Preview text:

Discover Electrochemistry Review

A brief review on methods and materials for electrode modification:

electroanalytical applications towards biologically relevant compounds Mariya Pimpilova1

Received: 10 September 2024 / Accepted: 12 November 2024 © The Author(s) 2024 OPEN Abstract

This review provides an overview of the advancements in electrochemical sensors and biosensors, along with their appli-

cations. The review covers the methods and materials used for modifying the surface of electrodes, and also discusses the

use of electrochemical sensors for quantitative analysis of biologically relevant compounds, such as hydrogen peroxide,

dopamine, serotonin, glucose, and other markers of oxidative stress and neurotransmitters. Various electrochemical

characterization methods have also been highlighted. Recently, there has been a growing interest in combining recogni-

tion elements with electronic elements to establish electrochemical sensors and biosensors. These devices have proven

to be effective in detecting chemical and biological targets through changes in electrochemical activity at electrode

interfaces. The use of nanomaterials has significantly improved the sensitivity and selectivity of electrochemical sensing

platforms. Electrode materials are critical to the construction of high-performance sensors for detecting target molecules.

The integration of functional nanomaterials can enhance catalytic activity, conductivity, and biocompatibility, leading to

more accurate and sensitive biosensing. Overall, the development of functional electrode materials, along with various

electrochemical methods, has greatly expanded the potential applications of electrochemical devices.

* Mariya Pimpilova, mariq.pimpilova@gmail.com | 1Laboratory of Biologically Active Substances, Institute of Organic Chemistry With

Centre of Phytochemistry, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 139 Ruski Blvd., 4000 Plovdiv, Bulgaria.

Discover Electrochemistry (2024) 1:12

| https://doi.org/10.1007/s44373-024-00012-8 Vol.:(0123456789) Review

Discover Electrochemistry (2024) 1:12

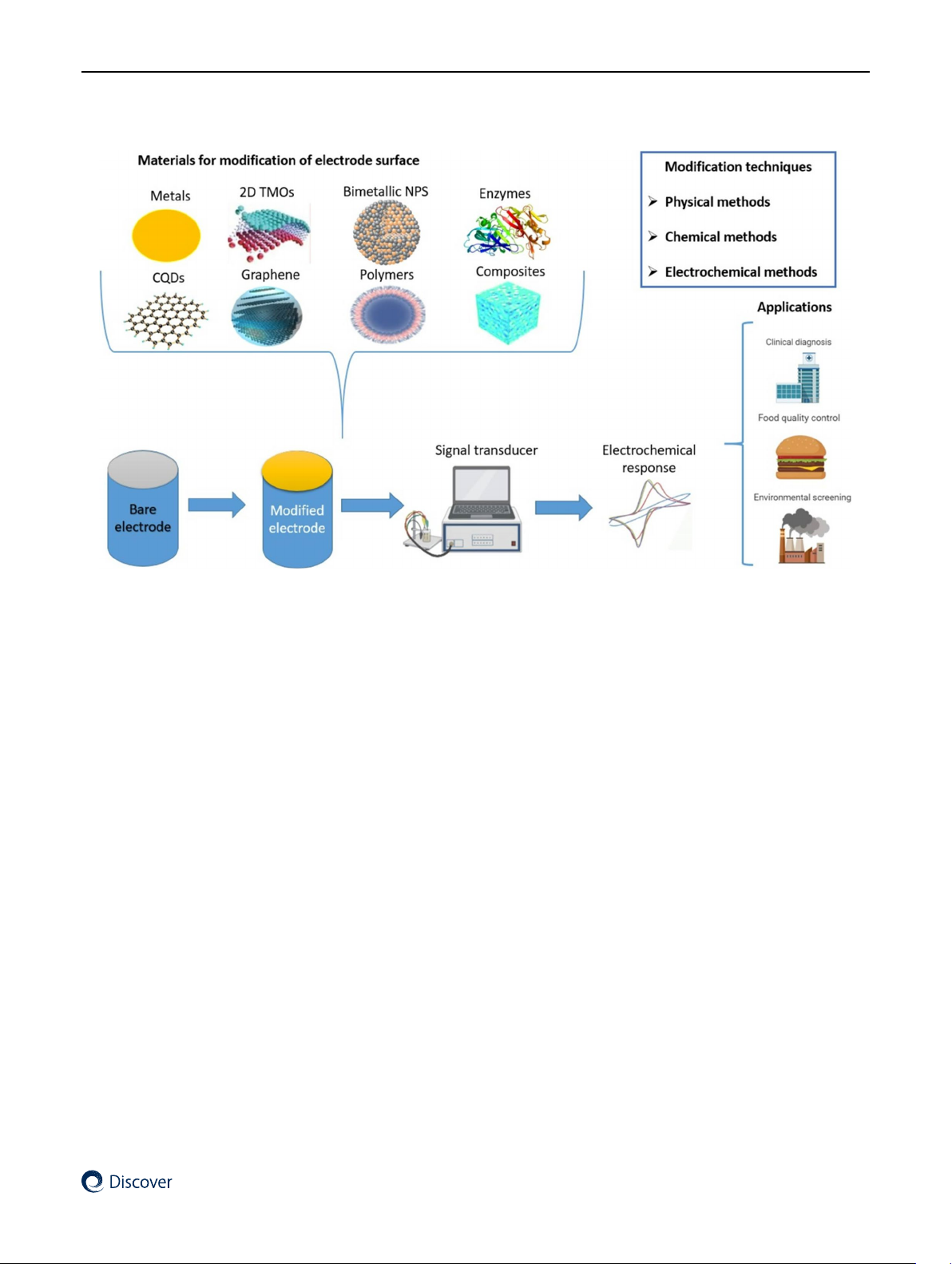

| https://doi.org/10.1007/s44373-024-00012-8 Graphical Abstract

Keywords Electrochemistry · Electrocatalysts · Biosensors · Nanoparticles 1 Introduction

One of the main goals of the world’s scientific efforts is to improve the quality of life. Achieving this aim is directly related

to the availability of methods for rapid diagnosis of common diseases, food quality control, and environmental monitor-

ing. Several scientific studies are aimed at developing analytical methods that meet these requirements. There are optical

(spectrophotometry, fluorometry, and surface plasmon resonance) [1], piezoelectric, and magnetoelectric [2], as well as

electrochemical methods available based on their detection principles [3].

In the past few decades, electroanalytical methods have attracted the attention of many researchers due to their

experimental simplicity, relatively low cost, and low detection limits, typically ranging from nanomolar (nM) to micro-

molar (µM) [4]. Other important prerequisites for their great popularity are their easy digitization and the compact size

of the equipment, the latter allowing in situ monitoring. For these reasons, they are widely used in areas such as clinical,

industrial, environmental, and agricultural analysis.

Electrode materials play a major role in the development of highly sensitive electroanalytical methods for the deter-

mination of target analytes. The modification of electrode surfaces is carried out with several main goals, including

increasing the sensitivity of the determination, improving the electrode selectivity, decreasing the limits of detection

and quantification, and inhibiting the electrode surface fouling phenomena. This is achieved either by increasing the

electrochemically active surface or by applying catalysts to it [5].

This review covers research conducted over the past two decades and mainly summarizes techniques and materials

for modifying electrode surfaces, their characterization using various electrochemical methods, and their successful

application to the quantitative analysis of biologically relevant compounds. Although several reviews have been pub-

lished on electrochemical methods and electrode modifications, this work presents a more recent overview, with an

emphasis on the use of nanomaterials and novel electrochemical approaches that were not covered in earlier reviews. Vol:.(1234567890)

Discover Electrochemistry (2024) 1:12

| https://doi.org/10.1007/s44373-024-00012-8 Review

1.1 Methods for modifying electrode surfaces

The most widely used working electrodes are carbon-based, characterized by relatively low cost, low background cur-

rent, good electrical conductivity, and chemical inertness [6]. In the past few years, glassy carbon has been a preferred

electrode material in electroanalysis due to its electrochemical stability over a wide range of potentials (from −1.5 V to

1.5 V) [3], impermeability to liquids and gases, and easy surface modification. It is characterized by high thermal and

chemical resistance, which makes it superior to other forms of carbon used as working electrodes. However, the glassy

carbon electrode (GCE) has several disadvantages such as easy surface contamination associated with adsorption pro-

cesses or unwanted precipitation, low rate of electrochemical reactions (i.e. oxidation and reduction processes occur at

high overpotential), which affects the sensitivity and selectivity of electroanalytical determinations. Another significant

drawback that limits its practical use is the occurrence of non-specific oxidation–reduction reactions at the electrode

surface [7]. With repeated use of GCE, the active centres on the surface may be partially or completely blocked, which

would lead to a negative impact on the reproducibility of the results. 1.2 Physical methods

In recent decades, there has been an intensive development of electrode modification techniques for various applica-

tions, such as solar energy conversion and storage [8], selective electroorganic synthesis [9], molecular electronics [10],

electrochromic display devices [11], corrosion protection [12] and electroanalysis [13]. In general, methods for modifying

electrode surfaces can be classified as physical, chemical, and electrochemical.

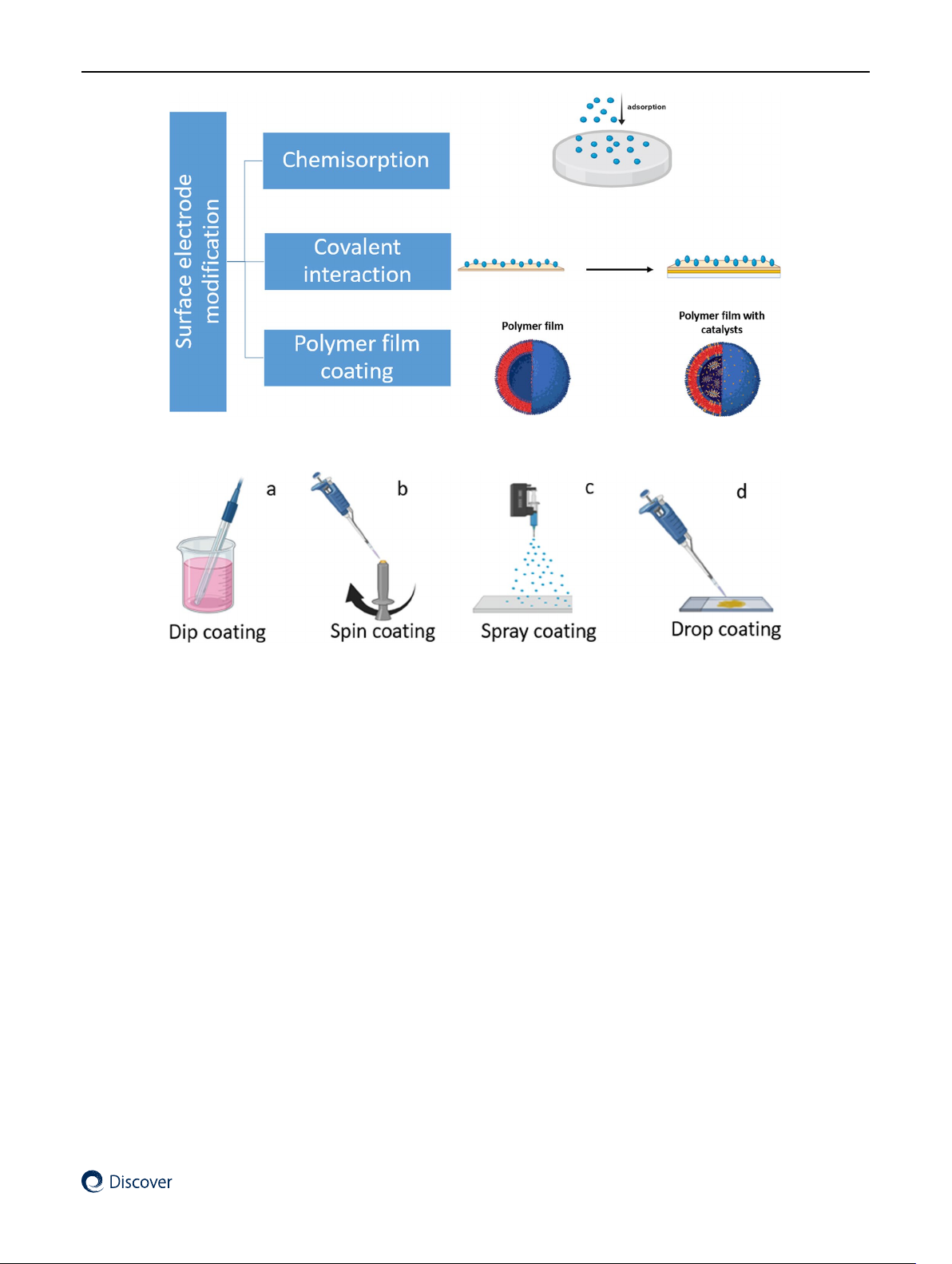

Physical methods include processes in which the modifier binds to the electrode surface through electrostatic forces,

hydrogen bonds, π-π-interactions, and Van Der Waals forces [14] (Fig. 1). One of the most applied physical techniques is

encapsulation, the application of polymer coatings and adsorption of surface-active substances [15]. The main disad-

vantages of physical methods are the strong anisotropy of the modifying phase, the uneven coating of the electrode

surface, the poor mechanical stability of the coatings, and the non-reproducible surface. 1.3 Chemical methods

Chemical methods such as chemisorption, covalent interactions, and polymer film coatings with or without catalyst/s

are often used for surface modification of conductive matrices. The adsorption of a modifier in a solution on an

electrode surface depends on the hydrophobicity of both the electrode and the modifier. For example, hydrophobic

Fig. 1 Schematic of physical methods for modification Vol.:(0123456789) Review

Discover Electrochemistry (2024) 1:12

| https://doi.org/10.1007/s44373-024-00012-8

Fig. 2 Schematic of chemical methods for modification

Fig. 3 Schematic of the four coating-based methods for deposition onto electrode surfaces

organic molecules absorb more readily on a hydrophilic platinum electrode, as show in [16]. Owing to the forma-

tion of covalent bonds between the functional groups on the electrode surface and the modifying reagent, the

modifying phase is strongly and irreversibly adsorbed onto the electrode surface, resulting in the formation of one

or several monomolecular layers [17]. In some cases, bifunctional reagents such as glutaraldehyde, ethylene glycol,

and isothiocyanates can be used to further stabilize the modifier on the surface by forming strong covalent cross-

links between the modifier and the surface, increasing the durability and adhesion of the film. A frequently applied

approach to obtain electrodes with high catalytic activity is modification with polymer films. Electron-conductive

and non-conductive polymer films are adsorbed on the electrode surface by a combination of chemisorption and

low solubility in the electrolyte solution. The polymer can be organic, organometallic, or inorganic, containing the

desired modifier or added at a later stage of the modification [18]. Polymer-modified electrode surfaces can be clas-

sified according to the technique used to deposit the film. Figure 2 summarises chemical methods for modification.

“Dip and Dry or Dip coating”. This represents a simple approach to modifying electrodes by incubating the elec-

trode in a polymer suspension for a sufficiently long time until a film is formed by adsorption processes on the

electrode surface (Fig. 3a). Polymer film thickness can be controlled by incubation time, particle concentration in

suspension, and mass transfer rate [19]. Despite its cost effectiveness and low material consumption rate, dip coating

suffers from a main disadvantage of being a low process, leading to partial or inhomogeneous electrode coverage.

An alternative method to overcome the inhomogeneity problem is spin coating.

„Spin coating”. In this method, thin and uniform films are formed on an electrode surface (Fig. 3b). The methodol-

ogy consists of placing an optimum amount (µl) of the composite phase (a polymer containing a catalyst) on the

surface of the electrode and of centrifuging a desired volume ∼ 2000 rpm, before gradually slowing the rotation

speed down and allowing evaporation of the solvent. Depending on the properties of the modifying phase, the accel-

eration, and the angular velocity of rotation, the film thickness varies in the range of several nanometers to several Vol:.(1234567890)

Discover Electrochemistry (2024) 1:12

| https://doi.org/10.1007/s44373-024-00012-8 Review

micrometers [20]. This is a suitable method for depositing thin films on screen-printed electrodes, which requires

special and expensive equipment.

„Spray coating”. This is another method that can facilitate the deposition of a uniform and thin film with a large elec-

trochemically active surface area (Fig. 3c) [21]. The modifier suspension is sprayed onto the electrode surface with a jet

apparatus using a carrier gas or a nozzle with subsequent evaporation of the solvent. The automated process provides

homogeneous and reproducible surfaces by adjusting the distance between the nozzle and the electrode, thus the

particle size can be controlled. The main disadvantages of this method include a large consumption of materials and expensive equipment.

„Drop coating”. This method is widely used to prepare the surface of chemically modified electrodes by applying a

desired volume of a modifier-containing suspension to an electrode surface, followed by drying under UV [22], under a

N2 [23], or merely room conditions (Fig. 3d) [24]. This method offers the advantages of short production time (∼1 min.

[25]), simplicity, and reusability. The amount of drop-cast modifier can be quantitatively related to the number of mon-

olayers formed on the electrode surface. Disadvantages are related to the possibility of agglomeration, inhomogeneous

coating of particles on the surface, and observation of the "coffee-ring" effect, which refers to the phenomenon where

a droplet of liquid containing suspended particles leaves a ring-shaped stain upon evaporation. This effect occurs due

to the uneven distribution of particles as the solvent evaporates, causing the particles to concentrate at the edge of the

droplet. It is particularly problematic in applications where uniform coating is desired, as it can lead to inconsistencies

in the distribution of catalyst particles after drying. It is related to the distribution of catalyst particles after drying. In a

publication by Kaliyaraj Selva Kumar et al. [26], two approaches are proposed were proposed to address this problem,

such as electrowetting or the use of highly hydrophobic surfaces. Electrowetting enhances the mobility of the catalyst

particles by modifying the wetting properties of the surface, allowing for better dispersion during the drying process.

This results in a more uniform distribution of particles, which is crucial for optimizing catalytic performance. On the other

hand, highly hydrophobic surfaces minimize the adhesion of catalyst particles, preventing agglomeration and ensuring

that they remain well-distributed after drying.

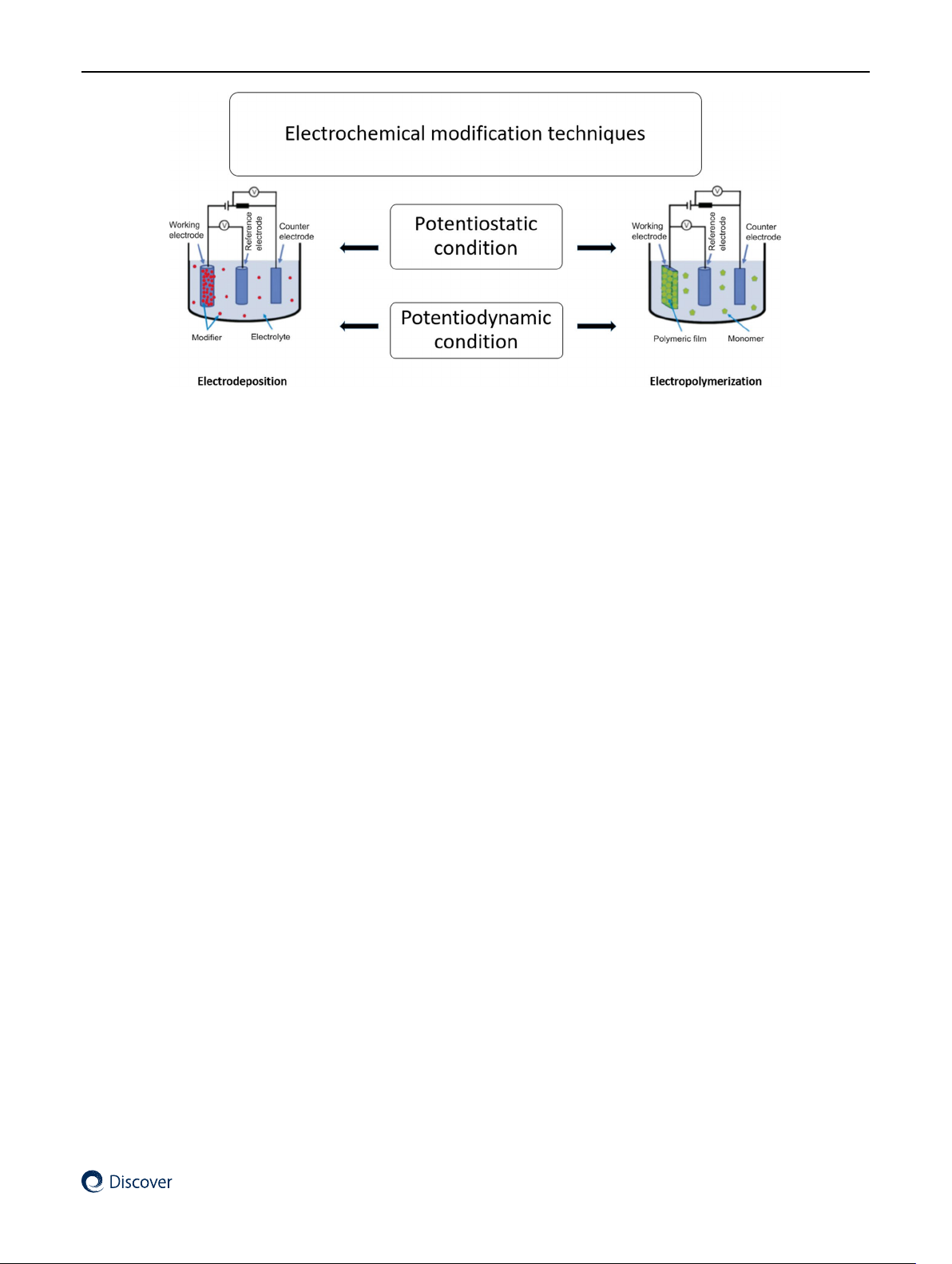

1.4 Electrochemical methods

Electrochemical deposition is one of the most useful approaches for the fabrication of layers on electrode surfaces from

metal nanostructures or polymers. Electrochemical modification techniques can be performed in two different modes,

i.e. under potentiodynamic or potentiostatic conditions, which can be carried out in both aqueous and non-aqueous

media [27, 28]. In the potentiostatic technique, a constant potential is applied between the working electrode and ref-

erence electrode for a desired duration. The applied voltage must be at least 0.15 V more negative than the reduction

peak potential of a targeted metal ion to promote deposition of the surface of the working electrode. Very often, the

sites with defects (e.g., edges, pores) on the electrode surface are where deposition occurs. Depending on the condi-

tions, for example, the type and concentration of the electrolyte bath, the deposition time can vary from a few seconds

to minutes [29]. In contrast, potentiodynamic techniques require a scanning from an initial potential to a final potential

at a particular rate [30]. One usually chooses an initial potential to be at which no electroreduction of metal ions from

the electrolyte occurs on the electrode. Similarly, a final potential is usually where the reduction reaction takes place

at a significant rate. Alternatively, the reduction can proceed at a high speed at the chosen initial potential, and at the

final potential, the metal ions are not reduced on the working electrode. The potentiodynamic modes can be conducted

with voltammetric methods such as cyclic and differential pulse voltammetry [31]. Figure 4 represent electrochemical

methods for modification of electrode surfaces.

Modification of electrode surfaces can also be performed by electropolymerization directly from a monomer solu-

tion added to an inert electrolyte that has been initially deaerated [32]. Usually, the polymerization is carried out in a

potentiodynamic mode in an aqueous medium at a certain pH value [33]. This allows the deposition of a dense thin film

with high adhesion to the electrode surface. Potentiostatic electrolysis is used to a lesser extent in the development of

electrochemically modified electrodes, but is preferable from the point of view of the solubility of the monomer and

polymer form and because of the possibility of obtaining porous coatings [34]. The polymerization medium is also essen-

tial because organic solvents can either enhance or deteriorate the reproducibility of the resulting layer, depending on

their specific properties and interactions during the polymerization process [35].

Electrodeposition of metallic micro- or nanostructures can be performed in two modes of operation, as mentioned

above. The solution used contains salts of the deposited metal (e.g. AgNO3 for Ag) with a very low concentration, typi-

cally in range of 0.1 to 1 mM, which is essential for achieving controlled deposition. Crucial factors for controlling the Vol.:(0123456789) Review

Discover Electrochemistry (2024) 1:12

| https://doi.org/10.1007/s44373-024-00012-8

Fig. 4 Electrochemical methods for modification of electrodes surface

size and shape of the resulting nanostructures during modification are the applied potential, current density, solution

concentration, deposition time, and scan rate [36]. With the use of electrochemical techniques, nanostructures with

targeted (1 nm – 100 nm) sizes, well-defined composition and morphology can be obtained. The advantages are the

absence of unwanted by-products, shorter synthesis time (for example, 3 s [37]), and the negated use of a binder to fix

the particles, which is usually required in the "drop coating" method.

The rapid progress of modern technologies necessitates the inclusion of nanomaterials in the design of electrochemi-

cal devices used for batteries [38], fuel cells [39], water purification [40] and biomedicine [41]. This revolution in scientific

achievements is based on the specific characteristics of nanoparticles such as efficient catalysis, improved mass transfer,

and enlarged electrode surface, arising from the large surface-to-volume ratio. Significant progress has been made in

the synthesis of nanomaterials with controllable morphologies such as spherical, rod-like, and sheet like structures;

sizes ranging from few nanometres to several micrometers; tunable surface charges (positive, negative or neutral); and

adjustable physicochemical properties such as porosity, crystallinity, and surface area [42–44]. Their use as modifiers of

conductive matrices enables the development of new sensitive and selective electrochemical systems [45–50].

1.5 Materials for modifying electrode surfaces

1.5.1 Nanostructured metallic materials

Nanosized metallic materials have been extensively studied due to their characteristics: catalytic and antibacterial activ-

ity, and electronic and magnetic properties [51]. Their use offers additional advantages that are of great importance for

electrochemical research: excellent electrical conductivity, corrosion resistance, high catalytic activity in various reac-

tions, an increase in the electrochemically active surface, biocompatibility and functionalization of their surface with organic molecules [52–54].

Notably, nanostructured metals can be combined in the form of core–shell structures, where the core and shell are

made of different materials [55]. This combination of materials allows their physicochemical properties to be combined,

which in turn improves the electrochemical performance of the devices under development. Nanostructures of noble

metals such as gold (Au), silver (Ag), platinum (Pt), and palladium (Pd) and their bimetallic alloys are often used in the

development of electrochemical devices for various applications. This is due to their physical, chemical, and electrochemi-

cal properties, which vary depending on their sizes and shapes. For instance, smaller nanoparticles exhibit higher surface

area-to-volume ratios, which enhances their catalytic activity in electrochemical reactions. Additionally, the shape of

particles, such as rods, spheres, or cubes, influences their reactivity; rod-shaped particles have been shown to facilitate

faster electron transfer, improving electrochemical performance. Furthermore, specific crystal facets exposed by different

shapes can enhance catalytic efficiency, as demonstrated in studies involving platinum and gold nanoparticles [56–59].

There have hitherto been many publications on silver nanostructure-modified electrodes that exhibited electrocata-

lytic activity towards the electroreduction of various substances [60]. Vol:.(1234567890)

Discover Electrochemistry (2024) 1:12

| https://doi.org/10.1007/s44373-024-00012-8 Review

In the last two decades, researchers’ efforts have been focused on the development of new electroanalytical devices

for quantitative and qualitative determination of various substrates such as markers of severe diseases, presence of

biological and infectious agents for early-stage disease detection based on silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) [61] and their

nanocomposites [61]. For instance, AgNPs have been successful y integrated into electrochemical sensors for the detec-

tion of dopamine in human serum, achieving a detection of limit as low as 7 nM, demonstrating selectivity and stability

[56]. Furthermore, Ag-based nanocomposites have demonstrated significant potential in the detection of hydrogen

peroxide, exhibiting a high sensitivity of 8.9273 µA µM⁻1 cm⁻2 and low detection limit of 0.23 ± 0.012 µM. These proper-

ties make them highly valuable for applications in healthcare safety and environmental monitoring [62].

Carbon core and silver shell nanocomposite (Ag@C) doped with nickel (Ni) have been used to modify a glassy carbon

electrode [63]. The electrochemical behavior of the nanocomposite Ni/Ag@C demonstrated good electrocatalytic activity

in the reduction of H2O2, in a wide linear range from 0.03 mM to 17 mM. Another type of electrocatalyst for hydrogen

peroxide reduction was created based on AgNPs embedded on the surface of carbon quantum dots (CQDs). The modifica-

tion of a GCE was carried out by the "drop casting" method [64]. According to the authors, the achieved results show that

AgNPs embedded in CQDs are promising electrocatalysts for the reduction of H2O2, which can be attributed a 1.5-fold

larger quantity of AgNPs dispersed in the nanocomposite, compared to similar AgNPs—only systems.

Moreover, quantitative electrochemical investigations revealed that the AgNPs/CQDs nanohybrid sensor exhibited

a high sensitivity of 1.5 μA/μM, a detection limit of 80 nM, and a linear range from 0.2 to 27.0 μM for H2O2 detection.

These parameters clearly demonstrate the superior electrocatalytic performance of the AgNPs/CQDs nanocomposite compared to other materials.

In another study [65], tannic acid was coated on AgNPs—decorated magnetic Fe3O4, where tannic acid has been

used as a stabilizing and reducing agent for silver ions, via interaction of its hydroxyl and ketone groups with silver ions: C H O (tannic acid) + Ag+ 76 52 46

→ AgNPs + Oxidized tannic acid (1)

The modified electrode was used for the electrochemical determination of the ecologically toxic 4-nitrophenol. Accord-

ing to the authors, the high sensitivity of the signal during the reduction of the analyte is related to the effectiveness of

the nano-hybrid. The sensitivity of the electrode was measured with a detection limit of 33 nM and a wide working range

from 0.1 to 680.1 μM, indicating a significant improvement compared to other systems. These data demonstrate that the

nano-hybrid has high efficiency in electrochemical detection and catalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol.

The development of electrochemical devices by modifying electrode surfaces with platinum nanomaterials has

attracted the attention of scientists due to their distinctive electronic and electrocatalytic properties [66]. Platinum

nanomaterials exhibit exceptional conductivity, high stability, and catalytic activity in various electrochemical reactions,

such as hydrogen or methanol oxidation and oxygen reduction [67]. For example, platinum nanoparticles demonstrate

significantly lower overpotentials in the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR),

making them ideal for fuel cells and other electrochemical applications [68]. The uniform distribution of nanomaterials

on the electrode surface can be related to the stability of the colloidal suspension used. In this context, the colloidal

suspension refers to the dispersion nanoparticles in liquid medium, which is essential to achieve an even coating on

the electrode surface. Stabilizing reagents such as surfactants are used to prevent the agglomeration of PtNPs in the

colloid-dispersed systems, which would lead to uneven coatings [69]. Although PtNPs are characterized by selectivity and

sensitivity for many electrochemical reactions, they have two significant drawbacks—scarcity and high cost. Combining

them with other nanomaterials reduces cost and extends their electrocatalytic properties. Shahid et al. used the "drop

casting" technique to modify a glassy carbon electrode with a nanocomposite of reduced rGO, cobalt oxide (Co3O4)

nanocube, and platinum [70]. The studies showed that the modified electrode demonstrated excellent catalytic activity

in the electrochemical oxidation of nitric oxide, represent by the reaction: NO + H O + 2H+ + e− 2 → NO− 2 (2)

This catalytic performance was quantitatively demonstrated by the shift in oxidation potential to + 0.84 V and an

increased peak current of 119 µA, indicating superior electron-transfer kinetics at the modified electrode surface. The

authors attributed this enhanced activity to the synergistic effect between the Co3O4 nanocubes, platinum nanoparti-

cles, and rGO. Specifically, Co3O4 nanocubes provided a large surface area for the deposition of Pt nanoparticles, while

Pt nanoparticles enhanced electron transfer and reduced the overpotential. The rGO matrix further facilitated charge

transfer and prevented the agglomeration of Co3O4 nanocubes, thereby contributing to the overall improved catalytic performance. Vol.:(0123456789) Review

Discover Electrochemistry (2024) 1:12

| https://doi.org/10.1007/s44373-024-00012-8

Gold nanoparticles and their nanocomposites are widely used in the field of electrochemical research, due to the fol-

lowing advantages: (1) simple preparation methods; (2) increasing the electrochemically active surface area; (3) biocom-

patibility; (4) electrochemical stability over a wide range of potentials (typically from −0.2 V to + 1.2 V vs. Ag|AgCl), and

(5) high catalytic activity [71]. Additionally, their high catalytic activity is demonstrated through their ability to enhance

electron transfer rates in various electrochemical reactions. Al these properties provide the possibility of miniaturization

of electrochemical devices, fast response, and high sensitivity [72]. Au-based nanomaterials have hitherto been report-

edly used in the development of electrochemical devices for the detection of analytes, such as hydrogen peroxide [73],

metal ions [74], organic compounds [75], and others.

Won et al. reported that the performance of electrochemical catalysts can be potentially affected by Au morphology

nanocrystals [76]. They found that electrodes modified with Au nanospheres and Au nanorods have similar characteristics

in terms of limit of detection of H2O2, but the Au nanorod-coated electrode exhibits a higher sensitivity (58.51μA mM−1)

due to the smaller number of interfacial boundaries between the nanorods. A Au nanocage-modified GCE also exhibited

a 4.4 times increase in electrochemically active surface area, which has in turn improved the detection sensitivity by

5.3 times [77]. In addition, there was a ~ 2-s response time, which is most likely due to the hollow structure of the cage

facilitating the diffusion of the analyte to the surface.

A synthetic method for obtaining bimetallic Au/Ag (core/shell) nanorods, embedded in an amino-functionalized sili-

cate sol–gel matrix (Au/Ag-N1-[3-(trimethoxysilyl)propyl]diethylene triamine nanords) in an aqueous medium, applied

in the electrochemical detection of hydrogen peroxide and nitrite ions, was developed. The amperometric electrode

was used to detect the analytes at physiological pH, without the need for a mediator, which the authors attributed to the

synergistic effect between the Au core and the Ag shell [78]. Specifically, Au provides excellent conductivity and stabil-

ity, while Ag enhances the electrocatalytic activity, particularly in the reduction of hydrogen peroxide. This combination

improves the electrode’s performance, allowing for efficient detection of these analytes under physiological conditions.

In addition to high catalytic activity and improved conductivity, metal nanoparticles are often able to retain a bioele-

ment in proximity close to the electrode surface [79]. Strategies to achieve this are based on (i) physical interactions,

such as electrostatic attraction, which can enhance the binding affinity between the nanoparticle and the bioelement;

(ii) chemisorption of sulfur-containing organic compounds on Au, Ag, and Pt nanostructures, which forms strong bonds

that improve the stability of the bioelement on the surface [80]; and (iii) the formation of covalent bonds, which provide

a robust attachment of the bioelement to the electrode, enhancing the overall detection sensitivity [81]. For instance,

studies have shown that using specific thiol compounds can significantly increase the retention of enzymes on gold

nanoparticles, resulting in improved catalytic performance.

Despite all the advantages, electrochemical devices face several limitations, such as moderate selectivity in the analysis

of some real-life samples and lack of reproducibility of measurements. In an attempt to overcome these drawbacks in

recent years the range of materials that are used to modify electrodes has been constantly expanding.

1.6 2D carbon nanomaterials

After the breakthrough discovery of single-layer graphene in 2004 [82], 2D carbon nanomaterials have attracted the atten-

tion of many researchers in various fields ranging from electronics to biomedicine [83]. Their unique catalytic properties

and high surface-to-volume ratio make them suitable for a wide range of applications, such as environmental catalysis

[84], drug delivery carriers [85], and sensing and energy applications [86]. These nanomaterials are often combined with

other materials to form nanocomposites that significantly improve the sensitivity (for example, x-fold, depending on the

system used [87]) and selectivity of modified surfaces, as a result of the synergistic effect between them. The enhanced

selectivity is primarily due to the specific surface functional groups and tunable electronic properties of 2D carbon

nanomaterials, such as graphene and its derivatives, which allow for targeted interaction with specific analytes [88]. In

addition, they can be functionalized with biomolecules, which effectively improves conductivity, mechanical stability, and direct electron transfer.

Graphene is a single-layer carbon material composed of carbon atoms in the sp2—hybridized state, which has a

large specific surface area (theoretically, it is 2630 m2 g−1), a high electron transfer rate (15,000 cm2 V−1 s−1), exceptional

mechanical strength (Young’s modulus ~ 1 TPa and tensile strength up to 130 GPa) and excellent thermal and electrical

conductivity (~ 5000 W/m·K for thermal conductivity and over 6000 S cm−1 for electrical conductivity) [89]. These proper-

ties make it an attractive material for the production of modified electrodes for various electroanalytical applications [90].

However, graphene is hydrophobic and tends to form agglomerates, which hinders its further application in electrochemi-

cal research. The absence of surface functionality and low solubility in water, as well as in most organic solvents, limit its Vol:.(1234567890)

Discover Electrochemistry (2024) 1:12

| https://doi.org/10.1007/s44373-024-00012-8 Review

practical application. To address these limitations and to improve the mechanical stability, electrochemical active surface,

and signal sensitivity, graphene is often combined with AuNPs or electrodeposited polymers such as polypyrrole [91].

Graphene oxide (GO) consists of a hexagonal carbon network with oxygen-containing functional groups combined

with non-oxidized regions where most of the carbon atoms are in sp2 hybridization. The high content of functional groups

in the form of hydroxyl and epoxy parts at the base of the plane and carboxyl groups at the edges of the sheet make it

highly hydrophilic [92]. Therefore, it is easily dispersed in water, thus facilitating the modification of electrode surfaces,

for example, by the “drop casting” method [93]. GO is an excellent platform for covalently immobilizing bio-receptors

due to its oxygen-containing functional groups and large surface area. However, predominant functional parts of GO

result in insulating properties, which is a significant disadvantage. In this respect, GO is often electrochemically reduced

to lower the number of oxygen-containing groups on the surface. This process enhances its electrical conductivity by

converting GO to rGO [85] through the following reaction: GO + H+ + e− → rGO + H O 2 (3)

Electrochemically prepared rGO sheets show a smaller O/C ratio (0.1–0.3) and are more conductive (500 – 10 000 mS

m−1) compared to those obtained by chemical methods (0.3–0.6 and 50–500 mS m−1) [86]. The oxygen-containing func-

tional groups must be properly balanced. To achieve the optimum effectiveness of the modifier, it is crucial to enhance

both its stability and conductivity. On the other hand, modification of electrode surfaces with composites of rGO and

nanoparticles of metal or/and metal oxides demonstrates excellent reproducibility (with relative standard deviation

values typically below 5% in repeated measurements) and electrical conductivity (with conductivity values reaching up

to ~ 104 S cm−1), for example, in the electrochemical determination of heavy metal ions [94].

It has been established that the most effective approach to improving the electrocatalytic activity of carbon materials

is the addition of nitrogen atoms [95]. Carbon nitride-based compounds with a high N:C ratio (typically around 0.75 or

higher) are new-generation materials that are used to develop electrocatalysts [96]. Carbon nitrides reveal different crystal

structures, for example, tetrahedral carbon nitride (β-C3N4) and graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4). The β-C3N4 material

has high hardness of approximately 60 GPa and low compressibility, with a bulk modulus of about 400 GPa, similar to

diamond. In contrast, g-C3N4 is considered the most stable under ambient conditions and exhibits a lower hardness of

around 2–3 GPa and a bulk modulus of approximately 20–30 GPa [97]. g-C3N4 is a non-metallic, graphene-like 2D material

comprising mostly covalent bonds (CN), forming a π- π-conjugated polymer with a high molecular weight and a unique

electronic structure predetermining its semiconductor properties [98]. The 2D structure of g-C3N4 is composed of tri-s-

triazine units, possessing a high degree of condensation, which regulates its high thermal and chemical stability [99].

Therefore, g-C3N4 is regarded as a multifunctional, heterogeneous, non-metallic catalyst [100] whose main drawback is

the poorly developed specific surface area. Melamine has been reported to be successfully used as a precursor for they

synthesis of g-C3N4 [101] due to its low cost and toxicity while providing increased surface area and pore volume. Another

approach to increase the specific surface area of g-C3N4 is doping it with oxides of transition metals in the form of an

ultrafine dispersion, which are distributed between the nanosheets of g-C3N4 and prevent their agglomeration [102].

1.7 Transition metal oxide nanoparticles

Transition metal oxides (TMOs) possess good electrical and photocatalytic properties due to their size, shape, and larger

surface area [103]. The excessive scientific interest in developing electrocatalysts with TMOs nanoparticles is due to their

thermal stability, radiation resistance, and environmental safety [104]. The main drawback is the large energy bandgap

(Eg > 3 eV) makes them semiconductors and insulators [105]. This limitation can be minimised by conjugating the nano-

particles with a carbon matrix or other metallic nanostructures.

Among metal oxides, iron oxide (Fe3O4) nanoparticles have attracted attention in various electrochemical applica-

tions. They are highly desirable due to their biocompatibility, non-toxicity, thermal stability, and optical and magnetic

properties [106, 107]. These nanoparticles can effectively modify electrodes for the electrochemical detection of several

compounds. The exchange of electrons between Fe2+ and Fe3+ makes Fe3O4 nanoparticles an excellent electrical conduc-

tor even at room temperature [108]. To enhance their selectivity and sensitivity, they are often combined with metals

such as nickel [109], cobalt [110], silver [111] and others.

Iron oxide nanoparticles are dispersed in carbon matrices like graphene [112], GO [113], and carbon nanotubes [114],

to obtain different nanocomposites. The carbon matrix acts as a supporting medium for the homogeneous dispersion

of nanoparticles, prevents their aggregation, and gives a high surface/volume ratio (∼200 m2 g−1). Their use as electrode Vol.:(0123456789) Review

Discover Electrochemistry (2024) 1:12

| https://doi.org/10.1007/s44373-024-00012-8

modifiers increases the electroactive surface area, which improves signal selectivity and sensitivity. Another modifier

used is titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles, which are electrically conductive, chemically stable in both alkaline and

acidic medium, and are relatively cost effective [115]. Recent studies highlight that TiO2-based nanostructures, par-

ticularly non-stoichiometric variants like TiO2-X, demonstrate enhanced sensitivity and selectivity in gas sensors due to

their unique electronic properties [116]. Furthermore, TiO2-X heterostructures have been shown to reduce energy con-

sumption in sensors by operating in a ’self-heating’ mode, improving efficiency in gas and volatile organic compound

detection. The presence of surface active centers makes them a promising material for modifying various electrodes

for many electrochemical applications [117, 118]. The main disadvantages in developing electrochemical devices from

TiO2 alone are the low solubility of the nanoparticles and the instability of the film on the electrode surface, which often

leads to low sensitivity [108]. To overcome this issue, titanium oxide particles are combined with GO [119], AuNPs [120],

quantum dots, etc. This approach combines their catalytic properties to obtain new electrocatalysts with high selectiv-

ity and sensitivity in electroanalytical practical applications [121]. Selectivity of a TiO2-coated electrode refers to the

electrode’s ability to recognize and react with a specific analyte in the presence of other interfering substances. In the

context of electrochemical systems, this means that the TiO2 coating enhances the catalytic activity of the electrode

in a way that allows for selective detection of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or other target analytes, while minimizing the

effect of unwanted reactions with other compounds in the sample. The reaction of H2O2 on a TiO2-modified electrode can be represented as follows: TiO + H O + 2H+ + 2e− + O 2 2 2 → TiO2 2 (4)

Among the transition metal oxides, a very promising catalyst exhibiting high catalytic activity and stability in several

electrochemical reactions are the oxides of Co (II and/or III) with a spinel structure, particularly Co3O4 [122]. Different

synthesis techniques of cobalt oxide nanoparticles such as electrodeposition [123], chemical methods [70], green syn-

thesis [124], and calcination [125], have already discussed, which help control the size and shape of the nanoparticles.

A study [126] reported a H2O2 electrochemical sensor based on cobalt oxide nanoparticle | electrochemically rGO | GCE.

It was found that the inclusion of spinel Co3O4 between the sheets of g-C3N4 significantly affects their structure: the

specific surface area of carbon nitride doped with metal oxide is much higher than that of pristine g-C3N4, increasing

from 0.0025 cm2 to 0.097 cm2 [127], which may be due to the high dispersion of Co3O4 between the g-C3N4 layers, which

prevents particle agglomeration. The Co-g-C3N4 composite shows high activity and good results in the catalytic activa-

tion of peroxymonosulfate compared to pure Co3O4 [128].

1.8 Polymer films and enzymes

Conducting polymers such as polypyrrole (Ppy), polyaniline (PANI), polythiophene (PTH), and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxy-

thiophene) (PEDOT: PSS) are essential in the development of electrochemical sensors and biosensors due to their excel-

lent electrochemical properties, conductivity, and biocompatibility. These materials are widely recognized for their role

in improving the performance of analytical and bioanalytical systems, as outlined in reviews like [129]. The application

of conducting polymers, especially when electrochemically deposited on electrode surfaces, enhances sensor perfor-

mance by providing controlled film thickness, morphology, and high surface area, which significantly improves sensor

sensitivity and selectivity. Electrochemically deposited conducting polymer films can immobilize biological molecules

such as enzymes and antibodies, enhancing the electrochemical response of the sensor. As discussed by Ramanavicius

et al. [130], molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) enable the devolpment of highly selective sensor systems tailored

for specific analytical applications, providing an efficient and cost-effective alternative to conventional recognition ele-

ments such as antibodies and receptors by offering customizable recognition sites for target molecules. A major area

of advancement in electrochemical sensors is the improvement of charge transfer between redox-active enzymes and

electrodes, achieved through the use of conducting polymers. Polymers such as PEDOT: PSS and Ppy have demonstrated

their ability to facilitate efficient electron transfer in enzymatic systems like glucose oxidase (GOx)-based sensors. Dis-

cussions examining the aspects of charge transfer and the biocompatibility of conducting polymers used in enzymatic

biosensors and biofuel cells highlight key points regarding the charge transfer process. Additionally, emphasis is placed

on the biocompatibility of these materials, further supporting their application in fields such as biosensors and biofuel

cells [131]. These materials not only enhance electron transfer but also act as excellent immobilization matrices, improv-

ing the overall sensitivity and stability of enzymatic biosensors. Vol:.(1234567890)

Discover Electrochemistry (2024) 1:12

| https://doi.org/10.1007/s44373-024-00012-8 Review

Another important development in the field is the use of molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) for sensor design.

MIPs create specific recognition sites for target molecules, significantly improving sensor selectivity. A comprehensive

overview of how these polymers can be integrated into sensor systems to enhance analytical performance is provided

in the review discussing advances in MIPs-based affinity sensors. The combination of conducting polymers and MIPs

presents a promising approach for developing highly selective and sensitive electrochemical sensors.

The integration of electrochemically deposited conducting polymers and MIPs offers significant potential for improv-

ing the performance of electrochemical sensors and biosensors in a variety of fields, including biomedical diagnostics,

environmental monitoring, and food safety [132]. The researchers provide a solid foundation for future research and

development in this area, highlighting the ongoing advancements in charge transfer mechanisms, biocompatibility,

and material optimization that will continue to drive progress in sensor technology.

1.9 Electroanalytical applications

Globally, the development of sensor devices is developing dynamically, which is due to the diversity and constant tech-

nological improvements. Electrochemical sensors provide a practical solution for analyte detection and are widely used

in agriculture, food, and petroleum industries and environmental and biomedical applications (Fig. 5) [133]. For over

two decades, many nanomaterials with exceptional characteristics, such as metals, conducting polymers, metal oxides,

and carbon nanomaterials, have been used to construct electrochemical sensors to improve analytical results. Important

features determining the potential of electrochemical devices for practical application are low detection limits, typically

in the range of nanomalar concentrations (e.g. 1–10 nM), high sensitivity, often exceeding 100 µA mM of analyte con-

centration selectivity, and fast analytical response [134].

The development of electrochemical sensors has vast potential applications in the fields of nutrition and wellness.

Electrochemical sensors can be used to detect essential biomarkers related to nutritional status, such as glucose, vitamins,

minerals, and oxidative stress markers, which are critical in evaluating human health and wellness [135]. These sensors

provide quick, sensitive, and accurate quantification, making them ideal for monitoring dietary intake and metabolic health in real-time.

In food science, sensors are employed for the detection of contaminants, nutritional content analysis, and assessing

the freshness and safety of food products. For example, the detection of hydrogen peroxide in food matrices is crucial

for ensuring the safety and quality of perishable goods such as juices and dairy products [136]. The advancement of

electrochemical sensors can contribute significantly to personalized nutrition by offering tailored insights based on

individual biochemical feedback.

Peroxide compounds are used in many industries and can be found in various living cells, but they are dangerous

and toxic when the concentration exceed > 10–35% [137]. H2O2 is the simplest peroxide that exhibits oxidizing and

reducing properties at different pH values and is often used as a marker for oxidative stress analysis [138]. Oxidative

stress is believed to be a biomarker of many life-threatening diseases including atherosclerosis [139], diabetes [140],

cancer [141], acute myocardial infarction [142], and others [143]. In addition, H2O2 is a byproduct of reactions catalyzed

by most oxidase enzymes, such as glucose oxidase, cholesterol oxidase, and lactate oxidase [144, 145]. In the food and

paper industry, H2O2 is often utilized for its bactericidal and bleaching properties. However, it is important to note that

the strong oxidizing power of H2O2 can pose potential safety risks to human health. Prolonged exposure to H2O2 may

cause damage to the skin and organs, making it important to handle with care.

Fig. 5 Schematic representa- tion of the electrochemical applications Vol.:(0123456789) Review

Discover Electrochemistry (2024) 1:12

| https://doi.org/10.1007/s44373-024-00012-8

Waifalkar et al. [146], developed an electrocatalyst consisting of magnetic Fe3O4, graphene, H2O2 for the cyclic volta-

metric determination of hydrogen peroxide. The electroreduction of the analyte was observed at a potential of -0.8 V (vs.

SCE) with a very good sensitivity of 48.08 µA µM−1 cm−2 in the concentration range from 0 to 100 µM. By quantitatively

determining hydrogen peroxide in real-life orange juice samples, a recovery of ∼ 99% (relative standard deviation)

was estimated, indicating minimal interference by the orange juice matrix. The recovery was felicitated by the enzyme

horseradish peroxidase (HRP). The study was conducted on natural orange juice samples to verify the applicability of the

modified electrode for the determination of hydrogen peroxide. Studies were made in real samples of natural orange

juice for determination of hydrogen peroxide to verify the applicability of the modified electrode. The measured amounts

of H2O2 are very close to the values of the added concentrations, and according to the authors, the orange juice matrix

does not interfere with the hydrogen peroxide reading. In another study, a Nafion | Pd@Ag bimetallic nanoparticles |

(3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane functionalized rGO-immobilised GCE used to amperometrical y detect hydrogen peroxide

was demonstrated to show a fast response time of 2 s and a sensitivity of 1307.46 µA µM−1 cm−2 [147]. Electrochemical

reduction of the analyte was carried out at a constant potential of −0.45 V with a linear range from 0.002 to 15.90 mM

and a detection limit of 0.7 µM. The modified electrode demonstrated excel ent stability, retaining approximately 93.4%

of its initial current response after 30 days, highlighting its practical applicability in real-life sample analysis. Analysis was

performed to determine known concentrations of H2O2 in cow milk with a recovery rate between 96.76 and 102.42%

Cyclic voltammetry and amperometric detection were used to study the electrochemical reduction of hydrogen per-

oxide on an electrode coated with hollow carbon spheres and electrodeposited PtNPs [148]. The authors attribute the

high electrocatalytic sensitivity (42.8 µA µM−1 cm−2) and low detection limit (6.25 μM) to the combined effect of these

modifiers. The peroxide electrode has been used successfully to determine the concentration of H2O2 in samples of a

solution in which seafood has been immersed.

The detection of hydrogen peroxide released from living cells requires the development of electrocatalysts that are

highly sensitive and selective. In this regard, new atomic-thick PtNi nanowires have been synthesized and attached to

reduced carbon oxide through an ultrasonic method [149]. The GCE modified with the nanocomposite material shows

good performance in H2O2 quantification in a wide range of concentrations from 1 nM to 5.3 mM (detecting a minimum

of 0.3 nM) at an applied potential of -0.6 V (vs. Ag|AgCl). Furthermore, the atomic-thick PtNi nanowires provide high-

density active sites and facilitate efficient electron transfer, enhancing the selective detection of H2O2 while minimizing

interference from substances such as fructose, glucose, ascorbic acid, and uric acid, commonly present in biological

medium. The selectivity of the amperometric electrode is an indication of its practical applicability for the detection of

hydrogen peroxide released by cancer cells.

Many diseases are linked to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide radicals, hydroxyl

radicals, and hydrogen peroxide. This imbalance between the ratio of oxidants and antioxidants (in favour of oxidants)

in living cells leads to oxidative stress. Neurotransmitters can also serve as an indicator of the amount of oxidative stress

in human metabolism. Therefore, monitoring these compounds has become increasingly important in recent years in

medical and environmental applications [150]. Conventional methods of measuring these compounds, including spectro-

photometry and chromatography, are time-consuming and expensive. An alternative possibility for quick, real-time, and

highly accurate quantification of catecholamines is to use electrochemical techniques and to develop electrochemical

sensing devices that include a biological element (such as an immobilized enzyme) and a signal transducer.

A major problem with an electrochemical enzyme sensor is an efficient electron transfer rate between the active

centre of an enzyme and the electrode surface. The development of enzyme electrodes by combining nanomaterials

and bioelements has several advantages: excellent electrical conductivity, with electron transfer rates increased by up

to 100-fold compared to traditional materials, a large electrochemically active surface area (e.g. up to 150 m2 g−1), and

reduced electron transfer resistance (often deceased by up to 50%) [151]. A new enzyme electrode based on a (AuNP,

MoS2, Nafion, or laccase)-modified GCE was developed for the determination of catechol [152]. The electrocatalytic

current was found to increase proportionally with increasing analyte concentration over a wide linear range (from 2 to

2000 µM) and a relatively low detection limit (2 µM). The authors hypothesize that the low detection limit is a result of the

excellent conductivity and electrocatalytic properties of the AuNPs, which enhance electron transfer and facilitate the

enzymatic reaction, thereby improving the sensitivity of the biosensor. Two different strategies for the quantification of

serotonin and dopamine were recently reported [153], where poly(2,6-bis(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-4-methyl-4-octyl-

dithienosilol) and laccase-modified Pt electrode was developed to detect serotonin, and a poly(2,6-bis(selenophen-

2-yl)-4-methyl-4-octyl-dithienosilol) and horseradish peroxidase-modified Au electrode for detecting dopamine. These

silole derivative and oxidoreductase-based enzyme electrodes show high selectivity owing to enzyme specificity and

electroconducting polymer structure, and high reproducibility (± 3.9–0.88% relative standard deviation). According to Vol:.(1234567890)

Discover Electrochemistry (2024) 1:12

| https://doi.org/10.1007/s44373-024-00012-8 Review

the authors, the characteristics of both systems allow the development of a disposable biosensor for in vitro use or in situ applications.

Rubio-Govea et al. [154] developed an amperometric dopamine biosensor based on 2D layered MoS2 and LacII-

modified carbon paper electrodes (where LacII denotes a type of laccase). By applying the LacII-modified electrodes to

the determination of dopamine in a synthetic urine sample, a detection limit of 0.67 µM was estimated, which is below

the average dopamine concentration (~ 2 µM) typically found in real-life urine samples. However, further research is

required to facilitate the application of the biosensor to real-life sample analysis.

Coelho et al. [155] developed a laccase-loaded botryospherane film multiwalled carbon nanotube-immobilised GCE,

which showed excellent selectivity towards dopamine and spironolactone owing to he high sensitivity (linear range

of 2.99–38.5 μmol L−1 and detection limit of 0.127 μmol L−1 for dopamine) and selectivity of the biosensor, even in the

presence of interfering species including ascorbic acid, uric acid and phenolic compounds. The enzyme electrode is

characterized by excellent selectivity towards dopamine and spironolactone, with limit of detention of 0.94 µmol L−1

for spironolactone, despite the influence of side analytes. The developed system demonstrates sensitivity, stability, and

good intraday reproducibility, as well as the possibility of long-term storage. It has been successfully applied to quantify

dopamine in pharmaceutical and biological samples.

The electrocatalytic oxidation of dopamine on an electrode modified with CQDs and immobilized laccase was studied

by differential pulse voltammetry [156]. The large specific surface area of CQDs provides many catalytic centers on the

electrode surface, which facilitates electron exchange between the enzyme and the electrode. The electrocatalytic activity

of the laccase electrode showed a low detection limit of 0.08 µM and a wide linear concentration range of 0.25–76.81 µM.

The obtained analytical recovery of 101.9–103.5% with a standard deviation of 0.53% to 1.01% shows that the method

is acceptable for the determination of catechol in a complex environment of human serum.

By electropolymerization of pyrrole on a Pt electrode with subsequent immobilization of laccase, an amperometric

electrode for the quantification of epinephrine was developed [157]. Quantitative analysis of catecholamine was per-

formed by electrochemical reduction of enzymatically produced (generated) epinephrine-quinone at a constant poten-

tial of −0.220 V (vs. Ag|AgCl). The developed enzyme electrode demonstrated good analytical parameters, including a

low detection limit of 0.01 µM, high linearity over a wide concentration range (R2 = 0.998 for 0.1–1.0 µM, R2 = 0.995 for

1.0–10.0 µM), good reproducibility with 5.08% RSD after 31 measurements, and a stable response over 10 days, retain-

ing 80.9% of its initial response. The sensor was used for the determination of epinephrine in an antibiotic drug. A main

drawback is a 200-s duration for the sensor to reach a steady-state signal.

Dopamine and epinephrine are structurally similar catecholamines that play the role of neurotransmitters for clinical

diagnosis, whose elevated or decreased levels in blood plasma or urine often indicate pathological conditions such as

tumors or serious neurological disorders [158]. Both catecholamines, dopamine, and L-epinephrine, are organic sub-

stances of pharmaceutical importance, as both compounds are marketed in the form of injectable solutions. Therefore,

the development of rapid and sensitive methods for their quantification is of important practical importance for the

pharmaceutical industry. In addition, both catecholamines are prone to rapid degradation even when exposed to air for

a short time. Despite the importance of NTs for clinical diagnosis, existing quantification methods still need improve-

ments in terms of selectivity [159], sensitivity, flexibility, and simplification [160]. In an attempt to minimise the limita-

tions inherent in routinely used diagnostic methods for the determination of catecholamines, such as chromatography

[161, 162], chemiluminescence [163], electrophoresis [164], or electroanalysis with chemically modified electrodes have been proposed [165–168].

Conventional analytical techniques lack the advantages of electrochemical techniques, which include device minia-

turization, fast response, high sensitivity, and good selectivity. Electrochemical techniques are also suitable for detecting

neurotransmitters in the presence of mixtures of other molecules with high temporal resolution. Electrochemical sen-

sors can be incorporated into portable devices for targeted applications in diagnostic and clinical fields as biomarkers

of some diseases, e.g. Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s [169, 170].

Alvarez et al. [171] reported a specific, selective, and sensitive RNA-based dopamine aptasensor showing a submicro-

molar detection limit. Recently, various enzymatic catecholamine biosensors using monoamine oxidase [172], cellobiose

dehydrogenase [173], and pyrroloquinoline quinone-dependent glucose dehydrogenase [174] have also been reported.

Josypčuk et al. studied the conditions of four biosensors in a flow-injection system with mini reactors filled with dif-

ferent mesoporous powdered SiO2 covalently linked with the enzymes laccase and tyrosinase (polyphenol oxidases)

for the determination of catechols [175]. Utilizing an injector, a sample of the corresponding catecholamine was trans-

ported to the enzyme reactor, where the substrate was oxidized to a quinone by the immobilized polyphenol oxidase.

At a constant potential, the quinone was electrochemical reduction to form of current response, which enhanced the Vol.:(0123456789) Review

Discover Electrochemistry (2024) 1:12

| https://doi.org/10.1007/s44373-024-00012-8

detection signal. The reduction peak current was found to be directly proportional to the catecholamine concentration of the injected sample.

1.10 Challenges and perspectives

The development of new materials and modification methods for electrodes remains central to modern electroanalysis.

Nanomaterials like graphene, gold, and silver nanoparticles show great promise in improving the sensitivity and selec-

tivity of electrochemical sensors, but several key challenges must be addressed to advance the field. One major chal-

lenge is miniaturization and portability. The growing demand for smaller, wearable devices, such as implantable medical

sensors and smartwatches, calls for innovations that enable continuous monitoring. However, ensuring the necessary

accuracy and stability in these miniaturized systems is technically difficult, particularly with issues like environmental

interferences and power efficiency. Green synthesis is another priority, as traditional methods often use toxic chemicals

and energy-intensive processes. Future research will focus on sustainable, eco-friendly production methods, including

the use of biocompatible reducing agents and renewable resources, ensuring that new materials are both effective and

safe for the environment and human health. The durability and stability of modified electrodes are also critical. Many

nanomaterial-based electrodes face degradation when exposed to real-world conditions with strong interferences.

Developing more robust materials that maintain performance in harsh environments—such as extreme pH or salinity—is

essential. Conductive polymers hold particular promise here, offering improved stability, conductivity, and mechanical

strength as protective coatings or matrices for nanomaterials. In biosensors, achieving efficient electron transfer between

biomolecules and electrodes remains a challenge, limiting overall performance. Polymer-nanoparticle hybrids and con-

ductive polymer films are being explored to improve electron transfer and enzyme stabilization, which are essential for

longer sensor lifetimes and better response times. Reproducibility and scalability also present significant challenges, as

sensors that perform well in the lab often exhibit variability when scaled for industrial production. Standardizing fabrica-

tion methods and maintaining quality control will be crucial for commercial success.

Finally, cost-effectiveness remains a key issue. While noble metals like gold and silver enhance sensor performance,

their high cost limits large-scale manufacturing. To mitigate this, future efforts will focus on combining cheaper alterna-

tives, such as graphene and carbon nanotubes, with small amounts of noble metals and polymers, creating sensors that

balance high performance with affordability and scalability. 2 Conclusions

The future of electroanalysis lies in the continuous advancement of materials and sensor technologies to overcome the

current challenges in sensitivity, selectivity, and durability. Researchers are working to develop cost-effective and sustain-

able methods for synthesizing nanomaterials and improving the design of electrochemical sensors.

Key focus areas include the miniaturization of devices for wearable applications, enhancing electrode stability in com-

plex environments, and increasing the reproducibility of sensors for commercial use. The development of more robust,

portable, and eco-friendly sensors will significantly impact various fields, from medical diagnostics to environmental monitoring.

Overal , interdisciplinary col aboration between materials science, chemistry, and engineering wil be crucial for unlock-

ing the full potential of electrochemical sensing technologies in the future.

Acknowledgements The author gratefully acknowledges the support from the Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Science under the National

Program “Young Scientists and Postdoctoral Students – 2”.

Author contributions M.P. conducted the entire process of writing the review article, including conceptualization, literature research, analysis,

and synthesis of the collected information, as well as drafting the text. M.P. also prepared all tables and figures and reviewed and approved the final version.

Data availability No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study. Declarations

Competing interests The authors declare no competing interests. Vol:.(1234567890)

Discover Electrochemistry (2024) 1:12

| https://doi.org/10.1007/s44373-024-00012-8 Review

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adapta-

tion, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source,

provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article

are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in

the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will

need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. References

1. Apak R, Çekiç SD, Üzer A, Çelik SE, Bener M, Bekdeşer B, Can Z, Sağlam Ş, Önem AN, Erçağ E. Novel spectroscopic and electrochemical

sensors and nanoprobes for the characterization of food and biological antioxidants. Sensors. 2018. https:// doi. org/ 10. 3390/ s1801 0186.

2. Will-Cole AR, Hassanien AE, Calisgan SD, et al. Tutorial: Piezoelectric and magnetoelectric N/MEMS - materials, devices, and applications.

J Appl Physi. 2022. https:// doi. org/ 10. 1063/5. 00943 64.

3. Scozzari A. Electrochemical sensing methods: a brief review andrea scozzari*. Methods. 2008; 335–351

4. Moshirian-Farahi SS, Zamani HA, Abedi M. Nano-molar level determination of isoprenaline in pharmaceutical and clinical samples; a

nanostructure electroanalytical strategy. Eurasian Chem Commun. 2020;2:702–11.

5. Apak R, Üzer A, Sağlam Ş, Arman A. Selective electrochemical detection of explosives with nanomaterial based electrodes. Electroanalysis.

2023. https:// doi. org/ 10. 1002/ elan. 20220 0175.

6. Wang J. Analytical electrochemistry. Hoboken: Wiley; 2006. https:// doi. org/ 10. 1002/ 04717 90303.

7. Rana A, Baig N, Saleh TA. Electrochemically pretreated carbon electrodes and their electroanalytical applications – a review. J Electroanal Chem. 2019;833:313–32.

8. Fagiolari L, Sampò M, Lamberti A, Amici J, Francia C, Bodoardo S, Bella F. Integrated energy conversion and storage devices: interfacing

solar cells, batteries and supercapacitors. Energy Storage Mate. 2022;51:400–34.

9. Pollok D, Waldvogel SR. Electro-organic synthesis-a 21stcentury technique. Chem Sci. 2020;11:12386–400.

10. McCreery RL. The merger of electrochemistry and molecular electronics. Chem Rec. 2012;12:149–63.

11. Kraft A. Electrochromism: a fascinating branch of electrochemistry. ChemTexts. 2019;5:1–18.

12. Bi Li, Zhao R, Cao G, Xue,. Robust super-hydrophobic coating prepared by electrochemical surface engineering for corrosion protection. Coatings. 2019;9:452.

13. Díaz-Cruz JM, Serrano N, Pérez-Ràfols C, Ariño C, Esteban M. Electroanalysis from the past to the twenty-first century: challenges and

perspectives. J Solid State Electrochem. 2020;24:2653–61.

14. Mallakpour S, Behranvand V. Recent progress and perspectives on biofunctionalized CNT hybrid polymer nanocomposites. In: Thakur

VK, Thakur K, Pappu A, editors. Hybrid polymer composite materials: properties and characterisation. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2017.

15. Bhagabati P, Rahaman M, Khastgir D. Morphology and spectroscopy of polymer-carbon. Composites. 2019. https:// doi. org/ 10. 1007/ 978- 981- 13- 2688-2_9.

16. Singh N, Sanyal U, Fulton JL, Gutiérrez OY, Lercher JA, Campbell CT. quantifying adsorption of organic molecules on platinum in aqueous

phase by hydrogen site blocking and in situ X-ray absorption spectroscopy. ACS Catal. 2019;9:6869–81.

17. Baffert C, Sybirna K, Ezanno P, Lautier T, Hajj V, Meynial-Salles I, Soucaille P, Bottin H, Léger C. Covalent attachment of FeFe hydrogenases

to carbon electrodes for direct electron transfer. Anal Chem. 2012;84:7999–8005.

18. Chen X, Cheng X, Gooding JJ. Detection of trace nitroaromatic isomers using indium tin oxide electrodes modified using β-cyclodextrin

and silver nanoparticles. Anal Chem. 2012;84:8557–63.

19. Bard AJ. Chemical modification of electrodes. J Chem Educ. 1983;60:302–4.

20. Mitzi DB, Kosbar LL, Murray CE, Copel M, Afzali A. High-mobility ultrathin semiconducting films prepared by spin coating. Nature. 2004;428:299–303.

21. Babar NUA, Asghar MN, Hussain F, Joya KS. Spray-assembled nanoscale cobalt-oxide as highly efficient and durable bifunctional elec-

trocatalyst for overall water splitting. Mater Today Energy. 2020;17:100434.

22. Dar RA, Khare NG, Cole DP, Karna SP, Srivastava AK. Green synthesis of a silver nanoparticle–graphene oxide composite and its applica-

tion for As( iii ) detection. RSC Adv. 2014;4:14432–40.

23. Suherman AL, Ngamchuea K, Tanner EEL, Sokolov SV, Holter J, Young NP, Compton RG. Electrochemical detection of ultratrace (picomolar)

levels of Hg2+ using a silver nanoparticle-modified glassy carbon electrode. Anal Chem. 2017;89:7166–73.

24. Qin X, Wang H, Miao Z, Wang X, Fang Y, Chen Q, Shao X. Synthesis of silver nanowires and their applications in the electrochemical

detection of halide. Talanta. 2011;84:673–8.

25. Zuo C, Scully AD, Gao M. Drop-casting method to screen ruddlesden-popper perovskite formulations for use in solar cells. ACS Appl

Mater Interfaces. 2021;13:56217–25.

26. Kaliyaraj Selva Kumar A, Zhang Y, Li D, Compton RG. A mini-review: how reliable is the drop casting technique? Electrochem Commun. 2020;121:106867.

27. Neuróhr K, Pogány L, Tóth BG, Révész Á, Bakonyi I, Péter L. Electrodeposition of Ni from various non-aqueous media: the case of alcoholic

solutions. J Electrochem Soc. 2015;162:D256–64.

28. Khudaish EA. Reversible potentiodynamic deposition of VO2/V2O5 network onto strongly oxidative glassy carbon electrode for quan-

tification of tamoxifen drug. Microchem J. 2020;152: 104327. Vol.:(0123456789) Review

Discover Electrochemistry (2024) 1:12

| https://doi.org/10.1007/s44373-024-00012-8

29. Hezard T, Fajerwerg K, Evrard D, Collière V, Behra P, Gros P. Influence of the gold nanoparticles electrodeposition method on Hg(II) trace

electrochemical detection. Electrochim Acta. 2012;73:15–22.

30. Tonelli D, Scavetta E, Gualandi I. Electrochemical deposition of nanomaterials for electrochemical sensing. Sensors. 2019. https:// doi. org/ 10. 3390/ s1905 1186.

31. Malyshev VV, Shakhnin DB. Titanium coating on carbon steel: direct-current and impulsive electrodeposition. Physicomech Chem Prop Mater Sci. 2014;50:80–91.

32. Ziyatdinova G, Guss E, Yakupova E. Electrochemical sensors based on the electropolymerized natural phenolic antioxidants and their

analytical application. Sensors. 2021. https:// doi. org/ 10. 3390/ s2124 8385.

33. Martins JI, Bazzaoui M, Reis TC, Costa SC, Nunes MC, Martins L, Bazzaoui EA. The effect of pH on the pyrrole electropolymerization on

iron in malate aqueous solutions. Prog Org Coat. 2009;65:62–70.

34. Abdel-Hamid R, Newair EF. Voltammetric determination of polyphenolic content in pomegranate juice using a poly(gallic acid)/multi-

walled carbon nanotube modified electrode. Beilstein J Nanotechnol. 2016;7:1104–12.

35. Fomo G, Waryo T, Feleni U, Baker P, Iwuoha E. Electrochemical polymerization BT - functional polymers. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 105–31.

36. Lee SA, Yang JW, Choi S, Jang HW. Nanoscale electrodeposition: dimension control and 3D conformality. Exploration. 2021. https:// doi. org/ 10. 1002/ EXP. 20210 012.

37. Nagaiah TC, Schäfer D, Schuhmann W, Dimcheva N. Electrochemically deposited Pd-Pt and Pd-Au codeposits on graphite electrodes for

electrocatalytic H2O2 reduction. Anal Chem. 2013;85:7897–903.

38. Sadabadi KK, Ramesh P, Guezennec Y, Rizzoni G. Development of an electrochemical model for a Lithium Titanate oxide nickel manganese

cobalt battery module. J Energy Storage. 2022;50:104046.

39. Amin HMA, Königshoven P, Hegemann M, Baltruschat H. Role of lattice oxygen in the oxygen evolution reaction on Co3O4: isotope

exchange determined using a small-volume differential electrochemical mass spectrometry cell design. Anal Chem. 2019;91:12653–60.

40. Garcia-Segura S, Qu X, Alvarez PJJ, et al. Opportunities for nanotechnology to enhance electrochemical treatment of pollutants in potable

water and industrial wastewater-a perspective. Environ Sci Nano. 2020;7:2178–94.

41. Daraee H, Eatemadi A, Abbasi E, Aval SF, Kouhi M, Akbarzadeh A. Application of gold nanoparticles in biomedical and drug delivery.

Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2016;44:410–22.

42. Paulchamy B, Arthi G, Lignesh BD. A simple approach to stepwise synthesis of graphene oxide nanomaterial. J Nanomed Nanotechnol. 2015;06:1–4.

43. Boles MA, Ling D, Hyeon T, Talapin DV. Erratum: the surface science of nanocrystals. Nat Mater. 2016;15:364–364.

44. Duan H, Wang D, Li Y. Green chemistry for nanoparticle synthesis. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:5778–92.

45. Tajik S, Taher MA, Beitollahi H. First report for electrochemical determination of levodopa and cabergoline: application for determination

of levodopa and cabergoline in human serum, urine and pharmaceutical formulations. Electroanalysis. 2014;26:796–806.

46. Venu M, Venkateswarlu S, Reddy YVM, Seshadri Reddy A, Gupta VK, Yoon M, Madhavi G. Highly sensitive electrochemical sensor for

anticancer drug by a zirconia nanoparticle-decorated reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite. ACS Omega. 2018;3:14597–605.

47. Soltani H, Beitollahi H, Hatefi-Mehrjardi AH, Tajik S, Torkzadeh-Mahani M. Voltammetric determination of glutathione using a modified

single walled carbon nanotubes paste electrode. Anal Bioanal Electrochem. 2014;6:67–79.

48. Shankar SS, Shereema RM, Ramachandran V, Sruthi TV, Kumar VBS, Rakhi RB. Carbon quantum dot-modified carbon paste electrode-

based sensor for selective and sensitive determination of adrenaline. ACS Omega. 2019;4:7903–10.

49. Chauhan N, Chawla S, Pundir CS, Jain U. An electrochemical sensor for detection of neurotransmitter-acetylcholine using metal nano-

particles, 2D material and conducting polymer modified electrode. Biosens Bioelectron. 2017;89:377–83.

50. Tajik S, Taher MA, Beitollahi H, Torkzadeh-Mahani M. Electrochemical determination of the anticancer drug taxol at a ds-DNA modified

pencil-graphite electrode and its application as a label-free electrochemical biosensor. Talanta. 2015;134:60–4.

51. Yaqoob AA, Ahmad H, Parveen T, Ahmad A, Oves M, Ismail IMI, Qari HA, Umar K, Mohamad Ibrahim MN. Recent advances in metal deco-

rated nanomaterials and their various biological applications: a review. Front Chem. 2020;8:1–23.

52. Katz E, Willner I. Integrated nanoparticle-biomolecule hybrid systems: synthesis, properties, and applications. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:6042–108.

53. Srivastava S, Kumar V, Arora K, Singh C, Ali MA, Puri NK, Malhotra BD. Antibody conjugated metal nanoparticle decorated graphene

sheets for a mycotoxin sensor. RSC Adv. 2016;6:56518–26.

54. Srivastava S, Abraham S, Singh C, Ali MA, Srivastava A, Sumana G, Malhotra BD. Protein conjugated carboxylated gold@reduced graphene

oxide for aflatoxin B1 detection. RSC Adv. 2015;5:5406–14.

55. Li M, Wang P, Li F, Chu Q, Li Y, Dong Y. An ultrasensitive sandwich-type electrochemical immunosensor based on the signal amplification

strategy of mesoporous core–shell Pd@Pt nanoparticles/amino group functionalized graphene nanocomposite. Biosens Bioelectron. 2017;87:752–9.

56. Li YY, Kang P, Wang SQ, Liu ZG, Li YX, Guo Z. Ag nanoparticles anchored onto porous CuO nanobelts for the ultrasensitive electrochemical

detection of dopamine in human serum. Sens Actuators, B Chem. 2021;327:128878.

57. Grogan SP, Dorthé EW, Glembotski NE, Gaul F, D’Lima DD. Cartilage tissue engineering combining microspheroid building blocks and

microneedle arrays. Connect Tissue Res. 2020;61:229–43.

58. Qu L, Yang L, Ren Y, Ren X, Fan D, Xu K, Wang H, Li Y, Ju H, Wei Q. A signal-off electrochemical sensing platform based on Fe3S4-Pd and

pineal mesoporous bioactive glass for procalcitonin detection. Sens Actuators, B Chem. 2020;320:128324.

59. Ozcelikay G, Kurbanoglu S, Yarman A, Scheller FW, Ozkan SA. Au-Pt nanoparticles based molecularly imprinted nanosensor for electro-

chemical detection of the lipopeptide antibiotic drug Daptomycin. Sens Actuators, B Chem. 2020;320:128285.

60. Elseman AM, Abdelbasir SM. Nanosilver-based electrocatalytic materials. In: Shukla SK, Hussain CM, Patra S, Choudhary M, editors.

Electrocatalytic materials for renewable energy. Hoboken: Wiley; 2024. p. 71–110.

61. Fekry AM. A new simple electrochemical Moxifloxacin Hydrochloride sensor built on carbon paste modified with silver nanoparticles.

Biosens Bioelectron. 2017;87:1065–70. Vol:.(1234567890)

Discover Electrochemistry (2024) 1:12

| https://doi.org/10.1007/s44373-024-00012-8 Review

62. Faisal M, Alam MM, Asiri AM, Alsaiari M, Saad Alruwais R, Jalalah M, Madkhali O, Rahman MM, Harraz FA. Detection of hydrogen peroxide