Preview text:

This art icle was downloaded by: [ 155. 198.30.43] On: 15 Sept ember 2016, At : 08: 44

Publisher: Inst it ut e f or Operat ions Research and t he Management Sciences (INFORMS)

INFORMS is locat ed in Maryland, USA Management Science

Publicat ion det ails, including inst ruct ions for aut hors and subscript ion inf ormat ion:

ht t p: / / pubsonline. inf orms.org

Capi t al Market s and Fi rm Organi zat i on: How Financial

Devel opment Shapes European Cor por at e Groups

Sharon Belenzon, Tomer Berkovit z, Luis A. Rios, To cite this article:

Sharon Belenzon, Tomer Berkovit z, Luis A. Rios, (2013) Capit al Market s and Firm Organizat ion: How Financial Devel opment

Shapes European Corporat e Groups. Management Science 59(6): 1326-1343. ht t p: / / dx.doi. org/ 10. 1287/ mnsc. 1120. 1655

Full terms and conditions of use: http:/ / pubsonline.informs. org/ page/ terms-and-condit ions

This art icle m ay be used only for t he pur poses of research, t eaching, and/ or pr ivat e st udy. Com m ercial use

or syst em atic dow nloading ( by robot s or ot her aut om at ic processes) is prohibit ed wit hout ex plicit Publisher

appr oval, unless ot herwise not ed. For m ore infor m at ion, cont act perm issions@infor m s.or g.

The Publisher does not warrant or guarant ee t he art icle’s accuracy, com plet eness, m erchant abilit y, fit ness

for a part icular purpose, or non- infringem ent . Descript ions of, or r efer ences t o, pr oduct s or publicat ions, or

inclusion of an advert isem ent in t his ar t icle, neit her const it ut es nor im plies a guarant ee, endorsem ent , or

support of claim s m ade of t hat product , publicat ion, or service. Copy right © 2013, I NFORMS

Please scroll down for article—it is on subsequent pages

INFORMS is t he largest professional societ y in t he world f or prof essional s in t he fields of operat ions research, management science, and anal yt ics.

For more inf ormat ion on INFORMS, it s publicat ions, membership, or meet ings visit ht t p: / / www.inf orms. org MANAGEMENT SCIENCE

Vol. 59, No. 6, June 2013, pp. 1326–1343

ISSN 0025-1909 (print) ISSN 1526-5501 (online)

http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1120.1655 © 2013 INFORMS

Capital Markets and Firm Organization: d.

How Financial Development Shapes European Corporate Groups eserve s r ight Sharon Belenzon ll r

Fuqua School of Business, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708, sb135@duke.edu y, a Tomer Berkovitz e onl

Graduate School of Business, Columbia University, New York, New York 10027, tb2122@columbia.edu l us Luis A. Rios

Fuqua School of Business, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708, luis.rios@duke.edu rsona pe or

We investigate the effect of financial development on the formation of European corporate groups. Because

cross-country regressions are hard to interpret in a causal sense, we exploit exogenous industry measures 44 . F

to investigate a specific channel through which financial development may affect group affiliation: internal

capital markets. Using a comprehensive firm-level data set on European corporate groups in 15 countries, we t 08:

find that countries with less developed financial markets have a higher percentage of group affiliates in more

capital-intensive industries. This relationship is more pronounced for young and small firms and for affiliates of

large and diversified groups. Our findings are consistent with the view that internal capital markets may, under 2016, a

some conditions, be more efficient than prevailing external markets, and that this may drive group affiliation even in developed economies.

Key words: corporate groups; financial development; internal capital markets

History: Received May 19, 2009; accepted June 13, 2012, by Bruno Cassiman, business strategy. Published

online in Articles in Advance December 19, 2012, and updated February 1, 2013. 1. Introduction

dependent on external capital are more likely to be

This study seeks to deepen our understanding of

group affiliates, especially in countries with a low

firm organization and boundaries by examining how

level of financial development. 155.198.30.43] on 15 September

regional institutional differences affect the propen-

The formation of groups is often viewed as an

sity of companies to form groups within 15 Western

intermediating organizational response to missing or g by [

European countries. We focus on one specific chan-

inefficient markets (Leff 1978). This is an appealing

nel through which incentives to band together may

argument with important strategy and policy impli- s.or m

operate: internal capital markets (ICMs).1 In our set-

cations, but its examination poses three significant or

ting, federations of firms (for example, the German

empirical challenges. First, although it predicts that nf i

konzern) are usually referred to as corporate groups

group formation should be driven by market devel- rom

(Faccio et al. 2010). We test and quantify the effect

opment, groups themselves may actually restrain the d f

of ICMs on group formation by ranking industries

development of the institutions they mimic (Khanna de

according to their level of external capital needs

and Yafeh 2007). Thus, groups that may have arisen oa nl

while also ranking countries according to their rela-

for reasons other than a response to inefficient mar- ow

tive levels of financial development. Then we com-

kets may go on to hamper subsequent financial devel- D

pare how the distributions of group-affiliated firms

opment by limiting arms-length transactions. Second,

across industries vary across nations. Thus we test

omitted or latent macro variables can be correlated

empirically whether firms in industries that are more

with both financial development and the prevalence

of groups. Third, group affiliates are often privately

held corporations under intricate ownership arrange-

1 Section 2 relates our work to prior studies on groups and

ments, rendering many groups “relatively invisible”

ICMs (e.g., Khanna and Palepu 2000, Khanna and Yafeh

2005, Almeida and Wolfenzon 2006, Cestone and Fumagalli 2005,

(Granovetter 1995). This is particularly likely in the Morck et al. 2005).

face of regulatory pressure to be discrete about the 1326

Belenzon, Berkovitz, and Rios: Capital Markets and Firm Organization

Management Science 59(6), pp. 1326–1343, © 2013 INFORMS 1327

internal reallocation of resources, which may be

indices, which consider the stock market and bank-

perceived as detrimental to minority shareholders

ing systems for each country (Beck et al. 2000; data

(Scharfstein and Stein 2000) or even anticompetitive.

updated in 2007). Though our focal countries are rel-

This paper is the first to tackle all three of these

atively wealthy and enjoy developed legal environ-

challenges. First, we mitigate the reverse causal-

ments, they nonetheless exhibit measurably different

ity concern by focusing on a specific mechanism—

levels of financial institution development accord- d.

internal capital markets. If groups replace inefficient

ing to these fine-grained indices. To supplement the

financial markets, we would expect (i) a higher prob-

accounting measures of financial development, we

ability of group affiliation within capital-intensive

also use measures from the World Economic Forum eserve s r

industries, where affiliates are more likely to bene-

Executive Opinion Survey, 2006–2007 (Claessens and

fit from a group’s ICM, and (ii) this relationship to

Laeven 2003), which capture local access to equity and ight

be stronger in countries with less developed finan- loan markets. ll r

cial institutions. A pure reverse causality argument

Our findings strongly support the ICM hypothe- y, a

is unlikely to explain the interaction effect between

sis. We find that high-dependence industries have e onl

these two because a country’s financial develop-

disproportionately more group affiliated firms than

ment is constant across industries, and it is not

low-dependence industries, and that this difference l us

likely to account for within-country systematic dif-

declines as financial development increases. This rsona

ferences in group affiliation between high- and low-

result suggests that less developed markets dispro- pe

dependence industries. We employ a difference-in-

portionately foster the formation of corporate groups or

differences strategy to determine whether the differ-

in sectors where internal capital markets are espe-

ence in group affiliation between higher and lower

cially beneficial. Consistent with the view that small 44 . F

external dependence industries is more stark for

and young firms are likely to face higher costs for

countries with lower financial development.

outside capital (Gompers 1995), our results also show t 08:

Second, we develop a comprehensive data set on

that the effect of financial development on group affil-

group affiliation and financial information covering

iation is more significant for smaller and younger 2016, a

over 139 thousand (mostly private) European firms.

firms. Our results are also strong for firms affiliated

Our estimation strategy allows us to substantially mit-

with larger and more diversified groups, where ICMs

igate unobserved industry and country heterogeneity,

are likely to be more substantial.

in addition to controlling for both country and indus-

try fixed effects, by performing more refined tests of 2. Empirical Setting

whether variation in the relationship between exter-

nal dependence and financial development among 2.1. European Corporate Groups

firms is consistent with the ICM theory.

Group definition is important in our study because

Third, to mitigate the invisibility problem, we con-

there are many incongruous conceptualizations of

struct detailed ownership and control hierarchies for

what a group is. Since Leff’s (1978) seminal work,

groups by exploiting the strict reporting requirements

scholars have found many different examples of 155.198.30.43] on 15 September

of the European Union (EU), where both public and

“firms bound together in some formal and/or infor-

private firms have to file annual reports detailing

mal ways, characterized by an ‘intermediate’ level of g by [

ownership and financial information.

binding” (Granovetter 1995, p. 95). Mostly within the s.or

Because ICM transactions themselves are hard to

context of emerging economies, the business-group m

observe, we employ an indirect approach (e.g., Dahl

literature has emphasized features such as concen- or nf

et al. 2002) to capture the impact of ICMs. We iden-

trated ownership, reciprocal trading arrangements, i

tify conditions where internal capital should be more

and familial control (Khanna and Rivkin 2001, 2006; rom

beneficial and systematically test whether these con-

Kester 1992). Concurrently, the “pyramidal groups” d f

ditions are associated with higher propensity for firms

literature has focused mainly on formal ownership de

to be organized in groups. One advantage of our indi-

structures and the often darker sides of group orga- oa nl

rect approach is that it relies on the revealed prefer-

nization within developed and developing economies ow

ences of firms, rather than on reporting which may

(Almeida and Wolfenzon 2006, Morck 2005). D

be polluted by firms’ self-serving interests.

We do not take a position on the extent to which

We follow the methodology employed by Rajan

these streams map onto one another, nor do we

and Zingales (1998) to rank industries according

claim that our empirical sample overlaps directly with

to their dependence on external sources of fund-

any of these types of groups. We are, however, very

ing, taking into consideration external funds depen-

precise in defining what our subjects are. Our paper

dence and trade credit. Then we rank the 15 West-

focuses on a set of Western European economies that

ern European countries in our sample according to

(i) have consistently defined groups, based on histor-

their level of financial development using World Bank

ical, institutional, and economical traditions; (ii) exist

Belenzon, Berkovitz, and Rios: Capital Markets and Firm Organization 1328

Management Science 59(6), pp. 1326–1343, © 2013 INFORMS

within a narrow range of economic development, so

one these three criteria: (i) the firm is a subsidiary

that we do not commingle developed and developing

(that is, it has a controlling parent company), (ii) it

economies; and (iii) still have enough heterogeneity

controls another firm (that is, it has at least one sub-

in their financial institutions and mix of industries,

sidiary), and (iii) it has the same controlling share-

so that we may observe the impact of interactions

holder as at least one other firm.

between industry capital demand and country eco-

It is important to note that we do not attempt d. nomic development.

to capture every single firm or every single group

We rely on the ownership-based EU definition

within our focal countries. For our empirical strat-

of groups to ensure the consistent criteria needed

egy to work, it is only necessary that our sampling is eserve s r

for our empirical strategy. The concept of corporate

representative of the distribution of industries within

groups within a Western European context is codified

a given country, along the dimensions of external ight

in legal, cultural, and economic institutions, which

dependence and country financial development, and ll r

reduces our reliance on theoretical assumptions about

that it is not biased by systematic misrepresenta- y, a

boundary conditions for group membership.2 Thus,

tion of firms missing ownership or financial infor- e onl

our goal in this paper is not so much to show whether

mation. Section 3 details our data construction and

groups exist in Europe as it is to explore whether the

methodology for characterizing firms as group affili- l us

heterogeneity in their prevalence across countries and

ates, including a detailed discussion of our mitigation rsona

industries provides evidence of an ICM mechanism

of potential bias issues. We also perform a battery of pe behind their formation.

tests to ensure that our results are robust to alternate or

Though prior work has found ownership links to be sample inclusion criteria.

tepid determinants of group membership in emerging

Our focused empirical approach may limit the 44 . F

markets (Khanna and Rivkin 2006), there are strong

generalizability of our study, because groups (in

reasons to believe that they reliably demarcate group

the broader context) are heterogeneous across time t 08:

membership in our setting. In the EU, courts and gov-

and place (Khanna and Rivkin 2001). Nonetheless,

ernment agencies specifically emphasize the concept

because our study focuses on how relative market 2016, a

of control as a condition for group affiliation. This

efficiency drives the partial internalization of transac-

refers to the direct and indirect ownership stakes the

tions within groups, rather than within discrete firms,

controlling shareholder has in each of the corporate

our findings should be relevant in other settings

group affiliates (Windbichler 2000). Additionally, the

where “the group is an integral part of the resource

notion of corporate groups is part of the economic

allocation mechanism,” (Goto 1982, p. 60). As well,

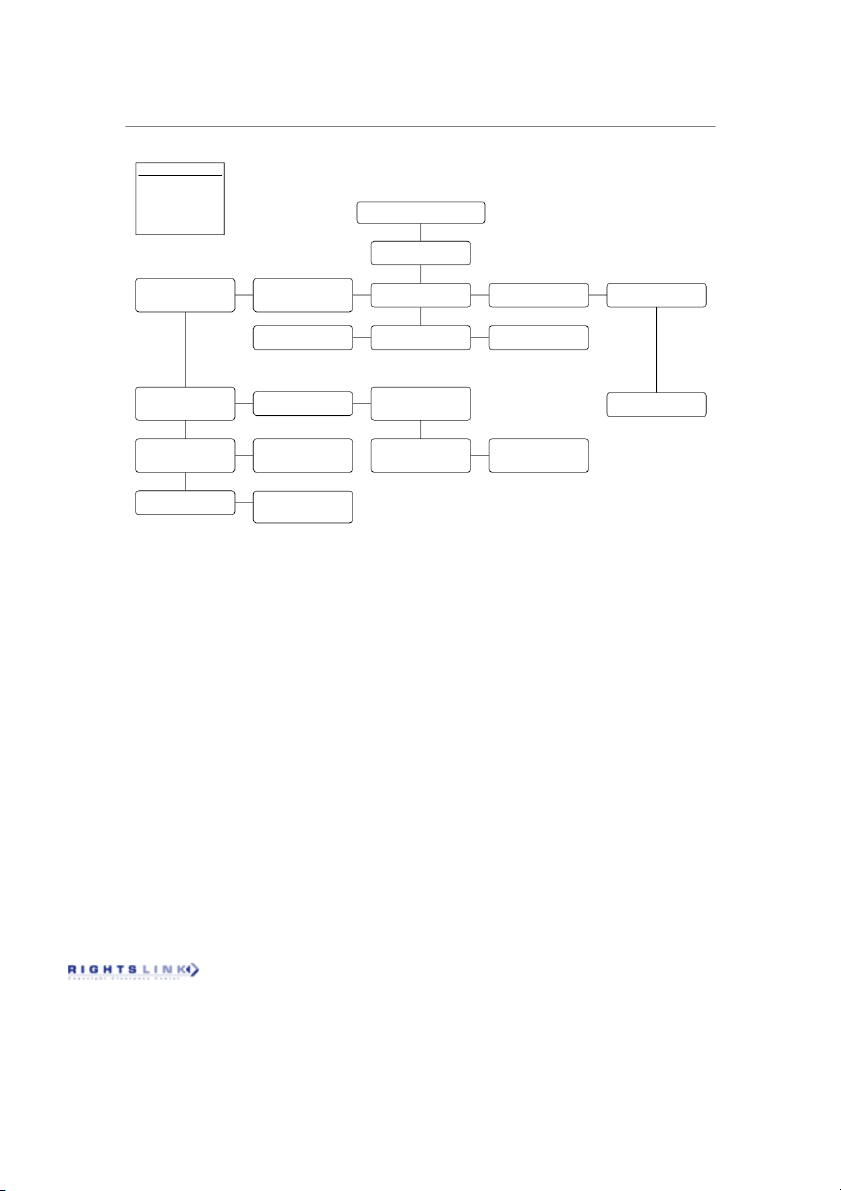

environment in the EU. For example, Figure 1 shows

we document conditions under which, despite con-

the ownership structure of a representative group,

ventional wisdom in strategy, financial capital may be

Berge y Compania, which describes itself as one of

a valuable resource even in developed economies.

the major Spanish corporate groups.3 Similarly, a vast 2.2. Internal Capital Markets

number of firms in our sample feature their affiliation

as part of their corporate identity, by including, for

ICMs have been observed in hybrid organizations 155.198.30.43] on 15 September

example, the name of the corporate group in their let-

ranging from loosely tied groups to vertically inte-

grated conglomerates, albeit for reasons that vary (e.g.,

terheads, websites, and logos. Also, it is common to

Perotti and Gelfer 2001, Cestone and Fumagalli 2005, g by [

highlight their association with other group members

Gopalan et al. 2007). For example, a 2011 metastudy s.or

in their communication materials. m

of the broad group literature (Carney et al. 2011)

The EU definition is also consistent with much or

found that financial infrastructure development gen- nf

academic work that focuses on corporate groups i

erally moderates group affiliation negatively, which

(e.g., Deloof 1998, Morck 2005, Smångs 2006, Cestone

lends support to the ICM hypothesis. Similarly, ICMs rom

and Fumagalli 2005). Following previous work, we d f

have been found to lower the cost of capital for many

classify a firm as a group affiliate if it satisfies at least de

types of groups and give them access to financial oa

institutions (Khanna and Palepu 2000, Gertner et al. nl

2 Direct references to corporate groups are found throughout the

1994, Weinstein and Yafeh 1998). But ICMs need not ow

EU governing documents, for example, the Fourth Directive of D

arise solely as a response to missing or significantly

the Council of European Communities (1978), where account-

underdeveloped markets.4 Even in countries with

ing reporting regulations for groups are stipulated: “Whereas,

when a company belongs to a group, it is desirable that group

accounts giving a true and fair view of the activities of the group

4 An issue beyond the scope of this paper is whether companies

as a whole be published” (http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/

could “migrate” to the most efficient financial environments within

LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31978L0660:en:HTML, accessed Novem-

Europe and circumvent the deficiencies of their home country ber 28, 2012).

systems. The current consensus on firm mobility in Europe is that

3 See the Berge corporate website main page: http://www

it is still rare, as it is largely constrained by taxation and jurisdiction .bergeycia.es. issues (Bratton et al. 2009).

Belenzon, Berkovitz, and Rios: Capital Markets and Firm Organization

Management Science 59(6), pp. 1326–1343, © 2013 INFORMS 1329 Figure 1

Example of a European Corporate Group’s Ownership Strucutre Berge y Compañía Spain Marine Cargo Affiliates: 71 Berge y Compañía Ownership Levels: 4 Marine Cargo d. Berge y Compañía SA eserve 99.99% SIC 872 57% SIC 501 s r 72.27% SIC 489 59.35% SIC 491 90% SIC 506 Berge Negocios Sociedad Española Berge Automoción Isofoton Europman SA ight Marítimos Chrysler Keep sales 162,238 sales 188,798 sales 49,490 ll r sales 441 sales 269,232 52.81% SIC 501 90% SIC 501 75% SIC 501 y, a Subaru España Hyundai España Ssangyong España sales 50,524 sales 799,909 sales 273,186 e onl l us 50% SIC 499 75% 100% SIC 449 SIC 499 50% SIC 506 rsona Sobrinos del Berge Marítimo Agencia Marítima pe Manuel Camara Condeminas SA Kalmar España or sales 22,800 sales 153,969 sales 2,448 sales 14,776 51% SIC 499 99.98% SIC 499 65% SIC 499 51% SIC 499 44 . F Consignaciones Sociedad Auxiliar Agencia Marítima Agencia Marítima Asturianas Puerto Pasajes Condeminas Madrid Condeminas Málaga t 08: sales 10,295 sales 14,978 sales 1,823 sales 5,693 60% SIC 421 60% SIC 421 Cortravel SA Transportes Hermanos 2016, a sales 836 Cortes sales 3,994

Notes. Data are as of 2007. A representative sample is shown. Units are in thousands of dollars. Horizontal lines: companies are on the same level; vertical

lines: top company owns the bottom company.

well-developed financial institutions, ICMs can still

work both through subtle mechanisms such as guar-

provide access to capital under more favorable terms

antees for capital raising and through more direct

(Cetorelli and Goldberg 2012), mitigate asymmetric

ones, like funding one affiliate using cash flow from

information between firms and capital sources (Myers

another (this is often called “corporate socialism”).

and Majluf 1984), or provide better governance mech-

Often, a corporate group may have financing sub-

anisms via ownership than would be possible under

sidiaries in various markets, which are able to raise 155.198.30.43] on 15 September

lending relationships (Wulf 2009). Furthermore, these

capital on favorable terms as a result of guaran-

are likely to be more pronounced within countries

tees provided by the controlling firm. For example, g by [

where financial institutions are less sophisticated and

Novartis’ subsidiaries regularly issue debt that is s.or

information and transparency are reduced, even if

guaranteed by the parent, such as a $2 billion issue m

overall capital liquidity is not substantially lower.

by Novartis Capital Corp., the $3 billion issued by or nf

However, direct evidence of ICM remains scarce,

the group’s Bermuda unit, Novartis Securities Invest- i

especially within European corporate groups (De Haas

ment, and the E1.5 billion issued by Novartis Finance rom

and Van Lelyveld 2010). Often, ICM transactions occur

(Luxemburg). In all three cases, the debt was guar- d f

between sophisticated corporate group members and

anteed by the parent and accompanied by statements de

involve valuable yet intangible capital resources such

that obliquely acknowledged the ICM nature of these oa nl

as loan guarantees or deposit smoothing (Cremers

transactions, such as, “proceeds will be used for inter- ow

et al. 2011), which are inherently difficult to observe

company refinancing purposes in connection with the D

and quantify. This intangibility may be exacerbated by

pending 0 0 0 acquisition, as well as for general corpo-

institutional pressures to be discrete regarding inter- rate purposes.”

nal reallocations of resources, because these may be

Additional direct evidence on the functionality

detrimental to minority shareholders (Scharfstein and

and prevalence of ICM transactions within corporate

Stein 2000) or even anticompetitive.

groups can be found in Thompson Reuter’s DealScan

Within the relatively developed countries in our

database. By manually sifting through this database,

study, where sophisticated legal and financial instru-

we were able to identify numerous instances of loan

ments are common, we would then expect ICM to

guarantees made by the group parent for the benefit

Belenzon, Berkovitz, and Rios: Capital Markets and Firm Organization 1330

Management Science 59(6), pp. 1326–1343, © 2013 INFORMS

of an affiliate. We did not perform statistical anal-

To deal with these issues, we analyze a key channel

ysis on these data, because a systematic treatment

through which financial development affects group

of these is beyond the scope of our paper. How-

affiliation: internal capital markets. If groups form

ever, our exploratory findings in the data set were

as a substitute for underdeveloped financial markets,

consistent with what we would expect. Many of the

we should observe a higher probability of group

transactions were in industries with a high level

affiliation for firms with a higher external financ- d.

of external capital dependency (e.g., shipping and

ing needs, because they would benefit more from

energy). More detailed searches to track down orig-

access to internal capital markets. This should be

inal filings for a random sample of these transac-

more pronounced in countries with relatively low eserve s r

tions also revealed intricate mortgage agreements and

financial development, because these countries have

securitization documents. For example, M. J. Maillis,

more limited alternatives to raising capital. We fol- ight

SA, an industrial manufacturing group reported in

low the methodology of Rajan and Zingales (1998) ll r

its 2011 filings that “the parent company has given

and rank the degree of reliance on external capital y, a

guarantees for a total of 4.2 million Euro toward

for all major industries using data from the United e onl

obligations of the Group’s subsidiary companies.”

States. The logic behind this strategy is this: (i) The

Similarly, Cadence Design Systems’ 2006 10-Q filings

United States has the most advanced capital markets l us

report that it “unconditionally guaranteed” the obli-

in the world, where publicly traded firms face the rsona

gations amounting to $160 million of its Irish sub-

least friction in accessing finance. Thus, the amount pe

sidiary Castlewilder for it to obtain a loan, and Fred

of external finance used by these companies is a good or

Olsen Energy guaranteed a $1.5 billion loan made to

measure of their industry’s intrinsic (e.g., technolog-

its subsidiary Dolphin International. Given the intri-

ical) demand for external finance. (ii) Strict disclo- 44 . F

cacy of these arrangements, it is not surprising that

sure requirements result in comprehensive data on

within academic work ICMs are often documented

funding sources. (iii) Although U.S. industry data are t 08:

through inference, such as by observing correlated

exogenous to European firms, the major industries are

credit patterns (e.g., Dahl et al. 2002) or relying on

structurally and technologically similar, so an indus- 2016, a

financial statement analysis (Deloof 1998).

try’s dependence on external funds, as measured in

Our central question then is whether the benefits of

the United States, is likely to be a good measure of

ICM themselves foster group formation, or whether

that industry’s dependence on external funds for the

these well-documented ICM channels merely reflect

countries in our setting (for example, chemicals are

an ancillary benefit of group affiliation. To properly

capital intensive, regardless of locale). (iv) Groups

address this, we systematically document the distri-

are virtually nonexistent in the United States, so U.S.

butions of groups across industries and countries, and

firms’ demand for external funds is a good proxy

expect groups to be more prevalent wherever ICM

for industry-driven capital demands in the absence of would be more valuable. options for group ICMs.

Two main assumptions are needed for our iden- 3. Methods

tification strategy to work: that technological differ- 155.198.30.43] on 15 September

ences explain why some industries rely on external 3.1. Empirical Strategy

funds more than others, and that these differences are g by [

We study the effect of financial development on

relatively stable across countries and orthogonal to s.or

group affiliation by testing whether corporate groups

regional financial development. m

substitute for less developed financial institutions.

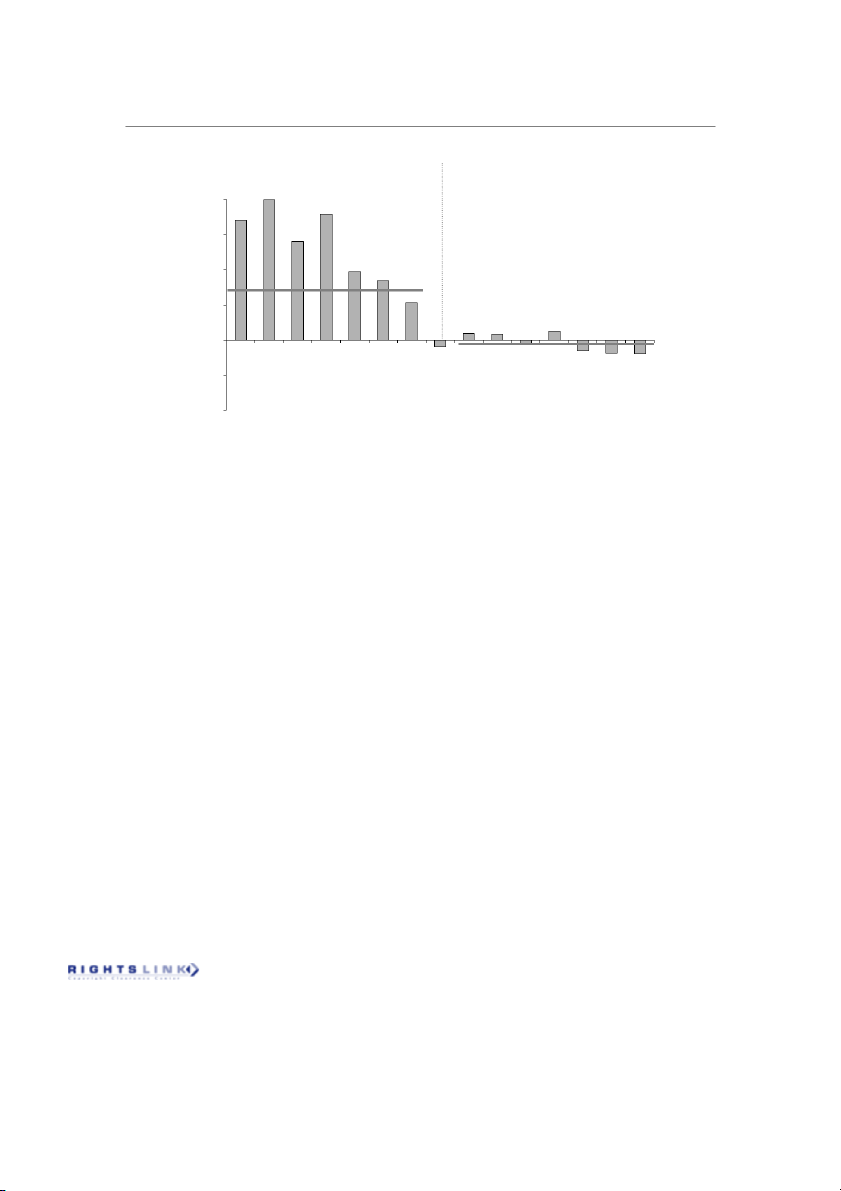

Figure 2 shows the logic behind our empirical strat- or nf

Here, reverse causality between group formation and

egy. We can readily see that nations with lower scores i

financial development poses a serious identification

in terms of stock market development also have rom

challenge. This is because we might expect lower

considerably larger shares of group-affiliated firms d f

overall incentives for financial markets to improve

in industries with high external capital dependence de

in regions where groups already facilitate financing.

(we define the measures used in the next section). oa nl

Thus, groups may actually hamper financial devel-

Though in our regressions we introduce a number ow

opment rather than be a response to lower develop-

of controls to better understand these unconditional D

ment (Khanna and Yafeh 2007). An additional issue

relationships, this nonparametric pattern is prima

is that simply examining a firm-specific proxy for

facie consistent with the hypothesis that groups pro-

external financial dependence would measure exter-

vide an alternative source of capital within less devel-

nal funding set in equilibrium rather than the demand oped financial markets.

for external funding, and thus suffer from endogene-

ity problems. The use of aggregate and exogenous 3.2. Data

industry variation should be especially advantageous

Our data set relies on detailed ownership links in this setting.

and accounting information from the 2007 version

Belenzon, Berkovitz, and Rios: Capital Markets and Firm Organization

Management Science 59(6), pp. 1326–1343, © 2013 INFORMS 1331 Figure 2

Differences in Group Affiliation Between Industries with High and Low External Financial Dependence Across Countries 739 0.20 13,721 4,356 d. 0.15 2,260 eserve 36,438 0.10 s r 1,372 filiated firms ight 4,216 0.05 ll r y, a 26,221 14,222 1,611 633 3,567 859 27,146 1,402 0 e onl ference in % of af y l us Dif and ce ain en Ital an – 0.05 ed Sp Ausrtia Irel Greece Fr Norway enmark Finland t Britain Belgium Germany D etherlands Sw rsona N rea G Switzerland pe – 0.10 Stock market development or

Notes. This figure describes the difference in the percentage of affiliates between the highest and lowest quartiles of external financial dependence across

countries. Countries are ranked according to their financial development in ascending order. Financial development is based on Beck et al. (2000; data updated 44 . F

in 2007) and is the average of stock market value traded and stock market capitalization over GDP (averaged over the period 2003–2005). External finance

dependence is computed at the three-digit SIC level based on Compustat firms in 1980–2004, and is defined as the ratio between capital expenditures minus t 08:

cash flow from operations and capital expenditures. The number above each bar indicates the number of firms. The horizontal lines represent the sample

difference in percentage of affiliated firms between high and low external dependence for below- and above-median country stock market development. 2016, a

of Amadeus, a comprehensive European database

Finally, we reclassify or drop some firms and groups

by Bureau van Dijk (BVD), which covers both pri-

according to a set of refining criteria.

vate and public firms. The main tests in this paper

Ownership Links. To ensure that the ownership

exploit cross-sectional variation across firms, indus-

links we observe represent actual control, they must

tries, and countries. For robustness, we also employ

include a minimum share of voting rights. For private

an alternate panel estimation approach. BVD has

firms, a link is considered controlling if it has at least

developed a format that standardizes financial items

50% of the voting rights. For public firms, which typ-

across the various countries’ filing regulations, bal-

ically have a more dispersed ownership, the thresh-

anced with a realistic representation of European com-

old is set at 20%, consistent with previous literature

pany accounts. A key advantage of these data is that

on public firms (e.g., La Porta et al. 1999, Faccio and 155.198.30.43] on 15 September

by including private as well public firms, we cap-

Lang 2002). Our results are not sensitive to alterna-

ture a wide range of firm sizes. Because Amadeus

tive plausible specifications of these thresholds. It is g by [

includes information for industrial firms only, we add

important to note that links between firms need not s.or

information for financial institutions from BankScope,

be direct. For example, if firm A owns 50% of firm B, m

which provides ownership information for about ten

and firm B owns 50% of firm C, then firm A has a or nf

thousand banks. The final estimation sample includes 25% ownership link to C. i

139,254 firms, 50.6% of which are affiliated with 26,711

Corporate Group Definition. We define a corporate rom groups.5

group as a set of at least two legally distinct firms d f 3.2.1.

Sample Construction. In this section, we

where one of them is a controlling ultimate owner de oa

delineate our three-step methodology for construct-

according to the ownership links identified above. nl

ing the data and describe our sample. We first iden-

Specifically, this means that for a firm to be a group ow

tify which of the dyadic interfirm ownership links

affiliate, it must meet at least one of these criteria: D

reported in Amadeus or BankScope represent a con-

(i) the firm is a subsidiary (that is, it has a controlling

trolling interest. Then we use this information to map

parent company), (ii) it controls another corporation

hierarchies of ownership and infer group structure.

(that is, it has at least one subsidiary), or (iii) it has

the same controlling shareholder as at least one other corporation.

5 One has to be cautious when comparing these percentages with

Estimation Sample Selection. We impose two addi-

previous studies on business groups (e.g., La Porta et al. 1999,

Faccio and Lang 2002) because our sample includes private firms;

tional conditions before finalizing our baseline estima-

previous studies focused on public firms.

tion sample. First, banks are excluded, because they

Belenzon, Berkovitz, and Rios: Capital Markets and Firm Organization 1332

Management Science 59(6), pp. 1326–1343, © 2013 INFORMS

are likely to face much different capital considerations

context is consistent with extant work (e.g., Almeida

when joining groups (the affiliation decisions of finan-

and Wolfenzon 2006), and we stress that whether a

cial institutions are beyond the scope of this paper).

country’s level of development along any measure is

Second, we deal with the fact that many countries

higher or lower merely reflects whether that channel

in our sample differ in their mandatory reporting

is more or less conducive to industrial firms’ access

requirements for small firms. Because our empir- to external capital.7 d.

ical approach investigates the interaction between

We use four accounting measures and four sur-

industry and country measures, while controlling for

vey measures of financial development. To capture

country- and industry-level effects, our results should

the relative development of various types of finan- eserve s r

not be sensitive to this type of cross-country varia-

cial institutions within a country, we rely on World

tion in reporting patterns. Furthermore, there is no

Bank indices (following Beck et al. 2000; data updated ight

reason to expect within-country systematic variation

in 2007), which reflect the development of a coun- ll r

in reporting patterns across industries. This would be

try’s stock markets and banking systems. Our empir- y, a

a case where in a given country small firms in one

ical approach independently evaluates the interaction e onl

industry would comply with voluntary reporting, but

of each of these measures with each of the measures

somehow small firms in the same country but in a

of external capital dependence. This is because our l us

different industry would not comply. Nonetheless, we

various measures for development need not be per- rsona

mitigate any potential bias of voluntary disclosure by

fectly correlated—for example, a country may have pe

eliminating all firms that generate less than $10 mil-

an exceptionally well-developed banking system, but or

lion in annual sales. This is a conservative threshold

stock markets that are only average relative to other

based on our research on BVD’s data collection pro-

countries. Therefore, a composite measure of devel- 44 . F

cesses, which included multiple interviews with their

opment that aggregates all measures might attenuate

experts and top executives. We perform a number of important variation. t 08:

robustness checks to ensure that our size thresholds

For stock market development, we use (i) stockmar- do not introduce sample bias.

ket volume/gross domestic product (GDP) and (ii) stock

market capitalization/GDP. We define stock market vol- 2016, a 3.2.2.

Industry External Dependence. To thor-

ume as the value of total shares traded on the stock

oughly explore the interactions between financial

exchange (a “flow” measure aiming at capturing stock

development and external dependence, we use sev-

market liquidity), and stock market capitalization as the

eral measures of each and interact them in various

value of all stocks listed on the equity markets, aiming

combinations. For external dependence we use three

at capturing the size of production organized in pub-

distinct measures. External funds dependence is calcu-

licly listed firms. For the banking system, we use pri-

lated as the ratio between capital expenditures net

vate credit/GDP, the ratio of private credit by deposit

of cash flows from operations and capital expen-

money banks and other financial institutions to GDP,

ditures. This measure captures the fraction of the

and bank deposits/GDP, the ratio of bank deposits to

firm’s investment that is not financed using internal

GDP, where bank deposits are the demand, time, and

cash flows. We construct trade credits following Nilsen

savings deposits in money banks. 155.198.30.43] on 15 September

(2002) and Fisman and Love (2003) by using sup-

Our four survey-based measures come from the

pliers’ provision of funds. This is the ratio between

World Economic Forum Executive Opinion Survey g by [

accounts payable and total assets.6 Finally, we take

(Claessens and Laeven 2003), updated for 2006–2007. s.or

into account investment intensity, computed as capital

This captures access to loan market, a measure based m or

expenditures over total assets. All measures are cal-

on the question, How easy is it to obtain a bank loan nf i

culated using American Compustat firms from 1980

in your country with only a good business plan and

to 2000 at the three-digit SIC level (163 industries).

no collateral? Financial system sophistication is based on rom

the question, How sophisticated are the financial mar- d f 3.2.3.

Financial Development. As we empha-

kets in your country? Access to venture capital is based de

sized earlier, all of the Western European countries oa

on the question, In your country, how difficult is it nl

in our sample would be considered “developed”

for entrepreneurs with innovative but risky projects to ow

nations, in the broader sense of the word. Thus, some

find venture capital? Access to equity markets is based D

scholars may consider the differences we measure

on the question, How difficult is it to raise money by

as capturing different types of development, eschew-

issuing shares on the stock market in your country?

ing the ordinal connotations implied by terms such

as “level of development” (Carlin and Mayer 2003). 3.3. Descriptive Statistics

However, our use of the word “development” in this

Panel A of Table 1 provides summary statistics for firms

in our sample. On average, they have 392 employees

6 For a detailed discussion of the theory of trade credit provision, see Fisman and Love (2003).

7 We thank an anonymous reviewer for this suggestion.

Belenzon, Berkovitz, and Rios: Capital Markets and Firm Organization

Management Science 59(6), pp. 1326–1343, © 2013 INFORMS 1333 Table 1

Summary Statistics for Main Firm and Group Variables Distribution Variable No. of firms/groups Mean Std. dev. 10th 50th 90th Panel A: Firm level Sales ($, thousands) 1381770 1721808 214081520 111831 271569 1811881 d. Employess 1221477 392 31919 14 77 478 Assets ($, thousands) 1091129 1941489 311351302 41988 181593 1561511 Firm age 1331678 25 24 5 18 54 eserve Cash flow ($, thousands) 1041116 191584 9231785 −81 11120 121155 s r Panel B: Corporate group level ight No. of affiliates 261672 12 40 2 4 21 ll r Sales ($, millions) 261672 21612 281225 20 92 11320 y, a Assets ($, millions) 261672 61521 2001710 4 52 995 Cash flow ($, millions) 261672 193 31132 0 3 61 e onl

Industry concentration index 4HHI5 261672 0.68 0.24 0.38 0.66 1 l us

Notes. This table provides summary statistics on main firm and group variables in the estimation sample. In panel A, the unit of

observation is a firm, and in panel B, the unit of observation is a corporate group. Firms are included in the estimation sample if rsona

they have nonmissing sales and ownership information, and generate at least $10 million in annual sales. HHI, Herfindahl–Hirschman pe Index. or

(77 median) and generate $173 million in annual sales 3.4. Econometric Specification 44 . F

($28 million median). Panel B reports corporate group

We estimate a linear probability model for the like- t 08:

characteristics. Our affiliated firms belong to 26,672

lihood that a firm is affiliated with a group. The

unique groups with 12 affiliates on average. Groups econometric specification is

in our sample have abundant resources: the average 2016, a 4

group holds approximately $6.5 billion in assets; how- Pr Affiliate 1 i = 5 = 1Salesi + 2FinDevc × ExtDepj

ever, this seems to be driven by groups at the highest

+ 3Sales sharejc+ j + c + i1 (1)

end of the distribution, because the mean is $52 mil-

lion, and the 90th percentile is $1 billion.

where i denotes firm (the unit of observation), Salesi

Table 2 presents summary statistics separately for

is annual sales of firm i, FinDevc is financial develop-

group affiliated firms and stand-alone firms. Affiliates

ment for country c, ExtDepj is external dependence for

tend to be larger in terms of the number of employees, industry j, j and

c are complete sets of industry and

sales, assets, and cash flow, but quite similar in terms country dummies, and i is an independent and iden-

tically distributed error term. Following Rajan and

of age. In our econometric tests, we check whether

Zingales (1998), we control for the share of indus-

very large firms in our sample are driving the results.

try sales in each country using Sales sharejc, which is 155.198.30.43] on 15 September

Table 3 presents the variation in external depen-

the share of total sales of industry j (in which the

dence for a number of industries. Examples of high

focal firm operates) in country c. This measure is com- g by [

external dependence industries include chemicals,

puted using all firms in the complete sample where s.or

research and development, information technology,

we make no restrictions on sales volume. Share of m or

and drugs, whereas low external dependence indus-

industry sales controls for potential bias arising from nf

tries include concrete, metal and minerals, textiles, i

systematic country–industry correlation; for example, and transportation equipment.

a disproportionate representation of some industries rom d f de Table 2

Firm Characteristics: Affiliates vs. Stand-Alones oa nl Affiliates Stand-alones ow Affiliates − D Variable stand-alones No. of firms Mean Median Std. dev. No. of firms Mean Median Std. dev. Sales ($, thousands) 2061216∗∗ 70,058 2741916 371941 313281597 68,712 681700 211791 6301547 Employees 444∗∗ 63,281 607 103 51334 59,196 163 58 11124 Assets ($, thousands) 2521243∗∗ 61,959 3031519 251347 411341177 47,170 511276 131514 5061205 Firm age 0.14∗∗ 67,847 25.1 18 23.4 65,831 24.9 18 24.1 Cash flow ($, thousands) 271977∗∗ 58,697 311789 11539 112291523 45,419 31812 816 461255

Notes. This table reports mean comparison tests for affiliates and stand-alones. The unit of observation is a firm.

∗∗The difference in means between affiliates and stand-alones is significant at the 1% level.

Belenzon, Berkovitz, and Rios: Capital Markets and Firm Organization 1334

Management Science 59(6), pp. 1326–1343, © 2013 INFORMS Table 3

External Dependence for Selected Industries

firm were located in a country with the highest rela-

tive to the lowest level of financial development. No. of External funds Trade Investment Industry name firms dependence credit intensity 4. Estimation Results Chemicals (SIC 283) 11088 1001 0017 0035 Research and 802 0082 0021 0036 4.1. Baseline Estimation development (SIC 873)

Table 4 reports the baseline estimation results for the d. Information 41491 0060 0025 0050 technology (SIC 737)

interaction between our accounting measure of finan- Drugs (SIC 512) 21119 0031 0034 0033

cial development and industry external dependence, eserve Industry machinery 11395 0019 0018 0032

and Table 5 presents the estimation results using the s r (SIC 355)

survey measures. For each specification we calculate ight Heavy construction 11066 0009 0017 0033

and report the differential in affiliation probability (ãP). ll r (SIC 162) Rubber and plastic 21718

The pattern of results is consistent with our hypoth- −0007 0018 0024 y, a (SIC 30)

esis: the coefficient estimate on the interaction terms Transportation 11617 −0021 0021 0023

between industry external dependence and country e onl equipment (SIC 371) financial development ( ˆ l us Textille (SIC 22) 651 2) is negative and highly sig- −0022 0017 0022

nificant for the various combinations of dependence Commercial printing 11217 −0016 0023 0022 rsona (SIC 275)

and development. In unreported results we run the Metals and minerals 31346

entire battery of tests using a probit specification, −0031 0024 0017 pe (SIC 505) or

which consistently yields similar findings. We report Concrete (SIC 327) 11063 −0034 0011 0018

the linear probability model here because it allows a 44 . F

Notes. This table reports industry external dependence values for selectedmore straightforward interpretation.8

industries. External funds dependence is the difference between capital We show in Table 4 that the estimated effect t 08:

expenditures minus cash flow from operations over capital expenditures.of financial development on group affiliation varies

Trade credit is account receivables over total assets. Investment intensity is

for different development measures, ranging from

the ratio of capital expenditures to total assets. These industry measures are

−11.9% for stock market capitalization to −2.6% for 2016, a

computed at the three-digit SIC code level using Compustat firms for the period 1980–2000.

bank deposits. However, most measures have an

effect between −5% and −8%, compared to a sam-

ple mean of affiliation of 50.5. Table 5 reports similar,

in some countries. However, in unreported specifica-

though somewhat smaller, estimates for the survey-

tions we find that excluding this variable does not

based measures of financial development. We suspect yield different results.

that the survey measure may be noisier than the direct

Consistent with the hypothesis that the differ-

measures, resulting in some attenuation bias.

ence in share of affiliated firms between high and

An important concern is that industry specializa-

low external dependence industries would be larger

tion may be systematically related to country financial

in countries with lower financial development, we

development. For example, countries may specialize expect ˆ <

in certain industries (e.g., more labor intensive) as a 2

0. The interpretation of ˆ 2 can be eas- 155.198.30.43] on 15 September

ily explained in terms of difference in differences.

response to the level of financial development (e.g., if

Taking the first difference in probability of affiliation

wages are low). If this were the case we would expect g by [

with respect to external dependence, holding country

economic production in these countries to be heavily s.or m

financial development fixed, yields ãP

concentrated in specific industries. We check the sen- c = ˆ 2FinDevc × or

ãExtDep. Next, taking the difference in ãP

sitivity of our results to such potential industry spe- c between nf i

high and low country financial development yields

cialization by excluding industries with country sales ãP = ˆ ãFinDev × ã

share above 2.5%—the 75th percentile of the industry rom 2

ExtDep. Therefore, ˆ 2 measures d f

how much higher the likelihood of affiliation is at a

sales share distribution. The results are not sensitive de

high level of external dependence with respect to an

to dropping dominant industries. For instance, esti- oa

industry at a low dependence level when the firm

mating specification (1) of Table 4 with this restriction nl

yields as coefficient estimate of −0.023 (a standard

is located in a country with a high level of finan- ow

error of 0.004) on the interaction term between stock D

cial development rather than in a country with a low

market volume and external funds dependence, com-

level of development. In the tables that present the

pared with −0.018 without the restriction.

estimation results, we refer to ãP as the differential in

Our results are also robust to excluding very

affiliation probability. This is our main metric of quan-

large firms using various different size thresholds.

tification, and in our regressions it measures how

much higher the likelihood of affiliation is at the 90th

8 See Zelner (2009) for a detailed treatment of the potential issues

percentile level of external dependence with respect

associated with using interactions in probit specifications, as well

to an industry at the 10th percentile level, and if the

as a method for mitigating these issues.