Preview text:

GOOD CHARTS GOOD CHARTS SCOTT BERINATO The HBR Guide to Making Smarter, More Persuasive Data Visualizations HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW PRESS Boston, Massachusetts

HBR Press Quantity Sales Discounts

Harvard Business Review Press titles are available at significant quantity discounts.

Special editions, including books with corporate logos, customized covers, and letters

from the company or CEO printed in the front matter, as well as excerpts of existing

books, can also be created in large quantities for special needs.

For details and discount information for both print and ebook formats,

contact booksales@harvardbusiness.org, tel. 800-988-0886, or www.hbr.org/bulksales.

Copyright 2016 Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation All rights reserved

Find more digital content or join the discussion on hbr.org.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or

transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or

otherwise), without the prior permission of the publisher. Requests for permission should be directed

to permissions@hbsp.harvard.edu, or mailed to Permissions, Harvard Business School Publishing,

60 Harvard Way, Boston, Massachusetts 02163.

The web addresses referenced in this book were live and correct at the time of the book’s publication but may be subject to change.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Berinato, Scott, author.

Title: Good charts : the HBR guide to making smarter, more persuasive data visualizations / by Scott Berinato.

Description: Boston, Massachusetts : Harvard Business Review Press, [2016]

Identifiers: LCCN 2015046676 (print) | LCCN 2016002607 (ebook) | ISBN 9781633690707 (paperback) | ISBN 9781633690714 ( )

Subjects: LCSH: Business presentations—Charts, diagrams, etc. | Visual communication. |

Communication in management. | BISAC: BUSINESS & ECONOMICS / Business Communication /

Meetings & Presentations. | BUSINESS & ECONOMICS / Business Communication / General. |

BUSINESS & ECONOMICS / Strategic Planning.

Classification: LCC HF5718.22 .B475 2016 (print) | LCC HF5718.22 (ebook) | DDC 658.4/52—dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015046676 ISBN: 978-1-63369-070-7 eISBN: 978-1-63369-071-4 M S E CONTENTS Part Two INTRODUCTION 1 CREATE

A NEW LANGUAGE AND A NECESSARY CRAFT Chapter 3 TWO QUESTIONS ➔ FOUR TYPES 53 Part One

A SIMPLE TYPOLOGY FOR CHART MAKING UNDERSTAND Idea Illustration 58 Idea Generation 59 Chapter 1 Visual Discovery 61 Everyday Dataviz 66 A BRIEF HISTORY OF DATAVIZ 17

THE ART AND SCIENCE THAT BUILT A NEW LANGUAGE Chapter 4 BETTER CHARTS IN A COUPLE Chapter 2 WHEN A CHART HITS OUR EYES OF HOURS 73 33 A SIMPLE FRAMEWORK SOME SCIENCE OF HOW WE SEE Prep 75 Talk and Listen 77 Sketch 82 Prototype 89 Part Three Part Four REFINE PRESENT AND PRACTICE Chapter 5 Chapter 8 REFINE TO IMPRESS 109 PRESENT TO PERSUADE 177

GETTING TO THE “FEELING BEHIND OUR EYES” GETTING A GOOD CHART TO THEIR EYES AND INTO THEIR MINDS Chapter 6 REFINE TO PERSUADE Chapter 9 133

THREE STEPS TO MORE-PERSUASIVE CHARTS VISUAL CRIT 209

HOW TO PRACTICE LOOKING AT (AND MAKING) Chapter 7 GOOD CHARTS PERSUASION OR MANIPULATION? 153 THE BLURRED EDGE OF TRUTH CONCLUSION 223 KEEP GOING Glossary 227 Notes 233 Index 247 Acknowledgments 253 About the Author 255 VIII | CONTENTS INTRODUCTION A NEW LANGUAGE AND A NECESSARY CRAFT

“. . . for there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” —Shakespeare | 1

IN A WORLD governed by data, in knowledge economies where ideas are currency, visu-

alization has emerged as our shared language. Charts, graphs, maps, diagrams—even

animated GIFs and emojis—all transcend text, spoken languages, and cultures to help

people understand one another and connect. This visual language is used everywhere in the world, every day.

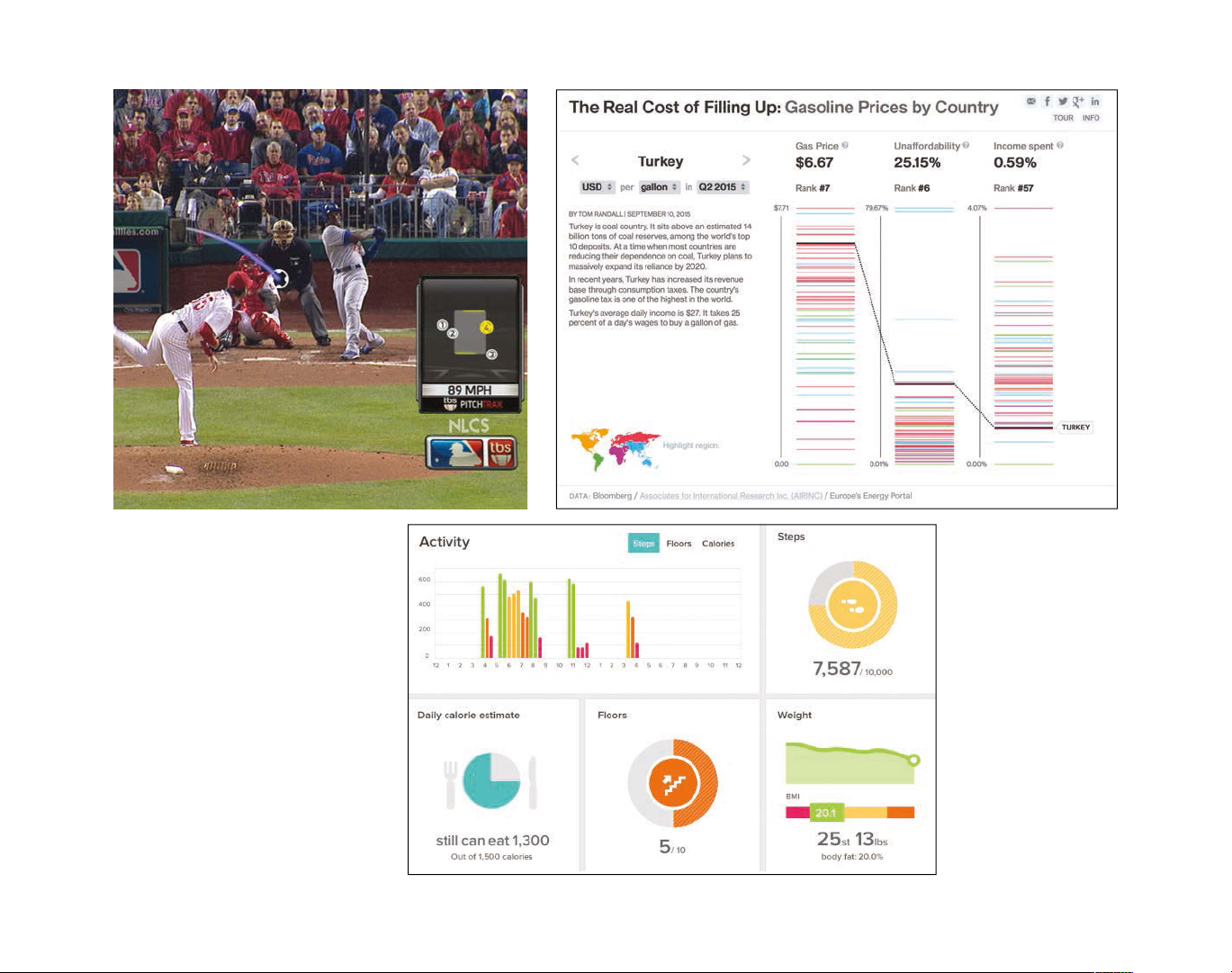

Dashboard maps in cars help commuters avoid the thick red lines of heavy traffic and

find the kelly green routes where traffic is light. Weather apps use iconography and

rolling trend lines to make forecasts accessible at a glance. Fitness-tracking apps default

to simple charts that show steps taken, sleep patterns, eating habits, and more. Utility

company bills include charts so consumers can see how their energy use compares with

their neighbors’. Newspapers, magazines, and websites all use visualization to attract

audiences and tell complex stories. The social web teems with data visualizations—some

practical, some terrible, some rich with insight, some simply fun to look at—all vying to

go viral. Sports broadcasts superimpose visual data on live action, from first-down lines

on a football field to more sophisticated pitch-sequence diagrams and spray charts that

show a baseball’s trajectory and expose pitching and hitting trends.

You may not notice all the ways in which dataviz has seeped into your daily life, but you

have come to expect it. Even if you think you can’t speak this language, you hear it and understand it every day.

It’s time to learn to speak it, too. Just as the consumerization of technology adoption

and the widespread use of social media changed business, the ubiquity of dataviz in our

lives is driving demand for good charts in unit meetings, sales presentations, customer

research reports, performance reviews, entrepreneurs’ pitches, and all the way up to

the boardroom.1 Increasingly, when an executive sees a line chart that’s been spit out

of Excel and pasted into a presentation, she wonders why it doesn’t look more like the

simple, beautiful charts on her fitness-tracker app. When a manager spends time trying

to parse pie charts and donut charts and multiple trend lines on a company dashboard,

he wonders why they don’t look as nice or feel as easily understood as his weather app. 2 | INTRODUCTION Data visualization is everywhere, from live sports to the news to fitness apps.

A NEW LANGUAGE AND A NECESSARY CRAFT | 3 BUSINESS’S NEW LINGUA FRANCA

Speaking this new language requires us to adopt a new way of thinking—visual thinking—

that is evolving quickly in business. Making good charts isn’t a special or a nice-to-have

skill anymore; it’s a must-have skill. If all you ever do is click a button in Excel or Google

Charts to generate a basic chart from some data set, you can be sure that some of your

colleagues are doing more and getting noticed for it. No company today would hire a

manager who can’t negotiate the basics of a spreadsheet; no company tomorrow will hire

one who can’t think visually and produce good charts.

Dataviz has become an imperative for competitive companies. Those that don’t have a

critical mass of managers capable of thinking visually will lag behind the ones that do.

Vincent Lebunetel is the vice president of innovation at Carlson Wagonlit Travel, which

invests in hiring and training information designers. He says that business managers

and leaders who can’t create clear visualizations are just less valuable: “If you’re not able

to make your message simple and accessible, you probably don’t own your topic well

enough. And visualization is probably the best way to help people grasp information efficiently.”

After a group at Accenture Technology Labs produced visualizations of NBA team

shooting patterns that went viral, its consultants started asking the group for help

producing charts that would produce a similar visceral reaction in their own clients.2 So

Accenture built an online and in-person “visual literacy curriculum” for them. The VLC

has been so effective internally that Accenture is making the curriculum a client service

and developing a visualization career track for its consultants.

Daryl Morey, the general manager of the NBA’s Houston Rockets, puts it plainly:

“Everyone in our business knows they need to visualize data, but it’s easy to do it poorly.

We invest in it. We’re excited if we can use it right while they use it wrong.”

So what’s “right,” and what’s “wrong”? 4 | INTRODUCTION WHAT’S A GOOD CHART?

The rise of visualization has generated numerous opinions about how to do it right—and

harsh judgment of charts that get it wrong. Missing from most attempts to establish rules

are an overarching view of what it means to think visually and a framework and repeat-

able process for constructing good charts.

To build fluency in this new language, to tap into this vehicle for professional growth,

and to give organizations a competitive edge, you first need to recognize a good chart when you see one.

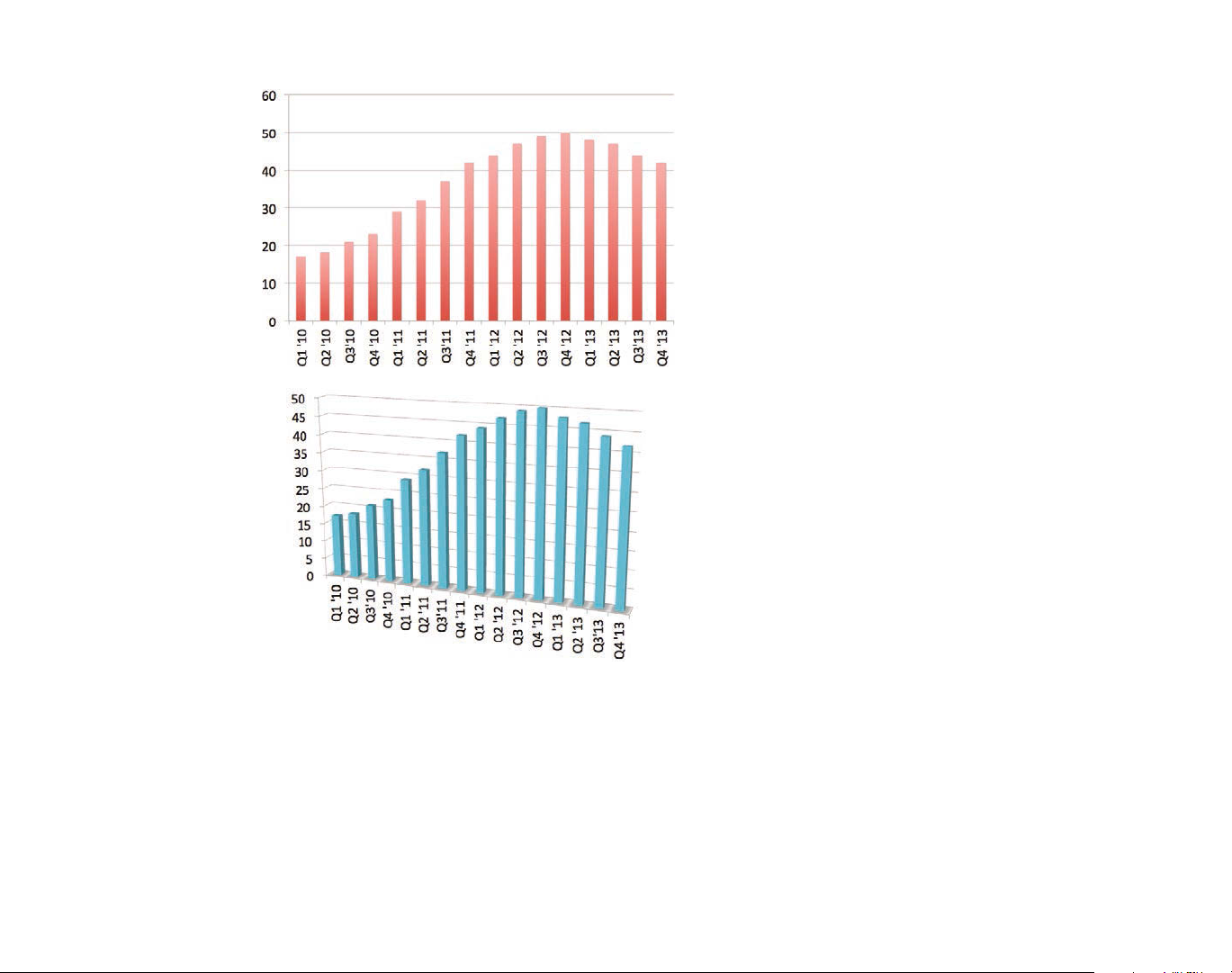

How about this Global Revenue chart? Is it a good chart?

Ultimately, when you create a visualization, that’s GLOBAL REVENUE

what you need to know. Is it good? Is it effective? IN MILLIONS

Are you helping people see and learn? Are you $50

making your case? Maybe even is it impressing your boss? So, is this one good? 25

It certainly looks smart. It’s labeled well. It eschews

needless ornamentation. It uses color judiciously.

And it tells a clear, simple story: After years of

healthy growth, revenue peaked and then started 0

to taper. If we held this chart up to the rules and 2010 2011 2012 2013

principles proffered by data visualization experts QUARTERLY

and authors such as Edward Tufte, Stephen Few, SOURCE: COMPANY RESEARCH

and Dona Wong, it would probably pass most of their tests.3

But does that mean it’s good?

A NEW LANGUAGE AND A NECESSARY CRAFT | 5

Many people love the 3-D option; it seems to draw the eye.

These tools are right there with our data, and

they’re very easy to use. But as dataviz becomes

a thing, and we constantly encounter more well-

designed, thoughtful, persuasive, and inspiring

charts and graphs, we recognize that charts like

these fall short, even if we can’t say exactly why.

As most managers use it, Excel visualizes data

cells automatically, unthinkingly. The result beats

looking at a spreadsheet—but that’s a low bar.

So these charts aren’t as good as the first one, but

the question remains: Is that first chart good?

We don’t know. Without context, no one—not me,

not you, not a professional designer or data scien-

tist, not Tufte or Few or Wong—can say whether

that chart is good. In the absence of context, a chart Data tools such as

is neither good nor bad. It’s only well built or poorly Excel can create charts almost

built. To judge a chart’s value, you need to know instantly, but does

more—much more—than whether you used the that mean they’re good charts?

right chart type, picked good colors, or labeled axes

correctly. Those things can help make charts good,

but in the absence of context they’re academic

considerations. It’s far more important to know

It’s probably better than what you could produce

Who will see this? What do they want? What do they

quickly in an Excel doc or a Google Sheet—most

need? What idea do I want to convey? What could I

managers’ go-to dataviz tools. You could turn a row

show? What should I show? Then, after all that, How

of data into a chart there with a single click. And will I show it?

if you needed to present to the CEO, or to share-

holders, you might play with some of Excel’s preset

If you’re presenting to the board, it may not be

options to make it look fancier and more dynamic.

a good chart. The directors know the quarterly 6 | INTRODUCTION

revenues; they’re going to tune you out, check their

phones, or, worse, get annoyed that you’ve wasted

their time. Maybe they’re looking for markets to

invest in to reverse the revenue trend. In that case,

a breakdown of changes in the global distribution of

revenue might make a good chart:

REGIONAL REVENUE TRENDS, Q1 ’10–Q4 ’13 PERCENTAGE CHANGE +30% +15 0 -15 -30% North South Western Eastern Asia- Africa America America Europe Europe Pacific SOURCE: COMPANY RESEARCH

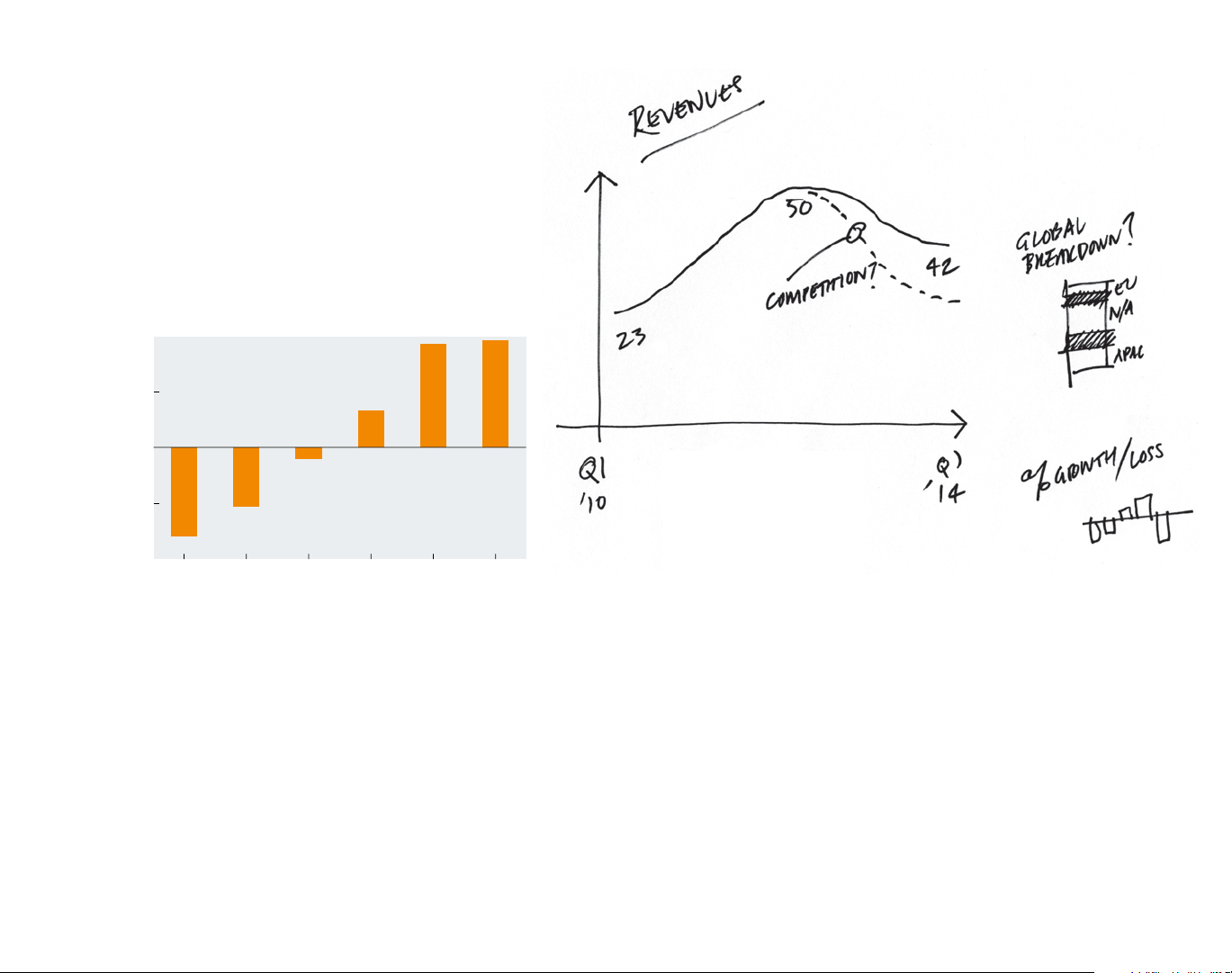

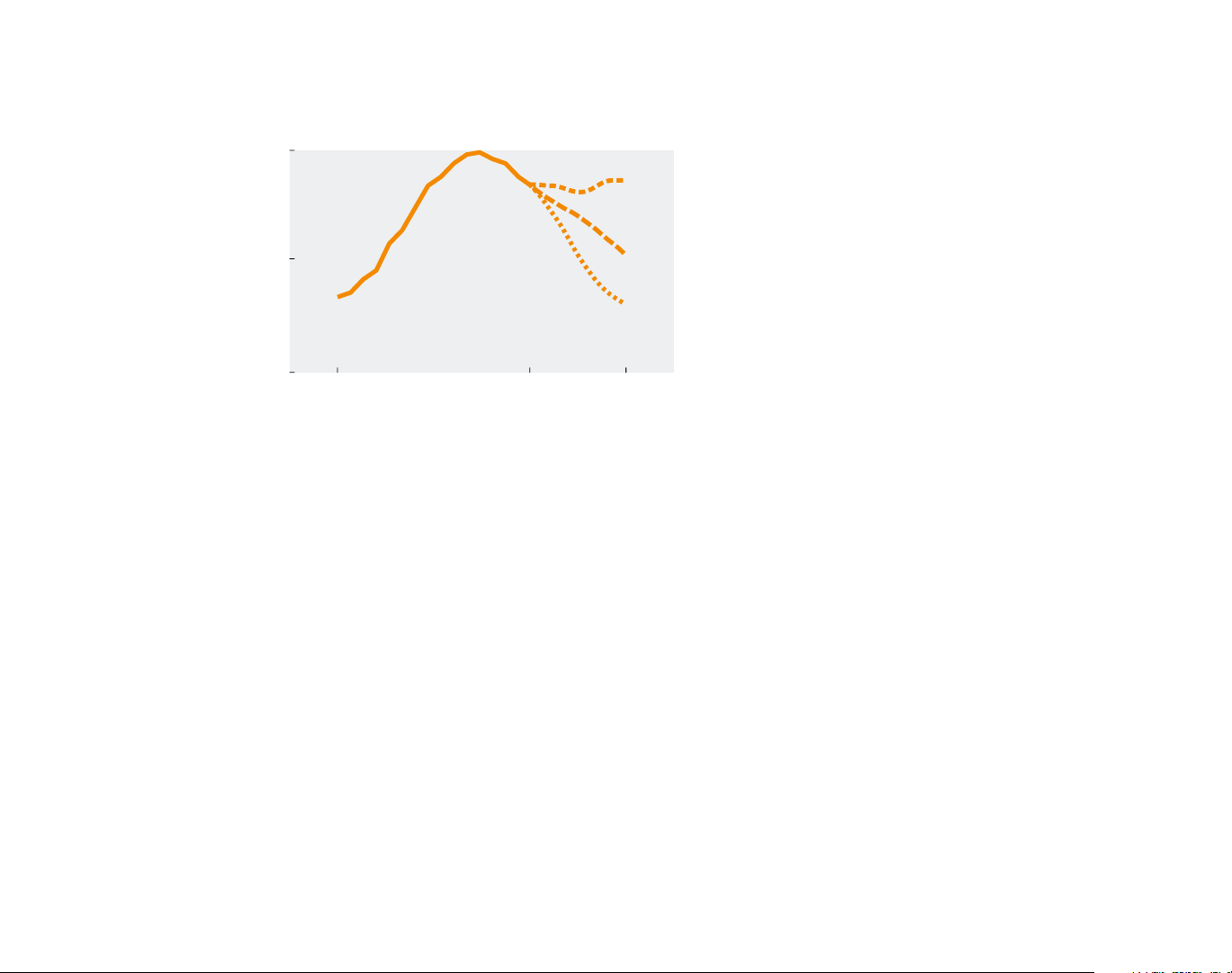

But if it’s for a strategy off-site with the executive

committee where future scenarios will be played

out, it’s probably not a good chart. How can you

Same data set. Completely different chart.

talk about the future with a chart that only shows

the past? A good chart in that context would reflect

If the boss has said, “Let’s talk about revenue trends

multiple future scenarios, as seen on the Revenue

in our next one-on-one,” this isn’t a bad chart per

Projections chart on the following page.

se, but it may be overkill. In that scenario, the

time spent refining the chart might be better used

Then again, if you’re meeting with a new manager

exploring ideas around the revenue data on a white-

who needs to understand basic facts about the

board, which has the advantage of being an interac-

company, then yes, the original chart is a good

tive space, ready to be marked up: chart.

A NEW LANGUAGE AND A NECESSARY CRAFT | 7

Tel ing me to “Be clear” is like tel ing me to “Hit the bal

REVENUE PROJECTIONS—THREE SCENARIOS

squarely.” I know that. What I don’t know is how to do IN MILLIONS

it. To explain how to write clearly, I have to go beyond $50 platitudes. C

I want you to understand this matter—to understand

why some prose seems clear, other prose not, and 25 A

why two readers might disagree about it; why a

passive verb can be a better choice than an active B

verb; why so many truisms about style are either

incomplete or wrong. More important, I want that

understanding to consist not of anecdotal bits and 0

pieces, but of a coherent system of principles more Q1 Q1 Q1 2010 2014 2016

useful than “Write short sentences.”4

What Williams says about writing is just as true BEYOND RULES AND PLATITUDES

for dataviz. You need to get beyond rules and

understand what’s happening when you encounter

visualization. Why do you like some charts and

This simple example should liberate you from the

not others? Why do some seem clear and others

idea that the value of a chart comes primarily from muddled?

its execution (it doesn’t) and that its quality can be

measured by how well it follows the rules of presen-

How do you know, say, when to use a map instead of

tation (it can’t). Just as reading Strunk and White’s

a line chart? One rule book for building charts states

The Elements of Style doesn’t ensure you’ll write

unequivocally, “No mapping unless geography is

well, learning visual grammar doesn’t guarantee

relevant.”5 That’s like telling you to “hit the ball

that you’ll create good charts.

squarely.” How do you know whether geography

is relevant? What does relevant mean? Geography

In his excellent Style: Toward Clarity and Grace,

could be considered the most relevant factor in

Joseph M. Williams explains why grammar rule

your chart showing regional revenue growth for the books fall short:

board. Should you map it instead? 8 | INTRODUCTION

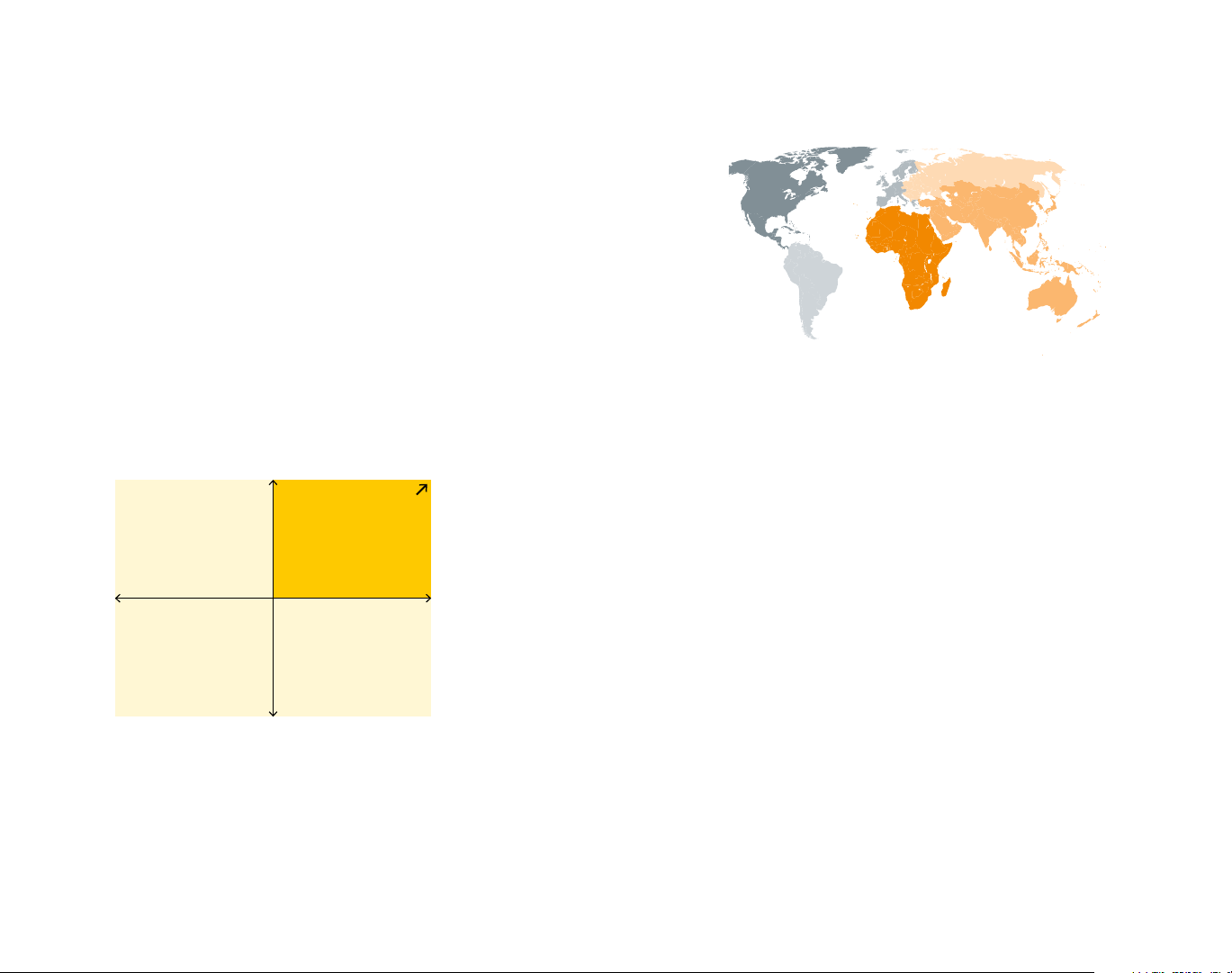

Does a map make the point about regional revenues

REGIONAL REVENUE TRENDS, Q1 ’10–Q4 ’13

better than a chart does? Would it help you persuade PERCENTAGE CHANGE

the board that regional revenues matter? Are you even

trying to do that? Would mapping this data geographi- +10%

cally be worth the extra effort? –3% –24% +28%

These questions seek the context that rules for presen-

tations can’t address. My point here is not to suggest +29%

that rules for crafting good visualizations aren’t –16%

necessary or useful. They’re both. But rules are open

to interpretation, and sometimes arbitrary or even

counterproductive when it comes to producing good SOURCE: COMPANY RESEARCH

visualizations. They’re for responding to context, not setting it.

Instead of worrying about whether a chart is THE GOOD CHARTS MATRIX

“right” or “wrong,” focus on whether it’s good. Toward EXCELLENT

You need, as Williams says, principles that help the perfect chart

you understand why you’d choose a bar chart or GOOD CHARTS

a line chart or no chart at all. A perfectly relevant CONTEXTUAL

visualization that breaks a few presentation rules AWARENESS

is far more valuable—it’s better—than a perfectly What am I LOW HIGH trying to say,

executed, beautiful chart that contains the wrong to whom, and

data, communicates the wrong message, or fails to where?

engage its audience. The more relevant a data visu-

alization is, the more forgiving, to a point, we can POOR be about its execution. DESIGN EXECUTION

The charts you make should fall into the top-right How well is this chart

zone in the Good Charts Matrix, shown at the left. constructed?

Learning to think visually in order to produce good

charts is the subject of this book.

A NEW LANGUAGE AND A NECESSARY CRAFT | 9 THE VISUAL THINKING IMPERATIVE

decision makers. Their complex visualizations were

translated into simpler ones for the management

team, which approved changes to the Osprey’s

Three interrelated trends are driving the need to

maintenance code. Operations improved. “It’s hard

learn and practice visual thinking. The first is the

to tell this kind of story,” says David Kasik, a tech-

massive increase of visualization, mentioned above.

nical fellow at Boeing who worked on the Osprey

The more sophisticated, higher-quality dataviz in

project. “Ultimately we have to provide a form for

products and media we see now has raised expec-

telling our story in a way that others can in fact

tations for the charts that others provide us, both in

comprehend.” That form is visual.

our consumer lives and in our business lives.

And it’s not limited only to such specialized

The second trend is data: both its sheer volume and

data. Even common data such as financials and

the velocity with which it comes at us. So much

marketing analytics, which companies generate as

information hitting us so fast demands a new way

a matter of course, is so deep and complex now that

of communicating that abstracts, simplifies, and

they can’t effectively deal with it in raw form. helps us cope.

The third trend: Everybody’s doing it. Historically,

At Boeing, for example, engineers want to increase

some technologies have enjoyed a democratizing

the operational efficiency of the Osprey—a plane

moment, when the innovation becomes cheap

that takes off and lands like a helicopter. The

enough to buy and easy enough to use that anyone

plane’s sensors produce a terabyte of data to

can try it. Examples of this shift are legion. Aldus

analyze on each takeoff and landing. Ten Osprey

PageMaker, the first word processor, and Hypertext

flights produce as much data as the entire print

Markup Language (HTML) each in its own way

collection of the Library of Congress.6 The idea of

made everyone a potential publisher. Dan Bricklin,

scouring that data in any raw format borders on

a cocreator of VisiCalc, the first spreadsheet, once

absurd, but they tried—a team of five worked on it

said that his democratizing software “took 20 hours

for seven months, looking without success for ways

of work per week for some people and turned it to improve efficiency.

out in 15 minutes and let them become much more creative.”7

Then Boeing switched to visual analysis to find

signals in the noise. Within two weeks a pair of

When ownership of the technology suddenly shifts

data scientists had identified inefficiencies and

from a small group of experts to the masses, exper-

maintenance failures. But it wasn’t enough to find

imentation flourishes, for better and worse. (HTML

the signals; they had to communicate them to the

led to garish GeoCities websites, but also to Google.) 10 | INTRODUCTION

Dataviz is no different. What was once a niche

visual communication. You may have heard people

discipline owned by a few highly skilled cartogra-

refer to the “art” of visualization, or the “science”

phers, data scientists, designers, programmers, and

of it. A better term for what this book presents is

academics is now enjoying a noisy experimentation

craft, a word that suggests both art and science.

phase with the rest of us. For the first time, the tools

Think of a cabinetmaker, who may understand

used to visualize data are both affordable (some-

some art and some science but who ultimately

times free) and easy to use (sometimes drag-and- builds something functional.

drop). Scores of websites have emerged that allow

you to upload a data set and get bespoke visual-

An apprentice cabinetmaker might start learning

izations kicked out in seconds. Tableau Software,

his craft by understanding cabinets—their history,

currently a darling of visualization programming,

how people use them, the materials and tools

aims to become no less than the word processor of

needed to make them. Then he’d learn a system

data visualization, guiding your “visual grammar”

for building good cabinets, and he’d probably build and design for you.

a hell of a lot of them. He’d also install them, and

learn how cabinets work in different types of spaces

Meanwhile, vast reserves of the fuel that feeds visu-

and with different types of customers. Eventually

alization—data—have been made freely or cheaply

his skills would be deep enough to add his own

available through the internet. It costs virtually

artistic and clever functional details.

nothing to try to visualize data, so millions are

trying. But drag-and-drop software can’t ensure

Learning how to build good charts isn’t unlike

good charts any more than rule books can. Learning

learning how to build good cabinets, so this

to think visually now will help managers use these

book will proceed in the same way. Part one—

burgeoning tools to their full potential when this

Understand—provides a brief history of visual-

adolescence ends, as it naturally will.

ization and a high-level summary of the art and

science behind charts. It leans on (and some-

times also challenges) the wisdom of experts and A SIMPLE APPROACH TO

academics in visual perception science, design AN ACCESSIBLE CRAFT

thinking, and other fields to illuminate what visu-

alization is and what happens when a chart hits our

eyes. In addition to providing an intellectual foun-

The best news of all is that this is not a hard

dation, this brief section should assuage your fears

language to learn, even if it seems intimidating.

about learning a whole new discipline. You don’t

Mastering a simple process will have an outsized

have to become a professional designer or data

impact on the quality and effectiveness of your

scientist to reach a new level in your chart making.

A NEW LANGUAGE AND A NECESSARY CRAFT | 11