Preview text:

sustainability Article

Behavioral Intention to Purchase Sustainable Food: Generation Z’s Perspective

Dominika Jakubowska 1,* , Aneta Zofia Da˛browska 2 , Bogdan Pachołek 3 and Sylwia Sady 4 1

Faculty of Economic Sciences, Department of Market and Consumption, University of Warmia and Mazury in

Olsztyn, Oczapowskiego 2, 10-719 Olsztyn, Poland 2

Faculty of Food Science, Department of Dairy Science and Quality Management, University of Warmia and

Mazury in Olsztyn, Oczapowskiego 7, 10-719 Olsztyn, Poland; anetazj@uwm.edu.pl 3

Institute of Marketing, Department of Product Marketing, Poznan´ University of Economics and Business, al.

Niepodleglosci 10, 61-875 Poznan, Poland; bogdan.pacholek@ue.poznan.pl 4

Institute of Quality Science, Department of Natural Science and Quality Assurance, Poznan´ University of

Economics and Business, al. Niepodleglosci 10, 61-875 Poznan, Poland; sylwia.sady@ue.poznan.pl *

Correspondence: dominika.jakubowska@uwm.edu.pl

Abstract: Sustainable food consumption is critical for addressing global environmental challenges

and promoting health and ethical practices. Understanding what drives sustainable food choices

among younger generations, particularly Generation Z, is essential for developing effective strategies

to encourage sustainable consumption patterns. Using the Theory of Planned Behavior as the

theoretical framework, this study aims to explore how the variables of the theory (personal attitude,

subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control), along with consumer knowledge, trust, and

health concerns, affect Generation Z’s intentions to buy sustainable food. The research was carried

out in Poland via the online interview method (CAWI), with 438 users ranging between the ages

18 and 27. The results show that attitudes and knowledge are significant predictors of sustainable

food consumption among Generation Z, while subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, health

consciousness, and trust do not significantly affect purchase intentions. This research underscores the

importance of educational campaigns and marketing strategies that enhance consumer knowledge

and shape positive attitudes towards sustainable food. These insights offer valuable implications for

policymakers, marketers, and educators aiming to encourage sustainable practices. Understanding

the drivers of Generation Z’s sustainable food consumption behaviors can provide valuable insights

Citation: Jakubowska, D.; Da˛browska,

for developing effective strategies to promote sustainable consumption patterns. This study adds

A.Z.; Pachołek, B.; Sady, S. Behavioral

to the body of knowledge on sustainable food consumption by highlighting the specific factors that

Intention to Purchase Sustainable

drive Generation Z’s purchasing intentions.

Food: Generation Z’s Perspective.

Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284. https:// doi.org/10.3390/su16177284

Keywords: Generation Z; sustainable food consumption; intention to buy; consumer knowledge;

attitude; Theory of Planned Behavior Academic Editor: Ilija Djekic Received: 28 June 2024 Revised: 11 August 2024 Accepted: 18 August 2024 1. Introduction Published: 24 August 2024

In the face of growing societal awareness regarding the impact of consumer actions on

the natural environment and individual health, sustainable food purchasing has become

a priority for societies worldwide. Public consciousness concerning the consequences

of food consumption for both the environment and personal health is intertwined with

Copyright: © 2024 by the authors.

an increasing interest in adopting sustainable practices. This shift in consumer behavior

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland.

is crucial for mitigating environmental degradation and promoting healthier lifestyles.

This article is an open access article

Sustainable food consumption is important due to its potential to mitigate environmental

distributed under the terms and

impact, promote social responsibility, and support long-term food security [1]. Consumers’

conditions of the Creative Commons

choices in favor of sustainable food can drive significant positive changes in production

Attribution (CC BY) license (https://

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/

practices and environmental conservation. 4.0/).

Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284 2 of 18

Consumers define sustainable food in various ways, influenced by factors such as price,

health, and environmental impact [2]. This definition is further shaped by their attitudes

and behaviors, leading to the identification of distinct consumer segments [3]. However,

there is a lack of understanding and knowledge among consumers about sustainability,

with many prioritizing other factors in their food choices [2]. Factors such as organic and

fair-trade attributes can significantly influence consumer attitudes towards sustainable

food products [4]. To date, little research has focused on traditional food products (TFPs)

as an example of sustainable products [5,6]. According to Tsolakis et al. [7], TFPs are

characterized by attributes such as their short shelf life, seasonality, unique production

circumstances, and ease of storage and transportation. These attributes have a substantial

impact on the sustainability of their consumption. Programs promoting and protecting

TFPs, like geographical indications, support sustainability by linking products to their

origins and local resources. Selling TFPs through short supply chains is environmentally

beneficial due to reduced transport, packaging, and food losses [6]. Therefore, traditional

food can be identified to some extent with ‘sustainable food’. Research on traditional

food products (TFPs) as examples of sustainable products is limited and there is little

knowledge on how various predictors affect sustainable food purchases. This highlights

the need for more studies of how TFP attributes influence consumer decisions towards sustainable foods.

To understand and predict various consumer behaviors, including food choices, the

Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) has been widely utilized. The key components of

the TPB are attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control, which influence

behavioral intention [8]. Attitude reflects one’s positive or negative evaluation of the

behavior, subjective norms involve perceived social pressure, and perceived behavioral

control relates to the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behavior. Despite

the wide application of the TPB to explain relations between variables built around the

attitude–intention–behavior framework, various researchers from different fields have

questioned the TPB’s usefulness. Previous research [9–11] suggests that while the TPB

assumes attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control determine behavioral

intention, it does not account for some domain-specific factors. According to Ajzen [8], the

TPB can be expanded by introducing additional variables or changing their paths. Therefore,

increasing evidence has been noticed in the recent literature for including additional

predictor variables in the TPB. In this study, the authors utilized several factors drawn from

the Theory of Planned Behavior (attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral

control) in order to assess Generation Z’s intentions to buy sustainable food. In addition,

the role of three variables (consumer knowledge, trust, and health consciousness) was

examined. The underlying rationale was that this extension aligns with previous research

suggesting that consumer knowledge, trust, and health consciousness are substantial

motivators for adopting sustainable food practices [12–14]. Consumer knowledge about

sustainability issues influences attitudes and behaviors, enhancing the perceived value

and enabling informed choices [15]. Incorporating this construct allows to assess the

role of knowledge in shaping sustainable consumption patterns, which is particularly

relevant for Generation Z, who are known for their high access to information and desire

for transparency. Trust in the sources of information and the credibility of sustainability

claims are crucial for consumer confidence in purchasing decisions, as mistrust can act as a

barrier to sustainable consumption [16]. Including trust in the TPB model highlights the

importance of credibility and reliability of information in purchasing intentions. Health

consciousness is also a significant factor, especially among younger generations aware of

the health implications of their dietary habits [13]. Integrating health concerns into the

TPB framework reflects this critical aspect of decision-making. The extent to which these

variables play a role in shaping sustainable food purchase intentions within the framework

of the TPB remains an area requiring further exploration.

The present study can be distinguished from previous studies by focusing on the

evolution of the TPB in the context of sustainable food consumption. Moreover, partic-

Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284 3 of 18

ular attention was given to Generation Z (Gen Z), also called post-Millennials, who are

individuals born in 1995 or later [17], and are increasingly influential in the marketplace.

Gen Z exhibits greater impulsiveness in purchasing behavior compared to older cohorts.

Conversely, the buying decisions of Generation Z are frequently influenced by hedonistic

motives and are price-sensitive; yet Generation Z also displays a high awareness of en-

vironmental conservation issues in contrast to older generations [18,19]. Understanding

their motivations and intentions regarding sustainable food consumption is essential for

devising effective interventions and policies aimed at promoting sustainable consumption

patterns and fostering environmental and public health. Prior studies have also examined

consumption of sustainable food products, suggesting that Generation Z consumers are

driven by a combination of product attributes, perceived value, and sustainability consid-

erations when making purchasing decisions related to sustainable food products [20–24].

However, there is a scarcity in the discourse surrounding consumer knowledge, trust,

and health consciousness, which seem to be crucial to achieving sustainable consumption.

Considering this gap, the current study adds to the existing literature by offering new

insights into consumer behavior regarding sustainable food. To provide a deeper insight,

it is crucial to consider the TPB model, a widely accepted framework for understanding

consumer behavior. Through the examination of the interplay between health concerns,

consumer knowledge, trust, and the core components of TPB (personal attitude, subjective

norms, and perceived behavioral control), this paper provides a comprehensive view of

the factors influencing sustainable food purchase intentions. Through the examination of

these variables, this research aimed to present a more comprehensive understanding of

how the core components of the TPB and health concerns, consumer knowledge, and trust

can shape intentions to purchase sustainable food.

Based on the above background, this study provides insights into the mechanisms

underlying consumer decision-making regarding sustainable food choices. The topic of

sustainable food consumption is highly relevant in the context of global environmental and

social challenges. Moreover, as Generation Z continues to grow in influence, understanding

their consumption patterns and preferences becomes increasingly important for shaping

future market trends and sustainability efforts. 2. Literature Review

Sustainable food consumption can help reduce the environmental impact of the food

industry. To support sustainable food production and consumption, it is important to

understand consumer perceptions of sustainable food. By extending the classical compo-

nents of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)—attitude, subjective norms, and perceived

behavioral control—with the components product knowledge, trust, and health concerns,

research has been undertaken to identify and assess the determinants of purchase intentions for sustainable food. 2.1. Personal Attitude

Attitudes comprise the first group of factors that form the behavioral beliefs that the

consumer attaches to them. Every purchase intention is formed primarily by attitudes,

which are derived from the consumer’s beliefs about the expected outcome of a given

behavior. The higher the subjective value of the expected outcome of a behavior, the more

positive the attitude toward that behavior. In order to assess attitudes, it is necessary to

know a person’s opinions regarding both the behavior itself and the consequences they

associate with it. Attitude affects the likelihood of a person reacting positively or negatively

to a behavior. Consumer attitudes, shaped by influencers, perceived value, and brand

attitude, play a key role in determining consumer purchase intentions, highlighting the

complex interdependence between attitudes and purchase behavior in different market segments [8,25–27].

The results of studies conducted in different countries indicate that attitudes directly

influence the purchase intentions of food products, including organic and ecological prod-

Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284 4 of 18

ucts [28–30]. Positive attitudes towards organic and ecological products may contribute to

positive attitudes towards purchasing sustainable products [31–34]. On the basis of these

findings, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H1. Personal attitude affects consumer intention to purchase sustainable food. 2.2. Subjective Norms

Subjective norms are the consumer’s perceptions about what he or she should do

according to others. Subjective norms reflect social influences, which can be seen as a type

of social pressure that encourages or discourages action [8].

In a study conducted by Islam and Ali Khan [35], consumer attitude, subjective norms,

and perceived behavioral control were found to have a significant positive impact on the

purchase intention for sustainable products. The study contributed to domain marketing by

establishing a new concept called sustainable product evaluation, which included factors

such as perceived environmental values and beliefs, perceived environmental impact, and

product characteristics. Maduku [36] showed that environmental concerns play a key role

in shaping consumers’ positive and negative emotions, which influence their sustainable

consumption intentions. Furthermore, a study by Bulut et al. [37] showed that consumer

price awareness and brand awareness have a strong influence on their purchasing behavior

in relation to a sustainable product. However, some studies indicate that subjective norms

may not always be a strong factor influencing purchase intention [29,38]. On the basis of

these findings, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H2. Subjective norms affect consumer intention to purchase sustainable food.

2.3. Perceived Behavioral Control

Perceived behavioral control refers to the consumer’s subjective assessment of how

easy or difficult it is to control his or her behavior when influenced by external and

internal factors [8]. The most relevant factors shaping behavioral control include cost,

convenience, and time [39]. Studies have shown that behavioral control has a direct and

positive effect on the purchase intentions of various environmentally friendly products, e.g.,

green cosmetics [40,41], environmentally friendly clothing [42], sustainable biscuits [43],

and organic vegetables [29]. In summary, perceptual behavioral control evaluates the

effectiveness of potential actions, strongly influencing environmentally friendly intentions

and behaviours. On the basis of these findings, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H3. Perceived behavioral control affects consumer intention to purchase sustainable food.

2.4. Consumer Knowledge

Consumer knowledge forms the basis for decision-making and rationalizing consumer

behavior and shapes consumer confidence. Knowledge is the content resulting from the

combination of product information and consumer experience that influences consumer

purchasing decisions. Research has shown that providing consumers with comprehen-

sive and reliable product knowledge positively influences their purchase intentions and behavior [43–46].

In recent years, consumers have shown an increased interest in sustainability, par-

ticularly in adopting sustainable consumption patterns to contribute to environmental

protection. Consumers’ perceptions of sustainability are influenced by various factors, such

as environmental awareness, perceived value, trust in green labels and claims, sociocultural

influences, personal values, and income levels [47,48]. As Wong et al. [49] point out, knowl-

edge about green products positively influences product trust, which in turn influences the

intention to purchase a green product. The researchers also pointed out that for consumers,

the relationship between knowledge about green products and purchase intention is a

complex relationship, which is also influenced by trust in the product, perceived benefit,

Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284 5 of 18

and price. However, studies also indicate that despite growing environmental concerns

and interest in sustainable practices, the market share of sustainable products remains

low, indicating a gap between consumer perception and purchase intention, thus hinder-

ing sustainable choices [50–53]. On the basis of these findings, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H4. Consumer knowledge affects intention to purchase sustainable food. 2.5. Trust

Consumer trust in sustainable food is a key aspect that influences purchasing decisions

and consumer behavior. Recently, scholars have focused on the idea of trust and its compo-

nents, such as trusting intention and trust-related behavior [54]. Many studies highlight the

importance of consumer trust in different areas of the food industry, such as food producers

and processors [55–57], product labeling [58–60], market regulators [61–63], product certifi-

cation schemes [64,65], and mobile organic food delivery applications [66]. These studies

highlight that consumer trust plays a key role in overcoming the gap between intention and

behavior in food consumption, influencing actual purchase decisions. Perceived quality is

one of the main factors explaining the purchase and consumption of organic food [67]. In a

study by Setyarko et al. [29], consumer green assurance significantly influences purchase

intention for organic vegetables. The results of a study by Dangelico et al. [43] indicated

that familiarity with and perceived value of the product influences consumers’ purchase in-

tentions for sustainable biscuits, interacting with perceived quality, environmental concern,

and purchase intention. Understanding and fostering consumer confidence in sustainable

food systems is essential to promote the economization of consumption. On the basis of

these findings, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H5. Trust affects consumer intention to purchase sustainable food.

2.6. Health Consciousness

The impact of food on consumer well-being is strongly linked to health, enjoyment,

and emotional aspects. In many studies, consumers have identified sensory attributes,

production processes, nutritional composition, and the context of food consumption as

the main factors underlying food-related well-being [68,69]. Research also highlights

the importance of health consciousness in relation to contemporary health concerns and

willingness to use functional foods, indicating that people with higher health consciousness

show greater concern about health-related factors and are more likely to use functional

foods to achieve a higher quality of life [70].

Consumer health awareness plays a significant role in predicting consumers’ inten-

tions to purchase organic food [71]. Results from a study of consumers of organic vegetables

in Brazil [28] indicate that attitude mediates the relationship between perceived health

benefits and intention and perceived sustainability benefits. As shown by the results of

various studies, consumers attribute health benefits to organic foods due to their natural

origin, and these benefits are important factors influencing consumer purchase decisions

and attitudes [48,66,72–74]. According to Konuk [75], in addition to the health conscious-

ness of organic food consumers, environmental concerns are an important factor driving

consumers to purchase food. The findings of De Farias [76] among organic food consumers

in Brazil indicated that environmental awareness positively influences consumer attitudes,

healthy consumption significantly influences consumer attitudes, and attitudes and subjec-

tive norms positively influence the intention to purchase again in the context of organic

food consumption, thus reinforcing signs of healthier and more sustainable consumption

behavior. On the basis of these findings, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H6. Health consciousness affects consumer intention to purchase sustainable food.

Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284 6 of 18

Some studies also include other factors such as environmental knowledge, materi-

alism, environmental influences, promotion of sustainable consumption, disclosure of

sustainability attributes, and behavioral intention of sustainable consumption [77–79].

Therefore, increasing evidence has been noticed in the recent literature for including ad-

ditional predictor variables in the TPB. The extent to which health concerns, consumer

knowledge, and trust play a role in shaping sustainable food purchase intentions within

the framework of the TPB remains an area requiring further exploration. Furthermore,

the inclusion of variables such as environmental concerns, personal moral norms, and

perceived consumer efficacy, along with the TPB, can predict environmentally friendly pur-

chase intentions, highlighting the importance of tailored sustainable marketing strategies

and policies to promote sustainable food choices [80]. To increase consumer acceptance of

sustainable products, companies and policy makers should consider a holistic approach

to sustainability, targeting new consumer segments and exploring trade-offs between dif-

ferent dimensions of sustainability to meet consumer preferences and support greater

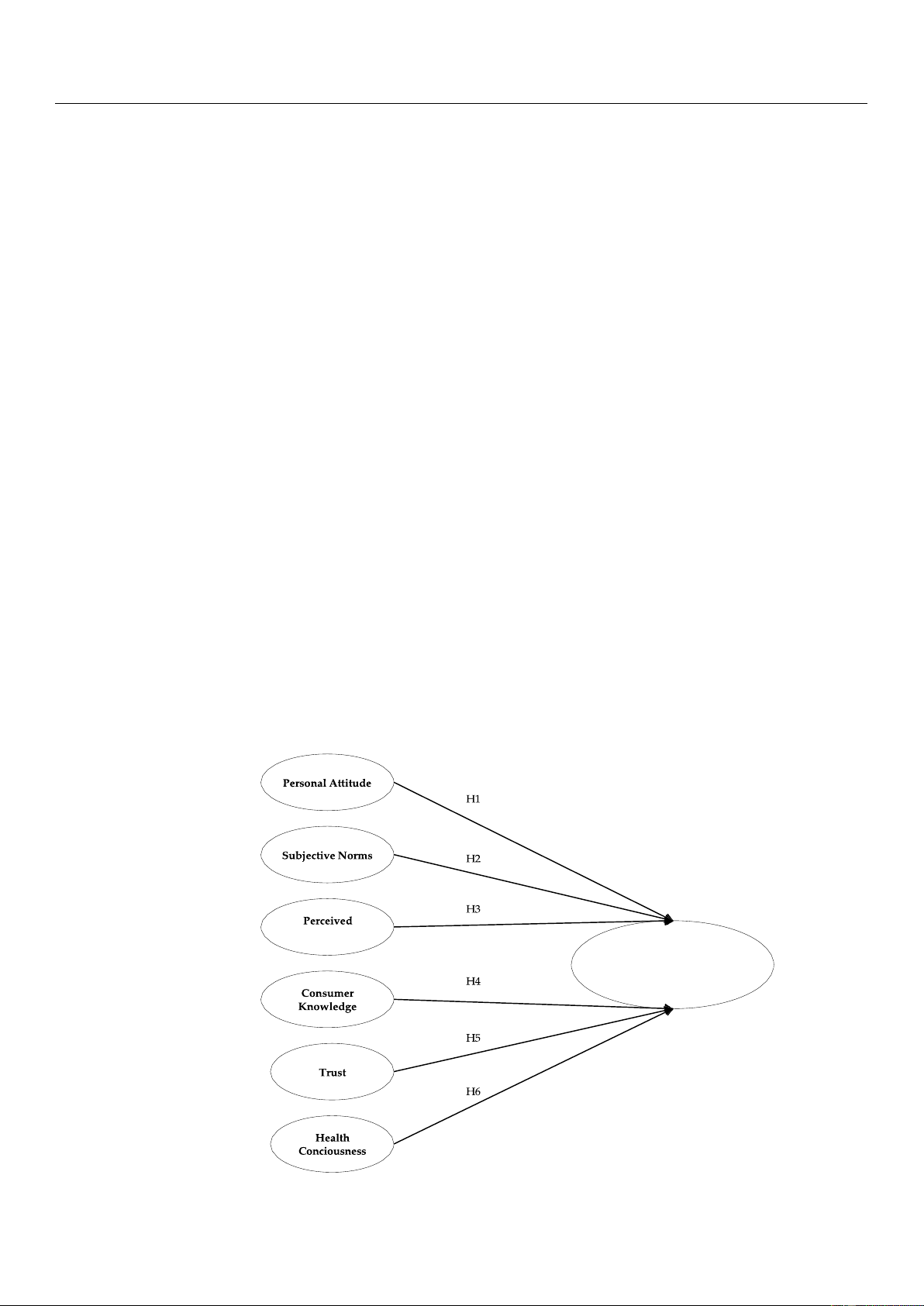

development of environmentally friendly products. 3. Materials and Methods 3.1. Study Design

This research adopted the deductive method by building on theories that have already

been proposed by other researchers [81]. Firstly, the TPB model was discussed with relevant

hypotheses. The hypotheses for this study were defined based on the results of previous

research, as detailed in the earlier literature review. Then, the hypotheses were tested

through data analysis, contributing to summarizing the factors affecting the intention of

Generation Z consumers to purchase sustainable food. Through quantitative analysis of

the collected primary data, a theoretical framework suitable for analyzing the impact of

selected factors on the purchase intention for sustainable food products of Generation

Z consumers was summarized. The factors affecting sustainable food consumption are

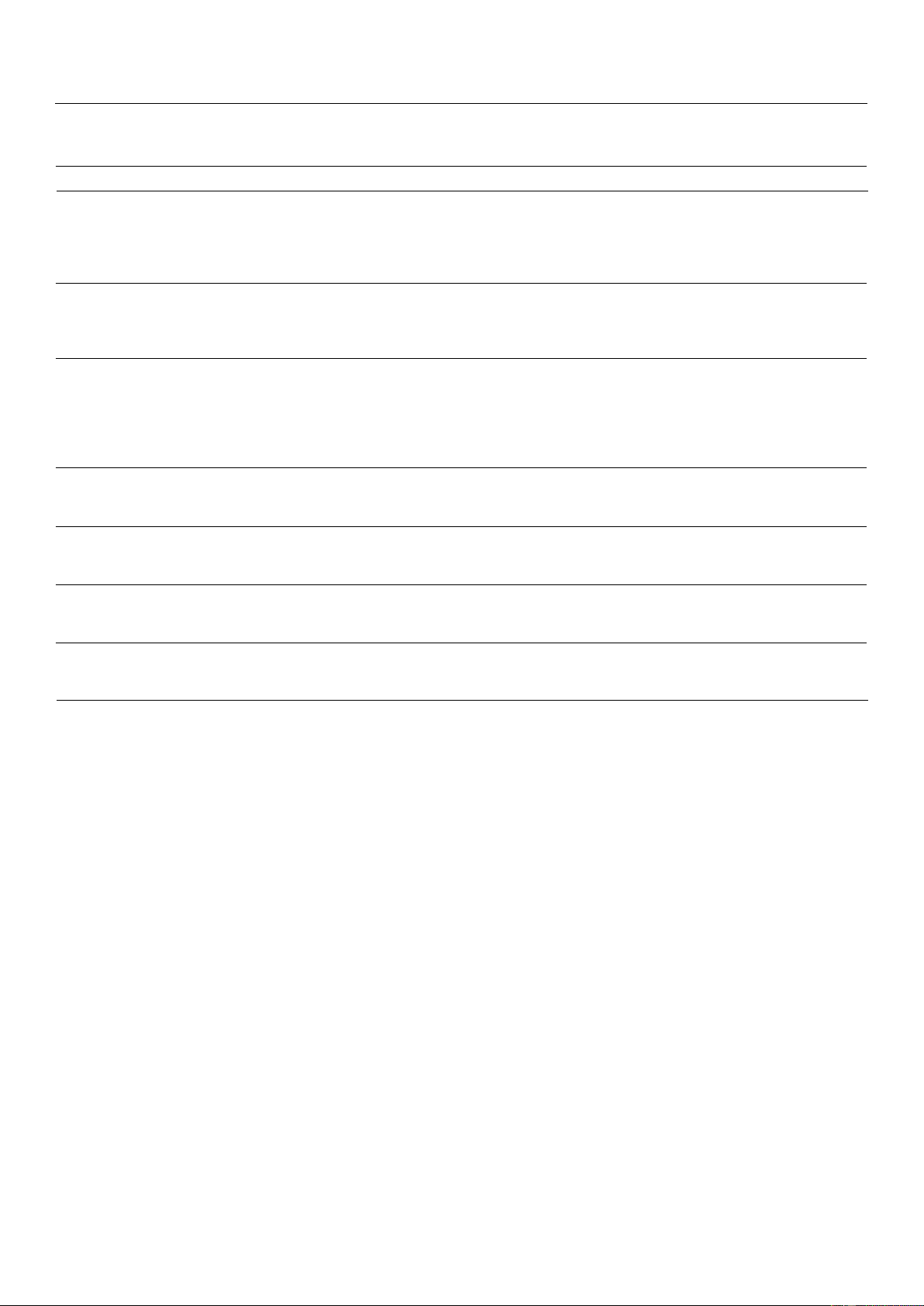

presented in the conceptual structure (Figure 1). This analysis selects one dependent

variable, which is consumers’ intention to purchase, and six independent variables, which

are personal attitude (ATT), subjective norms (SN), perceived behavior control (PBC), health

consciousness (HC), consumer knowledge (KNOW), and trust (TRUST). Behavioral Control Intention to Purchase Sustainable Food

Figure 1. Conceptual framework and hypotheses.

Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284 7 of 18

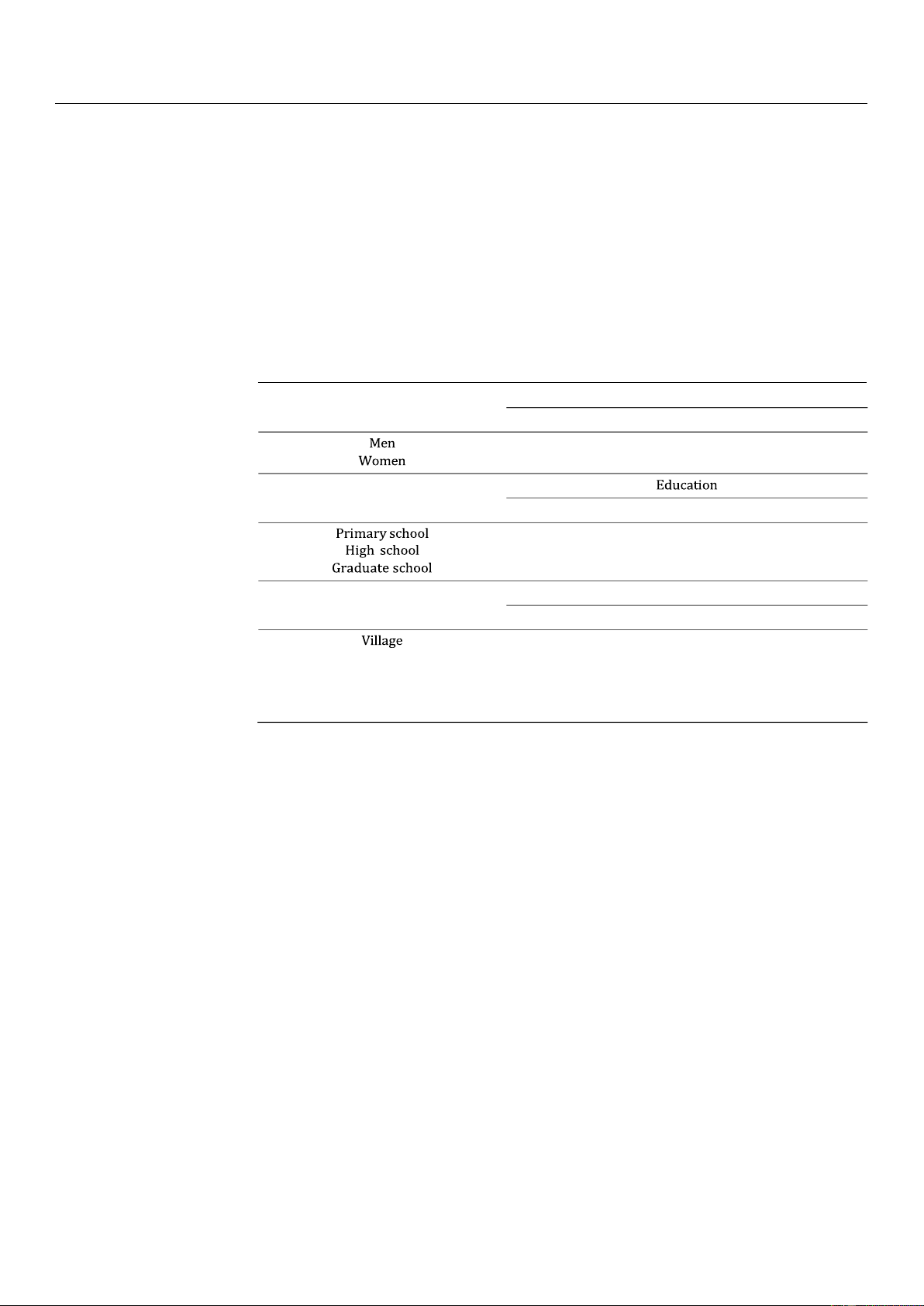

3.2. Procedure and Participants

This research was based on a quantitative method of analysis to examine the factors

influencing the intention to purchase sustainable food products, taking as an example the

TFP. The research was carried out via the online interview method (CAWI), with users

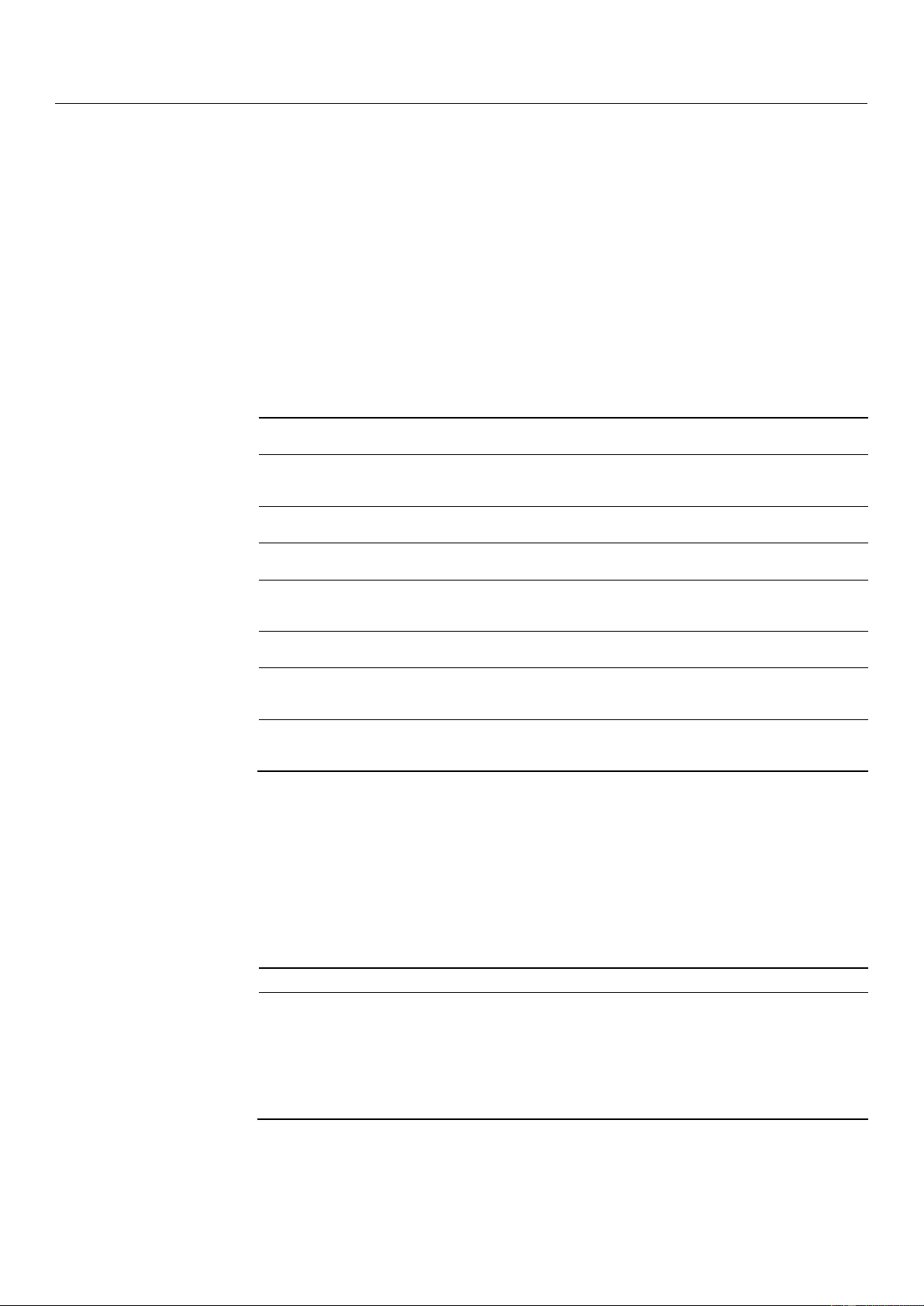

ranging between the ages of 18 and 27 (Table 1). The selection of respondents for the study

was determined by a convenience sampling procedure. The sampling frame was narrowed

down only to people who met the survey criteria. The research population consisted of

people living in different parts of Poland, who declared they were buying and eating sus-

tainable food products of different categories. The sample of 438 respondents was recruited

from an adult population (representatives of Generation Z) in the years 2022–2023.

Table 1. Survey sample characteristics. Gender Measure n % 176 40 262 60 n % 5 1 286 65 147 34 Place of residence n % 121 28 City up to 50,000 inhabitants 109 25

City 50,001–200,000 inhabitants 78 18

City 200,001–500,000 inhabitants 35 8 City over 500,000 inhabitants 95 22

The questionnaire was created digitally using Google Forms and distributed over

peer-to-peer digital networks and social media platforms. The digital distribution removed

the constraint of geography, allowing responses from many regions in Poland.

A total of 438 respondents were included in the research to analyze the factors in-

fluencing the intention to purchase sustainable food. The distribution of respondents by

residence shows that 28% of the respondents resided in villages and 72% resided in cities.

The gender-wise distribution of the respondents had a female (262 respondents) to male

(176 respondents) allocation of 60–40%. The education distribution shows that 65% of

respondents possessed a high school education (286 respondents), 34% of respondents

had attained graduate degrees, and a smaller portion of the sample, consisting of 1% of

respondents, had completed primary school education. 3.3. Measures

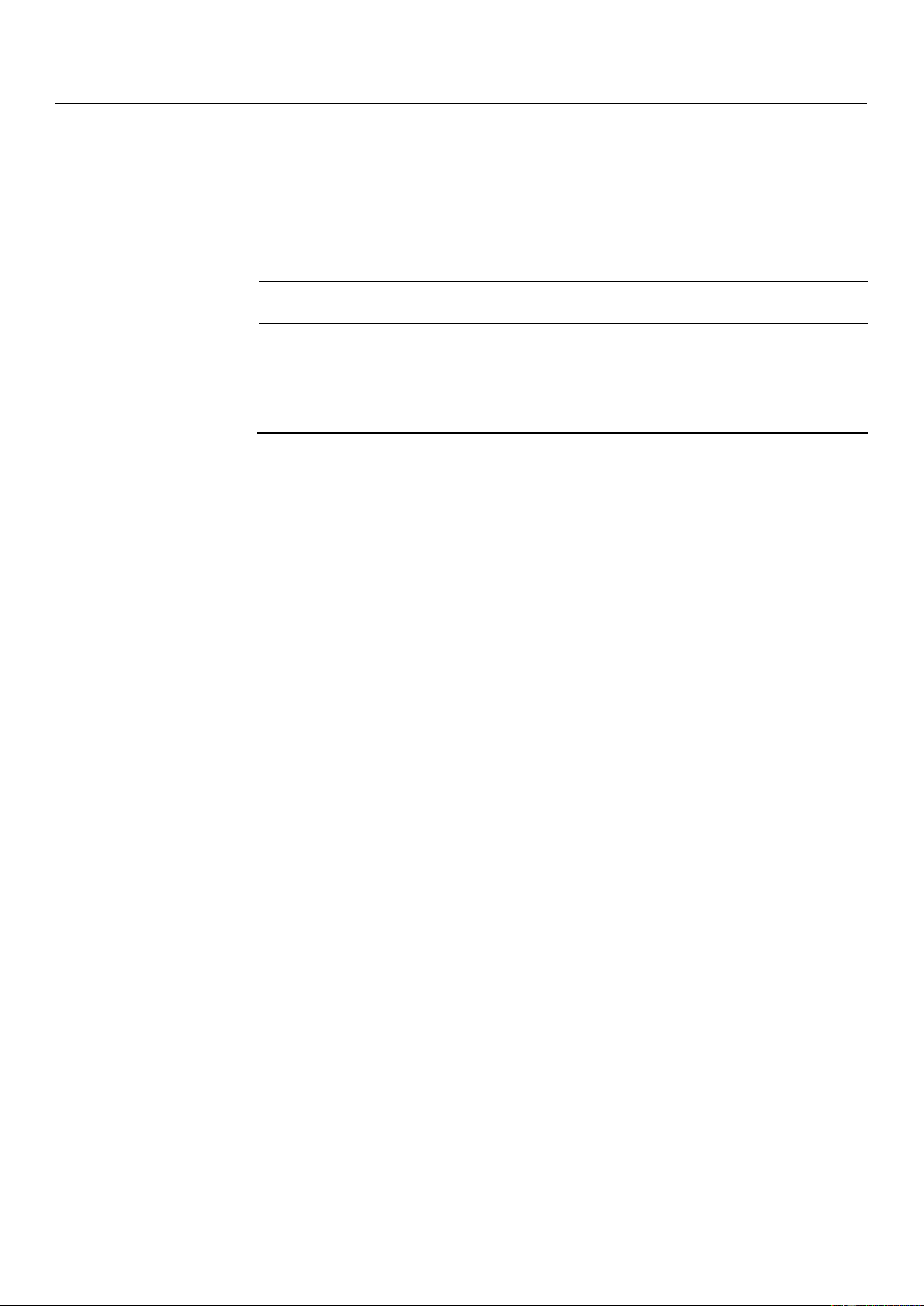

The items for all the constructs, namely, personal attitude towards sustainable food [82–85]

(4 items), subjective norms [86–88] (3 items), perceived behavioral control [85,89,90] (5 items),

health consciousness [91] (3 items), knowledge [92,93] (3 items), trust [89,94] (3 items), and

purchase intentions [89,95] (3 items) were adopted from the literature. The questionnaire

was designed using the theoretical framework discussed earlier and presented measures of

the TPB constructs that complied with the TPB questionnaire construction guidelines [96].

Table 2 describes the items of each construct. All the items were measured on the scale of 1–

7, with 7 as strongly agree and 1 as strongly disagree [97]. Finally, participants answered socio-demographic questions.

Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284 8 of 18

Table 2. Constructs and items of the study. Construct Item

ATT1. Purchasing sustainable food products protects the natural environment

ATT2. When I buy sustainable food products I am sure that I help protect my health Personal Attitude (ATT)

ATT3. I believe that buying sustainable food products help preserve the sustainable

development of the region and the community

ATT4. I am sure that when I buy sustainable food products, I buy products of higher quality

SN1. My family members buy sustainable food products Subjective Norms (SN)

SN2. My friends think that, I should choose sustainable food products

SN3. The trend of buying sustainable food among people around me is increasing

PCB1. I have the competence to search for sustainable food

products among others available in the store

PCB2. I pay attention to sustainable food price

Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) PBC3. I have complete information and awareness regarding where to buy sustainable food

PCB4. I have time to purchasing of sustainable food products

PCB5. I have the financial capability to buy sustainable food products

KNOW1. I have knowledge about sustainable food Consumer Knowledge (KNOW)

KNOW2. I know that sustainable foods are high quality products

KNOW3. I have more knowledge about sustainable food products than other people

TRUST 1. I trust producers to ensure high quality Trust (TRUST)

TRUST 2. I trust sustainable methods in production

TRUST 3. I trust food certificates and quality marks

HC1. To maintain my fitness, I carefully choose my food Health Consciousness (HC)

HC2. I consider myself very health conscious

HC3. When eating, I often consider health-related concerns

INT1. I have a very high purchase interest for sustainable food products Intention to purchase (INT)

INT2. I intent to buy sustainable food products in the next month

INT3. I am willing to pay a higher price for sustainable food product

The questionnaire was piloted with 20 consumers of sustainable foods to ensure that

the questions and response formats were clear. Suggested changes were incorporated in the questionnaire. 3.4. Data Analysis

In this study, the software used for data analysis was IBM SPSS 29 for preliminary

data analysis and IBM AMOS 29 for structural equation modeling (SEM). The presence

of outliers was investigated to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the dataset. In the

next step, structural equation modeling (SEM) was applied to test the research model.

Initially, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to investigate the adequacy

of the measurement model. For the measurement model, factor loadings of the statements

were examined first. Due to the standardized factor loadings being below 0.50, one item

of attitude (ATT3), one item of subjective norms (SN3), one item of trust (TRUST3), and

three items of perceived behavioral control (PBC2, PBC4, and PBC5) were removed from the model.

Fit indicators of the measurement model considered included chi-square (χ2), root

mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and standard-

ized root mean squared residual (SRMR). Typically, a satisfactory model is denoted by χ2

not being significant, χ2/df ≤ 3, RMSEA ≤ 0.06, CFI ≥ 0.95, and SRMR ≤ 0.08 [98].

The reliability and validity of the constructs were tested using Cronbach’s alpha for

reliability (α > 0.70), composite reliability (CR > 0.70), and average variance extracted

(AVE > 0.50). Discriminant validity was assessed by ensuring that the square root of the

AVE for each construct was greater than the correlations with other constructs (Fornell

Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284 9 of 18

and Larcker’s (F-L) criteria) [99]. Finally, a structural model was used in order to test the

hypothesized model of relations (Figure 1). 4. Results

The measurement model presented adequate validity and reliability indicators, and is

presented in Table 3. The descriptive statistics of each item are demonstrated in Supple-

mentary Material. To estimate the reliability of measures, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients

and composite reliability (CR) values were determined; then, descriptive statistics were

computed for all variables. All constructs presented values of Cronbach’s alpha, CR, and

AVE that indicate adequate validity and reliability: composite reliabilities (CRs) ranged

from 0.8 to 0.9, average variance extracted (AVE) ranged from 0.5 to 0.9, and Cronbach’s

coefficients were satisfactory.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics, and validity and reliability assessment. Factor Construct Item Mean (SD) * Cronbach’s CR AVE Loadings Alpha ATT1 5.85 (1.14) 0.806 0.764 0.9 0.6 Personal Attitude (ATT) ATT2 0.879 ATT4 0.781 Subjective Norms (SN) SN1 4.45 (1.65) 0.882 0.704 0.8 0.6 SN2 0.882 Perceived Behavioral PBC1 5.31 (1.30) 0.835 0.732 0.8 0.5 Control (PBC) PBC3 0.835 KNOW1 Consumer Knowledge 5.15 (1.21) 0.832 0.776 0.9 0.7 KNOW2 (KNOW) 0.786 KNOW3 0.778 TRUST1 Trust (TRUST) 5.30 (1.22) 0.941 0.760 0.9 0.8 TRUST2 0.941 HC1 Health Consciousness 5.40 (1.30) 0.918 0.902 0.9 0.9 HC2 (HC) 0.917 HC3 0.913 INT1 Intention to purchase 5.26 (1.28) 0.851 0.767 0.9 0.7 INT2 (INT) 0.873 INT3 0.761

* All measures were scored on 7-point scales. Abbreviations: CR, composite reliability; AVE, average variance extracted.

Based on the results presented in Table 4, it was observed that the square root of AVE

for the research constructs (0.70 < AVE < 0.92) was greater than the correlation between

them (0.32 < r < 0.67). This result indicates the confirmation of the discriminant validity of

the constructs in the proposed research model [100].

Table 4. Examining the discriminant validity of the research constructs. (Fornell and Larcker’s criterion). ATT SN PBC KNOW HC TRUST INT ATT 0.78 * SN 0.469 ** 0.796 * PBC 0.440 ** 0.511 ** 0.726 * KNOW 0.516 ** 0.528 ** 0.619 ** 0.868 * HC 0.320 ** 0.402 ** 0.384 ** 0.445 ** 0.819 * TRUST 0.399 ** 0.415 ** 0.504 ** 0.561 ** 0.352 ** 0.924 * INT 0.494 ** 0.520 ** 0.506 ** 0.673 ** 0.410 ** 0.524 ** 0.838 *

* The square roots of AVE estimate. ** Correlation is significant at the <0.01 level.

After confirming the validity and reliability of the measurement model, it was possible

to estimate the structural model and to test the research hypotheses proposed in this article

Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284 10 of 18

to explain sustainable food purchase intention. The results are presented in Table 5. The

goodness of fit indicators had adequate levels (χ2(114) = 258.893, p = 0.000, χ2/df = 2.271,

RMSEA = 0.054, CFI = 0.933, TLI = 0.776), indicating the overall validity of the measurement

model. In this study, attitude (β = 0.351, p < 0.003) and knowledge (β = 0.727, p < 0.001)

were identified as the predictors of intention to purchase sustainable food (Table 5).

Table 5. Structural model estimates. Hypothesized Standarized Hypothesis p-Value Conclusion Effects Regression Weight H1 INT ← ATT 0.351 0.003 supported H2 INT ← SN 0.024 0.706 not supported H3 INT ← PBC −0.397 0.122 not supported H4 INT ← KNOW 0.727 <0.001 supported H5 INT ← TRUST 0.142 0.124 not supported H6 INT ← HC −0.048 0.366 not supported 5. Discussion

This paper designs a social-psychological model to examine decisions regarding

the purchase of sustainable foods among young adults (Generation Z). The aim was to

investigate the interplay between health concerns, consumer knowledge, trust, and the

components of the TPB in influencing sustainable food purchase intentions. The results

indicated that the model used in the context of Gen Z’s behavioral intentions for sustainable

food was very successful, because the figure of variance explained was 79.0%. Our results

showed that consumers’ attitudes and knowledge were predictors of intention to purchase

sustainable food by Generation Z representatives.

The results of hypothesis H1 showed that the attitude toward sustainable food had a

significant effect on the purchase intention of Generation Z (β = 0.351, p < 0.003). These

findings are in line with the existing literature that shows attitude to be the most significant

predictor of intention to purchase sustainable food [31–34]. According to the analysis

of this data, it can be concluded that researchers consistently refer to it as the key to

understanding behavior and have referred to it as the most significant component in

explaining behavioral intentions [101]. People who have a sustainable and positive attitude

toward the environment are always more likely than others to refrain from engaging in

destructive activity in their immediate surroundings [102].

The study did not confirm the expected impacts of subjective norms and perceived

behavioral control on purchase intentions (β = 0.024, p = 0.70; β =−0.397, p = 0.122), and

consequently research hypotheses H2 and H3 were not supported. This was a surprise

conclusion, as it contradicted several previous studies that evaluated TPB variables to

predict sustainable food purchasing intentions [103–106]. However, the literature has

questioned the lack of predictive ability of one or more variables from the TPB model. Some

studies have reported comparable results, suggesting that perceived behavioral control and

subjective norms were not significant predictors of sustainable food purchase intentions,

so consumers may not always be a subject to attitudinal and normative control [107].

Hasan [108] found that perceived behavioral control significantly influences organic food

purchase intentions, while subjective norms do not. Similarly, Wong [38] found that

both perceived behavioral control and subjective norms are not significant predictors of

intentions to purchase suboptimal foods. However, Ham [109] and Shin [110] both found

that subjective norms do play a significant role in the intention to purchase green and local

food products, respectively. These mixed findings suggest that the influence of perceived

behavioral control and subjective norms on sustainable food purchase intentions may vary

depending on the specific context and type of sustainable food product.

A positive impact of knowledge on purchase intentions was found by this study

(β = 0.72, p < 0.001), providing support to research hypothesis H4 and empirical support

to the literature. Kumar [111] and Wang [48] both found that environmental knowledge

Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284 11 of 18

positively influences attitudes and purchase intentions for environmentally sustainable

and organic products. Lee [46] further demonstrated that consumer knowledge of certifi-

cation can increase purchase intentions for sustainable products. However, Vermeir [112]

highlighted the role of other factors, such as involvement, perceived availability, certainty,

perceived consumer effectiveness, values, and subjective norms in influencing attitudes and

intentions for sustainable food products. Environmental knowledge has been consistently

found to have a significant positive relationship with attitude towards sustainable products,

which in turn influences purchase intentions [46]. This knowledge can also moderate the

relationship between other factors, such as subjective norms, personal attitude, and health

consciousness, further increasing purchase intention [48].

This study did not confirm the effect of health consciousness on intention to purchase

sustainable food (β = −0.48, p = 0.36); thus, research hypothesis H5 was not supported.

The literature on the relationship between health consciousness and intention to purchase

sustainable food presents mixed findings. Dipietro et al. [113] and Parasha et al. [114]

found health consciousness to be a significant predictor of purchase intentions. However,

Michaelidou [115] found that health consciousness was the least important predictor of

attitude and intentions to purchase organic produce, with food safety concerns and ethical

self-identity playing more significant roles. Similarly, Huang et al. [116] found health

consciousness to be a major predictor of intentions to purchase healthy products but did

not specifically focus on sustainable food. These mixed findings suggest that while health

consciousness may play a role in purchase intentions, it is not always a significant predictor,

particularly in the context of sustainable food.

Finally, this study did not confirm the effect of trust on intentions to purchase sustain-

able food (β = 0.14, p = 0.12); thus, research hypothesis H6 was not supported. It is a notable

finding in our study that coincides with some other studies. Mughal [117] found that trust

was not a significant predictor of organic food purchase intentions in a non-regulated

market, while Ayyub [118] identified trust as a partial mediator of personal and product

attributes in the same context. Dumortier [119] also found that trust in organic certification

and the supply chain did not significantly influence organic food purchases. However,

research on sustainable food purchase intentions has yielded mixed results regarding the

significance of trust as a predictor. Other research indicates that trust in sustainable pro-

ducers and green claims can significantly impact consumer behavior [120,121]. Dowd and

Burke [122] found that ethical values, which are closely related to trust, were significant

predictors of intentions to purchase sustainably sourced foods. Trust acts as a mediator

between factors like environmental concern and perceived knowledge, leading to positive

purchase intentions for sustainable food options [123,124]. Moreover, the level of trust in

safety regulators and independent promoters also plays a vital role in shaping consumers’

intentions to consume sustainable food alternatives like plant-based meat [125]. These

findings suggest that while trust may not always be a direct predictor, it can play a role in

shaping consumer intentions for sustainable food.

In sum, the results of this study demonstrate that attitudes towards sustainable food

and consumer knowledge influence the intentions to purchase sustainable food among

Generation Z (H1 and H4 were supported). Generation Z often places a high value on

environmental sustainability and ethical consumption. If they understand how sustainable

food aligns with their values, they are more likely to support and purchase these products.

Positive attitudes toward sustainable food are aligned with these core values, making

individuals more inclined to act in accordance with their beliefs. Attitudes are often tied to

emotions, so when consumers feel positively about sustainable food, perhaps due to its

perceived benefits for health and the environment, these positive emotions can drive their

purchasing decisions. Knowledge about the benefits of sustainable food—such as environ-

mental impact, health benefits, and ethical considerations—make consumers more likely to

prioritize these options in their purchasing decisions. Educational initiatives that enhance

consumer knowledge could therefore be effective in promoting sustainable consumption.

Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284 12 of 18

Contrary to expectations, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control did not

play significant roles in influencing sustainable food purchase intentions (H2 and H3

were not supported). This suggests that external social pressures and perceived ease or

difficulty of purchasing sustainable food are less influential for Generation Z compared to

their personal attitudes and knowledge. Generation Z is often characterized by a strong

sense of individualism and personal values. They may prioritize their personal beliefs

and attitudes over societal expectations. As a result, subjective norms, which rely on the

influence of others, might be less impactful for this group compared to their own attitudes

and knowledge. In addition, with the widespread availability of information through

digital media, Generation Z has greater access to knowledge about sustainable practices.

This increased access to information allows them to form their own opinions and attitudes

independently of subjective norms. Generation Z also tends to have high confidence in

their ability to make informed decisions. This self-assurance can diminish the impact

of perceived behavioral control, as they feel capable of overcoming potential barriers to

purchasing sustainable food on their own.

This study did not confirm the effect of health consciousness and trust on the intention

to purchase sustainable food (H5 and H6 were not supported). This generation has grown

up with extensive information about healthy eating, which might make the specific health

benefits of sustainable food less compelling. While health consciousness is important,

Generation Z might prioritize other factors such as environmental impact, ethical consid-

erations, and social responsibility when it comes to sustainable food. These values could

overshadow health concerns in their decision-making process. With access to vast amounts

of information, Generation Z tends to rely more on personal research and peer reviews

rather than institutional trust. They prefer to verify claims independently and may question

the authenticity of sustainability labels, making trust in producers or certifications more

critical. Therefore, trust in food producers and certification bodies might be low, reducing

the impact of trust on their purchase intentions.

These research results provide valuable insights into the practical and theoretical

implications of the findings. Considering the practical implications, this study shows that

consumer education should be prioritized, focusing on raising awareness about the benefits

of sustainable food through targeted campaigns in schools and social media. Marketers

need to reevaluate how they communicate trust and health benefits, tailoring messages to

address the specific concerns and interests of Generation Z. Despite subjective norms not

being significant, strategies to leverage social influence should be explored, perhaps through

endorsements or peer influence mechanisms. Efforts should also investigate other barriers,

such as cost and convenience, to develop more effective interventions that encourage

sustainable food purchases. Turning to the theoretical research implications, the inclusion

of consumer knowledge in the TPB framework was validated, but the insignificance of

trust, health consciousness, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control suggested a need for model refinement.

Future research should explore additional variables or different factor combinations

that might better predict sustainable food purchasing intentions. The findings highlight the

importance of context-specific factors, indicating that TPB applications need to be tailored

to different consumer groups or cultural settings. This study calls for a more nuanced

approach to the TPB, considering unique influences within various demographic or cultural

contexts. Future studies should also explore the longitudinal changes in Generation Z’s

attitudes and behaviors towards sustainable food consumption, investigate the interplay of

additional factors such as economic constraints and accessibility, and compare the findings

across different cultural and regional contexts to develop more comprehensive and globally applicable strategies. 6. Conclusions

The aim of this research was to investigate the behavioral intentions of Gen Z to pur-

chase sustainable food. In this study, the extended Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) was

Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284 13 of 18

utilized. In terms of theory, it is implied from our findings that the attitudinal component

of the TPB is particularly crucial for understanding sustainable consumption behaviors

in Generation Z. This emphasizes the need for a deeper exploration of what shapes these

attitudes and how they can be positively influenced. The traditional components of the

TPB—subjective norms and perceived behavioral control—may need to be reconsidered

or expanded when applied to sustainable food consumption among Generation Z. This

demographic prioritizes personal attitudes and knowledge over social influences and

perceived ease of action. The findings contribute to the Theory of Planned Behavior, sug-

gesting potential extensions to the TPB framework by highlighting the significant role

of knowledge in shaping purchase intentions. This can stimulate further research and

discussion on how the TPB can be adapted to different contexts and demographic groups.

This study validates the importance of attitudes within TPB, while indicating that other

factors like health consciousness and trust may not be as influential as previously thought.

This highlights the importance of considering demographic factors when applying the TPB.

What drives behavior in one demographic may not hold true universally, suggesting the

need for tailored theoretical models.

From a practical point of view, this study provides a justification for using attitude

and knowledge dimensions in policies and programs that intend to encourage young

adult people to purchase sustainable foods. Given that attitude and knowledge were

the strongest predictor of Generation Z’s behavioral intentions, it is necessary to create

positive attitudes and enhance consumer knowledge. This can be achieved through targeted

educational campaigns that provide comprehensive information about sustainable food.

These campaigns should aim to increase general awareness and specific knowledge about

the benefits and practices of sustainable food production and consumption. In addition,

clear and transparent information should be accessible. This includes transparent labeling,

online resources, and educational content that clearly explains the environmental, social,

and health benefits of sustainable food. By focusing on transparent and informative

marketing, engaging digital platforms, community and educational initiatives, and building

trust and credibility, producers can effectively cater to Generation Z’s preferences for

sustainable food. These strategies not only align with the attitudes and knowledge that

drive purchase intentions, but also foster long-term loyalty among consumers.

This study has several implications for research and society. It is suggested to pay

attention to the following in future studies: understanding the specific mechanisms through

interaction with each other and with external influences such as social norms and mar-

keting strategies; conducting longitudinal studies to reveal how attitudes and behaviors

toward sustainable food evolve over time within Generation Z; and comparing generational

differences in attitudes and behaviors toward sustainable food to highlight unique trends

and preferences across different age groups. The findings underscore the importance of

promoting sustainability as a societal value among Generation Z. Encouraging sustainable

food consumption not only benefits the environment but also supports ethical practices

and healthier lifestyles. By fostering positive attitudes and knowledge about sustainable

food, society can contribute to a broader shift toward more sustainable consumer behav-

iors. This shift is crucial for addressing global challenges such as climate change and biodiversity loss.

While the study provides valuable insights into sustainable food consumption among

Generation Z, several limitations should be considered. This study examines behavioral

intentions rather than actual purchasing behavior, so there can be a significant gap between

what people intend to do and what they actually do, influenced by situational factors

and real-world constraints. The next limitation is sample representativeness, because the

findings cannot be generalizable to Generation Z in other countries. Cultural, economic,

and social differences can influence attitudes and behaviors related to sustainable food

consumption. Despite certain limitations, the current study contributes to the body of

knowledge on sustainable food consumption by looking into the behaviors of Generation Z.

Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284 14 of 18

Supplementary Materials: The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://

www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su16177284/s1.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, D.J., A.Z.D., B.P. and S.S.; methodology, D.J., A.Z.D., B.P.

and S.S.; software, D.J., A.Z.D., B.P. and S.S.; validation, D.J., A.Z.D., B.P. and S.S.; formal analysis,

D.J. and A.Z.D.; investigation, D.J., A.Z.D., B.P. and S.S.; resources, D.J., A.Z.D., B.P. and S.S.; data

curation, D.J. and A.Z.D.; writing—D.J., A.Z.D., B.P. and S.S.; writing—review and editing, D.J. and

A.Z.D.; visualization, D.J. and B.P.; supervision, D.J.; project administration, D.J.; funding acquisition,

D.J., A.Z.D., B.P. and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration

of Helsinki and approved by the University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn Research Ethics

Committee (Ethics Committee number: 10/2022; date of approval: 30 June 2022).

Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement: The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request

from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest. References 1.

Ifeanyichukwu, C.D. Exploring critical factors influencing sustainable food consumption: A conceptual review. Eur. J. Bus. Innov.

Res. 2020, 8, 32–42. [CrossRef] 2.

van Bussel, L.M.; Kuijsten, A.; Mars, M.M.; van ‘t Veer, P. Consumers’ perceptions on food-related sustainability: A systematic

review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 341, 130904. [CrossRef] 3.

Verain, M.C.; Bartels, J.; Dagevos, H.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G. Segments of sustainable food consumers: A

literature review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 123–132. [CrossRef] 4.

Annunziata, A.; Scarpato, D. Factors affecting consumer attitudes towards food products with sustainable attributes. Agric. Econ.

2014, 60, 353–363. [CrossRef] 5.

Kalenjuk Pivarski, B.; Šmugovic´, S.; Tekic´, D.; Ivanovic´, V.; Novakovic´, A.; Tešanovic´, D.; Banjac, M.; Ðercˇan, B.; Peulic´, T.;

Mutavdžic´, B.; et al. Characteristics of traditional food products as a segment of sustainable consumption in Vojvodina’s

hospitality industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13553. [CrossRef] 6.

Jakubowska, D.; Sadílek, T. Sustainably produced butter: The effect of product knowledge, interest in sustainability, and consumer

characteristics on purchase frequency. Agric. Econ. 2023, 69, 25–34. [CrossRef] 7.

Tsolakis, N.; Anastasiadis, F.; Srai, J.S. Sustainability performance in food supply networks: Insights from the UK industry.

Sustainability 2018, 10, 3148. [CrossRef] 8.

Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [CrossRef] 9.

Donald, I.J.; Cooper, S.R.; Conchie, S.M. An extended theory of planned behaviour model of the psychological factors affecting

commuters’ transport mode use. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 39–48. [CrossRef]

10. Maichum, K.; Parichatnon, S.; Peng, K.C. Application of the extended theory of planned behavior model to investigate purchase

intention of green products among Thai. Consumers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1077. [CrossRef]

11. Aydın, H.; Aydin, C. Investigating consumers’ food waste behaviors: An extended theory of planned behavior of Turkey sample.

Clean. Waste Syst. 2022, 3, 100036. [CrossRef]

12. Ruzgys, S.; Pickering, G.J. Gen Z and sustainable diets: Application of the transtheoretical model and the theory of planned

behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 434, 140300. [CrossRef]

13. Savelli, E.; Murmura, F. The intention to consume healthy food among older Gen-Z: Examining antecedents and mediators. Food

Qual. Prefer. 2022, 105, 104788. [CrossRef]

14. Agustina, T.; Susanti, E.; Ali Saeed Rana, J. Sustainable consumption in Indonesia: Health awareness, lifestyle, and trust among

Gen Z and Millennials. Environ. Econ. 2024, 15, 82–96. [CrossRef]

15. Borah, P.S.; Dogbe, C.S.K.; Marwa, N. Generation Z’s green purchase behavior: Do green consumer knowledge, consumer social

responsibility, green advertising, and green consumer trust matter for sustainable development? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 4530–4546. [CrossRef]

16. Lăzăroiu, G.; Andronie, M.; Ut, ă, C.; Hurloiu, I. Trust management in organic agriculture: Sustainable consumption behavior,

Environmentally conscious purchase intention, and healthy food choices. Front. Public Health 2019, 19, 340. [CrossRef]

17. Priporas, C.V.; Stylos, N.; Fotiadis, A. Generation Z consumers’ expectations of interactions in smart retailing: A future agenda.

Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 77, 374–381. [CrossRef]

18. Gazzola, P.; Pavione, E.; Pezzetti, R.; Grechi, D. Trends in the fashion industry. The perception of sustainability and circular

economy: A gender/generation quantitative approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2809. [CrossRef]

Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284 15 of 18

19. Koch, J.; Frommeyer, B.; Schewe, G. Online shopping motives during the COVID-19 pandemic—Lessons from the crisis.

Sustainability 2020, 12, 10247. [CrossRef]

20. Meixner, O.; Malleier, M.; Haas, R. Towards sustainable eating habits of generation Z: Perception of and willingness to pay for

plant-based meat alternatives. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3414. [CrossRef]

21. Audina, G.A.; Pradana, M. The influence of green products and green prices on generation Z purchasing decisions. Int. J. Environ.

Eng. Dev. 2024, 2, 168–176. [CrossRef]

22. Hudayah, S.; Ramadhani, M.A.; Sary, K.A.; Raharjo, S.; Yudaruddin, R. Green perceived value and green product purchase

intention of Gen Z consumers: Moderating role of environmental concern. Environ. Econ. 2023, 14, 87–107. [CrossRef]

23. Fodor, M.; Vasa, V.; Popovics, A. Sustainable consumption from a domestic food purchasing perspective among Generation Z.

Decis.Mak. Appl. Manag. Eng. 2024, 7, 401–417. [CrossRef]

24. Pachołek, B.; Jakubowska, D.; Sady, S.; Matuszak, L.; Pyszka, A. Perception of discount stores promotional brochures among

consumers from generation Z. J. Mark. Mark. Stud. 2024, 4, 33–42. [CrossRef]

25. Armitage, C.; Christian, J. From attitudes to behaviour: Basic and applied research on the theory of planned behaviour. Curr.

Psychol. 2003, 22, 187–195. [CrossRef]

26. Zhao, X.; Xu, Z.; Ding, F.; Li, Z. The influencers’ attributes and customer purchase intention: The mediating role of customer

attitude toward brand. Sage Open 2024, 14, 21582440241250122. [CrossRef]

27. Pamungkas, D.D.A. The influence of perceived value and product involvement towards purchase intention mediated by attitudey.

J. World Sci. 2023, 2, 989–997. [CrossRef]

28. Dorce, L.C.; da Silva, M.C.; Mauad, J.R.C.; Domingues, C.H.F.; Borges, J.A.R. Extending the theory of planned behavior to

understand consumer purchase behavior for organic vegetables in Brazil: The role of perceived health benefits, perceived

sustainability benefits and perceived price. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 91, 104191. [CrossRef]

29. Setyarko, Y.; Noermijati, N.; Rahayu, M.; Sudjatno, S. The role of consumer green assurance in strengthening the influence of

purchase intentions on organic vegetable purchasing behavior: Theory of planned behavior approach. WSEAS Trans. Bus. Econ.

2024, 21, 1228–1241. [CrossRef]

30. Aprilia, A.; Dewi, H.E.; Pariasa, I.I.; Hardana, A.E. Factors affecting consumers’ preferences in purchasing organic vegetables

using a theory of planned behavior. IOP Conf.Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1306, 012028. [CrossRef]

31. Biasini, B.; Rosi, A.; Scazzina, F.; Menozzi, D. Predicting the adoption of a sustainable diet in adults: A cross-sectional study in

Italy. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2784. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

32. Xin, S.; Qian-Er, X.; Qiao, L. Predicting sustainable food consumption across borders based on the theory of planned behavior: A

meta-analytic structural equation model. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275312. [CrossRef]

33. Canova, L.; Bobbio, A.; Manganelli, A.M. Sustainable purchase intentions: The role of moral norm and social dominance

orientation in the theory of planned behavior applied to the case of fair trade products. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 31, 1069–1083. [CrossRef]

34. Jusuf, K.; Nuttavuthisit, K. Going from attitude to action: Analyzing how the orientations of sustainable food businesses influence

their business strategies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 4371–4381. [CrossRef]

35. Islam, Q.; Ali Khan, S.M.F. Assessing consumer behavior in sustainable product markets: A structural equation modeling

approach with partial least squares analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3400. [CrossRef]

36. Maduku, D.K. How environmental concerns influence consumers’ anticipated emotions towards sustainable consumption: The

moderating role of regulatory focus. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103593. [CrossRef]

37. Bulut, E.; Yildirim, B.; Brandão, A.; Vieira, B.M.; Tavares, V. Influence of sustainability on the purchase decision of products. Eur.

J. Appl. Bus. Manag. 2022, 8, 32–51.

38. Wong, S.L.; Hsu, C.C.; Chen, H.S. To buy or not to buy? Consumer attitudes and purchase intentions for suboptimal food. Int. J.

Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1431. [CrossRef]

39. Varah, F.; Mahongnao, M.; Pani, B.; Khamrang, S. Exploring young consumers’ intention toward green products: Applying an

extended theory of planned behavior. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 9181–9195. [CrossRef]

40. Meliniasari, A.R.; Mas’od, A. Understanding factors shaping green cosmetic purchase intentions: Insights from attitudes, norms,

and perceived behavioral control. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2024, 14, 1487–1496. [CrossRef]

41. Hsu, C.-L.; Chang, C.-Y.; Yansritakul, C. Exploring purchase intention of green skincare products using the theory of planned

behavior: Testing the moderating effects of country of origin and price sensitivity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 145–152. [CrossRef]

42. Chi, T.; Zheng, Y. Understanding environmentally friendly apparel consumption: An empirical study of Chinese consumers. Int.

J. Sustain. Soc. 2016, 8, 206. [CrossRef]

43. Dangelico, R.M.; Ceccarelli, G.; Fraccascia, L. Consumer behavioral intention toward sustainable biscuits: An extension of the

theory of planned behavior with product familiarity and perceived value. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 1–22. [CrossRef]

44. He, J.; Sui, D. Investigating college students’ green food consumption intentions in China: Integrating the theory of planned

behavior and norm activation theory. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1404465. [CrossRef]

45. Tzeng, S.-Y.; Ho, T.-Y. Exploring the effects of product knowledge, trust, and distrust in the health belief model to predict attitude

toward dietary supplements. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440211068855. [CrossRef]

Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284 16 of 18

46. Lee, E.J.; Bae, J.; Kim, K.H. The effect of environmental cues on the purchase intention of sustainable products. J. Bus. Res. 2020,

120, 425–433. [CrossRef]

47. Mahadeva, R.; Ganji, E.N.; Shah, S. Sustainable consumer behaviours through comparisons of developed and developing nations.

Int. J. Environ. Eng. Dev. 2024, 2, 106–125. [CrossRef]

48. Wang, X.; Pacho, F.; Liu, J.; Kajungiro, R. Factors influencing organic food purchase intention in developing countries and the

moderating role of knowledge. Sustainability 2019, 11, 209. [CrossRef]

49. Wang, H.; Ma, B.; Bai, R. How does green product knowledge effectively promote green purchase intention? Sustainability 2019, 11, 1193. [CrossRef]

50. Peschel, A.O.; Grebitus, C.; Steiner, B.; Veeman, M. How does consumer knowledge affect environmentally sustainable choices?

Evidence from a cross-country latent class analysis of food labels. Appetite 2016, 106, 78–91. [CrossRef]

51. Camilleri, A.R.; Larrick, R.P.; Hossain, S.; Patino-Echeverri, D. Consumers underestimate the emissions associated with food but

are aided by labels. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 53–58. [CrossRef]

52. Simeone, M.; Scarpato, D. Sustainable consumption: How does social media affect food choices? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 124036. [CrossRef]

53. Hartmann, C.; Lazzarini, G.; Funk, A.; Siegrist, M. Measuring consumers’ knowledge of the environmental impact of foods.

Appetite 2021, 167, 105622. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

54. Al-Kfairy, M.; Shuhaiber, A.; Al-Khatib, A.W.; Alrabaee, S.; Khaddaj, S. Understanding trust drivers of S-commerce. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23332. [CrossRef]

55. Robinson, C.; Ruth, T.; Easterly, R.G. (Tre), Franzoy, F. and Lillywhite, J. Examining consumers’ trust in the food supply chain.

J. Appl. Commun. 2020, 104, 5. [CrossRef]

56. Murphy, I.; Benson, T.; Lavelle, F.; Elliott, C.; Dean, M. Assessing differences in levels of food trust between European countries.

Food Control 2021, 120, 107561. [CrossRef]

57. László, V.; Szakos, D.; Csizmadiáné Czuppon, V.; Kasza, G. Consumer trust in local food system—Empirical research in Hungary.

Acta Aliment. 2024, 53, 165–174. [CrossRef]

58. Cook, B.; Costa Leite, J.; Rayner, M.; Stoffel, S.; van Rijn, E.; Wollgast, J. Consumer interaction with sustainability labelling on

food products: A narrative literature review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3837. [CrossRef]

59. Randoni, A.; Grasso, S. Consumers behaviour towards carbon footprint labels on food: A review of the literature and discussion

of industry implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 301, 127031. [CrossRef]

60. Tonkin, E.; Wilson, A.M.; Coveney, J.; Webb, T.; Meyer, S.B. Trust in and through labelling—A systematic review and critique. Br.

Food J. 2015, 117, 318–338. [CrossRef]

61. Yuan, R.; Jin, S.; Lin, W. Could trust narrow the intention-behavior gap in eco-friendly food consumption? Evidence from China.

Agribusiness 2023, 1–29. [CrossRef]

62. Rizomyliotis, I. Consumer trust and online purchase intention for sustainable products. Am. Behav. Sci. 2024. [CrossRef]

63. van der Zee, E. Regulatory structure underlying sustainability labels. In Sustainability Labels in the Shadow of the Law; Studies in

European Economic Law and Regulation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 22. [CrossRef]

64. Truong, V.A.; Lang, B.; Conroy, D.M. When food governance matters to consumer food choice: Consumer perception of and

preference for food quality certifications. Appetite 2022, 168, 105688. [CrossRef]

65. Hasan, M.M.; Al Amin, M.; Arefin, M.S.; Mostafa, T. Green consumers’ behavioral intention and loyalty to use mobile organic

food delivery applications: The role of social supports, sustainability perceptions, and religious consciousness. Environ. Dev.

Sustain. 2024, 6, 15953–16003. [CrossRef]

66. Rana, J.; Paul, J. Health motive and the purchase of organic food: A meta-analytic review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 162–171. [CrossRef]

67. Ares, G.; de Saldamando, L.; Giménez, A.; Claret, A.; Cunha, L.M.; Guerrero, L.; de Moura, A.P.; Oliveira, D.C.R.; Symoneaux, R.;

Deliza, R. Consumers’ associations with wellbeing in a food-related context: A cross-cultural study. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 40, 304–315. [CrossRef]

68. Fortunka, K.B. Factors affecting human health in the modern world. J. Educ. Health Sport 2020, 10, 75–81. [CrossRef]

69. Verain, M.C.D.; Raaijmakers, I.; Meijboom, S.; van der Haar, S. Differences in drivers of healthy eating and nutrition app

preferences across motivation-based consumer groups. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 116, 105145. [CrossRef]

70. Chen, M.-F. Modern health worries and functional foods. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 43, E1–E12. [CrossRef]

71. Nagaraj, S. Role of consumer health consciousness, food safety and attitude on organic food purchase in emerging market: A

serial mediation model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102423. [CrossRef]

72. Hansmann, R.; Baur, I.; Binder, C.R. Increasing organic food consumption: An integrating model of drivers and barriers. J. Clean.

Prod. 2020, 275, 123058. [CrossRef]

73. Ladwein, R.; Sanchez Romero, A.M. The role of trust in the relationship between consumers, producers and retailers of organic

food: A sector-based approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102508. [CrossRef]

74. Tm, A.; Kaur, P.; Ferraris, A.; Dhir, A. What motivates the adoption of green restaurant products and services? A systematic

review and future research agenda. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 30, 2224–2240. [CrossRef]

75. Konuk, A.F. The role of store image, perceived quality, trust and perceived value in predicting consumers’ purchase intentions

towards organic private label food. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 43, 304–310. [CrossRef]

Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284 17 of 18

76. De Farias, F.; Eberle, L.; Milan, G.S.; De Toni, D.; Eckert, A. Determinants of organic food repurchase intention

from the perspective of Brazilian consumers. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2020, 25, 921–943. [CrossRef]

77. Saari, U.A.; Damberg, S.; Frömbling, L.; Ringle, C.M. Sustainable consumption behavior of Europeans: The

influence of environmental knowledge and risk perception on environmental concern and behavioral

intention. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 189, 107155. [CrossRef]

78. Dimitrova, T.; Iliana, I.; Mina, A. Exploring factors affecting sustainable consumption behaviour. Adm.

Sci. 2022, 12, 155. [CrossRef]

79. Leidner, D.; Sutanto, J.; Goutas, L. Influencing Environmentally Sustainable Consumer Choice through

Information Transparency. In Proceedings of the 55th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences,

Virtual, 4–7 January 2022; pp. 4749–4758.

80. Gul, S.; Ahmed, W. Enhancing the theory of planned behavior with perceived consumer effectiveness and

environmental concern towards pro-environmental purchase intentions for eco-friendly apparel: A review

article. Bull. Bus. Econ. (BBE) 2024, 13, 784–791. [CrossRef]

81. Young, M.; Varpio, L.; Uijtdehaage, S.; Paradis, E. The spectrum of inductive and deductive research

approaches using quantitative and qualitative data. Acad. Med. 2019, 95, 1122. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

82. Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of Consumers’ Green Purchase Behavior in a Developing Nation:

Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [CrossRef]

83. Setyawan, A.; Noermijati, N.; Sunaryo, S.; Aisjah, S. Green product buying intentions among young

consumers: Extending the application of theory of planned behavior. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2018, 16, 145–154. [CrossRef]

84. Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and

reasoned action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [CrossRef]

85. Saxena, N.; Sharma, R. Impact of spirituality, culture, behaviour on sustainable consumption intentions.

Sustain. Dev. 2023, 32, 2724–2740. [CrossRef]

86. Al-Swidi, A.; Huque, S.M.R.; Hafeez, M.H.; Shariff, M.N.M. The role of subjective norms in theory of

planned behavior in the context of organic food consumption. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1561–1580. [CrossRef]

87. Askadilla, W.L.; Krisjanti, M.N. Understanding Indonesian green consumer behavior on cosmetic

products: Theory of planned behavior model. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 15, 7–15. [CrossRef]

88. Ru, X.; Wang, S.; Chen, Q.; Yan, S. Exploring the interaction effects of norms and attitudes on green travel

intention: An empirical study in eastern China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 1317–1327. [CrossRef]

89. Witek, L.; Kuzniar, W. Green purchase behaviour gap: The effect of past behaviour on green food

product purchase intentions among individual consumers. Foods 2024, 13, 136. [CrossRef]

90. Singh, M.P.; Chakraborty, A.; Roy, M. Developing an extended theory of planned behavior model to

explore circular economy readiness in manufacturing MSMEs, India. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 313–322. [CrossRef]

91. Kabir, M.R.; Islam, S. Behavioural intention to purchase organic food: Bangladeshi consumers’ perspective.

Brit. Food J. 2022, 124, 754–774. [CrossRef]

92. Kumar, S.; Gupta, K.; Kumar, A.; Singh, A.; Singh, R. Applying the theory of reasoned action to examine

consumers’ attitude and willingness to purchase organic foods. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 47, 118–135. [CrossRef]

93. Anupam, S.; Priyanka, V. Factors influencing Indian consumers’ actual buying behaviour towards organic

food products. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 473–483. [CrossRef]

94. Nuttavuthisit, K.; Thogersen, J. The importance of consumer trust for the emergence of a market for

green products: The case of organic food. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 323–337. [CrossRef]

95. Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Intention to purchase organic food among young consumers: Evidences from a

developing nation. Appetite

2016, 96, 122–128. [CrossRef]

96. Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. In Prediction and

change of health behavior: Applying the reasoned action approach. Psychology Press: New York, USA; Taylor &

Francis Group: New York, USA, 2010; pp. 3–21.

97. Malhotra, N. Questionnaire design and scale development. In the Handbook of Marketing Research:

Uses, Misuses and Future Advances; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 83–94. ISBN 1-4129-0997-X.

98. Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives.

Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [CrossRef]

99. Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and

Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284 18 of 18

measurement error. J. Mark. Res.

1981, 18, 39–50. [CrossRef]

100. Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics.

J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [CrossRef]

101. Zhong, F.; Li, L.; Guo, A.; Song, X.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, X. Quantifying the influence path of water

conservation awareness on water-saving irrigation behavior based on the theory of planned behavior

and structural equation modeling: A case study from Northwest China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4967. [CrossRef]

102. Savari, M.; Gharechaee, H. Application of the extended theory of planned behavior to predict Iranian

farmers’ intention for safe use of chemical fertilizers. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121512. [CrossRef]

103. Lavuri, R.; Jindal, A.; Akram, U.; Naik, B.K.R.; Halibas, A.S. Exploring the antecedents of sustainable

consumers’ purchase intentions: Evidence from emerging countries. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 280–291. [CrossRef]

Sustainability 2024, 16, 7284 19 of 18

104. Harjadi, D.; Gunardi, A. Factors affecting eco-friendly purchase intention: Subjective norms and ecological consciousness as

moderators. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 9, 2148334. [CrossRef]

105. Anjaka, R.G.; Syafrizal, A. The effect of attitude, subjective norm, perceived behaviour control on intention to reduce food waste

and food waste behaviour. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2022, 15, 329–337. [CrossRef]

106. Alam, S.S.; Ahmad, M.; Ho, Y.H.; Omar, N.A.; Lin, C.Y. Applying an extended theory of planned behavior to sustainable food

consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8394. [CrossRef]

107. Yazdanpanah, M.; Forouzani, M. Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to predict Iranian students’ intention to

purchase organic food. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 342–352. [CrossRef]

108. Hasan, H.; Suciarto, S. The influence of attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control towards organic food purchase

intention. J. Manag. Bus. Environ. 2020, 1, 132. [CrossRef]

109. Ham, M.; Jeger, M.; Frajman Ivkovic´, A. The role of subjective norms in forming the intention to purchase green food. Econ. Res.

-Ekon. Istraživanja 2015, 28, 738–748. [CrossRef]

110. Shin, Y.H.; Hancer, M. The role of attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and moral norm in the intention to

purchase local food products. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2016, 19, 338–351. [CrossRef]

111. Kumar, B. Theory of Planned Behaviour Approach to Understand the Purchasing Behaviour for Environmentally Sustainable Products

2012; No. WP2012-12-08; Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad, Research and Publication Department: Ahmedabad, Indian, 2012.

112. Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer attitude-behaviour gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics

2006, 19, 169–194. [CrossRef]

113. Dipietro, R.B.; Remar, D.; Parsa, H.G. Health consciousness, menu information, and consumers’ purchase intentions: An empirical

investigation. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2016, 19, 497–513. [CrossRef]