Preview text:

Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics

Ethically minded consumer behaviour in Vietnam: An analysis of cultural values,

personal values, attitudinal factors and demographics Tri D. Le, Tai Anh Kieu, Article information: To cite this document:

Tri D. Le, Tai Anh Kieu, (2019) "Ethically minded consumer behaviour in Vietnam: An analysis of

cultural values, personal values, attitudinal factors and demographics", Asia Pacific Journal of

Marketing and Logistics, https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-12-2017-0344

Permanent link to this document:

https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-12-2017-0344

Downloaded on: 20 March 2019, At: 09:28 (PT)

References: this document contains references to 81 other documents.

To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com

The fulltext of this document has been downloaded 10 times since 2019*

Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by emerald- srm:305060 [] At 09:28 20 March 2019 (PT) For Authors

If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald

for Authors service information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission

guidelines are available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information.

About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com

Emerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The company

manages a portfolio of more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes, as

well as providing an extensive range of online products and additional customer resources and services.

Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the

Downloaded by University of Florida

Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation.

*Related content and download information correct at time of download.

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at:

www.emeraldinsight.com/1355-5855.htm Ethically minded consumer EMCB in Vietnam behaviour in Vietnam

An analysis of cultural values, personal values,

attitudinal factors and demographics Tri D. Le Received 29 December 2017

School of Business, International University, VNU-HCM, Revised 7 June 2018 Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam and 19 October 2018 19 December 2018

School of Economics, Finance and Marketing, RMIT University, Accepted 4 January 2019 Melbourne, Australia, and Tai Anh Kieu

Department of Research Administration – International Relations,

University of Economics Ho Chi Minh City, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam Abstract

Purpose – Consumer ethics in Asia has attracted attention from marketing scholars and practitioners.

Ethical beliefs and judgements have been predominantly investigated within this area. Recent research

argues for consumer ethics to be measured in terms of behaviours rather than attitudinal judgements, due to a At 09:28 20 March 2019 (PT)

potential pitfall of attitudinal scales, which researchers often refer to as an attitude–behaviour gap.

Accordingly, the purpose of this paper is to examine the dimensions of ethically minded consumer behaviour

(EMCB) in an Asian emerging market context.

Design/methodology/approach – A survey of 316 Vietnamese consumers was conducted to investigate

their ethically minded behaviours.

Findings – The SEM analyses reveal a significant impact of long-term orientation on EMCB, whereas

spirituality has no impact. Collectivism, attitude to ethically minded consumption and subjective norms are

found to influence the dimensions of EMCB. Age, income and job levels have effects on EMCB dimensions,

but gender, surprisingly, has no effect.

Practical implications – The study can be beneficial to businesses and policy makers in Vietnam or any similar

Asian markets, especially in encouraging people to engage with ethical consumption. Furthermore, it provides

practitioners in Vietnam with a measurement instrument that can be used to profile and segment consumers.

Originality/value – This is among the first studies utilising and examining EMCB, especially in Vietnam

where research into consumer ethics is scant. It contributes to the body of knowledge by providing a greater

understanding of the impact of personal characteristics and cultural environment on consumer ethics, being

Downloaded by University of Florida

measured by the EMCB scale which has taken into account the consumption choices. Furthermore, this study

adds further validation to the EMCB scale.

Keywords Long-term orientation, Consumer ethics, Spirituality, Attitude, Emerging markets, Collectivism,

Ethical consumption, Subjective norms, Love of money Paper type Research paper Introduction

Research into consumer ethics appears to have proliferated since the development of Muncy

and Vitell’s (1992) Consumer Ethics Scale (CES). The CES is conceptualised as consumers’

ethical judgments, which are the extent to which the consumer perceives ethically

questionable practices as being either right or wrong (ethical or unethical) across situations

(Muncy and Vitell, 1992; Vitell and Muncy, 1992). Nonetheless, attitudinal scales such as

ethical judgments may not reliably predict ethical consumption (Carrigan and Attalla, 2001;

Carrington et al., 2014; Sudbury-Riley and Kohlbacher, 2016). For example, the Nielsen

Global Survey of Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability found that 26 per cent Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics

of consumers indicated that they wanted more eco-friendly products but only 10 per cent © Emerald Publishing Limited 1355-5855

said that they purchased such products (Nielsen, 2015a). To address this disparity, well DOI 10.1108/APJML-12-2017-0344 APJML

documented as the attitude–behaviour gap, some researchers argue for consumer ethics to

be assessed in terms of behaviours rather than attitudinal judgements (Carrigan et al., 2011;

Carrington et al., 2016; Caruana et al., 2016). In the light of this, Sudbury-Riley and

Kohlbacher (2016) recently developed an “ethically minded consumer behaviour” (EMCB)

scale, based on Roberts’ (1993, 1995) prior work on socially responsible consumer behaviour,

to measure consumption choices with regard to environmental issues and corporate social

responsibility. The EMCB scale comprises five separate dimensions capturing a variety of

ecological/social and purchase/boycott behaviours (Sudbury-Riley and Kohlbacher, 2016).

On the other hand, prior research has largely drawn on Hunt and Vitell’s (1986, 1993)

general theory of marketing ethics to investigate the impact of selected personal and

cultural characteristics in driving ethical judgements, e.g., Lu and Lu (2010), Arli and

Tjiptono (2014) and Vitell et al. (2016). It is noteworthy that research in different research

contexts has found conflicting results and some even contradicting the theory, with regard

to the role of religion and consumers’ views of material goods or money (Arli and Tjiptono,

2014; Lu and Lu, 2010; Vitell et al., 2016). The question that arises which motivates this

study is whether and to what extent well-examined antecedents of ethical judgements in

prior research would also associate with the EMCB dimensions. Therefore, this study, by

extending the work of Sudbury-Riley and Kohlbacher (2016) and prior research concerning

ethical judgments, aims to investigate the roles of selected antecedent constructs

representing personal characteristics and cultural environment in shaping EMCB

dimensions, in lieu of ethical judgements.

In this sense, the study attempts to integrate the perspectives of both Fishbein and At 09:28 20 March 2019 (PT)

Ajzen’s (2010) reasoned action approach and Hunt and Vitell’s (1986, 1993) general theory of

marketing ethics. Specifically, the present study concurs with Sudbury-Riley and

Kohlbacher’s (2016) research in considering the reasoned action approach/theory of

planned behaviour as useful in explaining ethical behaviour; and, as such, includes two

important variables of that theoretical approach: attitude towards ethical consumption, and

subjective norms. Besides, the present research extends previous studies, such as Lu and Lu

(2010), Arli and Tjiptono (2014) and Vitell et al. (2016), to investigate the roles of selected

cultural and personal predictors of consumer ethics (such as love of money, spirituality,

long-term orientation, collectivism and demographics) in shaping ethical consumption,

represented by EMCB dimensions. Furthermore, given the novel nature of the EMCB scale,

this study focusses on the direct associations between EMCB dimensions and selected

cultural and personal predictors in a particular Asian developing market.

Downloaded by University of Florida

Despite the growing potential of Asia, the extant literature shows limited research into

consumer ethics, let alone for the emerging markets in the region (Arli and Tjiptono, 2014;

Lu and Lu, 2010). Research into consumer ethics so far focusses much on developed markets

such as North America and Europe, which currently account a larger share of ethical

products (Nielsen, 2015a). Nonetheless, it is worth noting that nowadays consumers in

developing markets also become more interested in seeking out and paying more for ethical

products (Euromonitor, 2017; Nielsen, 2015a). More particularly, the present research is

conducted in Vietnam, as this country presents a meaningful research context to investigate

EMCB and provides a different consumer profile from the Western cultures and

Islam-dominant contexts in previous studies. Vietnam is a sizeable, fast-growing Asian

emerging market which has transitioned from centrally planned to market economy just

over two decades ago. The country has a population exceeding 92m, with a growing middle

class (World Bank, 2017), a collectivist culture and a coexistence of several religions, with

many people claiming “no religion” despite their religious practices (Shultz, 2012). A survey

by Nielsen (2015b) found that Vietnamese consumers are most socially conscious, as they

came top in the Asia-Pacific region in stating a willingness to pay for products from

companies that care about environmental and social values.

This study is one of the first few studies utilising and examining EMCB and provides a EMCB in

greater understanding of the impact of selected antecedents on EMCB. Furthermore, Vietnam

evidence from the emerging market context of Vietnam, where research into consumer

ethics is scant, also contributes to furthering theoretical advances and maintaining their

managerial relevance. Insights from the study can benefit businesses and policy makers in

encouraging consumers to engage with ethical consumption. Literature review

Consumer ethics and theoretical foundations

Much research into consumer ethics in the past three decades has been based on the general

theory of marketing ethics by Hunt and Vitell (1986, 1993) and centred around the concept of

ethical judgments. The theory conceptualises a general framework explicating broad sets of

factors and mechanisms leading to one’s ethical behaviour (Hunt and Vitell, 1986, 1993).

Researchers subsequently argue that only two sets of factors are relevant to the

consumption context: cultural and personal characteristics (Vitell et al., 2016). It is

noteworthy that at the heart of that general framework is the concept of one’s ethical

judgements, which are evaluations of behaviour but also include implicitly environmental

norms and personal characteristics in ethically questionable situations (Hunt and Vitell,

1986). Subsequently, several researchers embrace ethical judgements as a hallmark concept

of consumer ethics (Hunt and Vitell, 1986, 1993; Muncy and Vitell, 1992; Vitell and Muncy,

1992). In this vein, the Muncy–Vitell CES was developed to measure consumers’ judgments

of certain behaviours across a range of ethical issues/situations (Muncy and Vitell, 1992; At 09:28 20 March 2019 (PT)

Vitell and Muncy, 1992). The original CES scale included four dimensions, each consisting of

actions that consumers perceived as being wrong, labelled as “actively benefiting” from

illegal activities, “passively benefiting” at the seller’s expense, “deceptive, legal practices”

and “no harm activities” (Muncy and Vitell, 1992; Vitell and Muncy, 1992). A fifth dimension,

labelled as “doing good” and reflected by positive actions relating to good deeds and

recycling, was added later (Vitell and Muncy, 2005).

There are problems with the focus on ethical judgments. First, several studies have

produced mixed evidence for the CES dimensions across cultures, challenging the validity of

the scale (Polonsky et al., 2001). For example, consumers in Austria appear to be more

tolerant to questionable behaviours (excepting for actively benefiting from illegal activities)

(Rawwas, 1996). Some CES dimensions such as “deceptive, legal practices” and “no harm

activities” are found indeed to be ambiguous, because actions grouped under these

Downloaded by University of Florida

dimensions are considered acceptable in some cultures but harmful by others (e.g. copying a

CD) (Vitell et al., 2016). Second, the inherently higher abstraction level of the concept of

ethical judgments inhibits the understanding of the relative roles of behavioural beliefs (e.g.

attitude towards behaviour) and normative beliefs (e.g. subjective norms) separately, as in

Fishbein and Ajzen’s (2010) reasoned action approach. This makes it difficult for marketers

to design interventions to impact intentions and behaviour. Third, research in practice has

shown the potentially serious disparity between consumers’ attitude towards ethics and

actual purchasing behaviour (Nielsen, 2015a, b). Therefore, it has been contended that

ethical judgments are insufficient to predict ethical consumer behaviour (De Pelsmacker

et al., 2005; Fukukawa and Ennew, 2010). Nonetheless, research into consumer ethics so far

has fallen short of considering actual behaviour, which could be shaped by situational

constraints (Hunt and Vitell, 1986).

Some researchers suggest that the attitude–behaviour gap can be explained in the light

of Fishbein’s and Ajzen’s (2010) reasoned action approach, which encapsulates the theory

of reasoned action (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975) and its extension, the theory of planned

behaviour (Ajzen, 1991). The reasoned action approach posits that not only attitude

towards behaviour but also subjective norms and perceived behaviour control can impact APJML

intentions and behaviour (Fishbein and Ajzen, 2010). Accordingly, empirical research

applying the reasoned action approach in an ethical consumption context demonstrates

that attitudes alone, or scales designed solely to measure attitude, are poor predictors of

ethical consumer behaviours (Shaw et al., 2000; Vermeir and Verbeke, 2006, 2008).

Indeed, the extent to which consumers act on their ethical beliefs and their rationales for

inaction are less consistent across cultures (Auger et al., 2007). Therefore, it is also

proposed that research may need to take into account actual behaviour rather than

attitude (Sudbury-Riley and Kohlbacher, 2016). In line with this, Sudbury-Riley and

Kohlbacher (2016) develop the EMCB scale.

Drawing upon the extant literature on consumer ethics, this study attempts to apply

the perspectives of the reasoned action approach and the general theory of

marketing ethics as theoretical foundations. The two theoretical approaches are indeed

consistent with each other. In their general theory of marketing ethics, Hunt and Vitell

(1986) claimed that ethical judgments have impact on intentions and, subsequently,

behaviour, a key mechanism of the reasoned action approach (Fishbein and Ajzen, 2010).

In addition, with the extension of the theory of reasoned action to make the theory of

planned behaviour, Ajzen (1991) suggested that the theory of planned behaviour

framework is open to include the additional predictors of behaviour. Therefore, besides

attitude towards ethical consumption behaviour and subjective norms, the present study

follows prior research that has drawn on Hunt–Vitell’s theory to identify predictors of

consumer ethics, and extends these to investigate the roles of selected cultural

and personal predictors of consumer ethics (such as love of money, spirituality, long-term At 09:28 20 March 2019 (PT)

orientation, collectivism and demographics) in influencing EMCB dimensions. This is

of particular importance, as marketers need to know how to influence ethical consumer

behaviour (Carrington et al., 2010).

Given the novel nature of the EMCB scale, this study focusses only on the improved

understanding of predictors of EMCB dimensions, and is not concerned with the processes

linking consumer values and EMCB dimensions through intervening variables. Although

consumers values or characteristics may be argued to influence the formation of an

individual’s attitude, which can then impact behaviour (Grunert and Juhl, 1995; Hunt and

Vitell, 1986; Poortinga et al., 2004; Yeon Kim and Chung, 2011), most previous empirical

studies have investigated the direct associations between consumer ethics, measured as

consumer judgements, and selected exogenous antecedents. Accordingly, this study

examines the direct associations between cultural and personal values and EMCB

dimensions. These concepts are further discussed in the sections below.

Downloaded by University of Florida

Ethically minded consumer behaviour

The EMCB scale follows the 26-item scale developed by Roberts and Lilien (1993) to

measure socially responsible consumer behaviour, which taps into both ecological

and social issues as a starting point. Sudbury-Riley and Kohlbacher (2016) classified

five distinctive dimensions of EMCB relative to ecological and social issues: Eco–Buy,

Eco–Boycott, Recycle, CSR–Boycott and Pay–More. The first dimension, Eco–Buy, refers

to the deliberate selection of environmentally friendly products over other alternatives

(e.g. “When there is a choice, I always choose the product that contributes to the least

amount of environmental damage”). The second dimension, Eco–Boycott, represents the

refusal to purchase the products which are harmful to the environment (e.g. “If I

understand the potential damage to the environment that some products can cause, I do

not purchase those products”). The third dimension, Recycle, is the intentional selection

based on special recycling issues (e.g. “Whenever possible, I buy products packaged in

reusable or recyclable containers”). The fourth dimension, CSR–Boycott, refers to the

refusal to purchase the products based on social issues (e.g. “I do not buy products from

companies that I know use sweatshop labour, child labour, or other poor working EMCB in

conditions”). Finally, the last set of behaviours, comprising Pay–More, refers to the Vietnam

willingness to spend more for ethical products (e.g. “I have paid more for environmentally

friendly/socially responsible products when there is a cheaper alternative”).

The scale has been argued to address the attitude–behaviour gap relating to ethical

consumption, as it measures actual behaviour, though not in an observation way

(Sudbury-Riley and Kohlbacher, 2016). In relation to other behavioural scales of

consumer ethics, Sudbury-Riley and Kohlbacher (2016) argue that their scale captures

overall ethical consumption related to both broad environmental and social issues, rather

than just particular ethical behaviours such as fair trade (e.g. Shaw et al., 2000), organic

food consumption (e.g. Hughner et al., 2007), socially conscious purchasing (e.g. Pepper

et al., 2009), green marketing or environmentally friendly purchasing behaviour

(Schlegelmilch et al., 1996; Tantawi et al., 2009). Furthermore, the scale incorporates an

important dimension relating to price, which is often considered as one possible

explanation of the attitude–behaviour gap (Sudbury-Riley and Kohlbacher, 2016).

Some researchers argue that factors such as price and value could outweigh ethical

criteria (Carrigan and Attalla, 2001). Given the advantages of the EMCB scale over

attitudinal scales such as ethical judgments, as discussed by Sudbury-Riley and

Kohlbacher (2016), an understanding of the roles of antecedents often used in prior

research in explaining EMCB dimensions could provide a basis for designing

interventions to influence ethical consumer behaviour.

Love of money. The extant literature suggests that money is related to a consumer’s At 09:28 20 March 2019 (PT)

individual characteristics, and that consumers’ attitude towards money could be one of

determinants of their ethical judgements (Hunt and Vitell, 1993; Vitell et al., 2007). The love

of money refers to an individual’s desire for, value of and aspirations for money (Flurry and

Swimberghe, 2016). Those who love money see it as instrumental to happiness and as a

means to display social status and a sign of success (Tang, 2007; Tang and Liu, 2012).

Theory suggests that one’s greater love of money is likely to explain their greater likelihood

of engaging in unethical behaviour (Elias, 2013; Flurry and Swimberghe, 2016). However,

prior research examining the relationship between love of money and various dimensions of

CES reveal that love of money is not related to ethical judgements relating to active/illegal

practices and doing good (Vitell et al., 2006, 2007). Nevertheless, Vitell et al. (2006, 2007)

argue that consumers who love money were less likely to perceive questionable behaviours

as unethical and to do good things without obvious monetary gain. Given that research has

Downloaded by University of Florida

yet to investigate the relationship between love of money and EMCB, this appears to be an

appropriate construct to examine in relation to EMCB. It seems logical that one who exhibits

a higher love of money will be less likely to be willing to pay more money for an ethical

product. Thus, it can be hypothesised that:

H1. Love of money is negatively related to the dimensions of EMCB: (a) Eco–Buy, (b)

Eco–Boycott, (c) Recycle, (d) CSR–Boycott and (e) Pay–More.

Spirituality. Spirituality is a relatively new research construct which refers to values,

ideals and virtues that one is committed to (Vitell et al., 2016). This construct is closely

related to, but distinctive from, religiosity (Chen and Tang, 2013; Chowdhury and

Fernando, 2013). In fact, prior research on religiosity distinguishes intrinsic religiosity

and extrinsic religiosity: the former taps into one’s commitment to one’s religious

principles and values without expecting anything in return; and the latter refers to the

extent to which religion serves one’s social or business goals (Allport and Ross, 1967;

Vitell et al., 2009). In this vein, the extrinsic dimension does not measure religiosity

per se (Bakar et al., 2013). Prior research also reveals that intrinsic religiosity rather

than extrinsic religiosity is closely associated with consumers’ ethical judgements APJML

(Bakar et al., 2013; Vitell and Muncy, 2005). Furthermore, just as spirituality is closely

related to intrinsic religiosity and appears to be more universal, spirituality is suggested

to be examined in lieu of religiosity in order to control for differences across religions, and

even perhaps to be applicable for those of no particular religious affiliation (Vitell et al.,

2016). As such, spirituality is considered a logical surrogate of religiosity in research that

could involve people with various, or no, religious membership (Vitell et al., 2016). Thus, it

appears to be meaningful to investigate the relationship between spirituality, in lieu of

intrinsic religiosity, and EMCB. Several studies have found a positive relationship

between intrinsic religiosity and beliefs that questionable consumer activity is unethical

(e.g. Patwardhan et al., 2012; Singhapakdi et al., 2013; Vitell et al., 2007). The results of

Vitell et al. (2016) show that consumers’ spirituality relates to their judgements of

questionable activities, but not to doing-good activities. This does not mean that highly

spiritual consumers do not look upon ethical behaviours, but that perhaps spirituality is

not related to specific activities such as recycling. It appears to be logical that those with

higher spirituality are likely to have a greater level of commitment towards moral and

ethical beliefs (Vitell et al., 2005). Thus, it can be hypothesised that:

H2. Spirituality is positively related to the dimensions of EMCB: (a) Eco–Buy,

(b) Eco–Boycott, (c) Recycle, (d) CSR–Boycott, and (e) Pay–More.

Attitude to ethical consumption. General theories of consumer behaviour have defined

attitude as one of the key antecedents of behaviour (Ajzen, 1991; Fishbein and Ajzen, 2010;

Hunt and Vitell, 2006). Under the conditions of these two theories, attitude towards the act is At 09:28 20 March 2019 (PT)

an important antecedent of behavioural intention, which in turn impacts behaviour.

Researchers point to the intention–behaviour gap as a limitation of these theories’

explanatory power (Sudbury-Riley and Kohlbacher, 2016). Rather than using those theories

as a guide, some researchers instead examine the direct relationship between attitude and

behaviour. For example, attitude towards the software piracy and purchases of illegal copies

of music CDs positively affects consumer’s digital piracy behaviour (Arli et al., 2015). Vitell

and Muncy’s (1992) research posited that consumers who hold more positive attitude

towards illegal acts have a higher tendency to engage in questionable consumer behaviours.

In a similar vein, Chan et al. (1998) revealed that there is a significant correlation between

attitude towards illegal acts and actively benefiting from an illegal activity. Based on those

empirical findings, it can be hypothesised that:

H3. Attitude to ethical consumption is positively related to the dimensions of EMCB:

Downloaded by University of Florida

(a) Eco–Buy, (b) Eco–Boycott, (c) Recycle, (d) CSR–Boycott and (e) Pay–More.

Subjective norms to ethical consumption. Another construct widely used in investigating the

antecedents of human behaviour is subjective norms (Ajzen, 1991; Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975;

Olsen and Grunert, 2010). The subjective norms construct is an individual-level

measurement which refers to the extent to which the consumer perceives social pressure

from relevant others on them in performing or not performing the behaviour (Ajzen, 1991).

Fielding, Terry, Masser and Hogg (2008) provide empirical support for the significant link

between the reconceptualised subjective norm and sustainable agricultural practices.

Consistent with this, research has also provided empirical evidence for the significant

relationship between social influence and purchase behaviour of products with

environmental and ethical claims (Bartels and Onwezen, 2014) or decision to purchase

environmentally friendly products (Salazar et al., 2013). Some research has found that group

norms, which refers to the expectations of behaviourally relevant reference groups, are

predictive of behaviour, rather than expectations of generalised others (Fielding, McDonald

and Louis, 2008). It has been argued that the subjective norms construct is an important

determinant of sustainable behaviour, adding predictive power in explaining intention and

behaviour (Fielding, McDonald and Louis, 2008; Johe and Bhullar, 2016). Thus, it can be EMCB in hypothesised that: Vietnam

H4. Subjective norms to ethical consumption are positively related to the dimensions of

EMCB: (a) Eco–Buy, (b) Eco–Boycott, (c) Recycle, (d) CSR–Boycott and (e) Pay–More.

Long-term orientation and collectivism. Hunt–Vitell’s (1986) general theory of marketing

ethics considered culture as an antecedent in ethical reasoning. Most previous studies

postulated cultural environment using Hofstede’s (1984) cultural taxonomy which

encompasses five distinct cultural dimensions: power distance, uncertainty avoidance,

individualism/collectivism, femininity/masculinity and long-term orientation (Arli and

Tjiptono, 2014; Vitell et al., 2016). Once widely used to characterise a national culture at the

global/macro level, subsequently researchers argue that these cultural dimensions can be

measured at the individual/micro level (Arli and Tjiptono, 2014; Vitell et al., 2016). However,

notably, limited research has been conducted to examine the relationship between cultural

dimensions at the individual-level and consumers’ ethical judgements, especially on Asian

emerging market contexts (Arli and Tjiptono, 2014), let alone EMCB. Furthermore, previous

research has shown that only collectivism and long-term orientation are associated with

spirituality and consumer ethical predisposition (Vitell et al., 2016). In particular, evidence

has revealed that consumers with greater levels of collectivism and long-term orientation

are more likely to be predisposed to ethical judgments concerning “doing good” (Vitell et al.,

2016). Indeed, long-term orientation and collectivism are mostly accepted as the drivers of

pro-environment or positively ethical behaviours (Leonidou et al., 2010; Vitell et al., 2016). At 09:28 20 March 2019 (PT)

Moreover, researchers postulate that consumers in Asia, who score higher long-term

orientation values, would hold higher ethical values (Moon and Franke, 2000; Tsui and

Windsor, 2001). Drawing on previous evidence, the present study selects collectivism and

long-term orientation in the investigation of EMCB.

Long-term orientation refers to perseverance, thrift and sacrifice of present pleasures for

future success; whereas, at the opposite end, short-term orientation represents emphasises

on present-time successes, protecting one’s face, fulfilling social obligations, and personal

steadiness and stability (Hofstede, 2011; Vitell et al., 2016). Research has revealed that

consumers who are high in long-term orientation tend to hold higher levels of ethical values

(Arli and Tjiptono, 2014; Nevins et al., 2007). It makes sense that a consumer with an

orientation to the values of the future would be more likely to engage in ethical behaviour

for long-term benefit though they may have to sacrifice short-run benefits (Vitell et al., 2016).

Downloaded by University of Florida

In addition, those scoring high in terms of long-term orientation would be inclined towards

virtues consistent with future rewards and less towards immediate gratification (Vitell et al.,

2016). Thus, it can be hypothesised that:

H5. Long-term orientation is positively related to dimensions of EMCB: (a) Eco–Buy, (b)

Eco–Boycott, (c) Recycle, (d) CSR–Boycott and (e) Pay–More.

One pole of this dimension, labelled as individualism, is defined as the extent to which one

places importance on self-interest and individual freedom, and prefers loose ties with their

surrounding others (Hofstede, 1984). Its opposite pole, collectivism, refers to the extent to

which one views oneself as part of a group, hence putting group interests first and holding

greater respect for tradition (Hofstede, 1984; Vitell et al., 2016). Those who are high in terms

of collectivism place more importance on collective good over their own benefit, thus they

are likely to engage in doing-good practices (Vitell et al., 2016). Despite the theorising and

postulating that collectivistic consumers are more likely to follow norms and may break

rules, Vitell et al.’s (2016) study provides evidence that consumers with higher collectivistic

values are more likely to place higher value on “doing good” since this is the most visible

and positive dimension of their ethics. As such, it could be expected that, in collectivistic APJML

societies, as in many Asian countries, collectivistic consumers are also more likely to

consider the impact of their behaviour on society and favour activities for the sake of the

good of society as a whole. Thus, it can be hypothesised that:

H6. Collectivism is positively related to dimensions of EMCB: (a) Eco–Buy, (b) Eco–

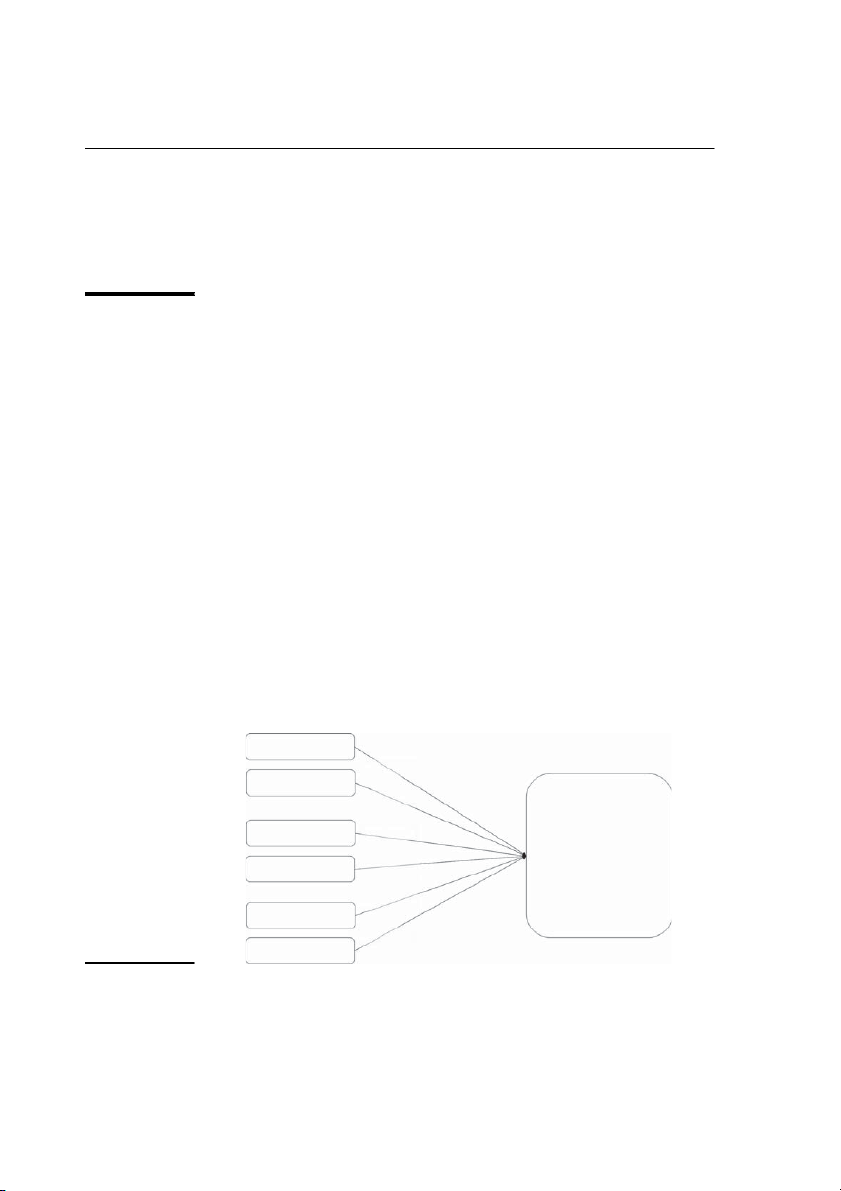

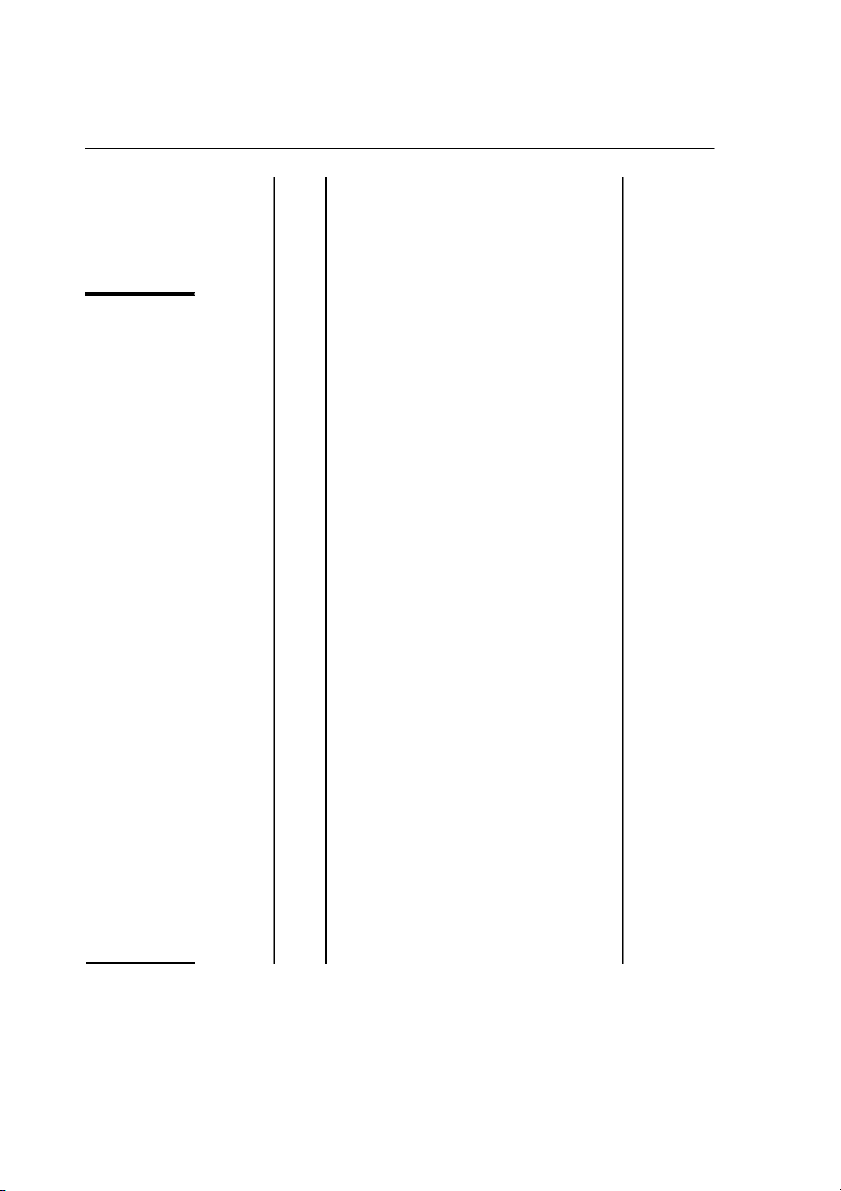

Boycott, (c) Recycle, (d) CSR–Boycott, and (e) Pay–MORE (Figure 1). Methodology Sample and procedure

Calls for participation in the survey were posted publicly on Facebook and LinkedIn to

recruit participants. Within the three-week timeframe of the survey, a total of 352

questionnaires were distributed. Of these 352 collected questionnaires, 316 questionnaires

were completed and usable for data analysis. Numbers of male and female respondents are

almost equal (50.9 per cent male and 47.8 per cent female). The age group is mostly from 20

to 40 years old, and most of the respondents have completed university (56 per cent) or a

postgraduate degree (40.8 per cent). The sample also indicates a wide range of incomes and

occupations, which is appropriate for analysing the impact of demographics on EMCB.

Regarding religion, the sample reflects the special culture in Vietnam, that many people are

usually self-classified as non-religious (47.5 per cent).

Measurement instrument and reliability At 09:28 20 March 2019 (PT)

The instrument comprises five sections. The first section is the measurement scale of EMCB

adopted from Sudbury-Riley and Kohlbacher (2016). Developed and extensively tested

among respondents in five countries, the finalised scale is comprised of ten items over five

dimensions. Over the five dimensions, as outlined above, respondents rated the ethical

consumption behaviour on a five-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly

agree”. Performed by Cronbach’s α with SPSS, the reliability of the five dimensions of

EMCB scale is as follows: Eco–Buy (two items; α Boycott (two items; 0.80), ¼ 0.74), Eco– α ¼

Recycle (two items; α ¼ 0.64), CSR–Boycott (two items; α 0.85), Pay ¼ –More (two items;

α ¼ 0.85). The Cronbach’s α values indicate the high reliability of most dimensions (αW0.7)

except Recycle. As the low α values are acceptable and common in previous research within

this area (e.g. Arli and Tjiptono, 2014; Lu and Lu, 2010), the dimension Recycle was

remained for the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

Downloaded by University of Florida Love of money H1a–e Spirituality H2a–e Ethically minded Attitude to ethical H3a–e consumer behaviour consumption (a) Eco-Buy Subjective norms to (b) Eco-Boycott ethical consumption H4a–e (c) Recycle (d) CSR-Boycott H5a–e (e) Pay-More Long-term orientation Figure 1. H6a–e The conceptual model Collectivism

The second section is the measurement instrument of cultural values, comprising collectivism EMCB in

and long-term orientation. The scales were adapted from CVSCALE of Yoo et al. (2011) Vietnam

measuring Hofstede’s five dimensions of cultural values at the individual level. Collectivism

and long-term orientation are high in Asian cultures. Collectivists believe that group loyalty

should be encouraged and members should follow the norms, even if the individual goals

suffer. The basic idea of long-term orientation is to give up today’s pleasure for success in the

future. Respondents evaluated the statements of cultural values on a five-point Likert scale

from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. The overall reliability of both collectivism (six

items; α ¼ 0.90) and long-term orientation (three items; α ¼ 0.76) is high.

The third section measures the personal values of consumers which are comprised of

spirituality and love of money. Statements were evaluated on a five-point Likert scale from

“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. Spirituality is the intrinsic view of religiosity which

involves values, ideals and virtues to the religion to which one is committed (Vitell et al.,

2016). This is measured by the scale adapted from the intrinsic religiousness scale of Arli

and Tjiptono (2014). The overall reliability of spirituality is 0.88 (six items). Love of money is

characterised as a consumer’s desire of, value of and aspirations for money (Flurry and

Swimberghe, 2016). The scale for love of money was adapted from Flurry and Swimberghe

(2016). The overall reliability of love of money is 0.75 (three items).

The fourth section is the measurement instrument of the consumer attitude to

ethical consumption and subjective norms. The measurement scales were adapted from

Fielding, McDonald and Louis’ (2008) scale measuring attitude and norms to

environmental activism. For the attitude, respondents rated the statements using five- At 09:28 20 March 2019 (PT)

point semantic scales for the question, “I think that engaging in ethical consumption

behaviour is” (bad/good, foolish/wise, harmful/beneficial and unsatisfying/satisfying).

The overall reliability of attitude is 0.82 ( four items). For the subjective norm, participants

were asked the evaluate five-point semantic scales for three questions, for example: “If I

engaged in ethical consumption behaviour people who are important to me would [ ]” …

(completely disapprove; completely approve); “Most people who are important to me think

that engaging in ethical consumption behaviour is [ ]” (completely undesirable; …

completely desirable); “Most people who are important to me think that [ ] (I should not; I …

should) engage in ethical consumption behaviour”. The overall reliability of attitude is

0.89 (three items). The last section includes the questions to collect demographic

information of the respondents, such as gender, age, education, income, religion,

occupation, to be used in the data analyses.

Downloaded by University of Florida Results Confirmatory factor analyses

Before developing the measurement models for each dimension of EMCB, the exploratory

factor analysis (EFA) was performed on the predictors of the conceptual model to

identify how the items are related and the estimation of factor loadings. The EFA results

indicated the factor structure as expected, so that they were valid for the measurement

model development for further analyses. Then, five measurement models for five

dimensions of EMCB were developed to measure the effects of factors and values

on each dimension of EMCB. The measurement models were tested by CFA before

performing the structural equation modelling (SEM). As reported in Table I, the

results of CFA analyses suggest that four measurement models for Eco–Buy,

Eco–Boycott, CSR–Boycott and Pay–More satisfy the threshold values, indicating good

model fit (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; MacKenzie et al., 2011) and satisfactory reliability

and validity (Hair et al., 2006). However, the AVE and CR values of Recycle did not satisfy

the threshold values (Table I). Thus, the model of Recycle dimension was not included in the following SEM analyses. APJML Eco–Buy Eco–Boycott Recycle CSR–Boycott Pay–More (CR 0.74; ¼ (CR 0.81; ¼ (CR 0.65; ¼ (CR 0.97; ¼ (CR 0.85; ¼ AVE 0.59) ¼ AVE 0.68) ¼ AVE 0.48) ¼ AVE 0.94) ¼ AVE 0.75) ¼ CR AVE CR AVE CR AVE CR AVE CR AVE Love of money 0.76 0.52 0.76 0.52 0.76 0.52 0.76 0.52 0.76 0.52 Spirituality 0.87 0.50 0.87 0.50 0.87 0.50 0.87 0.50 0.87 0.50 Attitude 0.85 0.66 0.85 0.66 0.85 0.66 0.85 0.66 0.85 0.66 Norms 0.90 0.74 0.90 0.74 0.90 0.74 0.90 0.74 0.90 0.74 Long-term orientation 0.76 0.52 0.76 0.52 0.76 0.52 0.76 0.52 0.76 0.52 Collectivism 0.90 0.60 0.90 0.60 0.90 0.60 0.90 0.60 0.90 0.60 Model fit indices χ2/df 2.10 2.12 2.15 2.20 2.06 CFI 0.92 0.92 0.91 0.91 0.92 SRMR 0.06 0.06 0.06 0.06 0.06 RMSEA 0.06 0.06 0.06 0.06 0.06 Table I. Measurement models Note: n ¼ 316 Path analyses

In order to test the relationships between antecedents and EMCB, four SEMs were performed on

each dimension of EMCB, except Recycle. The four dimensions (i.e. ECO–BUY, ECO–Boycott,

CSR–Boycott, Pay–More) were the dependent variables of the four SEMs, respectively. The At 09:28 20 March 2019 (PT)

results of these analyses are reported in Table II.

For Eco–Buy and Pay–More, the SEM result supports three out of six relationships

tested, attitude to ethical consumption, long-term orientation and collectivism. Love of

money is only related to Pay–More, and that is a negative relationship ( β ¼ −0.14, po0.05),

confirming H1e. Love of money and Eco–Buy has no relationship ( β ¼ −0.04, pW0.05), not

supporting H1a. Spirituality has insignificant relationships with both Eco–Buy and Pay–

More, so that H2a and H2e are rejected. Attitude to ethical consumption is significantly

related to purchase behaviours, Eco–Buy ( β ¼ 0.19, po0.05) and Pay–More ( β 0.25, ¼

p o 0.01), supporting H3a and H3e. Long-term orientation also has positive effects on

purchase behaviours, ECO–BUY ( β ¼ 0.16, po0.1) and Pay–More ( β 0.14, 0.1), ¼ p o

supporting H5a and H5e. Collectivism has positive relationships with purchase behaviours,

Eco–Buy ( β ¼ 0.20, po0.05) and Pay–More ( β 0.16, ¼

p o 0.05), supporting H6a and H6e.

Downloaded by University of Florida

For Eco–Boycott and CSR–Boycott, the SEM result only supports two relationships

tested, subjective norms and long-term orientation. All factors – love of money, spirituality

and Attitude – have no relationship with Eco–Boycott and CSR–Boycott, so that all Eco–Buy Eco–Boycott CSR–Boycott Pay–More Standardised Standardised Standardised Standardised estimate p-value estimate p-value estimate p-value estimate p-value Love of money −0.04 0.56 0.09 0.22 − −0.04 0.39 −0.14** 0.04 Spirituality 0.07 0.32 0.08 0.25 −0.01 0.88 0.10 0.11 Attitude 0.19** 0.02 0.02 0.77 −0.03 0.59 0.25*** 0.00 Norms 0.04 0.64 0.16** 0.03 0.17*** 0.00 0.01 0.90 Long-term orientation 0.16* 0.05 0.23*** 0.00 0.14** 0.01 0.14* 0.06 Table II. Collectivism 0.20** 0.01 0.08 0.28 −0.02 0.63 0.16** 0.02 Results of path analyses

Notes: n ¼ 316. *po0.1; **po0.05; ***po0.01

hypotheses H1b, H1d, H2a, H2d, H3b and H3d are not supported. Subjective norm has a EMCB in

positive relationship with boycott behaviours, Eco–Boycott ( β ¼ 0.16, po0.05) and Vietnam

CSR–Boycott ( β ¼ 0.17, po0.01), supporting the hypotheses H4b and H4d. Long-term

orientation is positively related to boycott behaviours, Eco–Boycott ( β ¼ 0.23, po0.01) and CSR–Boycott ( β .

¼ 0.14, p o 0.05), supporting the hypotheses H5b and H5d ANOVA analyses

Literature suggests that various demographic descriptors such as age, gender, income

and educational level appear to be related to consumer ethics (Chowdhury and Fernando,

2013; Vitell, 2003; Chen and Tang, 2013). Thus, in order to understand the roles of

demographics on consumer ethics, this study compares the impact of demographic

information on each dimension of ethically minded behaviour of the Vietnamese

consumers. The ANOVA analyses were conducted with five demographic groups, namely,

gender, age, income, education and job level, following the procedure used in previous

studies in the consumer ethics field (e.g. Lu and Lu, 2010). The results of those ANOVA

analyses are shown in Table III.

Firstly, for the gender, there is no difference between male and female respondents in

their engagement with ethical consumption behaviour. The F-values for all five

dimensions are not statistically significant. Second, the age of respondents was grouped

into three age ranges, under 30, 30–40 and over 40. Results indicate that age groups are

significantly different in Eco–Buy, Eco–Boycott and Pay–More dimensions. Consumers

over 40 are more likely to engage with these three ethical behaviour dimensions than At 09:28 20 March 2019 (PT)

young consumers who are less than 30. Consumers over 40 are also more likely to boycott

the products due to environmental issues than consumer group from 30 to 40. Third, there

is a statistically significant impact of income on the four dimensions of ethical

consumption, except CSR–Boycott. Results show that the high-income group tends to

engage with ethical behaviours more than the low-income group. Fourth, similar to the

gender group, the education level (bachelor degree vs postgraduate degree) also has no

significant impact on EMCB. Finally, in terms of the job-level group, ANOVA results

present a greater likelihood of consumers who are holding management positions to

attend the dimensions of Eco–Buy, Eco–Boycott and Recycle. Especially, the results of

ANOVA analyses indicate that the demographic groups have no effect on CSR–Boycott of

the Vietnamese consumers included in this study.

Downloaded by University of Florida Discussion

The results of the SEM approach reveal the effects of examined variables on the dimensions

of EMCB, except Recycle. The low reliability and the exclusion of Recycle reflect the

unpopularity of recycling concepts and recycled products in Vietnam (de Koning et al.,

2015). Some consumers might consider that the recycled or reusable products are

unavailable in the marketplace or are unsure about the concept.

Regarding personal values, two constructs which have been widely proven to have an

impact on ethical beliefs were analysed within this study, but the analyses lead to

insignificant results. It is understandable that love of money only has a negative

relationship with Pay–More. This result can be compared with the previous research on love

of money and a similar meaning construct of materialism. Interestingly, this is inconsistent

with previous studies (e.g. Arli and Tjiptono, 2014; Flurry and Swimberghe, 2016; Lu and

Lu, 2010; Muncy and Eastman, 1998), which support the negative impact of love of money

and materialism on ethical beliefs. This could be because, in Vietnam, eco-friendly product

purchase is strongly connected to health issues, and there is a general distrust towards

business and government actors (de Koning et al., 2015). Thus, eco-friendly products are

considered as good and healthy products. Because of the concerns for health and living c 0 APJML o 3 h U L st W W o 0 P 4 H re O o M * * 8 * * 5 9 8 2 y– .0 .9 .2 a 0 .7 .2 0 1 P n 3 3 5 8 6 3 7 2 3 6 1 2 4 3 8 ea e¼ .0 .0 ¼ ¼ ¼ .9 .1 .2 ¼ .9 .1 .1 e .1 .0 e .1 .0 .9 M lu 4 4 e 3 4 4 e 3 4 4 lu 4 4 4 4 3 a lu lu a lu a -v a a -v -v F -v -v F F F F 1 .0 st c 0 o o P h o p tt * co * * y o 1 4 5 2 6 ; 5 B .0 .8 .7 .1 .4 – 0 1 2 0 1 .0 0 R n 4 1 S ea e¼ 1 2 e¼ 4 5 9 e¼ 7 7 2 e¼ 3 0 e¼ 0 8 2 o C .3 .3 .2 .3 .4 .1 .3 .4 .3 .3 .4 .2 .2 M lu lu lu lu 4 p a 4 4 a 4 4 4 a 4 4 3 a 4 4 lu 4 a 4 * * -v -v -v -v -v ; F F F F F .1 0 o st c L E p o o * P h W W H M re. u cle 2 7 * * 7 * ced .1 .7 2 .1 * 8 ro ecy 0 2 .5 2 At 09:28 20 March 2019 (PT) .9 p R n 3 2 2 ¼ 3 g ea e¼ 5 8 8 3 1 3 0 7 ¼ 2 0 - 7 0 8 .8 .8 e .7 .9 .0 .7 .9 .9 e .9 .8 F .9 .7 .8 M lu e¼ lu 3 3 a 3 3 lu 3 3 4 3 3 3 3 e¼ 3 3 a lu a -v a -v lu a testin F -v F v c F F v o h c 0 0 st o 3 3 o h U U L p st E W W W o 0 0 ey P 4 4 H W rk tt U O M u co T y * * e o 7 * 1 * B th .7 * * .4 7 1 2 e * .7 0 .5 g co– n * 0 4 3 E 4 2 lu 0 6 3 1 3 2 6 2 0 1 0 sin ea e¼ .9 .8 a .0 ¼ 0 .7 .0 .1 .7 .9 .0 e .8 .9 ¼ .0 .7 .9 u M lu 3 3 -v 3 4 4 e¼ 3 3 4 lu 3 3 e 4 3 3 5 a F 1 lu a lu .0 -v ¼ a -v a 0

Downloaded by University of Florida F -v F -v F F o p t c 0 a o 3 h U L re a st E W W o 0 H P 4 W ces y O M u B * 9 * * * * 0 * ifferen .1 7 4 .0 7 co– 0 .1 .1 2 .1 d E t n 3 9 4 4 1 1 8 7 6 7 0 6 5 1 0 6 n ea e¼ .8 .9 .8 .9 .0 ¼ ¼ .7 .9 .0 e .9 .8 .0 .8 .8 M lu 3 3 e¼ 3 3 4 e 3 3 4 lu 3 3 e¼ 4 3 3 a lu lu a lu ifica n -v a a -v a F -v -v F -v sig F F F ll ) ) A ) (E . 0 ) ) (P 6 3 ) ) ) 1 0 D (L ) te ers 3 Table III. ) ) ) (U 0 4 N (H m (M (U a n ) Results of ANOVA ) rk (F 0 4 (O (M m n u o n¼ 3 (V 5 r (U 0 1 0 d tio ers w (O : analyses for er (M le 4 e m 3 tio ra a g s d a 0 0 elo p a demographics le er m er e ca d 4 er d 3 er u n ers te en a ch stg em g n 1– v co n 5– v d a o ccu a ffice th o G M F A U 3 O In U 1 O E B P O M O O N

environment and the distrust towards business, Vietnamese consumers are willing to EMCB in

engage in eco-friendly purchase regardless of the love of money. Besides this, there is no Vietnam

relationship between spirituality and EMCB dimensions. The absence of an influential role

of spirituality in the present study is in contrast with prior research on spirituality and

ethical beliefs (e.g. Arli and Tjiptono, 2014; Vitell et al., 2016). Vietnam is a multi-religion

culture in which many Vietnamese are self-considered as being non-religious, for example,

for 47.5 per cent of respondents in the present study.

Attitude and subjective norms examined in this study are the attitudes to ethical

consumption and subjective norm in relation to ethical consumption. The interesting fact is

that personal attitude will lead to ethical purchase behaviour, whereas subjective norm will

lead to boycotting behaviour (or maybe boycotting campaigns). This also reflects the

anxiety and distrust of Vietnamese consumers towards unethical businesses. Past studies

conclude that both attitude and subjective norm would link to ethical behaviour, from the

perspective of the theory of planned behaviour (e.g. Casidy et al., 2016; Fielding, McDonald

and Louis, 2008); but when we look into each dimension of the behaviour in the present

study, a different result was found.

The findings assert the effects of cultural values of collectivism and long-term orientation

on the likelihood of ethical consumer behaviour. Long-term orientation is positively related to

all the four dimensions of ethically minded behaviour, and collectivism is positively associated

with Eco–Buy and PAY–More. Although there is a lack of research on the relationships

between such cultural values and ethical consumer behaviour, this finding is consistent with

the previous studies as asserting the impact of collectivism and long-term orientation on At 09:28 20 March 2019 (PT)

environmental attitude (e.g. Leonidou et al., 2010). Consumers who are collectivists or long-

term orientated would be more likely to conduct ethical purchase behaviour. They tend to

think and act for others and for the coming generations, so that they are willing to engage in

such ethical behaviours. Regarding the impact of long-term orientation and collectivism on

ethical consumption, it can be predicted that consumer ethics will soon be popular in Asian

countries, as collectivism and long-term orientation are the main cultural values in this region.

For example, even though people in Vietnam have limited knowledge of sustainable

consumption, their awareness of protecting the planet is generally high (de Koning et al., 2015).

The ANOVA analyses compared the tendency of consumers to engage in ethical

behaviour from different demographic groups. Inconsistent with other studies (e.g. Lu and

Lu, 2010), in the present study, gender and education have no effect on EMCB. For the

education level, the reason might be because the sample only reflects groups of holders of

bachelor and postgraduate degrees, which are all at a high educational level. The group of

Downloaded by University of Florida

people who do not hold a bachelor degree only accounts for 3.2 per cent, which is too low for

the ANOVA analysis. On the other hand, other elements such as age, income and job level

(managers and office workers) significantly relate to the EMCB. In particular, the CSR–

Boycott dimension has no significant difference through all demographic groups. Again,

this might be because there is an unclear definition in Vietnam about corporate social

responsibility and there is no official assessment of social responsibility in Vietnamese

firms, so that the perceptions in relation to these issues are ambiguous. Conclusions

This study explores the EMCB in Vietnam, by conducting an extensive investigation based

on cultural and personal factors and demographic information. Most of the previous

research in this area has been conducted on Western countries and has mostly focussed on

analysing ethical beliefs and judgements. As the first study to fully investigate dimensions

of consumer’s ethical behaviour, particularly in Vietnam, this study therefore significantly

contributes to the body of knowledge regarding consumer ethics in Asia. Moreover, this is

one of the first studies that explores the EMCB based on five dimensions that are relevant to APJML

wider social considerations, as compared to previous studies focussing on extensively

specific aspects (e.g. green purchase or digital piracy). This could provide initial findings to

understand how the popular factors which have been concluded as relating to ethical beliefs

have impacts on different aspects of ethical consumption behaviour. In addition, evidence

from the research adds validation to the EMCB scale.

The findings provide several thought-provoking points in the Vietnamese consumer

landscape. For example, spirituality has no relationship with ethical consumption in the

present study, and this finding is inconsistent with all the other research in this area; and

attitude is related to ethical purchase, but subjective norm is associated with boycotting

behaviours. This suggests more understanding and awareness of the reality for

practitioners in Vietnam is needed, and such topics should be further investigated to

provide better insights into the questions from studies within this cultural context.

As a result, this study could be of great benefit for policy makers and practitioners in

Vietnam in understanding how personal and cultural factors affect the ethical consumption

behaviour of Vietnamese consumers. It is especially important to global companies which

intend to enter the Vietnamese market in the near future, to understand the insights into the

consumer ethics context in this local market. Practitioners may also note that the results

highlight differences between purchasing behaviours and boycotting behaviours, as well as

perceptions regarding corporate social responsibility and ecology. Even though these

concepts are quite new in Vietnam, local consumers show considerable concern about these

issues, as they are well aware of the environmental and health issues. Vietnam is an emerging

and sizable market, so that these findings could provide a significant understanding of the At 09:28 20 March 2019 (PT)

local market practices. Furthermore, it provides practitioners in Vietnam with a measurement

instrument that can be used to profile and segment consumers.

This study has some limitations which suggest potential areas for future research. First,

given the novel nature of the EMCB scale, this study only focussed on the improved

understanding of predictors of EMCB dimensions, and was not concerned with the underlying

decision-making processes. Future research across contexts or with longitudinal design is

warranted to examine the processes explaining EMCB, as well as to assess more appropriately

the causal relationships among antecedents within the processes. Second, this analysis was

only conducted in Vietnam, which may limit the scope for generalisation. Future research can

extend to other countries in order to understand the ethically minded behaviour of consumers

in other cultures, particularly within the developing world, where blanket generalisations are

not always found to apply, as in the present study. Third, despite an extensive analysis, only

popular factors have been investigated within the limited space of this study. Therefore,

Downloaded by University of Florida

future research would need to examine all Hofstede’s five dimensions of cultural values to

provide a general landscape of how cultural values influence ethical behaviours. Fourth,

although the data were collected with a non-student sample and are relatively diversified,

future research would need to extend the scope of the sample collected to capture information

from other demographic groups (e.g. people have not attended university). Finally, to capture

deeper insights into consumer ethics and explain the present findings, qualitative

investigations could be incorporated into such studies. References

Ajzen, I. (1991), “The theory of planned behavior”, Organizational Behavior & Human Decision

Processes, Vol. 50 No. 2, pp. 179-211.

Allport, G.W. and Ross, J.M. (1967), “Personal religious orientation and prejudice”, Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 5 No. 4, pp. 432-443.

Arli, D. and Tjiptono, F. (2014), “The end of religion? Examining the role of religiousness, materialism,

and long-term orientation on consumer ethics in Indonesia”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 123 No. 3, pp. 385-400.

Arli, D., Tjiptono, F. and Rebecca, P. (2015), “The impact of moral equity, relativism and attitude on EMCB in

individuals’ digital piracy behaviour in a developing country”, Marketing Intelligence & Vietnam

Planning, Vol. 33 No. 3, pp. 348-365.

Auger, P., Devinney, T. and Louviere, J. (2007), “Using best–worst scaling methodology to investigate

consumer ethical beliefs across countries”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 70 No. 3, pp. 299-326.

Bakar, A., Lee, R. and Hashim, N.H. (2013), “Parsing religiosity, guilt and materialism on consumer

ethics”, Journal of Islamic Marketing, Vol. 4 No. 3, pp. 232-244.

Bartels, J. and Onwezen, M.C. (2014), “Consumers’ willingness to buy products with environmental and

ethical claims: the roles of social representations and social identity”, International Journal of

Consumer Studies, Vol. 38 No. 1, pp. 82-89.

Carrigan, M. and Attalla, A. (2001), “The myth of the ethical consumer – do ethics matter in purchase

behaviour?”, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 18 No. 7, pp. 560-578.

Carrigan, M., Moraes, C. and Leek, S. (2011), “Fostering responsible communities: a community

social marketing approach to sustainable living”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 100 No. 3, pp. 515-534.

Carrington, M.J., Neville, B. and Whitwell, G. (2010), “Why ethical consumers don’t walk their talk:

towards a framework for understanding the gap between the ethical purchase intentions and

actual buying behaviour of ethically minded consumers”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 97 No. 1, pp. 139-158.

Carrington, M.J., Neville, B. and Whitwell, G. (2014), “Lost in translation: exploring the ethical consumer

intention–behavior gap”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 67 No. 1, pp. 2759-2767.

Carrington, M.J., Zwick, D. and Neville, B. (2016), “The ideology of the ethical consumption gap”, At 09:28 20 March 2019 (PT)

Marketing Theory, Vol. 16 No. 1, pp. 21-38.

Caruana, R., Carrington, M. and Chatzidakis, A. (2016), “ ‘Beyond the attitude–behaviour gap: novel

perspectives in consumer ethics’: introduction to the thematic symposium”, Journal of Business

Ethics, Vol. 136 No. 2, pp. 215-218.

Casidy, R., Phau, I. and Lwin, M. (2016), “The role of religious leaders on digital piracy attitude and

intention”, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Vol. 32, Supplement C, pp. 244-252.

Chan, A., Wong, S. and Leung, P. (1998), “Ethical beliefs of Chinese consumers in Hong Kong”, Journal

of Business Ethics, Vol. 17 No. 11, pp. 1163-1170.

Chen, Y.-J. and Tang, T.L.-P. (2013), “The bright and dark sides of religiosity among university

students: do gender, college major, and income matter?”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 115 No. 3, pp. 531-553.

Chowdhury, R.M.M.I. and Fernando, M. (2013), “The role of spiritual well-being and materialism in

Downloaded by University of Florida

determining consumers’ ethical beliefs: an empirical study with Australian consumers”, Journal

of Business Ethics, Vol. 113 No. 1, pp. 61-79.

de Koning, J.I.J.C., Crul, M.R.M., Wever, R. and Brezet, J.C. (2015), “Sustainable consumption in Vietnam:

an explorative study among the urban middle class”, International Journal of Consumer Studies, Vol. 39 No. 6, pp. 608-618.

De Pelsmacker, P., Driesen, L. and Rayp, G. (2005), “Do consumers care about ethics? Willingness to

pay for fair-trade coffee”, Journal of Consumer Affairs, Vol. 39 No. 2, pp. 363-385.

Elias, R.Z. (2013), “Business students’ love of money and some psychological determinants”,

International Journal of Business & Public Administration, Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 80-89.

Euromonitor (2017), “Ethical consumer: mindful consumerism”, Euromonitor.

Fielding, K.S., McDonald, R. and Louis, W.R. (2008), “Theory of planned behaviour, identity and

intentions to engage in environmental activism”, Journal of Environmental Psychology, Vol. 28 No. 4, pp. 318-326.

Fielding, K.S., Terry, D.J., Masser, B.M. and Hogg, M.A. (2008), “Integrating social identity theory and

the theory of planned behaviour to explain decisions to engage in sustainable agricultural

practices”, British Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 47 No. 1, pp. 23-48. APJML

Fishbein, M. and Ajzen, I. (1975), Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory

and Research, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA.

Fishbein, M. and Ajzen, I. (2010), Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach,

Psychology Press, New York, NY.

Flurry, L.A. and Swimberghe, K. (2016), “Consumer ethics of adolescents”, Journal of Marketing Theory

and Practice, Vol. 24 No. 1, pp. 91-108.

Fornell, C. and Larcker, D.F. (1981), “Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable

variables and measurement error”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 39-50.

Fukukawa, K. and Ennew, C. (2010), “What we believe is not always what we do: an empirical

investigation into ethically questionable behavior in consumption”, Journal of Business Ethics,

Vol. 91, Supplement 1, pp. 49-60.

Grunert, S.C. and Juhl, H.J. (1995), “Values, environmental attitudes, and buying of organic foods”,

Journal of Economic Psychology, Vol. 16 No. 1, pp. 39-62.

Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., Anderson, R.E. and Tatham, R.L. (2006), Multivariate Data Analysis,

6th ed., Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Hofstede, G.H. (1984), Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-related Values,

abridged ed., Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, CA.

Hofstede, G.H. (2011), “Dimensionalizing cultures: the Hofstede model in context”, Online Readings in

Psychology and Culture, Vol. 2 No. 1.

Hughner, R.S., McDonagh, P., Prothero, A., Shultz, II, C.J. and Stanton, J. (2007), “Who are organic food

consumers? A compilation and review of why people purchase organic food”, Journal of At 09:28 20 March 2019 (PT)

Consumer Behaviour, Vol. 6 Nos 2/3, pp. 94-110.

Hunt, S.D. and Vitell, S.J. (1986), “A general theory of marketing ethics”, Journal of Macromarketing, Vol. 6 No. 1, pp. 5-16.

Hunt, S.D. and Vitell, S.J. (1993), “The general theory of marketing ethics: a retrospective and

revision”, in Smith, N.C. and Quelch, J.A. (Eds), Ethics in Marketing, JSTOR, Irwin, Homewood, IL, pp. 775-784.

Hunt, S.D. and Vitell, S.J. (2006), “The general theory of marketing ethics: a revision and three

questions”, Journal of Macromarketing, Vol. 26 No. 2, pp. 143-153.

Johe, M.H. and Bhullar, N. (2016), “To buy or not to buy: the roles of self-identity, attitudes, perceived

behavioral control and norms in organic consumerism”, Ecological Economics, Vol. 128, Supplement C, pp. 99-105.

Downloaded by University of Florida

Leonidou, L.C., Leonidou, C.N. and Kvasova, O. (2010), “Antecedents and outcomes of consumer

environmentally friendly attitudes and behaviour”, Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 26 Nos 13/14, pp. 1319-1344.

Lu, L.-C. and Lu, C.-J. (2010), “Moral philosophy, materialism, and consumer ethics: an exploratory

study in Indonesia”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 94 No. 2, pp. 193-210.

MacKenzie, S.B., Podsakoff, P.M. and Podsakoff, N.P. (2011), “Construct measurement and validation

procedures in MIS and behavioral research: integrating new and existing techniques”, MIS

Quarterly, Vol. 35 No. 2, pp. 293-334.

Moon, Y.S. and Franke, G.R. (2000), “Cultural influences on agency practitioners’ ethical perceptions: a

comparison of Korea and the US”, Journal of Advertising, Vol. 29 No. 1, pp. 51-65.

Muncy, J.A. and Eastman, J.K. (1998), “Materialism and consumer ethics: an exploratory study”,

Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 17 No. 2, pp. 137-145.

Muncy, J.A. and Vitell, S.J. (1992), “Consumer ethics: an investigation of the ethical beliefs of the final

consumer”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 24 No. 4, pp. 297-311.

Nevins, J.L., Bearden, W.O. and Money, B. (2007), “Ethical values and long-term orientation”, Journal of

Business Ethics, Vol. 71 No. 3, pp. 261-274.

Nielsen (2015a), “The sustainability imperative: new insights on consumer expectations”, available at: EMCB in

www.nielsen.com/content/dam/nielsenglobal/dk/docs/global-sustainability-report-oct-2015.pdf Vietnam (accessed 20 November 2017).

Nielsen (2015b), “Sustainability influences purchase intent of Vietnamese consumers”, available at:

www.nielsen.com/content/dam/nielsenglobal/vn/docs/PR_EN/Vietnam_CSR%20release_EN.

pdf (accessed 20 November 2017).

Olsen, S.O. and Grunert, K.G. (2010), “The role of satisfaction, norms and conflict in families’ eating

behaviour”, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 44 Nos 7/8, pp. 1165-1181.

Patwardhan, A.M., Keith, M.E. and Vitell, S.J. (2012), “Religiosity, attitude toward business, and ethical

beliefs: Hispanic consumers in the United States”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 110 No. 1, pp. 61-70.

Pepper, M., Jackson, T. and Uzzell, D. (2009), “An examination of the values that motivate socially

conscious and frugal consumer behaviours”, International Journal of Consumer Studies, Vol. 33 No. 2, pp. 126-136.

Polonsky, M.J., Brito, P.Q., Pinto, J. and Higgs-Kleyn, N. (2001), “Consumer ethics in the European Union: a

comparison of northern and southern views”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 31 No. 2, pp. 117-130.

Poortinga, W., Steg, L. and Vlek, C. (2004), “Values, environmental concern, and environmental behavior:

a study into household energy use”, Environment and Behavior, Vol. 36 No. 1, pp. 70-93.

Rawwas, M.Y.A. (1996), “Consumer ethics: an empirical investigation of the ethical beliefs of Austrian

consumers”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 15 No. 9, pp. 1009-1019.

Roberts, J.A. (1993), “Sex differences in socially responsible consumers’ behavior”, Psychological

Reports, Vol. 73 No. 1, pp. 139-148. Roberts, J.A. (1995), At 09:28 20 March 2019 (PT)

“Profiling levels of socially responsible consumer behavior: a cluster analytic approach

and its implications for marketing”, Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, Vol. 3 No. 4, pp. 97-117.

Roberts, J.H. and Lilien, G.L. (1993), “Explanatory and predictive models of consumer behavior”, in

Eliashberg, J. and Lilien, G.L. (Eds), Handbooks in Operations Research and Management Science, Vol. 5, pp. 27-82.

Salazar, H.A., Oerlemans, L. and van Stroe-Biezen, S. (2013), “Social influence on sustainable

consumption: evidence from a behavioural experiment”, International Journal of Consumer

Studies, Vol. 37 No. 2, pp. 172-180.

Schlegelmilch, B.B., Bohlen, G.M. and Diamantopoulos, A. (1996), “The link between green purchasing

decisions and measures of environmental consciousness”, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 30 No. 5, pp. 35-55.

Shaw, D., Shiu, E. and Clarke, I. (2000), “The contribution of ethical obligation and self-identity to the

theory of planned behaviour: an exploration of ethical consumers”, Journal of Marketing

Downloaded by University of Florida

Management, Vol. 16 No. 8, pp. 879-894.

Shultz, C.J. II (2012), “Vietnam: political economy, marketing system”, Journal of Macromarketing, Vol. 32 No. 1, pp. 7-17.

Singhapakdi, A., Vitell, S., Lee, D.-J., Nisius, A. and Yu, G. (2013), “The influence of love of money and

religiosity on ethical decision-making in marketing”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 114 No. 1, pp. 183-191.

Sudbury-Riley, L. and Kohlbacher, F. (2016), “Ethically minded consumer behavior: scale review,

development, and validation”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 69 No. 8, pp. 2697-2710.

Tang, T.L.-P. (2007), “Income and quality of life: does the love of money make a difference?”, Journal of

Business Ethics, Vol. 72 No. 4, pp. 375-393.

Tang, T.L.-P. and Liu, H. (2012), “Love of money and unethical behavior intention: does an Authentic

Supervisor’s Personal Integrity and Character (ASPIRE) make a difference?”, Journal of Business

Ethics, Vol. 107 No. 3, pp. 295-312.

Tantawi, P.I., O’shaughnessy, N.J., Gad, K.A. and Ragheb, M.A.S. (2009), “Green consciousness of

consumers in a developing country: a study of Egyptian consumers”, Contemporary

Management Research, Vol. 5 No. 1. APJML

Tsui, J. and Windsor, C. (2001), “Some cross-cultural evidence on ethical reasoning”, Journal of Business

Ethics, Vol. 31 No. 2, pp. 143-150.

Vermeir, I. and Verbeke, W. (2006), “Sustainable food consumption: exploring the consumer ‘Attitude–

Behavioral Intention’ gap”, Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, Vol. 19 No. 2, pp. 169-194.

Vermeir, I. and Verbeke, W. (2008), “Sustainable food consumption among young adults in Belgium:

theory of planned behaviour and the role of confidence and values”, Ecological Economics, Vol. 64 No. 3, pp. 542-553.

Vitell, S.J. (2003), “Consumer ethics research: review, synthesis and suggestions for the future”, Journal

of Business Ethics, Vol. 43 Nos 1/2, pp. 33-47.

Vitell, S.J. and Muncy, J. (1992), “Consumer ethics: an empirical investigation of factors influencing

ethical judgments of the final consumer”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 11 No. 8, pp. 585-597.

Vitell, S.J. and Muncy, J. (2005), “The Muncy–Vitell Consumer Ethics Scale: a modification and

application”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 62 No. 3, pp. 267-275.

Vitell, S.J., Paolillo, J. and Singh, J. (2006), “The role of money and religiosity in determining consumers’

ethical beliefs”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 64 No. 2, pp. 117-124.

Vitell, S.J., Paolillo, J.G.P. and Singh, J.J. (2005), “Religiosity and consumer ethics”, Journal of Business

Ethics, Vol. 57 No. 2, pp. 175-181.

Vitell, S.J., Singh, J.J. and Paolillo, J. (2007), “Consumers’ ethical beliefs: the roles of money, religiosity

and attitude toward business”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 73 No. 4, pp. 369-379.

Vitell, S.J., Bing, M.N., Davison, H.K., Ammeter, A.P., Garner, B.L. and Novicevic, M.M. (2009),

“Religiosity and moral identity: the mediating role of self-control”, Journal of Business Ethics, At 09:28 20 March 2019 (PT) Vol. 88 No. 4, pp. 601-613.

Vitell, S.J., King, R.A., Howie, K., Toti, J.-f., Albert, L., Hidalgo, E.R. and Yacout, O. (2016), “Spirituality,

moral identity, and consumer ethics: a multi-cultural study”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 139 No. 1, pp. 147-160.

World Bank (2017), “Country profile: Vietnam”, available at: http://databank.worldbank.org/data/

Views/Reports/ReportWidgetCustom.aspx?Report_Name=CountryProfile&Id=b450fd57&

tbar y&dd y&inf n&zm n&country = = = =

=VNM (accessed 15 December 2017).

Yeon Kim, H. and Chung, J.E. (2011), “Consumer purchase intention for organic personal care

products”, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 28 No. 1, pp. 40-47.

Yoo, B., Donthu, N. and Lenartowicz, T. (2011), “Measuring Hofstede’s five dimensions of cultural

values at the individual level: development and validation of CVSCALE”, Journal of

International Consumer Marketing, Vol. 23 Nos 3-4, pp. 193-210.

Downloaded by University of Florida Further reading

Arli, D. and Pekerti, A. (2016), “Investigating the influence of religion, ethical ideologies and

generational cohorts toward consumer ethics: which one matters?”, Social Responsibility Journal, Vol. 12 No. 4, pp. 770-785.

Jose, P.E. (2013), Doing Statistical Mediation and Moderation, Guilford Publications, New York, NY.

Steenhaut, S. and van Kenhove, P. (2006), “An empirical investigation of the relationships among a

consumer’s personal values, ethical ideology and ethical beliefs”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 64 No. 2, pp. 137-155. Corresponding author

Tri D. Le can be contacted at: ldmtri@hcmiu.edu.vn

For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website:

www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm

Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com