=> Đáp án: E. chơi

Từ khóa: ầu tiên phát triển

Dựa trên câu hỏi và ặc biệt là các từ khóa, chúng ta cần phải tìm ra thông tin về nguồn gốc của tiếng cười.

Và oạn thứ hai ược sử dụng ể thảo luận về vấn ề này, do phần ầu của nó là " ể tìm nguồn gốc của tiếng

cười". Trong oạn văn này, tác giả ề cập ến "Ông chỉ ra rằng những bậc thầy về tiếng cười là trẻ em, và

lOMoARcPSD|44862240

không nơi nào là tài năng của chúng ược thể hiện rõ ràng hơn là trong những trò náo nhiệt, và bối cảnh

ban ầu là chơi".

Original context (bối cảnh ban ầu) = first developed (phát triển ầu tiên)

8. Research has revealed that human and chimp laughter may have the same ____. Answer:

D. origins

Key words: human and chimp laughter, the same

Based on the question and particularly the key words, we need to find the information about a comparison

between human laughter and chimp laughter. This information lies in the third paragraph. “The question is:

does this pant laughter have the same source as our own laughter? New research lends weight to the idea

that it does.” Source = origins

Tạm dịch:

8. Nghiên cứu ã cho thấy rằng tiếng cười của con người và tinh tinh có thể có cùng ____.

=> Đáp án: D. nguồn gốc

Từ khóa: tiếng cười của con người và tinh tinh, cùng

Dựa trên câu hỏi và ặc biệt là các từ khóa, chúng ta cần phải tìm thông tin về một sự so sánh giữa tiếng cười

của con người và tinh tinh. Thông tin này nằm trong oạn thứ ba. "Câu hỏi ặt ra là: liệu kiểu cười và thở này

có cùng một nguồn gốc như tiếng cười của chúng ta? Nghiên cứu mới ủng hộ ý tưởng rằng nó úng là có

cùng nguồn gốc."

Source (nguồn gốc) = origins (nguồn gốc)

9. Scientists have long been aware that ____ laugh, but it now appears that laughter might be more

widespread than once thought

Answer: G. primates

Key words: long, now, more widespread, once thought.

Based on the question and particularly the key words, we need to find the information about the limits of

laughter among animals and the process of the research about laughter. In the fourth paragraph, the author

mentioned “More distantly related primates, including gorillas, laugh, and anecdotal evidence suggests

that other social mammals can do too. Scientists are currently testing such stories with a comparative

analysis of just how common laughter is among animals”. This means that at first, scientists only found the

ability to laugh of primates, but currently, they found evidence which suggests that other social mammals

can do too.

Common = widespread

Tạm dịch:

9. Các nhà khoa học từ lâu ã biết rằng ____ cười, nhưng bây giờ có vẻ như là tiếng cười phổ biến

rộng rãi hơn là chúng ta nghĩ

=> Đáp án: G. loài linh trưởng

Từ khóa: từ lâu, bây giờ, rộng rãi hơn, từng nghĩ.

Dựa trên câu hỏi và ặc biệt là từ khóa, chúng ta cần phải tìm thông tin về các giới hạn của tiếng cười của

ộng vật và quá trình nghiên cứu về tiếng cười. Trong oạn thứ tư, tác giả ề cập ến "Các loài linh trưởng có

lOMoARcPSD|44862240

họ hàng xa hơn, bao gồm khỉ ột, cười, và bằng chứng cho thấy ộng vật có vú khác cũng có thể cười. Các

nhà khoa học ang thử nghiệm iều này với một phân tích so sánh như thế nào tiếng cười phổ biến như thế

nào trong những loài ộng vật". Điều này có nghĩa rằng lúc ầu, các nhà khoa học chỉ tìm thấy khả năng cười

của linh trưởng, nhưng hiện tại, họ ã tìm thấy bằng chứng cho thấy rằng ộng vật có vú khác cũng có thể làm

vậy.

Common (phổ biến) = widespread (rộng rãi)

10. Although the reasons why humans started to laugh are still unknown, it seems that laughter may

result from the ____ we feel with another person.

Answer: H. confidence

Key words: the reasons why, result from, feel with another person

In the fifth paragraph, the author mentioned “the idea that has gained most popularity in recent years is

that laughter in response to tickling is a way for two individuals to signal and test their trust in one

another” .

Trust = confidence In

response to = result from

Tạm dịch:

10. Mặc dù những lý do tại sao con người bắt ầu cười vẫn còn là iều bí ẩn, dường như tiếng

cười là kết quả của sự ____ chúng ta cảm thấy với một người khác.

=> Đáp án: H. sự tin tưởng

Từ khóa: lý do tại sao, là kết quả của, cảm thấy với một người khác

Trong oạn thứ năm, tác giả ề cập "ý tưởng trở nên phổ biến nhất trong những năm gần ây là tiếng cười ể

phản ứng với việc cù nhây là một cách ể hai cá nhân ể báo hiệu và kiểm tra sự tin tưởng với nhau".

Trust (sự tin tưởng) = confidence (sự tin tưởng)

In response to ( ể áp ứng/phản ứng với) = result from (là kết quả của)

11. Both men and women laugh more when they are with members of the same sex.

Answer: False

Key words: Both men and women, more, the same sex

We have to find information about the relevance between laughter and gender. And this information lies in

the first paragraph. “Men tend to laugh longer and harder when they are with other men, perhaps as a way

of bonding. Women tend to laugh more and at a higher pitch when men are present.” The tendency

relating to laughter among men differs completely from the one in laughter relating to women. So the

answer is False.

Tạm dịch:

11. Cả àn ông và phụ nữ cười nhiều hơn khi họ ở với các thành viên cùng giới.

=> Đáp án: FALSE

Từ khóa: Cả àn ông và phụ nữ, nhiều hơn, cùng giới

lOMoARcPSD|44862240

Chúng ta phải tìm thông tin về sự liên quan giữa tiếng cười và giới tính. Và thông tin này nằm trong oạn ầu

tiên. "Đàn ông có xu hướng cười lâu hơn và nhiều hơn khi họ ở cùng với người àn ông khác, có lẽ là một

cách ể thân thiết. Phụ nữ có xu hướng ể cười nhiều hơn và ở một tông cao hơn khi người àn ông có mặt. "

Các xu hướng liên quan ến tiếng cười giữa những người àn ông khác hoàn toàn so với xu hướng cười giữa

những người phụ nữ. Vì vậy, câu trả lời là False.

12. Primates lack sufficient breath control to be able to produce laughs the way humans do

Answer: True

Key words: lack, sufficient breath control

In the last paragraph, the author claimed “While other animals pant, we alone can control our breath well

enough to produce the sound of laughter”. This means that only humans have sufficient breath control to

produce laughs. The word “while” is a conjunction which means ‘in contrast with something else’. So it

suggests that other animals, including primates, do not have the same ability as humans do. Sufficient

breath control = control our breath well enough

Tạm dịch:

12. Linh trưởng không kiểm soát hơi thở ủ ể có thể tạo ra tiếng cười như con người

=> Đáp án: TRUE

Từ khóa: thiếu, kiểm soát hơi thở ủ

Trong oạn cuối, tác giả khẳng ịnh "Trong khi các ộng vật khác thở hổn hển, chúng ta có thể kiểm soát hơi

thở của chúng ta ủ tốt ể có thể tạo ra những tiếng cười". Điều này có nghĩa rằng chỉ có con người có

quyền kiểm soát hơi thở ủ ể tạo tiếng cười. Từ "trong khi" là một liên từ có nghĩa là 'trái ngược với cái gì

khác ". Vì vậy, nó cho thấy rằng loài ộng vật khác, bao gồm cả linh trưởng, không có khả năng tương tự

như con người.

kiểm soát hơi thở ủ = kiểm soát hơi thở của chúng ta ủ tốt

13. Chimpanzees produce laughter in a wider range of situations than rats do. Answer: Not

given

Key words: in a wider range of situations

In this passage, the author only mentioned chimpanzees as animals that can produce laughter and rats as

animals that chirp a lot when they play. There was no comparison between these kinds of animals, so the

statement is Not given.

Tạm dịch:

13. Tinh tinh tạo tiếng cười trong nhiều trường hợp hơn so với chuột.

=> Đáp án: NOT GIVEN

Từ khóa: trong nhiều trường hợp hơn

Trong oạn văn này, tác giả chỉ ề cập ến việc tinh tinh là loài ộng vật có thể tạo ra tiếng cười và chuột là ộng

vật kêu rất nhiều khi chúng chơi ùa. Không có sự so sánh giữa hai loài này, do ó nhận ịnh là

KHÔNG ĐƯỢC ĐỀ CẬP.

Bấm Tải xuống để xem toàn bộ.