Preview text:

lOMoAR cPSD| 58097008 4 CHARLES SCHWAB

This case was prepared by Charles W. L. Hill of the

School of Business, University of Washington, Seattle. C4-1 INTRODUCTION

of 204,000 trades a day in 2000 to 112,000 trades a

day in 2002. In 2003, Schwab’s revenues and net

income fell sharply, and the stock price tumbled

In 1971, Charles Schwab, who was 32 at the time, set up his

from a high of $51.70 a share in 1999 to a low of

own stock brokerage concern, First Commander. Later he

$6.30 in early 2003. During this period, Schwab

would change the name to Charles Schwab & Company, Inc.

expanded through acquisition into the asset

In 1975, when the Securities and Exchange Commission

management business for high-net-worth clients

abolished mandatory xed commissions on stock trades,

with the acquisition of U.S. Trust, a move that

Schwab moved rapidly into the discount brokerage business,

potentially put it in competition with independent

offering rates that were as much as 60% below those offered

investment advisors, many of whom used Schwab

by full commission brokers. Over the next 25 years, the

accounts for their clients. Schwab also entered the

company experienced strong growth, fueled by a customer-

investment banking business with the purchase of

centric focus, savvy investments in information technology, Soundview Technology Bank.

and a number of product innovations, including a bold move

In July 2004, founder and chairman Charles into online trading in 1996.

Schwab, who had relinquished the CEO role to David

By 2000, the company was widely regarded as one of the

Pottruck in 1998, red Pottruck and returned as CEO.

great success stories of the era. Revenues had grown to $7.1

Before stepping down in 2008, he refocused the

billion and net income to $803 million, up from $1.1 billion

company on its discount brokering roots, selling off

and $124 million, respectively, in 1993. Online trading had

Soundview and U.S. Trust. At the same time, he

grown to account for 84% of all stock trades made through

pushed for an expansion of Schwab’s retail banking

Schwab, up from zero in 1995. The company’s stock price had

business, allowing individual investors to hold

appreciated by more than that of Microsoft over the prior 10

investment accounts and traditional bank accounts

years. In 1999, the market value of Schwab eclipsed that of

at Schwab. Schwab remains chairman of the

Merrill Lynch, the country’s largest full- service broker, company.

despite Schwab’s revenues being over 60% lower.

In 2007–2009, a serious crisis gripped the

The 2000s proved to be a more dif cult environment for

nancial services industry. Some major nancial

the company. Between March 2000 and mid-2003, share

institutions went bankrupt, including Lehman

prices in the United States tumbled, with the technology-

Brothers and Washington Mutual. The widely heavy NASDAQ index losing

watched Dow Industrial Average Index plunged from C-50

over 14,000 in October 2007 to 6,600 in March 2007.

80% of its value from peak to trough. The volume of

Widespread nancial collapse was only averted when

online trading at Schwab slumped from an average

the government stepped in to support the sector lOMoAR cPSD| 58097008 Case 4 Charles Schwab C-51

with a $700-billion loan to troubled companies. C4-2a Industry Background

Almost alone amongst major nancial service rms,

Schwab was able to navigate through the crisis with

In 2016, there were 3,816 broker-dealers registered

relative ease, remaining solidly pro table and having

in the United States, down from 9,515 in 1987. The

no need to place a call on government funds. By

industry is concentrated, with some 200 rms that

2010–2017, the company was once again on a

are members of the New York Stock Exchange

growth path, fueled by expanded offerings including

(NYSE) accounting for 87% of the assets of all

the establishment of a marketplace for exchange

broker-dealers, and 80% of the capital. The 10

traded funds (EFTs). Schwab’s asset base expanded

largest NYSE rms accounted for around 57% of the

at around 6% per annum during this period, and by

gross revenue in the industry in 2016, up from 48%

early 2018 it was managing almost $3.4 trillion in

in 1998. The consolidation of the industry has been

client assets. In 2017, Schwab reported record net

driven in part by deregulation, which is discussed in

income of $2.18 billion on record revenues of $8.62 more detail below.

billion. The major strategic question going forward

Broker-dealers make money in a number of ways. They

was how to continue to grow pro tably in what

earn commissions (or fees) for executing a customer’s order

remained a price-competitive environment for

to buy or sell a given security (stocks, bonds, option brokerage rms.

contracts, etc.). They earn trading income, which is the

realized and unrealized gains and losses on securities held

and traded by the brokerage rm. They earn money from

underwriting fees, which are the fees charged to corporate C4-2 THE SECURITIES

and government clients for managing an issue of stocks or

bonds on their behalf. They earn asset management fees, BROKERAGE

which represent income from the sale of mutual fund

securities, from account supervision fees, or from INDUSTRY1

investment advisory or administrative service fees. They earn

margin interest, which is the interest that customers pay to

the brokerage when they borrow against the value of their

securities to nance purchases. They earn other securities

A security is a nancial instrument such as a stock,

related revenue comes from private placement fees (i.e., fees

bond, commodity contract, stock option contract,

from private equity deals) subscription fees for research

or foreign exchange contract. The securities

services, charges for advisory work on proposed mergers and

brokerage industry is concerned with the issuance

acquisitions, fees for options done away from an exchange

and trading of nancial securities, as well as a

and so on. Finally, many brokerages earn nonsecurities

number of related activities. A broker’s clients may

revenue from other nancial services, such as credit card

be individuals, corporations, or government bodies.

operations or mortgage services.

Brokers undertake one or more of the following

functions: assist corporations to raise capital by C4-2b Industry Groups

offering stocks and bonds; help governments raise

capital through bond issues; advise businesses on

Historically, brokerage rms have been segmented into ve

their foreign currency needs; assist corporations

groups. First, there are national, full-line rms, which are the

with mergers and acquisitions; help individuals plan

largest full-service brokers with extensive branch systems.

their nancial future and trade nancial securities;

They provide virtually every nancial service and product that

and provide detailed investment research to

a brokerage can offer to both households (retail customers)

individuals and institutions so that they can make

and institutions (corporations, governments, and other

more informed investment decisions.

nonpro t organizations such as universities). Examples of

such rms include Merrill Lynch and Morgan Stanley. Most of

these rms are headquartered in New York. For retail

customers, national, full-line rms provide access to a

personal nancial consultant, traditional brokerage services, lOMoAR cPSD| 58097008 C-52 Case 4 Charles Schwab

securities research reports, asset management services,

corporations and governments tend to issue more securities,

nancial planning advice, and a range of other services such

which increases underwriting income. Also, low interest

as margin loans, mortgage loans, and credit cards. For

rates tend to stimulate economic growth, which leads to

institutional clients, these rms will also arrange and

higher corporate pro ts, and thus higher stock values. When

underwrite the issuance of nancial securities, manage their

interest rates decline, individuals typically move some of

nancial assets, provide advice on mergers and acquisitions,

their money out of low-interest-bearing cash accounts or

and provide more detailed research reports than those

low-yielding bonds, and into stocks, in an attempt to earn

normally provided to retail customers, often for a fee.

higher returns. This drives up trading volume and hence

Large investment banks are a second group. This group

commissions. Low interest rates, by reducing the cost of

includes Goldman Sachs. These banks have a limited branch

borrowing, can also increase merger and acquisition activity.

network and focus primarily on institutional clients, although

Moreover, in a rising stock market, corporations often use

they also may have a retail business focused on high-net-

their stock as currency with which to make acquisitions of

worth individuals (typically individuals with more than $1

other companies. This drives up drives up merger and

million to invest). In 2008, Lehman Brothers went bankrupt,

acquisition activity, and the fees brokerages earn from such

a casualty of bad bets on mortgage-backed securities, while activity.

the large bank, J.P. Morgan, acquired Bear Stearns, leaving

The 1990s were characterized by one of the

Goldman Sachs as the sole stand-alone representative in this

strongest stock market advances in history. This class.

boom was driven by a favorable economic

A third group are regional brokers, which are fullservice

environment, including falling interest rates, new

brokerage operations with a branch network in certain

information technology, productivity gains in

regions of the country. Regional brokers typically focus on

American industry, and steady economic expansion,

retail customers, although some have an institutional

all of which translated into growing corporate pro ts presence. and rising stock prices.

Fourth, there are a number of New York City-based

Also feeding the stock market’s advance during

brokers who conduct a broad array of nancial services,

the 1990s were favorable demographic trends.

including brokerage, investment banking, traditional money

During the 1990s, American Baby Boomers started management, and so on.

to save for retirement, pumping signi cant assets

Finally, there are the discounters, who are primarily

into equity funds. The percentage of household

involved in the discount brokerage business and focus on

liquid assets held in equities and mutual funds

executing orders to buy and sell stocks for retail customers.

increased from 33.8% in 1990 to 66.9% in 1999,

Commissions are their main source of business revenue.

while the number of households that owned

They charge lower commissions than full-service brokers, but

equities increased from 32.5 to 50.1% over the same

do not offer the same infrastructure, such as personal nancial period.

consultants and detailed research reports. The discounters

Adding fuel to the re, by the late 1990s, stock

provide trading and execution services at deep discounts

market mania had taken hold. Stock prices rose to

online via the Web. Many discounters, such as Ameritrade

speculative highs rarely seen before as “irrationally

and E*Trade, do not maintain branch of ces. Schwab, which

exuberant” retail investors, who seemed to believe

was one of the rst discounters and remains the largest, has a

that stock prices could only go up, made increasingly

network of brick-andmortar of ces, as well as a leading online

risky and speculative “investments” in richly valued presence.

equities.2 The market peaked in late 2000 as the

extent of overvaluation became apparent. It fell

signi cantly over the next 2 years as the economy C4-2c Earnings Trends

struggled with a recession. This was followed by a

Industry revenues and earnings are volatile, being driven by

recovery in both the economy and the stock market,

variations in the volume of trading activity (and

with the S&P 500 returning to its old highs by

commissions), underwriting, and merger and acquisition

October 2007. However, as the global credit crunch

activity. All of these tend to be highly correlated with changes

unfolded in 2008, the market crashed, falling

in the value of interest rates and the stock market. In general,

precipitously in the second half of 2008 to return to

when interest rates fall, the cost of borrowing declines, so

levels not seen since the mid-1990s. The market has lOMoAR cPSD| 58097008 Case 4 Charles Schwab C-53

since recovered, and by 2016 almost 60% of the C4-2d Deregulation

nancial assets of U.S. households was once again

held in equities and mutual funds.

The industry had been progressively deregulated

since May 1, 1975, when a xed commission

The long stock market boom of the 1990s drove

structure on securities trades was dismantled. This

an expansion of industry revenues, which for

development allowed for the emergence of

brokerages that were members of the NYSE, grew

discount brokers such as Charles Schwab. Until the

from $54 billion in 1990 to $245 billion in 2000. As

the bubble burst and the stock market slumped in

mid-1980s, however, the nancial services industry

was highly segmented due to a 1933 Act of

2001 and 2002, brokerage revenues plummeted to

Congress known as the Glass-Steagall Act. This Act,

$144 billion in 2003, forcing brokerages to cut

which was passed in the wake of widespread bank

expenses. By 2007, revenues had recovered again

failures following the stock market crash of 1929,

and were a record $352 billion. In 2008, the nancial

erected regulatory barriers between different

crisis hit, and industry revenues contracted $178

sectors of the nancial services industry, such as

billion. In that year the industry lost $42.6 billion.

commercial banking, insurance, saving and loans,

By 2016, with the stock market booming again,

and investment services (including brokerages).

revenues were back up to $276 billion and the

Most signi cantly, Section 20 of the Act erected a

industry booked $27 billion in net income.

wall between commercial banking and investment

The expense structure of the brokerage industry

services, barring commercial banks from investing

is dominated by two big items: interest expenses

in shares of stocks, limiting them to buying and

and compensation expenses. Together these

selling securities as an agent, prohibiting them from

account for about three-quarters of industry

underwriting and dealing in securities, and from

expenses. Interest expenses re ect the interest rate

being af liated with any organization that did so.

paid on cash deposits at brokerages; they rise or fall

In 1987, Section 20 was relaxed to allow banks to earn up

with the size of deposits and interest rates. As such,

to 5% of their revenue from securities underwriting. The limit

they are generally not regarded as a controllable

was raised to 10% in 1989 and 25% in 1996. In 1999, the

expense (because the interest rate is ultimately set

Gramm-Leach-Bliley (GLB) Act was passed nalizing the repeal

by the U.S. Federal Reserve and market forces).

of the Glass-Steagall Act. By removing the walls between

Compensation expenses re ect both employee

commercial banks, broker-dealers, and insurance companies,

headcount and bonuses. For some brokerage rms,

many predicted that the GLB Act would lead to massive

particularly those dealing with institutional clients,

industry consolidation, with commercial banks purchasing

bonuses can be enormous, with multimilliondollar

brokers and insurance companies. The rational was that such

bonuses being awarded to productive employees.

diversi ed nancial services rms would become one stop

Compensation expenses and employee headcount

nancial supermarkets, cross-selling products to their

tend to grow during bull markets, only to be rapidly

expanded client base. For example, a nancial supermarket

curtailed once a bear market sets in.

might sell insurance to brokerage customers, or brokerage

The pro tability of the industry is volatile and

services to commercial bank customers. The leader in this

depends critically upon the overall level of stock

process was Citigroup, which was formed in 1998 by a

market activity. Pro ts were high during the boom

merger between Citicorp, a commercial bank, and Traveler’s,

years of the 1990s. The bursting of the stock market

an insurance company. Since Traveler’s had already acquired

bubble in 2000–2001 bought a period of low pro

Salomon Smith Barney, a major brokerage rm, the new

tability, and although pro tability improved after

Citigroup seemed to signal a new wave of consolidation in

2002, it did not return to the levels of the 1990s.

the industry. The passage of the GLB Act allowed Citigroup to

The nancial crisis and stock market crash of 2007– start cross-selling products.

2009 resulted in large losses for the industry, but

However, industry reports suggested that crossselling

pro ts have since improved since.

was easier in theory than in practice, in part because

customers were not ready for the development.3 In an

apparent admission that this was the case, in 2002, Citigroup

announced that it would spin off Traveler’s Insurance as a lOMoAR cPSD| 58097008 C-54 Case 4 Charles Schwab

separate company. At the same time, the fact remained that

San Francisco, a world away from Wall Street, First

the GLB Act had made it easier for commercial banks to get

Commander was a conventional brokerage that charged

into the brokerage business, and there were several

clients xed commissions for securities trades. The name was

acquisitions to this effect. Most notably, in 2008, Bank of

changed to Charles Schwab the following year.

America purchased Merrill Lynch, and J.P. Morgan Chase

In 1974, at the suggestion of a friend, Schwab

purchased Bear Stearns. Both of the acquired enterprises

joined a pilot test of discount brokerage being

were suffering from serious nancial troubles due to their

conducted by the Securities and Exchange

exposure to mortgage-backed securities.

Commission. The discount brokerage idea instantly

appealed to Schwab. He personally hated selling,

particularly cold calling. the constant calling on

actual or prospective customers to encourage them C4-3 THE GROWTH OF

to make a stock trade. Moreover, Schwab was

deeply disturbed by the con ict of interest that SCHWAB

seemed everywhere in the brokerage world, with

stock brokers encouraging customers to make

The son of an assistant district attorney in California, Charles

questionable trades in order to boost commissions.

Schwab started to exhibit an entrepreneurial streak from an

Schwab also questioned the worth of the

early age. As a boy, he picked walnuts and bagged them for

investment advice brokers gave clients, feeling that

$5 per 100 pound sack. He raised chicken in his backyard,

it re ected the inherent con ict of interest in the

sold the eggs door to door, killed and plucked the fryers for

brokerage business and did not empower

market, and peddled the manure as fertilizer. Schwab called customers.

it “my rst fully integrated businesses.”4

Schwab used the pilot test to ne-tune his model

As a child, Schwab had to struggle with a severe case of

for a discount brokerage. When the SEC abolished

dyslexia, a disorder that makes it dif cult to process written

mandatory xed commission the following year,

information. To keep up with his classes, he had to resort to

Schwab quickly moved into the business. His basic

Cliffs Notes and Classics Illustrated comic books. Schwab

thrust was to empower investors by giving them the

believes, however, that his dyslexia was ultimately a

information and tools required to make their own

motivator, spurring him on to overcome the disability and

decisions about securities investments, while

excel. Schwab gained admission to Stanford, where he

keeping Schwab’s costs low so that this service could

received a degree in economics, followed by an MBA from

be offered at a deep discount to the commissions Stanford Business School.

charged by full-service brokers. Driving down costs

Fresh out of Stanford in the 1960s, Schwab embarked

meant that, unlike full-service brokers, Schwab did

upon his rst entrepreneurial effort, an investment advisory

not employee nancial analysts and researchers who

newsletter, which grew to include a mutual fund with $20

developed proprietary investment research for the

million under management. However, after the stock market

rm’s clients. Instead, Schwab focused on providing

fell sharply in 1969, the State of Texas ordered Schwab to

clients with third-party investment research. These

stop accepting investments through the mail from its citizens

“reports” evolved to include a company’s nancial

because the fund was not registered to do business in the

history, a smatter of comments from securities

state. Schwab went to court and lost. Ultimately, he had to

analysts at other brokerage rms that had appeared

close his business, leaving him with $100,000 in debt and a

in the news, and a tabulation of buy and sell

marriage that had collapsed under the emotional strain.

recommendations from full-commission brokerage

houses. The reports were sold to Schwab’s

customers at cost (in 1992, this was $9.50 for each C4-3a The Early Days

report plus $4.75 for each additional report).5

Schwab soon bounced back. Capitalized by $100,000 that he

A founding principle of the company was a desire

borrowed from his Uncle Bill, who had a successful industrial

to be the most useful and ethical provider of nancial

company of his own called Commander Corp, in 1971

services. Underpinning this move was Schwab’s

Schwab started a new company, First Commander. Based in

belief in the inherent con ict of interest between

brokers at full-service rms and their clients. The lOMoAR cPSD| 58097008 Case 4 Charles Schwab C-55

desire to avoid a con ict of interest caused Schwab

Schwab began to realize that the branches

to rethink the traditional commission based pay

served a powerful psychological purpose—they

structure. As an alternative to commission-based

gave customers a sense of security that Schwab was

pay, Schwab paid all its employees, including its

a real company. Customers were reassured by

brokers, a salary plus a bonus that was tied to

seeing a branch with people in it. In practice, many

attracting and satisfying customers and achieving

clients would rarely visit a branch. They would open

productivity and ef ciency targets. Commissions

an account, and execute trades over the telephone

were taken out of the compensation equation.

(or later, via the Internet). But the branch helped

The chief promoter of Schwab’s approach to

them to make that rst commitment. Far from being

business, and marker of the Schwab brand, was

a drain, Schwab realized that the branches were a

none other than Charles Schwab himself. In 1977,

marketing tool. People wanted to be “perceptually

the rm started to use pictures of Charles Schwab in

close to their money,” and the branches satis ed

its advertisements, a practice it still follows today.

that deep psychological need. From 1 branch in

The customer-centric focus of the company led

1975, Schwab grew to have 52 branches in 1982,

Schwab to think of ways to make the company

175 by 1992, and 430 in 2002. The next few years

accessible to customers. In 1975, Schwab became

bought retrenchment, however, and Schwab’s

the rst discount broker to open a branch of ce and

branches fell to around 300 by 2008.

to offer access 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

By the mid-1980s, customers could access Schwab in

Interestingly, however, the decision to open a

person at a branch during of ce hours, by phone day or night,

branch was not something that Charles Schwab

by a telephone voice recognition quote and trading service

initially embraced. He wanted to keep costs low and

known as TeleBroker, and by an innovative proprietary online

thought it would be better if everything could be

network. To encourage customers to use TeleBroker or its

managed by telephone. However, Schwab was

online trading network, Schwab reduced commissions on

forced to ask his Uncle Bill for more capital to get

transactions executed this way by 10%, but it saved much

his nascent discount brokerage off the ground.

more than that because doing business via computer was

Uncle Bill agreed to invest $300,000 in the

cheaper. By 1995, TeleBroker was handling 80 million calls

company, but on one condition: He insisted that

and 10 million trades a year, 75% of Schwab’s annual volume.

Schwab open a branch of ce in Sacramento and

To service this system, in the mid-1980s. Schwab invested

employ Uncle Bill’s son-in-law as manager!6

$20 million in four regional customer call centers, routing all

Reluctantly, Schwab agreed to Uncle Bill’s demand

calls to them rather than branches. Today, these call centers

for a show of nepotism, hoping that the branch have 4,000 employees.

would not be too much of a drain on the company’s

Schwab was the rst to establish a PC-based online trading business.

system in 1986, with the introduction of its Equalizer service.

What happened next was a surprise; there was

The system had 15,000 customers in 1987, and 30,000 by the

an immediate and dramatic increase in activity at

end of 1988. The online system, which required a PC with a

Schwab, most of it from Sacramento. Customer

modem, allowed investors to check current stock prices,

inquiries, the number of trades per day, and the

place orders, and check their portfolios. In addition, an “of

number of new accounts, all spiked upwards. Yet

ine” program for PCs enabled investors to do fundamental

there was also a puzzle here, for the increase was

and technical analysis on securities. To encourage customers

not linked to an increase in foot traf c in the branch.

to start using the system, there was no additional charge for

Intrigued, Schwab opened several more branches

using the online system after a $99 sign-up fee. In contrast,

over the next year, and each time noticed the same

other discount brokers with PC-based online systems, such

pattern. For example, when Schwab opened its rst

as Quick and Riley’s (which had a service known as “Quick

branch in Denver, it had 300 customers. It added

Way”), or Fidelity’s (whose service was called “Fidelity

another 1,700 new accounts in the months

Express”) charged users between 10 cents and 44 cents a

following the opening of the branch, and yet there

minute for online access depending on the time of day.7

was a big spike up in foot traf c at the Denver

Schwab’s pioneering move into online trading was in branch.

many ways just an evolution of the company’s early

utilization of technology. In 1979, Schwab spent $2 million, lOMoAR cPSD| 58097008 C-56 Case 4 Charles Schwab

an amount equivalent to the company’s entire net worth at

money in an account where it accumulates tax free

the time, to purchase a used IBM System 360 computer, plus

until withdrawal at retirement. The legislation

software, that was left over from CBS’s 1976 election

establishing IRAs had been passed by Congress in

coverage. At the time, brokerages generated and had to

1982. At the time, estimates suggested that IRA

process massive amounts of paper to execute buy and sell

accounts could attract as much as $50 billion in

orders. The computer gave Schwab a capability that no other

assets within 10 years. In actual fact, the gure turned

brokerage had at the time: take a buy or sell order that came out to be $725 billion.

in over the phone, edit it on a computer screen, and then

Initially, Schwab followed industry practice and

submit the order for processing without generating paper.

collected a small fee for each IRA. By 1986, the fees

Not only did the software provide for instant execution of

amounted to $9 million a year, not a trivial amount

orders, it also offered what were then sophisticated quality

for Schwab in those days. After looking at the issue,

controls, checking a customer’s account to see if funds were

Charles Schwab himself made the call to scrap the

available before executing a transaction. As a result of this

fee, commenting that “It’s a nuisance, and we’ll get

system, Schwab’s costs plummeted as it removed paper from

it back.”9 He was right; Schwab’s No-Annual Fee IRA

the system. Moreover, the cancel and rebill rate—a measure

immediately exceeded the company’s most

of the accuracy of trade executions—dropped from an optimistic projections.

average of 4 to 0.1%.8 Schwab soon found it could handle

Despite technological and product innovations,

twice the transaction volume of other brokers, at less cost,

by 1983, Schwab was strapped for capital to fund

and with much greater accuracy. With 2 years, every other

expansion. To raise funds, he sold the company to

broker in the nation had developed similar systems, but

Bank of America for $55 million in stock and a seat

Schwab’s early investment had given it an edge and

on the bank’s board of directors. The marriage did

underpinned the company’s belief in the value of technology

not last long. By 1987, the bank was reeling under

to reduce costs and empower customers.

loan losses, and the entrepreneurially minded

By 1982, the technology at Schwab was well ahead of

Schwab was frustrated by banking regulations that

that used by most full-service brokers. This commitment to

inhibited his desire to introduce new products.

technology allowed Schwab to offer a product that was

Using a mix of loans, his own money, and

similar in conception to Merrill Lynch’s revolutionary cash

contributions from other managers, friends, and

management account (CMA), which was introduced in 1980.

family, Schwab led a management buyout of the

The CMA account automatically sweeps idle cash into money

company for $324 million in cash and securities.

market funds and allows customers to draw on their money

On September 22, 1987, Schwab went public

by check or credit card. Schwab’s system, known as the

with an IPO that raised some $440 million, enabling

Schwab One Account, was introduced in 1982. It went

the company to pay down debt and leaving it with

beyond Merrill’s in that it allowed brokers to execute orders

capital to fund an aggressive expansion. At the time,

instantly through Schwab’s computer link to the exchange

Schwab had 1.6 million customers, revenues of $308 oor.

million, and a pre-tax pro t margin of 21%. Schwab

In 1984, Schwab moved into the mutual fund business,

announced plans to increase its branch network by

not by offering its own mutual funds, but by launching a

30% to around 120 of ces over the next year. Then,

mutual fund marketplace, which allowed customers to invest

on Monday, October 19, 1987, the U.S. stock market

in some 140 no-load mutual funds (a “no-load” fund has no

crashed, dropping over 22%, the greatest 1-day

sales commission). By 1990, the number of funds in the decline in history.

market place was 400 and the total assets involved exceeded

$2 billion. For the mutual fund companies, the marketplace

offered distribution to Schwab’s growing customer base. C4-3b October 1987–1995

For its part, Schwab kept a small portion of the

After a strong run up over the year, on Friday, October 16, the

revenue stream that owed to the fund companies

stock market dropped 4.6%. During the weekend, nervous from Schwab clients.

investors jammed the call centers and branch of ces, not just

In 1986, Schwab made a gutsy move to eliminate

at Schwab, but at many other brokerages, as they tried to

the fees for managing individual retirement

place sell orders. At Schwab, 99% of the orders taken over

accounts (IRAs). IRAs allow customers to deposit

the weekend for Monday morning were sell orders. As the lOMoAR cPSD| 58097008 Case 4 Charles Schwab C-57

market opened on Monday morning, it went into free fall. At

to give advice—which was the business of the advisors.

Schwab, the computers were overwhelmed by 8 a.m. The

Schwab immediately saw an opportunity here. Financial

toll-free number to the call centers was also totally

advisors, he reasoned, represented a powerful way to

overwhelmed. All customers got when they called were busy

acquire customers. In 1989, the company rolled out a

signals. When the dust had settled, Schwab announced that

program to aggressively court this group. Schwab hired a

it had lost $22 million in the fourth quarter of 1987, $15

marketing team to focus explicitly on nancial planners, set

million of which came from a single customer who had been

apart a dedicated trading desk for them, and gave discounts unable to meet margin calls.

of as much as 15% on commissions to nancial planners with

The loss, which amounted to 13% of the

signi cant assets under management at Schwab accounts.

company’s capital, effectively wiped out the

Schwab also established its Financial Advisors Service, which

company’s pro t for the year. Moreover, the inability

provided clients with a list of nancial planners who were

of customers to execute trades during the crash

willing to work solely for a fee, and who had no incentive to

damaged Schwab’s hard-earned reputation for

push the products of a particular client. At the same time, the

customer service. Schwab responded by posting a

company stated that it wasn’t endorsing the planners’

two-page ad in The Wall Street Journal on October

advice, which would run contrary to the company’s

28, 1987. On one page there was a message from

commitment to offer no advice. Within a year, nancial

Charles Schwab thanking customers for their

advisors had some $3 billion of client’s assets under

patience, on the other an ad thanking employees management at Schwab. for their dedication.

Schwab also continued to expand its branch network

In the aftermath of the October 1987 crash,

during this period, at a time while many brokerages, still

trading volume fell by 15% as customers, spooked

stunned by the October 1987 debacle, were retrenching.

by the volatility of the market, sat on cash balances.

Between 1987 and 1989, Schwab’s branch network increased

The slowdown prompted Schwab to cut back on its

by just 5, from 106 to 111, but in 1990 it opened an

expansion plans. Ironically, however, Schwab added

additional 29 branches, and another 28 in 1991.

a signi cant number of new accounts in the

By 1990, Schwab’s positioning in the industry had

aftermath of the crash as people looked for cheaper

become clear. Although a discounter, Schwab was by no ways to invest.10

means the lowest price discount broker in the country. Its

Beset by week trading volume through the next

average commission structure was similar to that of Fidelity,

18 months, and reluctant to lay off employees,

the Boston-based mutual fund company that had moved into

Schwab sought ways to boost activity. One strategy

the discount brokerage business, and Quick & Reilly, a major

started out as a compliance issue within Schwab. A

national competitor (see Exhibit 1). While signi cantly below

compliance of cer in the company noticed a

that of full-service brokers, the fee structure was also above

disturbing pattern. A number of people had given

that of deep-discount brokers. Schwab differentiated itself

other people limited power of attorney over their

from the deep-discount brokers, however, by its branch

accounts. This in itself was not unusual—for

network, technology, and the information (not advice) that it

example, the middle-aged children of an elderly gave to investors.

individual might have power of attorney over an

account—but the Schwab of cer noticed that some

individuals had power of attorney over dozens, if not hundreds, of accounts.

Further investigation turned up the reason.

Schwab had been serving an entirely unknown set

of customers, independent nancial advisors who

were managing the nancial assets of their clients

using Schwab accounts. In early 1989, some 500

nancial advisors managed assets totaling $1.5

billion at Schwab, about 8% of all assets at Schwab.

The advisors were attracted to Schwab for a number of

reasons, including cost and the company’s commitment not lOMoAR cPSD| 58097008 C-58 Case 4 Charles Schwab

In 1992, Schwab rolled out another strategy aimed at

customers’ names. Many fund managers did not like this,

acquiring assets—OneSource, the rst mutual fund

because it limited their ability to build a direct relationship

“supermarket.” OneSource was created to take advantage of

with customers, but they had little choice if they wanted

America’s growing appetite for mutual funds. By the early

access to Schwab’s customer base.

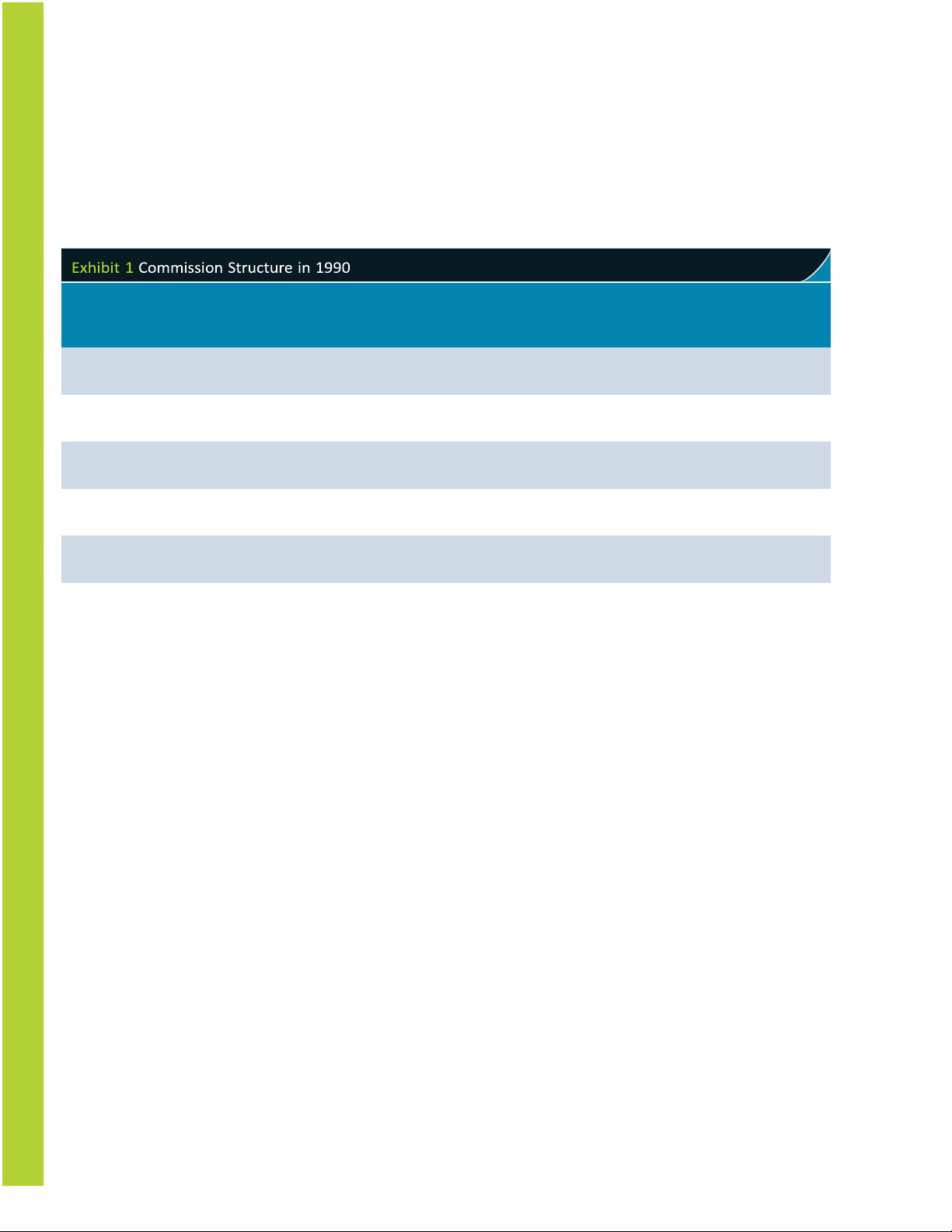

Average Commission Price on 20 Trades Averaging $8,975 Each Type of Broker Deep-Discount Brokers $ 54 Average Discounters $ 73 Banks $ 88

Schwab, Fidelity, and Quick & Reilly $ 92 Full-Service Brokers $ 206

Source: E. C. Gottschalk, “Schwab Forges Ahead as Other Brokers Hesitate,” The Wall Street Journal, May 11, 1990, p. C1.

1990s, there were more mutual funds than individual

OneSource quickly propelled Schwab to the

equities. On some days, Fidelity, the largest mutual fund

number three position in direct mutual fund

company, accounted for 10% of the trading volume on the

distribution, behind the fund companies Fidelity and

New York Stock Exchange. As American Baby Boomers aged,

Vanguard. By 1997, Schwab customers could choose

they seemed to have an insatiable appetite for mutual funds.

from nearly 1,400 funds offered by 200 different

But the process of buying and selling mutual funds had never

fund families, and Schwab customers had nearly $56

been easy. As Charles Schwab explained in 1996:

billion in assets invested through One Source.

“In the days before the supermarkets, to buy a mutual

fund you had to write or call the fund distributor. On Day Six,

you’d get a prospectus. On Day Seven or Eight you call up and C4-3c 1996–2000: eSchwab

they say you’ve got to put your money in. If you’re lucky, by

In 1994, as access to the Web began to diffuse

Day Ten you’ve bought it . . . It was even more cumbersome

rapidly throughout America, a 2-year-old start-up

when you redeemed. You had to send a notarized

run by Bill Porter, a physicist and inventor, launched redemption form.”11

its rst dedicated website for online trading. The

OneSource took the hassle out of owning funds. With a

company was E*Trade. E*Trade announced a at

single visit to a branch of ce, a telephone call, or a PC-based

$14.95 commission on stock trades, signi cantly

computer transaction, a Schwab client could buy and sell

below Schwab’s average commission, at the time

mutual funds. Schwab imposed no fee at all on investors for

$65. It was clear from the outset that E*Trade and

the service. Rather, in return for shelf space in Schwab’s

other online brokers such as Ameritrade offered a

distribution channel and access to the more than 2 million

direct threat to Schwab. Not only were their

accounts at Schwab, Schwab charged the fund companies a

commission rates considerably below those of

fee amounting to 0.35% of the assets under management. By

Schwab, but the ease, speed, and exibility of trading

inserting itself between the fund managers and customers,

stocks over the Web suddenly made Schwab’s

Schwab changed the balance of power in the mutual fund

proprietary online trading software, Street Smart,

industry. When Schwab sold a fund through One Source, it

seem limited. (Street Smart was the Windowsbased

passed along the assets to the fund managers, but not the

successor to Schwab’s DOSbased Equalizer lOMoAR cPSD| 58097008 Case 4 Charles Schwab C-59

program). To compound matters, talented people

personnel in Schwab to slow down or even derail

left Schwab for E*Trade and its brethren, which they

the web-based initiative. As Pottruck later put it:

saw as the wave of the future.

“The new enterprise was going to use a

At the time, deep within Schwab, William

different model for making money than our

Pearson, a young software specialist who had

traditional business, and we didn’t want the

worked on the development of Street Smart, quickly

comparisons to form the basis for a measurement

saw the transformational power of the Web and

of success or failure. For example, eSchwab’s per

believed that it would make proprietary systems like

trade revenue would be less than half that of the

Street Smart obsolete. Pearson believed that

mainstream of the company, and that could be seen

Schwab needed to develop its own web-based

as a drain on resources rather than a response to

software, and quickly. Try as he might, though,

what customer would be using in the future.”12

Pearson could not get the attention of his supervisor.

Pottruck and Schwab understood that unless eSchwab

He tried a number of other executives, but found

was placed in its own organization, isolated and protected

support hard to come by. Eventually, he approached

from the established business, it might never get off the

Anne Hennegar, a former Schwab manager that he

ground. They also knew that if they did not cannibalize their

knew who now worked as a consultant to the

own business with eSchwab, someone would do it for them.

company. Hennegar suggested that Pearson meet

Thus, they set up a separate organization to develop

with Tom Seip, an executive vice president at

eSchwab, headed by Beth Sawi, a highly regarded marketing

Schwab who known for his ability to think outside of

manager at Schwab who had very good relations with other

the box. Hennegar approached Seip on Pearson’s

managers in the company. Sawi set up the development

behalf, and Seip responded positively, asking her to

center in a unit physically separated from other Schwab

set up a meeting. Hennegar and Pearson turned up facilities.

expecting to meet just Seip, but to their surprise in

eSchwab was launched in May 1996, but without the

walked Charles Schwab, his COO, David Pottruck,

normal publicity that accompanied most new products at

and the vice presidents in charge of strategic

Schwab. Schwab abandoned its sliding scale commission for

planning and the electronic brokerage arena.

a at rate commission of $39 (which was quickly dropped to

As the group watched Pearson’s demo of how a

$29.95) for any stock trade up to 1,000 shares. Within 2

web-based system would look and work, they

weeks 25,000 people had opened eSchwab accounts. By the

became increasingly excited. It was clear to those in

end of 1997, the gure would soar to 1.2 million, bringing in

the room that a web-based system based on real

assets of about $81 billion, 10 times the assets of E*Trade.

time information, personalization, customization,

Schwab initially kept the two businesses segmented. and interactivity all advanced Schwab’s

Schwab’s traditional customers were still paying an average

commitment to empowering customers. By the end

of $65 per trade while eSchwab customers were paying

of the meeting, Pearson had received a green light

$29.95. While Schwab’s traditional customers could make to start work on the project.

toll-free calls to Schwab brokers, eSchwab clients could not.

It soon transpired that several other groups within

Moreover, Schwab’s regular customers couldn’t access

Schwab had been working on projects similar to

eSchwab at all. The segmentation soon gave rise to

Pearson’s. These were all pulled together under the

problems. Schwab’s branch employees were placed in the

control of Dawn Lepore, Schwab’s chief information

uncomfortable position of telling customers that they

of cer, who headed up the effort to develop the

couldn’t set up eSchwab accounts. Some eSchwab customers

webbased service that would ultimately become

started to set up traditional Schwab accounts with small

eSchwab. Meanwhile, signi cant strategic issues

sums of money so that they could access Schwab’s brokers

were now beginning to preoccupy Schwab and

and information services, while continuing to trade via

Pottruck. They realized that Schwab’s established

eSchwab. Clearly the segmentation was not sustainable.

brokerage and a webbased brokerage business

Schwab analyzed the situation. The company’s leaders

were based on very different revenue and cost

realized that the cleanest way to deal with the problem

models. The web-based business would probably

would be to give every Schwab customer online access,

cannibalize business from Schwab’s established

adopt a commission of $29.95 on trading across all channels,

brokerage operations, and that might lead

and maintain existing levels of customer service at the lOMoAR cPSD| 58097008 C-60 Case 4 Charles Schwab

branch level, and on the phone. However, internal estimates

Schwab implemented the change of strategy on January

suggested that the cut in commission rates would reduce

15, 1998. Revenues dropped 3% in the rst quarter as the

revenues by $125 million, which would hit Schwab’s stock.

average commission declined from $63 to $57. Earnings also

The problem was compounded by two factors. First,

came in short of expectations by some $6 million. The

employees owned 40% of Schwab stock, so they would be

company’s stock had lost 20% of its value by August 1998.

hurt by any fall in stock price; second, employees were

However, over much of 1998 new money poured in. Total

worried that going to the Web would result in a decline in

accounts surged, with Schwab gaining a million new

business at the branch level, and hence a loss of jobs there.

customers in 1998—a 20% increase—while assets grew by

An internal debate ranged within the company for much

32%. As the year progressed, trading volume grew, doubling

of 1997, when Schwab’s revenues surged 24% to $2.3 billion.

by year end. By the third quarter, Schwab’s revenues and

The online trading business grew by more than 90% during

earnings were surging past analysts’ expectations. The

the year, with online trades accounting for 37% of all Schwab

company ultimately achieved record revenues and earnings

trades during 1997, and the trend was up throughout the

in 1998. Net income ended up 29% over the prior year, year.

despite falling commission rates, aided by surging trading

Looking at these gures, Pottruck, the COO, knew that

volume and the lower cost of executing trades over the Web.

Schwab had to bite the bullet and give all Schwab customers

By year-end, 61% of all trades at Schwab were made over the

access to eSchwab (Pottruck was now running the day-to-day

Web. After its summer lows, the stock price recovered,

operations of Schwab, leaving Charles Schwab to focus on his

ending the year up 130% and pushing Schwab’s market

corporate marketing and PR role). His rst task was to enroll

capitalization past that of Merrill Lynch.14

the support of the company’s largest shareholder, Charles

Schwab. With 52 million shares, Schwab would take the

biggest hit from any share price decline. According to a

C4-3d 2000–2004: After the Boom

Fortune article, the conversation between Schwab and

In 1998, Charles Schwab appointed his long-time

Pottruck went something like this:13

number two, David Pottruck, co-CEO. The

appointment signaled the beginning of a leadership

Pottruck: “We don’t know exactly what will happen. The

transition, with Schwab easing himself out of day-to-

budget is shaky. We’ll be winging it.” Schwab: “We can

day operations. Soon Pottruck had to deal with some always adjust our costs.”

major issues. The end of the long stock market boom

Pottruck: “Yes, but we don’t have to do this now. The whole

of the 1990s hit Schwab hard. The average number

year could be lousy. And the stock!”

of trades made per day through Schwab fell from

Schwab: “This isn’t that hard a decision, because we really

300 million to 190 million between 2000 and 2002.

have no choice. It’s just a question of when, and it will be

Re ecting this, revenues slumped from $7.1 billion to harder later.”

$4.14 billion and net income from $803 million to

$109 million. To cope with the decline, Schwab was

Having got Schwab’s founder to agree, Pottruck formed a

forced to cut back on its employee headcount, which

task force to look at how best to implement the decision. The

fell from a peak of nearly 26,000 employees in 2000

plan that emerged was to merge all the company’s electronic

to just over 16,000 in late 2003.

services into Schwab.com, which would then coordinate

Schwab’s strategic reaction to the sea change in

Schwab’s online and off-line business. The base commission

market conditions was already taking form as the

rate would be $29.95, whatever channel was used to make a

market implosion began. In January 2000, Schwab

trade— online, branch, or telephone. The role of the

acquired U.S. Trust for $2.7 billion. U.S. Trust, a 149-

branches would change as they started to focus more on

year-old investment advisement business, managed

customer support. This required a change in incentive

money for high-net-worth individuals whose

systems. Branch employees had been paid bonuses on the

invested assets exceed $2 million. When acquired,

basis of the assets they accrued to their branches, but now

U.S. Trust had 7,000 customers and assets of $84

they would be paid bonuses on assets that came in via the

billion, compared to 6.4 million customers and

branch or the Web. They would be rewarded for directing

assets of $725 billion at Schwab.15 clients to the Web. lOMoAR cPSD| 58097008 Case 4 Charles Schwab C-61

According to Pottruck, widely regarded as the

but objectivity, not in uenced by corporate

architect of the acquisition, Schwab made the

relationships, investment banking, or any of the

acquisition because it discovered that high net above.”17

worth individuals were starting to defect from

Critics of this strategy were quick to point out

Schwab for money managers like U.S. Trust. The

that many of Schwab’s branch employees lacked

main reason: As Schwab’s clients grew older and

the qualications and expertise to give nancial

richer, they needed institutions that specialized in

advice. At the time the service was announced,

services that Schwab didn’t offer—including

Schwab had some 150 quali ed nancial advisers in

personal trusts, estate planning, tax services, and

place, and planned to have 300 by early 2003.

private banking. With baby boomers starting to

These elite employees required a higher salary than

enter middle to late middle age, and their average

the traditional Schwab branch employees, who in

net worth projected to rise, Schwab decided it

many respects were little more than order takers

needed to get into this business or lose high-net-

and providers of prepackaged information. worth clients.

The Schwab Private Client service caused further

The decision, though, began to bring Schwab

grumbling among the private nancial advisors af liated with

into con ict with the network of 6,000 or so

Schwab. In 2002, there were 5,900 of these. In total their

independent nancial advisors that the company had

clients amounted to $222 billion of Schwab’s $765 billion in

long fostered through the Schwab Advisers

client assets. Several stated that they would no longer keep

Network, and who funneled customers and assets

clients’ money at Schwab. However, Schwab stated that it

into Schwab accounts. Some advisors felt that

would use the Private Client Service as a device for referring

Schwab was starting to move in on their turf, and

people who wanted more sophisticated advice than Schwab

they were not too happy about it.

could offer to its network of registered nancial advisers, and

In May 2002, Schwab made another move in

particularly an inner circle of 330 advisers who have an

this direction when it announced that it would

average of $500 million in assets under management and 17

launch a new service targeted at clients with more

years of experience.18 According to one member of this

than $500,000 in assets. Known as Schwab Private

group, “Schwab is not a threat to us. Most people realize the

Client, and developed with the help of U.S. Trust

hand holding it takes to do that kind of work and Schwab

employees, for a fee of 0.6% of assets Private Client

wants us to do it. There’s just more money behind the

customers could meet face to face with a nancial

Schwab Advisors Network. The dead wood is gone, and rms

consultant to work out an investment plan and

like ours stand to bene t from even more additional leads.”19

return to the same consultant for further advice.

In 2003, Schwab stepped down as co-CEO, leaving

Schwab stressed that the consultant would not tell

Pottruck in charge of the business but staying on as

clients what to buy and sell—that was still left to the

chairman). In late 2003, Pottruck announced that Schwab

client. Nor would clients get the legal, tax and estate

would acquire Soundview Technology Group for $321

planning advice offered by U.S. Trust and

million. Soundview was a boutique investment bank with a

independent nancial advisors. Rather, they got a

research arm that covered a couple of hundred companies

nancial plan and consultation regarding industry

and offered this research to institutional investors such as and market conditions.16

mutual fund managers. Pottruck justi ed the acquisition by

To add power to this strategy, Schwab

arguing that it would have taken Schwab years to build

announced that it would start a new stock rating

similar investment research capabilities internally. His plan

system. It would be not the work of nancial analysts

was the have Soundview’s research bundles for Schwab’s

but rather the product of a computer model, retail investors.

developed at Schwab, to analyze more than 3,000

stocks on 24 basic measures such as free cash ow,

sales growth, insider trades, and so on, and then

assigns grades. The top 10% get an A, the next 20%

a B, the middle 40% a C, the next 20% a D, and the

lowest 10% an F. Schwab claimed that the new

system was “a systematic approach with nothing lOMoAR cPSD| 58097008 C-62 Case 4 Charles Schwab

C4-3e 2 004–2008: The Return of

C4-3f The Great Financial Crisis and Charles Schwab Its Aftermath

The Soundview acquisition proved to be Pottruck’s undoing.

The great nancial crisis that hit the nancial services industry

It soon became apparent that it was a huge mistake. There

in 2008–2009 had its roots in a bubble in housing prices in

was little value to be had for Schwab’s retail business from

the United States. Financial service rms had been bundling

Soundview. Moreover, the move had raised Schwab’s

thousands of home mortgages together into bonds, and

operating costs. By mid-2004, Pottruck was trying to sell

selling them to investors worldwide. The purchasers of those

Soundview. The board, disturbed by Pottruck’s vacillating

bonds thought that they were buying a solid nancial asset

strategic leadership, expressed their concerns to Charles

with a guaranteed payout—but it turned out that the quality

Schwab. On July 15, 2004, Pottruck was red, and 66-year-old

of many of the bonds was much lower than indicated by

Charles Schwab returned as CEO.

bond-rating agencies such as Standard & Poor’s. Put

He moved quickly to refocus the company. Sound view

differently, there was an unexpectedly high rate of default on

was sold to the investment bank UBS for $265 million.

home mortgages in the United States.

Schwab reduced the workforce by another 2,400 employees,

At the top of the housing bubble, many people

closed underperforming branches, and removed $600

were paying more than they could afford to for

million in annual cost. This allowed him to reduce

homes. Banks were only too happy to lend them

commissions on stock trades by 45%, and take market share

money because they assumed, incorrectly as it

from other discount brokers such as Ameritrade and E*Trade.

turned out, that if the borrower faced default, the

Going forward, Schwab reemphasized the rm’s traditional

home could be sold for a pro t and the balance on

mission—to empower investors and provide them with

the mortgage paid off. The aw in this reasoning was

ethical nancial services. He also reemphasized the

the assumption that the underlying asset—the

importance of the relationships that Schwab had with

house—could be sold, and that home pricing would

independent investment advisors. He noted: “Trading has

continue to advance. There had been massive

become commoditized. The future is really about competing

overbuilding in the United States. By 2007, home

for client relationships.”20 One major new focus was the

prices were falling as it became apparent that there

company’s retail banking business. Established in 2002, it had

was too much excess inventory in the system. The

been a low priority for Pottruck. Now Schwab wanted to

net result: many supposedly high-quality mortgage-

make the company a single source for banking, brokerage,

backed bonds turned out to be nothing more than

and credit card services—one that would give Schwab’s

junk, and prices for these bonds fell precipitously.

customers something of value: a personal relationship they

Institutions holding these bonds had to write down

could trust. The goal was to lessen Schwab’s dependence on

their value, and their balance sheets started to

trading income, and give it a more reliable earnings stream

deteriorate rapidly. As this occurred, other nancial

and a deeper relationship with clients.

institutions became increasingly reluctant to lend

In mid-2007, Schwab’s reorientation back to its tradi

money to those institutions seen as being

tional mission reached a logical conclusion when U.S. Trust

overexposed to the housing market. Suddenly, the

was sold to Bank of America for $3.3 billion. Unlike in the

banking system was facing a major credit crunch.

past, however, Schwab was no longer earning the bulk of its

As the crisis unfolded, several major nancial

money from trading commissions. As a percentage of net

institutions went bankrupt, including Lehman

revenues, trading revenues (mostly commissions on stock

Brothers (a major player in the market for mortgage-

trades) were down from 36% in 2002 to 17% in 2007. By

backed securities) and Washington Mutual (one of

2007, asset management fees accounted for 47% of Schwab’s

the nation’s largest mortgage originators). AIG, a

net revenue—up from 41% in 2002—while net interest

major insurance company which had built a big

revenue (the difference between earned interest on assets

business in the 2000s selling default insurance to the

such as loans and interest paid on deposits) was 33%, up

holders of mortgage-backed securities, faced

from 19% in 2002.21 Schwab’s overall performance had also

massive potential claims and had to be rescued from

improved markedly. Net income in 2007 was $1.12 billion, up

bankruptcy by the U.S. government, which took an

from a low of $396 million in 2003.

80% stake in AIG in return for providing loans worth

$182 billion. The government also created a $700- lOMoAR cPSD| 58097008 Case 4 Charles Schwab C-63

billion fund—the Troubled Asset Relief Program—

by 2011 as more and more customers transacted

that banks could draw upon the shore up their

online with the company. Despite this decline,

balance sheets and meet short-term obligations.

Schwab has concluded that a physical retail

While these actions managed to arrest the most

presence remains a powerful means of gathering in

serious crisis to hit the global nancial system since

new accounts and holding onto existing accounts.

the Great Depression of 1929, they could not stave

Rather than open more storefronts, however, which

off a severe, prolonged recession and a major

entails signi cant costs, the company has opted for

decline of the market value of most nancial

a different strategy; it has decided to open institutions.

additional retail branches using independent

Almost alone among major nancial institutions,

operators in what amounts to a franchise system.

Schwab sailed through the nancial crisis with

The ultimate goal is to triple the branch network to

relative ease. The rm had steered well clear of the

around 1,000. Detractors worry that Schwab risks

feeding frenzy in the U.S. housing and mortgage

diluting its powerful brand if the independent

markets. Schwab did not originate mortgages, and

operators do not offer the same level of service that

nor did it hold mortgage-backed securities on its

people have become accustomed to at traditional

balance sheet. Schwab had no need to draw on

Schwab branches. For its part, Schwab executives

government funds to shore up its balance sheet.

have stated that it is their intention that a client

The company remained pro table, and although

walking into an independently owned Schwab

revenues and earnings did fall from 2007 to 2009,

branch will not know the difference and would get

the balance sheet remained strong.

the same service and products as at company-

By 2010, Schwab was once more on a growth owned branches.22

path, although extremely low interest rates in the

Second, Schwab has made a big push into the exchange

United States and elsewhere limited its ability to

traded fund business (EFTs). EFTs are passively managed

earn money from the spread between what it paid

index funds, such as an S&P 500 index fund. EFTs have grown

to depositors and the amount it could earn by

into a $4 trillion-dollar industry since the rst EFT was

investing depositors’ money on the short-term

introduced 25 years ago. EFTs are attractive because they

money markets. Some 40% of Schwab’s revenues

trade like stocks on a regulated exchange while providing

are tied to interest rates, and as long as interest

diversity within a single investment product. Since EFTs are

rates remain very low, Schwab’s ability to earn pro t

passively managed, expense ratios are typically lower than

here is limited. On the other hand, earnings could

those for actively managed mutual funds. Schwab started to

expand signi cantly if rates return to pre-crisis

offer EFTs in the 2000s, and in 2013 it announced the launch levels.

of Schwab EFT OneSource trading platform. Modeled on

Charles Schwab stepped down as CEO on July

Schwab’s successful mutual fund market place, this provides

22, 2008, passing the reins of leadership to Walter

access to more than 200 EFTs and offers $0 online trade

Bettinger, although Schwab continues to be

commissions. Schwab will make money from charging fund

involved in major strategic decisions as an active

distribution fees, as it does with mutual funds.

chairman. Under Bettinger, the company has

charted a conservative course. The main goal has

been to grow the net asset base of the rm by

attracting more clients. The stellar performance of C4-4 CONCLUSION

Schwab though the nancial crisis, and its continuing

strong brand, has certainly helped in this regard.

As of 2018, Schwab seemed to be ring on all cylinders. During

From 2008 to 2016, Schwab has generated 5 to 8%

2017, the company increased its assets under management

annual growth in its asset base. To keep doing so

by $199 billion, to $3.4 trillion. The total client assets under

going forward, the company has launched couple of

management had doubled in just 6 years. Some 1.4 million other initiatives.

new accounts were opened at Schwab in 2017, the highest

First, in 2011, it announced a plan to expand its

number in 17 years. Schwab was pro table, boasted one of

physical retail presence. Schwab’s branches had

the lowest cost structures in the industry, and was gaining

declined in number from 400 in 2003 to around 300

market share from competitors. Twice as many assets were lOMoAR cPSD| 58097008 C-64 Case 4 Charles Schwab

transferred in from rivals during 2017 as were transferred

The top-line goal was to continue to grow the business by out.

offering low costs, excellent customer service, and a wide

range of investment options. The company articulated ve principles to guide its lOMoAR cPSD| 58097008 Case 4 Charles Schwab C-65 September 27, 1988, p. 1.

Reinvented the Brokerage Industry.

pansion, Tighten Belt Because of Post Technology, pp. 19–20. Fortune pp. 52–59.

Reinvented the Brokerage Industry,

Reinvented the Brokerage Industry, Fortune